Abstract

Central nervous system injuries have a high rate of resulting in disability and mortality; however, at present, effective treatments are lacking. Programmed cell death, which is a genetically determined form of active and ordered cell death with many types, has recently attracted increasing attention due to its functions in determining the fate of cell survival. A growing number of studies have suggested that programmed cell death is involved in central nervous system injuries and plays an important role in the progression of brain damage. In this review, we provide an overview of the role of programmed cell death in central nervous system injuries, including the pathways involved in mitophagy, pyroptosis, ferroptosis, and necroptosis, and the underlying mechanisms by which mitophagy regulates pyroptosis, ferroptosis, and necroptosis. We also discuss the new direction of therapeutic strategies targeting mitophagy for the treatment of central nervous system injuries, with the aim to determine the connection between programmed cell death and central nervous system injuries and to identify new therapies to modulate programmed cell death following central nervous system injury. In conclusion, based on these properties and effects, interventions targeting programmed cell death could be developed as potential therapeutic agents for central nervous system injury patients.

Keywords: central nervous system injuries, death pyroptosis, ferroptosis, inflammation, mitophagy, necroptosis, programmed cell

Introduction

Central nervous system (CNS) injuries, including traumatic brain injury (TBI), subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), spinal cord injury (SCI), and stroke, are the leading cause of long-term disability and death worldwide (Zhang et al., 2022a). Conventional therapies for CNS injuries mainly attempt to relieve mechanical compression by surgery combined with hyperbaric oxygen therapy, nerve dehydration, and other comprehensive strategies (Hu et al., 2022a). However, due to a paucity of effective pharmacological treatments, the long-term rehabilitation outcomes following CNS injuries are poor, which reflects an incomplete understanding of the complicated pathobiological mechanisms (Zhang et al., 2023a).

Programmed cell death (PCD) is a regulated mechanism of action that is mediated by signal transduction pathways. Under normal conditions, PCD is an active form of cell death that occurs during development and under environmental stimulation (Yang et al., 2022b). However, under pathological conditions, excessive PCD can cause neurodegeneration and autoimmune diseases (Zhang et al., 2022b). The most common form of PCD, apoptosis, has being widely studied (Hu et al., 2022a); however, more recently, other forms of PCD have been identified. Depending on different mechanisms and morphologies, non-apoptotic PCD can be divided into autophagy, pyroptosis, ferroptosis, and necroptosis (Pang et al., 2022). Importantly, mitophagy, a type of selective autophagy, has gained increasing attention (Shao et al., 2022). Although these types of PCD have different features, they also share some similar characteristics, with considerable overlap and crosstalk (Lin et al., 2021).

Recently, the role of PCD in CNS injuries has been explored. Growing evidence suggests that mitophagy, pyroptosis, ferroptosis, and necroptosis are highly associated with the progression of CNS injuries (Zhang et al., 2022d). In this review, we clarify the effects of mitophagy, pyroptosis, ferroptosis, and necroptosis in CNS injuries. This review discusses: (1) the role of PCD in CNS injuries; (2) crosstalk among PCD pathways in CNS injuries; and (3) regulators of mitophagy in CNS injuries.

Retrieval Strategy

In this narrative review, a computer-based online search of the PubMed database was performed to retrieve articles published up to July 31, 2023. A combination of the following text words (MeSH terms) was used to maximize the search specificity and sensitivity: “central nervous system injury”; “programmed cell death”; “mitophagy”; “pyroptosis”; “ferroptosis”; and “necroptosis”. The results were further screened by title and abstract, and only studies exploring the relationship between PCD in CNS injuries were included. No language or study type restrictions were applied. Articles involving only CNS injury without PCD were excluded.

Role of Programmed Cell Death in Central Nervous System Injuries: Mitophagy, Pyroptosis, Ferroptosis, and Necroptosis

Mitophagy, pyroptosis, ferroptosis, and necroptosis are genetically determined forms of ordered cell death (Zhang and Liu, 2022; Table 1). All have been reported to be involved in CNS injuries, which may explain the pathological mechanisms of brain damage (Table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of programmed cell death (PCD) in central nervous system (CNS) injuries

| PCD | Mitophagy | Pyroptosis | Ferroptosis | Necroptosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morphological features | Formation of double-membraned autolysosomes containing the damaged mitochondria | Cell lysis, formation of pores in cell membrane and massive leakage of cytoplasmic components | Mitochondrion dysmorphic shrunken with increased membrane density, decreased crista and ruptured outer membrane | Cell swelling, organelle dysfunction, plasma membrane disintegration and cell lysis |

| Nuclear features | Nuclear pyknosis | Peculiar form of nuclear chromatin condensation | No nuclear changes | Change to sickle-like nuclear |

| Biochemical features | Increased lysosomal activity | Caspase-1/4/5/11 activation and proinflammatory cytokines release | Iron-dependent LPO accumulation | Release of DAMPs and triggering of cell death |

| Genes | PINK1, Parkin, BNIP3, NIX, FUNDC1, LC3 | NLPR3, AIM2, GSDM, caspase-1/4/5/11, IL-1β, IL-18 | TF, TFRC, GSH, GPX4, ACSL4 | RIPK1, RIPK3, MLKL |

| Pathways | PINK1/Parkin/ubiquitin pathway, receptor-mediated pathway | NLRP3/caspase-1/GSDMD pathway, caspase-4/5/11/GSDMD pathway | TF/TFRC pathway, Xc-/GSH/GPX4 pathway, ACSL4/PUFA/ALOXs pathway | RIPK1/RIPK3/MLKL pathway |

| Activators | Energetic stress, nutrient deficiency, hypoxia | Invading pathogens, endogenous stress | Iron, extracellular glutamine | TNF-α/TNFR1, MKLK |

| Inhibitors | 3-MA, Mdivi-1 | Inflammasome inhibitors | Iron chelators, ferrostatin-1, liproxstatin-1, antioxidants | Necrostatin-1 |

| Effects | Remove damaged mitochondria | Suppress inflammation | Inhibit oxidant stress | Reduce cell death |

3-MA: 3-Methyladenine; ACSL4: acyl coenzyme A synthetase long-chain family member 4; AIM2: absence in melanoma 2; BNIP3: BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa interacting protein 3; DAMPs: damage-associated molecular patterns; FUNDC1: FUN14 domain containing 1; GPX4: glutathione peroxidase 4; GSDM: gasdermin; GSH: glutathione; IL-18: interleukin-18; IL-1β: interleukin-1β; LC3: microtubule-associated protein light chain 3; LPO: lipid peroxidation; Mdivi-1: mitochondrial division inhibitor-1; MLKL: mixed lineage kinase domain-like pseudokinase; NIX: NIP3-like protein X; NLRP3: NLR family pyrin domain containing 3; Parkin: Parkinson protein 2 E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase; PINK1: phosphatase and tensin homolog induced kinase 1; PLOOH: phospholipid hydroperoxide; RIPK1: receptor interacting serine/threonine protein kinase 1; RIPK3: receptor interacting serine/threonine protein kinase 3; TF: transferrin; TFRC: transferrin receptor; TNFR1: tumor necrosis factor receptor 1; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-α.

Table 2.

The functions of programmed cell death (PCD) in central nervous system (CNS) injuries

| PCD | Models | Animals and/or cells | Beneficial functions of regulating PCD | Regulators | Upstream molecules |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mitophagy | Ischemic stroke | Mice | Inhibited inflammation, alleviated neurological deficits | EE | mTOR, Drp1 |

| Mice, HT-22 cells | Reduced cell death and apoptosis | BCP | PINK1, Parkin | ||

| Rats, neurons | Ameliorated neuronal injury, improved mitochondrial function | LIG | PINK1, Parkin | ||

| Rats | Suppressed oxidative stress and apoptosis | Metformin | AMPK | ||

| Neurons | Promoted neuronal survival | Mfn2 | Parkin | ||

| Mice, PC12 cells | Decreased brain infarction volume and neuronal apoptosis | DHA | PINK1, Parkin, Drp1 | ||

| Mice, N2a cells | Rescued neuronal loss and apoptosis | Ori | RIPK3 | ||

| SAH | BMECs | Increased cell viability | 14,15-EET | SIRT1, FOXO3a | |

| Mice, neurons | Alleviated neuroinflammation, reduced neuronal apoptosis | T3 | PINK1, Parkin | ||

| Rats | Decreased oxidative stress and neurological dysfunction | ACEA | PINK1, Parkin | ||

| Rats | Inhibited oxidative stress-related neuronal death | Mitoquinone | Nrf2, PHB2 | ||

| Mice | Inhibited neuron apoptosis | Melatonin | Nrf2 | ||

| TBI | Mice | Improved cognitive dysfunction | IGF-1 | MiR-let-7e | |

| Mice, N2a cells | Ameliorated cognitive impairment | RvD1 | ALX4, FPR2 | ||

| Rats | Improved tissue repair, preserved neurological function | Nitroxides | Drp1, LC3 | ||

| Rats | Inhibited oxidative stress and neuroinflammation | PFT-α, PFT-μ | PINK1 | ||

| SCI | PC12 cells | Inhibited oxidative stress | Maltol | PINK1, Parkin, Nrf2 | |

| Mice, neurons | Improved functional recovery, reduced apoptosis | Sal | PINK1, Parkin | ||

| Mice, neurons | Inhibited apoptosis | GIT1 | PINK1 | ||

| Mice | Attenuated apoptosis | Rapamycin | p62, Parkin | ||

| ICH | Rats | Mitigate neurologic impairment, reduced apoptosis | SA | PINK1, Parkin, NIX | |

| Rats, neurons | Reduced cerebral edema and neurobehavioral impairment | MIC60 | PINK1, Parkin | ||

| Rats | Suppressed apoptosis | EA | BNIP3, PINK1, Parkin | ||

| Hypoxia | PC12, SH-SY5Y cells | Protected brain against hypoxia-induced damage | Caffeic acid | BNIP3 | |

| IR | Mice | Attenuated cognitive impairment and neuron damage | CoQ10 | PINK1, Parkin | |

| Pyroptosis | Ischemic stroke | Mice, BV2 microglia | Improved neurological function, inhibited inflammation | LncRNA Tug1 | MiR-145a-5p, TLR4 |

| Rats | Rescued neurological deficits, attenuated neuroinflammation | H2S | NLRP3 | ||

| Mice, BV2 cells | Reduced neurological deficits and infarct lesion | CX3CL1 | GSDMD | ||

