Key Points

Question

Can either patient portal or text message reminders to patients about influenza vaccination raise vaccination rates across a health system, and do text messages work better than portal messages?

Findings

In this 3-arm randomized clinical trial that included 262 085 patients in 79 primary care practices, neither portal nor text message patient reminders were successful in raising overall influenza vaccination rates.

Meaning

Health systems and health care professionals need to implement more intensive interventions than patient reminders to raise influenza vaccination rates.

This randomized clinical trial evaluates and compares the effect of patient portal vs text message reminders on influenza vaccination rates across a health system in the United States.

Abstract

Importance

Increasing influenza vaccination rates is a public health priority. One method recommended by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and others is for health systems to send reminders nudging patients to be vaccinated.

Objective

To evaluate and compare the effect of electronic health record (EHR)–based patient portal reminders vs text message reminders on influenza vaccination rates across a health system.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This 3-arm randomized clinical trial was conducted from September 7, 2022, to April 30, 2023, among primary care patients within the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) health system.

Interventions

Arm 1 received standard of care. The health system sent monthly reminder messages to patients due for an influenza vaccine by portal (arm 2) or text (arm 3). Arm 2 had a 2 × 2 nested design, with fixed vs responsive monthly reminders and preappointment vs no preappointment reminders. Arm 3 had 1 × 2 design, with preappointment vs no preappointment reminders. Preappointment reminders for eligible patients were sent 24 and 48 hours before scheduled primary care visits. Fixed reminders (in October, November, and December) involved identical messages via portal or text. Responsive portal reminders involved a September message asking patients about their plans for vaccination, with a follow-up reminder if the response was affirmative but the patient was not yet vaccinated.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was influenza vaccination by April 30, 2023, obtained from the UCLA EHR, including vaccination from pharmacies and other sources.

Results

A total of 262 085 patients (mean [SD] age, 45.1 [20.7] years; 237 404 [90.6%] adults; 24 681 [9.4%] children; 149 349 [57.0%] women) in 79 primary care practices were included (87 257 in arm 1, 87 478 in arm 2, and 87 350 in arm 3). At the entire primary care population level, none of the interventions improved influenza vaccination rates. All groups had rates of approximately 47%. There was no statistical or clinically significant improvement following portal vs text, preappointment reminders vs no preappointment reminders (portal and text reminders combined), or responsive vs fixed monthly portal reminders.

Conclusions and Relevance

At the population level, neither portal nor text reminders for influenza vaccination were effective. Given that vaccine hesitancy may be a major reason for the lack of impact of portal or text reminders, more intensive interventions by health systems are needed to raise influenza vaccination coverage levels.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05525494

Introduction

Raising influenza vaccination rates is a public health priority. Despite substantial morbidity from influenza1,2 and recommendations for annual vaccination by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices and US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,1,3 US influenza vaccination coverage is low. During the 2021 to 2022 influenza season, coverage was 51.4% overall, 57.8% for children aged 6 months to 17 years, 37.1% for adults aged 18 to 49 years, 52.4% for adults aged 50 to 64 years, and 73.9% for adults older than 65 years.4 Rates were similar in the 2022 to 2023 season.5

The Guide to Community Preventive Services and other experts recommend that health systems or health care professionals send patients reminders about influenza vaccinations to raise coverage.6,7 Reminders from health systems can be delivered by autodialers, patient portals, or text messaging.8 Autodialed messaging showed mixed success and robocalls (automated telephone calls delivering a recorded message) can irritate people.9 Patient portals, secure internet-based platforms linked with electronic health records (EHRs),10 hold promise because they emanate from health systems11 as trusted sources.

We published the results of a series of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) evaluating portal reminders for influenza vaccinations: monthly reminders,12 messages tailored to patient age or diabetes diagnosis,13 psychological strategies (positive/negative framing; asking patients to precommit to vaccination), preappointment reminders, and allowing patients to self-schedule vaccination appointments.14 These interventions showed limited or no impact at the population level. One possible reason was the friction or extra work required with portal reminders—patients receive email or text notifications of a portal message but then need to sign into the portal and click within it to read the message.11 A second possibility is that patients have decided about influenza vaccination and ignore patient reminders, ie, vaccine hesitancy accounts for lack of vaccination. This is unlikely given that studies have noted other barriers, such as forgetting to schedule appointments, omission bias (tendency to not act if feeling somewhat hesitant), misunderstanding vaccine effectiveness and safety, and access barriers.

In contrast to portal messages, text messages appear on people’s phones without their effort. A core finding from behavioral science on nudging behaviors is that removing even modest obstacles to a desired action can increase follow-through, so texts might be more effective than portal messages. Many health systems use texts to communicate with patients.15 Some studies, which tended to involve small numbers of practices, children, and low-income populations, found that text reminders for influenza vaccination can raise rates.16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23 Other studies have found little or no impact.24,25 To our knowledge, no studies have directly compared the impact of patient portal vs text messaging on influenza vaccination.

