Abstract

Background

Poor oral hygiene affects the overall health and quality of life. However, the oral hygiene practice in rural communities and contributing factors are not well documented. Accordingly, this study was conducted to assess oral hygiene practices and associated factors among rural communities in northwest Ethiopia.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted among 1190 households. Data were collected using a structured and pretested questionnaire, prepared based on a review of relevant literature. The questionnaire comprises socio-demographic information, access to health and hygiene messages, oral hygiene practices, and water quality. We assessed oral hygiene practices with these criteria: mouth wash with clean water in every morning, mouth wash with clean water after eating, brushing teeth regularly, and avoiding gum pricking. Gum pricking in this study is defined as sticking needles or wires into gums to make the gums black for beauty. Multivariable logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with oral hygiene practices. Significant associations were declared on the basis of adjusted odds ratio with 95% confidence interval and p-values < 0.05.

Results

Results showed that all the family members usually washed their mouth with clean water in everyday morning and after eating in 65.2% and 49.6% of the households, respectively. Furthermore, 29.9% of the households reported that all the family members regularly brushed their teeth using toothbrush sticks and one or more of the family members in 14.5% of the households had gum pricking. Overall, 42.9% (95% CI: 39.9, 45.6%) of the households had good oral hygiene practices. Health and/or hygiene education was associated with good oral hygiene practices in the area (AOR: 1.66, 95% CI: 1.26, 2.21).

Conclusion

More than half of the households had poor oral hygiene practices in the area and cleaning of teeth with toothpastes is not practiced in the area, where as gum pricking is practiced in more than one-tenth of the households. The local health department needs provide community-level oral health education/interventions, such as washing mouth with clean water at least twice a day, teeth brushing using indigenous methods such as toothbrush sticks or modern methods such as toothpastes, and avoiding gum pricking to promote oral health.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12903-024-04049-4.

Keywords: Oral health, Oral hygiene, Mouthwash, Teeth cleaning, Toothbrush sticks, Gum pricking, Rural communities, Ethiopia

Background

Oral health is a critical component of overall body health and an important factor in an individual’s overall well-being. A healthy mouth with a disease-free oral cavity and its surrounding structures constitutes good oral health. Like other areas of the body, mouth teems with bacteria, mostly harmless. But mouth is the entry point to digestive and respiratory tracts, and some of these bacteria can cause disease. Normally the body’s natural defenses and good oral hygiene, such as daily brushing and flossing, keep bacteria under control [1–3].

However, without proper oral hygiene, bacteria can reach levels that might lead to oral infections, such as tooth decay and gum disease [4, 5]. Oral diseases are estimated to affect nearly 3.5 billion people at global level [6] and the 2019 global disease burden estimate showed that about 2 billion people worldwide suffer from permanent tooth caries, with 520 million children suffering from primary tooth caries and approximately 14% of the global adult population, representing to more than one billion cases worldwide are affected by periodontal diseases [6]. Moreover, oral diseases have also significant economic consequences, which include direct, indirect, and intangible costs such as treatment costs, missed school and work days, and decreased quality of life [7]. For instance, dental diseases (excluding oral and pharyngeal cancers) costed approximately $545 billion US dollar in 2015 [8].

Maintaining oral hygiene at good condition is an important day-to-day activity to prevent poor oral hygiene associated health problems. Indigenous and modern methods are available to maintain oral health. The use of traditional means of oral hygiene such as plant-based traditional toothbrush sticks has been used to maintain oral hygiene good and to treat oral diseases as documented in literature [9–12]. The use of toothbrush sticks (in many cases also known as chewing sticks) is widespread in Ethiopia, both for esthetic and hygienic purposes. In Ethiopia, a chewing stick, generally called the “mefakia’’. The use of toothbrush sticks to maintain oral hygiene is also recommended by world health organization [13]. A toothbrush stick is generally obtained from any slim woody part of trees. Mostly it is harvested from branches although harvest from woody roots is also known. Some of the common plants used for toothbrush sticks in Ethiopia are Akeya (Salix subserrata), Weira (Olea africana), Kacha (Agave sisolana), Kechemo (Myrsine africana), Zembaba (Phoenix reclinata), Chifrig (Sida cunefolia), and Limitch (Clausena anisata) [13]. Toothbrush sticks contain an antiseptic property and have no plaque deposits and toxicity [14–16]. Moreover, tooth brushing using toothpastes, flossing, and other healthy lifestyle measures such as minimizing tobacco use and sugary intake are the most recommended measures to maintain oral health. Teeth brushing twice a day using toothpastes (one in the morning and second before going to sleep at the night) is the primary way to maintain good oral hygiene. Fluoride, a common ingredient in toothpaste helps prevent cavities. Moreover, the antiseptic nature of toothpastes can limit growth of microbes and the mechanical action of brushing helps to remove solid particles [17–19]. However, brushing does not remove all the solid particles from teeth. Therefore, flossing with thorough rinsing by clean water plays an important role in removing all the small particles from the teeth [20–22]. Health lifestyles such as avoiding or minimizing tobacco use, soda drinks, and sugary intakes play a remarkable contribution to keep the oral cavity healthy. Tobacco intake increases the plaque level in the teeth and weakens the teeth [23–25]. Soda drinks cause teeth damage [26–28].