| Rats, HT22 cells | Inhibited behavior deficits, ischemic lesions and neuronal death | XBP-1 | NLRP3, caspase-1 | ||

| Mice, neurons | Attenuated ischemic stroke | Ginsenoside Rd | MiR-139-5p, FOXO1, Nrf2 | ||

| Mice | Reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines | Exercise | NLRP3, ASC | ||

| Rats | Improved neurological dysfunction, reduced the infarct volume | Remimazolam | NLRP3 | ||

| Rats | Improved neurological deficits, reduced neuroinflammation | VNS | α7nAchR, NLRP3 | ||

| Rats, BMECs | Enhanced antioxidant activity and MMP | PCA | LncRNA Xist | ||

| Mice | Ameliorated white matter injury | Curcumin | NF-κB, NLRP3 | ||

| Rats, PC12 cells | Alleviated inflammation | Indobufen, Aspirin | NF-κB, NLRP3 | ||

| SAH | Rats | Alleviated neurological dysfunction and inflammatory injury | SAHA | miR-340, NEK7 | |

| Microglia | Inhibited the release of proinflammatory cytokines | Dex | PI3K, AKT, GSK3β | ||

| Rats | Suppressed neuroinflammation and blood coagulation | VX-765 | Caspase-1 | ||

| Mice | Inhibited blood-brain barrier destruction | COG133 | NLRP3 | ||

| Rats | Improved neurological functions | APC | NLRP3 | ||

| Microglia | Ameliorated brain edema and neuronal death | SRT1720 | SIRT1, NLRP3 | ||

| Rats | Improved neurobehavioral dysfunctions and neuronal degeneration | Rh-CXCL-12 | CXCR4, NLRP1 | ||

| TBI | Mice | Reduced brain edema, Attenuated disruption of BBB | SIRT2 knockout | SIRT2, NLRP3 | |

| Mice | Improved neurological deficits, inhibited neuronal cell insult | Abcg1 | RXRα, PPARγ | ||

| Mice | Improved functional recovery | PDGF | NLRP3, caspase1, GSDMD | ||

| Rats | Alleviated emotional impairments, neuronal loss and inflammation | C-176 | STING, NLRP3 | ||

| Mice, BV2 cells | Improved neurological deficits, Reduced inflammatory cytokine | HUMSCs | TSG-6, NLRP3 | ||

| Rats | Reduced brain tissue injury, improved functional recovery | GAS | NLRP3 | ||

| Mice | Alleviated neurological deficits, mitigated neural cell death | ACE2 | NLRP3 | ||

| SCI | Rats, PC12 cells | Decreased neuroinflammation | BMSCs | Circ_003564, NLRP3 | |

| Mice | Inhibited neuroinflammation, increased functional recovery | Dopamin | NLRP3 | ||

| Mice | Reduced neuron death, improved functional recovery | Topotecan | NLRP3, caspase-1 | ||

| Mice | Inhibited inflammatory and oxidative stress | Piperine | NLRP3 | ||

| Rats, BV2 cells | Relieved pathological injury, promoted cell viability | pcDNA3.1-Nrf2 | MiR-146a, GSDMD | ||

| Neurons | Promoted functional behavior and axon regeneration | M2-Exos | MiR-672-5p, AIM2 | ||

| ICH | Mice | Alleviated neuronal degeneration, reduced membrane pore | RKIP | Caspase-1, GSDMD | |

| Mice | Alleviated neuroinflammation | Dectin-1 | NLRP3, GSDMD | ||

| Rats | Promoted neurologic function recovery | BMSCs | MiR-23b, PTEN, Nrf2 | ||

| Chicken, Purkinje cells | Suppressed infiltration of inflammatory cells | PM | AMPK, ASC, NLRP3 | ||

| Mice | Improved neurological function | Aprepitant | NK1R, PKCδ, NLRC4 | ||

| Mice | Improved neurobehavioral performance, decreased BBB disruption | Didymin | ASC, caspase-1, GSDMD | ||

| Mice | Decreased neurological deficits and neuroinflammation | CCR5 | PKA, CREB | ||

| Ferroptosis | Ischemic stroke | Rats | Increased neurological function | MiRNA-27a | Nrf2, GPX4, GSH |

| Rats | Inhibited oxidative stress, endothelial damage and BBB disruption | P2RX7 | ERK1/2, p53 | ||

| Mice, neurons | Reduced infarct area, enhanced cell viability | Danhong | SATB1, SLC7A11, HO-1 | ||

| Mice, HT22 cells | Improved cell viability, ameliorated cerebral injury | Baicalein | GPX4, ACSL4, ACSL3 | ||

| Rats, PC12 cells | Alleviated infarct volume, facilitated cell viability | ELAVL1 | DNMT3B | ||

| Neurons | Decreased neuronal death | cPKCγ | ACSL4, GPX4 | ||

| Rats, astrocytes | Improved neurological scores, infarct volume | β-Caryophyllene | Nrf2, HO-1 | ||

| Rats, SH-SY5Y cells | Improved cognitive impairment and neurological deficits | Rehmannioside A | PI3K, AKT, Nrf2 | ||

| SAH | Mice, microglia | Improved neural function and neuronal apoptosis | S100A8 | GPX4, GSH | |

| Rats | Reduced oxidative stress | Astragaloside IV | Nrf2, HO-1 | ||

| Rats | Improved neurological impairment | PKR | GPX4 | ||

| Mice, HT22 cells | Alleviated oxidative stress | RSV | SIRT1, ACSL4, GPX4 | ||

| Rats | Improved neurological impairment, attenuated oxidative stress | Puerarin | AMPK, PGC1α, Nrf2 | ||

| Mice | Improved AQP4 depolarization and BBB injury | AQP4 | Transferrin | ||

| TBI | Mice, BMVECs | Reduced cell death, BBB permeability and tight junction loss | Ferrostatin-1 | COX-2, GPX4 | |

| Mice, neurons | Improved neural function, increased neuron viability | PPARγ | COX-2, GPX4 | ||

| Mice | Decreased neuronal damage, improved cognitive function | MSCs | GPX4 | ||

| Mice, HT-22 cells | Alleviated neuronal injury and neurodegeneration | Ferristatin II | TfR1 | ||

| Mice, neurons | Suppressed ER stress | Melatonin | CircPtpn14, miR-351-5p | ||

| Mice | Alleviated neurological indications and brain edema | SIRT2 | p53, GPX4 | ||

| Mice | Alleviated brain water content and neurodegeneration | Ruxolitinib | GPX4 | ||

| SCI | Rats | Promoted the recovery of hindlimb function | Erythropoietin | xCT, GPX4 | |

| Rats | Promoted the survival of neurons and oligodendrocytes | Sodium selenite | ACSL4, GPX4 | ||

| Rats | Decreased inflammatory factors, improved long-term outcomes | Metformin | Nrf2, GPX4 | ||

| Mice | Improved axon regeneration and remyelination | GDF15 | p62, Nrf2 | ||

| Mice, neurons | Promoted neuron survival, improved motor function | Trehalose | Nrf2, HO-1 | ||

| Rats | Alleviated white matter injury, promoted functional recovery | Ferrostatin-1 | ACSL4, GPX4 | ||

| Mice | Enhanced neurological function, increased cell proliferation | MSCs | LncGm36569, miR-5627-5p | ||

| Neurons | Increased cell viability, decreased cell death | LXA4 | AKT, Nrf2, HO-1 | ||

| ICH | Mice, neurons | Improved neurological impairment, increased cell viability | circAFF1 | miR-140-5p/GSK-3β | |

| Mice | Suppressed oxidative stress | Dex | GPX4 | ||

| Mice | Alleviated white matter injury, facilitated motor coordination | DPX | GPX4, FSP1 | ||

| Mice, BMVECs | Increased cell viability | METTL3 | GPX4 | ||

| Rats, neurons | Promoted the recovery of neural function | PPARγ | Nrf2, GPX4 | ||

| Mice | Reduced hematoma volume, attenuated cell apoptosis | Vildagliptin | GSH-px | ||

| Mice | Decreased brain edema and neurological deficits | Crocin | Nrf2, GPX4, GSH-px | ||

| Mice, neurons | Improved neurobehavior | Lactoferrin | COX-2, Ptgs2 | ||

| Necroptosis | Ischemic stroke | BMECs | Enhanced cell viability, | PNS | RIP1, RIP3, MLKL |

| Rats, HT22 cells | Alleviated brain injury | Polymyxin B | ESCRT-III, RIPK1, MLKL | ||

| Rats | Improve the neurological deficits | HePC | p-RyR2 | ||

| Rats, PC12 cells | Improved neurological function, reduced infarct volume | Caspofungin | Pellino3, RIPK1, RIPK3 | ||

| Mice | Decreased infarct volume, improved neurological function | Inactive RIP1, RIP3 | RIP1, RIP3, MLKL | ||

| Rats | Ameliorated neuronal death and pro-inflammatory factors | 10panx | HMGB1, RIP3 | ||

| Mice | Attenuated oxidative damage | Progranulin | RIP1, RIP3, MLKL | ||

| Rats, PC12 cells | Reduced infarct volume and cell death | Ligustroflavone | RIP1, RIP3, MLKL | ||

| Rats | Decreased cell death | Necrostatin-1 | RIP1, RIP3, MLKL | ||

| Mice, HT22 cells | Decreased infarction size, cell death and inflammation | TRAF2 | RIP1, RIP3, MLKL | ||

| Rats | Reduced infarction volume, improved survival rate | Ex-527 | SIRT1, RIP3, MLKL | ||

| SAH | Rats | Alleviated BBB disruption, improved neurological score | Celastrol | RIP3, MLKL | |

| Rats | Attenuated brain swelling, reduced lesion volume | Necrostatin-1 | RIP3, MLKL | ||

| Rats, neurons | Reduced brain edema, improved neurological function | Inhibition of RIP3 | RIP3 | ||

| Rats | Alleviated brain edema, improved neurobehavior scores | Necrostatin-1 | RIP1, RIP3 | ||

| Rats | Attenuate brain edema, improved neurological function | GSK-872 | RIP3, MLKL | ||

| TBI | Rats | Improved the prognosis of TBI rats | Pramipexole | RIP1 | |

| Mice, microglia | Reduced cortical lesion volume, inhibited inflammation | Fetuin-A | Nrf2, HO-1 | ||

