1. INTRODUCTION

Ocular surface complaints are common in the general population, with an estimated prevalence of 5%–30% worldwide.1,2 Traditionally, reports of ocular surface pain have been incorporated under the umbrella of dry eye (DE), which is defined as “a multifactorial disease of the ocular surface characterized by a loss of homeostasis of the tear film, and accompanied by ocular symptoms, in which tear film instability and hyperosmolarity, ocular surface inflammation and damage, and neurosensory abnormalities play etiological roles.”3 While ocular surface pain has long been attributed to tear abnormalities, nerve dysfunction is now acknowledged as another important contributor.4 Thus, a better understanding of peripheral and central contributors to ocular surface pain is needed to provide precision-based treatment algorithms to an individual patient.

When managing chronic ocular surface pain, one must consider the potential origins of pain, such as primary afferent nerves in the cornea correctly signaling information from their environment (i.e., nociceptive pain) and/or dysfunctional pathways within trigeminal regions (peripheral and/or central) sending inappropriate signals to evoke pain (i.e., neuropathic pain).4 Common sources of nociceptive pain in the eye include low tear volume, fast tear film breakup, and epithelial irregularities that can be evaluated at the slit lamp examination. The diagnosis of neuropathic pain remains a clinical one, with clues that include symptoms out of proportion to ocular surface signs5,6 and sensory hypersensitivity, such as evoked pain to wind and light.7 In fact, we have found that self-reported light sensitivity (i.e., photophobia) can be used as a screening tool for central abnormalities in the form of persistent aftersensations to a thermal stimulus applied to the forearm.8 The “anesthetic challenge” is another clinical test used to identify a potential neuropathic contribution to pain, with persistent pain after placement of an anesthetic suggestive of a central or non-ocular surface source of pain.9

Studies that directly image central pathways in individuals with chronic ocular surface pain are lacking in the literature. However, imaging techniques, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), have been useful in studying other head and facial pain conditions, including trigeminal neuralgia.10 In an event-related fMRI study on trigeminal neuralgia, tactile stimulation of trigger zones activated brain regions traditionally associated with pain, including the somatosensory cortices, cingulate cortex (CC), and anterior insula (AI) as well as the spinal trigeminal nucleus (spV) in the brainstem.10 After curative treatment by radiofrequency thermocoagulation of the Gasserian ganglion, significantly reduced activation in these central areas was noted on fMRI. Patients also reported that, while they still felt light touch over the trigger zones, the tactile stimulation no longer caused pain. These results highlight the potential of applying fMRI to the study of chronic ocular surface pain. As such, we developed a protocol to evaluate central nervous system pathways in individuals with chronic ocular surface pain with neuropathic features (i.e., photophobia, symptoms out of proportion to ocular surface signs).

2. METHODS

2.1. Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

The study was approved by the Miami Veterans Affairs (VA) and the University of Miami Institution Review Boards (IRB approvals #3011.08 and 20190340, respectively). The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and complied with the requirements of the United States Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to any study activities.

2.2. Study Population

We recruited 16 subjects who presented to the Miami VA eye clinic for yearly screening and divided them into two equal groups: patients with ocular surface pain (≥ 6 months) and those without pain (controls). This classification followed guidelines by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), which defines pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage”, and acknowledges various forms of expression of pain, including verbal descriptors.11 Given our previous data demonstrating a relationship between self-reported light sensitivity and central abnormalities,8 we also examined responses to question 1 of the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI),12 which assesses for eyes that are sensitive to light over the past week on a scale of 0 to 4 (0=none; 1=some; 2=half; 3=most; 4=all of the time). All individuals with chronic ocular pain had scores ≥ 3, while individuals without pain reported no light sensitivity (score 0, n=2) or light sensitivity some (score 1, n=5) or half of the time (score 2, n=1). Exclusion criteria for both groups included ocular diseases that could confound photophobia, such as glaucoma; use of glaucoma medications; uveitis; iris transillumination defects; retinal degeneration; and anatomic abnormalities of the cornea, conjunctiva, or eyelids. We also excluded individuals with contraindications to fMRI scanning (e.g., pregnancy, pacemaker, implanted metal device).

2.3. Questionnaires

Subjects were administered questionnaires to collect demographic and supporting health information, including age, sex, race, ethnicity, and medical history. The 15-item short form McGill Pain Questionnaire13 and a 9-item list of common descriptors for ocular surface pain symptoms were presented to each participant (Supplemental Table 1 and 2). Standardized DE questionnaires included the Dry Eye Questionnaire 5 (DEQ-5)14 and OSDI. The Neuropathic Pain Symptom Inventory-Eye (NPSI-Eye), a validated eye-centric variation of the NPSI,15 was obtained to quantify neuropathic-like eye symptoms.

2.4. Ocular Surface Evaluation

Each patient underwent a clinical exam that included (in the order performed) tear breakup time (TBUT, measured in seconds; lower values indicate less tear stability), corneal staining (graded to the National Eye Institute scale;16 higher values indicate more epithelial irregularity), and anesthetized tear production using Schirmer strips (measured by mm of wetting at 5 minutes; lower values indicate lower tear production).

2.5. fMRI Protocol

The fMRI protocol was adopted and modified from a prior study on photophobia using visual stimuli to evoke pain and identify trigeminal nociceptive and other pain-related pathways.17 In a single session, all individuals underwent 2 fMRI scans—one before and one after anesthetic instillation. During each scan, individuals were presented with two screen conditions: a resting black screen condition, which featured a white fixation cross on a black background (~0.5 lux), and a light stimulus white screen condition, which featured a black fixation cross on a white background (~65 lux). Subjects were presented with 16 episodes of the white screen, each lasting 6 seconds. To avoid anticipatory processes, the inter-stimulus interval varied between 26 and 34 seconds in 2-second increments. The scanner environment was kept dark during the entire experiment, with only a projector providing intermittent brief illumination. The first fMRI scan was performed immediately following placement of a single eye drop of artificial tears (Refresh Plus Lubricant Eye Drops, Allergan, Dublin, Ireland) in each eye, and the second fMRI scan was performed immediately following placement of a single eye drop of 0.5% proparacaine (Bausch & Lomb Inc., Bridgewater, NJ) topical anesthetic in each eye. Subjects were instructed to keep eyes open and blink normally throughout the duration of each scan.