Despite indigenous and modern methods are available to maintain oral health, significant oral health disparities exist in rural communities, especially in developing countries. These disparities result from a number of factors including low priority to oral health, geographic isolation, cultural norms, poverty, oral health illiteracy, and other contextual factors such as deficient infrastructures, underprovided public services and unequal distribution of health services [29–32]. However, oral hygiene practices and contextual factors in the rural northwest Ethiopia is not documented and there is still minimal research on the oral health of rural populations in the area. This study was, therefore, conducted to assess oral hygiene practices and associated factors among rural communities in northwest Ethiopia.

Methods

Study design and setting

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted among rural households in central and north Gondar administrative zones of the Amhara national regional state, Ethiopia in May 2016. North Gondar zone covers seven woredas and is bordered on the south by central Gondar zone, on the north by the Tigray region, and on the east by Wag Hemra zone. Debarq town is the capital city of the zone [33]. The total population in north Gondar zone is estimated to be 912,112 [34]. Central Gondar zone covers thirteen woredas and is bordered on the south by Lake Tana, west Gojjam zone, Agew Awi zone and the Benishangul-Gumuz region, on the west by west Gondar zone, on the north by the Tigray region and north Gondar zone, on the east by Wag Hemra zone and on the southeast by south Gondar zone [35]. Gondar city is the capital city of central Gondar zone. The total population in central Gondar zone is estimated to be 2,896,928 [34].

Sample size calculation and sampling procedures

The sample size was calculated using simple population proportion formula with the following assumptions: proportion of rural households who had good oral hygiene (p) = 50% since there was no similar study in the area, level of significance (α) = 5%, 95% confidence interval (standard normal probability), z: the standard normal tabulated value, and margin of error (d) = 5%.

|

The final sample size was 1210, with a design effect of 3 and a non-response rate of 5%. All rural households in central and north Gondar administrative zones were considered for sampling. First, we chose 4 districts or woredas out of 22 using lottery method and we then selected 7 kebeles (the lowest administrative unit in Ethiopia) from each district at random using a simple random sampling technique, that is, the lottery method. Finally, we selected 1210 rural households (the analysis unit of this study) using a systematic random sampling technique. Forty-three households were included in each kebele (the number of households in each kebele was determined by equally devising the total sample size to each kebele). We began collecting data in households located on the right side of the local administrators’ office. Assuming that the average number of households in each rural kebele is 200 [36, 37], a sampling interval (K = 5) was calculated by dividing 200 by the kebele’s predetermined sample size (n = 43). Following that, a number between one and the sampling interval was chosen at random using the lottery method, which is known as the random start, and was used as the first number included in the sample. Then, after the first random start, every fifth household was sampled until the desired sample size for each kebele was reached.

Data collection tools and procedures

A structured and pretested questionnaire was used to collect data, prepared based on a review of relevant literature [38, 39]. The questionnaire was first prepared in English language and translated to the local Amharic language, and back translated into English to check consistency. The questionnaire comprises socio-demographic information, access to health and sanitation messages, oral hygiene practices, and water quality (Supplementary file 1). Environmental health experts were participated in the data collection process. We provided training for the data collectors, provided them with a guide for the questionnaire, and field supervisors closely supervised the data collection process and checked completeness of data in each day of data collection to improve inter and intra interviewers’ reliability during the interview. The training was about each item in the questionnaire, interview techniques, and ethical issues during interview.

