Significance

Argonaute (AGO) proteins, loaded with small RNAs called microRNAs (miRNAs), are essential regulators of gene expression. Mutations in human AGO proteins have been reported to cause neurodevelopmental disorders. To understand how these mutations affect the molecular functions of AGO protein, we engineered four human AGO mutations into an AGO gene from a genetically tractable model system, Caenorhabditis elegans. We show that these mutations disrupt miRNA production and cause genome-wide impacts on gene expression, likely by interfering with functional miRNA-centered complexes and ultimately leading to global misregulation of gene expression.

Keywords: microRNA, Argonaute, neurodevelopmental disorder, intellectual disability, disease modeling

Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNA) associate with Argonaute (AGO) proteins and repress gene expression by base pairing to sequences in the 3′ untranslated regions of target genes. De novo coding variants in the human AGO genes AGO1 and AGO2 cause neurodevelopmental disorders (NDD) with intellectual disability, referred to as Argonaute syndromes. Most of the altered amino acids are conserved between the miRNA-associated AGO in Homo sapiens and Caenorhabditis elegans, suggesting that the human mutations could disrupt conserved functions in miRNA biogenesis or activity. We genetically modeled four human AGO1 mutations in C. elegans by introducing identical mutations into the C. elegans AGO1 homologous gene, alg-1. These alg-1 NDD mutations cause phenotypes in C. elegans indicative of disrupted miRNA processing, miRISC (miRNA silencing complex) formation, and/or target repression. We show that the alg-1 NDD mutations are antimorphic, causing developmental and molecular phenotypes stronger than those of alg-1 null mutants, likely by sequestrating functional miRISC components into non-functional complexes. The alg-1 NDD mutations cause allele-specific disruptions in mature miRNA profiles, accompanied by perturbation of downstream gene expression, including altered translational efficiency and/or messenger RNA abundance. The perturbed genes include those with human orthologs whose dysfunction is associated with NDD. These cross-clade genetic studies illuminate fundamental AGO functions and provide insights into the conservation of miRNA-mediated post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms.

The proper development, maintenance, and physiological functioning of multicellular animals require the robust control of complex and dynamic patterns of gene expression. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are endogenous, small, non-coding RNAs that play important roles in post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression (1, 2). miRNAs are transcribed from genomic loci and undergo several processing steps leading to functional maturation. The primary miRNA is processed in the nucleus by the Microprocessor into the precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA) (1). The pre-miRNA is processed by Dicer in the cytoplasm into an RNA duplex, which associates with a protein of the Argonaute (AGO) family. One strand of the miRNA duplex is retained by the AGO and becomes the functional miRNA (the “guide” strand, miR), while the other strand (“passenger” strand, miR*) is expelled from the complex and degraded. The miR-AGO complex subsequently recruits other protein factors including GW182 to form the miRNA-induced silencing complex (miRISC) (1). miRISC binds target messenger RNAs (mRNAs) at sites within the 3′ untranslated region via partially complementary base-pairing (1), leading to repression of target gene expression via translational inhibition and/or mRNA destabilization (3).

AGO proteins participate in multiple steps of miRNA biogenesis and function, including pre-miRNA processing, miRNA duplex loading, guide strand selection, passenger strand disposal, target mRNA recognition, and repression of target gene expression (4). Accordingly, depleting AGOs by mutation or RNA interference can result in pleiotropic miRNA loss-of-function (lf) phenotypes (5–9).

Certain point mutations at conserved amino acid residues of the Caenorhabditis elegans miRNA AGO ALG-1 cause heterochronic developmental phenotypes without significant depletion of ALG-1 protein or of its capacity to associate with miRNAs (10). Strikingly, these alg-1 “antimorphic” mutants exhibit more severe developmental defects than alg-1 null. In alg-1 null mutants, the loss of alg-1 is largely compensated by the paralogous alg-2 gene, whose protein product ALG-2 associates with the miRNAs that would ordinarily bind ALG-1 (5). However, in alg-1 antimorphic mutants, the mutant ALG-1 antagonizes the redundancy of alg-2 by sequestering miRNAs in defective ALG-1 miRISC, preventing those miRNAs from associating with ALG-2 (10).

Human AGO genes are implicated in multiple diseases including male infertility, various cancers, and neuronal developmental disorders (NDD) (11–15). In certain cases, the disease is associated with loss of function of multiple members of the AGO family: five children with psychomotor developmental delay and other non-specific neuronal-muscular disorder syndromes have been reported to be heterozygous for large de novo deletions in the 1p34.3 locus, which includes AGO1, AGO3, and AGO4 (16, 17). Other cases involve de novo point mutations that change or delete a single amino acid of one AGO locus: Exome sequencing identified 18 de novo coding variants of AGO1 in children who exhibit NDD with intellectual disability (ID) and autism-spectrum disorders (ASD) (18); similarly, 12 de novo coding variants of human AGO2 were identified in children with spectrums of developmental delay, ID, and ASD (19). These conditions (AGO1-related syndrome and AGO2/Lessel-Kreienkamp/Leskres syndrome), where patients who exhibit NDD with ID and ASD carry genomic AGO mutations, are collectively termed “Argonaute syndromes” (https://argonautes.ngo/en). In several cases, the same de novo mutations were identified in independent families, indicating that the corresponding amino acids critically contribute to AGO function. Many of the mutated amino acids are conserved between human AGO1 and AGO2, as well as between the homologous human and C. elegans AGOs (Fig. 1A). The conservation of these amino acids and the phenotypes associated with the corresponding mutants suggest that these amino acids are critical for evolutionarily conserved functions of AGO proteins. Interestingly, two of the patients’ variants are de novo mutations (corresponding to H751L and C749Y in human AGO1) adjacent to a previously described antimorphic allele (corresponding to S750F in human AGO1) in C. elegans alg-1 (Fig. 1A) (10). We thus reasoned that modeling AGO syndromes mutations in a homologous C. elegans AGO could facilitate assessing the effects of the mutations on miRNA biogenesis and miRNA/AGO functionality.

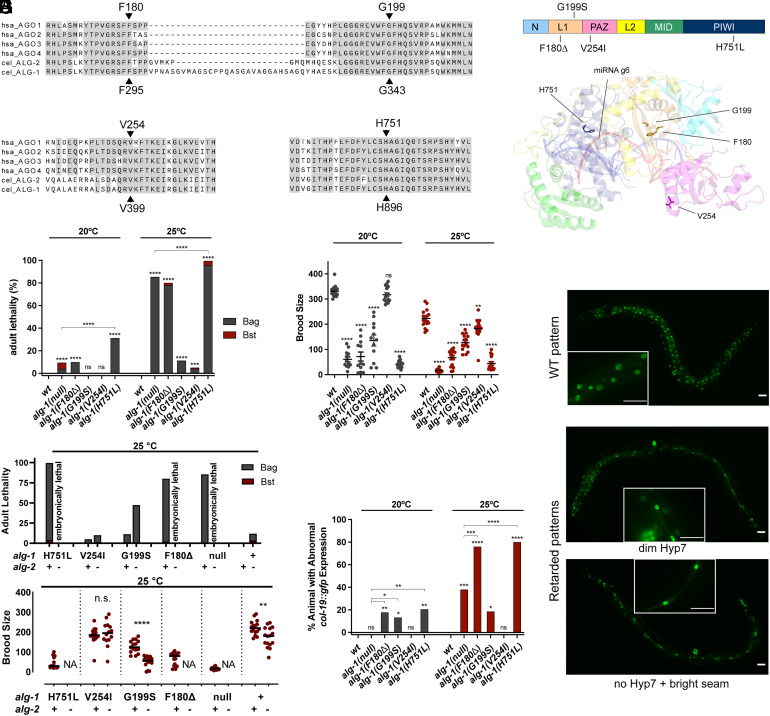

Fig. 1.

C. elegans alg-1 NDD mutants display alg-1 loss-of-function and antimorphic phenotypes. (A) Protein sequence alignment of the regions surrounding the amino acids corresponding to human AGO1 F180, G199, V254, and H751. Alignment includes human AGO1-4, C. elegans ALG-1 and ALG-2. The ALG-1 amino acid numbers indicated at the Bottom correspond to C. elegans ALG-1 isoform a (ALG-1a). (B) ALG-1 domain organization. The unstructured, non-conserved sequence at the N-terminus (aa1-187) of cel-ALG-1a is not shown. (C) AGO2::miRNA::target complex structure (PDB::6MFR) highlighting AGO1 F180, G199, V254, and H751 residues (20). Side chains of the above amino acids are presented as sticks. (D and E) Quantification of vulval defect phenotypes, represented by the lethality of young adult hermaphrodites (D) and reduction in the number of progeny per animal (E). Lethality is categorized as vulval integrity defect (lethality by bursting, Bst) or egg laying defect (lethality by matricide, Bag). (F) Quantification of vulva integrity defect of the alg-1 NDD mutations with alg-2(+) or alg-2(null) genetic backgrounds. (G) Representative fluorescent images of col-19::gfp expression patterns from WT (top) and mutants alg-1(G199S) (middle) or alg-1(H751L) (bottom) animals. (Scale bar, 25 µm.) (H) Quantification of col-19::gfp expression phenotypes. The statistical significance is analyzed by Fisher’s test (lethality and abnormal col-19:gfp expression) and Student t test (brood size).

