Abstract

Numerous recent studies using single cell RNA sequencing and spatial transcriptomics have shown the vast cell heterogeneity, including epithelial, immune, and stromal cells, present in the normal human stomach and at different stages of gastric carcinogenesis. Fibroblasts within the metaplastic and dysplastic mucosal stroma represent key contributors to the carcinogenic microenvironment in the stomach. The heterogeneity of fibroblast populations is present in the normal stomach, but plasticity within these populations underlies their alterations in association with both metaplasia and dysplasia. In this review, we summarize and discuss efforts over the past several years to study the fibroblast components in human stomach from normal to metaplasia, dysplasia, and cancer. In the stomach, myofibroblast populations increase during late phase carcinogenesis and are a source of matrix proteins. PDGFRA-expressing telocyte-like cells are present in normal stomach and expand during metaplasia and dysplasia in close proximity with epithelial lineages, likely providing support for both normal and metaplastic progenitor niches. The alterations in fibroblast transcriptional signatures across the stomach carcinogenesis process indicate that fibroblast populations are likely as plastic as epithelial populations during the evolution of carcinogenesis.

Keywords: SPEM, metaplasia, dysplasia, PDGRFA, telocyte

Summary.

Single cell analyses have defined fibroblast populations present during stomach carcinogenesis. We discuss major genes expressed and the categorization of these fibroblast populations into 4 major subpopulations. Fibroblasts in the precancerous mucosa may drive progression of metaplastic lineages into cancer.

Epithelial alterations during the induction of metaplasia in the stomach have received considerable attention recently, and other studies have noted the association of these mucosal changes with the influence of M2-macrophages and type 2-innate lymphoid cells.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 The intestinal type of gastric cancer develops within a field of oxyntic atrophy and metaplasia,7 and recent studies have redefined a sequence of metaplastic changes initiated by pyloric metaplasia in response to parietal cell loss.5 Continued inflammation leads to the progression of pyloric metaplasia into incomplete intestinal metaplasia, which is most associated with the development of dysplasia and adenocarcinoma.8, 9, 10, 11 Linked with alterations in mucosal lineages, there is a considerable expansion of stromal elements, but relatively less is known about the changes in fibroblast populations in the metaplastic and dysplastic mucosa. In this article, we will discuss recent investigations related to fibroblast populations in the stomach under normal conditions and during gastric carcinogenesis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Diverse Fibroblast Populations Found Across the Normal, Metaplastic, and Dysplastic/Cancerous Human Stomach Using scRNA Sequencing

| Fibroblast subtypes | Fibroblast defining markers | Additional markers | Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDGFRA+ telocyte-like fibroblasts | PDGFRAhi | POSTN, BMP4, CXCL14, and TGFBI | Lee et al12 |

| Inflammatory fibroblasts | FBLN2hi | DCN, CFD, FBLN1, RSPO3 and IGFBP6 | |

| Myofibroblasts | ACTA2hi and PDGFRBlo | ADIRF, MYL9, TAGLN, and TPM2 | |

| Pericytes | ACTA2hi and PDGFRBhi | RGS5, NDUFA4L2, CSPG4, NOTCH3, and ENPEP | |

| Kruppel-like factor cells | KLF | KLF4, SFRP1, SFRP2, and PI16 | Tsubosaka et al13 |

| CCL11+ fibroblasts | CCL11 | CCL11, ABCA8, APOE, and ADAM28 | |

| PDGFRA+ fibroblasts | PDGFRA | PLAT, POSTN, BMP4, and WNT5A | |

| Fibroblasts that express fibroblastic and smooth muscle markers | ACTG2 | HHIP, MYLK, and BARX1 | |

| Pericyte-like | RGS5 | TAGLN and CD36 | |

| Pericytes with smooth muscle markers | ADIRF | RERGL, MYH11, and TAGLN | |

| Inflammatory fibroblasts | STC1 | IL6, IL11, IL24, CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL5, CXCL6, MMP1, MMP3, and MMP10 | Kim et al14 |

| Myofibroblasts | TAGLN | TPM1, TPM2, MYL9, and EGR1 | |

| Intermediate CAFs | TGFβ | PDGFRA, POSTN, ID1, and ID3 | |

| PDGFRA+ fibroblasts | PDGFRAhi | PLAT, POSTN, and PDGFRA | Huang et al15 |

| HHIP+ myofibroblasts | HHIPhi | HHIP, ACTA2, and TAGLN | |

| Fibroblasts that express immune cell recruitment factors | PDGFRAhi, PDPNhi, and CD34hi | CXCL12, CFD, C3, C1S, CFH | Nowicki-Osuch et al16 |

| Fibroblasts that express extracellular matrix components | PDGFRAhi, PDPNhi, and CD34lo | CXCL14, POSTN, COL6A1, and COL6A2 | |