Measurement of outcome variable

Oral hygiene practices of households, the primary outcome variable of the study, was taken as “good” if all the family members wash their mouth with clean water in everyday morning after getting from bed, wash/rinse their mouth with clean water after eating, regularly brush or clean their teeth with toothbrush sticks, and if the family members have no traditional gum pricking. Gum pricking in the current study is sticking needles or wires into gums to make the gums black for beauty.

Data processing and analysis

Data were entered into EPI-INFO version 3.5.3 and exported to Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20 for further analysis. For most variables, data were presented by frequency and percentage. We included variables to the multivariable binary logistic regression model from the literature regardless of their bivariate p-value to identify factors associated with oral hygiene practices of rural households. Statistically significant association was declared on the basis of adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-values < 0.05. Model fitness was check using Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test.

Results

Characteristics of study households

Of a total of 1210 rural households, 1190 households participated in the current study, with a response rate of 98.3%. The mean ( SD) family size was 5 (

SD) family size was 5 ( 2) and 513 (43.1%) of the households had family size more than the mean. Two hundred and ninety-two (24.7%) and 442 (40.7%) of the female and male household heads, respectively attended formal education. Rural households accessed hygiene and sanitation messages via health education [565 (47.5%)], health supervision [967 (81.3%)], and family discussion [812 (68.2%)]. Almost all, 1154 (97%) of the households had no basic access to drinking water, i.e., 20 l/c/d (Table 1).

2) and 513 (43.1%) of the households had family size more than the mean. Two hundred and ninety-two (24.7%) and 442 (40.7%) of the female and male household heads, respectively attended formal education. Rural households accessed hygiene and sanitation messages via health education [565 (47.5%)], health supervision [967 (81.3%)], and family discussion [812 (68.2%)]. Almost all, 1154 (97%) of the households had no basic access to drinking water, i.e., 20 l/c/d (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study households (n = 1190) in a rural setting of northwest Ethiopia, May 2016

| Variables | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Family size | ||

5 5 |

677 | 56.9 |

5 5 |

513 | 43.1 |

| Maternal education (n = 1180) | ||

| No formal education | 888 | 75.3 |

| Attend formal education* | 292 | 24.7 |

| Paternal education (n = 1085) | ||

| No formal education | 643 | 59.3 |

| Attend formal education* | 442 | 40.7 |

| The household receive health and hygiene education in the last three months | ||

| Yes | 565 | 47.5 |

| No | 625 | 52.5 |

| Health extension workers regularly supervise health and hygiene conditions of the household | ||

| Yes | 967 | 81.3 |

| No | 223 | 18.7 |

| The family regularly discusses about health issues including oral hygiene | ||

| Yes | 812 | 68.2 |

| No | 378 | 31.8 |

| Volume of water collected per day | ||

20 l/c/d 20 l/c/d |

1154 | 97.0 |

20 l/c/d 20 l/c/d |

36 | 3.0 |

l/c/d: Liter per capita per day

*formal education includes primary and secondary education.

