ABSTRACT

Zinc is an important transition metal that is essential for numerous physiological processes while excessive zinc is cytotoxic. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a ubiquitous opportunistic human pathogen equipped with an exquisite zinc homeostatic system, and the two-component system CzcS/CzcR plays a key role in zinc detoxification. Although an increasing number of studies have shown the versatility of CzcS/CzcR, its physiological functions are still not fully understood. In this study, transcriptome analysis was performed, which revealed that CzcS/CzcR is silenced in the absence of the zinc signal but modulates global gene expression when the pathogen encounters zinc excess. CzcR was demonstrated to positively regulate the copper tolerance gene ptrA and negatively regulate the pyochelin biosynthesis regulatory gene pchR through direct binding to their promoters. Remarkably, the upregulation of ptrA and downregulation of pchR were shown to rescue the impaired capacity of copper tolerance and prevent pyochelin overproduction, respectively, caused by zinc excess. This study not only advances our understanding of the regulatory spectrum of CzcS/CzcR but also provides new insights into stress adaptation mediated by two-component systems in bacteria to balance the cellular processes that are disturbed by their signals.

IMPORTANCE

CzcS/CzcR is a two-component system that has been found to modulate zinc homeostasis, quorum sensing, and antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. To fully understand the physiological functions of CzcS/CzcR, we performed a comparative transcriptome analysis in this study and discovered that CzcS/CzcR controls global gene expression when it is activated during zinc excess. In particular, we demonstrated that CzcS/CzcR is critical for maintaining copper tolerance and iron homeostasis, which are disrupted during zinc excess, by inducing the expression of the copper tolerance gene ptrA and repressing the pyochelin biosynthesis genes through pchR. This study revealed the global regulatory functions of CzcS/CzcR and described a new and intricate adaptive mechanism in response to zinc excess in P. aeruginosa. The findings of this study have important implications for novel anti-infective interventions by incorporating metal-based drugs.

KEYWORDS: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, two-component system, CzcS/CzcR, zinc excess, copper tolerance, pyochelin biosynthesis

INTRODUCTION

Transition metal ions are present in almost all types of environments and they are essential for bacterial growth and pathogenesis owing that they play critical roles in numerous biological processes (1). However, variations in environmental concentrations of transition metals are ubiquitous, often causing stress to bacterial physiology. Metals are also toxic and even lethal to bacterial cells when they are depleted or in excess. Therefore, the administration of ion contents at the host-pathogen interface is an important strategy employed by animal hosts to defend against invading pathogens. For instance, iron (Fe) sequestration and copper (Cu) intoxication are commonly found in host immune cells such as macrophages and neutrophils (2).

Zinc (Zn) is the second most abundant transition metal which is utilized by a large percentage of proteins in bacteria and is an important factor for enzymatic catalysis and gene regulation (3). It is also detrimental when present in excess. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a Gram-negative bacterium that is prevalent in the environment. It is also an important opportunistic human pathogen and a leading cause of hospital-acquired infections (4). P. aeruginosa is known to be a metabolically versatile pathogen that is capable of adapting to and thriving under different environmental stresses with the help of its abundant signaling systems (5). To adapt to conditions with different Zn concentrations, the pathogen has developed several sophisticated signaling systems to stabilize intracellular Zn homeostasis by modulating the uptake, storage, and efflux of Zn ions (6). Among these, the two-component system (TCS) CzcS/CzcR is an essential one that employs CzcS to sense the extracellular signal Zn and subsequently activates CzcR to control the expression of Zn efflux proteins CzcCBA and CzcD, thereby alleviating intracellular Zn accumulation and toxicity (7–9).

In recent years, an increasing number of studies have revealed the role of CzcS/CzcR in the regulation of various virulence-related traits, such as biofilm formation, quorum sensing activity, swimming motility, as well as antibiotic resistance (10–13). These findings showed the versatility of CzcS/CzcR in addition to modulating Zn detoxification and implied that the physiological functions of the TCS may be greatly underestimated. Thus, a comprehensive investigation of the regulon of the Zn-responsive CzcS/CzcR and its physiological functions is desirable, which might broaden our understanding of the adaptive mechanism of P. aeruginosa and provide new implications for targeted anti-infective interventions. To this end, in this study, we performed a comparative transcriptome analysis between the PAO1 wild-type (WT) strain and the TCS mutant ΔczcR to explore the physiological roles of CzcS/CzcR in P. aeruginosa. In addition to genes related to Zn efflux and previously reported functions, it is surprisingly revealed that Zn activates CzcS/CzcR to control thousands of genes including those involved in other metal-associated cellular processes such as Cu tolerance and Fe uptake.

