Summary

Background

Psychiatric disorders have been associated with higher risk for future dementia. Understanding how pre-dementia psychiatric disorders (PDPD) relate to established dementia genetic risks has implications for dementia prevention.

Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, we investigated the relationships between polygenic risk scores for Alzheimer's disease (AD PRS), PDPD, alcohol use disorder (AUD), and subsequent dementia in the UK Biobank (UKB) and tested whether the relationships are consistent with different causal models.

Findings

Among 502,408 participants, 9352 had dementia. As expected, AD PRS was associated with greater risk for dementia (odds ratio (OR) 1.62, 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.59–1.65). A total of 94,237 participants had PDPD, of whom 2.6% (n = 2519) developed subsequent dementia, compared to 1.7% (n = 6833) of 407,871 participants without PDPD. Accordingly, PDPD were associated with 73% greater risk of incident dementia (OR 1.73, 1.65–1.83). Among dementia subtypes, the risk increase was 1.5-fold for AD (n = 3365) (OR 1.46, 1.34–1.59) and 2-fold for vascular dementia (VaD, n = 1823) (OR 2.08, 1.87–2.32). Our data indicated that PDPD were neither a dementia prodrome nor a mediator for AD PRS. Shared factors for both PDPD and dementia likely substantially account for the observed association, while a causal role of PDPD in dementia could not be excluded. AUD could be one of the shared causes for PDPD and dementia.

Interpretation

Psychiatric diagnoses were associated with subsequent dementia in UKB participants, and the association is orthogonal to established dementia genetic risks. Investigating shared causes for psychiatric disorders and dementia would shed light on this dementia pathway.

Funding

US NIH (K08AG054727).

Keywords: Dementia, Psychiatric disorders, Polygenic risks for dementia, Alcohol use disorder, Causal modelling

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Previous research, including several large population-based cohort studies, has found that psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia and depression, were associated with a higher risk for future dementia. However, little is known about how psychiatric disorders relate to known genetic risk factors for dementia. In this retrospective cohort study, we seek to investigate whether psychiatric disorders signify prodromal dementia, mediate genetic risks for dementia, are independently causal for dementia, or have shared causes with dementia.

Added value of this study

In the present study, we not only replicated the previously observed association between psychiatric disorders and subsequent dementia in a large longitudinal population-based dataset—the UK Biobank, but also investigated the relationship between psychiatric disorders and known genetic risks of dementia.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our results demonstrate that the relationship between psychiatric disorders and subsequent dementia is independent from established dementia genetic risks. Causal modelling showed that pre-dementia psychiatric disorders unlikely represent prodromal dementia, nor do they mediate established genetic risks for dementia. Shared risk factors, such as alcohol use disorders, may contribute to both psychiatric disorders and dementia, thus account for the association between them.

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) and Alzheimer's disease related dementias (ADRD) describe a group of dementia syndromes with both distinguishing and overlapping clinical and pathological features.1 Genetic factors account for about 60–70% of risk2 and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) identified 75 independent genomic risk loci,3 which capture around 50% of heritability.4 While each common variant has a small effect on risk by itself, variants can be aggregated into polygenic risk scores (PRS).5,6 We and others have shown that AD PRS capture a relevant share of total heritability and may be used to identify at-risk individuals.6,7 Since the majority of patients with dementia have mixed neuropathology,8, 9, 10 the joint investigation of all-cause dementia (e.g. AD/ADRD) constitutes a powerful approach. For instance, recent GWAS using dementia proxy cases defined by self-reported parental history of dementia identified most of the previously implicated loci using clinically defined AD cases and controls.4

In addition to genetic risks, environmental factors such as excessive alcohol consumption and smoking are also thought to contribute to dementia risk,11 while healthy lifestyle was associated with lower dementia risk in individuals with higher genetic risk for dementia.12 Heavy alcohol use has been repeatedly found to have detrimental effects on brain structures and function,13 and smoking was associated with lower brain grey matter volumes.14 Psychiatric disorders have been associated with multifold increase of dementia risk in several recent large population-based studies15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 (eTable 1). Depression was associated with more than 50% higher risk and psychotic disorders exhibited even greater risk for future dementia. Since dementia itself is often accompanied by psychiatric symptoms,24 these studies addressed possible reverse causation by excluding psychiatric disorders with onset shortly before or after dementia diagnoses. Moreover, among individuals with schizophrenia, the risk increase was particularly strong among the younger age group,15,18 suggesting alternative mechanisms for dementia in this group. Notably, the associations were consistent across studies conducted in different countries with subjects of different ancestries, including European,15,17,21 multiethnic,18, 19, 20,22,23 and East Asian16 populations. However, unlike the association between genetic risks and dementia, the directionality of the association between psychiatric disorders and dementia remains unclear. Dementia pathology may lead to neuropsychiatric symptoms during the prodromal and mild stages of dementia, and patients with such symptoms without obvious cognitive impairment often receive psychiatric diagnoses (i.e. reverse causation).25 It is also conceivable that psychiatric disorders and dementia have shared risk factors, such as genetic risks. However, the lack of genetic correlation between psychiatric disorders and AD26,27 suggests that the molecular mechanisms underlying increased dementia risk after having a psychiatric diagnosis are distinct from the genetics of psychiatric disorders or AD on their own.

In this study, pre-dementia psychiatric disorders (PDPD) are defined as psychiatric diagnoses either without any dementia diagnoses or were documented before any dementia diagnoses. Our rationales for combining multiple psychiatric disorders into the single variable PDPD are: (1) large proportion of significant genetic correlations between the phenotypically distinct psychiatric disorders suggests overlapping genetic architectures27, 28, 29; (2) multiple psychiatric phenotypes have been associated with greater dementia risk (eTable 1).