In addition, a mega-study found that text message reminders sent just before an upcoming appointment (called preappointment reminders, when action is imminent26) raised influenza vaccination rates at that upcoming appointment for the subgroup of patients with scheduled non–sickness-related appointments in the fall. Two key questions are whether this intervention raises vaccination rates at the population level (ie, not just among those with appointments) and whether patients would have received their vaccination after that appointment anyway before the end of the influenza season.

Our primary objective was to compare the effect of portal vs text messages on raising influenza vaccination rates across a health system. We hypothesized that text reminders are more effective than portal reminders. A secondary objective was to assess the impact of portal and text preappointment reminders on overall coverage for the entire population (not only for those with scheduled appointments) and at the end of the vaccination season (not only at an upcoming visit). Finally, we explored whether fixed monthly portal reminders (identical monthly messages) were as effective as responsive portal reminders (reminders in November and December to patients who indicated they desired vaccination in September but remained unvaccinated).

Methods

Study Design

The University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) institutional review board approved this study with a patient consent waiver. The study was conducted between September 7, 2022, and April 30, 2023, across the entire UCLA Health System (79 primary care practices). The trial protocol appears in Supplement 1; the protocol refers to this RCT as “RCT #5.”

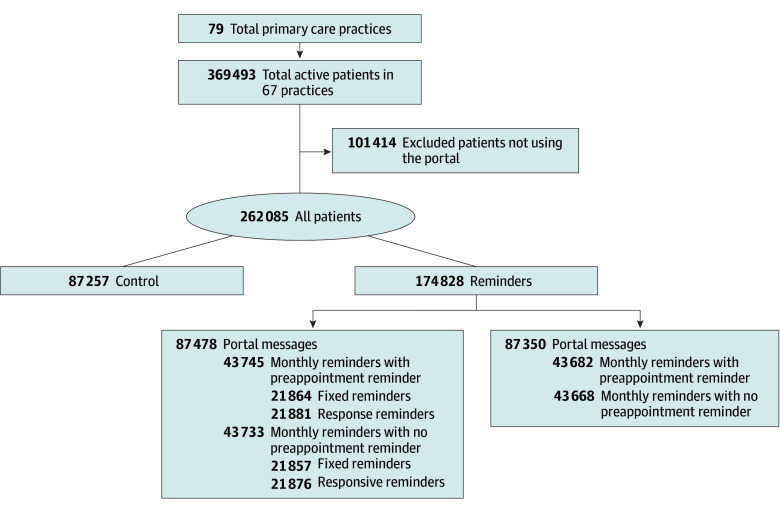

We used a 3-arm RCT (Figure). We considered this a pragmatic trial because we randomized all patients in the health system without exclusions. Patients were randomized to a standard-of-care control group (arm 1) or patient reminder group, and randomly allocated the patient reminder group to portal reminders (arm 2) or text reminders (arm 3). Within the portal reminder group, we randomized patients to 4 groups: fixed or responsive monthly portal reminders, with or without preappointment reminders. Within the text reminder group everyone received fixed monthly reminders; we randomized patients to preappointment reminders or not. We were technically unable to send responsive text messages. Thus, we simultaneously compared monthly portal vs monthly text messages and preappointment portal vs text reminders; we also assessed responsive portal reminders vs fixed portal and text reminders.

Figure. Study Flow Diagram.

Study Participants

We included all primary care internal medicine, medicine-pediatrics, family medicine, and pediatric practices within the UCLA Health System and all patients aged 6 months or older receiving primary care at these practices if they (1) had at least 2 total visits or at least 1 preventive care visit to a primary care practitioner (PCP) within 1 year or (2) were enrolled in managed care and assigned to UCLA Health irrespective of visits. We matched patients to the primary care practice last visited. We included patients if they (or their proxy) had consented to receive UCLA short message service–text messages and were active portal users (defined as having logged into the portal at least once during the prior year, not including initial portal login [85% met this criteria]; eTable 1 in Supplement 2).

Then we identified family units with an algorithm that matched addresses, phone numbers, insurance member numbers, and patient guarantor identifiers. Study statisticians randomly selected and allocated 1 index patient per family to a study or control arm; other researchers and PCPs were blinded to patient allocation. Other family members were sent the same portal or text messages to prevent confusion, but we did not include these family members in analyses or the study denominator. We did not account for patients being included in any prior studies, but with large numbers randomized, this factor would be balanced across study arms.

Interventions: Portal and Text Messages

UCLA uses Epic EHR to generate patient portal messages and a company (WELL Health Technologies Corp) for text messages. Statisticians checked the EHR for prior vaccination and for messages to be sent to unvaccinated patients. Portal group participants were notified they had “A message from your doctor” on the patient portal by email or smartphone app notification (based on patients’ portal preferences). Patients needed to log into the portal to read messages. Text and portal messages were identical (eAppendix in Supplement 2); messages were in English (98% of patients listed English as preferred language for the portal) and below seventh-grade reading level (Flesch-Kincaid analysis). Multiple UCLA patients piloted the messages for content and construct validity. Clinicians were not copied on portal or text messages.