RESULTS

Zn activates CzcS/CzcR to modulate global gene expression

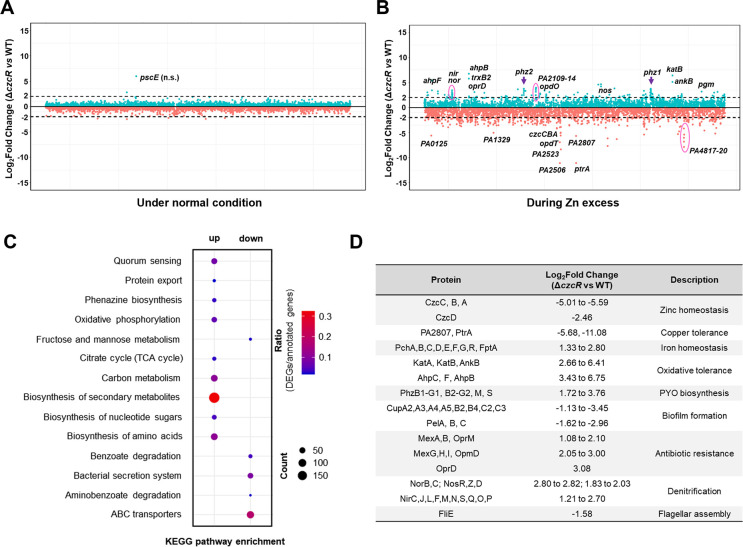

To comprehensively understand the regulatory roles of the Zn-responsive TCS CzcS/CzcR in P. aeruginosa, we first conducted a comparative transcriptome analysis between the PAO1 WT and ΔczcR strains after they were cultured in the LB medium. However, we did not observe any genes with significantly different expression levels between the two strains (Fig. 1A), suggesting that disruption of the TCS CzcS/CzcR did not affect the transcriptome of P. aeruginosa under normal conditions. This was consistent with previous studies showing that expression and activation of CzcS/CzcR require the presence of the inducing signal Zn (9, 14). We then monitored the growth of the WT and ΔczcR strains and the activity of PczcC, a promoter under the direct control of CzcR, in the WT and ΔczcR strains when both strains were cultured in the presence of Zn at different concentrations. It was shown that the final biomasses between the WT and ΔczcR strains were not significantly different under Zn treatment until the concentration of Zn was higher than 0.5 mM (Fig. S1A). Notably, the activity of PczcC was continuously induced in the WT strain with the increasing concentration of Zn up to 0.5 mM (Fig. S1B). Therefore, we repeated the comparative transcriptome analysis by culturing the WT and ΔczcR strains with supplementation of 0.5 mM Zn in the medium. It was shown that the transcriptome profiles of these two strains were dramatically different during Zn excess (Fig. 1B). A total of 2,653 genes were differentially expressed in the ΔczcR mutant compared to that in the WT strain with P value < 0.05 (Table S1). Among them, 1,371 genes were upregulated and 1,282 genes were downregulated by the deletion of czcR. Enrichment analysis based on the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways showed that these differentially expressed genes were mainly enriched in 14 pathways (Fig. 1C). Genes upregulated in the ΔczcR mutant were mainly enriched in quorum sensing, protein export, phenazine biosynthesis, oxidative phosphorylation, citrate cycle (TCA cycle), carbon metabolism, biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, biosynthesis of nucleotide sugars, biosynthesis of amino acids, and genes downregulated in the ΔczcR mutant were mainly enriched in fructose and mannose metabolism, benzoate degradation, bacterial secretion system, aminobenzoate degradation, and ABC transporters. As selectively listed in Fig. 1D, in addition to the previously reported functions of CzcS/CzcR in regulating Zn efflux, pyocyanin (PYO) biosynthesis, biofilm formation, flagellar assembly, and antibiotic resistance, CzcS/CzcR was also shown to modulate many other physiological processes, such as Cu tolerance, Fe homeostasis, oxidative tolerance, and denitrification.

Fig 1.

CzcS/CzcR modulates global gene expression during Zn excess. (A and B) Genome-wide transcriptomic profiles of the PAO1 WT strain and the ΔczcR mutant when they were cultured under the normal condition (A) or with the supplementation of 0.5 mM ZnSO4 (B). Green dots were the genes upregulated in the ΔczcR mutant, and orange dots were the genes downregulated in the ΔczcR mutant. The black dot lines represented 2-Log2Fold expression changes. Genes with dramatic differences in expression were selectively labeled. (C) KEGG pathway enrichment of genes that were upregulated and downregulated in the ΔczcR mutant. The size of the dot represented the number of genes in the pathways. (D) Representative upregulated and downregulated genes in the ΔczcR mutant with different biological functions were displayed.

Expression of Cu tolerance genes ptrA and PA2807 is directly controlled by CzcS/CzcR

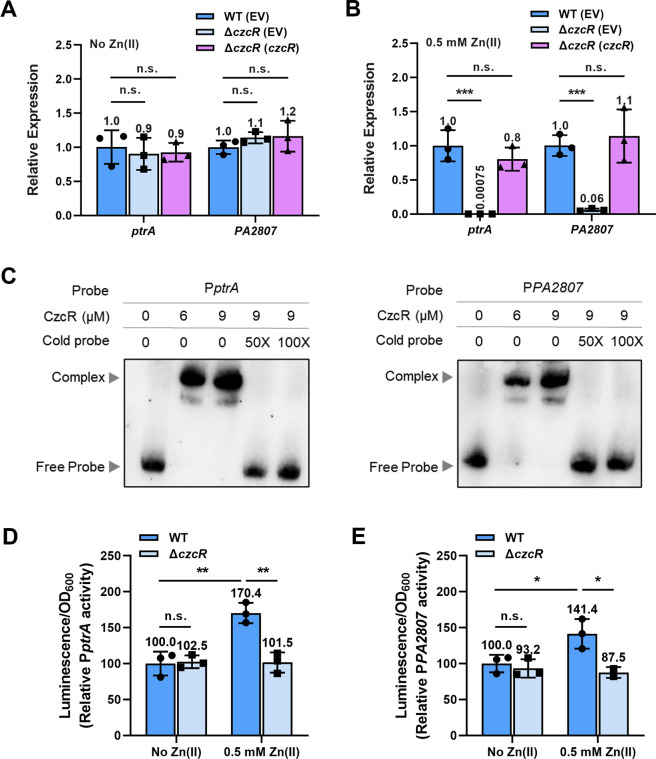

PtrA is a small periplasmic protein that is involved in Cu tolerance (15). Consistent with previous observations (8, 11), our transcriptome result showed that ptrA was one of the most downregulated genes in the ΔczcR mutant during Zn excess with even higher fold changes than genes involved in Zn efflux (Fig. 1B). A cupredoxin-like protein PA2807, which has also been reported to be involved in Cu tolerance (8, 16), was also expressed at a dramatically lower level in the ΔczcR mutant than that in the WT strain, suggesting that CzcS/CzcR may play an important role in Cu tolerance. We performed reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) to verify the expression of ptrA and PA2807 in the WT strain and the ΔczcR mutant. As shown in Fig. 2A, there was no significant difference in the expression levels of ptrA and PA2807 between the two strains when they were cultured without the presence of Zn. Similar to the transcriptome result, the expression of both genes in the ΔczcR mutant was substantially lower than that in the WT strain when the strains were cultured in the presence of Zn and the reduced expression of two genes in the ΔczcR mutant could be fully restored to the WT level with the complementation of czcR (Fig. 2B), confirming that CzcS/CzcR positively regulates the expression of ptrA and PA2807 in the presence of Zn. In addition to ptrA and PA2807, we also wondered if CzcS/CzcR regulates the expression of other genes involved in Cu tolerance. However, in the transcriptome result, we did not find obvious changes in the expression of other Cu tolerance genes (Table S1). Moreover, RT-qPCR also showed no obvious changes in the expression levels of several important Cu tolerance genes, such as pcoA, pcoB, copA1, and copA2 (Fig. S2).

Fig 2.