The primary aim of this study was to elucidate the relationship between PDPD and subsequent dementia in participants of the UK Biobank (UKB). Utilising established genetic risks for dementia, we further applied causal modelling30,31 to evaluate the following hypotheses: (a) PDPD signify mild behavioural impairment (MBI)25; (b) PDPD mediate the effect of genetic risks on dementia; (c) PDPD are risk factors independent from the known genetic dementia risk factors; and/or (d) other shared causes account for the association between PDPD and dementia. Understanding how psychiatric conditions relate to the dementia pathway as defined by dementia genetic risks can inform strategies for dementia prevention and intervention.

Methods

Participants and ethics

The UKB is a prospective cohort study of over 500,000 participants enrolled between 2006 and 2010 at an age between 37 and 69 years in the United Kingdom.32 This age range was selected to study the risk of age-related diseases based on the complex interplay of many risk factors, including genetic susceptibility, lifestyle, and environment. All participants provided informed consent at the baseline assessment, which included permission for access to their past and future medical records. The UK Biobank is approved from the North West Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee as a Research Tissue Bank and researchers do not require separate ethical clearance. The current study was conducted under the approved application number 84323.

Diagnoses of pre-dementia psychiatric disorders and dementia

Diagnosis codes and year of diagnosis were obtained from the data category 1712 “First Occurrences”, which documented the earliest date of a diagnosis as an international classification of diseases 10th revision (ICD-10) code. The diagnoses were aggregated from self-report, hospital, primary care or death record data. The dataset was obtained in May 2022.

The primary outcome is dementia diagnoses, which included AD, vascular dementia (VaD), dementia classified elsewhere, and unspecified dementia defined as ICD-10 codes F00, F01, F02, F03, F04, G13, G30, G31, and G32 (eTable 2). AD and VaD also served as secondary outcomes in subtype analyses.

The exposure variable PDPD were defined as (a) any psychiatric diagnoses established before dementia diagnoses or (b) psychiatric diagnoses without any concurrent dementia diagnoses. PDPD include four subcategories: psychotic disorders (schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders; ICD-10: F20, F22, F23, F25, F28, F29), bipolar spectrum disorders (bipolar disorder and manic episode; ICD-10: F30, F31), depressive disorders (depressive episode and other mood disorders; ICD-10: F32, F33, F34, 38, F39), and anxiety disorders (ICD-10: F40–F48) (eTable 2). Alcohol use disorder (AUD) (ICD-10: F10) and smoking history, which have been previously discussed as potential dementia risk factors11 were obtained in addition to the four categories of psychiatric disorders. AUD is often underdiagnosed33,34 and an AUD diagnosis may be entered into medical records when health complications arise; thus, we used AUD at any time and, in sensitivity analysis, pre-dementia AUD as exposure variables. Age-at-onset (AAO) of a disease was inferred by the difference between the year when a diagnosis was first documented and the subject's year of birth. If a subject had multiple psychiatric diagnoses, the earliest date was used as AAO of PDPD. We excluded AAO for PDPD <4 years (the youngest age reported in epidemiological studies35) or AAO for dementias <30 years of age. ICD-10 F07–F09 codes were considered neither psychiatric disorders nor dementia (set as missing), because of the ambiguity for the purpose of this study, as they overlap with both psychiatric disorders and dementia.

Polygenic risk scores for dementia

The UKB genetic dataset included PRS for 53 diseases and quantitative traits, which were generated using a Bayesian approach applied to meta-analysed (when possible, ancestry specific) summary statistics data obtained entirely from external GWAS.36 We obtained these PRS for AD from the UKB data-field 26,206. The PRS were normalised by scaling to a mean of 0 and a standard deviation (SD) of 1. Pre-calculated genetic principal components (PCs) are based on genotyping data.32

Statistical analysis

Single variable analysis: Participants with and without dementia were compared for key variables by using t-test for continuous and chi-square test for binary variables. Multivariable logistic regression was used to estimate the association between PDPD and dementia, adjusted for PRS, age at recruitment, sex (self-reported), education (no college vs college), smoking (ever vs never smoker), AUD, and first 10 PCs. Sensitivity analyses were performed by omitting covariables.

Four graphical causal models were formulated.30,31,37,38 (a) PDPD signify dementia prodrome as a consequence of dementia pathology (i.e. reverse causation). In the absence of measures for dementia pathology, we use dementia diagnosis as a surrogate, assuming that participants with a dementia diagnosis had preceding dementia pathology. (b) PDPD represent a mediator of AD PRS on dementia, in which PDPD would reduce the effect of AD PRS on dementia if adjusted for in a model. To this end, we compare the regression coefficient for PRS on dementia before and after adjusting for PDPD as a covariable. (c) PDPD and AD PRS are uncorrelated risk factors. A collider effect occurs when a correlation between two (uncorrelated) exposure variables arises from their shared influence on an outcome variable, when that outcome variable (the collider) is adjusted for in an association analysis.38,39 Since a collider effect can indicate a causal relationship, we evaluated whether dementia is a collider in the association between PRS and PDPD by adjusting for dementia as a covariable. Under this model, adjusting for dementia would produce a negative association between PRS and PDPD by introducing a collider effect.39 This would be expected because the absence of genetic risk factors in a dementia patient makes the presence of other independent causal factors more likely. (d) Shared causes (confounders) account for the association between PDPD and dementia. While many unmeasured confounders may influence PDPD and dementia risk, we test whether AUD serves as a shared risk factor. The consistency of the data with these different models was statistically evaluated with logistic regression.

The statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.2.3.40 Bonferroni correction was used to adjust the P-value threshold for multiple testing. A P-value threshold of 0.0029 was used (0.05/17, considering 7 predictors and 10 genetic PCs) for inferring significance in this study.

Role of funders

The funders had no role in study design, data procurement, analysis, interpretation, or report writing.

Results

Association between pre-dementia psychiatric disorders and incident dementia

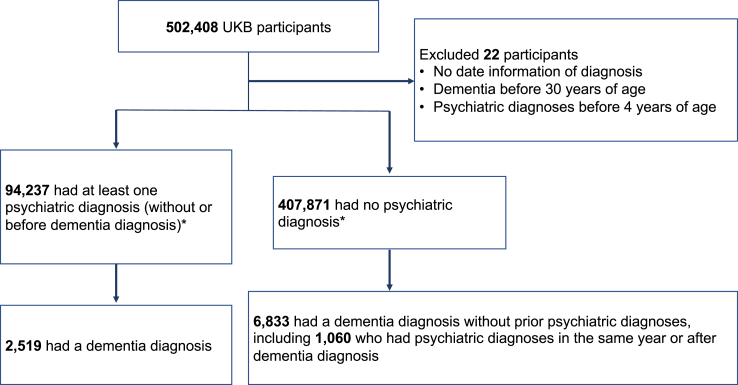

We obtained data from 502,408 UKB participants with a mean (SD) age at recruitment of 56.5 (8.1) years, and 273,324 (54.4%) were female. In total, 94,237 (18.8%) had PDPD, and the overall incidence of dementia was 9352 (1.9%) (Fig. 1; Table 1). Among 94,237 participants with PDPD, 2519 (2.6%) developed subsequent dementia, while 6833 (1.7%) of 407,871 non-PDPD participants had dementia. Among the 6833 non-PDPD participants with dementia, 1060 received a psychiatric diagnosis concurrent with or after a dementia diagnosis, including 301 anxiety, 492 depression, 14 bipolar disorder, 45 psychosis, and 208 multiple psychiatric diagnoses. The dementia diagnosis of this group of participants was considered to be non-PDPD dementia. PDPD, age at recruitment, ever smoked, and AUD were associated with higher dementia risk in unadjusted analyses (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart for the selection of the analysed participants from the UK Biobank cohort. ∗ ICD-10 F07–F09 diagnoses (n = 278) were set as missing, thus excluded from psychiatric as well as dementia diagnoses.

Table 1.

Demographics and psychiatric disorders stratified by incident dementia.

| Dementia |

P-valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| Sample size (n) | 493,025 | 9352 | |

| Sex: female (%) | 268,975 (54.6) | 4333 (46.3) | <0.001 |

| Age at recruitment (mean (SD)) | 56.40 (8.08) | 63.60 (5.47) | <0.001 |

| Education: college (%) | 159,220 (32.3) | 1898 (20.3) | <0.001 |

| Genetically European ancestry (%) | 401,832 (81.5) | 7697 (82.3) | 0.05 |

| Ever smoked: current or past smoker (%) | 220,958 (45.1) | 5019 (54.3) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol use disorders (mean (SD)) | 11,772 (2.4) | 939 (10.0) | <0.001 |

| PRS (mean (SD)) | 0.04 (0.99) | 0.56 (1.19) | <0.001 |

| PDPD (%) | 91,718 (18.6) | 2519 (26.9) | <0.001 |

| PDPD: psychosis (%) | 2292 (0.6) | 149 (2.1) | <0.001 |

| PDPD: bipolar (%) | 2530 (0.6) | 155 (2.2) | <0.001 |

| PDPD: depression (%) | 59,338 (12.9) | 1758 (20.5) | <0.001 |

| PDPD: anxiety (%) | 52,674 (11.6) | 1263 (15.6) | <0.001 |

PDPD: pre-dementia psychiatric disorders including psychiatric disorders without incident dementia; PRS: polygenic risk scores for Alzheimer's disease.

Unadjusted, Chi-square for categorical and t-test for continuous variables. Bold P-values denote statistical significance at the p < 0.0029 level.

Both PRS (OR, 1.58, 95% CI, 1.55–1.61) and PDPD (OR, 1.61, 95% CI, 1.54–1.69) were associated with greater risk for dementia in univariate regression analysis. PRS and PDPD remained significantly associated with subsequent dementia after adjusting for sex, age at recruitment, education, smoking, AUD, and PCs (Table 2, eTable 3a). In this joint model, each SD increase in PRS was associated with 62% (OR, 1.62, 95% CI, 1.59–1.65) greater dementia risk. PDPD were associated with a 73% (OR, 1.73, 95% CI, 1.65–1.82) greater risk for dementia compared to not having PDPD. AUD was associated with more than 4-times greater dementia risk (OR, 4.2, 95% CI, 3.88–4.54), while being female and having a college education were associated with lower risk. To examine the robustness of our analysis, we repeated the association in the subset of 409,529 participants with European ancestry, which showed similar results (eTable 3b). Furthermore, the association between PDPD and subsequent dementia remained substantially unchanged when only dementia diagnoses (n = 8802) occurring after enrollment were used (eTable 3c).

Table 2.

