Abstract

Background

Self-harm (any self-injury or -poisoning regardless of intent) is highly prevalent in transgender and gender diverse (TGD) populations. It is strongly associated with various adverse health and wellbeing outcomes, including suicide. Despite increased risk, TGD individuals’ unique self-harm pathways are not well understood. Following PRISMA guidelines we conducted the first systematic review of risk and protective factors for self-harm in TGD people to identify targets for prevention and intervention.

Methods

We searched five electronic databases (PubMed, PsychInfo, Scopus, MEDLINE, and Web of Science) published from database inception to November 2023 for primary and secondary studies of risk and/or protective factors for self-harm thoughts and behaviours in TGD people. Data was extracted and study quality assessed using Newcastle-Ottawa Scales.

Findings

Overall, 78 studies published between 2007 and 2023 from 16 countries (N = 322,144) were eligible for inclusion. Narrative analysis identified six key risk factors for self-harm in TGD people (aged 7–98years) were identified. These are younger age, being assigned female at birth, illicit drug and alcohol use, sexual and physical assault, gender minority stressors (especially discrimination and victimisation), and depression or depressive symptomology. Three important protective factors were identified: social support, connectedness, and school safety. Other possible unique TGD protective factors against self-harm included: chosen name use, gender-identity concordant documentation, and protective state policies. Some evidence of publication bias regarding sample size, non-responders, and confounding variables was identified.

Interpretation

This systematic review indicates TGD people may experience a unique self-harm pathway. Importantly, the risk and protective factors we identified provide meaningful targets for intervention. TGD youth and those assigned female at birth are at increased risk. Encouraging TGD people to utilise and foster existing support networks, family/parent and peer support groups, and creating safe, supportive school environments may be critical for self-harm and suicide prevention strategies. Efforts to reduce drug and alcohol use and experiences of gender-based victimisation and discrimination are recommended to reduce self-harm in this high-risk group. Addressing depressive symptoms may reduce gender dysphoria and self-harm. The new evidence presented in this systematic review also indicates TGD people may experience unique pathways to self-harm related to the lack of social acceptance of their gender identity. However, robust longitudinal research which examines gender-specific factors is now necessary to establish this pathway.

Keywords: Self-harm, Suicide, Risk factors, Protective factors, Transgender, Gender diverse

1. Introduction

Self-harm (defined here as any self-injury or -poisoning regardless of intent [1,2]) is an important public health concern [3] and is associated with various negative health and wellbeing outcomes. These include substance abuse [3,4], reduced education and employment [3] prospects, and exacerbating existing mental health issues [5]. Most concerningly, self-harm is the strongest known predictor of death by suicide [5]. Transgender and gender diverse (TGD) people are at significantly higher risk of self-harm compared to cisgender people [6,7]. Broadly, TGD describes people whose birth-assigned sex misaligns with their gender identity [8,9]. Cisgender (cis) describes people whose gender identity aligns with their birth-assigned gender and body [10]. Self-harm is highly prevalent in TGD people. Lifetime TGD self-harm prevalence estimates range between 46.4% [11,12] and 53.3% [13] compared to 6.4% in the general population [14]. Similarly, TGD people are at increased risk of suicidal thoughts [15] and behaviours [16]. Worryingly, almost 45% of TGD people attempt suicide [17], compared to 11.3% in the general population [18]. Furthermore, TGD people are at increased self-harm risk compared to their lesbian and gay peers. A recent meta-analysis reported TGD self-harm prevalence rates of 46.65% compared to 29.68% in sexual minority individuals [12]. The high prevalence of self-harm and adverse health and wellbeing outcomes indicate the need to understand TGD self-harm and identify key intervenable targets in this high-risk group.

As with the general population, TGD self-harm is muti-faceted and complex. However, TGD people experience a wider array of self-harm factors. Alongside risk factors for self-harm also experienced by the general population, such as hopelessness [19] and depression [3,20], TGD people also experience TGD-specific self-harm risk factors. For example, studies have identified experiences of transphobia [11], stigma [13,15], victimisation [4,7], and gender dysphoria [13] as significant correlates of self-harm in TGD peopleThese TGD-specific experiences may directly influence self-harm. They may also result in higher rates of depression, anxiety, or hopelessness which, in turn, might mediate the relationship between TGD-specific factors and self-harm [21]. Indeed, a longitudinal study of self-harm predictors in LGBT (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender [20,22]) youth found hopelessness and depression fully or partially mediated the relationship between self-harm and LGBT victimisation, perceived family support, and conduct disorder [20]. Other studies report victimisation, prejudice, and discrimination, in particular, to be correlated with increased odds of negative mental health outcomes and self-harm in LGBTQ+ people [[23], [24], [25]]. While these findings relate to the wider LGBT population, they suggest efforts to reduce LGBT-specific risk factors, like victimisation, may reduce self-harm by reducing depression and hopelessness. This may also be the case with TGD people. Indeed, Price-Feeney et al. [25] suggest reducing TGD-specific factors (such as discrimination) is likely to reduce the disparity between self-harm and negative mental health experienced by TGD people.

Additionally, protective factors may mitigate TGD self-harm risk. Evidence suggests social and family support, reduced transphobia, TGD-safe schools or colleges, and having gender-appropriate documentation act as potential buffers against self-harm risk in TGD people [4,7,21]. Indeed, studies have found school and peer support were associated with reduced self-harm in both LGBT [16] and TGD [7] populations. Furthermore, these protective factors are also associated with reduced sexual and intimate-partner violence in TGD people [7]. Worryingly, TGD people experience high rates of these events [7], and they are known risk factors for self-harm in TGD people [4]. Therefore, efforts to increase support for TGD people in school and wider social contexts may provide a protective buffer against self-harm, and correlating risk factors. Similarly, other studies have found family [7] and parental [21] support and feeling connected to parents and non-parental adults [4] offered protection against self-harm outcomes. These protective factors may also have mediation effects on other protective factors. For example, having parents who are supportive of one's preferred gender may facilitate access togender-seeking surgery or obtaining gender-appropriate documentation [21],which, in turn, provide a buffer against self-harm. However, the literature regarding protective factors in TGD people is limited [4], therefore the protective impact of these, and other, protective factors on TGD self-harm is unclear. Simultaneously experiencing both general and TGD-specific risk factors may result in TGD people being at increased risk of experiencing self-harm [12,13]. Furthermore, interactions between risk and protective factors may result in a unique pathway to self-harm in TGD people [4]. Examining correlates of self-harm in TGD people is necessary to ascertain why TGD people are at increased risk of self-harming behaviours [12]. Synthesising extant literature and identifying key factors for TGD self-harm is important to identify meaningful and TGD-appropriate targets for intervention, develop interventions aimed at reducing self-harm prevalence [12], and develop intervention and support strategies which reduce self-harm in TGD and associated negative outcomes [12] in this high-risk group.

Previously, TGD self-harm has been researched under the LGBTQIA+ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer/Questioning, Intersex, Asexual, and other gender identities/sexualities [22]) umbrella [12,16,24]. This conflation is problematic as TGD people are often under-represented in these studies or TGD-specific data is not extractable [24]. Interventions targeting TGD people may be inadequate because factors influencing TGD self-harm differs from others within the LGBTQIA + umbrella. Indeed, research to better understand the distinct TGD self-harm pathway is essential and recommended by researchers in the field [4,25,26]. Others have provided reviews of self-harm in TGD people [6,27]. However, these reviews focus on prevalence rates rather than identifying factors which may provide important intervenable targets. A recent scoping review found promising evidence of the protective function of peer support against self-harm and suicide in TGD people [28]. However, self-harm pathways are complex and multifaceted. Currently, there is no systematic review of self-harm risk and protective factors in TGD people: the current review fills this gap in knowledge to inform TGD-specific research and interventions to increase understanding of the TGD self-harm pathway and increase wellbeing of this high-risk group [26]. Identifying viable targets for intervention is key for researchers and clinicians [28].

1.1. Aims

Considering the paucity of research on risk and protective factors for self-harm in TGD populations our systematic review aims to critically examine and synthesise existing literature regarding risk and protective factors associated with self-harm in TGD people.

2. Method

2.1. Protocol and registration

This review was conducted in accord with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis reporting guidelines (PRISMA [29,30]) and is registered on PROSPERO: CRD 42023396437. The protocol was developed in line with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews [31].

2.2. Search strategy and selection criteria

Scoping searches identified relevant search terms and discussion between authors finalised search terms. Then, two authors (KB and LM) independently performed searches of PubMed, PsychInfo, Scopus, MEDLINE, and Web of Science databases. Searches were completed on November 6, 2023. Search terms included “self-harm”, “non-suicidal self injur*“, “suicid*“, “trans*“, and “gender divers*“. Full search terms appear in Appendix 1. Studies were included if participants self-identified as TGD (including identities under that umbrella term; see Appendix 2.) with current or past self-harm and/or suicidality, and if they examined risk and/or protective factors for self-harm behaviours (see Table 1 for full inclusion/exclusion criteria). Eligible studies were imported into Endnote [32], the reference management system. Duplicates were removed, then studies were removed if they did not meet eligibility criteria. Titles and abstracts, and then full texts, were screened independently by two researchers (KB and LM). Independently, KB and LM extracted data, then cross-checked data extraction for accuracy. Extracted data included study details (author/s, date, study location), study design information (design type, recruitment method, self-harm outcome), participant characteristics (age, gender), measures used, and study findings. Discrepancies were resolved between KB and LM. Third author input was unnecessary.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria used in screening process.

