Summary.

Obesity affects nearly one‐third of adults in Australia and is the second leading contributor to the nation's burden of disease.

For people with obesity, weight loss of 5% or more has health benefits, and greater weight loss is associated with progressive improvements in health and health‐related quality of life.

Long term management is required to sustain the health benefits of weight loss.

In Australia, medications for obesity management are indicated in conjunction with lifestyle interventions in adults with obesity (body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2) or those who are overweight (body mass index ≥ 27 kg/m2) with at least one complication of excess weight.

Five medications are currently approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration for obesity management in Australia, and the treatment pipeline is evolving rapidly, with several new agents under development for the management of obesity and its complications.

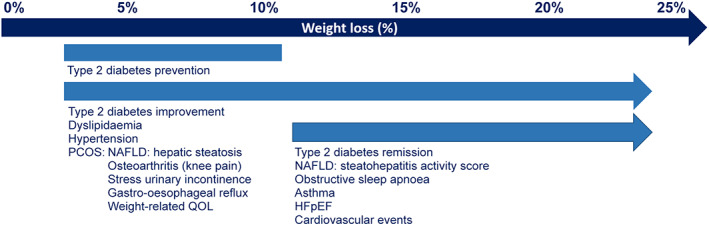

The prevalence of obesity among adults has nearly tripled worldwide since 1975 to more than 650 million in 2016, 1 including 31% of adults in Australia. 2 Obesity is the second leading contributor to Australia's burden of disease due to its complications, which include cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, chronic kidney disease, fatty liver, obstructive sleep apnoea, and several cancers. 2 Many of these complications can be prevented or mitigated with a loss of as little as 5% of total body weight (Box 1), with greater weight loss usually resulting in progressive improvements in obesity‐related complications and quality of life. 4 , 5 , 6

Box 1. Magnitude of weight loss required for improvement in obesity complications 3 .

HFpEF = heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; NAFLD = non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease; PCOS = polycystic ovary syndrome; QOL = quality of life.

Lifestyle interventions that incorporate reduction in energy intake, improved diet quality and increased physical activity are the foundation of obesity management. However, obesity is chronic and relapsing, and most people who lose weight with lifestyle interventions alone will regain weight over time. 7 Long term maintenance of weight loss is very challenging for most people because of complex interactions between biology, behaviour and the obesogenic environment. Weight loss leads to numerous long‐lasting biological changes, including a reduction in total energy expenditure greater than expected for the amount of lean mass lost, an increase in appetite, alterations in several hormones (including adipocyte, thyroid and gut hormones) involved in hunger, satiety and energy expenditure, and alterations in neural activity in several brain areas that mediate food intake. 8 , 9 Although direct links with weight regain have not been shown, many of these changes would appear to favour regain of lost weight. Lack of understanding of the biology of obesity perpetuates the misconception that it is simply due to lifestyle factors and inadequate motivation for behaviour change. This stigma is common, even in the health care sector, and can lead to reluctance by people with obesity to seek treatment, as well as compromise the quality of care provided (eg, incomplete discussion of treatment options). 10

Clinical practice guidelines for obesity management recommend consideration of very low energy diets, medications and bariatric surgery when lifestyle interventions alone have not achieved therapeutic goals. 11 , 12 Growing recognition of the pathophysiology of obesity 12 , 13 has led to considerable advances in obesity pharmacotherapies over the past decade. This narrative review provides an overview of current and emerging medications for obesity management, including recommendations and knowledge gaps regarding their use in clinical practice.

Methods

We searched the MEDLINE (Ovid) online database and the ClinicalTrials.gov registration to identify relevant studies, using the search terms “obesity”, “morbid obesity”, “overweight”, “body weight”, “weight loss”, “weight gain”, “adiposity”, “adipose”, “medication”, “pharmacotherapy” and “weight management”. We considered for inclusion human studies published in English before 22 August 2022 based on relevance, originality and impact (eg, number of citations), and screened the reference lists of relevant articles. Publications reporting outcomes of phase 3 clinical trials of obesity medications were preferentially included, along with any article otherwise known to the authors relevant to the topic and not identified through the search or reference list screen.

Medications for obesity management

In Australia, medications, in conjunction with lifestyle interventions, are indicated for weight management in adults (≥18 years of age) with obesity (body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2) or those who are overweight (body mass index ≥ 27 kg/m2, or ≥ 25 kg/m2 for phentermine) with at least one weight‐related complication. Five agents are currently approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) for obesity management: orlistat, phentermine, naltrexone–bupropion, and the glucagon‐like peptide 1 (GLP‐1) receptor agonists liraglutide and semaglutide. Their mechanisms of action, dosing, effects, and costs are summarised in Box 2. All currently approved medications, apart from orlistat, act centrally in brain regions involved in appetite regulation to increase satiety, reduce hunger, and, in some cases, reduce the rewarding properties of high calorie food. At present, the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme does not subsidise medications indicated for obesity management. In Australia, at the time of writing, semaglutide 2.4 mg weekly is indicated for chronic weight management but is not yet available.