Monthly Fixed Reminders

Portal and text messages were identical to each other and across months and sent in late October, November, and December 2022. The message addressed patients by name and stated, “This year’s flu vaccine is now available. We reserved a dose for you.” The “reserved for you” phrase was found to bolster vaccination in preappointment reminders21 (perhaps by implicit promoting expressions of exclusivity27). The messages encouraged patients to self-schedule vaccination appointments at their primary care practice, other UCLA sites, or a pharmacy (with pharmacy geographic links); portal messages were signed “Your UCLA Health team.”

Preappointment Reminders

These messages were added to routine preappointment reminders that are sent by the health system 24 and 48 hours before a scheduled primary care appointment that does not mention influenza vaccination. Portal and text messages were identical and read, “This is a reminder that a flu vaccine has been reserved for your upcoming appointment. Please ask your doctor for the vaccine to make sure you receive it.”

Responsive Portal Reminders

A September precommitment portal questionnaire asked patients, “Where do you plan to get a flu vaccine this season?” Response options included UCLA site, pharmacy, workplace or school, other, I do not plan on getting a vaccine, and I already received a vaccine. If patients responded with a plan for vaccination, a second question asked, “What month do you think you will get the vaccine?” Participants could select September, October, November, December, or later; the message then stated “Thank you. We will make a note in your medical record and check back with you,” based on social psychology principle that planning prompts and public commitment improve follow-through.28,29,30 We then sent unvaccinated patients a reminder the month after their reported vaccination plans, “This is a friendly reminder that you indicated in September that you planned to get a flu vaccine [at selected location] by now. We do not have a record of a flu vaccination for you. Please schedule a vaccine visit at a UCLA clinic by calling [clinic phone number] or by clicking [here]. You can also find a pharmacy near you for a vaccine [link].” Patients reporting no plan to get the vaccine were not sent further reminders. Patients not responding in September were sent fixed monthly reminders.

Children

Portal and text messages sent to children (proxies) were addressed to “Parent of [Child’s First Name]” with the same content as adult patients; portal messages were sent to the child’s (proxy’s) portal log-in. Messages for adolescents older than 13 years with portal or phone privileges were sent to them.

Measures

Patient Characteristics

Patient characteristics are displayed by predetermined subgroups: age, gender, insurance, race, ethnicity, and influenza vaccination receipt in past 2 years. We assessed race and ethnicity given that influenza vaccination rates are lower among Black and Latino adult patients than White patients nationally.

Influenza Vaccination Data

The UCLA Health System EHR automatically includes influenza vaccination dates and locations from any UCLA site and incorporates external vaccinations from (1) California Immunization Registry, (2) Surescripts pharmacy benefits manager, and (3) Care Everywhere (other Epic sites). UCLA clinicians can manually enter additional vaccination data into the EHR, as can patients through the portal. We integrated these external data sources before analyses.

Outcome Measures

Primary Outcome

This included any influenza vaccination between August 1, 2022, and April 30, 2023, from the EHR but excluded self-reported vaccinations by portal group patients in response to portal reminders since neither the control nor text groups had the same opportunity for self-report. This eliminated differential ascertainment of vaccination but introduced a conservative bias because portal reminders might lead to vaccinations at locations not sending data to UCLA.

Secondary Outcomes

We assessed external vaccinations and portal message opening.

Power Calculation

Power was estimated for the evaluation of each subintervention (portal vs text vs control, preappointment reminder vs none, fixed vs responsive reminders) averaging over the other interventions, within the treatment arm. An overall sample size of 262 085 patients provided greater than 90% power to detect a small but clinically meaningful 2–percentage point improvement in vaccination for the most conservative comparisons, assuming a χ2 test, control group rate of 50% (most conservative), and significance level of 0.01 (5-fold Bonferroni correction for simultaneous evaluation of each intervention).

Statistical Analysis

Our primary analyses compared vaccination rates between study arms using mixed-effects Poisson regression with robust standard errors. Models included main effects for modality (portal vs text vs control), preappointment reminder (yes vs no), and reminder type (fixed vs responsive), plus random practice effects and controls for patient characteristics (age, gender, race, ethnicity, insurance, and prior vaccination). Secondary subgroup analyses were performed by fitting separate models including interactions between the subgrouping factor of interest and each of the main intervention effects and performing appropriate linear contrasts.

We also performed an exploratory subgroup analysis in the patient subset who (1) had at least 1 PCP visit after initiation of preappointment reminders (October 20, 2022, to April 30, 2023) and (2) were not vaccinated. We evaluated text and portal preappointment reminder effects using interaction terms with modality. For the primary analysis, we used a significance level of 0.01 (adjusting for multiple comparisons); in all other analyses, we considered P < .05 statistically significant. Tests were 2-tailed.