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| English language peer-reviewed studies | Reviews, editorials, commentaries, or opinion pieces, grey literature, theses/dissertations, or conference proceedings |

| Any geographical location | Studies using parent/caregiver report |

| No start or end dates were used | Studies investigating self-harm or suicidality in TGD veterans or prison inmates |

| No age restrictions | |

| Only quantitative empirical studies | |

| Cross-sectional, longitudinal, cohort and mixed methods studies | |

| Measured outcome of self-harm (irrespective of suicidal intent), suicide ideation, and/or suicide attempt (attempt on own life or completed suicide) | |

| Studies must investigate risk and/or protective factors for self-harm in Transgender and Gender-Diverse (TGD) people | |

| Participants self-identifying as TGD (including diverse gender identities; see appendix 1 |

2.3. Data synthesis

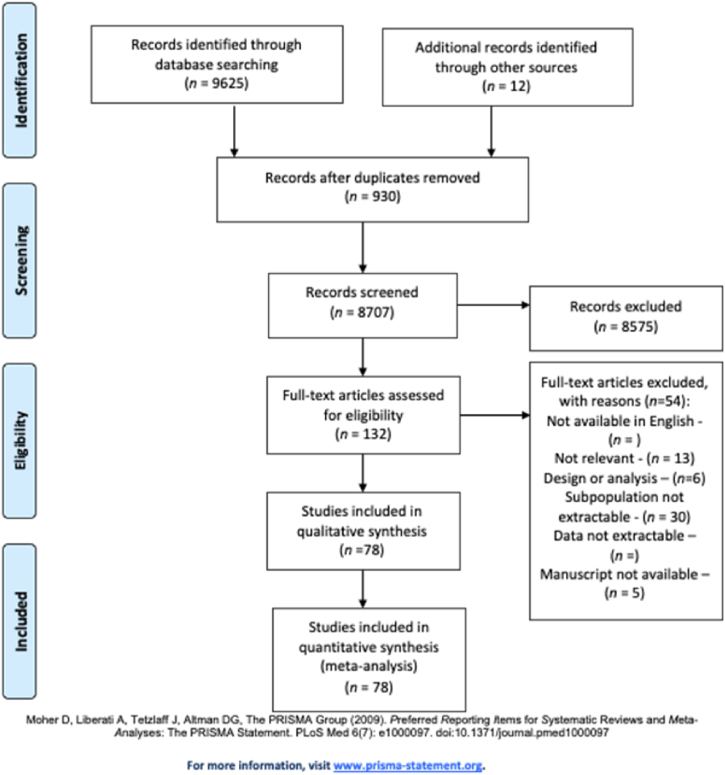

Search results are presented in Fig. 1. Due to significant heterogeneity of factors examined, we present a narrative synthesis of results of key risk and protective factors for TGD self-harm [6]. Study characteristics and findings were summarised in descriptive tabular format grouped by risk factors and protective factors, then further synthesised by TGD-specific and general factors.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram illustrating literature search process.

3. Results

Of 8707 records identified, 8573 articles were screened by abstract. One-hundred and thirty-two articles had full texts screened. Overall, 78 studies were eligible for inclusion in this review (see Fig. 1 for PRISMA search results summary). A full list of excluded papers with reasons for their exclusion is available (see Appendix 3.)Full data extraction is available on request.

3.1. Study characteristics

Of 78 eligible studies, 68 were conducted in community settings, and 10 in clinical settings. Other key study (location, study design, risk and/or protective factors examined, self-harm outcomes, and key findings) and participant (n, gender identity, age-range, and mean ages) characteristics are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of study and sample characteristic and findings.

| Author/s & date (Location) |

Study design | Participant characteristics | Outcome measures (Demographics, risk factors, protective factors) |

Self-harm definition &measure | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arcelus et al. (2016) [11] (UK) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 268 Natal female: 45.2% Natal male: 50.7% Did not answer: 4.1% Age range: 17–25 years (M = 19.9) |

Demographics Psychopathology: SCL-90; Self-esteem: RSE; Transphobia victimisation: Experiences of Transphobia Scale; Interpersonal functioning: IIP-32; Social support: MSPSS |

NSSI: SIQ |

|

| Almazan et al. (2021) USA) [33] |

Cross-sectional |

n = 27,715 Trans woman: 38.3% Trans man: 29.1% Nonbinary: 30.2% Cross-dresser: 2.5% 18+ (not provided) |

Demographics Severe psychological distress: K-6; Past-month binge alcohol use & past year tobacco smoking: all 1-item |

Past-year suicide ideation & suicide attempt measure not provided |

|

| Andrew et al. (2020) [34] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 155 Non-binary: 25.2% (no further breakdown provided) AFAB: 75.5% Age range not provided (M = 29.86) |

Demographics Trauma exposure: Life Events Checklist; Nightmares: Trauma-Related Nightmare Survey; PTSD: PTSD checklist for DSM-5 |

Suicide risk: SBQ-R |

|

| Austin et al. (2022) [35] (USA & Canada) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 372 Trans man: 89.2% Non-binary/gender fluid: 32.8% Man: 9.4% Trans Woman: 11.6% Woman: 3.2% Demiboy: 1.1% Transgender: 0.3% Other: 0.8% Two-Spirit: 05% * NB these categories are not mutually exclusive* 14–18 years (M = 15.99) |

Demographics LGBTQ-related stigma: 5-items from NHAI; Interpersonal & environmental LGBTQ microaggressions: Interpersonal LGBTQ Microaggressions subscale & Environmental LGBTQ Microaggressions subscale (adapted from LGBQ Microaggressions On-Campus Scale) |

Suicidality: 2-items from DSM-5 |

|

| Azeem et al. (2019) [36] (Pakistan) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 156 Transgender Age range not provided (M = 39.26) |

Demographics Depression: Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression Self-reported family income, illicit substance use and smoking: measures not provided |

SI: Scale for Suicide Ideation |

|

| Barboza et al. (2016) [37] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 350 Transgender MTF: 62% FTM: 35% Age range not provided |

Demographics Victimisation: 2 items; Substance use: 1 item covering 10 illicit substances; Family social support & Counselling or psychotherapy use: both 1-item |

Suicidal Risk: 2 items |

|

| Basar & Oz (2016) [38] (Turkey) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 116 Trans men: 75.9% Trans women: 24.1% Median: 25-years |

Demographics Discrimination: PDS; Depression: BDI Resilience: RSA; Social support: MSPSS |

Suicide attempt history; NSSI: ascertained by clinical interview |

|

| Bauer et al. (2016) [21] (Canada) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 380 Transgender MTF: 52.6% FTM: 47.4% 16+ (M = 32.7) |

Demographics Chronic illness/pain, immigration history, religious upbringing, childhood abuse & mental health disorders: self-reported; Transphobia: Experiences of Transphobia Scale; Transphobic harassment & violence; medical transition status, hormone use, social transition status, being perceived as cisgender: self-reported; Social support: Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Scale |

Past year suicide ideation & attempts: dichotomous scale |

|

| Brennan et al. (2017) [39] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 83 Trans women/MTF: 40% Trans men/FTM: 29% Various gender nonconforming identities: 31% 19–70 years (Not provided) |

Demographics Depression: CES-D; Anxiety: Becks Anxiety Inventory; Gender Minority Stress: GMSR |

Suicide ideation, suicide attempts & NSSI: dichotomous scale |

|

| Becerra et al. (2021) [40] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 1369 Transgender 18+ (Not provided) |

Demographics Psychological distress: K-6; Abuse/violence: 4-items; Partner abuse/violence: 24-items: Harassment/abuse due to bathroom use: 3-items |

SI & SA: 4 questions with Y/N responses |

|

| Bosse et al. (2023) [41] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 286 Transgender and Nonbinary 18–25 years (M = 21.5) |

Demographics Parental acceptance-rejection: Parental Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire; Sibling acceptance-rejection: Elder Sibling Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire; Depression: CES-D |

Suicidality: 1 item for suicide ideation, planning & attempts |

|

| Budhwani et al. (2018) [42] (Dominican Republic) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 298 Transgender women Age range not provided (M = 26) |

Demographics Sexual abuse, psychological abuse, torture, attempt on own life by another: dichotomous Y/N; Depression: 1 item; Illicit drugs: Dichotomous Y/N (in past 6-months); Income & education level: self-report |

Suicide attempts: dichotomous Y/N |

|

| Burish et al. (2022) [43] (USA & Canada) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 139 Transgender or nonbinary 18+ (M = 33.78) |

Demographics Gender Minority Stress: GMSR Social Support: Perceived Social Support Scale from Family & Friends Scale; Optimism: LOT-R; Body Acceptance & Congruence: Transgender Congruence Scale |

Suicidality: SBQ-R |

|

| Busby et all. (2020) [44] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 868 (n = 86 identified as transgender) 18+ (Not provided) |

Demographics Depression: PHQ-9; Discrimination: EDS; Interpersonal Victimisation: Interpersonal Victimisation Scale-Revised; Social Connectedness: UCLA Loneliness Scale; LGBTQ Affirmation: 3-items from LGBTQ Identity Affirmation Scale (modified from original 12-item scale) |

