Abstract

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is caused by mutations in SMN1. SMN2 is a paralogous gene with a C•G-to-T•A transition in exon 7, which causes the skipping of this exon in most SMN2 transcripts and results in low levels of the protein survival motor neuron (SMN). Here we show, in fibroblasts derived from patients with SMA and in vivo in a mouse model of SMA that, irrespective of the mutation in SMN1, CRISPR-based adenosine base editors can be optimized to target the SMN2 exon-7 mutation or nearby regulatory elements to restore the normal expression of SMN. After optimizing and testing more than 100 guide RNAs and base editors, and leveraging Cas9 variants with high editing fidelity that are tolerant of different protospacer-adjacent motifs, we achieved the reversion of the exon-7 mutation via an A•T-to-G•C edit in up to 99% of fibroblasts, with concomitant increases in the levels of the SMN2 exon-7 transcript and of SMN. Targeting the SMN2 exon-7 mutation via base editing may provide long-lasting outcomes to patients with SMA.

Keywords: CRISPR, genome editing, adenine base editors (ABEs), neuromuscular diseases, SMA

Introduction

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a devastating neuromuscular disease that remains a leading cause of infantile death worldwide. SMA is primarily characterized by the death of motor neurons, muscle denervation, and muscle weakness1,2. Most SMA cases are caused by loss-of-function mutations within the Survival Motor Neuron 1 (SMN1) gene1,2. The most common mutation in SMN1 is a deletion of exon 7, which leads to abrogation of SMN protein function3. An important modifier of SMA severity is the number of copies of a paralogous gene Survival Motor Neuron 1 (SMN2). The sequence of SMN2 mainly differs from SMN1 by a synonymous C•G-to-T•A transition in exon 7 (Fig. 1a). This C-to-T polymorphism in the 6th nucleotide of SMN2 exon 7 (henceforth “C6T”; Fig. 1b), causes the skipping of exon 7 in most SMN2 transcripts due to alternative splicing. While SMN2 still produces ~10% functional SMN protein, this is not enough to rescue the vast majority of SMA patients4–6 (Fig. 1a). Targeting SMN2 transcripts with a small molecule or an antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) to transiently increase the retention of exon 7 demonstrated notable clinical results in infants treated early in the disease process7–10.

Figure 1. Development of adenine base editing to correct SMN2 exon 7 C6T.

a, Schematic of SMN1 and SMN2 in unaffected individuals and spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) patients. Mutations in SMN1 cause SMA due to a depletion of SMN protein, which may be recovered by editing SMN2. b, Schematic of the SMN2 exon 7 C-to-T (C6T) polymorphism compared to SMN1, with base editor gRNA target sites and their estimated edit windows. c-d, A-to-G editing of SMN2 C6T target adenine and other bystander bases when using ABEs comprised of adenine deaminase domains ABEmax33,38, ABE8.20m35, and ABE8e36 fused to wild-type SpCas9 (panel c) or SpRY37 (panel d), assessed by targeted sequencing. e, A-to-G editing of adenines in SMN2 exon 7 when using SpRY or other relaxed SpCas9 PAM variants44, assessed by targeted sequencing. f, A-to-G editing in exon 7 of SMN2 when using ABE8e-SpG and gRNAs A9 or A10. g, A-to-G editing in exon 7 of SMN2 when using ABE8e-SpRY37 or ABE8e-iSpyMac45 with gRNAs A7 and A8, or wild-type ABE8e-SpCas9 with gRNA A10. Data in panels c-g from experiments in HEK 293T cells; mean, s.e.m., and individual datapoints shown for n = 3 or 4 independent biological replicates.

Notwithstanding the development of therapies for SMA, current treatments have limitations and are not a permanent cure. For instance, Risdiplam (Evrysdi, Roche Genentech) is a daily orally administered small molecule splicing modifier that can enhance SMN2 expression by targeting displacement of hnRNP G11–13, but this is not a definitive cure for SMA. Nusinersen (Spinraza, Biogen) is an ASO that increases exon 7 inclusion and SMN2 expression by disabling regulatory elements in SMN2 intron 7 and is delivered via an intermittent regimen of intrathecal injections across the lifespan of the patient8,9,14. Because Nusinersen is injected into the spinal fluid, it is not expected to modify SMN2 expression in peripheral tissues that may play a role in SMA15–18. Likewise, exogenous gene addition using an adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector expressing SMN1 such as onasemnogene abeparvovec (Zolgensma, Novartis) presents many challenges19, including unknown longevity of expression from the AAV transgene20, and potential eventual decay of efficacy in dividing cells due to AAV dilution21. Moreover, persistent supraphysiological expression of SMN1 from ubiquitous promoters may cause toxicity22. Although the success of approved therapies has minimized the previously high infantile and childhood morbidity and mortality associated with SMA, their emerging limitations underscore the need to further improve upon existing therapies in terms of the scope and durability of SMN protein expression. Thus, there is an unmet need to develop single-dose therapies that permanently increase SMN levels.

Genome editing technologies capable of permanently editing SMN2 to restore SMN levels could overcome several of these challenges (Fig. 1a). The pursuit of genome editing methods to treat the diverse spectrum of SMN1 mutations is less feasible since it would necessitate patient- and mutation-specific optimization of a variety of editing approaches. Instead, the development of a strategy to directly revert the SMN2 C6T polymorphism could prove to be a broadly applicable editing strategy to increase SMN expression for SMA patients. This contrasts with other editing approaches that have been explored to treat SMA, including Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9 or Cas12a nucleases to attempt homology-directed repair of SMN2, or the use of nucleases to modify intronic splicing regulatory elements (SREs) in intron 7 23–25 (which are also the target of nusinersen26). However, due to the number of copies and high similarity between the SMN1 and SMN2 genes, nuclease-based approaches that create DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) carry the risk of creating large chromosomal deletions, translocations, or other undesirable DSB-related consequences27–31.

The optimization of DSB-independent strategies could therefore offer advantages over nuclease-based strategies by reducing the likelihood of unwanted genome-scale changes and potentially improving editing efficiency. Base editors (BEs) are one potential technology capable of installing point mutations without intentionally creating DNA DSBs32. Typically, BEs are composed of a fusion of a CRISPR-Cas enzyme (i.e. Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9; SpCas9) to a deaminase domain, and when directed by a guide RNA (gRNA) to genomic sites, BE complexes can initiate edits of specific DNA bases. Adenine base editors (ABEs) catalyze A•T to G•C edits32–34 using an evolved TadA deaminase to convert adenines to inosines, which are read as guanines by polymerases33. However, the deaminase domain can only act in a narrow ‘edit window’ within the gRNA-Cas target site at a fixed distance from the protospacer-adjacent motif (PAM; Fig. 1b). Thus, the efficiency of base editing is dependent on the availability of Cas9 variant enzymes that can recognize a range of PAMs to maximize editing of the intended base while minimizing editing of unwanted nearby bases (so-called bystander edits). We therefore hypothesized that the identification and optimization of ABEs capable of editing only the target C6T adenine in SMN2 exon 7 could correct the transition mutation and restore SMN expression (Fig. 1a).

Here we explored the potential of various ABE-based strategies to treat SMA, including correction of C6T in SMN2 and modification of SMN2 intron 7 SREs. We identified efficient and precise combinations of ABEs and gRNAs capable of specific A-to-G editing in HEK 293T cells with low levels of bystander editing. We then extended our SMN2 C6T editing approach into SMA patient-derived fibroblasts, leading to increased exon 7 retention in SMN2 transcripts and elevated expression of SMN protein. We assessed the genome-wide safety of this approach and while we did not observe unwanted off-target editing in fibroblasts, off-target editing was reduced in HEK 293T cells when using high-fidelity variants. Finally, we demonstrate the feasibility of translating this approach in vivo in a mouse model of SMA via AAV-mediated delivery of the ABE and gRNA. Taken together, our results demonstrate that ABE-mediated editing of SMN2 C6T leads to substantial increases in SMN protein levels, establishing the potential of a new therapeutic approach to treat SMA.

Results

Development of ABEs to edit SMN2 C6T

We first explored whether ABEs could correct the C•G-to-T•A C6T transition in SMN2 exon 7 by performing experiments in HEK 293T cells. There are two potential challenges for this approach. First, there is only one gRNA target site with an NGG PAM accessible with wild-type (WT) SpCas9, which positions the target adenine in position 10 of the spacer (A10; Fig. 1b). The 10th nucleotide of the spacer is near the border of the canonical ABE edit window, although engineered adenine deaminase domains have expanded editing potency across a wider sequence space35,36. A second potential complicating factor is that the target adenine is bordered by three additional adenines (Fig. 1b), which may lead to unwanted bystander edits of unknown functional consequences. Ideally the ABE would edit only the target adenine with minimal editing of the neighboring adenines.

To identify an efficient and precise ABE, we designed seven different gRNAs against sites harboring various PAMs, tiling the edit window of the ABEs by placing the target base at positions A4-A10 (Fig. 1b). Due to the availability of only one site with an NGG PAM, in addition to performing these experiments with WT SpCas9 (Fig. 1c), we also utilized our previously engineered SpCas9 variant that has a relaxed tolerance for PAMs37, SpRY (Fig. 1d). In our initial experiments using ABEmax33,38, as expected, WT SpCas9 showed measurable activity only when using the A10 gRNA that targets the site encoding an NGG PAM (Fig. 1c). Conversely, ABEmax-SpRY exhibited A-to-G editing using nearly every gRNA, although with modest editing (<5%; Fig. 1d). We therefore explored the use of two engineered ABE domains previously shown to improve on-target editing (ABE8.20m and ABE8e)35,36. Using these two additional TadA domains, WT SpCas9 and SpRY ABEs mediated substantially higher A-to-G editing (Figs. 1c and 1d, respectively). With WT SpCas9 ABEs, once again only gRNA A10 was conducive to high levels of editing (Fig. 1c). When using SpRY ABEs, we observed high levels of editing using gRNAs A5 (NAT PAM), A7 (NAA PAM), and A8 (NAA PAM) (Fig. 1d). In general, ABE8e-based enzymes led to higher levels of editing compared to ABE8.20m (Figs. 1c and 1d). Analysis of different 5’ gRNA spacer architectures 39–41 did not substantially impact editing efficiency (Sup. Note 1 and Sup Figs. 1a and 1b).

