Abstract

Background:

Growing evidence linking social determinants of health (SDOH) to child health outcomes has prompted widespread recommendations for pediatricians to screen and refer for adverse SDOH at primary care visits. Yet there is little evidence to date demonstrating the effectiveness of practice-based SDOH screening and referral interventions on increasing family engagement with resources. This hybrid type 2 effectiveness-implementation trial aims to demonstrate the non-inferiority of a low-touch implementation strategy in order to facilitate dissemination of an existing SDOH screening and referral system (WE CARE) and demonstrate its effectiveness and sustainability in various pediatric practices.

Methods:

We recruited eighteen pediatric practices in fourteen US states through two pediatric practice-based research networks. For this stepped wedge cluster RCT, practices serve as their own controls during the Usual Care phase and implement WE CARE during the intervention phase via one of two randomized implementation strategies: self-directed, pre-recorded webinar vs. study team-facilitated, live webinar. We collect data at practice, clinician/staff, and parent levels to assess outcomes grounded in the Proctor Conceptual Model of Implementation Research. We use generalized mixed effects models and differences in proportions to compare rates of resource referrals by implementation strategy, and intention-to-treat analysis to compare odds of engagement with new resources among families enrolled in the Usual Care vs. WE CARE phases.

Discussion:

Findings from this trial may inform decisions about broader dissemination of SDOH screening systems into a diverse spectrum of pediatric practices across the US and potentially minimize the impact of adverse SDOH on children and families.

Keywords: Social determinants of health, social risks, social needs, social screening tools, pediatrics

BACKGROUND

Social determinants of health (SDOH) are defined as “the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age.”1 SDOH influence health and health inequities throughout the life course, particularly during childhood, a critical period for human growth and development.2,3 Adverse SDOH, also known as social risks, have been found to disrupt the body’s physiological stress-response systems, leading to developmental delays, infections, chronic diseases, and premature mortality.4-6

Pediatric primary care may be an optimal setting to identify and address children’s adverse SDOH given that over 95% of children in the United States (US) have health insurance coverage in 2021,7 many of whom engage in early childhood medical visits.8 The growing evidence base linking adverse SDOH to poor child health outcomes, paired with the broad reach of pediatric primary care, has prompted widespread recommendations for pediatricians to screen and refer for services to address adverse SDOH at primary care visits.9,10 Some professional societies like the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the Academic Pediatric Association (APA) encourage SDOH screening during patient encounters,10-12 and many payers, including the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, incentivize addressing patients’ adverse SDOH. Yet while many pediatric primary care practices (and health care systems at large) are implementing such social care systems, there is no gold standard approach for SDOH screening and referral and there is little evidence to date demonstrating the effectiveness of practice-based SDOH screening and referral interventions on decreasing families’ adverse SDOH.

In a prior cluster randomized trial of one SDOH screening and referral approach, WE CARE (Well child care, Evaluation, Community resources, Advocacy, Referral, Education), Garg et al. found that parents receiving WE CARE were more likely to receive (70% vs. 8%) and follow up on (39% vs. 24%) resource referrals within six months compared to families who did not receive the intervention.13 Notably, however, this prior study was conducted only in community health centers in one urban city. The current trial broadens the study to include a diverse set of rural, urban, and suburban pediatric practices located across the US. In addition, the current study compares the effectiveness of two different implementation strategies that may be utilized to disseminate WE CARE, and other SDOH screening and referral systems, to primary care practices.

The aims of the WE CARE study are to: (1) demonstrate the non-inferiority of a self-directed, pre-recorded strategy for implementing WE CARE, in comparison to a study-team facilitated, live webinar strategy; (2) demonstrate WE CARE’s effectiveness at increasing parent engagement with resources to address their identified adverse SDOH; and (3) assess the sustainability of WE CARE in pediatric practices. In this manuscript, we describe the study protocol and detail how we utilize the Proctor Conceptual Model of Implementation Research (Proctor Model) to guide the study methodology, implement WE CARE and examine outcomes at the practice, clinician/staff and parent levels.

METHODS

Conceptual Framework:

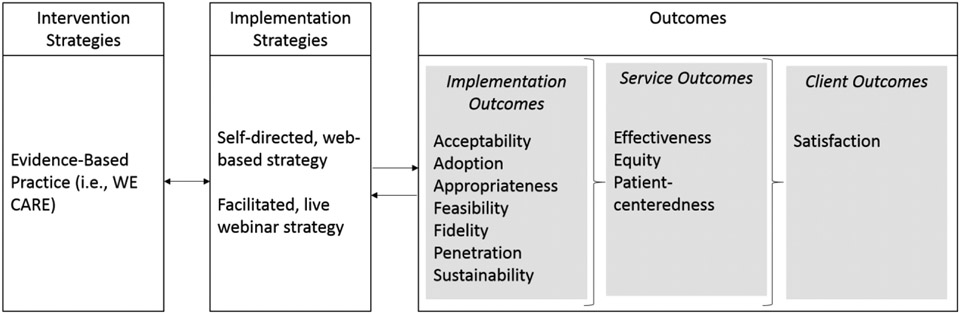

Our conceptual framework is the Proctor Conceptual Model of Implementation Research, which posits that improvements in outcomes depend on both evidence-based interventions (i.e., WE CARE) and the strategies used to implement them14 (i.e. pre-recorded training vs. live webinar training for practices) (Figure 1). In the Proctor Model, the implementation, service and client outcomes investigated are shaped by both the evidence-based intervention itself (i.e., WE CARE) and the context in which it is implemented (i.e., pediatric practices in the US). In this study, the implementation outcomes we investigate (acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, feasibility, fidelity, penetration and sustainability) will further our understanding of how to optimize implementation of WE CARE. We anticipate successful implementation will improve service outcomes by enhancing patient-centeredness and equity, and by effectively increasing parents’* receipt of referrals to and engagement with resources that address their adverse SDOH.

