Abstract

Context

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a heterogeneous disorder, with disease loci identified from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) having largely unknown relationships to disease pathogenesis.

Objective

This work aimed to group PCOS GWAS loci into genetic clusters associated with disease pathophysiology.

Methods

Cluster analysis was performed for 60 PCOS-associated genetic variants and 49 traits using GWAS summary statistics. Cluster-specific PCOS partitioned polygenic scores (pPS) were generated and tested for association with clinical phenotypes in the Mass General Brigham Biobank (MGBB, N = 62 252). Associations with clinical outcomes (type 2 diabetes [T2D], coronary artery disease [CAD], and female reproductive traits) were assessed using both GWAS-based pPS (DIAMANTE, N = 898,130, CARDIOGRAM/UKBB, N = 547 261) and individual-level pPS in MGBB.

Results

Four PCOS genetic clusters were identified with top loci indicated as following: (i) cluster 1/obesity/insulin resistance (FTO); (ii) cluster 2/hormonal/menstrual cycle changes (FSHB); (iii) cluster 3/blood markers/inflammation (ATXN2/SH2B3); (iv) cluster 4/metabolic changes (MAF, SLC38A11). Cluster pPS were associated with distinct clinical traits: Cluster 1 with increased body mass index (P = 6.6 × 10−29); cluster 2 with increased age of menarche (P = 1.5 × 10−4); cluster 3 with multiple decreased blood markers, including mean platelet volume (P = 3.1 ×10−5); and cluster 4 with increased alkaline phosphatase (P = .007). PCOS genetic clusters GWAS-pPSs were also associated with disease outcomes: cluster 1 pPS with increased T2D (odds ratio [OR] 1.07; P = 7.3 × 10−50), with replication in MGBB all participants (OR 1.09, P = 2.7 × 10−7) and females only (OR 1.11, 4.8 × 10−5).

Conclusion

Distinct genetic backgrounds in individuals with PCOS may underlie clinical heterogeneity and disease outcomes.

Keywords: PCOS, genetics, clustering, obesity, hormones, metabolic

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a complex condition affecting a large proportion of reproductive-age women worldwide (1, 2). PCOS is phenotypically heterogeneous and is characterized by clinical or biochemical evidence of hyperandrogenism (HA), chronic oligo/anovulation or ovulatory dysfunction (OD), and polycystic ovarian morphology (PCOM) on imaging (1, 3). The phenotypic heterogeneity of the syndrome is reflected by the diverse clinical presentation of women with PCOS, as well as the different diagnostic criteria, which are mainly based on expert opinion. The National Institutes of Health criteria define PCOS as the combination of HA and ovarian dysfunction, with 7% of women of reproductive age meeting these criteria. In contrast, the Rotterdam criteria, which includes HA and OD, or HA and PCOM, or OD and PCOM, increases the prevalence of the disease to 15% to 20% across different populations (1). In addition, PCOS is associated with other long-term adverse health outcomes, including insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes (T2D) (4), obesity (5), and coronary artery disease (CAD) (6).

The phenotypic heterogeneity observed in PCOS is in line with the underlying heterogeneous genetic architecture that has been linked to the disease. PCOS genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in Han Chinese and European women have identified disease-associated loci, with the largest meta-analysis to date detecting 19 loci at genome-wide significance (7-14). While the genetic architecture of PCOS appears to be similar across the various subtypes defined by different diagnostic criteria (13), linkage disequilibrium analyses have linked a subset of the identified loci to specific traits: the risk variants in close proximity to the gene encoding for follicle-stimulating hormone beta polypeptide (FSHB, rs11031006 and rs11031005) have been associated with lower FSH and higher luteinizing hormone (LH) and testosterone levels, pointing to a gonadotropin etiology (7, 13); variants near the genes DENN/MADD domain-containing protein 1A (DENND1A), THADA armadillo repeat-containing protein (THADA), and interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF1)/Rad50 double-strand break repair protein (RAD50) are linked to HA (13); and risk variants in close proximity to the genes encoding for Erb-B2 receptor tyrosine kinase 4 (ERBB4), Yes1-associated transcriptional regulator (YAP1), and zinc finger and BTB domain-containing protein 16 (ZBTB16) loci have been associated with polycystic morphology and ovarian dysfunction (13). In addition, variants near the genes encoding for the insulin receptor (INSR) and glycogen synthase 2 (GYS2) have been identified, linking the genetic background of PCOS to insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome (8-10).

To investigate whether the identified genetic loci have a direct effect on the clinical outcomes observed in PCOS, prior studies have attempted to link the phenotypic heterogeneity with PCOS genetic architecture through mendelian randomization analyses. Those analyses indicated causal roles for increased body mass index (BMI), higher insulin resistance, and later age of menopause in PCOS etiology (12). In addition, a recent phenotypic cluster analysis led to the identification of 3 distinct phenotypic subtypes of PCOS: i) a reproductive subtype characterized by high LH, high sex hormone-binding globulin, low BMI, and low insulin levels; (ii) a metabolic subtype characterized by high BMI, glucose, and insulin level, and low sex hormone-binding globulin and LH levels; and (iii) an indeterminate subtype. A GWAS was performed on the genotyped cohort and revealed 4 novel loci associated with the reproductive subtype (PRDM2/KAZN, BMPR1/UNC5C, CDH10); 1 novel locus linked to the metabolic subtype (KCNHF/FIGN); and 1 previously identified locus (FSHB) in the indeterminate subtype (14).

While approaches based on biomarkers and clinical data offer important insights, they are also limited by the nature of the variables in the analyses (ie, variables known to be associated with the disease of interest are usually selected for such analyses). GWAS have now been constructed across multiple traits, offering opportunities to elucidate shared disease mechanisms based on the assumption that genetic variants act along shared pathways. Such approaches, in theory, can allow for less biased inclusion of traits since the genetics (rather than preexisting knowledge of the disease) can guide whether a given trait has potential relevance to disease pathogenesis. Prior studies have used clustering techniques to group known genetic variants and have been able to uncover pathophysiological pathways contributing to the understanding of more complex phenotypes, such as T2D, gestational diabetes, hypertension, body fat distribution, and dietary intake (15-19). To illuminate pathophysiological mechanisms leading to PCOS, the objective of this present study was to identify physiologically related clusters of genetics variants associated with the syndrome and examine cross-sectionally the effect of cluster-specific polygenic risk scores on PCOS-related metabolic clinical outcomes, including T2D, CAD, and obesity.

