Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of finerenone, a selective, non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, on cardiovascular and kidney outcomes by age and/or sex.

Design

FIDELITY post hoc analysis; median follow-up of 3 years.

Setting

FIDELITY: a prespecified analysis of the FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD trials.

Participants

Adults with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease receiving optimised renin–angiotensin system inhibitors (N=13 026).

Interventions

Randomised 1:1; finerenone or placebo.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Cardiovascular (cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke or hospitalisation for heart failure (HHF)) and kidney (kidney failure, sustained ≥57% estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) decline or renal death) composite outcomes.

Results

Mean age was 64.8 years; 45.2%, 40.1% and 14.7% were aged <65, 65–74 and ≥75 years, respectively; 69.8% were male. Cardiovascular benefits of finerenone versus placebo were consistent across age (HR 0.94 (95% CI 0.81 to 1.10) (<65 years), HR 0.84 (95% CI 0.73 to 0.98) (65–74 years), HR 0.80 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.99) (≥75 years); Pinteraction=0.42) and sex categories (HR 0.86 (95% CI 0.77 to 0.96) (male), HR 0.89 (95% CI 0.35 to 2.27) (premenopausal female), HR 0.87 (95% CI 0.73 to 1.05) (postmenopausal female); Pinteraction=0.99). Effects on HHF reduction were not modified by age (Pinteraction=0.70) but appeared more pronounced in males (Pinteraction=0.02). Kidney events were reduced with finerenone versus placebo in age groups <65 and 65–74 but not ≥75; no heterogeneity in treatment effect was observed (Pinteraction=0.51). In sex subgroups, finerenone consistently reduced kidney events (Pinteraction=0.85). Finerenone reduced albuminuria and eGFR decline regardless of age and sex. Hyperkalaemia increased with finerenone, but discontinuation rates were <3% across subgroups. Gynaecomastia in males was uncommon across age subgroups and identical between treatment groups.

Conclusions

Finerenone improved cardiovascular and kidney composite outcomes with no significant heterogeneity between age and sex subgroups; however, the effect on HHF appeared more pronounced in males. Finerenone demonstrated a similar safety profile across age and sex subgroups.

Trial registration numbers

Keywords: risk factors, diabetic nephropathy & vascular disease, diabetes & endocrinology, cardiovascular disease

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

An advantage of this study was the use of combined individual-level data from the FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD phase 3 clinical trials, resulting in a large number of patients included in the full analysis set.

This study did not use predefined age categories, as it was a post hoc analysis, which may have resulted in some of the tests performed being underpowered.

Limitations present in FIDELITY are present in this analysis, such as the small proportion of Black patients and exclusion of patients with non-albuminuric chronic kidney disease.

Introduction

In patients with diabetes, the risk of cardiovascular (CV) disease and chronic kidney disease (CKD) increases with age.1 Likewise, vascular complications are affected by sex and are increased in females more than males in patients with diabetes.2

Among individuals aged 50–75 years without baseline diabetes, CKD or CV disease, males have a steeper decline in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) than females.3 However, reported effects of sex on risk of incidental and progressive CKD in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) have been inconsistent.4–6 In trials including patients with CKD, female representation varies (25%–40%),7–11 whereas in real-world studies, females make up over half of patients.12 13

Overactivation of the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) is associated with CV and kidney diseases.14 15 In epithelial cells, the 11 β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 (11β-HSD2) enzyme prevents inappropriate MR activation by cortisol.16–18 The activity of 11β-HSD2 decreases with age, resulting in MR overactivation in the elderly despite low circulating aldosterone levels.16–18 Sex also influences 11β-HSD2 activity, particularly in patients with hypertension, where 11β-HSD2 activity is reduced in males versus females.16 The MR is also expressed in non-epithelial cells, including endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, adipocytes and immune cells.17 In many of these, the MR may be activated by cortisol because of a lack of protection by 11β-HSD2.19 20

Despite management with recommended treatments for CKD in T2D, 10%–13% of patients experience CKD progression or kidney failure and are at high risk of CV events, including CV death, within 2–3 years following treatment initiation.10 21 22 Finerenone, a selective, non-steroidal MR antagonist (MRA), reduced the risk of CKD progression and CV outcomes compared with placebo in patients with CKD and T2D in FIDELITY (The FInerenone in chronic kiDney diseasE and type 2 diabetes: Combined FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD Trial programme analYsis), a prespecified pooled analysis of the FIDELIO-DKD (FInerenone in reducing kiDnEy faiLure and dIsease prOgression in Diabetic Kidney Disease; NCT02540993) and FIGARO-DKD (FInerenone in reducinG cArdiovascular moRtality and mOrbidity in Diabetic Kidney Disease; NCT02545049) phase 3 trials.21 However, the influence of age and sex on outcomes with finerenone is unknown. This post hoc analysis evaluated whether the CV and kidney benefits and safety profile of finerenone observed in FIDELITY are consistent in patients with CKD and T2D across ages and in both sexes.

Methods

Study design and patients

FIDELITY combined individual patient-level data from the FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD phase 3 clinical trials. The study design, procedures and outcomes for the trials have been previously published.23–25 These studies were reported following the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials reporting guideline.

Eligible patients were aged ≥18 years with CKD and T2D, receiving maximum tolerated renin–angiotensin system inhibitor, and with serum potassium levels ≤4.8 mmol/L at screening. Patients had either a urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) ≥30 to <300 mg/g and an estimated GFR (eGFR) ≥25 to ≤90 mL/min/1.73 m2, or UACR ≥300 to ≤5000 mg/g and eGFR ≥25 mL/min/1.73 m2. Patients with symptomatic heart failure (HF) with reduced ejection fraction were excluded because this implies an indication for a steroidal MRA.