| Myofibroblasts | ACTA2 | MYL9 and ACTG2 | |

| Pericyte-like | CSPG4hi | PDGFA, ASPN, and S100A4 | Kumar et al17 |

| CAF-like | FAPhi | COL8A1, THBS2, and CTHRC1 | |

| Myofibroblasts | ACTA2hi | THY1, DCN, COL4A1, FAP | Sathe et al18 |

| Pericytes | PDGFRBhi | RSG5, PDGFRB |

Fibroblasts in Normal Human Gastric Mucosa

Stromal cells represent mesenchymal lineages found in the interstitial lamina propria of major organs and connective tissues.19 Stromal cells consist of multiple cell types, including fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, and pericytes, and have distinguishing features of elongated cytoplasmic projections and spindle-shaped nuclei.20 Fibroblasts produce extracellular matrix, including collagen, proteoglycans, and fibronectin.21 In gastrointestinal organs, fibroblasts are generally known to maintain epithelial homeostasis and respond to environmental stimuli from mucosal infection or injury and are thought to support the proliferative niche with secretion of growth factors.22,23 However, current knowledge of fibroblast functions and characteristics in the normal stomach tissue is not extensive and relies on recent investigations using single cell techniques. Both the normal rodent and human gastric mucosa present rather sparse fibroblast populations. Sigal et al24 found that stromal cells located in the base of stomach antral glands secrete R-spondin (Rspo). Using different mouse models and fluorescence in situ hybridization, they demonstrated that fibroblasts near the base of antral glands expressed both α-smooth muscle actin (aSMA, ACTA2 gene) and RSPO3. This finding was confirmed in in vitro culture of human primary antral myofibroblasts through quantitative polymerase chain reaction and immunoblotting, suggesting that human antral myofibroblasts also secrete RSPO3.24 Moreover, they demonstrated that RSPO3 is a critical niche-specific regulator in coordinating the homeostasis and proliferation of the epithelial stem cells located at the base of mouse antral glands.

Pastula et al25 demonstrated that co-culture of myofibroblasts with gastric organoids supported the growth of the organoids and suggested that fibroblasts release niche factors crucial for the proliferation of epithelial stem cells. In accordance with these findings, our recent study12 described 4 distinctive fibroblast populations in the normal human stomach. ACTA2-expressing myofibroblasts population represented the major population in the normal stomach mucosa, even with gastritis. The studies by Pastula et al and Sigal et al24 did not involve single cell analysis, and so the assignment of populations as myofibroblasts based on aSMA immunostaining or ACTA2 expression alone may be overcategorizing fibroblasts as myofibroblasts. Nevertheless, all these studies suggest that fibroblasts with a transcription profile aligned with myofibroblasts and high expression of ACTA2 (aSMA) might represent the major population in the stromal compartment that oversees the homeostasis of stomach glands under normal circumstances.

A recent study by Tsubosaka et al13 used single cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and spatial transcriptomics to profile cell lineages of the human stomach with normal and intestinal metaplasia areas from a total of 32 sample patients. In the normal stomach mucosa, they identified a population with high expression of myofibroblast-related markers including ACTG2, HHIP, MYLK, and BARX1. BARX1 is a stomach-specific transcription factor and is involved in stomach development.26 RNA in situ hybridization confirmed the presence of BARX1-expressing fibroblasts in the lamina propria of corpus and antral mucosa, suggesting an interaction between BARX1-expressing myofibroblasts and normal gastric epithelial cells.13 Although myofibroblast populations are predominant in the normal stomach mucosa, 3 other fibroblast populations were also identified in our studies, indicating that heterogenous fibroblast populations are present in the normal mucosal milieu.12

Fibroblasts Associated With Human Stomach Metaplasia

Stomach metaplasia develops initially as a reparative mechanism after significant gastric damage.5,27 Pyloric metaplasia represents the first metaplastic gland structure in injured mucosa, with the presence of a metaplastic cell lineage, spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia (SPEM) cells, at the base and foveolar hyperplasia toward the lumen.6,28,29 This alteration in glandular cell lineages leads to the emergence of a zone with proliferative SPEM cells at the bases of pyloric metaplasia glands distinct from the isthmal progenitor cell zone in the upper third of normal corpus glands.11 Pyloric metaplasia can then give rise to incomplete intestinal metaplasia glands, which show SPEM cells toward the bottom of glands.11 These findings suggest that the process of metaplasia development alters the location of proliferative cells. Because of this restructuring of gland composition and spatial location of cells, it would seem likely that stromal changes must be involved in the reestablishment of major proliferating cell niche in the metaplastic glands. Initial studies in mice30 demonstrated that Helicobacter felis infection increased myofibroblasts in the mouse stomach, in part through derivation from bone marrow cells and mesenchymal stem cells. Shibata et al31 found that stromal myofibroblasts expand in the gastric corpus mucosa after up-regulation of SDF-1, a chemokine ligand for CXCR4, after Helicobacter infection. These studies suggested changes in myofibroblasts attendant with induction of oxyntic atrophy and metaplasia.