Materials and Methods

Variant and Trait Selection

To obtain a comprehensive set of genetic variants associated with PCOS, we selected 1045 common single-nucleotide variations (SNVs; formerly single-nucleotide polymorphisms) aggregated by the most recent meta-analysis by Day et al and filtered by a P value threshold of 5e-5 (13). The subgenome significant threshold was chosen to boost the number of input SNVs, recognizing that they would contribute to downstream clusters only if they also had robust associations with input traits, thus, reducing the likelihood of inappropriate contamination. Proxy variants were included for indels, ambiguous, multiallelic, and low-count variants, with a total of 33 proxy variants being identified for the 91 variants that met these criteria. To ensure independent signals, linkage disequilibrium pruning was performed (r2 < 0.1), resulting in 60 SNVs (Supplementary Table S1 (20)) evaluated in total in this analysis. For trait selection, 72 GWAS summary statistics for reproductive, glycemic, anthropometric traits, vital signs, and additional laboratory measures in the AMP-CMDKP (Accelerating Medicines Partnership. Common Metabolic Diseases Knowledge Portal) (21) or UK Biobank (UKBB), a large-scale biomedical database and research resource, containing in-depth genetic and health information from half a million UK participants (22) (Supplementary Table S2 (20)), were considered. For each trait, we attempted to find the largest publicly available GWAS in terms of sample size. We intentionally looked for European cohorts to be consistent with the European-based PCOS summary statistics. Traits were included in the clustering analysis only if the minimum P value across the final set of variants was lower than a Bonferroni P value cutoff (.05/60) and filtered by correlation (r≥0.85) to reduce redundancy. After the filtering process, 49 traits were used in the clustering analysis.

Bayesian Nonnegative Matrix Factorization Clustering

Methods used by Udler et al (15) to cluster genetic variants and trait associations with Bayesian nonnegative matrix factorization (bNMF) were previously described in detail. In brief, summary statistics were gathered for the 60 PCOS variants from the 49 GWAS traits. Standardized effect sizes were calculated for each variant in each trait, with the effect sizes aligned to the PCOS risk-increasing alleles. Nonnegativity is a requirement of the bNMF algorithm, so the variant-trait association matrix (N variants × M traits) was broken down into columns with positive and negative associations for each trait (N variants × 2 M traits). As a result, positive and negative trait associations are individually clustered. The bNMF procedure then decomposes this resulting matrix into 2 component matrices that contain the variant and trait weights for each cluster, respectively. A Bayesian framework is used to determine the number of clusters (K) that best fit the data. Each cluster can be characterized by its most highly weighted variants and traits (15).

Study Population for Individual-Level Data Analysis

Individual-level participant data was analyzed from the Mass General Brigham Biobank (MGBB, formerly Partners HealthCare Biobank) (23), a multiethnic hospital-linked electronic medical record data set. The MGBB provides banked samples collected from patients who consented to broad-based research. The samples are linked to clinical data from the electronic health record, quantitative data derived from medical images, and survey data on lifestyle, environment, and family history. A subset of MGBB participants have undergone genotyping. To date, 145 179 patients have provided consent to join the MGBB and genomic data are available for 65 578 participants. Approval for analysis of the MGBB data was obtained from the Mass General Brigham institutional review board, protocol number 2018P002276. Disease prevalence for PCOS (n = 28 806 patient cases and 1025 controls), T2D (n = 3985 patient cases and 49 822 controls), and CAD (n = 3840 patient cases and 25 953 controls) were determined from electronic medical records. A set of continuous traits, which were based on 5-year median values, was also analyzed.

Cluster-Specific “Partitioned” Polygenic Scores

The top-weighted genetic variants in each cluster were used to build cluster-specific “partitioned” polygenic scores (pPS) in the MGBB (24). Cluster-specific pPS consisted of the sum of the number of PCOS alleles carried by an individual, each multiplied by their weights in the cluster. The threshold for the inclusion of variants in pPS was set at 0.83312 using a method previously described (15).

Genome-Wide Association Study–Partitioned Polygenic Scores for Reproductive Traits and Metabolic Outcomes

For analyses specifically related to the outcomes of T2D, CAD, and the number of spontaneous miscarriages (all of which were not included in clustering), we generated cluster-specific GWAS-pPS. The GWAS-pPS estimate the effect of cluster SNVs on outcomes studied in GWAS, which often have many more case end points than are available in studies with individual-level data used for pPS analyses (described earlier). Additionally, we generated GWAS-pPS for reproductive traits available in UKBB, given our specific interest in understanding how PCOS genetic clusters relate to these reproductive traits. The GWAS-pPS do not incorporate the cluster weights generated in the bNMF clustering. Instead, each variant in the cluster receives a weighted effect based on its effect size and standard error in the respective outcome's GWAS. The GWAS-pPS is simply the weighted average of the effects of the SNPs in a given cluster. Analyses were performed using data from the DIAMANTE analysis, that was conducted in 74 124 cases with T2D and 824 006 controls from 32 GWAS in individuals of European ancestry (25), the CARDIOGRAM/UK Biobank (UKBB) coronary artery disease (CAD) GWAS (34 541 cases with CAD and 261 984 controls of UKBB resource followed by replication in 88 192 cases and 162 544 controls) (26), and the UKBB GWAS for spontaneous miscarriage, accessed through the UK Biobank Pan-Ancestry Summary statistics (a multi-ancestry analysis of 7221 phenotypes spanning 16 119 GWAS) (27) (Supplementary Table S3(20)).

Statistical Analyses

Linear and logistic regression models were generated in R to assess the associations of pPS with continuous and discrete individual-level phenotypes, respectively, in MGBB. All models included age, genotype batch, and 10 genetic principal components as covariates. When performing our primary analyses, which included patients of all ancestries and sexes, additional covariates were included for sex and population. Sensitivity analyses were performed restricting to just females, as well as only individuals of European genetic ancestry, given that the majority of SNVs in the pPS were identified in study populations of predominantly European genetic ancestry. Assessment of associations with clinical traits that were included as inputs for the clustering analyses were considered validation analyses, and P less than .05 was used for statistical significance. For analyses of novel outcomes not included in the clustering, we determined significance to be a Bonferroni-adjusted P value of (P < .05/4 clusters/3 tests for individual-level pPS and P < .05/4 clusters/4 tests for GWAS-pPS).