Box 2. Medications indicated for the treatment of obesity in adults in Australia.

| Medication | Phentermine* | Orlistat † | Liraglutide 3 mg ‡ | Naltrexone–bupropion § | Semaglutide 2.4 mg ¶ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of TGA approval | 1991 | 2000 | 2015 | 2018 | 2022 |

| Route and form | Oral (capsule) | Oral (tablet) | Subcutaneous (injection) | Oral (tablet) | Subcutaneous (injection) |

| Recommended dose | 15 mg, 30 mg or 40 mg once daily | 120 mg three times a day, with meals | Starting dose 0.6 mg daily, escalating by 0.6 mg per week over five weeks to 3 mg once daily | Starting dose one 8 mg naltrexone–90 mg bupropion tablet daily, escalating by one tablet per week over four weeks to two tablets twice daily (16 mg naltrexone–180 mg bupropion twice a day) | Starting dose 0.25 mg weekly, escalating every four weeks to 2.4 mg weekly over 16 weeks |

| Mechanism of action for weight loss | Reduces appetite by stimulating neural release of noradrenaline, serotonin and dopamine | Reduces absorption of dietary fat by inhibiting gastric and pancreatic lipases | Reduces appetite by stimulating GLP‐1 receptors in several brain areas | Reduces appetite by stimulating activity of POMC neurons in the hypothalamus | Reduces appetite by stimulating GLP‐1 receptors in several brain areas |

| Contraindications and precautions | Coronary artery disease, uncontrolled hypertension, hyperthyroidism, glaucoma, cardiac arrhythmias, MAOI, pregnancy, breastfeeding | Pregnancy, breastfeeding | Personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma or multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2, history of pancreatitis, pregnancy, breastfeeding | Uncontrolled hypertension, seizure disorders, bipolar disorder, undergoing abrupt discontinuation of alcohol or anticonvulsant drugs, chronic opioid use, MAOI, pregnancy, breastfeeding | As for liraglutide |

| Not recommended with SSRIs | |||||

| Adverse effects | Dry mouth, insomnia, palpitations, tachycardia, hypertension, anxiety, dizziness, constipation | Steatorrhea, oily spotting, faecal urgency | Nausea, diarrhoea, constipation, vomiting, headache, dyspepsia, cholelithiasis | Nausea, constipation, headache, vomiting, dizziness, insomnia, dry mouth, diarrhoea, hypertension | As for liraglutide |

| Mean placebo‐subtracted weight loss | 7.4 kg over 36 weeks 14 | 4% at 52 weeks 15 | 4–6% at 56 weeks 16 | 5% at 56 weeks 17 | 12–14% at 68 weeks 18 , 19 |

| Proportion of clinical trial participants with 5% and 10% weight loss at ~12 months | NA | 73% and 41% (v 45% and 21% placebo) 20 | 63% and 33% (v 27% and 11% placebo) 16 | 48% and 25% (v 16% and 7% placebo) 17 | 86% and 69% (v 32% and 12% placebo) 18 |

| Effects on reward‐related drivers of eating | Reduced craving for fats and sweets v placebo (Food Craving Inventory) at 12 weeks 21 | No difference in changes to eating restraint, disinhibition, or binge eating v placebo after 18–33 months (Three Factor Eating Questionnaire, Binge Eating Scale) 22 | Reduced desire to consume sweet, salty, fatty and savoury foods v placebo (visual analogue scales) at 16 weeks 23 | Reduced desire to consume sweet and starchy foods, reduced incidence and strength of food cravings, reduced eating in response to food cravings, increased ability to resist food cravings and control eating during 56 weeks (Control of Eating Questionnaire). No difference v placebo on Food Craving Inventory 24 | Improved control of eating, reduced incidence and strength of food cravings v placebo (Control of Eating Questionnaire) following 20 weeks of treatment 26 |

| Altered activation v placebo in several brain areas in response to palatable food cues on functional MRI after four weeks of treatment 25 | |||||

| Effect on health‐related quality of life | NA | No difference in quality of life compared with lifestyle intervention plus placebo 27 | Greater improvement in all domains (IWQOL‐Lite) v placebo at 12 months 16 | Greater improvement in all domains (IWQOL‐Lite) v placebo at 12 months from week 8 of treatment 17 | Greater improvement in physical function (IWQOL‐Lite) v placebo and greater increase in mental component summary v placebo (SF‐36) 18 |

| Approximate cost in 2023 per month at maximum dose | $145 | $93 | $387 | $240 | NA |

| Other considerations | It is recommended that phentermine be used with caution, and with monitoring of blood pressure, in people with hypertension | Reduction in risk of developing type 2 diabetes by 37% v placebo in people at high risk at four years 20 | Reduction in risk of developing type 2 diabetes by 66% v placebo in people at high risk over three years 28 | No improvement in blood pressure with weight loss | |

| Caution and reduced dosing in patients treated with antidepressants and some antipsychotics |

GLP‐1 = glucagon‐like peptide 1; IWQoL‐Lite = Impact of Weight on Quality of Life‐Lite; MAOI = monoamine oxidase inhibitors; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; NA = data not available; POMC = pro‐opiomelanocortin; SF‐36 = 36‐Item Short Form Health Survey; SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Several brands of phentermine, including Duromine, Metermine (iNova), and Phentermine Juno (Juno).

Xenical (Pharmaco), Prolistat (Advanz Pharma).

Saxenda (Novo Nordisk).

Contrave (iNova).

Wegovy (Novo Nordisk).

Orlistat

Orlistat reduces the absorption of dietary fats by preventing their digestion through the inactivation of gastric and pancreatic lipases, leading to an increase in excretion of up to 35% of ingested fat in the faeces. 29 In clinical trials with at least 12 months’ follow‐up, the use of orlistat leads to weight loss of around 4–10 kg over 12 months (~3% in excess of placebo). 7 , 30

Gastrointestinal adverse effects such as steatorrhea (30% in clinical trials 15 ), faecal urgency and oily leakage 31 are common and related to the fat content of the meal. It is recommended that people taking orlistat also take a multivitamin supplement due to reduced absorption of fat‐soluble vitamins, 32 although clinically significant vitamin deficiency is rarely reported. 30 There are also reports of acute kidney injury in association with orlistat use due to hyperoxaluria and oxalate nephropathy. 33 In Australia, orlistat is available from pharmacies without a prescription.