Oral hygiene practices

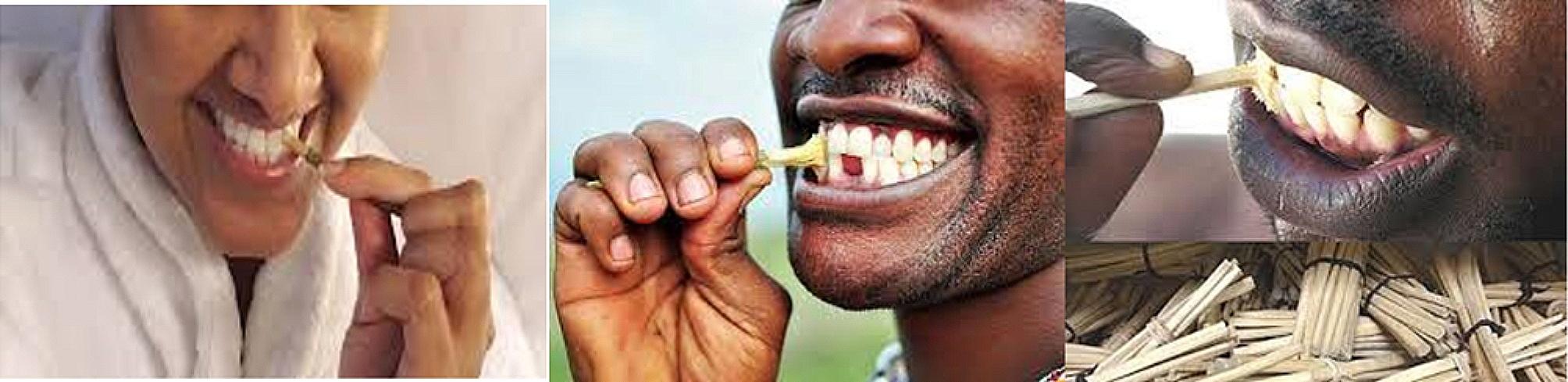

About two-third, 776 (65.2%) of the households reported that all the family members usually washed their mouth with clean water in everyday morning and 590 (49.6%) of the households reported that all the family members usually washed their mouth with clean water after eating. Furthermore, 356 (29.9%) of the households reported that all the family members regularly scrub their teeth using toothbrush sticks. Figure 1 illustrates the use of toothbrush sticks in the studied region. One hundred and seventy-three (14.5%) of the households reported that one or more family members had gum pricking. Overall, 510 (42.9%) (95% CI: 39.9, 45.6%) of the households had good oral hygiene practices (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Photos showing the use of toothbrush sticks to brush teeth.

(source: free google images)

Table 2.

Oral hygiene practices among households (n = 1190) in a rural setting of northwest Ethiopia, May 2016

| Variables | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| All the family members wash their mouth with clean water in everyday morning | ||

| Yes | 776 | 65.2 |

| No | 414 | 34.8 |

| All the family members wash their mouth with clean water after eating | ||

| Yes | 590 | 49.6 |

| No | 600 | 50.4 |

| Do all the family members scrub their teeth using toothbrush sticks | ||

| Yes | 356 | 29.9 |

| No | 834 | 70.1 |

| Traditional gum pricking | ||

| Yes | 173 | 14.5 |

| No | 1017 | 85.5 |

| Oral hygiene | ||

| Poor hygiene | 680 | 57.1 |

| Good hygiene | 510 | 42.9 |

Factors associated with oral hygiene

Health and/or hygiene education, health supervision by community health workers, family discussion about hygiene and sanitation, volume of water collected per day, maternal education, paternal education, and family size were all the variables entered into the multivariable binary logistic regression model regardless of their p-values in the bivariate analysis. In the adjusted model, only health and/or hygiene education was statistically associated with oral hygiene practices of rural households. Households who received health and/or hygiene education in the last three months prior to the survey had 1.66 times more odds to have good oral hygiene practices compared with households who didn’t receive health and/or hygiene education (AOR: 1.66, 95% CI: 1.26, 2.21) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors associated with oral hygiene practices among households (n = 1190) in a rural setting of northwest Ethiopia, May 2016

| Variables | Oral hygiene | COR with 95% CI | AOR with 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good | Poor | |||

| The household receive health and hygiene education in the last three months | ||||

| Yes | 272 | 293 | 1.51 (1.20, 1.90) | 1.66 (1.26, 2.21)*** |

| No | 238 | 387 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Health extension workers regularly supervise health and hygiene conditions of the household | ||||

| Yes | 411 | 556 | 0.93 (0.69, 1.24) | 0.76 (0.53, 1.09) |

| No | 99 | 124 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| The family regularly discusses about health issues including oral hygiene | ||||

| Yes | 360 | 452 | 1.21 (0.94, 1.55) | 1.09 (0.80, 1.49) |

| No | 150 | 228 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Maternal education | ||||

| No formal education | 371 | 517 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Attend formal education | 134 | 158 | 1.18 (0.91, 1.54) | 1.27 (0.94, 1.72) |

| Paternal education | ||||

| No formal education | 272 | 371 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Attend formal education | 189 | 253 | 1.02 (0.80, 1.30) | 0.91 (0.69, 1.19) |

| Family size | ||||

5 5 |

286 | 391 | 0.94 (0.75, 1.19) | 0.89 (0.69, 1.14) |

5 5 |

224 | 289 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Volume of water collected per day | ||||

20 l/c/d 20 l/c/d |

497 | 657 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

20 l/c/d 20 l/c/d |

13 | 23 | 0.75 (0.38, 1.49) | 0.85 (0.38, 1.91) |

Note: *** statistically significant at p < 0.001, Hosmer and Lemeshow test = 0.982, AOR: Adjusted odds ratio, CI: Confidence interval, COR: Crude odds ratio