2.6. fMRI Screen Condition Ratings

At the end of each scan, subjects rated the pain intensity experienced in their eyes when viewing either the black screen (rating at rest) or the white screen (rating to light stimulus). Pain intensity was rated via a verbal, numerical rating scale ranging from 0 (“no pain”) to 100 (“most intense pain imaginable”).

2.7. fMRI Acquisition and Processing

Please refer to Supplemental Text 1 for methodological detail regarding neuroimaging parameters and processing

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS V.28.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA) statistical package. Demographic and clinical variables between groups were compared using independent t-test or Chi-squared test, as appropriate. Significant differences in pain intensity ratings to each screen condition were analyzed between groups using independent t-test.

Measures of “evoked pain” were determined for each subject by calculating the difference in pain intensity ratings between the light stimulus and the resting condition. Pre- and post-anesthetic evoked pain scores were compared between groups using independent t-test and within groups using paired t-test.

The statistical significance for both brainstem and whole-brain group-level contrast analyses was set at a cluster-level threshold of P<0.05. Significant clusters were identified by region, and parameter estimate (PE) values of activation from each subject were extracted from significant voxels within each region. The PEs across all significant cluster-based voxels of a given region were averaged for each subject. Using Pearson correlation coefficients, averaged PE values were compared against pre-anesthetic evoked pain scores.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Subjects

A total of 16 subjects, 8 cases with chronic ocular surface pain and photophobia and 8 controls, were enrolled into the study. Demographics, questionnaire scores, and clinical parameters for all subjects are summarized in Table 1. Of all participants, eight subjects reported chronic (≥6 months) ocular surface pain symptoms, which the majority characterized as “itchiness,” “irritating,” “dryness,” and “soreness” from the 9-item list of ocular surface pain descriptors (Supplemental Table 1). Pain in cases was also described as “stabbing” and “aching” based on the short form McGill Pain Questionnaire (Supplemental Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of cases and controls.

| Cases (n=8) |

Controls (n=8) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (mean ± SD; years) | 49.9 ± 9.6 | 59.6 ± 7.7 | <0.05* |

| Sex, male % (n) | 38% (3) | 88% (7) | <0.05Ɨ |

| Race, white % (n) | 88% (6) | 38% (3) | 0.13 |

| Ethnicity, Hispanic % (n) | 50% (4) | 38% (3) | 0.61 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Diabetes mellitus % (n) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 1.00 |

| PTSD % (n) | 38% (3) | 13% (1) | 0.25 |

| Depression % (n) | 63% (5) | 75% (6) | 0.59 |

| Arthritis % (n) | 13% (1) | 0% (0) | 0.05 |

| Sleep apnea/CPAP % (n) | 25% (2) | 25% (2) | 1.00 |

| Migraine % (n) | 38% (3) | 0% (0) | 0.05 |

| Traumatic brain injury % (n) | 13% (1) | 13% (1) | 1.00 |

| Past or current smoker % (n) | 25% (2) | 88% (7) | <0.05Ɨ |

| Questionnaires | |||

| DEQ5, mean ± SD | 13.6 ± 1.8 | 10.3 ± 5.9 | 0.16 |

| OSDI-1, mean ± SD | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 0.9 ± 0.6 | <0.05* |

| OSDI total, mean ± SD | 60.8 ± 15.1 | 30.7 ± 23.6 | <0.05* |

| NPSI-Eye total, mean ± SD | 28.0 ± 16.1 | 10.6 ± 11.3 | <0.05* |

| Tear parameters ‡ | |||

| TBUT (s), mean ± SD | 7.1 ± 3.8 | 7.2 ± 3.4 | 0.98 |

| Corneal staining, mean ± SD | 0.8 ± 1.4 | 0.9 ± 1.7 | 0.88 |

| Schirmer’s (mm), mean ± SD | 8.0 ± 3.8 | 15.3 ± 8.1 | <0.05* |

n=number of subjects; SD=standard deviation; PTSD=post-traumatic stress disorder; CPAP=continuous positive airway pressure; TBUT=tear breakup time; DEQ5=Dry Eye Questionnaire-5; OSDI-1=Ocular Surface Disease Index question #1 regarding light sensitivity.

Independent t-test, P<0.05;

Chi-squared test, P<0.05;

Tear parameter means calculated based on more abnormal value in either eye. A higher corneal staining score represents more epithelial irregularity. A lower TBUT and Schirmer score represent faster tear breakup and lower tear production, respectively.

