I. Introduction

A growing literature in development economics identifies early life health in general (Currie and Vogl 2013) and exposure to infectious disease in particular (Cutler et al. 2010) as important factors shaping adult human capital and economic productivity.1 Against this background, it is no surprise that open defecation in India has emerged as a top development and health policy priority. The current draft of the Sustainable Development Goals calls for the elimination of open defecation within 15 years. Although the goal is global, achieving it will depend on rural India, where most people worldwide who defecate in the open live. The prime minister of India has set a more ambitious target: eliminating open defecation from India is a flagship priority for his 5-year tenure. The World Bank, the Gates Foundation, and other development funders have allocated considerable resources to this goal. Therefore, it is clear that better understanding the causes of open defecation in India is a priority for evidence-based policy.

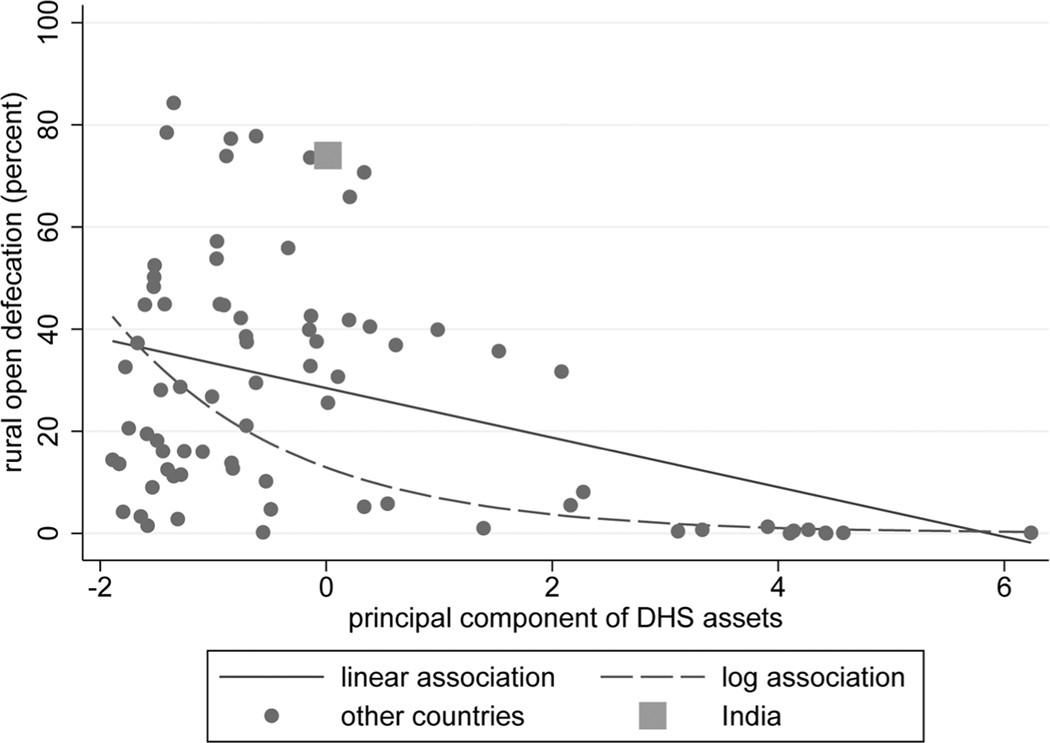

The unique persistence of open defecation in rural India is also a puzzle for the study of behavior and choice in economic development. Indeed, causes of sanitation behavior have recently received increasing attention from economists (Duflo et al. 2015; Guiteras, Levinsohn, and Mobarak 2015). India has been experiencing rapid economic growth, and people in India are richer, on average, than people in sub-Saharan Africa and many other developing countries in Asia; yet people in India are considerably more likely to defecate in the open than people in many of these poorer countries. Indeed, many people in rural India who own (or could afford to buy or make) functioning latrines that meet international quality standards nevertheless choose to defecate in the open (Clasen et al. 2014; Coffey et al. 2014). As an initial illustration of the paradox, consider figure 1, which plots rural open defecation against rural asset wealth for recent Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), each conducted in one country in 1 year.2 Of 51 countries poorer than India by this measure, only four small countries (with a combined population less than 4% as large as India’s) have higher rates of rural open defecation than India. No country has a larger difference than India between the open defecation it experiences and what would be predicted based on its wealth (see fig. 1 note). Because India’s most recent DHS was in 2005 and open defecation has fallen more quickly in the rest of the world than in India, the puzzle would be even more stark today.

Figure 1.

Open defecation in India in international comparison. Each observation represents one Demographic and Health Survey, which is a country in a year. Most of these surveys are from sub-Saharan Africa. All 77 surveys that observe toilet facilities, electrification, and ownership of radio, television, mobile phone, any phone, and refrigerator are included: the horizontal axis is the first principal component of these assets other than toilets. The four countries with higher unconditional rural open defecation than India are Benin, Burkina Faso, Namibia, and Niger, which collectively have a combined population less than 4% of that of India; the two circles representing countries with open defecation just below India are Togo and an earlier Namibian survey round. The linear specification has an R2 of 15%; the log specification has an R2 of 44%. Open defecation in India in 2005 was 61 percentage points greater than would be predicted by the first principal component of these assets in the log specification, which is the largest residual among these observations. A color version of this figure is available online.

One candidate explanation for the exceptional prevalence and persistence of open defecation in rural India is the culture of purity and pollution that reinforces and has its origins in the caste system (Coffey et al. 2016). Such an explanation is inherently difficult to quantitatively test: culture is a general equilibrium of reinforcing and varying factors, enacted to different degrees and in different ways in different places and times.3 Ideally, we would want to compare open defecation in the India that exists with open defecation in a hypothetical counterfactual India that had not been influenced by the norms of purity and pollution of the caste system. Instead, what we are able to do in this paper is to compare across places in India where these norms are practiced with greater and lesser intensity.

We exploit a novel question in the 2012 round of the India Human Development Survey: households were asked explicitly whether they practice untouchability, meaning whether they enforce norms of purity and pollution in their interactions with people from the lowest-ranking castes (Thorat and Joshi 2015). Unlike many prior quantitative studies that document caste discrimination as an outcome (see, e.g., Kijima 2006; Thorat and Newman 2007; Hanna and Linden 2012; Hnatkovska, Lahiri, and Paul 2012; Deshpande and Spears 2016), we use village average practice of untouchability as an explanatory variable, in an effort to understand whether heterogeneity across rural India in the practice of purity and pollution can explain heterogeneity within India in open defecation. To the extent that the effects of purity, pollution, and caste in fact occur in a general equilibrium of widely shared cultural understandings and practices, what we are able to estimate will be a muted effect on a small range of variation. Nevertheless, because the association we find is robust and is specific to a link between the practices of untouchability and open defecation, we believe our results are informative about the puzzle of Indian open defecation. In particular, this paper takes very seriously the possibility that household reports of practicing untouchability could be confounded by knowledge of the health consequences of sanitation or by other dimensions of modernity or development. We show that the practice of untouchability does not similarly predict other health-promoting behaviors and is not associated with disadvantage in health beliefs or in social ties to doctors.

Our paper builds directly on a related recent literature. First, qualitative research by Coffey et al. (2016) advanced the hypothesis that the culture of caste-related purity and pollution in India is importantly responsible for exceptional and continuing rural open defecation.4 Second, Guiteras et al. (2015) report a field experiment from rural Bangladesh that identifies a role for social forces in sanitation behavior, finding that people are influenced by neighbors’ latrine use.5 Third, Geruso and Spears (2015) document that Muslim households in India are 25 percentage points less likely to defecate in the open than Hindu households, despite being poorer. They exploit this fact to explain a puzzle in the health literature: that despite being poorer, Muslim babies in India are importantly more likely to survive childhood than Hindu babies (Bhalotra, Valente, and Van Soest 2010). Finally, Thorat and Joshi (2015) use the same survey question on untouchability that we exploit in order to document and describe the continuing practice of untouchability in India.

To be explicit: this is not a design-based paper, in the sense of Angrist and Pischke (2010), that would use a natural experiment to estimate the exogenous causal effect of untouchability on open defecation. Indeed, we have only approximate measures of the culture of purity and pollution and of open defecation; because of this measurement error and because of the comparatively small range of variation within India, the true effect may be larger than we can document. Instead, we use a unique new data source to shed the first quantitative light on a question of top economic and policy importance: Why is open defecation in rural India so uniquely widespread and persistent? We argue that our results are sufficiently able to rule out alternative explanations for the robust and specific association we document that we can interpret this association as evidence that the caste-related culture of purity and pollution is part of what maintains open defecation in rural India. If so, one consequence would be that the practice of casteism has social costs not only for members of disadvantaged castes but also for all Indians who are impacted by the health externalities of widespread open defecation.

II. Background: Caste, Untouchability, and Sanitation

India’s caste system divides people into many groups called jatis. Although some members of other religions claim or are ascribed jatis, this system is particularly associated with Hinduism and is outlined in Hindu sacred texts. There exist around 3,000 different jatis (also referred to as castes or subcastes) in India.6 Outside of the ranked classification of the caste system lies the fifth group: the untouchables (sometimes called ex-untouchables) or the avarnas. The exuntouchables are now also referred to by the state as scheduled castes, in reference to a schedule (i.e., explicit list) of castes that are eligible for government affirmative action programs. These groups are also known as Dalits, from a word meaning “oppressed” or “crushed.” Dalit groups have traditionally been assigned to specific occupations and have been economically and socially marginalized. Although untouchability is now technically illegal, discrimination against Dalits persists in nearly all aspects of human development (Deshpande 2011).