Discussion

This is a community-based cross-sectional study conducted to assess oral hygiene practices of rural households in northwest Ethiopia and found that 42.9% (95% CI: 39.9, 45.6%) of the households had good oral hygiene practices. This finding is comparable with findings of studies among rural populations in India, 42% [1]. On the other hand, the good-level practice of oral hygiene in the current study is lower than the good-level practice of oral hygiene reported by studies among rural dwellers in Delta and Edo State of Nigeria, 66.2% [40], a rural areas of Kachchh district of India, 81% [41], rural villages of 23 states of India 83% [42], and Dehradun district of India 50% [43]. The lower level of oral hygiene practices in the studied region can be explained by lower oral health literacy. Poor health literacy can result in poor oral hygiene and difficulty in using different oral health measures. Rural residents with low health literacy are more likely to practice bad habits that affect oral health such as pricking and tobacco use. Moreover, extreme poverty in the area may explain poor oral hygiene. In poverty, survival may naturally take precedence over oral hygiene. Hygiene promotion may not be immediate enough for attention beyond pressing needs, for example, the need for food and the means to produce it. In addition, oral health is considered as a much lesser priority in Ethiopia, especially in the rural areas. Due to limited resources available to the health sector, assignments are mainly directed towards life threatening health conditions rather than oral hygiene.

Oral health is fundamental to overall health. The health of our mouth, teeth, and gums can affect our general health [44, 45]. Our oral health might contribute to various diseases and conditions, including endocarditis (this infection of the inner lining of your heart chambers or valves typically occurs when bacteria or other germs from another part of our body, such as from mouth, spread through our bloodstream and attach to certain areas in our heart) [46, 47], cardiovascular disease (heart disease, clogged arteries, and stroke might be linked to the inflammation and infections that oral bacteria can cause) [48, 49], diabetes and pancreatic cancer (gum disease causes inflammation, which makes it harder for your body to use insulin properly. Gum disease can also contribute to certain types of cancer, especially pancreatic cancer) [50–52], pregnancy and birth complications (periodontitis has been linked to premature birth and low birth weight) [53, 54], and pneumonia (certain bacteria in our mouth can be pulled into our lungs, causing pneumonia and other respiratory diseases) [55, 56]. Therefore, practicing good oral hygiene offers advantages that go beyond cavity prevention. Some of the benefits of good oral hygiene include healthier gums, reduced risk for heart attack, healthier lungs, lower chances of diabetes, decreased cancer risk, and safer pregnancy.

While it is common in industrialized countries to use factory made toothbrushes, most of the rural populations in Ethiopia use toothbrush sticks to maintain oral hygiene. Toothbrush sticks can be used by the vast majority of people in Ethiopia who cannot afford to buy the commercial toothbrush and toothpaste. The cleansing efficacy of traditional toothbrush sticks is achieved by the mechanical effects of the stick fibers, antimicrobial constituents of the trees, and a combination of mechanical and chemical actions [57]. However, some toothbrush sticks may have some negative side effects such as teeth discoloration if used for an extended period of time. The rough fibers may also have undesirable effect of scratching the teeth enamel and worse bleeding the gums to allowing bacteria in [14].

This study also explored that health and/or hygiene education was significantly associated with oral hygiene practices in the studied region. Households who received health and/or hygiene education in the last three months prior to the survey had more odds to have good oral hygiene practices. This could be due to the fact that health and/or hygiene education encourages changes in healthy behaviors. Moreover, health and/or hygiene education is an effective strategy to create demand for self-care and thereby increase practices of good oral health measures. Health and/or hygiene education disseminates health information and vital skills necessary to adopt practices and maintain health-enhancing behaviors. Health and/or hygiene education also enables people to take actions to improve their health [5, 58–60].

To our knowledge, no studies have assessed oral hygiene practices and associated factors among rural communities in Ethiopia. The study used structured and pretested data collection and the data collection was closely supervised to increase quality of data and completeness of the questionnaire. Moreover, study subjects were selected at random using systematic random sampling technique and so that all the rural households in the study area had an equal chance to be included in the study and findings of this study will be generalizable. The results of this study could be, therefore, useful in the development of programs for oral health promotion for rural residents and in the development of collaborative rural research activities in the field of oral health. However, the self-reported data may not be reliable to measure oral hygiene since the study subjects may make the more socially acceptable answer rather than being truthful and they may not be able to assess themselves accurately. Moreover, we did not adjust for psychological or behavioral factors which are linked to oral hygiene practice [61, 62].

