Abstract

Purpose

We have re-evaluated the anatomical arguments that underlie the division of the spinal visceral outflow into sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions.

Methodology

Using a systematic literature search, we mapped the location of catecholaminergic neurons throughout the mammalian peripheral nervous system. Subsequently, a narrative method was employed to characterize segment-dependent differences in the location of preganglionic cell bodies and the composition of white and gray rami communicantes.

Results and Conclusion

One hundred seventy studies were included in the systematic review, providing information on 389 anatomical structures. Catecholaminergic nerve fibers are present in most spinal and all cranial nerves and ganglia, including those that are known for their parasympathetic function. Along the entire spinal autonomic outflow pathways, proximal and distal catecholaminergic cell bodies are common in the head, thoracic, and abdominal and pelvic region, which invalidates the “short-versus-long preganglionic neuron” argument.

Contrary to the classically confined outflow levels T1-L2 and S2-S4, preganglionic neurons have been found in the resulting lumbar gap. Preganglionic cell bodies that are located in the intermediolateral zone of the thoracolumbar spinal cord gradually nest more ventrally within the ventral motor nuclei at the lumbar and sacral levels, and their fibers bypass the white ramus communicans and sympathetic trunk to emerge directly from the spinal roots. Bypassing the sympathetic trunk, therefore, is not exclusive for the sacral outflow. We conclude that the autonomic outflow displays a conserved architecture along the entire spinal axis, and that the perceived differences in the anatomy of the autonomic thoracolumbar and sacral outflow are quantitative.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10286-024-01023-6.

Keywords: Autonomic nervous system, Ganglion, Neural crest cells, Neuron, Preganglionic, Postganglionic

Introduction

The universally accepted model of the sympathetic and parasympathetic efferent limbs of the autonomic nervous system was formulated at the turn of the nineteenth to the twentieth century [1]. In addition to physiological and pharmacological criteria, anatomical arguments have been invoked to define the sympathetic-parasympathetic model [2–4]. These anatomical arguments have three main components. The first argument relates to the bimodal distribution of peripheral cell bodies, with the sympathetic cell bodies located in ganglia close to the central nervous system, and the parasympathetic cell bodies in a distal position, within or close to the wall of target organs. A second argument involves the absence of white rami communicantes at the sacral level. In contrast to the thoracolumbar sympathetic outflow, preganglionic neurons at the sacral level bypass the sympathetic trunk. Pelvic splanchnic nerves arise, therefore, directly from the sacral plexus. The third argument concerns the gap in the autonomic outflow at the lumbar level. As the autonomic outflow is concentrated around the T1-L2 and S2-S4 levels, the cell bodies of the preganglionic neurons do not appear as a continuous cell column. A parallel is therefore often drawn between the parasympathetic cranial and sacral outflows [2].

In this review, we re-evaluate the anatomical arguments that divide the spinal visceral outflow in sympathetic and parasympathetic partitions. A systematic literature search permitted us to map the location of catecholaminergic neurons throughout the entire mammalian peripheral nervous system. Subsequently, a narrative method was employed to characterize segment-dependent differences in the location of preganglionic cell bodies and the composition of white and gray rami communicantes. In total, it becomes apparent that the differences between the thoracolumbar and sacral outflow are not binary. The anatomy of the autonomic outflow displays a conserved architecture along the entire spinal axis, albeit with a quantitative gradient in characteristic features. This finding is compatible with recent data indicating that the molecular signature of preganglionic cells in the thoracolumbar and sacral region is highly similar [5].

Methods

This study meets the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (see Supplemental Word document and Supplemental interactive Tables 1 and 2). Literature was searched for studies dealing with the anatomical arguments that are used to divide the spinal visceral outflow into sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions. Using a systematic literature search, we first mapped the location of catecholaminergic neurons throughout the entire mammalian peripheral nervous system. The outcome of the systematic literature prompted us to look more closely into the location of the preganglionic neurons and the white and gray rami communicantes along the spinal cord. This search followed a narrative strategy and included studies from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. We ensured that only findings that comply with current scientific understanding are included in this review. Languages were restricted to English, German and French.

Data source and study selection for the systematic literature search

Abstracts, titles, and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) entry terms in PubMed were searched to identify original studies that either established the existence of catecholaminergic neurons histologically by demonstrating the presence of the enzymes tyrosine hydroxylase or dopamine β-hydroxylase, or confirmed communication between nerves and sympathetic structures using validated techniques such as neural tract tracing, experimental neural degeneration, crushing or denervation, and neural recording. Studies relying on macroscopic dissections alone were not included. Search terms included every nervous structure listed in Terminologia Anatomica [Anatomical Terminology] [6] under the headings “cranial nerves,” “spinal nerves” and “parasympathetic part of autonomic part of peripheral nervous system.” The last search was performed on July 11, 2023. The reference lists of retrieved articles were also reviewed for additional studies that fulfilled the search criteria.

Search strategy for the systematic literature search

The search for each structure consisted of two separate approaches. The first approach looked for the histologically confirmed presence of catecholaminergic neurons, and was executed by combining the entry terms of tyrosine hydroxylase or dopamine β-hydroxylase with (query term: AND) the nervous structure of interest. The second approach searched for communication between nerves and sympathetic structures, using the entry terms of sympathetic structures listed in Terminologia Anatomica [6] AND the nervous structures from search 1, AND neuroanatomical tract-tracing techniques (MeSH) OR horseradish peroxidase (MeSH) OR communication OR communicating OR communications OR anastomosis OR anastomosing OR connecting OR connection.

Findings and Discussion

For the systematic approach, a total of 43 queries for the cranial and 101 for the spinal nerves were performed, which provided information on 389 anatomical structures in 996 and 243 identified studies, respectively. All abstracts were screened for the inclusion criteria with respect to applied techniques, language, and species, resulting in 170 eligible studies (Table 1 and supplemental interactive Table 1 [extended Microsoft Excel-based Table]).

Table 1.

List of nerves containing catecholaminergic neurons

| Nerve | First author, year, and reference | Species | Extra signal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oculomotor | Oikawa, 2004 [198] | Human | |

| Maklad, 2001 [15] | Mouse | ||

| Ruskell,1983 [199] | Monkey | ||

| Trochlear | Hosaka, 2014 [76] | Human | |

| Oikawa, 2004 [198] | Human | ||

| Maklad, 2001 [15] | Mouse | ||

| Trigeminal, ciliary, submandibular, pterygopalatine, otic, trigeminal ganglion | Teshima, 2019 [78] | Mouse, human | #, *(Hand2+) |

