Abstract

Deprescribing is the intentional dose reduction or discontinuation of a medication. The development of deprescribing interventions should take into consideration important organizational, interprofessional, and patient-specific barriers that can be further complicated by the presence of multiple prescribers involved in a patient’s care. Patients who receive care from an increasing number of prescribers may experience disruptions in the timely transfer of relevant healthcare information, increasing the risk for exposure to drug-drug interactions and other medication-related problems. Furthermore, the fragmentation of healthcare information across health systems can contribute to the refilling of discontinued medications, reducing the effectiveness of deprescribing interventions. Thus, deprescribing interventions must carefully consider the unique characteristics of patients and their prescribers to ensure interventions are successfully implemented. In this special article an international working group of physicians, pharmacists, nurses, epidemiologists, and researchers from the United States Deprescribing Research Network (USDeN) developed a socioecological model to understand how multiple prescribers may influence the implementation of a deprescribing intervention at the individual, interpersonal, organizational, and societal level. This manuscript also includes a description of the concept of multiple prescribers and outlines a research agenda for future investigations to consider. The information contained in this manuscript should be used as a framework for future deprescribing interventions to carefully consider how multiple prescribers can influence the successful implementation of the service and ensure the intervention is as effective as possible.

Keywords: deprescribing, multiple prescribers, multiple chronic conditions, medication-related problems, polypharmacy, continuity of care

Introduction:

Polypharmacy describes the concurrent use of multiple medications.1 Approximately 40% of adults are prescribed five or more medications, a commonly used threshold to define polypharmacy.2 Polypharmacy has well-established associations with falls, disability, hospitalizations, and mortality.3 Furthermore, polypharmacy is associated with an increased risk for drug-drug interactions, adverse drug events (ADEs), inappropriate prescribing, and non-adherence.3 Thus, reducing exposure to medications when possible may lower the risk for ADEs, enhance quality of life, and reduce avoidable healthcare utilization.4,5

One promising intervention to reduce polypharmacy is deprescribing, defined as the intentional dose reduction or discontinuation of a medication.6 Efforts to increase deprescribing in routine clinical practice can be implemented at the payor, healthcare system, prescriber, or patient level. Deprescribing interventions identify opportunities for reducing exposure to medications where potential risks exceed the potential benefits for a patient at a specific point in time.

The design and implementation of a deprescribing intervention should be cognizant of organizational, interprofessional, and patient-specific barriers that can be further complicated by the presence of multiple prescribers involved in a patients care.7,8 Patients with an increasing number of prescribers may experience disruptions in the effective transfer of healthcare-related information between prescribers, precluding timely access to relevant information needed for safe medication management decisions. This may partly explain why low continuity of care is associated with drug-drug interactions, a medication-related problem often mediated by exposure to polypharmacy.9 Furthermore, fragmented communication between a patient’s prescribers can result in no one provider taking ownership of medications used for a prolonged period and prescribers ordering refills for medications that were discontinued, potentially reducing the effectiveness of deprescribing interventions.

Deprescribing interventions may be optimized by considering the impact of multiple prescribers on both their implementation and effectiveness. To date, the concept of multiple prescribers has been largely related to identifying patients at risk for opioid-related adverse events or drug diversion or to calculate continuity of care measures.10,11 A conceptual framework of multiple prescribers has not been defined nor described in the context of deprescribing.

To that end, an international working group comprised of physicians, pharmacists, epidemiologists, and researchers was created within the United States Deprescribing Research Network (USDeN) to develop a conceptual framework of multiple prescribers in the context of deprescribing. The working group was primarily composed of participants from various cohorts of the USDeN’s Junior Investigator Intensive, a year-long mentorship program for emerging leaders in the deprescribing space. Working group members identified this topic during the 2022 USDeN Annual Network Meeting as one requiring additional examination, resulting from members’ clinical experience and deprescribing research knowledge. For example, clinicians within our working group discussed deprescribing challenges when an increasing number of clinicians were involved in a patient’s care (enhancing the difficulty of identifying which provider to communicate with) or where for particular cases no one clinician experienced accountability for a particular patients’ medications, particularly when medications were prescribed for years, if not decades, prior.

