Key Points

Question

What is the prevalence of self-reported Δ8-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and marijuana use among 12th-grade students in the US and its distribution across sociodemographic factors and state cannabis policies?

Findings

In this nationally representative 2023 survey, 11.4% of 2186 US 12th-grade students self-reported Δ8-THC use and 30.4% self-reported marijuana use in the past year. Δ8-THC use prevalence was higher in the South and Midwest US and in states without legal adult-use marijuana or Δ8-THC regulations. Marijuana use prevalence did not differ by cannabis policies.

Meaning

Δ8-THC use prevalence is appreciable among US adolescents and is a potential public health concern.

Abstract

Importance

Gummies, flavored vaping devices, and other cannabis products containing psychoactive hemp-derived Δ8-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) are increasingly marketed in the US with claims of being federally legal and comparable to marijuana. National data on prevalence and correlates of Δ8-THC use and comparisons to marijuana use among adolescents in the US are lacking.

Objective

To estimate the self-reported prevalence of and sociodemographic and policy factors associated with Δ8-THC and marijuana use among US adolescents in the past 12 months.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This nationally representative cross-sectional analysis included a randomly selected subset of 12th-grade students in 27 US states who participated in the Monitoring the Future Study in-school survey during February to June 2023.

Exposures

Self-reported sex, race, ethnicity, and parental education; census region; state-level adult-use (ie, recreational) marijuana legalization (yes vs no); and state-level Δ8-THC policies (regulated vs not regulated).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was self-reported Δ8-THC and marijuana use in the past 12 months (any vs no use and number of occasions used).

Results

In the sample of 2186 12th-grade students (mean age, 17.7 years; 1054 [48.9% weighted] were female; 232 [11.1%] were Black, 411 [23.5%] were Hispanic, 1113 [46.1%] were White, and 328 [14.2%] were multiracial), prevalence of self-reported use in the past 12 months was 11.4% (95% CI, 8.6%-14.2%) for Δ8-THC and 30.4% (95% CI, 26.5%-34.4%) for marijuana. Of those 295 participants reporting Δ8-THC use, 35.4% used it at least 10 times in the past 12 months. Prevalence of Δ8-THC use was lower in Western vs Southern census regions (5.0% vs 14.3%; risk difference [RD], −9.4% [95% CI, −15.2% to −3.5%]; adjusted risk ratio [aRR], 0.35 [95% CI, 0.16-0.77]), states in which Δ8-THC was regulated vs not regulated (5.7% vs 14.4%; RD, −8.6% [95% CI, −12.9% to −4.4%]; aRR, 0.42 [95% CI, 0.23-0.74]), and states with vs without legal adult-use marijuana (8.0% vs 14.0%; RD, −6.0% [95% CI, −10.8% to −1.2%]; aRR, 0.56 [95% CI, 0.35-0.91]). Use in the past 12 months was lower among Hispanic than White participants for Δ8-THC (7.3% vs 14.4%; RD, −7.2% [95% CI, −12.2% to −2.1%]; aRR, 0.54 [95% CI, 0.34-0.87]) and marijuana (24.5% vs 33.0%; RD, −8.5% [95% CI, −14.9% to −2.1%]; aRR, 0.74 [95% CI, 0.59-0.94]). Δ8-THC and marijuana use prevalence did not differ by sex or parental education.

Conclusions and Relevance

Δ8-THC use prevalence is appreciable among US adolescents and is higher in states without marijuana legalization or existing Δ8-THC regulations. Prioritizing surveillance, policy, and public health efforts addressing adolescent Δ8-THC use may be warranted.

This cross-sectional nationally representative classroom-based survey of US 12th-grade students examines the self-reported prevalence of and sociodemographic and policy factors associated with Δ8-THC and marijuana use during a 12-month period.