We performed a Cox proportional hazards model, with random practice effects, to evaluate the time to influenza vaccination using the same specification as in our primary analysis. Statistical analyses used SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

Practice and Patient Characteristics

Altogether, 262 085 patients (mean [SD] age, 45.1 [20.7] years; 237 404 adults and 24 681 children) were included (Figure). The majority were women (149 349 [57.0%], had private (218 728 [83.5%]) or Medicare (39 008 [14.9%]) insurance, and had influenza vaccination within 2 years (169 078 [64.5%]) (Table 1). Overall, there were 27 361 (10.4%) Asian patients, 12 087 (4.6%) Black patients, and 137 466 (52.5%) White patients; 32 047 patients (12.2%) were Hispanic or Latino, and 186 948 (71.3%) were not Hispanic or Latino.

Table 1. Characteristics of the Sample by Study Condition.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control arm (n = 87 257) | Modalitya | Preappointment reminderb | Message typec | |||||

| Portal (n = 87 478) | Text (n = 87 350) | Yes (n = 87 427) | No (n = 87 401) | Responsive, portal only (n = 43 757) | Fixed, portal or text (n = 131 071) | |||

| Age | ||||||||

| 6 mo to <18 y | 8238 (9.4) | 8218 (9.4) | 8225 (9.4) | 8189 (9.4) | 8254 (9.4) | 4111 (9.4) | 12 332 (9.4) | |

| 18-64 y | 62 084 (71.2) | 62 235 (71.1) | 62 118 (71.1) | 62 252 (71.2) | 62 101 (71.1) | 31 068 (71.0) | 93 285 (71.2) | |

| ≥65 y | 16 935 (19.4) | 17 025 (19.5) | 17 007 (19.5) | 16 986 (19.4) | 17 046 (19.5) | 8578 (19.6) | 25 454 (19.4) | |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Women | 49 812 (57.1) | 49 702 (56.8) | 49 835 (57.1) | 49 823 (57.0) | 49 714 (56.9) | 24 965 (57.1) | 74 572 (56.9) | |

| Men | 37445 (42.9) | 37 776 (43.2) | 37 515 (43.0) | 37 604 (43.0) | 37 687 (43.1) | 18 792 (43.0) | 56 499 (43.1) | |

| Primary insurer | ||||||||

| Private | 72 766 (83.4) | 73 116 (83.6) | 72 846 (83.4) | 73 181 (83.7) | 72 781 (83.3) | 36 521 (83.5) | 109 441 (83.5) | |

| Public | 13 032 (14.9) | 12 893 (14.7) | 13 083 (15.0) | 12 828 (14.7) | 13 148 (15.0) | 6500 (14.9) | 19 476 (14.9) | |

| Other or unknown | 1459 (1.7) | 1469 (1.7) | 1421 (1.6) | 1418 (1.6) | 1472 (1.7) | 736 (1.7) | 2154 (1.6) | |

| Race | ||||||||

| Asian | 9151 (10.5) | 9123 (10.4) | 9087 (10.4) | 9073 (10.4) | 9137 (10.5) | 4574 (10.5) | 13 636 (10.4) | |

| Black | 4076 (4.7) | 3962 (4.5) | 4049 (4.6) | 4015 (4.6) | 3996 (4.6) | 1942 (4.4) | 6069 (4.6) | |

| White | 45 713 (52.4) | 46 017 (52.6) | 45 736 (52.4) | 45 704 (52.3) | 46 049 (52.7) | 23 114 (52.8) | 68 639 (52.4) | |

| Other, unknown, or multipled | 28 317 (32.5) | 28 376 (32.4) | 28 478 (32.6) | 28 635 (32.8) | 28 219 (32.3) | 14 127 (32.3) | 42 727 (32.6) | |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 10 695 (12.3) | 10 694 (12.2) | 10 658 (12.2) | 10 667 (12.2) | 10 685 (12.2) | 5333 (12.2) | 16 019 (12.2) | |

| Non-Hispanic or unknown | 76 562 (87.7) | 76 784 (87.8) | 76 692 (87.8) | 76 760 (87.8) | 76 716 (87.8) | 38 424 (87.8) | 115 052 (87.8) | |

| Vaccine history | ||||||||

| None | 31 076 (35.6) | 30 936 (35.4) | 30 995 (35.5) | 31 046 (35.5) | 30 885 (35.3) | 15 490 (35.4) | 46 441 (35.4) | |

| Prior vaccination | 56 181 (64.4) | 56 542 (64.6) | 56 355 (64.5) | 56 381 (64.5) | 56 516 (64.7) | 28 267 (64.6) | 84 630 (64.6) | |

All groups within the portal or within the text message arms were combined, irrespective of whether they were allocated to preappointment reminders or not or to fixed or responsive reminders.

Portal and text groups were combined.

The responsive group contains patients allocated to the portal group only. The fixed group contains patients allocated to the portal or text fixed monthly reminders groups.

The “other” category included participants who selected American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, do not identify with race, and other race.

Influenza Vaccination by Study Group

Vaccination rates were (Table 2) as follows: control, 41 166 (47.1%); modality: portal, 41 368 (47.3%); text, 41 259 (47.2%); preappointment reminder: yes, 41 432 (47.4%); no, 41 195 (47.1%); and message type: responsive portal messages, 20 691 (47.3%); fixed portal or text message, 61 936 (47.3%). Contrary to our main hypothesis, we found no differences in vaccination rates among control, portal, or text message groups and no impact of responsive vs fixed monthly portal messages.

