Abstract

The allergen-IgE interaction is essential for the genesis of allergic responses, yet investigation of the molecular basis of these interactions is in its infancy. Precision engineering has unveiled the molecular features of allergen-antibody interactions at the atomic level. High resolution technologies, including X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, and cryo-electron microscopy determine allergen-antibody structures. X-ray crystallography of an allergen-antibody complex localizes in detail amino acid residues and interactions that define the epitope-paratope interface. Multiple structures involving murine IgG monoclonal antibodies have recently been resolved. The number of amino acids forming the epitope broadly correlates with the epitope area. The production of human IgE monoclonal antibodies from B cells of allergic subjects is an exciting recent development which has for the first time enabled an actual IgE epitope to be defined. The biologic activity of defined IgE epitopes can be validated in vivo in animal models or measuring mediator release from engineered basophilic cell lines. Finally, gene editing approaches using CRISPR to either remove allergen genes or make targeted epitope engineering at the source are on the horizon. This review presents an overview of the identification and validation of allergenic epitopes by precision engineering.

Keywords: allergens, IgE monoclonal antibody, allergenic epitopes, allergen engineering, X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance, CRISPR

Introduction

Allergens constitute one of the most well-defined groups of biomedically important proteins, yet analysis of IgE epitopes on allergens is in its infancy (Table I).1–4 The very low levels of allergen specific IgE antibodies in sera, even from highly allergic patients, together with the polyclonality of IgE responses, have been persistent barriers to epitope analysis. Until recently, investigators were limited to indirect methods for identifying conformational epitopes. These epitopes involve residues that are close in space due to protein folding but are non-contiguous in the primary amino acid sequence. Evidence of the validity of conformational epitopes was largely circumstantial.

Table I.

Allergenic Epitopes: What is Unknown

| • Except for Bet v 1 and Phl p 2, very little is known about the nature of allergenic epitopes on tree, grass and weed pollen allergens. |

| • The structure of natural heterodimeric cat allergen Fel d 1 and the location of epitopes on this important allergen. |

| • Precise mapping and structural analysis of IgE epitopes on allergens for which multiple non-overlapping human IgE mAb are available (e.g. Der p 2, Ara h 1, Ara h 2, Ara h 3, Ara h 6). |

| • The repertoire and epitope diversity of natural human IgE responses and whether there are immunodominant IgE binding sites. |

| • For food allergens, validation of the relative importance and biologic activity of linear epitopes; and structural analysis of putative conformational epitopes. |

| • The structure of epitopes on mold allergens, venoms, fish, shellfish tropomyosin allergens, tree nuts, and important mammalian allergens, such as the lipocalins. |

| • Whether IgE (or IgG) antibodies to specific epitopes are biomarkers of either disease severity or therapeutic importance. |

The term “engineering” in the context of allergens was introduced in a 1997 paper by Takai et al. who used site directed mutagenesis to disrupt intramolecular disulfide bonds on Der f 2. The engineered mutant Der f 2 showed a reduced skin test reactivity and basophil histamine release in mite allergic patients yet retained T cell stimulatory epitopes.5 Similar data were reported for Der p 2 with cysteine variants showing ~100-fold reduction in IgE antibody binding.6 The rationale was that allergen molecules engineered to reduce IgE reactivity with point mutations or deletions, or as multimeric proteins, would be safer for allergen immunotherapy. The approach was widely adopted to develop hypoallergens from many other allergens including Bet v 1, Phl p 5, Fel d 1 and Art v 1.7–9 While many genetically engineered allergen variants have been constructed, they are of limited value for identifying IgE epitopes. In most cases, especially when loss of IgE binding to unfolded allergens is observed, these studies provide evidence that IgE antibodies to inhaled allergens are directed against conformational epitopes, rather than sequential or linear epitopes, made of consecutive amino acid residues.10 Recent determination of the molecular structures of allergen-mAb complexes by X-ray crystallography and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy has identified the contact amino acid residues that form conformational epitopes on several allergens (Table II).11

Table II.

Structures of allergen-antibody complexes

| Allergen in complex with murine IgG antibody | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Allergen/Source | Antibody | PDB codea | # residues in epitope/# H bondsb |

| Api m 2/Honeybee | Fab; mIgG1 mAb 21E11 | 2J88c79 | 12/13 |

| Bet v 1/Birch | Fab’; mIgG1 mAb BV16 | 1FSKc26 | 20/10 |

| Bet v 1/Birch | Fab; mIgG4 mAb REGN5713e | 7N0U20 | 20/6 |

| Bet v 1/Birch | Fab; mIgG4 mAb REGN5715e | 7N0V20 | 13/11 |

| Bet v 1/Birch | Fab; mIgG4 mAb REGN5713 e Fab; mIgG4 mAb REGN5714 e Fab; mIgG4 mAb REGN5715 e |

7MXL20 (cryo-EM) | 21/4 28/16 17/9 |

| Bla g 2/German cockroach | Fab’, mIgG1 mAb 7C11 | 2NR6c117 | 23/17 |

| Bla g 2/German cockroach | Fab, mIgG1 mAb 4C3 | 3LIZc118 | 23/11 |

| Der f 1/House dust mite | Fab; mIgG1 mAb 4C1 | 5VPL109 (3RVV)cd |

18/7 |

| Der p 1/House dust mite | Fab; mIgG1 mAb 4C1 | 1) 5VPG109(3R VW)cd 2) 5VPH109(3R VX)cd |

1) 16/11 2) 20/12 |

| Der p 1/House dust mite | Fab; mIgG1 mAb 5H8 | 5VCN119 (4PP1)cd | 21/14 |

| Der p 1/House dust mite | Fab; mIgG1 mAb 10B9 | 5VCO119 (4PP2)cd | 20/11 |

| Der p 2/House dust mite | Fab; mIgG1 mAb 7A1 | 6OY4c30 | 17/7 |

| Fel d 1/Cat | Fab; mIgG4 mAb REGN1909e | 5VYF116 | 17/9 |

| Gal d 4g/Chicken | 1) 3HFM120 1FDL121 1MLC122 1YQV123 |

1) 22/13 2) 10/13 3) 16/10 4) 19/13 |

|

| Allergen in complex with human IgG antibody | |||

| Allergen/Source | Antibody | PDB code | # residues in epitope/# H bonds b |

| Ara h 2/Peanut | rFab; 22S1 mAbf rFab;13T1 mAbf |

8DB421 | 14/14 22/14 |

| Gal d 4g/Chicken | Human Vh domain (VH H04)h | 1) 4PGJ124 2) 4U3X124 |

1) 21/11 2) 22/19 |

| Phl p 7/Timothy grass | Fab; hIgG1 mAb 102.1F10i | 5OTJ125 | 17/9 |

| Allergen in complex with IgG antibody containing human IgE variable regions from phage display combinatorial libraries | |||

| Allergen/Source | Antibody | PDB code | # residues in epitope/# H bonds b |

| Bos d 5/Cow | Fab; hIgG1 mAb D1j | 2R56126 | 25/11 |

| Phl p 2/Timothy grass | Fab; hIgG1 mAb huMab2j | 2VXQc127 | 21/15 |

| Allergen in complex with murine IgE antibody | |||

| Allergen/Source | Antibody | PDB code | # residues in epitope/# H bonds b |

| Hev b 8/Latex | rFab; mIgE mAb 2F5 | 1) 7SBD78 2) 7SBG78 |

23/11 21/10 |

| Allergen in complex with human IgE antibody | |||

| Allergen/Source | Antibody | PDB code | # residues in epitope/# H bonds b |

| Der p 2/House dust mite | rFab; hIgE mAb 2F10k | 7MLH22 | 15/10 |

References for all the structures in the table are indicated as a superscript to the PDB code and most were reviewed at11. In 7MXL, three anti-Bet v 1 IgG4 antibodies were co-crystallized with the allergen in a quaternary complex.

PDBePISA was used to calculate the number of residues and H-bonds.128 Residues contributing at least 2.0 Å2 to the epitope area were included, and 3.30 Å distance cutoff was used for identification of H-bonds.

Articles that report inhibition of IgE antibody binding by the antibody used in the X-ray crystal structure (or vice versa).

Original published PDB code in parenthesis was replaced by the definitive one shown.

Fully human Bet v 1 and Fel d 1 specific IgG4 mAb were generated using the VeloImmune human antibody mouse platform.20 Human antibodies were made by a mouse immune system and do not necessarily target the same distribution of epitopes that may be seen in humans.

Recombinant IgG1 antibodies were obtained from paired H and L chains that were amplified, sequenced and cloned from single cell sorted Ara h 2 specific B cells from allergic subjects. The two mAb were co-crystallized with the allergen in a 22S1Fab-13T1Fab-Ara h 2 ternary complex.

Only selected complexes with lysozyme are listed. For example, complexes of human VH domains with lysozyme were chosen to compare them with complexes formed by Fabs.

VH H04: Phage displayed

hIgG1 mAb 102.1F10 was expressed based on a hIgG4 that was generated from matched heavy and light chain sequences by single B cell cloning from allergic individuals.

CK and CH1 of IgG1 cloned with IgE VH/VL isolated from human IgE derived from a combinatorial library.

hIgE mAb 2F10 obtained by hybridoma technology using B cells from allergic subject.

