Abstract

The Ganoderma meroterpenoids are a growing class of natural products with architectural complexity, and exhibit a wide range of biological activities. Here, we report an enantioselective total synthesis of the Ganoderma meroterpenoid (‒)-lucidumone. The synthetic route features several key transformations, including a) a Cu-catalyzed enantioselective silicon-tethered intramolecular Diels-Alder cycloaddition to construct the highly functionalized bicyclo[2.2.2]octane moiety; b) Brønsted acid promoted tandem O-deprotection/Prins cyclization/Cycloetherification sequence followed by oxidation to install concurrently the tetrahydrofuran and the fused indanone framework; c) Fleming-Tamao oxidation to generate the secondary hydroxyl; d) an iron-catalyzed Wacker-type oxidation of hindered vinyl group to methyl ketone.

Subject terms: Natural product synthesis, Natural product synthesis, Asymmetric synthesis

The Ganoderma meroterpenoids are a growing class of natural products with a wide range of biological activities. Here, the authors report the enantioselective total synthesis of the Ganoderma meroterpenoid (‒)-lucidumone, featuring a copper-catalyzed enantioselective silicon-tethered intramolecular Diels-Alder cycloaddition to assemble the bicyclo[2.2.2]octane framework and a domino deprotection/Prins reaction/cycloetherification/oxidation sequence to generate concurrenly the tetrahydrofuran and the fused indanone skeleton.

Introduction

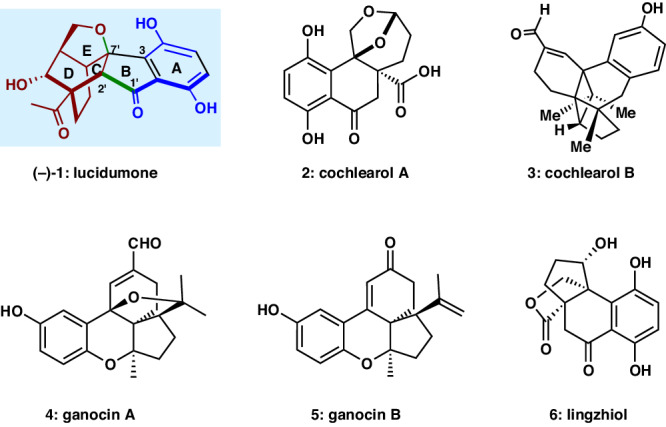

Ganoderma fungi (Ganodermataceae), a well-known mushroom, has been widely used in traditional Chinese medicine for the prevention and treatment of cancer, hypertension, chronic bronchitis, and asthma for decades1,2. The meroterpenoids constituents of Ganoderma species have attracted much attention from the pharmacological and synthetic communities due to their diverse and complex structures and potent bioactivities. For example, cochlearol A (2)3–8, cochlearol B (3), ganocin A (4)9–14, ganocin B (5), and lingzhiol (6)15–24 have been systematically studied by synthetic communities (Fig. 1)25. Most recently, an unprecedented cage-like meroterpenoid, namely, lucidumone (1), was isolated by Cheng and co-workers from the fruiting bodies of Ganoderma lucidum cultivated in Yongsheng County of Yunnan Province in China26. Its structure was initially deduced based on extensive 2D-NMR and HRESIMS analysis, featuring a 6/5/6/6/5 polycyclic ring system, one exposed secondary alcohol, a fused indanone motif, and six contiguous stereocenters on the bicyclo[2.2.2]octane subunit. Isolated as a racemate, the two enantiomers were separated by chiral-phase HPLC and the absolute configuration of the (‒)-lucidumone was determined by X-ray crystallographic analysis. Preliminary biological evaluation revealed that both enantiomers of 1 exhibit potent inhibitory effects against COX-1 and COX-2. Molecular docking study revealed that (‒)-lucidumone (‒)-(1) selectively inhibits COX-2 via bonding to Tyr385 and Ser530 residues, making it a potential lead in searching for anti-inflammatory drugs. Undoubtedly, the structural complexity and the potential biological activity render it an attractive synthetic target. In 2022, She and co-workers reported the construction of a pentacyclic skeleton of lucidumone (1) in racemic form featuring an elegant oxidative dearomatization/intramolecular Diels–Alder cycloaddition and acid-promoted dynamic kinetic resolution cyclization27. Torre’s group accomplished the first total synthesis of (+)-lucidumone involving an enantioselective inverse-electron-demand Diels–Alder reaction (IEDDA) and a one pot retro-[4 + 2]/[4 + 2] cycloaddition sequence28. Most recently, Kawamoto and Ito’s group disclosed a fascinating total synthesis of racemic lucidumone (1) by means of one-pot Claisen rearrangement/intramolecular aldolization for the construction of the tetracyclic framework. The enantioselective total synthesis of (‒)-lucidumone (‒)-(1) was also accomplished through a chiral transfer strategy in the Claisen rearrangement step29. In this report, we disclose an enantioselective total synthesis of (‒)-lucidumone (‒)-(1). The salient features of our strategy include a Cu-catalyzed enantioselective silicon-tethered intramolecular Diels-Alder cycloaddition to assemble the bicyclo[2.2.2]octane framework and a domino deprotection/Prins reaction/Cycloetherification/oxidation sequence to generate concurrently the tetrahydrofuran and the fused indanone skeleton.