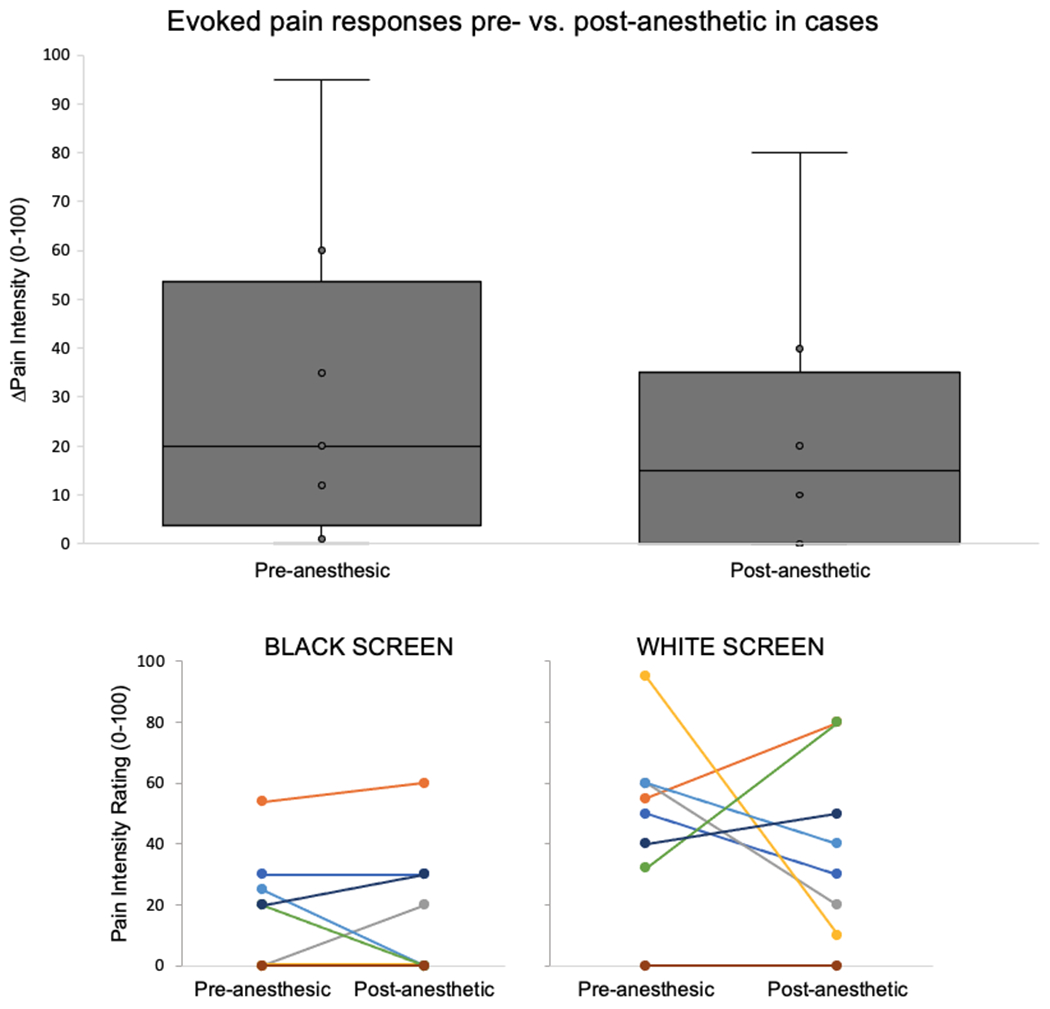

3.2. Subjective Ratings during fMRI Scanning

In cases, pre-anesthetic pain intensity ratings were significantly greater when viewing the light stimulus (white screen) vs. rest (black screen) (Mean±SD: 49.0±27.2 vs. 18.6±18.8, paired t-test t(7)=2.64, p=0.03). Post-anesthetic pain ratings in cases for the light stimulus increased vs. rest, but the change was not statistically significant (38.6±30.0 vs. 17.5±21.9, paired t-test t(7)=−2.12, p=0.07) (Figure 1). Furthermore, evoked pain scores in cases showed a decreased trend post-anesthesia vs. pre-anesthesia (post- vs. pre-anesthesia difference in evoked pain M±SD: −9.1±47.2, paired t-test t(7)= −0.55, p=0.60). Specifically, within the case group, three individuals reported decreased evoked pain to light stimulus after anesthesia, three reported increased pain, and two no change in pain.

Figure 1. Light-induced pain intensity ratings relative to rest in cases, pre- and post-anesthesia.

Cases had greater evoked pain to the light stimulus pre-anesthetic compared to post-anesthetic conditions. Cases reported variable effects in response to anesthetic on pain intensity ratings. Overall, 3 cases reported decreased, 3 increased, and 2 no change in evoked pain post- vs. pre-anesthetic.

In controls, pre-anesthetic pain intensity ratings were not significantly different during the light stimulus vs. rest (0.4±1.1 vs. 0.63±1.8, paired t-test t(7)=0.18, p=0.35).

Post-anesthetic pain ratings in controls for the light stimulus were also not statistically different (0.5±0.8 vs. 0.1±0.4, paired t-test t(7)=−1.43, p=0.20). Near zero pain scores in controls prior to anesthesia left no practical room for improvement as seen in evoked pain scores (post- vs. pre-anesthesia difference in evoked pain M±SD: 0.1±1.1, paired t-test t(7)=−0.31, p=0.72). Overall, this highlights a “floor effect” and further support the participants’ placement as controls.

3.3. Light-induced fMRI Responses in Cases vs. Controls

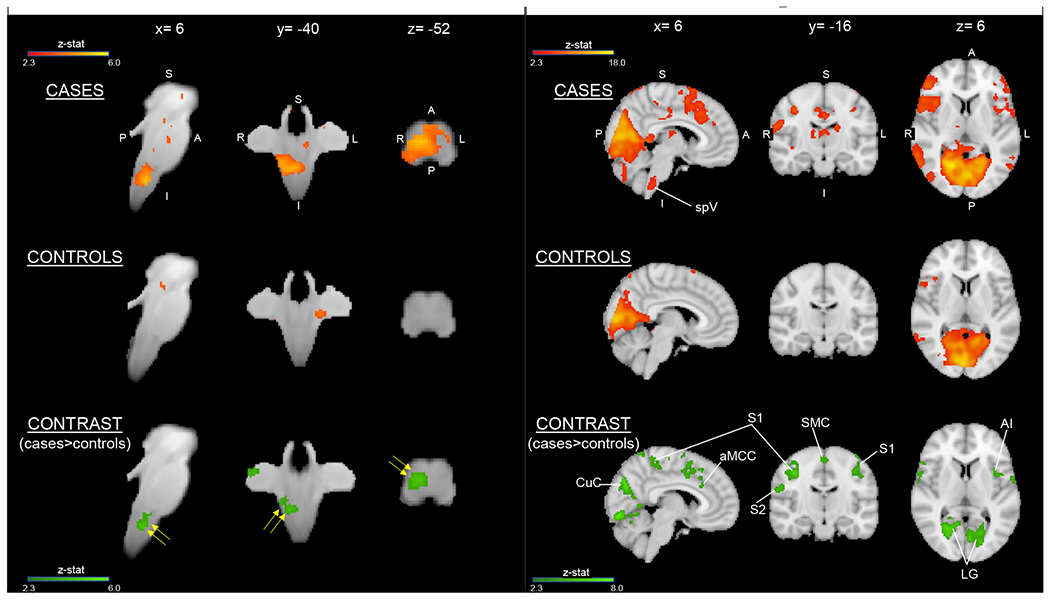

3.3.1. Brainstem Analyses

Several brainstem structures showed greater blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) responses to light in cases vs. controls prior to anesthetic placement. Specifically, cases demonstrated significantly greater activation of right spV during the light stimulus condition compared with controls (Figure 2a, Supplemental Table 3a). Post- vs. pre-anesthetic contrast analyses revealed no significant changes in brainstem activity for either group.