CzcS/CzcR induces the expression of ptrA and PA2807 during Zn excess. (A and B) Relative expression of the ptrA and PA2807 genes in the ΔczcR and ΔczcR (czcR) strains compared to the WT strain when they were cultured in the absence (A) or the presence (B) of Zn. (C) Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) showed the binding ability of CzcR at the promoters of ptrA and PA2807. (D and E) Expression of PptrA-lux (D) and PPA2807-lux (E) was measured in the WT and ΔczcR strains when they were cultured in the absence or presence of Zn. Statistical significance was calculated compared to the WT group based on one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (A and B) or two-way ANOVA (D and E) (n.s., not significant; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

Previous semi-quantitative RT-PCR showed that ptrA (PA2808) and PA2807 are located in the same operon which produces a polycistronic ptrA-PA2807 mRNA (8). Since CzcR is a transcription factor that has been demonstrated to regulate PYO production, swimming motility, and antibiotic resistance by directly binding to promoters of target genes (10, 13, 14), we then purified CzcR and conducted electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) to explore if CzcR regulated ptrA and PA2807 by binding to their promoters. CzcR was first shown to bind to the promoter of czcCBA (PczcC, positive control) but not to the coding region of czcC (negative control) (Fig. S3), suggesting the specificity of interactions between CzcR and target DNA sequences. Next, promoter regions of ptrA and PA2807 genes were examined, and interestingly, EMSAs showed the binding of CzcR to both promoter regions (Fig. 2C). These results not only demonstrated that CzcR binds directly to the promoter of ptrA (PptrA) to induce its transcription, but also indicated that PA2807 can be transcribed from its own promoter PPA2807 in addition to PptrA. To further validate the presence of PPA2807 which drives the transcription of PA2807, we generated a PPA2807-lux fusion to quantify its transcriptional activity. As with the promoter of ptrA, the activity of the PPA2807 was significantly reduced by the deletion of czcR when strains were cultured in the presence of Zn (Fig. 2D and E), confirming that CzcR activates the transcription of a monocistronic PA2807 mRNA in addition to the polycistronic ptrA-PA2807 mRNA.

CzcS/CzcR maintains Cu tolerance through PtrA during Zn excess

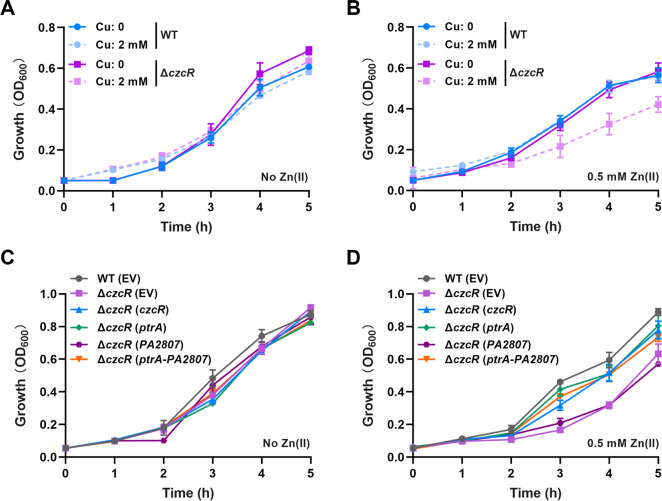

Owing that both PtrA and PA2807 proteins were annotated for Cu tolerance, we speculated that CzcS/CzcR might upregulate these two genes to elevate the tolerance of P. aeruginosa to Cu stress. To first test this speculation, we examined the growth of WT and ΔczcR strains in the absence and presence of 2 mM CuSO4. As shown in Fig. 3A, there was no growth difference between the strains without Zn pretreatment when they were cultured in the both absence and presence of CuSO4. However, the deletion of czcR caused an obvious growth defect when the mutant was pretreated with Zn and then grown in the presence of CuSO4 (Fig. 3B), indicating the importance of CzcS/CzcR in maintaining Cu tolerance during Zn excess. To investigate if the reduced expression levels of ptrA and PA2807 led to the susceptibility of ΔczcR to Cu, we overexpressed ptrA, PA2807, and the combination of ptrA and PA2807, respectively, in the ΔczcR mutant (Fig. 3C and D). It was shown that Cu tolerance of the ΔczcR mutant was enhanced to the WT level with the overexpression of ptrA or the simultaneous overexpression of ptrA and PA2807 (Fig. 3D and S4). However, the ΔczcR mutant with overexpression of PA2807 alone showed no growth difference as the mutant that contained the empty vector (EV) in the cell (Fig. 3D and S4), implying that CzcS/CzcR modulates Cu tolerance through PtrA during Zn excess.

Fig 3.

CzcS/CzcR positively regulates Cu tolerance through PtrA during Zn excess. (A) Growth of the WT strain and the ΔczcR mutant in the presence or absence of 2 mM CuSO4 when the strains were not pretreated with Zn. (B) Growth of the WT strain and the ΔczcR mutant in the presence or absence of 2 mM CuSO4 after the strains were pretreated with Zn. (C) Growth of the WT strain, ΔczcR mutant, and the ΔczcR mutant with the overexpression of ptrA, PA2807, or ptrA-PA2807 in the presence of 2 mM CuSO4 when the strains were not pretreated with Zn. (D) Growth of the WT strain, ΔczcR mutant, and the ΔczcR mutant with the overexpression of ptrA, PA2807, or ptrA-PA2807 in the presence of 2 mM CuSO4 after the strains were pretreated with Zn.

Fig 4.