For food allergens, it has long been considered that IgE antibody responses are directed against linear epitopes on ‘small’ peptides that are derived from digestion of food proteins in the gut. These peptides were successfully identified by screening overlapping peptides derived from allergen sequences for IgE reactivity, when bound to cellulose membranes or other solid phases.12, 13 Some of these IgE-binding peptides have disease associations. For example, persistent egg allergy is associated with IgE reactivity to four peptides on Gal d 1.14 Selected peptides from food allergens are now being used to develop multiplex diagnostic tests for food allergy.12, 15, 16 An important limitation of food epitope analyses is that they are based almost exclusively on testing IgE binding to peptides bound to solid phase. Few studies have investigated the capacity of peptides either alone or in combination to inhibit IgE responses to native allergen.17 The relative importance of anti-peptide IgE to the repertoire of IgE responses to native food allergens is not known and there is growing evidence that some food allergen epitopes are conformational.17–19

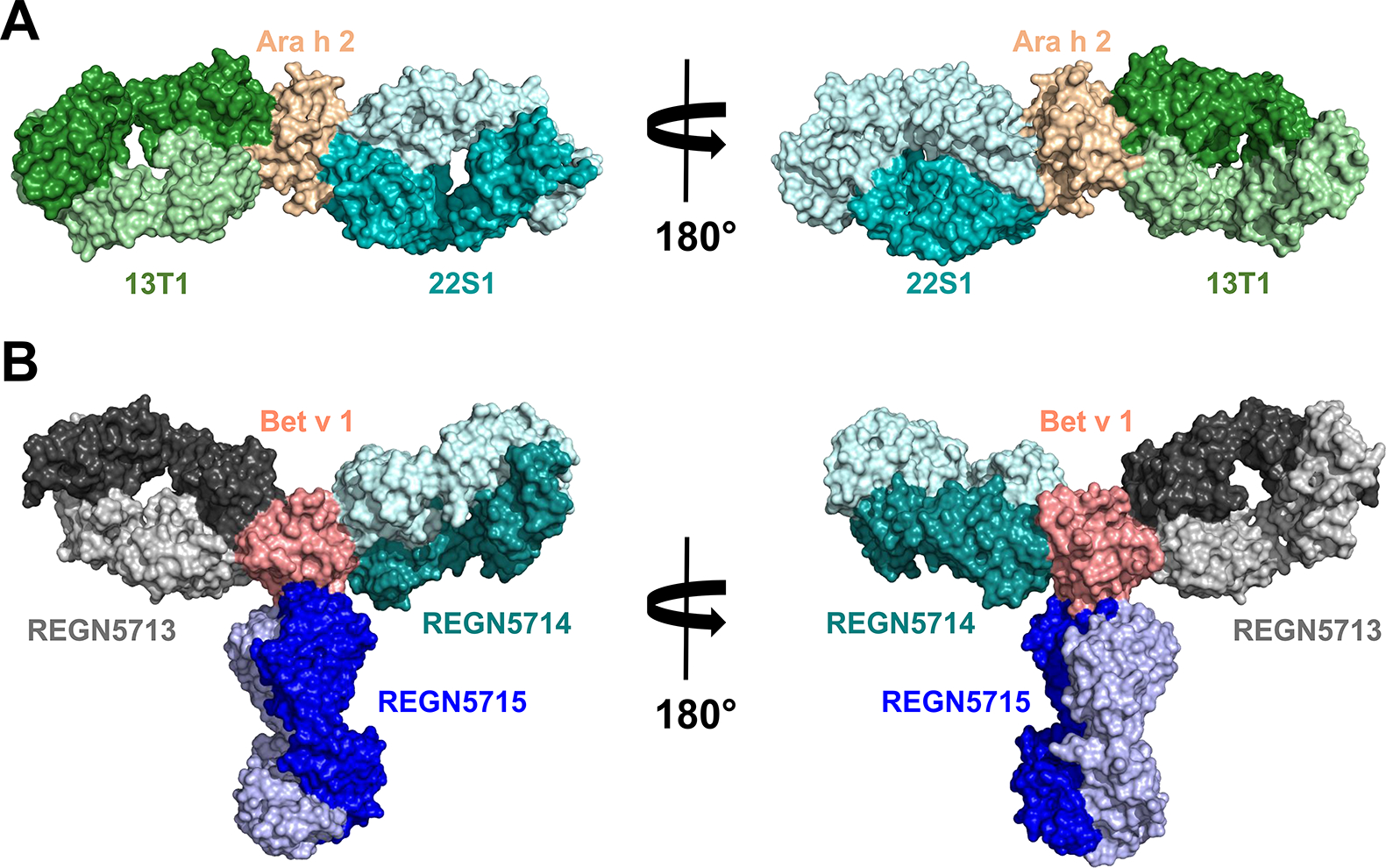

For inhaled allergens, food allergens and other allergens, there are many unknowns concerning the localization, structure and repertoire of IgE B cell epitopes (Table I). With a few exceptions (noted in Table I) there is a paucity of data on allergen epitopes from trees, grass and weed pollens, molds, venoms, fish and shellfish. For allergens for which multiple epitopes are known to occur (e.g. Bla g 2, Der p 1, Der p 2, Ara h 2, Fel d 1), the structural information at present is limited in most cases to one to three epitopes (for IgG antibodies). Typically, small globular proteins (MW 10–20 kDa) contain 3–5 non-overlapping epitopes, each of which covers an area of 700–900 Å2. The estimation of the number of non-overlapping epitopes for small allergens is facilitated by several reported structures of an allergen in complex with an antibody (e.g. Bla g 2, Der p 111), and structures of an allergen in complex with two or three different antibodies simultaneously (Figure 1).20, 21 This appears to be the case for epitopes on allergens that have been defined, but detailed mapping of allergenic surfaces is lacking.

Figure 1.

A. Crystal structure (PDB: 8DB4) of Ara h 2 in complex with two Fab fragments of antibodies 13T1 and 22S1. B. Cryo-EM structure (PDB: 7MXL) of Bet v 1 in complex with three different Fab fragments of antibodies REGN5713, REGN5714 and REGN5715. Molecules are shown in space filling representation. Heavy chains are marked using darker colors. The figure shows that there is a limited number of antibodies that can simultaneously bind to an allergen due to steric restrictions.

The known unknowns make the investigation of the molecular basis of IgE epitopes a ripe field for future study (Table I). A sophisticated array of molecular tools can be used for manipulating allergen sequences. Most importantly, human IgE antibody sequences are rapidly becoming available through the development of phage display technology to construct combinatorial IgE libraries, and panels of natural human IgE monoclonal antibodies (hIgE mAb) from allergic patients. The first structure of a human IgE antibody-allergen complex has recently been published.22 Promising steps towards gene editing of allergen sequences using CRISPR technology have been reported.23 This review focuses on current strategies for effectively identifying allergenic epitopes; for localization and definition of contact residues; and for validation of the biologic importance of IgE epitope(s) by genetic engineering and gene editing techniques.

Strategies for the identification of allergenic epitopes

Conformational epitopes

Conformational epitope mapping strategies consider the three-dimensional structure of the molecules involved in the allergen-IgE antibody interaction. Indirect ways to define conformational epitopes have mostly been used (including the analysis of chimeras, the identification of mimotopes, etc.), and the limitations of these indirect methods have been recently reviewed.11, 24 In contrast, direct methods such as X-ray crystallographic analyses of allergen-antibody complexes, which provide comprehensive data of the interactions involved in antibody recognition (Table II), will be addressed here. Although structures of an antigen (egg lysozyme, Gal d 4) in complex with murine IgG mAb fragments were first reported in 1985 25, the first structure of an allergen-antibody complex using murine IgG mAb known to interfere with IgE antibody binding was determined with the birch allergen Bet v 1.11, 26 The allergen-antibody structures determined to date revealed the number of residues on the allergen (up to ~25) that participate in epitope-paratope recognition, and the nature of the interactions involved (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic, etc.) (Table II). Selective mutations of a few residues in the epitope diminished murine mAb binding. Testing of mutants for their capacity to bind IgE also led to identification of potential IgE antibody binding sites.27–30 Therefore, these studies also revealed that only a few amino acid residues were essential for mAb binding. As proof of principle, an epitope was created de novo on the mite allergen Der f 1 to confer specificity for the mAb 10B9 that is Der p 1-specific and does not bind Der f 1.28 Seven rDer f 1 mutants were expressed, each containing 1–4 amino acid substitutions within the corresponding area of the mAb 10B9 epitope in Der p 1. As more substitutions were made in the Der f 1 mutants, more mAb 10B9 binding was observed in dose-response curves, with increased saturation levels of Ab binding, and increased affinities of the mutants for binding mAb 10B9. The mutation of three or four residues created an epitope with an affinity within the same order of magnitude as the full epitope in Der p 1. The newly engineered epitope also conferred to Der f 1 a higher capacity to bind IgE antibodies. Interestingly, the creation of a new mAb 10B9 binding site on Der f 1 showed that additional hydrogen bonds involving CDR other than the heavy chain CDR3, were required for mAb 10B9 binding.28 This study is an example of precision engineering to generate an epitope with only few residues, and indicates that the CDR3 from the heavy chain, which is considered to be mostly responsible for antibody specificity, is not required for recognition by all mAb.28, 31