Conclusion

In the study area, 42.9% of the households had good oral hygiene practices and more than half of the households had poor oral hygiene practices. Cleaning of teeth with toothpastes is not practiced in the area and one or more of the family members in more than one-tenth of the households practiced gum pricking. Health and/or hygiene education was found to be significantly associated with oral hygiene in the studied region. The local health department needs provide community-level oral health education to promote oral hygiene in the community and encouraging the community to use different interventions such as washing mouth with clean water at least twice a day, teeth brushing using indigenous methods such as toothbrush sticks or modern methods such as toothpastes and avoiding gum pricking to promote oral health.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors are pleased to acknowledge study participants, data collectors, and field supervisors. Authors also acknowledged the University of Gondar for funding the field work and questionnaire duplication.

Abbreviations

- AOR

Adjusted odds ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

- COR

Crude odds ratio

- l/c/d

Liter per capita per day

- SD

Standard deviation

- SPSS

Statistical package for social sciences

Author contributions

The study was designed by ZG. NGD, MG, BDB, and AN participated during data collection, data processing and coding, and analysis and interpretation of findings. ZG prepared the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The research project was funded by the University of Gondar (grand number: R/T/T/C/Eng./250/08/2016).

Data availability

Data will be made available upon requesting ZG, the primary author of this study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the University of Gondar (reference number: V/P/RCS/05/1520/2016). There were no risks due to participation and the collected data were used only for this research purpose with complete confidentiality. Written informed consent was obtained from household heads. All the methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

This manuscript does not contain any individual person’s data.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Premnath K, Bharti Wasan D, Tusharbhai DM, Nabeel Althaf M, Bhowmick S, Tiwari RVC, Tiwari H. A cross-sectional study on oral hygiene status among rural population. 2019.

- 2.Lindenmüller IH, Lambrecht JT. Oral care. Topical Appl Mucosa. 2011;40:107–15. doi: 10.1159/000321060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panagakos FS, Migliorati CA. Concepts of oral hygiene maintenance that would apply for the different groups of patients. Diagnosis and management of oral lesions and conditions: a resource handbook for the Clinician. edn.: IntechOpen; 2014.

- 4.Lingström P, Mattsson CS. Oral conditions. Impact Nutr Diet Oral Health. 2020;28:14–21. doi: 10.1159/000455367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petersen PE, The World Oral Health Report. 2003: continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century–the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dentistry and oral epidemiology 2003, 31:3–24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. (GBD 2019). Seattle: Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME); 2020. Available at http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool. Accessed on 23 October 2022.