Past year suicide ideation; lifetime suicide attempts; NSSI: 1 item from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey |

|

| Campbell et al. (2023) [45] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 1078 gender-conversion treatment n = 24,192 control Transgender 11–17 years when gender conversion efforts began (Not provided) |

Demographics Gender conversion efforts: 1 item |

Suicide attempts: dichotomous Y/N & number of attempts |

|

| Cerel et al. (2021) [46] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 2784 27.3% transgender female 27% transgender man 38.7% non-binary 1.2% transgender unspecified 5.7% transgender other 18+ (M = 34.35 suicide exposure; M = 31.33: no suicide death exposure) |

Demographics Suicide attempt exposure, support from family of origin, mental health diagnosis, being a POC, gender binary status & gender identity: all self-reported |

Past year suicide ideation & attempts: 4-items with dichotomous Y/N |

|

| Chen et al. (2019) [47] (China) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 1309 Transgender men: n = 622 Transgender women: n = 687 Age range not provided (Transgender men M = 3.78; Transgender women M = 22.89; Overall M = 23.31) |

Demographics Feelings towards natal sex, seeking hormone therapy, seeking gender reassignment surgery, intense conflicts with parents regarding sexuality, discrimination or violence in public due to sexuality, childhood adversity (incl. Bullying and insults at school), Seeking MH support services & history of major depressive disorder: all measured using unspecified measures Depression: CESD-9; Self-esteem: RSE |

Self-harm, suicide ideation & suicide attempts measured using dedicated items (not specified) |

|

| Chen et al. (2020) [48] (China) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 250 Transgender women 18+ (M = 27.9) |

Demographics Anxiety & depression: K-10 Discrimination (incl. Verbal abuse), mental health status, PTSD screening, access to mental health services, alcohol & drug use, physical abuse, harassment (restricted personal freedom, economic control due to gender identity), sexual violence: all dichotomous Y/N |

Suicide ideation & attempts: dichotomous Y/N |

|

| Chinazzo et al. (2023) [49] (Brazil) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 213 Transgender boys/men: 48.6% Transgender girls/women: 20.8% Non-binary: 30.7% 13–25 years (M = 18.53) |

Demographics Depression: MDS; Discrimination: Lifetime & Daily Discrimination Subscale; Gender Distress: TYC-GDS; Socioeconomic Status: Deprivation Scale Social Support: MSPSS; Social Support relating to gender identity: 1 item; Gender Positivity: Gender Positivity Scale |

Suicide ideation & attempts: dichotomous Y/N |

|

| Claes et al. (2015) [50] (UK) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 155 Transgender men: n = 52 Transgender women: n = 103 17–77 years (M = 34.52) |

Demographics Psychological Symptoms: SCL-90-R; Body Dissatisfaction: HBDS; Transphobia/victimisation: Experiences of Transphobia Scale; Interpersonal Problems: IIP-32 Perceived Social Support: MSPSS; Self-Esteem: RSE |

NSSI: SIQ |

|

| Cogan et al. (2020) [51] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 155 Various gender identities 18–67 years (M = 29.86) |

Demographics Gender minority stress: GMSR; Traumatic experiences: Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 |

Suicide risk: SBQ-R |

|

| Cogan et al. (2021a) [52] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 29.86 Various gender identities 18–67 years (M = 29.86) |

Demographics Traumatic experiences: Life Events Checklist; Gender Minority Stressors: GMSR |

Suicide risk: SBQ-R |

|

| Cogan et al. (2021b) [53] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 29.86 Various gender identities 18–67 years (M = 29.9) |

Demographics Lifetime Trauma Exposure; LEC-5; Distal gender minority stressors: GMSR |

Suicide risk: SBQ-R |

|

| Cramer et al. (2016) [54] (UK) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 27,658 Various gender identities 18+ (not provided) |

Demographics Interpersonal correlates (HRD: family rejection, childhood harassment, rejection, discrimination); HRD in workplace, healthcare settings, health insurance; TGD-related physical assault, lifetime TGD-related intimate partner abuse; sexual assault; connection to TGD community; family support & co-worker support: measures not specified |

Suicidal thoughts & behaviours: 4-items with dichotomous |

|

| Davey et al. (2016) [55] (UK) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 97 Control: n = 97 60 Transgender women 37 Transgender men Control: 60 cisgender women 37 cisgender men Age range not provided (Transgender: M = 36.18; Control M = 37.16) |

Demographics, incl. Civil status, living situation TGD people were asked for treatment stage & hormone status; General Psychopathology: SCL-90-R Self-Esteem: RSE; Body Satisfaction: HBDS; Perceived Social Support: MSPSS |

NSSI: SIQ-TR |

|

| de Graaf et al. (2020) [56] (Canada, UK, Netherlands) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 2771 Natal male: n = 937 Natal female: n = 1834 13+ (M = 15.99) |

Demographics, incl. age at assessment, year of assessment, full-scale IQ, parents' marital status, & parents' social class IQ: Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children & Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale; Parent social status/education: Hollingshead's Four-Factor Index of Social Status (non-validated scale); Items from the CBCL & YSR were used to measure desire to be the opposite sex, poor peer relations & behavioural problems |

Suicidality = Item 18 from CBCL & Item 91 from YSR |

|

| dickey et al. (2015) [57] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 773 Various gender identities Age range not provided (M = 34.5) |

Demographics Depression & Anxiety: DASS-21; Feelings about body: BIS |

NSSI: ISAS |

|

| Drescher et al. (2021) [58] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 70 Transgender men: 43.4% Transgender women: 25.7% 4 Non binary: 40% 18-65 (M = 29.97) |

Demographics Homelessness & perceptions about safety: 1-item (these were adapted from the LGBT Health & Services Needs in New York State study & Seattle LGBT Commission 2010 Needs Assessment Survey respectively) Physical violence & sexual violence victimisation: 3-items |

Suicidality (ideation & attempts): Dichotomous Y/N |

|

| Drescher et al. (2023) [59] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 115 Transgender Non-conforming 18+ (M = 27.61) |

Demographic Depression: PHQ-9 Gender Minority Stressors/Resilience: GMSR Emotion Dysregulation; DERS-SF |

Suicide intent & risk: SHI |

|

| Edwards et al. (2012) [60] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 106 Transgender women: 40.6% Transgender men: 32.1% Questioning: 7.5% Genderqueer: 2.8% Nonbinary/gender fluid: 1.9% Neutrois: 0.9% Trans: 0.9% Intersex: 0.9% Not provided: 12.3% 18–65 years (M = 29.17) |

Demographics Emotional Stability: Suicide Resiliency Inventory-25; Relational Support: Perceived Social Support from Family (PSS-FA) and Friends (PSS-FR) |

Suicide risk: SBQ-R |

|

| Goldblum et al. (2018) [61] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 290 Transgender 18–65 years (M = 37.01) |

Demographics In-school gender-based victimisation: 2 items; Effect of gender-based victimisation: 1 item |

Suicide attempt history: 2-item |

|

| Gower et al. (2018) [62] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 2168 Natal female: 68.1% Natal male: 31.9% No age range provided but USA grades 5, 8, 9, 11 (ages 10–18) (M not provided) |

Demographics Parent connectedness: 3-item scale not validated; Youth Development Opportunities: 7-item scale from Developmental Assets Profile; Teacher student engagement: 4-items from Student Engagement Inventory; Feeling safe in community: 2-item scale not validated; School safety: 1-item scale not validated; Depression: PHQ-2; Alcohol, drug, cigarette use in past 30 days: Dichotomous Y/N Single items measured how much you feel other adult relatives, friends, & adults in the community care about you |

Suicide ideation and attempts: Dichotomous Y/N |

|

| Green et al. (2021) [63] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 11,914 Nonbinary: 63% Trans male: 29% Trans female: 8% 13–24 years (M = 17.62) |

Demographics Depression: PHQ; Victimisation, Receipt of puberty blockers, & exposure to GICE: all 1-item Gender-affirming hormone therapy: 3 items with binary responses; Parent support for gender identity: 2 items |

Suicidal thoughts & behaviours: 2 items from YRB survey |

|

| Grossman & D'Augelli (2007) [64] (USA) |

Mixed methods |

n = 55 Trans female: n = 31 Trans male: n = 24 15–21 years (Trans female M = 17.5 Trans male M = 19.5) |

Demographics Relation between suicide attempts & TGD status: RHAI; Lethality of suicide attempt determined by interviewer using lethality rating scale; Childhood Gender Nonconformity: GCS; Childhood Parental Abuse: Child & Adolescent Psychological Abuse Measure Body Esteem: Body-Esteem Scale for Adolescents & Adults |

Suicide ideation: 3 items; Suicide attempts: Questions used in previous TGD suicide studies (cited) inc. whether drugs and/or alcohol was used at the time |

|

| Grossman et al. (2016) [65] (USA) |

Longitudinal (First panel data) |

n = 129 MTF: n = 44 (34%) FTM: n = 44 (31%) MTDG: n = 14 (11%) FTDG: n = 31 (24%) 15–21 years (M = 18) |