Other studies reported the presence of a pericryptal fibroblast sheath (PCFS)32 in mouse and human stomachs with intestinal metaplasia. The PCFS surrounded glands in mouse and human stomach areas with CDX2-expressing intestinal metaplasia but were absent in normal stomach tissues. Liu et al33 reported similar findings in a series of gastric mucosa tissues with normal, intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and gastric cancer sections. More recently, researchers have detailed a specific fibroblast lineage expressing FoxL1 and Pdgfra as telocytes present within the PCFS in the small intestine.34 Telocytes, fibroblast cells with elongated cytoplasmic processes, represent a distinctive stromal cell type.35 The exact role of telocytes in maintaining the proliferative niche in normal or metaplastic stomach has not been evaluated.

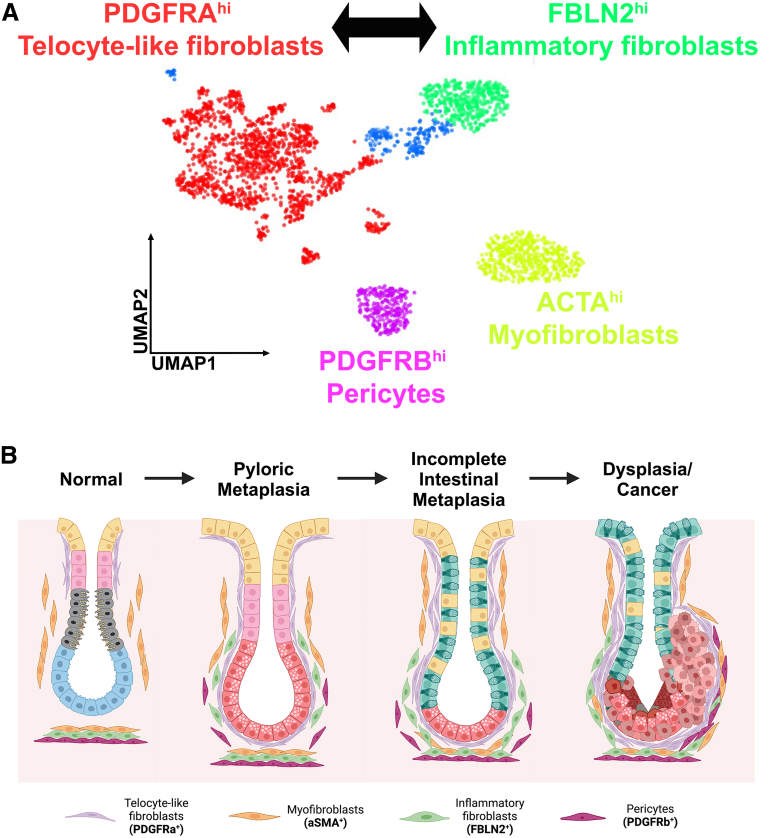

Our recent investigations identified 4 distinctive fibroblast populations present in the human stomach stroma (Figure 1A)12: one with high PDGFRA (PDGFRAhi) expression and enriched in genes related to extracellular matrix organization and cell motility (telocyte-like fibroblasts), one with high FBLN2 (FBLN2hi) expression and enriched in genes related to inflammatory pathways (inflammatory fibroblasts), one with high ACTA2 (ACTA2hi) and low PDGFRB (PDGFRBlo) expression and enriched in genes related to myofibroblasts (myofibroblasts), and one with ACTA2Lo, PDGFRBhi expression and enriched in genes related to pericytes. All 4 populations were present in stomach with inflamed normal, metaplastic, and dysplastic/cancerous areas. As previous studies have reported, fibroblasts with ACTA2hi represented a major population in normal stomach mucosa. Of note, PDGFRAhi fibroblasts and FBLN2hi fibroblasts were significantly expanded in metaplastic tissues, and PDGFRAhi fibroblasts were also prominent in dysplastic/cancerous tissues. In addition, PDGFRAhi fibroblasts were observed in the isthmus region of corpus glands in normal stomach epithelia, where progenitor cells are usually located (Figure 1B). In metaplastic mucosa, PDGFRAhi fibroblasts were observed in close proximity with SPEM cells with extended morphology wrapping around gland bases, consistent with the properties of telocytes.12

Figure 1.

Fibroblasts populations observed in human stomach carcinogenesis. (A) Single-cell RNA sequencing from different studies described a consensus of 4 major populations of fibroblasts in the human stomach: PDGFRA+ telocyte-like fibroblasts, FBLN2+ inflammatory fibroblasts, ACTA2+ myofibroblasts, and PDGFRB+ pericyte-like fibroblasts. (B) This illustration depicts the geographic location of fibroblasts at different stages in the process of gastric carcinogenesis from normal to pyloric metaplasia to incomplete intestinal metaplasia to dysplasia/cancer. PDGFRA-expressing telocyte-like fibroblasts are located closest to the epithelial cell lineages, with myofibroblasts tending to be more distant.

