Abstract

Introduction

The complex practice environment and responsibilities incumbent on diagnostic radiologists creates a workflow susceptible to disruption. While interruptions have been shown to contribute to medical errors in the healthcare delivery environment, the exact impact on highly subspecialized services such as diagnostic radiology is less certain. One potential source of workflow disruption is the use of a departmental instant messaging system (Webex), to facilitate communications between radiology faculty, residents, fellows, and technologists. A retrospective review was conducted to quantify the frequency of interruption experienced by our neuroradiology fellows.

Materials and Methods

Data logs were gathered comprising all instant messages sent and received within the designated group chats from July 5 – December 31, 2021, during weekday shifts staffed by neuroradiology fellows. Interruptions per shift were calculated based on month, week, and day of the week.

Results

14,424 messages were sent across 289 total shifts. The 6 fellows assigned to the main neuroradiology reading room sent 3,258 messages and received 10,260 messages from technologists and other staff. There was an average of 50 interruptions per shift when examined by month (range 48 – 53), and 52 interruptions per shift when examined by day of the week (range 40 – 60).

Conclusion

Neuroradiology fellows experience frequent interruptions from the departmental instant messaging system. These disruptions, when considered in conjunction with other non-interpretative tasks, may have negative implications for workflow efficiency, requiring iterative process improvements when incorporating new technology into the practice environment of diagnostic radiology.

Keywords: workflow, interruptions, diagnostic radiology, instant messaging

Precis

The introduction of new modes of clinical communication in the diagnostic workflow environment may have complex implications on workflow efficiencies.

INTRODUCTION

More than two decades after the initial publication of the Institute of Medicine’s formative report To Err is Human, patient safety remains a crucial and exhaustively studied area of medicine. While there have been quantifiable improvements in many sectors of patient safety, the rapid advancements of both medical and information technology have created an increasingly complex healthcare delivery environment [1]. This complexity is particularly salient within the field of radiology as the use of imaging studies has grown faster than any other medical service [2]. This exponential rise in the number of imaging studies has led to a more than 10-fold increase in the amount of data managed daily by radiologists [2], with more than 1 billion examinations completed each year [3].

The complex practice environment and myriad of clinical responsibilities incumbent on diagnostic radiologists, in conjunction with increasing volumes, creates workflows that are uniquely susceptible to disruption. Workflow interruptions have been shown to be a major contributor to medical errors [4,5]. Controlled laboratory experiments on cognition have also demonstrated that interruptions are a detriment to complex tasks involving high cognitive loads [6–10]. This has also been exhaustively studied within the hospital setting, with prior research examining interruptions within the nursing environment [11–14] operating room [15–17] and physician workflow [18–20]. In radiology, non-image-interpretive tasks (NITs) and task-switching events (TSEs) are an inherent component of a standard workday and include tasks such as answering phone calls, examination protocoling, responding to pages, communicating key findings to treatment teams, and handling physician consults. Work from our team has shown that NITs constitute a large portion of a radiologist’s workday, while radiologists also encounter nearly 15 TSEs every hour [21]. Similar research has demonstrated that phone calls are one of the most frequent interruptions to the workflow of on-call radiologists [22]. These interruptions, while important to the practice of radiology, ultimately detract from the radiologist’s image-interpretive responsibilities. Furthermore, despite efforts from our team and others, the exact impact of these disruptions on the workflow of radiologists and their potential causal role in both diagnostic error and patient harm remain less clear.

To reduce the number and effect of interruptions within the reading room, our clinical service has spearheaded the implementation of several workflow changes, such as hiring full-time reading room assistants and implementing new communication platforms such as instant messaging. These instant messaging tools have rapidly emerged as an asynchronous and potentially more efficient communication method allowing for facile communication between radiologists in the various neuroradiology reading rooms and imaging technologists. However, as these emerging asynchronous communication tools become widely deployed, an understanding of how frequently these tools are used and their potential impact on clinical workflows remain unknown. To address this gap in knowledge, we designed a retrospective study to quantify the baseline usage statistics of an instant messaging platform at our institution and the potential number of disruptions encountered by clinical trainees as a result of this new mode of communication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