Here, we reproduced four human AGO1 mutations (F180Δ, G199S, V254I, H751L) in the homologous C. elegans alg-1 gene using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing. We refer to the corresponding C. elegans mutations as alg-1 NDD mutations. The alg-1 NDD mutations resulted in a range of developmental phenotypes consistent with alg-1 loss of function, and for two of the mutations, the phenotypes are stronger than the homozygous alg-1(null). This antimorphic character of the stronger alg-1 NDD mutations suggests that the mutant ALG-1 protein interferes or competes with the functions of paralogous AGO proteins (nominally ALG-2 in C. elegans). alg-1 NDD mutations affected the overall profile of mature miRNAs and the profile of miRNAs associated with ALG-1 protein, including altered selection of miRNA guide/passenger strands. The mutations also caused global gene expression perturbations in terms of mRNA levels and mRNA translational status, including substantial differences in the de-repression modes of miRNA targets for certain mutations. Interestingly, the set of alg-1 NDD mutations examined here exhibit distinguishable allele-specific perturbations in C. elegans miRNA function, miRNA profiles, and gene expression, suggesting that these alg-1 NDD mutations cause distinct alterations in ALG-1 functionality. Lastly, we show that many of the genes whose expression is perturbed by the alg-1 NDD mutations are known to have human homologs whose dysfunction is known to cause NDD. Our results demonstrate that modeling human AGO1 mutations in a C. elegans AGO can advance the understanding of fundamental AGO functions and provide insights into the conservation of miRNA-mediated regulatory mechanisms.

Results

AGO Syndrome Mutations Disrupt C. elegans ALG-1 Function.

We selected four human AGO1 AGO syndrome mutations (F180Δ, G199S, V254I, H751L) to model in C. elegans ALG-1. Each of these mutations had been identified in multiple patients, with F180Δ, G199S, and V254I identified in multiple families (18). The F180Δ and G199S mutations were also identified at homologous positions of human AGO2, causing NDD with ID and ASD symptoms (19). The human AGO1 F180, G199, V254, and H751 amino acids are conserved among the four miRNA-associated AGO proteins in humans (AGO1-AGO4), as well as their two C. elegans orthologs (ALG-1 and ALG-2) (Fig. 1A). F180 and G199 are in the L1 hinge domain, which lies between the MID-PIWI lobe and the PAZ-N lobe (Fig. 1 B and C). V254 is in the PAZ domain with the side-chain exposed to the surface of AGO protein and is distant from the PAZ-N channel where the 3′ non-seed duplex is located (Fig. 1 B and C). H751 resides in the PIWI domain, near the MID-PIWI channel where the miRNA seed duplexes with the target (Figs. 1B).

To explore how the alg-1 NDD mutations affect miRNA function, we used CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing to generate four C. elegans mutant strains, each containing a mutation identical to F180Δ, G199S, V254I, or H751L at the corresponding amino acids of C. elegans ALG-1. Here, we refer to each C. elegans ALG-1 mutation using the human AGO1 addresses of the corresponding amino acids (Fig. 1A). The respective C. elegans alg-1 NDD mutants are alg-1(ma447, F180Δ), alg-1(ma443, G199S), alg-1(zen25, V254I), and alg-1(zen18, H751L).

C. elegans homozygous for each of the four alg-1 NDD mutations exhibit varying degrees of developmental defects (Fig. 1 D–H). alg-1(F180Δ) and alg-1(H751L) hermaphrodites exhibit strong adult lethality (Fig. 1D), caused by impaired egg laying (retention of embryos and eventual matricide by the progeny that hatch in utero) and/or rupturing of the cuticle at the vulva, which kills the adult outright before reproduction. These phenotypes are presumed to reflect defective vulval development owing to decreased activity of certain miRNAs known to be critical for normal vulva development (5). In accordance with their underlying egg retention and/or vulva bursting defects, alg-1 NDD mutant hermaphrodites produced a dramatically reduced number of progeny (Fig. 1E). The penetrance of the adult lethality and reduced progeny phenotypes for the H751L and F180Δ mutants were at least as strong as for alg-1(tm492, null) mutants (Fig. 1 D and E). alg-1(G199S) animals exhibited moderate penetrance of vulval defects and reduced progeny, and alg-1(V254I) mutants exhibited relatively mild and temperature-dependent expression of these phenotypes (Fig. 1 D and E). Thus, based on phenotypic similarity with alg-1 null, we conclude that the F180Δ, G199S, V254I, and H751L mutations cause varying degrees of ALG-1 loss-of-function (5, 10).

The alg-1 NDD Mutations Synergize with the alg-2(null).

Genes for miRNA-related AGO exhibit genetic redundancy, both for the human AGO family (AGO1-AGO4) and for C. elegans alg-1 and alg-2 (10, 21). To test for redundancy between the alg-1 NDD mutations and alg-2, we crossed each mutation into the alg-2(ok304, null) background. The alg-1(F180Δ); alg-2(null) and alg-1(H751); alg-2(null) mutants exhibited embryonic lethality, consistent with severe reduction of both alg-1 and alg-2 functions (5) (Fig. 1F). alg-1(G199S); alg-2(null) mutants showed stronger adult lethality and reduced progeny phenotypes compared to alg-1(G199S). Similarly, alg-1(V254I); alg-2(null) animals exhibited increased adult lethality compared to alg-1(V254I) (Fig. 1F). Since the phenotypes of all four alg-1 NDD mutations were exacerbated in the alg-2 null background, we conclude that the alg-1 NDD mutations disrupt alg-1 function.

alg-1(F180Δ) and alg-1(H751L) Mutations Are Antimorphic in Regulating Seam Cell Differentiation.

In C. elegans, lateral hypodermal development involves a stem cell lineage wherein the stem cells (seam cells) execute asymmetric divisions at each larval stage, producing one daughter cell that differentiates and joins the hypodermal syncytium (Hyp7) and another daughter cell that remains a stem cell (22). At the final larval molt, seam cells cease division, and all hypodermal cells (seam and Hyp7) express the adult-specific hypodermal gene col-19 (23). miRNAs are critical for controlling the timing of this larval-to-adult hypodermal cell fate transition (2, 24, 25). Accordingly, mutations that disrupt these miRNAs or the miRNA machinery can cause the failure of hypodermal cells to properly express adult fates, as reported by the expression of the col-19::gfp transgene (10) (Fig. 1G).

We found that alg-1(F180Δ), alg-1(H751L), and alg-1(G199S) adults exhibited reduced or absent col-19::gfp expression in Hyp7 cells, indicating that the alg-1 NDD mutations impair heterochronic pathway miRNA activity (Fig. 1H). Strikingly, the heterochronic phenotypes of the alg-1(H751) (80.7%) and alg-1(F180Δ) mutants (76.6%) were significantly stronger than the alg-1(null) mutant (38.6%) (Fig. 1H), indicating that the alg-1(F180Δ) and alg-1(H751L) mutations are antimorphic; these mutations do not simply inactivate the ALG-1 protein, but alter ALG-1 function such that the mutant protein inappropriately interferes with the function of ALG-2. The antimorphic behavior of the alg-1(F180Δ) and alg-1(H751L) mutations is reminiscent of other C. elegans alg-1 alleles that were identified in forward screens for heterochronic mutants and that are likewise point mutations at evolutionarily conserved amino acids (10).

Interestingly, in animals carrying an alg-1 NDD mutation heterozygous to a wildtype alg-1 allele, no lethality or abnormal col-19::gfp expression was observed (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 A and B), nor was the number of progeny appreciably reduced (SI Appendix, Fig. S1C). This indicates that the alg-1 NDD mutations, like the previously described alg-1 antimorphic mutations (10), appear to be fully recessive or only weakly semi-dominant. Thus, the negative activity of the alg-1 NDD mutations in C. elegans may be dosage dependent or complemented by a WT allele.

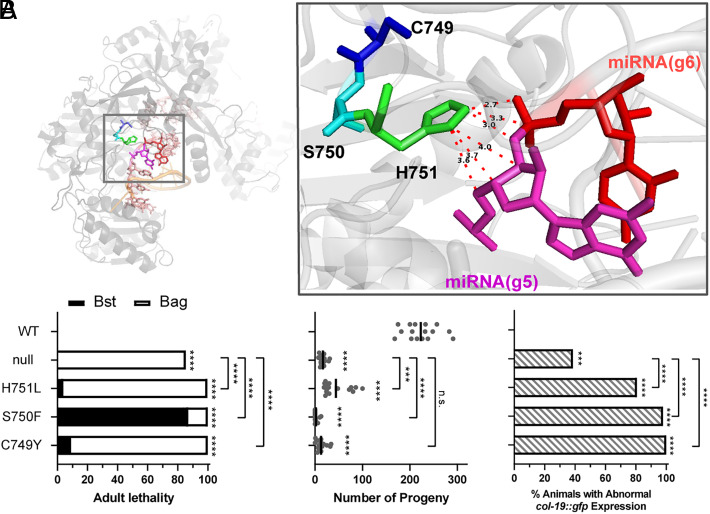

The C749-S750-H751 Tripeptide Is Critical for ALG-1 Function.

One of the previously described C. elegans alg-1 antimorphic mutations, alg-1(ma192), is a serine-to-phenylalanine point mutation at the amino acid homologous to S750 of AGO1, which is adjacent to the H751L AGO syndrome mutation. Analysis of other AGO syndrome AGO2 mutations revealed cases of a cysteine-to-tyrosine change in position homologous to C749 of AGO1 (19). It is striking that independent genetic screens in human and C. elegans have recovered mutations at three adjacent AGO amino acids (C749Y, S750F, and H751L) that cause particularly potent disruptions of AGO function, indicating that this region of AGO and these amino acids (Fig. 2A) are critical for function and may affect the activity of the protein similarly (Fig. 2). To assess the effects of the C749Y mutation in C. elegans, we introduced the C749Y mutation into alg-1 by CRISPR/Cas9. Like the alg-1(S750F) and alg-1(H751L) mutants, alg-1(C749Y) animals exhibited adult lethality, reduced number of progeny, and abnormal col-19::gfp expression (Fig. 2B). alg-1(C749Y), alg-1(S750F), and alg-1(H751L) mutants all exhibited a col-19::gfp expression defects more severe than the alg-1(null) mutant, suggesting that all these three mutations confer antimorphic activity to ALG-1.