The caste system is justified and enacted according to a cultural set of norms and beliefs surrounding ritual purity and pollution. According to Hindu religious belief, untouchables are considered to be polluting to other social groups in part because of the occupations carried out by them in the past and, in some cases, still today. Characteristically Dalit occupations such as the manual removal of feces from high-caste homes or the handling of animal corpses are seen to pollute those who undertake them.

Aktor (2002) offers an account of purity and pollution in the Hindu caste system. In this system, it is important to maintain the purity of the body and of the home. Special norms govern the body of a Brahmin male household head in order for him to be able to worship. Certain actions and interactions—especially with people lower ranking in the caste hierarchy of purity—cause him to be polluted. Contact with death and dead bodies, feces, urine, saliva, menstruating women, the cremator of dead bodies, disabled people, foreigners, and especially Dalits are all characteristically considered to be highly polluting. According to these principles, caste Hindus must either avoid these situations or subsequently undergo purification rituals, such as particular forms of bathing with clothes on, recitation of chants, or sprinkling of cow urine (Routray et al. 2015).7 The slightest touch or even the shadow of polluted persons is polluting. In contrast with members of higher castes who can be purified, Dalits are permanently polluted.

The ideal form of the Hindu home is organized around a shrine or small temple for prayer. Rural Indians refer to the purity of these shrines when describing why it is defiling and polluting to have a toilet as part of a house (Coffey et al. 2016). Thus, those latrines that exist in rural India are constructed away from the structure of the house; open defecation—ideally in a field—serves even better to preserve the purity of the home.8

So one mechanism by which the culture of purity and pollution discourages latrine use is the perceived threat of polluting the home by accumulating feces nearby. In contrast, early morning open defecation contributes to the wholesome purification of the body, especially for males (Coffey et al. 2016). Another mechanism is concern about the eventual emptying of latrine pits and disposal of accumulated feces. Unlike in other developing countries, where latrine pit emptying is an undesirable or low-status job but is one that is governed by market norms, in India, for caste Hindus, it would be inconceivable to empty a latrine pit or to expect anyone to do so other than a Dalit. However, Dalits are increasingly, if very slowly, resisting assignment to such tasks—the clearest markers of their oppression. Moreover, many rural Indians mistakenly believe standard latrine leach pits will fill an order of magnitude more quickly than is actually the case, requiring frequent emptying, a situation that many find to be highly polluting. As a result, the few latrines one observes in use in rural India are often constructed with very large septic tanks meant to last for decades without needing to be emptied.

In short, when many people in rural India compare the costs and benefits of latrine use and open defecation, aspects of the culture of caste-related purity and pollution encourage open defecation. Although further detail on this culture and its practice in rural India is beyond the scope of this econometric paper, Coffey et al. (2016) present a detailed account of the links between untouchability and open defecation, grounded in semistructured qualitative interviews across field sites in India and the plains of Nepal and with further reference to the existing ethnographic literature on caste and sanitation.9

An extreme form of the practice of purity and pollution is to treat members of Dalit castes according to the rules of untouchability. The novel survey data collected and reported by Thorat and Joshi (2015) document that many people in rural India readily admit to practicing untouchability. Therefore, we hypothesize that places where the practice of untouchability is more common will be places where open defecation is more common, on average.

Section III presents our empirical strategy to test this hypothesis: we compare open defecation behavior of households living in places where larger and smaller proportions of a household’s neighbors report practicing untouchability, controlling for a household’s own practice of untouchability. Section IV reports our main result. Section V presents a series of tests in which we allow the data to falsify our assumption that the relationship between open defecation and untouchability is specific to sanitation rather than health investments or modern behavior more broadly. Section VI offers a concluding discussion that considers differences across Indian states and reflects on our results in the internationally comparative context that motivated our analysis.

III. Data and Empirical Strategy

A. Rural Households in the Indian Human Development Survey

We use the 2012 round of the India Human Development Survey (IHDS), a nationally representative survey of approximately 40,000 households in India (Desai, Dubey, and Vanneman 2005).10 The IHDS is unique among nationally representative surveys of India because it combines a full economic consumption module with a wide range of social, health, and human development questions comparable to a Demographic and Health Survey. In particular, the IHDS asks a household-level question about household latrine ownership, partially conflated with behavior in the coding of the answer as “No facility belonging to household (or open fields)” in the questionnaire. Following the labeling in the IHDS and convention in this literature, we dichotomize this question into a binary indicator that we will refer to as household “open defecation” as our main dependent variable. However, we emphasize here that this variable will overlook the well-documented fraction of people who do not use latrines owned by their household (Coffey and Spears 2014).11

We concentrate only on the rural subsample, excluding urban households from our analysis. This is because open defecation in India is concentrated in rural India: according to the 2011 census of India, 92% of households without access to a toilet or latrine were rural rather than urban. The IHDS similarly estimates that 89% of households reporting defecating in the open in 2012 were rural. Rural India is also widely agreed to be where there exists the social scientific puzzle that open defecation generally represents choice and behavior rather than affordability: it is in rural India where open defecation rates vastly exceed what would be predicted by wealth in international comparison and where people who have the option of using a working latrine often choose to defecate in the open instead (Coffey et al. 2014).

B. Empirical Strategy: Casteism as an Explanatory Variable

An innovation of the 2012 IHDS is to ask respondents whether their households practice untouchability, meaning whether or not their households enforce norms of purity and pollution in their interactions with Dalits, who are members of the lowest-ranking Indian castes. To our knowledge, no prior large-scale survey in India has measured the practice of untouchability (the 2005 round of the IHDS did not include it either). To be clear, this question was put to households of all castes: it was intended as a coarse measure of a household’s practice and enforcement of untouchability in interactions with Dalits and not as a measure of whether the household is Dalit, which is asked separately.12

Our empirical strategy is to demonstrate, first, that households that report practicing untouchability are more likely to defecate in the open and, second, that villages where more households practice untouchability contain more open defecation. Thus, we estimate

where indexes individual households, indexes villages (survey primary sampling units [PSUs]), and indexes Indian states. The constructed variable practice untouchability is the fraction of households in household ’s village other than household itself that report practicing untouchability.13 The is a vector of controls, which will vary to demonstrate robustness; are state fixed effects. Because the IHDS is a two-stage sample survey, errors will be clustered at the PSU level.

The associations we find are strikingly robust and are not driven by poverty, education, health knowledge, or the caste or religious composition of households or villages. However, we do not claim to have quantitatively identified any causal effect of casteism on open defecation: both our dependent and independent variables are dichotomized measurements, with error, of complicated and multi-dimensional phenomena.14 Rather, we believe that the consistency and specificity of the association between open defecation and the practice of untouchability is evidence that the culture of caste-related purity and pollution, of which untouchability is an extreme manifestation, is an important part of what explains exceptionally widespread and persistent open defecation in India.

Our analysis takes seriously two threats to this interpretation: first, that practicing untouchability is associated with disadvantage more broadly and, second, that belief in the norms around untouchability may merely mark failure to believe in the germ theory of disease or other health knowledge that would discourage open defecation. It is true both that poorer people in rural India are more likely to report practicing untouchability and that the culture of purity and pollution includes a theory of the body that is not identical to scientific medical understandings of disease (Alter 2004).15 However, the rich data of the IHDS allow us to rule out these more general phenomena. First, in Section I, we allow the data the opportunity to falsify our hypothesis of a specific association between casteist practice and open defecation: controlling for socioeconomic status, practicing untouchability fails to similarly predict any of a wide range of health- and human-development-promoting behaviors. Second, in Section V.B, we show that rural Indian households that report practicing untouchability are, if anything, more likely to correctly answer questions about health beliefs and more likely to report knowing a doctor in their family or caste network. These potentially surprising health advantages may be because practicing untouchability is associated with higher caste rank, which is associated with educational advantage. These advantages in health knowledge do relevantly predict less open defecation behavior; however, accounting for them does not change the association between practicing untouchability and open defecation. Therefore, we show that the association between widespread local practice of untouchability and open defecation is statistically robust, is specific to open defecation among health and human development behaviors, and does not merely reflect general health knowledge or belief.

C. Independent Variable: The Practice of Untouchability

Following Thorat and Joshi (2015), we build our measure of untouchability from two questions in the IHDS asked of each household respondent:

In your household, do some members practice untouchability?

if no to A. Would there be a problem if someone who is scheduled caste were to enter your kitchen or share utensils?

Throughout this paper, we will use two measures of household untouchability practice to verify robustness. We will call “untouchability A” an answer of yes to the first question; we will call “untouchability B” an answer of yes to either question. By construction, untouchability B will be a larger fraction of households than untouchability A. Note that because untouchability is measured at the household level, it will capture with error cases in which some household members practice untouchability and others do not. Moreover, practiced untouchability may exceed reported untouchability if some people who practice untouchability did not admit this to the surveyor.

Figure A1 provides an approximate validation of households’ reports of practicing untouchability. Dalit households—which would be the households vulnerable to discrimination and to receiving the practice of untouchability—were asked, “In your household, have some members experienced untouchability in the last 5 years?” As the figure shows, Dalit respondents are more likely to report experiencing untouchability if they live in villages where a larger fraction of the other households report practicing untouchability.