| Hosaka, 2016 [200] | Human | ||

| Matsubayashi, 2016 [201] | Human | ||

| Yamauchi, 2016 [77] | Human | # | |

| Hosaka, 2014 [76] | Human | # | |

| Szczurkowski,2013[72] | Chinchilla | # | |

| Kiyokawa, 2012 [69] | Human fetus | # | |

| Rusu, 2010 [206] | Human | ||

| Thakker, 2008 [68] | Human | # | |

| Kaleczyc, 2005 [67] | Pig | #, *(DBH+) | |

| Reynolds, 2005 [24] | Rat | #, *(DBH+) | |

| Maklad, 2001 [15] | Mouse | ||

| Grimes, 1998 [66] | Rhesus monkey | #, *(DBH+) | |

| Kirch, 1995 [64] | Human | # | |

| Ng, 1995 [75] | Rat, monkey | # | |

| Tan, 1995 [65] | Cat, monkey | # | |

| Simons, 1994 [71] | Rat | #, *(DBH+) | |

| Marfurt, 1993 [23] | Rat, guinea pig | # | |

| Tyrrell, 1992 [63] | Rat | # | |

| Shida, 1991 [74] | Rat | # | |

| Soinila, 1991 [73] | Rat | # | |

| Yau, 1991 [213] | Cat | ||

| ten Tusscher, 1989 [214] | Rat | ||

| Kuwayama, 1988 [70] | Rat | # | |

| Landis,1987 [61] | Rat | #, *(DBH+) | |

| Uemura,1987 [62] | Japanese monkey, cat, dog | # | |

| Jonakait, 1984 [49] | Rat (embryo) | # | |

| Lackovic, 1981 [166] | Human | *(NA+) | |

| Abducens | Oikawa, 2004 [198] | Human | |

| Maklad, 2001 [15] | Mouse | ||

| Lyon,1992 [202] | Cynomolgus monkey | ||

| Johnston, 1974 [203] | Human | ||

| Facial, geniculate ganglion | Tereshenko, 2023 [204] | Human | |

| Tang, 2022 [25] | Mouse | # | |

| Ohman-Gault, 2017 [205] | Mouse | ||

| Matsubayash, 2016 [201] | Human | ||

| Yamauchi, 2016 [77] | Human | ||

| Hosaka, 2014 [76] | Human | ||

| Reuss, 2009 [207] | Rat | ||

| Maklad, 2001 [15] | Mouse | ||

| Johansson, 1998 [208] | Rat | ||

| Shibamori, 1994 [14] | Rat | ||

| Takeuchi, 1993 [209] | Cynomolgus monkey | ||

| Fukui, 1992 [210] | Cat | ||

| Anniko, 1987 [167] | Mouse | *(NA+) | |

| Matthews, 1986 [13] | Cat | ||

| Wilson, 1985 [12] | Cynomolgus, rhesus monkeys | ||

| Thomander, 1984 [211] | Cat | ||

| Schimozawa, 1978 [212] | Mouse | ||

| Vestibulocochlear, vestibular ganglion | Yamauchi, 2016 [77] | Human | |

| Shibamori, 1994 [14] | Rat | ||

| Hozawa, 1993 [155] | Guinea pig | *(DBH+) | |

| Yamashita, 1992 [215] | Guinea pig | ||

| Hozawa, 1990 [154] | Cynomolgus monkey | *(DBH+) | |

| Anniko, 1987 [167] | Mouse | *(NA+) | |

| Paradiesgarten, 1976 [216] | Cat | ||

| Densert, 1975 [168] | Rabbit and cat | *(NA+) | |

| Glossopharyngeal, petrosal ganglion | Oda, 2013 [79] | Human | # |

| Ichikawa, 2007 [37] | Rat | # | |

| Matsumoto, 2003 [217] | Rat | ||

| Wang, 2002 [36] | Rat | # | |

| Satoda, 1996 [220] | Cynomolgus monkey | ||

| Ichikawa, 1995 [34] | Rat | # | |

| Ichikawa, 1993 [33] | Rat | # | |

| Helke, 1991 [32] | Rat | # | |

| Helke, 1990 [29] | Rat | # | |

| Katz, 1990 [30] | Rat | # | |

| Kummer, 1990 [31] | Guinea pig | # | |

| Katz, 1987 [28] | Rat | # | |

| Katz, 1986 [27] | Rat | # | |

| Jonakait, 1984 [49] | Rat (embryo) | #, *(DBH+) | |

| Katz, 1983 [26] | Rat | # | |

| Vagus, superior and inferior (nodose) ganglion | Bookout, 2021 [47] | Mouse | *(DBH+, Hand2+) |

| Verlinden, 2016 [80] | Human | #, *(DBH+) | |

| Hosaka, 2014 (75) | Human | ||

| Seki, 2014 [218] | Human | ||

| Onkka, 2013 [219] | Dog | ||

| Ibanez, 2010 [82] | Human | # | |

| Kawagishi, 2008 [38] | Human | # | |

| Ichikawa, 2007 [37] | Rat | # | |

| Matsumoto, 2003 [217] | Rat | ||

| Nozdrachev, 2003 [221] | Cat | ||

| Forgie, 2000 [222] | Mouse | ||

| Yang, 1999 [150] | Rat | #, *(DBH+) | |

| Gorbunova, 1998 [45] | Rabbit | ||

| Ichikawa, 1998 [35] | Rat | # | |

| Sang, 1998 [46] | Mouse | # | |

| Ichikawa, 1996 [43] | Rat | # | |

| Uno, 1996 [44] | Dog | # | |

| Fateev, 1995 [223] | Cat | ||

| Ichikawa, 1995 [34] | Rat | # | |

| Zhuo, 1995 [42] | Rat | # | |

| Zhuo, 1994 [41] | Rat | # | |

| Yoshida, 1993 [40] | Cat | # | |

| Ruggiero, 1993 [228] | Rat | ||

| Dahlqvist, 1992 [81] | Rat | #, *(DBH+) | |

| Helke, 1991 [32] | Rat | # | |

| Helke, 1990 [29] | Rat | # | |

| Kummer, 1990 [31] | Guinea pig | # | |

| Ling, 1990 [230] | Hamster | ||

| Baluk, 1989 [232] | Guinea pig | ||

| Katz, 1987 [28] | Rat | # | |

| Dahlqvist, 1986 [171] | Rat | *(NA+) | |

| Lucier, 1986 [235] | Cat | ||

| Matthews, 1986 [13] | Cat | ||

| Smith, 1986 [237] | Guinea pig | ||

| Blessing, 1985 [238] | Rat | ||

| Smith, 1985 [240] | Guinea pig | ||

| Jonakait, 1984 [49] | Rat (embryo) | #, *(DBH+) | |

| Katz, 1983 [26] | Rat | # | |

| Hisa, 1982 [241] | Dog | ||

| Lackovic, 1981 [166] | Human | *(NA+) | |

| Ungváry, 1976 [243] | Cat | ||

| Nielsen, 1969 [169] | Cat | *(NA+) | |

| Kummer, 1993 [39] | Rat | # | |

| Lundberg, 1978 [242] | Cat, Guinea pig | ||

| Accessory | Hosaka, 2014 [76] | Human | |

| Hypoglossal | Hosaka, 2014 [76] | Human | |

| Tubbs, 2009 [83] | Human | # | |

| Tseng, 2005 [224] | Hamster | ||

| Tseng, 2001 [225] | Hamster | ||

| Hino, 1993 [226] | Dog | ||

| Fukui, 1992 [210] | Cat | ||

| O’Reilly, 1990 [227] | Rat | ||

| Greater auricular | Matsubayashi, 2016 [201] | Human | |

| Phrenic | Verlinden, 2018 [120] | Human | *(DBH+) |

| Lackovic, 1981 [166] | Human | *(NA+) | |

| Suprascapular | Hosaka, 2014 [76] | Human | |

| Mammary | Eriksson, 1996 [229] | Human, rat | |

| Lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve of forearm (musculocutaneous) | Marx, 2011 [231] | Human | |

| Marx, 2010 [233] | Human | ||

| Radial | Marx, 2010 [234] | Human | |

| Superficial branch of radial | Marx, 2010 [234] | Human | |

| Marx, 2011 [231] | Human | ||

| Palmar branch of ulnar | Balogh, 1999 [236] | Human | |

| Medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve of forearm | Marx, 2011 [231] | Human | |

| Marx, 2010 [239] | Human | ||

| Intercostal | Lackovic, 1981 [166] | Human | *(NA+) |

| Genitofemoral | Lackovic, 1981 [166] | Human | *(NA+) |

| Ilioinguinal | Lackovic, 1981 [166] | Human | *(NA+) |

| Sciatic | Creze, 2017 [149] | Human fetus | |

| Hosaka, 2014 [76] | Human | ||

| Loesch, 2010 [147] | Rat | ||

| Castro, 2008 [146] | Rat | ||

| Wang, 2002 [244] | Mouse | ||

| Li, 1999 [245] | Rat | ||

| Li, 1996 [247] | Rat | ||

| Li,1995 [248] | Rat | ||

| Li, 1994 [250] | Rat | ||

| Koistinaho, 1991 [249] | Human fetus | ||

| D’Hooge, 1990 [174] | Dog | *(NA+) | |

| Studelska, 1989 [254] | Rat | ||

| Dahlström, 1987 [173] | Rat | *(NA+) | |

| Dahlström, 1986 [172] | Rat | *(NA+) | |

| Larsson, 1986 [165] | Rat | *(DBH+, NA+) | |

| Schmidt, 1984 [164] | Rat | *(DBH+) | |

| Larsson, 1984 [163] | Rat | *(DBH+, NA+) | |

| Evers-Von Bültzingslöwen, 1983 [162] | Rabbit | *(DBH+) | |

| Dahlström, 1982 [170] | Rat | *(NA+) | |

| Jakobsen, 1981 [161] | Rat | *(DBH+) | |

| Häggendal, 1980 [160] | Rat | *(DBH+) | |

| Reid, 1975 [159] | Rat | *(DBH+) | |

| Keen, 1974 [157] | Rat | *(DBH+, NA+) | |

| Nagatsu, 1974 [158] | Rat | *(DBH+) | |

| Dairman, 1973 [156] | Rat | *(DBH+) | |

| Thoenen, 1970 [266] | Rat | ||

| Fibular | Tompkins, 1985 [148] | Human | |

| Jänig, 1984 [246] | Cat | ||

| Ben-Jonathan, 1978 [175] | Cat | *(NA+) | |

| Tibial | Koistinaho, 1991 [249] | Human fetus | |

| Sural | Fang, 2017 [251] | Rabbit | |

| Pudendal | Nyangoh Timoh, 2017 [252] | Human fetus | |

| Bertrand, 2016 [253] | Human fetus | ||

| Hinata, 2015 [255] | Human | ||

| Hieda, 2013 [256] | Human | ||

| Alsaid, 2011 [257] | Human fetus | ||

| Alsaid, 2009 [258] | Human fetus | ||

| Roppolo, 1985 [259] | Monkey | ||

| Perineal | Moszkowicz, 2011 [260] | Human fetus | |

| Colombel, 1999 [261] | Human | ||

| Nerve to levator ani | Hinata, 2014 [262] | Human | |

| Hinata, 2014 [263] | Human | ||

| Pelvic splanchnic | Jang, 2015 [18] | Human | # |

| Imai, 2006 [17] | Human | # | |

| Takenaka, 2005 [16] | |||

| Spinal root, dorsal root ganglia | Massrey, 2020 [99] | Human | # |

| Morellini, 2019 [269] | Rat | *(DBH+, NAT+) | |

| Oroszova, 2017 [59] | Rat | # | |

| McCarthy, 2016 [58] | Mouse | # | |

| Brumovsky, 2012 [57] | Mouse | # | |

| Li, 2011 [56] | Mouse | # | |

| Dina, 2008 [55] | Rat | #, *(DBH+, NAT+) | |

| Brumovsky, 2006 [54] | Mouse | # | |

| Ichikawa, 2005 [53] | Mouse | # | |

| Holmberg, 2001 [52] | Mouse | # | |

| Deng, 2000 [264] | Rat | ||

| Jones, 1999 [265] | Rat | ||

| Ma, 1999 [267] | Rat | ||

| Shinder, 1999 [268] | Rat | ||

| Thompson, 1998 [270] | Rat | ||

| Karlsson, 1994 [271] | Rat | ||

| Vega, 1991 [51] | Rat | # | |

| Kummer, 1990 [31] | Guinea pig | # | |

| Katz, 1987 [28] | Rat | # | |

| Price, 1985 [50] | Rat | # | |

| Jonakait, 1984 [49] | Rat (embryo) | #, *(DBH+) | |

| Price, 1983 [48] | Rat | # | |

| Lackovic, 1981 [166] | Human | *(NA+) |

For each nerve, studies confirming tyrosine hydroxylase-positive nerve fibers are listed with first author, year of publication and species investigated. Studies that demonstrate catecholaminergic (CA) cell bodies are indicated by #. Studies that demonstrate additional “sympathetic” phenotypic properties are indicated by *. DBH: dopamine β-hydroxylase, NA: noradrenaline, NAT: noradrenaline transporter. A more extensive interactive Microsoft Excel-based Table, provided with filter tools for study characteristics and findings, is provided in supplemental interactive Table 1

The narrative approach produced 60 relevant references from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Supplemental interactive Table 2 provides an overview of the findings extracted from these studies. Although the scientific views put forward in these studies often no longer meet current models, they do frequently present research findings that were made with still accepted techniques. The recent molecular studies of the development of cranial ganglia from Schwann cell precursors and their source [7–9], for instance, were preceded by specific histological observations in the early twentieth century [10, 11]. These classical observations have the advantage of including human embryos.