Demographics Painful & provocative events components of IPTS: PPES |

Suicide ideation & attempts: 2 parts of SHBQ Suicide ideation components of IPTS: INQ Capacity for self-harm components of IPTS: ACSS |

|

| Jackman et al. (2018) [13] (USA) |

Cross-sectional (quantitative in-person interviews with survey) |

n = 332 Transgender 16+ (M = 34.56) |

Demographics Enacted stigma: EDS Felt Stigma: SCS; Transgender congruence: TCS Family support of TGD identity: 1-item; Friend support: 4-items from MSPSS; TGD community connectedness: 5-item subscale from GMSR |

NSSI: SITBI |

|

| Kaplan et al. (2017) [66] (Lebanon) |

Cross-sectional interview surveys |

n = 54 Trans females 18–58 years (M = 27) |

Demographics Depression: PHQ-& PHQ-9; General social support & social isolation: Items from Social Relationship Scale; Peer Support: 1-item regarding friends support of TGD identity; Gender identity openness: 2-items from RHS |

Suicide ideation: 4-items; Suicide attempts: 2-items |

|

| Kaplan et al. (2020) [67] (Lebanon) |

Longitudinal |

n = 16 Trans women 22–50 years (Median = 26-years) |

Demographics Sexual health & behaviour: 11-items measuring STI history; 13-items assessing sexual risk behaviour; & 23-items measuring sexual relationship power; Mental Health (Anxiety & Depression): HADS; Depression: PHQ-9; PTSD: 4-item Primary Care PTSD Screen Family acceptance: 9-item measure of family acceptance; Lifetime trauma: 25-item Trauma History Questionnaire; Social Support: Social Cohesion Scale; GMSR & MDPSS; Gender affirmation, identity & expression: TGD specific Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure, 6-items measuring gender typicality, & Outness Inventory; 31-items measuring desire/satisfaction of transition; 22-items measuring gender affirmation; 5-items measuring gender affirmation satisfaction; War exposure: War Event Questionnaire; Transphobia: 35-item scale (validated in population) |

Suicidality: (thoughts, plans, & attempts ever & in past 3 months): Dichotomous Y/N |

|

| Klein & Golub (2016) [68] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 3458 Transgender & Nonconforming 19-98 (M = 36.69) |

Demographics Substance misuse: Dichotomous Y/N; Family rejection: 7-items |

Lifetime history of suicide attempts: Dichotomous Y/N |

|

| Kota et al. (2020) [69] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 928 Trans women 18–65 years (M = 35) |

Demographics Perceived stigma: 4-items from RHM; Psychosocial impact of gender minority status: 4-items from TAIM; Depression: 6-items from BSI; Anxiety: 3-item subscale from BSI; Excessive drinking: 3-items; Non-inject drug use & Injection drug use: both 1-item; Intimate Partner Violence: 3-items; Sexual abuse: 3-items; Child Sexual Abuse: 1-item; HIV status: 1 item |

Suicide ideation: 2-items - 1 regards past-year suicide ideation & one whether this related to gender status |

|

| Kuper et al. (2021) [70] (USA0 |

Cross-sectional |

n = 1896 Gender identity other than birth assigned sex: 78.1% AFAB 14-30 (M = −21.1) |

Demographics Gender related affirmation: 7-items; Gender-related self-concept: 7-items; Victimisation (Gender & Sexual Orientation-related): 6-items; Desire for gender-affirming medical care: 1-item; Depressive symptoms: PHQ-9; Social Support: Friend & family support: MSPSS; |

Past year suicide ideation, attempts & suicide risk: SBQ-R Past year suicide attempts: binary variable modified SBQ-R |

|

| Leon et al. (2021) [71] (USA) |

Retrospective clinical data |

n = 185 AFAB: 86.6% AMAB: 13.4% 7–25 years (Median at clinic enrolment: 16.3; Median at most recent clinic visit: 18.6) |

Demographics Social transition; Medical transition; Mental health history (diagnoses, history of suicide ideation & attempts, psychiatric hospitalisation, history of abuse, bullying & victimisation) all captured from electronic medical records |

Documented in medical records |

|

| Maguen et al. (2010) [72] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 153 Gender identity female: 25% Somewhat female: 20% Equally both: 25% Somewhat male: 24% Male: 6% 18+ (M = 47) |

Demographics Mental Health Treatment: 3 items; TGD-related verbal abuse & physical violence: 2 items; IV drug use: 1 item; |

Suicide attempts: Dichotomous Y/N & number of attempts |

|

| Mak et al. (2020) [73] (USA) |

Retrospective medical record |

n = 6327 Trans men: 2875 (45%) Trans women: 3452 (55%) 3-45 (age groups: 3–17, 18–25, 26–35, 36–45, >45) |

Demographics Mental health diagnoses as stated on EMR: incl. anxiety disorders, ADHD disorders, ASD, bipolar disorders, depressive disorders, schizophrenia spectrum disorders, substance use/abuse, conduct/disruptive disorders, eating disorders, dementia, other psychoses, & personality disorders |

Suicide Attempts: Emergency Medical Records (as defined by ICD-9 or ICD10) Suicide Ideation: Binary variable: Ever or never |

|

| Maksut et al. (2020) [74] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 381 Trans women 15-29 (not provided) |

Demographics Perceived, anticipated & enacted stigma (related to TGD status): Gender Identity Stigma Scale; Sexual behaviour stigma: Sexual Behavior Stigma Scale; Severe Psychological Distress: Kessler Scale |

Suicide ideation & attempts: 1-item each |

|

| Marx et al. (2021) [75] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 610 Transgender & gender nonconforming 14–18 years (M = 15.81) |

Demographics Sexual victimisation: 1-item; Sexual harassment victimisation: 1-item; Bias-based peer victimisation: 1- item; Problematic drug use: 6-items Parental monitoring & support: 7-items; School belonging: 6-items |

Suicide ideation: 1-item |

|

| Moody & Smith (2013) [76] (Canada) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 134 Man/boy: 37.6% Woman/girl: (37.6% Trans: 50.4% Transgender (51.1% Transexual/transsexual: 45.1% FTM: 27.1% MTF: 29.3% On FTM Spectrum:15% On MTF Spectrum:17.3% Genderqueer: 24.8% Two-spirit: 7.5% Transman: 24.8% Transwoman: 30.8%) Man of trans experience: 8.3% Woman of trans experience: 7.5% Androgyne: 8.3% Woman, boy, gender blender, bi-gender, polygender, pangender, cross-dresser, transvestite, intersexual, drag king: 30.4% Other (gender bent, third gender, gender fucker, trans woman):10.6% (participants may be in multiple categories) 18–75 years (M = 36.75) |

Demographics Optimist; LOT-R; Social support: PSS-FR & PSS-Fa; Suicide resilience: SRI-25; Reasons for living; RFL |

Suicidal behaviours: SBQ-R |

|

| Parr & Howe (2019) [77] (USA) |

Mixed-methods (Cross-sectional survey data included in this review) |

n = 182 Trans female: n = 107 (26.6%)/Trans male: n = 75 (18.7)/genderqueer/GNC: n = 44 (10.9%)/Other: n = 48 (11.9%) 14–65 years (not provided) |

Demographics Identity nonaffirmation microaggression events: 3-items; Depression, acute sadness & loneliness: 2-items from SBQ-R |

Past-year suicide ideation & lifetime suicide ideation & attempts: 2-items from SBQ-R |

|

| Perez-Brumer et al. (2015) [78] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 1229 Transgender: FTM n = 532; MTF n = 697 (but included multiple gender identities) Age & mean not provided |

Demographics Structural Stigma: 4-item composite index based on gender minority measure; Internalised Transphobia: Transgender Identity Survey |

Lifetime & past-year suicide attempts: 2-items |

|

| Peterson et al. (2017) [26] (USA) |

Retrospective chart review |

n = 96 MTF: n = 54 MTF: n = 31 Gender fluid/nonbinary: n = 15 12–22 years (M = 17.1) |

Demographics Psychosocial assessment at outset appointment: drug/alcohol use; history of legal problems/arrest; gang involvement; involved in fights; history of being bullied; feel safe at home; interest in weight change: All dichotomous Y/N; Body image concerns: 1-item |

Suicide attempt history; cutting or self-injurious behaviour history: Dichotomous Y/N |

|

| Rabasco & Andover [79] (2020) | Cross-sectional |

n = 96 Transgender woman: n = 71 Transgender man: n = 26 Gender nonconforming: n = 8 Gender queer: n = 9 Other: n = 19 12–22 years (M = 17.1) |

Demographics Minority stressors: GMSR; Gender Identity State Policy Score |

Suicide ideation: BSS |

|

| Ross-Reed et al. (2019) [7] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 858 Natal male: n = 453 Natal female: n = 435 11–19 years (not provided) |

Demographics Sexual violence, dating violence, Dichotomous Y/N; Gender identity Y/N to either Cis or Gender Minority; 14 resiliency questions (family, peer, school, & community): 4-point Likert scale |

NSSI & past-year suicide attempts: Dichotomous y/N |

|

| Russell et al. (2018) [44] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 129 Transgender Gender non-conforming 15–21 years (not provided) |

Demographics Depressive symptoms: BDI for Youth; Chosen Name Use: Whether preferred name was different from name given at birth; Are you able to go by your preferred name at home; school; work with friends Social Support: CASSS |