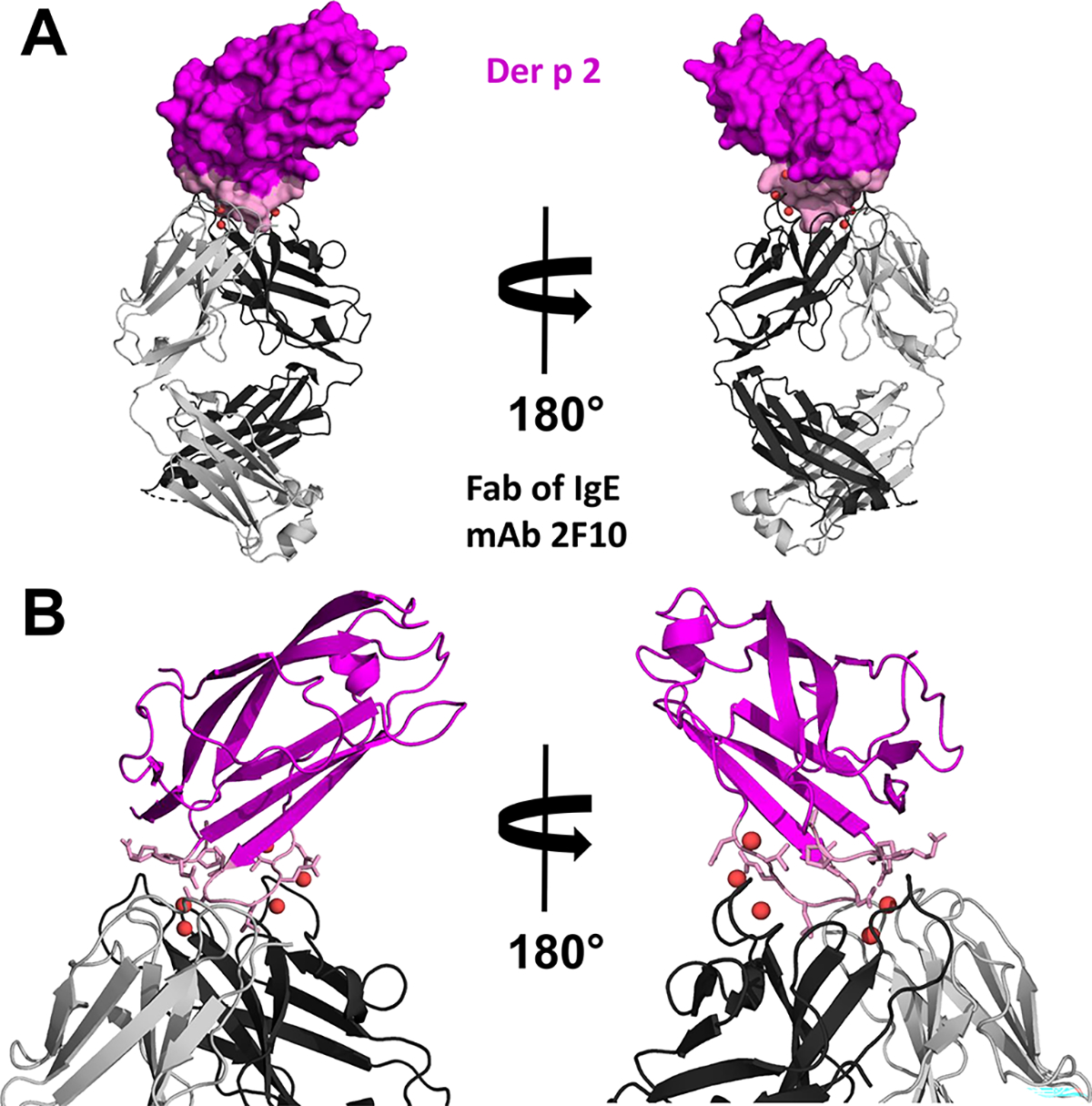

These crystallographic studies required pure and homogeneous protein preparations of the complex and used murine IgG mAb as surrogate antibodies for human IgE. Ideally, human IgE mAb should be used to identify IgE epitopes, but those have not been available until recently thanks to hybridoma technology, which led to the determination of the first structure of an IgE Fab in complex with the mite allergen Der p 2 (Table II, Figure 2).22

Figure 2.

A. Crystal structure (PDB: 7MLH) of Der p 2 in complex with Fab of the IgE mAb 2F10. Der p 2 is shown in space filling representation with 2F10 epitope colored in pink. The Fab is presented using ribbon representation. Water molecules mediating the allergen antibody interactions are shown as red spheres. B. Close view of the allergen-antibody interface. Der p 2 is shown in ribbon representation with residues forming the epitope presented in stick representation and colored pink.

Loss of IgE binding to denatured allergens indicates that conformational IgE epitopes, especially from aeroallergens, are common.10 Food allergens are processed (e.g. by heat denaturation) and cleaved by gastrointestinal digestion, which leads to changes in the native structure of the allergen and, potentially, to the induction of IgE against linear epitopes. The assumption is that digestion of the allergen is extensive, and short peptides mimic the fragments resulting from food processing or cleavage of the allergens through the digestive tract. However, it is difficult to imagine how short peptides could contain two epitopes that cross-link IgE. Complete digestion of allergens during food processing and/or digestion may not occur 32–34, and could result in IgE antibodies directed against fragments of allergens with defined three-dimensional structure, in addition to linear peptides. Strong evidence for the existence of conformational epitopes in food allergens was reported by Albrecht et al. who showed that unfolded Ara h 2 and peptides from Ara h 2 and Pen a 1, representing the identified sequences of linear epitopes, had no capacity to inhibit IgE antibody binding to the native allergen in ELISA or basophil activation tests.17 Unfolded rAra h 2 showed reduced IgE-binding capacity compared with folded rAra h 2 and failed to elicit mediator release.17 Therefore, there was little or no contribution of sequential epitopes to the IgE binding to this allergen in fluid phase antibody/target interactions. Additional evidence of conformational epitopes in food allergens exists.18, 19, 35–38 For milk and egg allergens, for example, the known linear epitopes are not sufficient to explain IgE reactivity to the allergens from both sources. Predominance of IgE against conformational epitopes could explain the observed tolerance to cooked milk and egg.35–38 In contrast, infants reactive to baked milk have a more severe phenotype to cow’s milk allergy, with a higher risk of severe anaphylaxis and a more protracted course of disease.39

Linear epitopes

Most of the epitope mapping studies have been restricted to the identification of linear or sequential epitopes by design. In the 1990s, epitope mapping studies focused on testing the capacity of IgE antibodies to bind overlapping peptides covering the full length of the allergen, or to bind enzyme digests or recombinant allergen fragment bound to a solid phase (e.g. nitrocellulose or Sepharose).40, 41 While these studies identified some IgE antibody binding residues, a possible drawback of synthesized overlapping peptides is that they might lack post-translational modifications that could be essential for IgE antibody binding (although peptides may also be synthesized with such modifications) (e.g. hydroxyprolines in peanut allergens).42 These approaches to map linear epitopes evolved over time into the development of peptide microarrays12, 13, 15 and bead-based assays 16, 43–49, which facilitated measurement of IgE antibody binding to peptides, bound to other solid phases (e.g. glass slides or polystyrene beads). Recently, extensive libraries of peptides have been generated to cover a large set of allergens: a) AllerScan, a programmable phage display library, covering all the protein sequences present in the Allergome database 50, 51, and b) a global microarray platform covering all possible linear overlapping 16-mer epitopes (> 17,000) of 731 allergens listed in the World Health Organization and International Union of Immunological Societies (WHO/IUIS) Allergen Nomenclature database.52 These strategies allow patterns of peptide recognition by different isotype repertoires (IgG, IgG4 and IgE) to be analyzed, as well as the evolution of linear epitope recognition with age and at different times during immunotherapy, and show promise for allergy diagnosis and prediction of food tolerance.15, 16, 43–52 On the other hand, cross-reactivity among food allergen epitopes complicates diagnosis and management of food allergies.53 We suggest that the relative ease and low cost of studying peptide epitopes has led to a systematic bias in the literature favoring linear epitopes over the more difficult to determine conformational epitopes.

Definitive epitope identification using hIgE mAb

Despite the great advancements in understanding epitopes bound by human IgE antibodies, significant gaps in our knowledge remain due in part to the uncertainty of the indirect methodologies outlined above (Table 1). The ‘ideal’ approach is to use naturally occurring allergen-specific human IgE mAb obtained from allergic subjects, which are representative of the IgE antibody repertoire. Recent technological advances have allowed human IgE mAb to be produced using two alternative approaches: single cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) and human hybridoma generation.54, 55

Single B cell RT-PCR was originally used to obtain allergen-specific IgG antibody pairings56, but this is not an efficient approach for IgE due to the low frequency of B cells encoding IgE in peripheral blood.57 Heavy chain variable gene sequences of IgE antibodies were obtained from deep sequencing of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), but did not result in the production of natural pairs of allergen-specific heavy and light chains.58 With great progress in sequencing and the development of single cell technologies, scRNAseq can now capture naturally occurring IgE antibodies from allergic donors. Human IgE mAb against peanut allergens isolated using this approach were cloned from single B cell transcriptomes.54 Convergent evolution was identified in which IgE antibodies underwent identical gene rearrangements in unrelated individuals.54, 59 The scRNAseq approach has several advantages over the labor intensive hybridoma method, the greatest of which is that it can both capture IgE encoding memory B cells and plasmablasts. The disadvantages, including cost and the challenges associated with analyzing large transcriptomic datasets, are diminishing as sequencing technologies become cheaper and analytical tools more readily available.

Human hybridoma technology has been successfully employed to engineer allergen specific human IgE and to identify for the first time actual epitopes recognized by IgE antibodies.22 This approach has previously been used to generate antigen specific IgG, IgA, and IgE antibodies to study human immunity to pathogens.55, 60–64 It is highly versatile, scalable, and capable of identifying ultra-rare populations of circulating antibody encoding memory B cells. The ability to study the precise epitopes bound by the human IgE antibodies has been sought for decades. There are three major reasons why IgE mAb have not been made until now. The first is that techniques for efficiently making full-length human mAb by hybridoma technologies were not in place until a decade ago.60, 61 The second, and most important reason, is that the frequencies of IgE producing B cells in the peripheral blood are exceedingly low. Even in the most allergic individuals, frequencies are often < 5 memory B cells per 10 mL of blood. Because these IgE B cells are so rare, the numbers that can be captured with a single blood draw are often not sufficient for previous recombinant mAb technologies, which include single cell sorting of antibody-secreting plasma cells or Epstein-Barr virus transformation of human B cells.65–67 The third reason is the poor surface expression of membrane IgE (B cell receptor) on circulating IgE encoding plasmablasts (which grow poorly in culture) and memory B cells.54, 68–70 Plasmablasts primarily secrete antibody, making it difficult for flow cytometry-based methods involving labeling of the B cell receptor to identify IgE encoding B cells.68–70 These features compound the difficulty of detecting the ultra-rare populations of IgE producing B cells within PBMC samples. Studies describing the identification of IgE producing B cells may inadvertently use methods that destroy them, including staining intracellular IgE by fixation and permeabilization of cell membranes.71, 72 For this reason, studies of IgE expressing B cells in culture have only involved artificially class-switched polyclonal cultures using the cytokine IL4.73–75 Since IL4 class-switches B cells in a nonpredictive way (regarding origin/destination of isotype), allergen-specific human antibodies are not made.

Allergen-specific human IgE mAb have been generated from highly allergic symptomatic patients with rhinitis, asthma atopic dermatitis and eosinophilic esophagitis.76 These patients have high levels of total and allergen specific serum IgE, and tend to have relative enrichment of allergen specific memory B cells.77 Careful donor selection allows for allergen specific IgE mAb to be generated in an allergen unbiased manner, without the use of allergen at any time in the process. Following PBMC isolation, without cell depletion or selection, all memory B cells are expanded without concern for isotype or specificity, to produce sufficient cells to overcome the inefficiency of the myeloma fusion step. Culture wells containing an IgE isotype expressing B cell are identified using highly sensitive ELISA screening, again without regard for allergen specificity. In a typical highly allergic donor, IgE will be detected in approximately one out of every 100 culture wells (each plate containing ~2 million PBMC). IgE producing cells are fused to a myeloma cell partner using electrical cytofusion to create immortal memory B cell clones. The IgE secreting hybridoma is cloned by limiting dilution and single cell sorting by flow cytometry. Typically, it is only after an IgE mAb is generated that its specificity is determined. The number of IgE mAb obtained from an allergic donor depends on several factors, including the number, severity, and duration of the donor’s allergies, their age, the volume of blood drawn, and the number of PBMC isolated.