The distribution of catecholaminergic neurons

Nerve fibers

Throughout the mammalian body, catecholaminergic nerve fibers have been demonstrated in many spinal and all cranial nerves and ganglia (Table 1). Catecholaminergic nerve fibers are also present in established parasympathetic nerves [4, 6], such as the greater petrosal nerve in mice, rats, cats, and monkeys [12–15] and the pelvic splanchnic nerves in humans [16–18]. We found no species-specific differences. Although we focused on mammals, we also encountered similar observations in birds [19, 20] and amphibia [21, 22], suggesting evolutionary conservation of the observed features.

Cell bodies

Catecholaminergic cell bodies have a more widespread distribution than generally acknowledged [2, 4, 6]. They are found in the trigeminal [23, 24], geniculate [25], inferior glossopharyngeal [26–37], superior [31, 38], and inferior [26, 28, 29, 31, 32, 34, 35, 37–47] vagal ganglia, and in dorsal root ganglia at all spinal levels [28, 31, 48–59]. Moreover, the generally accepted parasympathetic ganglia of the head [2], which include the ciliary [60–69], the otic [69], the pterygopalatine [69–72] and the submandibular ganglia [69, 73–78], all contain catecholaminergic cell bodies. Catecholaminergic cell bodies are found not only in ganglia, but also in the cranial nerves themselves, such as the (lingual branch of the) glossopharyngeal nerve [27, 79], the cervical [80] and laryngeal branches of the vagus nerve [81, 82], and the cranial root of the hypoglossal nerve [83]. In addition, catecholaminergic cell bodies are found in both the ventral and dorsal spinal nerve roots [84–99], and in the hypogastric and the (“parasympathetic”) pelvic splanchnic nerves [16, 17].

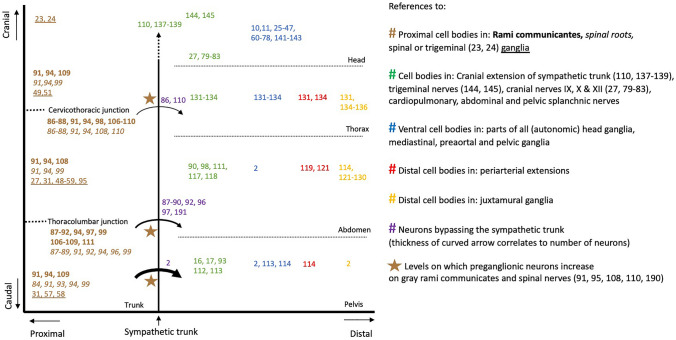

Argument 1: The short versus long preganglionic neuron

A commonly held concept in the classic subdivision of the autonomic outflow is the bimodal distribution of cell bodies, with the sympathetic cell bodies located in ganglia close to the central nervous system, and the parasympathetic cell bodies in a distal position, within or close to the wall of target organs. Our systematic review, in contrast, demonstrates that both proximal and distal catecholaminergic cell bodies are common throughout the entire spinal outflow (Fig. 1). The distribution of the cell bodies, therefore, cannot be used to subdivide the autonomic outflow.

Fig. 1.

Definitive catecholaminergic cell positions. References are plotted showing the position of cell bodies along the cranio-caudal (Y) and proximo-distal (X) body axes. Altogether, the data show that both proximal and distal ganglia are common in the entire thoracolumbar and sacral autonomic outflow pathways. Other references indicate the levels at which preganglionic neurons bypass the sympathetic trunk (curved arrows), or more frequently use the gray rami communicantes (brown stars)

Proximal locations

Catecholaminergic neurons are descendants of neural crest cells [100–102]. Trunk neural crest cells consist of several migrating groups. The core of the developing ganglia is established by an early cohort of neural crest cells that migrate ventrally to the mesenchyme dorsolateral to the dorsal aorta [102–105]. Many of these proximal cell bodies subsequently nest in the sympathetic trunk. Other proximal locations, however, include the spinal nerve roots [84–99], dorsal root ganglia [28, 31, 48–59, 95], and white and gray rami communicantes [85–91, 95–98, 106–111]. In the pelvic area, usually characterized as parasympathetic, these proximal locations of ganglionic cells also exist, both in sacral nerve roots [84, 93, 99] and in the proximal part of the pelvic splanchnic nerves [16, 17, 93, 112–114].

Distal locations

Neural crest cells can run aground anywhere along their proximo-distal migration pathways. Cell bodies of trunk neural crest cell origin are found up to the walls of the target organs, as the vascular system keeps instructing these cells to migrate [115, 116]. In the abdomen, cell bodies are found in large numbers in all splanchnic nerves [90, 98, 111, 117, 118], the preaortic ganglia [113, 114], all their periarterial extensions [119, 120], and within the walls of organs of both the urogenital and gastrointestinal tracts [114, 121–130]. In the thorax, the situation is similar. Catecholaminergic cell bodies are found on the cardiopulmonary nerves [131–134], in small mediastinal ganglia [131–134] and the ganglion cardiacum [135, 136], and within the wall of the heart [131, 134]. Finally, the distal position of cell bodies that are of trunk neural crest cell origin extends to the head. Several thousands of cell bodies exist, for example, along the intracranial course of human internal carotid arteries [110, 137–139].

(Catecholaminergic) cell bodies within the autonomic ganglia of the head are of mixed origin

The cell bodies within the cranial autonomic ganglia develop from neural crest cells and the related Schwann cell precursors [102, 140, 141], with the majority coming from Schwann cell precursors. Schwann cell precursors that are associated with the oculomotor nerve [8, 11, 141], chorda tympani [7, 10, 11], greater superficial petrosal nerve and geniculate ganglion [7, 10, 11], and tympanic nerve and petrosal ganglion [9–11] populate the ciliary, submandibular, pterygopalatine, and otic ganglia, respectively. Small ganglia are also present along these nerve paths [9–11]. In some species, including humans, at least part of these autonomic ganglia originate directly from cranial neural crest cells. These migrate along the ophthalmic [10, 11, 141–143], maxillary [11, 142], and mandibular nerves [11, 142], and also populate the ciliary, submandibular and pterygopalatine, and otic ganglia, respectively. Similarly, these trigeminal nerve branches also harbor small ganglia that represent grounded cell bodies [144, 145]. In addition, cells from the superior cervical ganglion were shown to populate the otic ganglion [10].

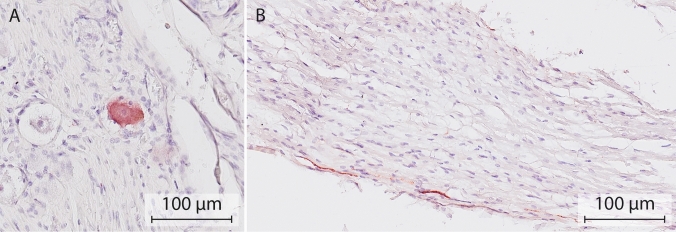

The partly catecholaminergic phenotype of the autonomic ganglia of the head may arise from cranial neural crest cells and Schwann cell precursors, as catecholaminergic cell bodies are present in both trigeminal [23, 24], and petrosal [26–37] and geniculate ganglia [25], respectively. Thus far, catecholaminergic cell bodies have not been reported to exist in the human geniculate ganglion, but here we demonstrate a few (Fig. 2). Of relevance, TH-positive neurons were also present in the proximal course of the greater superficial petrosal nerve. The notion that the partly catecholaminergic phenotype of the submandibular ganglion may arise from cranial neural crest cells is supported by the finding that catecholaminergic cell bodies in this ganglion are already present prior to the arrival of postganglionic neurons from the superior cervical ganglion [78].

Fig. 2.