Fig. 1. Representative Ganoderma meroterpenoids.

(‒)-lucidumone [(‒)-(1)], cochlearol A (2), cochlearol B (3), ganocin A (4), ganocin B (5), and lingzhiol (6).

Results

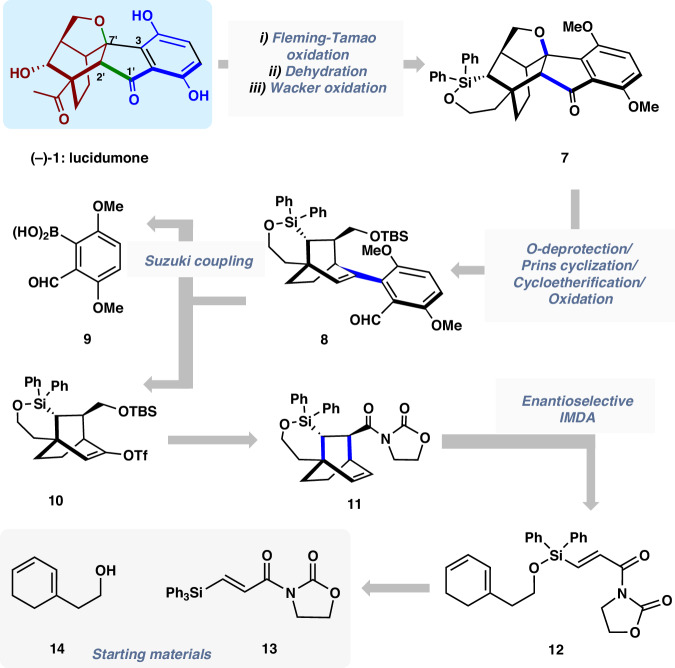

With an in-depth analysis of the chemical structure of lucidumone, we envisioned that the critical tetrahydrofuran-spiro-indanone framework (E-B-A rings of the natural product), a challenging task for synthesis, could be constructed via a pivotal cascade Prins cyclization/Cycloetherification followed by oxidation30,31. The precursor for this key transformation could be divided into two parts, the left bicyclo[2.2.2]octane moiety (highlighted in red) and right benzene (highlighted in blue), which would be connected through the transition metal-catalyzed C7’–C3 bond formation. Owing to the high regio- and stereoselectivity of intramolecular Diels–Alder cycloaddition than the intermolecular one, the silicon-tethered intramolecular Diels–Alder reaction gives us an excellent choice for the assembly of bicyclo[2.2.2]octane moiety32–35. In addition to the expected high degrees of regio- and stereoselectivity, the silicon-tethered intramolecular Diels–Alder reaction could also provide suitable synthetic handles for the rapid generation of the requisite secondary alcohol and methyl ketone.

Retrosynthetic analysis

With the hypothesis in mind, we proposed our retrosynthetic analysis of (‒)-lucidumone (‒)−1 in Fig. 2. We envisioned to access (‒)-1 from hexacyclic intermediate 7 via a sequence of Fleming–Tamao oxidation, Wacker oxidation and O-demethylation. The fused indanone framework could be constructed by a key O-deprotection/Prins reaction/Cycloetherification followed by oxidation sequence from 8, which in turn could be assembled via a Suzuki coupling between boronic acid 9 and vinyl triflate 10. The latter could be traced back to 11, the product of asymmetric intramolecular Diels–Alder reaction of 12, which could be accessed from the known diene 1436 and the easily accessible silyl acrylate imide 13.

Fig. 2. Retrosynthetic analysis of (‒)-lucidumone [(‒)-1].

The key disconnections involve Cu-catalyzed enantioselective silicon-tethered intramolecular Diels–Alder cycloaddition to construct C/D rings and a tandem Prins cyclization/Cycloetherification sequence to construct rings E/B/A, respectively.

