Abstract

Mounting evidence is showing that altered signaling through the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily can cause abnormal, long-term epigenetic changes which translate into pathological modifications and susceptibility to disease. These effects seem to be more prominent if the exposure occurs early in life, when transcriptomic profiles are rapidly changing. At this time, the coordination of the complex coordinated processes of cell proliferation and differentiation that characterize mammalian development. Such exposures may also alter the epigenetic information of the germ line, potentially leading to developmental changes and abnormal outcomes in subsequent generations. Thyroid hormone (TH) signaling is mediated by specific nuclear receptors, which have the ability to markedly change chromatin structure and gene transcription, and can also regulate other determinants of epigenetic marks. TH exhibits pleiotropic effects in mammals, and during development, its action is regulated in a highly dynamic manner to suit the rapidly evolving needs of multiple tissues. Their molecular mechanisms of action, timely developmental regulation and broad biological effects place THs in a central position to play a role in the developmental epigenetic programming of adult pathophysiology and, through effects on the germ line, in inter- and trans-generational epigenetic phenomena. These areas of epigenetic research are in their infancy, and studies regarding THs are limited. In the context of their characteristics as epigenetic modifiers and their finely tuned developmental action, here we review some of the observations underscoring the role that altered TH action may play in the developmental programming of adult traits and in the phenotypes of subsequent generations via germ line transmission of altered epigenetic information. Considering the relatively high prevalence of thyroid disease and the ability of some environmental chemicals to disrupt TH action, the epigenetic effects of abnormal levels of TH action may be important contributors to the non-genetic etiology of human disease.

1. Introduction

Thyroid hormone (TH) regulate the expression of a wide range of genes. The signaling pathway is complex and highly regulated due to the presence of cell and tissue-specific TH transporters and multiple TH receptor (TR) isoforms that interact with different corepressors and coactivators. Since TRs are ubiquitously expressed, THs impact the transcription of target genes in many tissues, with subsequent biological effects on the proliferation, differentiation and metabolic processes of multiple cell types, and also influencing cell senescence and apoptosis.

The broad range of genes whose expression is modified by TH status makes studying the influence of TH in developmental programming a difficult task. In addition, during mammalian development, TH action in a given cell is highly dynamic and dependent on changing TH serum levels and its cell-specific complement of transporters, deiodinase enzymes and TRs. All these factors contribute to deliver precise and timely levels of TH action to developing tissues, which is critical for normal outcomes. Alterations in TH availability during developmental periods can cause irreversible defects in the structure and morphology of cell and tissues, severely impacting the function of the physiological systems involved. At the same time, developmental abnormalities in THs may also impact adult tissue physiology without apparent or gross structural defects. These cases suggest a role for TH in the developmental programming of adult pathophysiology, a role that may have an underlying epigenetic basis. Past and recent reports in rodent and human models have also revealed abnormalities in descendants of individuals that experienced altered TH states at some time point during their lives, especially in early development, suggesting that ancestral TH levels can cause intergenerational epigenetic effects and affect phenotypic traits in later generations.

Here we briefly review the factors that determine TH action, and stress the remarkable dynamism and precision required to orchestrate TH action during development. We then review observations supporting a role for developmental TH action in determining adult physiological traits, via presumed or demonstrated association with altered epigenetic programming. Finally, we make an appraisal of available data in rodents and humans showing intergenerational epigenetic effects resulting from altered TH states.

1.1. Thyroid hormone mechanisms of action.

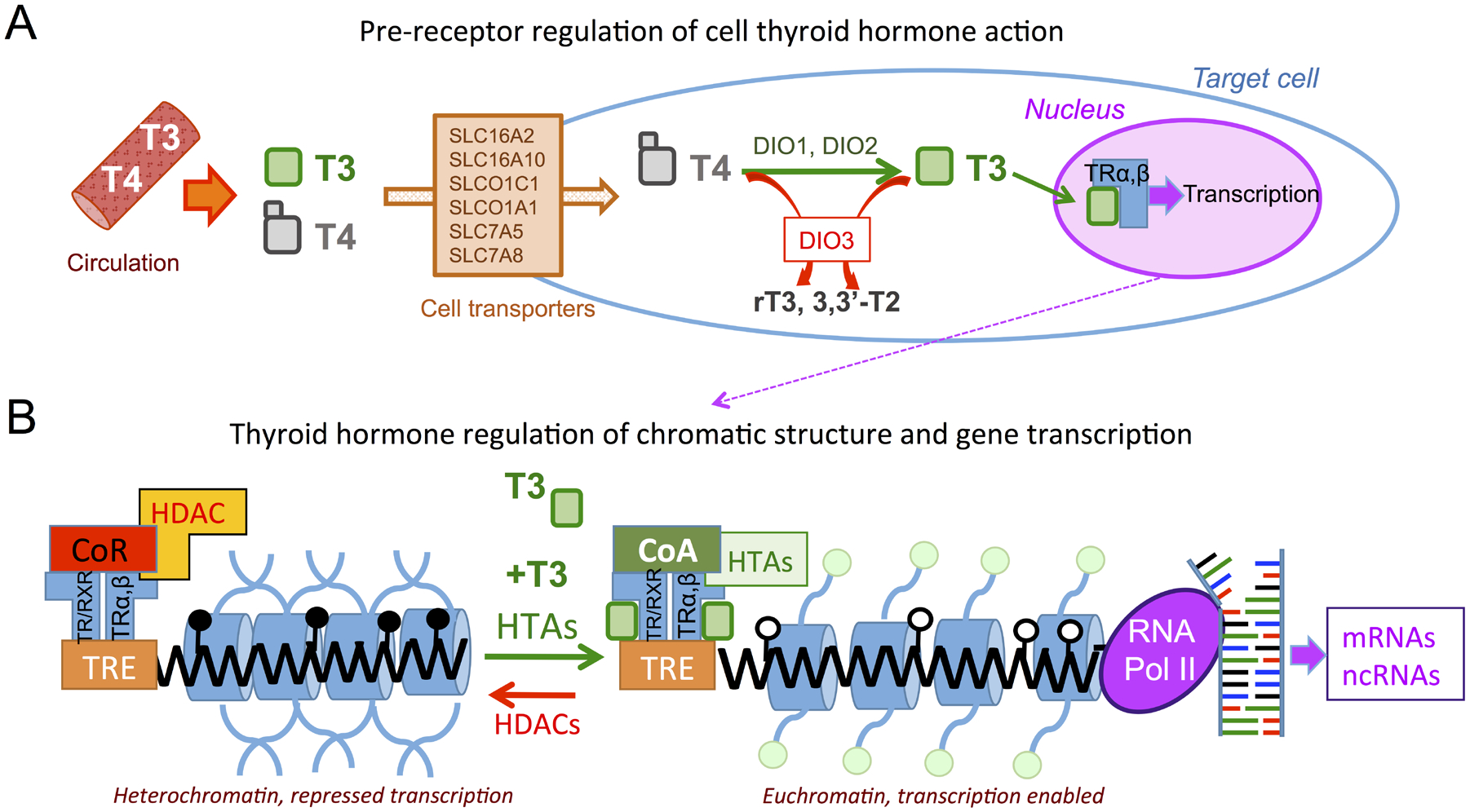

Two major hormones are produced and secreted into the circulation by the thyroid gland: thyroxine (T4, or 3,5,3’,5’-tetraiodothyronine) and 3,5,3’-triiodothyronine (T3). T4 and T3 in the circulation can enter target cells via different cell membrane transporters (Figure 1A). These transporters exhibit different affinities for T4 and T3 and their abundance varies across tissues and developmental stages (Groeneweg, van Geest, Peeters, Heuer, & Visser, 2020; Schweizer & Kohrle, 2013; Wirth, Schweizer, & Kohrle, 2014). Thus, after hormone levels in the circulation, the complement of TH transporters in a given tissue or cell type represents a second modulatory step in cellular TH action.

Figure 1.

Regulation of thyroid hormone action. A, Thyroid hormones T4 and T3 secreted into the circulation by the thyroid gland can enter target cells through different cell membrane transporters. Deiodinases 1 and 2 (DIO1 and DIO2) can convert T4 into the active hormone T3, which will bind nuclear receptors alpha and beta (TRα, β) and regulate gene transcription. Cellular T4 and T3 can be converted into inactive metabolites by deiodinase 3 (DIO3). B, In the absence of T3, unliganded receptors promote close chromatin by recruiting co-repressors and histone deacetylases (HDACs), as well as promoting methylation or TH response elements (TREs) in the genome. Upon T3 binding to the receptors, which may act as homodimers or heterodimers with retinoid X receptor (RXR), co-activators and histone acetylases (HTAs) are recruited and DNA de-methylation may occur, opening chromatin to transcription factors and RNA polymerase II, and promoting transcription of target genes, some of which may include epigenetic modifiers such as microRNAs and histone and DNA methyl-transferases. Close and open lollipops indicate DNA methylation or lack of it, respectively. Green circles represent histone acetylation (modified from (Anselmo & Chaves, 2020)).

Although T4 is secreted by the thyroid gland at a higher amount than T3, and is therefore more abundant in the circulation, it is largely considered a pro-hormone, as its affinity for TRs is only 10% of that of T3. Despite T4 higher abundance, TH action can be enhanced in target tissues by the conversion of T4 to the most active hormone, T3. This conversion is catalyzed by the action of type 1 and 2 deiodinase enzymes (DIO1 and DIO2, respectively) (Bianco, Salvatore, Gereben, Berry, & Larsen, 2002; Dentice, Marsili, Zavacki, Larsen, & Salvatore, 2013; St Germain, Galton, & Hernandez, 2009). (Figure 1A). Increased activity of DIO1 or DIO2 may contribute to increase cellular T3 levels, augmenting TH action. On the other hand, both T4 and T3 can also be converted into metabolites with negligible affinity for the TRs as the result of the action of the type 3 deiodinase (DIO3), whose activity thus decreases T4 and T3 concentrations and subsequent T3 availability. Thus, the deiodinase enzymes present in a target tissue are positioned to enhance or reduce T3 availability, and represent a critical modulatory step in the regulation of cellular TH action.

