Abstract

The gene functions, transcriptional regulation, and genome replication of human papillomaviruses (HPVs) have been extensively studied. Thus far, however, there has been little research on the organization of HPV genomes in the nuclei of infected cells. As a first step to understand how chromatin and suprachromatin structures may modulate the life cycles of these viruses, we have identified and mapped interactions of HPV DNAs with the nuclear matrix. The endogenous genomes of HPV type 16 (HPV-16) which are present in SiHa, HPKI, and HPKII cells, adhere in vivo to the nuclear matrixes of these cell lines. A tight association with the nuclear matrix in vivo may be common to all genital HPV types, as the genomes of HPV-11, HPV-16, HPV-18, and HPV-33 showed high affinity in vitro to preparations of the nuclear matrix of C33A cells, as did the well-known nuclear matrix attachment region (MAR) of the cellular beta interferon gene. Affinity to the nuclear matrix is not evenly spread over the HPV-16 genome. Five genomic segments have strong MAR properties, while the other parts of the genome have low or no affinity. Some of the five MARs correlate with known cis-responsive elements: a strong MAR lies in the 5′ segment of the long control region (LCR), and another one lies in the E6 gene, flanking the HPV enhancer, the replication origin, and the E6 promoter. The strongest MAR coincides with the E5 gene and the early-late intergenic region. Weak MAR activity is present in the E1 and E2 genes and in the 3′ part of L2. The in vitro map of MAR activity appears to reflect MAR properties in vivo, as we found for two selected fragments with and without MAR activity. As is typical for many MARs, the two segments with highest affinity, namely, the 5′ LCR and the early-late intergenic region, have an extraordinarily high A-T content (up to 85%). It is likely that these MARs have specific functions in the viral life cycle, as MARs predicted by nucleotide sequence analysis, patterns of A-T content, transcription factor YY1 binding sites, and likely topoisomerase II cleavage sites are conserved in similar positions throughout all genital HPVs.

The structure and expression of human papillomavirus (HPV) genes have been extensively researched, largely due to the great interest in the causal association of these viruses with benign and malignant neoplasia (for overviews, see references 27 and 28). Although the replication mechanisms, cis-responsive elements, and splicing of transcripts have been studied in great detail (for reviews, see references 4, 43, and 46), some important biological and medical phenomena of the HPV life cycle remain to be elucidated. For example, it is still poorly understood how HPV promoters are differentially regulated, how transcripts are differentially spliced, or how HPV genomes achieve copy number control. It may be possible that some of these phenomena are modulated by the interaction of HPV genomes with histones and other structural proteins of the nucleus. As only a few efforts have been made to understand how HPV genomes are organized in the infected cell, we undertook this study of the interaction of HPV genomes with the nuclear matrix.

In the eukaryotic nucleus, DNA and histone proteins interact to form nucleosomes, which are the primary structural units of chromatin. Light and electron microscope studies have revealed additional fibrogranular structures in the nucleus that are comprised of components other than those that make up chromatin (8). With the electron microscope, these have been identified as part of the chromosomal topology or, under other conditions, as a fibrillar network extending throughout the nucleus with little resemblance to chromosomal topology. These nonchromatin nuclear components have been termed the nuclear matrix or nuclear scaffold. In recent years, the nuclear matrix has attracted increasing interest, as it is now clear that most enzymatic machineries that handle DNA and RNA associate with insoluble nuclear structures and tend to occur in domains rather than diffusing freely in the nucleus (for a review, see reference 59).

The structure and function of the nuclear matrix are not understood in great detail at the molecular level. The nuclear matrix is operationally defined as the insoluble fibrogranular material remaining after the treatment of nuclei with DNase and extraction of histones and most of the DNA. Different investigators use different isolation procedures for the preparation of the nuclear matrix (7, 12, 22, 29, 40). Although these preparations can result in slight variations of protein composition, it is generally thought that all procedures identify by and large the same structures as seen in electron micrographs, which are responsible for the compartmentalization of the nucleus. The nuclear matrix contains abundant and well-characterized structural proteins, such as lamins and ribonucleoproteins (18, 41, 49), in addition to a large number of poorly characterized, low-abundance proteins. There is evidence that some of these proteins, such as DNA and RNA polymerases (8), transcription factors (60), topoisomerase II (23), and various splicing factors (35), fulfill more than structural roles. From this, one may infer that the nuclear matrix may topologically confine replication, transcription, splicing, and mRNA export and that the nuclear functions that are most often studied in solution occur, in vivo, in association with larger nuclear structures.

Cellular DNA has been found to be tightly associated with the nuclear matrix through specific DNA elements which have been termed matrix attachment regions (MARs). Similar elements occur in DNA viruses (14, 30, 47, 52). MARs may be up to a few hundred nucleotides in length but do not demonstrate strictly conserved sequence motifs, although many contain A-T-rich stretches and clusters of topoisomerase II cleavage sites (23). MARs can occur close to promoters and enhancers and can influence these cis-responsive elements (9, 10). MARs have also been found close to origins of replication, in introns (12, 13, 32), and form part of the boundaries of actively transcribed chromatin (12, 13, 40, 45). From these observations, one could speculate that different MARs may have different functions and may serve to bring various cis-responsive elements close to matrix-bound protein assemblies.

Studies of cellular genes suggest that the nuclear matrix might regulate some of the processes in the HPV life cycle that are not yet understood. With this consideration in mind, we searched for MARs in HPV type 16 (HPV-16). Some of the MARs that were mapped lie close to important cis-responsive elements of HPV-16, namely, the epithelial cell-specific enhancer, the E6 promoter, the replication origin, and the early-late intergenic region. Sequence studies suggest that these MARs are conserved among HPV types with otherwise little sequence similarity, suggesting an important and conserved function for each of these MARs in the life cycle of papillomaviruses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines.

The cell lines C33A, which is free of HPV genomes, and SiHa and CaSki, which carry endogenous HPV-16 genomes, are derived from cervical carcinomas and are widely used in HPV research (5, 17). The cell lines HPKI and HPKII were derived by stable transfection of HPV-16 DNA into foreskin epithelial cells (48) and were supplied for this study by M. Dürst.

Plasmid constructs.

pHPV16 contains the complete HPV-16 genome in the form of a BamHI insert in pSP65. Subclones are summarized in Fig. 1 and were obtained as follows. pHPV16-L1-E7 contains a segment between the genomic positions (nucleotides [nt]) 5384 and 884 after deletion of a 4,499-bp Asp718 fragment. The deleted 4,499-bp Asp718 fragment was cut with Bsp120I into two fragments with sizes of 3,650 and 849 bp, which were cloned into pGEM7zf(+) (Promega) to yield pHPV16-E1-L2 (nt 885 to 4530) and pHPV16-L2 (nt 4531 to 5383). Subcloning of segments within and close to the long control region (LCR) was performed by PCR, and the PCR products were inserted into the SrfI site of pCR-ScriptSK(+) (Stratagene). To obtain pHPV16-3′L1 (nt 6862 to 7151), we used the primers U170 (CAACATCCCCCAGGAGGC) and L171 (CGTTAACAACTGCTTACGTTTTTTG); for pHPV16-5′LCR (nt 7150 to 7450), we used primers U172 (CGTCGGCTGTAAGTATTGT) and L173 (CGAATTCGGCTAAAGCTAC); for pHPV16-enh (nt 7451 to 7850), we used primers U175 (CGGCCTATTTGTAGCAACAACC) and L176 (CCCATGTGCAGTTTTACAAATGAA); and for pHPV16-oriprom (nt 7851 to 104), we used primers U177 (GTAAAGCTGCTGCCGGCTGTGTGCAAA) and L178 (CCTGTGGGTCCT GAAGCTTTGCAGTTCTCTT). pHPV16-E6 contains the E6 gene in the plasmid pBluescript SK(+) (Stratagene) flanked by HindIII and PstI sites. Three other plasmids contain PCR fragments of HPV-16 DNA flanking the origin of replication inserted into the SrfI site of pCR-ScriptSK(+): pHPV16-oriprom-x contains a 259-bp fragment (nt 7746 to 104) obtained with the primers U193 (AATTGCGGATCCGGCATAAGGTTTAAACTTCTAA) and L178, pHPV16-oriprom-y contains a 352-bp fragment (nt 7851 to 274) obtained with the primers U177 and L194 (GGATCCCCATCTCTATATACTATGCATAAAT), and pHPV16-oriprom-z contains a 487-bp fragment (nt 7746 to 274) obtained with the primers U193 and L194. The constructs pHPV16-5′LCRmut1, pHPV16-5′LCRmut2, and pHPV16-5′LCRmut3 carry the pHPV-16-5′LCR sequence (nt 7150 to 7450) mutated with the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) with the primers shown in Fig. 8F. pHPV16-E2 contains a 710-bp MunI-SspBI restriction fragment (nt 2971 to 3680) of HPV-16 in plasmid pGEMTEZ (Promega). pHPV16-E5, which contains a 802-bp DdeI restriction fragment (nt 3536 to 4337), was constructed similarly. The control plasmids pCL and pGEM-xdelta contain an 854-bp EcoRI fragment of the human beta interferon MAR in pTZ-18R (39) and a 1,119-bp EcoRI-ClaI fragment of mouse mitochondrial DNA (36), respectively.

