Abstract

Hyperkalemia is a common adverse event in patients with CKD and type 2 diabetes and limits the use of guideline-recommended therapies such as renin-angiotensin system inhibitors. We evaluated the comparative effects of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT-2i), glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RA) and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP-4i) on the risk of hyperkalemia. We conducted a population-based active-comparator, new-user cohort study using claims data from Medicare and 2 large U.S. commercial insurance databases (April 2013-April 2022). People with CKD stages 3-4 and type 2 diabetes who newly initiated SGLT-2i vs. DPP-4i (N=141671), GLP-1RA vs. DPP-4i (N=159545) and SGLT-2i vs. GLP-1RA (N=93033) were included. The primary outcome was hyperkalemia diagnosis in inpatient or outpatient setting. Secondary outcomes included hyperkalemia diagnosis in inpatient or emergency department setting, and serum potassium levels ≥5.5 mmol/L. Pooled hazard ratios (HRs) and rate differences (RDs)/1000 person-years were estimated after propensity score matching to adjust for >140 potential confounders.

Initiation of SGLT-2i was associated with a lower risk of hyperkalemia compared with DPP-4i (hazard ratio [HR] 0.74; 95%CI 0.68-0.80) and compared with GLP-1RA (HR 0.92; 0.86-0.99). Compared with DPP-4i, GLP-1RA were also associated with a lower risk of hyperkalemia (HR: 0.80; 0.75-0.86). Corresponding absolute RDs/1000 person-years were −24.8 (95%CI −31.8 to −17.7), −5.0 (−10.9 to 0.8), and −17.7 (−23.4 to −12.1), respectively. Similar findings were observed for the secondary outcomes, among subgroups, and across single agents within the SGLT-2i and GLP-1RA classes.

In conclusion, SGLT-2i and GLP-1RA are associated with a lower risk of hyperkalemia than DPP-4i in patients with CKD and type 2 diabetes, further supporting the use of these drugs in this population.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, type 2 diabetes, hyperkalemia, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors

Lay summary

Hyperkalemia means that the potassium in the blood is too high. It commonly occurs in people who have type 2 diabetes and kidney disease. Hyperkalemia often leads doctors to stop medications that protect the kidney, such as ACE inhibitors, because these medications also increase potassium levels in the blood. It is therefore important to find treatments that can prevent hyperkalemia. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT-2i), glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RA) and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP-4i) are commonly used medications to lower blood sugar in patients with type 2 diabetes. We were interested in investigating whether these medications could prevent hyperkalemia. In this study, we found that people with type 2 diabetes and kidney disease who used SGLT-2i and GLP-1RA had a lower risk of developing hyperkalemia than people who started DPP-4i. Our study therefore supports the use of these medications in people with type 2 diabetes and kidney disease.

Introduction

Hyperkalemia is a common problem among people with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and type 2 diabetes (T2D)1. Lower kidney function and T2D are independent risk factors for developing hyperkalemia2,3. Furthermore, various common medication classes that are used to improve clinical outcomes in these patients, such as renin-angiotensin system inhibitors (RASi)4 and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA), increase the risk of hyperkalemia5-9. In addition to the risk of life-threatening arrhythmias, the occurrence of hyperkalemia negatively affects clinical outcomes in patients with CKD and T2D due to the necessity of discontinuing or reducing the dose of guideline-recommended medications, such as RASi10,11.

In recent years, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT-2i), glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RA) and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP-4i) have become common drugs for treating T2D12,13 in clinical practice, with the former two drug classes showing cardiovascular and kidney benefits14-16. Moreover, SGLT-2i have been shown to reduce the risk of hyperkalemia compared with placebo in randomized trials17,18. However, several key knowledge gaps remain: first, it is unknown whether the beneficial effects of SGLT-2i for reducing hyperkalemia that were observed in highly controlled trial conditions are similarly observed in real-world settings. Second, head-to-head comparisons between SGLT-2i, GLP-1RA and DPP-4i are currently lacking. Lastly, there are small-scale randomized trials that suggest GLP-1RA influence tubular handling of electrolytes and increase potassium excretion19,20, though it is unknown whether this increase in potassium excretion also leads to a reduced risk of hyperkalemia in clinical settings.

The aim of this study was therefore to investigate the comparative effectiveness of SGLT-2i, GLP-1RA and DPP-4i in lowering the risk of hyperkalemia among patients with CKD and T2D in a real-world setting.

Methods

Data source

We used data from three large U.S. administrative claims databases: Optum’s de-identified Clinformatics® Data Mart Database (CDM), IBM® MarketScan®, and Medicare fee-for-service Parts A, B and D. CDM and IBM® MarketScan® include a national commercially insured U.S. population. Medicare is a federal health insurance program providing healthcare coverage for U.S. residents aged ≥65 years or <65 years with disabilities. All databases contain de-identified longitudinal information including patient demographics, healthcare use, inpatient and outpatient medical diagnoses and procedures, outpatient laboratory results (~45% of patients in CDM and 5-10% in IBM® MarketScan®), and prescription dispensing records. The study was approved by the Mass General Brigham Institutional Review Board with waiver of informed consent and signed data license agreements were in place for all data sources.

Study design and study population

We constructed three active-comparator, new-user cohorts21-23 of patients who newly initiated SGLT-2i vs. DPP-4i (cohort 1), GLP-1RA vs. DPP-4i (cohort 2) and SGLT-2i vs. GLP-1RA (cohort 3) between April 2013 and the end of available data (April 2022 in CDM, December 2020 in IBM® MarketScan® and December 2019 in Medicare) (Supplementary Figure S1). New initiation was defined as a filled prescription for one of the two drug classes in each pairwise comparison, with no dispensing of either drug in the previous 365 days. Eligible patients were required to be ≥18 years (≥65 years for Medicare), have at least 12 months of continuous insurance enrollment prior to drug initiation, as well as diagnoses for CKD and T2D. We defined CKD as at least one inpatient or 2 outpatient diagnosis codes for CKD stages 3-424 (Supplementary Table S1). This definition was based on a previously validated algorithm which showed sufficient accuracy to identify a CKD population (positive predictive value >80%)25. Exclusion criteria were a history of type 1 diabetes, secondary or gestational diabetes, CKD stage 5/end-stage kidney disease, nursing home admission, organ transplant, pancreatitis, cirrhosis, acute hepatitis, or multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (Supplementary Table S1). Furthermore, we excluded individuals who had a hyperkalemia diagnosis or used potassium binders in the 90 days preceding cohort entry to decrease the possibility that early outcomes during follow-up would be related to a previous hyperkalemia diagnosis (i.e., reverse causation bias), or that the drugs under comparison were started differentially based on history of hyperkalemia (i.e., confounding).