Most known biological effects of THs result from the classic, canonical mechanism of action (Flamant et al., 2017). This involves the binding of T3 to TRs. These receptors are transcription factors capable of binding DNA (Flamant & Gauthier, 2013; Forrest & Vennstrom, 2000; Ramadoss et al., 2014), and generally act as transcriptional repressors in the absence of hormone. However, when T3 is present and upon T3 binding, TRs alter their conformation and promote the recruitment of different cofactors, which may include histone acetylases and other epigenetic modifiers, ultimately leading to changes in chromatin structure and the transcription of target genes (Cheng, Leonard, & Davis, 2010; Fondell, 2013; Pascual & Aranda, 2013)(Figure 1B).

In recent years, in vitro and in vivo studies have identified non-canonical mechanisms for the action of THs (Davis, Leonard, Lin, Leinung, & Mousa, 2018; Flamant et al., 2017). These mechanisms are not fully understood and investigations are ongoing to define in full their significance for pathophysiology (Davis et al., 2018; Galton, Martinez, Dragon, St Germain, & Hernandez, 2021; Hönes et al., 2017; Latteyer et al., 2019). For the purpose and topic of the present article, we consider the canonical actions of T3 via nuclear TRs and the resulting modifications they elicit in chromatin landscapes and transcriptional readiness (Figure 1B), as the main mechanism by which THs establish the epigenetic modifications that mediate developmental programming phenomena in the affected individuals and in their descendants.

1.2. Thyroid hormones during development.

The ubiquitous presence of TRs (alpha and beta isoforms, or TRα or TRβ) (Carosa, Lenzi, & Jannini, 2018) renders most mammalian tissues susceptible to TH action, and explains TH effects on heart (Johansson, Gothe, Forrest, Vennstrom, & Thoren, 1999), bone (Williams & Bassett, 2018), hepatic lipid physiology and metabolism (Astapova et al., 2014; Feng, Jiang, Meltzer, & Yen, 2000; Russo, Salas-Lucia, & Bianco, 2021), brain function (Bernal, 2005), adipose tissues (Golozoubova et al., 2004; Lin et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2015; Rubio, Raasmaja, Maia, Kim, & Silva, 1995), intestinal function (Chaker, Bianco, Jonklaas, & Peeters, 2017) and skeletal muscle homeostasis (Dentice et al., 2014; Salvatore, Simonides, Dentice, Zavacki, & Larsen, 2014). In addition, T3 action has marked effects on energy expenditure, as it promotes cell lipid metabolism and mitochondrial function (Sinha & Yen, 2016) and impacts systems involved in the central regulation of energy balance (Lopez, Varela, Vazquez, & al., 2010; Wu, Martinez, St Germain, & Hernandez, 2017).

In addition to their broad impact on multiple adult physiological systems, the regulation of TH action is of particular importance during development. Hypothyroidism during this period may result in substantial growth abnormalities, congenital defects and severe neurological delays (Legrand, 1984, 1986). THs influence many cell developmental processes, generally regulating the proliferation (Dentice et al., 2014; Fumel et al., 2012; Verga Falzacappa et al., 2009; Wen, He, Sifuentes, & Denver, 2019) and differentiation of many different cell types across tissues (Baas et al., 1997; Bernal, 2005; Desjardin et al., 2014; Gould, Frankfurt, Westlind-Danielsson, & McEwen, 1990; Pascual & Aranda, 2013; Perrotta et al., 2014; Shultz, Wang, Nong, Zhang, & Zhong, 2017).

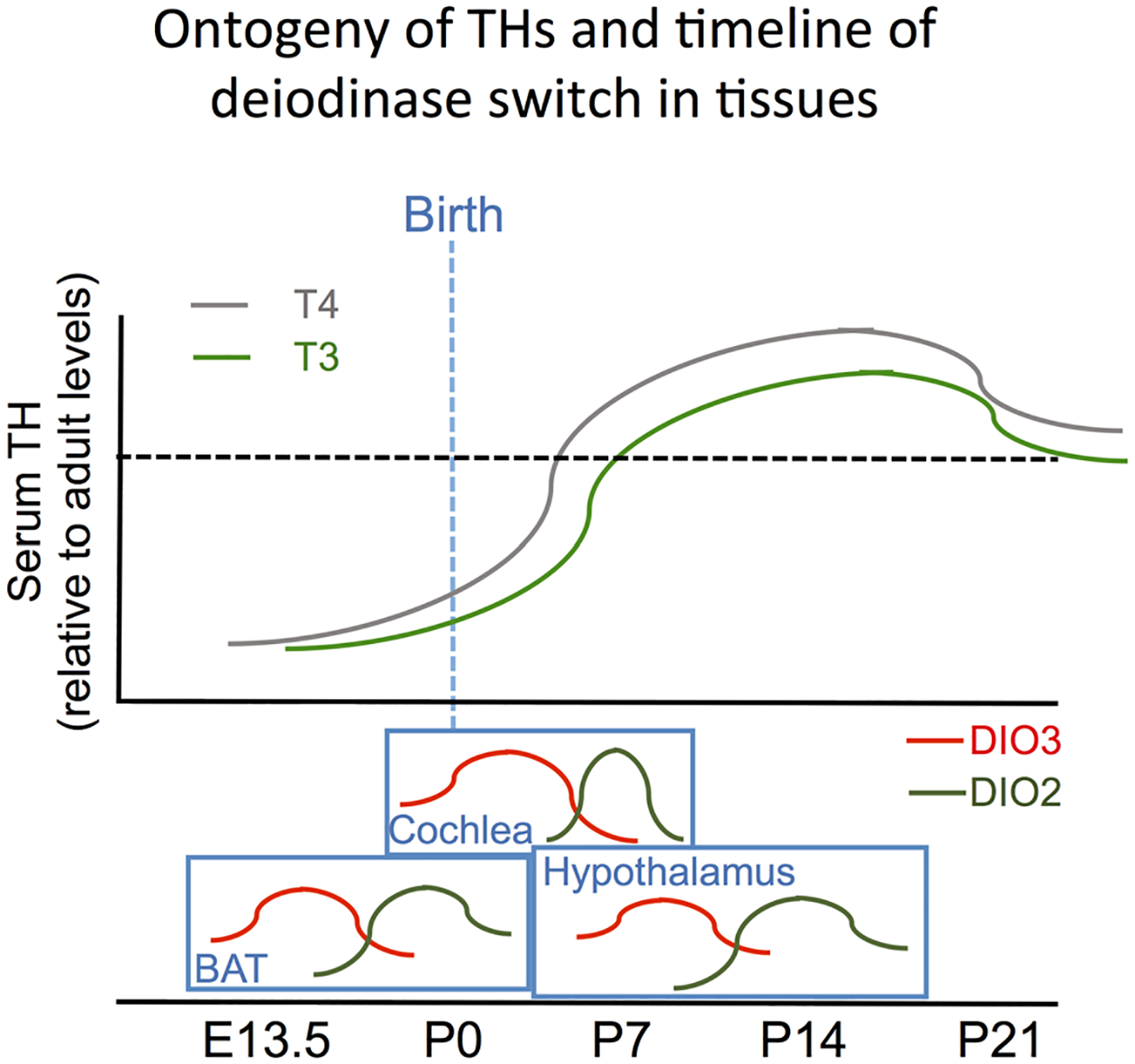

Despite their developmental importance, circulating levels of THs are very low in the mammalian fetus, not reaching adult-like levels until the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis achieves full functionality. This occurs shortly after birth in humans, and around two weeks of age in rodents (Hernandez, Martinez, Ng, & Forrest, 2021) (Figure 2A). Since maternal thyroid hormones can cross the placenta (Contempré et al., 1993), the low circulating levels of THs in the fetus are the result of two main factors. One is the immaturity of the fetal thyroid gland, which does not start functioning in humans until 16–20 weeks of gestational age, and approximately until embryonic day 17.5 (E17.5) in rodents. The other is the high expression of DIO3 in the pregnant uterus (Galton et al., 1999; S. A. Huang, Dorfman, Genest, Salvatore, & Larsen, 2003), placenta (Roti, Fang, Braverman, & Emerson, 1982) and fetal tissues (T. Huang, Chopra, Boado, Solomon, & Chua Teco, 1988), effectively inactivating both T3 and T4 of maternal and fetal origin, and dampening TH action during early development.

Figure 2.

Ontogeny of THs and timing of deiodinase switch in tissues. Serum levels of T3 and T4 are low in rodent early development. They rise steadily after birth and reach a peak during the third week of life, settling on adult levels (dotted line) shortly thereafter. Many tissues exhibit a switch between peaks of DIO3 and DIO2 expression that is independent of serum concentrations of THs, indicating a timely, tissue-specific need for increased T3 action. The approximate timing of the deiodinase switch is indicated for the hypothalamus, BAT and cochlea (Hernandez et al., 2021).

The ontogeny of DIO3 expression is largely complementary of that of DIO2 in different tissues, with DIO3 peaking at earlier developmental stages and DIO2 reaching highest activity later in neonatal life (Hernandez et al., 2021) (Figure 2A). This 2-step profile of low-then-high T3 availability constitutes an important developmental switch in TH action that, when disrupted in mice, leads to many pathologies (recently reviewed in (Hernandez et al., 2021)) affecting perinatal viability, brain development, behavior, sensory function, skin maturation, fertility, endocrine physiology and craniofacial and heart development (Martinez, Pinz, et al., 2022). The ordered sequence of developmental peaks in DIO3 and DIO2 expression are present to some extent in many tissues, and exhibit tissue-specific timelines (Hernandez et al., 2021), strongly underscoring the organismal requirements for timely and effective modulation of TH action to suit cell developmental processes in a tissue-specific manner.

Similarly, scattered evidence from multiple tissues not detailed here indicates pronounced developmental patterns of expression for transporters and TRs. For example, testicular expression of TRα and the T3-specific MCT8 transporter are highest during neonatal life, preceding the serum peak in THs (Hernandez, 2018). These profiles suggest that developing tissues are ready for T3 action as soon as circulating and local T3 levels rise as a result of thyroid axis maturation, timely decline of DIO3 activity, and increased DIO2 expression.