Fig. 2.

The C749-S750-H751 subregion is functionally critical to ALG-1. (A) Visualization of the human AGO2 side-chains equivalent to human AGO1 C749, S750, and H751 in AGO2::miRNA::target complex (PDB:: 6MDZ) (20). Dashed lines and numbers indicate distances between adjacent atoms (Å). (B) Lethality, brood size, and abnormal col-19::gfp expression phenotypes scored at 25 °C.

The structure of co-crystalized human AGO2::miRNA::target ternary complex shows that C749-S750-H751 residues are positioned close to the backbone of the miRNA at the g5-g6 seed nucleotides (Fig. 2A) (20, 26). The imidazole group of the H751 side chain is positioned close to the miRNA backbone, suggesting that the side-chain of H751 directly contacts the miRNA seed region via hydrogen bonds and electrostatic force (27) (Fig. 2A).

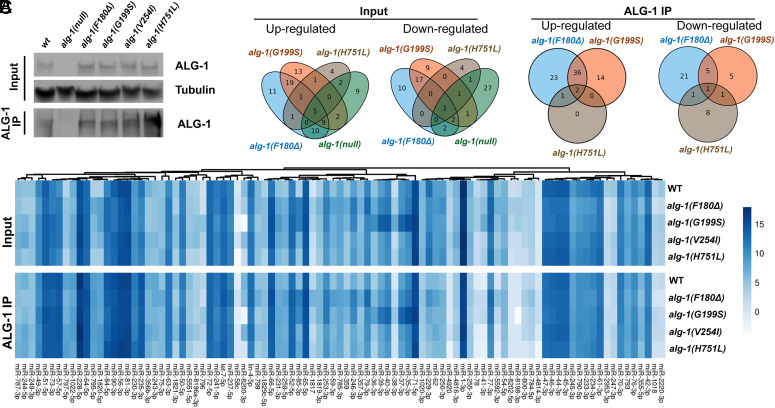

The alg-1 NDD Mutations Disrupt Total miRNA Profiles and the Profiles of miRNAs Associated with ALG-1.

Previous studies of C. elegans alg-1 antimorphic mutations reported that like alg-1(null) mutants, alg-1 antimorphic mutants exhibit global abnormalities in miRNA biogenesis, but do not appreciably affect ALG-1 protein levels (10, 28). Likewise, the levels of the ALG-1 NDD mutant proteins did not significantly differ from WT ALG-1 (Fig. 3A), and the alg-1 NDD mutations caused perturbations in the expression of C. elegans miRNAs. We performed small RNA sequencing (sRNA-seq) of total RNA extracted from L4 larvae and analyzed the expression levels of guide strands for the 259 relatively abundant (reads per million (RPM) > 5) miRNAs (Fig. 3 B and C, SI Appendix, Figs. S2 and S3, and Dataset S1). The F180Δ and G199S mutations caused a remarkable disturbance of total miRNA profiles, with 87 and 75 miRNAs, respectively, perturbed more than twofold (FDR < 0.05) (Fig. 3 B and C). Only one miRNA was changed in level with statistical significance in the V254I mutant (SI Appendix, Fig. S3), which is consistent with the weak phenotypes of alg-1(V254I) (Fig. 1 D–H). Surprisingly, only 21 miRNAs were significantly perturbed in the H751L mutants (Fig. 3 B and C), which is in sharp contrast to the strong phenotypes of H751L mutant animals.

Fig. 3.

The alg-1 NDD mutations cause allele-specific disruptions of miRNA expression and altered profiles of miRNAs associated with ALG-1. (A) Western blotting for ALG-1 protein in input and ALG-1 immunoprecipitated samples of wildtype, alg-1(null), and alg-1 NDD mutants. (B) Venn diagrams showing numbers of miRNAs with statistically significant up/down-regulated levels (Fold change > 2; FDR < 0.05). Results for alg-1(V254I) mutant are not shown because no significant perturbation was observed in ALG-1(IP), with a single miRNA up-regulated in alg-1(V254I) input (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 and Dataset S1). (C) Heatmap showing the levels of abundant (≥10 RPM) miRNAs in input and ALG-1 IP from wildtype and alg-1 NDD mutants. Data are shown as log2(RPM).

To determine whether the alg-1 NDD mutations affect the profiles of miRNAs that associate with the mutant ALG-1 compared to WT ALG-1, we performed ALG-1 immunoprecipitation (IP) using anti-ALG-1 polyclonal antibody and sequenced the co-immuno-precipitated miRNAs (Fig. 3A and SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). For the F180Δ and G199S mutants, 90 and 64 miRNAs, respectively, showed significantly altered association with the mutant ALG-1, while fewer miRNAs were altered in their association with H751L or V254I (14 and 0, respectively) (Fig. 3 B and C, SI Appendix, Figs. S2 C and D and S3, and Dataset S1). Many of the miRNAs disrupted in the NDD mutants were distinct from those affected in the alg-1 null (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B), suggesting that the miRNA perturbations in the NDD mutants are not simply caused by reduced ALG-1 function. Moreover, while some miRNAs were perturbed in multiple NDD mutants, certain miRNAs were uniquely perturbed in individual mutants (Fig. 3B), suggesting that different NDD mutations cause qualitatively distinct disruptions of AGO protein function (Fig. 3B).

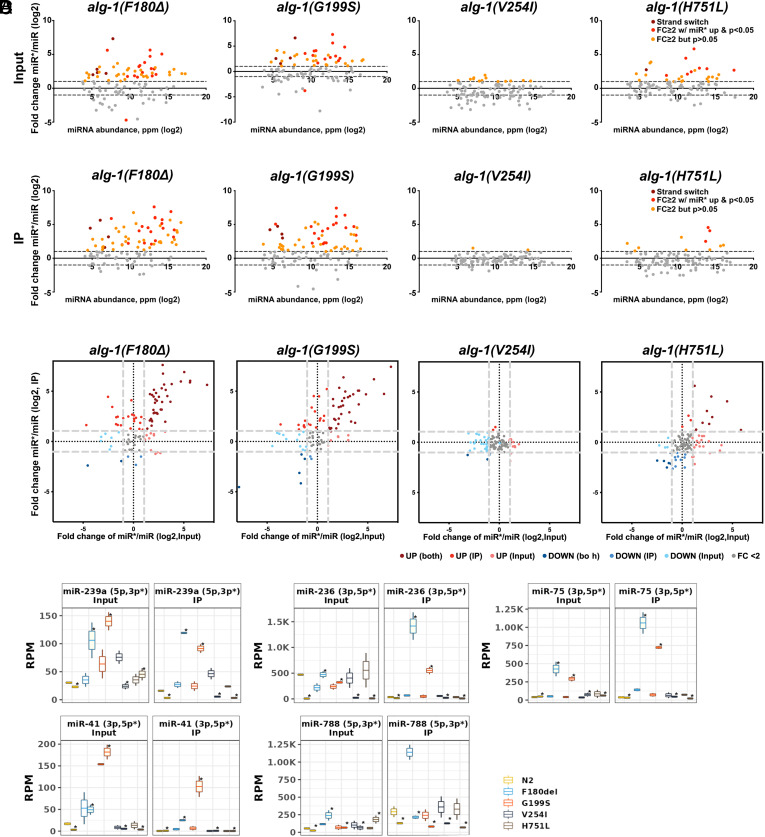

The alg-1 NDD Mutations Alter Guide/Passenger Strand Ratios.

We reported previously that the disruptions in miRNA biogenesis caused by C. elegans alg-1 antimorphic mutations included altering relative abundances of guide (miR) and passenger strands (miR*) for particular miRNAs (10, 28) (Fig. 4A). Similarly, the F180Δ, G199S and H751L alg-1 NDD mutants exhibited altered miR*/miR ratios (Fig. 4 B–D). An altered miR/miR* ratio could reflect altered guide/passenger strand selection and/or failure to dispose of the passenger strand. Consistent with altered guide strand selection for certain cases, we observed that some individual miRNAs exhibited an increased expression of the miR* strand accompanied by a decreased expression of the miR strand in the alg-1 NDD mutants compared to the WT (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

alg-1 NDD mutations lead to altered guide/passenger (miR/miR*) ratios. (A and B) Changes in miR/miR* ratio in input (B) and ALG-1 IP (C). log2FC miR*/miR ratio in wildtype versus mutant animals (Y-axis) is plotted against miRNA abundance in wildtype (X-axis). Burgundy dots represent miRNAs with reversed miRNA strand bias (miR* > miR), red dots represent miRNAs whose miR* strands were upregulated ≥twofold with P ≤ 0.05, and orange dots represent miRNAs whose miR* strands were upregulated ≥twofold but did not reach statistical significance. Dashed lines, |log2FC| = 1. (C) miRNA fold change comparison between input and ALG-1 IP. miRNAs with |FC| > 2 and P < 0.05 are color-coded to indicate miRNA up- or down- regulation in input and ALG-1 IP, and input or ALG-1 IP only. (D) miRNAs that exhibited reversed miRNA strand bias in input and/or ALG-1 IP. miRNA* are marked with an asterisk(*).

The alg-1 NDD Mutations Cause Allele-Specific Translatome-Wide Perturbations in Gene Expression.