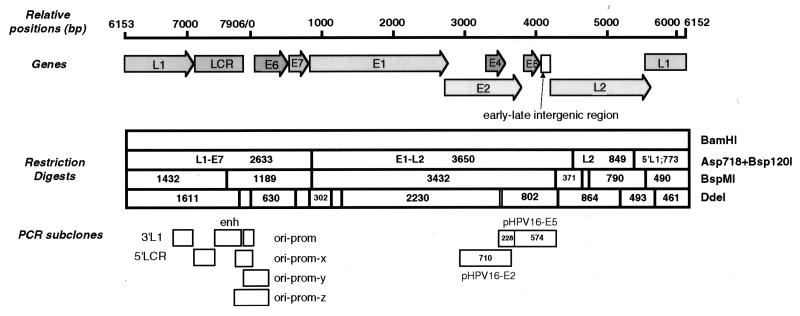

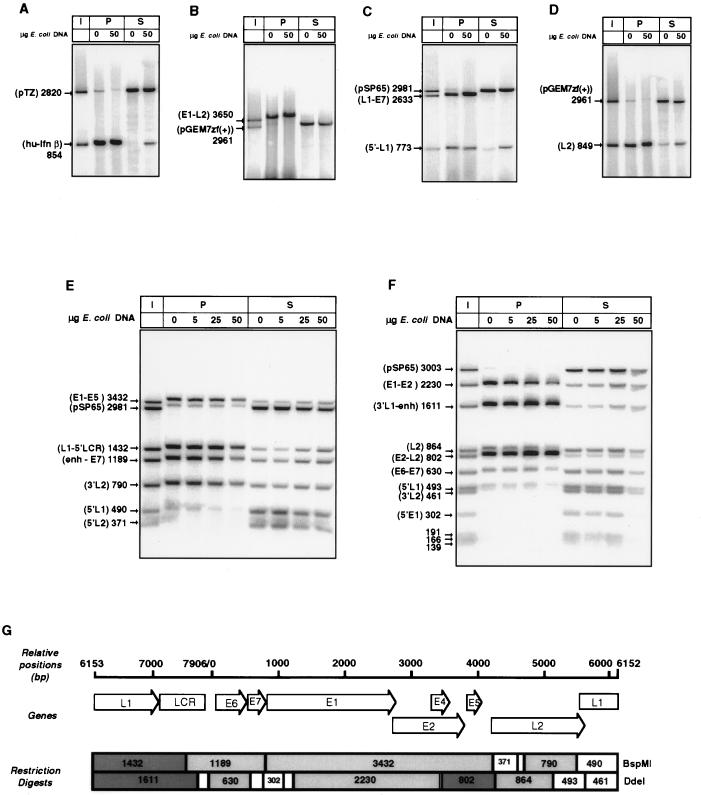

FIG. 1.

Map of the HPV-16 genome, with genes, restriction fragments, and PCR-generated subclones that were examined for attachment to preparations of the nuclear matrix. The HPV-16 genome, with a size of 7,906 bp, is represented after linearization at a single BamHI site at position 6152 in the L1 gene. The numbers in the boxes represent the sizes of the fragments in base pairs. Fragments too small to be analyzed have been omitted.

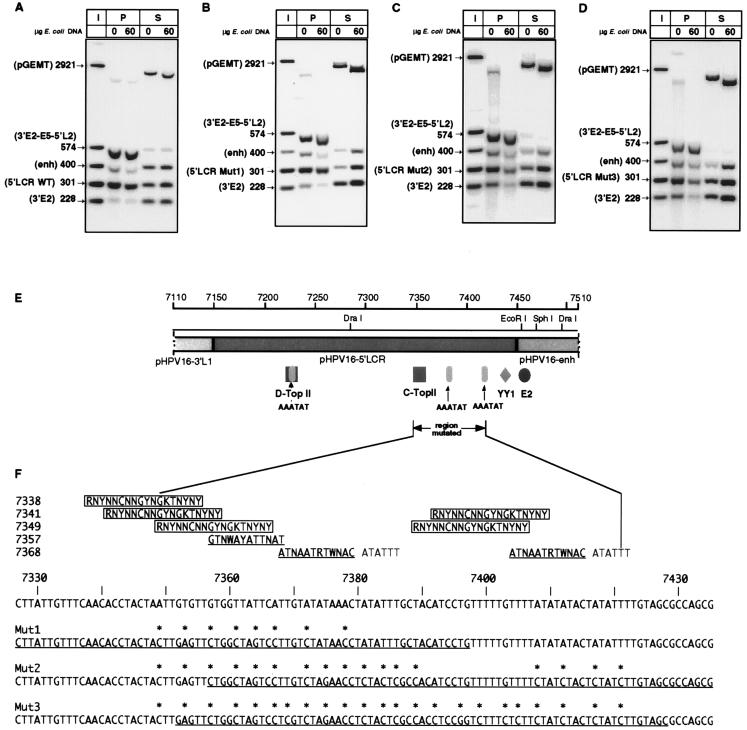

FIG. 8.

Multiple point mutations in the 5′ LCR reduce MAR activity in vitro. (A) In vitro MAR activity of the 301-bp 5′-LCR fragment with the HPV-16 wild-type (WT) sequence. (B to D) Activity with this sequence mutated in 8 (Mut1), 17 (Mut2), and 23 positions (Mut3), respectively. With changes of 2.7 to 8% of the sequence of the 5′-LCR segment, densitometric analysis with a PhosphorImager showed MAR activity reduced by 50, 70, and 78%, respectively. The positive control is a 574-bp fragment including the E5 MAR (positions 3764 to 4337); controls for weak MAR activity are a 400-bp enhancer (enh) segment and a 228-bp segment from the E2 gene. I, input; P, matrix-bound DNA; S, DNA fraction in the supernatant. (E) Position of the mutated sequence within the 5′ LCR of HPV-16, showing Drosophila (D-TopII) and chicken (C-TopII) topoisomerase II sequences with only one mismatch as well as a highly conserved YY1 site and an E2 binding site between the 5′ LCR and the enhancer segment. (F) Multiple point mutations were chosen to alter typical sequence elements of MARs: (i) GT dinucleotides, (ii) chicken topoisomerase II motifs with two or fewer mismatches (56) (boxed sequences), (iii) Drosophila topoisomerase II motifs with two or fewer mismatches (51) (underlined sequences in the upper part), and (iv) the sequence ATATTT (15, 55). Underlined sequences in the lower part indicate the oligonucleotides used for mutagenesis.

Preparation of DNA fragments for nuclear matrix binding assays.

DNA fragments were prepared for binding assays by cutting the HPV-16 genome into fragments of different sizes which could be distinguished from one another in agarose gel electrophoresis. Alternatively, plasmids containing segments of the HPV-16 DNA or control DNA were first digested in aliquots of 10 μg and gel purified following electrophoresis in low-melting-point agarose. DNA fragments in gel slices were purified by digestion with 1 U of GELase (Epicentre Technologies) per 200 mg of 1% agarose at 42°C for 3 h. These DNA fragments and plasmid DNA from only one of the constructs were then mixed together in stoichiometrically equivalent proportions. The mixed DNA fragments were subsequently treated with calf intestinal phosphatase followed by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. Five hundred nanograms of these mixed DNA fragments was radioactively labelled with [γ-32P]ATP by using polynucleotide kinase and purified with NICK-spin columns (Pharmacia).

Preparation of the nuclear matrix and performance of DNA-nuclear matrix binding assays.