We found that high levels of A-to-G editing could be achieved at the intended target adenine (SMN2 C6T, leading to a silent Phe codon change), with minimal bystander editing of three neighboring adenines (Figs. 1c and 1d). When using ABE8e-WT with gRNA A10 or ABE8e-SpRY with gRNA A8, we observed the highest levels of A-to-G editing with near-background levels of bystander editing (Fig. 1d). The lack of bystander editing of the adjacent adenines is partially supported by previous reports42,43 of preceding adenines being inhibitory to ABE efficiency (as is the case of each of the 3 bystander As in these target sites), while preceding thymines promote ABE editing (as with the target adenine). Additional transfections using various ABEs and gRNAs targeting other genomic sites encoding poly-adenine stretches (at non-SMN2 loci) did not reveal enrichment for editing at the 5’ adenine in all cases (Sup. Figs. 2a–2f and Sup. Note 2).

We also assessed editing with other previously described SpCas9 PAM variants, including relaxed PAM variants SpCas9-NRRH, NRTH, and NRCH (which can target sites with their namesake PAMs; R is A or G, and H is A, C, or T)44, SpG (capable of targeting sites with NGN PAMs)37, and iSpyMac (capable of targeting sites with NAA PAMs)45. For these experiments we utilized ABE8e to maximize A-to-G editing efficiency across a wider edit window. With ABE8e-NRRH, -NRTH, and -NRCH, we observed consistently lower on-target editing compared to ABE8e-SpRY (Fig. 1e). With ABE8e-SpG paired with gRNA A9 (NGA PAM) or gRNA A10 (NGG), we observed modest levels of on-target editing (Fig. 1f) at efficiencies lower than ABE8e-WT and gRNA A10 (Fig. 1c) or ABE8e-SpRY with gRNAs A5, A7, or A8 (Fig. 1d). Lastly, on-target editing efficiency was superior when using gRNA A7 with ABE8e-SpRY versus ABE8e-iSpyMac but was comparable between these enzymes with gRNA A8 and at levels similar to ABE8e-SpCas9 with gRNA A10 (Fig. 1g).

Given that the number of genomic sites encountered by Cas9 enzymes with minimal PAM requirements is expanded, one consideration when using relaxed PAM variants is the potential to observe editing at an increased number off-target sites37,44. To mitigate potential genome-wide off-target editing, we determined whether the ABE8e constructs were compatible with two previously described high-fidelity SpCas9 variants that eliminate or minimize off-target editing46,47. We generated ABE8e fusions to SpCas9 and SpRY in the presence of HF1 substitutions that were previously shown to eliminate nearly all off-target edits47, and the HiFi mutation that was previously shown to reduce levels of off-target editing46. The HF1 and HiFi versions of ABE8e-SpCas9 exhibited a substantial loss in on-target SMN2 editing (Sup. Fig. 3a). Conversely, in some cases the HF1 and HiFi variants of ABE8e-SpRY retained high levels of editing (albeit at levels lower than ABE8e-SpRY; Sup. Fig. 3b), potentially indicating that the high-fidelity mutations may exhibit a greater loss in on-target base editing when the target adenine is closer to the boundary of the ABE edit window. We observed similar levels of bystander editing for all conditions (Sup. Figs. 3a and 3b), and a minor impact of the 5’ gRNA spacer architecture on the efficiency of high-fidelity variants (Sup. Note 1 and Sup. Figs. 3c–3f).

We also determined whether the ABE8e constructs were compatible with two previously described strategies to reduce RNA off-target activity, including the TadA-V106W mutation or inlaying the deaminase into nCas9 (CE-ABE8e-Cas9)36,48. CE-ABE8e-SpRY exhibited similar on-target SMN2 C6T editing compared to ABE8e-SpRY, however with ABE8e(V106W)-SpRY we observed lower A-to-G efficiency (Sup. Fig. 4a). In addition, we observed increased bystander editing with CE-ABE8e-SpRY at levels not previously observed with ABE8e-SpRY (Sup. Fig. 4a). We observed similar results when comparing ABE8e-SpCas9, ABE8e(V106W)-SpCas9 and CE-ABE8e-SpCas9 paired with gRNA A10 (Sup. Fig. 4b). These observations were generalizable across additional genomic sites (Sup. Figs. 4c and 4d).

Taken together, these results demonstrate that optimized ABEs are selective for editing the target C6T adenine in SMN2 exon 7 with low-level bystander editing, particularly when utilizing ABE8e-WT with gRNA A10 or ABE8e-SpRY with gRNA A8. Given that both enzyme-gRNA pairs exhibited comparable on-target editing of the target adenine, we selected the ABE8e-SpRY and gRNA A8 pair for further study due to a more optimal positioning of the target adenine in the ABE edit window and its enhanced compatibility with high-fidelity variants.

Base editing of SMN2 exon 7 and intronic and exonic splicing silencers in human cells

SMN2 exon 7 alternative splicing is caused by the C6T mutation that abrogates SMN2 exon 7 inclusion through multiple mechanisms, including disruption of binding sites for pre-mRNA-splicing factors SF2/ASF49–51, and creation of binding sites for the nuclear ribonucleoproteins hnRNPA1 and hnRNPA2 that repress exon 7 inclusion in SMN2 mRNA51–53 (Sup. Fig. 4a). Interestingly, there are two intronic splicing silencer (ISS) binding sites for these ribonucleoproteins in intron 7 of SMN2 (ISS-N1 and ISS+100; Sup. Fig. 4a). Disruption of these ISSs via genome editing could be an alternate approach to increase SMN2 exon 7 inclusion and SMN expression. Indeed, nuclease-mediated knockout of these two ISSs using CRISPR-Cas12a enzymes was shown to enhance SMN protein expression from SMN224. We therefore explored the use of ABE8e-SpRY to generate A-to-G edits within the ISSs, which would be compatible with our C6T editing approach and would hold advantages over nuclease-mediated editing given substantially reduced levels of DNA DSBs.

To determine whether ABE8e-SpRY could edit the ISS-N1 and ISS+100 regulatory elements in SMN2, we designed 12 gRNAs that would position the edit window of ABE8e-SpRY over adenine bases of ISS-N1 and ISS+100 (Sup. Fig. 5b). We transfected HEK 293T cells using ABE8e-SpRY and each of the 12 ISS-targeting gRNAs in the absence or presence of the gRNA A8 (for simultaneous targeting of exon 7 C6T). When targeting either ISS, we observed editing of various adenines, albeit at efficiencies lower than C6T targeting (Sup. Figs. 5c and 5d; Sup. Note 3). We then explored multiplex targeting of SMN2 by co-transfecting gRNA A8 for C6T and the ISS gRNAs, which led to efficient C6T editing (Sup. Figs. 5e and 5f) and maintenance of ISS-N1 and ISS+100 editing (Sup. Figs. 5c and 5d; Sup. Note 3). These results demonstrate that a dual-editing approach minimally impacts SMN2 C6T editing and could be explored in future studies as a multiplex strategy to increase the likelihood of exon 7 inclusion in the SMN2 transcript.

SMN expression is also regulated by exonic splicing silencers (ESSs), including additional nucleotides in two ESSs in SMN2 exon 7 beyond C6T (ESS-A and ESS-B) serving as targets in a previous study54 (Sup. Fig. 6a). We tested ABE8e-SpRY and ABE8e-SaKKH36 (a small SaCas9 variant that recognizes NNNRRT PAM55) using various gRNAs to place A-to-G edits in the ESSs. We observed editing of various adenines in both ESSs (Sup. Figs. 6b–6e), including high levels of editing levels with ABE8e-SpRY and ESS-A gRNA-3 that would cause Gln>Arg and Asn>Asp/Gly amino acid changes (Sup. Fig. 6b). Together, these results demonstrate the potential of ABEs to modify other regulators of SMN2 exon 7 inclusion beyond C6T by targeting and editing ISS and ESS sequences; though ESS editing beyond C6T may lead to non-synonymous amino acid changes of unknown function.

Assessment of C6T editing and SMN expression in SMA patient-derived fibroblasts

We then assessed the efficiency of our ABE C6T editing approach in five SMA patient-derived fibroblast cell lines (Fig. 2a). We transfected plasmids encoding ABE8e-SpRY-P2A-EGFP and gRNA A8 to permit sorting for GFP+ fibroblasts (Sup. Fig. 7a). Analysis of editing in these sorted cells revealed high levels of SMN2 C6T editing across all five SMA cell lines compared to naïve samples that were untransfected or control samples transfected with SpRY-ABE8e and a non-targeting gRNA (Fig. 2b). For three fibroblast lines, we observed near complete editing (>90% A-to-G edits), while for two additional lines we observed A-to-G editing around 60%. Importantly, there was little (<1%) bystander editing of adjacent adenines across all five fibroblast lines (Sup. Fig. 7b). Additionally, high on-target editing (>80% A-to-G edits) with little (<1%) bystander editing was observed when using ABE8e-SpCas9 and gRNA A10 in one fibroblast line (Sup. Fig. 7c). Together, these results demonstrate that our base editing strategy for C6T is extensible to, and efficient in, SMA patient-derived cells.