Figure 1.

Proctor Conceptual Model of Implementation Research, applied to WE CARE Study.

Study Design:

This is a pragmatic stepped-wedge cluster randomized controlled trial (RCT) using a hybrid type 2 effectiveness-implementation design. Practices are randomized to one of two implementation strategies (pre-recorded vs. live) used to train clinicians/staff at pediatric primary care practices, and the intervention is evaluated at the practice level.15 This design allows for simultaneous assessment of the impact of two different implementation strategies on the intervention’s fidelity, penetration, and sustainability in pediatric practices, and of the intervention’s effectiveness at increasing receipt of resources.

Study Setting:

The study is being conducted at 18 pediatric practices affiliated with two national pediatric practice-based research networks: the AAP Pediatric Research in Office Settings (PROS) Network (n=12 practices) and the APA Continuity Research Network (CORNET) (n=6 practices). PROS is the national primary-care practice-based research network of the AAP. Most PROS pediatricians/pediatric clinicians (~75%) are based in pediatric group practices and small private practices with the majority located in suburban/rural areas (64%). The overall racial/ethnic breakdown of children participating in recent PROS studies is similar to the child population estimates in the 2020 US Census. CORNET is a national practice-based research network composed of over 125 pediatric residency programs that provide care to patients across 40 states and Washington, DC. CORNET sites are academic and hospital-affiliated practices that provide care to predominantly publicly insured patients and have pediatric residents serve as primary care clinicians. Working with these two different networks allows us to investigate the unique opportunities and challenges of implementing WE CARE in a diverse array of US-based pediatric practices.

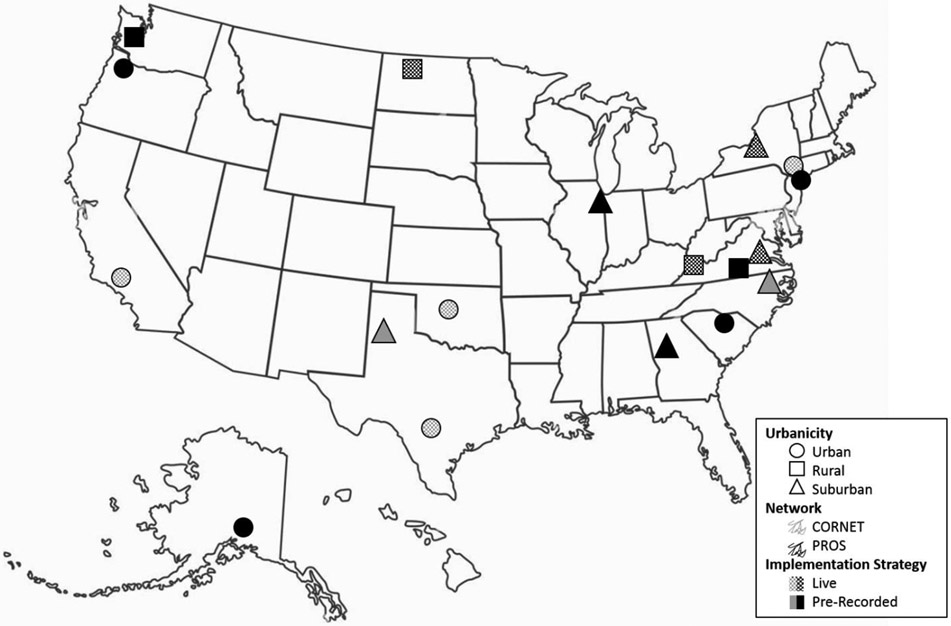

Pediatric practices were eligible to participate in the study if they: 1) accepted patients regardless of insurance status (public, private or uninsured), 2) were not a community health center, and 3) did not already routinely screen and refer for three or more of the six SDOH assessed in WE CARE (childcare, food, housing, parent education, parent employment, utilities). After enrolling in the study, practices were assigned to one of three clusters (6 practices per cluster) and randomized to one of two implementation strategies (self-directed, pre-recorded training webinars vs. study team-facilitated, live training webinars) using rolling randomization.16 The 18 study practices are located in 14 states and were purposefully selected to enhance geographic diversity and to include urban (n=8), suburban (n=6) and rural (n=4) settings. Figure 2 shows a map of the US with participating practices by network, setting and randomization assignment.

Figure 2.

Map of WE CARE study sites, coded by urbanicity, practice-based research network, and randomized implementation strategy assignment.

