Significance

The formation of minerals by living organisms is a widespread biological phenomenon occurring throughout the evolutionary tree of life. The silica-based cell walls of diatom microalgae are impressive examples featuring intricate architectures and outstanding materials properties that still defy their reconstitution in vitro. Here, we developed a minimal mathematical model that explains the formation of branched patterns of silica ribs, enhancing the understanding of basic physico-chemical processes capable of guiding silica morphogenesis in diatoms. The generic mechanism of branching morphogenesis identified here could provide recipes for bottom–up synthesis of mineral–nanowire networks for technological applications. Moreover, similar mechanisms may apply in the biological morphogenesis of other branched structures, such as corals or bacterial biofilms.

Keywords: diatom, biomineralization, silica patterning, branching morphogenesis

Abstract

The silica-based cell walls of diatoms are prime examples of genetically controlled, species-specific mineral architectures. The physical principles underlying morphogenesis of their hierarchically structured silica patterns are not understood, yet such insight could indicate novel routes toward synthesizing functional inorganic materials. Recent advances in imaging nascent diatom silica allow rationalizing possible mechanisms of their pattern formation. Here, we combine theory and experiments on the model diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana to put forward a minimal model of branched rib patterns—a fundamental feature of the silica cell wall. We quantitatively recapitulate the time course of rib pattern morphogenesis by accounting for silica biochemistry with autocatalytic formation of diffusible silica precursors followed by conversion into solid silica. We propose that silica deposition releases an inhibitor that slows down up-stream precursor conversion, thereby implementing a self-replicating reaction–diffusion system different from a classical Turing mechanism. The proposed mechanism highlights the role of geometrical cues for guided self-organization, rationalizing the instructive role for the single initial pattern seed known as the primary silicification site. The mechanism of branching morphogenesis that we characterize here is possibly generic and may apply also in other biological systems.

Diatoms are unicellular algae that produce intricately patterned cell walls made predominantly of amorphous silica (SiO2). These photosynthetic microorganisms can be found in all aquatic habitats and play an important ecological role, with marine diatoms alone being responsible for about 20% of marine carbon fixation (1, 2). The architectural intricacy of diatom silica is unique, yet its biological functions have remained largely speculative. The cell wall serves likely as protective armor against zooplankton predators (3, 4) and might also play a role in nutrient uptake (5), enhance light harvesting for photosynthesis (6) and protect the cell from harmful ultraviolet radiation (7). Due to its unique material properties, synthetically modified diatom silica is being explored for advanced technological applications including biomedicine (8, 9).

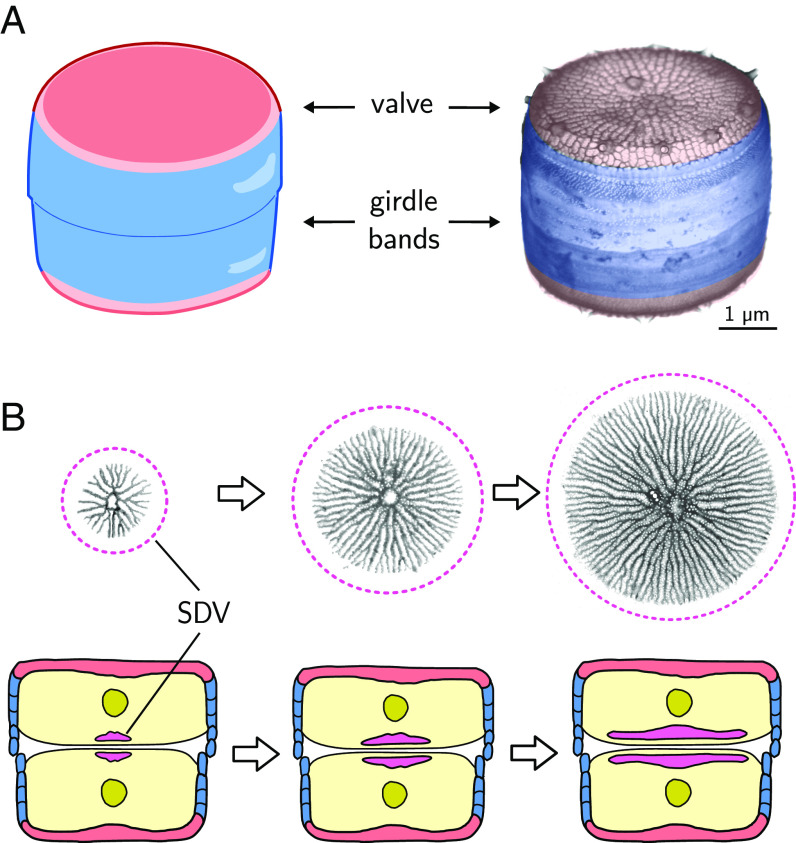

Diatoms represent a diverse group with estimated 30,000 species (10, 11), each producing a specific cell wall morphology with characteristic patterns of nano- and microscale features. Despite the large structural variety, the basic cell wall architecture is conserved, consisting of two interlocking halves, each comprising a valve and several connecting girdle bands (Fig. 1A). While girdle bands commonly possess a plain morphology with smooth surfaces and uniform patterns of pores, valves are intricately patterned, typically with a network of silica ribs and intervening hierarchical arrangements of meso- and nanoscale pores (12–15). Valves and girdle bands are produced in separate intracellular compartments each termed silica deposition vesicle (SDV) (12). The valve SDV is disk-shaped and expands concurrently with the nascent silica patterns that develop therein (Fig. 1B). Once valve morphogenesis inside the SDV is complete, the new silica valve is exocytosed and integrated into the cell wall (12, 13). In recent years, tremendous progress has been made in diatom research regarding the identification of candidate silica biogenesis proteins (16–18). However, the physical principles that govern morphogenesis of the hierarchical silica patterns in diatoms are still enigmatic.

Fig. 1.

Diatom cell wall morphogenesis. (A) Schematic of the cell wall (Left) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image (Right) of T. pseudonana, highlighting valves (red) and girdle bands (blue). (B, Top) TEM images of valve SDVs showing nascent silica rib networks. The putative outline of the SDV membrane is indicated in purple. (B, Bottom) Schematic showing a diatom cell in cross-section shortly after cytokinesis, highlighting the expanding valve SDVs (purple) in each daughter protoplast (red: valve, blue: girdle bands, yellow: cytoplasm, olive: nucleus; all other organelles are omitted for clarity).