Results

Clustering Suggests Four Dominant Pathways Driving Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

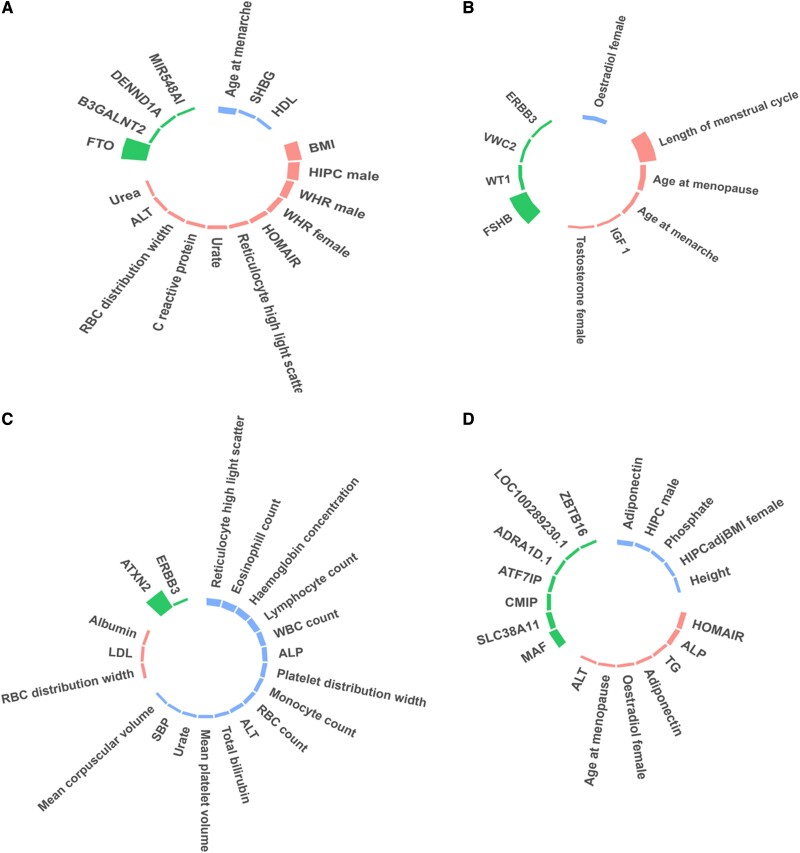

Using the variant-trait matrix (60 SNVs × 49 traits) as an input, the bNMF algorithm was run for 50 iterations (see Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 (20)). Across the 50 iterations, bNMF converged to K = 3 (30%) and K = 4 (70%), indicating that the set of 4 clusters was the optimal solution (Fig. 1). As bNMF clusters both variants and traits, the top-weighted loci and traits can be used to help define the underlying mechanisms in each cluster (Supplementary Tables S4 and S5 (20); Fig. 1). Three of the 4 clusters appeared to represent readily recognizable physiological mechanisms:

Figure 1.

Clustering analysis revealed 4 distinct genetic clusters for polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Cluster 1 related to obesity/insulin resistance traits with the top weighted loci at the FTO locus (Fig. 1A). Genetic variants in cluster 2 were linked to hormonal and menstrual cycle changes with the top loci including FSHB and WT1 (Fig. 1B). Genetic variants in cluster 3 were associated with inflammatory and blood markers, with top loci in close proximity to ATXN2/SH2B3 (Fig. 1C). Cluster 4 was linked to homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), adiponectin, and alkaline phosphatase levels with top loci near MAF and SLC38A11 (Fig. 1D). The height of the bars indicates the strength of the associations. Traits showed in pink and blue were positively and negatively correlated with the genetic loci, respectively.

Cluster 1—obesity/insulin resistance: The most strongly weighted variants for cluster 1 related to increased BMI, hip circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), and decreased age of menarche (Fig. 1A). The locus that clustered most strongly into cluster 1 included the well-known obesity and diabetes locus, FTO (28);

Cluster 2—hormonal/menstrual cycle changes: Cluster 2 appeared to relate to menstrual and hormonal changes: top traits of this cluster include increased length of the menstrual cycle, age at menopause and menarche, and testosterone levels in females, as well as reduced estradiol levels in females (Fig. 1B). The top locus in this cluster was FSHβ, the gene that codes for follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), which is one of the two gonadotropins that are responsible for pituitary control of the reproductive system. The second locus of cluster 2 was found in the region of the Wilms tumor suppressor gene (WT1), a gene that has been shown to regulate the expression of antimüllerian hormone receptor 2 (AMHR2), a gene important for urogenital development (29);

Cluster 3—blood markers/inflammation: In cluster 3, the top-weighted traits included increased red blood cell distribution, low-density lipoprotein, and albumin; decreased reticulocyte, eosinophil, lymphocyte, and white cell count, as well as decreased hemoglobin concentration (Fig. 1C). Notably, the most strongly weighted loci in cluster 3 contains the genes ATXN2 and SH2B3, with the latter linked to T-cell proliferation and the inflammatory cascade (30, 31);

Cluster 4—metabolic/changes: In the fourth cluster, the top-weighted traits included increased HOMA-IR, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), triglycerides, and estradiol levels, along with reduced hip circumference in males (Fig. 1D). This cluster was independent of the FTO locus, and the top loci included MAF, SLC38A11, ADRA1D, and ZBTB16. Relevant to metabolism, the SLC38A11 gene encodes for the solute carrier family members implicated in metabolic homeostasis (32, 33).

Cluster Partitioned Polygenic Scores Are Associated With Distinct Clinical Traits in Mass General Biobank Participants

To validate the relationship of the genetic clusters to their top-weighted traits, we tested the associations of the cluster-specific pPS with individual-level clinical traits in MGBB (N = 62 252) (Supplementary Table S6 (20)).