Suicidal Ideation & behaviour: SHBQ |

|

| Scheim et al. (2020) [80] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 22,286 Trans woman: 35.6% Trans man: 33.1% Nonbinary AFAB: 25.5% Nonbinary AMAB: 5.8% 18+ (M = 30.9) |

Psychological Distress: K-6 Gender concordant identification: 1 item |

Suicide ideation: 3-items |

|

| Seelman (2016) [81] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 2325 Trans male: 43.7% Trans female: 30.9% Gender nonconforming natal female:16.6% Gender nonconforming natal male: 2.2% Crossdresser male:4.7% Crossdresser female:1.9% 18–76 years (M = 31.02) |

Demographics, incl. disability status Generation (time period) when participant attended college & age in college; Denial of bathroom access in college; Gender-appropriate housing in college (due to trans status); Interpersonal victimisation: experience of harassment/bullying; physical assault/attack; sexual assault by teachers/staff at school/college due to trans status |

Lifetime suicide attempts: Dichotomous Y/N |

|

| Snooks & McLaren (2020) [82] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 848 Trans men: n = 197 Trans women: n = 614 18–80 years (M = 26.27) |

Demographics Gender affirming surgery: Y/N/I'd rather not say; Interpersonal Needs: INQ-R; Depression: CES-D |

Suicidal thought & behaviours: SBQ-R |

|

| Staples et al. (2018) [83] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 237 Gender identity other: 55.9% FTM: 24.6% MTF: 10.2% Nonbinary: 9.3% 18–44 years (M = 28) |

Demographics Distal TGD stress: Daily Heterosexist Experiences Questionnaire; Internalised TGD negativity; transgender identity scale (TGIS) |

Suicide ideation: BSS; NSSI: DSHI |

|

| Strauss et al. (2019) [84] (Australia) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 859 Transgender Gender diverse 14–25 years (M = 19.37) |

Demographics Depressive Symptoms: PHQ-A; Anxiety: GAD-7; Self-reported psychiatric diagnoses, exposure to negative experiences, peer rejection, issues with educational setting, issues with accommodation, bullying, body dysphoria, discrimination, employment issues, experiencing significant loss, isolation from TGD people, isolated from services, helping others with mental health, lack of family support |

Self-reported adverse health outcomes (incl. self-harm, suicidal thoughts & attempts - lifetime and past-year |

|

| Strauss et al. (2020) [85] (Australia) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 859 Transgender Gender diverse: 29.7% Trans men/men: 15% Trans women/women: 48.5% various nonbinary identities (incl. nonbinary trans masc, nonbinary transfemme, agender, bigender, pangender, and others) 14–25 years (M = 19.37) |

Demographics Depressive symptom: PHQ-A (for adolescents); Anxiety: GAD-7; Self-reported psychiatric diagnoses: range of diagnoses listed (e.g., PTSD, eating disorders, substance use disorders) & n selected those which had received formal diagnoses; Exposure to abuse: various questions about negative experiences associated with poor mental health - 6 items |

Self-harm & suicidal behaviours (self-harm ideation, self-harm, reckless behaviour endangering life, suicide ideation & suicide attempts): 5 items (3-point scale) |

|

| Suen et al. (2018) [86] (Hong Kong) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 106 Assigned male at birth: 63.2% Assigned female at birth: 38.8% 25->44 years (not provided) |

Demographics Satisfaction with relationship status: Y/N; Quality of Life: 1-item- 6-point scale |

Suicidality: 4-point scale -"never thought of suicide", “have had thoughts of suicide", “have often had thoughts of suicide", “have attempted suicide" |

|

| Taliaferro et al. (2018) [87] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 2168 Transgender, genderqueer, genderfluid, or unsure about gender identity AMAB: 31.5% AFAB: 67.2% AFAB Declined to answer: 1.2% School grades 5, 8, 9, & 11 were given. These ages are 10–16 years (not provided) |

Demographics Gender identity: Y/N beside relevant gender identity; Depressive Symptoms: PHQ-2; Gender- based bullying/victimisation (2-items); Physical bullying/victimisation: 1-item Parent connectedness: 3-items; Teacher/school adult relationships: Student Engagement Instrument: Friend caring: 1-item; Connectedness to non-parental adults: 2-items; School safety: item |

Past year NSSI: How many times? >10 = repetitive |

|

| Taliaferro et al. (2019) [88] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 1635 Transgender or gender nonconforming: AMAB: 32% AFAB: 68.1% 14/15 years & 16/17 years (not provided) |

Demographics Assigned sex & gender identity: 2-items; Family substance use: 2-items; Physical health problems & mental health problems: both 1-item; Positive screen for depression: 2-items; Physical or sexual abuse: 3-items; Relationship violence, witness to family violence & teasing: all 2-items; Bullying: 4-items; running away, violence perpetrator, skipped school, cigarette smoking, alcohol use, binge drinking: all 1-item Parent connectedness: 3-items; connectedness to other adults: 2-items; school engagement & teacher/school adult relationships: both 6-items; neighbourhood safety: 2-items; prescription drug misuse: 4-items; illegal drug use: 5-items; multiple sexual partners: 2-items; bullying perpetrator: 4-items; friend caring, sport participation, involvement in school activities, religious activities, physical activity, school plans, academic achievement, school safety: all 1-item |

NSSI: 2-Item scale - 1 asking about past year NSSI engagement & how many times Suicide attempts: Ever attempted suicide, in past year, or no |

|

| Tebbe & Moradi (2016) [89] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 353 Transgender (trans women, trans men, non-binary) 18–66 years (M = 25.21) |

Demographics Prejudice & discrimination: DHEQ: Internalised antitrans attitudes: IHS; Fear of antitrans stigma: Gender-Related Fears subscale of Transgender Adaptation & Integration Measure; Drug use: Brief DAST; Alcohol use: AUDIT; Depressive symptoms: CES-D Social Support: Family, Friend, & Significant Other subscale of MSPSS |

Suicide risk: SBQ-R |

|

| Testa et al. (2012) [90] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 271 Tran women: n = 179 Trans men: n = 92 18–69 years (M = 37) |

Demographics Physical violence: 1 item, then 1 item regarding how many times these were gender-identity related; Sexual violence: 1 item, then 1 item regarding how many times these were gender-identity related; Alcohol abuse: Dichotomous Y/N; Illicit substance use: Dichotomous Y/N |

Suicide ideation & attempts: Dichotomous Y/N & how many times |

|

| Testa et al. (2017) [91] (USA & Canada) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 816 Trans man; Trans woman; female to different gender; male to different gender; Intersex 18+ (M = 32.53) |

Demographics External & internal gender minority stress: GMSR; Belongingness & perceived burdensomeness: INQ-121 |

Past year suicide ideation: SIS; Lifetime suicide ideation: 1-item; Lifetime suicide attempts: SA: 1-item |

|

| Toomey et al. (2018) [92] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 1773 Trans female: n = 202 Trans male: n = 175 Nonbinary: n = 344 Questioning: n = 1052 11–19 years (M = 14.7) |

Demographics including highest parental education level, urbanicity, & gender identity | Lifetime suicide behaviour: Dichotomous Y/N 1-item: “Have you ever tried to kill yourself?" |

|

| Treharne et al. (2020) [93] (Aotearoa/New Zealand & Australia) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 700 (TGD: n = 293; cisgender; n = 308) 18–74 years (M = 30) |

Demographics Discrimination: EDS; Psychological Distress: K-10 Perceived social support: MSPSS; Resilience: BRS |

Suicidal ideation: SIDAS Suicide ideation & attempts: Series of single items about suicidality; Self-harm: DSHI |

|

| Trujillo et al. (2017) [94] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

N = 78 Transmen: 33.3% Transwomen: 37.2% Another gender:29.5% 18+ (not provided) |

Demographics Anti-trans discrimination: HHRDS; Depression & Anxiety: HSCL-25 Perceived social support: MSPSS |

Suicidality: SBQ |

|

| Turban et al. (2019) [95] (USA, incl. Guam, American Samoa, & Puerto Rico & military bases) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 27,715 Crossdresser: 2.6% Trans woman: 63.4% Trans man: 21.1% Nonbinary/genderqueer AFAB: 8.5% Nonbinary/genderqueer AMAB: 4.5% 18->65 years (M = 31.2) |

Demographics Lifetime exposure to GICE: binary Y/N; Experiencing GICE <10yrs; Binge Drinking during past month: >1 -day consuming >5 alcoholic drinks; Cigarette & illicit drug use (excl. marijuana); Psychological distress: K-10 |

Suicide ideation I in past year/SA requiring inpatient hospitalisation in past year; Lifetime suicide ideation & attempts |

|

| Veale et al. (2017) [15] (Canada) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 923 Trans girls/women Trans boys/men Nonbinary AFAB Nonbinary AMAB 14–25 years (Not provided) |

Demographics Enacted stigma: Enacted Stigma Index; Stress: Single items from General Wellbeing Schedule School connectedness: School Connectedness Scale; Family Connectedness: 7-items (non-validated); 19–25 yr olds were given 8-item Parent Connectedness Scale; Friend Support: 1-item; Social Support: 19–25 yr olds: Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey |

Suicidality: NSSI, suicide ideation & attempts: Dichotomous Y/N |

|

| Veale et al. (2021) [96] (Aotearoa/New Zealand) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 610 Trans and nonbinary 14–83 years (M = 32.1) |