An instant messaging system was implemented into clinical workflows at our institution beginning July 1, 2020 (Webex, Cisco, San Jose, CA). Instant messaging logs of messages sent to and from the neuroradiology fellows staffed to our main neuroradiology reading room from July 5, 2021, to December 31, 2021, were collected. To address potential confounding factors related to the adoption of a clinical instant messaging systems, there is a 1-year gap between messaging system implementation and data collection. Instant messaging logs of messages sent to and from the neuroradiology fellows staffed to our main neuroradiology reading room from July 5, 2021, to December 31, 2021, were collected. This includes the primary neuroradiology reading room fellow staffed to the main reading room each workday as well as the call (‘Niner’) fellow, who staffs the room from 1200–2100 hours in the main neuroradiology reading room (Monday-Wednesday). Each of our institution’s five neuroradiology fellows (four first-year fellows and one second-year fellow) rotated through each of these two staffing roles during the data collection period.

Messages incorporated in our study include only those sent Monday–Wednesday between the hours of 0600–2100, and Thursday–Friday between the hours of 0600 – 1800, corresponding to hours when the main neuroradiology reading room is staffed by fellows in these lead interpretative roles. Weekend shifts as well as the Thursday and Friday “niner” shifts are covered by senior residents; therefore messages sent during these timeframes were excluded as a neuroradiology fellow would not have answered these messages. Messages sent on holidays were also excluded as holiday practice patterns and fellow and attending staffing are variable on those days.

Messages were obtained from the three primary neuroradiology chat spaces: “Neuroradiology Main RR,” “Neuroradiology CT,” and “Neuroradiology MRI.” All messages sent through these three chat spaces from radiology technologists, attending physicians, fellows assigned to alternate neuroradiology rotations, residents, and other staff were included. All messages sent from the main reading room fellows, either as a primary message or a response to a previous chat thread, were also included.

Data were collected and analyzed using Microsoft Excel version 16.6 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington). Total number of primary reading room and “niner” shifts were calculated for each of the five neuroradiology fellows. Interruptions per shift, defined as messages sent or received by the main reading room neuroradiology fellow(s), were calculated based on month, week, and day of the week. Interruptions were also calculated based on time of day (i.e. 0600–1000, 1000–1200, 1200–1500, 1500–1800, and 1800–2100 hours).

RESULTS

During the approximately 26-week period of data collection, a total of 14,424 messages were sent across 289 total shifts. There were 212 standard daytime shifts and 77 “niner” shifts. The five neuroradiology fellows assigned to the main reading room sent 3,258 messages and received 10,260 messages from technologists and other staff. There was a significant range in the number of messages sent by each neuroradiology fellow, ranging from 242 to 932.