Cluster 1 (obesity/insulin resistance) pPS was confirmed in MGBB males and females to be associated with top-weighted traits: increased BMI (P = 6.6 × 10−29), alanine transaminase (ALT) (P = .001), and reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (P = .002). Additionally, cluster 1 pPS was associated with increased glycated hemoglobin A1c (P = 1.5 × 10−8), random glucose levels (P = 6.9 ×10−6), white blood cell count (WBC) (P = 2.7 ×10−6), and systolic blood pressure (P = .004). In analyses restricted to only female participants, these same traits were also similarly associated with cluster 1 pPS, as well as the younger age of menarche in an analysis restricted to individuals of European genetic ancestry (P = .04).

Cluster 2's (hormonal/menstrual cycle changes) top-weighted cluster traits, as noted earlier, were largely related to reproductive hormones and menstruation. Consistent with this, the cluster 2 pPS was associated in MGBB female participants with increased age of menarche (P = 1.5 × 10−4).

Cluster 3 pPS (blood markers/inflammation) had notable associations in males and females with decreased lymphocyte count (P = 1.6 × 10−4), WBC count (P = 2.7 × 10−3), hemoglobin (P = .03), mean corpuscular volume (P = .02), and mean platelet volume (MPV) (P = 3.1 × 10−5). These associations were also replicated in female-only analyses, with the exceptions of lymphocyte count and WBC. Of note, the pPS was significantly associated with WBC in the female-only analysis restricted to only European genetic ancestry (P = .002).

Cluster 4 (metabolic changes) pPS in MGBB participants of both sexes also replicated top-weighted trait findings of increased ALT (0.03) and ALP (P = 0.007), as well as increased age at menopause (P = .01) in females.

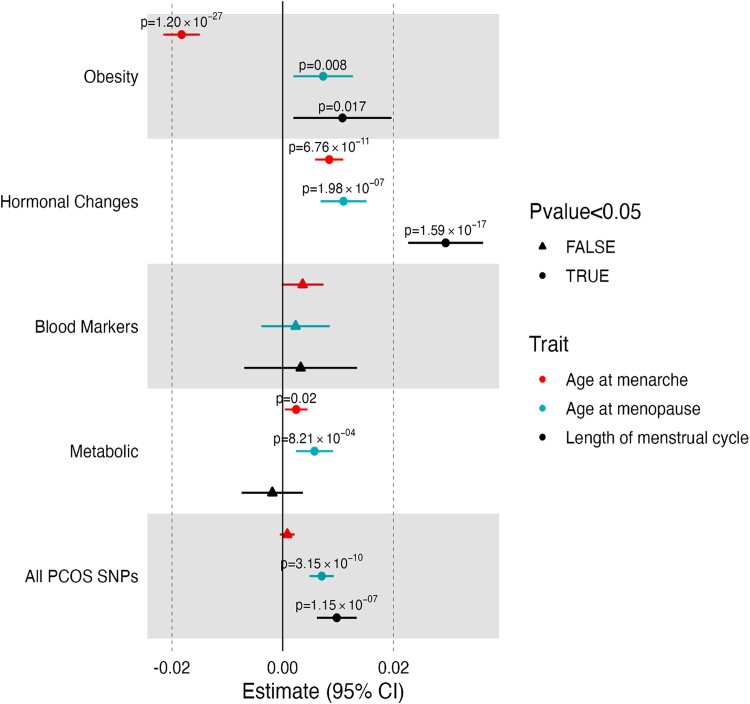

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Genetic Clusters Are Differentially Associated With Menstruation Characteristics

To better understand how the PCOS genetic clusters related to menstrual reproductive traits available in the UKBB, we analyzed GWAS-pPS (see “Materials and Methods”). These traits, which were included in the clustering themselves or captured by another highly correlated trait, were chosen for further investigation with GWAS-pPS, given their importance for appreciating the physiological consequences of the clusters and the more limited data available in MGBB. Considerable differences were observed across clusters (Fig. 2; Supplementary Table S7A (20)). Cluster 1 pPS was associated with younger age of menarche (P = 1.20 × 10−27). In contrast, all other clusters were associated with older age of menarche, with the largest effect seen for cluster 2, which was replicated in MGBB females, as noted previously. These results highlight the utility of the genetic clustering since the analysis including all SNVs masks the opposite directional effect of cluster 1. Cluster 2 pPS was most significantly associated with increased menstrual cycle length (P = 1.59 × 10−17). pPS of 3 clusters (cluster 1, 2, and 4) were associated with older age at menopause, with the largest effect noted for cluster 2.

Figure 2.

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) cluster genome-wide association studies (GWAS) partitioned polygenic score (pPS) associations with reproductive clinical phenotypes. The associations of reproductive traits with each cluster using GWAS pPS, as well as for the composite 17 single-nucleotide variations across the 4 clusters. The reproductive traits were all included in the clustering; therefore, the associations are not independent outcomes and are displayed for the purpose of characterization of the clusters.

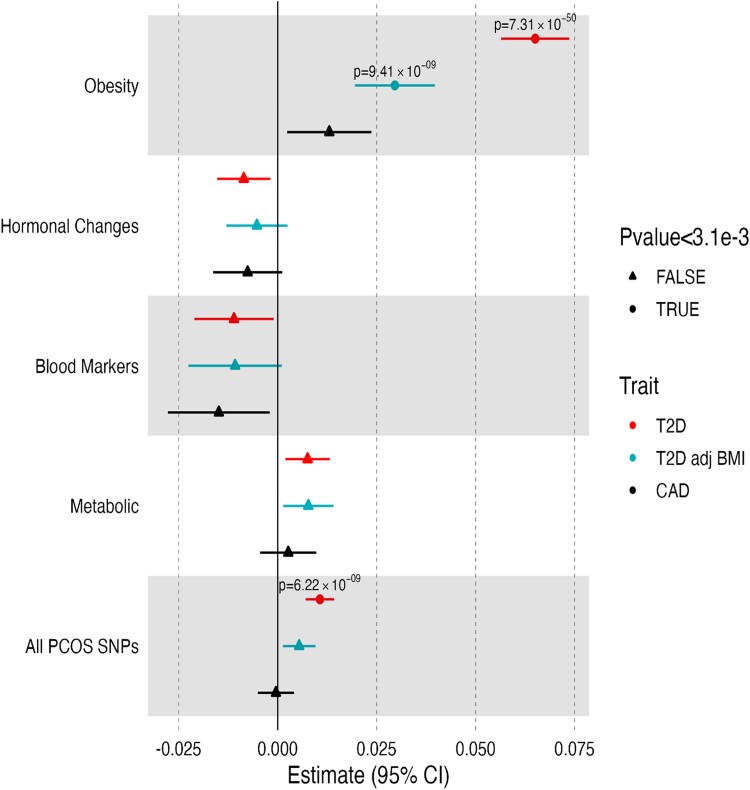

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Genetic Clusters Are Differentially Associated With Disease Outcomes