Previous attempts to model valve morphogenesis focused on replicating the patterns in the final, mature valve rather than trying to mimic the temporal dynamics of its formation. Early diffusion-limited aggregation models produced irregular, fractal-like rib patterns, which do not yet match the regular rib patterns of diatom valves (19, 20). Moreover, these models assumed influx of soluble silica precursor from the rim of the SDV, for which there is no experimental support. Bentley et al. (21) addressed cell-scale patterns using a cellular automaton model but had to impose pre-patterns of dissolvable organic material to direct the formation of so-called virgae ribs. Other studies investigated phase-separation as a mechanism for valve morphogenesis addressing formation of pores (22, 23) but did not account for branching patterns of silica. Others put their efforts exclusively on studying the formation of regular pore patterns assuming a pre-pattern of silica ribs (22, 24, 25).

Recently, a method was developed that enabled imaging silica morphogenesis in the valve SDVs of the model diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana at various developmental stages in unprecedented detail using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (26). This provides a pseudotime series of silica formation, which allows rationalizing physico-chemical mechanisms of valve morphogenesis. As is the case in all diatoms species with radial valve symmetry (centric diatoms), valve morphogenesis starts from a central, circular seed and expands as a network of branching silica ribs with constant spacing (26–29). The initial seed is known as the primary silicification site (PSS) and obscured in the mature valve (Fig. 1A).

Here, we aimed to establish a minimal mathematical model that—based on known silica biochemistry—quantitatively accounts for the pseudotime course of the experimentally observed nascent silica rib pattern in T. pseudonana valve SDVs. Such a model may reveal general physical principles of silica morphogenesis in diatoms.

Results

Model of Branching Morphogenesis.

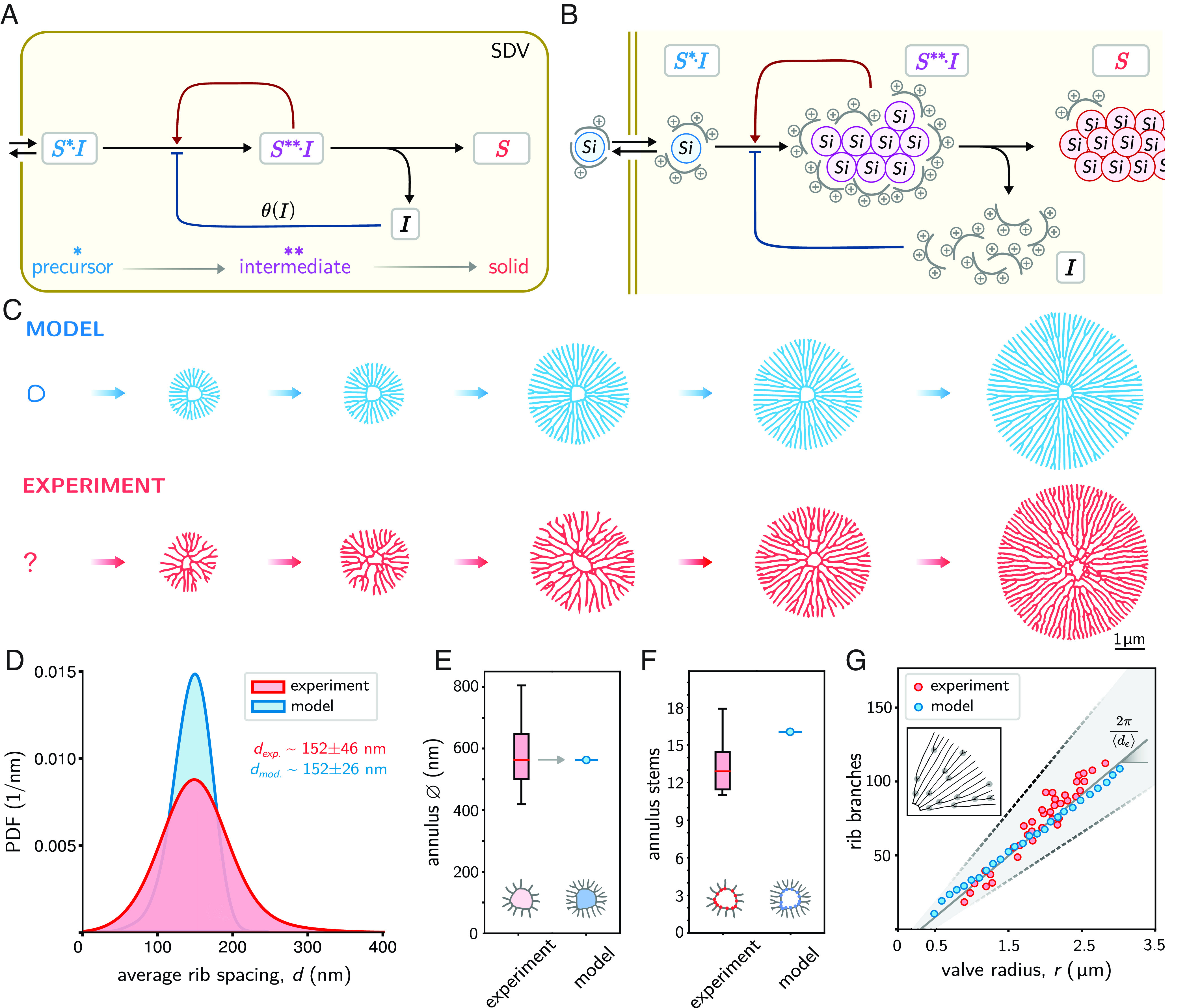

One of the most conspicuous features of nascent valve silica is the regular spacing between adjacent ribs. Spontaneous formation of regularly spaced structures is reminiscent of Turing patterns, which originate from reaction–diffusion systems with nonlinear feedback (30–32). It is tempting to assume that silica deposition in diatoms is governed by a similar mechanism. However, classical Turing systems predict the formation of multiple seeds from slightly inhomogeneous initial conditions, whereas the silica rib patterns in diatom valves always start from a single initial seed. Therefore, self-replicating reaction–diffusion systems that require a strong local perturbation (33, 34) provide a more suitable approach to rationalize diatom valve morphogenesis. We propose a putative mechanism for branching morphogenesis of silica rib patterns in terms of a minimal mathematical model supported by experimental data (Fig. 2A) and known silica biochemistry (reviewed below). We assume that a precursor for solid silica is continuously delivered to the morphogenetic compartment as a soluble, diffusible substance , with a rate that keeps the concentration of the precursor constant within the compartment. Inside the compartment, the physico-chemical conditions make the precursor susceptible to react with a diffusible component and build more of this intermediate. The intermediate is metastable and prone to solidify into silica . Upon this solidification, releases an inhibitor that slows down the reaction of the precursor with the intermediate component .