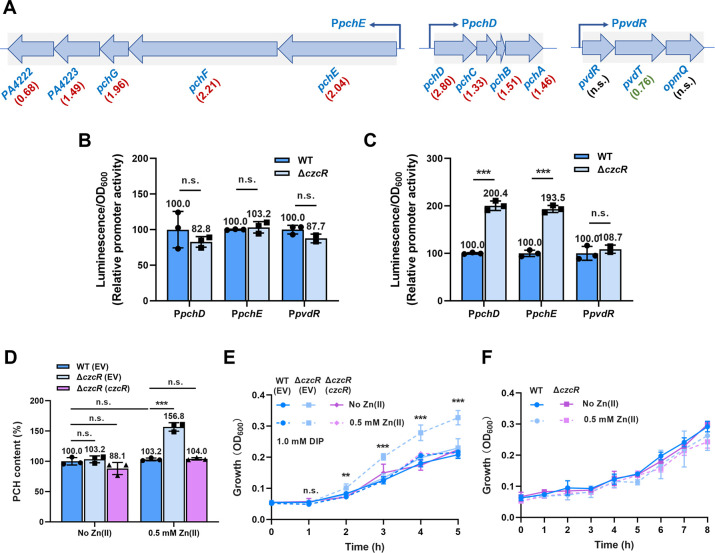

Loss of CzcS/CzcR signaling induces pyochelin production and promotes cell growth under Fe depletion and Zn excess conditions. (A) Three gene clusters involved in pyochelin (PCH) biosynthesis (pchE/pchF/pchG/PA4223/PA4222 and pchD/pchC/pchB/pchA) and pyoverdine (PVD) transportation (pvdR/pvdT/opmQ) were shown. Values underneath gene names indicate Log2Fold changes of gene expression in the ΔczcR mutant relative to that in the WT strain. Red and green colors indicated the upregulated and downregulated gene expression in the ΔczcR mutant, respectively. (B and C) Expression of PpchD-lux, PpchE-lux, and PpvdR-lux was measured in the WT and ΔczcR strains when they were cultured in the absence (B) or presence (C) of Zn. (D) Production of PCH was measured in WT and ΔczcR strains when they were cultured in the absence or presence of Zn. (E) Growth of the WT strain, ΔczcR mutant, and the ΔczcR mutant with the complementation of czcR in the presence of 1.0 mM 2,2’-dipyridyl (DIP) when the strains were pretreated or not pretreated with Zn. (F) Growth of WT and ΔczcR strains with or without Zn pretreatment in the minimal medium without Fe supplementation. Statistical significance was calculated compared to the WT group based on Student’s t-test (B and C) and two-way ANOVA (D and E) (n.s., not significant; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

It is interesting to notice that the promoter activities of both ptrA and PA2807 were upregulated by Zn in the WT strain (Fig. 2D and E). However, the growth of the WT strain during Cu stress was almost unchanged with or without Zn pretreatment (Fig. 3C, D, and S4). These results suggested that the physiological function of CzcS/CzcR-upregulated ptrA is maintaining the capability of Cu tolerance which is impaired by excessive Zn through CzcS/CzcR-independent pathways.

Zn and CzcS/CzcR reversely modulate pyochelin biosynthesis

In addition to Cu tolerance, the transcriptome result showed that the expression of multiple genes associated with the biosynthesis and transportation of pyochelin (PCH) and pyoverdine (PVD), two major siderophores playing important roles in Fe uptake (17), was different between WT and ΔczcR strains. Among them, most genes involved in PCH biosynthesis or transportation such as pchA, pchB, pchC, pchD, pchE, pchF, pchG, pchR, and fptA were induced at least by 2.51-fold in the ΔczcR mutant (Fig. 1D). In contrast, a small group of genes involved in PVD biosynthesis or transportation were slightly changed by the deletion of czcR with some of them such as pvdA and pvdO were upregulated by 1.49 and 2.27-fold, while some of them such as pvdD, pvdL, pvdF, and pvdT were downregulated by 2.28, 1.71, 1.85, and 1.69-fold, respectively (Table S1). These results suggested that CzcS/CzcR may also play a role in modulating Fe homeostasis.

To verify whether CzcS/CzcR regulates PCH and PVD productions, we selected some genes or operons (pchE/pchF/pchG/PA4223/PA4222, pchD/pchC/pchB/pchA, pvdR/pvdT/opmQ, Fig. 4A) involved in PCH biosynthesis and PVD transportation to construct promoter-lux transcription fusions and examine their transcriptional activities. It was shown that promoter activities of the PCH biosynthetic operons, i.e., PpchD and PpchE, were significantly elevated by the deletion of czcR in the presence but not absence of Zn (Fig. 4B and C). However, promoter activities of the PVD transporter gene operon PpvdR between WT and ΔczcR strains were not significantly different in both the presence and absence of Zn (Fig. 4B and C). These results suggested that CzcS/CzcR controls PCH biosynthesis. We next measured PCH and PVD productions in WT and ΔczcR strains. Consistent with the gene expression result, it was shown that PCH production was significantly higher in the ΔczcR mutant compared to the WT strain when they were cultured with Zn while there was no difference in PVD production between two strains (Fig. 4D and S5). Interestingly, it was also noticed that productions of PCH were not significantly different between the WT strains with or without Zn treatment (Fig. 4D), implying that Zn induces PCH biosynthesis independent of CzcS/CzcR while CzcS/CzcR simultaneously represses PCH biosynthesis.

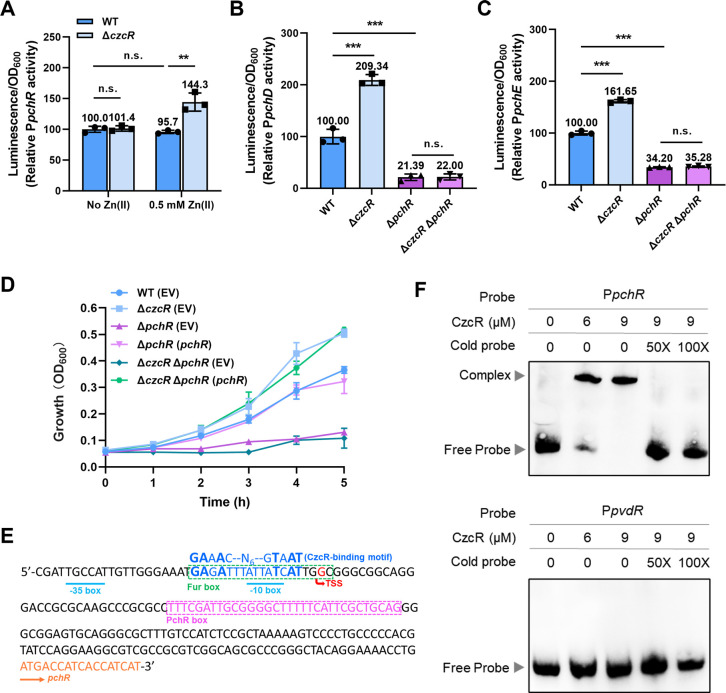

Fig 5.