Finally, we examined the association of the genetic variants with clinical outcomes not included in the clustering, using both GWAS-pPS and individual-level data pPS in GWAS (see Supplementary Table S7 (20)), and MGBB (Supplementary Tables S8 (20), and Fig. 3). Cluster 1 GWAS-pPS was associated with increased risk for both T2D (odds ratio [OR] 1.07; P = 7.31 × 10−50) and T2D adjusted for BMI (OR 1.03; P = 9.41 × 10−9). The association of cluster 1 with T2D was replicated in all MGBB participants (OR 1.09, P = 2.7 × 10−7) and in females only (OR 1.11, 4.8 × 10−5) (Supplementary Table S8 (20)). No statistically significant associations were observed with metabolic outcomes for clusters 2 to 4.

Figure 3.

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) cluster genome-wide association studies (GWAS) partitioned polygenic score (pPS) associations with cardiometabolic clinical outcomes. The associations of cardiometabolic outcomes with each cluster using GWAS pPS, as well as for the composite 17 single-nucleotide variations across the 4 clusters. The cardiometabolic outcomes were not included in the clustering, and, thus, associations represent independent findings.

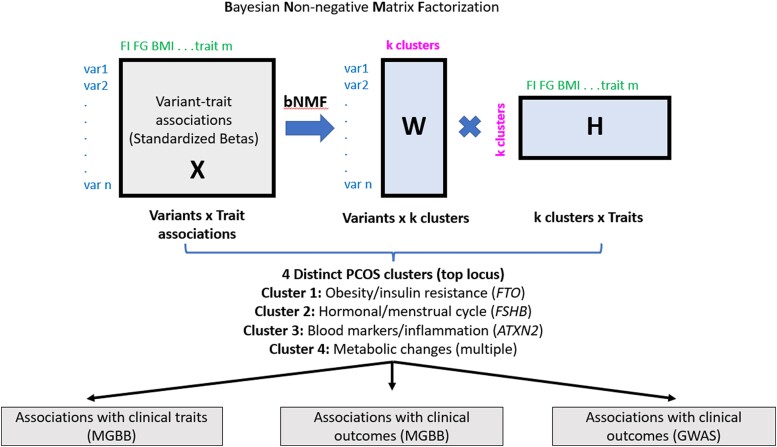

Discussion

PCOS is a phenotypically and genetically heterogeneous disease, and the distinct mechanisms underlying the syndrome remain unknown. In this study, we hypothesized that the genetic loci associated with PCOS aggregate in clusters and thus could inform distinct biological pathways that underlie the syndrome. By performing the most comprehensive assessment of PCOS loci clustering to date, including variant-trait associations for 60 PCOS genetic variants and 49 GWAS traits in publicly available databases, we identified 4 distinct clusters of PCOS variants with readily interpretable links to disease pathophysiology: obesity/insulin resistance, hormonal/menstrual cycle changes, blood markers/inflammation, and metabolic changes independent of obesity. Additionally, by using individual-level data from the MGBB, we validated associations between the genetic clusters and clinical traits (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Discovery pipeline of the genetic clusters and their associations with clinical traits and outcomes in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). By performing a comprehensive assessment of PCOS loci clustering, we identified 4 distinct clusters of PCOS variants, with readily interpretable links to disease pathophysiology: obesity/insulin resistance, hormonal/menstrual cycle changes, blood markers/inflammation, and metabolic changes independent of obesity. Individual-level PCOS cluster partitioned polygenic score (pPS) associations with traits and outcomes in Mass General Brigham Biobank (MGBB) as well as PCOS cluster genome-wide association studies (GWAS) pPS associations with clinical outcomes in GWAS were performed.

Even though multiple genetic loci have been linked to PCOS through GWAS in the past, understanding the biological pathways causing this complex syndrome is crucial for informing clinical management and developing novel targeted therapies. Despite advances in understanding the genomic architecture of the disease (7-12) and mendelian randomization analyses that have attempted to link genetic loci to the phenotypic variability of PCOS (12-14), the disease pathogenesis remains largely unknown. Polygenic risk scores can be valuable tools for the prediction of complex traits, and such tools can be used by providers for early diagnosis and intervention. Those models depend on the availability of large GWAS studies, and thus far, PCOS GWAS have not reached such thresholds. Given these limitations, we undertook a clustering methodology with generation of polygenic risk scores from specific clusters of the broader PCOS phenotype with the goal of detecting the pathways that underlie each cluster.

The first PCOS cluster was found to be associated with obesity and body fat distribution, with the FTO locus most strongly associated. FTO encodes for the fat mass and obesity–associated gene and has been established as an obesity and T2D locus in humans (28, 34, 35). Importantly, cluster 1 pPS was linked to increased BMI, glycated hemoglobin A1c, and fasting glucose levels within the individual-level MGBB, validating our findings. Even though both T2D and obesity are not part of PCOS diagnostic criteria, PCOS has been linked to cardiometabolic long-term outcomes, especially in the setting of obesity (36). Obesity has been considered a risk factor for the development of PCOS and can exacerbate both the hormonal and clinical features of PCOS (37). This is also supported by prior mendelian randomization studies that have shown that genetically predicted elevated BMI increases the risk for PCOS (12, 13). Insulin resistance is also common in individuals with PCOS, with most women undergoing an oral glucose tolerance test at the time of diagnosis (38). In this study, cluster 1 GWAS-pPS was associated with increased risk for T2D. Importantly, this association remained even for T2D adjusting for BMI, suggesting that the genetic background of the cluster itself, and not the effect of the genetics on BMI, increases the T2D risk in PCOS. The association with T2D was also replicated in the MGBB in all participants and in females only, while the effect on males only was much smaller. This observation is in line with a recent magnetic resonance analysis based on a large GWAS examining genetic determinants of testosterone levels in UKBB participants (39). The analysis demonstrated that higher testosterone levels in women, but not in men, increase the risk of PCOS and T2D (39). These data, in combination with our observations, suggest a sex-specific effect of the genetic variants affecting the development of T2D in individuals with a genetic predisposition to PCOS.