| Mice | Enhanced neurological outcomes, minimized cell death | Hydrogen | Nrf2, HO-1, RIP1 | ||

| Neurons | Preserved morphological changes, attenuated cell death | Perampanel | AKT, GSK3β, RIP1 | ||

| Mice | Prevented neuronal cell death, improved memory function | RIPK1, RIPK3 deletion | RIP1, RIP3 | ||

| Rats | Suppressed neuronal death and inflammation | TNFAIP3 | RIP1, RIP3, MLKL | ||

| Rats | Reduced cortical tissue loss | 2-BFI | RIP1, RIP3, MLKL | ||

| Mice | Attenuated oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis | RIP3 knockout | RIP3 | ||

| Rats | Inhibited cell death and inflammation | Hypothermia | RIP1, RIP3, MLKL | ||

| Mice | Suppressed autophagy and apoptosis | Necrostatin-1 | Beclin-1, Bcl-2 | ||

| Mice | Reduced histopathology, improved functional outcome | Necrostatin-1 | / | ||

| SCI | PC12 cells | Reduced necroptosis | N-acetylserotonin | MLKL | |

| Rats | Reduce SCI size, promoted motor function recovery | EODF | RIP1, RIP3 | ||

| Mice | Improved ethological score and histopathological deterioration | Astragalin | RIP1, RIP3, MLKL | ||

| Mice | Optimized function-related recovery | GDF-11 | AMPK, TRPML1 | ||

| Rats | Improved locomotor function | Jia-Ji EA | RIP1, RIP3, MLKL | ||

| Mice | Attenuated demyelination, neuronal loss and axonal damage | Dabrafenib | RIP3 | ||

| Rats | Improved functional recovery | Quercetin | SIRT1, RIP3, MLKL | ||

| Mice | Ameliorated locomotor function and spinal cord edema | GSK-872, Necrostatin-1 | RIP3 | ||

| Rats | Reduced lesions and neuron cell death | Necrosulfonamide | RIP1, RIP3, MLKL | ||

| Mice, PC12 cells | Caused potentiation of necroptosis | Rapamycin | RIP1, RIP3, MLKL | ||

| Rats | Mitigated endoplasmic reticulum stress | Necrostatin-1 | CHOP, BiP, XBP-1 | ||

| Rats | Decreased cell death | PSMB4 | RIP3, MLKL | ||

| ICH | Mice | Reduced neurons death, improved neurological functions | Necrosulfonamide | RIP1, RIP3 | |

| Mice | Increased neurological score, alleviated brain edema | Ulinastatin | RIP1, RIP3 | ||

| Mice | Mitigated cerebral edema and neurobehavioral defects | GSK872 | RIP3, MCP-1 | ||

| Mice | Increased neurological score and neuron survival | Cerebrolysin | AKT, GSK3β, RIP1 | ||

| Mice | Increased survival rate and neurological score | Perampanel | RIP1, RIP3, MLKL | ||

| Rats, neurons | Decreased cell death | Microglia exosomes | MiR-383-3p, ATF4 | ||

| Mice | Reduced brain edema and neurological deficits | RIP3 siRNA | RIP3, CaMKII, AIF | ||

| Mice | Improved neurological function, reduced brain edema | Metformin | AMPK | ||

| Mice | Promoted cell survival | Melatonin | TNFAIP3, RIP3 | ||

| Rats, neurons | Inhibited albumin extravasation and BBB permeability | RIP1 inhibition | RIP1, RIP3, MLKL | ||

| Mice | Improved neurological function, attenuated brain edema | Necrostatin-1 | RIP1, RIP3 |

14,15-EET: 14,15-Epoxyeicosatrienoic acid; 2-BFI: 2-(2-Benzofuranyl)-2-imidazoline; Abcg1: ATP-binding cassette transporter g1; ACE2: angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; ACEA: arachidonyl-2-chloroethylamide; ACSL3: acyl coenzyme A synthetase long-chain family member 3; ACSL4: acyl coenzyme A synthetase long-chain family member 4; AIF: apoptosis-inducing factor; AIM2: absence in melanoma 2; AKT: protein kinase B; ALX4: aristaless-like homeobox 4; AMPK: adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase; APC: activated protein C; AQP4: aquaporin 4; ASC: apoptosis-associated speck-like protein; ATF4: activating transcription factor 4; BBB: blood-brain barrier; Bcl-2: B-cell lymphoma 2; BCP: β-caryophyllene; BiP: immunoglobulin-binding protein; BMECs: brain microvascular endothelial cells; BMSCs: bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells; BMVECs: brain microvascular endothelial cells; BNIP3: BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa interacting protein 3; CaMKII: Ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent kinase II; CCR5: C-C chemokine receptor 5; CHOP: C/EBP homologous protein; Circ: circRNA; CNS: central nervous system; COX-2: cyclooxygenase-2; cPKCγ: conventional protein kinase C gamma; CREB: cAMP-response element binding protein; CX3CL1: C-X3-C motif chemokine ligand 1; CXCR4: C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4; Dectin-1: dendritic cell-associated C-type lectin-1; Dex: dexmedetomidine; DHA: docosahexaenoic acid; DNMT3B: DNA methyltransferase 3B; DPX: dexpramipexole; Drp1: dynamin-related protein 1; EE: enriched environment; EODF: every-other-day fasting; ER: endoplasmic reticulum; ERK1/2: extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2; ESCRT-III: endosomal sorting complex required for transport-III; FOXO1: forkhead box protein O1; FOXO3a: forkhead box protein O3a; FPR2: formyl peptide receptor 2; FSP1: ferroptosis suppressing protein 1; GAS: gastrodin; GDF-11: growth differentiation factor 11; GDF15: growth differentiation factor 15; GIT1: GPCR kinase 2-interacting protein-1; GPX4: glutathione peroxidase 4; GSDM: gasdermin D; GSH: glutathione; GSH-px: glutathione peroxidase; GSK3β: glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta; GSK-3β: glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta; H2S: hydrogen sulfide; HePC: heliox preconditioning; HMGB1: high mobility group box 1; HO-1: heme oxygenase-1; HUMSCs: human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells; ICH: intracerebral hemorrhage; IGF-1: insulin-like growth factor-1; IR: ionizing radiation; CoQ10: coenzyme Q10; Jia-Ji EA: Jia-Ji electro-acupuncture; LC3: microtubule-associated protein light chain 3; LIG: ligustilide; LncRNA: long non-coding ribonucleic acid; LXA4: lipoxin A4; M2-Exos: M2 microglia-derived exosomes; MCP-1: monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; METTL3: methyltransferase-like 3; Mfn2: mitofusin 2; MiR: microRNA; MLKL: mixed lineage kinase domain-like pseudokinase; MMP: mitochondrial membrane potential; MSCs: mesenchymal stromal cells; mTOR: mammalian target of rapamycin; NEK7: NIMA-related kinase 7; NF-κB: nuclear transcription factor-kappa B; NIX: NIP3-like protein X; EA: electroacupuncture; NK1R: neurokinin-1 receptor; NLRC4: NLR family containing a caspase recruitment domain-containing protein 4; NLRP1: NLR family pyrin domain-containing 1; NLRP3: NLR family pyrin domain-containing 3; Nrf2: nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor 2; Ori: oridonin; P2RX7: P2X7 receptor; Parkin: Parkinson protein 2 E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase; PCA: protocatechuic aldehyde; PCD: programmed cell death; PDGF: platelet derived growth factor; PFT-α: pifithrin-α; PFT-μ: pifithrin-μ; PGC1α: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma co-activator 1 alpha; PHB2: prohibitin 2; PI3K: phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PINK1: phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten-induced putative kinase 1; PKA: protein kinase A; PKCδ: protein kinase C-delta; PKR: protein kinase R; PM: polystyrene microplastic; PNS: panax notoginseng saponins; PPARγ: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ; p-RyR2: phospho-ryanodine receptor type 2; PSMB4: proteasome beta-4 subunit; PTEN: phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten; Rh-CXCL-12: recombinant human cysteine-X-cysteine chemokine ligand 12; RIP1: receptor interacting protein 1; RIP3: receptor interacting protein 3; RIPK3: receptor-interacting protein kinase-3; RKIP: Raf kinase inhibitor protein; RSV: resveratrol; RvD1: resolvin D1; RXRα: retinoid X receptor alpha; SA: scalp acupuncture; SAH: subarachnoid hemorrhage; SAHA: suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid; Sal: salidroside; SATB1: special AT-rich sequence binding protein 1; SCI: spinal cord injury; SIRT1: Sirtuin 1; SIRT2: Sirtuin 2; SLC7A11: solute carrier family 7 member 11; STING: stimulator of interferon gene; T3: triiodothyronine; TBI: traumatic brain injury; TfR1: transferrin receptor 1; TLR4: toll-like receptor 4; TNFAIP3: tumor necrosis factor α-induced protein 3; TRAF2: tumor necrosis factor receptor associated factor 2; TRPML1: transient receptor potential mucolipin 1; TSG-6: Tumor necrosis factor α stimulated gene 6/protein; VNS: vagus nerve stimulation; XBP-1: X-box binding protein 1; α7nAchR: α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor.

Mitophagy

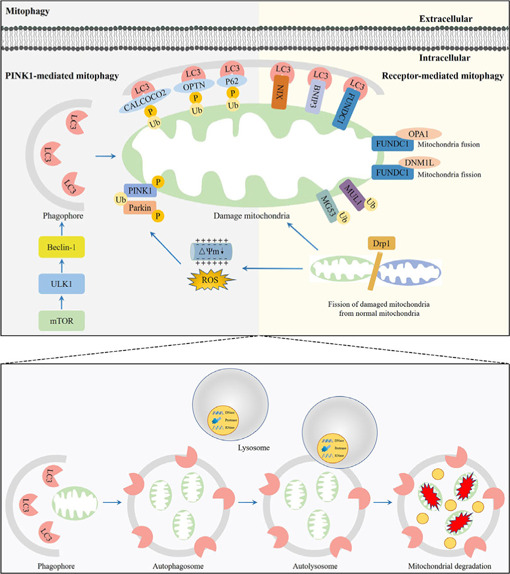

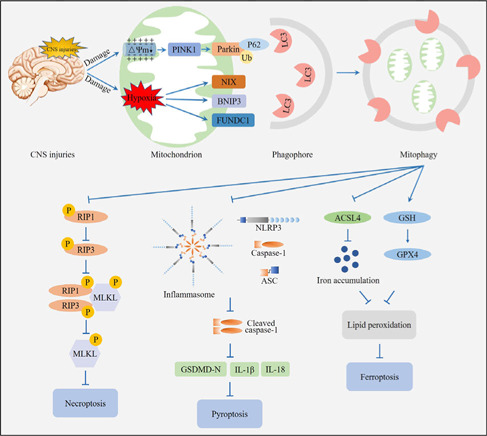

Mitophagy was first proposed by Lemasters in 2005 (Lemasters, 2005); it is a crucial process involving the removal of undesired and damaged mitochondria, which impacts multiple physiological and pathological processes in the brain (Wu et al., 2022). The process of mitophagy includes synthesis of an autophagosome, incorporation of the mitochondrion, fusion with a lysosome to create an autolysosome, and degradation of the mitochondrion by the autolysosome (Zhu et al., 2022b). Mitophagy can be activated by nutrient deficiency, hypoxia, chemical stimulation, and loss of the mitochondrial membrane potential (Zhu et al., 2022b). These events lead to mitochondrial damage and activate different mitophagy pathways, including the phosphatase and tensin homolog induced kinase 1/Parkinson protein 2 E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase (PINK1/Parkin)-mediated ubiquitin pathway and receptor-mediated pathway (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of the mitophagy pathway.