D. Summary Statistics

Table 1 presents summary statics from the IHDS. We present results for the full sample and separated by answers to the IHDS untouchability questions. As the table shows, almost two-thirds of rural households report defecating in the open. These rural households are largely in the agricultural economy and are 84% Hindu; Muslims in India are relatively more likely to live in urban places. Only three-fourths of households have a literate member, and only about two-fifths include someone who reads the newspaper.

TABLE 1.

SUMMARY STATISTICS, RURAL INDIA HUMAN DEVELOPMENT SURVEY 2012

| Untouchability A: 24% |

Untouchability B: 31% |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Yes | No | t-Statistic | Yes | No | t-Statistic | |

| Open defecation | .64 | .71 | .62 | 6.57 | .71 | .61 | 6.82 |

| Consumption per capita | 21,511 | 20,339 | 21,873 | −2.60 | 20,784 | 21,830 | −1.86 |

| ln(consumption per capita) | 9.73 | 9.69 | 9.74 | −2.36 | 9.70 | 9.74 | −1.55 |

| Own or cultivate land | .61 | .73 | .57 | 11.33 | .72 | .56 | 12.54 |

| Household size | 4.77 | 4.91 | 4.73 | 3.01 | 4.93 | 4.70 | 4.23 |

| Any literate adult | .75 | .73 | .75 | −2.55 | .74 | .75 | −1.30 |

| Any primary-schooled adult | .68 | .66 | .68 | −1.44 | .68 | .68 | .04 |

| Men read newspaper | .41 | .40 | .41 | −.60 | .41 | .41 | .31 |

| Women read newspaper | .19 | .16 | .20 | −3.39 | .16 | .20 | −3.11 |

| Hindu | .84 | .93 | .82 | 9.23 | .92 | .81 | 8.86 |

| Muslim | .10 | .05 | .11 | −6.09 | .06 | .12 | −5.47 |

| Brahmin caste | .04 | .09 | .03 | 8.08 | .08 | .02 | 8.38 |

| Other backward class | .42 | .52 | .39 | 7.83 | .53 | .37 | 9.28 |

| Scheduled caste/Dalit | .24 | .12 | .27 | −10.48 | .13 | .28 | −11.14 |

| Scheduled tribe/Adivasi | .11 | .08 | .12 | −3.02 | .08 | .12 | −2.93 |

| Northern plains state | .37 | .60 | .30 | 14.13 | .58 | .28 | 14.29 |

| Southern state | .21 | .10 | .24 | −8.53 | .12 | .24 | −6.51 |

| n rural households | 27,322 | 6,507 | 20,815 | 8,681 | 18,642 | ||

Note. The t-statistic tests whether the mean is the same for households that do and do not report practicing untouchability; standard errors are clustered by survey primary sampling units. “Untouchability A” refers to reports of practicing untouchability; “untouchability B” refers to “untouchability A” or reports of not allowing a Dalit into the kitchen.

Explicit reporting of practicing untouchability to the IHDS surveyor is common in this rural sample: 24% of respondents openly reported practicing untouchability; 31% said yes to this question or to the kitchen question.16 The summary statistics in the table allow simple comparisons of means between households that do and do not report practicing untouchability, without any regression controls. The comparison for untouchability B is particularly striking: households that practice untouchability have only 4% less consumption per capita, are only 1 percentage point less likely to have a literate adult, and are not at all less likely to have an adult with a primary school education or a man who reads the newspaper; none of these differences are statistically significant from zero. Yet they are 10 percentage points more likely to report defecating in the open, a difference with a t-statistic of 6.8. Thus, these summary statistics are initial evidence of a specific association between open defecation and the practice of untouchability, which will be further investigated in the remainder of this paper.

IV. Results

A. Main Result: Local Casteism and Open Defecation

1. Household-Level Differences

Because we are interested in the consequences of rural India’s widely shared culture of purity, pollution, and caste, our main results will focus on ¯practice untouchability , the fraction of a household’s neighbors that report practicing untouchability. However, in this section, we begin with a simple comparison of households that do and do not practice untouchability to permit a visual demonstration that these differences are not obviously confounded by education or wealth.

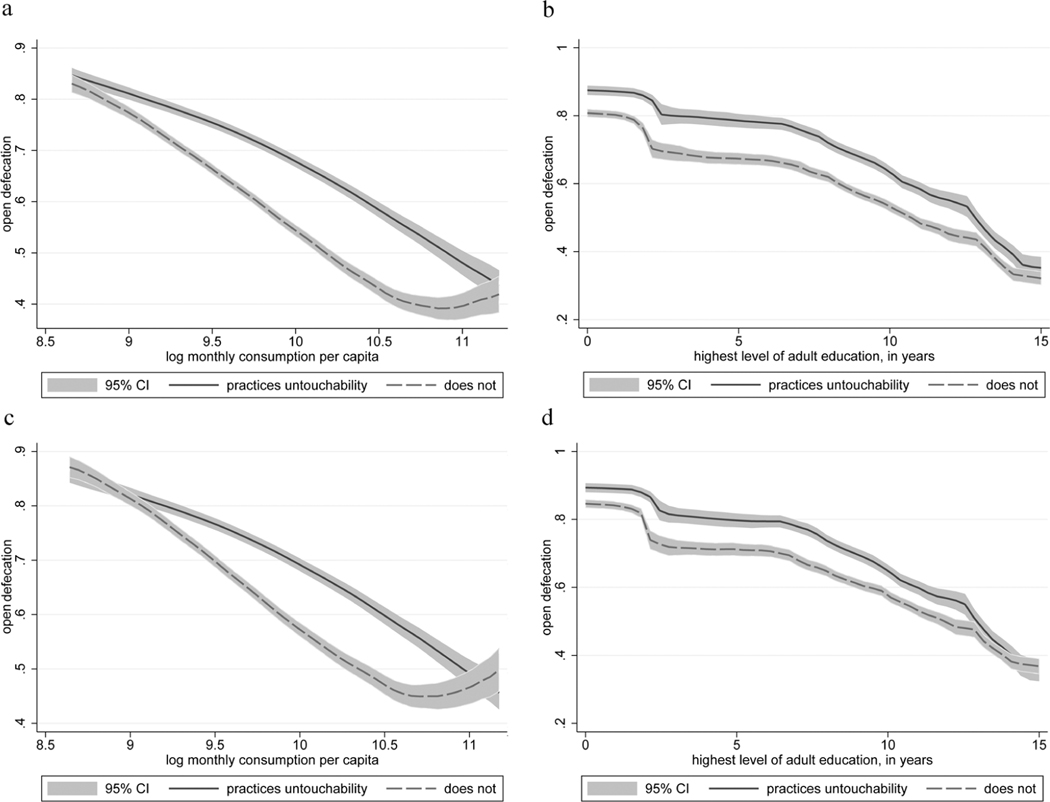

Figure 2 plots local regressions of the fraction of households that defecate in the open at different levels of consumption and of education, with those that do and do not report practicing open defecation plotted separately. The solid lines are for households that report practicing untouchability; the dashed lines are for households that do not. In each graph, all lines slope downward, consistent with the fact that richer and better-educated households are less likely to defecate in the open. The vertical distance between the lines is evidence of an association between the norms of untouchability and open defecation that is not able to be explained by consumption or education. For example, the vertical distance between the lines in panel a at 10.5 is large; this corresponds to an average annual consumption per person of about $700 at market exchange rates and is the 89th percentile of households in our data.17 The international experience of much lower open defecation rates in poorer countries is clear evidence that nearly all such households could afford to construct and use a toilet, but those who do not practice untouchability are much more likely to do so. Similarly, note that a majority of households with a tenth-pass high school graduate defecate in the open; open defecation among this relatively privileged minority exceeds the fraction of all people in rural sub-Saharan Africa who defecate in the open, including the poorest.

Figure 2.

Household untouchability practice and open defecation at all levels of consumption and education: consumption, all rural households (a); education, all rural households (b); consumption, rural Hindu households (c); and education, rural Hindu households (d). Samples are split by untouchability B: reported practice of untouchability directly or of not allowing a Dalit in the kitchen. A color version of this figure is available online.

Panels c and d of figure 2 restrict the sample to the 84% that are Hindu. Hindu households in our sample are more than twice as likely as non-Hindu households to report practicing untouchability: 33% of Hindus versus 15% of non-Hindus. Similarly, 14 percentage points more of the average Hindu household’s neighbors report practicing untouchability than the average non-Hindu household’s neighbors. However, the norms of purity and pollution are enacted among non-Hindus and are enacted with varying intensity among Hindus. These bottom panels verify that untouchability is not merely a marker for dichotomized Hinduism per se and that heterogeneity in these norms within Hindus predicts heterogeneity in sanitation behavior.

2. Village Average Practice of Untouchability

Table 2 presents the main result of this paper: the association of neighbors’ average practice of untouchability with a household’s open defecation. Panel A uses “untouchability A” as the independent variable, directly reported untouchability. Panel B uses “untouchability B,” which adds to untouchability A households reporting that it would be a problem to have a Dalit in the kitchen.

TABLE 2.