Treatment strategies and follow-up

Our treatment strategies of interest were initiation of SGLT-2i, GLP-1RA or DPP-4i. Follow-up began on the day after cohort entry and continued in an “as-treated” approach until treatment discontinuation or switch to a drug in the comparator class, outcome occurrence, death, end of continuous health plan enrollment, or end of available data, whichever occurred first. Discontinuation was defined as no prescription refill for the index exposure within the 30 days after the most recent prescription had ended, based on days’ supply. We chose an as-treated follow-up approach as our primary analysis to address the high rate of treatment discontinuation in routine care26 and reduce exposure misclassification22.

Study outcomes

The primary outcome was a diagnosis code for hyperkalemia in the inpatient or outpatient setting (definitions provided in Supplementary Table S2). Secondary outcomes included a hyperkalemia diagnosis in the inpatient or emergency department setting, and a composite of serum potassium level ≥5.5 mmol/L in the outpatient setting or hyperkalemia diagnosis in the inpatient setting. The latter outcome was only assessed in CDM among the individuals who had at least one serum potassium measured in the 365 days before cohort entry, as IBM® MarketScan® and Medicare contain few or no laboratory measurements.

We also performed an internal validation study in CDM to test the specificity and sensitivity of the claims-based hyperkalemia definitions. We included all adult individuals who had a serum potassium measurement (LOINC codes 6298-4, 77142-8, 12812-4, 12813-2, 42569-4) and assessed whether there was a hyperkalemia diagnosis in the 90-day window after the serum potassium measurement. Among 12.3 million individuals, we found a specificity of 99.5% and sensitivity of 22.3% for the primary outcome definition when serum potassium ≥5.5 mmol/L was used to define hyperkalemia, and specificity of 99.3% and sensitivity of 37.1% when serum potassium ≥6.0 mmol/L was used to define hyperkalemia. Since specificity is high and misclassification is likely nondifferential, even when sensitivity is low, the relative risk estimates will be unbiased27. However, when sensitivity is low, absolute rate differences will be biased toward the null. Hence, the observed associations on the absolute scale for the primary outcome will represent an underestimate of the true absolute rate difference.

Covariates

Patient baseline characteristics were measured during the 365 days before cohort entry date. Based on subject matter knowledge and previous studies evaluating outcomes of medication use in people with CKD and T2D28, we chose covariates that were associated with the outcome or were confounders or confounder proxies. Ascertainment of comorbid conditions was based on ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis and procedure codes, and ascertainment of drug use was based on generic drug names, in the 365 days prior to and including the cohort entry date. Covariates of interest included: (1) demographics, including age, sex and race (race was only available in CDM and Medicare); (2) comorbid conditions; (3) diabetes-specific complications; (4) use of cardiovascular and diabetes drugs; (5) use of other comedications; (6) measures of healthcare use, including number of hospitalizations, emergency department visits, cardiologist and nephrologist visits and number of laboratory tests; (7) healthy behavior markers, including vaccinations and screening; and (8) calendar year. To address potential confounding by frailty, we also used a claims-based frailty index29. Race was self-reported in the claims data sources. There were no missing data for the other covariates, as the absence of a diagnosis or procedure code was interpreted as the absence of a particular condition.

Statistical analysis

To adjust for baseline confounders we used 1:1 propensity score matching using the nearest neighbor method and a caliper of 0.01 of the propensity score30. We estimated the probability of receiving SGLT-2i vs. DPP-4i (cohort 1), GLP-1RA vs. DPP-4i (cohort 2) and SGLT-2i vs. GLP-1RA (cohort 3) as a function of >140 pre-exposure covariates using multivariable logistic regression. We included all covariates from Supplementary Table S3 in the propensity score model, except for laboratory results which were only available in a subset of patients (~22% of overall population). Covariate balance before and after matching was assessed using standardized mean differences (SMD)31,32. We also assessed balance in laboratory results to assess potential residual confounding by unmeasured factors, since these were not included in the propensity score. For each outcome, we calculated numbers of events, incidence rates, incidence rate differences and hazard ratios (HRs) in the propensity score-matched cohorts. The HRs and incidence rate differences with their 95%CIs were estimated in each data source and then pooled using a fixed effects meta-analysis. HRs were estimated using Cox regression, and incidence rate differences using generalized linear regression with identity link function and normal error distribution33. We constructed survival plots with the Aalen-Johansen estimator, which does not overestimate risks in the presence of the competing risk of death34. Analyses were performed using R version 3.6.2 and the Aetion Evidence Platform v4.5335.

Subgroup analyses and effectiveness of individual agents

We performed subgroup analyses in the following prespecified subgroups: age (< vs. ≥75 years), sex, race (White vs. Black), baseline cardiovascular disease, heart failure, use of RASi, MRA and loop diuretics (definitions for cardiovascular disease and heart failure are provided in Supplemental Table S3). Subgroup analyses according to race was only performed in Medicare. Cardiovascular disease was defined as a composite of myocardial infarction, stable angina, acute coronary syndrome, coronary atherosclerosis, history of coronary procedure, heart failure, ischemic stroke and peripheral vascular disease. For subgroup analyses, propensity score estimation and matching were reperformed for each subgroup. In secondary analyses, to investigate potential differences between agents within the SGLT-2i and GLP-1RA class, we assessed the associations between empagliflozin, canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, liraglutide, dulaglutide, exenatide and semaglutide versus DPP-4i.

Sensitivity analyses

We performed the following sensitivity analyses: first, we defined treatment discontinuation as no prescription refill within 60 days (instead of 30 days); second, to investigate the influence of informative censoring, we applied an intention-to-treat follow-up approach, where follow-up was continued for a maximum of 180 and 365 days regardless of treatment discontinuation or switch; third, we excluded all patients who had a history of hyperkalemia or potassium binder use in the prior 365 days, and used a broad outcome defined as hyperkalemia diagnosis in the inpatient or outpatient setting or initiation of potassium binders during follow-up.

Results

Baseline characteristics of study populations

Flowcharts for study inclusion are shown in Supplementary Figure S2. After 1:1 propensity score matching, the SGLT-2i vs. DPP-4i cohort included 21196 propensity score matched pairs, the GLP-1RA vs. DPP-4i cohort included 33402 pairs, and the SGLT-2i vs. GLP-1RA cohort included 27997 propensity score matched pairs. After matching, baseline characteristics in the three cohorts were well balanced, with SMD<0.10 (Table 1, Supplementary Tables S4-S6). In the SGLT-2i vs. DPP-4i cohort, mean age was 72 years, 56% were male, 90% had CKD stage 3, 59% had cardiovascular disease, and 26% heart failure. Among those with available laboratory measurements (22% of the overall population), mean eGFR was 43 ml/min/1.73m2 and mean serum potassium was 4.5 mmol/L. Furthermore, 81% used ACEi or ARB, 10% MRA, 35% loop diuretics and 36% used insulin during the baseline period. Baseline characteristics were similar across the three cohorts, although insulin use was higher for the GLP-1RA vs. DPP-4i cohort (46% vs. 34-36%). In the SGLT-2i vs. DPP-4i cohort, the most commonly used SGLT-2i were empagliflozin (52.5%), followed by canagliflozin (32.9%) and dapagliflozin (14.4%). In the GLP-1RA vs. DPP-4i cohort, the most commonly used GLP-1RA were liraglutide (38.5%), dulaglutide (36.0%), exenatide (13.1%) and semaglutide (10.3%) (Supplementary Table S7).