Phentermine

Phentermine is a sympathomimetic agent. Studies in rats show that it stimulates the release of noradrenaline, dopamine and serotonin in several areas of the brain, including the hypothalamus. 34 , 35 Phentermine reduces hunger and reward‐related eating. 21 It has been in use for more than 60 years (approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration [FDA] in 1959), and is the subject of few randomised controlled trials. Phentermine is indicated as a short term adjunct in the management of overweight and obesity (duration unspecified, often interpreted as < 12 weeks). A clinical trial of phentermine 30 mg daily reported weight loss of 12.2 kg (v 4.8 kg with placebo) in participants who completed 36 weeks of treatment. 14

Common adverse effects of phentermine include insomnia, dry mouth, and increased blood pressure and heart rate. Cardiac valvular regurgitation was reported in people who took phentermine in combination with fenfluramine or dexfenfluramine (no longer available) for weight loss. Even though there are no reported cases to date of valvular heart disease associated with phentermine monotherapy, the combination of phentermine with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors is not recommended due to the theoretical risk of cardiac valvular disease. 36

Naltrexone–bupropion

The combination of the antidepressant bupropion and the opioid antagonist naltrexone was developed for obesity management based on the synergistic effects of these agents in central appetite and reward regions. Bupropion is a dopamine and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor that stimulates the activity of anorexigenic pro‐opiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons in the hypothalamus. 24 Naltrexone blocks endogenous opioid‐mediated inhibition of POMC neurons, leading to sustained POMC stimulation. 24 Clinical trials report weight loss of 5–6 kg (3–5% above placebo) over one year. 17 , 37 , 38

The adverse effects most commonly reported in clinical trials of naltrexone–bupropion are nausea (30%) and constipation (16%), particularly during dose escalation. 37 Increased blood pressure and heart rate are also potential adverse effects. The label contains a warning about an increased risk of depression and suicidal behaviour based on these effects with bupropion monotherapy, although clinical trials have not reported increased depression or suicidality with the naltrexone–bupropion combination compared with placebo. 17 , 37 , 38

Clinicians should be aware of several potential drug interactions when prescribing naltrexone–bupropion. Concomitant treatment with certain cytochrome P450 2B6 (CYP2B6) inhibiting agents (eg, clopidogrel) can increase bupropion exposure. Conversely, CYP2B6 inducers (including human immunodeficiency virus antivirals and some anticonvulsant medications, such as carbamazepine and phenytoin) may reduce efficacy by increasing bupropion metabolism. Bupropion inhibits cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6) thereby reducing metabolism of some antidepressant (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclics), antipsychotic (eg, haloperidol, risperidone) and cardiac medications (eg, metoprolol, flecainide). Extreme caution is advised when combining naltrexone–bupropion with drugs that lower the seizure threshold (including some antipsychotic and antidepressant agents). In addition, central nervous system toxicity has been reported with concomitant use of bupropion with dopaminergic drugs such as levodopa. 39

Glucagon‐like peptide 1 receptor agonists

GLP‐1 is a hormone secreted by L cells in the distal small intestine and colon in response to ingestion of nutrients. Its numerous metabolic actions are mediated via GLP‐1 receptors, which are widely distributed, including in the brain, pancreas, stomach, kidney, heart, and adipose tissue. 40 GLP‐1 receptor agonists reduce food intake by acting at GLP‐1 receptors in appetite‐ and reward‐related regions of the brain, including the hypothalamus, hindbrain and mesolimbic pathway, to promote satiation and reduce hunger and food reward. 40 Additional effects of GLP‐1 include stimulation of insulin secretion under conditions of hyperglycaemia, reduction in glucagon secretion, and slowing of gastric emptying. 41 , 42

Endogenous GLP‐1 has a short half‐life of one to two minutes, as it is rapidly inactivated by the enzyme dipeptidylpeptidase‐4 (DPP‐4) and cleared from the circulation by the kidneys. GLP‐1 receptor agonists have been developed to promote the favourable metabolic effects of native GLP‐1 with longer duration of action and greater bioavailability.

Several GLP‐1 receptor agonists are available in Australia for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, of which two, liraglutide and semaglutide, are also indicated for obesity treatment at higher doses (liraglutide 3.0 mg daily and semaglutide 2.4 mg weekly for obesity, and up to 1.8 mg daily and 1.0 mg weekly, respectively, for type 2 diabetes). When used at recommended doses for obesity management in people without type 2 diabetes, mean weight losses in clinical trials are 6–8 kg (~6% placebo‐subtracted) for liraglutide 16 and 15–18 kg (~13% placebo‐subtracted) with semaglutide. 18 , 19

The adverse effects of GLP‐1 receptor agonists are predominantly gastrointestinal. Nausea (40%) and diarrhoea (21%) are the most common adverse effects for liraglutide 3.0 mg, 16 with a similar adverse event profile for semaglutide 2.4 mg. 43 A gradual dose escalation is recommended to minimise these effects. Nausea is usually transient and mild and is most common shortly after treatment initiation and during dose escalation. 16 , 18

In people with type 2 diabetes, the 1 mg dose of semaglutide for type 2 diabetes treatment was associated with a higher risk of complications of diabetic retinopathy in patients with a history of retinopathy at the time of treatment initiation. 44 This might be related to rapid improvement in glycaemic control, which is known to be associated with transient worsening of diabetic retinopathy. 45 Hence, retinopathy‐related risks are likely to be much lower in people without diabetes. The effect of semaglutide (up to 1 mg weekly) on the development and progression of diabetic retinopathy over five years will be examined in a dedicated trial (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03811561). Some epidemiological studies have suggested an increased risk of acute pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer in people using GLP‐1 receptor agonists. However, a meta‐analysis of more than 55 000 participants from cardiovascular outcome trials in people with type 2 diabetes using GLP‐1 receptor agonists (including semaglutide and liraglutide) at doses used to treat type 2 diabetes did not detect a signal for these events over 175 000 patient‐years of observation. 46

Topiramate

Topiramate is a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor indicated for the treatment of epilepsy and as prophylaxis against migraines. When used in the treatment of epilepsy, anorexia and weight loss are common adverse effects. The mechanism by which topiramate decreases appetite is not known.