Association between AD PRS and psychiatric disorders with subsequent dementia.

| Outcome: dementia | OR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| PRS | 1.62 | 1.59–1.65 | <1.0E-320 |

| PDPD | 1.73 | 1.65–1.82 | 4.5E-104 |

| Sex (female) | 0.80 | 0.77–0.84 | 8.7E-23 |

| Age at recruitment | 1.18 | 1.17–1.18 | <1.0E-320 |

| Education (college) | 0.74 | 0.70–0.78 | 2.4E-29 |

| Ever smoker | 1.07 | 1.03–1.12 | 1.4E-03 |

| Alcohol use disorder | 4.20 | 3.88–4.54 | 2.5E-285 |

PDPD: pre-dementia psychiatric disorders including psychiatric diagnoses established before dementia diagnoses or psychiatric disorders without concurrent dementia diagnoses; PRS: polygenic risk scores for Alzheimer's disease; OR: Odds ratio. 95% CI: 95% confidence interval. Bold values denote variables of interest and statistical significance at the P < 0.0029 level.

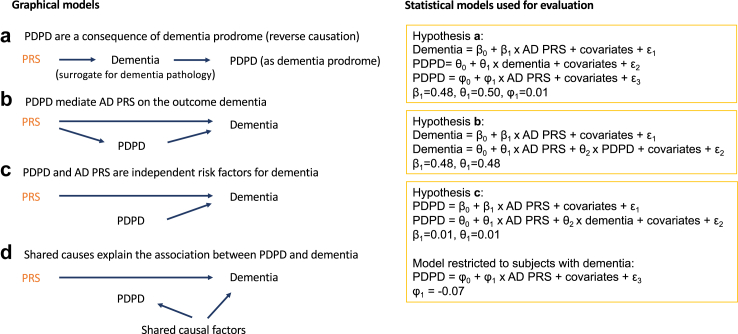

Next, we evaluated whether our data are consistent with four possible models of the relationship between PRS, PDPD, and dementia. The first model examines hypothesis (a) that PDPD signify dementia prodrome as a consequence of dementia pathology (Fig. 2a). Given the observed association of PRS-dementia and dementia-PDPD, we would expect a positive correlation between the exposure variable PRS and the outcome PDPD, if PDPD were a dementia prodrome. The expected coefficient for PRS on PDPD would be β1 x θ1 = 0.24 (β1 = 0.48; θ1 = 0.50). However, the observed coefficient (φ1 = 0.01, 95% CI, 0.002–0.017, not significant) was too weak to be considered as a major driver of the association between PRS and dementia (eTable 4a). These results remained consistent in a sensitivity analysis without covariables (eTable 4a). The second model examines hypothesis (b) that PDPD are a mediator for PRS on dementia (Fig. 2b). Mediation analysis31 showed that adding PDPD as a covariable to PRS (eTable 4b) did not substantially change the regression coefficient of PRS on dementia (β1–θ1 = 0). Thus, the PDPD and dementia association is largely independent from the polygenic risk for dementia. The third model hypothesises (c) that PDPD is a causal risk independent from PRS (Fig. 2c). The weak coefficient for PRS on PDPD (β1 = 0.01, 95% CI, 0.007–0.022, P = 1.1E-4) remained largely unchanged when adding dementia as a covariable (θ1 = 0.01, 95% CI, 0.002–0.017, not significant) (eTable 4c). However, when restricting the analysis to dementia cases only, a weak negative correlation between PDPD and PRS emerged (φ1 = −0.07, 95% CI, −0.11 to −0.02, P = 1.9E-3). This weak collider effect suggests that PDPD may not play a large causal role. Thus, hypothesis (d) (shared factors) would remain to explain a large part of the association between PDPD and dementia (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 2.

Hypotheses on relationships between AD PRS and PDPD on Dementia. The graphical models are shown on the left side and the corresponding statistical models used for evaluation are on the right side. The graphical model a corresponds to three linear models for hypothesis a, wherein β0, θ0, φ0 represent the intercepts of the regression models, and β1, θ1, φ1 represent the regression coefficients. The error terms are denoted as ε₁, ε₂, and ε₃. An analogous notation is used for the linear models of hypothesis b, corresponding to the graphical model b, and hypothesis c, corresponding to both graphical models c and d. PRS: Polygenic risk scores for dementia; PDPD: pre-dementia psychiatric disorders including psychiatric diagnoses established before dementia diagnoses or psychiatric disorders without concurrent dementia diagnoses.

Alcohol use disorder as a common risk factor for both dementia and PDPD

Among UKB participants, AUD was associated with both dementia (OR, 4.42, 95% CI, 4.10–4.78) and PDPD (OR, 3.30, 95% CI, 3.17–3.43) adjusting for sex, age at recruitment, education, smoking, and PCs (eTable 5a–d). We applied causal modelling to determine whether AUD represented a shared causal factor for dementia and PDPD. Indeed, PRS was not associated with AUD (coefficient = −0.01, 95% CI, −0.026 to 0.01, not significant) in univariate regression, but adjusting for dementia (as collider) produced a negative association between PRS and AUD (coefficient = −0.04, 95% CI, −0.055 to −0.019, P = 7.3E-5) (eTable 6). Furthermore, the association between PDPD and dementia became non-significant in participants with AUD (eTable 5e and f). In contrast, AUD remained significantly associated with dementia among participants with PDPD (eTable 5g and h). Accordingly, we also observed a greater effect size of AUD on dementia among participants with PRS in the bottom decile (OR, 7.14, 95% CI, 5.57–9.16) than among participants in the top PRS decile (OR, 3.08, 95% CI, 2.57–3.68), further supporting AUD being a causal factor for dementia.