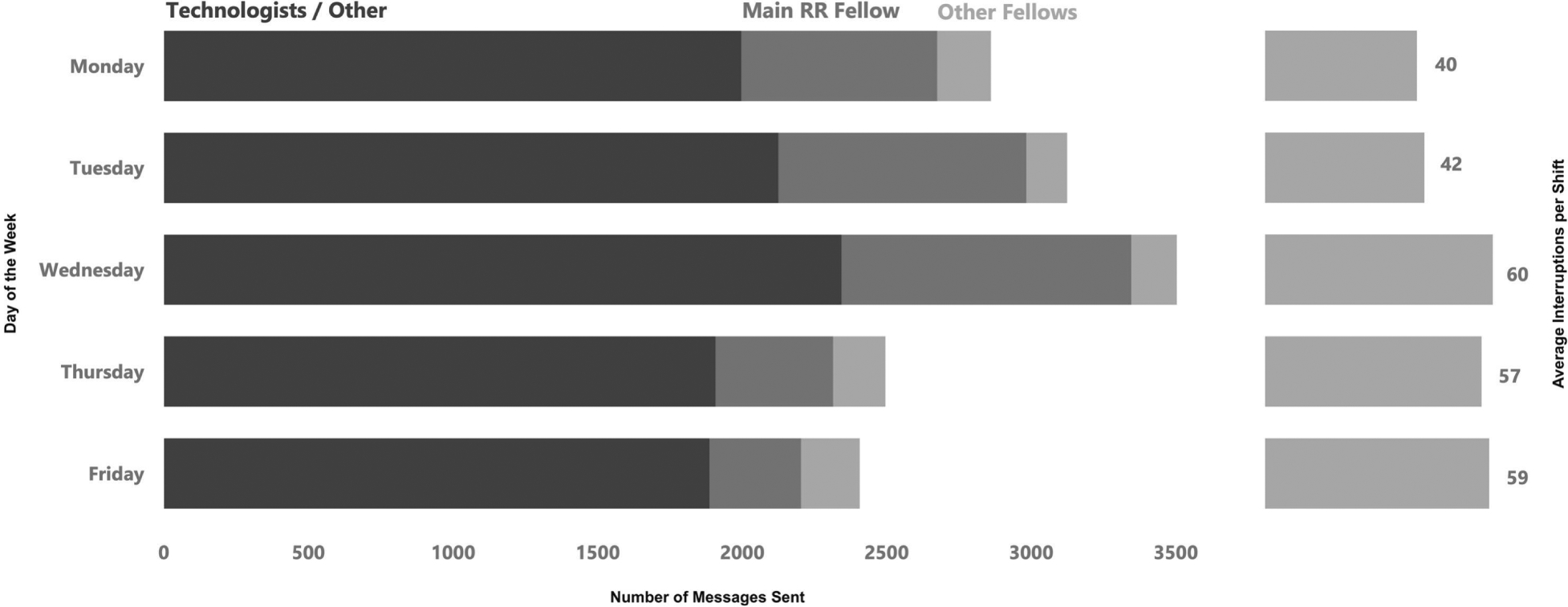

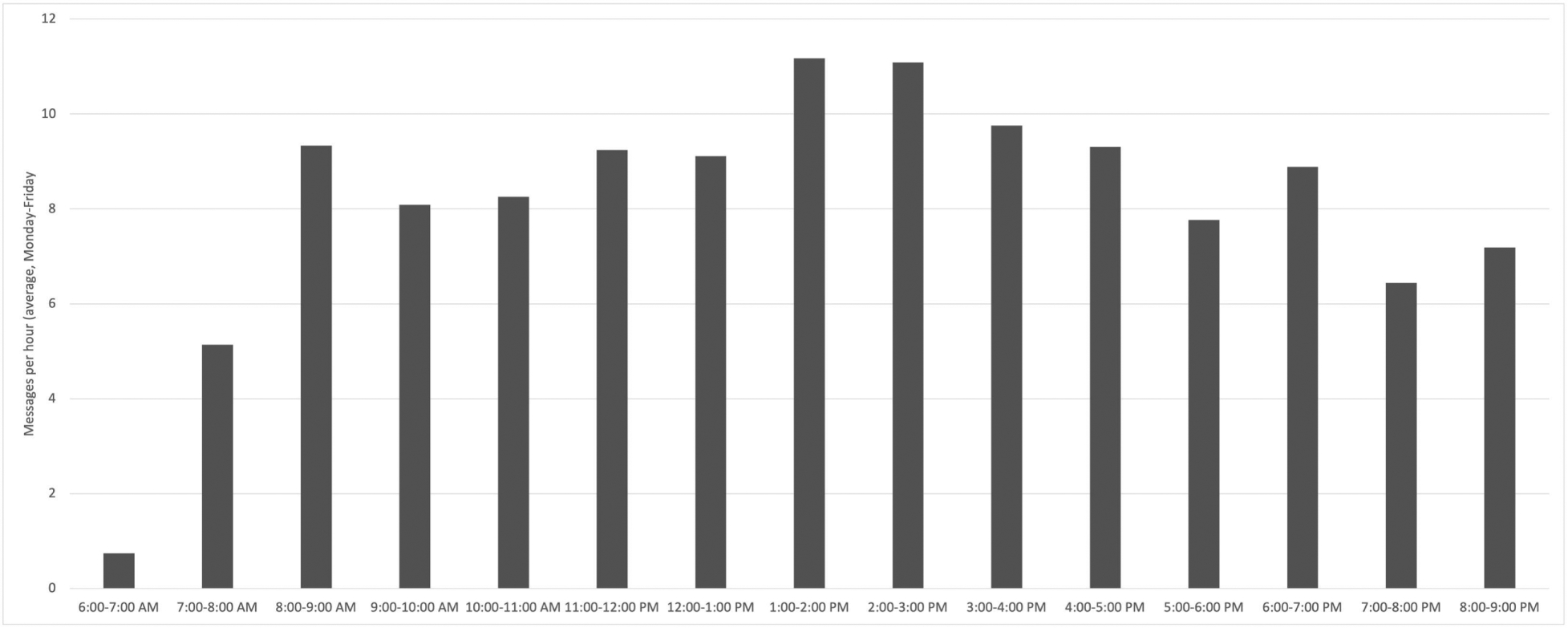

When examined by time of day, the highest number of messages were exchanged between the hours of 1200–1500 with 3900 total messages sent and received. The fewest messages were exchanged between the hours of 1800–2100, with 1942 total messages. When examined by day of the week, the highest number of messages were exchanged on Wednesdays with 3540, compared to 2406 messages sent and received on Fridays.