The pPS of cluster 2 (“hormonal/menstrual cycle changes”) had significant associations with increased age of menopause, menarche, and length of menstrual cycles in the GWAS-pPS analyses, with replication of the menarche association in MGBB. These traits were used in our clustering analysis, so these results are confirmatory but still provide potentially important insight into the pathophysiology of PCOS. Our study shows that while genetic predisposition to obesity/insulin resistance (ie, cluster 1) was linked to early menarche, genetic predisposition to hormonal/menstrual cycle changes (ie, cluster 2) was linked to delayed menarche. While the latter observation should be interpreted with caution given the traits selected for this analysis, it is known that higher BMI and obesity are associated with earlier pubertal timing in girls (40), and our findings suggest there is a genetic basis for this association. Interestingly, in contrast to different directional associations between the cluster pPS and menarche, all cluster pPSs were associated with later menopause. This is in line with prior epidemiologic studies that have linked PCOS with a delay in menopausal timing (41). In addition, while it is known that early pubarche and adrenarche are associated with an increased prevalence of PCOS later in life (42), no such an association has been established for menarche.

Cluster 3 included genetic variants associated with inflammatory and blood markers, such as reduced WBC count, hemoglobin, mean corpuscular volume, and MPV, that were replicated in the MGBB individual-level analysis. Interestingly, molecular markers of oxidative stress and inflammation are highly correlated with circulating androgens but not with obesity (43). In our analysis, the strongest association was observed in the locus that was in close proximity to the genes ATXN2 and SH2B3 (among others). ATXN2 (ataxin-2) has been associated with spinocerebellar ataxia (a disease characterized by neuroinflammation), and SH2B3 (SH2B adaptor protein 3) has been linked to myeloproliferative syndrome. The protein encoded by SH2B3 is a regulator of growth factor and cytokine receptor signaling and mediates the interaction between the extracellular receptors and the intracellular signaling pathways of T and B cells (30, 31). Interestingly, the expression quantitative trait loci for the locus with the strongest association are linked to the gene encoding aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 (ALDH2), which is associated with chronic inflammation and autophagy (44). Currently, the causal gene mediating the association of this locus with PCOS is unknown, as is the basis for how changes in blood markers relate to PCOS pathophysiology, but both are fascinating directions for future research.

Finally, our analysis identified a fourth genetic cluster that was characterized by elevated HOMA-IR and ALP, and decreased adiponectin. Cluster 4 pPS were found to be associated with high ALP and ALT levels in the MGBB replication study. Women with PCOS demonstrate insulin resistance and high normal ALP levels (45) and are predisposed to developing hepatic steatosis compared to controls (46). While no distinct top locus was identified, a combination of top loci included MAF, SLC38A11, ADRA1D, and ZBTB16. Proteins in the MAF family are transcription factors and can be subgrouped into large (L-MAFs) and small (S-MAFs), with small MAFs playing a fundamental role in insulin resistance, β-cell function, and diabetes (47, 48) as well as cholestatic liver injury (49). The SLC38A11 locus has been linked to metabolic homeostasis (32, 33). Importantly, cluster 4 was independent of the FTO locus and was not associated with increased BMI in the MGBB analysis or T2D in our GWAS and MGBB analyses, suggesting that the mechanism of insulin resistance is independent of obesity. Further studies are required to understand the differential effects of the 2 genetic clusters on the metabolic alterations associated with PCOS.

This study has several strengths. This is the first comprehensive and systematic genetic variant-trait clustering analysis of PCOS, and we were able to identify distinct putative biological pathways associated with the disease. The use of summary statistics from large GWAS studies, as well as individual-level data from the MGBB, allowed for the identification and replication of significant associations between the PCOS cluster pPS and clinical phenotypes. Most important, in contrast to prior clustering studies that used both biochemical and genotyping data, we used an unbiased genotype-first approach that led to the identification of 4 distinct clusters for PCOS. This information can be essential for approaching patients with PCOS in future clinical practice settings for several reasons. First, it can facilitate the identification of individuals at risk for PCOS and specific PCOS subtypes early on during the diagnostic process. In addition, our results support individualized clinical approaches that depend on patients’ genetic architecture. For example, identifying patients with genetic risk scores for cluster 1 (ie, “obesity/insulin resistance”) can direct the clinician's management plan with an emphasis on weight management and prevention of T2D development. In contrast, individuals with genetic variants clustering in the “metabolic” subcohort of our study will be at increased risk for the development of metabolic syndrome even in the absence of obesity, and thus the clinician's efforts will focus on the evaluation and management of insulin resistance, rather than weight management and prevention. Future studies will allow further detailed characterization of PCOS subcohorts and provide specific guidelines for the evaluation and management of patients within specific genetic backgrounds, directed by such genetic clustering approaches.

The primary limitation of this analysis is that, in contrast to many other complex diseases, the characterization of the underlying genetic architecture of PCOS is still limited by the size and number of available PCOS GWAS. As the number and power of available PCOS GWAS increases, we will be able to further advance our understanding of PCOS subtypes and their unique pathophysiology based on genetic clustering. Currently, several of our clusters appear to be primarily driven by one heavily weighted variant. More powerful PCOS GWAS would allow for more variants to be included in the analysis and therefore a larger number of variants contributing to each cluster. We also acknowledge that our results may not apply to non-European populations, due to our use of European-based summary statistics. As PCOS GWAS become more diverse, this will allow for insight into the conservation of mechanistic pathways across subpopulations. Regarding the individual-level analyses, PCOS can be underdiagnosed in the clinical setting, which may have contributed to the low number of cases in MGBB. This makes it even more difficult to pick up significant associations with the cluster pPSs when compared to more well-recorded diseases such as T2D and CAD.