In summary, TH action in developing tissues is determined by multiple, coordinated contributions of serum hormones and their transporters, deiodinases and receptors. These contributions are designed to provide the timely and precise levels of TH signaling needed to support developmental processes of cell proliferation and differentiation. Considering the well-orchestrated control of TH action during development and the mechanisms by which T3 modifies chromatin and epigenetic landscapes (Guan et al., 2017), developmental stages represent periods of unique susceptibility to altered T3 action and to the T3-dependent establishment of epigenetic signatures that exert sustained influence into adult life. In addition, T3 can also directly regulate the expression of histones (Martinez, Lary, Karaczyn, Griswold, & Hernandez, 2019) and DNA methyl-transferase genes (Kyono, Sachs, Bilesimo, Wen, & Denver, 2016; Raj et al., 2020), extending the mechanisms by which T3 influences the epigenome. Thus, altered TH states during particular milestones in the development of specific tissues may cause changes in the epigenetic information of cells, leading in adulthood to abnormal physiology and increased susceptibility to endocrine abnormalities and other pathologies.

2. Developmental epigenetic programming by thyroid hormones

In mammalian models, abnormalities in TH action during developmental stages are associated with a vast array of functional deficits comprising multiple biological systems. Some of those pathologies result from irreversible defects in organ and tissue morphology, and should be considered congenital defects rather that developmental epigenetic programming. However, other abnormalities, especially those associated with the physiology of certain organs and endocrine systems, may not be explained by gross tissue defects, and could be the consequence of changes in the epigenome of particular cells or tissues. Published work has described adult physiology alterations in pharmacological or genetic rodent models of abnormal TH action during developmental periods. In many instances, observations from these studies likely represent a case in which THs elicit an effect of developmental programming, as originally described by Waddington (Waddington, 1957, 1959). These observations likely reflect underlying modifications in epigenetic marks in association with the outcomes, but studies that directly address the epigenetic signatures involved -with some exceptions- are still largely elusive. Here, we briefly review selected work supporting a role for developmental TH states in the programming of adult pathophysiology.

2.1. Long-term consequences of TH abnormalities during developmental stages

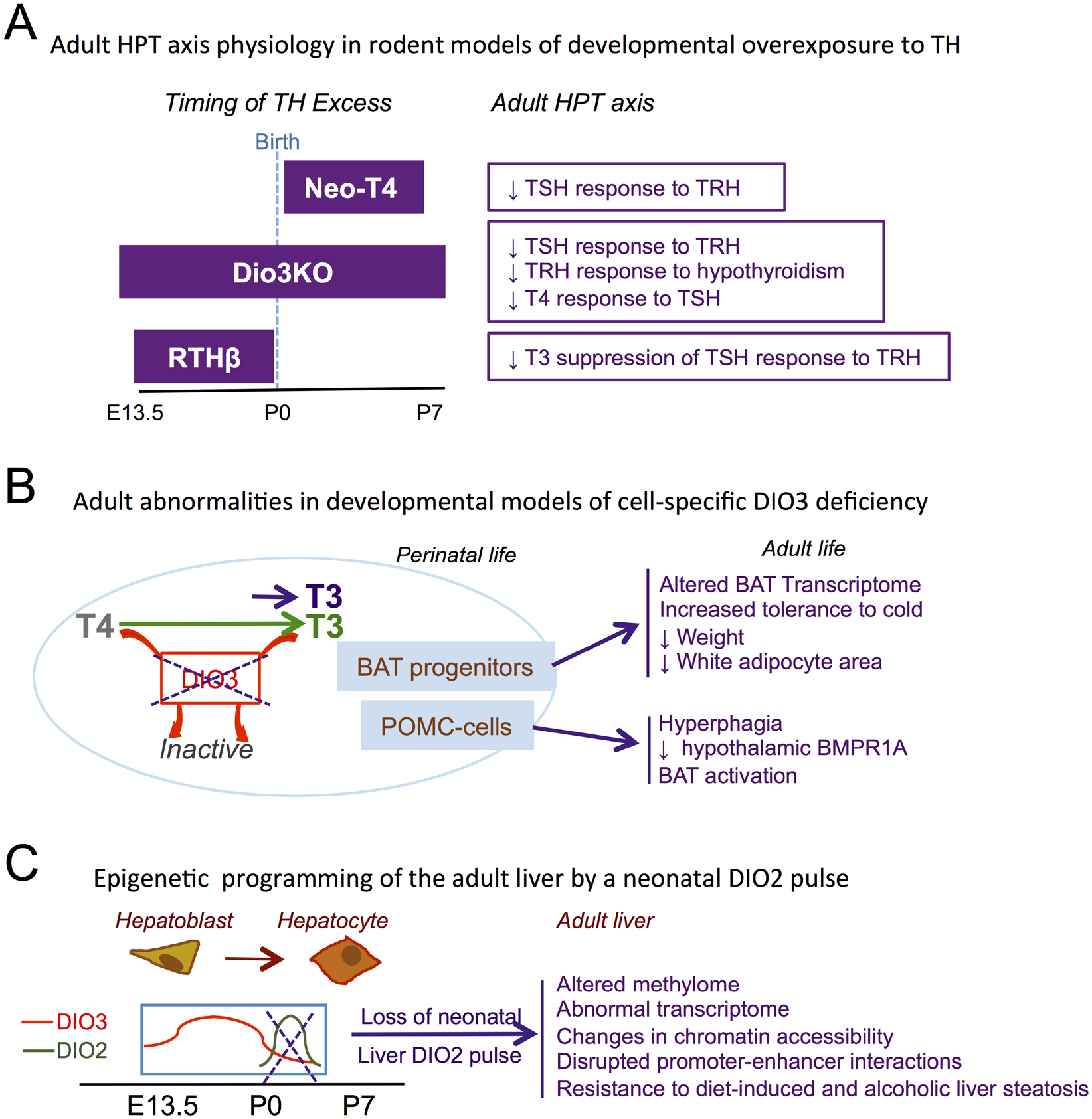

TH abnormalities during developmental stages may impact the epigenetic programming leading to persistent alteration in the HPT set point and in the normal TH range. Seminal observations in this regard were made using a rat model of serial injections of pharmacological doses of T4 during the first days of neonatal life. These rats exhibited a syndrome (“neo-T4 syndrome”) that included central hypothyroidism and a decreased response of the pituitary to a TRH injection (J. L. Bakke, Lawrence, & Robinson, 1972; J. L. Bakke, Lawrence, & Wilber, 1974). Similarly, Dio3 null mice experience developmental thyrotoxicosis due to lack of adequate TH clearance by DIO3 (Hernandez, Martinez, Fiering, Galton, & St Germain, 2006; Martinez, Pinz, et al., 2022), leading to abnormalities in adult HPT axis physiology, including central hypothyroidism, reduced pituitary response to TRH and lack of TRH response in the hypothalamic PVN to induced hypothyroidism (Hernandez, Martinez, et al., 2007). Mice and humans with developmental overexposure to THs due to a heterozygous mutation in the TRβ also manifest a less suppressible response of TSH to TRH after T3 administration despite being euthyroid (Pappa et al., 2017). Moreover, mice with TR deficiency exhibit increased sensitivity to TH in adult life (Macchia et al., 2001). These observations are strongly supportive of a role of TH status in the developmental epigenetic programming of the HPT axis and sensitivity to TH, with developmental hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism leading, respectively, to increased or reduced sensitivity to TH in adult life (Figure 3A). TH administration during development can also cause physiological effects in other tissues. For example, in pregnant mice, a physiological dose of T4 during first or second half of pregnancy lead to significant alterations in cardiovascular functions in the adult offspring (Pedaran et al., 2021).

Figure 3.

Developmental overexposure to TH and adult physiology. A, Developmental interval of TH overexposure and adult defects in HPT axis physiology for Neo-T4, Dio3KO and RTHβ rodent models. B, Adult abnormalities in mouse models of cell-specific thyrotoxicosis due to loss in of DIO3 function in brown adipocyte progenitors and POMC-expressing cells. C, Alterations in epigenetic signature, transcriptome and disease susceptibility in the adult liver of mice lacking a neonatal pulse of T3 action secondary to DIO2 activation. E13.5, embryonic day 13.5; P0, P7, postanatal day 0, 7, respectively. (Based on references cited in the main text).

In addition to systemic alterations in TH status, TH overexposure in specific cell types also leads in adulthood to phenotypes of relevance to the exposed cells (Figure 3B). For example, DIO3 is highly expressed in proliferating brown adipose tissue (BAT) progenitor cells (Hernandez, Garcia, & Obregon, 2007). BAT-specific inactivation of DIO3 causes augmented T3 action in developing BAT, premature differentiation of brown adipocytes and accelerated brown adipogenesis in the fetus, with increased expression of BAT markers Ucp1, Dio2 and Cidea (Fonseca, Russo, Luongo, Salvatore, & Bianco, 2022). This embryonic alteration in BAT T3 action leads to broad changes in the adult BAT transcriptome, including genes involved in mitochondrial function and glucose homeostasis, and to an improved response to cold, with animals better maintaining core temperature and body weight (Fonseca et al., 2022)(Figure 3B). Although epigenetic marks were not studied, these observations suggest an epigenetic basis for the programming of BAT function by elevated T3 action in fetal BAT.

Similarly, DIO3-deficiency targeted to propio-melanocortin (POMC)-expressing cells also leads to adult physiological programming. Adult mice with DIO3 deficiency specifically in POMC-expressing cells, which are already present during early development, exhibit hyperphagia, reduced expression of bone morphogenetic receptor 1A (BMPR1A) across different hypothalamic nuclei (Wu, Martinez, DeMambro, Francois, & Hernandez, 2022) (Figure 3B). This is associated with BAT activation (Wu et al., 2022), which is consistent with findings in a mouse model of BMPR1A deficiency in POMC-cells (Townsend et al., 2017). Again, this finding suggests that T3 action in developing POMC cells plays a role in the programming –possibly epigenetic- of adult hypothalamic physiology, with functional consequences for energy balance.