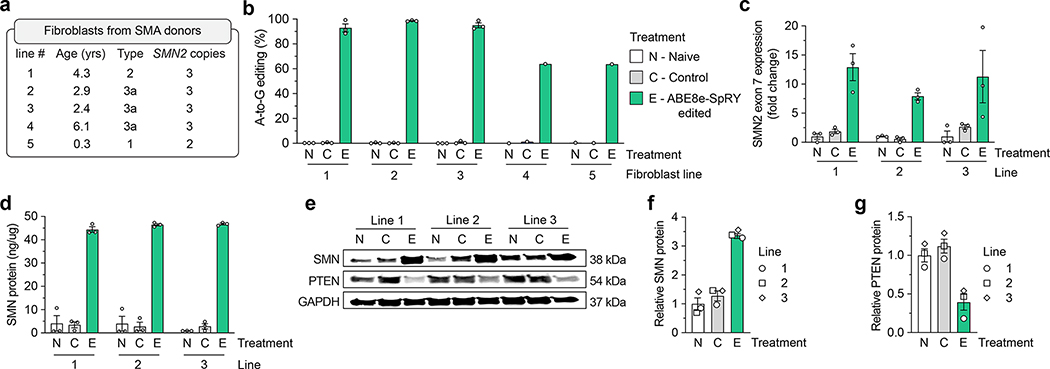

Figure 2. SMN2 C6T editing in SMA patient-derived fibroblasts.

a, Characteristics of five different SMA donors; all lines harbor a homozygous deletion of exon 7 in SMN1. b, A-to-G editing of the C6T adenine in SMN2 exon 7 across five SMA fibroblast cell lines transfected with ABE8e-SpRY and gRNA A8, assessed by targeted sequencing. Naïve (N) cells were untransfected; Control (C) cells were treated with ABE8e-SpRY and a non-targeting gRNA. c, SMN2 exon 7 mRNA expression across three edited (E) SMA fibroblast lines, measured by ddPCR. Transcript levels normalized by GAPDH mRNA, with data presented as normalized fold-change from naïve cells. d, SMN protein levels determined by an SMN-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). e, Representative immunoblot for SMN, PTEN, and GAPDH protein levels across Naïve, Control, or ABE8e-SpRY treated SMA fibroblast lines. f,g, Quantification of SMN and PTEN (panels f and g, respectively) protein levels normalized to GAPDH and the Naïve treatment, determined by immunoblotting. For all assays, GFP-positive fibroblasts were sorted post-transfection and grown in for at least 3 passages; samples from three independent passages were collected for lines 1, 2 and 3 (passages 4–6; see Sup. Fig. 6a), and one passage was collected for lines 4 and 5. For panels b-d, f, and g, mean, s.e.m., and individual datapoints shown for n = 3 independent biological replicates from separate passages (unless otherwise indicated).

Next, we sought to assess the extent to which ABE-mediated editing of SMN2 C6T would increase SMN transcript and protein levels using the three nearly completely edited SMA fibroblast lines (1, 2, and 3). At the transcript level, we observed a ~6.3-fold mean increase in SMN2 exon 7 mRNA expression compared to control cells (Fig. 2c; from SMN2 transcripts alone since each fibroblast line harbors homozygous deletions for SMN1 exon 7). We also detected a ~2.7-fold increase in expression of the early SMN transcript (across the junction of exons 1 and 2 for SMN1 and SMN2) (Sup. Figs. 7d and 7e), suggesting increased stability of full-length SMN mRNA in ABE-edited SMA-fibroblasts.

We investigated concomitant alterations in SMN protein levels in the edited fibroblasts and observed a substantial ~15-fold mean increase in SMN protein levels when compared with control cells as measured by an ELISA (Fig. 2d). Edited SMA fibroblasts have similar SMN protein levels compared to naïve fibroblast lines from non-SMA donors (Sup. Fig. 7f), suggesting that ABE-mediated correction of C6T in SMN2 can restore SMN expression to approximate physiological levels (where in naïve cells SMN expression is largely from SMN1). Moreover, immunoblotting revealed increased SMN protein in edited fibroblasts (Figs. 2e and 2f), although with a lower magnitude than observed with the ELISA (Fig. 2d). Interestingly, restoring SMN protein was associated with a decrease in PTEN protein levels (Figs. 2e and 2g). Elevated PTEN in SMA cells has previously been associated with increased apoptosis56,57, indicating that SMN2 C6T editing may lead to reduced PTEN and improved viability of ABE-edited SMA cells. Together, these assays demonstrate that precise editing of SMN2 C6T in SMA patient-derived fibroblasts results in consistently increased full-length SMN transcript and protein levels.

Off-target nomination and validation

To identify and evaluate potential off-target sites, we utilized computational and experimental methods to profile our Cas9/gRNA combinations that exhibited the highest SMN2 C6T editing. Comprehensive in silico off-target annotation using CasOFFinder58 for WT SpCas9 with gRNA A10 (using NGG, NAG, or NGA PAMs59–61), and SpRY with gRNAs A5, A7, and A8 (using a PAMless NNN search) resulted in 11, 94, 45, and 50 off-targets with 2 or fewer mismatches, including the off-by-one mismatch off-target of SMN1 (Fig. 3a and Sup. Figs. 8a–8c).

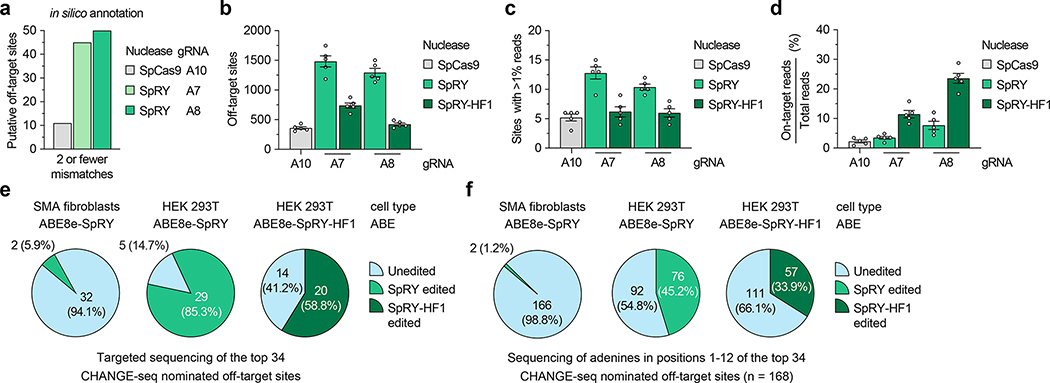

Figure 3. Analysis of SMN2 C6T base editing specificity.

a, Number of putative off-target sites in the human genome with up to 2 mismatches for each gRNA, annotated by CasOFFinder58. Predictions for SpCas9 utilized an NGG, NAG, or NGA PAM; with SpRY, a PAMless NNN search. b, Total number of CHANGE-seq detected off-target sites, irrespective of assay sequencing depth. c, Number of CHANGE-seq identified off-target sites that account for greater than 1% of total CHANGE-seq reads and are common across all 5 SMA fibroblast lines. d, Percentage of CHANGE-seq reads detected at the on-target site relative to the total number of reads in each experiment. For panels b, c, and d, mean, s.e.m, and individual datapoints shown for n = 5 independent biological replicate CHANGE-seq experiments (performed using genomic DNA from each of the 5 SMA fibroblast lines). e,f, Summary of targeted sequencing results from ABE-edited SMA fibroblasts or HEK 293T cells at the top 34 CHANGE-seq nominated off-target sites (common sites across all 5 SMA fibroblast lines and treatments with SpRY or SpRY-HF1), analyzing statistically significant editing of any adenine in the target site (panel e) or of all adenines in positions 1–12 of each of the 34 target sites (panel f).

We then performed an unbiased biochemical off-target nomination assay, CHANGE-seq62, using the gDNA from each SMA-fibroblast line used in this study to experimentally nominate putative genome-wide off-targets. CHANGE-seq experiments were performed using WT SpCas9 nuclease with gRNA A10 (Sup. Figs. 9 and 10) and SpRY and SpRY-HF1 nucleases37,47 with gRNA A7 (Sup. Figs. 11 and 12) and gRNA A8 (Sup. Figs. 13 and 14). The SpRY-HF1 variant includes fidelity-enhancing mutations previously shown to eliminate nearly all off-target edits with nucleases in cells37,47. CHANGE-seq identified a range of off-targets for each nuclease and gRNA combination, with SpRY leading to the highest number compared to WT SpCas9 or SpRY-HF1 (Fig. 3b, Sup. Figs. 9–14, and Sup. Note 4). We observed a comparable number of off-target sites common across each of the five fibroblast lines for SpRY, SpRY-HF1, and SpCas9 treatments, including those that reached greater than 1% of total CHANGE-seq read counts in each experiment (Fig. 3c and Sup. Note 4). The off-by-one mismatch SMN1 off-target was not detected due to homozygous loss in all five fibroblast lines. The intended SMN2 on-target site was typically the most efficient and abundant CHANGE-seq site detected for SpRY and SpRY-HF1 treated samples (Fig. 3d and Sup. Figs. 11–14); in most cases, the on-target site for WT SpCas9 with gRNA A10 was targeted less efficiently than several off-targets, resulting in a smaller fraction of total CHANGE-seq reads assigned to the on-target site (Fig. 3d and Sup. Figs. 9 and 10). However, as expected due to its expanded PAM tolerance, SpRY with gRNA A7 or A8 resulted in a larger number of total CHANGE-seq detected off-target sites compared to WT SpCas9, although most were detected at much lower efficiencies compared to the on-target sites (Fig. 3b, Sup. Figs. 9–14, Sup. Note 4, and Supplementary Table 1). Use of SpRY-HF1 substantially reduced the number of CHANGE-seq detected off-targets and led to an enriched targeting of the SMN2 C6T on-target site, as compared to SpRY treatments (Figs. 3b–3d; Sup. Figs. 11–14). Lastly, the CHANGE-seq-determined read counts for each combination of enzyme and gRNA were consistent across 5 different patient cell lines (Sup. Fig. 15), indicating that these identified on- and off-target sites are not subject to large donor-to-donor variability63 (with in silico analysis predicting little genetic variation at the on-target site64–66; Sup. Note 5).

To assess potential off-target editing in cells, we performed targeted sequencing using genomic DNA from SMA-fibroblasts treated with ABE8e-SpRY and gRNA A8. We assessed the top 34 CHANGE-seq detected off-target sites that were consistently identified across the five SMA-fibroblast lines treated with either SpRY or SpRY-HF1 using gRNA A8 (Supplementary Table 1). Targeted sequencing across 3 different fibroblast lines revealed high levels of editing at the C6T on-target site compared to naïve cells (Sup. Fig. 16a), consistent with our prior results. Analysis of off-target editing at adenines in positions 1–12 of the spacers of the 34 off-targets in edited SMA fibroblasts revealed background-levels of editing at all but two adenines in two off-target sites (Figs. 3e and 3f, and Supplementary Table 2). These results demonstrate that high specificity editing can be achieved when using near PAMless SpRY-based ABEs in fibroblasts, similar to a previous report that utilized an engineered SpCas9 variant with an altered but more specific PAM preference67.