Figure 2.

(A) Cases had greater light-induced activation in the brainstem compared with controls before anesthetic placement. Spinal trigeminal nucleus (spV) (yellow arrows) shows greater activation in cases than in controls. Brainstem activation findings are overlaid onto the SUIT atlas with corresponding MNI coordinates. Group average activation for cases and controls (red-to-yellow) and group contrast for cases>controls (dark-to-light green) are displayed. No areas were significantly decreased in cases relative to controls. Both activation and contrast maps had an individual voxel threshold of z>2.3 and cluster-threshold of P<0.05. (B) Cases had greater light-induced activation in the whole brain compared with controls before anesthetic placement. Group average activation for cases and controls (red-to-yellow) and group contrast for cases>controls (dark-to-light green) are displayed with MNI atlas underlay. Both activation and contrast maps had an individual voxel threshold of z>2.3 and a cluster-threshold of P<0.05. spV= spinal trigeminal nucleus; S1= primary somatosensory cortex; S2= secondary somatosensory cortex; SMC= supplementary motor cortex; aMCC= anterior mid-cingulate cortex; AI= anterior insula; CuC= cuneal cortex; LG= lingual gyrus.

3.3.2. Whole Brain Analyses

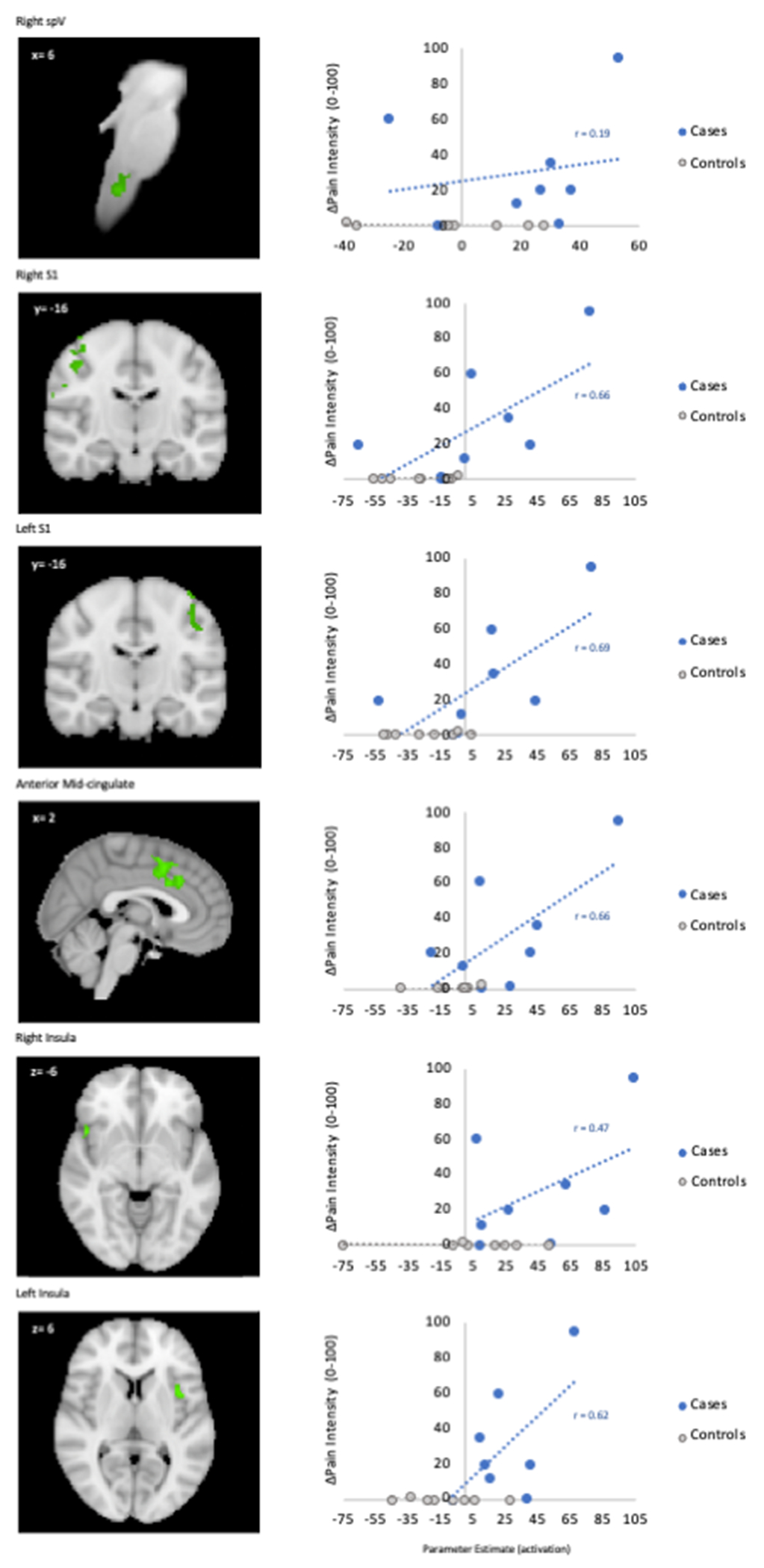

Several cortical structures showed significantly greater BOLD responses to light in cases vs. controls prior to anesthetic placement (Figure 2b, Supplemental Table 3b). Specifically, cases displayed greater activity of the visual, primary somatosensory (S1), insular, and anterior mid-cingulate (aMCC) cortices. The magnitude of BOLD activation, as reflected by PEs, was correlated with pain intensity ratings in several brain regions (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Correlations between parameter estimates of fMRI activation and light-induced pain intensity ratings in cases vs. controls before anesthetic placement.