Demographics GICE: 1-item; Mental Health: K10; Family rejection: GMSR (1-item); Internalised transphobia: 3-items from Gender Identity Self-Stigma Scale |

NSSI, suicide ideation & attempts: using questions from the NZ Youth 2000 series: No to more than 5 times (5-point scale) |

|

| Wang et al. (2021) [97] (China) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 1293 Transgender & gender queer 13–29 years (M = 21.93) |

Demographics Depression: CESD-9; Anxiety: GAD-7; Presence or absence of parental psychological abuse; Self-esteem: RES |

Suicide & self-harm risk: 4-items |

|

| Woodford et al. (2018) [98] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 214 Transgender 18+ (M = 22.83) |

Demographics LGBTQ interpersonal microaggressions & victimisation on campus (frequency): 7-items incl. bathroom use & being referred to as old/natal gender; Victimisation: Sexual Orientation Victimisation Questionnaire |

Suicide attempts: 1-item |

|

| Yadegarfard et al. (2014) [99] (Thailand) |

Cross-sectional (between groups) |

n = 260 Trans women: n = 129 Cis men: n = 131 15–25 years (M = 20) |

Demographics Family Rejection: 6-item measure designed for this study (no measure exists); Social Isolation: SSA; Loneliness: ICLA Loneliness Scale-Short; Depression: DASS-21 (short version); Sexual Risk Behaviour: ‘series of questions' |

Suicidal thoughts & attempts: PANSI |

|

| Yockey et al. (2020) [100] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 790 Transgender 18+ (not provided) |

Demographics Interpersonal Violence: Y/N; Lifetime substance use (cigarettes, alcohol, vaping, & prescription drugs): 4-items Y/N |

Suicidal Behaviours 3-items Y/N |

|

| Yockey et al. (2022) [101] (USA) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 27,715 Transgender, nonbinary, genderqueer and others 18+ (not provided) |

Demographics Psychological victimisation and harassment: 1 item Y/N; Family support: 1-item 3-point scale |

Past year suicide ideation: 1- item Y/N |

|

| Zeluf et al. (2018) [102] (Sweden) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 796 Trans feminine: 19% Trans masculine: 23% Gender nonbinary: 44% Transvestite: 14% Missing: 0.2% 15–94 years (not provided) |

Demographics TGD-related victimisation: 3-items (not specified); Stigma: SCS; Trans-related healthcare issues; 2-items; Change of legal gender: 1-item; Illicit drug use & risky alcohol consumption: 1-item each Life Satisfaction: Life Satisfaction Scale; Social Support: 1-item; Practical support: 1-item; Openness with trans identity: not specified |

Past year suicide ideation: Yes once; yes, several times; No Lifetime suicide attempts: Yes, between past 2 weeks & 1 year ago; yes, more than a year ago; No |

|

| Zwickl et al. (2021) [103] (Australia) |

Cross-sectional |

n = 928 Trans male: 26% Trans female: 22% Gender non-binary: 14% Gender Queer: 4% Agender:2% Gender Fluid: 2% Gender Neutral: 1% Other - 3% 18–79 years (Median = 28 years) |

Demographics Access to gender affirming hormones; access to gender affirming surgery; Access to trans support groups (Y/N/Unsure); Perceived discrimination from employment, housing, healthcare, &/or government services: items about different aspects of these factors; Self-reported depression diagnosis: Y/N; Physical assault: Y/N |

Self-harm & suicide attempts: 1-item each Y/N/prefer not to say |

|

| Papers are ordered alphabetically. | |

| LEC-5 = Lifetime Events Checklist for DSM-5 | |

| Abbreviations: | LOT-R = Life Orientation Test-Revised |

| MTDG = Male to different gender | |

| ACSS = Acquired Capability Suicide Scale | MDS = Modified Depression Scale |

| ASAB = Assigned sex at birth | MSPSS = Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support |

| AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test | MTF = Male to Female |

| BDI = Beck Discrimination Inventory | NHAI = Nungesser Homosexual Attitudes Inventory |

| BIS = Body Investment Scale | NSSI = Nonsuicidal Self-Injury |

| Brief-DAST = Brief Drug Abuse Screening Test | PANSI = Positive & Negative Suicide Ideation Inventory |

| BRS = Brief Resilience Scale | PDS = Perceived Discrimination Scale |

| BSI = Brief Symptom Inventory | PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire |

| BSS = Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation | POC = Person of Colour |

| CAPA = Child & Adolescent Psychological Abuse Measure | PPES = Painful & Provocative Events Scale |

| CASSS = Child & Adolescent Social Support Scale | PSS-Fa = Perceived Social Support-Family |

| CES-D = Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale | PSS-Fr = Perceived Social Support-Friends |

| CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist | PTSD = Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder |

| DASS-21 = Depression Anxiety Stress Scales | RFL = Reasons for Living Inventory |

| DHEQ = Modified Daily Heterosexist Experiences Questionnaire | RHAI = Revised Homosexuality Attitude Inventory |

| DERS-SF = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale-Short Form | RHM = Reactions to Homosexuality Measure |

| DSHI – Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory | RHS = Reactions to Homosexuality Scale |

| EDS = Everyday Discrimination Scale | RSA = Resilience Scale for Adults |

| FTDG – Female to different gender | RSE = Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale |

| FTM = Female to male | SBQ-R = Suicide Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised |

| GAD-7 = Generalised Anxiety Disorder Scale | SCL-90-R = Symptom Checklist 90-Revised |

| GCS = Gender Conformity Scale | SCS = Stigma Consciousness Scale |

| GICE = Gender Identity Change Efforts | SHBQ = Self-harm Behaviors Questionnaire |

| GMSR = Gender Minority Stress & Resilience Measure | SHI = Self-Harm Inventory |

| HADS = Hospital Anxiety & Depression Scale | SIDAS = Suicidal Ideation Attributes Scale |

| HBDS = Hamburg Body Drawing Scale | SITBI = Self Injurous Thoughts & Behaviors Interview |

| HRD = Harassment, rejection & discrimination | SIQ = Self-Injury Questionnaire |

| HRDS = Heterosexist, Rejection, & Discrimination Scale | SIQ-TR = Self-Injury Questionnaire-Trauma Related |

| HSCL-25 = Hopkins Symptoms Checklist-25 | SRI-25 = Suicide Resilience Inventory-25 |

| IHS = Internalised Homonegativity Subscale | SS-A = Social Support Appraisals Scales |

| IIP-32 = Inventory of Interpersonal Problems | STI = Sexually Transmitted Infections |

| INQ = Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire | TAFE = Technical & Further Education |

| INQ-R = Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire-Revised | TAIM = Transgender Adaption & Integration Measure |

| ISAS = Non Suicidal Self-Injury and Inventory of Statements about Self-Injury | TCS = Transgender Congruence Scale |

| IPTS = Interpersonal Psychological Theory of Suicide | TYC-GDS = Trans Youth CAN! Gender Distress Scale |

| K-6 = Kessler Psychological Distress Scale-6 | TYC-GPS = Trans Youth CAN! Gender Positivity Scale |

| K-10 – Kessler Psychological Distress Scale-10 | YRB = Youth Risk Behavior Survey |

| YSR = Youth Self Report |

3.2. Sample characteristics

Participants included across studies totalled 322,144. Participant numbers in individual studies ranged from 16 to 27,715 (M = 4077.78, SD = 12,770). Ages ranged from 7- to 98-years. The combined mean age from studies, including participants’ mean age at baseline, was M = 27.73(SD = 7.40). Other sample characteristics are included in Table 2.

3.3. Measures of risk and protective factors

Most studies used validated measures of risk and/or protective factors, though measures varied significantly. However, we found little evidence many measures were validated in TGD populations which may be problematic if they cannot sufficiently capture TGD specific issues [8]. For example, ten studies used the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) for Depression [66,104,62,84,88,67,70,59,59,85] but there is no evidence PHQ is validated in TGD populations, meaning PHQ may not reliably assess depression in TGD people. This may be the case with other measures used by studies in this review. Some measures were validated in TGD populations, so are appropriate to capture TGD experiences. Perhaps unsurprisingly, these were TGD-specific measures (e.g., Gender Minority Resilience Model [39,67,91,79,43,[51], [52], [53],59]; Transgender Congruence Scale [13,43]; Transgender Identity Survey [78]; Hamburg Body Drawing Scale [55,50]. See Table 2 for full list of risk and protective factor measures used across all studies.

3.4. Assessment of methodological quality

Bias risk and methodological quality were assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale adapted for cross-sectional studies [105], case-control and cohort studies [106]. These assess bias risk in three areas: participant recruitment/selection, participant comparability, and outcome. Studies are awarded a maximum of 9-(cohort and case-control) or 10-points (cross-sectional). Studies are rated high (7–10 points), moderate (4–6 points), or low. (0–3 points) quality. These quality categories have been used in previous systematic reviews of suicidality and SH [24,107]. Two reviewers (KB & LM) independently assessed methodological quality of studies and achieved full agreement. See Table 3 for assessment findings.

Table 3.