We also sequenced the on- and off-target sites of genomic DNA from HEK 293T cells treated with ABE8e-SpRY or ABE8e-SpRY-HF1 and gRNA A8 (Sup. Fig. 16b). Analysis revealed detectable off-target editing in at least one adenine in 29 of 34 off-target sites when using ABE8e-SpRY or 20/34 with ABE8e-SpRY-HF1 (Fig. 3e), potentially reflecting a difference in the transfection efficiencies and expression levels of the enzymes between sorted fibroblasts and HEK 293T cells. Again, in many cases, the HF1 variant reduced the number of or efficiency of editing at off-target adenines (Figs. 3e and 3f, and Sup. Fig. 16b). To assess the impact of reducing ABE expression on off-target editing, we treated HEK 293T cells with lower doses of plasmids encoding the ABE and gRNA. Reduced editor expression led to a slight decrease in on-target editing, with larger concomitant reductions in editing at off-target sites (Sup. Fig. 16c). In summary, these findings demonstrate that the off-target profile of our ABE-mediated C6T edit is highly specific in fibroblasts but varies depending on the cell-type and/or transfection approach.

In addition to assessing off-target editing, another consideration when using base editors is the occurrence of unwanted insertion or deletion mutations (indels) at the on-target site. Targeted sequencing revealed ~0.8% of reads harboring indels from experiments in HEK 293T cells transfected with either ABE8e-SpRY or ABE8e-SpRY-HF1 and gRNA A8 (approximately 40% and 27% of total editing events; Sup. Fig. 17a). When using genomic DNA from base edited fibroblasts where we observed up to 99% on-target A-to-G C6T editing (Fig. 2b), we observed background-level indels (Sup. Fig. 17b), indicating that the occurrence of indels, much like off-target editing, can vary by cell type.

In vivo base editing in a mouse model of SMA

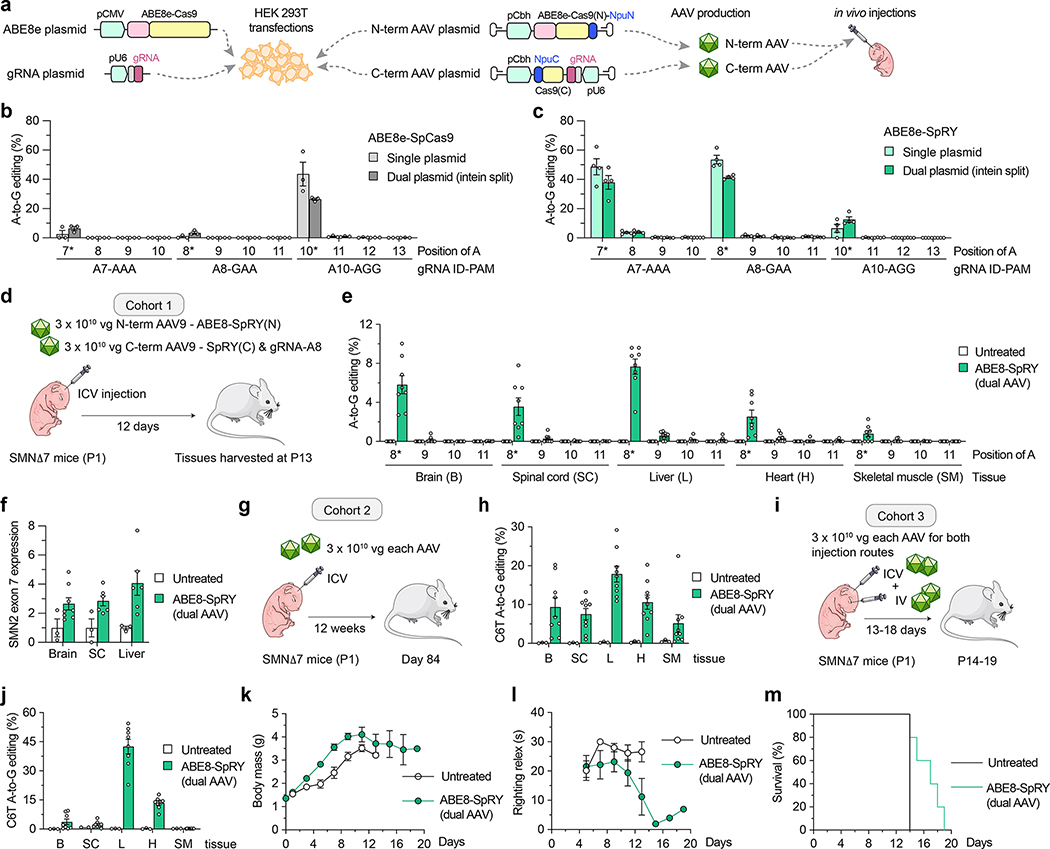

Given our cell-based results indicating efficient C6T editing using ABE8e-SpRY, we sought to assess the efficacy of in vivo editing in a mouse model of SMA. To treat SMA, the primary target tissue for C6T editing is motor neurons in the central nervous system (CNS), although previous reports indicate the importance of SMN expression in peripheral tissues15–18. For in vivo delivery of ABE8e-SpRY we utilized an intein-mediated dual-AAV approach due to the size of the construct, splitting the editing components between two vectors encoding TadA8e fused to an N-terminal fragment of Cas9, and the C-terminal fragment of Cas9 with the gRNA (similar to as previously described67,68) (Figs. 4a and Sup. Figs. 18a and 18b). Prior to generating the AAV vectors, we transfected HEK 293T cells with the AAV plasmids encoding the split ABEs, gRNAs, and inverted terminal repeats (ITRs), and analyzed on-target editing of SMN2 C6T. Split WT ABE8e-SpCas9 with gRNA A10 resulted in ~30% on-target A-to-G editing, levels lower than what we observed for the conventional ABE construct (Fig. 4b). However, when assessing editing with the split ABE8e-SpRY constructs using either gRNA A7 or A8, we observed approximately ~40% editing, levels more comparable to the single plasmid ABE (Fig. 4c). We also titrated the amount of AAV plasmids transfected. We observed a progressive decrease in SMN2 C6T editing with lower DNA amounts, with slightly higher C6T editing with ABE8e-SpRY and gRNA A8 compared to ABE8e-SpCas9 and gRNA A10 at a medium DNA dose (Sup. Fig. 19).

Figure 4. AAV-mediated delivery of base editors for in vivo SMN2 C6T editing.

a, Schematics of conventional expression plasmids (left panel) and AAV ITR-containing intein-split plasmids (right panel) for ABE and gRNA delivery in cells and in vivo. gRNA, guide RNA; NpuN/NpuC, N- and C-terminal intein domains; Cas9(N) and Cas9(C), N- and C-terminal fragments of SpCas9 variants. b,c, A-to-G editing of SMN2 C6T target adenine and other bystander adenines when using ABE8e-SpCas9 with gRNA A10 (panel b) or ABE8e-SpRY with gRNA A8 (panel c), assessed by targeted sequencing. Data in panels b and c from experiments in HEK 293T cells; mean, s.e.m., and individual datapoints shown for n = 3 independent biological replicates. d, Schematic of P1 intracerebroventricular (ICV) injections in SMNΔ7 mice with dual AAV9 vectors that express intein-split ABE8e-SpRY and gRNA A8 (cohort 1). e, A-to-G editing of SMN2 exon 7 adenines following ICV injections of AAV encoding ABE8e-SpRY with gRNA A8 (panel d). Editing across different tissues (without sorting for transduced cells) assessed by targeted sequencing. n = 8 treated and n = 6 untreated (sham injection) SMNΔ7 mice; mean, s.e.m., and individual datapoints shown. f, SMN2 exon 7 mRNA expression in select tissues from mice in cohort 1. Exon 7 transcript levels were measured by ddPCR and normalized by SMN2 exon 1/2 expression. Data presented as fold change from untreated mice. n = 8 treated and n = 6 untreated SMNΔ7 mice; mean, s.e.m., and individual datapoints shown. SC, spinal cord. g, Schematic of P1 ICV injections with longer-term 12-week follow-up in Smn+/Smn+/SMN2 and Smn+/Smn−/SMN2 mice for cohort 2, using the same injection scheme as cohort 1. h, A-to-G editing of SMN2 C6T in tissues of mice from cohort 2. i, Schematic of cohort 3 featuring combined P1 ICV and retroorbital (IV) injections in SMNΔ7 mice. n = 9 treated and n = 3 untreated SMNΔ7 mice; mean, s.e.m., and individual datapoints shown. B, brain; SC, spinal cord; L, liver; H, heart, SM, skeletal muscle. j, A-to-G editing of SMN2 C6T in tissues of mice from cohort 3. n = 8 treated and n = 3 untreated SMNΔ7 mice; mean, s.e.m and individual datapoints. B, brain; SC, spinal cord; L, liver; H, heart, SM, skeletal muscle. k-m, Phenotypic characterization in SMA mice from cohort 3, including body mass (panel k), motor function (panel l) and survival rate (panel m) assessments. Lon-rank test revealed a significant difference between treated and untreated mice in the survival rate (P = 0.01). n = 8 treated and n = 3 untreated SMNΔ7 mice; mean and s.e.m. (panels k-i), and survival rate (panel m) shown.

We then performed a pilot study in neonatal P1 mice to compare the CNS transduction efficiency of two AAV capsids, AAV9 and AAV-F69 after intracerebroventricular (ICV) injections (Sup. Figs. 20a–20e and Sup. Note 6). Since we observed comparable spinal cord transduction between either serotype and given that AAV9 is the serotype of the FDA approved Zolgensma gene therapy to treat SMA19, we selected AAV9 for in vivo studies.