Fig. 2.

Minimal model of rib pattern morphogenesis. (A) Proposed reaction scheme, comprising silica precursor (), intermediate (), and solidified silica (). Inside the SDV, a constant precursor concentration is converted into solid silica, thereby releasing an inhibitor () that slows down precursor conversion. (B) Putative biochemical model of silica deposition in the SDV. Polyamine-based inhibitor molecules (gray) form a protective shell around a silicic acid molecule (blue) together constituting the precursor , which is incapable of condensation outside the SDV. In the acidic pH of the SDV, the affinity between inhibitor and silicic acid is reduced, thereby exposing some of the silanol groups of the silicic acid. The silicic acid of the precursor then undergoes condensation reactions with the poly-silicic acid of the pre-existing intermediate (magenta). As the condensation reactions proceed toward insoluble silica (red), more silanol groups disappear, eventually setting free the inhibitor . The rising concentration of free inhibitor molecules would lead to an increasing inhibition of silicic acid condensation by reversible binding of inhibitor molecules to precursor or intermediate, thereby reducing their reactivity. (C) Simulated rib patterns using Eq. 1 (blue), together with the pseudotime course of nascent rib networks from skeletonized TEM images representing subsequent stages of valve development (red). (D) Spacing between neighboring ribs in experimentally observed rib patterns (red, n = 38 valves) pooled over different developmental stages, and in simulated patterns (blue). The mean spacing was used to calibrate unit length in simulations. (E) Diameter of the central annulus observed in experiments (red, n = 23) and simulations (blue). The annulus diameter was used to scale initial conditions in simulations (gray arrow). (F) Number of initial stems of the central annulus in experiments (red, n = 23) and simulations (blue). (G) Number of rib branches (stem branching points excluded) as a function of valve radius for experimentally observed patterns (red), simulated patterns (blue), as well as the prediction from a simple geometric law (black).

In the scope of reaction–diffusion systems, a linear reaction chain cannot form patterns without inherent autocatalytic feedback. Yet, a simple nonlinear feedback in the formation of the intermediate component provides a reaction–diffusion system capable of self-organized pattern formation. We postulate that the intermediate accelerates its own production via autocatalytic activity, which can be inhibited by free inhibitor .

The model is compatible with known silica biochemistry in diatoms, where the SDV represents the morphogenetic compartment. Complexes of silicic acid and an inhibitor could represent the silica precursor (Fig. 2B). The silicic acid molecule is likely a silicic acid oligomer or silica nanoparticle, rather than mono-silicic acid (35, 36). (Note that a silica nanoparticle is a highly branched poly-silicic acid molecule.) The chemical nature of the proposed inhibitor is currently unknown. We hypothesize that a polyamine-based inhibitor could form—via hydrogen bonds between its amino groups (NH2) and the silanol groups (SiOH) of silicic acid—a protective shell around a silicic acid molecule, thereby constituting the precursor . Such complexes would be stable in the near-neutral pH of the cellular cytoplasm constituting the previously described soluble silica pools of diatom cells (37–39), but become metastable upon entering the acidic lumen of the SDV (40, 41). We hypothesize that the inhibitor undergoes a pH-induced conformational change due to increased protonation in the acidic environment of the SDV, and the hydrogen bonds with the silicic acid become weaker. The resultant exposure of some of the silanol groups then allows condensation reactions of the silicic acid. This generates a diverse pool of soluble poly-silicic acid molecules represented by the metastable intermediate . Intriguingly, the reactivity of the silanol groups of oligo- and poly-silicic acid toward condensation increases with increasing degree of polymerization (42, p. 214). This provides a rationale for the postulated autocatalytic self-enhancement of the reaction of silica precursor molecules with intermediates. These intermediates would still retain the inhibitor molecules, albeit with lower affinity as the fraction of remaining silanol groups decreases with increasing degree of condensation. Finally, high molecular mass poly-silicic acid molecules aggregate and become deposited as dense, insoluble silica . During this poly-condensation toward insoluble silica, inhibitor molecules would eventually be set free. The rising concentration of free inhibitor molecules leads to an increasing inhibition of silicic acid condensation.

Irrespective of molecular details of biosilica deposition as hypothesized in Fig. 2B, we anticipate that the minimal model in Fig. 2A recapitulates its key features. In particular, this model is general, posits testable hypotheses regarding positive and negative feedback and may apply in a similar form in other systems.

Quantitative Image Analysis of Nascent Silica Valves.

We took advantage of a new protocol to extract valve SDVs in synchronized cell cultures of the centric diatom T. pseudonana, which enabled TEM imaging of nascent valves at different developmental stages (26). We obtained a pseudotime course of valve morphogenesis from individual TEM images by size-sorting according to valve total area , exploiting the fact that valve patterns grow radially outward.

To quantitatively characterize developing silica valves, we developed an automated image analysis algorithm to skeletonize their rib patterns (SI Appendix, Figs. S1–S4), which allowed monitoring valve morphogenesis as a series of size-sorted skeletons (Fig. 2C). From this, we obtained statistics for the lateral spacing between neighboring ribs (Fig. 2D), the diameter of the central ring (annulus, Fig. 2E), the number of stems emanating from that annulus (Fig. 2F), and the number of branching points as function of valve radius (Fig. 2G). We found that the rib spacing is narrowly distributed, with an average of 152 nm that does not change substantially during valve development (Dataset S1). The central annuli had a median diameter of 560 nm with an average of 13 initial rib stems. The number of branching points increased linearly as function of the effective valve radius (determined from valve area ). This observation can be rationalized as follows: Assuming that the average rib spacing remains constant during morphogenesis, a simple geometric argument implies that the number of ribs intersecting the circumference of a circle with a radius should be . Hence, there should be on average one additional branching point whenever the radius increases by . This yields for the expected number of branching points in a valve of area , up to a constant offset , which corresponds to stem branching points of the annulus. A similar geometric law was previously applied to the number of defects in pore patterns of diatom valves (25).

Mathematical Description.

The proposed dynamics of silica precursor, intermediate, and solid silica can be cast into a system of partial differential equations

| [1] |

Here, the slow-down factor describes the negative feedback of the inhibitor on the conversion of precursor to intermediate. We approximate its dependence on inhibitor concentration by a sigmoid function

| [2] |

where is a constant parameter characterizing a critical inhibitor concentration and is a Hill exponent that controls the steepness of the sigmoidal curve. For low inhibitor concentration with , we have , corresponding to unrestrained conversion of the precursor, while for high inhibitor concentration with , we have , corresponding to almost complete inhibition of precursor conversion.