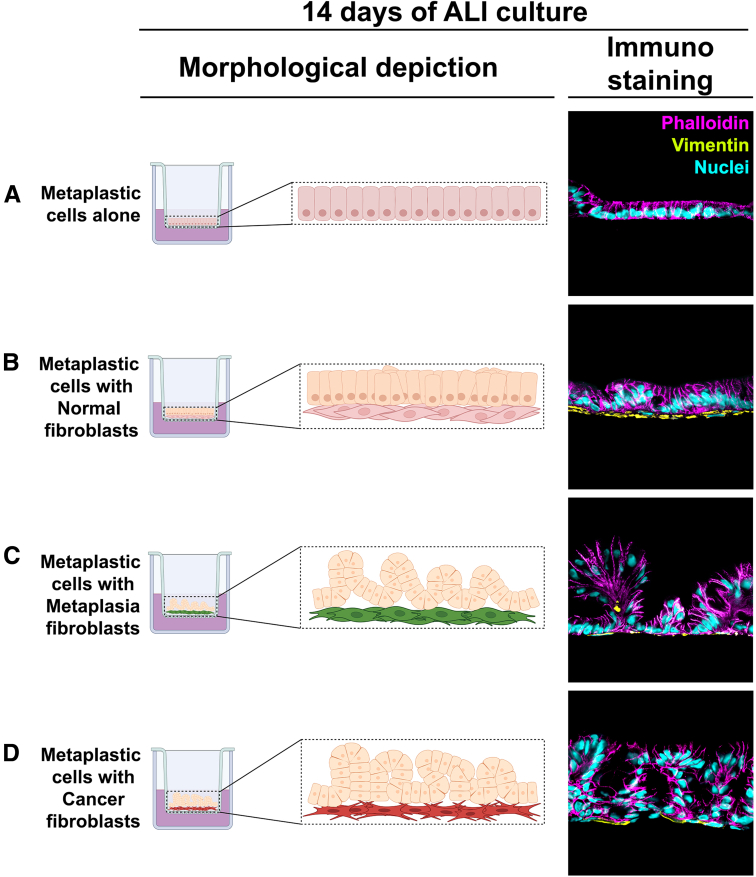

Although several studies have noted the geographic association of fibroblasts with metaplastic or cancerous epithelia, few studies sought to address how fibroblasts might be influencing the behavior of metaplastic cells. Importantly, we compared the ability of different fibroblast populations to influence the phenotypes of gastroids with a metaplastic phenotype dominated by SPEM cells.12 In Air-Liquid Interface co-cultures examining direct interaction of fibroblasts with metaplastic cells, fibroblasts isolated from both metaplasia-bearing and dysplasia/cancer-bearing mucosa induced loss of metaplasia markers and up-regulation of dysplasia markers as well as generation of polypoid morphologies (Figure 2).12 No changes in metaplastic cell markers were observed in co-culture with fibroblasts isolated from normal gastric mucosa (Figure 2). These studies demonstrated for the first time that fibroblasts directly promote dysplastic transition in metaplastic cell lineages.

Figure 2.

Co-culture of metaplastic human gastroid cells with fibroblasts using Air Liquid (ALI) Interface promoted metaplasia transition toward dysplasia. In vitro Transwell culture of metaplastic gastroid cells alone (A) or directly on top of fibroblasts derived from inflamed normal (B), metaplasia (C), and dysplasia-bearing mucosa (D) was performed using the ALI technique. After 14 days of ALI culture, metaplasia- and cancer-derived fibroblasts triggered progression into dysplasia that was observed by polypoid morphologic changes (C and D) in association with up-regulation of dysplasia-related markers (TROP2 and CEACAM5) and the loss of metaplasia-related markers (CD44v9).26 None of these changes were observed in metaplastic gastroid cells grown alone or on top of inflamed normal-derived fibroblasts (A and B).

In the intestine, telocytes are located in submucosal regions near stem cells and are important for epithelial integrity because of their functional release of BMP and WNT ligands.34,36,37 According to our single cell transcriptomic profile,12 PDGFRAhi fibroblasts uniquely express WNT4, WNT5A, BMP2, and BMP4, suggesting that production of critical niche factors is a major function for telocyte-like cells in the stomach. Furthermore, because of their location in the isthmus regions of normal corpus glands in the stomach, it is also likely that PDGFRA-positive fibroblasts are important for maintaining normal progenitor/stem cell niche in the corpus. In addition, because of the presence and immediate proximity to metaplastic and dysplastic cell lineages,12 PDGFRA-positive fibroblasts likely support the establishment of an alternative proliferative cell zone in metaplastic glands.