Introduction

Δ8-Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is an isomer of Δ9-THC, the principal psychoactive compound of marijuana (cannabis). Δ8-THC and Δ9-THC both act on cannabinoid-1 receptors and produce similar intoxicating effects,1,2,3 but have different legal contexts. Δ9-THC is naturally abundant in marijuana—cannabis plant subtypes federally regulated as controlled substances. Δ8-THC is synthesized from hemp—cannabis plant subtypes with low Δ9-THC concentrations historically cultivated for industrial purposes, which were federally legalized by the 2018 Agriculture Improvement Act.4 Since 2018, commercially manufactured consumable hemp-derived Δ8-THC products have proliferated.5 Gummies and other edibles, electronic vaping devices, and combustible flower containing Δ8-THC are marketed as providing a user experience comparable to marijuana in a product that is federally legal (examples are shown in eFigure 1 in Supplement 1).5,6,7 Δ8-THC exposure may pose risks to adolescents, including addiction, neurodevelopmental changes, acute psychiatric reactions from accidental overdosing, and exposure to toxic byproducts generated during Δ8-THC synthesis.5,6,8,9,10,11

Adolescent Δ8-THC use prevalence estimates are lacking, leaving little evidence to guide policies. Currently, there is no federal minimum purchasing age for Δ8-THC products,12 which are sold online (often without age verification)13,14 and in retailers frequented by youth (eg, convenience stores).15 Adolescents’ access to Δ8-THC could be higher in states without Δ8-THC regulations or states without legal adult-use marijuana where Δ8-THC might be marketed as a legal cannabis substitute.16 This study estimated self-reported Δ8-THC use prevalence among US adolescents overall and stratified by sociodemographic factors and state-level cannabis policies. Marijuana use was studied for comparison.

Methods

Data Source and Participants

The Monitoring the Future (MTF) study is a cross-sectional nationally representative classroom-based survey of US youth.17 The 2023 MTF survey (administered February 14, 2023, to June 2, 2023) included a question about Δ8-THC use to one-third of 12th-grade students selected at random. Survey responses were confidential. The MTF study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (#HUM00217920). Informed consent was obtained from parents of students younger than 18 years (passive or written active, per school policy) and from students 18 years or older (oral).

Measures

Participants self-reported the number of Δ8-THC and marijuana use occasions in the past 12 months (0, 1-2, 3-5, 6-9, 10-19, 20-39, and ≥40 occasions). Outcomes were any use (≥1 vs 0 occasions) and the number of occasions used.

Participants self-reported sex, race and ethnicity (self-identified based on fixed categories assessed to describe the study sample), and parental education; state census region was derived from school location. State-level Δ8-THC policies were coded as having regulations (ie, bans or restrictions on Δ8-THC products) vs no Δ8-THC legislation. State-level policies for nonmedical adult-use (ie, recreational) marijuana were coded as legal vs not legal. Policies were classified as of January 1, 2023 (eTables 1-2 in Supplement 1).

Analysis

Past–12-month Δ8-THC and marijuana use prevalence were calculated overall and stratified by sociodemographic and policy variables. Log-binomial models were used to estimate adjusted risk ratios (aRRs) for associations of sociodemographic and policy variables with Δ8-THC and marijuana use controlling for sex, race and ethnicity, and parental education.

In sensitivity analyses, prevalence estimates were recalculated and stratified by state-level cannabis policy variables classified as of January 1, 2022, (ie, earliest point in the 12-month recall interval) and a trichotomous Δ8-THC policy variable distinguishing full ban vs some restrictions vs no legislation.