Model Predictions.

With a minimal set of assumptions, the model can recapitulate the temporal evolution of branched rib patterns as observed in our experiments (Fig. 2C and Movie S1). We used inter-rib spacing and the diameter of the central annulus to calibrate model parameters (Fig. 2 D and E). Interestingly, the model is capable of spontaneously forming initial stems emanating from the smooth boundary of the PSS annulus. The number of stems in simulated patterns was 16, which is comparable, but slightly larger than the mean number of rib stems observed experimentally (13 2.5, Fig. 2F). The number of initial rib stems in simulations was equal for perfectly circular annuli or deformed annuli of similar shape (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Finally, the geometric law relating the number of of branching points of silica ribs as function of effective valve radius applies to both the experimentally observed patterns and the simulated patterns. Consistently, the predicted branching frequency agreed with the measured frequency within experimental uncertainties (Fig. 2G).

The model is robust to parametric variations characterizing the inhibitor feedback (parameters , , ), albeit more sensitive to parameters characterizing precursor conversion and solidification (parameters , , , ) (SI Appendix, Figs. S6–S9). The reason is that our minimal model reduces to the known Gray–Scott model if inhibitor concentration is held fixed at a constant value and that the Gray–Scott model exhibits self-replicating dot patterns only in a restricted parameter range (43).

For simplicity and generality, we assumed an unbounded domain in the simulations. Yet, valve morphogenesis in diatoms proceeds in an expanding compartment (i.e., the SDV). We confirmed that analogous rib patterns emerge in an expanding simulation domain with reflecting boundary conditions (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). Interestingly, the model requires continuous removal of inhibitor, which can occur either by a diffusion flux in an unbounded domain (Fig. 2), or by explicitly accounting for inhibitor degradation at a constant rate in a bounded domain (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). In fact, the removal of inhibitor may be a prerequisite for the formation of additional morphological silica features that form later, such as transverse connections between ribs and the porous silica plate filling the voids between ribs.

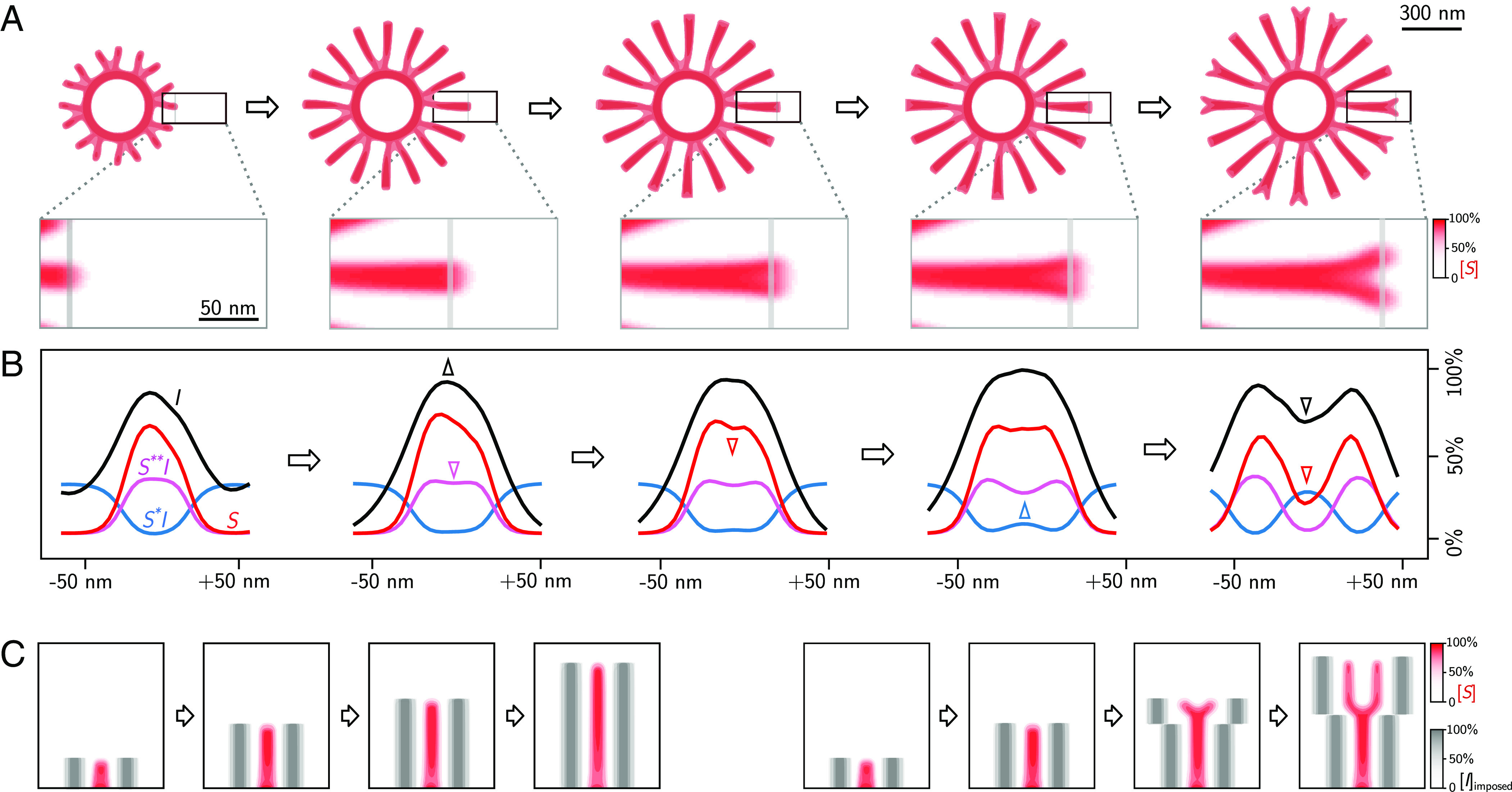

Inhibitor Controls Rib Branching.

To gain insight into the mechanism of rib branching, we followed concentration profiles of all four components at the tip of a propagating rib (Fig. 3 A and B). For a rib that is only propagating but not branching, the concentration profiles of the products , , and have a single peak, reflecting the width of the rib, while the precursor becomes locally depleted due to its conversion into intermediate. Eventually, the rib widens, causing an increase of inhibitor concentration, which slows down precursor conversion locally, causing a noticeable dent in the center of the concentration profile of the intermediate . Subsequently, a dent forms also in the concentration profile of the solid product . The concentration of precursor increases at the center of the rib, as less precursor is consumed. The nonlinear feedback in the reaction kinetics amplifies these effects, causing a further deepening of the dents in the concentration profiles with concomitant increase of precursor concentration between the two emerging peaks. Finally, two ribs have formed that start to repel each other.