Table 1.

Selected baseline characteristics of patients with chronic kidney disease and type 2 diabetes initiating SGLT-2i vs. DPP-4i, GLP-1RA vs. DPP-4i and SGLT-2i vs. GLP1-1RA after 1:1 propensity score matching.

| SGLT-2i vs. DPP-4i | GLP-1RA vs. DPP-4i | SGLT-2i vs. GLP-1RA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGLT-2i | DPP-4i | GLP-1RA | DPP-4i | SGLT-2i | GLP-1RA | |

| Total | 21196 | 21196 | 33402 | 33402 | 27997 | 27997 |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age, years; mean (sd) | 72.2 (7.4) | 72.2 (7.4) | 71.8 (7.1) | 71.7 (7.1) | 72.3 (7.4) | 72.3 (7.4) |

| Male; n (%) | 11918 (56.2%) | 11832 (55.8%) | 16607 (49.7%) | 16634 (49.8%) | 15466 (55.2%) | 15496 (55.3%) |

| Race/ethnicity*; n (%) | ||||||

| White | 13804 (65.1%) | 13810 (65.2%) | 22228 (66.5%) | 22305 (66.8%) | 17917 (64.0%) | 17915 (64.0%) |

| Black | 2179 (10.3%) | 2152 (10.2%) | 3672 (11.0%) | 3630 (10.9%) | 2846 (10.2%) | 2822 (10.1%) |

| Other | 3030 (14.3%) | 3051 (14.4%) | 4036 (12.1%) | 4001 (12.0%) | 4157 (14.8%) | 4183 (14.9%) |

| Burden of comorbidities | ||||||

| Combined comorbidity score; mean (sd) | 4.1 (2.5) | 4.1 (2.4) | 4.1 (2.4) | 4.1 (2.4) | 4.0 (2.4) | 4.0 (2.4) |

| Frailty score; mean (sd) | 0.21 (0.06) | 0.21 (0.06) | 0.21 (0.06) | 0.21 (0.06) | 0.20 (0.06) | 0.21 (0.06) |

| Comorbidities; n (%) | ||||||

| CKD Stage 3 | 19064 (89.9%) | 19031 (89.8%) | 28113 (84.2%) | 28060 (84.0%) | 25011 (89.3%) | 24946 (89.1%) |

| CKD Stage 4 | 2132 (10.1%) | 2165 (10.2%) | 5289 (15.8%) | 5342 (16.0%) | 2986 (10.7%) | 3051 (10.9%) |

| Hyperkalemia | 1138 (5.4%) | 1130 (5.3%) | 1989 (6.0%) | 1965 (5.9%) | 1571 (5.6%) | 1614 (5.8%) |

| Hypokalemia | 1054 (5.0%) | 1081 (5.1%) | 1803 (5.4%) | 1750 (5.2%) | 1329 (4.7%) | 1367 (4.9%) |

| Acute Kidney Injury | 3536 (16.7%) | 3554 (16.8%) | 6247 (18.7%) | 6187 (18.5%) | 4528 (16.2%) | 4535 (16.2%) |

| Hypertension | 20413 (96.3%) | 20397 (96.2%) | 32229 (96.5%) | 32224 (96.5%) | 26949 (96.3%) | 26959 (96.3%) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 18845 (88.9%) | 18835 (88.9%) | 29606 (88.6%) | 29538 (88.4%) | 24931 (89.0%) | 24924 (89.0%) |

| Cardiovascular disease§ | 12588 (59.4%) | 12497 (59.0%) | 19184 (57.4%) | 19310 (57.8%) | 16346 (58.4%) | 16216 (57.9%) |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 1008 (4.8%) | 997 (4.7%) | 1306 (3.9%) | 1280 (3.8%) | 1187 (4.2%) | 1187 (4.2%) |

| Heart failure | 5543 (26.2%) | 5589 (26.4%) | 8516 (25.5%) | 8421 (25.2%) | 6971 (24.9%) | 6931 (24.8%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 3960 (18.7%) | 3936 (18.6%) | 5891 (17.6%) | 5855 (17.5%) | 5006 (17.9%) | 4993 (17.8%) |

| Ischemic stroke | 3098 (14.6%) | 3070 (14.5%) | 4817 (14.4%) | 4856 (14.5%) | 4005 (14.3%) | 4004 (14.3%) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 3918 (18.5%) | 3890 (18.4%) | 6188 (18.5%) | 6194 (18.5%) | 5159 (18.4%) | 5188 (18.5%) |

| Diabetes-related conditions; n (%) | ||||||

| Diabetic nephropathy | 14493 (68.4%) | 14495 (68.4%) | 22821 (68.3%) | 22823 (68.3%) | 18975 (67.8%) | 18940 (67.7%) |

| Diabetic retinopathy | 3836 (18.1%) | 3773 (17.8%) | 6496 (19.4%) | 6559 (19.6%) | 5044 (18.0%) | 5033 (18.0%) |

| Diabetic neuropathy | 7631 (36.0%) | 7654 (36.1%) | 12694 (38.0%) | 12647 (37.9%) | 9995 (35.7%) | 9973 (35.6%) |

| Hypoglycemia | 3857 (18.2%) | 3871 (18.3%) | 6005 (18.0%) | 6022 (18.0%) | 4941 (17.6%) | 4988 (17.8%) |

| No. of distinct medications; mean (sd) | 15.4 (6.4) | 15.5 (6.5) | 15.7 (6.3) | 15.8 (6.5) | 15.6 (6.5) | 15.7 (6.4) |

| Diabetes medications on day of entry to cohort; n (%) | ||||||

| No. of diabetes drugs, mean (sd) | 2.20 (0.85) | 2.21 (0.83) | 2.15 (0.84) | 2.16 (0.84) | 2.44 (0.95) | 2.45 (0.96) |

| Metformin | 12365 (58.3%) | 12438 (58.7%) | 16144 (48.3%) | 16281 (48.7%) | 16013 (57.2%) | 16053 (57.3%) |

| Sulfonylureas | 9640 (45.5%) | 9760 (46.0%) | 14924 (44.7%) | 15180 (45.4%) | 13944 (49.8%) | 14003 (50.0%) |