WE CARE SDOH Screening and Referral Intervention:

This study utilized a previously tested and validated SDOH screener. We initially identified SDOH domains from the Bright Futures pediatric intake form,17 a literature review, and a discussion with clinic staff from a pediatric primary care practice in Baltimore, Maryland, to identify relevant SDOH for limited-income families.18 The details of the intervention’s development and initial testing are described further in this section. The intervention consists of two components: 1) practice-wide administration of the WE CARE Screener (Appendix A) and 2) development and use of a Family Resource Book. The WE CARE Screener consists of brief questions aimed to identify six adverse SDOH and determine whether a parent would like assistance with addressing any of the six domains. The six SDOH addressed in the screener are childcare, food, housing, parent education, parent employment and utilities; these were selected based on prior research demonstrating their associations with child health outcomes.19-23 The Family Resource Book, created by each participating practice, consists of information sheets that list the names, contact information, and services provided by several local, state and federal resources. Information sheets are provided to parents who request help with any of the six SDOH included on the WE CARE screener, as well as the phone number of the practice encouraging families to contact their child’s care team with any questions and for additional support (see Appendix B for a sample resource information sheet). Our previous work found that this type of low-touch intervention increased parental contact18 and receipt of resources.13 Practices were trained to include approximately four resources or services per SDOH domain in order to provide families with streamlined information and prevent the paradox of choice. The WE CARE Screener and Family Resource Book information sheets are available in both English and Spanish at all sites. Practices may use their own resources to translate materials into other languages commonly spoken by their patients, although this study focuses on WE CARE screening and referral amongst English- and Spanish-speaking families only.

Practices are guided to integrate the WE CARE Screener and Family Resource Book into routine practice by adhering to three core principles. First, parents are to complete the self-administered paper screener independently at a primary care visit. This principle is consistent with research showing that individuals are more likely to disclose their needs on self-administered tools.24, 25 Second, clinicians/staff are to acknowledge and discuss the WE CARE Screener responses with parents during the same primary care visit. This principle allows for an engaging and empathizing shared decision-making process between the patient’s parents and clinicians/staff. Third, parents who indicate a need and want help are to receive a corresponding need-specific resource information sheet from their practice’s Family Resource Book. This is a unique and central principle compared to other SDOH screening approaches in that it gives respondents agency over when and how they may request help with adverse SDOH.26, 27 Table 1 presents the core components of the intervention, along with aspects of the intervention that can be tailored to meet practices’ varying needs and workflows.

Table 1.

Core components, core principles, and tailorable aspects of the WE CARE intervention.

| Core Components |

Core Principles | Tailorable Aspects |

|---|---|---|

| WE CARE Screener | Distribute self-administered WE CARE screener to parent of designated patient to complete before consultation with clinician | Practices define “designated” patients based on the age range and visit types relevant to their practice |

| Discuss WE CARE screener responses with parent during visit; document WE CARE responses in patient’s medical record | Practices determine how WE CARE screener is distributed, who reviews screener responses with parent, and how responses are recorded in patient’s medical record | |

| Family Resource Book | Provide need-specific resource information sheet from the Family Resource Book to parents who indicate a need and want help | Practices determine the format (physical or electronic) for their Family Resource Book |

| Practices decide how need-specific resources are shared with parents (e.g., physical handout, QR code) |

Implementation Strategies:

To further our aim of demonstrating the non-inferiority of the lower touch, more readily scalable and disseminatable pre-recorded strategy for implementing WE CARE, we randomly assigned practices to receive either the self-directed, pre-recorded webinar or the study team-facilitated, live webinar. Both of the implementation strategies tested in this study involve a two-part training series. The first component of the training involves teaching practice staff to identify local, state, and federal services and resources to develop the content for their Family Resource Book. Only a few selected practice members are asked to participate in this first session, including one or more required practice champions and optional additional team members with an expressed interest in participating, such as practice staff whose roles involve connecting families to resources (e.g., patient navigators, social workers). After participating in this training component, clinicians/staff are given approximately 2-4 months to prepare and submit their Family Resource Book to the study team for initial review. This review is to confirm the accuracy and clarity of the resource information prior to professional translation to Spanish, financed by the study team. This training component is consistent across the two implementation strategies.

The second component of the training varies based on assigned implementation strategy and involves teaching practices the core principles of the intervention so that they can implement it practice wide. Each practice is offered up to three sessions to view (pre-recorded) or attend (live) the training webinar, allowing for the majority of practice members to contribute to decisions regarding the integration of WE CARE into their existing workflow. Regardless of implementation strategy, practice champions facilitated the viewing of the training session and sent a list of attendees to the study team. Training materials shared with the practice include a sample Family Resource Book and “Quick Kits” containing content on introducing and assessing the WE CARE Screener with parents. While the training method varies across the two implementation strategies (pre-recorded vs. live webinars), the training contents and materials remain uniform. Table 2 compares the two implementation strategies, outlining their differences and summarizing their content similarities.

Table 2.