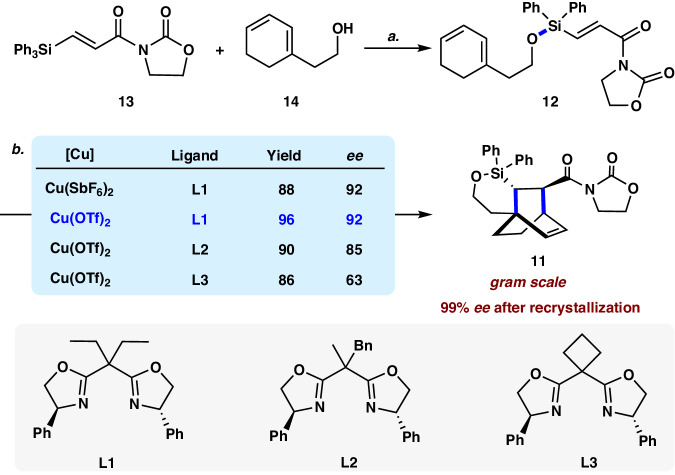

Synthesis of chiral bicyclo[2.2.2]octane

The synthesis of 1 commenced with the preparation of 12 (Fig. 3). Following the protocol developed by Sieburth37, exposure of the readily available silyl acrylate imide 13 to triflic acid, followed by the addition of the known primary alcohol 14 afforded silyl ether 12 in 91% yield. The Diels–Alder cycloaddition of 12 in the presence of Et2AlCl (0.1 equiv) at 0 °C proceeded smoothly to give the desired cycloadduct in 90% yield as a single endo diastereoisomer. Encouraged by this observation, we turned our attention to the catalytic asymmetric silicon-tethered intramolecular Diels–Alder reaction of 1238,39. Following Evans’s pioneering work, diverse chiral C2-symmetric Box ligands were used in combination with different Cu(II) salt40–42. Screening the reaction conditions by varying the reaction temperature, the ligands, and the copper sources led to the identification of the optimized reaction condition using Cu(OTf)2 (10 mol%) and ligand (S,S)-L1 (11 mol%) at 50 °C (see Supplementary Table 1). Under these conditions, cycloadduct 11 was isolated in 96% yield with 92% ee. Performing the reaction at 3.0 mmol in the presence of Cu(OTf)2 (0.3 mmol), (S,S)-L1 (0.33 mmol) afforded 11 without obvious erosion of yield and enantioselectivity (95% yield, 92% ee). The ee value of 11 could be further improved to 99% after recrystallization. The absolute configuration of 11 was determined by the X-ray diffraction analysis of its derivative (vide infra, compound 17).

Fig. 3. Synthesis of chiral bicyclo[2.2.2]octane 11.

Reagents and conditions: a TfOH (2.2 equiv), 2,6-lutidine (2.4 equiv), DCM, ‒78 to 0 °C, then 14, 91%; b Cu(OTf)2 (0.1 equiv), L1 (0.11 equiv), DCM, 50 °C, 96% yield, 92% ee. TfOH triflic acid, 2,6-lutidine 2,6-dimethylpyridine, DCM dichloromethane.

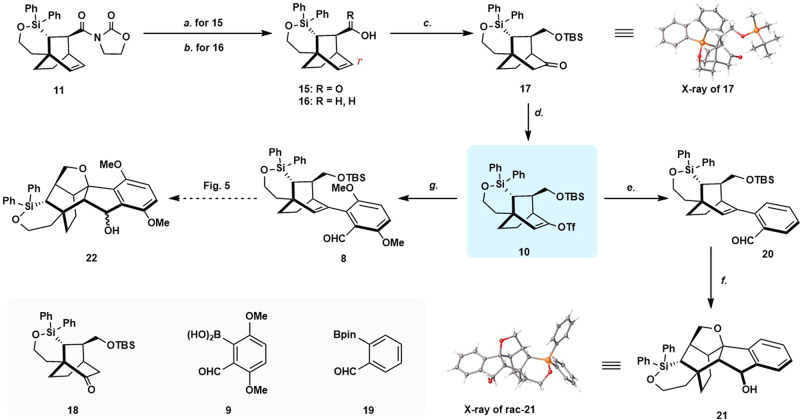

Synthesis of hexacyclic intermediate

With the gram-scale synthesis of chiral bicyclo[2.2.2]octane intermediate 11 in hand, the synthesis of highly functionalized hexacyclic intermediate 22 was undertaken (Fig. 4). Hydrolysis of 11 (LiOH, H2O2, THF/H2O v/v = 2:1, 0 °C to RT) afforded the carboxylic acid 15 in 94% yield. On the other hand, reduction of 11 with lithium borohydride (LiBH4) provided the alcohol 16 in 85% yield. We surmised that the neighboring carboxylic acid group of 15 or the hydroxy group of 16 could be used to direct the hydroboration at C7’43,44. Treatment of 15 with BH3·THF (‒30 °C to RT.) followed by the addition of NaBO3·4H2O furnished the mixed diol product resulting from the concomitant reduction of the carboxylic acid. Without purification, this diol was converted to ketone 17 and its regioisomer 18 in 89% overall yield (rr = 3.4:1) via a sequence of selective O-protection and oxidation. The absolute configuration of the tricycle ketone 17 was determined by X-ray crystallographic analysis. Therefore, the successful elaboration of 17 according to our synthetic plan would afford the levorotatory target molecular (‒)-lucidumone (‒)-1. Notably, applying the same conditions to alcohol 16, a mixture of two regioisomeric ketones was isolated in 1:1 ratio. These results indicated that carboxylic acid is a better-directing group in the hydroboration step.