| DPP-4i | - | - | - | - | 10902 (38.9%) | 10930 (39.0%) |

| SGLT-2i | - | - | 2619 (7.8%) | 2600 (7.8%) | - | - |

| GLP-1RA | 3452 (16.3%) | 3416 (16.1%) | - | - | - | - |

| Insulin | 7643 (36.1%) | 7770 (36.7%) | 15258 (45.7%) | 15149 (45.4%) | 9588 (34.2%) | 9568 (34.2%) |

| Other medication use; n (%) | ||||||

| ACEi or ARB | 17203 (81.2%) | 17201 (81.2%) | 26588 (79.6%) | 26572 (79.6%) | 22813 (81.5%) | 22864 (81.7%) |

| ARNI | 326 (1.5%) | 337 (1.6%) | 288 (0.9%) | 298 (0.9%) | 365 (1.3%) | 364 (1.3%) |

| Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists | 2080 (9.8%) | 2079 (9.8%) | 3215 (9.6%) | 3178 (9.5%) | 2605 (9.3%) | 2621 (9.4%) |

| Beta blockers | 12828 (60.5%) | 12874 (60.7%) | 20382 (61.0%) | 20386 (61.0%) | 16912 (60.4%) | 16868 (60.2%) |

| Calcium channel blockers | 9330 (44.0%) | 9245 (43.6%) | 15064 (45.1%) | 15051 (45.1%) | 12612 (45.0%) | 12649 (45.2%) |

| Loop diuretics | 7314 (34.5%) | 7285 (34.4%) | 12929 (38.7%) | 12865 (38.5%) | 9496 (33.9%) | 9545 (34.1%) |

| Statins | 17815 (84.0%) | 17738 (83.7%) | 27679 (82.9%) | 27649 (82.8%) | 23666 (84.5%) | 23537 (84.1%) |

| Antiplatelet agents | 3940 (18.6%) | 3988 (18.8%) | 5799 (17.4%) | 5863 (17.6%) | 5167 (18.5%) | 5160 (18.4%) |

| Anticoagulants | 3368 (15.9%) | 3294 (15.5%) | 5119 (15.3%) | 5117 (15.3%) | 4270 (15.3%) | 4272 (15.3%) |

| Potassium binders | 94 (0.4%) | 89 (0.4%) | 216 (0.6%) | 221 (0.7%) | 162 (0.6%) | 173 (0.6%) |

| Potassium supplements | 3133 (14.8%) | 3207 (15.1%) | 5129 (15.4%) | 5133 (15.4%) | 4040 (14.4%) | 3992 (14.3%) |

| Healthcare utilization markers | ||||||

| No. of hospitalizations; mean (sd) | 0.3 (0.78) | 0.3 (0.79) | 0.3 (0.8) | 0.3 (0.8) | 0.3 (0.8) | 0.3 (0.8) |

| No. of emergency room visits; mean (sd) | 0.8 (1.95) | 0.9 (1.82) | 0.9 (2.1) | 0.9 (1.9) | 0.8 (1.9) | 0.8 (2.0) |

| No. of internist visits; mean (sd) | 22.5 (27.85) | 22.7 (27.69) | 21.3 (25.9) | 21.3 (25.9) | 22.3 (27.4) | 22.4 (27.0) |

| No. of cardiologist visits; mean (sd) | 5.7 (10.8) | 5.6 (10.9) | 5.1 (9.7) | 5.1 (9.7) | 5.4 (10.1) | 5.4 (10.2) |

| No. of endocrinologist visits; mean (sd) | 1.9 (7.17) | 1.8 (6.81) | 2.1 (7.2) | 2.0 (7.0) | 1.7 (6.5) | 1.8 (6.7) |

| No. of nephrologist visits; mean (sd) | 1.9 (5.56) | 1.8 (5.24) | 2.3 (5.9) | 2.3 (5.8) | 1.9 (5.6) | 1.9 (5.6) |

| Potassium test order; n (%) | 928 (4.4%) | 944 (4.5%) | 1554 (4.7%) | 1572 (4.7%) | 1152 (4.1%) | 1210 (4.3%) |

| Lab measurements, mean (sd) | ||||||

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73m2 † | 45 (16) | 42 (15) | 42 (15) | 42 (15) | 45 (16) | 42 (15) |

| Serum potassium, mmol/L † | 4.5 (0.4) | 4.5 (0.5) | 4.5 (0.4) | 4.5 (0.5) | 4.5 (0.4) | 4.5 (0.4) |

ACEi = angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB = angiotensin II receptor blockers; ARNI = angiotensin-receptor neprilysin inhibitors; CKD = chronic kidney disease; DPP-4i = dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; GLP-1RA = glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist; HbA1c = hemoglobin A1c; n = number of patients; No. = number of; SGLT-2i = sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor; sd = standard deviation.

Pooled across CDM and Medicare databases only, and therefore does not add up to 100%

Cardiovascular disease was defined as a composite of myocardial infarction, stable angina, acute coronary syndrome, coronary atherosclerosis, history of coronary procedure, heart failure, ischemic stroke and peripheral vascular disease.

After propensity score matching, eGFR was available for 21.5% of participants in the SGLT-2i vs. DPP-4i cohort, 17.6% for the GLP-1RA vs. DPP-4i cohort, and 20.0% for SGLT-2i vs. GLP-RA cohort. Serum potassium was available 21.3%, 17.4% and 19.8%, respectively

Hyperkalemia risk associated with SGLT-2i, GLP-1RA, and DPP-4i

After propensity score matching, the mean follow-up for the primary outcome was 7.8 months in the SGLT-2i vs. DPP-4i cohort, 8.0 months in the GLP-1RA vs. DPP-4i cohort, and 7.6 months in the SGLT-2i vs. GLP-1RA cohort (Supplementary Table S8). Initiation of SGLT-2i was associated with a lower risk of hyperkalemia compared with DPP-4i, with an adjusted HR of 0.74 (95%CI 0.68-0.80) and incidence rate difference of −24.8 (95%CI −31.8 to −17.7) per 1000 person-years (Table 2). Furthermore, GLP-1RA were associated with a lower risk of hyperkalemia compared with DPP-4i, with an adjusted HR of 0.80 (95%CI 0.75-0.86) and incidence rate difference of −17.7 (−23.4 to −12.1) per 1000 person-years. The adjusted HR for SGLT-2i vs. GLP-1RA was 0.92 (95% CI 0.86-0.99), with an incidence rate difference of −5.0 (−10.9 to 0.8). The lower risk of hyperkalemia for SGLT-2i and GLP-1RA as compared with DPP-4i was observed within the first 6 months of follow-up (Figure 1). When comparing SGLT-2i vs. GLP-1RA, the cumulative incidence curves for hyperkalemia overlapped for the first 9 months of follow-up and started to diverge thereafter. Absolute risks and absolute risk differences at 6-month intervals are reported in Supplementary Table S9. At 2 years of follow-up, the absolute risk was 4.3% (95%CI 2.8%-5.7%) lower for SGLT-2i vs DPP-4i, and 2.3% (1.2%-3.5%) lower for GLP-1RA vs. DPP-4i.