Catecholaminergic neurons in the human geniculate ganglion and the greater superficial petrosal nerve. Example of a TH-positive cell body (A) and nerve fiber (B) in the geniculate ganglion and proximal course of the superficial petrosal nerve, respectively. Nerve tissue was harvested from a formalin-fixed cadaver (97 years of age) from the body donation program of the Department of Anatomy and Embryology, Maastricht University. The body was preserved by intra-arterial infusion with 10 L fixative (composition (v/v): 21% ethanol, 21% glycerin, 2% formaldehyde, 56% water, and 16 mmol/L thymol), followed by 4 weeks of fixation in 20% ethanol, 2% formaldehyde, and 78% water. Antibody: Abcam ab209487, 1:10,000. Antigen retrieval Tris–EDTA pH 9.0, 30 min. Secondary antibody GAR-bio, 1:10,000. Chromogen: Vector NovaRED peroxidase substrate kit, SK-4805

Caveats of using the catecholaminergic phenotype

In aggregate, our inventory convincingly shows that catecholaminergic fibers and cell bodies are present in the entire tracts of peripheral nerves and ganglia throughout the body. The reported prevalence of cell bodies per location varies greatly (supplemental interactive Table 1) [16, 18, 25, 27, 30–35, 37, 39, 41, 42, 44, 46, 51, 53, 54, 62–67, 71, 72, 74, 80, 122, 124, 126, 146–150]. We hypothesize that the reasons for this variation are both biological and technical. Most studies were not quantitative in design, because such studies would require random sampling of a sufficient number of histological sections across the entire structure of interest and, to deal with biological variation, a sufficient number of independent samples. In addition, the fraction of catecholaminergic cells that stain is influenced by such factors as the quality of the antibodies, the concentration of the neurotransmitter or enzyme, and the time between death and fixation. Even though it remains to be established what functions these cells have, their distribution pattern is too uncommon to dismiss as coincidental.

The catecholaminergic phenotype is not always associated with efferent (sympathetic) neurons, nor is it always permanent

Nerve cells with catecholaminergic phenotypic properties arise from the neural crest or the related Schwann cell precursor population. From these progenitors, different functional subtypes develop [151]. The catecholamines dopamine, noradrenaline, and adrenaline are derivates of phenylethylamine [152]. Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) is the first enzyme in the biosynthetic pathway of (nor)adrenaline. This enzyme has received the most attention in biomedical research [153], and is often, incorrectly, associated with (nor-)adrenergic neurotransmission. Co-localization of TH with dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH), which catalyzes the β-hydroxylation of dopamine to noradrenaline, provides stronger evidence for such neurotransmission. DBH-positive neurons have been reported in the ciliary [61, 66, 67], pterygopalatine [71], trigeminal [24, 49], petrosal [49], nodose [47, 49, 150], and dorsal root ganglia [49], and the vestibulocochlear [154, 155], vagus [80, 150], recurrent laryngeal [81], phrenic [120], and sciatic [55, 156–165] nerves. Other studies measured concentrations of noradrenaline directly in the trigeminal [166] and nodose [45] ganglia, and in the facial [167], vestibulocochlear [167, 168], vagus [166], phrenic [166], ilioinguinal [166], genitofemoral [166], sciatic [157, 163, 165, 169–174], and fibular [175] nerves and spinal nerve roots [166]. TH-positive, but DBH-negative cell bodies have been observed in ciliary [62, 64, 67], petrosal [31], jugular [31], nodose [31, 39] and dorsal root ganglia [31, 48, 51]. Furthermore, TH-positive, but noradrenaline transporter type-1- [57] and phenylethanolamine-N-methyl-transferase-negative cell bodies [31] were reported in dorsal root ganglia. Nerves in which solely TH but none of the downstream enzymes are present probably utilize dopamine as a neurotransmitter.

Tyrosine hydroxylase-positive staining has been observed in cell bodies that exhibit morphological features typical of primary sensory neurons in petrosal [26, 34], nodose [26, 34], geniculate [25], and dorsal root ganglia [56, 57, 59]. Some TH-positive cell bodies in the nodose ganglion are also labeled following the injection of tracer material into the nucleus of the solitary tract [39, 44].

Within the developing ciliary and pterygopalatine ganglia, neurons are observed that express catecholamines transiently [176–178]. In the mouse, the nerve fibers of the vagus nerve arrive in the wall of the gastrointestinal tract only after the TH-positive cells of the vagal neural crest cells have settled there [179, 180]. The TH-positive cells have largely disappeared from the vagus nerve by embryonic day 16 in the mouse, which corresponds to ~9.5 weeks of development in human embryos. Our observations suggest that a subset of these transiently TH-positive cells might remain present.

Arguments 2 and 3: The absence of white rami communicantes at the sacral level and the “lumbar gap”

Two other anatomical arguments that have been used to define the sympathetic-parasympathetic model are the absence of white rami communicantes at the sacral level, and the gap in the autonomic outflow at the lumbar level.

The rami communicantes are part of a peripheral connection matrix

Macroscopic studies of the distribution pattern of the rami communicantes and sympathetic trunk have shown that the rami communicantes form a true mesh, with up to seven rami communicantes connecting the sympathetic trunk with the spinal nerves from corresponding and adjacent levels [2, 94, 98, 181–184]. Interconnecting bundles of nerve fibers between the left and right sympathetic trunk are present at all levels [98, 185]. In addition, the white and gray rami communicantes can share an epineurium, and then present as a single ramus communicans [91].

Mixed content of white rami communicantes

The rami communicantes are defined by their macroscopic appearance [186, 187] which, in turn, depends on the proportion of myelinated nerve fibers present. Macroscopically identifiable white rami communicantes are present between vertebral levels T1 and L2 in humans. Accordingly, the absence of white rami communicantes at the sacral level has been one of the anatomical arguments for separating the sacral from the thoracolumbar autonomic outflow [1]. However, the nerve fibers in the rami communicantes represent not only preganglionic neurons, but also somatic neurons [87, 108, 188]. In addition, the white rami communicantes contain a great number of medium-sized and large myelinated afferent fibers, particularly in the lower thoracic region [189]. The number and size of these afferent fibers together far exceed the small myelinated efferent components, so that the white rami communicantes represent the thoracolumbar inflow as much as the outflow [189].

Mixed content of gray rami communicantes

Myelinated preganglionic neurons are also common in the gray ramus communicans [91, 95, 110, 190]. At the upper and lower margins of the thoracolumbar outflow, where the white rami communicantes gradually disappear, the number of myelinated nerve fibers in the gray rami communicantes actually increases tenfold [91, 108]. Sporadically, sacral gray rami communicantes are so heavily myelinated that they have been described as a “sacral white ramus communicans” [93].

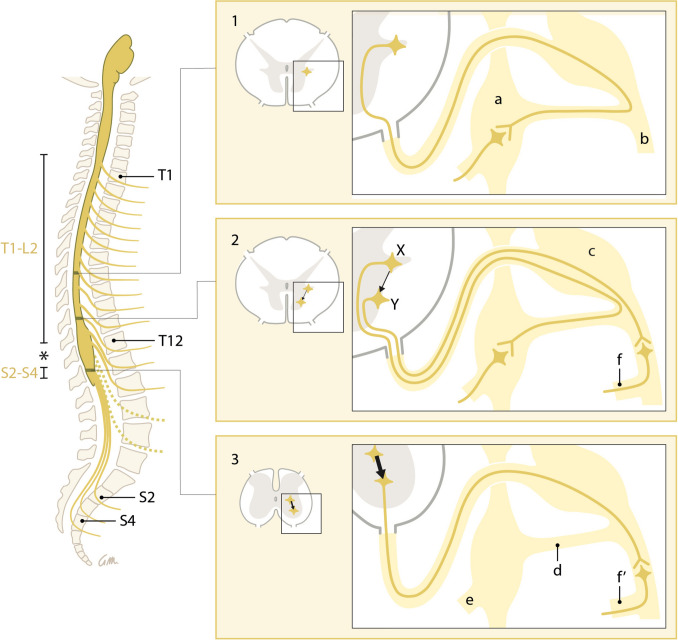

Preganglionic neurons can bypass the rami communicantes at the thoracolumbar outflow margins

At the margins of the thoracolumbar outflow, a fraction of the preganglionic neurons bypass the rami communicantes and the sympathetic trunk [86–90, 92, 96, 97, 110] (Fig. 3). Lumbar splanchnic nerves can arise directly from the lumbar plexus [90, 191], such as pelvic splanchnic nerves arise from the sacral plexus. Bypassing the sympathetic trunk, therefore, is not exclusive for the sacral outflow.

Fig. 3.

Cranio-caudal change in the position of the cell bodies and the course of the preganglionic neurons. Simplified representation. Left: Preganglionic outflow at the levels T1-L2 and S2-S4. The “lumbar gap” is indicated by an asterisk. Dashed outflow: preganglionic neurons within the “lumbar gap.” Right: From the lower margin of the thoracolumbar outflow downward (panel 1), a gradually increasing number (represented by arrow thickness) of preganglionic neurons originate from cell bodies within or near the ventral motor nuclei and bypass the sympathetic trunk (panels 2 and 3, neuron Y). Bypassing the sympathetic trunk, therefore, is not exclusive for the sacral outflow. Lumbar splanchnic nerves can arise directly from the lumbar plexus (Panel 2, f), such as pelvic splanchnic nerves arise from the sacral plexus (Panel 3, f′). Panels 1 and 2, neuron X: Classic representation of a preganglionic neuron with its cell body in the intermediolateral nucleus. Labels are identical in all panels; a: sympathetic trunk ganglion, b: spinal nerve, c: spinal ganglion, d: rami communicantes, e: splanchnic nerves

The lumbar gap

The spinal preganglionic outflow levels vary among species [1, 84, 92, 112, 186, 192]. In humans, the spinal preganglionic outflow has classically been confined to the segments T1-L2 and S2-S4 based on the absence of white rami communicantes caudal to segment L2, and on the perceived discontinuity of the spinal autonomic outflow cell column. The presence of this “lumbar gap” is often quoted when describing the parallel between the parasympathetic cranial and sacral outflows. Preganglionic neurons have been described, however, at the lower lumbar level [95, 137, 190], which is in the middle of the “lumbar gap.” These preganglionic neurons follow, as described in the previous paragraph, the spinal nerves and gray rami communicantes.