Unc-51 like autophagy activating kinase 1 (ULK1) initiates formation of the phagophore by responding to nutrient stress signals from mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR). Phosphatase and tensin homolog induced kinase 1 (PINK1)-mediated mitophagy. Dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) induces the fission of damaged mitochondria (in green) from healthy mitochondria (in blue). The phosphorylated PINK1 accumulates on the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) when mitochondria are damaged due to loss of the mitochondrial membrane potential or stimulation by reactive oxygen species (ROS), and subsequently recruits Parkinson protein 2 E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase (Parkin) to the mitochondria. The E3 ligase PRKN polyubiquitinates multiple OMM proteins, which will be recognized by microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 (LC3) receptors, including calcium binding and coiled-coil domain 2 (CALCOCO2), optineurin (OPTN), and p62, on the phagophore. Receptor-mediated mitophagy. Receptors locating at the OMM, including NIP3-like protein X (NIX), BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa interacting protein 3 (BNIP3), and FUN14 domain containing 1 (FUNDC1), bind with LC3 proteins to mediate autophagosome formation. Ubiquitin ligases of mitochondrial E3 ubiquitin ligase 1 (MUL1) and Mitsugumin 53 (MG53) recruit more phagophores to assist in mitophagy implementation. Dephosphorylation of FUNDC1 enhances mitochondrial fission by disassembly of optic atrophy 1 (OPA1) and interaction with dynamin-like protein 1 (DNML1) on the mitochondria. Damaged mitochondria are engulfed by phagophores to form the autophagosome, followed by the fusion with lysosomes to form autolysosomes that degrade the damaged mitochondria. Created with Adobe Photoshop CS4.

PINK1/Parkin-mediated ubiquitin pathway

The PINK1/Parkin-mediated ubiquitin pathway is the main pathway that activates mitophagy (Goiran et al., 2022). When the mitochondrial membrane potential is damaged, entry of PINK1 into the inner mitochondrial membrane is blocked, resulting in the accumulation of PINK1 on the cytoplasmic surface of the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM; Silvian, 2022). The accumulation of PINK1 on the OMM recruits and activates Parkin, leading to a change in the spatial conformation of the Parkin protease, which then converts into the activated E3 ubiquitin ligase and promotes the ubiquitination of the mitochondrial proteins. PINK1 interacts with Parkin to jointly regulate mitophagy to maintain mitochondrial quality (Goiran et al., 2022).

Receptor-mediated pathway

Mitophagy can also be mediated by the mitochondrial receptors, including BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa interacting protein 3 (BNIP3), NIP3-like protein X (NIX), and FUN14 domain containing 1 (FUNDC1; Chu, 2019). BNIP3 and NIX are proteins with homology to Bcl-2 in the BH3 domain, which are important mediators of hypoxia-induced mitophagy (Marinkovic and Novak, 2021). The LIR motif in the BNIP3 homodimer binds to microtubule-associated protein light chain 3B (LC3B) to induce mitophagy. The interaction of BNIP3 LIR with LC3B requires phosphorylation of its Serine residues Ser17 and Ser24 (Vara-Perez et al., 2019). NIX is a selective mitophagy receiver because its terminal amino acids 3–38 form an LIR sequence and bind to LC3A. NIX-mediated mitophagy requires phosphorylation of NIX Ser81, and the NIX Ser81a mutation results in it being unable to bind to LC3A or LC3B (Yuan et al., 2017). FUNDC1 binds to LC3B via its LIR motif and facilitates mitophagy through autophagosome formation. However, the phosphorylation state of FUNDC1 determines its affinity for LC3B. For example, phosphorylation of FUNDC1 at Ser17 by Unc-51 like autophagy activating kinase 1 (ULK1) facilitates the FUNDC1-LC3B interaction, accelerating mitophagy. In contrast, phosphorylation of FUNDC1 at a tyrosine (Tyr) residue in the LIR motif by SCR1 kinase inhibits mitophagy (Yao et al., 2021).

Role of mitophagy in CNS injuries

Recent advances in the field of brain research have revealed the pivotal role of mitophagy in neuronal cell fate and neurological function (Wang et al., 2022c). Mitophagy was also reported to suppress CNS injury-induced brain damage (Wang et al., 2022c). Lin et al. (2016) suggested that melatonin inhibited inflammation and activated mitophagy through the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway following TBI, while treatment with 3-methyladenine (3-MA) reversed this effect by attenuating mitophagy. Furthermore, Mao et al. (2022) indicated that in PC12 cells, Maltol promoted mitophagy and inhibited oxidative stress and apoptosis through the Nrf2/PINK1/Parkin pathway following SCI. In addition, in SAH models, Chang et al. (2022) found that triiodothyronine (T3) treatment promoted PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy, reduced reactive oxygen species (ROS), suppressed microglial activation, inhibited inflammation, and decreased apoptosis. Furthermore, these preventative effects were reversed by PINK1-siRNA treatment, suggesting that T3 exerted a protective role in early brain injury (EBI) after SAH via the PINK1/Parkin pathway.

Pyroptosis

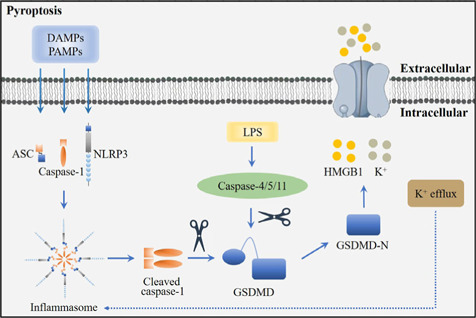

Pyroptosis is a type of inflammatory PCD that is characterized by the formation of pores in the cell membrane, cell lysis, and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Al Mamun et al., 2022). The activation of pyroptosis mainly includes the classical pathway and non-classical pathway (Lin et al., 2021; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Overview of the pyroptosis pathway.

In respond to damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) or pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) can recruit and activate caspase-1 via apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing CARD (ASC) to form the inflammasome. Caspase 4/5/11 are activated in the cytoplasm after stimulated by lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Activated caspase 1/4/5/11 further promotes the cleavage and production of N-terminal domains of gasdermin D (GSDMD-N), leading to pyroptosis. Pyroptosis regulated by potassium efflux triggers the release of high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) and K+. Created with Adobe Photoshop CS4.

Classical pathway of pyroptosis

The classical pathway of pyroptosis is induced by inflammasomes and is performed by caspase-1 and the gasdermin (GSDM) protein family. Inflammasomes are multimolecular complexes containing pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs), apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing CARD (ASC), and pro-caspase-1 (Coll et al., 2022). In classical pyroptosis, pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), or damage-associated molecular patterns, are identified by PRRs and promote the activation of PRRs. Activated PRRs bind to the PYD structural domain at the N-terminal end of the bridging protein (Lu et al., 2022b). ASC then recruits pro-caspase-1 through interaction of the CARD structural domain to complete the assembly of the inflammasome. Once activated, cleaved caspase-1 further cleaves the N-terminal and C-terminal domains of gasdermin D (GSDMD). The GSDMD-N acts as the conduits for the transport of interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18, which ultimately induces pyroptosis and the inflammatory response (Zhang et al., 2021).

Non-classical pathway of pyroptosis

The non-classical pathway of pyroptosis is mainly mediated by caspase-4, caspase-5, and caspase-11 (Morimoto et al., 2021). In response to bacterial lipopolysaccharide, caspase-4, caspase-5, and caspase-11 are activated, and specifically cleave GSDMD-N (Lee et al., 2018). GSDMD-N then binds to cell membrane phospholipids, resulting in cell membrane pore formation, cell swelling, rupture, and the induction of pyroptosis (Lee et al., 2018).

Role of pyroptosis in CNS injuries

Pyroptosis also participates in the pathogenesis of CNS injuries. Gastrodin inhibits the NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome; therefore, attenuating pyroptosis, reducing brain tissue injury, and improving neurological functions in TBI rats (Yang et al., 2022a). Furthermore, Xia et al. (2022) revealed that Chrysophanol significantly suppressed the levels of pyroptosis-related proteins, such as NLRP3, cleaved caspase-1, GSDMD-N, and tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6), in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury. However, NLRP3 overexpression neutralized the neuroprotection of Chrysophanol (Xia et al., 2022). In addition, using SCI models, Zhao et al. (2022) suggested that bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes decreased pyroptosis markers, including cleaved caspase-1, GSDMD, NLRP3, IL-1β, and IL-18. This effect was attenuated by knockdown of circRNA_003564, showing that bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell exosomes attenuated pyroptosis by delivering circRNA_003564.

Ferroptosis

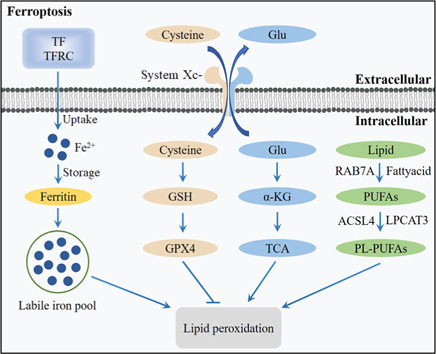

Ferroptosis is a newly discovered, non-necrotizing form of PCD. Biologically, the key feature of ferroptosis is iron-dependent lipid peroxidation (LPO) accumulation. Morphologically, the characteristics of ferroptosis comprise a decrease in mitochondrial volume and mitochondrial cristae, and an increase in mitochondrial membrane density (Yang et al., 2022c). Generally, the process of ferroptosis includes iron-induced LPO accumulation and an imbalance in the antioxidant systems (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Overview of the ferroptosis pathway.