Table 2.

Comparative effectiveness of (A) SGLT-2i versus DPP-4i, (B) GLP-1RA vs. DPP-4i and (C) SGLT-2i vs. GLP-1RA on risk of hyperkalemia diagnosis in inpatient or outpatient setting before and after 1:1 propensity score matching.

| A. SGLT-2i vs. DPP-4i | Before 1:1 propensity score matching | After 1:1 propensity score matching | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGLT-2i | DPP-4i | SGLT-2i | DPP-4i | |

| Sample size, n | 25257 | 116414 | 21196 | 21196 |

| Total events, n | 1160 | 9682 | 960 | 1441 |

| Follow-up, PY | 15085 | 92642 | 12758 | 14408 |

| Incidence rate/1000PY (95% CI) | 76.9 (72.5 to 81.5) | 104.5 (102.4 to 106.6) | 75.3 (70.6 to 80.2) | 100.0 (94.9 to 105.3) |

| Rate difference/1000PY (95% CI) | −27.6 (−32.5 to −22.7) | Ref | −24.8 (−31.8 to −17.7) | Ref |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | 0.69 (0.65 to 0.74) | Ref | 0.74 (0.68 to 0.80) | Ref |

| B. GLP-1RA vs. DPP-4i | Before 1:1 propensity score matching | After 1:1 propensity score matching | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLP-1RA | DPP-4i | GLP-1RA | DPP-4i | |

| Sample size, n | 44208 | 115337 | 33402 | 33402 |

| Total events, n | 2257 | 9507 | 1723 | 2401 |

| Follow-up, PY | 27195 | 91990 | 20763 | 23839 |

| Incidence rate/1000PY (95% CI) | 83.0 (79.6 to 86.5) | 103.3 (101.3 to 105.5) | 83.0 (79.1 to 87.0) | 100.7 (96.7 to 104.8) |

| Rate difference/1000PY (95% CI) | −20.5 (−24.4 to −16.4) | Ref | −17.7 (−23.4 to −12.1) | Ref |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | 0.76 (0.73 to 0.80) | Ref | 0.80 (0.75 to 0.86) | Ref |

| C. SGLT-2i vs. GLP-1RA | Before 1:1 propensity score matching | After 1:1 propensity score matching | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGLT-2i | GLP-1RA | SGLT-2i | GLP-1RA | |

| Sample size, n | 31708 | 61325 | 27997 | 27997 |

| Total events, n | 1480 | 3401 | 1300 | 1462 |

| Follow-up, PY | 19310 | 39918 | 17059 | 17994 |

| Incidence rate/1000PY (95% CI) | 76.6 (72.8 to 80.7) | 85.2 (82.4 to 88.1) | 76.2 (72.1 to 80.5) | 81.3 (77.1 to 85.5) |

| Rate difference/1000PY (95% CI) | −8.6 (−13.4 to −3.7) | Ref | −5.0 (−10.9 to 0.8) | Ref |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | 0.88 (0.83 to 0.94) | Ref | 0.92 (0.86 to 0.99) | Ref |

CI = confidence interval; DPP-4i = dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor; GLP-1RA = glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist; PY = person-years; Ref = reference; SGLT-2i = sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor.

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence curves for (A) SGLT-2i versus DPP-4i, (B) GLP-1RA vs. DPP-4i and (C) SGLT-2i vs. GLP-1RA on risk of hyperkalemia diagnosis in inpatient or outpatient setting after 1:1 propensity score matching.

When the outcome definition was changed to hyperkalemia diagnosis in the inpatient or emergency department setting, the results were consistent for SGLT-2i vs DPP-4i and GLP-1RA vs. DPP-4i comparisons, with HRs of 0.76 (95% CI 0.58-0.99) and 0.66 (0.54-0.80), respectively. Furthermore, the HR for SGLT-2i vs. GLP-1RA was 1.06 (0.82-1.38) (Supplementary Table S10). Similar findings were observed when using a lab-based outcome definition (serum potassium ≥5.5 mmol/L) in the subset of patients who had serum potassium measurements available in the CDM dataset, although confidence intervals were wide (Supplementary Table S11): hazard ratios were 0.88 (95%CI 0.69-1.13) for SGLT-2i vs. DPP-4i, 0.86 (0.69-1.06) for GLP-1RA vs. DPP-4i, and 1.14 (0.91-1.43) for SGLT-2i vs. GLP-1RA.

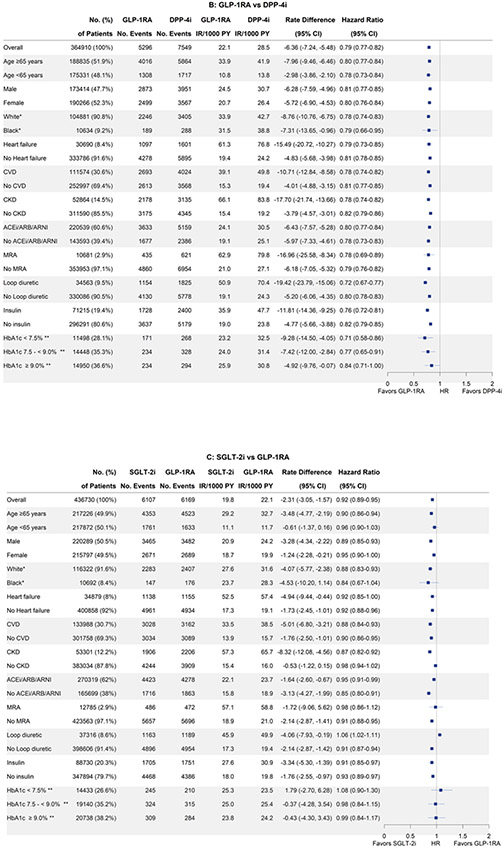

Subgroup analyses, effectiveness of individual agents and sensitivity analyses

Findings were consistent across all subgroups for all three cohorts (Figure 2), including in patients with history of heart failure and cardiovascular disease, as well as patients on medications that influence potassium levels, i.e., RASi, MRAs and loop diuretics. The lower risk of hyperkalemia was consistent among individual agents within the SGLT-2i class (hazard ratios between 0.72 and 0.77) and GLP-1RA classes (hazard ratios between 0.75 and 0.86) (Supplementary Table S12). Findings were also consistent among all sensitivity analyses (Supplementary Table S13).

Figure 2.

Comparative effectiveness of (A) SGLT-2i versus DPP-4i (B) GLP-1RA vs. DPP-4i and (C) SGLT-2i vs. GLP-1RA on risk of hyperkalemia diagnosis in inpatient or outpatient setting among subgroups after 1:1 propensity score matching.

ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB = angiotensin II receptor blockers; ARNI = angiotensin receptor/neprilysin inhibitor; CI = confidence interval; CVD = cardiovascular disease; DPP-4i = dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor; GLP-1RA = glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist; IR = Incidence Rate; MRA = mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists; PY = person-years; SGLT-2i = sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor.

*Only data from CMS Medicare

Discussion

In this large, nationwide U.S. cohort study of persons with CKD and T2D, we found that both SGLT-2i and GLP-1RA were associated with a lower risk of hyperkalemia compared with DPP-4i. Furthermore, we observed consistent findings across subgroups of demographics, comorbid conditions and medications known to influence potassium levels, and in multiple sensitivity analyses, as well as across individual agents within the SGLT-2i and GLP-1RA classes.

Our findings have important clinical implications. Hyperkalemia occurs frequently among patients with CKD and T2D, particularly those with low kidney function1. These patients are also at the highest risk for adverse cardiovascular and renal events. Our findings suggest that both SGLT-2i and GLP-1RA are associated with a lower risk of hyperkalemia. Initiating these medications may therefore enable patients to use other guideline-recommended therapies that are associated with an increased risk of hyperkalemia, such as inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (ACEi/ARB, MRA, ARNI). Indeed, hyperkalemia often leads to dose reduction or discontinuation of these therapies, which has been associated with worse clinical outcomes10,11.

Our study has several novel findings. A previous meta-analysis of six randomized trials found that SGLT-2i lowered the risk of hyperkalemia compared with placebo in people with T2D17. Our results extend the protective effects of SGLT-2i on hyperkalemia observed in controlled trial settings to the broad group of patients with CKD and T2D seen in routine clinical practice. There are several differences between the trials and our observational study worth highlighting. First, our study population was on average 10 years older, included a larger proportion of females, and larger proportion of patients with heart failure. Second, due to monitoring protocols, trials have a much higher adherence to drug therapy compared with routine clinical practice; in our population-based study, 61% of participants in routine care discontinued treatment during follow-up. Third, there are differences in the incidence rate of hyperkalemia between the previous meta-analysis of trials and our observational study, likely explained by population differences: among the six included trials, the incidence rate for hyperkalemia varied between 1.6 (DECLARE-TIMI trial) to 56.9 (DAPA-CKD trial) hyperkalemia events per 1000 person-years17. In contrast, the incidence rate for the primary outcome in our study was higher, between 75.3 and 100.0 hyperkalemia events per 1000 person-years. The difference in incidence rates is likely an underestimate, as the trial relied on serial serum potassium measurements, and our study used claims diagnoses; the findings from our internal validation study suggest that the true incidence rate in our study may be ~3 fold higher. Fourth, our study provides a head-to-head comparison of SGLT-2i, GLP-1RA and DPP-4i, rather than placebo. Although SGLT-2i initiators had a lower risk of hyperkalemia compared with DPP-4i, we found only small differences between SGLT-2i and GLP-1RA, and any differences between the latter two agents are likely to be small.

The protective association observed for GLP-1RA on the risk of hyperkalemia in a clinical setting has, to our knowledge, not been reported previously. There may be several plausible mechanisms for this finding, although additional research should elucidate the precise mechanisms for our observations. GLP-1RA regulate water and electrolyte balance in the postprandial state through rapid feed-forward effects on the kidney, and influence tubular handling of electrolytes, including sodium20. The increased proximal sodium excretion due to GLP-1RA may augment potassium secretion by the principal cells in the cortical collecting duct by increasing the electronegative charge36. Furthermore, a small randomized trial in 35 overweight participants with T2D showed that after 8 weeks of treatment, the GLP-1RA lixisenatide increased the fractional and absolute excretion of potassium itself19, although another study by the same group did not find differences in fractional potassium excretion for liraglutide compared with sitagliptin37. We observed that the protective effect of GLP-1RA occurred rapidly (within the first six months). In addition to these direct effects on electrolytes, GLP-1RA may also slow progression of kidney disease and albuminuria38-40, which may decrease the risk of hyperkalemia in the long-term.

Our study also had sufficient sample size to investigate single agents within the SGLT-2i and GLP-1RA class and enable us to assess whether the reduced risk of hyperkalemia was a class effect or only observed for specific agents. The consistency of hazard ratios (between 0.72 to 0.77 for single SGLT-2i agents and between 0.75 to 0.86 for single GLP-1RA agents) suggest that the protective associations of SGLT-2i and GLP-1RA on hyperkalemia represent a class effect.

Our study has several strengths, including its large sample size and the use of an active-comparator new user design, which reduces confounding by indication and mitigates time-related biases such as immortal and prevalent user bias. Furthermore, our analysis adjusted for a rich set of >140 confounders, and we confirmed our results in multiple sensitivity analyses. Our study also has limitations. First, we cannot rule out confounding in our observational study, and we lacked information on dietary habits (e.g., intake of high potassium containing foods). However, we adjusted for a wide variety of confounders and confounder proxies, including many comorbid conditions, medications, diabetes-specific complications, measures of healthcare use and healthy behavior markers which reflect overall health status22. Furthermore, in the subset of patients with available data, we did not observe large imbalances in laboratory measurements which were not included in the propensity score model, including eGFR and serum potassium. Confounding is also expected to be less severe for “unintended effects” or “unexpected outcomes”23, such as hyperkalemia, as doctors do not specifically prescribe SGLT-2i or GLP-1RA with the aim to reduce the risk of hyperkalemia41. Second, our primary outcome was defined based on claims-based diagnosis codes, rather than serum potassium measurements. In an internal validation study, we found high specificity (>99%) for serum potassium ≥5.5 or 6.0 mmol/L, thus relative risks in our study should not be affected. Since sensitivity was low (~37%), the absolute risk and rate differences represent an underestimate of the true benefit, and SGLT-2i/GLP-1RA will likely have even larger absolute benefits than that observed in our study compared with DPP-4i. Third, our study had relatively short follow-up, due to a high proportion of patients who discontinued the treatment. However, this represents the reality of routine clinical practice in which many patients have lower adherence to medication compared with trials. Furthermore, the lower risk for hyperkalemia observed for SGLT-2i and GLP-1RA occurred within the first few months of follow-up. As in any study based on health insurance claims, exposure misclassification is possible, especially if patients refill, but do not take their medications; however, in our primary analysis we censored patients if they did not refill medications within a month following the end of the medication supply; moreover, we do not expect any potential exposure misclassification to differ across the treatment groups.

In conclusion, in this cohort study of US individuals with CKD and T2D, SGLT-2i and GLP-1RA were associated with a lower risk of hyperkalemia, compared with DPP-4i. Initiation of these drugs may enable the use of other guideline-recommended medications that improve clinical outcomes but increase serum potassium, such as renin-angiotensin system inhibitors.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1. Definitions of inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Supplementary Table 2. Outcome definitions.