The nuclear matrix was isolated as described by Mirkovitch et al. (40) and modified by the groups of Bode and Shenk (9, 39, 52). The technique is based on low-salt extraction of nuclei in the presence of lithium 3,5-diiodosalicylate (LIS). Confluent C33A cells (approximately 2 × 107 cells) were washed twice with isolation buffer (3.75 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 0.05 mM spermine, 0.125 mM spermidine, 0.5 mM EDTA [pH 7.4], 1% [vol/vol] thiodiglycol, 20 mM KCl; 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF]) and scraped into 10 ml of isolation buffer containing, in addition, 0.1% digitonin. Nuclei were released by 20 strokes in a Dounce homogenizer and pelleted by centrifugation. The nuclear pellet was resuspended in 10 ml of isolation buffer with 0.1% digitonin, carefully resuspended in a Dounce homogenizer, and pelleted again by centrifugation. The nuclear pellet was resuspended in 150 μl of freshly prepared nuclear buffer (5 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 0.05 mM spermine, 0.125 mM spermidine, 20 mM KCl, 1% [vol/vol] thiodiglycol, 0.1% digitonin, 0.2 mM PMSF, 1% aprotinin) and incubated at 37°C for 20 min. Three milliliters of LIS buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 100 mM lithium acetate, 1 mM Na-EDTA, 0.1% digitonin, 25 mM LIS [Sigma]) was added slowly with gentle mixing to the heat-treated nuclear pellet. After 5 min, the suspension was centrifuged at 2,400 × g for 5 min at 4°C, and the pellet was resuspended in 10 ml of sterile digestion buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 0.05 mM spermine, 0.125 mM spermidine, 20 mM KCl, 70 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1% digitonin, 1% aprotinin, 0.1 mM PMSF), gently rocked for 20 min at room temperature, and centrifuged as before. This procedure was repeated twice. The nuclear matrix pellet was resuspended in 600 μl of digestion buffer, supplemented with restriction enzyme BamHI or EcoRI to a final concentration of 0.4 U/μl, and incubated in a 37°C shaking incubator for 3 h to fragment the high-molecular-weight chromosomal DNA. For attachment between presumed MARs and the nuclear matrix, the preparation was divided into four aliquots, mixed with end-labelled test DNA (about 3 to 5 ng containing about 50,000 cpm of 32P) in the presence or absence of sonicated genomic Escherichia coli competitor DNA (5 to 60 μg), and incubated at 37°C overnight.

Centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 45 min at 4°C separated this reaction mixture into nuclear matrix pellets and supernatant. The pellets were washed twice in 500 μl of digestion buffer and centrifuged for 30 min. A 100-μl aliquot of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5)–0.1 M EDTA–1% sodium dodecyl sulfate and 10 μg of salmon sperm carrier DNA were added to each tube of supernatant and pellet. After 100 μg of proteinase K was added to the supernatant and 200 μg of proteinase K was added to the pellet, the tubes were heated to 55°C for 3 and 18 h, respectively. The protein was extracted from these mixtures with phenol-chloroform, and the DNA was precipitated with 600 μl of 0.6 M LiCl in ethanol.

DNA was pelleted by centrifugation, washed twice with 70% ethanol, and dried. The DNA pellets were resuspended in 60 μl of Tris-EDTA buffer, and the radioactivity was determined on a liquid scintillation counter. Approximately equal fractions of DNA from the precipitate and the supernatant were loaded on an agarose gel and separated by electrophoresis. Approximately 15% of the total input DNA was loaded into another lane as a reference in quantitative calculations. After electrophoresis, the gel was dried onto a nylon membrane in a heated gel drier and autoradiographed by exposure to Hyperfilm (Amersham). Following exposure of the gel to a PhosphorImager screen, ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics) was used to quantify the amount of DNA represented by each band. To determine the relative binding affinities of different DNA fragments, the intensity of each band of the pellet or supernatant fraction was quantitated with reference to the respective band in the input lane.

Association of HPV-16 DNA in vivo.

Nuclear matrices of SiHa, HPKI, and HPKII cells (48) were prepared as described above and digested with BamHI, HincII, or PstI. Matrix-bound and supernatant DNAs were separated, and approximately 100 pg of each was amplified through 15 cycles of PCR with primers amplifying HPV-16 DNA between nt 7010 and 110. The reaction products were separated on agarose gels, blotted onto nylon membranes, and hybridized with a radioactively labelled PstI fragment of the HPV-16 DNA (nt 7010 to 879). For the study of the behavior of a MAR in vivo, nuclear matrix prepared from CaSki cells as described above was digested with DdeI, EcoRI, and PstI. The MAR of the E5 gene and the early-late intergenic region was included in an 802-bp DdeI fragment between genomic positions 3535 and 4337, which was further shortened by a PstI cut at position 3697 to yield a fragment of 640 bp. A 309-bp segment from the enhancer without MAR activity was flanked by a DdeI site at position 7764 and an EcoRI site at position 7456. After processing of the nuclear matrix as described above, these fragments were probed with radioactively labelled fragments (positions 3535 to 4337 and 7450 to 7850, respectively).

RESULTS

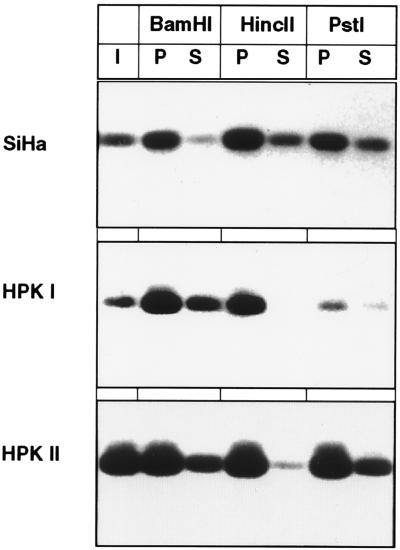

The HPV-16 genome is associated with the nuclear matrix in vivo.

The association of cellular and viral DNAs with the nuclear matrix is a prerequisite for the control of important biological tasks, such as transcription and DNA replication. It has not thus far been reported whether any HPV genome contains MARs, elements that permit specific attachment to the nuclear matrix. As there are technical limitations to the use of cell lines with stably replicating episomal HPV genomes, we decided to study the three cell lines SiHa, HPKI, and HPKII for association of their endogenous, intrachromosomal HPV-16 genomes to the nuclear matrix. Figure 2 shows that after separation of the nuclear matrix from soluble fractions of the nuclei, more HPV-16 DNA can be amplified by PCR from the nuclear matrix fractions than from the supernatant fractions. The stronger signal obtained with HPKII cells probably stems from the fact that these harbor about 10 copies of HPV-16 DNA, as opposed to one copy in SiHa and HPKI cells. We conclude that in vivo, at least in case of these three cell lines with the viral DNA being integrated into the cellular DNA, HPV-16 genomes preferentially associate with the nuclear matrix.

FIG. 2.

Association of the HPV-16 genome with the nuclear matrix of SiHa, HPKI, and HPKII cells in vivo. I, input; P, matrix-bound DNA fraction; S, DNA fraction in the supernatant.

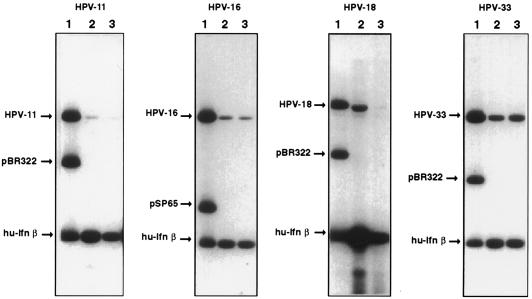

The genomes of four genital HPV types specifically bind in vitro to nuclear matrix.

It is well established that DNA elements that act as MARs in vivo can be identified, mapped, and further characterized in vitro by their affinity to nuclear matrix preparations. To examine whether the attachment of HPV-16 DNA to the nuclear matrix shown in vivo can also be observed in vitro and whether similar behavior is shown by other papillomaviruses, we prepared nuclear matrix from C33A, a cell line derived from an HPV-free cervical cancer, and incubated it with radioactively labelled total genomic DNAs from HPV-11, HPV-16, HPV-18, and HPV-33. As a positive control, we used the well-characterized MAR of the human beta interferon gene, while the bacterial cloning vector liberated by restriction digestion served as an internal negative control. Figure 3 shows that the genomes of HPV-16 and HPV-33 bind strongly to the nuclear matrix in the presence of a large excess of E. coli competitor DNA. Also, HPV-11 and HPV-18 show affinity to the nuclear matrix, although in this experiment the affinity was somewhat weaker than those of the beta interferon MAR and the other two viruses. In this and all other MAR detection experiments described in this paper, the presence of 5 to 100 μg of competitor DNA amounts to an approximate DNA mass excess of 10,000- to 100,000-fold over the HPV fragments under investigation. We conclude from Fig. 3 that HPV genomes have an affinity for binding to the nuclear matrix that is similar to that of the beta interferon MAR, and this property is distinct from that of prokaryotic DNA.

FIG. 3.

Association of the HPV-11, HPV-16, HPV-18, and HPV-33 genomes and the insert of the beta interferon (hu-Ifn β) clone MAR with the nuclear matrix of C33A cells in vitro. Lanes 1, input DNA; lanes 2 and 3, competition with 50- and 100-μg excesses of E. coli DNA, respectively. While the prokaryotic vector is efficiently competed from binding to the nuclear matrix at a low concentration of competitor, HPV-16 and HPV-33 show MAR activity like that of the strong beta interferon MAR. HPV-11 and HPV-18 have MAR affinity but are competed at the highest concentration of the competitor.

The HPV-16 genome contains specific MARs.