The transferrin (TF)-transferrin receptor (TFRC) complex promotes iron accumulation by upregulation of iron uptake and downregulation of iron storage, leading to increased lipid peroxidation (LPO) and ferroptosis. Antioxidant systems, such as system Xc-/glutathione/glutathione peroxidase 4 (system Xc-/GSH/GPX4), can inhibit LPO. Cysteine can be transported into the cell, whereas glutamate (Glu) can be transported out of the cell by the system Xc-. Cysteine can be used to synthesize GSH to maintain the balance of the redox state. Glu can be converted to α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) and participates in tricarboxylic acid (TCA), thereby activating LPO. Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) derived from lipids can be catalyzed by acyl-coenzyme A synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4) and lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3 (LPCAT3) to phospholipid-polyunsaturated fatty acids (PL-PUFAs), and PL-PUFAs play a critical role in ferroptosis by promoting LPO. Created with Adobe Photoshop CS4.

LPO

Iron-induced LPO is the key process that activates ferroptosis (Zhou et al., 2020). Excess iron accumulation contributes to LPO through the production of ROS and the activation of iron-containing enzymes, such as arachidonic acid lipoxygenases (ALOXs) (Liu et al., 2022b). In the presence of acyl-coenzyme A synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4) and lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3 (LPCAT3), polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) is catalyzed to develop phospholipids-polyunsaturated fatty acid (PL-PUFA). PL-PUFA is further catalyzed by ALOXs to produce phospholipid hydroperoxides (PLOOH), which can promote ferroptosis (Shui et al., 2021).

Antioxidant systems

Several antioxidant systems can inhibit LPO and suppress ferroptosis. For example, the system Xc–/glutathione/glutathione peroxidase 4 (system Xc–/GSH/GPX4) antioxidant system plays a crucial role in protecting cells from ferroptosis (Hao et al., 2022b). GPX4 is a primary enzyme that catalyzes the reduction of PLOOH to alcohols. The activation of GPX4 provides cells with cysteine, an essential cellular antioxidant and a building block of GSH, which reduces PLOOH to phospholipids and cholesterol hydroperoxides. Both phospholipids and cholesterol hydroperoxides are further reduced to their corresponding fatty alcohol, leading to decreased damage to the plasma membrane and suppression of ferroptosis (Jiang et al., 2021).

Role of ferroptosis in CNS injuries

An increasing number of studies have indicated that ferroptosis is involved in CNS injuries. Wang et al. (2022b) indicated that repetitive mild traumatic brain injury caused time-dependent alterations in ferroptosis-related biomarkers, such as abnormal iron metabolism, inactivation of glutathione peroxidase (GPx), a decrease in GPX4 levels, and an increase in LPO. However, treatment with human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stromal cells (hUCB-derived MSCs) decreased repetitive mild traumatic brain injury-induced ferroptosis (Wang et al., 2022b). In a rat SCI model, Chen et al. (2022b) found that the iron concentration and the levels of LPO products malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxynonenal were increased, while the protein and mRNA expression of specificity protein 1 and GPX4 were decreased, demonstrating that ferroptosis was activated following SCI. Treatment with sodium could suppress ferroptosis and promote recovery of the locomotive function of rats with SCI, demonstrating that sodium could improve the outcome of SCI possibly through inhibition of ferroptosis (Chen et al., 2022b). In addition, Huang et al. (2022) revealed that the iron concentration and the protein levels of 4-hydroxynonenal, malondialdehyde, ACSL4, and oxidized glutathione were significantly increased, whereas the levels of superoxide dismutase, GPX4, and GSH were decreased in the ipsilateral hemisphere following SAH. However, puerarin treatment could inhibit SAH-induced ferroptosis and ameliorate neurological dysfunction.

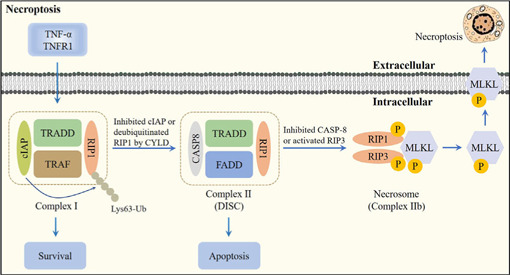

Necroptosis

Necroptosis was first proposed by Degterev et al. in 2005. It possesses the features of necrosis, including cell swelling, dysfunction of organelles, disintegration of the plasma membrane, lysis of the cell, release of damage-associated molecular patterns, and triggering of cell death (Zhang et al., 2023b), but has its own signaling pathway, which requires receptor interacting Ser/Thr protein kinase 1 (RIP1), RIP3, and mixed lineage kinase domain-like pseudokinase (MLKL), which can be specifically blocked by necrostatins (Roberts et al., 2022). In the absence of caspase-8 or FAS-associated death-domain-containing protein, specific death receptors or PRRs still induce cell necrosis, causing necroptosis (Teh et al., 2022; Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Overview of the necroptosis pathway.

Following tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) binding to TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1), cellular inhibitor of apoptosis protein (cIAP), TNFR1-associated death domain protein (TRADD), tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor (TRAF), and receptor interacting Ser/Thr protein kinase 1 (RIP1) are recruited to form Complex I. cIAP can induce the Lys63-linked polyubiquitination (Lys63-Ub) of RIP1 to increase cell survival. Furthermore, inhibition of cIAP or deubiquitination of RIP1 by cylindromatosis (CYLD) promotes the conversion of Complex I to Complex II. When caspase-8 is activated in Complex II, apoptosis is initiated. When caspase-8 is inhibited or receptor interacting Ser/Thr protein kinase 3 (RIP3) is activated, RIP1, RIP3, and mixed lineage kinase domain-like pseudokinase (MLKL) are recruited to form the necrosome via phosphorylation. Activation of MLKL mediates membrane pore formation and results in necroptosis. Created with Adobe Photoshop CS4.

Regulatory mechanisms of necroptosis

Following the interaction of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) with TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1), TNFR1 recruits a variety of proteins, including TNFR1-associated death domain protein, RIP1, TNFR-associated factor 2/5 (TRAF2/5), and linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex (LU-BAC), to form Complex I (Mohanty et al., 2022). The conversion of Complex I into Complex II is facilitated by de-ubiquitination of RIP1 by cylindromatosis. If caspase-8 is activated in Complex II, apoptosis is initiated (Li et al., 2022b). When RIP3 is rich and caspase-8 is inhibited, RIP1 recruits RIP3 and both recruit MLKL to form the necrosome, leading to necroptosis (Hao et al., 2022a).

Role of necroptosis in CNS injuries

The potential effects of necroptosis in CNS injuries have been confirmed by various studies. It has been shown that the expression levels of the necroptosis markers RIP1, RIP3, MLKL, phosphorylated (p)-RIP3, and p-MLKL were upregulated in the surrounding areas of the lateral ventricle following intraventricular hemorrhage in mice. However, treatment with necrostatin-1 (NEC-1), a necroptosis inhibitor, effectively reduced the necroptosis markers, suggesting that NEC-1 could prevent necroptosis induced by intraventricular hemorrhage (Liu et al., 2022). Furthermore, in a rat SAH model, Chen et al. (2019) reported that the expression of RIP3 and MLKL was increased. Treatment with NEC-1 significantly reduced the expression of RIP3 and MLKL, indicating that NEC-1 provided neuroprotective effects on SAH possibly via the prevention of RIP3-mediated necroptosis. In addition, in an in vitro model of ischemia stroke, administration of panax notoginseng saponins and NEC-1 could protect brain microvascular endothelial cells from oxygen glucose deprivation/reperfusion (OGD/R)-induced necroptosis by inhibiting the phosphorylation of RIP1, RIP3, and MLKL, suggesting that panax notoginseng saponins and NEC-1 effectively reduced the occurrence of necroptosis in ischemic stroke by inhibition of the RIP1/RIP3/MLK signaling pathway (Hu et al., 2022b).

Interaction between these PCDs

Although there are considerably differences in the mechanisms and characteristics of the abovementioned PCDs, there are some important associations and connections among them. Researchers have made important progress over recent decades, finding that these PCDs not only have functional interactions, but also have evolutionary origins (Zhang et al., 2022b). For example, mitophagy could directly promote or inhibit the occurrence of necroptosis. During the death of necrotic cells, mitophagy can transport non-decomposable cell products to the cytoplasm, thereby ensuring normal metabolism in cells (Zhang et al., 2023b). Furthermore, in the early stages of brain injury, cells can stimulate the expression of mitophagy-related proteins, thereby fully exerting the physiological function of mitophagy to attenuate other PCDs (Chen et al., 2024). In addition, both pyroptosis and necroptosis have the same solubility and potential inflammatory morphology, which lead to a mechanism intersection between these two pathways. The NLRP3 inflammasome is activated when cell ion homeostasis changes, leading to pyroptosis. However, this characteristic also allows for its activation in response to membrane damage caused by MLKL (terminal effector of necroptosis). Through this mechanism, cells that undergo necroptosis can also undergo activation of the process of pyroptosis, and their death is usually accompanied by the activation of IL-1β and cleavage of IL-18 (Zhang et al., 2022b).

Mitophagy and Pyroptosis Crosstalk in Central Nervous System Injuries

Mitophagy and pyroptosis crosstalk was first reported to exhibit neuroprotection in CNS injuries in 2020; the neuroprotection of mitophagy-regulated pyroptosis was mainly attributed to its effects on the inhibition of inflammation (Yu et al., 2020; Figure 5 and Table 3).

Figure 5.

Crosstalk among mitophagy, pyroptosis, ferroptosis, and necroptosis in central nervous system (CNS) injuries.

CNS injuries cause damage to the mitochondrion and activate mitophagy. Mitophagy further attenuates necroptosis, pyroptosis, and ferroptosis, resulting in decreased brain damage. Created with Adobe Photoshop CS4.

Table 3.