Association between pre-dementia psychiatric disorders and dementia subtypes

We investigated the associations of PRS and PDPD with the dementia subtypes AD (n = 3365) and VaD (n = 1823). Each standard deviation increase of PRS was associated with a 2-fold greater AD risk and a 62% greater VaD risk. PDPD were associated with a 46% greater risk for AD and a 2-fold greater risk for VaD (Table 3). This remained unchanged after excluding cases with diagnoses of both AD and VaD (eTable 7). AUD was associated with a 69% increased risk for AD and a 3-fold risk increase for VaD. Having a college education was associated with a 29% reduced risk for AD and a 40% reduced risk for VaD, compared to no college education. Being female was associated with decreased risk for VaD, but not for AD. Smoking history was not associated with AD, but with a 14% increased risk for VaD.

Table 3.

Association between psychiatric disorders with dementia subtypes.

| Outcome: Alzheimer's disease |

Outcome: vascular dementia |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P-value | OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| PDPD | 1.46 | 1.34–1.59 | 2.2E-18 | 2.08 | 1.87–2.32 | 1.2E-41 |

| PRS | 2.09 | 2.03–2.16 | <1.0E-320 | 1.62 | 1.55–1.68 | 1.0E-110 |

| Sex (female) | 0.98 | 0.91–1.06 | 6.4E-01 | 0.65 | 0.58–0.71 | 1.6E-17 |

| Age | 1.23 | 1.22–1.24 | <1.0E-320 | 1.25 | 1.22–1.27 | 4.9E-295 |

| Education (college) | 0.71 | 0.65–0.78 | 2.1E-13 | 0.60 | 0.53–0.68 | 1.3E-14 |

| Ever smoker | 1.02 | 0.94–1.09 | 0.67 | 1.14 | 1.03–1.26 | 0.01 |

| Alcohol use disorder | 1.69 | 1.41–2.01 | 7.1E-09 | 3.00 | 2.51–3.56 | 1.2E-34 |

PDPD: pre-dementia psychiatric disorders including psychiatric diagnoses established before dementia diagnoses or psychiatric disorders without concurrent dementia diagnoses; PRS: polygenic risk scores for Alzheimer's disease; OR: odds ratio. 95% CI: 95% confidence interval. Bold P-values denote statistical significance at the P < 0.0029 level.

Influence of documented age at diagnosis for PDPD and dementia

The mean AAO inferred by the age at PDPD documentation was 49.8 years (SD = 14.9) with a median age of 51.0 years (eFigure 1). Among participants with PDPD, those who developed dementia had significantly higher AAO for psychiatric diagnoses (mean = 54.9, SD = 15.6) than participants without dementia (mean = 49.6, SD = 14.9) (t-test P < 2.0E-16). To address a potential delay of digital documentation for AAO41 before 2010, we performed a sensitivity analysis by examining the subset of participants whose PDPD were documented before 2010 stratified by length of time gap (i.e. 1, 5, or 10 years) between PDPD and dementia (eTable 8). PDPD were associated with dementia across the time gap strata. The magnitude of risk increase ranged from 49% for participants with at least a 10-year gap to 82% for participants with at least a 1-year gap between PDPD and dementia. Furthermore, to find out if the association between PDPD and dementia remains robust against AAO for PDPD, we performed sensitivity analyses in different age strata of AAO for PDPD. This association persisted among those diagnosed with PDPD in early, middle, or late life (<40 years: OR, 2.30, 95% CI, 2.06–2.55; 40–50 years: OR, 2.46; 95% CI, 2.19–2.76; 50–60 years: OR, 1.98; 95% CI, 1.81–2.17; >60 years: OR, 1.65, 95% CI, 1.54–1.77) (eTable 9).

Association between subcategories of psychiatric disorders and dementia

Finally, we explored the association between subcategories of PDPD and dementia. Pre-dementia psychotic disorders (OR, 3.81, 95% CI, 3.15–4.57, P = 9.4E-45) and bipolar spectrum disorders (OR, 3.96, 95% CI, 3.30–4.75, P = 3.8E-50) were both associated with a nearly 4-fold higher dementia risk, while depressive disorders were associated with nearly a 2-fold (OR, 1.91, 95% CI, 1.81–2.02, P = 8.0E-109), and anxiety disorders with a 49% (OR, 1.49, 95% CI, 1.39–1.59, P = 9.2E-34) greater dementia risk.

Discussion

In this large population-based study of half a million UK Biobank participants, psychiatric disorders were significantly associated with incident dementia. Participants with at least one psychiatric diagnosis (PDPD) were 73% more likely to develop subsequent dementia, compared to those without PDPD. Polygenic dementia risk was associated with all-cause dementia and across dementia subtypes, consistent with the notion that many of the known genetic risk factors act across dementia subtypes. The associations of PDPD and AD PRS with dementia remained unchanged when the analysis was restricted to participants of genetically defined European ancestry. Our causal modelling found strong support that the association between PDPD and incident dementia is independent from the dementia polygenic risk. While PDPD may potentially play a small causal role in dementia, as indicated by the collider effect in the stratified analysis, the models suggested that shared causes for both PDPD and dementia to a large degree account for the association between them. AUD was associated with both PDPD and dementia. Our models indicated that AUD is a shared risk factor for both.