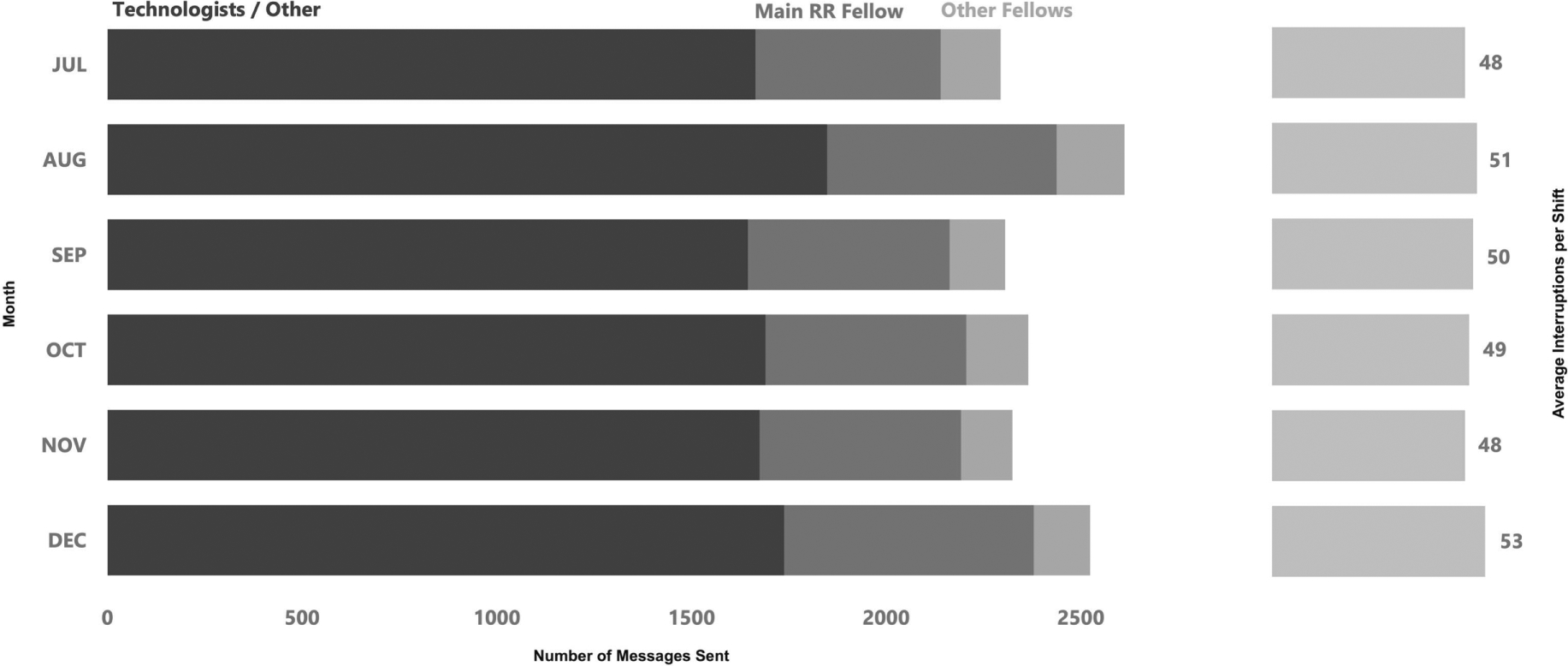

Each instant message (either sent or received) is defined as an ‘interruption.’ There was an average of 50 interruptions per shift when examined by month, ranging from 48 interruptions per shift in July and 53 interruptions per shift in December (Fig 1). Similarly, there was an average of 52 interruptions per shift when examined by day of the week, ranging from 40 interruptions per shift on Mondays and 60 interruptions per shift on Wednesdays (Fig 2). The number of messages sent and received per hour was also calculated (Fig. 3). Interruptions per shift when examined by week demonstrated relatively more variance, with an average of 50 interruptions per shift but a range of 32 (week 1) up to 69 (week 26).

Fig 1.

Interruptions per Shift by Month. Pictorial depiction of the total number of messages sent categorized by month, with corresponding average number of interruptions per shift.

Fig 2.

Interruptions per Shift by Day of the Week. Pictorial depiction of the total number of messages sent categorized by day of the week, with corresponding average number of interruptions per shift.

Fig 3.

Instant messages per hour averaged over the work week (Monday-Friday). Pictorial depiction of the average number of messages (sent and received) per hour averaged over the work week (Monday-Friday).

DISCUSSION

The modern radiologist must effectively manage multiple responsibilities in an ever increasingly complex healthcare delivery environment. Although the practice of image interpretation remains at the forefront, the workflow of radiologists also includes relaying key imaging findings to primary physicians, examination protocoling, clinical consults, and communicating with radiology technicians and other staff. These NITs, while a crucial aspect of the practice of radiology, are also highly disruptive. Our institution implemented the instant messaging system as an asynchronous but potentially more efficient communication device to facilitate interactions between the reading rooms and the other radiology staff. We sought to characterize the frequency of NITs as a result of the new instant messaging system in an attempt to identify potential implications and areas of improvement related to an efficient workflow in our neuroradiology reading rooms.

We found that our neuroradiology fellows encountered an average of 5 task switching events (TSEs) per hour from the instant messaging system alone, corresponding to approximately one interruption every 12 minutes. As a comparison, the Vancouver Workload Utilization Evaluation Study demonstrated that attending radiologists face an average of 6 interruptions per hour, inclusive of all forms of potential interruption [23]. Further, it is likely that our neuroradiology fellows face a higher number of disruptions each hour, as the current data does not account for other forms of task-switching that might arise from incoming phone calls, performing procedures, and fielding questions from medical students and other physicians in the reading room.