Supplemental Table 3. Definition of subgroup variables cardiovascular disease and heart failure.

Supplementary Table 4. Full list of baseline characteristics in patients with CKD and type 2 diabetes, stratified by SGLT-2i vs. DPP-4i initiation in the pooled cohort, before and after 1:1 propensity score matching.

Supplementary Table 5. Full list of baseline characteristics in patients with CKD and type 2 diabetes, stratified by GLP-1RA vs. DPP-4i initiation in the pooled cohort, before and after 1:1 propensity score matching.

Supplementary Table 6. Full list of baseline characteristics in patients with CKD and type 2 diabetes, stratified by SGLT-2i vs. GLP-1RA initiation in the pooled cohort, before and after 1:1 propensity score matching.

Supplementary Table 7. Individual SGLT-2i, GLP-1RA and DPP-4i agents included in the analysis after 1:1 propensity score matching.

Supplementary Table 8. Follow-up and censoring reasons after 1:1 propensity score matching for (A) SGLT-2i vs. DPP-4i, (B) GLP-1RA vs. DPP-4i and (C) SGLT-2i vs. GLP-1RA.

Supplementary Table 9. Absolute risks and risk differences for the primary outcome at 6-month intervals for SGLT-2i vs. DPP-4i, GLP-1RA vs. DPP-4i and SGLT-2i vs. GLP-1RA.

Supplementary Table 10. Comparative effectiveness of (A) SGLT-2i versus DPP-4i, (B) GLP-1RA vs. DPP-4i and (C) SGLT-2i vs. GLP-1RA on risk of hyperkalemia diagnosis in inpatient or emergency department setting (secondary outcome) before and after 1:1 propensity score matching.

Supplementary Table 11. Comparative effectiveness of (A) SGLT-2i versus DPP-4i, (B) GLP-1RA vs. DPP-4i and (C) SGLT-2i vs. GLP-1RA on risk of serum potassium ≥5.5 mmol/L) before and after 1:1 propensity score matching.

Supplementary Table 12. Comparative effectiveness of individual SGLT-2i and GLP-1RA agents compared with DPP-4i on risk of hyperkalemia diagnosis in inpatient or outpatient setting, after 1:1 propensity score matching.

Supplementary Table 13. Sensitivity analyses: Incidence rate differences and hazard ratios for (A) SGLT-2i vs. DPP-4i, (B) GLP-1RA vs. DPP-4i and (C) SGLT-2i vs. GLP-1RA after 1:1 propensity score matching.

Supplementary Figure 1. Overview of study design.

Supplementary Figure 2. Patient flow chart

Acknowledgments

Funding/support: Dr. Fu is supported by a Rubicon grant from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research. Dr. Lin is supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging RF1AG063381-01 and R01 AG075335. Dr. Patorno is supported by a National Institute of Health grant K08AG055670, PCORI grant DB-2020C2-20326, and a research grant from the Food and Drug Administration (5U01FD007213). Dr. Paik is supported by a National Institute of Health grant AR 075117. Dr. Bykov is supported by a grant from National Institute on Aging (K01AG068365).

Role of the Funder/Sponsor:

The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr. Patorno is investigator of an investigator-initiated grant to the Brigham and Women’s Hospital from Boehringer Ingelheim, not directly related to the topic of the submitted work. Dr. Wexler reports serving on Data Monitoring Committees for Novo Nordisk not related to the topic of this work. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Data Sharing Statement:

A data use agreement is required for each of these data sources. Our data use agreements do not permit us to share patient-level source data or data derivatives with individuals and institutions not covered under the data use agreements. The databases used in this study are accessible to other researchers by contacting the data providers and acquiring data use agreements/licenses.