To address whether MAR activity is evenly spread over the HPV-16 genome or restricted to particular segments, we cleaved the HPV-16 genome with BamHI, Asp718, and Bsp120I into four fragments with sizes of 3650, 2633, 849, and 773 bp (Fig. 1) and examined their interactions with nuclear matrix extracts of C33A cells. The outcome of this experiment is shown in Fig. 4A to D. This figure (and the analyses in the subsequent figures) shows plasmid and potential MAR restriction fragments (i) in the input ratios (lanes I), (ii) as binding to the nuclear matrix without competitor (lanes P, 0) and with a large excess of competitor (lanes P, 50), and (iii) as remaining in the unbound supernatant in the absence of competitor (lanes S, 0) and in the presence of competitor (lane S, 50).

FIG. 4.

MAR activity in vitro of subgenomic fragments of HPV-16 DNA. (A) Comparison of a bacterial plasmid (pEZ) without MAR activity with the MAR of the human beta interferon (hu-Ifn β) gene. (B to D) MAR activity resides in each of four large restriction fragments (cleavage by BamHI and Asp718) encompassing the whole HPV-16 genome. (E and F) Refined mapping of MAR activity of BspMI (E) and DdeI (F) restriction fragments of BamHI-digested HPV-16 DNA shows highly dissimilar MAR activity. (G) Map of restriction fragments with strong and weak affinities to the nuclear matrix (dark and light shading, respectively). I, input; P, matrix-bound DNA fraction; S, DNA fraction in the supernatant; enh, enhancer. In this and all subsequent figures, homologous bands in the P and S lanes occasionally run slower or faster than the input DNA, as it was difficult to remove completely all salt that remained from the MAR preparation.

Surprisingly, each of the four subclones showed affinity to the nuclear matrix, similar to the positive control (Fig. 4A). As expected, no affinity was observed with the bacterial cloning vectors.

To determine whether small fragments of the HPV-16 genome might show differential affinity to the nuclear matrix, we digested HPV-16 DNA with BamHI and either BspMI or DdeI, which resulted in 7 and 12 genomic fragments, respectively. From Fig. 4E it is apparent that MAR activity is spread unevenly over the HPV-16 genome. Densitometric analysis (data not shown) points to the 1,432-bp fragment covering the end of L1 and the 5′ LCR as the genomic segment with strongest MAR activity, followed by three other fragments with sizes of 3,432, 1,189, and 790 bp, which have 10 to 30% less affinity. From Fig. 4F, which has the best resolution of different genomic segments, it is clear that high MAR activity resides in two fragments. One, with a size of 1,611 bp, includes the end of L1 and the LCR; the other, with a size of 802 bp, includes E5 and the early-late intergenic region. Three fragments, with sizes of 2,230, 864, and 630 bp, have 70 to 90% weaker affinity than the 802-bp fragment. These fragments include E1-E2, the 3′ end of L2, and most of E6, respectively.

These observations are summarized in Fig. 4G. The MAR activity of the E6 gene is not very pronounced in Fig. 4E and F but was confirmed on reexamination (see below and Fig. 5A). The absence of MAR activity in very small fragments is difficult to interpret, as MAR activity may be lost as a result of decreasing fragment size rather than the absence being due to sequence properties. Combining the data of Fig. 4, we concluded that two larger genomic segments of HPV-16, which are centered on (i) the 5′ LCR and (ii) the E5 gene and the early-late intergenic region, have high MAR activity. The fairly large sizes of these fragments required a more detailed mapping of MAR activity.

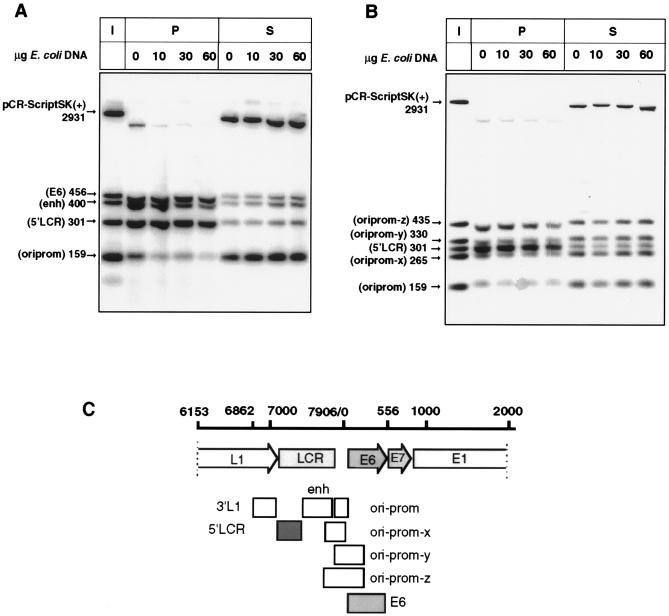

FIG. 5.

(A) A 5′ segment of the LCR and the E6 gene bind strongly in vitro to the nuclear matrix of C33A cells, while there is little binding of the epithelium-specific enhancer, the replication origin, and the E6-E7 promoter. Also, a 3′ segment of the L1 gene showed no MAR behavior whatsoever (58). (B) The 301-bp fragment with the 5′ LCR has higher MAR affinity than four larger and smaller fragments, including the E6 promoter (prom), the replication origin (ori), 3′ parts of the enhancer (enh), and 5′ parts of the E6 gene. I, input; P, matrix-bound DNA fraction; S, DNA fraction in the supernatant. (C) Locations and MAR affinities of fragments tested in these experiments. Each box identifies one of the tested fragments; the two shaded boxes indicate the only fragments with MAR activity.

The enhancer, promoter, and origin of replication of HPV-16 are flanked by two strong MARs but do not possess intrinsic MAR activity.

The identification of MAR activity in the HPV-16 LCR and its flanking regions is intriguing, as MARs are frequently linked to enhancer, promoter, and replication origins, and these three functional elements of HPV-16, namely, the epithelial cell-specific enhancer, the E6 promoter, and the viral replication origin, are positioned in the HPV-16 LCR. Figure 5A shows the detailed mapping of MAR activity in this genomic region. By PCR cloning, we subdivided into five segments a region of 1,604 bp between genomic positions 6862 and 566, which includes and flanks the LCR. These fragments encode (i) the 3′ part of the L1 gene, (ii) a 5′ segment of the LCR stretching from L1 to a single E2 binding site 300 bp downstream of L1, (iii) a segment further downstream containing the HPV-16 epithelium-specific enhancer, (iv) a segment containing the replication origin and the E6-E7 promoter, and (v) a 456-bp segment containing the E6 gene. Figure 5A indicates that strong MAR activity resides in the 5′ segment of the LCR and that nearly equivalent MAR activity resides in the E6 gene. In contrast, the enhancer itself shows weak affinity, and the segment with the replication origin and the promoter shows no MAR activity at all. The 3′ segment of the L1 gene showed no MAR behavior (data not shown). We conclude from this that the three important cis-responsive elements of the LCR are flanked by two strong MARs but are not themselves directly attached to the nuclear matrix. As the genetic properties of this part of the HPV-16 genome required cloning of these five elements on DNA fragments of various sizes, we included a control to measure whether size alone might contribute to MAR activity. Figure 5B compares the 301-bp 5′ LCR with four smaller and larger fragments. Each of these fragments, which are depicted in Fig. 5C, contains the E6 promoter, the replication origin, and a portion of the enhancer upstream of the replication origin or the 5′ part of the E6 gene. It is apparent that these four fragments have only weak MAR affinity, if any, although their sizes differ by about 50% above and below that with the 5′ LCR-MAR.

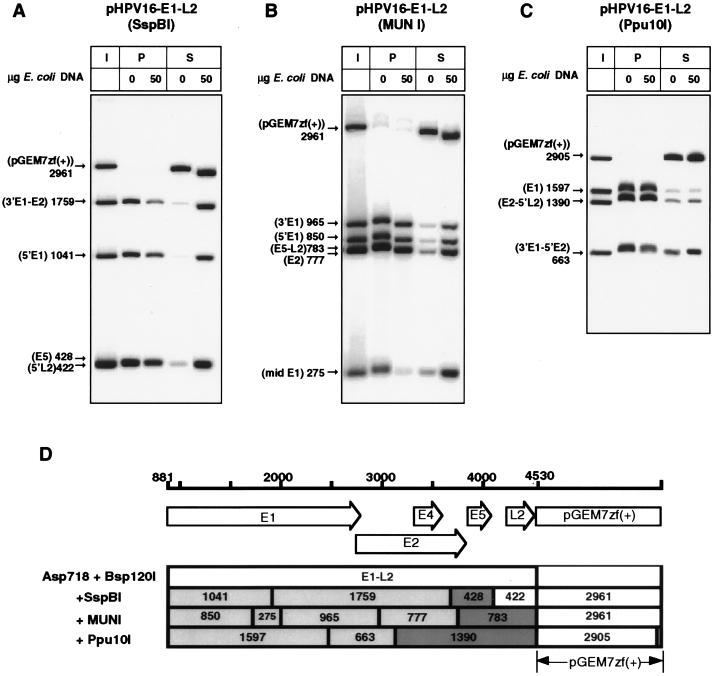

The E5 gene and the early-late intergenic region contain the strongest MAR of HPV-16, which is contiguous with weak MARs in E2 and E1 gene sequences.