CzcS/CzcR represses PCH biosynthetic gene expression by inhibiting the expression of pchR. (A) Expression of PpchR-lux was measured in the WT and ΔczcR strains when they were cultured in the absence or presence of Zn. (B and C) Expression of PpchD-lux (B) and PpchE-lux (C) was measured in the WT, ΔczcR, ΔpchR, and ΔczcR ΔpchR strains when they were cultured in the presence of Zn. (D) Growth of the WT(EV), ΔczcR(EV), ΔpchR(EV), ΔpchR(pchR), ΔczcR ΔpchR(EV), and ΔczcR ΔpchR(pchR) strains in the presence of 1.0 mM DIP when the strains were pretreated with Zn. (E) Prediction of the CzcR-binding site in the promoter of pchR. (F) EMSAs showed the binding ability of CzcR at the promoter of pchR (PpchR) but not the promoter of pvdRT-opmQ (PpvdR). Statistical significance was calculated compared to the indicated groups based on two-way ANOVA (A) or one-way ANOVA (B and C) (n.s., not significant; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

CzcS/CzcR inhibits cell growth during Fe depletion and Zn excess

Given that the function of PCH is to acquire Fe from the extracellular environment and Fe is indispensable for optimal bacterial growth, we then sought to explore whether the increased production level of PCH in ΔczcR will benefit its growth under Fe-depleted conditions. Growth of the WT and ΔczcR strains were monitored under Fe-depleted conditions which were generated by supplementing the Fe chelator 2,2’-dipyridyl (DIP) in the medium (18). When DIP was added in the medium at the concentration of 0.5 mM, growth of the WT and ΔczcR strains remained similar no matter whether the two strains were pretreated with Zn or not (Fig. S6). Noticeably, when DIP concentration was increased to 1.0 mM, the ΔczcR mutant grew faster than the WT strain after Zn pretreatment despite the growth of both strains being inhibited by the high concentration of DIP (Fig. 4E and S6B). Consistent with the unchanged level of PCH production, there was no detectable difference in the growth of the WT strain with or without Zn pretreatment (Fig. 4E). Furthermore, when we replaced the culture medium with a minimal medium that did not contain Fe, the growth advantage of ΔczcR in the presence of Zn was fully abolished (Fig. 4F). These results showed that Zn promotes cell growth through competitive acquisition of extracellular Fe by PCH when the extracellular Fe concentration is depleted to a certain content, while this process could be counteractively inhibited by CzcS/CzcR. Under Fe-sufficient conditions, overproduction of PCH owing to the disruption of CzcS/CzcR did not cause any beneficial effects on cell growth.

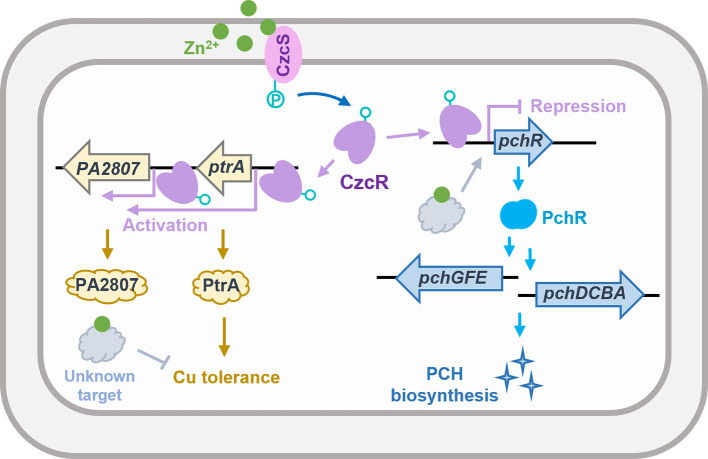

Fig 6.

A schematic diagram showing the regulation of Cu tolerance and PCH biosynthesis by CzcS/CzcR during Zn excess in P. aeruginosa. Zn excess disrupts P. aeruginosa tolerance to Cu, while simultaneously, CzcS/CzcR is activated which induces the expression of ptrA to remedy the capability of P. aeruginosa to tolerate Cu stress. Zn is also shown to induce the expression of pchR, which leads to the overproduction of PCH and enhanced growth under Fe-depleted conditions. Concurrently, CzcS/CzcR antagonizes the induction of pchR during Zn excess by the direct binding of CzcR to the promoter of pchR to inhibit its expression.

CzcS/CzcR represses pchR to inhibit the expression of PCH biosynthetic genes

PCH biosynthesis in P. aeruginosa is activated by PchR which is a transcription factor belonging to the AraC-type family (19). The transcriptome result showed that the deletion of czcR not only caused the upregulation of PCH biosynthetic genes but also the induced expression of the gene encoding PchR (Fig. 1D). This led us to ask whether the upregulation of PchR activates PCH biosynthesis in ΔczcR. Promoter activity assay firstly confirmed the upregulation of pchR by the deletion of czcR when strains were cultured in the presence of Zn (Fig. 5A). In addition, the unchanged promoter activity of pchR in the WT strain after treatment of Zn was consistent with the unchanged production of PCH (Fig. 4D).

We then constructed the mutants ΔpchR and ΔczcR ΔpchR and measured the activity of promoters PpchD and PpchE in these strains when they were cultured in the presence of Zn. Deletion of pchR substantially inhibited the activity of both promoters (Fig. 5B and C), suggesting the key role of PchR in activating pch gene expression. Unlike the activation of both promoters by deleting czcR in the WT strain, deletion of czcR in the ΔpchR mutant did not induce the activity of the two promoters (Fig. 5B and C). Consistently, growth of the Zn-pretreated ΔpchR mutant was fully inhibited in the presence of 1.0 mM DIP and could not be promoted by further deleting czcR (Fig. 5D), indicating that the Zn-activated CzcS/CzcR inhibits cell growth under the Fe-depleted condition by repressing pchR.

Transcription of pchR is modulated by the ferric uptake regulator Fur as well as its product PchR. A Fur-binding region (Fur box) and a PchR-binding region (PchR box) were previously identified upstream of the pchR gene (Fig. 5E) (19). Since a 16-bp CzcR-binding motif was determined using the chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing assay (20), we searched for potential CzcR-binding sites in the promoter of pchR by aligning the promoter sequence with the 16-bp CzcR-binding motif. Sequence alignment revealed a potential CzcR-binding site overlapping with the Fur box and the −10 box in the pchR promoter (Fig. 5E), suggesting that CzcR may regulate pchR expression by directly interacting with its promoter. In agreement with this analysis, EMSAs showed that CzcR can directly bind to the promoter of pchR (PpchR) but not the control promoter PpvdR (Fig. 5F). Taken together, these results demonstrated that CzcS/CzcR inhibits the expression of PCH biosynthetic genes by repressing pchR during Zn excess.