Fig. 4. Synthesis of hexacyclic intermediate 22.

Reagents and conditions: a LiOH (3.0 equiv), H2O2 (8.8 equiv), THF-H2O (v:v = 2:1), 0 °C to RT, 94%; b LiBH4 (4.0 equiv), THF, 0 °C, 85%; c i. BH3·THF (5.0 equiv), THF, ‒30 °C to RT, NaBO3 ·4H2O (10.0 equiv). ii. TBSCl (3.0 equiv), imid (5.0 equiv), DCM, RT. iii. DMP (2.0 equiv), NaHCO3 (10 equiv), RT, 69% for 17, 20% for 18; d KHMDS (1.4 equiv), PhNTf2 (1.4 equiv), THF, −78 oC, 94%; e 19 (2.0 equiv), Pd(dppf)Cl2 (0.1 equiv), K3CO3 (3.0 equiv), DMSO, 80 °C, 96%; f HCl (2 M in ethyl acetate) (10.0 equiv), DCM, ‒10 °C, 89%; g 9 (2.0 equiv), Pd(dppf)Cl2 (0.1 equiv), S-Phos (0.2 equiv), K3PO4 (3.0 equiv), DMF, 80 °C, 69%. THF tetrahydrofuran, TBSCl tert-Butyldimethylsilyl chloride, imid Imidazole, DMP Dess–Martin periodinane, KHMDS potassium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide, PhNTf2 N-phenyl-bis(trifluoromethanesulfonimide), S-Phos 2-dicyclohexylphosphino-2′,6′-dimethoxybiphenyl, DMF N, N-dimethylformamide.

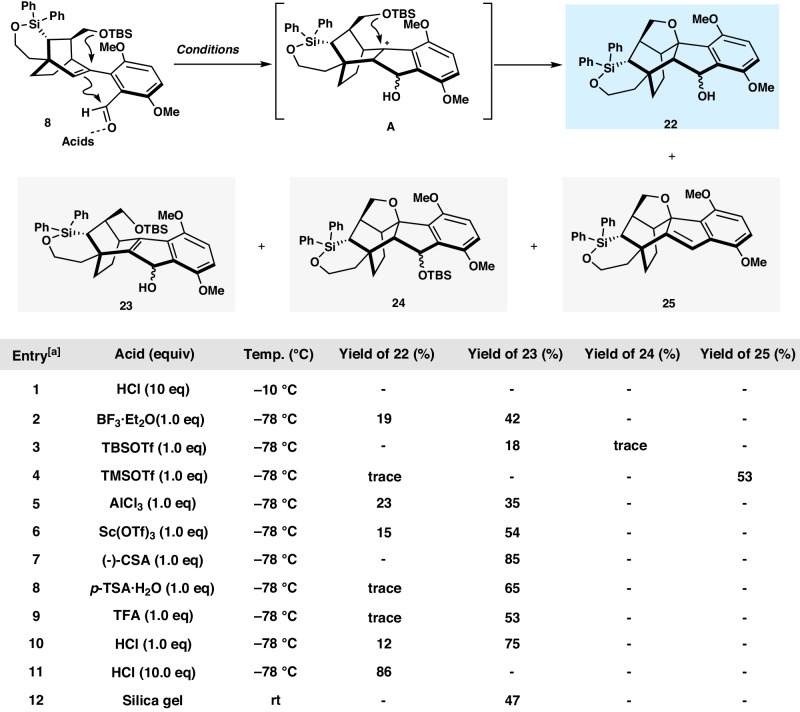

We then turned our attention to build A-B-E rings of the natural product. Deprotonation of ketone 17 with potassium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide (KHMDS) at ‒78 °C followed by the addition of PhNTf2 afforded the desired vinyl triflate 10 in 94% isolated yield. The Pd-catalyzed Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling between 10 and the known boronic acid 945 proceeded smoothly to afford the functionalized tetracycle 8 in 69% yield. The one-step conversion of 8 to 22, a strategic step in our synthesis, was sought next. This efficient transformation involved a hypothetical acid-catalyzed O-deprotection/Prins cyclization/Cycloetherification sequence30,31,46–53. Model reaction was attempted first before the real substrate. The precursor 20, generated through Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling between 10 and commercially available 2-formylphenylboronic acid pinacol ester 19, was screened in various acidic conditions for the key transformation. Gratifyingly, the desirable 21 was obtained in the presence of HCl (10 equiv) in DCM at ‒10 °C in 89% yield with 20:1 diastereoselectivity (X-ray of major rac-21). However, tetracycle 8 is unstable and was decomposed when treated with the aforementioned identical condition. The realization of the transformation turned out to be a challenging task. The desired product as a pair of diastereoisomers 22 could be isolated under a series of acidic conditions with the concomitant formation of Prins cyclization product 23. To minimize the generation of by-products, different Brønsted acids [TFA, HCl, p-TsOH·H2O, (‒)-CSA] and Lewis acids [BF3·Et2O, AlCl3, Sc(OTf)3, TBSOTf, TMSOTf, etc.] in different solvents at various temperatures were screened (Fig. 5). HCl was still identified as the most suitable promotor. The optimum reaction conditions consisted of stirring a DCM solution of 8 in the presence of an excess of HCl (2 M in ethyl acetate, 10 equiv) at ‒78 °C for 24 h (Fig. 5, Entry 11). Under these conditions, 22 was generated as a pair of diastereoisomers in 86% yield, which could also be directly oxidized by Dess–Martin periodinane to afford the desired product 7 in a one-pot sequence in 80% overall yield (Fig. 6). The structure and absolute configuration of 7 was confirmed by X-ray crystallographic analysis. We note that the reaction temperature and time have to be carefully controlled in order to avoid the formation of by-products.