Cases had positive correlations between light-induced pain ratings and activity in cortical areas related to pain processing. The WIKIBrainstem and Harvard-Oxford Subcortical and Cortical atlases were used to create anatomical masks of each region. Functional masks were created from group-level contrast maps to pull parameter estimates using FEAT. spV=spinal trigeminal nucleus; S1=primary somatosensory cortex.

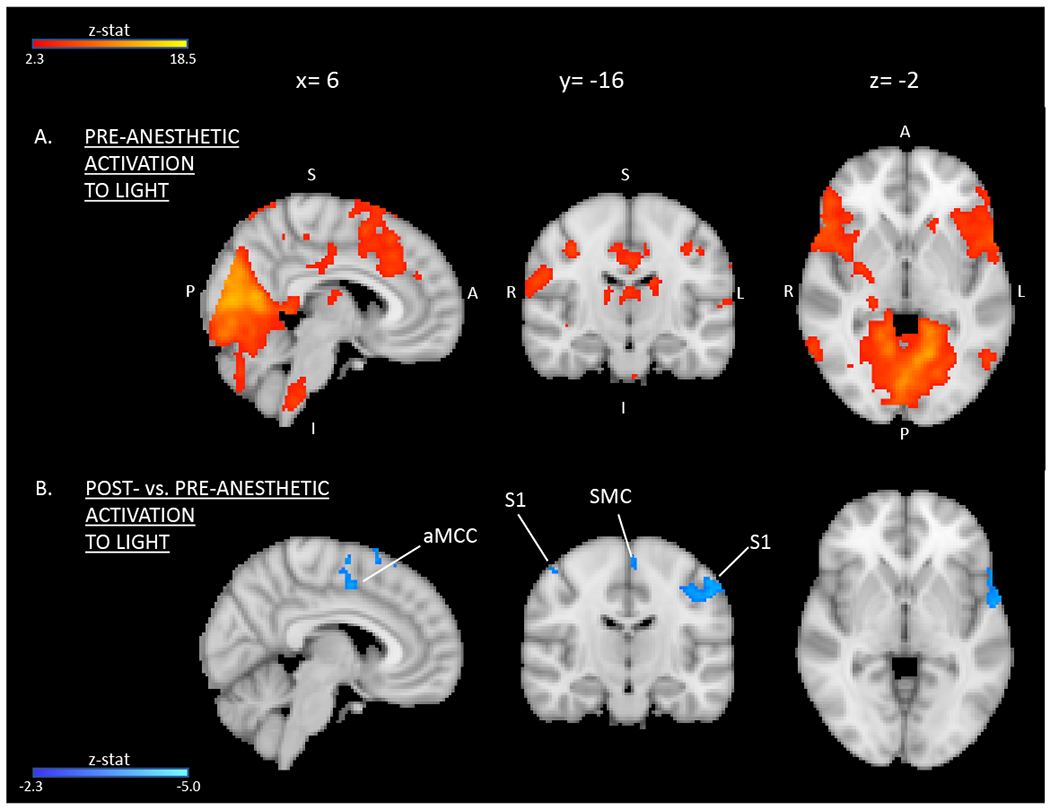

3.4. Proparacaine Decreases Light-Induced fMRI Activity in Cases

Within cases, topical anesthesia decreased activation within regions of S1 and aMCC but not in visual cortex or insula (Figure 4, Supplemental Table 4a). In controls, decreased activation following anesthesia was detected only within visual cortex (Supplemental Table 4b). Between groups, cases demonstrated increased activation relative to controls in bilateral S1 and visual cortex after anesthesia (Supplemental Table 5).

Figure 4. Light-induced activation in cases before vs. after anesthesia.

(A) Pre-anesthetic activation and (B) areas of significantly decreased activation in response to light following anesthesia at the whole-brain level. Group average activation for cases (red-to-yellow) and contrast post- vs. pre-anesthetic within cases (dark-to-light blue) are displayed with MNI atlas underlay. Both activation and contrast maps had an individual voxel threshold of z>2.3 and a cluster-threshold of P<0.05. S1= primary somatosensory cortex; SMC= supplementary motor cortex; aMCC= anterior mid-cingulate cortex.

Although decreased cortical activity was observed at the group level, changes in BOLD responses to light following anesthesia were not uniform at the individual subject level. Additionally, this nonuniformity did not correspond with the variable impact of proparacaine on light-evoked pain intensity. Table 2 shows the difference in post- vs. pre-anesthetic BOLD signal responses to light (reflected by PEs) for each case subject, as well as their corresponding change in evoked pain scores.

Table 2.

Subject-level change in post- vs. pre-anesthetic light-induced activation and evoked pain scores among cases.

| Case subject | ΔS1 | ΔaMCC | ΔEvoked pain |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −150.8 | −107.2 | ↑ |

| 2 | −145.8 | −80.4 | ↓ |

| 3 | −63.4 | −37.4 | ↓ |

| 4 | −62.0 | −28.7 | No change |

| 5 | −40.2 | −28.9 | No change |

| 6 | −38.2 | −26.3 | ↑ |

| 7 | −37.7 | −26.4 | ↑ |

| 8 | 52.2 | 12.4 | ↓ |

As a group, cases demonstrated significant decreases in S1 and aMCC activity in response to light following anesthesia. However, individual BOLD response signals (as reflected by PEs) from these regions were nonuniform and had no appreciable trend when compared to change in evoked pain scores. S1=primary somatosensory cortex; aMCC=anterior mid-cingulate cortex.

4. DISCUSSION

In this preliminary study, we found that individuals with vs. without chronic ocular surface pain and photophobia had greater activation within brain regions associated with pain processing, including structures within and beyond the trigeminal nociceptive pathway, in response to a light stimulus. Light-induced brain activation directly correlated with increases in pain intensity ratings. Although subjective pain responses after anesthetic placement varied between case individuals, reduced cortical activation was observed when examined as a group. These findings support the hypothesis that pathologic central sensitization within the trigemino-cortical nociceptive pathway contributes to photophobia in individuals with chronic ocular surface pain.