The IgE mAb can be manufactured in serum free culture medium and purified using anti-IgE affinity chromatography. IgE antibody variable gene sequences can be amplified by RT-PCR and analyzed using the ImMunoGeneTics (IMGT) database to determine germline gene usages (V/D/J), the CDR sequences, variable gene mutation rates, and the presence of insertions and/or deletions (indels). Finally, recombinant mammalian expression of these variable sequences can be used to produce isotype switched variant IgG mAb, engineered antibody constructs, and Fab for epitope analyses.129

Localization and structure of IgE epitopes

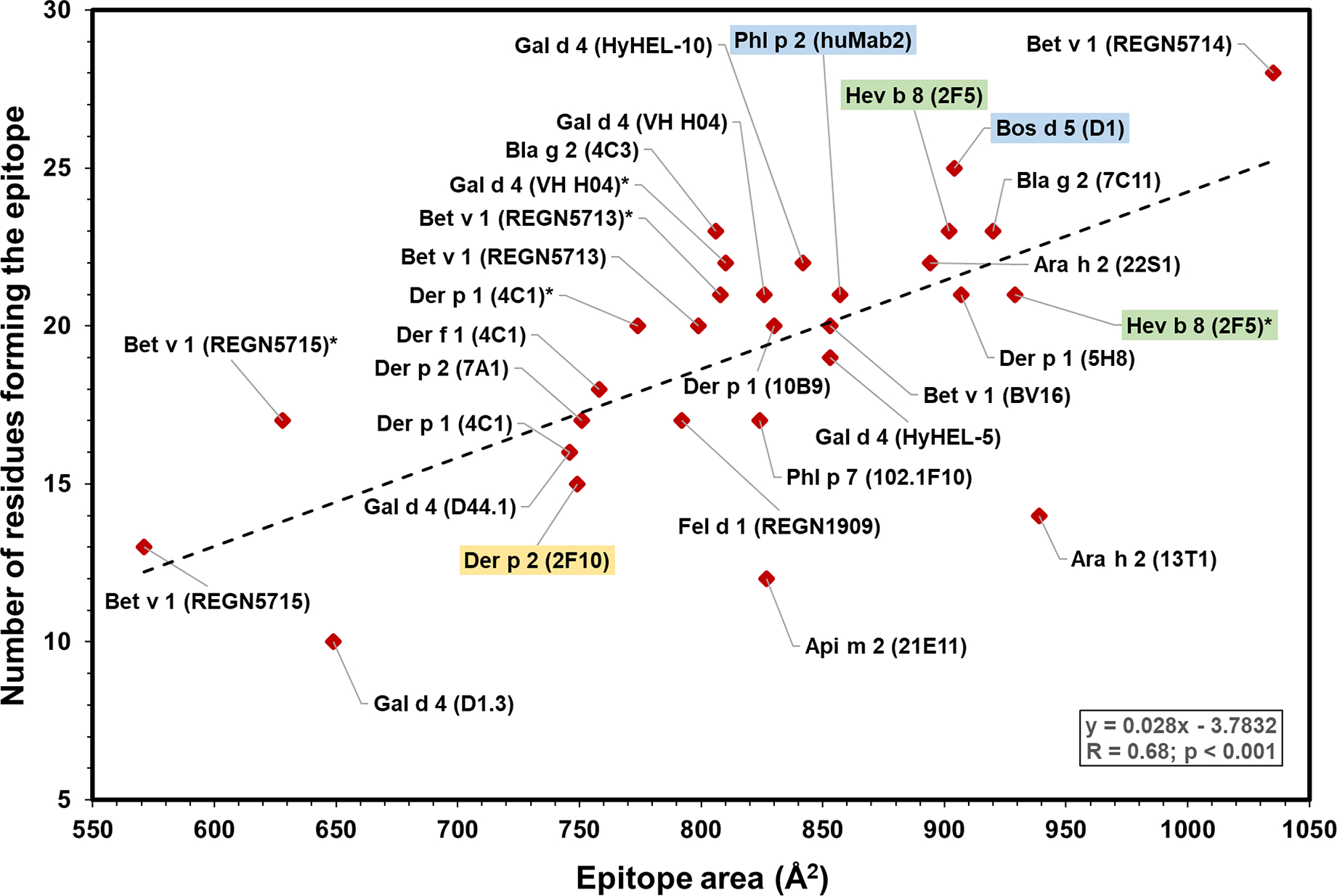

Allergen-antibody interfaces have been analyzed in detail primarily by crystallography as shown in Table II. The analysis of the available epitopes identified on allergens shows that on average they have an area of approximately 800 Å2, which can vary significantly from below 600 Å2 for the smallest epitopes, to close to 1,000 Å2 for the largest ones (Figure 3). Most often the epitopes are formed by approximately 20 residues (Table II), but this number can vary from slightly more than 10 residues to almost 30 residues (Figure 3). Usually, the heavy chain of the antibody is responsible for most interactions with the allergen, contributing on average almost 70% of the paratope-epitope area (Table E1). However, this can vary significantly. In Api m 2 and Hev b 8 complexes, the light chains contribute over 50% of the area.78, 79 It is worth mentioning that in the complex of Bet v 1 with REGN5715, the heavy chain is responsible for over 90% of the area between paratope and epitope (Figure 1, Table E1).20 Generally, the epitopes on the same allergen can differ significantly in their size and number of residues. In some cases, even a relatively small number of residues can form a large epitope.

Figure 3.

Plot showing epitope area versus number of residues in the epitopes from structures in Table II. There is a statistically significant correlation between both variables (r = 0.68, p < 0.001). Stars indicate that there are two different experimental models for a particular allergen-antibody pair (Bet v 1 (REGN5713) and Bet v 1 (REGN5713)* correspond to the PDB structures 7N0U and 7MXL, respectively; Bet v 1 (REGN5715) and Bet v 1 (REGN5715)* correspond to the PDB structures 7N0V and 7MXL, respectively; Der p 1 (4C1) and Der p 1 (4C1)* correspond to the PDB structures 5VPG and 5VPH, respectively; Gal d 4 (VH H04) and Gal d 4 (VH H04)* correspond to the PDB structures 4UX3 and 4PGJ, respectively, and Hev b 8 (2F5) and Hev b 8 (2F5)* correspond to the PDB structures 7SBD and 7SBG, respectively). IgE epitopes are highlighted in color (green: murine IgE mAb; blue: human IgE mAb derived from combinatorial libraries; and yellow: human IgE mAb generated by hybridoma technology).

A detailed description of IgE-allergen interactions allows for a rational design of modified versions of allergens that potentially can be used for immunotherapy. For example, the mutated version of Der p 2, which was designed based on the analysis of a complex formed between the allergen and an hIgE mAb (2F10), prevented anaphylaxis in a mouse model.22 The 2F10 Fab is currently the only example of an hIgE mAb construct to have its structure determined (Figure 2). The heavy and light chains of 2F10 are properly paired, whereas there is no such certainty in the case of other IgE fragments derived from combinatorial libraries, where heavy and light chains are randomly paired. Therefore, the use of hIgE mAb has become not only the best approach to get accurate information on allergy relevant epitopes but it is also the most direct and efficient strategy for engineering allergens for future use in allergy treatment. Human IgE mAb can be used for X-ray crystallography, cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy studies. An additional application is their use in protection assays combined with mass spectrometry (MS). In such cases, the complex can be modified by using the hydrogen-deuterium (1H-2H) exchange (HDX) technique. The hydrogens protected in the antigen-antibody interface have a lower 1H-2H exchange rate. After exposure to 2H, the complex is cleaved, the ratio of 1H:2H in the cleavage products is measured and the binding area is identified using MS. The HDX-MS technique can be successfully used for identification of not only epitopes and paratopes, but also sites that are responsible for other protein-protein interactions.80–82

Other techniques: NMR and Cryo-EM

X-ray crystallography provides the highest resolution chemical detail of allergen-antibody complexes. Both NMR spectroscopy and cryo-EM can also generate atomic level detail of molecular interactions. NMR has been primarily utilized to determine the structures of small individual allergens, as compared to complexes with antibodies.83–85 Larger complexes with antibodies or antibody fragments are more difficult because signal to noise suffers and information content drops as molecular weight increases using NMR. Nevertheless, atomic information about epitopes can be gleaned from a variety of specialized NMR techniques.11 Focusing on Der p 2, epitope regions were proposed by NMR for murine IgG and human IgE antibodies prior to subsequent verification by crystallography.22, 86 In this case, the epitope data provided by NMR relied on the methyl resonances of isoleucine, leucine, and valine residues that were examined before and after forming the complex with IgG or IgE mAb. Using different probes like uniform 15N labeling, more complete models of epitopes can be deduced for smaller complexes, like that of an Fab with Blo t 5 or an scFv with Gad m 1.87, 88 Note that in all these cases the data represents a limited set of atoms for binding information compared to the all-atom models of crystallography or cryo-EM. Hence, defining the epitope is likely to be less precise. Complete atomic models of scFv and Fab complexes with antigens have been determined by NMR,89 however to the best of our knowledge this has not been reported for an allergen.

In contrast to NMR, cryo-EM has difficulty with small molecules, but excels at structures of very large complexes. Indeed, the only reported cryo-EM structure of an allergen complex is Bet v 1 with 3 Fab fragments attached simultaneously, making the complex about 140 kDa (Figure 1).20 Currently, structures of about 100 kDa complexes are feasible,90 which is approximately 2 Fab + 1 allergen. Images of the complexes in vitrified ice are compared and signal averaged to create all-atom models of the complex. In the Bet v 11-Fab3 complex, the epitope regions were clearly delineated. However, compared to the crystallographic structures, the cryo-EM structure provided less precise information of the details of the molecular interactions. For example, in the Bet v 1 structure there are several lysine side chains close to the Fab that could be making important interactions. However, the side chains are modeled in awkward conformations pointing away from possible stronger interactions likely due to the lack of definitive data. This means that if one is trying to engineer hypoallergens, it may require making more mutants to find key residues using cryo-EM or NMR as opposed to crystallography.