Analyses in STATA (StataCorp LLC) were weighted to produce nationally representative estimates, accounting for complex survey designs and using multiple imputation with chained equations for missing correlate data (<1% missing).18 Statistical significance was 2-tailed α = .05. Differences in aRRs for Δ8-THC vs marijuana use were assessed based on nonoverlapping CIs. This exploratory study did not correct for multiple testing. Additional methodological details are provided in the eMethods in Supplement 1.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

The sample included 2186 students (eFigure 2 in Supplement 1); 1054 (48.9%) were females, 1033 (45.8%) were males, and 99 (5.3%) reported another sex or preferred not to report sex; 69 (4.0%) were Asian, 232 (11.1%) were Black, 411 (23.5%) were Hispanic, 1113 (46.1%) were White, 328 (14.2%) were multiracial, and 33 (1.1%) identified as another race. Overall, 51.7% of the sample population had a parent with a college degree. Of the sample, 36.7% lived in South, 24.5% in West, 22.0% in Midwest, and 16.9% in Northeast US census regions; 44.2% lived in states with adult-use marijuana legalization; and 34.8% lived in states with Δ8-THC regulations (Table). The mean age of participants was 17.7 (95% CI, 17.5-17.8) years (range, 14-22).

Table. Sample Characteristics and Prevalence and Correlates of Δ8-THC and Marijuana Use in US 12th-Grade Students in 2023 (N = 2186)a.

| Characteristic | Participants, No. | Participants (95% CI), % | Past 12-mo Δ8-THC use | Past 12-mo marijuana use | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (95% CI), % | Risk difference (95% CI)b | Prevalence (95% CI), % | Risk difference (95% CI)b | |||

| Overall | 2186 | 11.4 (8.6 to 14.2) | 30.4 (26.5 to 34.4) | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 1054 | 48.9 (45.5 to 52.3) | 9.6 (6.8 to 12.4) | Reference | 29.6 (24.2 to 35.0) | Reference |

| Male | 1033 | 45.8 (42.6 to 48.9) | 12.3 (8.8 to 15.7) | 2.7 (−0.4 to 5.7) | 30.3 (26.5 to 34.1) | 0.6 (−4.1 to 5.4) |

| Other or unreported | 99 | 5.3 (3.8 to 6.8) | 19.7 (4.0 to 35.3) | 10.1 (−5.7 to 25.8) | 38.8 (29.8 to 47.9) | 9.2 (−1.1 to 19.5) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||||

| Asian | 69 | 4.0 (0.9 to 7.1) | 9.6 (2.2 to 17.1) | −4.8 (−11.8 to 2.2) | 20.9 (6.9 to 34.8) | −12.1 (−25.2 to 1.0) |

| Black | 232 | 11.1 (5.4 to 16.7) | 9.7 (2.6 to 16.7) | −4.8 (−11.7 to 2.1) | 31.8 (24.8 to 38.8) | −1.3 (−9.6 to 7.1) |

| Hispanic | 411 | 23.5 (10.2 to 36.8) | 7.3 (4.5 to 10.1) | −7.2 (−12.2 to −2.1) | 24.5 (19.6 to 29.5) | −8.5 (−14.9 to −2.1) |

| White | 1113 | 46.1 (34.3 to 57.8) | 14.4 (10.3 to 18.6) | Reference | 33.0 (28.4 to 37.6) | Reference |

| Multiracial | 328 | 14.2 (11.9 to 16.5) | 10.3 (6.2 to 14.4) | −4.1 (−9.6 to 1.3) | 34.4 (25.6 to 43.2) | 1.4 (−8.1 to 10.9) |

| Another race or ethnicityc | 33 | 1.1 (0.3 to 1.8) | 7.2 (−1.6 to 16.0) | −7.3 (−16.4 to 1.9) | 16.6 (1.8 to 31.3) | −16.4 (−32.2 to −0.7) |

| Parental education | ||||||

| College degree | 1277 | 51.7 (40.9 to 62.6) | 12.6 (8.8 to 16.3) | Reference | 31.1 (26.7 to 35.5) | Reference |

| No college degree | 909 | 48.3 (37.4 to 59.1) | 10.1 (6.6 to 13.5) | −2.5 (−7.2 to 2.2) | 29.7 (24.3 to 35.1) | −1.4 (−7.4 to 4.6) |