In conclusion, we have identified physiologic pathways and groups of genetic variants associated with PCOS, including newly described clusters of variants that are associated with obesity/insulin resistance, menstrual/hormonal changes, inflammatory/blood markers, and metabolic abnormalities in women with PCOS. Our findings offer a genetic and physiologically supported basis for the clinical heterogeneity observed among women with PCOS. Further characterization of these genetic subgroups of PCOS may help elucidate the etiology of this condition and identify important clinical subsets of patients best suited for particular management strategies and interventions.

Abbreviations

- ALP

alkaline phosphatase

- ALT

alanine transaminase

- BMI

body mass index

- bNMF

Bayesian nonnegative matrix factorization

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- FSH

follicle-stimulating hormone

- GWAS

genome-wide association studies

- HA

hyperandrogenism

- HOMA-IR

homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance

- LH

luteinizing hormone

- MGBB

Mass General Brigham Biobank

- MPV

mean platelet volume

- OD

ovulatory dysfunction

- OR

odds ratio

- PCOM

polycystic ovarian morphology

- PCOS

polycystic ovary syndrome

- pPS

partitioned polygenic scores

- SNV

single-nucleotide variation

- T2D

type 2 diabetes

- UKBB

UK Biobank

- WBC

white blood cell count

Contributor Information

Maria I Stamou, Reproductive Endocrine Unit, Endocrine Division, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA 02114, USA.

Kirk T Smith, Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA 02142, USA; Diabetes Unit, Endocrine Division, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA 02114, USA; Center for Genomic Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA 02114, USA.

Hyunkyung Kim, Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA 02142, USA; Diabetes Unit, Endocrine Division, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA 02114, USA; Center for Genomic Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA 02114, USA.

Ravikumar Balasubramanian, Reproductive Endocrine Unit, Endocrine Division, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA 02114, USA.

Kathryn J Gray, Center for Genomic Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA 02114, USA; Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

Miriam S Udler, Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA 02142, USA; Diabetes Unit, Endocrine Division, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA 02114, USA; Center for Genomic Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA 02114, USA.

Funding

M.I.S. reports funding from the NIH/NICHD (F32HD108873-01); R.B. reports funding from NIH/NICHD (R01 HD096324, NIH/NIDCR R01 DE031452, and NIH/NICHD P50 HD 104224); K.J.G. reports funding from NIH/NHLBI (grants K08 HL146963 and R03 HL162756); and M.S.U. reports funding from NIH/NIDDK (K23DK114551).

Disclosures

K.J.G. reports consulting for BillionToOne, Aetion, and Roche outside the scope of the submitted work. The other authors have nothing to declare.

Data Availability

Original data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories listed in “References.”

References

- 1. Knochenhauer ES, Key TJ, Kahsar-Miller M, Waggoner W, Boots LR, Azziz R. Prevalence of the polycystic ovary syndrome in unselected black and white women of the southeastern United States: a prospective study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(9):3078‐3082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Welt CK. Genetics of polycystic ovary syndrome: what is new? Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2021;50(1):71‐82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hoeger KM, Dokras A, Piltonen T. Update on PCOS: consequences, challenges, and guiding treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(3):e1071‐e1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rubin KH, Glintborg D, Nybo M, Abrahamsen B, Andersen M. Development and risk factors of type 2 diabetes in a nationwide population of women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(10):3848‐3857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gambineri A, Pelusi C, Vicennati V, Pagotto U, Pasquali R. Obesity and the polycystic ovary syndrome. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26(7):883‐896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ding DC, Tsai I-J, Wang J-H, Lin S-Z, Sung F-C. Coronary artery disease risk in young women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Oncotarget. 2018;9(9):8756‐8764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen ZJ, Zhao H, He L, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies susceptibility loci for polycystic ovary syndrome on chromosome 2p16.3, 2p21 and 9q33.3. Nat Genet. 2011;43(1):55‐59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shi Y, Zhao H, Shi Y, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies eight new risk loci for polycystic ovary syndrome. Nat Genet. 2012;44(9):1020‐1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hwang JY, Lee E-J, Jin Go M, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies GYS2 as a novel genetic factor for polycystic ovary syndrome through obesity-related condition. J Hum Genet. 2012;57(10):660‐664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lee H, Oh J-Y, Sung Y-A, et al. Genome-wide association study identified new susceptibility loci for polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(3):723‐731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hayes MG, Urbanek M, Ehrmann DA, et al. Genome-wide association of polycystic ovary syndrome implicates alterations in gonadotropin secretion in European ancestry populations. Nat Commun. 2015;6(1):7502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Day FR, Hinds DA, Tung JY, et al. Causal mechanisms and balancing selection inferred from genetic associations with polycystic ovary syndrome. Nat Commun. 2015;6(1):8464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Day F, Karaderi T, Jones MR, et al. Large-scale genome-wide meta-analysis of polycystic ovary syndrome suggests shared genetic architecture for different diagnosis criteria. PLoS Genet. 2018;14(12):e1007813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dapas M, Lin FTJ, Nadkarni GN, et al. Distinct subtypes of polycystic ovary syndrome with novel genetic associations: an unsupervised, phenotypic clustering analysis. PLoS Med. 2020;17(6):e1003132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Udler MS, Kim J, von Grotthuss M, et al. Type 2 diabetes genetic loci informed by multi-trait associations point to disease mechanisms and subtypes: A soft clustering analysis. PLoS Med. 2018;15(9):e1002654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Powe CE, Udler MS, Hsu S, et al. Genetic loci and physiologic pathways involved in gestational diabetes Mellitus implicated through clustering. Diabetes. 2021;70(1):268‐281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Merino J, Dashti HS, Sarnowski C, et al. Genetic analysis of dietary intake identifies new loci and functional links with metabolic traits. Nat Hum Behav. 2022;6(1):155‐163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vaura F, Kim H, Udler MS, Salomaa V, Lahti L, Niiranen T. Multi-Trait genetic analysis reveals clinically interpretable hypertension subtypes. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2022;15(4):e003583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Agrawal S, Wang M, Klarqvist MDR, et al. Inherited basis of visceral, abdominal subcutaneous and gluteofemoral fat depots. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):3771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stamou MS. Kirk; Kim, Hyunkyung; Balasubramanian, Ravikumar; Gray, Kathryn; Udler, Miriam (2023). Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome Physiologic Pathways Implicated Through Clustering of Genetic Loci. Maria I. Stamou*, Kirk T. Smith*, Hyunkyung Kim*, Ravikumar Balasubramanian, Kathryn J. Gray, Miriam Udler.. figshare. Dataset. 10.6084/m9.figshare.23613534.v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21. Accelerating Medicines Partnership . Common Metabolic Diseases Knowledge Portal. Accessed March 19, 2021. https://hugeamp.org/.