Similarities and differences between the live and pre-recorded webinar implementation strategies.

| Study-team facilitated, live webinar | Self-directed, pre-recorded webinar | |

|---|---|---|

| Content | • Family Resource Book Training: in-depth tutorial on identifying community resources and developing Family Resource Book • Core Training: background on WE CARE, importance of screening for adverse social determinants of health (SDOH), using the WE CARE screener and Family Resource Book, shared decision-making, and implementing WE CARE practice-wide |

|

|

|

|

| Access |

|

|

| Materials | • Example of the Family Resource Book • “Quick kit” summarizing how to introduce the WE CARE screener to families and outlining WE CARE workflow |

|

|

|

|

| Support | • Ongoing implementation support mediated by the study team | |

|

|

|

| Attendees | • Family Resource Book Training: practice champion(s) and optional additional attendees (e.g., students, local research staff, clinicians with knowledge of community resources) • Core Training: all clinicians/staff invited |

|

| Follow up |

|

|

| Duration and Sessions* |

|

|

Notably, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, these implementation strategies had to be modified from their original plan. Although the self-directed, pre-recorded webinar strategy remained the same, the live strategy was changed from an on-site, in-person training to a live webinar conducted via videoconference. This modification was required to respond to pandemic-related travel restrictions and social distancing measures recommended by US public health officials and enforced by the study team members’ institutions. No implementation strategy training had commenced prior to the pandemic; therefore, nine practices received the live webinar and nine received the pre-recorded webinar.

Phases of the Stepped-Wedge Study Design:

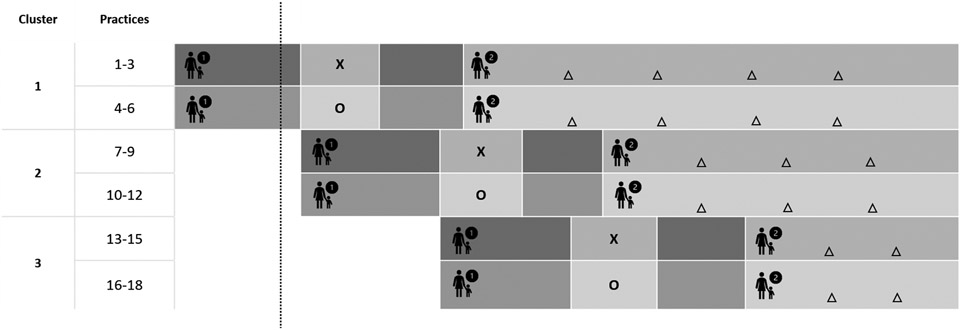

For this stepped-wedge cluster RCT, there are three clusters consisting of six practices each, for a total of 18 practices. Figure 3 shows the stepped-wedge study design with each data collection phase—the majority of which occurred after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Each cluster of practices is exposed to the intervention at a staggered interval. There are four study phases: Usual Care, Core Training, Pilot and WE CARE.

Figure 3.

Stepped-wedge cluster randomized trial design with multiple data collection points for the WE CARE study.

Please note that this figure is not to scale. The dotted line signifies when the COVID-19 pandemic began (March 2020) during the study period.

- 1st phase is Usual Care

- 2nd phase is Core Training (X= Live Webinar, O=Pre-recorded Webinar)

- 3rd phase is Pilot

- 4th is WE CARE

- Δ signifies Chart Review Period

- Non-inferiority Evaluation: Comparison of X vs. O

- Implementation Evaluation: Proportion of visits with completed screener from Chart Review

- Effectiveness Evaluation: Comparison of parent surveys in Usual Care phase vs. WE CARE phase

The Usual Care phase is a 6-month period before practices implement the intervention practice-wide. During this phase, a cohort of parents (with the goal of 70 participants per site) is recruited and enrolled. In order to be eligible, parents must be 18 years or older, read and write either English or Spanish, and be a parent or legal guardian of a child aged 2 months to 10 years attending a well-child care visit at a participating practice. For the Usual Care phase, parents complete a baseline survey at the practice and a follow-up survey approximately 3 to 4 months post-baseline via phone call with research staff or by survey link sent via email or text message, based on parent preference.

The Core Training phase is the 2 to 4-month period following the Usual Care phase during which practices identify services and resources to support families with adverse SDOH and learn about implementing WE CARE. During this phase, practices are trained via pre-recorded or live webinar training on compiling the Family Resource Book and administering the WE CARE screener.

The Pilot phase occurs immediately following completion of the Core Training phase. The Pilot phase is a 1 to 2-month period during which practices implement the WE CARE intervention and troubleshoot early barriers and challenges.

Finally, during the WE CARE phase, practices continue implementing the intervention at all well-child care visits for children aged 2 months to 10 years old. Practices may decide to expand the implementation of the intervention to other visit types (e.g., sick visits) and patients outside the study designated age range. Practices also recruit and enroll a second cohort of parents (the same goal of 70 participants per site) to complete baseline and follow-up surveys similar to participants in the Usual Care phase. To assess intervention fidelity and penetration, the study team tracks practices’ screener and referral distribution for a 90-day period within the first six months of the WE CARE phase. Additionally, depending on their assigned cluster, practices complete four (cluster 1), three (cluster 2) or two (cluster 3) semiannual chart reviews to assess fidelity, penetration and sustainability of screening and referring families.

Data Sources and Outcome Measures:

Table 3 shows each of our Proctor outcomes of interest, mapped to the evaluation tool used to examine that measure, the timing of the measure, and the stakeholder level of assessment (i.e., practice, clinician/staff or parent).

Table 3.