In Australia, topiramate is not approved by the TGA for an obesity indication, but it is inexpensive and commonly used “off‐label” for obesity management, either as monotherapy or in combination with medications, particularly phentermine. 47 The combination of phentermine with an extended‐release formulation of topiramate is approved for chronic weight management in the United States but not in Australia. Of note, the recommended dose of this combination contains 7.5 mg phentermine and 46 mg of topiramate (half of the minimum available capsule size of phentermine in Australia), with a maximum dose of 15 mg phentermine plus 92 mg topiramate.

Gradual dose escalation of topiramate is recommended to improve tolerability, starting with 12.5 mg once a day and increasing to a maximum of 50 mg twice a day. Common adverse effects include paraesthesia, dysgeusia (taste distortion), somnolence, memory, attention and concentration difficulties, and mood disturbances. 48 Rare adverse effects include kidney stones and angle closure glaucoma. Topiramate is contraindicated in pregnancy due to an association with congenital malformations. A meta‐analysis of randomised trials examining the effect of topiramate use for 16 weeks or more on weight loss reported a mean placebo‐subtracted weight loss of 5.3 kg. 48

Variability in weight loss responses

Medications indicated for obesity management are consistently associated with lower weight losses in people with type 2 diabetes than in those without diabetes. 16 , 18 , 49 , 50 The reasons for this are not known but might include concomitant use of glucose‐lowering agents that promote weight gain, increased food intake to prevent or treat hypoglycaemia, and reduction in glycosuria (due to glycaemic improvement) offsetting weight loss. 51

Although mean weight loss with current obesity medications (with the exception of semaglutide) is in the range of 3–6% in excess of placebo, it is important to note that individual responses vary widely for all agents, with 25–69% of participants achieving at least 10% weight loss over one year of treatment.

Health improvements associated with obesity medications

All obesity medications are associated with improvements in cardiovascular risk factors, although these benefits differ between medications even if similar mean weight loss is achieved. For example, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol lowering is greater with orlistat than other agents, which is likely due to its effect on reducing fat absorption. 20 , 52 , 53 Weight loss induced by naltrexone–bupropion is not associated with the expected improvement in blood pressure. 24 , 37 , 38 As anticipated from their pancreatic actions, GLP‐1 receptor agonists are associated with greater glycaemic improvements than other agents after a similar amount of weight loss. 17 , 50 Orlistat 54 and GLP‐1 receptor agonists 55 , 56 appear to reduce liver fat content and markers of liver injury in people with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease, but whether this effect is independent of weight loss remains unclear. 54 , 57 There is a lack of data on the effects of other obesity medications on non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease. 54

As yet, there are no completed cardiovascular outcome trials of medications currently indicated for obesity management. Such trials have not been conducted for phentermine and orlistat, and a cardiovascular outcome trial of naltrexone–bupropion was terminated prematurely due to a breach of confidentiality regarding interim analyses. 58 In people with type 2 diabetes, who have a higher cardiovascular risk than the general population, liraglutide and semaglutide have demonstrated reductions in major adverse cardiovascular outcomes compared with placebo (at doses used for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: liraglutide 1.8 mg daily; semaglutide 0.5 mg and 1.0 mg weekly). 44 , 59 In people without type 2 diabetes, an analysis of pooled data from five trials found that liraglutide 3.0 mg did not reduce cardiovascular events compared with placebo (n = 5064; hazard ratio, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.16–1.44). 60 A cardiovascular outcome trial of semaglutide 2.4 mg weekly in 17 500 people is underway in people with obesity (but without type 2 diabetes) who have established cardiovascular disease. 61

Most approved obesity medications have been shown to improve health‐related or weight‐related quality of life. Orlistat might not improve quality of life compared with placebo, 27 and quality of life outcomes have not been reported for phentermine. All obesity medications except orlistat are associated with improvements in eating behaviour compared with placebo (Box 2). 21 , 22 , 23 , 25 , 26

Novel and emerging medications for obesity

Tirzepatide

Tirzepatide is a dual agonist of receptors for both GLP‐1 and glucose‐dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP). Following nutrient ingestion, these two gut hormones stimulate insulin secretion via GLP‐1 and GIP receptors on pancreatic β‐cells, thereby minimising postprandial blood glucose elevation. Receptors for both hormones are also found in regions of the brain that regulate food intake, although studies are mixed in their findings on the contribution of GIP receptor activation to food intake and body weight. 62 Tirzepatide potently reduces body weight as well as blood glucose. It is approved by the FDA and the TGA for the treatment of type 2 diabetes at a once‐weekly subcutaneous dose of 5 mg, 10 mg and 15 mg and is undergoing clinical trials for the management of obesity at the same doses, as well as other conditions, such as heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis.

Results from a phase 3 clinical trial for obesity (n = 2539) showed that tirzepatide 5 mg, 10 mg and 15 mg resulted in mean placebo‐subtracted weight loss over 72 weeks of 11.9%, 16.4% and 17.8% respectively (total weight loss of 15–20 kg). 63 More than half of participants in the 10 mg and 15 mg groups lost 20% or more of body weight, and improvements were observed in blood pressure, lipid profile, glycaemia and physical function. The adverse effect profile appears similar to GLP‐1 receptor agonists, with predominantly gastrointestinal effects noted. 63 At the time of writing, tirzepatide is indicated for type 2 diabetes but is not yet available in Australia.