MAIN RESULT: OPEN DEFECATION AMONG RURAL HOUSEHOLDS AND VILLAGE UNTOUCHABILITY PRACTICE, RURAL INDIA HUMAN DEVELOPMENT SURVEY 2012

| Full |

Hindu |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) |

| A. Untouchability A (Directly Reported) |

||||||||

| Household untouchability | .0967† | .0879† | −.00662 | .0196* | .0000556 | −.00276 | .0195* | −.000236 |

| (.0147) | (.0136) | (.0102) | (.0102) | (.0101) | (.00961) | (.0108) | (.0107) | |

| Village untouchability−i | .336† | .233† | .182† | .0743*** | .228† | .178† | ||

| (.0335) | (.0320) | (.0315) | (.0267) | (.0336) | (.0334) | |||

|

|

||||||||

| B. Untouchability B (Directly Reported or Kitchen) | ||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Household untouchability | .0986† | .0929† | −.00926 | .0232** | .00812 | .00513 | .0208* | .00594 |

| (.0144) | (.0135) | (.0101) | (.0102) | (.00994) | (.00942) | (.0110) | (.0107) | |

| Village untouchability−i | .303† | .205† | .166† | .0586** | .208† | .169† | ||

| (.0307) | (.0295) | (.0287) | (.0264) | (.0312) | (.0307) | |||

| ln(consumption/capita)3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Own caste group × religion | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Extended controls | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| State fixed effects | ✓ | |||||||

| n (rural households) | 27,320 | 27,320 | 27,320 | 27,320 | 27,320 | 27,320 | 22,833 | 22,833 |

Note. The dependent variable is an indicator for the household reporting open defecation. Village untouchability−i is the fraction of households other than the respondent’s who report practicing untouchability in the respondent’s village. Monthly consumption per capita is included as a cubic polynomial. “Extended controls” are household size in persons, whether the household owns or cultivates land, whether the household has a literate member, the educational achievement of the head of the household, the education of the head of the household’s father, and four sets of indicators for whether men and women listen to the radio or read the newspaper sometimes or regularly; each extended control variable is entered fully nonparametrically as a set of separate indicators for each level or count of the variable. Standard errors, clustered by village, are in parentheses.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Before presenting the village-level result, the first two columns of the table verify the statistical significance and robustness of the difference across households presented in figure 2. The approximately 9 percentage point average difference in open defecation rates between households that do and do not practice untouchability is essentially unchanged by adding controls for a cubic polynomial of consumption per capita and indicators for 35 combinations of caste rank and religion (e.g., for being a Hindu Brahmin or a Muslim of other backward class). Thus, this result does not merely reflect the household’s own wealth, religion, or caste rank.

Column 3 of table 2 introduces our main independent variable: fraction of households in the PSU other than the respondent that reports practicing untouchability. We interpret this variable as a measure of the intensity of the cultural norms of caste-related purity and pollution in a place. Households living in villages where all of their neighbors practice untouchability are more than 30 percentage points more likely to defecate in the open than households living in villages where none of their neighbors practice untouchability. As an alternative interpretation, a 1 standard deviation increase in village untouchability is associated with a household being 8 percentage points more likely to defecate in the open. Once village untouchability is added to the model, the coefficient on own household practice of untouchability becomes much smaller and not statistically significantly different from zero.18 The coefficient on village untouchability becomes smaller when a large set of economic, educational, demographic, and caste variables are added but remains of important magnitude.19 Comparing column 4 with column 7 and column 5 with column 8, we see that the coefficient on village untouchability is essentially unchanged if the sample is restricted to Hindus.

The importance for rural life of caste-based norms of purity and pollution varies geographically across India. As the last two rows of the summary statistics table 1 show, 60% of households that report practicing untouchability live in northern plains states (which are home to 37% of rural households); households that report not practicing untouchability are statistically significantly more likely to live in southern states. Overall, a set of indicators for each state can account for 17% of the variation in the practice of untouchability across the rural households we study. Therefore, controlling for state fixed effects absorbs much of the variation that is important both in the culture of purity and pollution and in open defecation (see Sec. V.C). That said, column 6 of table 2 shows that village average practice of untouchability remains associated with open defecation behavior, even within states and after accounting for our set of extended controls.20

One potential concern about this specification is measurement error: we observe only a dichotomized indicator of the practice of untouchability, itself only one dimension of norms of purity and pollution. This is not a debilitating concern because it is not our goal to uncover a “causal effect of untouchability”; rather, we intend to provide evidence of the importance of the culture of purity and pollution to open defecation in rural India. That said, if as a partial response to measurement error we use household and village untouchability A to instrument for untouchability B in the fully controlled specification of column 6, then the coefficient on village untouchability rises slightly to 0.080 with a standard error of 0.029.

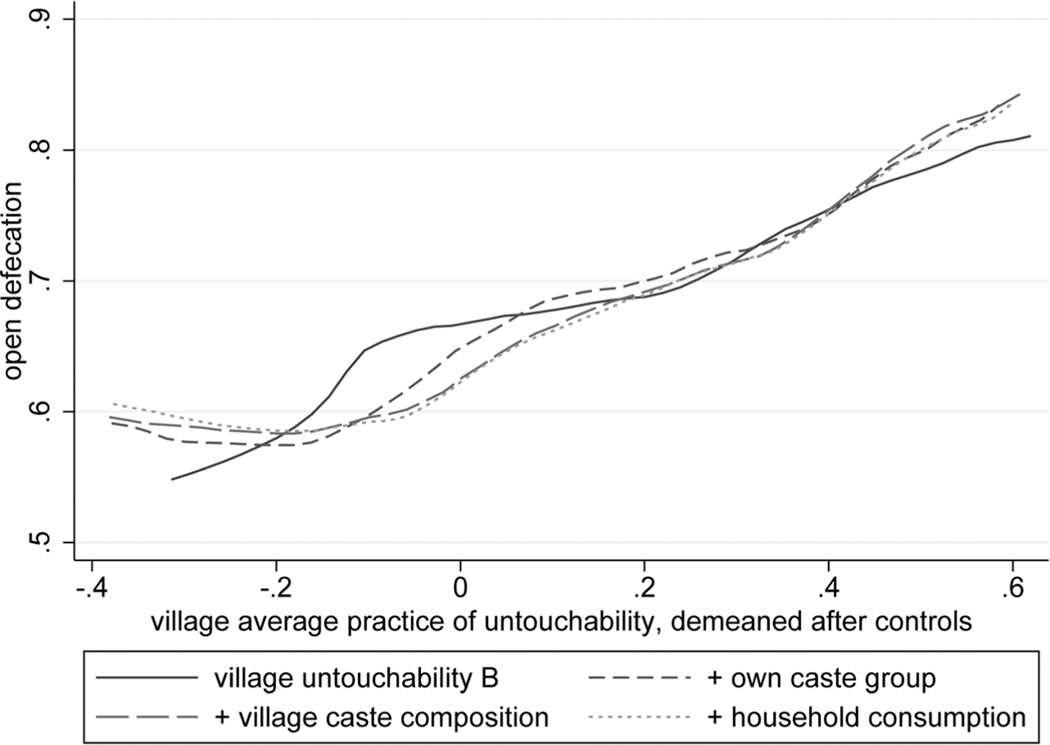

Figure 3 permits us to assess the linearity of the relationship between village untouchability and open defecation, implicitly assumed by our regression framework, and to visualize the robustness of the relationship to regression controls. The graph plots the fraction of households defecating in the open at each level of village untouchability, where village untouchability has been residualized after regression on various sets of controls. In other words, the four horizontal-axis variables in the figure are as follows:

Figure 3.

Village average untouchability practice and open defecation. A color version of this figure is available online.

The fraction of households reporting practicing untouchability, demeaned by the average across villages.

The village-level average of the household-level residuals after regressing an indicator for practicing untouchability on indicators for eight caste and religion groups.

The average of the residuals after regressing an indicator for practicing untouchability on the same household-level indicators and seven continuous variables for the fraction of village households in each of these groups.

The average of the residuals after regressing an indicator for practicing untouchability on all of the previous variables and household consumption.

The figure shows that the shape of the association between village practice of untouchability and caste is robust to these controls for caste itself and for household consumption. Village practice of untouchability does not merely reflect the caste or religion composition of the village.

B. Village-Level Decline in Open Defecation, 2005–12

Over the 7 years between the first and second waves of the IHDS, open defecation in rural India declined by 7.4 percentage points. This rate of about 1 percentage point per year approximately matches the decline from 78.1 in the 2001 census of India to 69.3 in the 2011 census. Because the practice of untouchability was not measured in the 2005 round of the IHDS, we cannot observe whether change in the practice of untouchability predicts change in open defecation, although we would expect such a long-standing and pervasive norm to change only slowly.

Instead, table 3 investigates whether the village-level decline in open defecation, measured as a percent of the 2005 level of open defecation, was greater on average in villages where the 2012 fraction of the village reporting practicing untouchability is smaller. Indeed, the table shows that the average decline was less than half as large in villages where all households reported practicing open defecation than in villages where no households did. Controls added in columns 2 and 3 verify that this result is not due to differences in economic change over this period or in baseline levels of open defecation. Column 4 adds controls for the fraction of the village belonging to each of eight caste and religion population groups. If anything, this slightly increases the coefficient on untouchability, suggesting that it is not merely a spurious marker for village composition.

TABLE 3.