Proctor Conceptual Model of Implementation Research outcomes and definitions, mapped to mode, timing, and stakeholder level of collection.

| Outcome | Working Definition | Evaluation Tool | Timing | Stakeholder(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acceptability | The perception among stakeholders (e.g. consumers, providers, managers, policy makers) that an intervention is agreeable | Qualitative Interview | Post-Pilot, 12 months Post-WE CARE |

Clinician/staff |

| Evidence-based practice attitudes scale (EBPAS) - subscales of requirements, appeal | Post-Pilot, 12 months Post-WE CARE |

Clinician/staff | ||

| Adoption | The intention, initial decision, or action to try to employ a new intervention | Quarterly Check-in | Every 3 months during WE CARE phase |

Practice |

| Qualitative Interview | Post-Pilot | Clinician/staff | ||

| EBPAS – subscale of openness | Pre-Training, Post-Pilot | Clinician/staff | ||

| Appropriateness | The perceived fit or relevance of the intervention in a particular setting or for a particular target audience (provider or consumer) or issue | Qualitative Interview | Post-Pilot, 12 months Post-WE CARE |

Clinician/staff |

| Texas Christian University Workshop Evaluation | Post-Training | Clinician/staff | ||

| EBPAS – subscale of divergence | Post-Pilot, 12 months Post-WE CARE |

Clinician/staff | ||

| Feasibility | The extent to which an intervention can be carried out in a particular setting or organization | Quarterly Check-in | Every 3 months during WE CARE phase |

Practice |

| Qualitative Interview | Post-Pilot, 12 months Post-WE CARE |

Clinician/staff | ||

| Periodic Survey 90 | Pre-Training, Post-Pilot,12 months Post-WE CARE | Clinician/staff | ||

| Fidelity | The degree to which an intervention was implemented as it was designed in an original protocol, plan, or policy | Distributed WE CARE screeners and denominator | 90-day period within the first 6 months of WE CARE phase |

Practice |

| Quarterly Check-in | Every 3 months during WE CARE phase |

Practice | ||

| Chart Review | Every 6 months during WE CARE phase |

Practice | ||

| Qualitative Interview | 12 months Post-WE CARE | Clinician/staff | ||

| Penetration | The degree to which the population that is eligible to benefit from an intervention actually receives it | Distributed WE CARE screeners and denominator | 90-day period within the first 6 months of WE CARE phase | Practice |

| Chart Review | Every 6 months during WE CARE phase |

Practice | ||

| Parent Questionnaire | Index visit, 3-month follow-up | Parent | ||

| Sustainability | The extent to which an intervention is maintained or institutionalized in a given setting | Quarterly Check-in | Every 3 months during WE CARE phase |

Practice |

| Chart Review | Every 6 months during WE CARE phase |

Practice | ||

| Qualitative Interview | 12 months Post-WE CARE | Clinician/staff | ||

| Quantitative Questionnaire | 12 months Post-WE CARE | Clinician/staff | ||

| Effectiveness | Providing services based on scientific knowledge to all who could benefit, and refraining from providing services to those no likely to benefit | Parent Questionnaire | Index visit, 3-month follow-up | Parent |

| Equity | Providing services with no difference based on personal characteristics | Chart Review | Every 6 months during WE CARE phase |

Practice |

| Parent Questionnaire | Index visit, 3-month follow-up | Parent | ||

| Patient-centeredness | Providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values, and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions | Parent Questionnaire | Index visit, 3-month follow-up | Parent |

| Satisfaction | Clients satisfied with the intervention | Parent Questionnaire | Index visit, 3-month follow-up | Parent |

At the practice level, we assess implementation outcomes during the WE CARE phase. We conduct check-ins (via telephone, videoconference or email) with the champion(s) at each practice approximately every 3 months during the WE CARE phase. These quarterly check-ins use a series of yes/no questions and open-ended prompts to assess champions’ attitudes about adopting WE CARE, the feasibility of implementing it within their practice, their perception of the fidelity with which it has been implemented, and the sustainability of the intervention. During a 90-day period within the first six months of implementing WE CARE, practices collect a copy of every WE CARE Screener distributed as well as the total number of visits eligible to receive a WE CARE Screener (i.e., well-child visits with children aged 2 months to 10 years), enabling us to assess early fidelity and penetration of WE CARE. Lastly, every 6 months during the WE CARE phase, practices perform a chart review to assess the proportion of visits at which WE CARE Screeners are administered and appropriate referrals are offered, contributing to our assessment of fidelity, penetration, and sustainability. “Appropriate” referrals are those that correspond to the domains for which parents indicated having a need and desiring assistance. In addition to documenting WE CARE Screeners and referrals, the chart review includes collection of children’s sociodemographic characteristics (including race, ethnicity, type of health insurance, language spoken at home, and child sex), allowing us to evaluate the equity with which the intervention is implemented.