- 7.Listl S, Galloway J, Mossey P, Marcenes W. Global economic impact of dental diseases. J Dent Res. 2015;94(10):1355–61. doi: 10.1177/0022034515602879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Righolt A, Jevdjevic M, Marcenes W, Listl S. Global-, regional-, and country-level economic impacts of dental diseases in 2015. J Dent Res. 2018;97(5):501–7. doi: 10.1177/0022034517750572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta P, Shetty H. Use of natural products for oral hygiene maintenance: revisiting traditional medicine. J Complement Integr Med 2018, 15(3). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Bairwa R, Gupta P, Gupta VK, Srivastava B. Traditional medicinal plants: use in oral hygiene. Int J Pharm Chem Sci. 2012;1(4):1529–38. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jevtić M, Pantelinac J, Jovanović-Ilić T, Petrović V, Grgić O, Blažić L. The role of nutrition in caries prevention and maintenance of oral health during pregnancy. Medicinski Pregled. 2015;68(11–12):387–93. doi: 10.2298/MPNS1512387J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar R, Mirza MA, Naseef PP, Kuruniyan MS, Zakir F, Aggarwal G. Exploring the potential of natural product-based nanomedicine for maintaining oral health. Molecules. 2022;27(5):1725. doi: 10.3390/molecules27051725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization . Prevention of oral diseases. WHO offset publication No. 103. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1987. p. 61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Araya YN. Contribution of trees for oral hygiene in East Africa. Ethnobotanical Leaflets. 2007;2007(1):8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Vuuren S, Viljoen A. The in vitro antimicrobial activity of toothbrush sticks used in Ethiopia. South Afr J Bot. 2006;72(4):646–8. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2006.03.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kassu A, Dagne E, Abate D, Castro A, Van Wyk B. Ethnomedical aspects of the commonly used toothbrush sticks in Ethiopia. East Afr Med J. 1999;76(11):651–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wainwright J, Sheiham A. An analysis of methods of toothbrushing recommended by dental associations, toothpaste and toothbrush companies and in dental texts. Br Dent J. 2014;217(3):E5–E5. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen O, Gabre P, Sköld UM, Birkhed D. Is the use of fluoride toothpaste optimal? Knowledge, attitudes and behaviour concerning fluoride toothpaste and toothbrushing in different age groups in Sweden. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2012;40(2):175–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2011.00658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jensen O, Gabre P, Sköld UM, Birkhed D. Fluoride toothpaste and toothbrushing; knowledge, attitudes and behaviour among Swedish adolescents and adults. Swed Dent J. 2011;35(4):203–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schüz B, Sniehotta FF, Wiedemann A, Seemann R. Adherence to a daily flossing regimen in university students: effects of planning when, where, how and what to do in the face of barriers. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33(9):612–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.00967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Judah G, Gardner B, Aunger R. Forming a flossing habit: an exploratory study of the psychological determinants of habit formation. Br J Health Psychol. 2013;18(2):338–53. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8287.2012.02086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marchesan J, Byrd K, Moss K, Preisser J, Morelli T, Zandona A, Jiao Y, Beck J. Flossing is associated with improved oral health in older adults. J Dent Res. 2020;99(9):1047–53. doi: 10.1177/0022034520916151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rad M, Kakoie S, Brojeni FN, Pourdamghan N. Effect of long-term smoking on whole-mouth salivary flow rate and oral health. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospects. 2010;4(4):110. doi: 10.5681/joddd.2010.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agnihotri R, Gaur S. Implications of tobacco smoking on the oral health of older adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2014;14(3):526–40. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee H-S, Kim M-E. Effects of smoking on oral health: preliminary evaluation for a long-term study of a group with good oral hygiene. J Oral Med Pain. 2011;36(4):225–34. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hardy LL, Bell J, Bauman A, Mihrshahi S. Association between adolescents’ consumption of total and different types of sugar-sweetened beverages with oral health impacts and weight status. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2018;42(1):22–6. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Damle SG, Bector A, Saini S. The effect of consumption of carbonated beverages on the oral health of children: a study in real life situation. Pesquisa Brasileira em Odontopediatria E Clínica Integrada. 2011;11(1):35–40. doi: 10.4034/PBOCI.2011.111.05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mishra M, Mishra S. Sugar-sweetened beverages: general and oral health hazards in children and adolescents. Int J Clin Pediatr Dentistry. 2011;4(2):119. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10005-1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elham Emami D, Wootton J, Chantal Galarneau D, Christophe Bedos D. Oral health and access to dental care: a qualitative exploration in rural Quebec. Can J Rural Med. 2014;19(2):63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bayne A, Knudson A, Garg A, Kassahun M. Promising practices to improve access to oral health care in rural communities. Rural Eval Brief. 2013;7:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams S, Parker E, Jamieson L. Oral health-related quality of life among rural‐dwelling indigenous australians. Aust Dent J. 2010;55(2):170–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2010.01220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Griffith J. Establishing a dental practice in a rural, low-income county health department. J Public Health Manage Pract. 2003;9(6):538–41. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200311000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wikipedia_the free encyclopedia. North Gondar Zone. Available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/North_Gondar_Zone.

- 34.Lankir D, Solomon S, Gize A. A five-year trend analysis of malaria surveillance data in selected zones of Amhara region, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09273-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wikipedia the free encyclopedia. List of zones of Ethiopia. Available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_zones_of_Ethiopia.

- 36.Deressa W, Hailemariam D, Ali A. Economic costs of epidemic malaria to households in rural Ethiopia. Tropical Med Int Health. 2007;12(10):1148–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hasen A. Census Mapping in Ethiopia. Paper presented at: Symposium on Global Review of 2000 Round of Population and Housing Censuses: MidDecade Assessment and Future Prospects Statistics Division. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations Secretariat; 7–10 August, 2001; New York, NY. Accessed May 12, 2016. https://unstats.un.org/unsd/demog/docs/symposium_39.htm.

- 38.Olusile AO, Adeniyi AA, Orebanjo O. Self-rated oral health status, oral health service utilization, and oral hygiene practices among adult nigerians. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-14-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yadav K, Rajkarnikar J, Yadav P, ASSESSMENT OF ORAL HYGIENE STATUS AMONG RURAL AREA OF PAME, POKHARA NEPAL Univ J Dent Sci. 2019;5(3):45–8. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Azodo CC, Amenaghawon OP. Oral hygiene status and practices among rural dwellers. Eur J Gen denTisTrY. 2013;2(01):42–5. doi: 10.4103/2278-9626.106806. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maru AM, Narendran S. Epidemiology of dental caries among adults in a rural area in India. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2012;13(3):382–8. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rathod R, Parikh J. Oral Hygiene practices and oral Health Status in Rural India. Bhavnagar University’s J Dentistry 2016, 6(1).