From Fig. 4F it is apparent that an 802-bp DdeI fragment had the highest affinity to the nuclear matrix preparations. This fragment is between nucleotide positions 3536 and 4337 and includes the 3′ end of E2, the E5 gene, and the early-late intergenic region. Figure 6 shows a refined analysis of this genomic region. The E5 gene is included in a 3,650-bp Asp718-Bsp120 fragment, which also contains the E1 and E2 genes and the 5′ terminus of L2. After digestion with either SspB1, MunI, or Ppu10I, this region can be subdivided into four, five, or three smaller fragments, respectively. As documented in Fig. 6A to C and summarized in Fig. 6D, the strongest MAR activity can be seen in fragments including the E5 gene and a small part of the 3′ terminus of E2. Critical information can be gathered from a 428-bp SspB1 fragment which includes sequences between positions 3681 and 4108, including all of E5. As judged by densitometric analyses with a PhosphorImager, all fragments 5′ of E5 with E1 and E2 gene sequences have relatively weaker MAR activity. The unsatisfactory analysis of the 777-bp fragment, which was poorly separated from a 783-bp fragment, was later clarified by inclusion in another experiment (see Fig. 9). In Fig. 6A, a 422-bp SspB1 fragment with the 5′ end of L2, also including part of the early-late intergenic region, is not well resolved from the 428-bp fragment with strong MAR activity. From the comparison of the positions of the respective bands in the precipitate and the supernatant fractions, it seems that the 422-bp fragment is very poorly bound. This would place the 3′ border of this MAR in the intergenic region, with an extremely A-T-rich segment in the middle of this region apparently not contributing much to the MAR property.

FIG. 6.

MAR activity of restriction fragments surrounding, including, and flanking the HPV-16 E5 gene as shown in vitro with a nuclear matrix preparation of C33A cells. As shown in panel D, E5 is included in a 3,650-bp Asp718-Bsp120 fragment, which can be further subdivided by SspB1, MunI, or Ppu10I into four, five, and three smaller fragments, respectively. Panels A to C document strong MAR activity in fragments including the E5 gene and a small part of the 3′ terminus of E2. Particularly high activity is shown by a 428-bp SspB1 fragment which includes, between positions 3681 and 4108, all of E5. All fragments 5′ of E5 with E1 and E2 gene sequences have weak MAR activity. I, input; P, matrix-bound DNA fraction; S, DNA fraction in the supernatant.

FIG. 9.

Comparison of a segment of mouse mitochondrial DNA (mu. mito. DNA) (having an A-T content of 66.6%) with the human beta interferon MAR (hu. Ifn. β), an E2 gene segment, and the early-late intergenic region (having A-T contents of 68.8, 61.3, and 69.3%, respectively) shows that A-T richness alone is not sufficient for binding the nuclear matrix in vitro. I, input; P, matrix-bound DNA; S, DNA fraction in the supernatant.

These data suggest that the E5 gene and part of the early-late intergenic region function as strong MARs. Minor affinity can be found through the E2 and E1 genes. No significant activity can be found in the late genes L2 and L1, although weak activity is suggested by the behavior of a 790-bp BspM1 fragment in the 3′ part of L2 (Fig. 4E). (Our data are schematically represented in Fig. 10A and are discussed below in the context of other observations.)

FIG. 10.

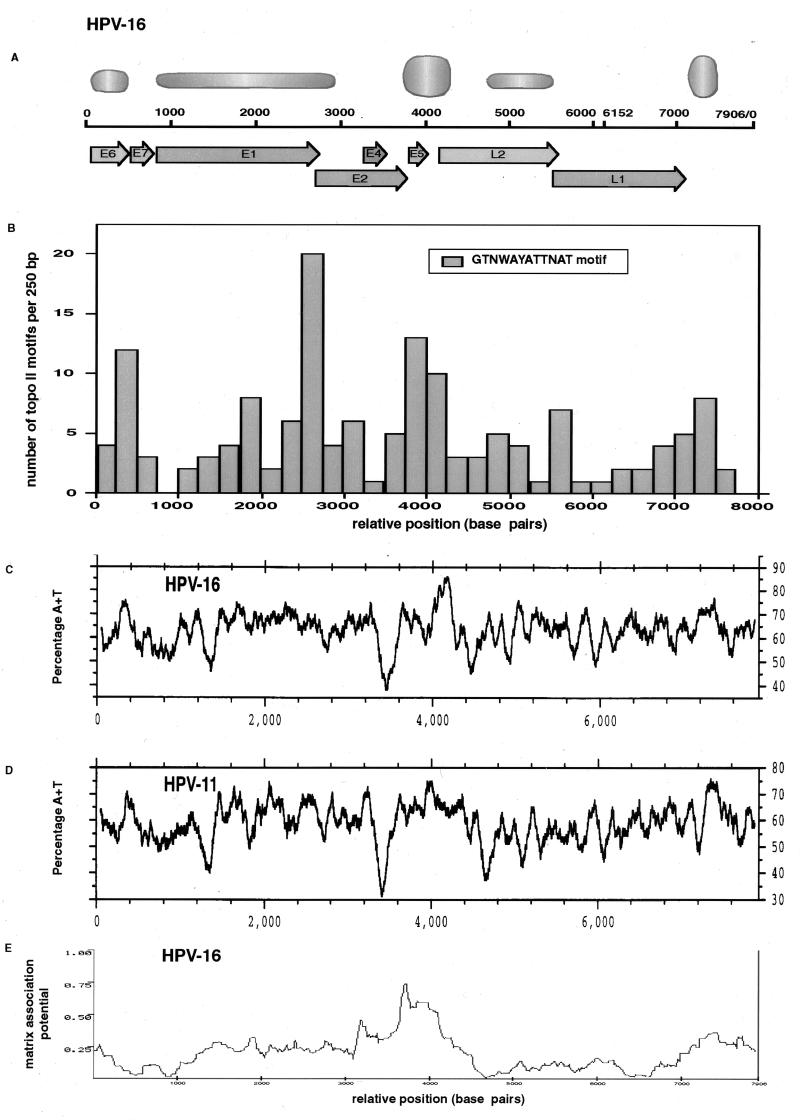

Genomic properties of HPV genomes. (A) Strong and weak MARs of HPV-16 (thicker and thinner symbols, respectively) relative to its gene organization. (B) Presence of Drosophila topoisomerase II (topo II) consensus sequences (51) in genital HPV types. The bars represent the occurrence of this sequence, with maximally one mismatch, in 250-bp segments after alignment with the sequence of 28 genital HPV types, whose genomic sequence is completely known (40a). (C and D) A+T contents of HPV-16 and HPV-11, respectively. The A+T contents a 100-bp window moved across the total genomic sequence are shown. (E) Prediction of MAR activity by the MAR finder computer algorithm with a window of 1 kb and steps of 10 bp (55).

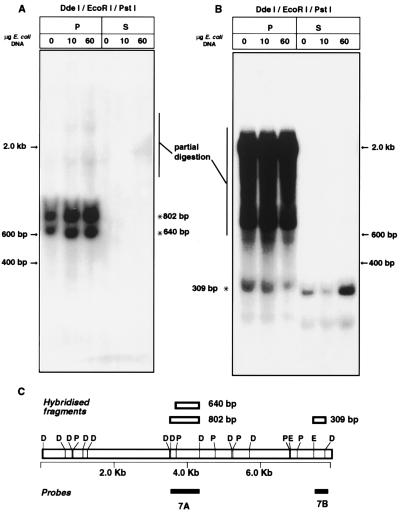

HPV-16 MAR activity in CaSki cells in vivo.

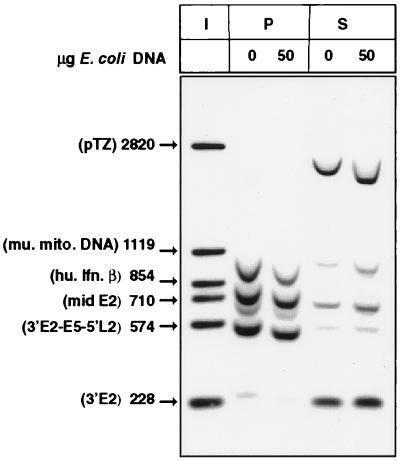

We decided to examine interactions between the HPV-16 genome and the nuclear matrix in vivo in a manner similar to that for the in vitro experiments. Toward this end, we digested nuclear matrix preparations of CaSki cells, which have approximately 500 endogenous HPV-16 genomes, with restriction enzymes, purified the DNA, and processed the preparations in Southern blots with radioactive HPV-16 DNA probes. The identification of specific bands in initial experiments was hampered by the presence of partially digested fragments and derivatives of the numerous recombined HPV-16 genomes known to exist in CaSki cells (5). It was possible, however, to compare two small genomic segments, both including the MAR of the E5 gene and the early-late intergenic region, with an enhancer fragment without MAR activity. Figure 7 shows that the latter segment could be competed with an excess of E. coli DNA, while the former could not be, and we conclude that this strong MAR, and possibly all HPV-16 MARs, shows in vivo activities similar to those observed in vitro and appears to be responsible for the adherence of the complete HPV-16 genome to the nuclear matrix as observed in Fig. 3.