Using both scRNA-seq and spatial transcriptomics information, Tsubosaka et al13 described 6 populations of fibroblasts in the human stomach. One of these populations demonstrated a unique high expression of PDGFRA, BMP4, WNT5A, and POSTN similar to the expression pattern in PDGFRAhi fibroblasts observed in our study.12 Further investigation using RNA in situ hybridization in the PDGFRA and BMP4 co-expressing fibroblasts revealed that they were infrequently present in areas with normal mucosa but prominently observed surrounding and in close proximity to intestinal metaplasia lineages.13 These results were confirmed with spatial transcriptomic assays. Moreover, BMP4-expressing fibroblasts increased from normal gastric mucosa to intestinal metaplasia, suggesting that BMP4 increases in fibroblasts promote pyloric metaplasia progression to intestinal metaplasia. Additional gene-regulatory network analysis of PDGFRA-expressing fibroblasts revealed that the FOXL1 transcription factor was up-regulated, suggesting that the PDGFRA-expressing cells likely represent a major telocyte population in the stomach, as we have observed.12

In addition, recent studies14, 15, 16 described the presence of major fibroblast populations in precancerous lesions of human stomach. After performing scRNA-seq of patient biopsies, Kim et al14 defined in silico a telocyte-like population with high PDGFRA expression, mostly associated with intestinal metaplasia. These observations corroborate previous findings of a major telocyte population in the stomach.12 Similarly, Huang et al15 analyzed a large patient cohort with intestinal metaplasia using spatial single-cell transcriptomics. They defined 2 fibroblast populations in human intestinal metaplasia samples. One population was PDGFRA-positive and also expressed POSTN, consistent with the telocyte-like population we identified.12 A second fibroblast population was described as a myofibroblast population positive for ACTA2, HHIP, and TAGLN.15 Nowicki-Osuch et al16 analyzed commonalities between esophageal and gastric intestinal metaplasia using scRNA-seq and observed 3 fibroblast populations. One major population showed high expression of PDGFRA and PDPN with POSTN, correlating with our findings of a telocyte-like population.12 The second major population was characterized by expression of ACTA2, MYL9, and ACTG2 with a transcriptional signature similar to myofibroblasts. By immunostaining, they also reported an expansion of POSTN-positive and SMA-positive fibroblasts in samples with intestinal metaplasia.35As reflected by these studies, single-cell analytical methods have augmented our knowledge of the heterogeneity and diversity of fibroblast populations in the stomach.12,13,14, 15, 16 Present studies reach a consensus on the existence of a major fibroblast population expressing PDGFRA that is expanded in areas with metaplasia in immediate proximity to epithelial cells (Table 1). This population might represent the major telocyte-like population in the stomach, with functional roles in the maintenance of progenitor cells in normal stomach and, most importantly, progression of metaplasia into dysplasia/cancer in transitioning zones.12 There is likely even greater heterogeneity within the PDGFRA-expressing fibroblast population, and true telocytes expressing FOXL1 may represent a subpopulation of this cell type. At the same time, multiple studies have noted the presence of myofibroblasts in normal and metaplastic tissues. Although these myofibroblasts identified by aSMA staining may be a source of RSPO3, our scRNA-seq data showed that inflammatory fibroblasts were the predominant source of RSPO3 in the human stomach. In addition, myofibroblasts generally do not show the same proximity to the metaplastic and dysplastic cell lineages as the telocyte-like populations.

Fibroblasts in Human Stomach Cancer

In almost all solid tumors, fibroblast-like cells are an important component of the tumor microenvironment.38, 39, 40 The term cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAF) refers to stromal cells that can promote progression of precancerous stages and promote tumorigenesis and tumor cell growth.41 Studies in different types of cancer have identified at least 2 major types designated as myofibroblast CAF or inflammatory CAF.42, 43, 44, 45 More recently, thanks to improvements in scRNA-seq and spatial transcriptomic technologies, the heterogeneity within CAF and their geographic diversity in different tumors are becoming more evident.46

In gastric cancer, little is known about the origin, specific regulation pathways, and heterogeneity of fibroblasts, in part because of limited mouse models of gastric cancer mimicking the carcinogenic cascade seen in human patients. Kumar et al17 found distinct tumor fibroblast populations in patient samples with gastric cancer. Notably, one population highly co-expressed INHBA and FAP, in comparison with fibroblasts from normal tissue, and were associated with poor prognosis. Further in vitro analysis demonstrated that INHBA is a positive regulator of FAP in gastric cancer fibroblasts. Another population strongly co-expressed both endothelial and fibroblast-related markers, suggesting expansion of pericytes. In our recent study,12 we observed that PDGFRAhi telocyte-like fibroblasts were significantly expanded and wrapped around epithelial-containing glands but in a more disorganized fashion compared with metaplastic glands. Furthermore, we observed frequent co-expression of PDGFRA and PDGFRB in the fibroblasts from these tissues. The myofibroblast population (ACTA2hi and PDGFRBlo) was also present but mostly located in submucosal areas away from the epithelial compartment. Moreover, some dysplastic/cancerous tissue samples presented a significant expansion of the pericyte population (ACTA2lo and PDGFRBhi).12 Sathe et al18 also performed scRNA-seq and detected tumor-specific myofibroblasts enriched for extracellular matrix–related transcripts and prominent expression of ACTA2 when compared with normal samples. These tumor-associated myofibroblasts also showed high expression of RSPO3 and EGR2, a gene known to influence fibrosis. Thus, multiple different fibroblast populations are expanded within the cancer-bearing milieu.