Cagrilintide

Amylin is a hormone co‐secreted with insulin from pancreatic β‐cells in response to nutrient ingestion. It slows the absorption of glucose into the circulation by delaying gastric emptying and acts at receptors in the hindbrain and mesolimbic dopamine system to increase satiation and reduce the rewarding value of food. 64

Cagrilintide is a long‐acting amylin analogue in development for the management of obesity as a once weekly subcutaneous injection. Results from a phase 2 study indicate weight loss of up to 11 kg (8% greater than placebo and almost 2% greater than liraglutide 3.0 mg daily) over 26 weeks. 65 A combination of cagrilintide and semaglutide is also being investigated for obesity management. 66

Setmelanotide

Setmelanotide is a melanocortin 4 receptor agonist developed for the treatment of rare monogenic obesity syndromes caused by defects in the hypothalamic leptin–melanocortin pathway. These disorders are characterised by severe hyperphagia and early‐onset obesity. 67 Setmelanotide is approved for use in the US and Europe, but not currently Australia, for patients aged six years or older with POMC, proprotein convertase 1 or leptin receptor deficiency. Setmelanotide is also undergoing trials for use in other genetic disorders associated with obesity, such as Bardet–Biedl syndrome. 68 Injection site reactions and skin pigmentation are the most common adverse effects noted in clinical trials.

Bimagrumab

Bimagrumab is a human monoclonal antibody that binds to the activin type II receptor (ActRII). ActRII blockade prevents the binding of natural ligands that negatively regulate skeletal muscle growth and, in animal models, promotes brown adipose tissue differentiation and activity. 69 , 70 In a small 48‐week phase 2 trial in adults with type 2 diabetes and obesity, bimagrumab (10 mg/kg up to 1200 mg, intravenous infusion every four weeks) resulted in loss of fat mass of 20.5% compared with 0.5% in the placebo group (7.5 kg v 0.2 kg respectively), and a gain in lean mass of 3.6% compared with loss of 0.8% in the placebo group (+1.7 kg v ‐0.4 kg respectively) as well as improved glycaemic control. 71 The increase in lean mass is notable, as negative energy balance and weight loss are typically associated with lean mass reduction. The mechanism for fat mass reduction is unknown. Diarrhoea and muscle spasms were the most common adverse effects.

Other gut hormone‐based agents

Several other medications with dual and triple action at gut hormone receptors (eg, GLP‐1, GIP, glucagon, amylin) are under development. 72 , 73 These agents aim to exploit the complementary actions of these hormones on appetite and glycaemia and mimic the endogenous release of several gut hormones postprandially.

Considerations for use of obesity medications in clinical practice

Concurrent lifestyle intervention

The main purpose of obesity treatment is to improve health and wellbeing. All medications are indicated in conjunction with lifestyle interventions, as optimising diet quality, reducing energy intake and increasing energy expenditure have their own health benefits, as well as improving the effectiveness of treatment with obesity medications. 74 , 75 As an example, the use of liraglutide in combination with physical activity over 12 months resulted in an additional mean weight loss of 2.7 kg and reduction in body fat of 1.7% compared with liraglutide alone. 75

Timing and duration of treatment

Use of medications should be considered at the initiation of an obesity management program, particularly if there have been previous unsuccessful attempts at lifestyle interventions alone. Where the primary treatment modality is lifestyle interventions or bariatric surgery, the addition of medications might be useful if therapeutic goals have not been reached, or to prevent or reduce weight regain. 76

When obesity medications are initiated, and while they are in use, blood pressure should be monitored and doses of antihypertensive agents adjusted as required. In people with type 2 diabetes, glucose‐lowering medications might need to be reduced to avoid hypoglycaemia, particularly if a GLP‐1 receptor agonist is added.

Current TGA recommendations state that obesity medications should be discontinued if loss of at least 5% of total body weight has not occurred after 12 weeks of use at the maximal dose. Since early response to treatment is associated with long term weight outcomes, this recommendation is aimed at preventing prolonged use of an ineffective treatment for weight reduction. However, it does not take into account the benefit of preventing recurrence of obesity‐related complications if a medication is initiated for prevention or mitigation of weight regain.

As is the case for medications used to treat most chronic diseases, medications for obesity are only effective while in use. 43 , 77 Therefore, long term use is likely to be required for sustained benefits to health and health‐related quality of life, although data on long term safety and clinical outcomes for obesity medications are currently limited. 78 , 79 Adherence to treatment is a challenge. One‐year treatment discontinuation rates in clinical trials are 17–50% for medications currently approved for long term weight management, 15 , 16 , 18 , 37 but persistence with treatment is much lower (< 10%) in real‐world studies. 79

Choice of agent

To date, few studies have directly compared outcomes of different obesity medications. Randomised trials have shown greater mean weight loss with liraglutide 3 mg daily compared with orlistat 120 mg three times a day (mean difference, 3.7 kg at one year) 80 and with semaglutide 2.4 mg weekly compared with liraglutide 3.0 mg daily (mean difference, 8.5 kg at week 68). 19

There is a suggestion that patients with certain biological and behavioural characteristics might respond better to particular medications, 81 but data are currently insufficient to guide clinical practice. Choice of agent is currently based largely on the expected benefits and adverse effect profiles of each agent in relation to the individual patient as well as patient preferences (including for mode of administration), medication availability and cost.