FIG. 7.

The endogenous HPV-16 genomes of CaSki cells adhere to the nuclear matrix with the MAR of the E5–early-late intergenic region. I, input; P, matrix-bound DNA fraction; S, DNA fraction in the supernatant. The MAR was included in a 640-bp PstI-to-DdeI fragment between genomic positions 3697 and 4337 (panel A, lower band) or, alternatively, in the 802-bp DdeI fragment between genomic positions 3535 and 4337, generated by incomplete digestion by PstI of genomes embedded in nuclear matrix protein. As a fragment without MAR activity, we monitored a 309-bp segment from the enhancer region between an EcoRI site at position 7456 and a DdeI site at position 7764 (asterisk in panel B). Binding of this band could be competed by an excess of E. coli DNA. Since the probe used in panel B was shorter, less stringent hybridization and washing conditions (60 versus 65°C) were used. This resulted in its binding to more partially digested fragments than in panel A. Restriction enzyme site abbreviations in panel C: D, DdeI; P, PstI; E, EcoRI.

Multiple point mutations in the 5′-LCR MAR reduce the affinity to the nuclear matrix in vitro.

As a control for our observations, we attempted to mutate one of the MARs of HPV-16. A deletion analysis was strategically ruled out, as MARs show decreased affinity with decreasing size (8–10). Also, the testing of individual point mutations was precluded by the notion that MARs do not normally exhibit strictly conserved sequence motifs. It is known, however, that they contain (i) an increased frequency of motifs with similarity to the topoisomerase II recognition sites (51, 56), (ii) A-T rich regions, with prominence of the sequence ATATTT (12, 15, 55), and (iii) sequences that are rich in the dinucleotide TG. We have created three mutants of the 301-bp segment of the 5′ LCR with strong MAR affinity with 8, 17, and 23 point mutations, which alter similarities to these sequence traits (Fig. 8A). Although these mutations change only 2.7 to 7.8% of the sequence of the 5′ LCR segment, we determined by a densitometric analysis of Fig. 8A to D that these mutations reduced the affinity to the nuclear matrix by 50, 70, and 78%, respectively (58).

A-T richness alone is not sufficient for binding the nuclear matrix in vitro.

The early-late intergenic region and the 5′ LCR overlap with some of the more A-T-rich sequences of the HPV-16 genome (see Fig. 10C and discussion below). As it is known that a potential for duplex DNA destabilization is an intrinsic property of MARs (6), we determined whether A-T richness alone would generate MAR-like affinities in our test systems. Toward this goal, we compared a segment of mouse mitochondrial DNA, having an A-T content of 66.6%, with the human beta interferon DNA, the E2 gene segment, and the early-late intergenic region, which have A-T contents of 68.8, 61.3, and 69.3%, respectively. Figure 9 shows that the HPV-16 early-late segment has a 50% higher MAR affinity in vitro than the mitochondrial DNA, although its A-T content is similar, while the E2 gene segment, with a 5% lower A-T content, behaves similarly to the mitochondrial DNA. These findings do not support A-T richness of the LCR and the early-late intergenic segments as the only basis for MAR affinity.

DISCUSSION

MARs in the HPV-16 genome are close to cis-responsive elements.

The HPV-16 genome has at least five genomic segments with affinity to the nuclear matrix in vitro, as is summarized in Fig. 10A. Two MARs bracket a 500-bp segment of the LCR forming a functional unit which houses the epithelial cell-specific enhancer, the replication origin, and the E6 promoter. One of these two MARs is atypical in being completely positioned within a gene, namely, E6. This may indicate the existence of cis-responsive elements required for induction of a promoter in the E7 gene (24b). The other MAR is positioned in the 5′ segment of the LCR. This segment has an approximate length of 300 bp and stretches from the end of L1 to the only E2 site in the center of the LCR. The only known functional elements contained in this region are a transcription termination site and a regulatory element involved in transcript stability (21), although transcriptional modulation by this segment has been reported for HPV-11 (3, 19). Interestingly, this MAR of HPV-16 had been analyzed by footprint experiments (24a) before its function was understood, and it was found to contain several short footprints as well as a very extensive footprint, fp1l, covering more than 100 bp. Given that the size and A-T richness of this segment are conserved in all genital HPVs (Fig. 10C and D) (58), it is likely that the MAR properties of this segment are important for the life cycle of HPVs.

A third MAR, the strongest in our tests, overlaps with the E5 gene and the early-late intergenic region. This segment has the highest A-T content in the HPV-16 genome and those of other genital HPVs (Fig. 10C and our unpublished observations). Two additional genomic stretches with weak MAR affinity lie in the E1 and E2 genes and in the 3′ side of the L2 gene. We have mapped these MARs with less precision than the higher-affinity MARs.

It is likely that the five MARs detected in vitro are responsible for the in vivo matrix attachment of the whole HPV-16 genomes observed in SiHa, CaSki, and HPK cells. The sequence evaluations described below indicate that the attachment of HPV-11, HPV-18, and HPV-33 may stem from MARs in similar genomic positions. MARs may be highly conserved among all genital HPVs, as are the genes and other cis-responsive elements, although these viruses have overall sequence similarities of only about 60%.

Potential topoisomerase II cleavage sites and YY1 binding sites in HPV-16 are conserved between genital HPVs.

Topoisomerase II is a major component of the nuclear matrix (23), with cleavage sites for topoisomerase II frequently being associated with MAR affinity (12, 23, 32). Topoisomerase II makes double-strand nicks in DNA during the winding and unwinding reactions involved in transcription and replication. The binding and cleavage by topoisomerase II show sequence preference but not strict sequence specificity. Consensus recognition sequences have been published for Drosophila (51) and for chicken (56) topoisomerase II. These two consensus sequences are not very similar, although the topoisomerase II targets are probably the same, as the enzymes cleave similar sites in vitro (56). A search of topoisomerase II motifs in the genomes of 28 different genital HPVs by using the Drosophila (Fig. 10B) and the chicken (58) consensus elements predicts topoisomerase II sites to predominate in six genomic positions of these HPVs. Considering the correlation of topoisomerase II sites with MARs, it is noteworthy that in genital HPVs, three high-incidence areas of likely topoisomerase II sites lie close to the MARs we detected experimentally in HPV-16, namely, maxima at positions 500 and 7500, which flank the LCR, and around position 4000 at the early-late intergenic region. Three additional maxima overlap with the E1 and E2 genes and the 3′ end of L2, where we found weak MARs. It is surprising to observe such a specific distribution, as the functions of topoisomerase II are normally linked to the progression of replication forks and to the elongation of transcripts, and there seems little reason why these functions should otherwise be linked to the genomic organization of HPVs.

It should also be noted that the MAR in the 5′ LCR of HPV-16 contains a high-affinity YY1 site (positions 7427 to 7434) (42), which is present in all genital HPVs (43), as YY1 is a transcription factor preferentially enriched in nuclear matrix preparations (25). This site may contribute to the interaction of the 5′ LCR with the nuclear matrix, although in experiments not shown here we could not determine a differential affinity of the 5′-LCR segment of HPV-16 with a wild-type or mutated YY1 site (58).

The genomes of genital HPVs have a highly conserved pattern of A-T- and G-C-rich stretches that correlates with MARs of HPV-16.

Most MARs of cellular DNA have a high A-T content, a property also shown by the HPV-16 MARs in the 5′ LCR and in the early-late intergenic region (Fig. 10C). The genomes of HPV-11, HPV-16, HPV-18, and HPV-33 have overall A-T contents of 59, 63.5, 59.5, and 63.5%, respectively. A comparison of Fig. 10C and D shows that in HPV-16 and HPV-11, this A-T content is not homogenous through either of the genomes but that A-T- and G-C-rich segments alternate, with maxima of A-T richness between 70 and 85% and minima between 30 and 50%. The pattern of A-T and G-C richness is conserved between HPV-16 and HPV-11 (Fig. 10C and D) and between all other genital HPV types (58), in spite an overall sequence similarity of only about 60% among these HPV types. It is of interest that maxima of A-T richness in the 5′ LCR, E6, E5, and the early-late intergenic region coincide with the MAR properties of HPV-16.

Mathematical modelling predicts some of the MARs of HPV-16.