UNTOUCHABILITY AND VILLAGE-LEVEL CHANGE IN OPEN DEFECATION, 2005–12

| Change in Village Open Defecation (% Decrease) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Village untouchability practice, 2012 | 13.09*** | 12.59*** | 13.46*** | 15.50† |

| (4.282) | (4.398) | (4.634) | (4.519) | |

| Village average consumption change | 6.574 | 6.591 | 6.333 | |

| (4.360) | (4.344) | (4.230) | ||

| Village open defecation, 2005 | −5.317 | −23.24* | ||

| (10.08) | (11.89) | |||

| Caste and religious composition | F7, 1,317 = 6.35 | |||

| p < .001 | ||||

| Constant | −22.57† | −24.39† | −20.64** | 733.7*** |

| (2.087) | (2.219) | (8.570) | (272.4) | |

| n (rural villages) | 1,329 | 1,329 | 1,329 | 1,329 |

Note. The dependent variable is the village-level reduction in the fraction of households reporting open defecation as a percent of the initial fraction of households defecating in the open. “Village untouchability practice, 2012” is the fraction of the village reporting practicing untouchability B (directly reported or kitchen); untouchability was not observed in the 2005 India Human Development Survey (IDHS). Consumption change from 2005 to 2012 is in units of natural logarithm of rupees per month per capita. “Caste and religious composition” is a set of measures of the fraction of households in the primary sampling unit in each of eight groups: Brahmin, other forward caste, other backward class, Dalit, Adivasi, Muslim, a group for Sikh or Jain, and Christian, with the first four caste groups defined by the IHDS to be subsets of the 84% of rural households that are Hindu. Robust standard errors are in parentheses (data are collapsed by cluster).

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

V. Falsiflcation Tests

We interpret the robust relationship between village average practice of untouchability and open defecation as evidence that the culture of caste-related purity and pollution is important for the continuing high levels of open defecation in India. This section presents two tests of alternative hypotheses that could falsify our interpretation. First, we test whether the association between casteism and open defecation is specific or whether the practice of untouchability similarly predicts a wide range of behaviors associated with traditional lifestyles, disadvantage, or health and human capital. Second, we have seen that untouchability does not merely reflect education; we further test whether the practice of untouchability is merely a marker for incorrect beliefs about what would promote health.

A. Specificity of the Casteism-Sanitation Association

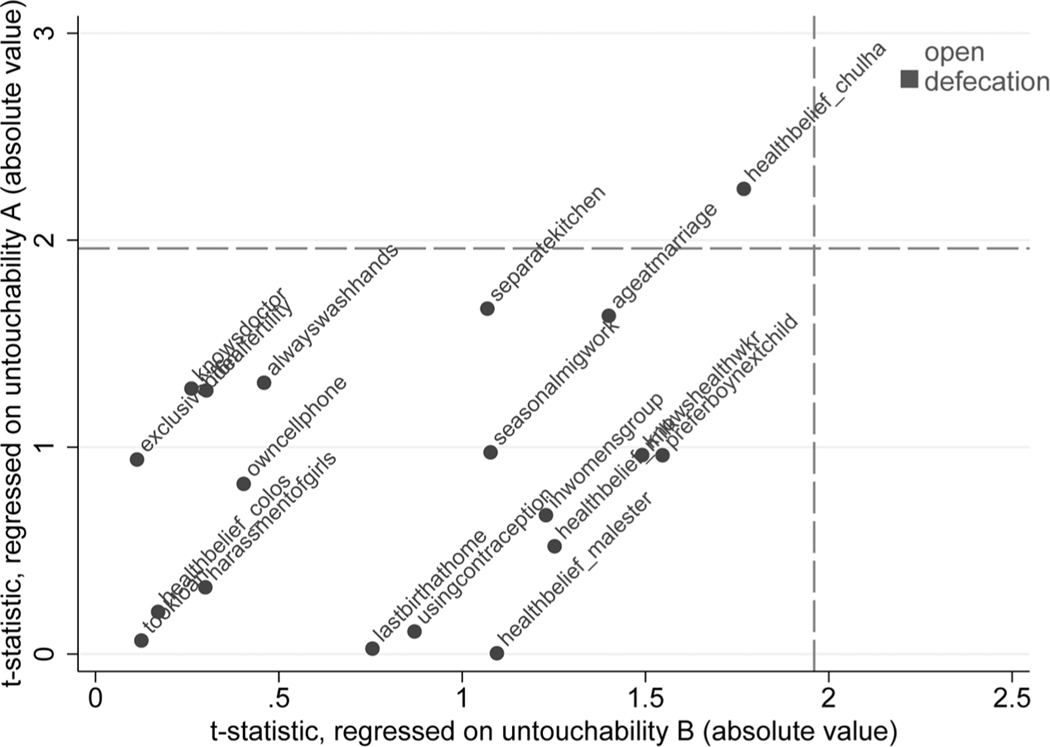

Figure 4 summarizes results from regressions of the form of equation (1) with 20 separate dependent variables substituted in turn, with the full set of controls from column 6 of the main results in table 2.21 Each regression is repeated for untouchability A and B, so the graph represents 40 separate regressions. Points in the graph are the absolute value of the t-statistic on the independent variable of interest practice untouchability , for the two measures of untouchability. The dotted lines are at the t critical value 1.96. The 20 substituted dependent variables, each as reported by the household, are as follows:

Figure 4.

Other outcomes not similarly predicted by local untouchability practice. Observations in this graph are the absolute value of t-statistics on village average practice of untouchability from 40 regressions of the form of equation (1), with each named variable substituted in turn for the dependent variable. A color version of this figure is available online.

| Open defecation | Ideal fertility |

| Always washes hands | Prefers that next child is a boy |

| Woman’s age at marriage | Currently using contraception |

| Took loan in the past 5 years | Unmarried girls harassed in village |

| Owns cell phone | Health belief about milk in pregnancy |

| Does seasonal migration work | Health belief about male sterilization |

| Socially knows a doctor | Health belief about colostrum |

| Socially knows another health worker | Health belief about chulha smoke |

| Member in women’s group | Last birth at home (not institutional) |

| Cooks in a separate kitchen | Last birth exclusively breastfed (6 months) |

As figure 4 shows, conditional on the full set of regression controls, only open defecation is consistently statistically significantly predicted by village practice of untouchability, among these measures of health beliefs and behaviors, modernity, and social conservatism. Belief about the health consequences of smoke from traditional stoves, called chulhas, is associated with untouchability A but in the opposite direction: respondents living in villages where more people report practicing untouchability are more likely to correctly answer that chulha smoke is harmful for health. These results are consistent with a specific cultural association between open defecation and caste-related institutions of purity and pollution.

B. Health Beliefs and the Germ Theory of Disease

Our motivating assumption is that practicing untouchability is a marker for a set of beliefs or preferences that is not merely a marker for modernity, education, or correct knowledge about health. This section presents a series of tests designed to allow the data to falsify these assumptions, which exploit the IHDS’s unique combination of health, economic, and social questions about households’ social networks.

1. Practicing Untouchability Is Associated with Correct Answers to Health Questions

Table 4 tests the hypothesis that people living in villages where more people practice untouchability know less about health issues relevant to life in rural India. The IHDS women’s survey includes questions about health beliefs. For example, the survey asks, “Is it harmful to drink 1–2 glasses of milk every day during pregnancy?” and “Which of the following spreads malaria: contact with sick person, drinking impure water, or mosquitoes?” We constructed a set of indicator variables for correct answers to these questions.

TABLE 4.

VILLAGE PRACTICE OF UNTOUCHABILITY, IF ANYTHING, CORRELATED WITH CORRECT HEALTH BELIEFS

| Correct About |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chulha Smoke | Diarrhea Hydration | Malaria Cause | Milk in Pregnancy | Male Sterilization | Colostrum | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| A. Untouchability A (Direct Household Report) |

||||||

| Village untouchability−i | .0579* | .128** | .187*** | −.0212 | .000190 | .00587 |

| (.0258) | (.0394) | (.0268) | (.0407) | (.0470) | (.0288) | |

| Household untouchability | −.00292 | .00976 | −.0227* | −.00452 | .00160 | .0128 |

| (.0104) | (.0139) | (.0108) | (.0115) | (.0152) | (.00977) | |

| n (female respondents) | 22,811 | 22,817 | 22,811 | 22,057 | 18,207 | 22,814 |

|

|

||||||

| B. Untouchability B (Direct Household Report or Kitchen) | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Village untouchability−i | .0433† | .155*** | .186*** | .0464 | .0442 | −.00458 |

| (.0245) | (.0375) | (.0247) | (.0371) | (.0404) | (.0268) | |

| Household untouchability | −.0117 | .00540 | −.0209* | −.00172 | .0102 | .00592 |

| (.00940) | (.0142) | (.00946) | (.0114) | (.0147) | (.00903) | |

| n (female respondents) | 22,812 | 22,818 | 22,812 | 22,058 | 18,208 | 22,815 |

|

|

||||||

| C. Open Defecation Behavior and Health Beliefs | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Open defecation | .0000237 | −.0221 | −.000944 | .00587 | .0339† | −.0426*** |

| (.0100) | (.0136) | (.00961) | (.0125) | (.0174) | (.00871) | |

| n (female respondent) | 22,924 | 22,930 | 22,924 | 22,167 | 18,291 | 22,927 |

Note. Each column by panel combination is a separate regression. Each dependent variable is an indicator for the adult woman respondent correctly answering the question about that column’s health belief. “Village untouchability−i” is the fraction of households other than the respondent’s that report practicing untouchability in the respondent’s village. “Open defecation” is an indicator at the household level. Each regression includes the most complete set of controls from the main results in table 2: consumption as a cubic polynomial, caste by religion indicators, state fixed effects, and the set of extended controls. Standard errors, clustered by village, are in parentheses.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Panels A and B of table 4 present, separately for each health belief question, results of regressing an indicator for answering the question correctly on our standard measures of the practice of untouchability and on every control variable included in column 6 of table 2. In six of these 12 regressions, the coefficient on village untouchability practice is sufficiently large and precisely estimated to be distinguishable from zero; in each of these cases, the coefficient is positive. Including statistically insignificant results, 10 of the 12 coefficients are positive; there is only a 2% chance of seeing a result this extreme if all coefficients are equally likely to be positive or negative.