No underlying adult epigenetic abnormalities have been yet investigated in the models reviewed above, but an altered epigenetic signature has been comprehensively examined in a mouse model of liver-specific DIO2 deficiency (Figure 3C). Although DIO2 activity in the liver is negligible in most developmental and adult stages, a modest but distinctive and short-lived peak of hepatic DIO2 expression is present in the newborn mouse (Fonseca et al., 2015), suggesting a timely need for enhanced T4 to T3 conversion and subsequent T3 action in the developing liver. Ablation of this neonatal DIO2 activity resulted in alterations in the methylome and transcriptome of the adult liver (Fonseca et al., 2015). This altered epigenetic programming of the adult liver caused by the absence of timely T3 signaling in the newborn markedly affects the Foxo1-Inducible Transcriptional Repressor Zfp12 (Fernandes et al., 2018), and has important pathological consequences. Adult mice with hepatic-specific DIO2 deficiency exhibited increased resistance to obesity (Fonseca et al., 2015), and their livers were resistant to steatosis (Fonseca et al., 2015), hypercholesterolemia (Fernandes et al., 2018) and alcoholic fatty liver (Fonseca et al., 2019)(Figure 3C). These results are consistent with the known effects of T3 in hepatic gene regulation, chromatin remodeling, and autophagy (Singh, Sinha, Ohba, & Yen, 2017), and demonstrate that the transient activation of TH in the newborn rodent is critical to establish the long-term epigenetic marks (DNA methylation and chromatin accessibility) that are necessary for normal hepatic function in adulthood (Fonseca, Garcia, Fernandes, Nair, & Bianco, 2021).

In addition to their epigenetic regulation and programming of target genes, THs can also regulate the expression of genes directly involved in the establishment of epigenetic modifications. For example, in mouse neuronal cells, T3 binding to TRs transactivates the DNA Methyltransferase 3a Gene (Kyono, Subramani, et al., 2016), which influences de novo methylation and subsequent expression levels of developmental genes. To close the circle, some epigenetic modifiers can themselves target genes that influence levels of TH action, including Dio2 and, specially, Dio3. During myogenesis, lysine-specific demethylase influences the epigenetic control of Dio2 and Dio3 expression (Ambrosio et al., 2013).

As for Dio3, which is critical to dampen T3 action during development, being a subject of genomic imprinting (Charalambous & Hernandez, 2013), renders Dio3 expression and DIO3-dependent T3 signaling levels susceptible to disruption of the finely tuned epigenetic mechanisms that control allelic expression in imprinted loci (Sittig & Redei, 2014). Its variable allelic expression ratios in different tissues (Martinez et al., 2014) make Dio3 the center of an epigenetic loop: Epigenetic mechanisms regulate the imprinting, i.e. allelic expression of Dio3, which in turn regulates TH availability and the subsequent epigenetic modifications resulting from changes in TH signaling (Hernandez & Stohn, 2018).

Overall, these works support an important role of developmental TH states in the epigenetic programming of multiple tissues, although in most cases the specific epigenetic signatures responsible for the observed pathophysiology remain to be identified.

3. Intergenerational epigenetic effects of thyroid hormones

3.1. The rat Neo-T4 model.

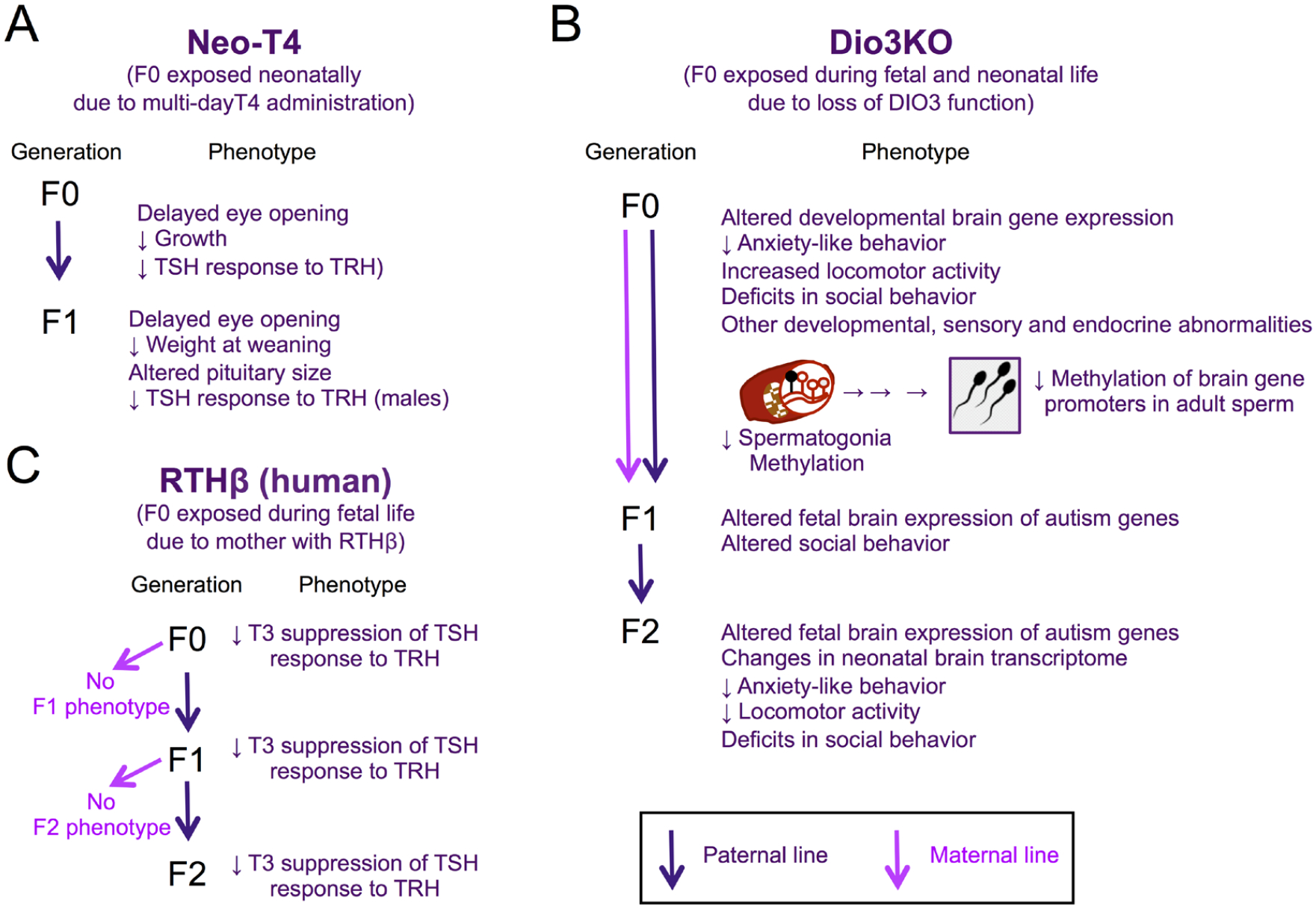

To our knowledge, the first observation of an intergenerational epigenetic effect of THs was reported by Bakke utilizing a rat neo-T4 model. These rats exhibited growth retardation and, as mentioned above, developed adult central hypothyroidism, deficient pituitary response to TRH and reduced testis size (J. L. Bakke et al., 1972; J. L. Bakke et al., 1974). Interestingly, Bakke observed that the untreated progeny of male Neo-T4 rats also manifested delays in developmental milestones, as well as comparable defects in endocrine organs and the physiology of the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis (J.L. Bakke, Lawrence, Robinson, & Bennett, 1977) (Figure 4A). Although the word “epigenetic” was barely used at the time, Bakke’s observations suggested that neonatal thyrotoxicosis caused these males to transmit to their offspring additional biological information not included in their genetic code.

Figure 4.

Inter- and trans-generational epigenetic effects in different models of developmental overexposure to TH. Phenotypes in the exposed generation (F0) and F1 and F2 generations of Neo-T4 rats (A), Dio3ko mice (B) and humans born to RTHβ mothers. (Based on references cited in the main text).

Bakke and colleagues also studied the offspring of rats made hypothyroid in adulthood by thyroidectomy. They noted again abnormalities in growth developmental milestones, endocrine organs and HPT axis physiology (J. L. Bakke, Lawrence, Robinson, & Bennett, 1976). In both models, he observed that some of the abnormal outcomes varied between males and females. Although these observations were difficult to interpret at the time, Bakke’s seminal work showed that altered TH states, both during development and in adult life, lead to sexually dimorphic intergenerational epigenetic effects on the offspring.

3.2. The DIO3KO mouse model.

As indicated above, Dio3KO mice exhibit thyrotoxicosis during fetal and early neonatal life due to impaired TH clearance (Hernandez et al., 2006; Martinez, Pinz, et al., 2022). The resulting phenotypic abnormalities (e.g., growth retardation, small testes, central hypothyroidism and poor pituitary response to TRH) are comparable to those of the neo-T4 rat, but substantially more severe (Hernandez et al., 2006; Hernandez, Martinez, et al., 2007; Martinez, Karaczyn, et al., 2016; Martinez, Pinz, et al., 2022). This is probably because the thyrotoxicosis elicited by DIO3-deficiency is steadier and more consistent, as well as longer (Figure 3A), comprising both fetal and neonatal stages (Hernandez et al., 2006; Martinez, Pinz, et al., 2022).

Following up on Bakke’s seminal work, it was not surprising that the descendants of Dio3KO mice also exhibited phenotypic abnormalities. Studies on F2 generation descendants of Dio3KO male or female mice along the paternal line showed marked gene expression changes in several brain regions at two weeks of life (Martinez et al., 2020). These descendants were genetically normal and born to unrelated genetically normal mothers, suggesting the abnormal gene expression profile was of heritable epigenetic origin. These changes in neonatal brain gene expression profiles were associated in adulthood with alterations in behavioral traits, including decreased anxiety-like behavior, increased marble burying behavior, reduced levels of physical activity (Martinez et al., 2020), as well as deficits in sociability and social novelty interest (Martinez, Stohn, Mutina, Whitten, & Hernandez, 2022). The association suggests the altered brain gene expression observed during neonatal life is of consequence to behavioral characteristics of important relevance to neurodevelopmental disorders in humans (Figure 4B).