We utilize a series of surveys and qualitative interviews to assess clinician/staff-level outcomes during the Core Training, Pilot, and WE CARE phases. First, we administer a pre-training survey composed of questions from the AAP’s Periodic Survey 90,28 and the Evidence Based Practice Attitudes Scale (EBPAS)29 to all practice clinicians in order to assess baseline attitudes about adoption and feasibility of addressing adverse SDOH in clinical practice. Following the training, we invite clinicians/staff to complete a quantitative survey containing the Texas Christian University Workshop Evaluation (TCU WEVAL)30 to measure attitudes about the appropriateness of implementing WE CARE within their unique practice setting. After clinicians/staff pilot WE CARE for 1-2 months, we invite them to complete a survey containing questions from the Periodic Survey 90 and EBPAS in order to assess the acceptability, adoption, appropriateness and feasibility of WE CARE. Survey respondents may additionally opt-in to participate in ~30-minute semi-structured in-depth interviews to discuss acceptability, adoption, appropriateness and feasibility of implementing WE CARE in their practice. After implementing WE CARE for 12 months, we send clinicians/staff a final survey including Periodic Survey 90 and EBPAS questions as well as a qualitative interview invitation, enabling us to further evaluate their perceptions regarding the appropriateness of WE CARE, the feasibility and fidelity with which WE CARE is implemented, and the sustainability of WE CARE at their practice.

At the parent level, we administer baseline and 3-month follow-up questionnaires to Usual Care and WE CARE phase participants. The surveys ask parents if they received a resource referral at their child’s visit and ask about services and resources that parents currently receive, regardless of whether receipt of resource referrals was mediated by WE CARE. We assess the effectiveness of WE CARE by comparing the odds of engagement with a new resource from baseline to follow-up in the Usual Care phase vs. the WE CARE phase. We also use the questionnaires to assess patient sociodemographic characteristics as well as the patient-centeredness of, and parents’ satisfaction with, their child’s medical care using instruments validated to assess these constructs.31

Data Analysis:

Data analysis is focused on three outcomes: 1) comparison of differences in resource referrals by implementation strategy to assess non-inferiority of pre-recorded vs. live webinar training, 2) effectiveness of WE CARE on increasing parent engagement with resources, and 3) WE CARE intervention sustainability.

To compare the difference in resource referrals provided at practices using the pre-recorded vs. live implementation strategies, we will use generalized mixed effect models controlling for practice, clinician/staff, and family-level sociodemographic characteristics. We will use adjusted odds ratios to express the effect size and differences in proportions.

Second, to investigate the effectiveness of WE CARE on increasing parent engagement with resources, we will utilize intention-to-treat analysis whereby outcomes of WE CARE phase participants are compared to those of Usual Care phase participants. Generalized mixed effects models will adjust for sociodemographic characteristics, baseline adverse SDOH, time (given the impact of seasonality on families’ unmet needs), and potentially important practice, clinician/staff, and family level characteristics. Effect sizes are compared across practices and implementation strategies in order to assess heterogeneity of WE CARE’s effect.

Third, to examine sustainability of WE CARE, we will use both quantitative and qualitative methods. Chart review data will be analyzed using mixed-model regression, adjusting for practice- and family-level sociodemographic characteristics and modeling for time. Qualitative interviews will be analyzed deductively using a codebook grounded in the Proctor Conceptual Model of Implementation Research and inductively to allow additional themes to emerge.

Sample Size and Power Calculation:

Because we are using a cluster randomization design, a larger sample size is required to compensate for clustering within sites. Our sample size calculations account for intra-class correlation (ICC) among the 18 sites for the various outcomes. We also account for within-subject correlation using an auto-regression structure. For certain outcomes (e.g., referrals), we can have different numbers of measurements at different time points. Consequently, we selected the number of observation time points that maximizes power. We powered the study to detect main effects using an intent-to-treat analysis and assuming a two-sided alpha of 0.05. Thus, for the effectiveness evaluation, we aim to recruit 70 families during the Usual Care phase and 70 families during the WE CARE phase at each of the 18 pediatric practices. We conservatively estimate a 40% loss-to-follow-up rate, consistent with similar research studies conducted with pediatric practice-based research networks.

We consider a 10% difference in clinician referrals between practices randomized to the pre-recorded vs. live implementation strategy to be clinically significant based on the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s clinical significance criteria for medical home interventions. Assuming an adjusted ICC of 0.01, we have 80% power to demonstrate the difference in implementation strategies. Successful implementation involves the distribution of WE CARE Screeners at >80% of eligible visits, and equivalent (within 10%) rates of screener distribution, clinician referral, and clinician/staff scores of acceptability and appropriateness (as measured through surveys and interviews).

Consistent with Garg et al.’s prior WE CARE efficacy study results,13 we set the clinically significant difference in odds of parent engagement with resources to be 15%. This, combined with our anticipated adjusted ICC of 0.01, allows for 90% power to detect a 12% difference in family engagement with resources.

To assess the sustainability of WE CARE, we estimate that, within pediatric practices, there will be no more than a 5% difference in quantitative implementation metrics assessed at six-month intervals. These quantitative metrics include the percentage of the eligible patient population who are offered a WE CARE Screener and percentage of resource referrals received among families who requested help. A priori, we define WE CARE as sustainable if WE CARE Screeners are distributed at >80% of visits and appropriate provider referrals are made for >90% of parent requests for assistance with adverse SDOH.

Ethics:

Boston Medical Center serves as the coordinating center for this trial, thus, initial ethics approval was obtained from the Boston Medical Center and Boston University Medical Campus Institutional Review Board (IRB). Additionally, PROS obtained organizational IRB approval from the AAP IRB, which covers each of the twelve study sites recruited through the PROS Network. Each of the six CORNET practices obtained approval from their institutional IRBs, blinded for confidentiality of practice’s participation. This trial is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02918435).