Fig. 5. Optimization of tandem O-deprotection/Prins cyclization/Cycloetherification conditions.

[a]Conditions: 8 (0.03 mmol), DCM (1.5 mL. c 0.02 M), N2 atmosphere.

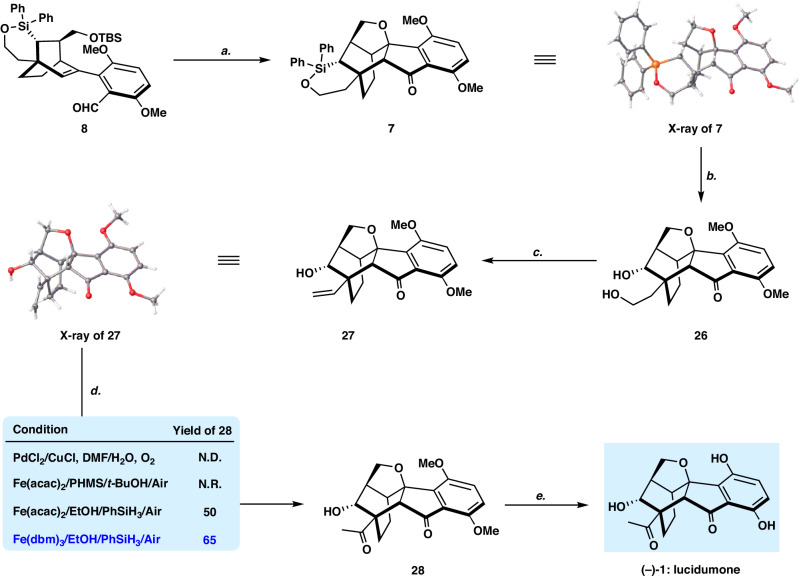

Fig. 6. Total synthesis of (‒)-lucidumone [(‒)−1].

Reagents and conditions: a HCl (2 M in ethyl acetate) (10.0 equiv), DCM, ‒78 °C, then DMP (2.0 equiv), NaHCO3 (10.0 equiv), RT, 80%; b KF (5.0 equiv), H2O2 (20 equiv), KHCO3 (1.6 equiv), MeOH-THF (v:v = 1:1), 50 °C, 91%; c 2-nitrophenylselenocyanate (1.2 equiv), Py (1.2 equiv), PBu3 (1.2 equiv), H2O2 (24 equiv), THF, 50%; d Fe(dbm)3 (0.1 equiv), PhSiH3 (10 equiv), EtOH, RT, 65%; e AlCl3 (10 equiv), 1-dodecanethiol (20 equiv), DCM, RT, 70%.

Total synthesis of (‒)-lucidumone

Elaboration of hexacycle 7 to (‒)-lucidumone (‒)-1 was accomplished as shown in Fig. 6. The Fleming–Tamao oxidation of 7 (KF, H2O2, methanol/THF, v/v = 1:1) afforded diol 26 in 91% yield54. It was noted that by-product 23 could also be converted to diol 26 under the sequential Dess–Martin oxidation and the Fleming–Tamao oxidation via a spontaneous deprotection/oxa-Michael addition. Dehydration of 26 underwent smoothly to give the desired product 27 (X-ray) in 50% isolated yield according to Grieco’s procedure55. As Kawamoto and Ito mentioned29, the late-stage Wacker oxidation of the vinyl group 27 to methyl ketone group 28 proved to be challenging. Under classic conditions, aldehyde resulting from the anti-Markovnikov addition was formed as a major product due presumably to the steric effect56. We then turned our attention to the iron-catalyzed Wacker-type oxidation of olefins to ketones developed by Han’s57 and Knӧlker’s58 groups, respectively. Gratefully, applying their standard conditions to 27 [Fe(dbm)3, PhSiH3, EtOH, RT], methylketone 28 was obtained in 65% yield. Finally, Lewis acid catalyzed double O-demethylation of 28 afforded (‒)-lucidumone (‒)-1 in 70% isolated yield. The physical and spectroscopic data of the synthetic (‒)-lucidumone (‒)-1 are identical to those reported for the natural product.