The role of mitophagy-mediated programmed cell death (PCD) in central nervous system (CNS) injuries

| PCD | Models | Animals and/or cells | Beneficial effects of regulating mitophagy-mediated PCD | Regulators | Upstream molecules | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyroptosis | Neuron injury | Neurons, microglia | Suppressed ROS production, inhibited pyroptosis and inflammation | Quercetin | PINK1, Parkin, BNIP3 | Han et al., 2021 |

| I/R injury | SH-SY5Y cells | Increased cell viability, alleviated pyroptosis and inflammation | HuMSC-exos | FOXO3a, TOMM20 | Hu et al., 2021 | |

| SCI | Mice | Promoted functional recovery, eliminated ROS, inhibited pyroptosis | Betulinic acid | AMPK, mTOR, TFEB | Wu et al., 2021 | |

| Ferroptosis | Neurotoxicity | Mice, PC12 cells | Improved learning and memory ability, inhibited neurotoxicity | TDCPP | PINK1, Parkin, VDAC1 | Qian et al., 2022 |

| Necroptosis | I/R injury | Mice, MEFs | Inhibited neurological deficits and infarct size, enhanced cell viability | PGAM5 | PINK1, LC3 | Lu et al., 2016 |

AMPK: Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase; BINP3: Bcl-2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa protein-interacting protein 3; BNIP3: BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa interacting protein 3; Dex: dexmedetomidine; FOXO3a: forkhead box protein O3a; HIR: Hepatic ischemia-reperfusion; HuMSC-exos: human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes; I/R: ischemia/reperfusion; LC3: microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3; MEFs: mouse embryonic fibroblasts; mTOR: mammalian target of rapamycin; OMM20: translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 20; Parkin: Parkinson protein 2 E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase; PGAM5: phosphoglycerate mutase family member 5; PINK1: phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten-induced putative kinase 1; ROS: reactive oxygen species; SCI: spinal cord injury; SIRT3: Sirtuin 3; TDCPP: Tris (1,3-dichloro-2-propyl) phosphate; TFEB: transcription factor EB; VDAC1: voltage-dependent anion channel 1.

Mitophagy, pyroptosis, and inflammation

An increasing number of studies have proposed that mitophagy-mediated pyroptosis exerts a central effect in CNS injury-induced inflammation. Han et al. showed that quercetin (Qu) attenuated lipopolysaccharide-induced neuronal injury through inhibition of inflammatory factor production, suppression of NF-κB activation, and downregulation of pyroptosis-related proteins, including NLRP3, caspase-1, GSDMD-N, and cleaved IL-1β. Importantly, Qu promoted mitophagy, enhancing the elimination of damaged mitochondrial and alleviating activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, illustrating that Qu prevented NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis by promoting mitophagy (Han et al., 2021). Furthermore, in a hypoxic-ischemic brain damage model, mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-exos) decreased the levels of NLRP3, cleaved caspase-1, GSDMD-N, IL-1β, and IL-18 in OGD/R-exposed BV-2 cells. MSC-exos also increased the levels of mitophagy markers, including translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 20 (TOMM20) and cytochrome c oxidase IV (COX IV). Suppression of mitophagy by 3-MA and Mdi-1 attenuated the inhibitory effects of MSC-exos on pyroptosis, demonstrating that MSC-exos enhanced mitophagy to protect microglia from OGD/R-induced pyroptosis and alleviated subsequent neuronal injury (Hu et al., 2021).

Mechanisms linking mitophagy and NLRP3-mediated pyroptosis

The underlying mechanisms linking mitophagy and NLRP3-mediated pyroptosis in CNS injuries are immensely complicated. Studies have indicated that mtROS and mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid (mtDNA) might be the key targets. Oxidized mtDNA can directly bind to NLRP3, leading to inflammasome formation and caspase-1 activation. Both mtROS and mtDNA can promote NLRP3/ASC/pro-caspase-1 complex assembly (Yan et al., 2022). Therefore, inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome by an mtROS or mtDNA scavenger could effectively suppress caspase-1 cleavage and pyroptosis (Peng et al., 2020). Recently, it has been shown that damaged mitochondria can release or display signals, such as mtROS and mtDNA, which function as assembly activators to promote and amplify the NLRP3 inflammasome (Sandhir et al., 2017). In lipopolysaccharide-induced neuronal injury, mitophagy-dependent degradation of injured mitochondrion decreased the release of mtROS and mtDNA, suppressed NLRP3 inflammasome, inhibited pyroptosis, and attenuated neurotoxicity (Han et al., 2021).

Mitophagy and Ferroptosis Crosstalk in Central Nervous System Injuries

To date, few studies have reported on the crosstalk between mitophagy and ferroptosis in CNS injuries. In 2022, Qian et al. indicated that Tris (1,3-dichloro-2-propyl) phosphate (TDCPP) caused neurotoxicity via mitophagy-related ferroptosis, which was related to its role in oxidative stress (Figure 5 and Table 3).

Mitophagy, ferroptosis, and oxidative stress

In mice and PC12 cells, upon TDCPP exposure, the expression of ferroptosis-related proteins, such as solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11), GPX4 and cyclooxygenase 2 (COX 2), and mitophagy-related proteins, such as PINK1, Parkin, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type 1 (IP3R1), and voltage-dependent anion channel 1 (VDAC1), were altered in the hippocampus. Furthermore, ferroptosis was associated with TDCPP-induced neurotoxicity and oxidative stress; the mechanism might be related to PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy initiated by mitochondrial damage (Qian et al., 2022).

Mechanisms between mitophagy and ferroptosis

Ferroptosis is attributed to LPO caused by the production of ROS and iron overload (Tang et al., 2020); therefore, mitophagy may mediate ferroptosis through the regulation of ROS and intracellular iron levels. Excessive production of ROS enhances ferroptosis and mitophagy. In return, mitophagy reduces ROS production and inhibits ferroptosis, playing a protective role (Li et al., 2021). The transport of iron ions across the mitochondrial matrix and inner mitochondrial membrane requires the mitoferrins Mfrn1 and Mfrn2. Mitophagy impairs iron translocation from the mitochondrial matrix and inner mitochondrial membrane to the cytoplasm via disruption of Mfrn1 and Mfrn2, leading to impaired cytoplasmic iron accumulation and ferroptosis (Chung et al., 2014).

Additionally, VDAC1 is an important protein in the crosstalk between mitophagy and ferroptosis. It is a key mitochondrial permeability transition regulator that locates to the OMM and sensitizes cells to mitochondrial permeability transition following CNS injuries (Tanaka et al., 2018). VDAC1 is the only channel-forming protein and allows the metabolites and irons to cross the OMM (Wolff et al., 2014). It has been shown that VDAC1-mediated mitochondrial iron uptake may accelerate ferroptosis (Yao et al., 2022).

Mitophagy and Necroptosis Crosstalk in Central Nervous System Injuries

Crosstalk between mitophagy and necroptosis has also been confirmed. In 2016, Lu et al. found that the promotion of mitophagy may represent a therapeutic target in stroke by combating necroptosis-induced cell death (Lu et al., 2016; Figure 5 and Table 3).

Mitophagy, necroptosis, and necrotic cell death

In ischemic injury models, activation of phosphoglycerate mutase family member 5 (PGAM5) downregulated RIP1/RIP3, increased cell viability, and inhibited cell necrosis, suggesting that PGAM5 protected cells from cell death by mediating RIP1/RIP3-dependent necroptosis. Furthermore, activation of PGAM5 upregulated the expression of LC3-II, TOMM22, COX IV, PINK1, and Parkin. On the other hand, knockout of PINK1 promoted ROS production and augmented necroptotic cell death, demonstrating that PGAM5 was indispensable for the process of mitophagy, which prevented necroptosis and cell death by removing ROS-producing unhealthy mitochondria (Lu et al., 2016).

Mechanisms linking mitophagy and necroptosis

Mitophagy may regulate necroptosis by modulation of ROS, which are O2-derived free radicals and non-radical species (Zhu et al., 2022a). Intracellular ROS can trigger mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening, which contributes to RIP1/RIP3/MLKL axis-mediated necroptosis (Marshall and Baines, 2014). In addition, mitochondria-derived ROS promotes autophosphorylation of RIP1, which enables RIP1 to recruit RIP3 to form the necrosome (RIP1/RIP3), initiating TNF-α-mediated necroptosis (Zhong et al., 2022). Therefore, in response to CNS injuries, unregulated ROS can activate both mitophagy and necroptosis; however, mitophagy may attenuate necroptosis through the elimination of excessive ROS.

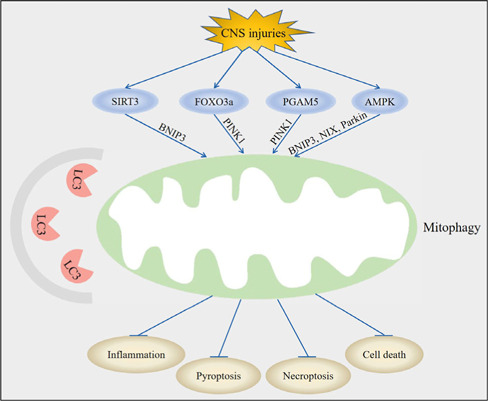

Regulators of Mitophagy in Central Nervous System Injuries

Mitophagy is crucial for mitochondrial turnover and quality control. The elimination of damaged mitochondria through mitophagy is a complicated process, which involves several molecules (Sun et al., 2022). Recently, some regulatory factors of mitophagy, such as sirtuin 3 (SIRT3), forkhead box transcription factor 3a (FOXO3a), PGAM5, and adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK), have been proposed, which can target pyroptosis and necroptosis in CNS injuries (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Upstream molecules of mitophagy-mediated pyroptosis and necroptosis in central nervous system (CNS) injuries.

Following CNS injury, regulation of sirtuin 3 (SIRT3), forkhead box transcription factor 3a (FOXO3a), phosphoglycerate mutase family member 5 (PGAM5), and adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) led to the activation of mitophagy through BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa interacting protein 3 (BNIP3), phosphatase and tensin homolog induced kinase 1 (PINK1), and NIP3-like protein X (NIX). Mitophagy subsequently inhibits inflammation, suppresses pyroptosis, decreases necroptosis, and attenuates cell death post-CNS injury. Created with Adobe Photoshop CS4.