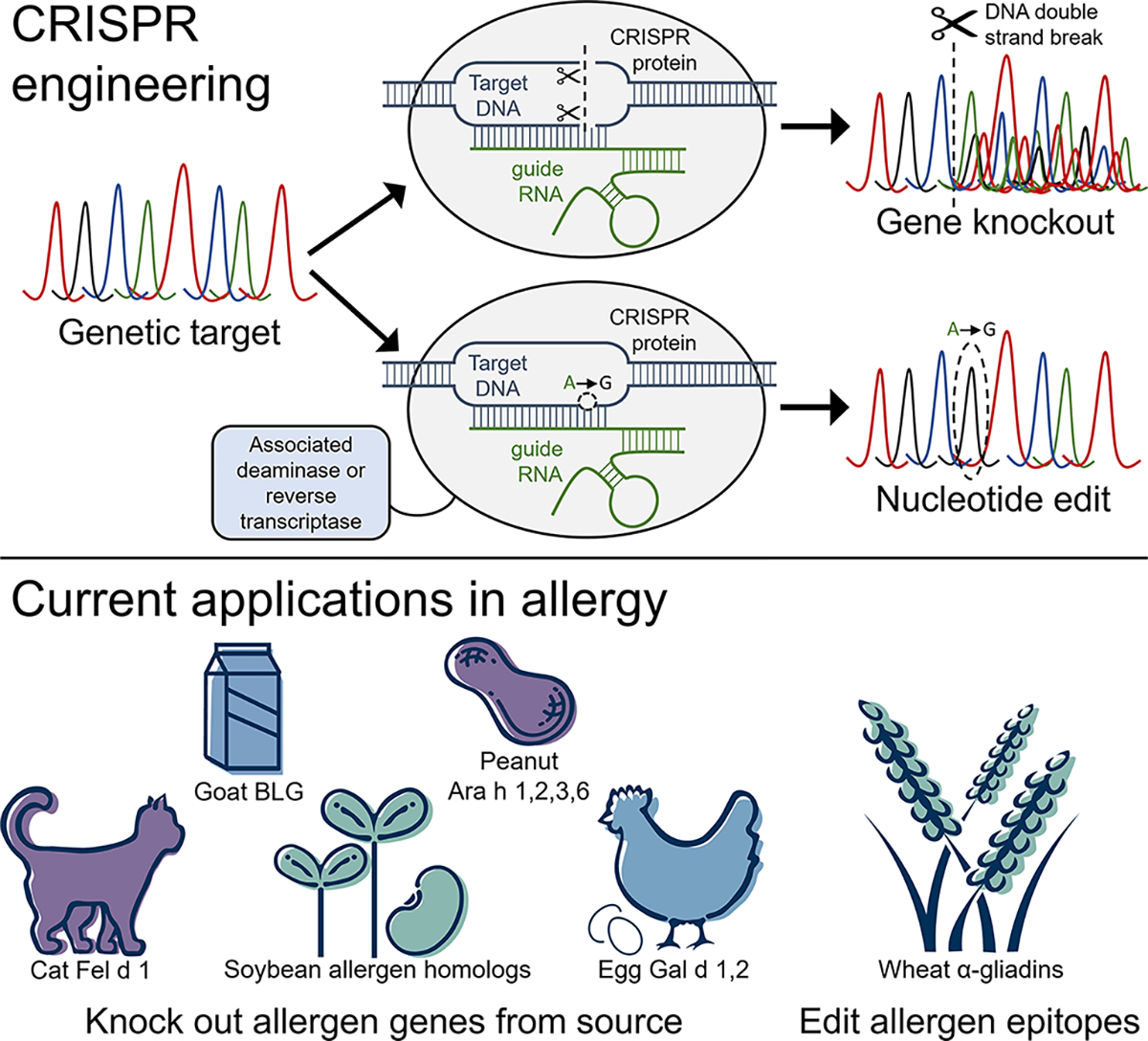

Precision engineering in allergy using CRISPR

Recent innovations in genome engineering, particularly Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats technology (CRISPR), present exciting opportunities in allergy, such as removing allergen genes from the source or editing allergenic epitopes to produce hypoallergens. CRISPR systems employ small, modifiable guide RNAs that direct CRISPR-associated proteins to cleave a DNA target sequence (Figure 4).91, 92 The high specificity of CRISPR systems, which is determined by the short guide RNA sequences, enables editing a genomic target with remarkable precision.93

Figure 4.

CRISPR engineering a genetic target using (top) traditional CRISPR-Cas9, resulting in gene knockout following DNA double strand break; or (bottom) CRISPR base or prime editors, which enable precision editing of a single target DNA nucleotide with the assistance of associated deaminase or reverse transcriptase enzymes. To date, CRISPR engineering has been applied to edit allergen genes in cat, goat’s milk, soybean, peanut, hen’s egg, and wheat. BLG: β-lactoglobulin. (© InBio, 2023)

To date, CRISPR has been applied for the targeted deletion of allergens with the aim of better understanding allergen proteins and providing improved, alternative treatment options for allergic disease.23 Several recent applications have demonstrated the feasibility of knocking out inhaled allergens using CRISPR-Cas9, such as the development of pollen-free Japanese cedar trees.94 CRISPR-Cas9 was used to knock out the major allergen produced by domestic cats, Fel d 1, in a non-expressing cell line.95 In vitro CRISPR knockouts of the Fel d 1 genes, CH1 and CH2, resulted in editing efficiencies of up to 55%, confirming that the allergen is a viable target for gene deletion in an approach to create Fel d 1-free cats. Accompanying comparative sequence analyses of Fel d 1, of which the biologic function in cats remains unknown, revealed that the allergen genes may not be conserved or biologically essential for cats.95 Deleting Fel d 1 in cats using CRISPR technology could significantly benefit cat allergy sufferers by removing the allergen from the animal, and may provide further insight into the definitive function of the Fel d 1 protein.

Major food allergens from hen’s egg, milk, soybean, peanut, and wheat have also been targeted with CRISPR gene editing (Figure 4). CRISPR-Cas9 demonstrated editing efficiencies of up to 90% in knockouts of egg white proteins in chicken primordial germ cells.96 Targeting β-lactoglobulin (BLG), a milk whey protein allergen, with CRISPR-Cas9 in goat embryos resulted in editing efficiencies of ~25% and knockout goats with significantly less BLG protein expression in milk.97 Preliminary knockouts of two allergenic soybean proteins demonstrated proof-of-principle for developing hypoallergenic soybean plants, while proposed CRISPR knockouts of several major allergens in peanut highlight the therapeutic potential of CRISPR in tackling life-threatening allergic reactions to peanut.98, 99 Alternatively, knocking out immunodominant epitopes in α-gliadin gluten proteins using CRISPR-Cas9 resulted in editing efficiencies of up to 75% in an approach to produce bread and durum wheat lines that lack epitopes associated with celiac disease.100

Though the above applications demonstrate the utility of CRISPR-Cas9 in knocking out allergens with targeted DNA double-strand breaks, alternative CRISPR systems such as base or prime editors will enable precise, single nucleotide edits at specified DNA targets for the modification of critical IgE epitopes and the subsequent development of hypoallergens (Figure 4).101–103 In contrast with the production of hypoallergens by removing specific IgE epitopes using conventional recombinant technologies104, the latest CRISPR systems will allow their production directly from the allergen source. Precision engineering with CRISPR base or prime editors could also be applied to impair IgE recognition of allergen epitopes while preserving the underlying function of the protein, similar to a recent approach to render immune cells unrecognizable by anti-CD45 CAR-T cells.105 While CRISPR base or prime editing have yet to be applied in allergy, these systems have shown therapeutic promise in preclinical and clinical studies of several monogenic disorders, including sickle cell disease, T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and Duchenne muscular dystrophy.106, 107 In the future, CRISPR editing in allergy could further inform the allergen-IgE interaction or reveal essential functions of allergen proteins, and CRISPR-engineered (hypo)allergens may serve as valuable therapeutic alternatives for managing and treating allergic disease.

Limitations and Challenges

Limitations and challenges for identifying IgE antibody epitopes in structural studies are: 1) obtaining the hIgE mAb of the desired specificity, 2) the need for multiple screening allergens to determine IgE mAb specificity, and 3) the need for homogenous and properly folded allergen and hIgE mAb molecules. Recombinant allergens might not always fold correctly or might lack post-translational modifications that occur in the natural counterpart and that might be needed for IgE antibody binding (e.g. glycosylation or hydroxylation of prolines as in peanut Ara h 2).42, 108 Proof of IgE mAb binding to the allergen indicates proper folding of both molecules, which can be confirmed by CD spectra or NMR analyses. Another potential challenge that could impair or prevent crystallization, is that natural allergens might either have molecular impurities (including other allergens) or several variants or isoforms. Nevertheless, this last possibility did not prevent the determination of the structure of group 1 mite allergens with Fab from murine IgG mAb. Fortunately, the crystals contained a major isoform (Der f 1.0101 and Der p 1.0105 in complex with the Fab from the IgG mAb 4C1), despite the large number of isoforms listed for these allergens in the WHO/IUIS Allergen Nomenclature database.109

The structures of allergen-antibody complexes provide information on how the human humoral immune system interacts with allergens. There are potential limitations of focusing on a few antibodies given the fact that IgE responses are polyclonal and vary among patients. However, once a group of IgE mAb recognizing different epitopes on an allergen have been identified, they can be pooled and compared with polyclonal IgE responses in allergic patients (which has not previously been possible). In addition, mutagenesis analyses of each epitope allows one to identify the relevance of that epitope versus the full allergen-specific IgE repertoire and its degree of dominance in a population of subjects sensitized to that allergen, as it has been reported for the dominant IgE mAb 2F10 epitope on Der p 2 (Figure 2).22

A primary challenge of CRISPR engineering is the potential for off target editing in unintended genomic sites.110 This risk is mitigated by employing bioinformatics tools to predict or detect genome-wide, CRISPR-mediated DNA breaks, or by using alternative CRISPR systems with reduced off target potential.101–103, 111–113 Polyploid genomes pose the additional challenge of targeting several alleles simultaneously to achieve a successful knockout.114 Nevertheless, the high efficiency and versatility of CRISPR systems will undoubtedly improve polyploid genome engineering compared to preceding technologies, with successful CRISPR editing already reported in several plant species including wheat.100, 114

Focused Conclusions

Despite the worldwide increase in allergies in the last 30 years, and the continuous discovery of new allergens from different sources (www.allergen.org), a knowledge gap remains regarding how specific interactions between allergens and IgE antibodies occur. Epitope mapping studies identify specific residues on allergens, which are recognized by IgE antibodies. Key elements of these studies involve high resolution analyses of allergen-antibody complexes by X-ray crystallography, NMR and cryo-EM, coupled with the use of hIgE mAb derived from subjects with allergic disease to define allergenic epitopes. Large panels of hIgE mAb to inhaled allergens, food allergens, alpha-gal and parasite antigens have been produced to facilitate analysis of IgE B cell epitopes. Clinically, IgE epitopes allow the specificity and cross-reactivity of homologous allergens to be defined, which is useful for diagnostic purposes. Potential therapeutic applications include engineered modified allergens, with reduced IgE reactivity, to reduce side effects from immunotherapy. Finally, recent clinical trials showed that non-overlapping IgG monoclonal antibodies to Fel d 1 can block IgE antibody binding to the allergen. The two anti-Fel d 1 IgG antibodies reduced symptoms in patients with cat allergy and prevented cat allergen–induced early asthmatic responses in an environmental exposure unit. 115, 116 Similar trials showed that three Bet v 1-specific IgG antibodies blocked the birch pollen allergic response.20 The use of IgE-blocking IgG antibodies is another interesting option for future therapies.