Trial Status:

Currently, we have completed enrolling all study sites, though accrual of parent and clinician/staff participants is still underway. The intervention period (WE CARE phase) has begun for all 18 study sites.

DISCUSSION

Guided by the Proctor Conceptual Model of Implementation Research, this hybrid type 2 effectiveness-implementation trial builds upon existing evidence of WE CARE’s effectiveness by assessing its implementation across a range of diverse pediatric practices in the US. This enables us to compare two distinct implementation strategies. Through our primary aim, we hypothesize the non-inferiority of a self-directed, pre-recorded webinar implementation strategy compared to study-team facilitated, live webinar training sessions, allowing for broad and faster dissemination of evidence-based SDOH screening and referral models into pediatric practices.

This study relies on pediatric clinicians and staff to implement WE CARE and conduct study recruitment while guided by external facilitators including a coordinating center and practice-based research network staff. This allows for participation and evaluation of an array of practices (from single-physician private practices to practices where pediatric residents serve as primary care providers in addition to faculty) with different levels of research staff support (some sites have dedicated research personnel built into their departments). We expect that these factors will differentially impact the engagement of clinician/staff stakeholders with this study and with implementing the intervention; we intend to study these factors and how they influence engagement and implementation outcomes.

Limitations of this study include the temporal context; notably, the COVID-19 pandemic began partway through practice recruitment. This necessitated adaptation of study procedures, such as the higher-touch implementation strategy shifting from a facilitated, in-person session to a live webinar conducted via videoconference. On the other hand, the live webinar may be a more cost-effective and therefore sustainable implementation model. It is also important to note that no implementation at practices began prior to the pandemic and therefore our WE CARE phase practices and participants are comparable. Additionally, the burden of COVID-19 on pediatric practices may have caused significant staff turnover and burnout, and may have discouraged some practices from participating or continuing to participate in the study. Furthermore, some participating sites suspended well-child care visits and/or transitioned well-child care visits to telemedicine for a portion of the study period; this delayed study activities, as the WE CARE intervention is designed to be implemented in person rather than via virtual visits.

Despite these limitations, this large, pragmatic trial may yield meaningful results including an evidence-based screening and referral system that could be readily implemented in a variety of pediatric practices, and may increase families’ engagement with resources to address their adverse SDOH.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Publication of this article was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), grant number R01HD090191. Additional infrastructure funding was provided by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under UA6MC15585 - National Research Network to Improve Children’s Health and U5DMC39344 - Pediatric Research Network Program. The contents in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement by, the NICHD, HRSA/HHS, or the US Government.

The authors thank all practices, pediatricians, nurse practitioners, other clinicians, staff, caregivers, and families who participated in the WE CARE Study.

Funding:

Funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), grant number R01HD090191. Additional infrastructure funding was provided by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under UA6MC15585 - National Research Network to Improve Children’s Health and U5DMC39344 - Pediatric Research Network Program.

ABBREVIATIONS

- SDOH

Social determinants of health

- US

United States

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- WE CARE

Well child care visit, Evaluation, Community resources, Advocacy, Referral, Education

- AAP

American Academy of Pediatrics

- PROS

Pediatric Research in Office Settings

- APA

Academic Pediatric Association

- CORNET

Continuity Research Network

- EBPAS

Evidence Based Practice Attitudes Scale

- TCU WEVAL

Texas Christian University Workshop Evaluation

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Though some study participants were other legal guardians (such as grandparents, aunts/uncles, or godparents), the majority of study participants were parents of pediatric patients; for brevity, we refer to these study participants as “parents” throughout.

This trial has been registered on ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02918435

CRediT author statement

Annelise Brochier: Writing - Original Draft, Visualization, Project administration; Alessandra Torres: Writing - Original Draft, Visualization, Project administration; Hollyce Tyrrell: Writing - Review & Editing, Project administration; Katherine Barahona Paz: Writing - Review & Editing; Mikayla Gordon Wexler: Writing - Review & Editing; Miranda Griffith: Writing - Review & Editing; Terence Joiner: Writing - Review & Editing; Angela Magardino: Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization; Emily Messmer: Writing - Review & Editing; Stephen Rogers: Writing - Review & Editing; Benjamin Scheindlin: Writing - Review & Editing; Janet R. Serwint: Methodology, Supervision, Project administration, Writing - Review & Editing; Iman Sharif: Methodology, Supervision, Project administration, Writing - Review & Editing; Laura P. Shone: Methodology, Supervision, Project administration, Writing - Review & Editing; Melissa S. Stockwell: Methodology, Supervision, Project administration, Writing - Review & Editing; Yorghos Tripodis: Methodology, Writing - Review & Editing; Arvin Garg: Methodology, Supervision, Project administration, Writing - Original Draft; Mari-Lynn Drainoni: Methodology, Supervision, Project administration, Writing - Original Draft

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health: debates, policy & practice, case studies; 2010. Accessed July 30, 2020. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44489/1/9789241500852_eng.pdf