Our results have multiple implications. First, we confirmed previous reports that individuals with psychiatric conditions are at elevated risk for subsequent dementia in the large population-based UKB data with comparable magnitudes to previously reported associations.15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 Several previous studies included more than one million individuals, thus were very well powered. A population-based register study including 1.7 million New Zealanders20 showed that relative to individuals without a mental disorder, those with a mental disorder were at a 4.4-times increased risk of developing subsequent dementia over a 30-year period. That study also showed that the magnitude of risk association was greatest for psychotic disorders, followed by depression, and then neurotic disorders, such as anxiety. Consistently, our study showed a 1.7-fold increase in dementia risk for PDPD in a much shorter observation period of 12–16 years and we also found psychotic and bipolar spectrum disorders, although much less common, were associated with a greater magnitude of dementia risk than depression and anxiety. In a population-based study of 8 million Medicare beneficiaries in the United States, Stroup et al.18 found a greater difference in dementia prevalence between individuals with schizophrenia and those without serious mental illness at 66 years of age (27.9% vs 1.3%) than at 80 years of age (72% vs 11.3%). Ribe et al.15 found in a population-based study of 2.8 million persons in Denmark that schizophrenia was associated with a more than 2-fold higher risk of dementia, compared to those without schizophrenia over a follow-up time of 18 years and the risk was higher among younger individuals. Most recently, a population-based Danish study including over 1.4 million individuals showed that depression more than doubled the hazard for dementia, and the association persisted when depression was diagnosed in early (HR, 3.08), middle (HR, 2.95), or late (HR, 2.31) life. Our results not only confirmed these previously reported risk associations, but also showed that early life PDPD (AAO <40 years) may bear a greater risk association with dementia than late life PDPD (AAO >60 years). The replication of previous findings showcased the integrity of diagnoses in the UKB. Unlike previous studies based on population registry, the UKB was designed to include genetics, imaging, and blood biomarkers among many health phenotypes, which enables future in-depth investigations of causal mechanisms that may explain the link between PDPD and dementia.

Second, the notion that psychiatric disorders mainly signify prodromal dementia is not supported by our results involving genetic risks. If PDPD represented pre-clinical dementia, as described in MBI,25 then one would expect that AD PRS to be positively associated with PDPD. Among UKB participants, this association between PRS and PDPD was far too weak to be considered supportive of this hypothesis. Thus, the observed strong association between PDPD and incident dementia in UKB is unlikely to be explained by reverse causation alone.

Third, we found no evidence that psychiatric disorders mediate AD polygenic risks on dementia. Thus, psychiatric diagnoses before dementia are biologically distinct from known genetic risk factors for dementia. This finding is consistent with the results from a recent phenome-wide association study in UKB participants, which did not find any association between APOE risk genotypes (an established major gene for dementia) and risk for psychiatric diseases.42

Fourth, our analysis using dementia as a collider provided only weak support for psychiatric disorders being an independent direct causal risk for dementia. More specifically, adjusting for dementia as a hypothetical collider did not introduce any substantial collider bias39 into the relationship between PRS and PDPD, but a weak collider effect was observed in the stratified analysis in dementia cases. Thus, shared risk factors for both PDPD and dementia might explain most of the PDPD-dementia association.38 A recent study also showed that anxiety is associated with increased risk of cognitive impairment in non-demented older adults and the effect of anxiety was partially mediated by brain tau burden.43 However, given that tau burden is an established causal factor for several forms of dementia, such as AD and frontotemporal dementia, it could also represent a shared risk factor for anxiety and cognitive impairment. Compared to participants without AUD, those with an AUD had more than 4-fold increased risk for future dementia, consistent with previous reports linking heavy alcohol consumption with dementia.13,44 Using dementia as a collider for the association between AD PRS and AUD, we observed a collider effect that would be consistent with AUD causally contributing to dementia.38 While the relationship between AUD and psychiatric disorders has been a subject of ongoing research and debate,45 the particularly high effect sizes of AUD among participants carrying lower dementia polygenic risks further underscore that AUD is a separate risk factor. Our observations that the association between PDPD and dementia became non-significant among participants with AUD, while the association between AUD and dementia remained significant among participants with PDPD, further point to the causal role of AUD. Our findings also underscore the importance of treating AUD and better understanding the complex interplay between environmental factors and PDPD to prevent dementia.

Finally, AD PRS used in this study were calculated from external GWAS that contained subjects that were ascertained as AD cases, but were significantly associated with both AD and VaD. This underscores the challenges for clinical diagnosis of dementia and the fact that most dementia patients have a mixed form of dementia. This finding also points to the importance of studying risk factors for all-cause dementia.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. (1) Incomplete inclusion of the primary care dataset46 in the UKB may have resulted in undercount for both psychiatric and dementia phenotypes, which would reduce statistical power. However, our results on association between PDPD and dementia were consistent with many previous reports, which supports the validity of our dataset. (2) We did not analyse other potential risk factors for dementia such as other behaviour risk factors (e.g. physical inactivity and nutrition) or cardiovascular risks.11,47 (3) The documented AAO for PDPD in UKB participants was older than expected, which could indicate self-selection bias–lower participation of people with early-onset PDPD. Alternatively, it could be due to delayed diagnosis documentation, as the digitalization of mental health records occurred in the early 2000s in UK,41 as shown in eFigure 1. Our sensitivity analysis in participants with PDPD documented before 2010 showed that the results remained substantially unchanged. (4) Lack of diversity of UKB participants may limit the generalizability of our findings, which need to be further studied in more diverse datasets. (5) In this study, we used PRS to capture cumulative genetic effects on a trait, and we did not investigate gene-by-environment or gene-through-environment effects. Future refined analyses are required to fully disentangle the influence of gene-by-environment and gene-through-environment effects. (6) It is well known that PRS only explain a portion of disease variance depending on the age of the study population7,48 and their usage for prediction in clinical settings is still in an experimental stage. However, in our analysis, we use PRS only as a causal anchor variable and do not focus on the predictive power of PRS. (7) Confounding factors in the original GWAS, such as ascertainment bias and population structure, may inflate phenotypic correlations that are likely reflected in PRS.49,50 Thus, PRS for one trait (e.g. AD) may capture liability for any other trait that differs in prevalence between cases and controls (e.g. PDPD) regardless of whether these traits share causal genetic factors. This may affect the use of PRS in causal models, which can contribute to inconclusive findings. However, in our study, AD PRS were not associated with PDPD, despite the possibility of PDPD being enriched among cases in AD GWAS due to the association between PDPD and dementia.