Suggestions for future work

Continued structural analysis of the epitopes recognized by hIgE mAb on inhalant allergens and food allergens, with the goal of mapping the entire allergenic surfaces of these molecules. This will be especially important for identifying the actual IgE epitopes on food allergens and whether they are linear or conformational.

While current epitope mapping techniques provide spectacular atomic detail, there is significant effort involved in every single complex structure. Development of higher throughput approaches is needed to elucidate the repertoire(s) of IgE epitopes from allergic patients and, possibly, patient-specific epitope repertoires. If certain epitopes are common, they could be targets for hypoallergen design, or markers of disease severity or therapeutic success.

Applying the latest CRISPR technologies, base and prime editors, as a more efficient approach to traditional mutagenesis for the identification and development of hypoallergens at the source, or other beneficial mutations in allergen molecules.

Clinical studies that will be designed to compare the repertoires of IgE epitopes in children and adults with different allergic conditions.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AI077653-13 (to AP, MDC and MC), as well as R21AI123307 and R01AI155668 (to SAS). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, ZIA-ES102906 (GAM).

Abbreviations:

- BLG

β-lactoglobulin

- CDR

Complementary determining region/s

- CRISPR

Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats

- Cryo-EM

Cryo-electron microscopy

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay/s

- Fab

Fragment antigen-binding

- HAT

Hypoxanthine-aminopterin-thymidine

- HDX

Hydrogen-deuterium (1H-2H) exchange

- hIgE mAb

Human IgE monoclonal antibodies

- IMGT

ImMunoGeneTics

- mAb

Monoclonal antibody/ies

- NMR

Nuclear magnetic resonance

- PBMC

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell/s

- RT-PCR

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- scFv

Single-chain variable fragment

- scRNAseq

Single cell RNA sequencing

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: AP, NFB and MDC are employees of InBio. This research is funded by an NIH/NIAID award to InBio. AP is the contact principal investigator of the NIH R01 award that provided funding for the study. MDC has a financial interest in InBio and is a co-investigator on the NIH R01 award. The hIgE mAb and some of the allergens described herein were produced by InBio. InBio has a license agreement with Vanderbilt University Medical Center for commercialization of hIgE mAb for research and diagnostic purposes. The hIgE mAb covered by this agreement are available from InBio (www.inbio.com). SAS is an inventor on U.S. patent 10908168-B2 for generation of human IgE monoclonal antibodies, has received patent royalties and has related patents pending. The rest of the authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Radauer C, Bublin M, Wagner S, Mari A, Breiteneder H. Allergens are distributed into few protein families and possess a restricted number of biochemical functions. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008; 121:847–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pomés A, Davies JM, Gadermaier G, Hilger C, Holzhauser T, Lidholm J, et al. WHO/IUIS Allergen Nomenclature: Providing a common language. Mol Immunol 2018; 100:3–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pomés A, Chruszcz M, Gustchina A, Minor W, Mueller GA, Pedersen LC, et al. 100 Years later: Celebrating the contributions of x-ray crystallography to allergy and clinical immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015; 136:29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dramburg S, Hilger C, Santos AF, de Las Vecillas L, Aalberse RC, Acevedo N, et al. EAACI Molecular Allergology User’s Guide 2.0. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2023; 34 Suppl 28:e13854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takai T, Yokota T, Yasue M, Nishiyama C, Yuuki T, Mori A, et al. Engineering of the major house dust mite allergen Der f 2 for allergen-specific immunotherapy. Nat. Biotechnol 1997; 15:754–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith AM, Chapman MD. Reduction in IgE binding to allergen variants generated by site-directed mutagenesis: contribution of disulfide bonds to the antigenic structure of the major house dust mite allergen Der p 2. Mol Immunol 1996; 33:399–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gadermaier G, Jahn-Schmid B, Vogel L, Egger M, Himly M, Briza P, et al. Targeting the cysteine-stabilized fold of Art v 1 for immunotherapy of Artemisia pollen allergy. Mol Immunol 2010; 47:1292–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cromwell O, Hafner D, Nandy A. Recombinant allergens for specific immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 127:865–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valenta R, Campana R, Niederberger V. Recombinant allergy vaccines based on allergen-derived B cell epitopes. Immunol Lett 2017; 189:19–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lombardero M, Heymann PW, Platts-Mills TA, Fox JW, Chapman MD. Conformational stability of B cell epitopes on group I and group II Dermatophagoides spp. allergens. Effect of thermal and chemical denaturation on the binding of murine IgG and human IgE antibodies. J Immunol 1990; 144:1353–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pomés A, Mueller GA, Chruszcz M. Structural aspects of the allergen-antibody Interaction. Front Immunol 2020; 11:2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kühne Y, Reese G, Ballmer-Weber BK, Niggemann B, Hanschmann KM, Vieths S, et al. A novel multipeptide microarray for the specific and sensitive mapping of linear IgE-binding epitopes of food allergens. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2015; 166:213–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin J, Bardina L, Shreffler WG, Andreae DA, Ge Y, Wang J, et al. Development of a novel peptide microarray for large-scale epitope mapping of food allergens. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009; 124:315–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jarvinen KM, Beyer K, Vila L, Bardina L, Mishoe M, Sampson HA. Specificity of IgE antibodies to sequential epitopes of hen’s egg ovomucoid as a marker for persistence of egg allergy. Allergy 2007; 62:758–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santos AF, Barbosa-Morais NL, Hurlburt BK, Ramaswamy S, Hemmings O, Kwok M, et al. IgE to epitopes of Ara h 2 enhance the diagnostic accuracy of Ara h 2-specific IgE. Allergy 2020; 75:2309–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suprun M, Kearney P, Hayward C, Butler H, Getts R, Sicherer SH, et al. Predicting probability of tolerating discrete amounts of peanut protein in allergic children using epitope-specific IgE antibody profiling. Allergy 2022; 77:3061–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albrecht M, Kuhne Y, Ballmer-Weber BK, Becker WM, Holzhauser T, Lauer I, et al. Relevance of IgE binding to short peptides for the allergenic activity of food allergens. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009; 124:328–36, 36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen X, Negi SS, Liao S, Gao V, Braun W, Dreskin SC. Conformational IgE epitopes of peanut allergens Ara h 2 and Ara h 6. Clin Exp Allergy 2016; 46:1120–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hazebrouck S, Patil SU, Guillon B, Lahood N, Dreskin SC, Adel-Patient K, et al. Immunodominant conformational and linear IgE epitopes lie in a single segment of Ara h 2. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2022; 150:131–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atanasio A, Franklin MC, Kamat V, Hernandez AR, Badithe A, Ben LH, et al. Targeting immunodominant Bet v 1 epitopes with monoclonal antibodies prevents the birch allergic response. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2022; 149:200–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LaHood NA, Min J, Keswani T, Richardson CM, Amoako K, Zhou J, et al. Immunotherapy-induced neutralizing antibodies disrupt allergen binding and sustain allergen tolerance in peanut allergy. J Clin Invest 2023; 133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khatri K, Richardson CM, Glesner J, Kapingidza AB, Mueller GA, Zhang J, et al. Human IgE monoclonal antibody recognition of mite allergen Der p 2 defines structural basis of an epitope for IgE cross-linking and anaphylaxis in vivo. PNAS Nexus 2022; 1:pgac054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brackett NF, Pomés A, Chapman MD. New frontiers: Precise editing of allergen genes using CRISPR. Front Allergy 2021; 2:821107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith SA, Chruszcz M, Chapman MD, Pomés A. Human monoclonal IgE antibodies-a major milestone in allergy. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2023; 23:53–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amit AG, Mariuzza RA, Phillips SE, Poljak RJ. Three-dimensional structure of an antigen-antibody complex at 6 A resolution. Nature 1985; 313:156–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mirza O, Henriksen A, Ipsen H, Larsen JN, Wissenbach M, Spangfort MD, et al. Dominant epitopes and allergic cross-reactivity: complex formation between a Fab fragment of a monoclonal murine IgG antibody and the major allergen from birch pollen Bet v 1. J Immunol 2000; 165:331–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glesner J, Wunschmann S, Li M, Gustchina A, Wlodawer A, Himly M, et al. Mechanisms of allergen-antibody interaction of cockroach allergen Bla g 2 with monoclonal antibodies that inhibit IgE antibody binding. PLoS ONE 2011; 6:e22223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glesner J, Vailes LD, Schlachter C, Mank N, Minor W, Osinski T, et al. Antigenic determinants of Der p 1: specificity and cross-reactivity associated with IgE antibody recognition. J. Immunol 2017; 198:1334–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woodfolk JA, Glesner J, Wright PW, Kepley CL, Li M, Himly M, et al. Antigenic determinants of the bilobal cockroach allergen Bla g 2. J Biol Chem 2016; 291:2288–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glesner J, Kapingidza AB, Godzwon M, Offermann LR, Mueller GA, DeRose EF, et al. A human IgE antibody binding site on Der p 2 for the design of a recombinant allergen for immunotherapy. J Immunol 2019; 203:2545–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu JL, Davis MM. Diversity in the CDR3 region of V(H) is sufficient for most antibody specificities. Immunity 2000; 13:37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Madsen JL, Kroghsbo S, Madsen CB, Pozdnyakova I, Barkholt V, Bogh KL. The impact of structural integrity and route of administration on the antibody specificity against three cow’s milk allergens - a study in Brown Norway rats. Clin Transl Allergy 2014; 4:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pali-Scholl I, Untersmayr E, Klems M, Jensen-Jarolim E. The effect of digestion and digestibility on allergenicity of food. Nutrients 2018; 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin-Pedraza L, Mayorga C, Gomez F, Bueno-Diaz C, Blanca-Lopez N, Gonzalez M, et al. IgE-Reactivity pattern of tomato seed and peel nonspecific lipid-transfer proteins after in vitro gastrointestinal digestion. J Agric Food Chem 2021; 69:3511–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maynard F, Jost R, Wal JM. Human IgE binding capacity of tryptic peptides from bovine alpha-lactalbumin. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 1997; 113:478–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Des Roches A, Nguyen M, Paradis L, Primeau MN, Singer S. Tolerance to cooked egg in an egg allergic population. Allergy 2006; 61:900–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Bloom KA, Sicherer SH, Shreffler WG, Noone S, Wanich N, et al. Tolerance to extensively heated milk in children with cow’s milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008; 122:342–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ehlers AM, Otten HG, Wierzba E, Flugge U, Le TM, Knulst AC, et al. Detection of specific IgE against linear epitopes from Gal d 1 has additional value in diagnosing hen’s egg allergy in adults. Clin Exp Allergy 2020; 50:1415–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Caubet JC, Nowak-Węgrzyn A, Moshier E, Godbold J, Julie W, Sampson HA. Utility of casein-specific IgE levels in predicting reactivity to baked milk. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 131:222–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greene WK, Thomas WR. IgE binding structures of the major house dust mite allergen Der p I. Mol Immunol 1992; 29:257–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burks AW, Shin D, Cockrell G, Stanley JS, Helm RM, Bannon GA. Mapping and mutational analysis of the IgE-binding epitopes on Ara h 1, a legume vicilin protein and a major allergen in peanut hypersensitivity. Eur J Biochem 1997; 245:334–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bernard H, Guillon B, Drumare MF, Paty E, Dreskin SC, Wal JM, et al. Allergenicity of peanut component Ara h 2: Contribution of conformational versus linear hydroxyproline-containing epitopes. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015; 135:1267–74 e1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suprun M, Getts R, Raghunathan R, Grishina G, Witmer M, Gimenez G, et al. Novel bead-based epitope assay is a sensitive and reliable tool for profiling epitope-specific antibody repertoire in food allergy. Sci Rep 2019; 9:18425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suprun M, Getts R, Grishina G, Tsuang A, Suárez-Fariñas M, Sampson HA. Ovomucoid epitope-specific repertoire of IgE, IgG(4), IgG(1), IgA(1), and IgD antibodies in egg-allergic children. Allergy 2020; 75:2633–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krause T, Rockendorf N, Meckelein B, Sinnecker H, Schwager C, Mockel S, et al. IgE epitope profiling for allergy diagnosis and therapy - Parallel analysis of a multitude of potential linear epitopes using a high throughput screening platform. Front Immunol 2020; 11:565243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suárez-Fariñas M, Suprun M, Kearney P, Getts R, Grishina G, Hayward C, et al. Accurate and reproducible diagnosis of peanut allergy using epitope mapping. Allergy 2021; 76:3789–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Suárez-Fariñas M, Suprun M, Bahnson HT, Raghunathan R, Getts R, duToit G, et al. Evolution of epitope-specific IgE and IgG4 antibodies in children enrolled in the LEAP trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2021; 148:835–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Santos AF, Kulis MD, Sampson HA. Bringing the next generation of food allergy diagnostics into the clinic. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2022; 10:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Suprun M, Bahnson HT, du Toit G, Lack G, Suárez-Fariñas M, Sampson HA. In children with eczema, expansion of epitope-specific IgE is associated with peanut allergy at 5 years of age. Allergy 2023; 78:586–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Monaco DR, Sie BM, Nirschl TR, Knight AC, Sampson HA, Nowak-Wegrzyn A, et al. Profiling serum antibodies with a pan allergen phage library identifies key wheat allergy epitopes. Nat Commun 2021; 12:379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen G, Shrock EL, Li MZ, Spergel JM, Nadeau KC, Pongracic JA, et al. High-resolution epitope mapping by AllerScan reveals relationships between IgE and IgG repertoires during peanut oral immunotherapy. Cell Rep Med 2021; 2:100410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mikus M, Zandian A, Sjoberg R, Hamsten C, Forsstrom B, Andersson M, et al. Allergome-wide peptide microarrays enable epitope deconvolution in allergen-specific immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2021; 147:1077–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kamath SD, Bublin M, Kitamura K, Matsui T, Ito K, Lopata AL. Cross-reactive epitopes and their role in food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2023; 151:1178–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Croote D, Darmanis S, Nadeau KC, Quake SR. High-affinity allergen-specific human antibodies cloned from single IgE B cell transcriptomes. Science 2018; 362:1306–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wurth MA, Hadadianpour A, Horvath DJ, Daniel J, Bogdan O, Goleniewska K, et al. Human IgE mAbs define variability in commercial Aspergillus extract allergen composition. JCI Insight 2018; 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tiller T, Meffre E, Yurasov S, Tsuiji M, Nussenzweig MC, Wardemann H. Efficient generation of monoclonal antibodies from single human B cells by single cell RT-PCR and expression vector cloning. J Immunol Methods 2008; 329:112–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Horst A, Hunzelmann N, Arce S, Herber M, Manz RA, Radbruch A, et al. Detection and characterization of plasma cells in peripheral blood: correlation of IgE+ plasma cell frequency with IgE serum titre. Clin Exp. Immunol 2002; 130:370–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hoh RA, Joshi SA, Liu Y, Wang C, Roskin KM, Lee JY, et al. Single B-cell deconvolution of peanut-specific antibody responses in allergic patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016; 137:157–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Croote D, Wong JJW, Pecalvel C, Leveque E, Casanovas N, Kamphuis JBJ, et al. Widespread monoclonal IgE antibody convergence to an immunodominant, proanaphylactic Ara h 2 epitope in peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smith SA, Zhou Y, Olivarez NP, Broadwater AH, de Silva AM, Crowe JE, Jr. Persistence of circulating memory B cell clones with potential for dengue virus disease enhancement for decades following infection. J Virol 2012; 86:2665–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smith SA, Crowe JE Jr. Use of human hybridoma technology to isolate human monoclonal antibodies . Microbiol Spectr 2015; 3:AID-0027-2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smith SA, Silva LA, Fox JM, Flyak AI, Kose N, Sapparapu G, et al. Isolation and characterization of broad and ultrapotent human monoclonal antibodies with therapeutic activity against Chikungunya Virus. Cell Host Microbe 2015; 18:86–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sapparapu G, Czako R, Alvarado G, Shanker S, Prasad BV, Atmar RL, et al. Frequent use of the IgA isotype in human B Cells encoding potent norovirus-specific monoclonal antibodies that block HBGA binding. PLoS Pathog 2016; 12:e1005719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hadadianpour A, Daniel J, Zhang J, Spiller BW, Makaraviciute A, DeWitt AM, et al. Human IgE mAbs identify major antigens of parasitic worm infection. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2022; 150:1525–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Newman J, Rice JS, Wang C, Harris SL, Diamond B. Identification of an antigen-specific B cell population. J Immunol Methods 2003; 272:177–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Traggiai E, Becker S, Subbarao K, Kolesnikova L, Uematsu Y, Gismondo MR, et al. An efficient method to make human monoclonal antibodies from memory B cells: potent neutralization of SARS coronavirus. Nat Med 2004; 10:871–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wrammert J, Smith K, Miller J, Langley WA, Kokko K, Larsen C, et al. Rapid cloning of high-affinity human monoclonal antibodies against influenza virus. Nature 2008; 453:667–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Achatz G, Nitschke L, Lamers MC. Effect of transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains of IgE on the IgE response. Science 1997; 276:409–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Berkowska MA, Heeringa JJ, Hajdarbegovic E, van der Burg M, Thio HB, van Hagen PM, et al. Human IgE(+) B cells are derived from T cell-dependent and T cell-independent pathways. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014; 134:688–97 e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Karnowski A, Achatz-Straussberger G, Klockenbusch C, Achatz G, Lamers MC. Inefficient processing of mRNA for the membrane form of IgE is a genetic mechanism to limit recruitment of IgE-secreting cells. Eur J Immunol 2006; 36:1917–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Oliveria JP, Salter BM, MacLean J, Kotwal S, Smith A, Harris JM, et al. Increased IgE(+) B cells in sputum, but not blood, bone marrow, or tonsils, after inhaled allergen challenge in subjects with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017; 196:107–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Oliveria JP, Salter BM, Phan S, Obminski CD, Munoz CE, Smith SG, et al. Asthmatic subjects with allergy have elevated levels of IgE+ B cells in the airways. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017; 140:590–3 e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pene J, Rousset F, Briere F, Chretien I, Bonnefoy JY, Spits H, et al. IgE production by normal human lymphocytes is induced by interleukin 4 and suppressed by interferons gamma and alpha and prostaglandin E2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1988; 85:6880–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jabara HH, Fu SM, Geha RS, Vercelli D. CD40 and IgE: synergism between anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody and interleukin 4 in the induction of IgE synthesis by highly purified human B cells. J Exp Med 1990; 172:1861–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gascan H, Gauchat JF, Aversa G, Van Vlasselaer P, de Vries JE. Anti-CD40 monoclonal antibodies or CD4+ T cell clones and IL-4 induce IgG4 and IgE switching in purified human B cells via different signaling pathways. J Immunol 1991; 147:8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Smith BRE, Reid Black K, Bermingham M, Agah S, Glesner J, Versteeg SA, et al. Unique allergen-specific human IgE monoclonal antibodies derived from patients with allergic disease. Front Allergy 2023; 4:1270326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Heeringa JJ, Rijvers L, Arends NJ, Driessen GJ, Pasmans SG, van Dongen JJM, et al. IgE-expressing memory B cells and plasmablasts are increased in blood of children with asthma, food allergy, and atopic dermatitis. Allergy 2018; 73:1331–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Garcia-Ramirez B, Mares-Mejia I, Rodriguez-Hernandez A, Cano-Sanchez P, Torres-Larios A, Ortega E, et al. A native IgE in complex with profilin provides insights into allergen recognition and cross-reactivity. Commun Biol 2022; 5:748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Padavattan S, Schirmer T, Schmidt M, Akdis C, Valenta R, Mittermann I, et al. Identification of a B-cell epitope of hyaluronidase, a major bee venom allergen, from its crystal structure in complex with a specific Fab. J Mol Biol 2007; 