| US Census region | ||||||

| Midwest | 616 | 22.0 (12.3 to 31.6) | 14.6 (10.9 to 18.2)d | 0.2 (−6.0 to 6.4) | 31.5 (23.9 to 39.0) | 4.5 (−4.6 to 13.5) |

| Northeast | 530 | 16.9 (7.8 to 26.0) | 10.1 (5.3 to 14.9) | −4.2 (−11.2 to 2.7) | 35.2 (27.7 to 42.7) | 8.2 (−0.8 to 17.2) |

| South | 813 | 36.7 (23.7 to 49.6) | 14.3 (9.3 to 19.3) | Reference | 27.0 (22.0 to 32.0) | Reference |

| West | 227 | 24.5 (8.5 to 40.5) | 5.0 (2.0 to 7.9)d | −9.4 (−15.2 to −3.5) | 31.3 (20.1 to 42.6) | 4.3 (−8.0 to 16.6) |

| Adult-use marijuana legalization | ||||||

| Not legale | 1385 | 55.8 (40.7 to 70.8) | 14.0 (10.2 to 17.8) | Reference | 29.2 (25.0 to 33.3) | Reference |

| Legalf | 801 | 44.2 (29.2 to 59.3) | 8.0 (5.0 to 11.0) | −6.0 (−10.8 to −1.2) | 32.0 (24.7 to 39.3) | 2.8 (−5.6 to 11.2) |

| Δ8-THC regulation | ||||||

| Regulatedg | 536 | 34.8 (19.0 to 50.5) | 5.7 (3.1 to 8.4) | −8.6 (−12.9 to −4.4) | 30.6 (22.4 to 38.9) | 0.3 (−8.9 to 9.6) |

| No legislationh | 1650 | 65.2 (49.5 to 81.0) | 14.4 (11.1 to 17.6) | Reference | 30.3 (26.1 to 34.5) | Reference |

Abbreviations: RD, risk difference; THC, tetrahydrocannabinol.

Percentages are weighted to produce nationally representative estimates.

Reference group was the category with largest number of participants.

Includes American Indian and Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and Middle Eastern.

Estimates significantly different between 2 nonreference categories based on nonoverlapping 95% CIs.

Included states without adult-use marijuana legalization prior to January 1, 2023: Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Minnesota, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, West Virginia, Wisconsin.

Included states with adult-use marijuana legalization prior to January 1, 2023: Arizona, California, Illinois, Maine, Michigan, Missouri, Montana, New York, Oregon, Vermont, Washington.

Included states with Δ8-THC regulations (either banned or restricted) prior to January 1, 2023: California, Louisiana, Michigan, Montana, New York, Oregon, Vermont, Washington.

Included states with no Δ8-THC legislation prior to January 1, 2023: Alabama, Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Maine, Minnesota, Missouri, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, West Virginia, Wisconsin.

Self-Reported Δ8-THC Use

Prevalence of Δ8-THC use over the past 12 months was 11.4% (95% CI, 8.6%-14.2%) (Table). Among adolescents with Δ8-THC use in the past 12 months (n = 295), 68.1% used Δ8-THC at least 3 times, 35.4% used it at least 10 times, and 16.8% used it at least 40 times in the past 12 months (eTable 3 in Supplement); 90.7% of those adolescents also reported marijuana use in the past 12 months.