In this work, an enantioselective total synthesis of (‒)-lucidumone (‒)-1 is accomplished. Our synthetic route to this natural product features several key transformations, including bis(oxazoline)copper(II) complex catalyzed enantioselective silicon-tethered intramolecular Diels–Alder reaction to construct the multi-functionalized bicyclo[2.2.2]octane moiety, a Brønsted acid promoted tandem O-deprotection/Prins reaction/Cycloetherification followed by oxidation to install concurrently the tetrahydrofurane and the fused indanone moieties, Fleming–Tamao oxidation to afford the secondary hydroxyl, and an iron-catalyzed late-stage Wacker-type oxidation of hindered vinyl group to methyl ketone.

Methods

Unless otherwise stated, reagents were purchased at the highest commercial quality and used without further purification. Solvents were purchased in HPLC quality, degassed by purging thoroughly with nitrogen, and dried over activated molecular sieves of appropriate size. Alternatively, they were purged with argon and passed through alumina columns in a solvent purification system (Innovative Technology). The conversion was monitored by thin layer chromatography (TLC) using Merck TLC silica gel 60 F254. Compounds were visualized by UV light at 254 nm and by dipping the plates in an ethanolic vanillin/sulfuric acid solution or a 72 aqueous potassium permanganate solution followed by heating. Flash column chromatography was performed over silica gel (230−400 mesh).

NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker 500 and 400 MHz at room temperature, Chemical shifts (δ) were reported in parts per million (ppm) relative to residual solvent peaks rounded to the nearest 0.01 for proton and 0.1 for carbon. Coupling constants (J) were reported in Hz to the nearest 0.1 Hz. Peak multiplicity was indicated as follows s (singlet), d (doublet), t (triplet), q (quartet), m (multiple), and br (broad). The attribution of peaks was done using the multiplicities and integrals of the peaks.

IR spectra were recorded in a Perkin-Elmer 1000 series FT-IR spectrometer. The spectra were reported in cm−1.

The accurate masses were measured by the mass spectrometry service of IMM, PUMC&CAMS on an Agilent 6244 Tof-MS using electrospray ionization (ESI).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Financial support for this work was provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22371301 to G.L.), Non-profit Central Research Institute Fund of Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (2021-RC350-005 to G.L.), and startup funding (to G.L.) from State Key Laboratory of Bioactive Substance and Function of Natural Medicines, Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College. We also thank Prof. Jieping Zhu (Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne) and Prof. Liansuo Zu (Tsinghua University) for helpful discussions and advice during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author contributions

X.-Z.L., R.W., X.W., and G.L. conceived and designed the experiments. G.L. directed the project. X.-Z.L. and R.W. carried out the experiments. X.-Z.L., R.W., X.W., and G.L. interpreted the results. G.L. wrote the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Kazuyuki Sugita and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) under deposition numbers 2271397 (17), 2277937 (7), 2312931 (21), and 2284054 (27). Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/. All other data supporting the findings of this study, including experimental procedures and compound characterization, NMR, and HPLC, are available within the Article and its Supplementary Information or from the corresponding author upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Xian-Zhang Liao, Ran Wang.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-024-46896-3.

References

- 1.Paterson RRM. Ganoderma—a therapeutic fungal biofactory. Phytochemistry. 2006;67:1985–2001. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang Z-L, Feng B. What is the Chinese “Lingzhi”?—A taxonomic mini-review. Mycology. 2013;4:1–4. doi: 10.1080/21501203.2013.774299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dou M, et al. Cochlearols A and B, polycyclic meroterpenoids from the fungus ganoderma cochlear that have renoprotective activities. Org. Lett. 2014;16:6064–6067. doi: 10.1021/ol502806j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang D-W, et al. Total synthesis of (±)-cochlearol A. Org. Lett. 2019;21:6761–6764. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b02391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naruse K, et al. Formal synthesis of cochlearol A, a meroterpenoid with renoprotective activity. Tetrahedron Lett. 2020;61:151845. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2020.151845. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mashiko T, et al. Total synthesis of cochlearol B via intramolecular [2 + 2] photocycloaddition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021;60:24484–24487. doi: 10.1002/anie.202110556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richardson AD, Vogel TR, Traficante EF, Glover KJ, Schindler CS. Total synthesis of (+)-cochlearol B by an approach based on a Catellani reaction and visible-light-enabled [2+2] cycloaddition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022;61:e202201213. doi: 10.1002/anie.202201213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao, Z. et al. A unified and bio-inspired total syntheses of cochlearol B and ganocins A-C via a cyclobutane as overbred intermediate. Preprint at ChemRxiv10.26434/chemrxiv-2022-xxmgl (2022).