Interestingly, the altered profiles of gene expression in the brain of F2-generation neonates showed a large –but not complete- overlap between neonates descending from an exposed (Dio3KO) male or female (Martinez et al., 2020). This indicates substantial commonalities in how males and females translate developmental thyrotoxicosis into changes in the epigenetic information of their germ lines, while still allowing for the existence of some sex-specific effects in this regard (Figure 4B).

In efforts to identify mechanisms underlying the intergenerational epigenetic effects of TH overexposure, investigators have shown that Dio3 is particularly active in the developing testis during perinatal life (Martinez, Karaczyn, et al., 2016). Its expression is specifically located in undifferentiated spermatogonia (Martinez et al., 2019), from which it also influences TH signaling in other types of testicular cells. This suggests a need for the male germline to be protected from excessive levels of TH signaling, as the expression of spermatogonia-specific genes are altered in the testis of Dio3ko mouse neonates (Martinez et al., 2019)(Figure 4B). Remarkably, there is a broad decrease in DNA methylation in the testicular cells of Dio3KO newborns, and this hypomethylation also affects spermatogonia (Martinez et al., 2020). Moreover, genome-wide profiling of DNA methylation in adult Dio3KO sperm revealed extensive methylome alterations (Martinez et al., 2020). Although overall average methylation levels were not markedly changed, investigators observed substantial hypomethylation of CpG islands in the vicinity of many gene promoters (Martinez et al., 2020). Interestingly, the most affected genes exhibited a high degree of specific expression in the developing and adult central nervous system, and disease ontology analyses indicated enrichment in genes related to schizophrenia, autism, addiction and cancer (Martinez et al., 2020). Of note, several top autism-candidate genes exhibiting promoter hypomethylation in the sperm of TH-overexposed mice showed abnormal expression in F1 and F2 generation descendants as early as embryonic day 13.5 (Martinez, Stohn, et al., 2022). Overall, these studies suggest that the intergenerational epigenetic effects of TH influence brain developmental processes since very early stages, raising the possibility that abnormal TH status in previous generations may contribute, via intergenerational epigenetic effects, to the non-genetic etiology of neurodevelopmental disorders (Escher et al., 2021)(Figure 4B).

Thus, a modified sperm DNA methylation profile and its subsequent influence in the developmental processes of the next generation after fertilization, is probably one of the mechanisms by which aberrant TH states elicit intergenerational epigenetic effects. Other unidentified mechanisms may also contribute. The spermatogonial localization of DIO3 makes a compelling case for a role for this gene as a gatekeeper of TH signaling in the germ line, and the subsequent epigenetic information that is transmitted to the developing offspring (Hernandez, 2021).

3.3. Transgenerational epigenetic effects of THs in humans.

The first observation of transgenerational epigenetic effects of TH in humans have been described in patients with resistance to TH receptor beta (RTHβ) syndrome, an inherited disease transmitted in an autosomal, dominant manner. It is characterized by a reduction in the sensitivity of organs and tissues to the action of thyroid hormones underlying a mutation in the TRβ gene (THRB). Despite having elevated serum levels of free T3 and T4, these patients remain asymptomatic in most cases. In this sense, the study of women with RTHβ is a unique opportunity to evaluate in humans the direct effect of excess maternal THs on the fetus, without the concurrent effect of TH excess in the mother and the influence of antibodies associated with autoimmune diseases of the thyroid.

Anselmo et al (Anselmo, Cao, Karrison, Weiss, & Refetoff, 2004) studied an extensive family with RTHβ syndrome originating and residing on the island of S. Miguel-Azores (Portugal). They retrospectively examined the evolution of pregnancies in this family, including the incidence of miscarriages, which together with the determination of the genotype of all live births, their birth weight, and thyrotropin (TSH) values, allowed them to assess the influence of elevated maternal TH levels on fetal development. Animal models of RTHβ were used to elucidate specific questions about pregnancy in these situations, as well as the long-term effects of intrauterine exposure to high levels of maternal THs. Mothers with RTHβ syndrome had a significantly higher incidence of miscarriages and, surprisingly, aborted a higher proportion of genetically normal (wild type, WT) fetuses than those carrying the mutation. Only WT neonates born to mothers with RTHβ had a suppressed neonatal TSH and low birth weight (<2500 g). In WT adults born to mothers with RTHβ, the TSH response to TRH was less suppressed by the administration of liothyronine (LT3). Similarly, normal rats exposed in utero to high levels of THs (offspring of mothers with RTHβ) not only showed lower sensitivity to THs but also exhibited significantly higher expression of Dio3 mRNA in the anterior pituitary (Srichomkwun et al., 2017). Since DIO3 function is precisely to convert T3 and T4 into inactive metabolites, increased Dio3 expression in the pituitary gland in RTHβ rats could be a mechanism contributing to the pituitary insensitivity to THs.

Remarkably, further studies in this Azorean family showed the impaired T3 suppression of the TSH response was also found in genetically normal descendants for two more generations along the paternal line, but the phenotype disappeared along maternal descendants (Anselmo, Scherberg, Dumitrescu, & Refetoff, 2019)(Figure 4C). Given the relative isolation of this population, the studies across multiple generations and the precisely defined phenotype analyzed, this work provides a robust demonstration that altered exposure to TH can also produce intergenerational epigenetic effects in humans. Despite the differences in experimental models, the abnormal central regulation of the thyroid axis as a consequence of ancestral developmental overexposure to TH is reminiscent of the observation in the descendants of rats with the neo-T4 syndrome, suggesting common mechanisms in mammals for the transgenerational epigenetic effects of THs.

4. Mechanisms of intergenerational epigenetic effects by THs

In a well-defined laboratory setting, where confounding factors are minimized, the appearance of a particular phenotype in the offspring or descendants of an animal exposed to a particular insult strongly suggests an epigenetic origin. The potential mechanism likely involves the alteration of the epigenetic information of the germ line of the exposed ancestor. An abnormal epigenetic signature in the germ cell will then influence the developmental programs in the embryo and lead to abnormal phenotypes.

After fertilization, DNA is de-methylated genome-wide and new methylation patterns are established. However, methylation of imprinted domains, which contain genes with parental-specific allelic expression, escape de-methylation (Reik & Walter, 2001; SanMiguel & Bartolomei, 2018). Likewise, it has been shown in some cases that certain environmental exposures cause methylation marks that are resistant to de-methylation and are also maintained in the embryo, potentially contributing to the intergenerational epigenetic effects observed as a result (Rousseaux et al., 2020). In normal conditions imprinted genes escape zygote de-methylation and their finely tuned regulation of allelic expression depends on allele-specific methylation (Reik & Walter, 2001). These characteristics of imprinted genes render them particularly vulnerable to environmental exposures and likely mediators of aberrant intergenerational epigenetic effects (Jirtle, Sander, & Barrett, 2000; Jirtle & Skinner, 2007).

In addition, it is important to note that germ line epigenetic information not only includes DNA methylation (Garrido et al., 2021), but also chromatin modifications, microRNA abundance (Dickson et al., 2018; Rodgers, Morgan, Leu, & Bale, 2015) and concentrations of metabolites and other small RNAs (Carone et al., 2010; O’Doherty & McGettigan, 2015; Rando, 2016; Sharma et al., 2016; Short et al., 2016). Thus, increased abundance of particular microRNAs or metabolites in the sperm may affect gene expression in the embryo after fertilization.

In the context of THs, it is important to note that T3 excess in mice causes hypomethylation in neonatal spermatogonia, and that hypomethylation is still observed in selected CpG islands of adult sperm DNA (Martinez et al., 2020). In addition, the spermatogonial expression of DIO3 (Martinez et al., 2019) places this gene in a central position to regulate the germ line TH-dependent epigenetic information that is transmitted to the next generation (Hernandez, 2021; Hernandez & Martinez, 2020).

Although the observations above present a compelling case for a direct effect of T3 on the germ line, we cannot discard that these effects are partly mediated by other factors. Many environmental exposures cause intergenerational epigenetic effects, including inflammatory states, diets, stress, social interactions, endocrine disruptors, altered metabolism and others (Heard & Martienssen, 2014; Prokopuk, Western, & Stringer, 2015; Somer & Thummel, 2014; Trerotola, Relli, Simeone, & Alberti, 2015). Considering the broad physiological effects of THs, especially those on metabolism and neurological function, it is possible that germ line epigenetic signatures caused by aberrant T3 action are partly the result of changes in other metabolic or hormonal systems that in turn impact the germ line.

In terms of the genes that may be affected by the intergenerational epigenetic effects of THs and can also explain the phenotypic outcomes, one obvious target is Dio3. As an imprinted gene, Dio3 is preferentially expressed from the paternal allele in human foreskins (Martinez, Cox, Youth, & Hernandez, 2016) and most mouse fetal tissues (Hernandez, Fiering, Martinez, Galton, & St Germain, 2002), although this preferential allelic expression is relaxed later in life and as well as in some endocrine organs (Martinez et al., 2014). As Dio3 is highly expressed in spermatogonia and also strongly regulated by T3 (Barca-Mayo et al., 2011; Hernandez, Morte, Belinchon, Ceballos, & Bernal, 2012; Tu et al., 1999), it is possible that T3 excess epigenetically modifies the imprinted Dio3 locus in the germ line so that later generations exhibit altered Dio3 expression. The contribution of epigenetically abnormal expression of Dio3 is compatible with observations in a mouse model of developmental TH excess due to TRβ resistance (Anselmo & Chaves, 2020). Offspring of exposed mothers show decreased pituitary sensitivity to T3, which is associated with increased pituitary expression of Dio3 (Srichomkwun et al., 2017). In this particular phenotype, it is thus possible that increased TH clearance by Dio3 partly explains the reduced pituitary sensitivity to T3. An abnormal epigenetic regulation of Dio3 is a mechanism that may mediate other phenotypes resulting from TH-dependent intergenerational epigenetic effects. Given the extensive pathophysiological consequences of altered DIO3 activity (Hernandez et al., 2021), intergenerational changes in its epigenetic regulation since early development may have broad impact on phenotypic outcomes. Some of these may also include changes in spermatogonial Dio3 expression, which will perpetuate altered epigenetic inheritance in successive generations.