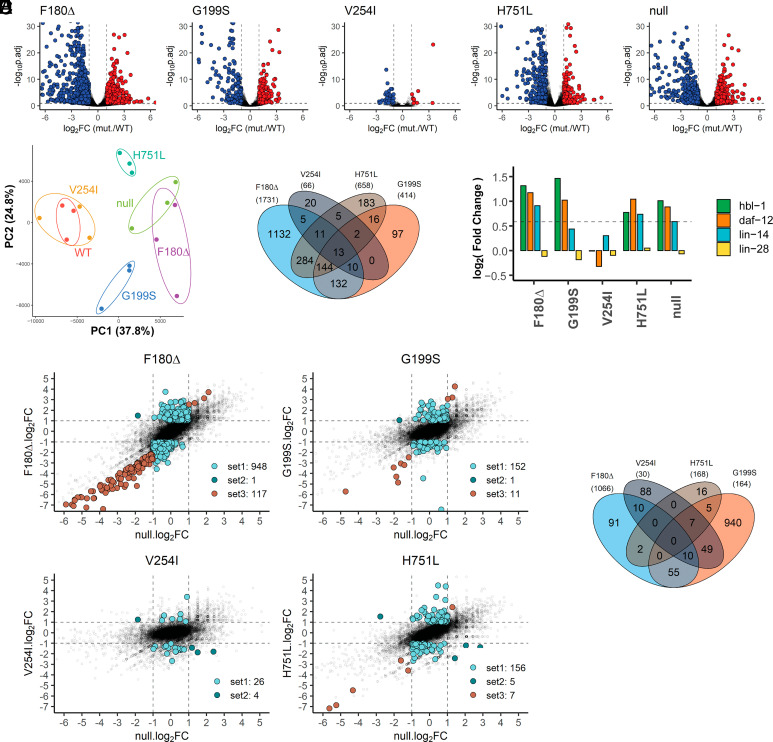

Mutations that alter ALG-1 function are expected to disrupt gene expression profiles due to the de-repression of protein production from mRNAs directly targeted by miRNAs, combined with indirect perturbation of genes downstream of dysregulated miRNA targets. To assess how the NDD mutations affect gene expression, we used ribosome profiling (Ribo-seq) (29) to profile genome-wide ribosome occupancy of mRNAs in extracts of late L4 animals for the WT, null, and NDD mutants. All the mutants exhibited some degree of translatome perturbation compared to the WT (Fig. 5A and Dataset S2). The number of genes with statistically significant perturbations in ribosome protected fragment (RPF) counts (|FC| > 2 and p.adj < 0.1) ranged from 66 genes (V254I) to 1,731 genes (F180Δ) (Fig. 5A). Changes were observed for abundantly and lowly expressed genes (SI Appendix, Fig. S4F). PCA analysis suggests that each NDD mutant exhibits a distinctively perturbed translatome (Fig. 5B), and the sets of genes perturbed in the weaker mutants (e.g., V254I) were not simply a subset of the sets perturbed in the stronger mutants (Fig. 5C) suggesting that each mutation distinctly impairs ALG-1 function.

Fig. 5.

alg-1 NDD mutations lead to strong translatome perturbations in C. elegans. (A) Volcano plots of the ribosome protected fragments (RPF) detected in ribosome profiling of alg-1 NDD late L4 larvae. Colored dots represent perturbed genes with statistical significance (|log2FC| > 1.5, p.adj < 0.1). Also see Dataset S2. (B) Principal component analysis of translatomes of alg-1 NDD and alg-1 null. Identical color points indicate biological replication. (C) Venn diagram for the total perturbed genes in the alg-1 NDD mutants. (D) RPFs of heterochronic genes whose gain-of-function mutations cause heterochronic phenotypes and have been genetically confirmed to be C. elegans miRNA targets. (E) Visualization of set1-set3 antimorphic perturbed (amp) genes. For each gene, the log2FC of the null/WT is plotted on the x-axis, and the log2FC of alg-1 NDD mutant/WT is plotted on the y-axis. Solid dots indicate perturbed genes with statistical significance (|FC| > 1.5, p.adj < 0.1). See also Dataset S3. (F) Venn diagrams of set1-set3 amp genes in the alg-1 NDD mutants.

The Major Heterochronic Genes Were Translationally Perturbed in alg-1 NDD Mutants.

The alg-1 NDD mutants exhibit adult lethality and col-19::gfp expression defects in the hypodermis, consistent with disruptions in miRNA-regulated heterochronic pathway function. Genes translationally up-regulated in alg-1 NDD mutants were enriched for genes expressed in hypodermal seam cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S4E), including daf-12, hbl-1, and lin-14 (Fig. 5D). Gain-of-function mutations in these genes have been reported to cause heterochronic phenotypes, and these genes have been genetically confirmed to be miRNA targets (2, 23, 30–33). Translation of daf-12 and hbl-1 was up-regulated in the F180Δ, G199S, and H751L mutants, and lin-14 was up-regulated in the F180Δ and H751L mutants (Fig. 5D), suggesting that the abnormal ALG-1 NDD function causes over-expression of these heterochronic genes and leads to the developmental phenotypes in the alg-1 NDD mutants. Major heterochronic genes were not significantly perturbed in the V254I mutant, consistent with the mild phenotypes of V254I animals.

The alg-1 NDD Mutations Cause Antimorphic Translatome Perturbations.

The sets of translationally perturbed genes in alg-1 NDD mutants partially overlap with the genes perturbed in alg-1 null (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A), but also included changes not observed in the alg-1(null) (Fig. 5E, set1, SI Appendix, Fig. S4B). Moreover, some genes were up-regulated in alg-1 NDD mutants but were down-regulated in the alg-1 null mutant (Fig. 5E, set2, SI Appendix, Fig. S4C). Other genes were perturbed in both the alg-1 NDD mutants and alg-1 null mutants but with greater perturbation (|ΔFC| > 2) in the alg-1 NDD mutants than in the null mutant (Fig. 5E, set3, SI Appendix, Fig. S4D). These genes that were distinctly affected in alg-1 NDD animals versus alg-1 null animals (sets 1, 2, 3) are referred to as antimorphic perturbed (amp) genes (Dataset S3). For the F180Δ, G199S, and H751L mutations, the occurrence of the amp gene perturbations in excess of those in alg-1 null is consistent with the observation that these mutations cause developmental phenotypes stronger than alg-1 null (Fig. 1 D–H). Even the weakest mutation V254I, which displayed negligible visible phenotypes, exhibited amp genes of the set1 and set2 classes (Fig. 5E), suggesting that all four mutations may confer an antimorphic impact on the ALG-1 protein.

The Translatome Disruptions in alg-1 NDD Mutants Reflect Distinct Profiles of miRNA Perturbations.

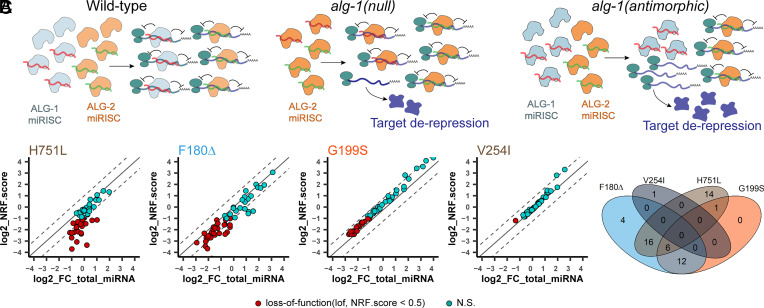

The relatively mild perturbations of miRNA levels in the total miRNA and ALG-1 IP profiles in alg-1(H751L) larvae stand in striking contrast to the severity of this mutant’s developmental and translatome phenotypes: alg-1(H751L) causes stronger developmental phenotypes and translatome perturbations than alg-1(G199S) (Figs. 1 D–F and 5 A and B), while the number of miRNAs whose abundance or ALG-1 association is altered by alg-1(H751L) is far less than by alg-1(G199S) (Fig. 3 B and C). This suggests that the stronger phenotype of alg-1(H751L) reflects a substantial loss of miRNA function that is not reflected by change in miRNA levels. We hypothesized that the mutant ALG-1H751L protein is relatively normal for miRNA biogenesis and association but is defective in one or more subsequent functions in miRISC maturation or function. By binding its normal cohort of miRNAs, the mutant ALG-1H751L protein, which is incapable of target repression, sequesters in non-functional miRISC a large set of miRNAs that would associate with ALG-2 if ALG-1 were absent (Fig. 6A). For other alg-1 NDD mutations that substantially affect the levels of more miRNAs, the overall phenotype could reflect a combination of both altered miRNA levels and sequestration of miRNAs in defective miRISC.

Fig. 6.

Antimorphic ALG-1 NDD miRISC sequester miRNAs into non-functional complexes, leading to a greater miRNA loss-of-function than in the absence of ALG-1. (A) Illustrative models of wild-type, alg-1(null) and ALG-1 NDD miRISC activity, with ALG-1 NDD miRISC sequestering functional miRNAs away from the ALG-2 miRISC. (B) Scatter plots of the total miRNA fold change (FC) versus NRF.score in the alg-1 NDD mutants. Dashed lines indicate two-fold differences between total miRNA FC and NRF.score. (C) Venn diagram of the miRNAs with lof NRF.score (<0.5) in the alg-1 NDD mutants. See also SI Appendix, Dataset S4 and Fig. S5.