- 9.Peng X-R, et al. Four new polycyclic meroterpenoids from ganoderma cochlear. Org. Lett. 2014;16:5262. doi: 10.1021/ol5023189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peng X, et al. Unusual prenylated phenols with antioxidant activities from Ganoderma cochlear. Food Chem. 2015;171:251–257. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.08.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shao H, Gao X, Wang Z-T, Gao Z, Zhao Y-M. Divergent biomimetic total syntheses of ganocins A–C, ganocochlearins C and D, and cochlearol T. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020;59:7419–7424. doi: 10.1002/anie.202000677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang F, Zhao Y-M. Divergent total syntheses of six ganoderma meroterpenoids: a bioinspired two-phase strategy. Synlett. 2020;31:1551–1554. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1707898. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mashiko T, et al. Enantioselective total syntheses of (+)-Ganocin A and (−)-Cochlearol B. Org. Lett. 2023;25:8382–8386. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.3c03572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang, Z. et al. Bioinspired synthesis of cochlearol B and ganocin A. Chin. Chem. Lett. 34, 10.1016/j.cclet.2023.109247 (2023).

- 15.Yan Y-M, et al. Lingzhiols, unprecedented rotary door-shaped meroterpenoids as potent and selective Inhibitors of p-Smad3 from ganoderma lucidum. Org. Lett. 2013;15:5488–5491. doi: 10.1021/ol4026364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Long R, et al. Asymmetric total synthesis of (−)-lingzhiol via a Rh-catalysed [3+2] cycloaddition. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:5707. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen D, et al. Concise synthesis of (±)-lingzhiol via epoxy-arene cyclization. Chem. Commun. 2015;51:14594–14596. doi: 10.1039/C5CC05680B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen D, et al. Enantioselective total synthesis of (+)-lingzhiol via tandem semipinacol rearrangement/Friedel–Crafts type cyclization. Chem. Commun. 2016;52:8561–8564. doi: 10.1039/C6CC03764J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li X, et al. An approach to (±)-lingzhiol. Org. Lett. 2016;18:1944–1946. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b00542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gautam KS, Birman VB. Biogenetically inspired synthesis of lingzhiol. Org. Lett. 2016;18:1499–1501. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b03212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mehl L-M, Maier ME. A radical-based synthesis of lingzhiol. J. Org. Chem. 2017;82:9844–9850. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.7b01416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rengarasu R, Maier ME. Total synthesis of lingzhiol and its analogues through the Wittig reaction of an oxocyclopentane carboxylate. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2017;6:108–117. doi: 10.1002/ajoc.201600455. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riehl PS, Richardson AD, Sakamoto T, Schindler CS. Eight-step enantiodivergent synthesis of (+)- and (−)-lingzhiol. Org. Lett. 2020;22:290–294. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b04322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Magauer, T., Rode, A. & Wurst, K. A general entry to ganoderma meroterpenoids: synthesis of Lingzhiol via photoredox catalysis. Preprint at ChemRxiv10.26434/chemrxiv-2022-svqft (2022).

- 25.Kawamoto, Y. & Ito, H. Total synthesis of ganoderma meroterpenoids—progresses since 2014. Asian J. Org. Chem. e202300633 (2024).