Table 2. Vaccination Rates by Condition and Subgroupsa .

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Intervention groups | ||||||

| Modalityb | Preappointment reminder (portal or text)c | Message typed | |||||

| Portal | Text | Yes | No | Responsive, portal only | Fixed, portal or text | ||

| All patients | 41 166 (47.1) | 41 368 (47.3) | 41 259 (47.2) | 41 432 (47.4)e | 41 195 (47.1) | 20 691 (47.3) | 61 936 (47.3) |

| Age | |||||||

| 6 mo to <18 y | 4245 (51.5) | 4303 (52.4) | 4246 (51.6) | 4290 (52.4) | 4259 (51.6) | 2150 (52.3) | 6399 (51.9) |

| 18-64 y | 26 640 (42.9) | 26 623 (42.8) | 26 692 (43.0) | 26 741 (43.0) | 26 574 (42.8) | 13 259 (42.7) | 40 056 (42.9) |

| ≥65 y | 10 281 (60.7) | 10 442 (61.3) | 10 321 (60.7) | 10 401 (61.2) | 10 362 (60.8) | 5282 (61.6) | 15 481 (60.8) |

| Gender | |||||||

| Women | 23 884 (48.0) | 23 821 (47.9) | 23 841 (47.8) | 23 912 (48.0)f | 23 750 (47.8) | 12 014 (48.1) | 35 648 (47.8) |

| Men | 17 282 (46.2) | 17 547 (46.5) | 17 418 (46.4) | 17 520 (46.6) | 17 445 (46.3) | 8677 (46.2) | 26 288 (46.5) |

| Primary insurer | |||||||

| Private | 33 275 (45.7) | 33 545 (45.9) | 33 397 (45.9) | 33 599 (45.9) | 33 343 (45.8) | 16 742 (45.8) | 50 200 (45.9) |

| Public | 7241 (55.6) | 7170 (55.6)f | 7233 (55.3)e | 7192 (56.1)f | 7211 (54.8) | 3625 (55.8)e | 10 778 (55.3) |

| Other/unknown | 650 (44.6) | 653 (44.5) | 629 (44.3) | 641 (45.2) | 641 (43.6) | 324 (44.0) | 958 (44.5) |

| Race | |||||||

| Asian | 5435 (59.4) | 5377 (58.9) | 5417 (59.6) | 5463 (60.2)e | 5331 (58.4) | 2656 (58.1) | 8138 (59.7) |

| Black | 1517 (37.2) | 1454 (36.7) | 1524 (37.6) | 1466 (36.5) | 1512 (37.8) | 699 (36.0)e | 2279 (37.6) |

| White | 22 425 (49.1) | 22 624 (49.2) | 22 343 (48.9) | 22 395 (49.0) | 22 572 (49.0) | 11 428 (49.4) | 33 539 (48.9) |

| Other, multiple, or unknowng | 11 789 (41.6) | 11 913 (42.0) | 11 975 (42.1) | 12 108 (42.3)f | 11 780 (41.7) | 5908 (41.8) | 17 980 (42.1) |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Hispanic | 4600 (43.0) | 4761 (44.5) | 4668 (43.8) | 4725 (44.3) | 4704 (44.0) | 2391 (44.8) | 7038 (43.9) |

| Non-Hispanic or unknown | 36 566 (47.8) | 36 607 (47.7) | 36 591 (47.7) | 36 707 (47.8) | 36 491 (47.6) | 18 300 (47.6) | 54 898 (47.7) |

| Vaccine history | |||||||

| None | 4719 (15.2) | 4802 (15.5) | 4806 (15.5) | 4907 (15.8)h | 4701 (15.2) | 2402 (15.5) | 7206 (15.5) |

| Prior vaccination | 36 447 (64.9) | 36 566 (64.7) | 36 453 (64.7) | 36 525 (64.8) | 36 494 (64.6) | 18 289 (64.7) | 54 730 (64.7) |

Significance testing is based on an adjusted model (covariates include all factors in this table).

Comparison is with the control group (ie, portal vs control and text vs control) for all subgroups combined.

Comparison is within the intervention conditions (ie, preappointment reminder vs not for portal and text combined).

Comparison is within the intervention conditions (responsive vs fixed messages). The responsive group contains patients allocated to the portal group only. The fixed group contains patients allocated to the portal or text fixed monthly reminders groups.

P < .10.

P < .05.

The “other” category included participants who selected American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, do not identify with race, and other race.

P < .01.

We did not find an effect of portal or text reminders within most demographic subgroups (Table 2). A small effect noted on adjusted analysis among publicly insured patients was not apparent in unadjusted vaccination rates.