Conclusion

We found that pre-dementia psychiatric disorders were associated with increased dementia risk, and they represent neither prodromal dementia nor mediated established common genetic risks for dementia. Shared risk factors may account for a large part of the association between psychiatric disorders and dementia. Alcohol use disorder is a modifiable risk factor with a large effect that is shared by both PDPD and dementia.

Contributors

Drs Freudenberg-Hua and Li had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the underlying data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Concept and design: Dr. Freudenberg-Hua.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: Drs Freudenberg-Hua and Li.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Drs Freudenberg-Hua and Li.

Obtained funding: Dr. Freudenberg-Hua.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Drs Freudenberg-Hua, Li, and Lee.

Supervision: Drs Goate, Koppel and Ma.

All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data sharing statement

UK Biobank data are available through application at: https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/enable-your-research/apply-for-access.

Declaration of interests

Dr. Goate received research funding from NIH and JPB Foundation, consulting fees from Muna Therapeutics and Genentech, payment for lectures from Biogen, Alector, and Denali Therapeutics, stock options from Cognition Therapeutics.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Freudenberg-Hua received funding from NIH/NIA (K08AG054727).

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2024.104978.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Corriveau R.A., Koroshetz W.J., Gladman J.T., et al. Alzheimer's disease-related dementias summit 2016: national research priorities. Neurology. 2017;89(23):2381–2391. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gatz M., Reynolds C.A., Fratiglioni L., et al. Role of genes and environments for explaining Alzheimer disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(2):168–174. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellenguez C., Küçükali F., Jansen I.E., et al. New insights into the genetic etiology of Alzheimer's disease and related dementias. Nat Genet. 2022;54(4):412–436. doi: 10.1038/s41588-022-01024-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sims R., Hill M., Williams J. The multiplex model of the genetics of Alzheimer's disease. Nat Neurosci. 2020;23(3):311–322. doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-0599-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leonenko G., Baker E., Stevenson-Hoare J., et al. Identifying individuals with high risk of Alzheimer's disease using polygenic risk scores. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):4506. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24082-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi S.W., Mak T.S., O'Reilly P.F. Tutorial: a guide to performing polygenic risk score analyses. Nat Protoc. 2020;15(9):2759–2772. doi: 10.1038/s41596-020-0353-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fulton-Howard B., Goate A.M., Adelson R.P., et al. Greater effect of polygenic risk score for Alzheimer's disease among younger cases who are apolipoprotein E-ε4 carriers. Neurobiol Aging. 2021;99:101.e1–101.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2020.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freudenberg-Hua Y., Li W., Davies P. The role of genetics in advancing precision medicine for Alzheimer's disease-a narrative review. Front Med (Lausanne) 2018;5:108. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kapasi A., DeCarli C., Schneider J.A. Impact of multiple pathologies on the threshold for clinically overt dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 2017;134(2):171–186. doi: 10.1007/s00401-017-1717-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyle P.A., Yu L., Wilson R.S., Leurgans S.E., Schneider J.A., Bennett D.A. Person-specific contribution of neuropathologies to cognitive loss in old age. Ann Neurol. 2018;83(1):74–83. doi: 10.1002/ana.25123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Livingston G., Huntley J., Sommerlad A., et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2020;396(10248):413–446. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lourida I., Hannon E., Littlejohns T.J., et al. Association of lifestyle and genetic risk with incidence of dementia. JAMA. 2019;322(5):430–437. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.9879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rehm J., Hasan O.S.M., Black S.E., Shield K.D., Schwarzinger M. Alcohol use and dementia: a systematic scoping review. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2019;11(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s13195-018-0453-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linli Z., Rolls E.T., Zhao W., Kang J., Feng J., Guo S. Smoking is associated with lower brain volume and cognitive differences: a large population analysis based on the UK Biobank. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2023;123 doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2022.110698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ribe A.R., Laursen T.M., Charles M., et al. Long-term risk of dementia in persons with schizophrenia: a Danish population-based cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(11):1095–1101. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin C.E., Chung C.H., Chen L.F., Chi M.J. Increased risk of dementia in patients with Schizophrenia: a population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Eur Psychiatry. 2018;53:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skogen J.C., Bergh S., Stewart R., Knudsen A.K., Bjerkeset O. Midlife mental distress and risk for dementia up to 27 years later: the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT) in linkage with a dementia registry in Norway. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:23. doi: 10.1186/s12877-015-0020-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stroup T.S., Olfson M., Huang C., et al. Age-specific prevalence and incidence of dementia diagnoses among older US adults with schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(6):632–641. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.0042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barnes D.E., Yaffe K., Byers A.L., McCormick M., Schaefer C., Whitmer R.A. Midlife vs late-life depressive symptoms and risk of dementia: differential effects for Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(5):493–498. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richmond-Rakerd L.S., D'Souza S., Milne B.J., Caspi A., Moffitt T.E. Longitudinal associations of mental disorders with dementia: 30-year analysis of 1.7 million New Zealand citizens. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79(4):333–340. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.4377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saczynski J.S., Beiser A., Seshadri S., Auerbach S., Wolf P.A., Au R. Depressive symptoms and risk of dementia: the framingham heart study. Neurology. 2010;75(1):35–41. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e62138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh-Manoux A., Dugravot A., Fournier A., et al. Trajectories of depressive symptoms before diagnosis of dementia: a 28-year follow-up study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(7):712–718. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brenowitz W.D., Zeki Al Hazzouri A., Vittinghoff E., Golden S.H., Fitzpatrick A.L., Yaffe K. Depressive symptoms imputed across the life course are associated with cognitive impairment and cognitive decline. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;83(3):1379–1389. doi: 10.3233/JAD-210588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kales H.C., Gitlin L.N., Lyketsos C.G. Assessment and management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. BMJ. 2015;350:h369. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ismail Z., Smith E.E., Geda Y., et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms as early manifestations of emergent dementia: provisional diagnostic criteria for mild behavioral impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(2):195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Howard D.M., Adams M.J., Clarke T.K., et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis of depression identifies 102 independent variants and highlights the importance of the prefrontal brain regions. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22(3):343–352. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0326-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anttila V., Bulik-Sullivan B., Finucane H.K., et al. Analysis of shared heritability in common disorders of the brain. Science. 2018;360(6395) doi: 10.1126/science.aap8757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roelfs D., Alnæs D., Frei O., et al. Phenotypically independent profiles relevant to mental health are genetically correlated. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):202. doi: 10.1038/s41398-021-01313-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levey D.F., Stein M.B., Wendt F.R., et al. Bi-ancestral depression GWAS in the Million Veteran Program and meta-analysis in >1.2 million individuals highlight new therapeutic directions. Nat Neurosci. 2021;24(7):954–963. doi: 10.1038/s41593-021-00860-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baron R.M., Kenny D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacKinnon D.P., Lamp S.J. A unification of mediator, confounder, and collider effects. Prev Sci. 2021;22(8):1185–1193. doi: 10.1007/s11121-021-01268-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bycroft C., Freeman C., Petkova D., et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature. 2018;562(7726):203–209. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0579-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hallgren K.A., Witwer E., West I., et al. Prevalence of documented alcohol and opioid use disorder diagnoses and treatments in a regional primary care practice-based research network. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2020;110:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2019.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams E.C., Fletcher O.V., Frost M.C., Harris A.H.S., Washington D.L., Hoggatt K.J. Comparison of substance use disorder diagnosis rates from electronic health record data with substance use disorder prevalence rates reported in surveys across sociodemographic groups in the veterans health administration. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(6) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.19651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Merikangas K.R., Nakamura E.F., Kessler R.C. Epidemiology of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2009;11(1):7–20. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.1/krmerikangas. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thompson D.J., Wells D., Selzam S., et al. UK Biobank release and systematic evaluation of optimised polygenic risk scores for 53 diseases and quantitative traits. medRxiv. 2022 doi: 10.1101/2022.06.16.22276246. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li W., Wang M., Irigoyen P., Gregersen P.K. Inferring causal relationships among intermediate phenotypes and biomarkers: a case study of rheumatoid arthritis. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(12):1503–1507. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hernán M.A., JM R. Chapman & Hall/CRC; Boca Raton: 2020. Causal inference: what if. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holmberg M.J., Andersen L.W. Collider bias. JAMA. 2022;327(13):1282–1283. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.R Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna Austria: 2022. https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takian A., Sheikh A., Barber N. We are bitter, but we are better off: case study of the implementation of an electronic health record system into a mental health hospital in England. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:484. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lumsden A.L., Mulugeta A., Zhou A., Hyppönen E. Apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotype-associated disease risks: a phenome-wide, registry-based, case-control study utilising the UK Biobank. eBioMedicine. 2020;59 doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun L., Li W., Qiu Q., et al. Anxiety adds the risk of cognitive progression and is associated with axon/synapse degeneration among cognitively unimpaired older adults. eBioMedicine. 2023;94 doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sabia S., Fayosse A., Dumurgier J., et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of dementia: 23 year follow-up of Whitehall II cohort study. BMJ. 2018;362:k2927. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k2927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Castillo-Carniglia A., Keyes K.M., Hasin D.S., Cerdá M. Psychiatric comorbidities in alcohol use disorder. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(12):1068–1080. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30222-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stroganov O., Fedarovich A., Wong E., et al. Mapping of UK Biobank clinical codes: challenges and possible solutions. PLoS One. 2022;17(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0275816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takeuchi H., Kawashima R. Nutrients and dementia: prospective study. Nutrients. 2023;15(4):842. doi: 10.3390/nu15040842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baker E., Leonenko G., Schmidt K.M., et al. What does heritability of Alzheimer's disease represent? PLoS One. 2023;18(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0281440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schoeler T., Speed D., Porcu E., Pirastu N., Pingault J.B., Kutalik Z. Participation bias in the UK Biobank distorts genetic associations and downstream analyses. Nat Hum Behav. 2023;7(7):1216–1227. doi: 10.1038/s41562-023-01579-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Border R., Athanasiadis G., Buil A., et al. Cross-trait assortative mating is widespread and inflates genetic correlation estimates. Science. 2022;378(6621):754–761. doi: 10.1126/science.abo2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.