Frequent disruptions and repeated task-switching are a detriment to a radiologist’s efficiency and accuracy, which in turn could be harmful to patient safety. Multiple prior studies have examined discrepancy rates for radiology trainee preliminary reports in the on-call setting, with a relatively constant 1–2% discordance when compared to the final attending interpretation [24–27]. Many of these studies explored the potential impact of study volume, trainee experience level, and the complexity of the examinations, but none of them specifically evaluated the effect of frequent interruptions. Brief interruptions in sequential tasks have been shown to be associated with an increased number of errors [28]. Therefore, it follows that disrupting a radiologist’s search pattern, a crucial component of effective practice, could lead to increased errors of omission in image interpretation. Frequent interruptions and task-switching also carry an associated increased time cost for interpreting practicing radiologists. In addition to the extra time spent to complete an NIT, the radiologist may also briefly forget which areas of the scan have already been evaluated, requiring potentially unnecessary re-review of multiple aspects of a given study [29].

Repeated interruptions within the complex practice environment of academic diagnostic radiology may also have potential negative consequences for resident and fellow education. With the ever-increasing volumes of studies, in combination with frequent interruptions, attending radiologists may feel a greater pressure to prioritize efficiency when working with trainees, possibly truncating the time spent on dedicated staff-out sessions. Although an instant messaging system appears to trade one type of interruption for another (e.g. instant messages instead of phone calls), there are notable advantages of a messaging system that we observed including more information about our patients from technologists, better clinical hand-offs, more real-time feedback and increase in overall image quality, and fewer mis-protocoled studies. Though these facets of our instant messaging system were noted, they were not explicitly studied here and remain an active area of investigation by our team. Overall, as with most technology-based solutions and innovations, the introduction of an instant messaging tool will require site-specific thoughtful and careful implementation to mitigate potential drawbacks while maximizing its benefits.