SIRT3

SIRT3 is a mitochondrial nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD)-dependent deacetylase, which regulates the mitochondrial network by modulating lysine acetylation. SIRT3 plays a pivotal role in regulating mitochondrial function and biosynthetic pathways including energy metabolism, ROS clearance, inflammatory damage, apoptosis, and glucose and fatty acid metabolism (Zhou et al., 2022). SIRT3 participates in the occurrence and development of various CNS injuries. For example, intermittent fasting (IF) reduced neuroinflammation in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) through the activation of SIRT3 (Dai et al., 2022). Furthermore, rapamycin ameliorated brain damage and maintained the mitochondrial dynamic balance in diabetic rats subjected to cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury through an increase in SIRT3 expression (Hei et al., 2023).

SIRT3 can facilitate mitophagy and inhibit pyroptosis in CNS injuries. It has been shown that dexmedetomidine (Dex) decreased the expression levels of NLRP3, cleaved caspase-1, pro-caspase-1, ASC, and GSDMD in the hippocampus following HIR. This was consistent with the results of NLRP3 immunohistochemical staining and decreased secretion of IL-1β and IL-18, suggesting that Dex could suppress pyroptosis. In contrast, Dex induced an increase in mitophagy-related proteins, including BINP3, LC3-II/LC3-I, and p62. Additionally, transmission electron microscopy revealed that the number of mitophagosomes were increased following Dex treatment, indicating that Dex enhanced mitophagy. Treatment with 3-MA reversed the inhibitory effect of Dex on pyroptosis, demonstrating that Dex suppressed pyroptosis by activation of mitophagy in the hippocampus. Furthermore, Dex increased the expression levels of SIRT3. Treatment with 3-TYP, a specific inhibitor of SIRT3, reversed the induction of mitophagy through a downregulation of the expression levels of BINP3, LC3-II/LC3-I, and p62, suggesting that Dex ameliorated pyroptosis and hippocampal injury induced by HIR via the activation of SIRT3-mediated mitophagy (Yu et al., 2020).

How SIRT3 regulates mitophagy has not been fully explained. SIRT3 has been reported to indirectly regulate the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)/cAMP-response element binding protein (CREB)/BNIP3 pathway to induce mitophagy (Li et al., 2018). Activated CREB might act as a transcriptional co-activator, interacting with SIRT3 in the nucleus, and is closely associated with the binding of SIRT3 to the BNIP3 gene promoter region, indicating an epigenetic action of CREB for BNIP3 mRNA transcription (Nahalkova, 2022). Recent studies have suggested that SIRT3 could directly bind to and deacetylate PINK1/Parkin to facilitate mitophagy. For example, Wang et al. (2019) reported that metformin could serve as an activator of the SIRT3/PINK1/Parkin signaling pathway to counteract IL-1β-induced oxidative stress and the imbalance of anabolism and catabolism in chondrocytes. Furthermore, in a rat refeeding syndrome (RFS) model, downregulation of SIRT3 modulated myocardial injury by suppressing the PINK1/Parkin pathway (Li et al., 2022a). In addition to the direct deacetylation of PINK1, adenine nucleotide translocator 1 (ANT1) may be involved in the crosstalk between SIRT3 and the PINK1/Parkin pathway. ANT1 can protect PINK1 from degradation and maintain mitophagy by binding to translocase of inner mitochondrial membrane 44 (Hoshino et al., 2019). Meanwhile, SIRT3 can decrease acetylation of cyclophilin D and suppress the binding of cyclophilin D to ANT1, promoting the function of ANT1 and activation of mitophagy (Yang et al., 2022d). Therefore, we speculate that the mechanism by which SIRT3 mediates mitophagy may be related to the regulation of PINK1 and ANT1 in CNS injuries; however, further studies are required to confirm this.

FOXO3a

FOXO3a is a member of the FOXO transcription factor family and was originally identified in human placental cosmid (Wang et al., 2022a). FOXO3a plays an evolutionarily conserved role in the control of many biological processes, including DNA damage, apoptosis, and cell cycle regulation (Zhang et al., 2022c). Disorders of FOXO3a also contribute to the development of numerous diseases, including CNS injuries. Tan et al. (2021) found that syringin exerted a protective effect against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury by reducing inflammation; this effect was mediated by the FOXO3a/NF-κB pathway. In addition, Zhang et al. (2020) proposed that the activity of FOXO3a was highly sensitive to hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) exposure and that FOXO3a plays important roles in protecting against CNS oxygen toxicity via activation of the antioxidative signaling pathway.

FOXO3a can also promote mitophagy to inhibit pyroptosis in CNS injuries. In neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain damage, MSC-exos decreased the expression of NLRP3, cleaved caspase-1, and GSDMD-N, as well as the release of IL-1β and IL-18 in OGD/R-exposed BV-2 cells. MSC-exos also increased the expression of the mitophagy markers TOMM20 and COX IV. Additionally, both 3-MA and Mdivi-1 attenuated the inhibition of pyroptosis by treatment with MSC-exos, indicating that MSC-exos suppress pyroptosis by promoting mitophagy. Furthermore, MSC-exos upregulated the expression of FOXO3a; however, FOXO3a siRNA partially mitigated MSC-exos-induced inhibition of mitophagy and pyroptosis, showing that MSC-exos enhanced mitophagy to protect cells from pyroptosis through the regulation of FOXO3a (Hu et al., 2021).

The mechanisms of how FOXO3a regulates mitophagy remain unclear. Previous studies have shown that FOXO3a can bind to the HSP90 promoter region to increase to expression of HSP90. Upregulation of HSP90 can activate Unc-51 like autophagy activating kinase 1 (ULK1), further promoting FUNDC1-mediated mitophagy (Lu et al., 2022a). Furthermore, deacetylated FOXO3a can induce mitophagy by promoting the expression of BNIP3, which protects cells from mitochondrial dysfunction (He et al., 2021). In addition, FOXO3a regulates PINK1 and Parkin expression at the transcriptional level, resulting in the activation of mitophagy (Gupta et al., 2022). However, whether PINK1/Parkin, BNIP3, PGC-1α, and FUNDC1 are involved in FOXO3a-mediated mitophagy in CNS injuries remains an interesting point for us to investigate in the future.

PGAM5

PGAM5 belongs to the PGAM family and functions as a Ser/Thr protein phosphatase in the mitochondria. PGAM5 can regulate mitochondrial dynamics, including mitochondrial fission, movement, biogenesis, and mitophagy (Liang et al., 2021). Recent studies have indicated that PGAM5 is associated with the progression of CNS injuries. Chen et al. (2021b) evaluated the effects of PGAM5 on neurological deficits and neuroinflammation in TBI models. They found that PGAM5 worsened neurological outcomes after TBI, which might be a potential therapeutic target to decrease neuroinflammation (Chen et al., 2021b). Furthermore, in primary cortical neurons injured by mechanical equiaxial stretching, knockdown of PGAM5 alleviated neuronal injury and neuroinflammation via dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) activation-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction (Chen et al., 2021a).

The effects of PGAM5 on mitophagy and PCD following CNS injury have been reported. Lu et al. (2016) showed that PGAM5 can increase the number of double-membrane autophagosomes with encapsulated mitochondria and upregulate the expression of mitophagy markers, including PINK1, LC3-II, COX IV, and TOMM22, suggesting that PGAM5 induced PINK1-mediated mitophagy. Furthermore, PGAM5 decreased the RIP1/RIP3/MLKL complex, preventing necroptosis. Loss of PGAM5 attenuated PINK1-mediated mitophagy, resulting in the accumulation of abnormal mitochondria, excessive ROS, and aggravated necroptosis, indicating that PGAM5 protects cells from necroptosis by the regulation of mitophagy (Lu et al., 2016).

To date, some explanations have been proposed to illustrate how PGAM5 mediates mitophagy. Because both PGAM5 and PINK1 are cleaved by PARL, PGAM5 may compete with PINK1 for PARL (Lysyk et al., 2021). In healthy mitochondria, PINK1 is degraded by PARL; however, in damaged mitochondria, the level of PGAM5 is increased, and PARL cleaves PGAM5 instead of PINK1, thus stabilizing PINK1 and activating PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy (Yan et al., 2020). PGAM5 is also involved in PINK1-independent mitophagy by forming a dodecamer and dephosphorylating the mitophagy receptor FUNDC1 to enhance mitophagy (Ma et al., 2020).

AMPK

AMPK, a highly conserved Ser/Thr protein kinase, regulates metabolic homeostasis and energy balance by serving as an energy sensor (Saito et al., 2019). AMPK exerts protective effects in brain cellular homeostasis following insult via various cellular processes, such as energy metabolism, oxidative stress, cell death, autophagy, mitochondrial function, and inflammation (Appunni et al., 2021). For example, AMPK is stimulated by a decline in the ATP concentration, increasing the AMP/ATP ratio during ischemic stroke (Zhang et al., 2022e). In response to hypoxia-ischemia, AMPK expressed in microglia plays crucial roles in promoting M2 polarization of macrophages/microglia (Chu et al., 2019).

AMPK was also shown to participate in mitophagy-mediated pyroptosis in CNS injuries. In a mouse model of SCI, betulinic acid (BA) decreased the expression of caspase-1 and GSDMD, as measured by immunofluorescence staining, and inhibited the expression of ASC, GSDMD, caspase-1, NLRP3, IL-1β, and IL-18, as assessed by Western blotting, suggesting that BA could attenuate SCI-induced pyroptosis. In addition, treatment of BA further enhanced the level of BNIP3, NIX, Parkin, LC3-II, Beclin-1, Vps34, and cathepsin D, and decreased the level of p62 compared with SCI. On the other hand, inhibition of autophagy by 3-MA reversed the inhibitory effect of BA on pyroptosis, indicating that BA alleviated pyroptosis in SCI due to its mitophagy enhancing effects. Further mechanistic studies revealed that BA activated AMPK, and inhibition of AMPK by compound C led to the diminished effects of BA on mitophagy and pyroptosis. These data indicate that BA could significantly promote recovery following SCI through the activation of AMPK, which enhances mitophagy and subsequently inhibits pyroptosis (Wu et al., 2021).