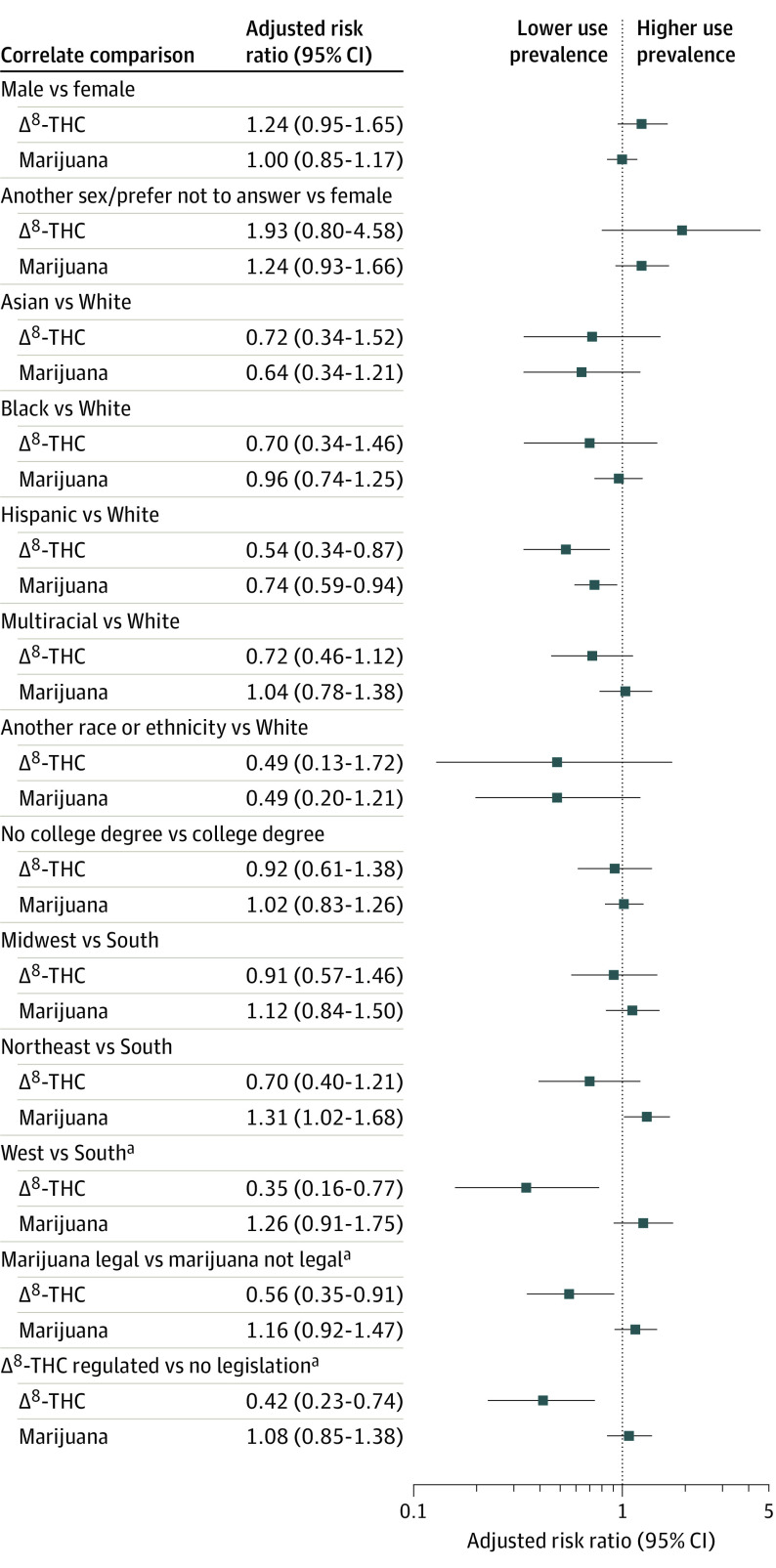

Δ8-THC use prevalence was 9.6% among females, 12.3% among males, and 19.7% among those with another or unreported sex, with no significant differences between sex. Prevalence was significantly lower among Hispanic participants than White participants (7.3% vs 14.4%; risk difference [RD], −7.2% [95% CI, −12.2% to −2.1%]; aRR, 0.54 [95% CI, 0.34-0.87]) and was 9.6% in Asian participants, 9.7% in Black participants, 10.3% in multiracial participants, and 7.2% in other race or ethnicity groups. Δ8-THC use did not significantly differ by parental education (Table and Figure).

Figure. Adjusted Risk Ratios for Associations of Sociodemographic and Policy Factors With Δ8-THC and Marijuana Use.