Table 1 summarizes the markers that characterize commonly identified subclasses in human stomach. These include a class of telocyte-like fibroblasts that express high levels of PDGFRA with low expression of ACTA2. A second class of inflammatory fibroblasts expresses FBLN2, FBLN1, and RSPO3. Myofibroblasts demonstrate high expression of ACTA2 and minimal expression of PDGFRA, whereas pericytes express high levels of PDGFRB with low but significant levels of ACTA2. Although not all of these groups were described in all of the studies, most studies support these 4 fibroblast subsets in both normal and pathologic human stomach (Figure 1A). A recent investigation examined fibroblasts with high or low expression Pdgfra (Pdgfrahi or Pdgfralo) in the mouse stomach.47 Pdgfrahi fibroblasts appear to be similar to the telocyte-like fibroblasts seen in human stomach. Moreover, they described Pdgfralo CD55+ fibroblasts located at the base of corpus glands showing higher expression of Grem1 and Rspo3. When we compare the results in mice with the human fibroblast scRNA-seq data from our studies, Pdgfralo CD55+ cells appear to correlate with inflammatory fibroblast populations in the human stomach. Thus, diverse fibroblast subpopulations are present in the mouse and human stomach in homeostatic conditions.

Conclusions and Cell Biological Questions That Remain

In the human stomach, fibroblast populations display extensive heterogeneity, which appears to be more pronounced during carcinogenesis. Nevertheless, representatives of fibroblast populations are present throughout the spectrum from normal to metaplasia to cancer-bearing mucosa. Alterations in fibroblasts align more with changes in the relative abundance of populations and more importantly their expression and secretion of regulators that can affect mucosal cell behaviors. Thus, it appears that a simple term CAF is not appropriate for evaluating the dynamic scenarios in play within the carcinogenic milieu. It would seem more logical to specify relationships of specific populations within the precancerous and cancerous milieu with promotion of carcinogenesis. This approach will also facilitate analysis of 2 critical processes within fibroblast populations: First, it is unclear how much plasticity exists within fibroblast subpopulations. In our examination of scRNA-seq data in the human stomach, we observed a connection between PDGFRA-expressing telocyte-like fibroblasts and FBLN2-expressing inflammatory fibroblasts12 (Figure 1A). Nevertheless, these populations were distinct from and without connection to myofibroblasts. These results support the concept that there is plasticity between the telocyte-like and inflammatory fibroblasts. In contrast, there is less support for plasticity between myofibroblasts and either telocyte-like or inflammatory fibroblasts. Further studies are clearly needed to assess the interconversion among fibroblast populations and the influence of epithelial cell lineages on this process.

Second, it remains unclear how individual populations of fibroblasts alter their expression patterns, especially for secreted factors that may strongly influence the behavior of epithelial cells. We determined that conditioned media from fibroblast culture isolated from both metaplasia and dysplasia-bearing mucosa induced dysplastic cell lineage transition in metaplastic cells.12 However, conditioned media from fibroblasts isolated from the normal stomach did not elicit these changes. Thus, fibroblasts derived from either metaplastic mucosa or dysplastic mucosa may secrete key factors that can strongly influence the carcinogenesis paradigm. How these factors are up-regulated and in which fibroblast populations they are expressed remain obscure.

Finally, fibroblast populations involved in carcinogenesis may be tissue specific. Whereas studies in pancreas and breast cancers have emphasized that myofibroblasts are the major driver of carcinogenesis,41,48 that is clearly not the case in the stomach. Some of this discordance could reflect the stage evaluated in these different studies. Fibroblast populations that promote metaplasia and dysplasia progression may differ from those that promote adenocarcinoma lineage survival and metastasis. The interaction of multiple fibroblast populations, eg, myofibroblasts, inflammatory fibroblasts, and telocytes, acting in concert may determine the ultimate influence of the stroma on epithelial cells. Again, more detailed characterization of fibroblasts participating at different points in the carcinogenesis cascade in different organs is needed to clarify common and tissue-specific mechanisms. In the future, definition of fibroblasts must rely on detailed expression analysis and multiple lineage markers correlated with geographical associations between fibroblast populations and epithelial lineages.