These results suggest that village adherence to norms of purity and pollution is, if anything, associated with better health knowledge. In contrast, panel C substitutes an indicator for household open defecation instead of the untouchability variables. Three coefficients are positive and three are negative, with no clear pattern to the results, suggesting that the 2012 level of open defecation is not strongly associated with the health beliefs measured in the IHDS.

2. Practicing Untouchability Is Associated with Social Ties to Doctors

In a section of the IHDS designed to measure social networks, the survey asks, “Do you or any members of your household have personal acquaintance with someone who works in any of the following occupations among your relatives/caste/community?”; “doctors” is among the occupations asked about.22 Table 5 finds that households that practice untouchability are about 2 percentage points more likely to report knowing a doctor. Columns 2–4 verify that this difference is not driven by consumption, by the caste or religion of the respondent as measured by the IHDS, by state differences, or by an omitted correlation with dichotomized Hinduism.23 Thus, this measure also suggests that practicing untouchability is positively associated with some dimensions of greater access to health information.

TABLE 5.

HOUSEHOLD PRACTICE OF UNTOUCHABILITY IS POSITIVELY ASSOCIATED WITH KNOWING DOCTOR

| Dependent Variable: Knows Doctor among Relatives/Caste/Community |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Household practices untouchability | .0172* | .0163* | .0231*** | .0250*** |

| (.0101) | (.00977) | (.00876) | (.00907) | |

| ln(consumption)3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Own caste group × religion | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| State fixed effects | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| n (rural households) | 27,261 | 27,261 | 27,261 | 22,800 |

| Sample | Full | Full | Full | Hindu |

Note. The dependent variable is an indicator for the household respondent answering yes to “Do you or any members of your household have personal acquaintance [with a doctor] among your relatives/caste/community?”; the mean of this variable is 0.167. Untouchability is version B: reported or kitchen. Standard errors, clustered by village, are in parentheses.

p < .10.

p < .01.

3. Controlling for Health Knowledge Does Not Change Our Main Result

Table 6 adds the measures of health beliefs and social relationships with a doctor to our main regression results. Because not every household contained a woman who answered the health belief questions, adding these variables reduces our sample. The health belief questions collectively improve the fit of the model. However, the main coefficients on village average practice of untouchability are numerically almost unchanged by the addition of these controls. Again, there is no evidence here to suggest that the association between open defecation and the norms of untouchability merely reflects general health knowledge or interaction with the germ theory of disease.

TABLE 6.

CONTROLS FOR HEALTH BELIEFS PREDICT SANITATION BUT DO NOT CHANGE MAIN RESULT

| Dependent Variable: Household Open Defecation |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Village untouchability A−i | .0743*** | .0739*** | .0732** | |||

| (.0267) | (.0285) | (.0285) | ||||

| Household untouchability A | −.00276 | −.000502 | .000161 | |||

| (.00961) | (.0107) | (.0107) | ||||

| Village untouchability B−i | .0586** | .0569** | .0565** | |||

| (.0264) | (.0282) | (.0282) | ||||

| Household untouchability B | .00513 | .0119 | .0126 | |||

| (.00942) | (.0106) | (.0106) | ||||

| Health beliefs | F5 = 5.61 | F5 = 5.57 | F−5 = 5.61 | F5 = 5.60 | ||

| p < .0001 | p < .0001 | p < .0001 | p < .0001 | |||

| Doctor social contact | −.0250* | −.0259* | ||||

| (.0140) | (.0141) | |||||

| Other health social contact | .00869 | .00861 | ||||

| (.0143) | (.0143) | |||||

| All controls from table 2 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| n (rural households) | 27,320 | 22,016 | 22,016 | 27,320 | 22,017 | 22,017 |

Note. The dependent variable is an indicator for household open defecation. “Village untouchability−i” is the fraction of households other than the respondent’s that report practicing untouchability in the respondent’s village. “Open defecation” is an indicator at the household level. “Health beliefs” is the set of dependent variables from table 4. “Doctor social contact” and “other health social contact” are indicators for the household reporting knowing somebody in their family, caste, or community, as in table 5. Each regression includes the most complete set of controls from the main results in table 2: consumption as a cubic polynomial, caste by religion indicators, state fixed effects, and the set of extended controls. The regressions in cols. 1 and 4 are identical to those in panels A and B of table 2, col. 6. Standard errors, clustered by village, are in parentheses.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

C. Discussion: Explaining Heterogeneity across Indian States

Our analysis of open defecation in rural India is motivated by the puzzle of exceptionally high open defecation in comparison with other developing countries. However, this paper exploits variation within India in the culture of caste-related purity and pollution across villages in order to suggest that such factors might be part of what explains the internationally unusual level of open defecation in India. There are similar apparent paradoxes within India in comparisons across Indian states. In the sanitation policy sector, much attention is paid to imperfect government implementation of sanitation programs (Spears 2013). Yet states that are generally regarded to be relatively well governed and less poor, such as Gujarat and Tamil Nadu, have rural open defecation rates in the 2011 census of 67.0% and 76.8%, respectively, not far behind the 78.2% and 82.4% of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, poor northern plains states.24 In contrast, the northeastern states—which are poor and marked by governance challenges but are in some ways culturally dissimilar to the large central states of India—have much lower rates of rural open defecation, such as 15.9% in Sikkim, 14.0% in Manipur, and 15.4% in Mizoram. In the IHDS, reported practice of untouchability is 9 percentage points lower, on a base of 24, in the northeastern states than in the rest of India.

If familiar socioeconomic variables cannot explain heterogeneity across Indian states, can the culture of purity and pollution, as measured here by reported practice of untouchability? Table 7 suggests that the answer may be yes. Column 1 shows that state average practice of untouchability can linearly account for 48% of the variation in state average open defecation. In column 2, when a control for literacy rates is added, these two variables can together explain more than 70% of the cross-state variation. Adding a set of controls for economic standard of living in column 3 (average consumption and fraction below the poverty line) does not improve the explanatory power of the model; nor does a set of controls for governance and civil society (fractions with much and with some confidence in politicians, fraction receiving National Rural Employment Guarantee Act work, fraction in a women’s group). The aggregated regressions with controls in columns 5 and 6 may capture the general equilibrium effects of the culture of purity and pollution in India in a way that the household-level regressions of our main results cannot.

TABLE 7.

DISCUSSION: THE PRACTICE OF OPEN DEFECATION AND UNTOUCHABILITY ACROSS INDIAN STATES

| Fraction of Rural Households That Defecate in the Open |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Practice untouchability B | 1.123† | .628*** | .554*** | .549** | |

| (.192) | (.182) | (.197) | (.200) | ||

| Practice untouchability A | .628** | ||||

| (.242) | |||||

| Literacy | −1.717† | −1.778† | −1.718*** | −1.769*** | |

| (.323) | (.376) | (.505) | (.526) | ||

| Poverty | .784 | .982 | 1.055 | ||

| (.674) | (.829) | (.799) | |||

| Average consumption | .169 | .167 | .181 | ||

| (.199) | (.253) | (.254) | |||

| Much confidence in politicians | −.254 | −.262 | |||

| (.416) | (.392) | ||||

| Some confidence in politicians | −.133 | −.119 | |||

| (.226) | (.243) | ||||

| NREGA work | −.186 | −.175 | |||

| (.158) | (.160) | ||||

| In women’s group | .198 | .187 | |||

| (.165) | (.169) | ||||

| Test addition | F2, 27 = .74 | F4, 23 = 1.51 | |||

| p = .49 | p = .23 | ||||

| n (states) | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| R 2 | .480 | .712 | .726 | .768 | .764 |

Note. The dependent variable open defecation and independent variables literacy, poverty, confidence in political leaders, household participation in National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) work, and household participation in a women’s group are all computed as a fraction of rural households in a state. Robust standard errors are in parentheses (data are collapsed to state averages).

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

If so, and if these regressions are not importantly confounded by omitted variables, they may be informative about our motivating questions about India in international comparison. Although the following computation is suggestive and should not be taken quantitatively literally, it may be informative about the potential importance of untouchability to imagine what open defecation in India would look like without the culture of purity and pollution. According to UNICEF and World Health Organization (WHO) Joint Monitoring Program data, 35.2% of rural sub-Saharan Africa defecated in the open in 2012. Presumably, almost nobody in rural sub-Saharan Africa practices Indian untouchability. The predicted amount of open defecation in rural India with untouchability set to zero would be

This would mean that our dichotomized measure of the practice of untouchability could linearly account for 59% of the difference between India and sub-Saharan Africa in open defecation. Given the measurement error in our simple measure of the culture of purity and pollution, this could plausibly be an underestimate of the effect size. Of course, this projection should not be taken at all numerically literally; among other abstractions, it does not account for any other difference between India and sub-Saharan Africa, and it is not the purpose of this paper to estimate a causal effect.