Fig. 3.

Mechanism of rib branching. (A) Simulated time series of a branching rib pattern (showing normalized concentration of solid , see color map), together with region-of-interest (ROI). (B) Normalized concentration profiles of precursor (, blue), intermediate (, magenta), solid silica (, red), and inhibitor (, black) across the line-scans indicated in gray in the ROIs in panel A. Arrowheads of corresponding color highlight changes in concentration profiles. (C) Control of rib branching by externally imposed inhibitor concentration. Left: “artificial” ribs consisting of imposed inhibitor profiles (gray) at a distance equal to the typical inter-rib spacing from a propagating rib suppress branching of this rib. Right: Increasing the lateral distance of the “artificial” ribs immediately triggers branching of the propagating rib.

In the simulated valve patterns, branching of ribs seems to occur exactly when the distance between neighboring ribs becomes larger than the typical inter-rib spacing. This implies a form of chemical communication between neighboring ribs. One potential mechanism could be a competition between neighboring ribs for precursor material. We disproved this possibility by imposing artificial sinks of precursor next to a simulated solitary rib, which virtually did not change the branching behavior (SI Appendix, Fig. S11 A, B). In contrast, imposing artificial sources of inhibitor allowed us to precisely control rib branching (Fig. 3C). Specifically, we conducted two computer experiments, where a propagating rib was flanked by ghost ribs consisting of additional inhibitor. In a first case, the distance between the ghost ribs and the propagating rib was kept constant, which reliably suppressed branching. In a second case, this distance was increased at a certain time-point, which immediately triggered branching of the central rib.

Aberrant Valve Morphologies and Silica Patterns in Other Diatom Species.

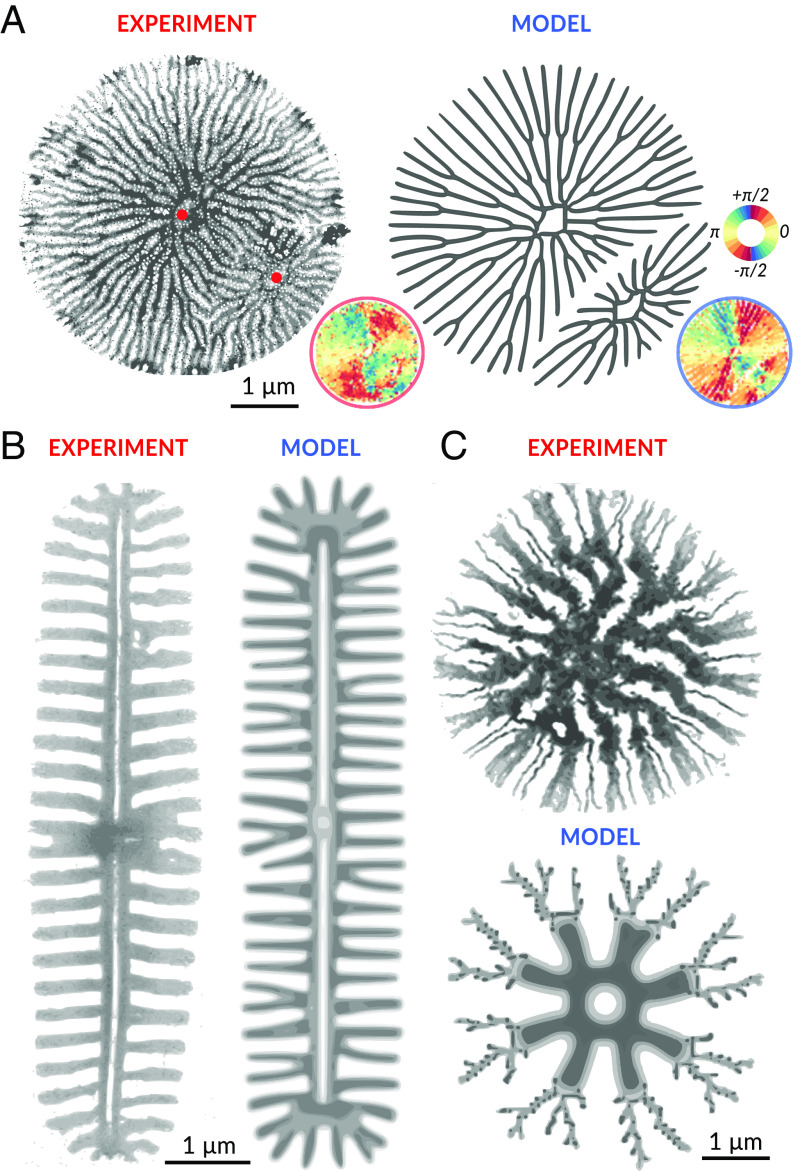

To further test the predictive capacity of the model, we investigated aberrant valve morphologies, which sporadically occur in T. pseudonana, as well as valve patterns in other species (Fig. 4). The example of an aberrant valve shown in Fig. 4A likely resulted from a second, ectopic PSS. Correspondingly, we simulated our model in a bounded circular domain with initial conditions given by two PSS that form shortly after another. To quantitatively compare the observed and the simulated aberrant valve pattern, we computed maps of local rib orientation, which displayed similar patterns.

Fig. 4.

Modeling other valve silica patterns. (A, Left) TEM image of an aberrant nascent T. pseudonana valve containing two PSSs (red dots). (A, Right) simulated rib patterns in a valve using these two PSS as initial condition. The mean nematic direction for both patterns is shown for comparison below on the Bottom Right of each image (for reference see color wheel on the Top Right). The same parameters as for normal valves shown in Fig. 2 were used. (B) Silica rib pattern in the nascent valve of the pennate diatom A. sibiricum (27) (Left), and simulated pattern using an elongated PSS with a nonsmooth boundary (Right). (C) Silica pattern in the nascent valve of the centric diatom C. cryptica (26) (Left), and simulated pattern using a dynamic switch of parameters (Right).

The model can also partially reproduce valve patterns in other diatom species. Fig. 4B shows the silica pattern in the nascent valve of the pennate (i.e., bilaterally symmetric) diatom Achnanthidium sibiricum. We initialized simulations with an elongated PSS with a high aspect ratio (SI Appendix, Fig. S12), which is typical for pennates (27, 44, 45). The simulation resulted in similar patterns. Of note, as the boundary of this PSS is mostly straight, the roughness of its boundary becomes important in controlling the emergence of initial stems.