4.1. Nociceptive sources of pain lead to central pathway changes

Both nociceptive and neuropathic sources can contribute to the phenotype of chronic ocular surface pain. Apart from Schirmer’s scores (in which tear production was lower in the chronic ocular surface pain group), our cohort showed very few differences in the ocular surface parameters between chronic ocular surface pain cases and pain-free controls. Despite this, we found significantly poorer baseline measures of subjective pain at rest, as well as in response to light, among our case group. These findings are corroborated by previous reports that demonstrate how individuals with chronic ocular surface pain often perceive symptoms that are out of proportion to observed ocular surface abnormalities.18,19 When encountered in clinic, this presentation may suggest the presence of underlying nerve dysfunction.20 This is explained by “sensitization”, where an exposure to an acute or chronic adverse condition (e.g., nerve injury in the setting of surgery, environmental) induces nerve alterations that remain even after removing the triggering source20

Our findings demonstrate increased activity of central nervous structures in individuals with chronic ocular surface pain compared to controls, and are similar to a prior case report of an individual with acute ocular surface pain who underwent fMRI imaging.17 Specifically, a male with a corneal abrasion secondary to contact lens overuse underwent two fMRI sessions: one while acutely suffering from pain and photophobia and one after recovery. In response to intermittent bright light during the first session, activation was noted within the trigeminal nociceptive pathway, including spV and S1, as well as within other cortical regions, including the CC. Activation in these regions was no longer present on repeat scan after symptom resolution. Our study also identified light-induced activation of the same trigeminal pathway and cortical structures in subjects with chronic ocular surface pain. These data suggest two main points. First, in acute pain, central activation represents a noxious response, which resolves as tissue heals. And second, in chronic cases, persistent activity may indicate sensitization of pathways such that central plasticity may prime photophobia expression. Thus, as seen in our study and supported by our prior work,8 photophobia in individuals with chronic ocular surface pain may serve as a phenotypic marker of central neuroplasticity.

4.2. Trigeminal nerve involvement in photophobia-associated ocular surface pain

Innervation of the eye is primarily supplied by sensory, sympathetic, and parasympathetic afferents of the trigeminal nerve, but the effect of light exposure on pain signaling by this pathway is unclear. Further research is warranted to determine the exact details of the dysfunction as most evidence for light-mediated activation of the trigeminal system comes from animals and experimental models of chronic ocular surface pain.21,22

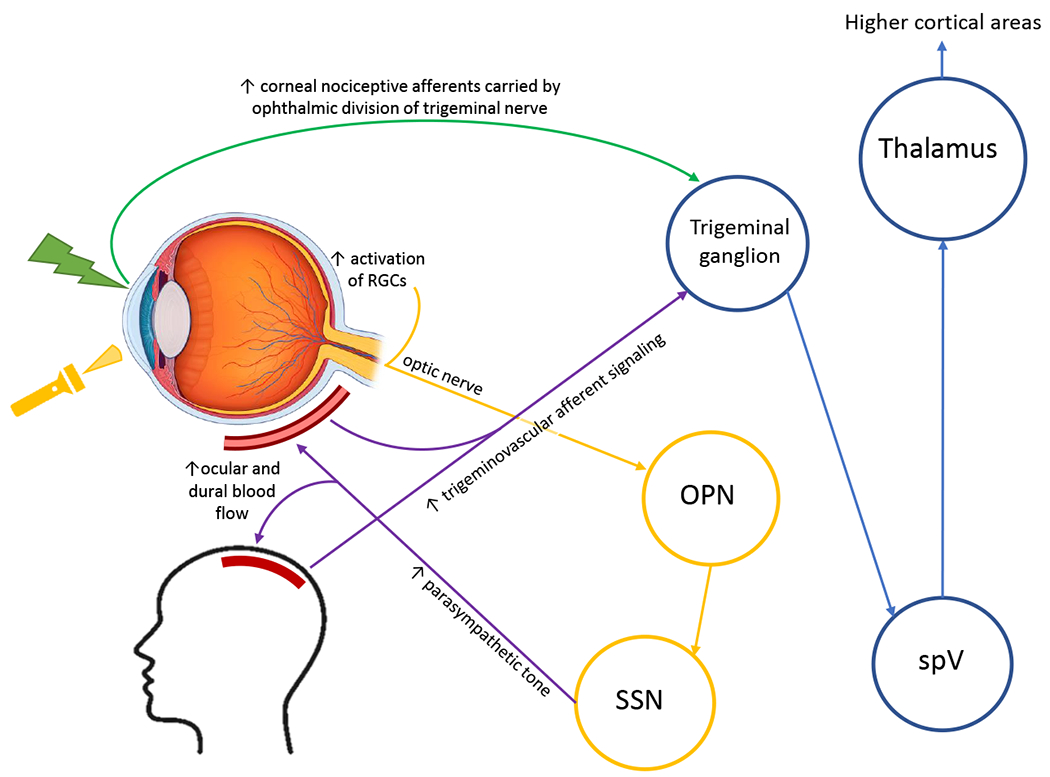

One comorbid condition with chronic ocular surface pain that has been found to overlap in pathophysiology is migraine.23 Several neuroimaging studies have demonstrated functional alterations in patients with migraine.24,25 Migraine pain is thought to originate from irritation of the meninges, which leads to transmission of nociceptive signals from the dura mater to the brain via the trigeminovascular pathway (shown in yellow and purple in Figure 5).26 Photophobia, a common presenting symptom in migraineurs, has also been studied as a mechanism of pain in these individuals.26–30 One study examined the link between the visual and pain processing systems in chronic migraine using fMRI.30 Compared to healthy controls, migraineurs with and without headache during the scan showed greater activation within the spinal trigeminal nucleus upon presentation of noxious visual stimuli. This needs to be taken under consideration when interpreting our results as three case subjects in our study had a migraine history without an active episode during the scanning session. Taken together, these observations suggest direct co-activation of intraocular trigeminonociceptive fibers within spinal trigeminal nuclei, thereby representing crosslinks between the visual and trigeminal pain processing systems.