- 2.Shonkoff JP, Phillips DA, eds. From Neurons to Neighborhoods. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans GW, Brooks-Gunn J, Klebanov PK. Stressing out the poor: chronic physiological stress and the income-achievement gap. Community Investments. 2011;23:22–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.02008.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halfon N, Hochstein M. Life course health development: an integrated framework for developing health, policy, and research. Milbank Quarterly. 2002;80(3):433–479, iii. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ben-Shlomo Y, Kuh D. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;31(2):285–293 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garg A, Brochier A, Messmer E, Fiori KP. Clinical approaches to reducing material hardship due to poverty: social risks/needs identification and interventions. Academic Pediatrics. 2021;21(8S):S154–S160. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2021.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keisler-Stakey K, Bunch LN. Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2021. U.S. Census Bureau: Current Population Reports, P60-278. U.S. Government Publishing Office; Washington, DC; September 2022. Accessed March 28, 2023. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2022/demo/p60-278.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8.QuickStats: Percentage of Children Aged <18 Years Who Received a Well-Child Checkup in the Past 12 Months, by Age Group and Year -- National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2008 and 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:222. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6908a5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mendelsohn AL, Huberman HS, Berkule SB, Brockmeyer CA, Morrow LM, Dreyer BP. Primary care strategies for promoting parent-child interactions and school readiness in at-risk families: the Bellevue Project for Early Language, Literacy, and Education Success. The Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2011;165(1):33–41. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.AAP Council on Community Pediatrics. Poverty and Child Health in the United States. Pediatrics. 2016;137(4):e20160339–e20160339. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung EK, Siegel BS, Garg A, et al. Screening for social determinants of health among children and families living in poverty: a guide for clinicians. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care. 2016;46(5):135–153. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2016.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Care Services; Committee on Integrating Social Needs Care into the Delivery of Health Care to Improve the Nation's Health. Integrating social care into the delivery of health care: moving upstream to improve the nation’s health. National Academies Press; 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garg A, Toy S, Tripodis Y, Silverstein M, Freeman E. Addressing social determinants of health at well child care visits: a cluster RCT. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2):e296–e304. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Proctor EK, Landsverk J, Aarons G, Chambers D, Glisson C, Mittman B. Implementation research in mental health services: an emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Administration and Policy in Mental Health Mental Health Services Research. 2009;36(1):24–34. doi: 10.1007/s10488-008-0197-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Medical Care. 2012;50(3):217–217. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arevian AC, O’Hora J, Rosser J, Mango JD, Miklowitz DJ, Wells KB. Patient and provider cocreation of mobile texting apps to support behavioral health: usability study. JMIR MHealth and UHealth. 2020;8(7):e12655. doi: 10.2196/12655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jellinek M, Patel BP, Froehle MC, eds. 2002. Bright Futures in Practice: Mental Health - Volume II. Tool Kit. Arlington, VA: National Center for Education in Maternal and Child Health [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garg A, Butz AM, Dworkin PH, Lewis RA, Thompson RE, Serwint JR. Improving the management of family psychosocial problems at low-income children's well-child care visits: the WE CARE Project. Pediatrics. 2007;120(3):547–558. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Melhuish E, Ereky-Stevens K, Petrogiannis K, Ariescu A, Penderi E, Rentzou K, Tawell A, Slot P, Broekhuizen M, Leserman P. A review of research on the effects of Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) on child development. Curriculum Quality Analysis and Impact Review of European Early Childhood Education and Care, CARE - European Early Childhood Education and Care; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas MMC, Miller DP, Morrissey TW. Food insecurity and child health. Pediatrics. 2019;144(4):e20190397. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leventhal T, Newman S. Housing and child development. Child and Youth Services Review. 2010;32(9):1165–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.03.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bradley RH, Corwyn RF. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;53:371–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cook JT, Frank DA, Casey PH, et al. A brief indicator of household energy security: associations with food security, child health, and child development in US infants and toddlers. Pediatrics. 2008;122(4):e867–875. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hussain N, Sprague S, Madden K, Hussain FN, Pindiprolu B, Bhandari M. A comparison of the types of screening tool administration methods used for the detection of intimate partner violence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2015;16(1):60–69. doi: 10.1177/1524838013515759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bradford S, Rickwood D. Psychosocial assessments for young people: a systematic review examining acceptability, disclosure and engagement, and predictive utility. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2012. Dec 21;3:111–25. doi: 10.2147/AHMT.S38442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garg A, LeBlanc A, Raphael JL. Inadequacy of current screening measures for health-related social needs. JAMA. 2023;330(10):915–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alderwick H, Gottlieb LM. Meanings and misunderstandings: a social determinant of health lexicon for health care systems: Milbank. 2019;97(2):407–419. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garg A, Cull W, Olson L, et al. Screening and referral for low-income families’ social determinants of health by US pediatricians. Academic Pediatrics. 2019;19(8):875–883. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2019.05.125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aarons GA. Mental health provider attitudes toward adoption of evidence-based practice: the Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS). Mental Health Services Research. 2004;6(2):61–74. doi: 10.1023/b:mhsr.0000024351.12294.65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simpson DD. A conceptual framework for transferring research to practice. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;22(4):171–182. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00231-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. The National Survey of Children's Health. Vol 2020. Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health supported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.