Standard-of-care therapy with a renin–angiotensin system inhibitor was optimised during the run-in period. Patients were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive finerenone at titrated doses (10 or 20 mg) once-daily oral treatment or matching placebo.

Key outcomes

Efficacy outcomes included a CV composite outcome of CV death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke or hospitalisation for HF (HHF), and a kidney composite outcome of kidney failure, sustained ≥57% eGFR decline or renal death. Additional outcomes included HHF and change in UACR and eGFR over time.

Safety outcomes included incidence of investigator-reported adverse events (AEs), including those leading to treatment discontinuation, central laboratory assessment of serum potassium levels >5.5 and >6.0 mmol/L, and other safety events of interest, such as hypotension, hyperkalaemia and gynaecomastia in males.

Outcomes were analysed according to patient age at baseline (<65, 65–74 and ≥75 years) and sex. Females were categorised as either premenopausal or postmenopausal if they were aged <51.4 or ≥51.4 years at baseline, respectively (based on the median age of menopause onset from the Massachusetts Women’s Health Study).26

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed as described in FIDELITY.23 The full analysis set comprised all randomised patients (except those with critical Good Clinical Practice violations, who were prospectively excluded). Safety analyses were performed in the safety analysis set (randomised patients without critical Good Clinical Practice violations who took >1 dose of study drug). The analyses were prespecified exploratory evaluations of outcomes according to age and sex, with events reported from randomisation up to the end-of-study visit. Stratified Cox proportional hazards models,27 28 including stratification factors: geographical region, eGFR and albuminuria category at screening, history of CV disease and study, were used for the analysis of time-to-event clinical outcomes. The p values for interaction between the treatment group (finerenone or placebo) and each baseline subgroup (age or sex) were based on stratified Cox proportional hazards models, accounting for the treatment effect, the subgroup effect and their interaction.

Changes in UACR and eGFR over time were assessed using a linear mixed-model analysis accounting for repeated measurements over time. The least-squares mean ratio and absolute change from baseline were estimated from the models for changes in UACR and eGFR, respectively. The two-slope, linear spline, mixed-model, repeated measure method29 was used to estimate the rate of change in eGFR across time, specifically total (annualised rate of change in eGFR from baseline to permanent discontinuation or end of study) and chronic (from month 4 to permanent discontinuation or end of study) eGFR slopes. To account for possible non-linear effects of age on clinical outcomes, age was modelled with cubic splines with three knots in Cox proportional hazards models, to produce plots of the HRs and 95% CI as functions of age and sex.

Patients and public involvement

No patient or public involvement in the current study.

Results

Patients

FIDELITY included 13 026 patients.23 Median follow-up was 3 years (IQR 2.3–3.8).23 Mean age at baseline was 64.8 years (SD 9.5), with 45.2%, 40.1% and 14.7% of patients aged <65, 65–74 and ≥75 years at baseline, respectively. Most patients (69.8%) were male; 2.5% were premenopausal females and 27.8% were postmenopausal females. Patients were distributed evenly between treatment arms within age and sex subgroups (online supplemental etable 1).

bmjopen-2023-076444supp001.pdf (1.7MB, pdf)

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics were similar across age subgroups except for some key differences (table 1). The overall FIDELITY population was predominantly White (68.1%), the proportion of which increased with age. Mean eGFR was 64, 54 and 48 mL/min/1.73 m2 in patients aged <65, 65–74 and ≥75 years, respectively. Median UACR was 650, 439 and 332 mg/g in patients aged <65, 65–74 and ≥75 years, respectively. History of CV disease was more common in the ≥75 years group; this trend was also observed for atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter.

Table 1.

Patient baseline characteristics according to age and sex

| Characteristic | All (N=13 026) |

Age | Sex | ||||

| <65 years (n=5889) |

65–74 years (n=5221) | ≥75 years (n=1916) | Male (n=9088) |

Premenopausal female (n=323) |

Postmenopausal female (n=3615) |

||

| Age, years, mean±SD | 64.8±9.5 | 56.4±6.6 | 69.2±2.8 | 78.4±3.1 | 64.8±9.5 | 45.1±4.9 | 66.3±8.0 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||||||

| Female | 3938 (30.2) | 1839 (31.2) | 1501 (28.7) | 598 (31.2) | 0 | 323 (100) | 3615 (100) |

| Male | 9088 (69.8) | 4050 (68.8) | 3720 (71.3) | 1318 (68.8) | 9088 (100) | 0 | 0 |

| Race, n (%) | |||||||

| Asian | 2894 (22.2) | 1591 (27.0) | 997 (19.1) | 306 (16.0) | 2136 (23.5) | 87 (26.9) | 671 (18.6) |

| Black/African American | 522 (4.0) | 309 (5.2) | 160 (3.1) | 53 (2.8) | 284 (3.1) | 37 (11.5) | 201 (5.6) |

| White | 8869 (68.1) | 3592 (61.0) | 3817 (73.1) | 1460 (76.2) | 6231 (68.6) | 167 (51.7) | 2471 (68.4) |

| Other* | 741 (5.7) | 397 (6.7) | 247 (4.7) | 97 (5.1) | 437 (4.8) | 32 (9.9) | 272 (7.5) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg, mean (SD) | 136.7±14.2 | 135.6±14.0 | 137.4±14.2 | 138.4±14.6 | 136.8±14.2 | 133.0±14.0 | 136.9±14.3 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg, mean (SD) | 76.4±9.6 | 78.8±9.1 | 74.9±9.4 | 72.8±9.8 | 76.5±9.7 | 80.1±8.4 | 75.6±9.5 |

| Duration of diabetes, years, mean (SD) | 15.4±8.7 | 13.5±7.6 | 16.4±8.6 | 18.6±10.4 | 15.3±8.5 | 10.6±7.0 | 16.0±9.1 |