The valves of the centric diatom Cyclotella cryptica exhibit two types of silica ribs: narrow and wide ribs, which are regularly spaced in an alternating manner (26). During valve development, the pattern of wide ribs is laid down first before the narrow ribs start to branch out from the wide ribs (Fig. 4C) (26). We hypothesize that after an initial phase, chemical conditions change, resulting in an abrupt switch in the width of the growing ribs. Correspondingly, we simulated the model with a change of parameters at an intermediate time point, resulting in a valve pattern that combines thick and thin ribs (Fig. 4C).

Discussion

Here, we introduced a minimal model for morphogenesis of branched silica rib patterns, which are common features of diatom cell walls. Despite its minimalistic nature, the model quantitatively recapitulates the experimentally observed rib pattern formation in the model diatom T. pseudonana, and is also capable of mimicking key features in other diatom species. The model makes several predictions that support or question previous hypotheses, as explained in the following:

-

(i)

It has so far been unresolved whether silica patterns of valves develop from a singular PSS (13) or are initiated at multiple sites (46, 47). Our model demands the presence of a single PSS, which orchestrates the emerging radial rib pattern. Occasionally, individual diatom cells form aberrant valves with two pattern centers. This phenomenon can be readily explained by the model as the result of two competing rib patterns (Fig. 4A).

-

(ii)

Previously, it has been assumed that silica morphogenesis inside the valve SDV is dependent on directional influx of silica precursor (19). Furthermore, it was proposed that cytoskeletal fibers may guide silica pattern formation (25, 48). The cytoskeleton likely plays an important role in determining SDV shape and positioning the central annulus and may be also involved in material delivery to the SDV. Yet, our model shows that neither directed silica influx nor a direct guidance by cytoskeletal fibers is required to explain the formation of radial rib patterns.

-

(iii)

As explained in the results section, autocatalytic rate enhancement is an inherent chemical property of silica formation from soluble silica precursors in aqueous systems. The silicification reaction proceeds through numerous oligo- and poly-silicic acid intermediates that show increasing reactivity with the precursor (42). Based on the following experimental data, we hypothesize that the precursor might consist of polyamine-stabilized silica nanoparticles: NMR studies and subcellular fractionation of diatoms identified soluble silica nanoparticles as credible silica precursors (35, 36); polyamines stabilize silica nanoparticles and prevent them from forming insoluble silica at neutral pH in vitro (49).

-

(iv)

The inhibitor is a key component of our model. We anticipate that it has a dual function: It stabilizes the silica precursor at the near neutral pH outside the SDV and, when set free during silica deposition, slows down the autocatalytic formation of the intermediate inside the SDV.

In our model, the inhibitor mediates chemical communication between neighboring ribs to set a uniform rib spacing. This requires continuous removal of inhibitor, which is probably important also to allow for formation of other silica structures. Several studies speculated that phase-separated droplets may serve as templates for the pore patterns in the valve (18, 50, 51). It is therefore possible that the inhibitor is not degraded but removed from the bulk phase by phase-separating into droplets, thus serving a third function.

-

(v)

Our model demands that solid silica precipitates irreversibly as a nondiffusible, chemically inert species.

From a broader perspective, the proposed model suggests and explains a generic mechanism of branching morphogenesis. In a nutshell, inhibitor released from neighboring ribs constrains the width of a propagating rib, which suppresses its branching. Whenever the distance to the neighbors exceeds a critical threshold, rib width increases, causing local accumulation of inhibitor, whose negative feedback drives tip splitting (Fig. 3B).

Reaction–diffusion models of self-organized pattern formation commonly employ either activator-inhibitor dynamics (30), or rely on substrate-depletion (31, 52). The model proposed here combines both concepts and thereby enables control of emergent patterns, as rib formation and branching are controlled by different chemical species, precursor, and inhibitor, respectively.

The model represents a self-replicating reaction–diffusion system (33, 34, 43), which is different from classical Turing systems as pattern formation does not start by self-amplification of small concentration fluctuations across the entire system but is only initiated in response to a sufficiently strong, local perturbation (SI Appendix, Figs. S13 and S14). Previous models of branching morphogenesis proposed for lung morphogenesis and angiogenesis featured a classical diffusion-driven Turing instability (31, 53). There, robustness could be achieved by assuming different reaction kinetics in different tissues (54). Self-replicating reaction–diffusion systems provide a different means to endow robustness with respect to inherent concentration fluctuations (SI Appendix, Fig. S15). Additionally, they provide an example of guided self-organization, where initial conditions guide pattern formation.

Last, we deem our minimal model conceptually simpler than other reaction–diffusion systems that, like our model, do not rely on a classical Turing instability, and which were proposed to describe branching morphogenesis (52, 55, 56). Different from these models, our minimal model comprises only a linear reaction chain with autocatalytic enhancement and a single negative feedback loop mediated by the inhibitor. Additionally, it obeys mass balance, and it makes explicit how transient dynamics builds solid-like structures (SI Appendix, Fig. S16).

The chemical reaction scheme proposed here has the emergent property that tips start to branch whenever the distance to their neighbors exceeds a critical threshold. Several coarse-grained models of branching morphogenesis evoked this feature as a heuristic rule to successfully predict network statistics (57–60). It is tempting to speculate that the branching mechanisms introduced here may apply in other biological systems (61–63), with the model components assigned to different roles, e.g., different differentiation stages of cells, chemical signals, or transcription factors (see SI Appendix, Fig. S17 for simulated patterns resembling corals and bacterial biofilms).

Materials and Methods

Imaging of Nascent Silica.

Visualization of synchronized cell cultures and correlative fluorescence and electron microscopy of valve SDVs were performed as described previously (26).

Image Analysis of TEM Images and the Model.

TEM images of nascent silica valves were analyzed using custom-made automatic skeleton recognition (python v3.7.4, using scikit-image package v0.15.0 (64)). First, a binary mask of the rib network was determined using adaptive thresholding and the rib skeleton determined using a pixel thinning algorithm. The obtained skeleton was then pruned to remove short branches up to 50 nm in length (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). In total, we were able to extract skeletons from 38 valves (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). The inter-rib spacing was calculated from the inverted skeleton mask, followed by application of the median-axes function, which provided a graph of points equally distant to adjacent ribs (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). The number of branching points, cross-connections, and terminal points was computed from the skeleton mask using the mahotas python library (v1.4.11; pixel-type connectivity) (65) with custom kernels for pixel connectivity (SI Appendix, Fig. S4).