To determine whether we could edit SMN2 C6T using ABE8e-SpRY and gRNA A8 in vivo, we selected SMNΔ7 mice as a model for experiments (Sup. Note 7). SMNΔ7 mice are transgenic for the human SMN2 gene and SMNΔ7 cDNA and have a severe and rapid phenotype under Smn−/− conditions70–72. We performed ICV injections of 3 × 1010 vector genomes (vg) of each of the N- and C-terminal AAVs in P1 SMNΔ7 neonatal mice, and we harvested tissues from mice at P13 for sequence analysis (Fig. 4d and Sup. Note 7). Whether from the Smn+/+, Smn+/−, or Smn−/− genotypes (Sup. Fig. 21a), we observed on-target (SMN2 C6T) A-to-G editing in multiple tissues, including the brain, spinal cord, liver, heart, and skeletal muscle (Fig. 4e and Sup. Figs. 21b and 21c). In the tissues of primary interest, we detected ~6% (brain) and ~4% (spinal cord) A-to-G editing on average (range of 2% to 10% across different mice) with low levels of bystander editing in these edited tissues (Fig. 4e and Sup. Note 7). These low levels of editing in bulk tissue are similar to other studies that delivered base editors via ICV injections in neonatal mice via AAV vectors or eVLPs68,73, and they were sufficient to promote a notable 2- to 4-fold increase in SMN transcript levels in different tissues from SMNΔ7 mice (Fig. 4f).

Although extraneous for therapeutic translation, to gain insight into the impact of sustained expression of ABE8e-SpRY from AAV episomes, we assessed potential off-target editing in treated mice. We performed CHANGE-seq62 using SpRY or SpRY-HF1 nucleases37,47 with gRNA A8 on gDNA from untreated SMNΔ7 mice (Sup. Figs. 22a–22d). As expected, CHANGE-seq revealed a range of mouse genome-specific off-targets, and the use of SpRY-HF1 substantially reduced the number of nominated sites compared to SpRY treatment. Targeted sequencing of the top CHANGE-seq nominated off-target sites in brain, spinal cord, and liver of untreated or AAV-ABE treated SMA mice revealed few significant off-targets (OT3 and OT10). The efficiency of off-target editing was low (<0.1%), often at 100- or greater than 1000-fold reduced levels compared to the on-target site (Sup. Figs. 23a–23c).

To determine whether longer follow-up could result in higher SMN2 C6T editing, we analyzed a cohort of non-SMA SMNΔ7 mice (Smn+/Smn−/SMN2 or Smn+/Smn−/SMN2) at 12 weeks after a P1 ICV injection (Fig. 4g). We observed ~10% and ~8% C6T SMN2 editing on average in the brain and spinal cord, with some mice showing up to 20% on-target editing in the brain and up to 30% editing in liver (Fig. 4h). In these animals, we again observed only low levels of bystander editing (Sup. Fig. 24a). These data indicate that prolonged treatment courses enable continued editing by the dual AAV-ABE construct.

As an additional proof-of-concept, we co-injected a cohort of SMNΔ7 mice (including all genotypes) via ICV and IV routes (Fig. 4i). This strategy led to similar levels of SMN2 C6T editing in the brain and spinal cord compared to mice in cohort 1 injected only via ICV (Fig. 4e), but with increased editing in other tissues such as the liver and heart (Fig. 4j and Sup. Figs. 24b–24d). We observed greater than 50% on-target editing in the livers of some mice (Fig. 4j), suggesting that the ABE8e-SpRY with gRNA A8 can efficiently install C6T edits in vivo when delivery is not limiting. Given the relatively high levels of editing in this cohort, we analyzed potential molecular and phenotypic improvements in SMA mice. We detected SMN protein expression in the livers of treated SMA mice via two separate methods (Sup. Figs. 25a and 25b), although these methods were not sensitive enough to detect SMN changes in other tissues. Furthermore, we observed increased gains in body mass and improved motor function over time in treated mice when compared to untreated SMA mice (Figs. 4k and 4l), which was not noted in our ICV-only cohorts (Sup. Note 7). We also observed a modest (30%) but significant (p = 0.01) increased survival rate in treated SMA mice when compared to untreated SMA mice (Fig. 4m). Interestingly, these data corroborate with previous observations in mice showing that peripheral SMN restoration is essential for and can potentiate phenotypic recovery in SMA mice15.

Lastly, we analyzed the indel levels in the brains, spinal cords, and livers of mice from all three cohorts analyzed in this study. Notable indels compared to background (~0.4%) were only observed in the liver from the third cohort co-injected via ICV and IV routes (Sup. Fig. 26a–26c). Corroborating previous data from transfections in cells, these in vivo data demonstrate that indels that accompany our ABE-mediated C6T edits are typically minimal. Together, these results reveal that the delivery of an optimized ABE via a dual-AAV vector approach can results in efficient and precise SMN2 C6T editing in vivo in an SMA mouse model.

Discussion

SMA is a progressive neuromuscular disease caused by mutations in the SMN1 gene that remains a leading cause of infantile death worldwide. Type 1 SMA is the most frequent clinical subtype accounting for more than 50% of cases, characterized by severe denervation that causes untreated patients to die early in life74,75. Fortunately, extensive investigation into SMA therapeutics has culminated in FDA approved medicines with striking benefits for patients (risdiplam, nusinersen, and onasemnogene abeparvovec). These therapies have profoundly altered the trajectory of newborns with SMA. In spite of this, each therapy has limitations including strict dosing regimens8, and open questions surrounding toxicity76, efficiency in cells that may play an important role in SMA progression15,77–79, and long-term efficacy since mammalian cells tend to silence transgenes while maintaining endogenous genes at homeostatic levels80. Together, these limitations underscore and motivate the need for continued advances in genetic therapies. Early indications from clinical trials utilizing genome editing technologies to treat other diseases indicate that one-time persistent treatments may be within reach81,82.

Here we describe the optimization of pan-SMA mutation base editing approaches within the paralogous SMN2 gene irrespective of the patient SMN1 mutation. By leveraging our previously described broad targeting enzyme SpRY, we identified a set of BEs and gRNAs capable of positioning the BE edit window over the SMN2 exon 7 C6T base, leading to high editing efficiencies in HEK 293T cells and patient-derived fibroblasts. Specific C6T editing led to restoration of SMN2 mRNA and protein expression, and this strategy was translatable to in vivo experiments in mice via dual AAV vector delivery. Importantly, this approach had high apparent specificity, as we observed minimal unwanted indel or bystander edits at the on-target site, and few genome-wide off-target edits in transient transfections of human SMA fibroblasts or in in vivo AAV-ABE-treated mice. We also demonstrated that our ABE8e-SpRY approach is compatible with improved specificity variants that reduce off-target DNA editing, and with strategies previously demonstrated to reduce RNA off-target editing36,48. The low levels of off-target editing in fibroblasts compared to HEK 293T cells that we and others67 have observed merits further investigation; although HEK 293T cells facilitate rapid optimization of different base editor and gRNA combinations, their use for specificity assays may identify a superset of potential off-target edits compared to other cell lines (e.g. patient-derived primary cells). Taken together, our datasets suggest that the use of PAMless BEs in certain contexts may enable target-specific editing, encouraging additional investigation to leverage their superior flexibility to correct a range of disease-causing sequences.

We detailed several distinct base editing approaches to modify SMN2, including the installation of a specific edit within exon 7 C6T, or the disruption of ISSs or ESSs within intron 7. These approaches offer several advantages over prior genome editing pursuits. The design of SMN2 editing strategies capable of treating all patients with SMA obviates the necessity of optimizing patient-specific medicines for the individual SMN1 mutations or deletions. Base editing approaches that are not reliant on nucleases should avoid unwanted DSB-related consequences27–31. A previous study24 described ISSs knockout methods that could potentially introduce large deletions (>600 kb) between the SMN1 and SMN2 genes in patients (who are not SMN1-null), or between duplicated SMN2 copies on the same chromosome. Notably, our ISS-targeting strategy with BEs capitalizes on the same mechanism targeted by the FDA-approved ASO nusinersen, suggesting that our proof-of-concept editing experiments should enhance SMN protein levels as previously shown using nucleases24. Beyond the three main approaches we outlined herein, additional splicing-regulatory elements including potential ISSs were recently described that may also serve as appropriate base editing targets83. In addition, in comparison to our C6T and ISS editing approaches that are translationally silent, it is notable that other ESS-targeting approaches pursued in previous studies54 will induce non-synonymous amino acid changes of unknown functional consequences.

Via dual AAV-vector delivery of ABE8e-SpRY, we achieved editing in the primary target tissues for reversing SMA pathology including spinal cord and brain, with higher editing levels observed after longer periods. Overall, the in vivo editing efficiency in bulk tissues (i.e. homogenized brain) was similar to other studies that delivered base editors via ICV injections in neonatal mice via AAV vectors or engineered virus-like particles (eVLPs)68,73. Future experiments that assess alternate delivery vehicles (e.g. AAV vectors with improved CNS transduction84–86, eVLPs, or nanoparticles), additional injection paradigms or routes (e.g. in utero87), or longer time points may lead to higher levels of editing in both the CNS and peripheral tissues. Furthermore, different approaches may also provide an extended therapeutic window in the severe SMNΔ7 mouse model for expression of the ABE8e-SpRY to perform C6T editing prior to irreversible pathology. For instance, the use of other SMA models and the exploration of co-therapies using small molecules or ASOs15,88–90 may enable enhanced base editing and phenotypic recovery in vivo. A recent study performed a long-term experiment involving co-administration of nusinersen combined with a similar in vivo ABE-mediated SMN2 C6T editing strategy, seeking to extend mouse lifespan by providing an extended window for genome editing prior to onset of pathology91. Indeed, nusinersen extended the therapeutic window of SMNΔ7 mice sufficiently to permit phenotypic improvements resulting from C6T editing in this severe SMA mouse model. When comparing our C6T base editing approach to the optimal base editor from this other contemporary study, we observed comparable levels of on-target editing (Fig. 1g). Finally, the continued development of improved genome editing technologies, including those capable of more efficient and specific editing at non-canonical PAMs45,61, may improve the efficacy and safety of targeting.