According to the above model, each of the alg-1 NDD mutations causes a certain amount of net loss-of-function (lof) for specific miRNAs, resulting from a combination of two component effects: the reduction in the overall level of that miRNA and the sequestration of that miRNA into non-functional miRISC. To capture these two components in a single numerical estimate of lof for individual miRNAs in each alg-1 NDD mutant, we derived a net repressive functionality score (NRF.score; see Materials and Methods), which represents the proportional target repressive functionality of that miRNA in the mutant compared to the WT (NRF.score of WT = 1; NRF.score of null = 0). The NRF.score captures the contribution from reduction in miRNA level by incorporating the fold change of a given miRNA in the mutant input sample versus WT input. The NRF.score captures the contribution from sequestration of miRNAs in defective ALG-1 miRISC by incorporating two values: 1) the enrichment of the miRNA co-IP with ALG-1 in the mutant compared to the WT, and 2) the intrinsic function of the mutant ALG-1 protein, defined by the penetrance of the lethality of the alg-1 mutant in the alg-2(null) genetic background (Fig. 1F).

We calculated the NRF.score of the 76 most abundant miRNAs (minimum RPM > 15) and found that the numbers of miRNAs with NRF.score below an arbitrary threshold for lof (NRF.score < 0.5) were 44 for H751L, 45 for F180Δ, 22 for G199S, and 1 for V254I (Fig. 6 B–C, SI Appendix, Fig. S5 and Dataset S4). Notably, by modeling overall miRNA functionality as sequestration in combination with perturbed levels, the NRF.score identified a larger number of miRNAs functionally affected by the H751L mutation, potentially reconciling the disconnection between the strong phenotype of alg-1(H751L) compared to its mild effects on miRNA abundances.

To test whether modeling miRNA function with NRF.score is consistent with the observed translatome disruptions, we identified sets of disrupted miRNA targets for each mutant (145 for H751L, 396 for F180Δ, 81 for G199S, and none for V254I) that were translationally up-regulated and that also contain predicted target sites for the miRNAs with a lof NRF.score in that mutant. For the H751L, F180Δ, and G199S mutants, the targets of lof miRNAs defined by NRF.score were statistically enriched among all translationally up-regulated genes, compared to the targets of miRNAs that were reduced in terms of abundance only (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). These results support the model that the expression of mutant ALG-1 NDD protein in C. elegans can cause miRNA loss-of-function by the combined effects of disrupted miRNA biogenesis and sequestration of miRNAs in defective ALG-1 miRISC.

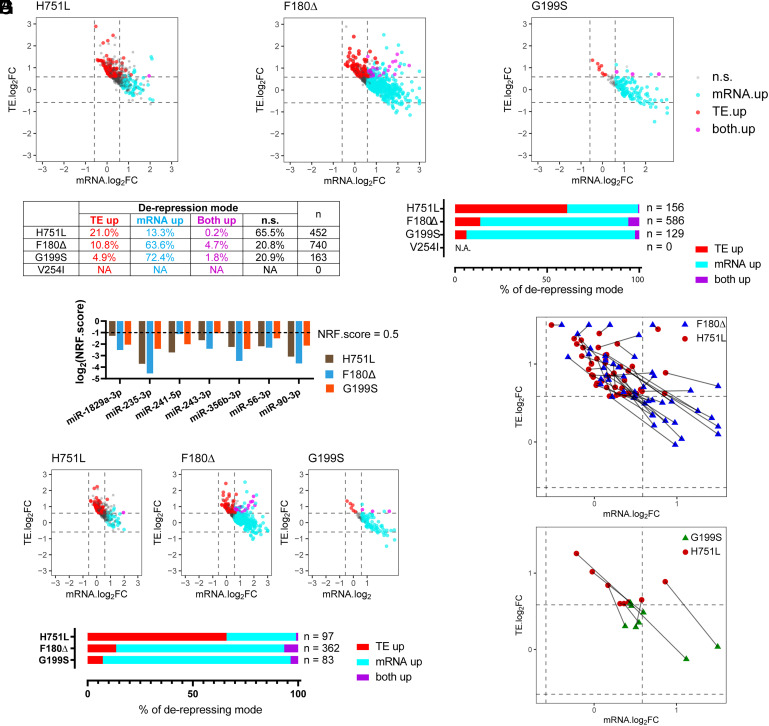

The alg-1 NDD Mutations Have Distinct Impacts on Translational Repression and mRNA Abundance of Targets.

miRNAs can repress target mRNAs through translational inhibition and/or mRNA destabilization, such that impaired miRNA activity can manifest as increased translational efficiency (TE) and/or increased abundance of target mRNAs (34, 35). To assess how the alg-1 NDD mutations affect these modes of target repression, we analyzed our ribosome profiling results in conjunction with RNA-seq analysis of total mRNA (Dataset S2). For the RNA-seq, we employed ribosomal RNA depletion for mRNA enrichment to ensure the quantitative recovery of all mRNAs regardless of poly(A) status (36). The TE of each transcript was calculated by normalizing its RPF values to its mRNA abundance (33). We evaluated the TE and mRNA abundance of genes that were up-regulated in the translatome and that also contain predicted target sites for miRNAs with a lof NRF.score in each mutant (Fig. 7A). Genes were categorized into three de-repression modes: a) genes that exhibit statistically significant up-regulation in TE only (“TE up”); b) genes that exhibit statistically significant up-regulation in mRNA abundance only (“mRNA up”); c) genes that exhibit statistically significant up-regulation in both TE and mRNA abundance (“both up”) (Fig. 7B). In the F180Δ, G199S, and H751L mutants, 79.2%, 79.1%, and 34.5%, respectively, of the translationally up-regulated targets of lof miRNAs could be classified as exhibiting a statistically significant increase in TE and/or mRNA abundance (TE up, mRNA up or both up) (Fig. 7B). Interestingly, for the H751L mutant, the majority (61.0%) were de-repressed with increased TE without a significant change of mRNA abundance (TE up), while only 13.7% and 6.2% for the F180Δ and G199S mutants were de-repressed via TE up mode (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 7.

The alg-1 NDD mutations have distinct impacts on gene target repressing modes. (A) Fold changes of mRNA abundance and TE of genes that are significantly up-regulated and contain target sites of miRNAs with lof NRF.score (<0.5). Dots indicate genes with significantly increased mRNA abundance (Cyan, |FC| > 1.5, p.adj < 0.1 by DEseq2), TE (Red, |FC| > 1.5, P < 0.1 by Student t test), or both TE and mRNA abundance (Magenta). (B) Summary of de-repression modes of genes that are translationally up-regulated and contain target sites for miRNAs with lof NRF.score. (C) Distribution of de-repression modes of genes in (B) with significantly up-regulated TE and/or significantly up-regulated mRNA abundance. (D) NRF.score of miRNAs that are down-regulated with statistical significance in both F180Δ and H751L mutants. (E) Fold changes of mRNA abundance and TE of genes that are translationally up-regulated and contain target sites of miRNAs in (D). (F) Distribution of the de-repression modes of the genes in E with significantly up-regulated TE and/or significantly up-regulated mRNA abundance. (G) Fold changes of mRNA abundance and TE of genes that contain target sites of miRNAs in (D) and were simultaneously perturbed in both alg-1(F180Δ) and alg-1(H751L) or both alg-1(G199S) and alg-1(H751L) mutants.

The TE disruption bias associated with H751L could indicate that different ALG-1 NDD mutations can have selective disruptions of intrinsic functionalities of the ALG-1 protein, leading to distinct effects on the downstream target repression mechanism. However, an alternative explanation could be that the H751L mutation happens to preferentially disable the activity of a subset of miRNAs that are enriched for those with TE-regulated targets. To distinguish between these possibilities, we selected the set of miRNAs with a lof NRF.score in F180Δ, G199S, and H751L mutants and analyzed the target de-repression of these commonly affected miRNAs (Fig. 7D). We found that the targets of the commonly affected miRNAs showed a similar TE-only enrichment in the H751L mutant compared to F180Δ and G199S (Fig. 7 E and F).

Strikingly, the TE de-repression bias of H751L applies even to specific target genes. We analyzed the subset of 46 genes with TE up de-repression mode in the H751L mutant and compared the de-repression modes of these identical genes in the F180Δ or G199S mutants. We found 44 of the 46 genes were also de-repressed in F180Δ, and 25 out of those 44 genes exhibited a shift of the mode of de-repression from H751L to F180Δ. Similarly, 8 of the 46 genes de-repressed in H751L were also up-regulated in G199S, and all 8 genes exhibited a mode shift from H751L to G199S (Fig. 7G). This suggests that the distinction in the target de-repression mode associated with individual NDD mutations is related to ALG-1 protein function, and not an indirect effect of selective disruption of unique sets of miRNAs or targets. We conclude that the H751L mutation may directly impair the target repression functionality of ALG-1 in a way distinct from the F180Δ /G199S mutations, perhaps reflecting discrete functions of the mutated amino acids or different roles in target repression mode for the PIWI and L1 domains where these mutations reside.