Acknowledgments

CRediT Authorship Contributions

Ela W. Contreras-Panta (Conceptualization: Equal; Writing – original draft: Lead)

Eunyoung Choi (Conceptualization: Equal; Funding acquisition: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Equal)

James R. Goldenring, MD, PhD (Conceptualization: Equal; Funding acquisition: Equal; Writing – original draft: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Lead)

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding James R. Goldenring was supported by grants from Department of Veterans Affairs Merit Review Award IBX000930, DODCA190172, and NIHR01 DK101332 and NCIR01 CA272687. Eunyoung Choi was supported by grants from NIHR37 CA244970, NCIR01 CA272687, and an AGA Research Foundation Funderburg Award (AGA2022-32-01).

References

- 1.Petersen C.P., Weis V.G., Nam K.T., et al. Macrophages promote progression of spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia following acute loss of parietal cells. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1727–1738. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petersen C.P., Meyer A.R., De Salvo C., et al. A signalling cascade of IL-33 to IL-13 regulates metaplasia in the mouse stomach. Gut. 2018;67:805–817. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meyer A.R., Engevik A.C., Madorsky T., et al. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells coordinate damage response in the stomach. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:2077–2091 e8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.08.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Busada J.T., Peterson K.N., Khadka S., et al. Glucocorticoids and androgens protect from gastric metaplasia by suppressing group 2 innate lymphoid cell activation. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:637–652. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.04.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldenring J.R., Mills J.C. Cellular plasticity, reprogramming, and regeneration: metaplasia in the stomach and beyond. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:415–430. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nam K.T., Lee H.-J., Sousa J.F., et al. Mature chief cells are cryptic progenitors for metaplasia in the stomach. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:2028–2037. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ilic M., Ilic I. Epidemiology of stomach cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28:1187–1203. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v28.i12.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Correa P. A human model of gastric carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 1988;48:3554–3560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonzalez C.A., Sanz-Anquela J.M., Companioni O., et al. Incomplete type of intestinal metaplasia has the highest risk to progress to gastric cancer: results of the Spanish follow-up multicenter study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:953–958. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi A.Y., Strate L.L., Fix M.C., et al. Association of gastric intestinal metaplasia and East Asian ethnicity with the risk of gastric adenocarcinoma in a U.S. population. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:1023–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee S., Jang B., Min J., et al. Upregulation of AQP5 defines spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia (SPEM) and progression to incomplete intestinal metaplasia. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepataol. 2022;13:199–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2021.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee S.H., Contreras Panta E.W., Gibbs D., et al. Apposition of fibroblasts with metaplastic gastric cells promotes dysplastic transition. Gastroenterology. 2023;165:374–390. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.04.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsubosaka A., Komura D., Kakiuchi M., et al. Stomach encyclopedia: combined single-cell and spatial transcriptomics reveal cell diversity and homeostatic regulation of human stomach. Cell Reports. 2023;42 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2023.113236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim J., Park C., Kim K.H., et al. Single-cell analysis of gastric pre-cancerous and cancer lesions reveals cell lineage diversity and intratumoral heterogeneity. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2022;6:9. doi: 10.1038/s41698-022-00251-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang K.K., Ma H., Chong R.H.H., et al. Spatiotemporal genomic profiling of intestinal metaplasia reveals clonal dynamics of gastric cancer progression. Cancer Cell. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nowicki-Osuch K., Zhuang L., Cheung T.S., et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing unifies developmental programs of esophageal and gastric intestinal metaplasia. Cancer Discov. 2023 doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-22-0824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar V., Ramnarayanan K., Sundar R., et al. Single-cell atlas of lineage states, tumor microenvironment, and subtype-specific expression programs in gastric cancer. Cancer Discov. 2022;12:670–691. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-0683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sathe A., Grimes S.M., Lau B.T., et al. Single-cell genomic characterization reveals the cellular reprogramming of the gastric tumor microenvironment. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:2640–2653. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-3231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang H.Y., Chi J.T., Dudoit S., et al. Diversity, topographic differentiation, and positional memory in human fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:12877–12882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162488599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Denton A.E., Roberts E.W., Fearon D.T. Stromal cells in the tumor microenvironment. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2018;1060:99–114. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-78127-3_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKee T.J., Perlman G., Morris M., et al. Extracellular matrix composition of connective tissues: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific Reports. 2019;9 doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46896-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Powell D.W., Pinchuk I.V., Saada J.I., et al. Mesenchymal cells of the intestinal lamina propria. Annu Rev Physiol. 2011;73:213–237. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goto N., Goto S., Imada S., et al. Lymphatics and fibroblasts support intestinal stem cells in homeostasis and injury. Cell Stem Cell. 2022;29:1246–1261 e6. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2022.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sigal M., Logan C.Y., Kapalczynska M., et al. Stromal R-spondin orchestrates gastric epithelial stem cells and gland homeostasis. Nature. 2017;548:451–455. doi: 10.1038/nature23642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pastula A., Middelhoff M., Brandtner A., et al. Three-dimensional gastrointestinal organoid culture in combination with nerves or fibroblasts: a method to characterize the gastrointestinal stem cell niche. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/3710836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim B.M., Buchner G., Miletich I., et al. The stomach mesenchymal transcription factor Barx1 specifies gastric epithelial identity through inhibition of transient Wnt signaling. Dev Cell. 2005;8:611–622. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldenring J.R. Pyloric metaplasia, pseudopyloric metaplasia, ulcer-associated cell lineage and spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia: reparative lineages in the gastrointestinal mucosa. J Pathol. 2018;245:132–137. doi: 10.1002/path.5066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmidt P.H., Lee J.R., Joshi V., et al. Identification of a metaplastic cell lineage associated with human gastric adenocarcinoma. Lab Invest. 1999;79:639–646. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi E., Hendley A.M., Bailey J.M., et al. Expression of activated Ras in gastric chief cells of mice leads to the full spectrum of metaplastic lineage transitions. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:918–930. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.11.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quante M., Tu S.P., Tomita H., et al. Bone marrow-derived myofibroblasts contribute to the mesenchymal stem cell niche and promote tumor growth. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:257–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shibata W., Ariyama H., Westphalen C.B., et al. Stromal cell-derived factor-1 overexpression induces gastric dysplasia through expansion of stromal myofibroblasts and epithelial progenitors. Gut. 2013;62:192–200. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mutoh H., Sakurai S., Satoh K., et al. Pericryptal fibroblast sheath in intestinal metaplasia and gastric carcinoma. Gut. 2005;54:33–39. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.042770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu L-y, Sun Y., Li Z-w, et al. Pericryptal fibroblast sheath in intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia and carcinoma of the stomach. Chinese Journal of Cancer Research. 2009;21:290–294. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kondo A., Kaestner K.H. Development; 2019. Emerging diverse roles of telocytes; p. 146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shoshkes-Carmel M., Wang Y.J., Wangensteen K.J., et al. Subepithelial telocytes are an important source of Wnts that supports intestinal crypts. Nature. 2018;557:242–246. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0084-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCarthy N., Manieri E., Storm E.E., et al. Distinct mesenchymal cell populations generate the essential intestinal BMP signaling gradient. Cell Stem Cell. 2020;26:391–402 e5. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2020.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aoki R., Shoshkes-Carmel M., Gao N., et al. Foxl1-expressing mesenchymal cells constitute the intestinal stem cell niche. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;2:175–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Plikus M.V., Wang X., Sinha S., et al. Fibroblasts: origins, definitions, and functions in health and disease. Cell. 2021;184:3852–3872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamamoto Y., Kasashima H., Fukui Y., et al. The heterogeneity of cancer-associated fibroblast subpopulations: their origins, biomarkers, and roles in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Science. 2023;114:16–24. doi: 10.1111/cas.15609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chhabra Y., Weeraratna A.T. Fibroblasts in cancer: unity in heterogeneity. Cell. 2023;186:1580–1609. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Biffi G., Tuveson D.A. Diversity and biology of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Physiol Rev. 2021;101:147–176. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00048.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Elyada E., Bolisetty M., Laise P., et al. Cross-species single-cell analysis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma reveals antigen-presenting cancer-associated fibroblasts. Cancer Discov. 2019;9:1102–1123. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ohlund D., Handly-Santana A., Biffi G., et al. Distinct populations of inflammatory fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in pancreatic cancer. J Exp Med. 2017;214:579–596. doi: 10.1084/jem.20162024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bartoschek M., Oskolkov N., Bocci M., et al. Spatially and functionally distinct subclasses of breast cancer-associated fibroblasts revealed by single cell RNA sequencing. Nature Communications. 2018;9:5150. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07582-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Affo S., Nair A., Brundu F., et al. Promotion of cholangiocarcinoma growth by diverse cancer-associated fibroblast subpopulations. Cancer Cell. 2021;39:866–882 e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Waise S., Parker R., Rose-Zerilli M.J.J., et al. An optimised tissue disaggregation and data processing pipeline for characterising fibroblast phenotypes using single-cell RNA sequencing. Scientific Reports. 2019;9:9580. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-45842-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manieri E., Tie G., Malagola E., et al. Role of PDGFRA(+) cells and a CD55(+) PDGFRA(Lo) fraction in the gastric mesenchymal niche. Nat Commun. 2023;14:7978. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-43619-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dumont N., Liu B., Defilippis R.A., et al. Breast fibroblasts modulate early dissemination, tumorigenesis, and metastasis through alteration of extracellular matrix characteristics. Neoplasia. 2013;15:249–262. doi: 10.1593/neo.121950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]