A computer program that allows the search for potential MARs has been developed (34, 55). This algorithm evaluates sequences for six different properties frequently found in MARs: (i) ATTTA-like motifs, (ii) A-T-rich sequences, (iii) TG dinucleotide-rich sequences, (iv) curved DNA, (v) kinked DNA, and (vi) topoisomerase II sites. Figure 10E shows that for HPV-16 this program predicts MARs flanking the LCR and in the early-late intergenic region but does not strongly indicate the other experimentally determined MARs. This algorithm consistently detected MARs close to the LCR, in E1-E2, and the early-late intergenic regions of many different HPVs, although the comparison between many types showed much less similarity than the study of A-T richness or the topoisomerase II sites alone did (58).

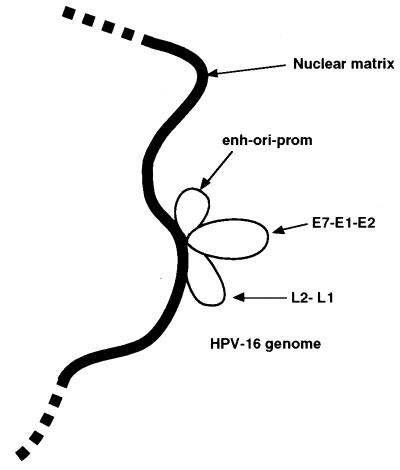

Possible functions of MARs in the HPV life cycle.

Figure 11 gives a hypothetical model of the higher-order structure of the HPV-16 DNA in the nucleus, with MARs anchoring three genomic loops: (i) the enhancer-replication origin-promoter region, (ii) most of the early genes, and (iii) the late genes. While this study aimed to provide structural data, future research will have to address the functional consequences of such structures. In the case of cellular genes, MARs have been found to support a number of very different processes, including transcriptional modulation, splicing and transport of mRNA, and replication. Similar roles may later be attributed to the HPV-16 MARs.

FIG. 11.

Schematic representation of the hypothetical topology of the HPV-16 genome attached to the nuclear matrix. Strong MARs in the 5′ LCR and in the E6 and the E5 genes create three accessible genomic loops, with MARs separating the cis-responsive elements of the LCR, the early genes, and the late genes. enh-ori-prom, enhancer-origin-promoter.

The proximity of two MARs to the HPV-16 enhancer and promoter suggests a role in transcriptional regulation, as MARs have been shown to work synergistically with promoters or enhancers, possibly by bringing cis-responsive elements close to matrix-bound transcriptional complexes (2, 10, 12, 13, 22, 40, 45, 57) or by generating an extended domain of accessible chromatin (31). The latter mechanism is reminiscent of the case for the bovine papillomavirus type 1 (BPV-1) LCR, which overlaps with the only nucleosome-free stretch of BPV-1 chromatin (50). It is of interest that the composition of the nuclear matrix can change in a differentiation-dependent manner (20, 33), as altered transcription of genital HPVs depending on the cell type (24), epithelial differentiation state (44), and tumorigenesis (54) is only partially understood.

One may postulate that the MAR in the E1-E2-E5 region of HPV-16 might stimulate recombination, particularly since in malignant lesions HPV genomes are often integrated by recombination of this part of the HPV genome with cellular DNA (5, 17, 37, 53, 54). Documented examples of a role of MARs in recombination are the integration of woodchuck hepatitis virus DNA close to cellular MARs during progression of hepatomas (11) and the integration of Agrobacterium T-DNA in transgenic plants at a MAR close to one T-DNA end (16).

Association between BPV-1 genomes and metaphase chromosomes has been proposed to support copy number control of BPV-1 genomes (38). As there are indications that a 672-bp fragment of BPV-1 adjacent to the viral origin of replication associates with the nuclear matrix (1), one may speculate that MARs could be a tool for papillomavirus genomes to attach to nuclear structures during mitosis toward equal partition between daughter nuclei. This is reminiscent of observations made for three other DNA viruses, simian virus 40 (SV40), adenoviruses, and Epstein-Barr virus. In the SV40 genome a MAR sequence has been mapped to a 300-bp segment central to the large T-antigen gene (47), which may help the SV40 genome to be preferentially associated with nuclear structures (14). The adenovirus genome has been found attached to the nuclear matrix in the form of episomal DNA, and this may occur with the help of the adenovirus-encoded protein covalently bound to the termini of the viral genome (52). Finally, a 5.2-kb segment of Epstein-Barr virus replicating as an episome allows high-affinity association with the nuclear matrix in Raji cells (26, 30) due to the close association of an MAR, the latent viral replication origin, and an enhancer.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Shyh-Han Tan and Dusan Bartsch contributed equally to this publication.

We are grateful to J. Bode, W. T. Garrard, S. A. Krawetz, and G. B. Singh for valuable and very detailed technical advice. The plasmids pCL and pGEM-xdelta were the kind gift of J. Bode. G. B. Singh created the MAR-finder program and assisted in its use. Robin M. Watts and Walter Stünkel gave valuable editorial advice in writing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adom J N, Gouilleux F, Richard-Foy H. Interaction with the nuclear matrix of a chimeric construct containing a replication origin and a transcription unit. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1171:187–197. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(92)90119-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antoniou M, Grosveld F. Beta-globin dominant control region interacts differently with distal and proximal promoter elements. Genes Dev. 1990;4:1007–1013. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.6.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auborn K J, Steinberg B M. A key DNA-protein interaction determines the function of the 5′URR enhancer in human papillomavirus type 11. Virology. 1991;181:132–138. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90477-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker C, Calef C. Maps of papillomavirus transcripts. In: Myers G, Halpern A, Baker C, McBride A, Wheeler C, Doorbar J, editors. Human papillomaviruses 1996 compendium, part III. Los Alamos, N.Mex: Los Alamos National Laboratory; 1996. pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker C C, Phelps W C, Lindgren V, Braun M J, Gonda M A, Howley P M. Structural and transcriptional analysis of human papillomavirus type 16 sequences in cervical carcinoma cell lines. J Virol. 1987;61:962–971. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.4.962-971.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benham C, Kohwi-Shigematsu T, Bode J. Stress-induced duplex DNA destabilization in scaffold/matrix attachment regions. J Mol Biol. 1997;274:181–196. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berezney R, Coffey D S. Identification of a nuclear protein matrix. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1974;60:1410–1417. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(74)90355-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berezney R, Mortillaro M J, Ma H, Wei X, Samarabandu J. The nuclear matrix: a structural milieu for genomic function. Int Rev Cytol. 1995;162A:1–65. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61228-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bode J, Maass K. Chromatin domain surrounding the human interferon-beta gene as defined by scaffold-attached regions. Biochemistry. 1988;27:4706–4711. doi: 10.1021/bi00413a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bode J, Schlake T, Rios-Ramirez M, Mielke C, Stengert M, Kay V, Klehr-Wirth D. Scaffold/matrix-attached regions: structural properties creating transcriptionally active loci. Int Rev Cytol. 1995;162A:389–454. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61235-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruni R, Argentini C, D’Ugo E, Guiseppetti R, Ciccaglione A R, Rapicetta M. Recurrence of WHV integration in the b3n locus in woodchuck hepatocellular carcinoma. Virology. 1995;214:229–234. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.9936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cockerill P N, Garrard W T. Chromosomal loop anchorage of the kappa immunoglobulin gene occurs next to the enhancer in a region containing topoisomerase II sites. Cell. 1986;44:273–282. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90761-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cockerill P N, Yuen M H, Garrard W T. The enhancer of the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus is flanked by presumptive chromosomal loop anchorage elements. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:5394–5407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deppert W, Schirmbeck R. The nuclear matrix and virus function. Int Rev Cytol. 1995;162A:485–537. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61237-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dickinson L A, Joh T, Kohwi Y, Kohwi-Shigematsu T. A tissue-specific MAR/SAR DNA-binding protein with unusual binding site recognition. Cell. 1992;70:631–645. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90432-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dietz A, Kay V, Schlake T, Landsmann J, Bode J. A plant scaffold attached region detected close to a T-DNA integration site is active in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:2744–2751. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.14.2744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El Awadi M, Kaplan J B, O’Brien S J, Burk R D. Molecular analysis of integrated human papillomavirus 16 sequences in the cervical cancer cell line SiHa. Virology. 1987;159:389–398. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90478-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fackelmayer F, Richter A. Purification of two isoforms of hnRNA-U and characterization of their nucleic acid binding activity. Biochemistry. 1994;33:10416–10422. doi: 10.1021/bi00200a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farr A, Pattison S, Youn B S, Roman A. Detection of silencer activity in the long control regions of human papillomavirus type 6 isolated from both benign and malignant lesions. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:827–835. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-4-827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fey E G, Penman S. Nuclear matrix proteins reflect cell type of origin in cultured human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:121–125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.1.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furth P A, Choe W T, Rex J H, Byrne J C, Baker C C. Sequences homologous to 5′ splice sites are required for the inhibitory activity of papillomavirus late 3′ untranslated regions. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:5278–5289. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.8.5278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gasser S M, Laemmli U K. Cohabitation of scaffold binding regions with upstream/enhancer elements of three developmentally regulated genes of D. melanogaster. Cell. 1986;46:521–530. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90877-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gasser S M, Laroche T, Falquet J, Boy de la Tour E, Laemmli U K. Metaphase chromosome structure. Involvement of topoisomerase II. J Mol Biol. 1986;188:613–629. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(86)80010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gloss B, Bernard H U, Seedorf K, Klock G. The upstream regulatory region of the human papillomavirus-16 contains an E2 protein-independent enhancer which is specific for cervical carcinoma cells and regulated by glucocorticoid hormones. EMBO J. 1987;6:3735–3743. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02708.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24a.Gloss B, Chong T, Bernard H-U. Numerous nuclear proteins bind the long control region of human papillomavirus type 16: a subset of 6 of 23 DNase I-protected segments coincides with the location of the cell-type-specific enhancer. J Virol. 1989;63:1142–1152. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.3.1142-1152.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24b.Grassmann K, Rapp B, Maschek H, Petry K U, Iftner T. Identification of a differentiation-inducible promoter in the E7 open reading frame of human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV-16) in raft cultures of a new cell line containing high copy numbers of episomal HPV-16 DNA. J Virol. 1996;70:2339–2349. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2339-2349.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo B, Odgren P R, van Wijnen A J, Last T J, Nickerson J, Penman S, Lian J B, Stein J L, Stein G S. The nuclear matrix protein NMP-1 is the transcription factor YY1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10526–10530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hörtnagel K, Mautner J, Strobl L J, Wolf D A, Christoph B, Geltinger C, Pollack A. The role of immunoglobulin kappa elements in c-myc activation. Oncogene. 1995;10:1393–1401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Howley P M. Field’s virology. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Raven Publishers; 1996. Papillomavirinae: the viruses and their application; pp. 2045–2076. [Google Scholar]