The proposed framework is intended to delineate how multiple prescribers impact deprescribing and to provide future directions for clinical efforts, quality improvement, and research. In this paper, we: (1) define “multiple prescribers” in the context of deprescribing, (2) use the Socio-Ecological model to describe problems related to multiple prescribers at multiple levels, and (3) set forth a research agenda for the intersection of multiple prescribers, deprescribing, and health outcomes.

1. Multiple Prescribers Definition:

We define “multiple prescribers” as the involvement of more than one prescriber who prescribes medications to a patient during a prespecified observation period. These prescribers may practice within or across settings (e.g., inpatient and outpatient) and healthcare systems. Our definition is analogous to that used in prior research analyses.12,13

2. Barriers to deprescribing in the presence of “Multiple Prescribers” described through the Socio-Ecologic model:

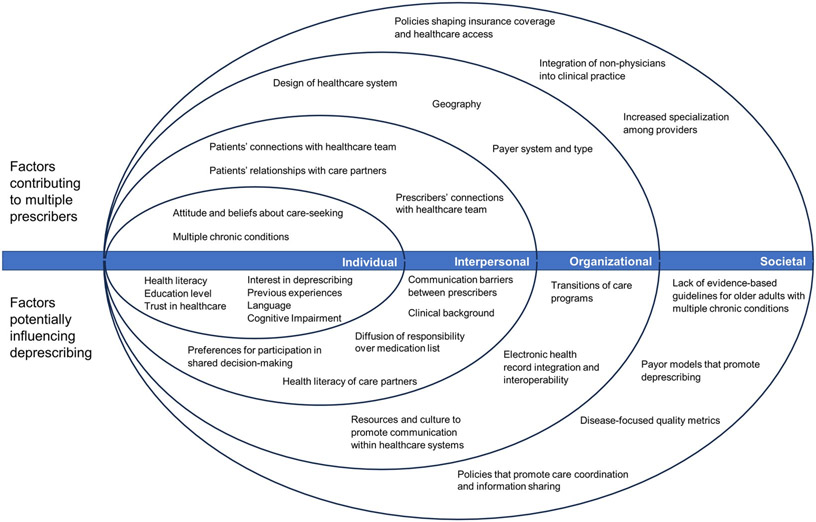

The Socio-Ecological Model (SEM) is a conceptual model that describes how patients and their health-related decisions are influenced by multiple levels of factors, including individual, interpersonal, community settings, organizational structures, and broader societal contexts.14 This model is often used in public health and healthcare to understand the multiple influences on health and well-being. We selected the SEM because it is an effective model to organize and understand how multiple prescribers may make it more difficult to deprescribe, as there are numerous described contextual determinants that facilitate or inhibit deprescribing at each SEM level.15-17 Further, using the SEM model allows for integration with multiple Implementation Science (IS) models. Below we describe how each level may increase the challenges of deprescribing when patients have multiple prescribers. Importantly, we note that the ability of factors to exert influence across levels (e.g., societal norms can influence individual attitudes and beliefs). Table 1 and Figure 1 summarize the identified factors by each level of the SEM model.

Table 1:

The Socioecological Model: factors associated with multiple prescribers and successful deprescribing.

| Level of model | Factors contributing to multiple prescribers |

Factors influencing deprescribing | Example evaluation questions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual |

|

|

|

| Interpersonal |

|

|

|

| Organizational |

|

|

|

| Societal |

|

|

|

Figure 1.