The effective valve radius was calculated from the area of the convex-hull of the skeleton mask. Due to the relatively high level of silicification in the center of the valve, skeletons of the annuli were traced manually (n = 23, from the total of n = 38) and then analyzed analogously. For Fig. 4A, the mean local rib orientation was computed using a histogram of oriented gradients.

Numerical Integration of Partial Differential Equations.

To numerically integrate (Eq. 1), we used a forward Euler scheme with constant time step and regular grid, with three-point stencil for the diffusion operator and reflecting boundary conditions. Integration was carried out in a large static square domain (Figs. 2 and 3) or in a dynamic disk-shaped domain that expands at constant speed (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). To mitigate grid effects, small noise terms were added to diffusion coefficients as in refs. 66 and 67.

The initial seed representing the PSS was chosen as for all pixels belonging to digitally drawn, distorted annuli of thickness , and otherwise. The initial concentration of was set to stationary state for the entire domain; initial concentrations were set to zero for and .

Parameters for Figs. 2 and 3: , , , , , , . Numerical computations were carried out in normalized units; unit length was calibrated afterward to match mean inter-rib spacing in Fig. 2D. Parameters used in Fig. 4 for other species are listed in SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Dataset S01 (XLSX)

Dataset S02 (XLSX)

Dataset S03 (XLSX)

Simulation of silica valve morphogenesis showing the normalized concentration of solid silica as function of time (corresponding to Fig. 2C)

Acknowledgments

I.B., N.K., and B.M.F. were supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy - EXC-2068-390729961. B.M.F. acknowledges support through a Heisenberg grant of the DFG (421143374). We thank Carl Modes for stimulating discussions as well as Szabolcs Horvát for advice on image analysis.

Author contributions

I.B., N.K., and B.M.F. designed research; I.B. performed research; I.B. and B.M.F. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; I.B. analyzed data; and I.B., N.K., and B.M.F. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. E.H. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

Contributor Information

Nils Kröger, Email: nils.kroeger@tu-dresden.de.

Benjamin M. Friedrich, Email: benjamin.m.friedrich@tu-dresden.de.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

Raw data and the Python code used for image analysis can be accessed at ref. 68. All other data are included in the manuscript and/or supporting information.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Falkowski P. G., Barber R. T., Smetacek V., Biogeochemical controls and feedbacks on ocean primary production. Science 281, 200–206 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Field C. B., Behrenfeld M. J., Randerson J. T., Falkowski P., Primary production of the biosphere: Integrating terrestrial and oceanic components. Science 281, 237–240 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamm C. E., et al. , Architecture and material properties of diatom shells provide effective mechanical protection. Nature 421, 841–843 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pančić M., Torres R. R., Almeda R., Kiørboe T., Silicified cell walls as a defensive trait in diatoms. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 286, 20190184 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell J. G., et al. , The role of diatom nanostructures in biasing diffusion to improve uptake in a patchy nutrient environment. PLoS One 8, e59548 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuhrmann T., Landwehr S., Rharbl-Kucki M. E., Sumper M., Diatoms as living photonic crystals. Appl. Phys. B: Lasers Opt. 78, 257–260 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aguirre L. E., et al. , Diatom frustules protect DNA from ultraviolet light. Sci. Rep. 8, 5138 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.G. L. Rorrer, Diatom Nanotechnology: Progress and Emerging Applications (The Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, 2017).

- 9.Tramontano C., Chianese G., Terracciano M., de Stefano L., Rea I., Nanostructured biosilica of diatoms: From water world to biomedical applications. Appl. Sci. 10, 6811 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guiry M. D., How many species of algae are there? J. Phycol. 48, 1057–1063 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D. G. Mann, P. Vanormelingen, An inordinate fondness? The number, distributions, and origins of diatom species. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 60, 414–420 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Round F. E., Crawford R. M., Mann D. G., Diatoms: Biology and Morphology of the Genera (Cambridge University Press, 1990). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pickett-Heaps J., Schmid A., Edgar L., Round F., Chapman D., Progress in Phycological Research (Biopress Ltd., Bristol, 1990). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Javaheri N., et al. , Temperature affects the silicate morphology in a diatom. Sci. Rep. 5, 1–9 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.I. Babenko, B. M. Friedrich, N. Kröger, “Structure and morphogenesis of the frustule” in The Molecular Life of Diatoms, A. Falciatore, T. Mock, Eds. (Springer, Cham, Switzerland, 2022), pp. 287–312.

- 16.Skeffington A. W., et al. , Shedding light on silica biomineralization by comparative analysis of the silica-associated proteomes from three diatom species. Plant J. 110, 1700–1716 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brembu T., Chauton M. S., Winge P., Bones A. M., Vadstein O., Dynamic responses to silicon in Thalasiossira pseudonana - Identification, characterisation and classification of signature genes and their corresponding protein motifs. Sci. Rep. 7, 4865 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heintze C., et al. , The molecular basis for pore pattern morphogenesis in diatom silica. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 119, e2211549119 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gordon R., Drum R. W., The chemical basis of diatom morphogenesis. Int. Rev. Cytol. (Elsevier) 150, 243–372 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parkinson J., Brechet Y., Gordon R., Centric diatom morphogenesis: A model based on a DLA algorithm investigating the potential role of microtubules. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Cell Res. 1452, 89–102 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bentley K., Cox E. J., Bentley P. J., Nature’s batik: A computer evolution model of diatom valve morphogenesis. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 5, 25–34 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bobeth M., et al. , Continuum modelling of structure formation of biosilica patterns in diatoms. BMC Mater. 2, 1–11 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lenoci L., Camp P. J., Diatom structures templated by phase-separated fluids. Langmuir 24, 217–223 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Willis L., Cox E., Duke T., A simple probabilistic model of submicroscopic diatom morphogenesis. J. Roy. Soc. Interf. 10, 20130067 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feofilova M., et al. , Geometrical frustration of phase-separated domains in Coscinodiscus diatom frustules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 119, e2201014119 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heintze C., et al. , An intimate view into the silica deposition vesicles of diatoms. BMC Mater. 2, 1–15 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Y. D. Bedoshvili, Y. V. Likhoshway, Cellular Mechanisms of Diatom Valve Morphogenesis (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2019), pp. 99–114.