DISCUSSION

Zn is an important transition metal that is associated with numerous biological processes in all kingdoms of life. Although bacterial cells require sufficient Zn to support their growth, excessive Zn is also toxic which frequently competes with other metals or disrupts central carbon metabolism (21). Zn has great antimicrobial activity and the release of Zn from damaged or apoptotic cells and metallothionein is known to be an important line of defense during bacterial infection (22–25). P. aeruginosa can survive and thrive in different host environments, and the TCS CzcS/CzcR plays an important role in regulating genes involved in Zn detoxification. In addition to Zn efflux, accumulating evidence has indicated that the physiological functions of CzcS/CzcR in P. aeruginosa are still not fully understood. In the present study, we performed comparative transcriptome analysis to comprehensively investigate the regulatory function of CzcS/CzcR and found its global regulatory effects on 2,653 genes. Focusing on various metal-associated cellular processes, we revealed the molecular details about the upregulation of the Cu tolerance gene ptrA and downregulation of the pyochelin biosynthesis regulatory gene pchR under the control of CzcS/CzcR during Zn excess. More interestingly, we further demonstrated that ptrA is upregulated to rescue the impaired capacity of Cu tolerance, and pchR is downregulated to prevent pyochelin overproduction during Zn excess (Fig. 6).

Crosstalk of Zn and Fe homeostatic systems has been reported in some bacterial species (26, 27), but connections between these two metal homeostatic systems in P. aeruginosa are rarely known. In this study, we found that the production of PCH involved in Fe uptake is not influenced by Zn excess in the PAO1 WT strain, while interestingly, its production can be induced by Zn in the mutant lacking CzcS/CzcR. This finding displays the importance of CzcS/CzcR in maintaining Fe homeostasis in P. aeruginosa when the pathogen encounters Zn excess. Induced PCH production in the ΔczcR mutant is ascribed to the de-repression of pchR, a gene encoding the PCH biosynthesis regulatory protein PchR. Transcriptional expression of pchR is positively regulated by Fur and PchR. Sequence analysis showed that the CzcR-binding motif is overlapped with the Fur box at the −10 box which is located upstream of the PchR box in the promoter region, it is possible that the expression of pchR and PCH biosynthetic genes are reversely regulated by CzcR and Fur during Zn excess and consequently the production of PCH in the PAO1 WT strain is not affected during Zn excess.

Since Fe is the most abundant metal ion that is indispensable for many essential cellular processes such as DNA replication and oxygen transport (28), the ability to acquire Fe from the environment is critical for the survival of pathogens, especially at the host-pathogen interface. We demonstrated that the increased production of PCH was indeed beneficial for cell growth under Fe-depleted conditions. It is curious why P. aeruginosa activates CzcS/CzcR to inhibit the overproduction of PCH caused by Zn. We speculated that the Zn-activated CzcS/CzcR inhibits PCH biosynthesis to prevent excessive PCH production and Fe acquisition when Fe is sufficient. Because PCH and Fe accumulation could be harmful to cells by inducing the production of intracellular reactive oxygen species and causing oxidative damage through the Fenton reaction (29, 30), this is supported by the result that most oxidative tolerance genes including katA, katB, ankB, ahpC, ahpF, and ahpB in the ΔczcR mutant were upregulated (Fig. 1D). We thus expected that the lack of CzcS/CzcR would increase the cellular tolerance to oxidative stress during Zn excess. However, we noticed that the ΔczcR mutant exhibited lower tolerance to H2O2-induced oxidative stress than the WT strain, and the altered susceptibility to H2O2 does not seem to be ascribed to PCH or Fe accumulation because the ΔczcR ΔpchR mutant still exhibited the same growth pattern as the ΔczcR mutant (Fig. S7).

Association between Zn excess and Cu tolerance in P. aeruginosa has been previously linked to PtrA and PA2807, which not only suggested the importance of PtrA and PA2807 in activating Cu tolerance during Zn excess but also showed the co-transcription of ptrA and PA2807 from the same promoter PptrA (8). Here, we further showed that PA2807 is also transcribed from its own promoter which can be directly targeted by CzcR. Although both ptrA and PA2807 are annotated for Cu tolerance, we demonstrated that only ptrA contributes to Cu tolerance in the ΔczcR mutant during Zn excess. Interestingly, ptrA is upregulated by Zn in the WT strain but enhanced Cu tolerance was not observed as we expected. Instead, we found that Cu tolerance of the ΔczcR mutant was compromised in the presence of Zn, meaning that the CzcS/CzcR-dependent upregulation of ptrA in P. aeruginosa represents a parallel pathway to rescue the capability of Cu tolerance destructed by Zn through unclear targets rather than to further elevate the level of Cu tolerance.

In summary, this study not only expanded our understanding of the large CzcS/CzcR regulon but also highlighted the importance of CzcS/CzcR in maintaining the balance of some cellular processes such as Cu tolerance and PCH biosynthesis in P. aeruginosa during Zn excess. Findings in this study might provide a new target of CzcS/CzcR for the development of anti-infective strategies by administrating concentrations of diverse metal ions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, primers, and growth conditions

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and primers are listed in Table S2. Luria-Bertani broth (Invitrogen) was used to culture bacterial cells. The medium was supplemented with 0.5 mM ZnSO4 for Zn treatment. Antibiotics were added for plasmid construction and propagation when required: tetracycline, 15 µg/mL; gentamycin, 50 µg/mL; kanamycin, 50 µg/mL for Escherichia coli DH5α, tetracycline, 15 µg/mL; kanamycin, 500 µg/mL for E. coli SM10, and tetracycline, 50 µg/mL; gentamycin, 50 µg/mL; kanamycin, 500 µg/mL for P. aeruginosa PAO1.

Construction of gene deletion mutants

Gene deletion was conducted using the chromosomally integrated type I-F CRISPR-Cas system (31). Briefly, an editing plasmid was first constructed which contains a mini-CRISPR to express a crRNA targeting a 32-bp protospacer in the gene and a donor fragment consisting of ~500-bp upstream and ~500-bp downstream sequences of the target gene. The editing plasmid was then introduced into PAO1IFλ through conjugation from E. coli SM10. The desired gene deletion was confirmed by PCR and Sanger sequencing. After gene deletion, the integrated type I-F CRISPR-Cas machinery was removed by an additional round of editing using the editing plasmid pAY7401.