Socioecological model of factors contributing to multiple prescribers and potentially influencing deprescribing

Individual Level:

The individual level in the SEM includes a patient’s biology, lived experiences, attitudes, and beliefs. These factors can influence the number of prescribers from whom a patient receives care to manage their acute and chronic health conditions. For example, older patients with multiple chronic conditions may receive care from a primary care provider (PCP) and several specialists, many of whom prescribe different medications, resulting in complex medication regimens and potentially conflicting instructions from different prescribers.18 Attitudes and beliefs about care-seeking may also influence whether a patient has multiple prescribers.19 Some patients may prefer to manage their chronic conditions with one clinician while others may consciously seek care from multiple clinicians for additional opinions, specialized care, or to address unmet needs.20

At the individual level, patient-specific preferences and characteristics (e.g., health literacy, education, trust in the healthcare system, and engagement in their healthcare) may affect attitudes towards medications and willingness to deprescribe. For example, patients with greater interest in discontinuing medications, who have had positive deprescribing experiences, and whom are interested in discussing the benefits and harms of medications may be more receptive to deprescribing.21,22 Furthermore, if an intervention requires that the patient communicate a deprescribing recommendation between prescribers, the transfer of relevant information can be hindered by language barriers, low health literacy, or cognitive impairment. These individual-level characteristics may be shaped by other levels in the SEM model, such as societal or cultural norms about patient autonomy and medication-taking.

Interpersonal Level:

The interpersonal level includes a patient’s connections with their healthcare team and with care partners (e.g., family, friends, acquaintances). This level also reflects interpersonal relationships between a patient’s multiple prescribers. The presence of multiple prescribers can challenge care coordination and communication, which can yield fragmented care, inconsistent treatment approaches, and a higher likelihood of medication management errors. Additionally, patients may not be comfortable with deprescribing initiated by someone other than the original prescriber or because of the deprescribing clinician’s professional background (i.e., generalists, pharmacists, or nurse practitioners).23 Clinicians attempting to deprescribe medications also must account for patients’ preferences for shared decision-making specific to deprescribing. These preferences result from many factors, including cultural norms about patient autonomy and participation in medical decision-making,24,25 rapport with the original prescribing clinician, and the relationship with the deprescribing clinician.22 For example, some patients may interpret attempts to deprescribe as challenging or undermining the original prescriber’s authority.

Prescribers attempting to deprescribe face challenges at the clinician-clinician interpersonal level as well. Differences in professional backgrounds and poor communication between providers may hinder deprescribing efforts.26,27 Some prescribers may be hesitant to deprescribe when they are unfamiliar with other members of their patient’s care team or have limited involvement with a patient’s treatment regimen.28 For example, inpatient clinicians may be hesitant to stop medications initiated or managed by outpatient prescribers.29 When medications have been used for many years, there may be diffusion or loss of responsibility to evaluate its continued benefit and deprescribe as indicated.30

The involvement of a patient’s care partners, while typically beneficial, can increase interpersonal complexity. Patients may depend on multiple care partners to coordinate healthcare appointments and transfer relevant information between prescribers.31 Care partners with competing responsibilities or their own low levels of health literacy can have difficulty accurately communicating to prescribers a patient’s complete and current medication regimen.32,33 This can impede the proper delivery of a deprescribing intervention or hinder the effective identification of patients who would benefit from a deprescribing intervention.

Organizational level:

The organizational level reflects the structured systems to which patients belong, such as healthcare systems and insurance plans. Patients largely will participate in the healthcare systems and receive care from prescribers available to them due to their geography and the design of their insurance benefits.19,34,35 Some insurance plans (e.g., Health Management Organizations) coordinate care through a PCP and require referrals to a specialist. Other insurance plans or healthcare systems (e.g., Preferred Provider Organizations) allow patients to schedule appointments with specialists within a specific network, while others allow patients to schedule appointments with specialists with possible fees or penalties to patients or providers (e.g., Japan’s statutory health insurance system,36 Australia’s Medicare,37 Canadian Medicare)38. Clinics within healthcare systems may rely on cross-coverage between multiple clinicians to ensure timely access, yet this can increase the number of prescribers involved in a patient’s care. When prescribers are not located within the same facility or healthcare system, it can hinder care coordination and communication.