- 28.International Agency for Research on Cancer. Monograph on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. 64. Human papillomaviruses. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jackson D A, Cook P R. A general method for preparing chromatin containing intact DNA. EMBO J. 1985;4:913–918. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03718.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jankelevich S, Kolman J L, Bodnar J W, Miller G. A nuclear matrix attachment region organizes the Epstein-Barr viral plasmid in Raji cells into a single DNA domain. EMBO J. 1992;11:1165–1176. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05157.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jenuwein T, Forrester W C, Fernandez-Herrero L A, Laible G, Dull M, Grosschedl R. Extension of chromatin accessibility by nuclear matrix attachment regions. Nature. 1997;385:269–272. doi: 10.1038/385269a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kas E, Chasin L A. Anchorage of the Chinese hamster dihydrofolate reductase gene to the nuclear scaffold occurs in an intragenic region. J Mol Biol. 1987;198:677–692. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keesee S K, Meneghini M D, Szaro R P, Wu Y J. Nuclear matrix proteins in human colon cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1913–1916. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kramer J A, Singh G B, Krawetz S A. Computer assisted search for nuclear matrix attachment. Genomics. 1996;33:305–308. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li H, Bingman P M. Arginine/serine-rich domains of the su(wa) and tra RNA processing regulators target proteins to a subnuclear compartment implicated in splicing. Cell. 1991;67:335–342. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90185-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lutfalla G, Blanc H, Bertolotti R. Shuttling of integrated vectors from mammalian cells to E. coli is mediated by head-to-tail multimeric inserts. Somat Cell Mol Genet. 1985;11:223–238. doi: 10.1007/BF01534679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matsukura T, Kanda T, Furuno A, Yoshikawa H, Kawana T, Yoshiike K. Cloning of monomeric human papillomavirus type 16 DNA integrated within cell DNA from a cervical carcinoma. Virology. 1986;58:979–982. doi: 10.1128/jvi.58.3.979-982.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McBride A A, Skiadopoulos M. Abstracts from the 15th International Papillomavirus Workshop, Queensland. 1996. BPV-1 viral genomes and the E2 transactivator protein are associated with cellular metaphase chromosomes; p. 163. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mielke C, Kohwi Y, Kohwi-Shigematsu T, Bode J. Hierarchical binding of DNA fragments derived from scaffold-attached regions: correlation of properties in vitro and function in vivo. Biochemistry. 1990;29:7475–7485. doi: 10.1021/bi00484a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mirkovitch J, Mirault M E, Laemmli U K. Organization of the higher-order chromatin loop: specific DNA attachment sites on nuclear scaffold. Cell. 1984;39:223–232. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90208-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40a.Myers G, Bernard H U, Delius H, Baker C, Icenogel J, Halpern A, Wheeler C. Human papillomaviruses 1995. A compilation and analysis of nucleic acid and amino acid sequences. Los Alamos, N.Mex: Los Alamos National Laboratory; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakayasu H, Berezney R. Nuclear matrins: identification of the major nuclear matrix proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:10312–10316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.10312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Connor M J, Tan S H, Tan C H, Bernard H U. YY1 represses human papillomavirus type 16 transcription by quencing AP-1 activity. J Virol. 1996;70:6529–6539. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.6529-6539.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Connor M, Chan S Y, Bernard H U. Transcription factor binding sites in the long control regions of genital HPVs. In: Myers G, Bernard H U, Delius H, Baker C, Icenogle J, Halpern A, Wheeler C, editors. Human papillomaviruses 1995 compendium, part III-A. Los Alamos, N.Mex: Los Alamos National Laboratory; 1995. pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parker J N, Zhao W, Askins K J, Broker T R, Chow L T. Mutational analyses of differentiation-dependent human papillomavirus type 18 enhancer elements in epithelial raft cultures of neonatal foreskin keratinocytes. Cell Growth Differ. 1997;8:751–762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Phi-Van L, Strätling W H. The matrix attachment regions of the chicken lysozyme gene co-map with the boundaries of the chromatin domain. EMBO J. 1988;7:655–664. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02860.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Piirsoo M, Ustav E, Mandel T, Stenlund A, Ustav M. Cis and trans requirements for stable episomal maintenance of the BPV-1 replicator. EMBO J. 1996;15:1–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pommier Y, Cockerill P N, Kohn K W, Garrard W T. Identification within the simian virus 40 genome of a chromosomal loop attachment site that contains topoisomerase II cleavage sites. J Virol. 1990;64:419–423. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.1.419-423.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rohlfs M, Winkenbach S, Meyer S, Rupp T, Dürst M. Viral transcription in human keratinocyte cell lines immortalized by human papillomavirus type 16. Virology. 1991;183:331–342. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Romig H, Fackelmeyer F O, Renz A, Ramsperger U, Richter A. Characterization of SAF-A, a novel nuclear DNA binding protein from HeLa cells with high affinity for nuclear matrix/scaffold attachment DNA elements. EMBO J. 1992;11:3431–3440. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05422.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rösl F, Waldeck W, Sauer G. Isolation of episomal bovine papillomavirus chromatin and identification of a DNase I-hypersensitive region. J Virol. 1983;46:567–574. doi: 10.1128/jvi.46.2.567-574.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sander M, Hsieh T. Drosophila topoisomerase II double-strand cleavage: analysis of DNA sequence homology at the cleavage site. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:1057–1072. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.4.1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schaack J, Ho W Y, Freimuth P, Shenk T. Adenovirus terminal protein mediates both nuclear matrix association and efficient transcription of adenovirus DNA. Genes Dev. 1990;4:1197–1208. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.7.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schneider-Gädicke A, Schwarz E. Different human cervical carcinoma cell lines show similar transcription pattern of human papillomavirus type 18 early genes. EMBO J. 1986;5:2285–2292. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04496.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schwarz E, Freese U K, Gissmann L, Mayer W, Roggenbuck B, Stremlau A, zur Hausen H. Structure and transcription of human papillomavirus sequences in cervical carcinoma cells. Nature. 1985;314:111–114. doi: 10.1038/314111a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Singh G B, Kramer J A, Krawetz S A. Mathematical model to predict regions of chromatin attachment to the nuclear matrix. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1419–1425. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.7.1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Spitzner J R, Muller M T. A consensus sequence for cleavage by vertebrate DNA topoisomerase II. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:5533–5556. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.12.5533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stief A, Winter D M, Stratling W H, Sippel A E. A nuclear DNA attachment element mediates elevated and position-independent gene activity. Nature. 1989;341:343–345. doi: 10.1038/341343a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tan, S. H., and H. U. Bernard. Unpublished observations.

- 59.van Driel R, Wansink D G, van Steensel B, Grande M A, Schul W, de Jong L. Nuclear domains and the nuclear matrix. Int Rev Cytol. 1995;162A:151–189. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61231-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Van Wijnen A J, Bidwell J P, Fey E G, Penman S, Lian J B, Stein J L, Stein G S. Nuclear matrix association of multiple sequence-specific DNA binding activities related to Sp1, ATF, CCAAT, C/EBP, Oct-1, and AP-1. Biochemistry. 1993;32:8397–8402. doi: 10.1021/bi00084a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]