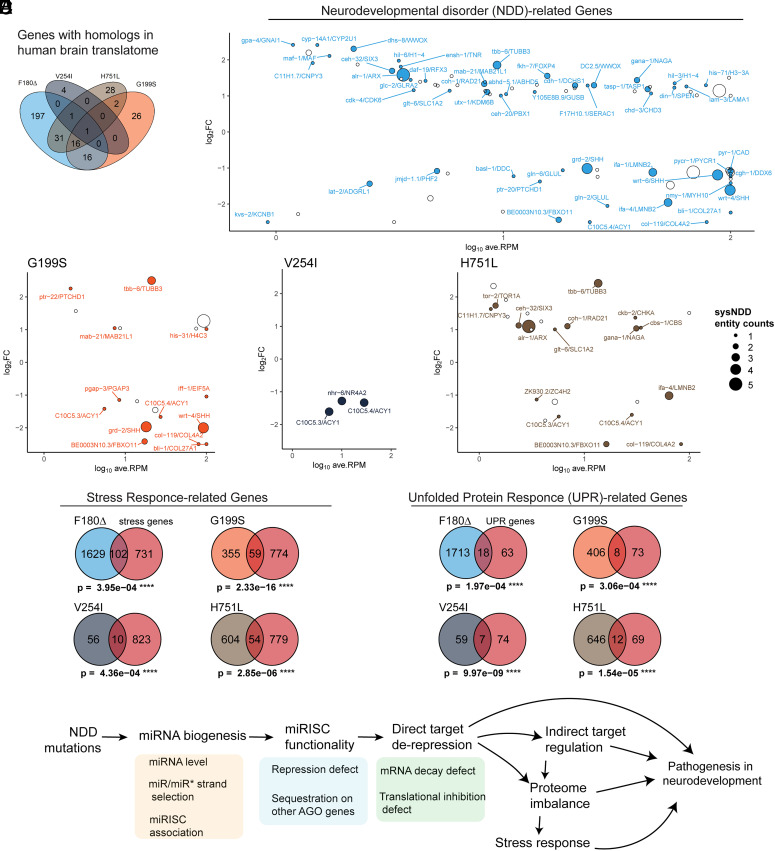

The alg-1 NDD Mutations Perturb the Expression of Genes with Human Orthologs Expressed in Brain Translatomes And/or Related to Human NDD.

The occurrence of the human AGO1/2 mutations in human NDD patients raises the question of whether the perturbed genes in C. elegans NDD mutants include genes whose human homologs could be related to the pathogenesis of NDD. We first identified the translationally perturbed genes in the C. elegans NDD mutants that have been documented to be associated with neuronal phenotype in C. elegans, or those have been reported to be expressed in C. elegans nervous system (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 and Dataset S5) (37, 38). We next examined the homology between the perturbed genes in C. elegans alg-1 NDD mutants and the genes translationally expressed in the human central nervous system (SI Appendix, Fig. S7 and Dataset S6) (37, 39). We found that among the C. elegans genes that were translationally perturbed in the alg-1 F180Δ, G199S, V254I, and H751L mutants, 262, 61, 6, and 79 genes, respectively, have human orthologs which are expressed in human brain translatomes (Fig. 8A and SI Appendix, Fig. S7A). Of these genes, 55%, 34%, 0%, and 58%, respectively, have target sites for the miRNAs with lof NRF.score (SI Appendix, Fig. S7 B and C). Of the neuronally expressed human/worm homologous genes disrupted in C. elegans alg-1 NDD mutants, 52, 13, 3, and 16 genes, respectively, have been reported to be genetically associated with human NDDs with ID symptoms and have definitive sysNDD entries (37, 40) (Fig. 8B and Dataset S6). This suggests that these genes could be among those whose dysregulation could contribute to clinical manifestations of NDD. Interestingly, the C. elegans ADAR1 homologous gene adr-1 is down-regulated in the F180Δ, G199S, H751L, and alg-1(null) mutants, suggesting that altered A-to-I RNA editing may contribute to the perturbation of translatome and miRNA profiles (SI Appendix, Fig. S8).

Fig. 8.

The alg-1 NDD mutations can perturb genes with human orthologs expressed in the brain and human orthologs related to NDD. (A) Venn diagram for genes that are translationally up-regulated in C.elegans and have human orthologs expressed in brain translatome (39). (B) MA plots for translationally perturbed genes with sysNDD curated human homologs (40). Solid and text labeled dots indicate genes that contain definitive sysNDD entity. Dot radius indicates the sysNDD entity counts. See also Dataset S5. (C and D) Hypergeometric tests for enrichment of stress-related genes (A) and unfolded protein response (UPR) (B) in translationally up-regulated genes in the alg-1 NDD mutants (41). (E) Summary of possible contributions of the alg-1/AGO1 NDD mutations to the pathogenesis of NDD.

The Translatome Perturbation in the alg-1 NDD Mutants May Trigger Stress-Related Responses due to Proteome Imbalance.

Protein homeostasis (proteostasis) is tightly controlled and critical for normal cellular physiology. An imbalance in the proteome induced by genetic or other perturbations can impair proteostasis and contribute to pathogenesis (42, 43). In normal cells, proteome imbalance elicits the activation of stress response pathways to restore proteostasis (44, 45). In the alg-1 NDD mutants, many protein-coding genes were translationally perturbed, especially in the F180Δ and H751L mutants (9.0% of total protein-coding genes for F180Δ and 3.4% for H751L). Consistent with proteome imbalance from translatome disruptions, in all four alg-1 NDD mutants, stress-related genes were significantly enriched in the translationally up-regulated genes (Fig. 8C and SI Appendix, Fig. S9A)(41). The F180Δ, G199S, and V254I mutants exhibited up-regulation of small heat shock protein (HSP) genes, which encode chaperones that buffer insoluble protein aggregation (46) (SI Appendix, Fig. S9B). In all of the four alg-1 NDD mutants, the unfolded protein response-related genes were also up-regulated (Fig. 8D). Perturbation of small HSP genes was only observed in the F180Δ, G199S, and V254I mutants, but not in the H751L or null mutants (SI Appendix, Fig. S9B), suggesting that proteome stress can be allelic specific and is not an inevitable consequence of disrupting miRISC function.

Discussion

Modeling Human AGO De Novo Coding Variants in C. elegans Reveals Allele-Specific AGO Functions.

Structural studies of mammalian AGOs and analyses of the evolutionary conservation of AGO amino acid sequences provide insights into the functional architecture of AGOs at the level of individual amino acid residues (4, 26, 47). Key functional residues have also been revealed by forward genetic screens, exemplified by G553 and S895, for which mutations at the corresponding amino acids in C. elegans ALG-1 can impair miRNA biogenesis and guide-passenger strand selection (10, 28). The de novo mutations in AGO1 and AGO2 carried by AGO syndrome patients point to the significance of the corresponding amino acids in AGO function (18, 19). It is noteworthy that most of the amino acids mutated in AGO syndrome patients, although phylogenetically conserved, had not been explicitly linked to AGO functions by previous studies. Thus, genetic modeling in an experimental animal of specific AGO mutations identified in human patients offers an efficient strategy for exploring evolutionarily conserved AGO functions.

We chose four AGO1 mutations to model based on either of two criteria: 1) occurrence in multiple independent families (F180Δ, G199S, V254I) or 2) adjacency to a previously identified phenocritical residue (H751L). We show that the alg-1 NDD mutant proteins accumulate in C. elegans, bind to miRNAs, and disrupt miRNA activity. For at least two of the alg-1 NDD mutants, developmental and molecular phenotypes are stronger than the alg-1(null), consistent with the antimorphic mutation model applied to a previously described class of C. elegans alg-1 mutations (10).

Notably, the relative severity of the developmental phenotypes of C. elegans alg-1 NDD mutants is consistent with relative severity of symptoms in the AGO syndrome patients. In C. elegans, F180Δ and H751L strongly impaired the viability, vulval integrity, and larval-to-adult differentiation of hypodermal cells, while G199S conferred more moderate phenotypes and V254I exhibited nearly undetectable phenotypes. Similarly, the H751L patients (monozygotic twins, n = 1) exhibit severe ID with growth delay, microcephaly, speech impairment, motor delay, feeding difficulty, facial dysmorphia, and F180Δ patients (n = 9) exhibit mild-to-severe ID and motor delay, and some patients developed epilepsy, facial dysmorphia, growth retardation (18). In contrast, the G199S patients (n = 9) exhibit mild-to-moderate ID with speech impairment, epilepsy, motor delay, and facial dysmorphia for some patients. V254I patients (n = 2) exhibit the least severe symptoms with mild ID, speech delay, epilepsy, and hyperactivity but no motor delay or additional features (no growth retardation or MRI anomalies) (18). It is interesting to note that, in the latest version of the gnomAD, which has recently been updated to include exome and genome sequencing data for several hundreds of thousands of individuals (v4.0.0), the V254I variation is reported in 5 individuals, whereas the other three NDD variants tested are not found. This observation, combined with our results from C. elegans, argues in favor of a moderate effect of the V254I variation, and could even question its involvement in NDD, even though it was initially found de novo in two individual patients. Together, this broad correspondence of phenotypic severity suggests that each mutation may impair the AGO protein in a similar fashion in each system, underscoring the potential utility of C. elegans to study this class of human genetic disorders.

The four alg-1 NDD mutations displayed distinctive impairments of AGO functions in C. elegans, in terms of the quality and quantity of their effects on miRNA biogenesis and gene expression. The severity of perturbations in miRNA levels and translatomes varied between different mutants, as did the specific profiles of disturbed miRNAs and disrupted gene expression. The mutations also displayed allele-specificity in their relative impacts on target mRNA abundance versus TE. These distinctions in developmental and molecular phenotypes between different alg-1 NDD mutations in C. elegans suggest that the mutated amino acids have differing mechanistic impacts on the in vivo functions of ALG-1 protein.

Current understanding of human AGO2 crystal structure (27), applied to our findings, suggests possible mechanisms for how the NDD mutations modeled here could impair AGO protein functions. H751 resides in the PIWI-MID channel where the miRNA seed region duplexes with the target RNA. The H751 side chain imidazole group is predicted to contact the backbone phosphates of the miRNA g5 and g6 nucleotides. In H751L mutant ALG-1, the leucine substitution would dramatically impair this interaction. Interestingly, we found that mutations at the two residues preceding H751 (S750F, and C749Y) can also strongly impair ALG-1 function, as revealed by the strong developmental phenotypes of the mutants. Since each of the S750F and C749Y mutations alters the hydrophobicity and size of the side chains, these mutations may change the positioning of H751 and consequently prohibit it from interacting properly with the miRNA. It is also possible that the altered side chain size and hydrophobicity in these mutations may disrupt more distant domains of ALG-1 through allosteric distortions of its structure.