Deprescribing interventions implemented at the organizational level must contend with barriers that can occur when transfer of healthcare information is disrupted within and across healthcare systems. This may be more likely in healthcare systems that have not adopted electronic health records or strategies to facilitate the transfer of relevant health information between providers at different locations. An international scoping review of continuity of care and care coordination found numerous barriers to effective care coordination between hospitals and primary care, including difficulty planning timely follow-up appointments, lack of awareness of patient hospitalizations by PCPs, not having hospital records or discharge summaries at follow-up appointments, and low levels of information continuity between healthcare settings which can be hampered by barriers related to data ownership and confidentiality.39 Notably, despite mandated adoption of electronic health records in the US, there is often minimal communication and coordination about medication changes between health systems, settings with different acuity of care (e.g., inpatient and outpatient), different clinical specialties (including primary care), and community pharmacies.40

Effective deprescribing is not possible when relevant information is not effectively communicated to patients, prescribers, or dispensing pharmacies.41 Efforts to improve communication may mitigate these concerns about medication data, but in their absence, medication deprescribing decisions rely on patients and care partners to share information between prescribers.42 One example of an attempt to enhance information transfer is transitions of care programs, which are a formalized process that engages patients, caregivers, and their providers to ensure consistent medication data that accounts for all medication changes across healthcare settings (i.e., from hospital admittance to hospital discharge to follow-up appointments) and are communicated to all relevant decision-makers.43

Continuity of care is further challenged when a patient obtains care from acute or emergency healthcare settings due to social needs, such as lack of access to a regular PCP, transportation issues, or inadequate health insurance.44 These organizational-level factors can make it challenging for a prescriber to confidently identify patients who are appropriate candidates for deprescribing or specific medications to discontinue due to uncertainty about a patients’ chronic conditions, medications, and social circumstances.

Societal Level:

The societal level includes regulations, policies, and norms that shape healthcare practice and organizational structures. While the mean annual number of primary care visits per patient is unchanged among Medicare beneficiaries in the US over the past 20 years, PCPs must coordinate care and prescriptions with an 80% increase in the number of specialists involved in the care of their patients.45 Other countries are also seeing an increase in wait times for specialist visits, which may signal similar trends toward increased complexity to coordinate care with specialists globally.46 An important policy that may impact the number of providers per patient include facilitation of patient access to primary care services through expansion of prescribing authority to non-physician practitioners (i.e., NPs, PAs, Pharmacists); while beneficial, there may be an unintended consequence of worsening fragmentation of relevant healthcare information at the point of prescribing.

Furthermore, evidence-based guidelines often focus on the management of a single disease rather than multiple chronic conditions, which can contribute to undetected harms when patients with coexisting comorbidities are being treated by multiple specialists.47,48 Social factors such as limited access to regular care, insurance, or health literacy may increase the propensity for patients to use acute or urgent care services, thereby increasing the number of prescribers.49

Given the increased number of specialists per patient, deprescribing interventions must carefully consider the complexity of interpersonal and organizational variables that can influence successful deprescribing. Financial pressures to adhere to disease-focused quality metrics and pay-for-performance models can hinder identification of potentially unnecessary medications and associated development of deprescribing solutions.47,48 Policies and regulations that do not prioritize care coordination or information sharing between prescribers in different settings may contribute to the potential harm faced by patients with multiple prescribers.

3. Research Agenda:

As indicated earlier, the presence of multiple prescribers is not inherently harmful. However, taking into consideration how the number of prescribers influences a patient’s overall medication regimen, and how the patients and prescribers interact with one another may help explain why a deprescribing intervention is successful in one setting and not another. This and other research questions may benefit from considering how multiple prescribers can affect medication management and deprescribing. Some factors identified within our SEM-based model may be more relevant than others depending on geography, healthcare system design, and how patients interact with the healthcare system and providers.

A careful consideration of the context, population, interventions, implementation strategies, and outcomes through an implementation science framework can yield key information to facilitate the continuous improvement and scalability of a deprescribing intervention.50 Below, we describe how researchers might incorporate the concept of multiple prescribers in various research questions using the Socio-Ecological model. Moreover, our conceptual model based on the SEM aligns with IS determinant frameworks which take a systems approach in identifying and describing contextual determinants (e.g., barriers and facilitators) to the implementation of evidence-based interventions, such as the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR);51 the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF), the Capacity, Opportunity, and Motivation Behavior Model (COM-B); 52 and the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) framework.53,54 Table 1 includes example research questions to guide the design and evaluation of deprescribing interventions.