VI. Conclusion

Uniquely widespread and persistent open defecation in rural India has emerged as an important policy challenge and puzzle about behavioral choice in economic development: Why might people who can afford latrines—or who already have them—choose not to use them? One candidate explanation is the culture of purity and pollution that reinforces and has its origins in the caste system. Because we cannot compare open defecation in the India that exists with the open defecation that would exist in a counterfactual India without these culture forces, we study open defecation rates across places in India where untouchability is more and less intensely practiced. We find an association between local practice of untouchability and open defecation that is robust; is not explained by economic, educational, or other observable differences; and is specific to open defecation rather than other health behavior or human capital investments more generally. Practicing untouchability is not associated with general disadvantage in health knowledge or access to medical professionals. We interpret this as consistent with an understanding that the culture of purity, pollution, untouchability, and caste contributes to the exceptional prevalence of open defecation in rural India.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for comments from Radu Ban, Diane Coffey, Barbara Harriss-White, Reeve Vanneman, and discussants and participants at Jawaharlal Nehru University, Water Aid in Delhi, the World Bank in Delhi, the 2015 University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill Water and Health Conference, and the 2016 annual meeting of the Population Association of America.

Appendix A

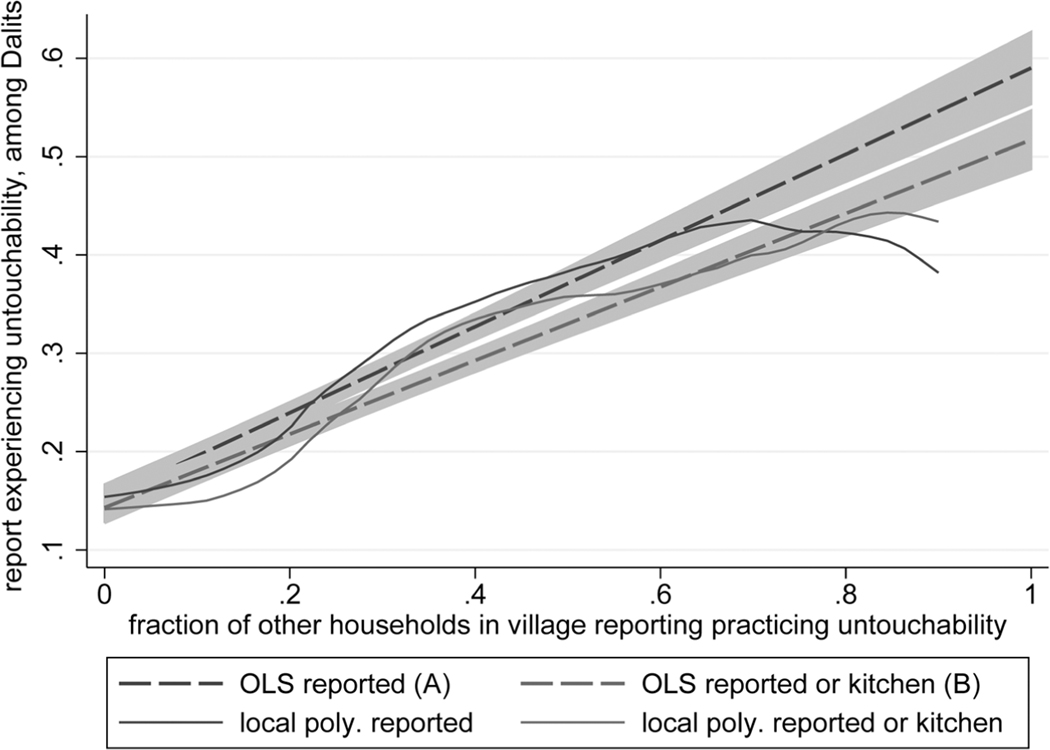

Figure A1.

More Dalits report experiencing untouchability where more of their neighbors report practicing it. Observations in this graph are of rural Dalit households. OLS p ordinary least squares; local poly. p local polynomial regression. A color version of this figure is available online.

Footnotes

For recent evidence of the importance of sanitation in India for health, see an active literature in economics, including Duflo et al. (2015), Gertler et al. (2015), Duh and Spears (2016), and Hammer and Spears (2016); and see Headey (2015) on Ethiopia and Vyas et al. (2016) on Cambodia.

In prior work, Coffey et al. (2016) conduct a related exercise, reviewing further cross-country statistical evidence that open defecation in India cannot be accounted for by poverty, average income, education, or governance, which are all better, on average, in India than in many poorer countries where open defecation is much less common. Kumar, Murgai, and Spears (2015) use international and within-Indian comparisons to show that access to water cannot explain open defecation in rural India, either: internationally, four of every five countries with worse access to water have lower levels of open defecation; within India, almost half of rural households with piped water in the home defecate in the open. If providing water were to cause an increase in rates of latrine use in India (Duflo et al. 2015), it could be because the culture of purity and pollution gives water different significance in India than in these other countries (Routray et al. 2015).

Fricke (2003), writing on “culture and causality” as an anthropologist for an audience of demographers, provides a useful perspective on how cultural explanations can be assessed for their contribution to understanding demographic- and population-level processes. As a complex equilibrium outcome that both influences and is influenced by individual behavior, cultural variation may not always present sharp, exogenous variation. Fricke’s emphasis that culture is a “context of understanding and motivation” (473) is consistent with the demonstration in our main result that it is the local average practice of untouchability—rather than a household’s own practice of untouchability—that predicts household-level open defecation. Fricke argues that culture should be understood as a system of meaning and that a cultural explanation should be assessed by its “coherence” across behavioral domains; thus, we provide evidence that a context of widespread practice of and belief in untouchability coheres with open defecation—which, here, means a reduction of bodily pollution and promotion of the purity of the home.

This hypothesis has received recent support from Routray et al.’s (2015) new qualitative study of villages in a district of Orissa. Patil et al. (2014) write about a field experiment in rural Maharashtra: “A follow-up debriefing question to households who had IHL [a household latrine] identified that the main reasons for daily open defecation in spite of having IHL were culture, habit, or preference for defecating in open followed by inadequate water availability” (8). Barnard et al. (2013) also note a culturally influenced preference for open defecation, even among many latrine owners: “The most common reason reported for not using a latrine was that people prefer open defecation. Open defecation is a cultural practice that is deeply engrained in communities in India” (5). See also Teltumbde (2014) on India’s current sanitation policy.

The rate of open defecation is considerably lower in Bangladesh than in India, despite the fact that Bangladesh is much poorer. UNICEFand the WHO estimate that in 2015, 1.8% of rural Bangladeshis defecated in the open. In contrast, our main data sources find that 64% of Indian households report open defecation. In the Guiteras et al. (2015) study, 78% of the control group reports having access to a toilet or latrine at baseline, compared with 69.3% of rural Indian households having no toilet or latrine in the 2011 Indian census.

These numerous kinship groups are socially divided into four broad hierarchical and hereditary groups, with Brahmins (priests) ranked at the top, followed by Kshatriyas (warriors), Vaishyas (traders), and Shudras (workers and farmers) at the bottom. These four groups form the savarnas, meaning those who can be ranked according to Hindu religious law. Such rules also define the precise social and economic rights and duties for each of these groups. Although some writers claim that caste is no longer relevant in today’s India, there is considerable evidence that, although some implications of caste are changing, caste-based discrimination remains. For example, Deshpande and Spears (2016) document caste-based discrimination among urban, English-speaking internet users.

The purifying nature of cow urine is a striking example of the fact that the cultural category of pure versus polluting does not map onto the germ theory of disease. Cow urine and feces are among the most purifying substances; newborn babies and their mothers are polluting even for days after the physical residue of the birth has been cleaned.

Although our paper focuses on rural India, these norms tend to have been modified in urban India, where there is no similar space for open defecation in fields or for construction of latrines away from the home. Untouchability nevertheless persists in urban India: many Dalits are unable to find work outside of garbage disposal, street cleaning, and maintenance of sewers and toilets.

For statistical evidence of an interaction of the caste of local government officials, assigned by random reservation, with outcomes of the Indian government’s rural sanitation program, see Lamba and Spears (2013).

This IHDS is a panel that reinterviewed the same households in 2005 and 2012. However, our analysis largely ignores the 2005 survey because that survey round did not ask about the practice of untouchability. The last Demographic and Health Survey in India was conducted in 2005; therefore, the IHDS offers the most recent nationally representative survey data on open defecation in India.

This will also overlook people who use a latrine that their household does not own, but this is considerably more rare: Coffey et al. (2014) find that only 3% of people in rural India usually use a toilet or latrine in households that do not own one.

There is caste rank among Dalits, and many Dalits practice untouchability toward other Dalits to demonstrate higher rank.

Note that, although we have an average as an independent variable, our paper does not suffer from the well-known pitfalls of estimating peer effects (Angrist 2014) for the simple reason that our paper does not estimate a peer effect, the term in the econometric literature for the effect of average peer behavior on an individual’s behavior on that same variable. We are not estimating the effect of local average practice of untouchability on own practice of untouchability—indeed, we include own practice of untouchability as a control.

For the independent variable, the belief in caste-oriented norms of purity and pollution and the practice of untouchability both take many forms and degrees. For the dependent variable, open defecation is an individual-level behavior, which varies within households across people and with seasons and other occasions (Coffey et al. 2014).

We take no position on whether people can simultaneously hold beliefs compatible with the germ theory of disease and with the Hindu theory of the body; our point here is only to verify that our measure of the practice of untouchability is not merely a marker for failure to believe in the germ theory of disease.

Figure B2 (figs. B1, B2 are available online) presents histograms of villages’ average reported practice of untouchability. There is support throughout the distribution, with a large mass at 0.