- 28.Kaczmarska I., Ehrman J. M., Davidovich N. A., Davidovich O. I., Podunay Y. A., Valve morphogenesis in selected centric diatoms. Botany 98, 725–733 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaczmarska I., Ehrman J. M., Mills K. E., Sutcliffe S. G., Samanta B., Vegetative cell enlargement in selected centric diatom species-an alternative way to propagate an individual genotype. Europ. J. Phycol. 58, 1–18 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turing A., The chemical basis of morphogenesis. Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. London 237, 37–72 (1952). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gierer A., Meinhardt H., A theory of biological pattern formation. Kybernetik 12, 30–39 (1972). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kondo S., Miura T., Reaction-diffusion model as a framework for understanding biological pattern formation. Science 329, 1616–1620 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parekh N., Kumar V. R., Kulkarni B., Control of self-replicating patterns in a model reaction-diffusion system. Phys. Rev. E 52, 5100 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lesmes F., Hochberg D., Morán F., Pérez-Mercader J., Noise-controlled self-replicating patterns. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 238301 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gröger C., Sumper M., Brunner E., Silicon uptake and metabolism of the marine diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana: Solid-state 29Si NMR and fluorescence microscopic studies. J. Struct. Biol. 161, 55–63 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reichelt T., Bode T., Jordan P. F., Brunner E., Towards the chemical analysis of diatoms’ silicon storage pools: A differential centrifugation-based separation approach. Minerals 13, 653 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thamatrakoln K., Hildebrand M., Silicon uptake in diatoms revisited: A model for saturable and nonsaturable uptake kinetics and the role of silicon transporters. Plant Physiol. 146, 1397–1407 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin-Jézéquel V., Hildebrand M., Brzezinski M. A., Silicon metabolism in diatoms: Implications for growth. J. Phycol. 36, 821–840 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumar S., Rechav K., Kaplan-Ashiri I., Gal A., Imaging and quantifying homeostatic levels of intracellular silicon in diatoms. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz7554 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vrieling E. G., Gieskes W., Beelen T. P., Silicon deposition in diatoms: Control by the pH inside the silicon deposition vesicle. J. Phycol. 35, 548–559 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shimizu K., Del Amo Y., Brzezinski M. A., Stucky G. D., Morse D. E., A novel fluorescent silica tracer for biological silicification studies. Chem. Biol. 8, 1051–1060 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iler R. K., The Chemistry of Silica. Solubility, Polymerization, Colloid and Surface Properties, and Biochemistry (John Wiley & Sons, 1979). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nishiura Y., Ueyama D., Spatio-temporal chaos for the gray-Scott model. Phys. D: Nonlinear Phenom. 150, 137–162 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chiappino M. L., Volcani B., Studies on the biochemistry and fine structure of silicia shell formation in diatoms VII. Sequential cell wall development in the pennate Navicula pelliculosa. Protoplasma 93, 205–221 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Idei M., Sato S., Tamotsu N., Mann D. G., Valve morphogenesis in Diploneis smithii (Bacillariophyta). J. Phycol. 54, 171–186 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li C. W., Volcani B. E., Studies on the biochemistry and fine structure of silica shell formation in diatoms - IX. Sequential valve formation in a centric diatom Chaetoceros rostratum. Protoplasma 124, 30–41 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schnepf E., Deichgräber G., Drebes G., Morphogenetic processes in Attheya decora (Bacillariophyceae, Biddulphiineae). Plant System. Evol. 135, 265–277 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tesson B., Hildebrand M., Extensive and intimate association of the cytoskeleton with forming silica in diatoms: Control over patterning on the meso-and micro-scale. PLoS One 5, e14300 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sumper M., Biomimetic patterning of silica by long-chain polyamines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43, 2251–2254 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sumper M., Brunner E., Learning from diatoms: Nature’s tools for the production of nanostructured silica. Adv. Funct. Mater. 16, 17–26 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Poulsen N., Sumper M., Kröger N., Biosilica formation in diatoms: Characterization of native silaffin-2 and its role in silica morphogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 12075–12080 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meinhardt H., Morphogenesis of lines and nets. Differentiation 6, 117–123 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Menshykau D., Iber D., Kidney branching morphogenesis under the control of a ligand-receptor-based Turing mechanism. Phys. Biol. 10, 046003 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Menshykau D., Blanc P., Unal E., Sapin V., Iber D., An interplay of geometry and signaling enables robust lung branching morphogenesis. Development 141, 4526–4536 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Menshykau D., Kraemer C., Iber D., Branch mode selection during early lung development. PLoS Comp. Biol. 8, e1002377 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhu X., Yang H., Turing instability-driven biofabrication of branching tissue structures: A dynamic simulation and analysis based on the reaction-diffusion mechanism. Micromachines 9, 109 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hannezo E., et al. , A unifying theory of branching morphogenesis. Cell 171, 242–255 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Honda H., Fisher J. B., Tree branch angle: Maximizing effective leaf area. Science 199, 888–890 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Luo N., Wang S., Lu J., Ouyang X., You L., Collective colony growth is optimized by branching pattern formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Syst. Biol. 17, e10089 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Uçar M. C., et al. , Theory of branching morphogenesis by local interactions and global guidance. Nat. Commun. 12, 6830 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Merks R., Hoekstra A., Kaandorp J., Sloot P., Models of coral growth: Spontaneous branching, compactification and the Laplacian growth assumption. J. Theor. Biol. 224, 153–166 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.P. Deng, L. de Vargas Roditi, D. Van Ditmarsch, J. B. Xavier, The ecological basis of morphogenesis: Branching patterns in swarming colonies of bacteria. New J. Phys. 16, 015006 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Lang C., Conrad L., Michos O., Mathematical approaches of branching morphogenesis. Front. Genet. 9, 673 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Van der Walt S., et al. , scikit-image: Image processing in Python. PeerJ 2, e453 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Coelho L. P., Mahotas: Open source software for scriptable computer vision. J. Open Res. Softw. 1, e3 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kawasaki K., Mochizuki A., Matsushita M., Umeda T., Shigesada N., Modeling spatio-temporal patterns generated by Bacillus subtilis. J. Theoret. Biol. 188, 177–185 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mimura M., Sakaguchi H., Matsushita M., Reaction-diffusion modelling of bacterial colony patterns. Physica A: Stat. Mech. Appl. 282, 283–303 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 68.I. Babenko et al. , Mechanism of branching morphogenesis inspired by diatom silica formation. Zenodo. 10.5281/zenodo.8095546. Deposited 29 June 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Dataset S01 (XLSX)

Dataset S02 (XLSX)

Dataset S03 (XLSX)

Simulation of silica valve morphogenesis showing the normalized concentration of solid silica as function of time (corresponding to Fig. 2C)

Data Availability Statement

Raw data and the Python code used for image analysis can be accessed at ref. 68. All other data are included in the manuscript and/or supporting information.