A conceivable complementary mechanism potentially explaining phenotypic features in descendants of TH-exposed individuals may include direct epigenetic programming of a subset of T3-responsive genes (including Dio3). As T3 exhibits a large targetome (Zekri, Guyot, & Flamant, 2022), it is possible that some T3-responsive genes are epigenetically reprogrammed by T3 excess. The epigenetic marks associated with this reprogramming could be maintained in the next generation, and lead to alterations in the baseline expression and physiological ranges of regulation of affected genes.

Additional mechanisms may also apply. They may relate to other types of germ line epigenetic information (small RNA profiles, histone modifications, etc.). Some phenotypic effects may also be the integrative result of effects on multiple physiological systems, exerting enhancing or compensatory actions on phenotypic outcomes.

Finally, it is not clear to what extend the epigenetic signatures of the female and male germ lines respond to T3 excess, whether their germ lines show different epigenetic susceptibility, or to what extent this susceptibility varies with the developmental stages of exposure. Answering these questions may help in understanding how intergenerational epigenetic effects are inherited along the paternal and maternal lineages. Much work is still needed to understand what happens between an ancestral exposure to TH and the phenotype of a descendant two or more generations later.

5. Thyroid hormones and epigenetic effects of endocrine disruptors

Although not the focus of the present article, it is relevant to note published work concerning the effects of endocrine disruptors. These are chemicals present in our environment that can mimic the structure and properties of hormones and alter their physiology and action. Chemicals disrupting sex steroid hormones have been most studied (Crews, Gillette, Miller-Crews, Gore, & Skinner, 2014; Krishnan et al., 2018; Skinner, 2014), but the paradigms are also applicable to compounds mimicking glucocorticoids, thyroid hormones and retinoids, as well as lipid-like endogenous ligands of the nuclear hormone receptor super family.

Similarly, some endocrine disruptors can also affect the physiology and action of THs and their dependent outcomes (Leung et al., 2016; Paul et al., 2012; Wadzinski et al., 2014). However, models of endocrine disruption, although relevant to human health, are more difficult to interpret, as the particular disruptor may impact TH physiology at many different levels, as well as other hormonal systems. These environmental chemicals may potentially bind to TRs and have agonistic or antagonistic effects in TRs signaling, but they could also impact the function of TH cell transporters and deiodinases in ways that facilitate or impede TH action. They can also affect total and free levels of TH in the circulation by modifying the capacity of serum binding proteins or the TH signaling involved in the feedback loop regulation of the HPT axis, subsequently regulating TH secretion by the thyroid gland. They can also affect thyroid gland development and hormonogenesis. All these effects may be varied in nature and affect the physiology and action of THs in complex ways. Despite this complexity, it should be considered that the developmental programming and intergenerational epigenetic effects of specific endocrine disruptors with thyromimetic properties may be partially mediated by alterations in TH signaling.

6. Summary

THs have extensive effects on mammalian systems and their disruption have broad implications for pathophysiology. Their pronounced direct and indirect influence on the chromatin landscape and associated epigenetic signatures, and their highly choreographed action during early and late development, place TH in a central position to substantially contribute to the developmental epigenetic programming of adult outcomes. Their action on the germ line can also establish epigenetic signatures that influence embryonic development and adult disease susceptibility in the offspring and subsequent generations. Given the extensive impact of TH on organs and physiological systems, we are still at our infancy in terms of fully comprehending the scope of these phenomena, the mechanisms involved, the phenotypes more likely affected and their parental modes of epigenetic inheritance. There are important implications for disease, as thyroid conditions are highly prevalent in humans, who are also exposed to endocrine disruptors that may influence TH physiology. Thus, developmental and tissue profile of TH action may not only uniquely define adult physiology and disease susceptibility, but also influence health outcomes in descendants. Epigenetic profiles associated with particular early-life or ancestral TH states may be instrumental for future novel approaches in personalized medicine.

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by grants DK095908 and MH096050 from the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and the National Institute of Mental Health, respectively. We thank Prof. Samuel Refetoff (University of Chicago) for his collaboration in the studies of the Azorean family with Resistance to Thyroid Hormone Beta (RTHβ).