A recent study of Arabidopsis thaliana AGO AtAGO10 identified a ß-hairpin in the L1 domain that contacts the t9-t13 of target RNA by electrostatic forces and helps coordinate 3′ non-seed pairing to the target (48). This conserved L1 ß-hairpin includes the residue homologous to AGO1 F180 and is sterically adjacent to the residue homologous to AGO1 G199 (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). In the structure of the human AGO2::miRNA::target complex, the ß-hairpin is adjacent to t11-t13 of the target RNA (SI Appendix, Fig. S10B) (20). Genetic and biochemical studies have shown that such 3′ pairing, especially at t11-t13, can be critical to the proper regulation of certain miRNA/targets (33, 49). Thus, although F180 and G199 residues do not directly contact the 3′ duplex, these mutations may alter structure or movement of the ß-hairpin and, perhaps impairing miRNA/target interactions that requires 3′ duplex formation. Extrapolating from the structure of AtAGO10 in the slicing configuration, where the L1 ß-hairpin interacts with the non-guide strand of the helical miRNA::target duplex, it is possible that the F180Δ and G199S mutations could disrupt interactions of the L1 ß-hairpin with the passenger strand of AGO::pre-miRNA complexes. This would be consistent with our results that the F180Δ and G199S mutations disrupt miRNA biogenesis, as well as with the finding that human AGO2 F181A mutation (corresponding to F179 in AGO1) causes a duplex unwinding defect (50). V254 is not positioned in sub-regions with structurally or biochemically characterized functions and is not predicted to directly interact with the miRNA::target duplex, but rather is exposed on the surface of the AGO protein (31). Thus, the V254I mutation may impair AGO protein function by impacting interactions with other proteins.

Molecular Mechanisms of the Antimorphic Effect of alg-1 NDD Mutations.

According to the gnomAD database, human AGO1 and AGO2 exhibit a pLI score (probability of heterozygous loss of function intolerance score) equal to 1 (gnomAD v4.0.0), suggesting that these AGO genes are haplo-insufficient in humans (51). For AGO2, haplo-insufficiency could reflect its critical role in miR-451 biogenesis, which is essential for erythropoiesis and erythroid homeostasis in mammals (21, 52). However, the AGO syndrome AGO1 and AGO2 mutations are overwhelmingly single amino acid changes (18, 19, 53), and not frameshift, truncation, or large deletions that would be expected for heterozygous loss-of-function. Thus, AGO syndrome phenotypes may require a greater disruption of AGO function than that which results from simple loss-of-function mutations. This is supported by the identification of patients with developmental delay and other neuronal-muscular disorder syndromes who are heterozygous for large de novo deletions in the 1p34.3 locus, which includes AGO1, AGO3, and AGO4 (16, 17).

How can the AGO syndrome mutations, which are single amino acid changes, cause disruptions of AGO function greater than a null allele? We suggest that the alg-1 NDD mutations, and their counterparts in human AGO1 or AGO2, are antimorphic, broadly impairing miRNA activity by competing with otherwise redundant AGO proteins. In this model, the mutant AGO protein is expressed and can associate with miRNAs but is functionally defective in target repression. Consequently, a large fraction of miRNAs in the cell is sequestered in non-functional complexes, depleting the supply of miRNAs available to paralogous AGO proteins (Fig. 6A).

The sequestration model is particularly well supported by our findings for H751L, which caused strong developmental phenotypes in C. elegans, but only mildly disturbed the profiles of total miRNA or the profiles of miRNA co-immunoprecipitated with mutant ALG-1. This suggests that H751L mutant ALG-1 supports essentially normal miRNA biogenesis and miRISC assembly, but is defective in target recognition and repression. Considering the possibility that the H751L mutation could impair the interaction of ALG-1 with the backbone of the miRNA seed region (Fig. 2A), it is possible that the H751L mutant ALG-1 sequesters miRNAs in miRISC defective in target binding.

Certain alg-1 antimorphic mutants also disrupt guide/passenger strand selection (Fig. 4) (28), which could in principle cause neomorphic miRNA phenotypes in cases where the normally degraded passenger strand accumulates to functional levels. If the mutant ALG-1 miRISC were to retain partial function, as is the case for the G199S and V254I mutants, then mutant ALG-1 miRISC containing hyper-abundant passenger strands could cause neomorphic target repression and hence contribute to the production of phenotypes distinct from the null mutant.

The Pleiotropy of AGO Functions and the Pathology of AGO NDD Mutations.

In this study, we show that alg-1 NDD mutations can perturb miRNA profiles (Figs. 3 and 4) and the translatomic profiles of hundreds of mRNAs (Fig. 5), including genes predicted to be targeted by down- or up-regulated miRNAs (Dataset S7 and SI Appendix, Fig. S11). Although the severity of translatome perturbations varied among different mutations, the stronger mutations could disrupt as much as 8.6% of total protein-coding genes. These pervasive molecular and developmental phenotypes are consistent with broad disruptions of miRNA activity, and the extensive pleiotropy of AGO-mediated miRNA regulation.

The perturbations of gene expression caused by each alg-1 NDD mutation were remarkably distinct, with each mutant exhibiting sets of disrupted genes that were unaffected in the other mutants. Extending these observations to hypothetical effects of the corresponding mutations in AGO1, we suggest that similar extensive and partially allele-specific gene expression disruptions could occur in the AGO syndrome patients with these AGO1 or AGO2 NDD mutations. Could AGO syndromes pathology result from the dysregulation of a small set of specific genes whose over-expression is causative for NDD and that happen to be dysregulated in common by all the mutations? This scenario is possible and warrants further investigation in mammalian systems. However, the distinctions among the C. elegans alg-1 NDD mutations, in terms of the repertoires of disrupted miRNAs and the profiles of downstream gene perturbations, suggest that NDD pathology in human AGO syndrome patients could reflect, at least in part, the emergent physiological and developmental consequences of broad dysregulation of gene expression networks.

We suggest that AGO NDD mutations can be thought of as triggering cascades of gene expression dysregulation (Fig. 8E). alg-1 NDD mutations disrupt the processing, loading, and/or function of multiple C. elegans miRNAs. Since individual miRNAs can have dozens to hundreds of targets, it is expected that the immediate impact of alg-1 NDD mutations would include de-repression (and/or neomorphic repression in the case of altered miRNA strand selection) of a large set of direct targets. Perturbations of direct miRNA targets, particularly regulatory gene products such as RNA binding proteins and transcription factors, should in turn lead to amplified downstream disruptions of gene regulatory networks, including genes expressed in the nervous system and/or those with human homologs genetically linked to NDD-related phenomena (Fig. 8).

The potential physiological impacts of global dysregulation of gene expression in AGO NDD mutants could include cellular and organismal stress from proteome imbalance. We observed a statistically enriched up-regulation of the expression of stress-related genes in certain C. elegans alg-1 NDD mutants. This up-regulation includes small HSPs, which can be indicative of a proteome imbalance-induced protein aggregation (54–56). Thus, a physiological trigger underlying the pathological effects of AGO NDD mutations could originate from cellular and organismal responses to the disturbance of proteostasis caused by global perturbations of gene expression (Fig. 8E).

Materials and Methods

C. elegans Culture, Genetics, and Phenotype Scoring.

C. elegans were cultured on nematode growth medium, fed with E. coli HB101. alg-1 mutations were obtained by CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing (SI Appendix, Supplemental Methods). Adult viability, progeny number, and col-19::gfp expression were assayed and analyzed as described in SI Appendix, Supplemental Methods.

ALG-1 IP.

Fourth-stage (L4) larvae lysates were obtained and processed as described (57); ALG-1 IP and Western blotting were performed as previously described (58).

sRNA-seq and miRNA Target Site Prediction.

RNA was prepared from synchronized larvae populations (SI Appendix, Supplemental Methods). Library preparation, sequencing, and data analysis were conducted as described in SI Appendix, Supplemental Methods. miRNA targets were predicted using TargetScanWorm v6.1 (59) as described in SI Appendix, Supplemental Methods.

Ribosome Profiling.

Ribosome protected footprint (RPF) cloning and data analysis were performed as described (33) with modifications (SI Appendix, Supplemental Methods). RNA-seq in conjunction with ribosome profiling, data analysis, and calculation of TE, were conducted as previously described (36) with modifications, SI Appendix, Supplemental Methods.

Calculation of NRF.score.

The NRF.score, which corresponds to the relative functionality of a given miRNA in a particular alg-1 mutant, was calculated as described in SI Appendix, Supplemental Methods.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Dataset S01 (XLSX)

Dataset S02 (XLSX)

Dataset S03 (CSV)

Dataset S04 (XLSX)

Dataset S05 (XLSX)

Dataset S06 (CSV)

Dataset S07 (XLSX)

Dataset S08 (XLSX)

Acknowledgments

We thank members of Ambros, Mello, and Zinovyeva labs for project discussions. We thank Brittany Morgan, Francesca Massi, and Ian MacRae for commenting on the structural modeling. This research was supported by funding from NIH grants R01GM088365, R01GM034028, R35GM131741 (V.R.A.), and R35GM124828 (A.Z.). Some C. elegans strains were provided by Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by the NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40OD010440).