Results of the risk of bias and quality assessments.

| Cross-sectional studies: | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author/s (Date) | Representativeness of sample | Sample size | Non-respondents | Risk factor measure | Comparability | Assessment of outcome | Statistical test | Quality rating | |

| Arcelus et al. (2016) [11] | Y | Y | YY | Y | Y | Moderate | |||

| Almazan et al. (2021) [33] | Y | Y | Y | YY | Y | Y | High | ||

| Andrew et al. (2020) [34] | YY | Y | Y | Moderate | |||||

| Austin et al. (2020) [35] | Y | Y | YY | Y | Y | Moderate | |||

| Azeem et al. (2019) [36] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Moderate | |||

| Barboza et al. (2016) [37] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Moderate | |||

| Başar & Öz. (2016) [38] | Y | YY | Y | Y | Moderate | ||||

| Bauer et al. (2015) [21] | Y | Y | YY | YY | Y | Y | High | ||

| Becerra et al. (2021) [40] | Y | YY | YY | Y | Y | High | |||

| Brennan et al. (2017) [39] | Y | YY | Y | Y | Moderate | ||||

| Bosse et al. (2022) [41] | Y | Y | YY | YY | Y | Y | High | ||

| Budhwani et al. (2018) [42] | Y | YY | Y | Y | Moderate | ||||

| Burish et al. (2022) [43] | Y | Y | Y | YY | Y | Y | High | ||

| Busby et al. (2020) [104] | Y | YY | YY | Y | Y | High | |||

| Campbell et al. (2023) [45] | Y | YY | Y | Y | Moderate | ||||

| Cerel et al. (2021) [46] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Moderate | ||||

| Chen et al. (2019) [47] | Y | YY | Y | Y | Moderate | ||||

| Chen et al. (2020) [48] | Y | YY | Y | Y | Moderate | ||||

| Chinazzo et al. (2023) [49] | Y | YY | Y | Y | Moderate | ||||

| Claes et al. (2015) [50] | Y | YY | Y | Y | Y | Moderate | |||

| Cogan et al. (2020) [51] | Y | Y | YY | Y | Y | Moderate | |||

| Cogan et al. (2021a) [52] | Y | Y | YY | Y | Y | Moderate | |||

| Cogan et al. (2021b) [53] | Y | YY | YY | Y | Y | High | |||

| Cramer et al. (2022) [54] | Y | Y | YY | Y | Y | Moderate | |||

| de Graaf et al. (2020) [99] | Y | Y | YY | YY | Y | High | |||

| dickey et al. (2015) [57] | Y | YY | Y | Y | Moderate | ||||

| Drescher et al. (2021) [58] | Y | Y | YY | Y | Y | Moderate | |||

| Drescher et al. (2023) [59] | Y | YY | Y | Y | Moderate | ||||

| Edwards et al. (2019) [60] | Y | YY | YY | Y | Y | Moderate | |||

| Goldblum et al. (2012) [61] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Moderate | |||

| Gower et al. (2018) [62] | Y | YY | YY | Y | Y | High | |||

| Green et al. (2021) [63] | Y | Y | YY | YY | Y | Y | High | ||

| Grossman & D'Augelli (2007) [64] | Y | YY | Y | YY | Y | High | |||

| Grossman et al. (2016) [65] | Y | YY | YY | Y | Y | High | |||

| Jackman et al. (2018) [13] | Y | YY | Y | Y | Moderate | ||||

| Kaplan et al. (2016) [66] | Y | Y | YY | Y | Moderate | ||||

| Klein & Golub (2018) [68] | Y | Y | Y | YY | Y | Y | High | ||

| Kota et al. (2020) [69] | Y | YY | YY | Y | Y | High | |||

| Kuper et al. (2018) [70] | Y | YY | YY | Y | Y | High | |||

| Maguen & Shipherd (2010) [72] | Y | Y | YY | Y | Y | Moderate | |||

| Maksut et al. (2020) [74] | Y | YY | YY | Y | Y | High | |||

| Marx et al. (2019) [75] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Moderate | ||

| Moody & Smith (2013) [76] | Y | YY | YY | Y | Y | High | |||

| Parr & Howe. (2019) [77] | Y | YY | YY | Y | Y | High | |||

| Perez-Brumer et al. (2015) [78] | Y | YY | YY | Y | Y | High | |||

| Rabasco & Andover (2020) [79] | Y | YY | YY | Y | Y | High | |||

| Ross-Reed et al. (2019) [7] | Y | YY | YY | Y | Y | High | |||

| Russell et al. (2018) [44] | Y | YY | YY | Y | Moderate | ||||

| Scheim et al. (2020) [80] | Y | Y | YY | YY | Y | Y | High | ||

| Seelman. (2016) [81] | Y | Y | Y | YY | Y | Y | Moderate | ||

| Snooks & McLaren (2020) [82] | Y | YY | YY | Y | Y | High | |||

| Staples et al. (2018) [83] | Y | YY | YY | Y | Y | High | |||

| Strauss et al. (2019) [84] | Y | YY | YY | Y | Y | High | |||

| Strauss et al. (2020) [85] | Y | YY | Y | Y | Moderate | ||||

| Suen et al. (2018) [86] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Moderate | ||||

| Taliaferro et al. (2018) [87] | Y | YY | YY | Y | Y | High | |||

| Taliaferro et al., (2019) [88] | Y | Y | Y | Y | YY | Y | Y | High | |

| Tebbe & Moradi. (2016) [89] | Y | Y | YY | Y | Y | Moderate | |||

| Testa et al. (2012) [90] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Moderate | |||

| Testa et al. (2017) [91] | Y | Y | Y | YY | Y | Y | Y | High | |

| Toomey et al. (2018) [92] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Moderate | |||

| Treharne et al. (2020) [93] | Y | YY | YY | Y | Y | High | |||

| Trujillo et al. (2017) [94] | Y | YY | Y | Y | Moderate | ||||

| Turban et al. (2019) [95] | Y | Y | Y | Y | YY | Y | Y | High | |

| Veale et al. (2017) [15] | Y | Y | YY | Y | Y | Moderate | |||

| Veale et al. (2021) [96] | Y | YY | YY | Y | Y | High | |||

| Wang et al. (2021) [97] | Y | YY | YY | Y | Y | High | |||

| Woodford et al. (2018) [98] | Y | Y | YY | YY | Y | Y | High | ||

| Yadegarfard et al. (2014) [99] | Y | YY | Y | Y | Moderate | ||||

| Yockey et al. (2020a) [100] | Y | Y | Y | YY | Y | Y | High | ||

| Yockey et al. (2022) [101] | Y | Y | Y | YY | Y | Y | High | ||

| Zeluf et al. (2018) [102] | Y | YY | YY | Y | Y | High | |||

| Zwickl et al. (2021) [103] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Moderate | ||||

| Cohort/Longitudinal studies: | |||||||||

| Author/s (Date) | Representativeness of exposed cohort | Selection of non-exposed cohort | Ascertainment of exposure | Demonstration outcome of interest was not present at start of study | Comparability of cohorts on basis of design or analysis (Max 2*) | Assessment of exposure | Was follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur? | Adequacy of follow up of cohorts | Quality rating |

| Kaplan et al. (2020) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Medium | ||||

| Case-Control Studies: | |||||||||

| Author/s (Date) | Case Definition Adequate | Representativeness of Cases | Selection of Controls | Definition of Controls | Comparability of cases & controls | Ascertainment of exposure | Same method for cases & controls | Non-response rate | Quality rating |

| Davey et al. (2016) | Y | Y | Y | Y | YY | Y | High | ||

NB. Ratings were in accord with the Newcastle-Ottawa Scales adapted for cross-sectional, case-control, and cohort & longitudinal studies.

Thirty-six cross-sectional studies received a ‘high’ quality rating. The remaining thirty-seven were ‘medium’ quality, indicating some bias (results of quality assessment are presented in Table 2). Bias was associated in the following three areas. First, fifty-three studies omitted data comparing respondents and non-respondents, which is important to increase external validity of results [108]. Second, twenty-seven cross-sectional studies did not control for confounding variables. Future studies should control for covariates to ensure their impact on findings is understood and accounted for [109]. Finally, sixty-three studies did not justify sample size despite most having in excess of 200-participants. Including a power analysis would be an effective way for future studies to improve in terms of quality.

The case-control study [55] was rated ‘high’ quality where bias related to outcomes ascertained using self-report methods. Finally, the cohort study [67] received a ‘medium’ rating where bias related to a selective participant sample and not controlling for covariates. Three studies used medical records [26,108] or chart review [26] methods. No bias risk assessments exist for these methods, so quality assessment is not possible. However, as they provide valuable evidence regarding TGD self-harm, they were included. However, there are limitations to consider. For example, it is difficult to determine whether information was missed, misinterpreted, or mis-recorded by clinicians, which may impact our understanding as establishing causal relationships between factors and outcomes is difficult [110]. The heterogeneity of risk and/or protective factors investigated across eligible studies precludes meaningful results from a meta-analysis [111]. Consequently, a narrative synthesis was used to describe and summarise findings.

3.5. Risk and protective factors for self-harm and suicidality in TGD people

3.5.1. Protective factors

Overall, few studies examined protective factors for TGD self-harm.). The heterogeneity of protective factors investigated made it difficult to classify factors into domains. However, some themes were identified. These are social and/or family support, connectedness, and school-related factors. Due to heterogeneity of remaining protective factors, they were classified as TGD-specific and general protective factors.