At the individual level, more research is needed on how to incorporate patient values and priorities into deprescribing interventions, while also taking into consideration patient specific factors affecting deprescribing interventions, such as past experiences or trust and engagement with the healthcare system. Use of IS frameworks which focus on individual-level motivation, capacity, and opportunity, such as the COM-B and the TDF, can help identify meaningful barriers for patients initiating deprescribing when multiple prescribers are involved. For example, motivational barriers such as fear of withdrawal symptoms or return of symptoms from the original problem (e.g., insomnia or pain) have been identified by numerous researchers as individual-level barriers to deprescribing.55

At the interpersonal level, research should examine how to best guide medication management and deprescribing decision-making between patients and their care partners and ensure patients understand the benefits and risks of the medications they are using. Also at the interpersonal level, prescriber-targeted deprescribing interventions need to consider the degree of engagement providers have with patients and others care team members and how the duration of relationships with the patient may affect the ownership each prescriber feels for a patient’s medication and willingness to deprescribe. IS models such as the COM-B and TDF can be used to identify contextual determinants at the interpersonal level. For example, barriers such as limited communication across health facilities or pessimism about patients’ attitudes about stopping medications can be used to design and test evaluations that improve communication between prescribers and reduce pessimism about deprescribing.29

At the organizational level, research into how health systems are structured and organized can help identify the extent of collaboration that prescribers have with each other – and how these structural factors may hinder or help deprescribing efforts. Additionally, understanding these structural factors can inform how and whether deprescribing interventions can be widely disseminated and adapted to improve reach and feasibility. At the societal level, research to create clinical algorithms, guidelines, and deprescribing tools, especially in the context of multiple chronic conditions, is urgently needed. Implementation science frameworks such as CFIR and PARHIS can be used to identify contextual determinants at the organizational and societal levels to evaluate successes and failures of existing interventions, such as organizational resources and culture that promote collaborative and team-based care, and to design implementation strategies.

Conclusion:

The presence of multiple prescribers, while sometimes required for comprehensive care, can create challenges in the optimal prescribing and use of medications. Deprescribing interventions are designed to identify potentially inappropriate medications and ensure patients and prescribers consider the risks posed by specific medications. The SEM framework described herein highlights important factors at each of four levels that can impede successful deprescribing in routine clinical care. Implementation of deprescribing interventions that consider patients’ exposure to multiple prescribers at the different levels of the SEM framework may have a greater likelihood of successfully reducing medication burden, decreasing adverse drug events, and enhancing quality of life.

Key Points:

The involvement of multiple prescribers involved in the care of a patient can disrupt the timely transfer of healthcare related information needed for safe medication management decisions.

An increasing number of providers involved in the care of patients is associated with a lower continuity of care which in turn can increase an individual's risk for drug-drug interactions and potentially impede the successful implementation of a deprescribing intervention.

Understanding the individual, interpersonal, organizational, and societal factors that influence the successful execution of a deprescribing intervention when multiple prescribers are involved can facilitate the design, implementation, and evaluation of the intervention.

Why does this matter?

The socioecological model described in this manuscript highlights important ways in which multiple prescribers involved in a patient’s care can affect the successful implementation of a deprescribing intervention and can be used to facilitate the development and evaluation of future deprescribing interventions.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to express appreciation for the editorial contributions of Dr. Michael Steinman.

Sources of funding:

Dr. Phuong Pham Nguyen receives support from the National Institutes of Health [Grants #R01NS099129, #R01AG02515215, #R01AG06458903] and Acadia Pharmaceuticals Inc. Dr. Jiha Lee is supported by the NIH/NIA R03AG067975. Dr. Juliessa Pavon is supported by NIA 5K23-AG058788. Dr. Michelle S. Keller receives support from the National Institutes of Health [Grants #NIA/NIH K0AG076865]. Dr. Veena Manja reported funding from the VISN-21 Early Career Award Program. Dr. Amy M. Linsky receives support from VA Health Services Research & Development. All authors are supported in part by the National Institute on Aging (R24AG064025).