We calculated (Table 3) adjusted risk ratios (aRRs) with 95% CIs to compare effects of portal or text vs control, preappointment reminders vs none for portal and text combined, and responsive portal reminders vs fixed portal reminders; the comparisons were neither statistically nor clinically significant. Among prespecified subgroups, patients who were younger adults, males, publicly insured, Black, or who belonged to another racial background (ie, American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, do not identify with race, and other race) had lower vaccination rates; those vaccinated in prior years had higher rates. Findings from the Cox proportional hazards model (eTable 2 in Supplement 2) resembled the primary analysis, showing that the portal and text reminders had no impact on when participants scheduled their vaccinations.

Table 3. Adjusted RRs for Influenza Vaccination by Study Group and Patient Characteristics, Using Mixed-Effects Poisson Regression Models of Vaccination Status.

| Comparison | Adjusted RR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Modality (reference group, control) | |

| Portal | 0.99 (0.98-1.01) |

| Text | 1.00 (0.98-1.01) |

| Preappointment reminder: yes compared with no, portal and text groups combined | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) |

| Interactive: responsive compared with fixed (portal group only) | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) |

| Age (reference group, <18 y) | |

| 18-64 y | 0.87 (0.84-0.90)a |

| ≥65 y | 1.03 (1.00-1.08) |

| Gender: men compared with women | 0.98 (0.98-0.99)a |

| Primary insurer (reference group, private) | |

| Public | 0.97 (0.96-0.98)a |

| Other or unknown | 0.95 (0.92-0.98)a |

| Race (reference group, White) | |

| Asian | 1.13 (1.12-1.14)a |

| Black | 0.89 (0.87-0.92)a |

| Other, multiple, or unknownb | 0.94 (0.93-0.95)a |

| Ethnicity: Hispanic compared with non-Hispanic or unknown | 0.99 (0.97-1.00) |

| Vaccine history: yes compared with no | 4.02 (3.79-4.27)a |

Abbreviation: RR, risk ratio.

P < .05.

The “other” category included participants who selected American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, do not identify with race, and other race.

Subgroup Analysis: Effect of Preappointment Messages

The aRR for preappointment reminders for portal and text groups combined was greater than 1, but the result was not statistically signficant (aRR, 1.01; 95% CI, 1.00-1.02; P = .07). However, only one-fifth of all patients had at least 1 primary care appointment during the study and were still vaccine eligible. Therefore, we evaluated the effect of preappointment reminders for the subgroup with at least 1 primary care appointment and who were unvaccinated at the initial appointment. The main effect of preappointment reminders (portal and text combined) was statistically and clinically significant (aRR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.01-1.06; P = .01). The difference between text vs portal preappointment reminders was not statistically significant (aRR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.99-1.12; P = .08); however, portal preappointment reminders did not have an effect (aRR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.97-1.05; P = .69) while text preappointment reminders had a small impact (aRR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.02-1.11; P = .002) with an absolute increase in vaccination of 1.6 and 1.8 percentage points after that visit or at study end (eTable 3 in Supplement 2).

Process Measures

Influenza Vaccination Source

Of 123 793 patients with an influenza vaccination during the study period, 41 004 (33.1%) received it externally. An additional 4414 (3.6%) influenza vaccinations were self-reported via the patient portal but not otherwise in the EHR.

Opening Portal Messages

Overall, 18 796 of 35 916 patients (52.3%) in the fixed monthly reminder arm who were sent messages opened at least 1; 2602 of 3966 (65.6%) in the responsive portal reminder arm who were sent a follow-up message opened it. We do not report vaccination rates among patients who opened portal messages given that overall findings revealed no effect; positive effects within a subgroup would diminish but not remove an overall effect.

Preappointment Reminders

Overall, 19 254 patients (22.0%) in the portal arm and 19 109 patients (21.9%) in the text arm had at least 1 primary care visit after initiation of preappointment reminders and were unvaccinated before the first visit.

Patient Complaints

We received 1 complaint from a patient who had been vaccinated externally but still sent a reminder. The vaccination was not in the UCLA EHR.

Discussion

This trial found that portal messages sent monthly or before scheduled visits did not increase influenza vaccination rates across a health system. There were no statistically significant differences between text vs portal messages, although text messaging for preappointment reminders had a higher aRR than portal messages. Finally, portal reminders responding to patients’ plans for vaccination were not more successful than monthly fixed reminders. At the population level, neither portal nor text reminders for influenza vaccination were effective.

This study makes 2 important additions to the literature on preappointment reminders. First, prior studies of preappointment text reminders by health care systems have assessed vaccinations received at the upcoming visit20,21,31 but not end-of-season vaccination rates. Our findings that end-of-season vaccination rates remained higher among patients sent preappointment texts add to the literature. Second, a much-cited study21 noted the impact of certain preappointment text reminders on the subgroup of vaccine-eligible patients with scheduled non–illness-related visits.31 Given that only one-fifth of our population was in that subgroup (about half had a scheduled visit and half of them had already been vaccinated), the impact was diminished at the population level, but it might be enhanced if more patients had scheduled visits during the influenza vaccination season.