3.5.2. Social and/or family support

Thirteen studies found a significant correlation between social, and/or family support and reduced TGD self-harm and suicidality [21,66,62,102,[67], [69], [99],70,76,37,54,75,93]. Ross-Reed et al. [7] also found family support correlated significantly with reduced suicide attempts and NSSI, though community and peer support were non-significant. Similarly, Trujillo and colleagues [94] found partner support moderated risk, but family/friend support did not. A further study found perceived social support significantly associated with emotional stability which, in turn, was negatively associated with suicide risk [60]. However, independently there was no relationship between social support and suicide risk. Both Zeluf et al. [102] and Yockey et al. [100] found receiving neutral or no support correlated with increased risk of self-harm, suggesting receiving positive social support may reduce risk. Only five studies reported non-significant findings [13,50,89,43,49], though participants with self-harm history in Claes and colleagues [47] study received less support than people without self-harm history. Overall, findings provide compelling evidence of the protective and mitigating nature of social support on TGD self-harm and suicidality and highlight the importance of TGD people having accessible avenues of support. Further, they align with findings from a recent scoping review examining the role of peer support in reducing TGD suicide risk [28].

3.5.3. Connectedness

Three studies found parental connectedness associated with significantly lower odds of self-harm and/or suicidality [4,62,88]. Two further studies found connectedness to non-parental adults a significant protective factor [4,88]. Brennan et al. [39] found community connectedness a marginally negative predictor of suicide attempts. However, two studies found no correlation [43,51]. Surprisingly, transgender community connectedness was non-significant [13]. Two studies investigated social connectedness with mixed results. One study each found social connectedness a non-significant [104] and significant [39] protective factor. ‘Friend caring’ was investigated by two studies. This was included as a connectedness factor in line with previous studies of self-harm in minority youth [112]. A study each found ‘friend caring’ significantly [4] and non-significantly [88] correlated with reduced self-harm and suicidality. Overall, evidence presented indicates connectedness may be an important protective factor against TGD self-harm and suicide risk.

3.5.4. School-related protective factors

Three studies found feeling safe at school significantly correlated with reduced suicidality [4,4,62]. The 1-item scale used to measure school safety was ambiguous, so it is unclear whether school safety relates to TGD-specific or general school safety. Additionally, its ambiguity possibly elicited participant responses which were either TGD-specific and general, or both, so further clarity here is important. School belonging was also a significant factor [75]. Other school-related factors investigated were teacher/school adult relationships [4,62,88], sports participation, and involvement with school activities [4]. Considering the protective nature of school safety there was, surprisingly, no correlation between these factors and reduced self-harm. Possibly, a safe school environment offers more protection than individual associated factors. Also, effects may be limited to students in these studies and further research may yield different results. However, the evidence presented here suggests ensuring a safe school environment for TGD students may provide a key self-harm and suicide prevention opportunity.

3.5.5. Risk factors

Investigated risk factors also varied greatly, however there was some homogeneity. These were assigned sex at birth (ASAB), age, race/ethnicity, income, education level, gender identity, and depression or depressive symptoms, drug and alcohol use, gender-minority stressors, victimisation, and discrimination. The remaining risk factors were investigated by fewer than five studies. These are listed in Table 1.

3.5.6. Assigned sex at birth

Eleven studies examined ASAB. Of these, eight found being assigned female at birth (AFAB) significantly correlated with lifetime and current NSSI/suicide attempts [4,11,84,56,50,71,72,46]. Additionally, Jackman et al. [13] found transgender men were significantly more likely to use NSSI to reduce ‘bad feelings’. Given their identity, these participants were likely AFAB. Two studies found no significant correlation [86,41], while Zwickl et al. [103] reported being assigned male at birth was associated with lower odds of suicide attempts. Finally, one study [70] reported birth-assigned sex a significant predictor of suicide, though which birth-assigned sex was not clarified. However, overall, findings indicate TGD people AFAB are in particular need of support.

3.5.7. Age

Twenty-four studies investigated age as a risk factor. Six reported no significant correlation between age and self-harm and/or suicidality [78,66,102,71,36,93] and one [26] found older age associated with increased suicide attempts. The remaining studies found younger age significantly correlated with self-harm and/or suicidality [13,92,[39], [55], [73],86,42,50,70,74,41,61,68,72,[46], [100], [101]]. This is in line with evidence regarding self-harm/suicidality in the general population [5] and highlights the need for interventions targeting young TGD people.

3.5.8. Depression or depressive symptoms

Nineteen studies investigated depression or depressive symptoms. Seventeen reported a significant correlation between depression or depressive symptoms and self-harm and/or suicidality [4,11,84,88,94,[42], [48], [103],99,47,70,89,71,36,49,57,97]. Two reported no correlation [66,69]. However, one of these [66] reported 55% of participants with suicide attempt history also experienced depressive symptoms suggesting a possible relationship. Overall, these findings indicate depression and depressive symptoms are a significant risk factor for self-harm and suicidality and are a key intervenable target.

3.5.9. Physical and sexual assault

Both sexual assault/rape [74,52,54,75,85,90,58] and physical assault [4,81,88,103,48,71,40,85,90,100] are strongly correlated with TGD self-harm. All studies examining these factors recorded significant results. These results are deeply concerning but unsurprising considering TGD people experience high rates of both sexual and physical violence [90]. Supporting TGD who experience physical or sexual assault is likely to be an essential self-harm reduction strategy and will reduce the wider negative impact on mental health and wellbeing.

3.5.10. Illicit drug and alcohol use

In total, four [102,48,37,100] of six [102,48,69,89,37,100] studies reported alcohol use associated with self-harm. Similarly, six [102,42,89,36,75,100] of eight [102,42,69,89,36,72,75,100] studies found illicit drug use correlated with self-harm. These findings are in line with the general population [89] and strongly indicate reducing drug and/or alcohol use is likely to be important in reducing self-harm risk in TGD populations. Drug and alcohol use may also be linked to other mental health outcomes and self-harm risk factors [62,42]. Therefore, identifying whether drugs and/or alcohol are being utilised and addressing their use may have wide-reaching health and wellbeing benefits for TGD people.

3.5.11. Gender-minority stressors

All seven studies [39,[70], [79], [91],37,52,53] examining gender-minority stressors reported significant relationships with self-harm and suicide-related outcomes. Six used the Gender-Minority Stress-Resilience Measure which examines the impact of proximal (internalised transphobia, negative expectations of future events, concealment of gender identity) and distal (gender-related discrimination, rejection, victimisation, non-affirmation of gender identity) stressors. Two studies reported distal stressors were significant predictors of suicide ideation, attempts, or risk [39,53] and were associated with proximal stressors [53]. However, one was a weak predictor [39]. Two of the studies reported proximal factors were significant predictors of suicide risk [52,53]. Other studies focused on the individual stressors of gender-related victimisation [70,79,37] and discrimination [37] which were all significantly associated with suicide ideation and attempts. Finally, Testa et al. [91] found an indirect path between rejection and suicide ideation through internalised transphobia and negative expectations, and an indirect path between identity non-affirmation to suicide ideation through internalised transphobia. Further, they found both internalised transphobia and negative expectations were significantly correlated with suicide ideation. Identity nondisclosure, however, was not significant in any pathway.

Overall, sixteen studies examined discrimination as a distinct risk factor. Two found no correlation43,66. However, fourteen reported a significant correlation between discrimination and self-harm [15,39,84,94,103,47,91,79,74,37,49,54,59,93]. A further study did not investigate a correlational relationship but reported TGD people experienced high levels of discrimination. The authors state this is the primary reason for mental health difficulties in TGD people [48], a notion supported by others [94]. As a distinct factor, victimisation was examined by eleven studies. Of these, ten reported a significant correlation between victimisation and self-harm [88,102,91,40,54,61,75,83,98,100], and only one [104] reported no correlation. Thefindings presented here suggest gender-minority stressors, particularly victimisation and discrimination, are consistently significant in their impact on self-harm. Efforts to reduce these negative experiences and ensure their impact is identified and mitigated during interventions, will be key to addressing TGD self-harm.

3.5.12. Other risk factors

Race/ethnicity, income, education level, and gender identity were also examined. However, results were ambiguous. The mixed findings indicate no racial or ethnic group within the TGD community is at increased risk. Further, the heterogeneity in gender identities examined precludes further examination by gender identity. Findings also suggest income, education level, and gender identity are likely not salient risk factors for TGD self-harm or suicidality. However, because findings are mixed, we recommend researchers continue capturing these data to provide further clarity. Despite the ambiguity of findings here, clinicians should identify whether these factors are present as they may provide intervenable targets for some TGD people.

4. Discussion

This review examined and synthesised extant literature of self-harm risk and protective factors in TGD people. Clearly, TGD people experience a complex, nuanced pathway to self-harm. Three key protective (social and family support; connectedness to parents and other adults; school safety) and six risk (younger age; AFAB; depression/depressive symptoms; physical and sexual assault; drug and alcohol use; gender-minority stressors, particularly victimisation and discrimination) factors were identified. Conclusions from this review are somewhat limited due to factor heterogeneity, self-harm-related definitions, and outcome measures used. Further, replication of studies is lacking so conclusions and recommendations are made with some caution. Despite factor heterogeneity across 78 eligible studies, some crucial protective and risk factors for TGD self-harm were identified. These are important factors for clinicians to discuss with patients to create tailored, person-centred interventions [113].

4.1. Key protective factors