Outlook

In summary, we developed a base editing approach to treat SMA by modifying SMN2 to increase SMN expression. Compared to other approved SMA therapies, genome editing technologies offer hope for long-lasting therapeutic effects. More broadly, our work underscores how highly versatile CRISPR enzymes like SpRY can be leveraged to create specific genetic edits in model organisms92, establishing a blueprint to extend this approach to additional neuromuscular disorders and other classes of disease.

Methods

Plasmids and oligonucleotides

Target site sequences for sgRNAs are available in Supplementary Table 3. Plasmids used in this study are described in Supplementary Table 4; new plasmids generated during this study have been deposited with Addgene (https://www.addgene.org/Benjamin_Kleinstiver/). Oligonucleotide sequences are available in Supplementary Table 5. Various ABE-SpRY plasmids were generated by subcloning the ABE8e or ABE8.20m35,36 deaminase sequence (Twist Biosciences) into the NotI and BglII sites of pCMV-T7-ABEmax(7.10)-SpRY-P2A-EGFP (RTW5025; Addgene plasmid 140003) via isothermal assembly93. We also similarly generated ABE8e and ABE8.20 versions of wild-type SpCas9, SpG, and SpCas9-NRRH, SpCas9-NRTH and SpCas9-NRCH, as well as ABE8e versions of SpCas9 and SpRY bearing HF1 mutations (N497A/R661A/Q695A/Q926A) or the HiFi mutation (R691A)37,44,46,47. Expression plasmids for human U6 promoter-driven sgRNAs were generated by annealing and ligating duplexed oligonucleotides corresponding to spacer sequences into BsmBI-digested pUC19-U6-BsmBI_cassette-SpCas9_sgRNA (BPK1520; Addgene plasmid 65777). Various Npu intein-split ABE constructs were cloned into N- and C-terminal AAV vectors (Addgene plasmids 137177 and 137178, respectively). The N-terminal vector was modified to include the ABE8e domain and additionally include the A61R mutation for SpRY. The C-terminal vector was modified to encode gRNAs A7, A8, and A10 and optionally to include the remainder of the SpRY mutations.

Cell culture and transfections

Human HEK 293T cells (American Type Culture Collection; ATCC) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (HI-FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Samples of supernatant media from cell culture experiments were analyzed monthly for the presence of mycoplasma using MycoAlert PLUS (Lonza).

For HEK 293T human cell experiments, transfections were performed 20 hours following seeding of 2×104 HEK 293T cells per well in 96-well plates. Transfections containing 70 ng of ABE expression plasmid and 30 ng sgRNA expression plasmid mixed with 0.72 μL of TransIT-X2 (Mirus) in a total volume of 15 μL Opti-MEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific), incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature, and distributed across the seeded HEK 293T cells. Experiments were halted after 72 hours and genomic DNA (gDNA) was collected by discarding the media, resuspending the cells in 100 μL of quick lysis buffer (20 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 5% glycerol, 25 mM DTT, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 60 ng/μL Proteinase K (New England Biolabs; NEB)), heating the lysate for 6 minutes at 65 °C, heating at 98 °C for 2 minutes, and then storing at −20 °C.

Fibroblasts were derived from skin biopsies from five different patients with SMA. SMA type, SMN2 copy number and age at skin biopsy are provided in Fig. 2a. Fibroblasts were obtained from the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) SPOT SMA Longitudinal Population Database Repository (LPDR) database. Written informed consent was obtained from each legal parent under the institutional ethics review board at the Massachusetts General Hospital (protocol #2016P000469) for each skin biopsy. Unique MGH IDs for fibroblasts lines 1 to 5 are #480, 570, 579, 603 and 571, respectively. Fibroblasts were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% HI-FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. For experiments involving fluorescence-activated cell sorting, the media was modified to contain 20% HI-FBS for recovery after sorting. Fibroblasts were transfected with Lipofectamine LTX (ThermoFisher) to deliver separate plasmids encoding ABE8e-SpRY-P2A-EGFP and gRNA A8. Transfections were performed with a non-targeting gRNA to establish a “control” line and naïve cells were untreated. Approximately 48 hours after transfection, GFP+ fibroblasts were sorted (MGB HSCI CRM Flow Cytometry Core; BD FACS AriaIII cell sorter) and seeded into a pooled GFP+ population to grow for an additional 7 days. Two additional passages were performed to expand the sorted cells, which were then used to extract gDNA as described above at passages 3, 4, 5, and 6. In addition, extractions at passages 4, 5, and 6 were performed to extract RNA using the RNeasy Plus Universal Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and protein using an SMA enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Life Sciences Inc., Farmingdale, NY; ADI-900-209).

Assessment of ABE activities in human cells

The efficiency of genome modification by ABEs were determined by next-generation sequencing using a 2-step PCR-based Illumina library construction method, similar to as previously described37. Briefly, genomic loci were amplified using approximately 50–100 ng of gDNA, Q5 High-fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB), and PCR-1 primers (Supplementary Table 5) with cycling conditions of 1 cycle at 98 °C for 2 min; 35 cycles of 98 °C for 10 sec, 58 °C for 10 sec, 72 °C for 20 sec; and 1 cycle of 72 °C for 1 min. PCR products were purified using paramagnetic beads prepared as previously described94,95. Approximately 20 ng of purified PCR-1 products were used as template for a second round of PCR (PCR-2) to add barcodes and Illumina adapter sequences using Q5 and primers (Supplementary Table 5) and cycling conditions of 1 cycle at 98 °C for 2 min; 10 cycles at 98 °C for 10 sec, 65 °C for 30 sec, 72 °C 30 sec; and 1 cycle at 72 °C for 5 min. PCR products were purified prior to quantification via capillary electrophoresis (Qiagen QIAxcel), normalization, and pooling. Final libraries were quantified by qPCR using the KAPA Library Quantification Kit (Complete kit; Universal) (Roche) and sequenced on a MiSeq sequencer using a 300- cycle v2 kit (Illumina).

On-target genome editing activities were determined from sequencing data using CRISPResso2 (ref. 96) in pooled mode with custom input parameters for ABEs: -min_reads_to_use_region 100 --quantification_window_size 10 --quantification_window_center −10 --base_editor_output --min_frequency_alleles_around_cut_to_plot 0.05. Since amplification of SMN2 also amplifies SMN1, final levels of editing were calculated as: ([%G in edited samples] − [%G in control samples]) / [%A in control samples] (Supplementary Table 6).

Assessment of SMN transcript levels

RNA was extracted from fibroblasts using the RNeasy Plus Universal Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). RNA was reverse transcribed using the RT2 First Strand Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). For ddPCR reactions, cDNA was normalized to 2 ng/μL and each ddPCR reaction contained 12 ng of cDNA, 250 nM of each primer and 900 nM probe (Supplementary Table 5), and ddPCR supermix for probes (no dUTP) (BioRad). Droplets were generated using a QX200 Automated Droplet Generator (BioRad). Thermal cycling conditions were: 1 cycle at 95 °C for 10 min; 40 cycles at 94 °C for 30 sec, 58 °C for 1 min; and 1 cycle at 98 °C for 10 min; and hold at 4 °C. PCR products were analyzed using a QX200 Droplet Reader (BioRad) and absolute concentration was determined using QuantaSoft (v1.7.4). SMN exon 7 expression was calculated relative to the housekeeping gene (GAPDH) or total SMN transcript levels (exon 1–2 junction expression).

Assessment of SMN protein levels

SMN protein levels were measured using an SMN-specific ELISA (Life Sciences Inc., Farmingdale, NY; ADI-900-209). Sample buffer provided with the ELISA kit was used to extract protein. In addition, SMN, PTEN and GAPDH protein levels were determined by immunoblotting as previously described17 with few modifications. For immunoblotting, cells were lysed using the buffer provided in the ELISA kit. In each well, 20 μg of protein was loaded in a 4–20% precast protein gel (Biorad, #4561096) and subjected to electrophoresis. Proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane and blocked for 1 h at room temperature in Odyssey blocking buffer (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE). Membranes were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Primary antibodies were used to probe for SMN (BD Biosciences; 610647), PTEN (Cell Signaling; #9552) and GAPDH (Cell Signaling; #2118). Membranes were imaged using a ChemiDoc Touch System (Bio-Rad, USA) or the LI-COR Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR, Inc., USA). SMN and PTEN expression were normalized by GAPDH expression.

Off-target analysis

Circularization for high-throughput analysis of nuclease genome-wide effects by sequencing (CHANGE-seq) was performed as previously described62. Briefly, CHANGE-seq library preparation was performed on wild-type gDNA extracted from each of the five SMA-fibroblast lines (used for the on-target analysis) and liver from SMA mice using the Gentra PureGene Tissue Kit (Qiagen). Approximately 5 μg of purified gDNA per CHANGE-seq reaction was tagmented with a custom Tn5-transposome62 to an average length of 400 bp, gap repaired with KAPA HiFi HotStart Uracil+ Ready Mix (Roche) and treated with a mixture of USER enzyme and T4 polynucleotide kinase (NEB). DNA was circularized at a concentration of 5 ng/μL with T4 DNA ligase (NEB), and treated with a cocktail of exonucleases, Lambda exonuclease (NEB), Exonuclease I (NEB) and Plasmid-Safe ATP-dependent DNase (Lucigen) to enzymatically degrade remaining linear DNA molecules. sgRNAs (Synthego) A7, A8, and A10 (Supplementary Table 3) were re-folded prior complexation with SpCas9 (Cas9 Nuclease, S. pyogenes; NEB), SpRY, or SpRY-HF1 (the latter two purified as previously described97) at a nuclease:sgRNA ratio of 1:3 to ensure full ribonucleoprotein complexation. In vitro cleavage reactions were performed in a 50 μL volume with NEB Buffer 3.1, 90 nM SpCas9, SpRY, or SpRY-HF1 protein, 270 nM of synthetic sgRNA and 125 ng of exonuclease treated circularized DNA. Digested products were treated with proteinase K (NEB), A-tailed (using KAPA High Throughput Library Preparation Kit; Roche), ligated with a hairpin adapter (NEB), treated with USER enzyme (NEB) and amplified by PCR using KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix (Roche). Completed libraries were quantified by qPCR using KAPA Library Quantification kit (Complete kit; Universal) (Roche) and sequenced with 150 bp paired-end reads on an Illumina NextSeq 550 instrument. Data analysis was conducted as previously described62 (Supplementary Table 2).