- 43.Diwan S, Saxena V, Bansal S, Kandpal S, Gupta N. Oral health: knowledge and practices in rural community. Indian J Community Health. 2011;23(1):29–31. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kandelman D, Petersen PE, Ueda H. Oral health, general health, and quality of life in older people. Spec Care Dentist. 2008;28(6):224–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2008.00045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kane SF. The effects of oral health on systemic health. Gen Dent. 2017;65(6):30–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lockhart PB, Brennan MT, Thornhill M, Michalowicz BS, Noll J, Bahrani-Mougeot FK, Sasser HC. Poor oral hygiene as a risk factor for infective endocarditis–related bacteremia. J Am Dent Association. 2009;140(10):1238–44. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2009.0046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Balmer R, Booras G, Parsons J. The oral health of children considered very high risk for infective endocarditis. Int J Pediatr Dent. 2010;20(3):173–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2010.01034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kotronia E, Brown H, Papacosta AO, Lennon LT, Weyant RJ, Whincup PH, Wannamethee SG, Ramsay SE. Oral health and all-cause, cardiovascular disease, and respiratory mortality in older people in the UK and USA. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):16452. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-95865-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leishman SJ, Lien Do H, Ford PJ. Cardiovascular disease and the role of oral bacteria. J oral Microbiol. 2010;2(1):5781. doi: 10.3402/jom.v2i0.5781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Păunică I, Giurgiu M, Dumitriu AS, Păunică S, Pantea Stoian AM, Martu M-A, Serafinceanu C. The bidirectional relationship between Periodontal Disease and Diabetes Mellitus—A Review. Diagnostics. 2023;13(4):681. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics13040681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nwizu N, Wactawski-Wende J, Genco RJ. Periodontal disease and cancer: epidemiologic studies and possible mechanisms. Periodontol 2000. 2020;83(1):213–33. doi: 10.1111/prd.12329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maisonneuve P, Amar S, Lowenfels AB. Periodontal disease, edentulism, and pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(5):985–95. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Puertas A, Magan-Fernandez A, Blanc V, Revelles L, O’Valle F, Pozo E, León R, Mesa F. Association of periodontitis with preterm birth and low birth weight: a comprehensive review. J Maternal-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;31(5):597–602. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2017.1293023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saini R, Saini S, Saini SR. Periodontitis: a risk for delivery of premature labor and low-birth-weight infants. J Nat Sci Biology Med. 2010;1(1):40. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.71672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mammen MJ, Scannapieco FA, Sethi S. Oral-lung microbiome interactions in lung diseases. Periodontol 2000. 2020;83(1):234–41. doi: 10.1111/prd.12301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Scannapieco FA, Shay K. Oral health disparities in older adults: oral bacteria, inflammation, and aspiration pneumonia. Dent Clin. 2014;58(4):771–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Darout IA. The natural toothbrush miswak and the oral health. Int J LifeSc Bt Pharm Res 2014, 3(3).

- 58.Arlinghaus KR, Johnston CA. Advocating for behavior change with education. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2018;12(2):113–6. doi: 10.1177/1559827617745479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Raghupathi V, Raghupathi W. The influence of education on health: an empirical assessment of OECD countries for the period 1995–2015. Archives Public Health. 2020;78(1):1–18. doi: 10.1186/s13690-020-00402-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Viinikainen J, Bryson A, Böckerman P, Kari JT, Lehtimäki T, Raitakari O, Viikari J, Pehkonen J. Does better education mitigate risky health behavior? A mendelian randomization study. Econ Hum Biology. 2022;46:101134. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2022.101134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Scheerman JF, van Loveren C, van Meijel B, Dusseldorp E, Wartewig E, Verrips GH, Ket JC, van Empelen P. Psychosocial correlates of oral hygiene behaviour in people aged 9 to 19–a systematic review with meta-analysis. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2016;44(4):331–41. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xiang B, Wong HM, Perfecto AP, McGrath CP. Modelling health belief predictors of oral health and dental anxiety among adolescents based on the Health Belief Model: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09784-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon requesting ZG, the primary author of this study.