| HbA1c, %, mean (SD) | 7.7±1.4 | 7.9±1.5 | 7.6±1.3 | 7.4±1.2 | 7.6±1.3 | 8.2±1.7 | 7.9±1.4 |

| Serum potassium, mmol/L, mean (SD) | 4.4±0.4 | 4.4±0.5 | 4.4±0.4 | 4.4±0.4 | 4.3±0.4 | 4.3±0.4 | 4.4±0.4 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2, mean (SD) | 57.6±21.7 | 64.3±24.0 | 53.5±18.5 | 48.1±15.1 | 57.7±21.2 | 77.0±28.9 | 55.6±21.3 |

| UACR, mg/g, median (Q1–Q3) | 514.68 (197.8–1147.1) | 650.48 (315.2–1363.5) | 438.63 (154.1–1030.7) | 332.29 (107.8–830.5) | 511.53 (200.9–1130.1) | 793.52 (376.6–1547.3) | 501.47 (173.6–1149.1) |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 31.3±6.0 | 32.0±6.4 | 31.1±5.7 | 29.6±5.0 | 31.0±5.6 | 34.1±7.9 | 32.0±6.6 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 2093 (16.1) | 1283 (21.8) | 686 (13.1) | 124 (6.5) | 1730 (19.0) | 35 (10.8) | 328 (9.1) |

| History of CV disease, present, n (%) | 5935 (45.6) | 2188 (37.2) | 2667 (51.1) | 1080 (56.4) | 4374 (48.1) | 56 (17.3) | 1505 (41.6) |

| History of heart failure | 1007 (7.7) | 413 (7.0) | 432 (8.3) | 162 (8.5) | 630 (6.9) | 22 (6.8) | 355 (9.8) |

| History of atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter | 1106 (8.5) | 266 (4.5) | 547 (10.5) | 293 (15.3) | 867 (9.5) | 0 | 239 (6.6) |

| Baseline medications, n (%)† | |||||||

| RAS inhibitors (ACEis/ARBs) | 13 003 (99.8) | 5876 (99.8) | 5213 (99.8) | 1914 (99.9) | 9069 (99.8) | 323 (100.0) | 3611 (99.9) |

| Beta-blockers | 6504 (49.9) | 2619 (44.5) | 2849 (54.6) | 1036 (54.1) | 4545 (50.0) | 111 (34.4) | 1848 (51.1) |

| Diuretics | 6710 (51.5) | 2790 (47.4) | 2813 (53.9) | 1107 (57.8) | 4706 (51.8) | 137 (42.4) | 1867 (51.6) |

| Statins | 9399 (72.2) | 4033 (68.5) | 3920 (75.1) | 1446 (75.5) | 6696 (73.7) | 203 (62.8) | 2500 (69.2) |

| Calcium channel blockers | 7358 (56.5) | 3127 (53.1) | 3052 (58.5) | 1179 (61.5) | 5208 (57.3) | 149 (46.1) | 2001 (55.4) |

| Insulin | 7630 (58.6) | 3637 (61.8) | 3020 (57.8) | 973 (50.8) | 5203 (57.3) | 193 (59.8) | 2234 (61.8) |

| GLP-1RA | 944 (7.2) | 492 (8.4) | 378 (7.2) | 74 (3.9) | 676 (7.4) | 30 (9.3) | 238 (6.6) |

| SGLT-2i | 877 (6.7) | 517 (8.8) | 289 (5.5) | 71 (3.7) | 671 (7.4) | 36 (11.1) | 170 (4.7) |

*Other: included American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander, not reported, multiple.

†Analysis allowed multiple drug groups for the same drug.

ACEi, ACE inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; CV, cardiovascular; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GLP-1RA, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; Q, quartile; RAS, renin–angiotensin system; SGLT-2i, sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitor; UACR, urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio.

Baseline characteristics in sex subgroups are shown in table 1.

Efficacy

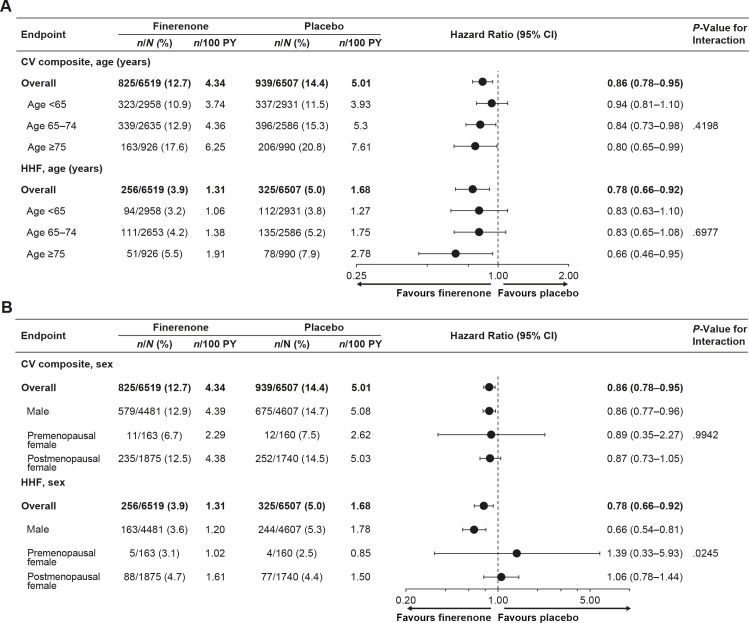

CV composite outcome by age

CV composite event rates, including the components of the composite outcome, increased with patient age in both treatment arms (figure 1A and online supplemental efigure 1A). Treatment with finerenone resulted in a numerical reduction in CV composite event rates versus placebo in all age groups (figure 1A); however, no significant heterogeneity was observed for the effect of finerenone across categorical age subgroups (Pinteraction=0.42). There was also no evidence of treatment effect modification when age was modelled as a continuous variable (Pinteraction=0.10). The trend of HR as a function of age was modelled with cubic splines (online supplemental efigure 2A).