Figure 5. Schematic representation of shared trigeminal-related mechanisms in ocular pain, migraine, and photophobia.

RGC=retinal ganglion cells; OPN=olivary pretectal nucleus; SSN=superior salivatory nucleus; spV=spinal trigeminal nucleus. Adapted figure with permission.41

4.3. Pain processing and modulation beyond the trigeminal pain pathway

While the trigeminal pathway is an important modulator of oculofacial pain sensation, it is important to consider other drivers of symptoms that exist outside this circuit, as illustrated by the heterogeneity of our case group’s subjective pain scores after applying topical anesthesia to the ocular surface. Pain processing is a multidimensional state that activates brain networks related to sensory-discriminative, affectional-motivational, cognitive-evaluative, and pain modulatory systems.31 In our study, aMCC and insula displayed greater activation in cases vs. controls. Experimental pain models in humans attribute functional activity observed within the cingulate and insula to the influence of pain regulation by negative affect and cognitive control.32 Such studies highlight how negative emotions may enhance pain sensitivity by functional amplification of cingulate and insular cortices. Our current findings are suggestive of a functional explanation to the clinical findings of extreme depression and anxiety that often accompany chronic ocular pain and photophobia, in which some cases of suicide have been reported.18

4.4. Limitations

Our findings are based on a small population with differences in multiple parameters, including demographics, comorbidities, and clinical tear characteristics. The influence on pain networks by various demographic features may exist as confounders to our findings, as there has been some support for sex-specific and age differences in pain-related brain activity detected by neuroimaging, but not for race or ethnicity.33–39 Overall, the impact on demographics on fMRI findings are not well understood in the field of neuropathic pain and warrant further investigation. Unmeasured factors may also confound differences in functional brain activation and pain reports (e.g., ocular medications, systemic pain medications or mood modulators, genetic differences).

Similarly, the heterogenous response to anesthetic suggests heterogeneity within the case group, with potentially different neural mechanisms that need to be further examined in larger studies. Also, as we observed no differences in brainstem activity after anesthetic, either between or within groups, our contrast analysis with these subject numbers may not be sensitive enough to identify smaller brainstem structures.

4.5. Conclusion

Despite these limitations, our study is the first to examine neural mechanisms in individuals with chronic ocular surface pain and photophobia, providing support for involvement of the trigemino-cortical pain pathway in driving photophobia in individuals with chronic ocular surface pain. We also demonstrated partial benefit in subjective pain report and fMRI metrics after topical anesthesia was applied to the eye, providing the foundation for developing therapies that can be administered topically to modulate central pain pathways.

In addition, painful ocular surface symptoms can exist as an isolated condition or be co-morbid with other chronic pain syndromes40 and our paper highlights potential shared mechanistic pathways that can be addressed with similar treatments. In fact, a few reports have described how oral medications, such as gabapentin, naltrexone, and tricyclic antidepressants, can improve chronic ocular surface pain in some individuals.40 Our findings give biological relevance to this clinical observation that need to be tested more robustly in future studies.

Supplementary Material

Funding/support:

This study was supported by a research grant from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Clinical Sciences (I01 CX002015). Other support included Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Biomedical Laboratory Services (I01 BX004893), the Department of Defense Gulf War Illness Research Program (W81XWH-20-1-0579) and Vision Research Program (W81XWH-20-1-0820), the National Eye Institute (R01EY026174 and R61EY032468), National Institutes of Health (P30EY014801), and Research to Prevent Blindness.

Other acknowledgements:

The authors would like to acknowledge Mireya Hernandez for patient recruitment and data collection and Elizabet Reyes for technical assistance and acquiring data. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Athanasios Panorgias of the New England College of Optometry for assisting with refinement of the visual stimulation protocol.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stapleton F, Alves M, Bunya VY, et al. TFOS DEWS II Epidemiology Report. Ocul Surf. Jul 2017;15(3):334–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galor A, Feuer W, Lee DJ, et al. Depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and dry eye syndrome: a study utilizing the national United States Veterans Affairs administrative database. Am J Ophthalmol. Aug 2012;154(2):340–346 e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Craig JP, Nichols KK, Akpek EK, et al. TFOS DEWS II Definition and Classification Report. Ocul Surf. Jul 2017;15(3):276–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belmonte C, Nichols JJ, Cox SM, et al. TFOS DEWS II pain and sensation report. Ocul Surf. Jul 2017;15(3):404–437. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crane AM, Levitt RC, Felix ER, Sarantopoulos KD, McClellan AL, Galor A. Patients with more severe symptoms of neuropathic ocular pain report more frequent and severe chronic overlapping pain conditions and psychiatric disease. Br J Ophthalmol. Feb 2017;101(2):227–231. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-308214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenthal P, Baran I, Jacobs DS. Corneal pain without stain: is it real? Ocul Surf. Jan 2009;7(1):28–40. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70290-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalangara JP, Galor A, Levitt RC, Felix ER, Alegret R, Sarantopoulos CD. Burning Eye Syndrome: Do Neuropathic Pain Mechanisms Underlie Chronic Dry Eye? Pain Med. Apr 2016;17(4):746–55. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnv070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodriguez DA, Galor A, Felix ER. Self-Report of Severity of Ocular Pain Due to Light as a Predictor of Altered Central Nociceptive System Processing in Individuals With Symptoms of Dry Eye Disease. J Pain. Dec 8 2021;doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2021.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crane AM, Feuer W, Felix ER, et al. Evidence of central sensitisation in those with dry eye symptoms and neuropathic-like ocular pain complaints: incomplete response to topical anaesthesia and generalised heightened sensitivity to evoked pain. Br J Ophthalmol. Sep 2017;101(9):1238–1243. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2016-309658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moisset X, Villain N, Ducreux D, et al. Functional brain imaging of trigeminal neuralgia. European Journal of Pain. 2011/02/January/ 2011;15(2):124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2010.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raja SN, Carr DB, Cohen M, et al. The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain. Sep 1 2020;161(9):1976–1982. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schiffman RM, Christianson MD, Jacobsen G, Hirsch JD, Reis BL. Reliability and validity of the Ocular Surface Disease Index. Arch Ophthalmol. May 2000;118(5):615–21. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.5.615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Melzack R. The short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire. Pain. Aug 1987;30(2):191–197. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(87)91074-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chalmers RL, Begley CG, Caffery B. Validation of the 5-Item Dry Eye Questionnaire (DEQ-5): Discrimination across self-assessed severity and aqueous tear deficient dry eye diagnoses. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. Apr 2010;33(2):55–60. doi:S1367-0484(09)00182-9 [pii] 10.1016/j.clae.2009.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farhangi M, Feuer W, Galor A, et al. Modification of the Neuropathic Pain Symptom Inventory for use in eye pain (NPSI-Eye). Pain. Jul 2019;160(7):1541–1550. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolffsohn JS, Arita R, Chalmers R, et al. TFOS DEWS II Diagnostic Methodology report. Ocul Surf. Jul 2017;15(3):539–574. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moulton EA, Becerra L, Borsook D. An fMRI case report of photophobia: activation of the trigeminal nociceptive pathway. Pain. Oct 2009;145(3):358–63. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.07.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galor A, Moein HR, Lee C, et al. Neuropathic pain and dry eye. Ocul Surf. Jan 2018;16(1):31–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ong ES, Felix ER, Levitt RC, Feuer WJ, Sarantopoulos CD, Galor A. Epidemiology of discordance between symptoms and signs of dry eye. Br J Ophthalmol. May 2018;102(5):674–679. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-310633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain. Mar 2011;152(3 Suppl):S2–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.09.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okamoto K, Thompson R, Tashiro A, Chang Z, Bereiter DA. Bright light produces Fos-positive neurons in caudal trigeminal brainstem. Neuroscience. Jun 2 2009;160(4):858–64. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rahman M, Okamoto K, Thompson R, Bereiter DA. Trigeminal pathways for hypertonic saline- and light-evoked corneal reflexes. Neuroscience. 2014;277:716–723. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.07.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diel RJ, Mehra D, Kardon R, Buse DC, Moulton E, Galor A. Photophobia: shared pathophysiology underlying dry eye disease, migraine and traumatic brain injury leading to central neuroplasticity of the trigeminothalamic pathway. Br J Ophthalmol. Jun 2021;105(6):751–760. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-316417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Russo A, Silvestro M, Tedeschi G, Tessitore A. Physiopathology of Migraine: What Have We Learned from Functional Imaging? Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. Oct 23 2017;17(12):95. doi: 10.1007/s11910-017-0803-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borsook D, Burstein R, Moulton E, Becerra L. Functional imaging of the trigeminal system: applications to migraine pathophysiology. Headache. Jun 2006;46 Suppl 1:S32–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00488.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burstein R, Noseda R, Fulton AB. Neurobiology of Photophobia. J Neuroophthalmol. Mar 2019;39(1):94–102. doi: 10.1097/wno.0000000000000766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noseda R, Bernstein CA, Nir RR, et al. Migraine photophobia originating in cone-driven retinal pathways. Brain. Jul 2016;139(Pt 7):1971–86. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noseda R, Burstein R. Migraine pathophysiology: anatomy of the trigeminovascular pathway and associated neurological symptoms, cortical spreading depression, sensitization, and modulation of pain. Pain. Dec 2013;154 Suppl 1:S44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noseda R, Kainz V, Jakubowski M, et al. A neural mechanism for exacerbation of headache by light. Nat Neurosci. Feb 2010;13(2):239–45. doi: 10.1038/nn.2475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schulte LH, Allers A, May A. Visual stimulation leads to activation of the nociceptive trigeminal nucleus in chronic migraine. Neurology. May 29 2018;90(22):e1973–e1978. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000005622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Apkarian AV, Bushnell MC, Treede RD, Zubieta JK. Human brain mechanisms of pain perception and regulation in health and disease. Eur J Pain. Aug 2005;9(4):463–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ploghaus A, Narain C, Beckmann CF, et al. Exacerbation of pain by anxiety is associated with activity in a hippocampal network. J Neurosci. Dec 15 2001;21(24):9896–903. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.21-24-09896.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fauchon C, Meunier D, Rogachov A, et al. Sex differences in brain modular organization in chronic pain. Pain. Apr 1 2021;162(4):1188–1200. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim JA, Bosma RL, Hemington KS, et al. Sex-differences in network level brain dynamics associated with pain sensitivity and pain interference. Hum Brain Mapp. Feb 15 2021;42(3):598–614. doi: 10.1002/hbm.25245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vincent K, Tracey I. Sex hormones and pain: the evidence from functional imaging. Curr Pain Headache Rep. Oct 2010;14(5):396–403. doi: 10.1007/s11916-010-0139-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cole LJ, Farrell MJ, Gibson SJ, Egan GF. Age-related differences in pain sensitivity and regional brain activity evoked by noxious pressure. Neurobiol Aging. Mar 2010;31(3):494–503. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tseng MT, Chiang MC, Yazhuo K, Chao CC, Tseng WI, Hsieh ST. Effect of aging on the cerebral processing of thermal pain in the human brain. Pain. Oct 2013;154(10):2120–2129. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.06.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Farrell MJ. Age-related changes in the structure and function of brain regions involved in pain processing. Pain Med. Apr 2012;13 Suppl 2:S37–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01287.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Losin EAR, Woo CW, Medina NA, Andrews-Hanna JR, Eisenbarth H, Wager TD. Neural and sociocultural mediators of ethnic differences in pain. Nat Hum Behav. May 2020;4(5):517–530. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-0819-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Galor A, Hamrah P, Haque S, Attal N, Labetoulle M. Understanding chronic ocular surface pain: An unmet need for targeted drug therapy. Ocul Surf. Aug 13 2022;26:148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2022.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheng K, Martin LF, Slepian MJ, Patwardhan AM, Ibrahim MM. Mechanisms and Pathways of Pain Photobiomodulation: A Narrative Review. J Pain. Jul 2021;22(7):763–777. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2021.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.