For validation of potential off-target A-to-G editing, we selected the top 34 off-target sites with the highest average normalized CHANGE-seq read counts across the SpRY-A8 and SpRY-HF1-A8 treatments of the five SMA-fibroblasts experiments. Primers were designed for each target site using Primer3 (ref. 98) or were designed manually using genome.ucsc.edu and Geneious (v2021.2.2) for amplicons that failed to be designed by Primer3. For validation of potential off-target editing, gDNA was used as template for PCRs from three fibroblast cell lines (IDs 1, 2, and 3) that were either untreated or edited with ABE8e-SpRY and gRNA A8, and gDNA from untreated HEK 293T cells or those edited with ABE8e-SpRY and gRNA A8 or ABE8e-SpRY-HF1 and gRNA A8. Off-target sites were amplified from ~100 ng gDNA using primers (Supplementary Table 5) and the PCR-1 parameters described above with modified cycling conditions where appropriate (Supplementary Table 5). Following PCR-1, amplicons were cleaned up, quantified, and subject to library construction using the KAPA HyperPrep Kit (Roche) with Illumina-competent adapters (Supplementary Table 5. Amplicons were sequenced and data analyzed as described above for assessment of ABE activities in human cells. Statistical analyses were conducted using Graph Pad Prism 8 (Graph Pad Software Inc.) (Supplementary Table 2). Multiple t-tests were used to compare groups. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

AAV production

For tissue transduction experiments, AAV9 and AAV-F vectors expressing eGFP were produced in-house. The AAV9 capsid was encoded in the pAR9 rep/cap vector kindly provided by Dr. Miguel Sena-Esteves at the University of Massachusetts Medical School (Worcester, MA). AAV-F69,99 is an engineered AAV9-based capsid in pAR9 (rep/cap) (Addgene plasmid 166921). AAV production was performed as previously described69. Briefly, HEK 293T cells were transfected using polyethylenimine and three plasmids encoding the AAV-rep/cap for either AAV9 or AAV-F, an adenovirus helper plasmid (pAdΔF6; Addgene plasmid 112867), and an ITR-flanked AAV transgene expression plasmid AAV-CAG-eGFP (provided by Dr. Miguel Sena-Esteves). The latter plasmid contains AAV inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) flanking the CAG expression cassette which consists of a hybrid CMV-IE enhancer, chicken β-actin (CBA) promoter, a beta actin exon, chimeric intron, eGFP cDNA, a woodchuck hepatitis virus post-translational response element (WPRE) and tandem SV40 and bGH poly-A signal sequences. Cell lysates as well as polyethylene glycol (PEG) precipitated vector from culture media were harvested 68–72 hr post transfection and purified by ultracentrifugation of an iodixanol density gradient. Iodixanol was removed and buffer exchanged to phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.001% Pluronic F68 (Gibco) using 7 kDa molecular weight cutoff Zeba desalting columns (ThermoFisher Scientific). AAV was concentrated using Amicon Ultra-2 100 kDa MWCO ultrafiltration devices (Millipore Sigma). Vector titers in vg/mL were determined by qPCR using an ABI Fast 7500 Real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems), with Applied Biosystems TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix 2x, No AmpErase UNG (ThermoFisher Scientific) using primers and a probe to the bovine growth hormone (bGH) polyadenylation signal sequence (Supplementary Table 5), with cycling parameters of 95 °C for 20 s followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 3 s and 60 °C for 30 s. Titers were interpolated from a standard curve made with a XbaI-linearized AAV-CAG-eGFP plasmid. Vectors were pipetted into single-use aliquots and stored at −80°C.

For genome editing experiments, two AAV9 vectors encoding ABE8e-SpRY split into N-term and C-terminal fragments via an Npu intein (as described above and similar to as previously reported68) paired with gRNA A8 were packaged by PackGene Biotech Inc. (Worcester, MA).

In vivo experiments in mice

SMNΔ7 mice (FVB.Cg-Grm7Tg(SMN2)89Ahmb Smn1tm1Msd Tg (SMN2*delta7) 4299Ahmb/J) were housed and bred at the University of Ottawa Animal Care Facility. Mice were housed in a 12h/12h light/dark cycle with access to food and water ad libitum. This study was approved by the Animal Care and Veterinary Services of the University of Ottawa, ON, Canada and all animals were cared for according to the Canadian Council on Animal Care.

For tissue transduction tests, intracerebroventricular (ICV) injections were performed in two litters of SMNΔ7 mice at postnatal day 1 (P1). For each mouse, 3 μL ICV injections contained 2 × 1010 vg AAV9-EGFP or AAV-F-EGFP. Mice were sacrificed at P13. Brain and spinal cord were collected, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (overnight at 4 °C), transferred to 30% sucrose (overnight at 4 °C), embedded in OCT, and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Cryosections of 16 μm were mounted on slides and kept at −20°C until staining, when the slides were air dried at room temperature (RT) for 24 h and rinsed with PBS for 3 × 5 min. Samples were permeabilized in 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 25 min, then incubated in blocking solution (1% BSA, 10% goat serum, and 0.2% Triton X-100) for 40 min at room temperature (RT). Sections were then incubated with anti-GFP antibody at a dilution of 1:1,000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #A11122) in blocking solution overnight at 4 °C. After the first antibody incubation, slides were washed 3 × 10 min with PBS at RT. Samples were then incubated with Alexa Fluor goat anti-rabbit 488 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #A-11008) at a dilution of 1:100 for 1 h at RT. Nuclei were counterstained with 40,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) 1:1,000 in TBST for 5 min. Finally, slides were carefully rinsed 3 × 5 min with PBS and slides were mounted with Fluorescent Mounting Medium (Dako) and examined under fluorescence using a Zeiss microscope equipped with an AxioCam HRm camera.

For western blot analysis, tissue processing and immunoblotting were performed as previously described100. After euthanasia at P13, brain, spinal cord, liver, and heart were dissected, and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Protein was extracted from frozen tissue by homogenization of tissue with RIPA lysis buffer and PMSF (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA). Protein concentrations of samples were determined using Bradford Assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). 20 μg of protein was loaded onto a 12% acrylamide gel and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane (Immobilon-FL, Millipore, Burlington, MA) and blocked for 1 h at room temperature in Odyssey blocking buffer (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE). Blots were incubated with anti-GFP (1:2,000; A11122 ThermoFisher Scientific) or Anti-SMN2 human (1:2000; MABE230 Sigma). Signals were detected with Odyssey CLx (Li-Cor). Raw values were normalized by geometric mean and used for subsequent housekeeping normalization (α-tubulin values; 1:10,000 mouse anti-tubulin; Abcam ab4074) from the same blot.

For genome editing experiments, 3 μL ICV or IV injections were performed across three different cohorts of SMNΔ7 mice at P1 with a dose of 3 × 1010 vg total N- and C-terminal AAV9 constructs per route. Control litters of SMNΔ7 mice were left uninjected. Mice were weighed every 2 days and sacrificed at P13 (cohort 1), after 12 weeks (cohort 2) or at the moribund stage between 13- and 18-days post injection (cohort 3) for collection of brain, spinal cord, liver, heart, and skeletal muscle. DNA was extracted from each tissue using the Agencourt DNAdvance kit (Beckman Coulter, CA) and RNA was extracted from brain, spinal cord and liver from cohort 1 using the RNeasy Plus Universal Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). On-target editing in the tissues was analyzed from extracted gDNA by amplifying the human SMN sequence as described above for assessment of ABE activities in human cells, and SMN2 exon 7 expression was determined as described above for patient fibroblasts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the following individuals: C. Tou (ddPCR), E. King and D. Ramos (AAV and mouse tissue extraction discussions), J. Ferreira da Silva and L. Hille (data analysis), L. Ma and N. Kim (cloning), R. Silverstein (coding and data analysis), H. Stutzman (gRNA cloning), and E. Eichelberger, R. Spellman, and W. das Neves (cell culture). We acknowledge M. Mabuchi and G.B. Robb for providing purified SpRY and SpRY-HF1 protein (generated as described previously97). This work was supported by a Charles A. King Trust Postdoctoral Research Fellowship, Bank of America, N.A., Co-Trustees (C.R.R.A.), a James L. and Elisabeth C. Gamble Endowed Fund for Neuroscience Research / Mass General Neuroscience Transformative Scholar Award (C.R.R.A.), a MGH Physician/Scientist Development Award (C.R.R.A.), a Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Executive Committee on Research (ECOR) Fund for Medical Discovery Fundamental Research Fellowship Award (K.A.C.), a Frederick Banting and Charles Best CIHR Doctoral Research Award (A.R.), a St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital Collaborative Research Consortium on Novel Gene Therapies for Sickle Cell Disease (S.Q.T.), a Muscular Dystrophy Association grant 575466 (R.K.), a Muscular Dystrophy Canada grant (R.K.), a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) grant PJT-156379 (R.K.), an MGH Innovation Discovery Grant (to C.R.R.A. and B.P.K.), an MGH ECOR Howard M. Goodman Fellowship (B.P.K.), and National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01DC017117 (C.A.M.), U01AI157189 (S.Q.T.), P01HL142494 (B.P.K.) and DP2CA281401 (B.P.K.).