Figure 1.

Analysis of CV composite outcome and HHF according to (A) age and (B) sex. CV composite outcome includes CV death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke or HHF. CV, cardiovascular; HHF, hospitalisation for heart failure; PY, patient-years.

HHF event rates were numerically lower with finerenone than placebo in all age subgroups (figure 1A). The effect of finerenone on HHF risk reduction was consistent across age subgroups, with no significant heterogeneity observed (Pinteraction=0.70).

CV composite outcome by sex

CV composite event rates were numerically lower with finerenone than placebo for males, premenopausal females and postmenopausal females (figure 1B and online supplemental efigure 1B). There was no significant heterogeneity in the effect of finerenone on reducing the risk of the CV composite outcome across sex subgroups (Pinteraction=0.99). When age was modelled with cubic splines by sex, the effect of finerenone was consistent with advancing age in males; however, a trend towards a stronger effect in older versus younger females was noted (online supplemental efigure 2B and C). Age distribution by sex is demonstrated in online supplemental efigure 2D.

No heterogeneity was observed in the effect of finerenone on reducing the risk of the CV death, non-fatal myocardial infarction and non-fatal stroke components of the CV composite outcome (online supplemental efigure 1B). However, statistical heterogeneity was observed in the reduction of HHF with finerenone versus placebo (Pinteraction=0.02) and the effect appeared to be more pronounced in males than premenopausal/postmenopausal females (figure 1B). These results persisted after adjustment for differences in baseline age, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, haemoglobin, eGFR, UACR, smoking history and history of atrial fibrillation between sex subgroups (Pinteraction=0.02).

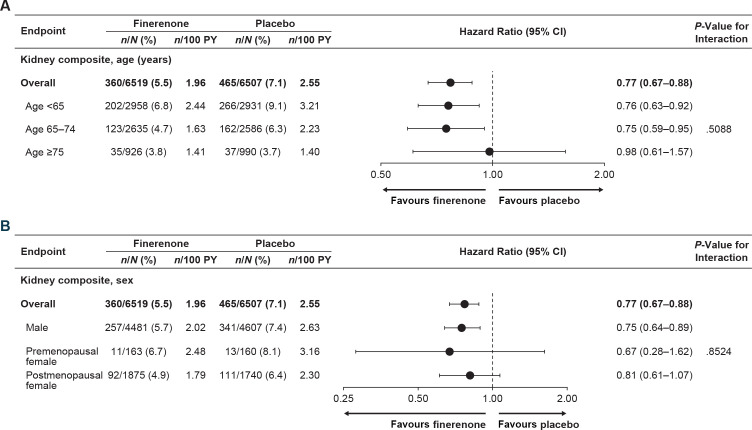

Kidney composite outcome by age

Kidney composite event rates were lower with finerenone than placebo in the <65 years and the 65–74 years groups but were similar in the ≥75 years group (figure 2A). The effect of finerenone on reducing the risk of the kidney composite outcome was consistent across age subgroups, with no significant heterogeneity detected (Pinteraction=0.51) and no evidence of treatment effect modification when age was modelled as a continuous variable (Pinteraction=0.77). The trend of HR as a function of age was modelled with cubic splines (online supplemental efigure 3A).

Figure 2.

Analysis of kidney composite outcome according to (A) age and (B) sex. Kidney composite outcome includes kidney failure, sustained ≥57% eGFR decline or renal death. eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; PY, patient-years.

Kidney composite outcome by sex

Kidney composite event rates were lower with finerenone than placebo in males but were similar in premenopausal and postmenopausal females (figure 2B). There was no significant heterogeneity in the effect of finerenone on reducing the risk of the kidney composite outcome across sex subgroups (Pinteraction=0.85). When age was modelled with cubic splines by sex subgroups, the effect of finerenone suggests trends similar to overall results in males and females across all age groups (online supplemental efigure 3B and C). Age distribution by sex is demonstrated in online supplemental efigure 3D.