From the thoracolumbar outflow margin downwards, preganglionic cell bodies increasingly nest between the ventral motor nuclei [193, 194] (Fig. 3). At the sacral level, the intermediolateral nucleus no longer forms a distinct lateral horn of gray matter [194], whereas the ventral motor nucleus becomes highly mixed with preganglionic neurons [195]. Apparently, preganglionic neurons with their cell bodies in, or near, the ventral motor horn prefer to follow the path of the motor neurons and branch away towards their targets only distal to the white rami communicantes. At the sacral level, this phenomenon is structural, and the white ramus communicans is absent.

Conclusion

We conclude that the anatomy of the autonomic outflow displays a conserved architecture along the entire spinal axis, albeit with a gradient in characteristic features. Langley appears to have understood the limitations of the anatomical arguments that support his model, because he acknowledged the nonbinary distribution of postganglionic cell bodies [112, 196], the failure of the white-gray appearance of the rami communicantes to convey their anatomical identity, and the presence of preganglionic fibers in the gray rami communicantes and within the lumbar gap [190]. Although Langley created an appealing concept, his binary model was hallowed by constant repetition in the literature. As a result, the textbook presentation of the division of the spinal visceral outflow in sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions became primarily based on the generalization of this concept.

The conserved architecture of the spinal visceral outflow that is presented in this review seems to be compatible with the finding that the molecular signature of cells in the thoracolumbar and sacral region of the autonomic nervous system is qualitatively highly similar [5, 197].

Perspective

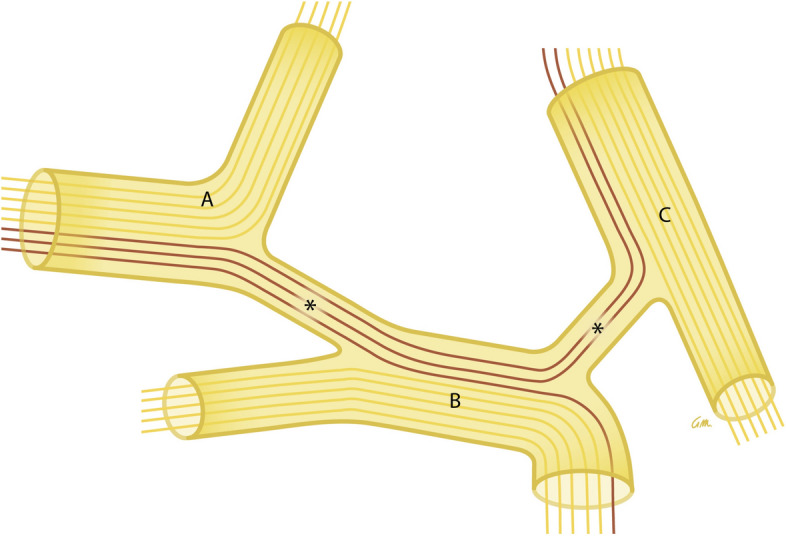

The development of the peripheral nervous system is intricate and diverse. Examples include the reciprocal interaction between neural crest cell migration and nerve formation. It is likely that neural crest cells with catecholaminergic fates emigrate from the CSN along pre-existing nerves to differentiate on their way and/or at their final target site. This might result in the entwined anatomy that we observed. Nerves and ganglia are therefore not homogeneous collections of neurons (Fig. 4). Upon migrating to a distal location, an appreciable number of these catecholaminergic cells apparently strand along the route. Such stranded cells could be very useful as left-behind markers of the migratory routes that were used. It is obvious that the mechanism underlying these cell decisions is of key importance and should be explored experimentally. The involvement of chemotaxis is probably a safe guess. Another intriguing question is whether the features now described for catecholaminergic cells also apply to other populations of nerve cells. If so, the CNS would prove an important source of the migratory nerve cells and the target site or cells an important attractant. It would make the wiring diagram complex and subject worthy of separate study, after identifying the source and target of the neural signals.

Fig. 4.

Scheme of neurons using two or more nerves to reach their target organ. Neuronal function is not strictly coupled to specific nerves: neurons change course (purple) from nerve A to nerve B and C via communicating nerve branches (asterisks). This behavior could fit a still hypothetical peripheral connectome

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Abbreviations

- Important note

Nerves and ganglia are not homogeneous collections of neurons. Nerves and ganglia themselves therefore are not exclusively sympathetic, parasympathetic, or somatic. For example, the white and gray rami communicantes are not dedicated “sympathetic nerves,” just as the vagus nerves are not exclusively “parasympathetic,” or the spinal ganglia “somatic.”

- Neuron

Nerve cell

- Cell body (soma, perikaryon)

Part of neuron containing the cell nucleus

- Nucleus

Collection of cell bodies in the central nervous system

- Nerve fiber

Extension of the neuron that propagates the electrochemical stimulus from (axon) or to (dendrite) the cell body

- Preganglionic neuron (visceral efferent neuron)

Autonomic neuron with its cell body in the central nervous system

- Postganglionic neuron

Autonomic neuron with its cell body in the peripheral nervous system

- Autonomic outflow (visceral outflow)

The group of preganglionic neurons leaving the central nervous system at a certain level

- Ganglion

Collection of cell bodies in the peripheral nervous system

- Nerve

The nerve fibers and cell bodies that are embedded in connective tissue called epineurium

- Nerve branch

Branched extension of a nerve

- Sympathetic trunk, also known as paravertebral ganglionic chain

Collection of nerves and ganglia located on either side of the vertebral column

- Preaortic (prevertebral) ganglia

Collection of nerves and ganglia located ventral to the abdominal aorta

- Pelvic ganglion (inferior hypogastric plexus)

Collection of nerves and ganglia located in the pelvic wall

Author contributions

TV: conception & design, data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing. AH: conception & design, data analysis and interpretation. WH: conception & design, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing. SEK: conception & design, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript revision.

Funding

The research did not receive any funding.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no financial or non-financial conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Langley JN. The autonomic nervous system, Part I. Cambridge: W. HEFFER & SONS LTD.; 1921. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Standring S Gray’s Anatomy, The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. 41st Revised ed. 2016: Elsevier Health Sciences.

- 3.W.F., B. and B. E.L., Medical Physiology. 3 ed. 2016: Elsevier Health Science Division.

- 4.F.I.P.A.T., Terminologia Neuroanatomica 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Espinosa-Medina I, et al. The sacral autonomic outflow is sympathetic. Science. 2016;354(6314):893–897. doi: 10.1126/science.aah5454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.F.C.o.A.T., Terminologia anatomica: International anatomical terminology. 2011, Stuttgart: Thieme Publishing Group.