Subgroup analysis from multivariable models for adjusted estimates of association of sociodemographic and policy variables with past 12-month Δ8-THC use and marijuana use. Models include the regressor of interest as well as sex, race and ethnicity, and parental education. The reference category was the category with the largest number of participants.

aRisk ratios for respective regressor are significantly different between Δ8-THC and marijuana use outcomes based on nonoverlapping 95% CIs.

Past 12-month Δ8-THC use varied by US census region (14.6% in the Midwest, 14.3% in the South, 10.1% in the Northeast, and 5.0% in the West), with significantly lower prevalence in the West than the South (RD, −9.4% [95% CI, −15.2% to −3.5%]; aRR, 0.35 [95% CI, 0.16-0.77]). Past 12-month Δ8-THC use was also significantly higher in the Midwest than the West based on nonoverlapping 95% CIs of 2 prevalence estimates. Δ8-THC use prevalence was lower in states with adult-use marijuana legalization vs those without (8.0% vs 14.0%; RD,−6.0% [95% CI, −10.8% vs −1.2%]; aRR, 0.56 [95% CI, 0.35-0.91]) and in states with Δ8-THC regulation vs no legislation (5.7% vs 14.4%; RD, −8.6% [95% CI, −12.9% to −4.4%]; aRR, 0.42 [95% CI, 0.23-0.74]).

Self-Reported Marijuana Use

Prevalence of marijuana use over the past 12 months was 30.4% (95% CI, 26.5%-34.4%) overall, was significantly lower for Hispanic (24.5%) vs White (33.0%) participants (RD,−8.5% [95% CI, −14.9% to −2.1%]; aRR, 0.74 [95% CI, 0.59-0.94]), and did not significantly differ by sex or parental education (Table and Figure). Marijuana use prevalence was significantly higher in the Northeast vs South in adjusted models only (RD, 8.2% [95% CI, −0.8% to 17.2%]; aRR, 1.31 [95% CI, 1.02-1.68]). There were no differences in marijuana use by state-level cannabis policies.

Differences in Factors Associated With Self-Reported Δ8-THC and Marijuana Use

Census region and cannabis policy aRRs were significantly different for Δ8-THC and marijuana use, with nonoverlapping 95% CIs (Figure).

Sensitivity Analyses

Results applying an earlier policy cutoff date aligned with the primary results (eTable 4 in Supplement 1). Δ8-THC use prevalence was lower where Δ8-THC was banned (5.3%) or restricted (6.1%) vs places in which there were no regulations (14.4%) (eTable 5 in Supplement 1).

Discussion

In 2023, an appreciable percentage of surveyed 12th-grade students in the US reported using Δ8-THC in the past year. Δ8-THC use was disproportionately concentrated in the South and Midwest US and in states without adult-use marijuana legalization or Δ8-THC regulations. Marijuana use did not differ by cannabis policies, aligning with some previous research.19

Given the federal policy context and divergent regional and policy correlates of Δ8-THC and marijuana use found in this study, Δ8-THC may be marketed to and/or used by adolescents as a psychoactive cannabis substitute in places in which adult-use marijuana is illegal.16 This study provides preliminary evidence that state-level Δ8-THC regulations may be associated with lower adolescent use. Further research using data from multiple years and methodologies appropriate for policy evaluation19 could bolster inferences.

Limitations

This study has limitations. First, census region and state-level policy variables were correlated, precluding testing associations net of each other. Second, the survey sample did not include all states. Third, those who were absent or not enrolled in school were not sampled. Fourth, the mean age of participants was 17.7 years, so results may not represent younger adolescents. Fifth, use of other hemp-derived products (eg, Δ10-THC, hexahydrocannabinol, or THC-O)20 was not measured. This study might underestimate the scope of adolescent use of Δ8-THC or other psychoactive hemp-derived products.