Effect of finerenone on markers of kidney function and damage by age and sex

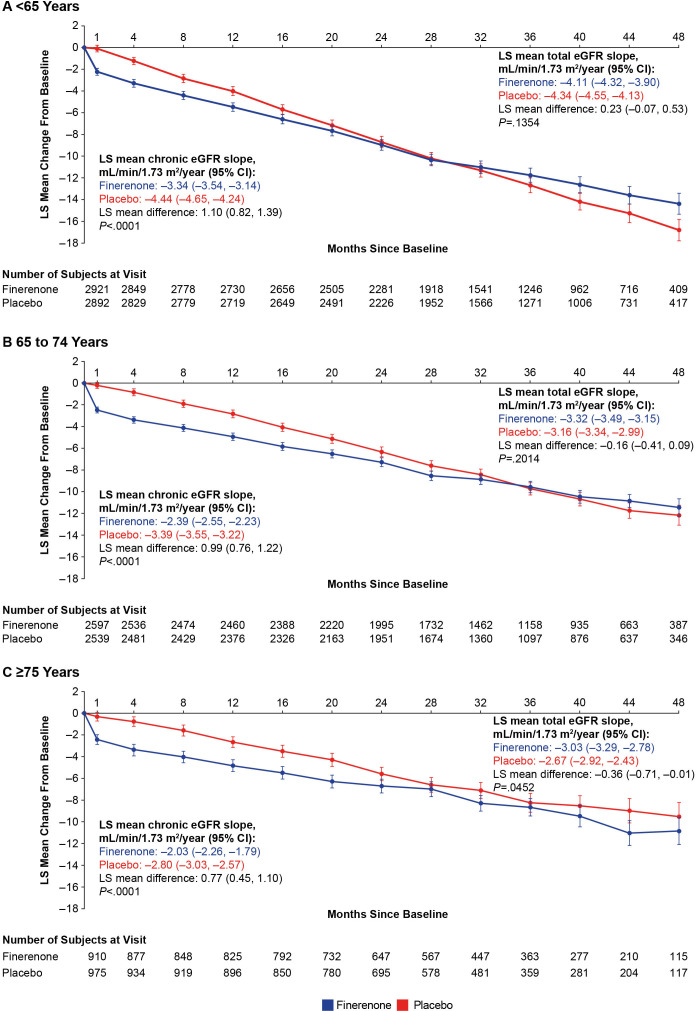

Finerenone significantly attenuated the least-squares mean change in eGFR from month four to end of treatment (chronic eGFR slope) compared with placebo across all age (p<0.0001 for all three subgroups) (figure 3) and sex subgroups (online supplemental efigure 4). Finerenone reduced UACR over time compared with placebo regardless of age and sex (online supplemental efigure 5).

Figure 3.

LS mean change in eGFR from baseline, chronic and total slopes over time by age. Chronic eGFR slope from month four to end-of-study visit. eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LS, least squares.

Safety

The incidence of any AE was similar between treatment groups irrespective of age or sex (online supplemental etable 2). There were more drug-related AEs with finerenone than placebo in age and sex subgroups except premenopausal females, where the incidence was similar. AEs leading to drug discontinuation were more frequent in patients given finerenone than placebo (6.4% and 5.4%, respectively), with higher incidences in the 65–74 and ≥75 years groups than the <65 years group; there were more AEs leading to drug discontinuation with finerenone than placebo in males and premenopausal females but not in postmenopausal females.

Although the incidences of any serious AEs (SAEs), study drug-related SAEs or SAEs leading to drug discontinuation were similar between treatment arms across all age and sex subgroups, the overall incidences of SAEs increased with age and were highest in males, followed by postmenopausal females, then premenopausal females.

In all age and sex subgroups, the incidences of treatment-emergent hypotension AEs were higher with finerenone than placebo but did not have a substantial impact on related clinical outcomes, including falls, dizziness and fatigue. A trend of increased incidence of hypotension with increasing age was observed in patients treated with finerenone; however, the incidence of hypotension was generally low across all age subgroups (<6%; online supplemental etable 2).

In FIDELITY, finerenone increased the risk of any hyperkalaemia event versus placebo; similar findings were observed in all age and sex subgroups, except premenopausal females (online supplemental etable 2). The incidences of any hyperkalaemia AEs leading to discontinuation of study drug and any serious hyperkalaemia AEs leading to hospitalisation were low across all age and sex subgroups (<3% and <2%, respectively). However, the relative risk of treatment discontinuation because of hyperkalaemia with finerenone versus placebo increased with advancing age (relative risk (95% CI) for ages 45–64, 65–74 and ≥75 years: 2.2 (1.2 to 4.3), 2.8 (1.7 to 4.7) and 4.4 (1.8 to 10.8), respectively; online supplemental efigure 6). Treatment-emergent serum potassium levels >5.5 mmol/L and >6.0 mmol/L were more frequent with finerenone than placebo, being consistent across all age and sex subgroups. The incidence of gynaecomastia in males was the same with finerenone (0.2%) and placebo (0.2%) across all ages.

Discussion

The findings of this post hoc analysis suggest that finerenone reduced the risk of CV and kidney composite outcomes versus placebo across all age and sex subcategories. In FIDELITY, HHF was the main driver of CV benefit with finerenone23; lower incidences of HHF with finerenone versus placebo were observed in this analysis across all age subgroups, with some differences noted between sex subgroups. Moreover, the incidences of any AEs or SAEs were similar between the treatment groups regardless of age and sex.

The current results are supported by findings from a pharmacokinetics (PK) analysis based on FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD data, in which both age and sex were tested as covariates for a population PK model, and their effect on finerenone exposure was not significant, suggesting a lack of influence of these factors on the PK of the drug.30 Additionally, the results for the CV outcome in this analysis are similar to findings from other studies of MRAs in HF. In TOPCAT (Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure with an Aldosterone Antagonist), age did not affect the efficacy of spironolactone in patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (primary composite outcome: CV death, aborted cardiac arrest and HHF; secondary outcomes included CV death, all-cause death and HHF).31 Moreover, in analyses of HF studies (RALES (Effect of Spironolactone on Morbidity and Mortality in Patients with Severe Heart Failure), EMPHASIS-HF (Eplerenone in Patients with Systolic Heart Failure and Mild Symptoms), and TOPCAT), MRAs reduced morbidity and mortality in elderly patients,32 demonstrating a consistent benefit regardless of sex.33 In contrast to our results, female sex was associated with poorer kidney outcomes versus male sex in patients receiving a steroidal MRA for bilateral primary aldosteronism.34 The MR can be activated by different drivers in different diseases; MR activation in diabetes is driven by additional factors other than high aldosterone in comparison with primary aldosteronism, which may account for differences in outcomes observed across different indications.35

In this study, the elderly population had higher risk of certain AEs including hypotension, AEs leading to discontinuation, and death. Hypotension occurred more frequently in the finerenone group but did not seem to substantially affect related clinical outcomes. Hyperkalaemia was more prevalent with finerenone but was generally similar across age and sex. In a FIDELIO-DKD subanalysis, younger age and female sex were independent risk factors for hyperkalaemia (>6.0 mmol/L).36 Similar findings for age were observed in TOPCAT post hoc data for patients with HF.31 Steroidal MRAs have been associated with gynaecomastia in males,37 38 which was not observed in this study, most likely because finerenone has no detectable affinity for androgen receptors.38