- 7.Coppola E, et al. Epibranchial ganglia orchestrate the development of the cranial neurogenic crest. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(5):2066–2071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910213107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dyachuk, V., et al., Neurodevelopment. Parasympathetic neurons originate from nerve-associated peripheral glial progenitors. Science, 2014. 345(6192): p. 82–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Espinosa-Medina, I., et al., Neurodevelopment. Parasympathetic ganglia derive from Schwann cell precursors. Science, 2014. 345(6192): p. 87–90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Stewart FW. The development of the cranial sympathetic ganglia in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1919;31(3):163–217. doi: 10.1002/cne.900310302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuntz A. The development of the sympathetic nervous system in man. J Comp Neurol. 1920;32(2):173–229. doi: 10.1002/cne.900320204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson JE. Sympathetic pathways through the petrosal nerves in monkeys. Acta Anat (Basel) 1985;121(2):75–80. doi: 10.1159/000145946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matthews B, Robinson PP. The course of postganglionic sympathetic fibres distributed with the facial nerve in the cat. Brain Res. 1986;382(1):55–60. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90110-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shibamori Y, et al. The trajectory of the sympathetic nerve fibers to the rat cochlea as revealed by anterograde and retrograde WGA-HRP tracing. Brain Res. 1994;646(2):223–229. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maklad A, Quinn T, Fritzsch B. Intracranial distribution of the sympathetic system in mice: DiI tracing and immunocytochemical labeling. Anat Rec. 2001;263(1):99–111. doi: 10.1002/ar.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takenaka A et al. (2005) Interindividual variation in distribution of extramural ganglion cells in the male pelvis: a semi-quantitative and immunohistochemical study concerning nerve-sparing pelvic surgery. Eur Urol 48(1): p. 46–52; discussion 52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Imai K, et al. Human pelvic extramural ganglion cells: a semiquantitative and immunohistochemical study. Surg Radiol Anat. 2006;28(6):596–605. doi: 10.1007/s00276-006-0156-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jang HS, et al. Composite nerve fibers in the hypogastric and pelvic splanchnic nerves: an immunohistochemical study using elderly cadavers. Anat Cell Biol. 2015;48(2):114–123. doi: 10.5115/acb.2015.48.2.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verberne ME, et al. Contribution of the cervical sympathetic ganglia to the innervation of the pharyngeal arch arteries and the heart in the chick embryo. Anat Rec. 1999;255(4):407–419. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(19990801)255:4<407::AID-AR7>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schrodl F, et al. Intrinsic neurons in the duck choroid are contacted by CGRP-immunoreactive nerve fibres: evidence for a local pre-central reflex arc in the eye. Exp Eye Res. 2001;72(2):137–146. doi: 10.1006/exer.2000.0940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagatsu I, et al. Immunofluorescent and biochemical studies on tyrosine hydroxylase and dopamine-beta-hydroxylase of the bullfrog sciatic nerves. Histochemistry. 1979;61(2):103–109. doi: 10.1007/BF00496522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rigon F, et al. Effects of sciatic nerve transection on ultrastructure, NADPH-diaphorase reaction and serotonin-, tyrosine hydroxylase-, c-Fos-, glucose transporter 1- and 3-like immunoreactivities in frog dorsal root ganglion. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2013;46(6):513–520. doi: 10.1590/1414-431X20132853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marfurt CF, Ellis LC. Immunohistochemical localization of tyrosine hydroxylase in corneal nerves. J Comp Neurol. 1993;336(4):517–531. doi: 10.1002/cne.903360405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reynolds AJ, Kaasinen SK, Hendry IA. Retrograde axonal transport of dopamine beta hydroxylase antibodies by neurons in the trigeminal ganglion. Neurochem Res. 2005;30(6–7):703–712. doi: 10.1007/s11064-005-6864-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang, T. and B.A. Pierchala, Oral Sensory Neurons of the Geniculate Ganglion That Express Tyrosine Hydroxylase Comprise a Subpopulation That Contacts Type II and Type III Taste Bud Cells. eNeuro, 2022. 9(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Katz DM, et al. Expression of catecholaminergic characteristics by primary sensory neurons in the normal adult rat in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80(11):3526–3530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.11.3526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katz DM, Black IB. Expression and regulation of catecholaminergic traits in primary sensory neurons: relationship to target innervation in vivo. J Neurosci. 1986;6(4):983–989. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-04-00983.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katz DM, Adler JE, Black IB. Catecholaminergic primary sensory neurons: autonomic targets and mechanisms of transmitter regulation. Fed Proc. 1987;46(1):24–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Helke CJ, Niederer AJ. Studies on the coexistence of substance P with other putative transmitters in the nodose and petrosal ganglia. Synapse. 1990;5(2):144–151. doi: 10.1002/syn.890050209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katz DM, Erb MJ. Developmental regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase expression in primary sensory neurons of the rat. Dev Biol. 1990;137(2):233–242. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(90)90250-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kummer W, et al. Catecholamines and catecholamine-synthesizing enzymes in guinea-pig sensory ganglia. Cell Tissue Res. 1990;261(3):595–606. doi: 10.1007/BF00313540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Helke CJ, Rabchevsky A. Axotomy alters putative neurotransmitters in visceral sensory neurons of the nodose and petrosal ganglia. Brain Res. 1991;551(1–2):44–51. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90911-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ichikawa H, Rabchevsky A, Helke CJ. Presence and coexistence of putative neurotransmitters in carotid sinus baro- and chemoreceptor afferent neurons. Brain Res. 1993;611(1):67–74. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91778-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ichikawa H, Helke CJ. Parvalbumin and calbindin D-28k in vagal and glossopharyngeal sensory neurons of the rat. Brain Res. 1995;675(1–2):337–341. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00071-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ichikawa H, Helke CJ. Coexistence of s100beta and putative transmitter agents in vagal and glossopharyngeal sensory neurons of the rat. Brain Res. 1998;800(2):312–318. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(98)00511-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang ZY, et al. Expression of 5-HT3 receptors in primary sensory neurons of the petrosal ganglion of adult rats. Auton Neurosci. 2002;95(1–2):121–124. doi: 10.1016/S1566-0702(01)00384-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ichikawa H, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor-immunoreactive neurons in the rat vagal and glossopharyngeal sensory ganglia; co-expression with other neurochemical substances. Brain Res. 2007;1155:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kawagishi K, et al. Tyrosine hydroxylase-immunoreactive fibers in the human vagus nerve. J Clin Neurosci. 2008;15(9):1023–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2007.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kummer W, et al. Tyrosine-hydroxylase-containing vagal afferent neurons in the rat nodose ganglion are independent from neuropeptide-Y-containing populations and project to esophagus and stomach. Cell Tissue Res. 1993;271(1):135–144. doi: 10.1007/BF00297551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoshida Y, et al. Ganglions and ganglionic neurons in the cat's larynx. Acta Otolaryngol. 1993;113(3):415–420. doi: 10.3109/00016489309135837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhuo H, Sinclair C, Helke CJ. Plasticity of tyrosine hydroxylase and vasoactive intestinal peptide messenger RNAs in visceral afferent neurons of the nodose ganglion upon axotomy-induced deafferentation. Neuroscience. 1994;63(2):617–626. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90555-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhuo H, et al. Inhibition of axoplasmic transport in the rat vagus nerve alters the numbers of neuropeptide and tyrosine hydroxylase messenger RNA-containing and immunoreactive visceral afferent neurons of the nodose ganglion. Neuroscience. 1995;66(1):175–187. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00561-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ichikawa H, Helke CJ. Coexistence of calbindin D-28k and NADPH-diaphorase in vagal and glossopharyngeal sensory neurons of the rat. Brain Res. 1996;735(2):325–329. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00798-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uno T, et al. Tyrosine hydroxylase-immunoreactive cells in the nodose ganglion for the canine larynx. NeuroReport. 1996;7(8):1373–1376. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199605310-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gorbunova AV. Catecholamines in rabbit nodose ganglion following exposure to an acute emotional stressor. Stress. 1998;2(3):231–236. doi: 10.3109/10253899809167287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sang Q, Young HM. The origin and development of the vagal and spinal innervation of the external muscle of the mouse esophagus. Brain Res. 1998;809(2):253–268. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(98)00893-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bookout AL, Gautron L. Characterization of a cell bridge variant connecting the nodose and superior cervical ganglia in the mouse: Prevalence, anatomical features, and practical implications. J Comp Neurol. 2021;529(1):111–128. doi: 10.1002/cne.24936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Price J, Mudge AW. A subpopulation of rat dorsal root ganglion neurones is catecholaminergic. Nature. 1983;301(5897):241–243. doi: 10.1038/301241a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jonakait GM, et al. Transient expression of selected catecholaminergic traits in cranial sensory and dorsal root ganglia of the embryonic rat. Dev Biol. 1984;101(1):51–60. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(84)90116-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Price J. An immunohistochemical and quantitative examination of dorsal root ganglion neuronal subpopulations. J Neurosci. 1985;5(8):2051–2059. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-08-02051.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vega JA, et al. Presence of catecholamine-related enzymes in a subpopulation of primary sensory neurons in dorsal root ganglia of the rat. Cell Mol Biol. 1991;37(5):519–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Holmberg K, et al. Effect of peripheral nerve lesion and lumbar sympathectomy on peptide regulation in dorsal root ganglia in the NGF-overexpressing mouse. Exp Neurol. 2001;167(2):290–303. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ichikawa H, et al. Brn-3a deficiency increases tyrosine hydroxylase-immunoreactive neurons in the dorsal root ganglion. Brain Res. 2005;1036(1–2):192–195. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brumovsky P, Villar MJ, Hokfelt T. Tyrosine hydroxylase is expressed in a subpopulation of small dorsal root ganglion neurons in the adult mouse. Exp Neurol. 2006;200(1):153–165. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dina OA, et al. Neurotoxic catecholamine metabolite in nociceptors contributes to painful peripheral neuropathy. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;28(6):1180–1190. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06425.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li L, et al. The functional organization of cutaneous low-threshold mechanosensory neurons. Cell. 2011;147(7):1615–1627. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brumovsky PR, et al. Dorsal root ganglion neurons innervating pelvic organs in the mouse express tyrosine hydroxylase. Neuroscience. 2012;223:77–91. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCarthy CJ, et al. Axotomy of tributaries of the pelvic and pudendal nerves induces changes in the neurochemistry of mouse dorsal root ganglion neurons and the spinal cord. Brain Struct Funct. 2016;221(4):1985–2004. doi: 10.1007/s00429-015-1019-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Oroszova Z, et al. The Characterization of AT1 Expression in the Dorsal Root Ganglia After Chronic Constriction Injury. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2017;37(3):545–554. doi: 10.1007/s10571-016-0396-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Iacovitti L, et al. Partial expression of catecholaminergic traits in cholinergic chick ciliary ganglia: studies in vivo and in vitro. Dev Biol. 1985;110(2):402–412. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(85)90099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Landis SC, et al. Catecholaminergic properties of cholinergic neurons and synapses in adult rat ciliary ganglion. J Neurosci. 1987;7(11):3574–3587. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-11-03574.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Uemura Y, et al. Tyrosine hydroxylase-like immunoreactivity and catecholamine fluorescence in ciliary ganglion neurons. Brain Res. 1987;416(1):200–203. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91519-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tyrrell S, Siegel RE, Landis SC. Tyrosine hydroxylase and neuropeptide Y are increased in ciliary ganglia of sympathectomized rats. Neuroscience. 1992;47(4):985–998. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kirch W, Neuhuber W, Tamm ER. Immunohistochemical localization of neuropeptides in the human ciliary ganglion. Brain Res. 1995;681(1–2):229–234. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00299-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tan CK, Zhang YL, Wong WC. A light- and electron microscopic study of tyrosine hydroxylase-like immunoreactivity in the ciliary ganglia of monkey (Macaca fascicularis) and cat. Histol Histopathol. 1995;10(1):27–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Grimes PA, et al. Neuropeptide Y-like immunoreactivity localizes to preganglionic axon terminals in the rhesus monkey ciliary ganglion. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39(2):227–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kaleczyc J, et al. Immunohistochemical characterization of neurons in the porcine ciliary ganglion. Pol J Vet Sci. 2005;8(1):65–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thakker MM, et al. Human orbital sympathetic nerve pathways. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;24(5):360–366. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181837a11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kiyokawa H, et al. Reconsideration of the autonomic cranial ganglia: an immunohistochemical study of mid-term human fetuses. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2012;295(1):141–149. doi: 10.1002/ar.21516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kuwayama Y, Emson PC, Stone RA. Pterygopalatine ganglion cells contain neuropeptide Y. Brain Res. 1988;446(2):219–224. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90880-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Simons E, Smith PG. Sensory and autonomic innervation of the rat eyelid: neuronal origins and peptide phenotypes. J Chem Neuroanat. 1994;7(1–2):35–47. doi: 10.1016/0891-0618(94)90006-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Szczurkowski A, et al. Morphology and immunohistochemical characteristics of the pterygopalatine ganglion in the chinchilla (Chinchilla laniger, Molina) Pol J Vet Sci. 2013;16(2):359–368. doi: 10.2478/pjvs-2013-0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Soinila J, et al. Met5-enkephalin-Arg6-Gly7-Leu8-immunoreactive nerve fibers in the major salivary glands of the rat: evidence for both sympathetic and parasympathetic origin. Cell Tissue Res. 1991;264(1):15–22. doi: 10.1007/BF00305718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shida T, et al. Enkephalinergic sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation of the rat submandibular and sublingual glands. Brain Res. 1991;555(2):288–294. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90354-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ng YK, Wong WC, Ling EA. A study of the structure and functions of the submandibular ganglion. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1995;24(6):793–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hosaka F, et al. Site-dependent differences in density of sympathetic nerve fibers in muscle-innervating nerves of the human head and neck. Anat Sci Int. 2014;89(2):101–111. doi: 10.1007/s12565-013-0205-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yamauchi M, et al. Sympathetic and parasympathetic neurons are likely to be absent in the human vestibular and geniculate ganglia: an immunohistochemical study using elderly cadaveric specimens. Okajimas Folia Anat Jpn. 2016;93(1):1–4. doi: 10.2535/ofaj.93.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Teshima THN, Tucker AS, Lourenco SV. Dual sympathetic input into developing salivary glands. J Dent Res. 2019;98(10):1122–1130. doi: 10.1177/0022034519865222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Oda K, et al. A ganglion cell cluster along the glossopharyngeal nerve near the human palatine tonsil. Acta Otolaryngol. 2013;133(5):509–512. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2012.754997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Verlinden TJM, et al. Morphology of the human cervical vagus nerve: implications for vagus nerve stimulation treatment. Acta Neurol Scand. 2016;133(3):173–182. doi: 10.1111/ane.12462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dahlqvist A, Forsgren S. Expression of catecholamine-synthesizing enzymes in paraganglionic and ganglionic cells in the laryngeal nerves of the rat. J Neurocytol. 1992;21(1):1–6. doi: 10.1007/BF01206893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ibanez M, et al. Human laryngeal ganglia contain both sympathetic and parasympathetic cell types. Clin Anat. 2010;23(6):673–682. doi: 10.1002/ca.20956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tubbs RS, et al. The existence of hypoglossal root ganglion cells in adult humans: potential clinical implications. Surg Radiol Anat. 2009;31(3):173–176. doi: 10.1007/s00276-008-0422-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Harman NB. The pelvic splanchnic nerves: an examination into their range and character. J Anat Physiol. 1899;33(3):386–412. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Marinesco G. Über die mikro-sympathischen hypospinalen Ganglien. Neurol Zbl. 1908;27:146–150. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Skoog T. Ganglia in the communicating rami of the cervical sympathetic trunk. Lancet. 1947;2(6474):457–460. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(47)90473-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Alexander WF, et al. Sympathetic conduction pathways independent of sympathetic trunks; their surgical implications. J Int Coll Surg. 1949;12(2):111–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Alexander WF, et al. Sympathetic ganglion cells in ventral nerve roots. Their Relation to sympathectomy Science. 1949;109(2837):484. doi: 10.1126/science.109.2837.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kuntz, A. and A. W.F., Surgical implicantions of lower thoracic and lumbar independent sympathetic pathways. AMA Arch Surg, 1950. 61(6): p. 1007–18. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 90.Webber RH. An analysis of the sympathetic trunk, communicating rami, sympathetic roots and visceral rami in the lumbar region in man. Ann Surg. 1955;141(3):398–413. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195503000-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kuntz, A., H. H.H., and J. M.W., Nerve fiber components of communicating rami and sympathetic roots in man. Anat Rec, 1956. 126(1): p. 29–41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 92.Pick J. The identification of sympathetic segments. Ann Surg. 1957;145(3):355–364. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195703000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kimmel DL, McCrea LE. The development of the pelvic plexuses and the distribution of the pelvic splanchnic nerves in the human embryo and fetus. J Comp Neurol. 1958;110(2):271–297. doi: 10.1002/cne.901100207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wrete M. The anatomy of the sympathetic trunks in man. J Anat. 1959;93:448–459. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Webber RH, et al. Myelinated nerve fibers in communicating rami attached to caudal lumbar nerves. J Comp Neurol. 1962;119:11–20. doi: 10.1002/cne.901190103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Webber, R.H. and W. A., Distribution of fibers from nerve cell bodies in ventral roots of spinal nerves. Acta Anat 1966. 65(4): p. 579–83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 97.Webber RH. Accessory ganglia related to sympathetic nerves in the lumbar region. Acta Anat. 1967;66(1):59–66. doi: 10.1159/000142915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Baljet B, Boekelaar AB, Groen GJ. Retroperitoneal paraganglia and the peripheral autonomic nervous system in the human fetus. Acta Morphol Neerl Scand. 1985;23(2):137–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Massrey C, et al. Ectopic sympathetic ganglia cells of the ventral root of the spinal cord: an anatomical study. Anat Cell Biol. 2020;53(1):15–20. doi: 10.5115/acb.19.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Jessen KR, Mirsky R. Schwann cell precursors and their development. Glia. 1991;4(2):185–194. doi: 10.1002/glia.440040210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Serbedzija GN, McMahon AP. Analysis of neural crest cell migration in Splotch mice using a neural crest-specific LacZ reporter. Dev Biol. 1997;185(2):139–147. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lefcort F. Development of the Autonomic Nervous System: Clinical Implications. Semin Neurol. 2020;40(5):473–484. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1713926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kasemeier-Kulesa JC, et al. CXCR4 controls ventral migration of sympathetic precursor cells. J Neurosci. 2010;30(39):13078–13088. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0892-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kruepunga N, et al. Development of extrinsic innervation in the abdominal intestines of human embryos. J Anat. 2020;237(4):655–671. doi: 10.1111/joa.13230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kasemeier-Kulesa JC, Kulesa PM, Lefcort F. Imaging neural crest cell dynamics during formation of dorsal root ganglia and sympathetic ganglia. Development. 2005;132(2):235–245. doi: 10.1242/dev.01553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Marinesco GMJ (1908) Über die mikro-sympathischen hypospinalen Ganglien. Neurol Zbl 27: 146–150.