AMPK is a classic metabolism-related target and it can mediate mitophagy in response to various cellular stresses (Li and Chen, 2019). A direct link between AMPK and mitophagy was established when it was shown that AMPK was able to upregulate the transcription of BNIP3/NIX (Li et al., 2020). AMPK can directly phosphorylate ULK1 and Parkin. Immediately following mitochondrial depolarization, AMPK is fully activated and directly phosphorylates its substrate raptor ULK1. ULK1 then phosphorylates Parkin at Ser108 in its nine amino acid activation element, initiating mitophagy, demonstrating that AMPK/ULK1-mediated phosphorylation of the Parkin activation domain triggered an early step in mitophagy (Hung et al., 2021). Interestingly, AMPK can also promote mitochondrial fission and drive mitophagy in a PINK1/Parkin-independent manner. AMPK initially promotes mitochondrial fission via direct phosphorylation of mitochondrial fission factor at Ser146. This allows the separation of healthy and depolarized mitochondria. In depolarized mitochondria, AMPK induces TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) phosphorylation via ULK1. The activation of TBK1 enhances the binding of autophagy receptors, such as calcium binding and coiled-coil domain 2 (CALCOCO2) and optineurin (OPTN), to the ubiquitylated mitochondria, facilitating selective mitochondrial autophagy (Seabright et al., 2020). Furthermore, the AMPK/mTOR/transcription factor EB (TFEB) pathway can also activate mitophagy. AMPK firstly inhibits the phosphorylation of mTOR, resulting in the activation of mTOR, which then promotes the release of Ca2+ to activate calcineurin. Calcineurin further promotes the nuclear translocation of TFEB. Finally, TFEB facilitates mitophagy through enhancing Parkin recruitment to the mitochondria (Wu et al., 2021).

Limitations and Concluding Remarks

In this review, we summarize the role of PCD in CNS injuries, the crosstalk between PCD and CNS injuries, and the regulators of mitophagy in CNS injuries. However, we found that significant limitations exist in the current literature. Firstly, multiple PCDs usually occur at the same time following CNS injury; therefore, the results of one or two PCDs do not fully explain the actual pathological processes of CNS injuries. Secondly, although the role of PCD in CNS injuries has been fully explained, the detailed regulatory mechanism among these PCDs have not been clarified. Thirdly, to date, almost all experiments performed have been animal or cell experiments; therefore, further studies in the clinic are urgently needed.

Recently, a novel cell death pathway named “cuprotosis” has been proposed, which differs from the known cell death pathways (e.g., apoptosis, autophagy, ferroptosis, pyroptosis; Cheng et al., 2023). As early as the 1980s, copper has been reported to cause cell death; however, the exact form of cell death caused by copper ions has remained controversial (Xie et al., 2023). In March 2022, Tsvetkov et al. determined the mechanism of copper-induced cell death, which was named “cuprotosis”. The overaccumulation of copper ions leads to the abnormal aggregation of lipoacylated proteins, which interferes with mitochondrial respiration related iron-sulfur cluster proteins, causing protein toxic stress reactions and ultimately resulting in cell death. At this point, there has been a new breakthrough in the study of the mechanism of cuprotosis (Tsvetkov et al., 2022). In addition, except for copper chelating agent, all of the available apoptosis, necrotic apoptosis, ROS, and ferroptosis inhibitors could not rescue cuprotosis (Chen et al., 2022a). The mechanisms of cuprotosis include copper ion carrier-induced cell death and copper homeostasis disorder-induced cell death (Ren et al., 2022). (1) Copper ion carrier-induced cell death: when copper ions accumulate in cells dependent on mitochondrial respiration (copper ions are transported into cells through copper ion carriers), they combine with lipoacylated dihydrolipoamide S-acetyltransferase (DLAT) to induce heteropolymerization of DLAT. The increase in insoluble DLAT leads to cytotoxicity and induces cell death (Ren et al., 2022). (2) Copper homeostasis disorder-induced cell death: The steady-state of copper mainly relies on three copper transport proteins, SLC31A1, ATP7A/B, and SLC31A1. SLC31A1 is responsible for copper uptake, while ATP7A and ATP7B are responsible for copper transport. The mechanism of cell death caused by copper homeostasis imbalance is consistent with that induced by copper ion carriers (Ren et al., 2022). However, thus far, cuprotosis has not been explored in CNS injuries. Further studies are needed to explain the role of cuprotosis in CNS injuries, in addition to the crosstalk between cuprotosis and other PCDs in CNS injuries.

Future research should clarify the pathophysiological mechanism of CNS injuries, explore effective therapeutic targets, and perform prospective clinical trials. We believe that targeting PCDs could be an attractive therapeutic strategy to achieve more favorable outcomes in patients suffering from CNS injuries.

Funding Statement

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 82101461 (to ZL).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement: Not applicable.

C-Editors: Zhao LJ, Zhao M; S-Editor: Li CH; S-Editors: Li CH, Song LP; T-Editor: Jia Y

References

- Al Mamun A, Suchi SA, Aziz MA, Zaeem M, Munir F, Wu Y, Xiao J. Pyroptosis in acute pancreatitis and its therapeutic regulation. Apoptosis. 2022;27:465–481. doi: 10.1007/s10495-022-01729-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appunni S, Gupta D, Rubens M, Ramamoorthy V, Singh HN, Swarup V. Deregulated protein kinases: friend and foe in ischemic stroke. Mol Neurobiol. 2021;58:6471–6489. doi: 10.1007/s12035-021-02563-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H, Lin C, Li Z, Shen Y, Zhang G, Mao L, Ma C, Liu N, Lu H. T3 alleviates neuroinflammation and reduces early brain injury after subarachnoid haemorrhage by promoting mitophagy via PINK 1-parkin pathway. Exp Neurol. 2022;357:114175. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2022.114175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Jin H, Xu H, Peng Y, Jie L, Xu D, Chen L, Li T, Fan L, He P, Ying G, Gu C, Wang C, Wang L, Chen G. The neuroprotective effects of necrostatin-1 on subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats are possibly mediated by preventing blood-brain barrier disruption and RIP3-mediated necroptosis. Cell Transplant. 2019;28:1358–1372. doi: 10.1177/0963689719867285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Min J, Wang F. Copper homeostasis and cuproptosis in health and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022a;7:378. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-01229-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Gong K, Xu Q, Meng J, Long T, Chang C, Wang Z, Liu W. Phosphoglycerate mutase 5 knockdown alleviates neuronal injury after traumatic brain injury through Drp1-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2021a;34:154–170. doi: 10.1089/ars.2019.7982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Tang W, Huang X, An Y, Li J, Yuan S, Shan H, Zhang M. Mitophagy in intracerebral hemorrhage: a new target for therapeutic intervention. Neural Regen Res. 2024;19:316–323. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.379019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Gong K, Guo L, Zhang B, Chen S, Li Z, Quanhua X, Liu W, Wang Z. Downregulation of phosphoglycerate mutase 5 improves microglial inflammasome activation after traumatic brain injury. Cell Death Discov. 2021b;7:290. doi: 10.1038/s41420-021-00686-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YX, Zuliyaer T, Liu B, Guo S, Yang DG, Gao F, Yu Y, Yang ML, Du LJ, Li JJ. Sodium selenite promotes neurological function recovery after spinal cord injury by inhibiting ferroptosis. Neural Regen Res. 2022b;17:2702–2709. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.339491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng B, Tang C, Xie J, Zhou Q, Luo T, Wang Q, Huang H. Cuproptosis illustrates tumor micro-environment features and predicts prostate cancer therapeutic sensitivity and prognosis. Life Sci. 2023;325:121659. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2023.121659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu CT. Multiple pathways for mitophagy: A neurodegenerative conundrum for Parkinson's disease. Neurosci Lett. 2019;697:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu X, Cao L, Yu Z, Xin D, Li T, Ma W, Zhou X, Chen W, Liu D, Wang Z. Hydrogen-rich saline promotes microglia M2 polarization and complement-mediated synapse loss to restore behavioral deficits following hypoxia-ischemic in neonatal mice via AMPK activation. J Neuroinflammation. 2019;16:104. doi: 10.1186/s12974-019-1488-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung J, Anderson SA, Gwynn B, Deck KM, Chen MJ, Langer NB, Shaw GC, Huston NC, Boyer LF, Datta S, Paradkar PN, Li L, Wei Z, Lambert AJ, Sahr K, Wittig JG, Chen W, Lu W, Galy B, Schlaeger TM, et al. Iron regulatory protein-1 protects against mitoferrin-1-deficient porphyria. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:7835–7843. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.547778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coll RC, Schroder K, Pelegrin P. NLRP3 and pyroptosis blockers for treating inflammatory diseases. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2022;43:653–668. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2022.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai S, Wei J, Zhang H, Luo P, Yang Y, Jiang X, Fei Z, Liang W, Jiang J, Li X. Intermittent fasting reduces neuroinflammation in intracerebral hemorrhage through the Sirt3/Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. J Neuroinflammation. 2022;19:122. doi: 10.1186/s12974-022-02474-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degterev A, Huang Z, Boyce M, Li Y, Jagtap P, Mizushima N, Cuny GD, Mitchison TJ, Moskowitz MA, Yuan J. Chemical inhibitor of nonapoptotic cell death with therapeutic potential for ischemic brain injury. Nature Chem Biol. 2005;1:112–119. doi: 10.1038/nchembio711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goiran T, Eldeeb MA, Zorca CE, Fon EA. Hallmarks and molecular tools for the study of mitophagy in Parkinson's disease. Cells. 2022;11:2097. doi: 10.3390/cells11132097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta P, Sharma G, Lahiri A, Barthwal MK. FOXO3a acetylation regulates PINK1, mitophagy, inflammasome activation in murine palmitate-conditioned and diabetic macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 2022;111:611–627. doi: 10.1002/JLB.3A0620-348RR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X, Xu T, Fang Q, Zhang H, Yue L, Hu G, Sun L. Quercetin hinders microglial activation to alleviate neurotoxicity via the interplay between NLRP3 inflammasome and mitophagy. Redox Biol. 2021;44:102010. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2021.102010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao M, Han X, Yao Z, Zhang H, Zhao M, Peng M, Wang K, Shan Q, Sang X, Wu X, Wang L, Lv Q, Yang Q, Bao Y, Kuang H, Zhang H, Cao G. The pathogenesis of organ fibrosis: Focus on necroptosis. Br J Pharmacol. 2022a doi: 10.1111/bph.15952. doi: 10.1111/bph.15952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao Y, Ou Y, Zhang C, Chen H, Yue H, Yang Z, Zhong X, Hu W, Sun P. Seratrodast, a thromboxane A2 receptor antagonist, inhibits neuronal ferroptosis by promoting GPX4 expression and suppressing JNK phosphorylation. Brain Res. 2022b;1795:148073. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2022.148073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]