RNA sequencing

PAO1 WT and ΔczcR strains were cultured in the presence or absence of Zn for 8 h until OD600 reached 2.0. Subsequently, 0.5 mL cell culture was then collected, and total RNA was extracted using the Eastep Super Total RNA Extraction Kit (Promega). Library construction and high-throughput sequencing were conducted using Illumina Novaseq 6000 at Novogene (Beijing, China). Quality control of raw reads was conducted using Trimmomatic v0.32 (32). Mapping of qualified reads was performed against the reference genome of PAO1 (NC_002516.2) using BWA v0.7.17-r1188 (33), SAMtools v1.15 (34), and bamkeepgoodreads of Stampy v1.0.32 (35). FeatureCounts of Subread v2.0.3 (36) was used to generate a count matrix which was submitted to DEseq2 (37) for identifying differentially expressed genes. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis was performed using clusterProfile v4.0 (38).

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

One milliliter bacterial culture was harvested by centrifugation after incubation in the presence or absence of Zn for 8 h. Total RNA was extracted, cDNA was reverse transcribed, and qPCR was performed using the Eastep Super Total RNA Extraction Kit (Promega), TransScript OneStep gDNA Removal and cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (TransGen), and the ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme), respectively. The housekeeping recA gene was used as the internal reference control. All experiments were conducted with three independent biological repeats.

Growth curve measurement

Overnight P. aeruginosa culture was 1:50 diluted into fresh LB broth with or without the supplementation of Zn and grown for 6 h. After adjusting the cell number to approximately 1 × 107, CuSO4 was added into the medium to a final concentration of 2 mM, DIP was added to the concentrations of 0.5 mM or 1.0 mM, and H2O2 was added to the concentration of 0.75 mM. Cell growth was monitored by measuring the OD600 value every 1 h. All experiments were conducted with three independent biological repeats.

Promoter activity assay

Promoter sequences were amplified by PCR using the genomic DNA of PAO1 as a template and then inserted between the HindIII and BamHI sites in the mini-CTX-lux plasmid. The promoter-lux fusions were integrated into the genomes of P. aeruginosa strains at the attB site by conjugation from the E. coli SM10 strain. Overnight cultures of P. aeruginosa strains containing promoter-lux fusions were 1:50 diluted into fresh LB broth with or without the presence of Zn. Luminescence and OD600 were monitored in a microplate reader (BioTek) after cells were grown for 6 h. All experiments were conducted with at least three independent biological repeats.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Expression of the His6-tagged CzcR in E. coli BL21(DE3) was induced by 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside. His6-tagged CzcR protein was purified with a Ni2+-affinity column (Smart-Lifesciences). Promoter fragments were first obtained by PCR using the genomic DNA of PAO1 as a template and then biotin-labeled by Biotin 3′ End DNA Labeling Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific). Each biotin-labeled promoter fragment with or without unlabeled promoter fragment (cold probe) was incubated with CzcR and then subjected to polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) was used to examine potential interactions between CzcR and target DNA fragments. Uncropped gel images of the EMSA results are shown in Fig. S8.

Measurement of PCH and PVD

For PCH measurement, P. aeruginosa strains was cultured with or without the supplementation of Zn for 8 h. PCH was extracted twice from the supernatant of the cell culture using an equal volume of acidified ethyl acetate (0.1% acetic acid). The organic phase was collected and dried with a centrifugal vacuum evaporator. The dried compounds were dissolved in 1 mL methanol (HPLC grade) for liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis using a Q Exactive Focus Hybrid Quadrupole-Orbitrap mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific). For PVD, P. aeruginosa strains was cultured in minimal medium (absence of sucrose) with or without the supplementation of Zn. After adjusting the cell number to approximately 1 × 109, PVD was quantified by measuring the absorbance of culture supernatants after the supernatants were 1:10 diluted in 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) at 405 nm using a spectrophotometer. All experiments were conducted with at least three independent biological repeats.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32100020 and 32370188), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (No. 2023A1515012775 and 2022 A1515010194), Guangzhou Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (No. 202201010613), and the Health and Medical Research Fund (No. 19201901).

Contributor Information

Zeling Xu, Email: zelingxu@scau.edu.cn.

Pablo Ivan Nikel, Danmarks Tekniske Universitet The Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Biosustainability, Kgs. Lyngby, Denmark.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The transcriptome data were deposited in the NCBI under the project accession number PRJNA896733.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.02327-23.

Supplemental figures and table.