While the current data are compelling, there are several potential limitations. Our previous work showed an average of >11 TSEs per hour [21], but this study was conducted prior to the implementation of the instant messaging system. While we have demonstrated that this system a source of regular interruption, the exact impact on workflow efficiency is less clear given that many of these online interactions would have previously necessitated a phone call or in-person discussion. Further research would be needed to delineate the percentage of instant messages versus phone calls and other potential forms of disruption and to specifically to evaluate whether the instant messaging system is replacing or simply adding to the total number of interruptions. Given the retrospective nature of this study, another potential limitation is the lack of quantitative measurement of the time spent away from image interpretation as a result of the interruptions. Our prior research has demonstrated that non-interpretive tasks (NITs) comprise a substantial portion of the workflow in our academic practice setting, encompassing more than one-third (37%) of total time spent in the reading room [21]. Therefore, it would be a useful comparison to evaluate whether the implementation of the instant messaging system increased or decreased the total time a trainee spends on non-image-interpretive tasks.

CONCLUSIONS

Non-image-interpretive tasks are a crucial yet disruptive aspect of the daily practice of diagnostic radiology. To address how non-image-interpretive tasks are handled in our clinical reading room, we successfully installed and deployed an instant message asynchronous communication system at our institution. However, despite this success, our data demonstrate the potential tradeoffs incurred, with evidence that an instant messaging chat systems also possesses the capacity to introduce a substantial number of interruptions into clinical workflows. To diminish the number of interruptions potentially incurred with instant messaging, our results have informed new workflows whereby neuroradiology fellow and resident trainees are now “muted” to messages outside of their assigned work area. Our reading room assistant also now triages all messages received in the online system and sequentially assigns messages and specific tasks to the various trainees to further decrease the burden and need to continuously monitor and respond to messages. While anecdotal feedback to this new system has been overwhelmingly positive, the overall process remains under iterative refinement and development. Overall, we anticipate that this system will more equally distribute the work of completing NITs and limit task-switching by both the trainees and attending radiologists, leading to increased workplace efficiency, improved trainee education, and more effective image interpretation.

Highlights:

Instant messaging is a viable clinical communication tool in the radiology workflow environment.

Instant messaging, while replacing other modes of communication, can also be a source of significant interruptions in the clinical workflow environment.

Quality improvement processes may improve the implementation and effectiveness of an instant messaging system in diagnostic radiology reading rooms.

Funding:

J.J.Y. was supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant UL1TR002373. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts or competing interests in the work presented herein.