- 107.Gruss W. Über Ganglien im Ramus communicans. Z Anat Entwickl Gesch. 1932;97:464–471. doi: 10.1007/BF02118282. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Pick J, Sheehan D (1946) Sympathetic rami in man. J Anat. 80(Pt 1): 12–20 3. [PubMed]

- 109.Wrete M. Ganglia of rami communicantes in man and mammals particularly monkey. Acta Anat (Basel) 1951;13(3):329–336. doi: 10.1159/000140578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hoffman HH. An analysis of the sympathetic trunk and rami in the cervical and upper thoracic regions in man. Ann Surg. 1957;145(1):94–103. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195701000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Webber RH. A contribution on the sympathetic nerves in the lumbar region. Anat Rec. 1958;130(3):581–604. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091300309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Langley JN, AHK (1896) The innervation of the pelvic and adjoining viscera. Part VII Anatomical observations. J Physiol 20(4–5): p. 372–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 113.Dail WG, Evan AP, Eason HR. The major ganglion in the pelvic plexus of the male rat: a histochemical and ultrastructural study. Cell Tissue Res. 1975;159(1):49–62. doi: 10.1007/BF00231994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kuntz A, Moseley RL. An experimental analysis of the pelvic autonomic ganglia in the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1935;64(1):63–75. doi: 10.1002/cne.900640104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Makita T, et al. Endothelins are vascular-derived axonal guidance cues for developing sympathetic neurons. Nature. 2008;452(7188):759–763. doi: 10.1038/nature06859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Takahashi Y, Sipp D, Enomoto H. Tissue interactions in neural crest cell development and disease. Science. 2013;341(6148):860–863. doi: 10.1126/science.1230717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kuntz A. Components of splanchnic and intermesenteric nerves. J Comp Neurol. 1956;105(2):251–268. doi: 10.1002/cne.901050205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kuntz A, Hoffman HH, Schaeffer EM. Fiber components of the splanchnic nerves. Anat Rec. 1957;128(1):139–146. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091280111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kuntz A, Jacobs MW. Components of periarterial extensions of celiac and mesenteric plexuses. Anat Rec. 1955;123(4):509–520. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091230409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Verlinden TJM, et al. The human phrenic nerve serves as a morphological conduit for autonomic nerves and innervates the caval body of the diaphragm. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):11697. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-30145-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.El-Badawi A, Schenk EA. The peripheral adrenergic innervation apparatus. Z Zellforsch. 1968;87:218–225. doi: 10.1007/BF00319721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Morris JL, Gibbins IL. Neuronal colocalization of peptides, catecholamines, and catecholamine-synthesizing enzymes in guinea pig paracervical ganglia. J Neurosci. 1987;7(10):3117–3130. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-10-03117.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.James S, Burnstock G. Neuropeptide Y-like immunoreactivity in intramural ganglia of the newborn guinea pig urinary bladder. Regul Pept. 1988;23(2):237–245. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(88)90031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Houdeau E, et al. Distribution of noradrenergic neurons in the female rat pelvic plexus and involvement in the genital tract innervation. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1995;54(2):113–125. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(95)00014-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Smet PJ, et al. Neuropeptides and neurotransmitter-synthesizing enzymes in intrinsic neurons of the human urinary bladder. J Neurocytol. 1996;25(2):112–124. doi: 10.1007/BF02284790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Dixon JS, Jen PY, Gosling JA. A double-label immunohistochemical study of intramural ganglia from the human male urinary bladder neck. J Anat. 1997;190(Pt 1):125–134. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.1997.19010125.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Werkstrom V, et al. Inhibitory innervation of the guinea-pig urethra; roles of CO, NO and VIP. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1998;74(1):33–42. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1838(98)00135-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Dixon JS, Jen PY, Gosling JA. Tyrosine hydroxylase and vesicular acetylcholine transporter are coexpressed in a high proportion of intramural neurons of the human neonatal and child urinary bladder. Neurosci Lett. 1999;277(3):157–160. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(99)00877-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Muraoka K, et al. Site-dependent differences in the composite fibers of male pelvic plexus branches: an immunohistochemical analysis of donated elderly cadavers. BMC Urol. 2018;18(1):47. doi: 10.1186/s12894-018-0369-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Arellano J, et al. Neural interrelationships of autonomic ganglia from the pelvic region of male rats. Auton Neurosci. 2019;217:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2018.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Armour JA, Hopkins DA. Localization of sympathetic postganglionic neurons of physiologically identified cardiac nerves in the dog. J Comp Neurol. 1981;202(2):169–184. doi: 10.1002/cne.902020204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Armour JA. Physiological studies of small mediastinal ganglia in the cardiopulmonary nerves of dogs. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1984;62(9):1244–1248. doi: 10.1139/y84-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Hopkins DA, Armour JA. Localization of sympathetic postganglionic and parasympathetic preganglionic neurons which innervate different regions of the dog heart. J Comp Neurol. 1984;229(2):186–198. doi: 10.1002/cne.902290205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Janes RD, et al. Anatomy of human extrinsic cardiac nerves and ganglia. Am J Cardiol. 1986;57(4):299–309. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(86)90908-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Hoard JL, et al. Cholinergic neurons of mouse intrinsic cardiac ganglia contain noradrenergic enzymes, norepinephrine transporters, and the neurotrophin receptors tropomyosin-related kinase A and p75. Neuroscience. 2008;156(1):129–142. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.06.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Kim JH, et al. Ganglion cardiacum or juxtaductal body of human fetuses. Anat Cell Biol. 2018;51(4):266–273. doi: 10.5115/acb.2018.51.4.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Mitchell GAG. The cranial extremities of the sympathetic trunks. Acta Anat. 1953;18:195–201. doi: 10.1159/000140834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Kuntz A, Hoffman HH, Napolitano LM. Cephalic sympathetic nerves. Arch Surg. 1957;75:108–115. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1957.01280130112019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Tubbs RS, et al. Does the ganglion of Ribes exist? Folia Neuropathol. 2006;44(3):197–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Schaper A. The earliest differentiation in the central nervous system of vertebrates. Science. 1897;5(115):430–431. [Google Scholar]

- 141.Carpenter FW. The development of the oculomotor nerve, the ciliary ganglion and the abducent nerve in the chick. Bull Mus Comp Zool Harvard College. 1906;48:141–228. [Google Scholar]

- 142.Streeter, G.L., Manual of Human Embryology The development of the nervous system. Vol. 2. 1912: Keibel and Mall.

- 143.Young HM, Cane KN, Anderson CR. Development of the autonomic nervous system: a comparative view. Auton Neurosci. 2011;165(1):10–27. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Andres KH, Kautzky R. Die Frühentwicklung der vegetativen Hals- und Kopfganglien des Menschen. Z Anat Entwicklungsgesch. 1955;119:55–84. doi: 10.1007/BF00529407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Andres KH, Kautzky R. Kleine vegetative Ganglien im Bereich der Schädelbasis des Menschen. Deutsche Zeitschrift f Nervenheilkunde. 1956;174:272–282. doi: 10.1007/BF00243354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Castro J, Negredo P, Avendano C. Fiber composition of the rat sciatic nerve and its modification during regeneration through a sieve electrode. Brain Res. 2008;1190:65–77. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Loesch A, et al. Sciatic nerve of diabetic rat treated with epoetin delta: effects on C-fibers and blood vessels including pericytes. Angiology. 2010;61(7):651–668. doi: 10.1177/0003319709360030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Tompkins, R.P., et al., Arrangement of sympathetic fibers within the human common peroneal nerve: implications for microneurography. J Appl Physiol (1985), 2013. 115(10): p. 1553–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 149.Creze M, et al. Functional and structural microanatomy of the fetal sciatic nerve. Muscle Nerve. 2017;56(4):787–796. doi: 10.1002/mus.25531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Yang M, Zhao X, Miselis RR. The origin of catecholaminergic nerve fibers in the subdiaphragmatic vagus nerve of rat. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1999;76(2–3):108–117. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1838(99)00014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Kastriti ME, et al. Schwann cell precursors represent a neural crest-like state with biased multipotency. EMBO J. 2022;41(17):e108780. doi: 10.15252/embj.2021108780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Molinoff PB, Axelrod J. Biochemistry of catecholamines. Annu Rev Biochem. 1971;40:465–500. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.40.070171.002341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Daubner SC, Le T, Wang S. Tyrosine hydroxylase and regulation of dopamine synthesis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2011;508(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Hozawa K, Kimura RS. Cholinergic and noradrenergic nervous systems in the cynomolgus monkey cochlea. Acta Otolaryngol. 1990;110(1–2):46–55. doi: 10.3109/00016489009122514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Hozawa K, Takasaka T. Catecholaminergic innervation in the vestibular labyrinth and vestibular nucleus of guinea pigs. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1993;503:111–113. doi: 10.3109/00016489309128089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Dairman W, Geffen L, Marchelle M (1973) Axoplasmic transport of aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (EC 4.1.1.26) and dopamine beta-hydroxylase (EC 1.14.2.1) in rat sciatic nerve. J Neurochem 20(6): 1617–23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 157.Keen P, McLean WG. The effect of nerve stimulation on the axonal transport of noradrenaline and dopamine-beta-hydroxylase. Br J Pharmacol. 1974;52(4):527–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1974.tb09720.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Nagatsu I, Hartman BK, Udenfriend S. The anatomical characteristics of dopamine-beta-hydroxylase accumulation in ligated sciatic nerve. J Histochem Cytochem. 1974;22(11):1010–1018. doi: 10.1177/22.11.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Reid JL, Kopin IJ. The effects of ganglionic blockade, reserpine and vinblastine on plasma catecholamines and dopamine-beta-hydroxylase in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1975;193(3):748–756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Haggendal J. Axonal transport of dopamine-beta-hydroxylase to rat salivary glands: studies on enzymatic activity. J Neural Transm. 1980;47(3):163–174. doi: 10.1007/BF01250598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Jakobsen J, Brimijoin S. Axonal transport of enzymes and labeled proteins in experimental axonopathy induced by p-bromophenylacetylurea. Brain Res. 1981;229(1):103–122. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90749-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Evers-Von Bultzingslowen I, Haggendal J (1983) Disappearance of noradrenaline from different parts of the rabbit external ear following superior cervical ganglionectomy. J Neural Transm 56(2–3): 117–26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 163.Larsson PA, Goldstein M, Dahlstrom A. A new methodological approach for studying axonal transport: cytofluorometric scanning of nerves. J Histochem Cytochem. 1984;32(1):7–16. doi: 10.1177/32.1.6197439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Schmidt RE, Modert CW. Orthograde, retrograde, and turnaround axonal transport of dopamine-beta-hydroxylase: response to axonal injury. J Neurochem. 1984;43(3):865–870. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1984.tb12810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Larsson PA, et al. Reserpine-induced effects in the adrenergic neuron as studied with cytofluorimetric scanning. Brain Res Bull. 1986;16(1):63–74. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(86)90013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Lackovic Z, et al. Dopamine and its metabolites in human peripheral nerves: is there a widely distributed system of peripheral dopaminergic nerves? Life Sci. 1981;29(9):917–922. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(81)90393-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Anniko M, Pequignot JM (1987) Catecholamine content of cochlear and facial nerves. High-performance liquid chromatography analyses in normal and mutant mice. Arch Otorhinolaryngol 244(5): 262–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 168.Densert O. A fluorescence and electron microscopic study of the adrenergic innervation in the vestibular ganglion and sensory areas. Acta Otolaryngol. 1975;79(1–2):96–107. doi: 10.3109/00016487509124660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Nielsen KC, Owman C, Santini M. Anastomosing adrenergic nerves from the sympathetic trunk to the vagus at the cervical level in the cat. Brain Res. 1969;12(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(69)90050-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Dahlstrom A, et al. Cytofluorimetric scanning: a tool for studying axonal transport in monoaminergic neurons. Brain Res Bull. 1982;9(1–6):61–68. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(82)90121-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Dahlqvist A, et al. Catecholamines of endoneurial laryngeal paraganglia in the rat. Acta Physiol Scand. 1986;127(2):257–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1986.tb07901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Dahlstrom A, et al. Immunocytochemical studies on axonal transport in adrenergic and cholinergic nerves using cytofluorimetric scanning. Med Biol. 1986;64(2–3):49–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]