Abbreviations

- THs

Thyroid hormones

- T3

3, 5, 3’-triiodothyronine

- T4

3, 5, 3’, 5’-tetraiodothyronine, thyroxine

- TRs

Thyroid hormone receptors

- THRA, THRB

Thyroid hormone receptor alpha, beta

- MCT8

Monocarboxylate transporter 8

- DIO1, DIO2, DIO3

Type 1, 2, 3 deiodinase

- HPT

hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid

- PVN

paraventricular nucleus

- BAT

brown adipose tissue

- POMC

pro-opiomelanocortin

References

- Ambrosio R, Damiano V, Sibilio A, De Stefano MA, Avvedimento VE, Salvatore D, et al. (2013). Epigenetic control of type 2 and 3 deiodinases in myogenesis: role of Lysine-specific Demethylase enzyme and FoxO3. Nucleic Acids Res, 41(6), 3551–3562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anselmo J, Cao D, Karrison T, Weiss RE, & Refetoff S (2004). Fetal loss associated with excess thyroid hormone exposure. Jama, 292(6), 691–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anselmo J, & Chaves CM (2020). Physiologic Significance of Epigenetic Regulation of Thyroid Hormone Target Gene Expression. Eur Thyroid J, 9(3), 114–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anselmo J, Scherberg NH, Dumitrescu AM, & Refetoff S (2019). Reduced Sensitivity to Thyroid Hormone as a Transgenerational Epigenetic Marker Transmitted Along the Human Male Line. Thyroid, 29(6), 778–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astapova I, Ramadoss P, Costa-e-Sousa RH, Ye F, Holtz KA, Li Y, et al. (2014). Hepatic nuclear corepressor 1 regulates cholesterol absorption through a TRbeta1-governed pathway. J Clin Invest, 124(5), 1976–1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baas D, Bourbeau D, Sarliève LL, Ittel M-E, Dussault JH, & Puymirat J (1997). Oligodendrocyte maturation and progenitor cell proliferation are independently regulated by thyroid hormone. GLIA, 19, 324–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakke JL, Lawrence N, & Robinson S (1972). Late effects of thyroxine injected into the hypothalamus of the neonatal rat. Neuroendocrinol, 10, 183–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakke JL, Lawrence N, & Wilber JF (1974). The late effects of neonatal hyperthyoridism upon the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis in the rat. Endocrinology, 95, 406–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakke JL, Lawrence NL, Robinson S, & Bennett J (1976). Observations on the untreated progeny of hypothyroid male rats. Metabolism: Clinical & Experimental, 25(4), 437–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakke JL, Lawrence NL, Robinson S, & Bennett J (1977). Endocrine studies in the untreated F1 and F2 progeny of rats treated neonatally with thyroxine Biol. Neonate, 31, 71–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barca-Mayo O, Liao XH, Alonso M, Di Cosmo C, Hernandez A, Refetoff S, et al. (2011). Thyroid hormone receptor alpha and regulation of type 3 deiodinase. Molecular Endocrinology, 25(4), 575–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal J (2005). Thyroid hormones and brain development. Vitam Horm, 71, 95–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianco AC, Salvatore D, Gereben B, Berry MJ, & Larsen PR (2002). Biochemistry, cellular and molecular biology, and physiological roles of the iodothyronine selenodeiodinases. Endocrine Rev, 23(1), 38–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carone BR, Fauquier L, Habib N, Shea JM, Hart CE, Li R, et al. (2010). Paternally induced transgenerational environmental reprogramming of metabolic gene expression in mammals Cell, 143(7), 1084–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carosa E, Lenzi A, & Jannini EA (2018). Thyroid hormone receptors and ligands, tissue distribution and sexual behavior. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 467, 49–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaker L, Bianco AC, Jonklaas J, & Peeters RP (2017). Hypothyroidism. Lancet, 390(10101), 1550–1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charalambous M, & Hernandez A (2013). Genomic imprinting of the type 3 thyroid hormone deiodinase gene: regulation and developmental implications. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1830(7), 3946–3955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng SY, Leonard JL, & Davis PJ (2010). Molecular aspects of thyroid hormone actions. Endocr Rev, 31(2), 139–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contempré B, Jauniaux E, Calvo R, Jurkovic D, Campbell S, & Morreale de Escobar G (1993). Detection of thyroid hormones in human embryonic cavities during the first trimester of pregnancy. J. Clin. Endo. Metabol, 77, 1719–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews D, Gillette R, Miller-Crews I, Gore AC, & Skinner MK (2014). Nature, nurture and epigenetics. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 398(1–2), 42–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis PJ, Leonard JL, Lin HY, Leinung M, & Mousa SA (2018). Molecular Basis of Nongenomic Actions of Thyroid Hormone. Vitam Horm, 106, 67–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dentice M, Ambrosio R, Damiano V, Sibilio A, Luongo C, Guardiola O, et al. (2014). Intracellular inactivation of thyroid hormone is a survival mechanism for muscle stem cell proliferation and lineage progression. Cell Metab, 20(6), 1038–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dentice M, Marsili A, Zavacki A, Larsen PR, & Salvatore D (2013). The deiodinases and the control of intracellular thyroid hormone signaling during cellular differentiation. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1830(7), 3937–3945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desjardin C, Charles C, Benoist-Lasselin C, Riviere J, Gilles M, Chassande O, et al. (2014). Chondrocytes play a major role in the stimulation of bone growth by thyroid hormone. Endocrinology, 155(8), 3123–3135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson DA, Paulus JK, Mensah V, Lem J, Saavedra-Rodriguez L, Gentry A, et al. (2018). Reduced levels of miRNAs 449 and 34 in sperm of mice and men exposed to early life stress. Transl Psychiatry, 8(1), 101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escher J, Yan W, Rissman EF, Wang HV, Hernandez A, & Corces VG (2021). Beyond Genes: Germline Disruption in the Etiology of Autism Spectrum Disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X, Jiang Y, Meltzer P, & Yen PM (2000). Thyroid hormone regulation of hepatic genes in vivo detected by complementary DNA microarray. Molecular Endocrinology, 14(7), 947–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes GW, Bocco B, Fonseca TL, McAninch EA, Jo S, Lartey LJ, et al. (2018). The Foxo1-Inducible Transcriptional Repressor Zfp125 Causes Hepatic Steatosis and Hypercholesterolemia. Cell Rep, 22(2), 523–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flamant F, Cheng SY, Hollenberg AN, Moeller LC, Samarut J, Wondisford FE, et al. (2017). Thyroid hormone signaling pathways. Time for a more precise nomenclature. Endocrinology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flamant F, & Gauthier K (2013). Thyroid hormone receptors: the challenge of elucidating isotype-specific functions and cell-specific response. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1830(7), 3900–3907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fondell JD (2013). The Mediator complex in thyroid hormone receptor action. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1830(7), 3867–3875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca TL, Fernandes GW, Bocco B, Keshavarzian A, Jakate S, Donohue TM Jr., et al. (2019). Hepatic Inactivation of the Type 2 Deiodinase Confers Resistance to Alcoholic Liver Steatosis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 43(7), 1376–1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca TL, Fernandes GW, McAninch EA, Bocco BM, Abdalla SM, Ribeiro MO, et al. (2015). Perinatal deiodinase 2 expression in hepatocytes defines epigenetic susceptibility to liver steatosis and obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 112(45), 14018–14023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca TL, Garcia T, Fernandes GW, Nair TM, & Bianco AC (2021). Neonatal thyroxine activation modifies epigenetic programming of the liver. Nat Commun, 12(1), 4446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca TL, Russo SC, Luongo C, Salvatore D, & Bianco AC (2022). Inactivation of Type 3 Deiodinase Results in Life-long Changes in the Brown Adipose Tissue Transcriptome in the Male Mouse. Endocrinology, 163(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest D, & Vennstrom B (2000). Functions of thyroid hormone receptors in mice. Thyroid, 10(1), 41–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fumel B, Guerquin MJ, Livera G, Staub C, Magistrini M, Gauthier C, et al. (2012). Thyroid hormone limits postnatal Sertoli cell proliferation in vivo by activation of its alpha1 isoform receptor (TRalpha1) present in these cells and by regulation of Cdk4/JunD/c-myc mRNA levels in mice. Biol Reprod, 87(1), 16, 11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galton VA, Martinez E, Hernandez A, St Germain EA, Bates JM, & St Germain DL (1999). Pregnant rat uterus expresses high levels of the type 3 iodothyronine deiodinase. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 103(7), 979–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galton VA, Martinez ME, Dragon JA, St Germain DL, & Hernandez A (2021). The Intrinsic Activity of Thyroxine Is Critical for Survival and Growth and Regulates Gene Expression in Neonatal Liver. Thyroid, 31(3), 528–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido N, Cruz F, Egea RR, Simon C, Sadler-Riggleman I, Beck D, et al. (2021). Sperm DNA methylation epimutation biomarker for paternal offspring autism susceptibility. Clin Epigenetics, 13(1), 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golozoubova V, Gullberg H, Matthias A, Cannon B, Vennstrom B, & Nedergaard J (2004). Depressed thermogenesis but competent brown adipose tissue recruitment in mice devoid of all hormone-binding thyroid hormone receptors. Molecular Endocrinology, 18(2), 384–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould E, Frankfurt M, Westlind-Danielsson A, & McEwen BS (1990). Developing forebrain astrocytes are sensitive to thyroid hormone. Glia, 3(4), 283–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groeneweg S, van Geest FS, Peeters RP, Heuer H, & Visser WE (2020). Thyroid Hormone Transporters. Endocr Rev, 41(2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan W, Guyot R, Samarut J, Flamant F, Wong J, & Gauthier KC (2017). Methylcytosine dioxygenase TET3 interacts with thyroid hormone nuclear receptors and stabilizes their association to chromatin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 114(31), 8229–8234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heard E, & Martienssen RA (2014). Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance: myths and mechanisms. Cell, 157(1), 95–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez A (2018). Thyroid Hormone Role and Economy in the Developing Testis. Vitam Horm, 106, 473–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez A (2021). Spermatogonial Dio3 as a Potential Germ Line Sensor for Thyroid Hormone-Driven Epigenetic Inheritance. Biol Reprod. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez A, Fiering S, Martinez E, Galton VA, & St Germain D (2002). The gene locus encoding iodothyronine deiodinase type 3 (Dio3) is imprinted in the fetus and expresses antisense transcripts. Endocrinology, 143(11), 4483–4486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez A, Garcia B, & Obregon MJ (2007). Gene expression from the imprinted Dio3 locus is associated with cell proliferation of cultured brown adipocytes. Endocrinology, 148(8), 3968–3976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez A, & Martinez ME (2020). Thyroid hormone action in the developing testis: intergenerational epigenetics. J Endocrinol, 244(3), R33–r46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez A, Martinez ME, Fiering S, Galton VA, & St Germain D (2006). Type 3 deiodinase is critical for the maturation and function of the thyroid axis. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 116(2), 476–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez A, Martinez ME, Liao XH, Van Sande J, Refetoff S, Galton VA, et al. (2007). Type 3 deiodinase deficiency results in functional abnormalities at multiple levels of the thyroid axis. Endocrinology, 148(12), 5680–5687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez A, Martinez ME, Ng L, & Forrest D (2021). Thyroid Hormone Deiodinases: Dynamic Switches in Developmental Transitions. Endocrinology, 162(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez A, Morte B, Belinchon MM, Ceballos A, & Bernal J (2012). Critical role of types 2 and 3 deiodinases in the negative regulation of gene expression by T(3)in the mouse cerebral cortex. Endocrinology, 153(6), 2919–2928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez A, & Stohn JP (2018). The Type 3 Deiodinase: Epigenetic Control of Brain Thyroid Hormone Action and Neurological Function. Int J Mol Sci, 19(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hönes GS, Rakov H, Logan J, Liao XH, Werbenko E, Pollard AS, et al. (2017). Noncanonical thyroid hormone signaling mediates cardiometabolic effects in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 114(52), E11323–e11332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SA, Dorfman DM, Genest DR, Salvatore D, & Larsen PR (2003). Type 3 iodothyronine deiodinase is highly expressed in the human uteroplacental unit and in fetal epithelium. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism., 88(3), 1384–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T, Chopra IJ, Boado R, Solomon DH, & Chua Teco GN (1988). Thyroxine inner ring monodeiodinating activity in fetal tissues of the rat. Pediatr. Res, 23, 196–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jirtle RL, Sander M, & Barrett JC (2000). Genomic imprinting and environmental disease susceptibility. Environmental Health Perspectives, 108(3), 271–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jirtle RL, & Skinner MK (2007). Environmental epigenomics and disease susceptibility. Nature Reviews Genetics, 8(4), 253–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson C, Gothe S, Forrest D, Vennstrom B, & Thoren P (1999). Cardiovascular phenotype and temperature control in mice lacking thyroid hormone receptor-beta or both alpha1 and beta. Am J Physiol, 276(6), H2006–2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan K, Mittal N, Thompson LM, Rodriguez-Santiago M, Duvauchelle CL, Crews D, et al. (2018). Effects of the Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals, Vinclozolin and Polychlorinated Biphenyls, on Physiological and Sociosexual Phenotypes in F2 Generation Sprague-Dawley Rats. Environ Health Perspect, 126(9), 97005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyono Y, Sachs LM, Bilesimo P, Wen L, & Denver RJ (2016). Developmental and Thyroid Hormone Regulation of the DNA Methyltransferase 3a Gene in Xenopus Tadpoles. Endocrinology, 157(12), 4961–4972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyono Y, Subramani A, Ramadoss P, Hollenberg AN, Bonett RM, & Denver RJ (2016). Liganded Thyroid Hormone Receptors Transactivate the DNA Methyltransferase 3a Gene in Mouse Neuronal Cells. Endocrinology, 157(9), 3647–3657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latteyer S, Christoph S, Theurer S, Hones GS, Schmid KW, Fuhrer D, et al. (2019). Thyroxine promotes lung cancer growth in an orthotopic mouse model. Endocr Relat Cancer, 26(6), 565–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legrand J (1984). Effects of thyroid hormones on central nervous system development. In Yanai J (Ed.), Neurobehavioral Teratology (pp. 331–363). New York: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Legrand J (1986). Thyroid hormone effects on growth and development. In Hennemann G (Ed.), Thyroid Hormone Metabolism (pp. 503–534). New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Leung AM, Korevaar TI, Peeters RP, Zoeller RT, Kohrle J, Duntas LH, et al. (2016). Exposure to Thyroid-Disrupting Chemicals: A Transatlantic Call for Action. Thyroid, 26(4), 479–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JZ, Martagón AJ, Cimini SL, Gonzalez DD, Tinkey DW, Biter A, et al. (2015). Pharmacological Activation of Thyroid Hormone Receptors Elicits a Functional Conversion of White to Brown Fat. Cell Rep, 13(8), 1528–1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YY, Ayers S, Milanesi A, Teng X, Rabi S, Akiba Y, et al. (2015). Thyroid hormone receptor sumoylation is required for preadipocyte differentiation and proliferation. J Biol Chem, 290(12), 7402–7415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez M, Varela L, Vazquez MJ, & al., e. (2010). Hypothalamic AMPK and fatty acid metabolism mediate thyroid regulation of energy balance. Nature Medicine, 16(9), 1001–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macchia PE, Takeuchi Y, Kawai T, Cua K, Gauthier K, Chassande O, et al. (2001). Increased sensitivity to thyroid hormone in mice with complete deficiency of thyroid hormone receptor alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 98(1), 349–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez ME, Charalambous M, Saferali A, Fiering S, Naumova AK, St Germain D, et al. (2014). Genomic imprinting variations in the mouse type 3 deiodinase gene between tissues and brain regions. Mol Endocrinol, 28(11), 1875–1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez ME, Cox DF, Youth BP, & Hernandez A (2016). Genomic imprinting of DIO3, a candidate gene for the syndrome associated with human uniparental disomy of chromosome 14. Eur J Hum Genet, 24(11), 1617–1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez ME, Duarte CW, Stohn JP, Karaczyn A, Wu Z, DeMambro VE, et al. (2020). Thyroid hormone influences brain gene expression programs and behaviors in later generations by altering germ line epigenetic information. Mol Psychiatry, 25(5), 939–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez ME, Karaczyn A, Stohn JP, Donnelly WT, Croteau W, Peeters RP, et al. (2016). The Type 3 Deiodinase Is a Critical Determinant of Appropriate Thyroid Hormone Action in the Developing Testis. Endocrinology, 157(3), 1276–1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez ME, Lary CW, Karaczyn AA, Griswold MD, & Hernandez A (2019). Spermatogonial Type 3 Deiodinase Regulates Thyroid Hormone Target Genes in Developing Testicular Somatic Cells. Endocrinology, 160(12), 2929–2945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez ME, Pinz I, Preda M, Norton CR, Gridley T, & Hernandez A (2022). DIO3 protects against thyrotoxicosis-derived cranio-encephalic and cardiac congenital abnormalities. JCI Insight, 7(21). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez ME, Stohn JP, Mutina EM, Whitten RJ, & Hernandez A (2022). Thyroid hormone elicits intergenerational epigenetic effects on adult social behavior and fetal brain expression of autism susceptibility genes. Front Neurosci, 16, 1055116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Doherty AM, & McGettigan PA (2015). Epigenetic processes in the male germline. Reprod Fertil Dev, 27(5), 725–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappa T, Anselmo J, Mamanasiri S, Dumitrescu AM, Weiss RE, & Refetoff S (2017). Prenatal Diagnosis of Resistance to Thyroid Hormone and Its Clinical Implications. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 102(10), 3775–3782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual A, & Aranda A (2013). Thyroid hormone receptors, cell growth and differentiation. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1830(7), 3908–3916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul KB, Hedge JM, Bansal R, Zoeller RT, Peter R, DeVito MJ, et al. (2012). Developmental triclosan exposure decreases maternal, fetal, and early neonatal thyroxine: a dynamic and kinetic evaluation of a putative mode-of-action. Toxicology, 300(1–2), 31–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedaran M, Oelkrug R, Sun Q, Resch J, Schomburg L, & Mittag J (2021). Maternal Thyroid Hormone Programs Cardiovascular Functions in the Offspring. Thyroid, 31(9), 1424–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrotta C, Buldorini M, Assi E, Cazzato D, De Palma C, Clementi E, et al. (2014). The thyroid hormone triiodothyronine controls macrophage maturation and functions: protective role during inflammation. Am J Pathol, 184(1), 230–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokopuk L, Western PS, & Stringer JM (2015). Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance: adaptation through the germline epigenome? Epigenomics, 7(5), 829–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj S, Kyono Y, Sifuentes CJ, Arellanes-Licea EDC, Subramani A, & Denver RJ (2020). Thyroid Hormone Induces DNA Demethylation in Xenopus Tadpole Brain. Endocrinology, 161(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadoss P, Abraham BJ, Tsai L, Zhou Y, Costa-e-Sousa RH, Ye F, et al. (2014). Novel mechanism of positive versus negative regulation by thyroid hormone receptor beta1 (TRbeta1) identified by genome-wide profiling of binding sites in mouse liver. J Biol Chem, 289(3), 1313–1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rando OJ (2016). Intergenerational Transfer of Epigenetic Information in Sperm. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, 6(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reik W, & Walter J (2001). Genomic imprinting: parental influence on the genome. Nature Reviews Genetics, 2(1), 21–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers AB, Morgan CP, Leu NA, & Bale TL (2015). Transgenerational epigenetic programming via sperm microRNA recapitulates effects of paternal stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 112(44), 13699–13704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roti E, Fang S, Braverman LE, & Emerson CH (1982). Rat placenta is an active site of inner ring deiodination of thyroxine and 3,3’,5-triiodothyronine. Endocrinology, 110, 34–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseaux S, Seyve E, Chuffart F, Bourova-Flin E, Benmerad M, Charles MA, et al. (2020). Immediate and durable effects of maternal tobacco consumption alter placental DNA methylation in enhancer and imprinted gene-containing regions. BMC Med, 18(1), 306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio A, Raasmaja A, Maia AL, Kim KR, & Silva JE (1995). Effects of thyroid hormone on norepinephrine signaling in brown adipose tissue. I. Beta 1- and beta 2-adrenergic receptors and cyclic adenosine 3’,5’-monophosphate generation. Endocrinology, 136(8), 3267–3276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo SC, Salas-Lucia F, & Bianco AC (2021). Deiodinases and the Metabolic Code for Thyroid Hormone Action. Endocrinology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvatore D, Simonides WS, Dentice M, Zavacki AM, & Larsen PR (2014). Thyroid hormones and skeletal muscle--new insights and potential implications. Nat Rev Endocrinol, 10(4), 206–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SanMiguel JM, & Bartolomei MS (2018). DNA methylation dynamics of genomic imprinting in mouse development. Biol Reprod, 99(1), 252–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer U, & Kohrle J (2013). Function of thyroid hormone transporters in the central nervous system. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1830(7), 3965–3973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma U, Conine CC, Shea JM, Boskovic A, Derr AG, Bing XY, et al. (2016). Biogenesis and function of tRNA fragments during sperm maturation and fertilization in mammals. Science, 351(6271), 391–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short AK, Fennell KA, Perreau VM, Fox A, O’Bryan MK, Kim JH, et al. (2016). Elevated paternal glucocorticoid exposure alters the small noncoding RNA profile in sperm and modifies anxiety and depressive phenotypes in the offspring. Transl Psychiatry, 6(6), e837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shultz RB, Wang Z, Nong J, Zhang Z, & Zhong Y (2017). Local delivery of thyroid hormone enhances oligodendrogenesis and myelination after spinal cord injury. J Neural Eng, 14(3), 036014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh BK, Sinha RA, Ohba K, & Yen PM (2017). Role of thyroid hormone in hepatic gene regulation, chromatin remodeling, and autophagy. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 458, 160–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha RA, & Yen PM (2016). Thyroid hormone-mediated autophagy and mitochondrial turnover in NAFLD. Cell Biosci, 6, 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sittig LJ, & Redei EE (2014). Fine-tuning notes in the behavioral symphony: parent-of-origin allelic gene expression in the brain. Adv Genet, 86, 93–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner MK (2014). Endocrine disruptor induction of epigenetic transgenerational inheritance of disease. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 398(1–2), 4–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somer RA, & Thummel CS (2014). Epigenetic inheritance of metabolic state. Curr Opin Genet Dev, 27, 43–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srichomkwun P, Anselmo J, Liao XH, Hönes GS, Moeller LC, Alonso-Sampedro M, et al. (2017). Fetal Exposure to High Maternal Thyroid Hormone Levels Causes Central Resistance to Thyroid Hormone in Adult Humans and Mice. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 102(9), 3234–3240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Germain D, Galton VA, & Hernandez A (2009). Defining the roles of iodohyronine deiodinases: Current concepts and challenges. Endocrinology, 150(3), 1097–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend KL, Madden CJ, Blaszkiewicz M, McDougall L, Tupone D, Lynes MD, et al. (2017). Reestablishment of Energy Balance in a Male Mouse Model With POMC Neuron Deletion of BMPR1A. Endocrinology, 158(12), 4233–4245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trerotola M, Relli V, Simeone P, & Alberti S (2015). Epigenetic inheritance and the missing heritability. Hum Genomics, 9, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu HM, Legradi G, Bartha T, Salvatore D, Lechan RM, & Larsen PR (1999). Regional expression of the type 3 iodothyronine deiodinase messenger ribonucleic acid in the rat central nervous system and its regulation by thyroid hormone. Endocrinology, 140(2), 784–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verga Falzacappa C, Mangialardo C, Patriarca V, Bucci B, Amendola D, Raffa S, et al. (2009). Thyroid hormones induce cell proliferation and survival in ovarian granulosa cells COV434. J Cell Physiol, 221(1), 242–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddington CH (1957). The strategy of genes. Allen & Unwin, London. [Google Scholar]