Preclinical data suggest that different molecular mechanisms drive endothelial dysfunction in male and female mice39 40 and that increased age and male sex are associated with MR overactivation, which is linked to vascular stiffness and endothelial dysfunction.41 42 In human aortic smooth muscle cells, MR expression increased with age, leading to epigenetic changes associated with increased vascular stiffness. These effects were reversed with MR inhibition.43 In vitro, MR expression in the whole aortae and early passage aortic vascular smooth muscle cells was increased in aged (30 months) versus adult (8 months) rat cells.41 In a preclinical mouse model, aortic stiffness occurred earlier in male than female mice and correlated with the timing of increased aortic MR expression; vascular stiffness was prevented in smooth muscle cell MR-deficient mice.42 These data suggest that elderly males may derive the greatest benefit from finerenone; indeed, in this analysis, finerenone-treated males had lower risk of the CV composite outcome and HHF versus placebo across age groups, including ≥75 years. Moreover, statistical heterogeneity was observed for HHF by sex, persisting after adjustment for differences in baseline characteristics, which might suggest a more pronounced effect of finerenone on HHF reduction in the male subgroup compared with the two female subgroups. However, because of the small sample size of the sex subgroups (especially that of the premenopausal female subgroup), definitive conclusions cannot be reached based on this finding.

In this study, markers of kidney damage (eGFR decline and UACR) were reduced with finerenone in age subgroups; however, no benefit on kidney outcomes was observed in the ≥75 years age group. The small sample size of this subgroup precluded definitive conclusions, which may be accounted for by the slowing rate of CKD progression with advancing age.44 45

Limitations include the study being a post hoc analysis and the chosen age categories not being predefined. In addition, patients may have initiated other treatments during the study. Sample size and number of events for females, particularly premenopausal females, were small. Therefore, there is uncertainty around the estimates and the analysis was underpowered to draw meaningful conclusions in this subgroup. Results for premenopausal females versus postmenopausal females/males should be interpreted with caution because age may partly account for differences observed; the average age of premenopausal females was ~45 years compared with postmenopausal females (~66 years) and males (~65 years). As such, these groups had different baseline characteristics. Higher baseline mean eGFR and median UACR, and lower history of CV comorbidities and hypotension were observed in premenopausal females versus males and postmenopausal females. Additionally, the study design and tests performed may have been underpowered to address the research questions. Furthermore, FIDELITY limitations, mainly the small proportion of Black patients and exclusion of patients with non-albuminuric CKD, were present in this analysis.

In conclusion, this post hoc FIDELITY analysis suggests that finerenone effectively lowers the risk of clinically important CV and kidney outcomes in patients with CKD and T2D across ages and sexes, with a potentially more pronounced effect on HHF in males than in females. No new safety concerns were identified in those aged ≥65 years or by sex.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Medical writing assistance was provided by Fay Nikolopoulou, MSc and Ines Neves, MSc of Chameleon Communications International and was funded by Bayer AG.

Footnotes

Collaborators: The FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD Investigators.

Contributors: SB prepared the initial analysis and is the manuscript guarantor; SB, MEFC, RB, SDA, GLB, GF, PR, LMR, AEF, PK, AL, MB and BP had access to and participated in the interpretation of the data. SB developed the initial manuscript draft, which was then reviewed and edited by MEFC, RB, SDA, GLB, GF, PR, LMR, AEF, PK, AL, MB and BP. SB, MEFC, RB, SDA, GLB, GF, PR, LMR, AEF, PK, AL, MB and BP vouch for the completeness and accuracy of the data and agreed to submit the manuscript for publication. The executive committee (including SDA, GLB, GF, PR, LMR and BP) in collaboration with the funder (including AEF, PK, AL and MB) designed the trials and protocols and supervised trial conduct.

Funding: This work was supported by Bayer AG, who funded the FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD studies and combined analysis. Grant/ award number: not applicable.

Disclaimer: The funder also had a role in the management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: SB reports research support from 3ive, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis and Novo Nordisk; honorarium from UpToDate; consultancy fees from Baxter; and speaker bureau fees from Home Dialysis University and PD Excellence Academy. MEFC reports consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Fresenius Medical Care, and research support from Baxter and Fresenius. RB reports consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Gilead, MSD, Mundipharma, Sanofi and Servier. SDA reports grants from Abbott Vascular and Vifor International; and personal fees from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, BioVentrix, Brahms, Cardiac Dimensions, Cardior, Cordio, CVRx, Edwards, Impulse Dynamics, Janssen, Novartis, Occlutech, Respicardia, Servier, Vectorious and V-Wave. GLB reports consultancy fees from Alnylam, Ionis and Merck. GF is a trial committee member for Amgen, Bayer (no fees received), Boehringer Ingelheim, Medtronic, Novartis, Servier and Vifor. PR reports personal fees from Bayer during the conduct of the study; he has received research support and personal fees from AstraZeneca and Novo Nordisk, and personal fees from Astellas, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Gilead, Mundipharma, Sanofi and Vifor; all fees are given to Steno Diabetes Center Copenhagen. LMR reports consultancy fees from Bayer. AEF, PK, AL and MB are all full-time employees of Bayer. BP reports consultant fees for AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Brainstorm Medical, Cereno Scientific, G3 Pharmaceuticals, KBP Biosciences, PhaseBio, Proton Intel, Sanofi/Lexicon, Sarfez, scPharmaceuticals, SQ Innovation, Tricida, and Vifor/Relypsa; he has stock options for Brainstorm Medical, Cereno Scientific, G3 Pharmaceuticals, KBP Biosciences, Proton Intel, Sarfez, scPharmaceuticals, SQ Innovation, Tricida, and Vifor/Relypsa; he also holds a patent for site-specific delivery of eplerenone to the myocardium (US patent #9931412) and a provisional patent for histone-acetylation-modulating agents for the treatment and prevention of organ injury (provisional patent US 63/045784).