Author contributions

Y.D., L.L., A.P., A.Z., and V.A. designed research; Y.D., L.L., G.P.P., and A.Z. performed research; Y.D., L.L., G.P.P., and A.Z. analyzed data; and Y.D., A.Z., and V.A. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Contributor Information

Anna Zinovyeva, Email: zinovyeva@ksu.edu.

Victor Ambros, Email: victor.ambros@umassmed.edu.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

The data discussed in this publication have been deposited in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE252066 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE252066) (60).

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Bartel D. P., Metazoan microRNAs. Cell 173, 20–51 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee R. C., Feinbaum R. L., Ambros V., The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell 75, 843–854 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iwakawa H. O., Tomari Y., The functions of MicroRNAs: mRNA decay and translational repression. Trends Cell Biol. 25, 651–665 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meister G., Argonaute proteins: Functional insights and emerging roles. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14, 447–459 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grishok A., et al. , Genes and mechanisms related to RNA interference regulate expression of the small temporal RNAs that control C. elegans developmental timing. Cell 106, 23–34 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouasker S., Simard M. J., The slicing activity of miRNA-specific Argonautes is essential for the miRNA pathway in C. elegans. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 10452–10462 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eulalio A., Huntzinger E., Izaurralde E., GW182 interaction with Argonaute is essential for miRNA-mediated translational repression and mRNA decay. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 346–353 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dueck A., Ziegler C., Eichner A., Berezikov E., Meister G., microRNAs associated with the different human Argonaute proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 9850–9862 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muller M., Fazi F., Ciaudo C., Argonaute proteins: From structure to function in development and pathological cell fate determination. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 7, 360 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zinovyeva A. Y., Bouasker S., Simard M. J., Hammell C. M., Ambros V., Mutations in conserved residues of the C. elegans microRNA argonaute ALG-1 identify separable functions in ALG-1 miRISC loading and target repression. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004286 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng B., Hu P., Lu S.-J., Chen J.-B., Ge R.-L., Increased argonaute 2 expression in gliomas and its association with tumor progression and poor prognosis. Asian Pacific J. Cancer Prev. 15, 4079–4083 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gou L. T., et al. , Ubiquitination-deficient mutations in human piwi cause male infertility by impairing histone-to-protamine exchange during spermiogenesis. Cell 169, 1090–1104.e13 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang J., et al. , Up-regulation of Ago2 expression in gastric carcinoma. Medical Oncol. 30, 628 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Völler D., et al. , Argonaute family protein expression in normal tissue and cancer entities. PLoS One 11, e0161165 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu J., Yang J., Cho W. C., Zheng Y., Argonaute proteins: Structural features, functions and emerging roles. J. Adv. Res. 24, 317–324 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tokita M. J., et al. , Five children with deletions of 1p34.3 encompassing AGO1 and AGO3. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 23, 761–765 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacher J. E., Innis J. W., Interstitial microdeletion of the 1p34.3p34.2 region. Mol. Genet Genomic Med. 6, 673–677 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schalk A., et al. , De novo coding variants in the AGO1 gene cause a neurodevelopmental disorder with intellectual disability. J. Med. Genet. 59, 965–975 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lessel D., et al. , Germline AGO2 mutations impair RNA interference and human neurological development. Nat. Commun. 11, 5797 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sheu-Gruttadauria J., Xiao Y., Gebert L. F., MacRae I. J., Beyond the seed: Structural basis for supplementary microRNA targeting by human Argonaute2. EMBO J. 38, e101153 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meister G., et al. , Human Argonaute2 mediates RNA cleavage targeted by miRNAs and siRNAs. Mol. Cell 15, 185–197 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sulston J. E., Schierenberg E., White J. G., Thomson J. N., The embryonic cell lineage of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 100, 64–119 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ilbay O., Ambros V., Regulation of nuclear-cytoplasmic partitioning by the lin-28-lin-46 pathway reinforces microRNA repression of HBL-1 to confer robust cell-fate progression in C. elegans. Development 146, dev183111 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reinhart B. J., et al. , The 21-nucleotide let-7 RNA regulates developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 403, 901–906 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abbott A. L., et al. , The let-7 MicroRNA family members mir-48, mir-84, and mir-241 function together to regulate developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Cell 9, 403–414 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schirle N. T., Sheu-Gruttadauria J., MacRae I. J., Structural basis for microRNA targeting. Science 346, 608–613 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schirle N. T., MacRae I. J., The crystal structure of human Argonaute2. Science 336, 1037–1040 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zinovyeva A. Y., Veksler-Lublinsky I., Vashisht A. A., Wohlschlegel J. A., Ambros V. R., Caenorhabditis elegans ALG-1 antimorphic mutations uncover functions for Argonaute in microRNA guide strand selection and passenger strand disposal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, E5271–E5280 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ingolia N. T., Ribosome footprint profiling of translation throughout the genome. Cell 165, 22–33 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moss E. G., Lee R. C., Ambros V., The cold shock domain protein LIN-28 controls developmental timing in C. elegans and is regulated by the lin-4 RNA. Cell 88, 637–646 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Slack F. J., et al. , The lin-41 RBCC gene acts in the C. elegans heterochronic pathway between the let-7 regulatory RNA and the LIN-29 transcription factor. Mol. Cell 5, 659–669 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abrahante J. E., et al. , The Caenorhabditis elegans hunchback-like gene lin-57/hbl-1 controls developmental time and is regulated by microRNAs. Dev. Cell 4, 625–637 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duan Y., Veksler-Lublinsky I., Ambros V., Critical contribution of 3’ non-seed base pairing to the in vivo function of the evolutionarily conserved let-7a microRNA. Cell Rep. 39, 110745 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bazzini A. A., Lee M. T., Giraldez A. J., Ribosome profiling shows that miR-430 reduces translation before causing mRNA decay in zebrafish. Science 336, 233–237 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giraldez A. J., et al. , Zebrafish MiR-430 promotes deadenylation and clearance of maternal mRNAs. Science 312, 75–79 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duan Y., Sun Y., Ambros V., RNA-seq with RNase H-based ribosomal RNA depletion specifically designed for C. elegans. MicroPubl Biol. 2020, 10.17912/micropub.biology.000312 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Consortium TAoGR, Alliance of genome resources portal: Unified model organism research platform. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, D650–D658 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harris T. W., et al. , WormBase: A modern model organism information resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, D762–D767 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duffy E. E., et al. , Developmental dynamics of RNA translation in the human brain. Nat. Neurosci. 25, 1353–1365 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kochinke K., et al. , Systematic phenomics analysis deconvolutes genes mutated in intellectual disability into biologically coherent modules. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 98, 149–164 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Higgins D. P., Weisman C. M., Lui D. S., D’Agostino F. A., Walker A. K., Defining characteristics and conservation of poorly annotated genes in Caenorhabditis elegans using WormCat 2.0. Genetics 221, iyac085 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balch W. E., Morimoto R. I., Dillin A., Kelly J. W., Adapting proteostasis for disease intervention. Science 319, 916–919 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hartl F. U., Bracher A., Hayer-Hartl M., Molecular chaperones in protein folding and proteostasis. Nature 475, 324–332 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taylor R. C., Berendzen K. M., Dillin A., Systemic stress signalling: Understanding the cell non-autonomous control of proteostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 15, 211–217 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hetz C., Chevet E., Oakes S. A., Proteostasis control by the unfolded protein response. Nat. Cell Biol. 17, 829–838 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haslbeck M., Franzmann T., D. Weinfurtner, J. Buchner, Some like it hot: The structure and function of small heat-shock proteins. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 842–846 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hutvagner G., Simard M. J., Argonaute proteins: Key players in RNA silencing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 22–32 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xiao Y., Maeda S., Otomo T., MacRae I. J., Structural basis for RNA slicing by a plant Argonaute. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 30, 778–784 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McGeary S. E., Bisaria N., Pham T. M., Wang P. Y., Bartel D. P., MicroRNA 3’-compensatory pairing occurs through two binding modes, with affinity shaped by nucleotide identity and position. eLife 11, e69803 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kwak P. B., Tomari Y., The N domain of Argonaute drives duplex unwinding during RISC assembly. Nat. struct. Mol. Biol. 19, 145–151 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Karczewski K. J., et al. , The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature 581, 434–443 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dore L. C., et al. , A GATA-1-regulated microRNA locus essential for erythropoiesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 3333–3338 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takagi M., et al. , Complex congenital cardiovascular anomaly in a patient with AGO1-associated disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 191, 882–892 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Walther D. M., et al. , Widespread proteome remodeling and aggregation in aging C. elegans. Cell 161, 919–932 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Höhn A., Tramutola A., Cascella R., Proteostasis failure in neurodegenerative diseases: Focus on oxidative stress. Oxidative Med. Cellular longev. 2020, 5497046 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hu C., et al. , Heat shock proteins: Biological functions, pathological roles, and therapeutic opportunities. MedComm (2020) 3, e161 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li L., Zinovyeva A. Y., Protein extract preparation and co-immunoprecipitation from Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Vis. Exp. e61243 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zou Y., et al. , Developmental decline in neuronal regeneration by the progressive change of two intrinsic timers. Science 340, 372–376 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Agarwal V., Bell G. W., Nam J. W., Bartel D. P., Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs. eLife 4, e05005 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Duan Y., et al. , Modeling neurodevelopmental disorder-associated human AGO1 mutations in C. elegans Argonaute alg-1. GEO. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE252066. Deposited 26 December 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Dataset S01 (XLSX)

Dataset S02 (XLSX)

Dataset S03 (CSV)

Dataset S04 (XLSX)

Dataset S05 (XLSX)

Dataset S06 (CSV)

Dataset S07 (XLSX)

Dataset S08 (XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

The data discussed in this publication have been deposited in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE252066 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE252066) (60).