368:742–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhu S, Liuni P, Chen T, Houy C, Wilson DJ, James DA. Epitope screening using Hydrogen/Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS): An accelerated workflow for evaluation of lead monoclonal antibodies. Biotechnol J 2022; 17:e2100358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jethva PN, Gross ML. Hydrogen deuterium exchange and other mass spectrometry-based approaches for epitope mapping. Front Anal Sci 2023; 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Masson GR, Burke JE, Ahn NG, Anand GS, Borchers C, Brier S, et al. Recommendations for performing, interpreting and reporting hydrogen deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS) experiments. Nat Methods 2019; 16:595–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Foo ACY, Nesbit JB, Gipson SAY, Cheng H, Bushel P, DeRose EF, et al. Structure, immunogenicity, and IgE cross-reactivity among walnut and peanut vicilin-buried peptides. J Agric Food Chem 2022; 70:2389–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Foo ACY, Nesbit JB, Gipson SAY, DeRose EF, Cheng H, Hurlburt BK, et al. Structure and IgE cross-reactivity among cashew, pistachio, walnut, and peanut vicilin-buried peptides. J Agric Food Chem 2023; 71:2990–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Eidelpes R, Hofer F, Rock M, Fuhrer S, Kamenik AS, Liedl KR, et al. Structure and zeatin binding of the peach allergen Pru p 1. J Agric Food Chem 2021; 69:8120–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mueller GA, Glesner J, Daniel JL, Zhang J, Hyduke N, Richardson CM, et al. Mapping human monoclonal IgE epitopes on the major dust mite allergen Der p 2. J Immunol 2020; 205:1999–2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Naik MT, Chang CF, Kuo IC, Kung CC, Yi FC, Chua KY, et al. Roles of structure and structural dynamics in the antibody recognition of the allergen proteins: an NMR study on Blomia tropicalis major allergen. Structure 2008; 16:125–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bublin M, Kostadinova M, Fuchs JE, Ackerbauer D, Moraes AH, Almeida FC, et al. A cross-reactive human single-chain antibody for detection of major fish allergens, parvalbumins, and identification of a major IgE-binding epitope. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0142625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wilkinson IC, Hall CJ, Veverka V, Shi JY, Muskett FW, Stephens PE, et al. High resolution NMR-based model for the structure of a scFv-IL-1beta complex: potential for NMR as a key tool in therapeutic antibody design and development. J Biol Chem 2009; 284:31928–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wentinck K, Gogou C, Meijer DH. Putting on molecular weight: Enabling cryo-EM structure determination of sub-100-kDa proteins. Curr Res Struct Biol 2022; 4:332–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Barrangou R, Fremaux C, Deveau H, Richards M, Boyaval P, Moineau S, et al. CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes. Science 2007; 315:1709–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 2012; 337:816–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sander JD, Joung JK. CRISPR-Cas systems for editing, regulating and targeting genomes. Nat. Biotechnol 2014; 32:347–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nishiguchi M, Futamura N, Endo M, Mikami M, Toki S, Katahata SI, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated disruption of CjACOS5 confers no-pollen formation on sugi trees (Cryptomeria japonica D. Don). Sci Rep 2023; 13:11779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Brackett NF, Davis BW, Adli M, Pomés A, Chapman MD. Evolutionary biology and gene editing of cat allergen, Fel d 1. CRISPR J 2022; 5:213–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Oishi I, Yoshii K, Miyahara D, Kagami H, Tagami T. Targeted mutagenesis in chicken using CRISPR/Cas9 system. Sci Rep 2016; 6:23980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhou W, Wan Y, Guo R, Deng M, Deng K, Wang Z, et al. Generation of beta-lactoglobulin knock-out goats using CRISPR/Cas9. PLoS One 2017; 12:e0186056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sugano S, Hirose A, Kanazashi Y, Adachi K, Hibara M, Itoh T, et al. Simultaneous induction of mutant alleles of two allergenic genes in soybean by using site-directed mutagenesis. BMC Plant Biol 2020; 20:513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Dodo H SBIR Phase II: Development of an allergen-free peanut using genome editing technology. National Science Foundation, Contract 2036153, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sanchez-Leon S, Gil-Humanes J, Ozuna CV, Gimenez MJ, Sousa C, Voytas DF, et al. Low-gluten, nontransgenic wheat engineered with CRISPR/Cas9. Plant Biotechnol J 2018; 16:902–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Komor AC, Kim YB, Packer MS, Zuris JA, Liu DR. Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature 2016; 533:420–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gaudelli NM, Komor AC, Rees HA, Packer MS, Badran AH, Bryson DI, et al. Programmable base editing of A*T to G*C in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Nature 2017; 551:464–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Anzalone AV, Randolph PB, Davis JR, Sousa AA, Koblan LW, Levy JM, et al. Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA. Nature 2019; 576:149–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tscheppe A, Palmberger D, van Rijt L, Kalic T, Mayr V, Palladino C, et al. Development of a novel Ara h 2 hypoallergen with no IgE binding or anaphylactogenic activity. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2020; 145:229–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wellhausen NR, Lesch S, Agarwal S, Charria B, Choi G, R.M. Y, et al. Epitope editing in hematopoietic cells enables CD45-directed immune therapy. Blood 2022:862–4. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Porto EM, Komor AC. In the business of base editors: Evolution from bench to bedside. PLoS Biol 2023; 21:e3002071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zhao Z, Shang P, Mohanraju P, Geijsen N. Prime editing: advances and therapeutic applications. Trends Biotechnol 2023; 41:1000–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Li J, Shefcheck K, Callahan J, Fenselau C. Primary sequence and site-selective hydroxylation of prolines in isoforms of a major peanut allergen protein Ara h 2. Protein Sci 2010; 19:174–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Chruszcz M, Pomés A, Glesner J, Vailes LD, Osinski T, Porebski PJ, et al. Molecular determinants for antibody binding on group 1 house dust mite allergens. J Biol Chem 2012; 287:7388–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tsai SQ, Joung JK. Defining and improving the genome-wide specificities of CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases. Nat Rev Genet 2016; 17:300–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tsai SQ, Zheng Z, Nguyen NT, Liebers M, Topkar VV, Thapar V, et al. GUIDE-seq enables genome-wide profiling of off-target cleavage by CRISPR-Cas nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol 2015; 33:187–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kim D, Bae S, Park J, Kim E, Kim S, Yu HR, et al. Digenome-seq: genome-wide profiling of CRISPR-Cas9 off-target effects in human cells. Nat Methods 2015; 12:237–43, 1 p following 43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ran FA, Hsu PD, Lin CY, Gootenberg JS, Konermann S, Trevino AE, et al. Double nicking by RNA-guided CRISPR Cas9 for enhanced genome editing specificity. Cell 2013; 154:1380–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Schaart JG, van de Wiel CCM, Smulders MJM. Genome editing of polyploid crops: prospects, achievements and bottlenecks. Transgenic Res 2021; 30:337–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.de Blay FJ, Gherasim A, Domis N, Meier P, Shawki F, Wang CQ, et al. REGN1908/1909 prevented cat allergen-induced early asthmatic responses in an environmental exposure unit. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2022; 150:1437–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Orengo JM, Radin AR, Kamat V, Badithe A, Ben LH, Bennett BL, et al. Treating cat allergy with monoclonal IgG antibodies that bind allergen and prevent IgE engagement. Nat Commun 2018; 9:1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Li M, Gustchina A, Alexandratos J, Wlodawer A, Wunschmann S, Kepley CL, et al. Crystal structure of a dimerized cockroach allergen Bla g 2 complexed with a monoclonal antibody. J Biol Chem 2008; 283:22806–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Li M, Gustchina A, Glesner J, Wunschmann S, Vailes LD, Chapman MD, et al. Carbohydrates contribute to the interactions between cockroach allergen Bla g 2 and a monoclonal antibody. J Immunol 2011; 186:333–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Osinski T, Pomés A, Majorek KA, Glesner J, Offermann LR, Vailes LD, et al. Structural analysis of Der p 1-antibody complexes and comparison with complexes of proteins or peptides with monoclonal antibodies. J Immunol 2015; 195:307–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Padlan EA, Silverton EW, Sheriff S, Cohen GH, Smith-Gill SJ, Davies DR. Structure of an antibody-antigen complex: crystal structure of the HyHEL-10 Fab-lysozyme complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A 1989; 86:5938–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Fischmann TO, Bentley GA, Bhat TN, Boulot G, Mariuzza RA, Phillips SE, et al. Crystallographic refinement of the three-dimensional structure of the FabD1.3-lysozyme complex at 2.5-A resolution. J Biol Chem 1991; 266:12915–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Braden BC, Souchon H, Eisele JL, Bentley GA, Bhat TN, Navaza J, et al. Three-dimensional structures of the free and the antigen-complexed Fab from monoclonal anti-lysozyme antibody D44.1. J Mol Biol 1994; 243:767–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Cohen GH, Silverton EW, Padlan EA, Dyda F, Wibbenmeyer JA, Willson RC, et al. Water molecules in the antibody-antigen interface of the structure of the Fab HyHEL-5-lysozyme complex at 1.7 A resolution: comparison with results from isothermal titration calorimetry. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol Crystallogr 2005; 61:628–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Rouet R, Dudgeon K, Christie M, Langley D, Christ D. Fully human VH single domains that rival the stability and cleft recognition of camelid antibodies. J Biol Chem 2015; 290:11905–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Mitropoulou AN, Bowen H, Dodev TS, Davies AM, Bax HJ, Beavil RL, et al. Structure of a patient-derived antibody in complex with allergen reveals simultaneous conventional and superantigen-like recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2018; 115:E8707–E16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Niemi M, Jylha S, Laukkanen ML, Soderlund H, Makinen-Kiljunen S, Kallio JM, et al. Molecular interactions between a recombinant IgE antibody and the beta-lactoglobulin allergen. Structure 2007; 15:1413–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Padavattan S, Flicker S, Schirmer T, Madritsch C, Randow S, Reese G, et al. High-affinity IgE recognition of a conformational epitope of the major respiratory allergen Phl p 2 as revealed by X-ray crystallography. J Immunol 2009; 182:2141–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J Mol Biol 2007; 372:774–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]