We suspect there are several reasons why text, but not portal, preappointment reminders were effective among the subgroup of unvaccinated patients with appointments. Portal messages require patients to open the portal and find and then read the message, whereas text messages appear instantly and might appear more urgent or important.19

Our negative findings for monthly text or portal reminders add to the literature on patient vaccine reminders. While Cochrane reviews8 and many studies found influenza vaccine reminders to be beneficial (particularly for low-income populations, children, and for text messaging),32,33 other recent studies found small or no impact of centralized reminders for influenza, COVID-19, and other vaccines.12,13,14,25,34 The impact of reminders likely depends on multiple factors: (1) patient predisposition to being vaccinated, (2) educational value of messaging, (3) effectiveness of nudging, and (4) practical barriers or facilitators. We suspect the UCLA Health population has knowledge about influenza vaccination, has ready access to influenza vaccines from pharmacies and primary care, and has largely decided about vaccination, limiting the impact of low-intensity messaging at the population level. For children needing a second vaccine, reminders are highly beneficial35,36 probably because many parents are unaware of the need for 2 vaccinations. Thus, behavioral economic strategies (eg, message framing, personalization, scarcity, urgency, appeal to authority) may not be effective12,13,14 except where knowledge is lacking. In other settings or for other vaccines for which patients are undecided about vaccination, or if education is needed, centralized messaging may be more effective. Health systems should consider the potential opportunity costs of sending reminders for influenza vaccination and may decide on other, more intensive interventions, such as improving access to vaccinations (eg, Saturday or after-hour clinics) or communication training for clinicians to address vaccine hesitancy.

Strengths and Limitations

Study strengths include large, pragmatic RCT; randomization within practices to reduce confounders; high EHR capture of influenza vaccination; and simultaneous assessment of multiple interventions. Study limitations include a single health system (albeit a large one), inability to test responsive text reminders, and inability to assess why patients were not vaccinated. Portal and text messages were in English, but 98% of the population listed English as their preferred portal language. While 85% of UCLA Health patients were eligible, findings cannot generalize to the remaining 15%. Finally, while we received 1 emailed patient complaint, we did not measure potential harms from our intervention, such as whether patients ignored other health system messages.

Conclusions

In this large health system, text message monthly or preappointment reminders for influenza vaccination did not perform better than portal reminders at the population level. Patient portal messaging may not be an effective strategy to raise influenza vaccination rates, but text message preappointment reminders can be effective for patients with scheduled appointments. While patient reminders for influenza vaccine have worked in the past and in other settings, they may no longer work at the population level. More intensive interventions are needed overall to raise influenza vaccination rates to meet national goals.

Trial Protocol

eAppendix. Examples of Patient Portal and Text Messages

eTable 1. Demographic Characteristics of Individuals Who Were Included or Not Included in the Study

eTable 2. Cox Proportional Hazards Model, With Random Practice Effects, to Evaluate the Time to Influenza Vaccination

eTable 3. Subgroup Analysis of the Impact of Preappointment Reminders Among Patients Who Had at Least 1 Visit During the Study Period

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Grohskopf LA, Alyanak E, Broder KR, et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices—United States, 2020-21 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2020;69(8):1-24. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6908a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2022-2023 US flu season: preliminary in-season burden estimates. Accessed June 14, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/burden/preliminary-in-season-estimates.htm

- 3.Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Broder KR, Walter EB, Fry AM, Jernigan DB. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices–United States, 2018-19 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67(3):1-20. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6703a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Flu vaccination coverage, United States, 2021–22 influenza season. Accessed June 14, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-2022estimates.htm

- 5.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Weekly flu vaccination dashboard. Accessed June 14, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/dashboard/vaccination-dashboard.html

- 6.Briss PA, Rodewald LE, Hinman AR, et al. ; The Task Force on Community Preventive Services . Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to improve vaccination coverage in children, adolescents, and adults. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(1)(suppl):97-140. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(99)00118-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guide to Community Preventive Services . Using The Community Guide. Updated April 18, 2023. Accessed June 14, 2023. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/pages/using-community-guide.html