Conclusions

Δ8-THC use prevalence is appreciable among US adolescents and is higher in states without marijuana legalization or existing Δ8-THC regulations. Prioritizing surveillance, policy, and public health efforts addressing adolescent Δ8-THC use may be warranted.

eResults

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Durbin DJ, King JM, Stairs DJ. Behavioral effects of vaporized delta-8 tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol, and mixtures in male rats. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. Published online February 21, 2023. doi: 10.1089/can.2022.0257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spindle T. Comparative effects of Delta-8-THC and Delta-9-THC: results from a human laboratory study. Abstract presented at the American Psychological Association Annual Convention; August 3, 2023; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tagen M, Klumpers LE. Review of delta-8-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ8 -THC): comparative pharmacology with Δ9 -THC. Br J Pharmacol. 2022;179(15):3915-3933. doi: 10.1111/bph.15865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farm Bill . US Dept of Agriculture. Accessed September 15, 2022. https://www.usda.gov/farmbill

- 5.Harlow AF, Leventhal AM, Barrington-Trimis JL. Closing the loophole on hemp-derived cannabis products: a public health priority. JAMA. 2022;328(20):2007-2008. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.20620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Food and Drug Administration . 5 things to know about delta-8 tetrahydrocannabinol (delta-8 THC). Updated May 4, 2022. Accessed September 16, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/5-things-know-about-delta-8-tetrahydrocannabinol-delta-8-thc [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Leas EC. The hemp loophole: a need to clarify the legality of delta-8-THC and other hemp-derived tetrahydrocannabinol compounds. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(11):1927-1931. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Unregulated Distribution and Sale of Consumer Products Marketed as Delta-8 THC. US Cannabis Council ; 2021. Accessed February 15, 2024. https://irp.cdn-website.com/6531d7ca/files/uploaded/USCC%20Delta-8%20Kit.pdf

- 9.Volkow ND, Swanson JM, Evins AE, et al. Effects of cannabis use on human behavior, including cognition, motivation, and psychosis: a review. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(3):292-297. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.3278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Volkow ND, Baler RD, Compton WM, Weiss SRB. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(23):2219-2227. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1402309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research. National Academies Press; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rossheim ME, LoParco CR, Walker A, et al. Delta-8 THC retail availability, price, and minimum purchase age. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. Published online November 7, 2022. doi: 10.1089/can.2022.0079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson L, Malone M, Paulson E, et al. Potency and safety analysis of hemp delta-9 products: the hemp vs. cannabis demarcation problem. J Cannabis Res. 2023;5(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s42238-023-00197-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Egan KL, Villani S, Soule EK. Absence of age verification for online purchases of cannabidiol and delta-8: implications for youth access. J Adolesc Health. 2023;73(1):195-197. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2023.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanders-Jackson A, Parikh NM, Schleicher NC, Fortmann SP, Henriksen L. Convenience store visits by US adolescents: rationale for healthier retail environments. Health Place. 2015;34:63-66. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2015.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kruger DJ, Kruger JS. Consumer experiences with delta-8-THC: medical use, pharmaceutical substitution, and comparisons with delta-9-THC. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2023;8(1):166-173. doi: 10.1089/can.2021.0124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bachman JG, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Miech RA. The Monitoring the Future Project After Four Decades: Design and Procedures (Monitoring the Future Occasional Paper No. 82). Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 2015:93. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raghunathan T, Lepkowski J, Hoewyk J, Solenberger P. A multivariate technique for multiply imputing missing values using a sequence of regression models. Surv Methodol. 2000;27(1):85-96. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smart R, Pacula RL. Early evidence of the impact of cannabis legalization on cannabis use, cannabis use disorder, and the use of other substances: findings from state policy evaluations. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2019;45(6):644-663. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2019.1669626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rossheim ME, LoParco CR, Henry D, Trangenstein PJ, Walters ST. Delta-8, Delta-10, HHC, THC-O, THCP, and THCV: what should we call these products? J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2023;84(3):357-360. doi: 10.15288/jsad.23-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eResults

Data sharing statement