References

- 1.Clase CM, Carrero JJ, Ellison DH, et al. Potassium homeostasis and management of dyskalemia in kidney diseases: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int. 2020;97(1):42–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nilsson E, Gasparini A, Arnlov J, et al. Incidence and determinants of hyperkalemia and hypokalemia in a large healthcare system. Int J Cardiol. 2017;245:277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Acker CG, Johnson JP, Palevsky PM, Greenberg A. Hyperkalemia in hospitalized patients: causes, adequacy of treatment, and results of an attempt to improve physician compliance with published therapy guidelines. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(8):917–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palmer BF. Managing hyperkalemia caused by inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(6):585–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agarwal R, Joseph A, Anker SD, et al. Hyperkalemia Risk with Finerenone: Results from the FIDELIO-DKD Trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022;33(1):225–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Juurlink DN, Mamdani MM, Lee DS, et al. Rates of hyperkalemia after publication of the Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(6):543–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fu EL, Kutz A, Desai RJ. Finerenone in chronic kidney disease and type 2 diabetes: the known and the unknown. Kidney Int. 2023;103(1):30–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bandak G, Sang Y, Gasparini A, et al. Hyperkalemia After Initiating Renin-Angiotensin System Blockade: The Stockholm Creatinine Measurements (SCREAM) Project. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Desai AS, Swedberg K, McMurray JJ, et al. Incidence and predictors of hyperkalemia in patients with heart failure: an analysis of the CHARM Program. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(20):1959–1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu Y, Fu EL, Trevisan M, et al. Stopping renin-angiotensin system inhibitors after hyperkalemia and risk of adverse outcomes. Am Heart J. 2022;243:177–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trevisan M, Fu EL, Xu Y, et al. Stopping mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists after hyperkalaemia: trial emulation in data from routine care. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021;23(10):1698–1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lyu B, Sang Y, Selvin E, et al. Pharmacologic Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes in the U.S., Sweden, and Israel. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(12):2926–2934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris ST, Patorno E, Zhuo M, Kim SC, Paik JM. Prescribing Trends of Antidiabetes Medications in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes and Diabetic Kidney Disease, a Cohort Study. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(10):2293–2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rossing P, Caramori ML, Chan JCN, et al. Executive summary of the KDIGO 2022 Clinical Practice Guideline for Diabetes Management in Chronic Kidney Disease: an update based on rapidly emerging new evidence. Kidney Int. 2022;102(5):990–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 9. Pharmacologic Approaches to Glycemic Treatment: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2023. Diabetes Care. 2022;46(Supplement_1):S140–S157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaze AD, Zhuo M, Kim SC, Patorno E, Paik JM. Association of SGLT2 inhibitors with cardiovascular, kidney, and safety outcomes among patients with diabetic kidney disease: a meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21(1):47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neuen BL, Oshima M, Agarwal R, et al. Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors and Risk of Hyperkalemia in People With Type 2 Diabetes: A Meta-Analysis of Individual Participant Data From Randomized, Controlled Trials. Circulation. 2022;145(19):1460–1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferreira JP, Zannad F, Butler J, et al. Empagliflozin and serum potassium in heart failure: an analysis from EMPEROR-Pooled. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(31):2984–2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tonneijck L, Muskiet MHA, Blijdorp CJ, et al. Renal tubular effects of prolonged therapy with the GLP-1 receptor agonist lixisenatide in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2019;316(2):F231–F240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tonneijck L, Smits MM, Muskiet MHA, et al. Acute renal effects of the GLP-1 receptor agonist exenatide in overweight type 2 diabetes patients: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetologia. 2016;59(7):1412–1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fu EL, van Diepen M, Xu Y, et al. Pharmacoepidemiology for nephrologists (part 2): potential biases and how to overcome them. Clin Kidney J. 2021;14(5):1317–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schneeweiss S, Patorno E. Conducting Real-world Evidence Studies on the Clinical Outcomes of Diabetes Treatments. Endocr Rev. 2021;42(5):658–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fu EL. Target Trial Emulation to Improve Causal Inference from Observational Data: What, Why, and How? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carrero JJ, Fu EL, Vestergaard SV, et al. Defining measures of kidney function in observational studies using routine health care data: methodological and reporting considerations. Kidney Int. 2023;103(1):53–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paik JM, Patorno E, Zhuo M, et al. Accuracy of identifying diagnosis of moderate to severe chronic kidney disease in administrative claims data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2022;31(4):467–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hawley CE, Lauffenburger JC, Paik JM, Wexler DJ, Kim SC, Patorno E. Three Sides to the Story: Adherence Trajectories During the First Year of SGLT2 Inhibitor Therapy Among Medicare Beneficiaries. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(3):604–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lash TL, Fox MP, Fink AK. , Applying Quantitative Bias Analysis to Epidemiologic Data, 2009. New York, NY: Springer [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fu EL, D'Andrea E, Wexler DJ, Patorno E, Paik JM. Safety of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors in Patients with CKD and Type 2 Diabetes: Population-Based US Cohort Study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim DH, Schneeweiss S, Glynn RJ, Lipsitz LA, Rockwood K, Avorn J. Measuring Frailty in Medicare Data: Development and Validation of a Claims-Based Frailty Index. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2018;73(7):980–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fu EL, Groenwold RHH, Zoccali C, Jager KJ, van Diepen M, Dekker FW. Merits and caveats of propensity scores to adjust for confounding. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2019;34(10):1629–1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Austin PC. Using the Standardized Difference to Compare the Prevalence of a Binary Variable Between Two Groups in Observational Research. Communications in Statistics - Simulation and Computation. 2009;38(6):1228–1234. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med. 2009;28(25):3083–3107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu Y, Cheung YB, Lam KF, Tan SH, Milligan P. A simple approach to the estimation of incidence rate difference. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172(3):334–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Putter H, Fiocco M, Geskus RB. Tutorial in biostatistics: competing risks and multi-state models. Stat Med. 2007;26(11):2389–2430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aetion Evidence Platform® (2022). Software for real-world data analysis. Aetion, Inc. http://aetion.com. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palmer BF. Regulation of Potassium Homeostasis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(6):1050–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tonneijck L, Smits MM, Muskiet MH, et al. Renal Effects of DPP-4 Inhibitor Sitagliptin or GLP-1 Receptor Agonist Liraglutide in Overweight Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: A 12-Week, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(11):2042–2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xie Y, Bowe B, Gibson AK, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of SGLT2 Inhibitors, GLP-1 Receptor Agonists, DPP-4 Inhibitors, and Sulfonylureas on Risk of Kidney Outcomes: Emulation of a Target Trial Using Health Care Databases. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(11):2859–2869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu Y, Fu EL, Clase CM, Mazhar F, Jardine MJ, Carrero JJ. GLP-1 receptor agonist versus DPP-4 inhibitor and kidney and cardiovascular outcomes in clinical practice in type-2 diabetes. Kidney Int. 2022;101(2):360–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sattar N, Lee MMY, Kristensen SL, et al. Cardiovascular, mortality, and kidney outcomes with GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9(10):653–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vandenbroucke JP. Observational research, randomised trials, and two views of medical science. PLoS Med. 2008;5(3):e67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1. Definitions of inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Supplementary Table 2. Outcome definitions.

Supplemental Table 3. Definition of subgroup variables cardiovascular disease and heart failure.

Supplementary Table 4. Full list of baseline characteristics in patients with CKD and type 2 diabetes, stratified by SGLT-2i vs. DPP-4i initiation in the pooled cohort, before and after 1:1 propensity score matching.

Supplementary Table 5. Full list of baseline characteristics in patients with CKD and type 2 diabetes, stratified by GLP-1RA vs. DPP-4i initiation in the pooled cohort, before and after 1:1 propensity score matching.

Supplementary Table 6. Full list of baseline characteristics in patients with CKD and type 2 diabetes, stratified by SGLT-2i vs. GLP-1RA initiation in the pooled cohort, before and after 1:1 propensity score matching.

Supplementary Table 7. Individual SGLT-2i, GLP-1RA and DPP-4i agents included in the analysis after 1:1 propensity score matching.

Supplementary Table 8. Follow-up and censoring reasons after 1:1 propensity score matching for (A) SGLT-2i vs. DPP-4i, (B) GLP-1RA vs. DPP-4i and (C) SGLT-2i vs. GLP-1RA.

Supplementary Table 9. Absolute risks and risk differences for the primary outcome at 6-month intervals for SGLT-2i vs. DPP-4i, GLP-1RA vs. DPP-4i and SGLT-2i vs. GLP-1RA.

Supplementary Table 10. Comparative effectiveness of (A) SGLT-2i versus DPP-4i, (B) GLP-1RA vs. DPP-4i and (C) SGLT-2i vs. GLP-1RA on risk of hyperkalemia diagnosis in inpatient or emergency department setting (secondary outcome) before and after 1:1 propensity score matching.

Supplementary Table 11. Comparative effectiveness of (A) SGLT-2i versus DPP-4i, (B) GLP-1RA vs. DPP-4i and (C) SGLT-2i vs. GLP-1RA on risk of serum potassium ≥5.5 mmol/L) before and after 1:1 propensity score matching.

Supplementary Table 12. Comparative effectiveness of individual SGLT-2i and GLP-1RA agents compared with DPP-4i on risk of hyperkalemia diagnosis in inpatient or outpatient setting, after 1:1 propensity score matching.

Supplementary Table 13. Sensitivity analyses: Incidence rate differences and hazard ratios for (A) SGLT-2i vs. DPP-4i, (B) GLP-1RA vs. DPP-4i and (C) SGLT-2i vs. GLP-1RA after 1:1 propensity score matching.

Supplementary Figure 1. Overview of study design.

Supplementary Figure 2. Patient flow chart

Data Availability Statement

A data use agreement is required for each of these data sources. Our data use agreements do not permit us to share patient-level source data or data derivatives with individuals and institutions not covered under the data use agreements. The databases used in this study are accessible to other researchers by contacting the data providers and acquiring data use agreements/licenses.