Footnotes

Competing interests

C.R.R.A., K.A.C., K.J.S., and B.P.K. are inventors on a patent application filed by Mass General Brigham (MGB) that describes genome engineering technologies to treat SMA. S.Q.T. and C.R.L are co-inventors on a patent application describing the CHANGE-seq method. S.Q.T. is a member of the scientific advisory board of Kromatid, Twelve Bio, and Prime Medicine. C.A.M. has a financial interest in Sphere Gene Therapeutics, Inc., Chameleon Biosciences, Inc., and Skylark Bio, Inc., companies developing gene therapy platforms. C.A.M.’s interests were reviewed and are managed by MGH and MGB in accordance with their conflict-of-interest policies. C.A.M. has a filed patent application with claims involving the AAV-F capsid. B.P.K. is an inventor on additional patents or patent applications filed by MGB that describe genome engineering technologies. B.P.K. is a consultant for EcoR1 capital and is on the scientific advisory board of Acrigen Biosciences, Life Edit Therapeutics, and Prime Medicine. S.Q.T. and B.P.K. have financial interests in Prime Medicine, Inc., a company developing therapeutic CRISPR-Cas technologies for gene editing. B.P.K.’s interests were reviewed and are managed by MGH and MGB in accordance with their conflict-of-interest policies. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Data availability

Plasmids from this study have been made available through Addgene.

Primary datasets are available in Supplementary Tables 1, 2, 6, and 7. Sequencing datasets will be deposited with the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA).

Some aspects of schematics in Figure 4, and Supplementary Figures 20 and 21, were adapted from vector art provided by Servier Medical Art by Servier, which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).”)

References

- 1.Groen EJN, Talbot K & Gillingwater TH Advances in therapy for spinal muscular atrophy: promises and challenges. Nat Rev Neurol 14, 214–224 (2018). 10.1038/nrneurol.2018.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergin A et al. Identification and characterization of a mouse homologue of the spinal muscular atrophy-determining gene, survival motor neuron. Gene 204, 47–53 (1997). 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00510-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogino S & Wilson RB Genetic testing and risk assessment for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). Hum Genet 111, 477–500 (2002). 10.1007/s00439-002-0828-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crawford TO et al. Evaluation of SMN protein, transcript, and copy number in the biomarkers for spinal muscular atrophy (BforSMA) clinical study. PLoS One 7, e33572 (2012). 10.1371/journal.pone.0033572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mailman MD et al. Molecular analysis of spinal muscular atrophy and modification of the phenotype by SMN2. Genet Med 4, 20–26 (2002). 10.1097/00125817-200201000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feldkotter M, Schwarzer V, Wirth R, Wienker TF & Wirth B Quantitative analyses of SMN1 and SMN2 based on real-time lightCycler PCR: fast and highly reliable carrier testing and prediction of severity of spinal muscular atrophy. Am J Hum Genet 70, 358–368 (2002). 10.1086/338627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finkel RS et al. Treatment of infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy with nusinersen: a phase 2, open-label, dose-escalation study. Lancet 388, 3017–3026 (2016). 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31408-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finkel RS et al. Nusinersen versus Sham Control in Infantile-Onset Spinal Muscular Atrophy. N Engl J Med 377, 1723–1732 (2017). 10.1056/NEJMoa1702752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mercuri E et al. Nusinersen versus Sham Control in Later-Onset Spinal Muscular Atrophy. N Engl J Med 378, 625–635 (2018). 10.1056/NEJMoa1710504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sturm S et al. A phase 1 healthy male volunteer single escalating dose study of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of risdiplam (RG7916, RO7034067), a SMN2 splicing modifier. Br J Clin Pharmacol 85, 181–193 (2019). 10.1111/bcp.13786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Darras BT et al. Risdiplam-Treated Infants with Type 1 Spinal Muscular Atrophy versus Historical Controls. N Engl J Med 385, 427–435 (2021). 10.1056/NEJMoa2102047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baranello G et al. Risdiplam in Type 1 Spinal Muscular Atrophy. N Engl J Med 384, 915–923 (2021). 10.1056/NEJMoa2009965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ratni H, Scalco RS & Stephan AH Risdiplam, the First Approved Small Molecule Splicing Modifier Drug as a Blueprint for Future Transformative Medicines. ACS Med Chem Lett 12, 874–877 (2021). 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.0c00659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Vivo DC et al. Nusinersen initiated in infants during the presymptomatic stage of spinal muscular atrophy: Interim efficacy and safety results from the Phase 2 NURTURE study. Neuromuscul Disord 29, 842–856 (2019). 10.1016/j.nmd.2019.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hua Y et al. Peripheral SMN restoration is essential for long-term rescue of a severe spinal muscular atrophy mouse model. Nature 478, 123–126 (2011). 10.1038/nature10485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lipnick SL et al. Systemic nature of spinal muscular atrophy revealed by studying insurance claims. PLoS One 14, e0213680 (2019). 10.1371/journal.pone.0213680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nery FC et al. Impaired kidney structure and function in spinal muscular atrophy. Neurol Genet 5, e353 (2019). 10.1212/NXG.0000000000000353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim JK et al. Muscle-specific SMN reduction reveals motor neuron-independent disease in spinal muscular atrophy models. J Clin Invest 130, 1271–1287 (2020). 10.1172/JCI131989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mendell JR et al. Single-Dose Gene-Replacement Therapy for Spinal Muscular Atrophy. N Engl J Med 377, 1713–1722 (2017). 10.1056/NEJMoa1706198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomsen G et al. Biodistribution of onasemnogene abeparvovec DNA, mRNA and SMN protein in human tissue. Nat Med 27, 1701–1711 (2021). 10.1038/s41591-021-01483-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alves CRR et al. Whole blood survival motor neuron protein levels correlate with severity of denervation in spinal muscular atrophy. Muscle Nerve 62, 351–357 (2020). 10.1002/mus.26995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Alstyne M et al. Gain of toxic function by long-term AAV9-mediated SMN overexpression in the sensorimotor circuit. Nat Neurosci (2021). 10.1038/s41593-021-00827-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou M et al. Seamless Genetic Conversion of SMN2 to SMN1 via CRISPR/Cpf1 and Single-Stranded Oligodeoxynucleotides in Spinal Muscular Atrophy Patient-Specific Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Hum Gene Ther 29, 1252–1263 (2018). 10.1089/hum.2017.255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li JJ et al. Disruption of splicing-regulatory elements using CRISPR/Cas9 to rescue spinal muscular atrophy in human iPSCs and mice. Natl Sci Rev 7, 92–101 (2020). 10.1093/nsr/nwz131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miccio A, Antoniou P, Ciura S & Kabashi E Novel genome-editing-based approaches to treat motor neuron diseases: Promises and challenges. Mol Ther 30, 47–53 (2022). 10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh NN, Howell MD, Androphy EJ & Singh RN How the discovery of ISS-N1 led to the first medical therapy for spinal muscular atrophy. Gene Ther 24, 520–526 (2017). 10.1038/gt.2017.34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kosicki M, Tomberg K & Bradley A Repair of double-strand breaks induced by CRISPR-Cas9 leads to large deletions and complex rearrangements. Nat Biotechnol 36, 765–771 (2018). 10.1038/nbt.4192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leibowitz ML et al. Chromothripsis as an on-target consequence of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing. Nat Genet 53, 895–905 (2021). 10.1038/s41588-021-00838-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alanis-Lobato G et al. Frequent loss of heterozygosity in CRISPR-Cas9-edited early human embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 118 (2021). 10.1073/pnas.2004832117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Enache OM et al. Cas9 activates the p53 pathway and selects for p53-inactivating mutations. Nat Genet 52, 662–668 (2020). 10.1038/s41588-020-0623-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morgens DW et al. Genome-scale measurement of off-target activity using Cas9 toxicity in high-throughput screens. Nat Commun 8, 15178 (2017). 10.1038/ncomms15178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anzalone AV, Koblan LW & Liu DR Genome editing with CRISPR-Cas nucleases, base editors, transposases and prime editors. Nat Biotechnol 38, 824–844 (2020). 10.1038/s41587-020-0561-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gaudelli NM et al. Programmable base editing of A*T to G*C in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Nature 551, 464–471 (2017). 10.1038/nature24644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Komor AC, Kim YB, Packer MS, Zuris JA & Liu DR Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature 533, 420–424 (2016). 10.1038/nature17946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gaudelli NM et al. Directed evolution of adenine base editors with increased activity and therapeutic application. Nat Biotechnol 38, 892–900 (2020). 10.1038/s41587-020-0491-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richter MF et al. Phage-assisted evolution of an adenine base editor with improved Cas domain compatibility and activity. Nat Biotechnol 38, 883–891 (2020). 10.1038/s41587-020-0453-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walton RT, Christie KA, Whittaker MN & Kleinstiver BP Unconstrained genome targeting with near-PAMless engineered CRISPR-Cas9 variants. Science 368, 290–296 (2020). 10.1126/science.aba8853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koblan LW et al. Improving cytidine and adenine base editors by expression optimization and ancestral reconstruction. Nat Biotechnol 36, 843–846 (2018). 10.1038/nbt.4172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ma H et al. Pol III Promoters to Express Small RNAs: Delineation of Transcription Initiation. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 3, e161 (2014). 10.1038/mtna.2014.12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao Z, Harwig A, Berkhout B & Herrera-Carrillo E Mutation of nucleotides around the +1 position of type 3 polymerase III promoters: The effect on transcriptional activity and start site usage. Transcription 8, 275–287 (2017). 10.1080/21541264.2017.1322170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim S, Bae T, Hwang J & Kim JS Rescue of high-specificity Cas9 variants using sgRNAs with matched 5’ nucleotides. Genome Biol 18, 218 (2017). 10.1186/s13059-017-1355-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arbab M et al. Determinants of Base Editing Outcomes from Target Library Analysis and Machine Learning. Cell 182, 463–480 e430 (2020). 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim N et al. Deep learning models to predict the editing efficiencies and outcomes of diverse base editors. Nat Biotechnol (2023). 10.1038/s41587-023-01792-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller SM et al. Continuous evolution of SpCas9 variants compatible with non-G PAMs. Nat Biotechnol 38, 471–481 (2020). 10.1038/s41587-020-0412-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chatterjee P et al. A Cas9 with PAM recognition for adenine dinucleotides. Nat Commun 11, 2474 (2020). 10.1038/s41467-020-16117-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vakulskas CA et al. A high-fidelity Cas9 mutant delivered as a ribonucleoprotein complex enables efficient gene editing in human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Nat Med 24, 1216–1224 (2018). 10.1038/s41591-018-0137-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]