Average annual consumption per person is computed as . Adjusting for purchasing power parity would make this number larger. Such a household with five people could afford the expensive r 12,000 latrines that the Indian government purchases by reducing 1 year’s consumption by 3.5% or the average-price latrine that Cameron, Shah, and Olivia (2013) document as being in use in Indonesia by reducing 1 year’s consumption by 1.3%. Of course, households could also smooth the cost of such a durable asset over multiple years.

A household’s own practice of untouchability and the PSU average do not statistically (or in coefficient magnitude) significantly interact to predict a household’s open defecation, as is shown in fig. B1.

If the village practice of untouchability is interacted with an indicator for the household being Dalit—the socially lowest-ranking castes—we find that the gradient on village untouchability is less steep among these households that benefit the least from the caste system of purity and pollution (inter-action coefficient = −0:08, two-sided p = :08, in a regression specification otherwise identical to table 2, col. 3).

Duflo et al. (2015) have recently proposed that access to water may encourage latrine use in rural Orissa; this may be true there, where access to improved water is 9 percentage points lower, in our data, than in the average for the rest of India. If an indicator for access to improved water (piped water or an improved well or pump) is added to the fully controlled specification for all India in col. 6, the coefficient on local untouchability remains the same (moving from 0.074 to 0.068, with a new two-sided p-value of .010), but the coefficient on access to improved water is not statistically significantly different from zero; in fact, it is slightly positively associated with being more likely to defecate in the open.

These controls are important: places with more casteism are also places that are poorer on average, which could in part be due to economic effects of the disease environment (Lawson and Spears 2016) or of social fragmentation and casteism more broadly (Anderson 2011).

The “socially knows a doctor” variable in falsification fig. 4 is an indicator for knowing a doctor in your relative, caste, or community group or otherwise.

However, the IHDS’s indicator for being Brahmin is coarse relative to the many subdivisions of caste, and within this and other IHDS categories, further caste privilege may be residually correlated with educational or other social advantage.

In fact, the census measured household latrine ownership, not the behavior of open defecation or latrine use.

Contributor Information

DEAN SPEARS, Economics and Planning Unit, Indian Statistical Institute, Delhi; and University of Texas at Austin.

AMIT THORAT, Centre for the Study of Regional Development, Jawaharlal Nehru University.

References

- Aktor Mikael. 2002. “Rules of Untouchability in Ancient and Medieval Law Books: Householders, Competence, and Inauspiciousness.” International Journal of Hindu Studies 6, no. 3:243–74. [Google Scholar]

- Alter Joseph S. 2004. Yoga in Modern India: The Body between Science and Philosophy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson Siwan. 2011. “Caste as an Impediment to Trade.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 3, no. 1:239–63. [Google Scholar]

- Angrist Joshua D. 2014. “The Perils of Peer Effects.” Labour Economics 30:98–108. [Google Scholar]

- Angrist Joshua D., and Pischke Jorn-Steffen. 2010. “The Credibility Revolution in Empirical Economics: How Better Research Design Is Taking the Con out of Econometrics.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 24, no. 2:3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Barnard Sharmani, Routray Parimita, Majorin Fiona, Peletz Rachel, Boisson Sophie, Sinha Antara, and Clasen Thomas. 2013. “Impact of Indian Total Sanitation Campaign on Latrine Coverage and Use: A Cross-Sectional Study in Orissa Three Years Following Programme Implementation.” PLoS ONE, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalotra Sonia, Valente Christine, and Van Soest Arthur. 2010. “The Puzzle of Muslim Advantage in Child Survival in India.” Journal of Health Economics 29, no. 2:191–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron Lisa, Shah Manisha, and Olivia Susan. 2013. “Impact Evaluation of a Large-Scale Rural Sanitation Project in Indonesia.” Policy Research Working Paper no. 6360, World Bank, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Clasen Thomas, Boisson Sophie, Routray Parimita, Torondel Belen, Bell Melissa, Cumming Oliver, Ensink Jeroen, et al. 2014. “Effectiveness of a Rural Sanitation Programme on Diarrhoea, Soil-Transmitted Helminth Infection, and Child Malnutrition in Odisha, India: A Cluster-Randomised Trial.” Lancet Global Health 2, no. 11:e645–e653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey Diane, Gupta Aashish, Hathi Payal, Khurana Nidhi, Spears Dean, Srivastav Nikhil, and Vyas Sangita. 2014. “Revealed Preference for Open Defecation.” Economic and Political Weekly 49, no. 38:43. [Google Scholar]

- Coffey Diane, Gupta Aashish, Hathi Payal, Spears Dean, Srivastav Nikhil, and Vyas Sangita. 2016. “Understanding Open Defecation in Rural India: Untouchability, Pollution, and Latrine Pits.” Economic and Political Weekly 52, no. 1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey Diane, and Spears Dean. 2014. “How Can a Large Sample Survey Monitor Open Defecation in Rural India for the Swatch Bharat Abhiyan?” Working paper, r.i.c.e. [Google Scholar]

- Currie Janet, and Vogl Tom. 2013. “Early-Life Health and Adult Circumstance in Developing Countries.” Annual Review of Economics 5, no. 1:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler David, Fung Winnie, Kremer Michael, Singhal Monica, and Vogl Tom. 2010. “Early-Life Malaria Exposure and Adult Outcomes: Evidence from Malaria Eradication in India.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 2:72–94. [Google Scholar]

- Desai Sonalde, Dubey Amaresh, and Vanneman Reeve. 2005. “India Human Development Survey–II.” Computer file. University of Maryland and National Council of Applied Economic Research, New Delhi. [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande Ashwini. 2011. The Grammar of Caste: Economic Discrimination in Contemporary India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande Ashwini, and Spears Dean. 2016. “Who Is the Identifiable Victim? Caste and Charitable Giving in Modern India.” Economic Development and Cultural Change 64, no. 2:299–321. [Google Scholar]

- Duflo Esther, Greenstone Michael, Guiteras Raymond, and Clasen Thomas. 2015. “Toilets Can Work: Short and Medium Run Health Impacts of Addressing Complementarities and Externalities in Water and Sanitation.” NBER Working Paper no. 21521, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Duh Josephine, and Spears Dean. 2016. “Health and Hunger: Disease, Energy Needs, and the Indian Calorie Consumption Puzzle.” Economic Journal 127, no. 606:2378–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricke Tom. 2003. “Culture and Causality: An Anthropological Comment.” Population and Development Review 29, no. 3:470–79. [Google Scholar]

- Gertler Paul, Shah Manisha, Alzua Maria Laurz, Cameron Lisa, Martinez Sebastian, and Patil Sumeet. 2015. “How Does Health Promotion Work? Evidence from the Dirty Business of Eliminating Open Defecation.” NBER Working Paper no. 20997, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Geruso Michael, and Spears Dean. 2015. “Neighborhood Sanitation and Infant Mortality.” NBER Working Paper no. 21184, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiteras Raymond, Levinsohn James, and Mobarak Ahmed Mushfiq. 2015. “Encouraging Sanitation Investment in the Developing World: A Cluster-Randomized Trial.” Science 348, no. 6237:903–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer Jeffrey, and Spears Dean. 2016. “Village Sanitation and Child Health: Effects and External Validity in a Randomized Field Experiment in Rural India.” Journal of Health Economics 48:135–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna Rema N., and Linden Leigh L.. 2012. “Discrimination in Grading.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 4, no. 4:146–68. [Google Scholar]

- Headey Derek D. 2015. “The Nutritional Impacts of Sanitation at Scale: Ethiopia, 2000–2011.” IFPRI Working Paper, International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Hnatkovska Viktoria, Lahiri Amartya, and Paul Sourabh. 2012. “Castes and Labor Mobility.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 4, no. 2:274–307. [Google Scholar]

- Kijima Yoko. 2006. “Caste and Tribe Inequality: Evidence from India, 1983–1999.” Economic Development and Cultural Change 54, no. 2:369–404. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar Manish, Murgai Rinku, and Spears Dean. 2015. “Access to Water Does Not Explain Exceptionally Common Open Defecation in India.” Working Paper, World Bank, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Lamba Sneha, and Spears Dean. 2013. “Caste, ‘Cleanliness’ and Cash: Effects of Caste-Based Political Reservations in Rajasthan on a Sanitation Prize.” Journal of Development Studies 49, no. 11:1592–606. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson Nicholas, and Spears Dean. 2016. “What Doesn’t Kill You Makes You Poorer: Adult Wages and Early-Life Mortality in India.” Economics and Human Biology 21:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil Sumeet R., Arnold Benjamin F., Salvatore Alicia L., Briceno Bertha, Ganguly Sandipan, Colford John M. Jr., and Gertler Paul J.. 2014. “The Effect of India’s Total Sanitation Campaign on Defecation Behaviors and Child Health in Rural Madhya Pradesh: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial.” PLoS Medicine 11, no. 8:e1001709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Routray Parimita, Schmidt Wolf-Peter, Boisson Sophie, Clasen Thomas, and Jenkins Marion W.. 2015. “Socio-Cultural and Behavioural Factors Constraining Latrine Adoption in Rural Coastal Odisha: An Exploratory Qualitative Study.” BMC Public Health 15, no. 1:880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spears Dean. 2013. “Policy Lessons from Implementing India’s Total Sanitation Campaign.” India Policy Forum, National Council of Applied Economic Research 9, no. 1:63–104. [Google Scholar]