As with other chronic diseases, the use of more than one agent with complementary mechanisms of action might be more effective, and associated with fewer side effects, than monotherapy. This approach has not been studied in clinical trials combining the currently available agents but is being explored for new medications in development. 66

Access to treatment

Only a minority of eligible people (estimated at 1.3% in a cohort of > 2 million US adults) are treated with obesity medications. 82 There are a number of likely contributing factors, including out‐of‐pocket costs, lack of recognition of the role of medications in the management of obesity, a perception that mean weight losses associated with most agents are insufficient to justify their use, a lack of long term clinical trial data, and safety concerns following the withdrawal from the market of several older classes of medications. 82 Stigma associated with obesity and its treatment is another potential contributor, as many of these concerns are less often raised for medications, even new agents, for the treatment of other chronic diseases. 83

Conclusion

Five medications are currently indicated for obesity management in Australia, all of which have beneficial effects on obesity‐related complications. The newest agents, and those in clinical development, are associated with considerably greater mean efficacy than older agents, but interindividual variability in response to all agents is substantial. When medications are used, important considerations include treatment goals, patient preferences, weight‐loss‐independent benefits of individual agents, contraindications, side effect profiles, method of administration, and costs. The effective management of obesity requires a long term approach.

Open access

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Melbourne, as part of the Wiley ‐ The University of Melbourne agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Competing interests

Priya Sumithran has co‐authored manuscripts which have had medical writing assistance provided (Novo Nordisk). No medical writing assistance was received for this manuscript. Priya Sumithran is in the leadership group of the Obesity Collective.

Provenance

Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Acknowledgements

Priya Sumithran is supported by an Investigator Grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council (1178482).

References

- 1. World Health Organization . Obesity and overweight [website]. WHO, 2021. https://www.who.int/news‐room/fact‐sheets/detail/obesity‐and‐overweight (viewed Aug 2022).