Sponsor’s role:

Sponsors were not involved in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, analysis, and preparation of the paper.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to report.

Contributor Information

Armando Silva Almodóvar, Institute of Therapeutic Innovations and Outcomes (ITIO), The Ohio State University College of Pharmacy, Columbus, OH. USA.

Michelle S. Keller, Division of General Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA.

Jiha Lee, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Hemalkumar B. Mehta, Department of Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD.

Veena Manja, Veterans Affairs Northern California Healthcare System, Mather, CA; University of California Davis, Sacramento, CA.

Thanh Phuong Pham Nguyen, Department of Biostatistics, Epidemiology and Informatics, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA 19104.

Juliessa M. Pavon, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Geriatrics, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC.

Samuel W Terman, Department of Neurology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Daniel Hoyle, School of Pharmacy and Pharmacology, University of Tasmania, Hobart, TAS.

Amanda S. Mixon, Section of Hospital Medicine, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN.

Amy M. Linsky, General Internal Medicine, Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System, Boston, MA, USA, Center for Healthcare Organization and Implementation Research, Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System, Boston, MA, USA, General Internal Medicine, Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine, Boston, MA, USA.

References:

- 1.Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L, Caughey GE. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):230. Published 2017 Oct 10. Doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0621-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delara M, Murray L, Jafari B, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with polypharmacy: a systematic review and Meta-analysis [published correction appears in BMC Geriatr. 2022 Sep 12;22(1):742]. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):601. Published 2022 Jul 19. Doi: 10.1186/s12877-022-03279-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davies LE, Spiers G, Kingston A, Todd A, Adamson J, Hanratty B. Adverse Outcomes of Polypharmacy in Older People: Systematic Review of Reviews. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(2):181–187. Doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shrestha S, Poudel A, Steadman K, Nissen L. Outcomes of deprescribing interventions in older patients with life-limiting illness and limited life expectancy: A systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;86(10):1931–1945. Doi: 10.1111/bcp.14113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kua CH, Mak VSL, Huey Lee SW. Health Outcomes of Deprescribing Interventions Among Older Residents in Nursing Homes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(3):362–372.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2018.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.What is deprescribing? Bruyère Research Institute; Web site. https://deprescribing.org/what-is-deprescribing/. Accessed May 11, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Linsky A, Zimmerman KM. Provider and system-level barriers to deprescribing: Interconnected problems and solutions. Public Policy Aging Rep. 2018;28(4):129–133. 10.1093/ppar/pry030. doi: 10.1093/ppar/pry030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doherty AJ, Boland P, Reed J, et al. Barriers and facilitators to deprescribing in primary care: a systematic review. BJGP Open. 2020;4(3):bjgpopen20X101096. Published 2020 Aug 25. Doi: 10.3399/bjgpopen20X101096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weng YA, Deng CY, Pu C. Targeting continuity of care and polypharmacy to reduce drug-drug interaction. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):21279. Published 2020 Dec 4. Doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-78236-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Use of opioids from multiple providers (UOP). National Committee for Quality Assurance; Web site. https://www.ncqa.org/hedis/measures/use-of-opioids-from-multiple-providers/. Updated 2023. Accessed May 11, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pereira Gray DJ, Sidaway-Lee K, White E, Thorne A, Evans PH. Continuity of care with doctors-a matter of life and death? A systematic review of continuity of care and mortality. BMJ Open. 2018;8(6):e021161. Published 2018 Jun 28. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jokanovic N, Tan ECK, Dooley MJ, Kirkpatrick CM, Bell JS. Prevalence and factors associated with polypharmacy in long-term care facilities: A systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2015;16(6):535.e1–535.e12. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1525861015001826. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silva Almodóvar A, Nahata MC. Potentially Harmful Medication Use Among Medicare Patients with Heart Failure. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2020;20(6):603–610. Doi: 10.1007/s40256-020-00396-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bronfenbrenner U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American psychologist. 1977;32(7):513. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conklin J, Farrell B, Suleman S. Implementing deprescribing guidelines into frontline practice: barriers and facilitators. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy. 2019. Jun 1;15(6):796–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brunner L, Rodondi N, Aubert CE. Barriers and facilitators to deprescribing of cardiovascular medications: a systematic review. BMJ open. 2022. Dec 1;12(12):e061686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stewart C, Gallacher K, Nakham A, Cruickshank M, Newlands R, Bond C, Myint PK, Bhattacharya D, Mair FS. Barriers and facilitators to reducing anticholinergic burden: a qualitative systematic review. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy. 2021. Dec;43(6):1451–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schlencker A, Messer L, Ardizzone M, et al. Improving patient pathways for systemic lupus erythematosus: a multistakeholder pathway optimisation study. Lupus Sci Med. 2022;9(1):e000700. doi: 10.1136/lupus-2022-000700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Voils CI, Sleath B, Maciejewski ML. Patient perspectives on having multiple versus single prescribers of chronic disease medications: results of a qualitative study in a veteran population. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:490. Published 2014 Oct 25. doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0490-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biernikiewicz M, Taieb V, Toumi M. Characteristics of doctor-shoppers: a systematic literature review. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2019;7(1):1595953. Published 2019 Mar 27. doi: 10.1080/20016689.2019.1595953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linsky A, Simon SR, Stolzmann K, Meterko M. Patient attitudes and experiences that predict medication discontinuation in the Veterans Health Administration. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2018;58(1):13–20. Doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2017.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weir K, Nickel B, Naganathan V, et al. Decision-Making Preferences and Deprescribing: Perspectives of Older Adults and Companions About Their Medicines. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2018;73(7):e98–e107. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbx138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linsky A, Meterko M, Bokhour BG, Stolzmann K, Simon SR. Deprescribing in the context of multiple providers: understanding patient preferences. Am J Manag Care. 2019;25(4):192–198. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamann J, Bieber C, Elwyn G, et al. How do patients from eastern and western Germany compare with regard to their preferences for shared decision making?. Eur J Public Health. 2012;22(4):469–473. Doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckr112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perez Jolles M, Richmond J, Thomas KC. Minority patient preferences, barriers, and facilitators for shared decision-making with health care providers in the USA: A systematic review [published correction appears in Patient Educ Couns. 2020 Feb;103(2):430]. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(7):1251–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2019.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okeowo DA, Zaidi STR, Fylan B, Alldred DP. Barriers and facilitators of implementing proactive deprescribing within primary care: A systematic review. Int J Pharm Pract. 2023;31(2):126–152. 10.1093/ijpp/riad001. doi: 10.1093/ijpp/riad001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spinewine A, Dumont C, Mallet L, Swine C. Medication appropriateness index: reliability and recommendations for future use. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(4):720–722. Doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00668_8.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Djatche L, Lee S, Singer D, Hegarty SE, Lombardi M, Maio V. How confident are physicians in deprescribing for the elderly and what barriers prevent deprescribing? Journal of clinical pharmacy and therapeutics. 2018;43(4):550–555. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keller MS, Carrascoza-Bolanos J, Breda K, et al. Identifying barriers and facilitators to deprescribing benzodiazepines and sedative hypnotics in the hospital setting using the Theoretical Domains Framework and the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation and Behaviour (COM-B) Model: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2023;13(2):e066234. Published 2023 Feb 22. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-066234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rotman SR, Bishop TF. Proton pump inhibitor use in the U.S. ambulatory setting, 2002-2009. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e56060. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Travis SS, Bethea LS, Winn P. Medication administration hassles reported by family caregivers of dependent elderly persons. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2000;55(7):M412–M417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Look KA, Stone JA. Medication management activities performed by informal caregivers of older adults. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy. 2018/May/01/ 2018;14(5):418–426. Doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2017.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lang A, Macdonald M, Marck P, et al. Seniors managing multiple medications: using mixed methods to view the home care safety lens. BMC health services research. 2015;15(1):1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naylor KB, Tootoo J, Yakusheva O, Shipman SA, Bynum JPW, Davis MA. Geographic variation in spatial accessibility of U.S. healthcare providers. PLoS One. 2019;14(4):e0215016. Published 2019 Apr 9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feyman Y, Figueroa JF, Polsky DE, Adelberg M, Frakt A. Primary Care Physician Networks In Medicare Advantage. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(4):537–544. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.3.1 Japan’s health insurance system. Japan Health Policy Now; Web site. https://japanhpn.org/en/section-3-1/. Accessed September 12, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Victoria State Government Department of Health. Seeing a specialist. Better Health Channel; Web site. https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/servicesandsupport/seeing-a-specialist#accessing-a-specialist. Updated 2015. Accessed September 12, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yikkanen R, Osborn R, Mossialos E, Djordjevic A, Wharton G. International health care system profiles: Canada. The Commonwealth Fund; Web site. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/international-health-policy-center/countries/canada. Updated 2020. Accessed September 12, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khatri R, Endalamaw A, Erku D, et al. Continuity and care coordination of primary health care: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1):750. Published 2023 Jul 13. doi: 10.1186/s12913-023-09718-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones CD, Vu MB, O'Donnell CM, et al. A failure to communicate: a qualitative exploration of care coordination between hospitalists and primary care providers around patient hospitalizations. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(4):417–424. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3056-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang Y, Ward-Charlerie S, Kashyap N, DeMayo R, Agresta T, Green J. Analysis of medication therapy discontinuation orders in new electronic prescriptions and opportunities for implementing CancelRx. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2018;25(11):1516–1523. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocy100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831–841. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.8.831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Medication Safety in Transitions of Care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. (WHO/UHC/SDS/2019.9). Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coster JE, Turner JK, Bradbury D, Cantrell A. Why Do People Choose Emergency and Urgent Care Services? A Rapid Review Utilizing a Systematic Literature Search and Narrative Synthesis. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24(9):1137–1149. Doi: 10.1111/acem.13220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barnett ML, Bitton A, Souza J, Landon BE. Trends in Outpatient Care for Medicare Beneficiaries and Implications for Primary Care, 2000 to 2019 [published correction appears in Ann Intern Med. 2022 Oct;175(10):1492]. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(12):1658–1665. doi: 10.7326/M21-1523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.OECD. Waiting times for health services. ; 2020:69. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/publication/242e3c8c-en. 10.1787/242e3c8c-en. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Buffel du Vaure C, Ravaud P, Baron G, Barnes C, Gilberg S, Boutron I. Potential workload in applying clinical practice guidelines for patients with chronic conditions and multimorbidity: a systematic analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6(3):e010119. Published 2016 Mar 22. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tinetti ME, Green AR, Ouellet J, Rich MW, Boyd C. Caring for Patients With Multiple Chronic Conditions [published correction appears in Ann Intern Med. 2019 Mar 5;170(5):356]. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(3):199–200. doi: 10.7326/M18-3269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ryan JL, Franklin SM, Canterberry M, et al. Association of Health-Related Social Needs With Quality and Utilization Outcomes in a Medicare Advantage Population With Diabetes. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(4):e239316. Published 2023 Apr 3. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.9316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ailabouni NJ, Reeve E, Helfrich CD, Hilmer SN, Wagenaar BH. Leveraging implementation science to increase the translation of deprescribing evidence into practice. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2022;18(3):2550–2555. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2021.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Damschroder LJ, Reardon CM, Widerquist MA, Lowery J. The updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research based on user feedback. Implementation science. 2022. Dec;17(1):1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implementation science. 2012. Dec;7:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rycroft-Malone J. The PARIHS framework—a framework for guiding the implementation of evidence-based practice. Journal of nursing care quality. 2004. Oct 1;19(4):297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stetler CB, Damschroder LJ, Helfrich CD, Hagedorn HJ. A guide for applying a revised version of the PARIHS framework for implementation. Implementation science. 2011. Dec;6(1):1–0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reeve E, To J, Hendrix I, Shakib S, Roberts MS, Wiese MD. Patient barriers to and enablers of deprescribing: a systematic review. Drugs & aging. 2013. Oct;30:793–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]