- 22. Neale Lab . GWAS analysis of UK Biobank data, 2018. Accessed July 18, 2021. http://www.nealelab.is/uk-biobank.

- 23. Karlson EW, Boutin N, Hoffnagle A, et al. Building the partners HealthCare biobank at partners personalized medicine: informed consent, return of research results, recruitment lessons and operational considerations. J Pers Med. 2016;6(1):2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Udler MS, McCarthy MI, Florez JC, Mahajan A. Genetic risk scores for diabetes diagnosis and precision medicine. Endocr Rev. 2019;40(6):1500‐1520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mahajan A, Taliun D, Thurner M, et al. Fine-mapping type 2 diabetes loci to single-variant resolution using high-density imputation and islet-specific epigenome maps. Nat Genet. 2018;50(11):1505‐1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. van der Harst P, Verweij N. Identification of 64 novel genetic loci provides an expanded view on the genetic architecture of coronary artery disease. Circ Res. 2018;122(3):433‐443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.UK Biobank Pan-Ancestry Summary Statistics. Accessed November 15, 2023. https://registry.opendata.aws/broad-pan-ukb.

- 28. Claussnitzer M, et al. FTO Obesity variant circuitry and adipocyte browning in humans. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(10):895‐907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Klattig J, Sierig R, Kruspe D, Besenbeck B, Englert C. Wilms’ tumor protein Wt1 is an activator of the anti-mullerian hormone receptor gene amhr2. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(12):4355‐4364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lasho TL, Pardanani A, Tefferi A. LNK Mutations in JAK2 mutation-negative erythrocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(12):1189‐1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Oh ST, Simonds EF, Jones C, et al. Novel mutations in the inhibitory adaptor protein LNK drive JAK-STAT signaling in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2010;116(6):988‐992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Aggarwal T, Patil S, Ceder M, Hayder M, Fredriksson R. Knockdown of SLC38 transporter ortholog—CG13743 reveals a metabolic relevance in Drosophila. Front Physiol. 2019;10:1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Al-Eitan LN, Almomani B, Nassar A, Elsaqa B, Saadeh N. Metformin pharmacogenetics: effects of SLC22A1, SLC22A2, and SLC22A3 polymorphisms on glycemic control and HbA1c levels. J Pers Med. 2019;9(1):17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Scott LJ, Mohlke KL, Bonnycastle LL, et al. A genome-wide association study of type 2 diabetes in Finns detects multiple susceptibility variants. Science. 2007;316(5829):1341‐1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Church C, Moir L, McMurray F, et al. Overexpression of Fto leads to increased food intake and results in obesity. Nat Genet. 2010;42(12):1086‐1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Guan C, Zahid S, Minhas AS, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome: a “risk-enhancing” factor for cardiovascular disease. Fertil Steril. 2022;117(5):924‐935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lim SS, Norman RJ, Davies MJ, Moran LJ. The effect of obesity on polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2013;14(2):95‐109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dunaif A, Segal KR, Futterweit W, Dobrjansky A. Profound peripheral insulin resistance, independent of obesity, in polycystic ovary syndrome. Diabetes. 1989;38(9):1165‐1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ruth KS, Day FR, Tyrrell J, et al. Using human genetics to understand the disease impacts of testosterone in men and women. Nat Med. 2020;26(2):252‐258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li W, Liu Q, Deng X, Chen Y, Liu S, Story M. Association between obesity and puberty timing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(10):1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Forslund M, Landin-Wilhelmsen K, Schmidt J, Brännström M, Trimpou P, Dahlgren E. Higher menopausal age but no differences in parity in women with polycystic ovary syndrome compared with controls. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2019;98(3):320‐326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dumesic DA, Oberfield SE, Stener-Victorin E, Marshall JC, Laven JS, Legro RS. Scientific statement on the diagnostic criteria, epidemiology, pathophysiology, and molecular genetics of polycystic ovary syndrome. Endocr Rev. 2015;36(5):487‐525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gonzalez F. Inflammation in polycystic ovary syndrome: underpinning of insulin resistance and ovarian dysfunction. Steroids. 2012;77(4):300‐305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Li SY, Gilbert SAB, Li Q, Ren J. Aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 (ALDH2) ameliorates chronic alcohol ingestion-induced myocardial insulin resistance and endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;47(2):247‐255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Markou A, Androulakis II, Mourmouris C, et al. Hepatic steatosis in young lean insulin resistant women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(4):1220‐1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Petta S, Ciresi A, Bianco J, et al. Insulin resistance and hyperandrogenism drive steatosis and fibrosis risk in young females with PCOS. PLoS One. 2017;12(11):e0186136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Katsuoka F, Yamamoto M. Small maf proteins (MafF, MafG, MafK): history, structure and function. Gene. 2016;586(2):197‐205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Katsuoka F, Motohashi H, Engel JD, Yamamoto M. Nrf2 transcriptionally activates the mafG gene through an antioxidant response element. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(6):4483‐4490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Liu T, Yang H, Fan W, et al. Mechanisms of MAFG dysregulation in cholestatic liver injury and development of liver cancer. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(2):557‐571 e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Stamou MS. Kirk; Kim, Hyunkyung; Balasubramanian, Ravikumar; Gray, Kathryn; Udler, Miriam (2023). Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome Physiologic Pathways Implicated Through Clustering of Genetic Loci. Maria I. Stamou*, Kirk T. Smith*, Hyunkyung Kim*, Ravikumar Balasubramanian, Kathryn J. Gray, Miriam Udler.. figshare. Dataset. 10.6084/m9.figshare.23613534.v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Data Availability Statement

Original data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories listed in “References.”