REFERENCES

- [1].Bates DW, Singh H. Two decades since to err is human: An assessment of progress and emerging priorities in patient safety. Health Aff 2018;37. 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bercovich E, Javitt MC. Medical Imaging: From Roentgen to the Digital Revolution, and Beyond. Rambam Maimonides Med J 2018;9. 10.5041/rmmj.10355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bruno MA, Walker EA, Abujudeh HH. Understanding and Confronting Our Mistakes: The Epidemiology of Error in Radiology and Strategies for Error Reduction. RadioGraphics 2015;35:1668–76. 10.1148/rg.2015150023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hickam DH, Severance S, Feldstein A, Ray L, Gorman P, Schuldheis S, et al. The effect of health care working conditions on patient safety. 2003. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [5].Westbrook JI. Association of Interruptions With an Increased Risk and Severity of Medication Administration Errors. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:683. 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Westbrook JI, Coiera E, Dunsmuir WTM, Brown BM, Kelk N, Paoloni R, et al. The impact of interruptions on clinical task completion. Qual Saf Health Care 2010;19:284–9. 10.1136/qshc.2009.039255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Eyrolle H, Cellier J-M. The effects of interruptions in work activity: field and laboratory results. Appl Ergon 2000;31:537–43. 10.1016/S0003-6870(00)00019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Coiera E The science of interruption. BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:357–60. 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Magrabi F, Li SYW, Dunn AG, Coeira E. Challenges in Measuring the Impact of Interruption on Patient Safety and Workflow Outcomes. Methods Inf Med 2011;50:447–53. 10.3414/ME11-02-0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Parker J, Coiera E. Improving Clinical Communication: A View from Psychology. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2000;7:453–61. 10.1136/jamia.2000.0070453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sørensen EE, Brahe L. Interruptions in clinical nursing practice. J Clin Nurs 2014;23:1274–82. 10.1111/jocn.12329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Laustsen S, Brahe L. Coping with interruptions in clinical nursing-A qualitative study. J Clin Nurs 2018;27:1497–506. 10.1111/jocn.14288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lin T, Feng X, Gao Y, Li X, Ye L, Jiang J, et al. Nursing interruptions in emergency room in China: An observational study. J Nurs Manag 2021;29:2189–98. 10.1111/jonm.13372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Johnson M, Sanchez P, Langdon R, Manias E, Levett-Jones T, Weidemann G, et al. The impact of interruptions on medication errors in hospitals: an observational study of nurses. J Nurs Manag 2017;25:498–507. 10.1111/jonm.12486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kim FJ, da Silva RD, Gustafson D, Nogueira L, Harlin T, Paul DL. Current issues in patient safety in surgery: a review. Patient Saf Surg 2015;9:26. 10.1186/s13037-015-0067-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Sarker SK, Vincent C. Errors in surgery. International Journal of Surgery 2005;3:75–81. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Arora S, Hull L, Sevdalis N, Tierney T, Nestel D, Woloshynowych M, et al. Factors compromising safety in surgery: stressful events in the operating room. The American Journal of Surgery 2010;199:60–5. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Westbrook JI, Raban MZ, Walter SR, Douglas H. Task errors by emergency physicians are associated with interruptions, multitasking, fatigue and working memory capacity: a prospective, direct observation study. BMJ Qual Saf 2018;27:655–63. 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Weigl M, Müller A, Vincent C, Angerer P, Sevdalis N. The association of workflow interruptions and hospital doctors’ workload: a prospective observational study. BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:399–407. 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Rivera-Rodriguez AJ, Karsh B-T. Interruptions and distractions in healthcare: review and reappraisal. Qual Saf Health Care 2010;19:304–12. 10.1136/qshc.2009.033282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Schemmel A, Lee M, Hanley T, Pooler BD, Kennedy T, Field A, et al. Radiology Workflow Disruptors: A Detailed Analysis. Journal of the American College of Radiology 2016;13:1210–4. 10.1016/j.jacr.2016.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Yu J-PJ, Kansagra AP, Mongan J. The Radiologist’s Workflow Environment: Evaluation of Disruptors and Potential Implications. Journal of the American College of Radiology 2014;11:589–93. 10.1016/j.jacr.2013.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Dhanoa D, Dhesi TS, Burton KR, Nicolaou S, Liang T. The Evolving Role of the Radiologist: The Vancouver Workload Utilization Evaluation Study. Journal of the American College of Radiology 2013;10:764–9. 10.1016/j.jacr.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Cooper VF, Goodhartz LA, Nemcek AA, Ryu RK. Radiology Resident Interpretations of On-call Imaging Studies. Acad Radiol 2008;15:1198–204. 10.1016/j.acra.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Shah NA, Hoch M, Willis A, Betts B, Patel HK, Hershey BL. Correlation Among On-Call Resident Study Volume, Discrepancy Rate, and Turnaround Time. Acad Radiol 2010;17:1190–4. 10.1016/j.acra.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Sistrom C, Deitte L. Factors Affecting Attending Agreement with Resident Early Readings of Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Head, Neck, and Spine. Acad Radiol 2008;15:934–41. 10.1016/j.acra.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Walls J, Hunter N, Brasher PMA, Ho SGF. The DePICTORS Study: discrepancies in preliminary interpretation of CT scans between on-call residents and staff. Emerg Radiol 2009;16:303–8. 10.1007/s10140-009-0795-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Altmann EM, Trafton JG, Hambrick DZ. Momentary interruptions can derail the train of thought. J Exp Psychol Gen 2014;143:215–26. 10.1037/a0030986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Williams LH, Drew T. Distraction in diagnostic radiology: How is search through volumetric medical images affected by interruptions? Cogn Res Princ Implic 2017;2:12. 10.1186/s41235-017-0050-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]