- 2. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Overweight and obesity [website]. Canberra: AIHW, 2022. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias‐health/overweight‐and‐obesity (viewed Aug 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ryan DH, Yockey SR. Weight loss and improvement in comorbidity: differences at 5%, 10%, 15%, and over. Curr Obes Rep 2017; 6: 187‐194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wing RR, Lang W, Wadden TA, et al; Look AHEAD Research Group. Benefits of modest weight loss in improving cardiovascular risk factors in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011; 34: 1481‐1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD, Williams GR, et al. The relationship between health‐related quality of life and weight loss. Obes Res 2001; 9: 564‐571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Knowler WC, Barrett‐Connor E, Fowler SE, et al; Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 393‐403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Franz MJ, VanWormer JJ, Crain AL, et al. Weight‐loss outcomes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of weight‐loss clinical trials with a minimum 1‐year follow‐up. J Am Diet Assoc 2007; 107: 1755‐1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Aronne LJ, Hall KD, Jakicic JM, et al. Describing the weight‐reduced state: physiology, behavior, and interventions. Obesity 2021; 29 (Suppl): S9‐S24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hall KD, Kahan S. Maintenance of lost weight and long‐term management of obesity. Med Clin North Am 2018; 102: 183‐197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Phelan SM, Burgess DJ, Yeazel MW, et al. Impact of weight bias and stigma on quality of care and outcomes for patients with obesity. Obes Rev 2015; 16: 319‐326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Markovic TP, Proietto J, Dixon JB, et al. The Australian Obesity Management Algorithm: a simple tool to guide the management of obesity in primary care. Obes Res Clin Pract 2022; 16: 353‐363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yumuk V, Tsigos C, Fried M, et al. European guidelines for obesity management in adults. Obes Facts 2015; 8: 402‐424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bray GA, Kim KK, Wilding JPH; World Obesity Federation . Obesity: a chronic relapsing progressive disease process. A position statement of the World Obesity Federation. Obes Rev 2017; 18: 715‐723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Munro JF, MacCuish AC, Wilson EM, Duncan LJ. Comparison of continuous and intermittent anorectic therapy in obesity. Br Med J 1968; 1: 352‐354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sjöström L, Rissanen A, Andersen T, et al; European Multicentre Orlistat Study Group. Randomised placebo‐controlled trial of orlistat for weight loss and prevention of weight regain in obese patients. Lancet 1998; 352: 167‐172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pi‐Sunyer X, Astrup A, Fujioka K, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of 3.0 mg of liraglutide in weight management. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 11‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hollander P, Gupta AK, Plodkowski R, et al; COR‐Diabetes Study Group. Effects of naltrexone sustained‐release/bupropion sustained‐release combination therapy on body weight and glycemic parameters in overweight and obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2013; 36: 4022‐4029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Calanna S, et al. Once‐weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. N Eng J Med 2021; 384: 989‐1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rubino DM, Greenway FL, Khalid U, et al. Effect of weekly subcutaneous semaglutide vs daily liraglutide on body weight in adults with overweight or obesity without diabetes: the STEP 8 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2022; 327: 138‐150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Torgerson JS, Hauptman J, Boldrin MN, Sjöström L. XENical in the prevention of diabetes in obese subjects (XENDOS) study: a randomized study of orlistat as an adjunct to lifestyle changes for the prevention of type 2 diabetes in obese patients. Diabetes Care 2004; 27: 155‐161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moldovan CP, Weldon AJ, Daher NS, et al. Effects of a meal replacement system alone or in combination with phentermine on weight loss and food cravings. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2016; 24: 2344‐2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Svendsen M, Rissanen A, Richelsen B, et al. Effect of orlistat on eating behavior among participants in a 3‐year weight maintenance trial. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008; 16: 327‐333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kadouh H, Chedid V, Halawi H, et al. GLP‐1 analog modulates appetite, taste preference, gut hormones, and regional body fat stores in adults with obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020; 105: 1552‐1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Billes SK, Sinnayah P, Cowley MA. Naltrexone/bupropion for obesity: an investigational combination pharmacotherapy for weight loss. Pharmacol Res 2014; 84: 1‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang GJ, Tomasi D, Volkow ND, et al. Effect of combined naltrexone and bupropion therapy on the brain's reactivity to food cues. Int J Obes (Lond) 2014; 38: 682‐688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Friedrichsen M, Breitschaft A, Tadayon S, et al. The effect of semaglutide 2.4 mg once weekly on energy intake, appetite, control of eating, and gastric emptying in adults with obesity. Diabetes Obes Metab 2021; 23: 754‐762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shi Q, Wang Y, Hao Q, et al. Pharmacotherapy for adults with overweight and obesity: a systematic review and network meta‐analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet 2022; 399: 259‐269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. le Roux CW, Astrup A, Fujioka K, et al. 3 years of liraglutide versus placebo for type 2 diabetes risk reduction and weight management in individuals with prediabetes: a randomised, double‐blind trial. Lancet 2017; 389: 1399‐409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhi J, Melia AT, Guerciolini R, et al. Retrospective population‐based analysis of the dose‐response (fecal fat excretion) relationship of orlistat in normal and obese volunteers. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1994; 56: 82‐85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Padwal R, Li SK, Lau DC. Long‐term pharmacotherapy for obesity and overweight. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004; (3): CD004094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Filippatos TD, Derdemezis CS, Gazi IF, et al. Orlistat‐associated adverse effects and drug interactions: a critical review. Drug Saf 2008; 31: 53‐65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Xenical [package insert]. San Francisco (CA): Genentech, 2012. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/020766s029lbl.pdf (viewed Oct 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 33. Solomon LR, Nixon AC, Ogden L, Nair B. Orlistat‐induced oxalate nephropathy: an under‐recognised cause of chronic kidney disease. BMJ Case Rep 2017; 2017: bcr‐2016‐218623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Balcioglu A, Wurtman RJ. Effects of phentermine on striatal dopamine and serotonin release in conscious rats: In vivo microdialysis study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1998; 22: 325‐328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rothman RB, Baumann MH, Dersch CM, et al. Amphetamine‐type central nervous system stimulants release norepinephrine more potently than they release dopamine and serotonin. Synapse 2001; 39: 32‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Metermine [Australian product information] Sydney: iNova Pharmaceuticals, 2022. https://www.ebs.tga.gov.au/ebs/picmi/picmirepository.nsf/pdf?OpenAgent=&id=CP‐2010‐PI‐06558‐3&d=20221103172310101 (viewed Oct 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 37. Greenway FL, Fujioka K, Plodkowski RA, et al. Effect of naltrexone plus bupropion on weight loss in overweight and obese adults (COR‐I): a multicentre, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2010; 376: 595‐605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Apovian CM, Aronne L, Rubino D, et al; COR‐II Study Group. A randomized, phase 3 trial of naltrexone SR/bupropion SR on weight and obesity‐related risk factors (COR‐II). Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013; 21: 935‐943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Contrave [package insert]. La Jolla (CA): Orexigen Therapeutics, 2014. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/200063s000lbl.pdf (viewed Oct 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 40. Müller TD, Finan B, Bloom SR, et al. Glucagon‐like peptide 1 (GLP‐1). Mol Metab 2019; 30: 72‐130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Drucker DJ. Mechanisms of action and therapeutic application of glucagon‐like peptide‐1. Cell Metab 2018; 27: 740‐756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Secher A, Jelsing J, Baquero AF, et al. The arcuate nucleus mediates GLP‐1 receptor agonist liraglutide‐dependent weight loss. J Clin Invest 2014; 124: 4473‐4488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rubino D, Abrahamsson N, Davies M, et al. Effect of continued weekly subcutaneous semaglutide vs placebo on weight loss maintenance in adults with overweight or obesity: the STEP 4 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2021; 325: 1414‐1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, et al. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 1834‐1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group . Early worsening of diabetic retinopathy in the diabetes control and complications trial. Arch Ophthalmol 1998; 116: 874‐886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Abd El Aziz M, Cahyadi O, Meier JJ, et al. Incretin‐based glucose‐lowering medications and the risk of acute pancreatitis and malignancies: a meta‐analysis based on cardiovascular outcomes trials. Diabetes Obes Metab 2020; 22: 699‐704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gadde KM, Allison DB, Ryan DH, et al. Effects of low‐dose, controlled‐release, phentermine plus topiramate combination on weight and associated comorbidities in overweight and obese adults (CONQUER): a randomised, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2011; 377: 1341‐1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kramer CK, Leitão CB, Pinto LC, et al. Efficacy and safety of topiramate on weight loss: a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev 2011; 12: e338‐e347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Davies M, Færch L, Jeppesen OK, et al. Semaglutide 2.4 mg once a week in adults with overweight or obesity, and type 2 diabetes (STEP 2): a randomised, double‐blind, double‐dummy, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2021; 397: 971‐984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Davies MJ, Bergenstal R, Bode B, et al. Efficacy of liraglutide for weight loss among patients with type 2 diabetes: the SCALE diabetes randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015; 314: 687‐699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wilding JPH. Medication use for the treatment of diabetes in obese individuals. Diabetologia 2018; 61: 265‐272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Singh AK, Singh R. Pharmacotherapy in obesity: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials of anti‐obesity drugs. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 2020; 13: 53‐64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Muls E, Kolanowski J, Scheen A, Van Gaal L; ObelHyx Study Group . The effects of orlistat on weight and on serum lipids in obese patients with hypercholesterolemia: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, multicentre study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2001; 25: 1713‐1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pan CS, Stanley TL. Effect of weight loss medications on hepatic steatosis and steatohepatitis: a systematic review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2020; 11: 70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Armstrong MJ, Gaunt P, Aithal GP, et al. Liraglutide safety and efficacy in patients with non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis (LEAN): a multicentre, double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled phase 2 study. Lancet 2016; 387: 679‐690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Newsome PN, Buchholtz K, Cusi K, et al. A placebo‐controlled trial of subcutaneous semaglutide in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med 2020; 384: 1113‐1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Khoo J, Hsiang J, Taneja R, et al. Comparative effects of liraglutide 3 mg vs structured lifestyle modification on body weight, liver fat and liver function in obese patients with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease: a pilot randomized trial. Diabetes Obes Metab 2017; 19: 1814‐1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nissen SE, Wolski KE, Prcela L, et al. Effect of naltrexone‐bupropion on major adverse cardiovascular events in overweight and obese patients with cardiovascular risk factors: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016; 315: 990‐1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown‐Frandsen K, et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 311‐322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Davies MJ, Aronne LJ, Caterson ID, et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in adults with overweight or obesity: A post hoc analysis from SCALE randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Obes Metab 2018; 20: 734‐739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ryan DH, Lingvay I, Colhoun HM, et al. Semaglutide Effects on Cardiovascular Outcomes in People With Overweight or Obesity (SELECT) rationale and design. Am Heart J 2020; 229: 61‐69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Nauck MA, D'Alessio DA. Tirzepatide, a dual GIP/GLP‐1 receptor co‐agonist for the treatment of type 2 diabetes with unmatched effectiveness regrading glycaemic control and body weight reduction. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2022; 21: 169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Jastreboff AM, Aronne LJ, Ahmad NN, et al. Tirzepatide once weekly for the treatment of obesity. N Engl J Med 2022; 387: 205‐216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Boyle CN, Lutz TA, Le Foll C. Amylin — its role in the homeostatic and hedonic control of eating and recent developments of amylin analogs to treat obesity. Mol Metab 2018; 8: 203‐210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lau DCW, Erichsen L, Francisco AM, et al. Once‐weekly cagrilintide for weight management in people with overweight and obesity: a multicentre, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled and active‐controlled, dose‐finding phase 2 trial. Lancet 2021; 398: 2160‐2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Enebo LB, Berthelsen KK, Kankam M, et al. Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of concomitant administration of multiple doses of cagrilintide with semaglutide 2.4 mg for weight management: a randomised, controlled, phase 1b trial. Lancet 2021; 397: 1736‐1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Yeo GSH, Chao DHM, Siegert AM, et al. The melanocortin pathway and energy homeostasis: from discovery to obesity therapy. Mol Metab 2021; 48: 101206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Haws RM, Gordon G, Han JC, et al. The efficacy and safety of setmelanotide in individuals with Bardet–Biedl syndrome or Alström syndrome: phase 3 trial design. Contemp Clin Trials Commun 2021; 22: 100780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Fournier B, Murray B, Gutzwiller S, et al. Blockade of the activin receptor IIB activates functional brown adipogenesis and thermogenesis by inducing mitochondrial oxidative metabolism. Mol Cell Biol 2012; 32: 2871‐2879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Rooks DS, Laurent D, Praestgaard J, et al. Effect of bimagrumab on thigh muscle volume and composition in men with casting‐induced atrophy. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2017; 8: 727‐734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Heymsfield SB, Coleman LA, Miller R, et al. Effect of bimagrumab vs placebo on body fat mass among adults with type 2 diabetes and obesity: a phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open 2021; 4: e2033457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Nahra R, Wang T, Gadde KM, et al. Effects of cotadutide on metabolic and hepatic parameters in adults with overweight or obesity and type 2 diabetes: a 54‐week randomized phase 2b study. Diabetes Care 2021; 44: 1433‐1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kakouri A, Kanti G, Kapantais E, et al. New incretin combination treatments under investigation in obesity and metabolism: a systematic review. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2021; 14: 869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Wadden TA, Berkowitz RI, Womble LG, et al. Randomized trial of lifestyle modification and pharmacotherapy for obesity. N Engl J Med 2005; 353: 2111‐2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Lundgren JR, Janus C, Jensen SBK, et al. Healthy weight loss maintenance with exercise, liraglutide, or both combined. N Engl J Med 2021; 384: 1719‐1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Stanford FC, Alfaris N, Gomez G, et al. The utility of weight loss medications after bariatric surgery for weight regain or inadequate weight loss: a multi‐center study. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2017; 13: 491‐500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Smith SR, Weissman NJ, Anderson CM, et al. Multicenter, placebo‐controlled trial of lorcaserin for weight management. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 245‐256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Gorgojo‐Martínez JJ, Basagoiti‐Carreño B, Sanz‐Velasco A, et al. Effectiveness and tolerability of orlistat and liraglutide in patients with obesity in a real‐world setting: the XENSOR study. Int J Clin Pract 2019; 73: e13399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Padwal R, Kezouh A, Levine M, Etminan M. Long‐term persistence with orlistat and sibutramine in a population‐based cohort. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007; 31: 1567‐1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Astrup A, Carraro R, Finer N, et al. Safety, tolerability and sustained weight loss over 2 years with the once‐daily human GLP‐1 analog, liraglutide. Int J Obes (Lond) 2012; 36: 843‐854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Acosta A, Camilleri M, Abu Dayyeh B, et al. Selection of antiobesity medications based on phenotypes enhances weight loss: a pragmatic trial in an obesity clinic. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2021; 29: 662‐671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Saxon DR, Iwamoto SJ, Mettenbrink CJ, et al. Antiobesity medication use in 2.2 million adults across eight large health care organizations: 2009–2015. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2019; 27: 1975‐1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Thomas CE, Mauer EA, Shukla AP, et al. Low adoption of weight loss medications: A comparison of prescribing patterns of antiobesity pharmacotherapies and SGLT2s. Obesity 2016; 24: 1955‐1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]