- 8.Jacobson Vann JC, Jacobson RM, Coyne-Beasley T, Asafu-Adjei JK, Szilagyi PG. Patient reminder and recall interventions to improve immunization rates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;1(1):CD003941. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003941.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edwards GW, Gonzales MJ, Sullivan MA. Robocalling: stirred and shaken!—an investigation of calling displays on trust and answer rates. Proceedings of the 2020 Chi Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Chi’20). April 2020. doi: 10.1145/3313831.3376679 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anthony DL, Campos-Castillo C, Lim PS. Who isn’t using patient portals and why? evidence and implications from a national sample of US adults. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(12):1948-1954. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antonio MG, Petrovskaya O, Lau F. The state of evidence in patient portals: umbrella review. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(11):e23851. doi: 10.2196/23851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szilagyi PG, Albertin C, Casillas A, et al. Effect of patient portal reminders sent by a health care system on influenza vaccination rates: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(7):962-970. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szilagyi PG, Albertin CS, Casillas A, et al. Effect of personalized messages sent by a health system’s patient portal on influenza vaccination rates: a randomized clinical trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(3):615-623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szilagyi PG, Casillas A, Duru OK, et al. Evaluation of behavioral economic strategies to raise influenza vaccination rates across a health system: results from a randomized clinical trial. Prev Med. 2023;170:107474. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2023.107474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stockwell M. Effect of a nationwide intervention of electronic letters with behavioural nudges on influenza vaccination in older adults in Denmark. Lancet. 2023;401(10382):1058-1060. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00453-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofstetter AM, Vargas CY, Camargo S, et al. Impacting delayed pediatric influenza vaccination: a randomized controlled trial of text message reminders. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(4):392-401. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stockwell MS, Hofstetter AM, DuRivage N, et al. Text message reminders for second dose of influenza vaccine: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1):e83-e91. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stockwell MS, Kharbanda EO, Martinez RA, Vargas CY, Vawdrey DK, Camargo S. Effect of a text messaging intervention on influenza vaccination in an urban, low-income pediatric and adolescent population: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;307(16):1702-1708. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stockwell MS, Westhoff C, Kharbanda EO, et al. Influenza vaccine text message reminders for urban, low-income pregnant women: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(Suppl 1)(suppl 1):e7-e12. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buttenheim A, Milkman KL, Duckworth AL, Gromet DM, Patel M, Chapman G. Effects of ownership text message wording and reminders on receipt of an influenza vaccination: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e2143388. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.43388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Milkman KL, Patel MS, Gandhi L, et al. A megastudy of text-based nudges encouraging patients to get vaccinated at an upcoming doctor’s appointment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(20):e2101165118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2101165118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szilagyi PG, Schaffer S, Rand CM, et al. Text message reminders for child influenza vaccination in the setting of school-located influenza vaccination: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2019;58(4):428-436. doi: 10.1177/0009922818821878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herrett E, Williamson E, van Staa T, et al. Text messaging reminders for influenza vaccine in primary care: a cluster randomised controlled trial (TXT4FLUJAB). BMJ Open. 2016;6(2):e010069. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brillo E, Tosto V, Buonomo E. Interventions to increase uptake of influenza vaccination in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2023;162(1):39-50. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.14714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szilagyi PG, Albertin CS, Saville AW, et al. Effect of state immunization information system based reminder/recall for influenza vaccinations: a randomized trial of autodialer, text, and mailed messages. J Pediatr. 2020;221:123-131.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.02.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Austin J, Sigurdsson SO, Rubin YS. An examination of the effects of delayed versus immediate prompts on safety belt use. Environ Behav. 2006;38(1):140-149. doi: 10.1177/0013916505276744 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bogard JE, Fox CR, Goldstein N. The Implied Exclusivity Effect: Promoting Choice Through Reserved Labeling. Working Paper, Washington University of St. Louis. 2023.

- 28.Rogers T, Milkman KL, John LK, Norton MI. Beyond good intentions: prompting people to make plans improves follow-through on important tasks. Behav Sci Policy. 2015;1(2):33-41. doi: 10.1177/237946151500100205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Milkman KL, Beshears J, Choi JJ, Laibson D, Madrian BC. Using implementation intentions prompts to enhance influenza vaccination rates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(26):10415-10420. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103170108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cialdini RB. Influence: Science and Practice. 5th ed. Pearson Education; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patel MS, Milkman KL, Gandhi L, et al. A randomized trial of behavioral nudges delivered through text messages to increase influenza vaccination among patients with an upcoming primary care visit. Am J Health Promot. 2023;37(3):324-332. doi: 10.1177/08901171221131021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kempe A, Stockwell MS, Szilagyi P. The contribution of reminder-recall to vaccine delivery efforts: a narrative review. Acad Pediatr. 2021;21(4S):S17-S23. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2021.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas RE, Lorenzetti DL. Interventions to increase influenza vaccination rates of those 60 years and older in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;5(5):CD005188. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005188.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kappes HB, Toma M, Balu R, et al. Using communication to boost vaccination: lessons for COVID-19 from evaluations of eight large-scale programs to promote routine vaccinations. Behav Sci Policy. 2023;9(1):11-24. doi: 10.1177/23794607231192690 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lerner C, Albertin C, Casillas A, et al. Patient portal reminders for pediatric influenza vaccinations: a randomized clinical trial. Pediatrics. 2021;148(2):e2020048413. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-048413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stockwell MS, Shone LP, Nekrasova E, et al. Text message reminders for the second dose of influenza vaccine for children: an RCT. Pediatrics. 2022;150(3):e2022056967. doi: 10.1542/peds.2022-056967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eAppendix. Examples of Patient Portal and Text Messages

eTable 1. Demographic Characteristics of Individuals Who Were Included or Not Included in the Study

eTable 2. Cox Proportional Hazards Model, With Random Practice Effects, to Evaluate the Time to Influenza Vaccination

eTable 3. Subgroup Analysis of the Impact of Preappointment Reminders Among Patients Who Had at Least 1 Visit During the Study Period

Data Sharing Statement