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Availability of the data underlying this publication will be determined according to Bayer’s commitment to the EFPIA/PhRMA 'Principles for responsible clinical trial data sharing'. This pertains to scope, time point and process of data access. As such, Bayer commits to sharing on request from qualified scientific and medical researchers patient-level clinical trial data, study-level clinical trial data and protocols from clinical trials in patients for medicines and indications approved in the USA and European Union (EU) as necessary for conducting legitimate research. This applies to data on new medicines and indications that have been approved by the EU and US regulatory agencies on or after 1 January 2014. Interested researchers can use www.vivli.org to request access to anonymised patient-level data and supporting documents from clinical studies to conduct further research that can help advance medical science or improve patient care. Information on the Bayer criteria for listing studies and other relevant information is provided in the member section of the portal. Data access will be granted to anonymised patient-level data, protocols and clinical study reports after approval by an independent scientific review panel. Bayer is not involved in the decisions made by the independent review panel. Bayer will take all necessary measures to ensure that patient privacy is safeguarded.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and these trials were performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the competent authorities and ethic committees at each site. All participants provided written informed consent. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1. Halter JB, Musi N, McFarland Horne F, et al. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease in older adults: Current status and future directions. Diabetes 2014;63:2578–89. 10.2337/db14-0020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Maric-Bilkan C. Sex differences in micro- and macro-vascular complications of diabetes mellitus. Clin Sci (Lond) 2017;131:833–46. 10.1042/CS20160998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Melsom T, Norvik JV, Enoksen IT, et al. Sex differences in age-related loss of kidney function. J Am Soc Nephrol 2022;33:1891–902. 10.1681/ASN.2022030323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bairey Merz CN, Dember LM, Ingelfinger JR, et al. Sex and the kidneys: Current understanding and research opportunities. Nat Rev Nephrol 2019;15:776–83. 10.1038/s41581-019-0208-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Maric-Bilkan C. Sex differences in diabetic kidney disease. Mayo Clin Proc 2020;95:587–99. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yu MK, Lyles CR, Bent-Shaw LA, et al. Risk factor, age and sex differences in chronic kidney disease prevalence in a diabetic cohort: The Pathways Study. Am J Nephrol 2012;36:245–51. 10.1159/000342210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, et al. Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2019;380:347–57. 10.1056/NEJMoa1812389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Heerspink HJL, Stefánsson BV, Correa-Rotter R, et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1436–46. 10.1056/NEJMoa2024816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zannad F, Ferreira JP, Pocock SJ, et al. Cardiac and kidney benefits of empagliflozin in heart failure across the spectrum of kidney function: Insights from EMPEROR-Reduced. Circulation 2021;143:310–21. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.051685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, et al. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2019;380:2295–306. 10.1056/NEJMoa1811744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. EVOLVE Trial Investigators, Chertow GM, Block GA, et al. Effect of cinacalcet on cardiovascular disease in patients undergoing dialysis. N Engl J Med 2012;367:2482–94. 10.1056/NEJMoa1205624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tuttle KR, Alicic RZ, Duru OK, et al. Clinical characteristics of and risk factors for chronic kidney disease among adults and children: An analysis of the CURE-CKD Registry. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e1918169. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.18169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gasparini A, Evans M, Coresh J, et al. Prevalence and recognition of chronic kidney disease in Stockholm healthcare. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2016;31:2086–94. 10.1093/ndt/gfw354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Buonafine M, Bonnard B, Jaisser F. Mineralocorticoid receptor and cardiovascular disease. Am J Hypertens 2018;31:1165–74. 10.1093/ajh/hpy120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Luther JM, Fogo AB. The role of mineralocorticoid receptor activation in kidney inflammation and fibrosis. Kidney Int Suppl 2022;12:63–8. 10.1016/j.kisu.2021.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Henschkowski J, Stuck AE, Frey BM, et al. Age-dependent decrease in 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 (11beta-Hsd2) activity in hypertensive patients. Am J Hypertens 2008;21:644–9. 10.1038/ajh.2008.152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kolkhof P, Jaisser F, Kim S-Y, et al. Steroidal and novel non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in heart failure and cardiorenal diseases: Comparison at bench and bedside. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2017;243:271–305. 10.1007/164_2016_76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pitt B. The role of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs) in very old patients with heart failure. Heart Fail Rev 2012;17:573–9. 10.1007/s10741-011-9286-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cole TJ, Young MJ. 30 years of the mineralocorticoid receptor: Mineralocorticoid receptor null mice: Informing cell-type-specific roles. J Endocrinol 2017;234:T83–92. 10.1530/JOE-17-0155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nakamura T, Girerd S, Jaisser F, et al. Nonepithelial mineralocorticoid receptor activation as a determinant of kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 2022;12:12–8. 10.1016/j.kisu.2021.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wheeler DC, Stefánsson BV, Jongs N, et al. Effects of dapagliflozin on major adverse kidney and cardiovascular events in patients with diabetic and non-diabetic chronic kidney disease: A prespecified analysis from the DAPA-CKD trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2021;9:22–31. 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30369-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mann JFE, Fonseca V, Mosenzon O, et al. Effects of liraglutide versus placebo on cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease. Circulation 2018;138:2908–18. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.036418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Agarwal R, Filippatos G, Pitt B, et al. Cardiovascular and kidney outcomes with finerenone in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease: The FIDELITY pooled analysis. Eur Heart J 2022;43:474–84. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bakris GL, Agarwal R, Anker SD, et al. Effect of finerenone on chronic kidney disease outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2020;383:2219–29. 10.1056/NEJMoa2025845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pitt B, Filippatos G, Agarwal R, et al. Cardiovascular events with finerenone in kidney disease and type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2021;385:2252–63. 10.1056/NEJMoa2110956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McKinlay SM, Brambilla DJ, Posner JG. The normal menopause transition. Maturitas 1992;14:103–15. 10.1016/0378-5122(92)90003-m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kleinbaum DG, Klein M. The stratified Cox procedure. In: Kleinbaum DG, Klein M, eds. Survival analysis: A self-learning text. New York, NY: Springer, 2012. 10.1007/978-1-4419-6646-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Therneau TM, Grambsch PM. The Cox model. In: Therneau TM, Grambsch PM, eds. Modeling survival data: Extending the Cox model. New York, NY: Springer, 2000. 10.1007/978-1-4757-3294-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vonesh E, Tighiouart H, Ying J, et al. Mixed-effects models for slope-based endpoints in clinical trials of chronic kidney disease. Stat Med 2019;38:4218–39. 10.1002/sim.8282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Eissing T, Goulooze SC, van den Berg P, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of finerenone in patients with chronic kidney disease and type 2 diabetes: Insights based on FIGARO-DKD and FIDELIO-DKD. Diabetes Obes Metab 2024;26:924–36. 10.1111/dom.15387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vardeny O, Claggett B, Vaduganathan M, et al. Influence of age on efficacy and safety of spironolactone in heart failure. JACC Heart Fail 2019;7:1022–8. 10.1016/j.jchf.2019.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ferreira JP, Rossello X, Eschalier R, et al. MRAs in elderly HF patients: Individual patient-data meta-analysis of RALES, EMPHASIS-HF, and TOPCAT. JACC Heart Fail 2019;7:1012–21. 10.1016/j.jchf.2019.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rossello X, Ferreira JP, Pocock SJ, et al. Sex differences in mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist trials: A pooled analysis of three large clinical trials. Eur J Heart Fail 2020;22:834–44. 10.1002/ejhf.1740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nakamaru R, Yamamoto K, Akasaka H, et al. Sex differences in renal outcomes after medical treatment for bilateral primary aldosteronism. Hypertension 2021;77:537–45. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.16449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kawanami D, Takashi Y, Muta Y, et al. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in diabetic kidney disease. Front Pharmacol 2021;12:754239. 10.3389/fphar.2021.754239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Agarwal R, Joseph A, Anker SD, et al. Hyperkalemia risk with finerenone: Results from the FIDELIO-DKD trial. J Am Soc Nephrol 2022;33:225–37. 10.1681/ASN.2021070942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hasegawa T, Nishiwaki H, Ota E, et al. Aldosterone antagonists for people with chronic kidney disease requiring dialysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2021;2:CD013109. 10.1002/14651858.CD013109.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kolkhof P, Joseph A, Kintscher U. Nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism for cardiovascular and renal disorders – New perspectives for combination therapy. Pharmacol Res 2021;172:105859. 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Davel AP, Jaffe IZ, Tostes RC, et al. New roles of aldosterone and mineralocorticoid receptors in cardiovascular disease: Translational and sex-specific effects. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2018;315:H989–99. 10.1152/ajpheart.00073.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Faulkner JL, Kennard S, Huby A-C, et al. Progesterone predisposes females to obesity-associated leptin-mediated endothelial dysfunction via upregulating endothelial MR (mineralocorticoid receptor) expression. Hypertension 2019;74:678–86. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.12802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Krug AW, Allenhöfer L, Monticone R, et al. Elevated mineralocorticoid receptor activity in aged rat vascular smooth muscle cells promotes a proinflammatory phenotype via extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinase and epidermal growth factor receptor-dependent pathways. Hypertension 2010;55:1476–83. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.148783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. DuPont JJ, Kim SK, Kenney RM, et al. Sex differences in the time course and mechanisms of vascular and cardiac aging in mice: Role of the smooth muscle cell mineralocorticoid receptor. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2021;320:H169–80. 10.1152/ajpheart.00262.2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ibarrola J, Kim SK, Lu Q, et al. Smooth muscle mineralocorticoid receptor as an epigenetic regulator of vascular aging. Cardiovasc Res 2023;118:3386–400. 10.1093/cvr/cvac007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mathur R, Dreyer G, Yaqoob MM, et al. Ethnic differences in the progression of chronic kidney disease and risk of death in a UK diabetic population: An observational cohort study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e020145. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Go AS, Yang J, Tan TC, et al. Contemporary rates and predictors of fast progression of chronic kidney disease in adults with and without diabetes mellitus. BMC Nephrol 2018;19:146. 10.1186/s12882-018-0942-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2023-076444supp001.pdf (1.7MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Availability of the data underlying this publication will be determined according to Bayer’s commitment to the EFPIA/PhRMA 'Principles for responsible clinical trial data sharing'. This pertains to scope, time point and process of data access. As such, Bayer commits to sharing on request from qualified scientific and medical researchers patient-level clinical trial data, study-level clinical trial data and protocols from clinical trials in patients for medicines and indications approved in the USA and European Union (EU) as necessary for conducting legitimate research. This applies to data on new medicines and indications that have been approved by the EU and US regulatory agencies on or after 1 January 2014. Interested researchers can use www.vivli.org to request access to anonymised patient-level data and supporting documents from clinical studies to conduct further research that can help advance medical science or improve patient care. Information on the Bayer criteria for listing studies and other relevant information is provided in the member section of the portal. Data access will be granted to anonymised patient-level data, protocols and clinical study reports after approval by an independent scientific review panel. Bayer is not involved in the decisions made by the independent review panel. Bayer will take all necessary measures to ensure that patient privacy is safeguarded.