- Waddington CH (1959). Canalization of development and genetic assimilation of acquired characters. Nature, 183(4676), 1654–1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadzinski TL, Geromini K, McKinley Brewer J, Bansal R, Abdelouahab N, Langlois MF, et al. (2014). Endocrine disruption in human placenta: expression of the dioxin-inducible enzyme, CYP1A1, is correlated with that of thyroid hormone-regulated genes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 99(12), E2735–2743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen L, He C, Sifuentes CJ, & Denver RJ (2019). Thyroid Hormone Receptor Alpha Is Required for Thyroid Hormone-Dependent Neural Cell Proliferation During Tadpole Metamorphosis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 10, 396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams GR, & Bassett JHD (2018). Thyroid diseases and bone health. J Endocrinol Invest, 41(1), 99–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirth EK, Schweizer U, & Kohrle J (2014). Transport of thyroid hormone in brain. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 5, 98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Martinez ME, DeMambro VE, Francois M, & Hernandez A (2022). Developmental Thyroid Hormone Action on Pro-Opiomelanocortin-Expressing Cells Programs Hypothalamic BMPR1A Depletion and Brown Fat Activation. J. Mol Cell Biology, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Martinez ME, St Germain DL, & Hernandez A (2017). Type 3 Deiodinase Role on Central Thyroid Hormone Action Affects the Leptin-Melanocortin System and Circadian Activity. Endocrinology, 158(2), 419–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zekri Y, Guyot R, & Flamant F (2022). An Atlas of Thyroid Hormone Receptors’ Target Genes in Mouse Tissues. Int J Mol Sci, 23(19). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]