List of differentially expressed genes (P<0.05) in the ΔczcR mutant compared to the wild-type strain as measured during Zn excess.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Palmer LD, Skaar EP. 2016. Transition metals and virulence in bacteria. Annu Rev Genet 50:67–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-120215-035146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Murdoch CC, Skaar EP. 2022. Nutritional immunity: the battle for nutrient metals at the host-pathogen interface. Nat Rev Microbiol 20:657–670. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022-00745-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Andreini C, Banci L, Bertini I, Rosato A. 2006. Zinc through the three domains of life. J Proteome Res 5:3173–3178. doi: 10.1021/pr0603699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Qin S, Xiao W, Zhou C, Pu Q, Deng X, Lan L, Liang H, Song X, Wu M. 2022. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: pathogenesis, virulence factors, antibiotic resistance, interaction with host, technology advances and emerging therapeutics. Signal Transduct Target Ther 7:199. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-01056-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Winstanley C, O’Brien S, Brockhurst MA. 2016. Pseudomonas aeruginosa evolutionary adaptation and diversification in cystic fibrosis chronic lung infections. Trends Microbiol. 24:327–337. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gonzalez MR, Ducret V, Leoni S, Perron K. 2019. Pseudomonas aeruginosa zinc homeostasis: key issues for an opportunistic pathogen. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech 1862:722–733. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2018.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Perron K, Caille O, Rossier C, Van Delden C, Dumas J-L, Köhler T. 2004. CzcR-CzcS, a two-component system involved in heavy metal and carbapenem resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Biol Chem 279:8761–8768. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312080200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ducret V, Abdou M, Goncalves Milho C, Leoni S, Martin-Pelaud O, Sandoz A, Segovia Campos I, Tercier-Waeber M-L, Valentini M, Perron K. 2021. Global analysis of the zinc homeostasis network in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and its gene expression dynamics. Front Microbiol 12:739988. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.739988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang D, Chen W, Huang S, He Y, Liu X, Hu Q, Wei T, Sang H, Gan J, Chen H. 2017. Structural basis of Zn(II) induced metal detoxification and antibiotic resistance by histidine kinase CzcS in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS Pathog 13:e1006533. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dieppois G, Ducret V, Caille O, Perron K. 2012. The transcriptional regulator CzcR modulates antibiotic resistance and quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS One 7:e38148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee J-H, Kim Y-G, Cho MH, Lee J. 2014. ZnO nanoparticles inhibit Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation and virulence factor production. Microbiol Res 169:888–896. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2014.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ducret V, Gonzalez MR, Scrignari T, Perron K. 2016. OprD repression upon metal treatment requires the RNA chaperone Hfq in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Genes (Basel) 7:82. doi: 10.3390/genes7100082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen S, Cao H, Xu Z, Huang J, Liu Z, Li T, Duan C, Wu W, Wen Y, Zhang LH, Xu Z. 2023. A type I-F CRISPRi system unveils the novel role of CzcR in modulating multidrug resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiol Spectr 11:e01123-23. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.01123-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liu Z, Xu Z, Chen S, Huang J, Li T, Duan C, Zhang LH, Xu Z. 2022. CzcR is essential for swimming motility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa during zinc stress. Microbiol Spectr 10:e0284622. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.02846-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Elsen S, Ragno M, Attree I. 2011. PtrA is a periplasmic protein involved in cu tolerance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 193:3376–3378. doi: 10.1128/JB.00159-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Quintana J, Novoa-Aponte L, Argüello JM. 2017. Copper homeostasis networks in the bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Biol Chem 292:15691–15704. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.804492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cornelis P, Dingemans J. 2013. Pseudomonas aeruginosa adapts its iron uptake strategies in function of the type of infections. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 3:75. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McHugh JP, Rodríguez-Quinoñes F, Abdul-Tehrani H, Svistunenko DA, Poole RK, Cooper CE, Andrews SC. 2003. Global iron-dependent gene regulation in Escherichia coli: a new mechanism for iron homeostasis. J Biol Chem 278:29478–29486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303381200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Michel L, González N, Jagdeep S, Nguyen-Ngoc T, Reimmann C. 2005. PchR-box recognition by the AraC-type regulator PchR of Pseudomonas aeruginosa requires the siderophore pyochelin as an effector. Mol Microbiol 58:495–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04837.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fan K, Cao Q, Lan L. 2021. Genome-wide mapping reveals complex regulatory activities of BfmR in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microorganisms 9:485. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9030485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ong CY, Walker MJ, McEwan AG. 2015. Zinc disrupts central carbon metabolism and capsule biosynthesis in Streptococcus pyogenes. Sci Rep 5:10799. doi: 10.1038/srep10799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Botella H, Peyron P, Levillain F, Poincloux R, Poquet Y, Brandli I, Wang C, Tailleux L, Tilleul S, Charrière GM, Waddell SJ, Foti M, Lugo-Villarino G, Gao Q, Maridonneau-Parini I, Butcher PD, Castagnoli PR, Gicquel B, de Chastellier C, Neyrolles O. 2011. Mycobacterial P1-type ATPases mediate resistance to zinc poisoning in human macrophages. Cell Host Microbe 10:248–259. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ong CY, Gillen CM, Barnett TC, Walker MJ, McEwan AG. 2014. An antimicrobial role for zinc in innate immune defense against group A Streptococcus. J Infect Dis 209:1500–1508. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Na-Phatthalung P, Min J, Wang F. 2021. Macrophage-mediated defensive mechanisms involving zinc homeostasis in bacterial infection. Infect Microbes Dis 3:175–182. doi: 10.1097/IM9.0000000000000058 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Eijkelkamp BA, Morey JR, Neville SL, Tan A, Pederick VG, Cole N, Singh PP, Ong C-LY, Gonzalez de Vega R, Clases D, Cunningham BA, Hughes CE, Comerford I, Brazel EB, Whittall JJ, Plumptre CD, McColl SR, Paton JC, McEwan AG, Doble PA, McDevitt CA. 2019. Dietary zinc and the control of Streptococcus pneumoniae infection. PLoS Pathog 15:e1007957. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Xu Z, Wang P, Wang H, Yu ZH, Au-Yeung HY, Hirayama T, Sun H, Yan A. 2019. Zinc excess increases cellular demand for iron and decreases tolerance to copper in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 294:16978–16991. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.010023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Xu FF, Imlay JA. 2012. Silver(I), mercury(II), cadmium(II), and zinc(II) target exposed enzymic iron-sulfur clusters when they toxify Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:3614–3621. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07368-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Skaar EP. 2010. The battle for iron between bacterial pathogens and their vertebrate hosts. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000949. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cornelis P, Wei Q, Andrews SC, Vinckx T. 2011. Iron homeostasis and management of oxidative stress response in bacteria. Metallomics 3:540–549. doi: 10.1039/c1mt00022e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ong KS, Cheow YL, Lee SM. 2017. The role of reactive oxygen species in the antimicrobial activity of pyochelin. J Adv Res 8:393–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2017.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Xu Z, Li Y, Cao H, Si M, Zhang G, Woo PCY, Yan A. 2021. A transferrable and integrative type I-F Cascade for heterologous genome editing and transcription modulation. Nucleic Acids Res 49:e94. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Li H, Durbin R. 2009. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R, Genome Project Data Processing S. 2009. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lunter G, Goodson M. 2011. Stampy: a statistical algorithm for sensitive and fast mapping of Illumina sequence reads. Genome Res 21:936–939. doi: 10.1101/gr.111120.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. 2014. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30:923–930. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. 2014. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wu T, Hu E, Xu S, Chen M, Guo P, Dai Z, Feng T, Zhou L, Tang W, Zhan L, Fu X, Liu S, Bo X, Yu G. 2021. clusterProfiler 4.0: a universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation (Camb) 2:100141. doi: 10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental figures and table.

List of differentially expressed genes (P<0.05) in the ΔczcR mutant compared to the wild-type strain as measured during Zn excess.

Data Availability Statement

The transcriptome data were deposited in the NCBI under the project accession number PRJNA896733.