- 26.Yan Y-M, et al. (±)-Lucidumone, a COX-2 inhibitory caged fungal meroterpenoid from ganoderma lucidum. Org. Lett. 2019;21:8523–8527. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b02840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma S, et al. Construction of the skeleton of lucidumone. Org. Lett. 2022;24:5541–5545. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.2c02023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang G, Kouklovsky C, de la Torre A. Gram-scale enantioselective synthesis of (+)-lucidumone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022;144:17803–17807. doi: 10.1021/jacs.2c08760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawamoto Y, Noguchi N, Kobayashi T, Ito H. Total synthesis of lucidumone through convenient one-pot preparation of the tetracyclic skeleton by claisen rearrangement and subsequent intramolecular aldol reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023;62:e202304132. doi: 10.1002/anie.202304132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee HM, Nieto-Oberhuber C, Shair MD. Enantioselective synthesis of (+)-Cortistatin A, a potent and selective inhibitor of endothelial cell proliferation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:16864–16866. doi: 10.1021/ja8071918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li B, Tan C, Ma T, Jia Y. Bioinspired total synthesis of bipolarolides A and B. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024;62:e202319306. doi: 10.1002/anie.202319306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bols M, Skrydstrup T. Silicon-tethered reactions. Chem. Rev. 1995;95:1253–1277. doi: 10.1021/cr00037a006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brosius AD, Overman LE, Schwink L. Total synthesis of (+)-Aloperine. use of a nitrogen-bound silicon tether in an intramolecular Diels−Alder reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:700–709. doi: 10.1021/ja983013+. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shvartsbart A, Smith AB., III Total synthesis of (−)-calyciphylline N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:870–873. doi: 10.1021/ja411539w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shvartsbart A, Smith AB., III The daphniphyllum alkaloids: total synthesis of (−)-calyciphylline N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:3510–3519. doi: 10.1021/ja503899t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Engel PS, Allgren RL, Chae W-K, Leckonby RA, Marron NA. Thermolysis of allylic azoalkanes. J. Org. Chem. 1979;44:4233–4239. doi: 10.1021/jo01338a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sieburth SM, Lang J. A practical synthesis of difunctional organosilane reagents and their application to the Diels−Alder reaction. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:1780–1781. doi: 10.1021/jo990082d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Corey EJ. Catalytic enantioselective Diels−Alder reactions: methods, mechanistic fundamentals, pathways, and applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:1650–1667. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020517)41:10<1650::AID-ANIE1650>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reymond S, Cossy J. Copper-catalyzed Diels−Alder reactions. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:5359–5406. doi: 10.1021/cr078346g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Evans DA, Johnson JS. Chiral C2-symmetric Cu(II) complexes as catalysts for enantioselective intramolecular Diels−Alder reactions. Asymmetric synthesis of (−)-Isopulo’upone. J. Org. Chem. 1997;62:786–787. doi: 10.1021/jo962187b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Evans DA, Miller SJ, Lectka T, von Matt P. Chiral Bis(oxazoline)copper(II) complexes as lewis acid catalysts for the enantioselective Diels−Alder reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:7559–7573. doi: 10.1021/ja991190k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Evans DA, et al. Bis(oxazoline) and Bis(oxazolinyl)pyridine copper complexes as enantioselective Diels−Alder catalysts: reaction scope and synthetic applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:7582–7594. doi: 10.1021/ja991191c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rarig R-AF, Scheideman M, Vedejs E. Oxygen-Directed Intramolecular hydroboration. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:9182–9183. doi: 10.1021/ja800402g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gimazetdinov AM, Gimazetdinova TV, Miftakhov MS. Synthesis of enantiomeric cyclosarcomycins. Mendeleev Commun. 2010;20:15–16. doi: 10.1016/j.mencom.2010.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Basak S, Mal D. Intramolecular carbonyl-ene reactions in the synthesis of peri-oxygenated hydroaromatics. Tetrahedron. 2016;72:1758–1772. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2016.02.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arundale E, Mikeska LA. The olefin-aldehyde condensation. The prins reaction. Chem. Rev. 1952;51:505–555. doi: 10.1021/cr60160a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang H, He H, Gao S. Asymmetric total synthesis of Cephanolide A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020;59:20417–20422. doi: 10.1002/anie.202009562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ruggeri RB, Hansen MM, Heathcock CH. Total synthesis of (±)-methyl homosecodaphniphyllate: a remarkable new tetracyclization reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:8734–8736. doi: 10.1021/ja00234a046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.MacMillan DWC, Overman LE. Enantioselective total synthesis of (-)-7-deacetoxyalcyonin acetate. First synthesis of a eunicellin diterpene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:10391–10392. doi: 10.1021/ja00146a028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sun Y, et al. Bioinspired total synthesis of sespenine. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:9012–9016. doi: 10.1002/anie.201404191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li L, Sun X, He Y, Gao L, Song Z. TMSBr/InBr3-promoted Prins cyclization/homobromination of dienyl alcohol with aldehyde to construct cis-THP containing an exocyclic E-alkene. Chem. Commun. 2015;51:14925–14928. doi: 10.1039/C5CC06270E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li H, Chen Q, Lu Z, Li A. Total syntheses of aflavazole and 14-hydroxyaflavinine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:15555–15558. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b10880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhou S, Xia K, Leng X, Li A. Asymmetric total synthesis of arcutinidine, arcutinine, and arcutine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:13718–13723. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b05818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tamao K, Kumada M, Maeda K. Silafunctional compounds in organic synthesis. 21. Hydrogen peroxide oxidation of alkenyl(alkoxy)silanes. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984;25:321–324. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)99873-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grieco PA, Gilman S, Nishizawa M. Organoselenium chemistry. A facile one-step synthesis of alkyl aryl selenides from alcohols. J. Org. Chem. 1976;41:1485–1486. doi: 10.1021/jo00870a052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fernandes RA, Jha AK, Kumar P. Recent advances in Wacker oxidation: from conventional to modern variants and applications. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2020;10:7448–7470. doi: 10.1039/D0CY01820A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu B, Jin F, Wang T, Yuan X, Han W. Wacker-type oxidation using an Iron catalyst and ambient air: application to late-stage oxidation of complex molecules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:12712–12717. doi: 10.1002/anie.201707006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Puls F, Linke P, Kataeva O, Knӧlker H-J. Iron-catalyzed Wacker-type oxidation of olefins at room temperature with 1,3-Diketones or neocuproine as ligands. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021;60:14083–14090. doi: 10.1002/anie.202103222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) under deposition numbers 2271397 (17), 2277937 (7), 2312931 (21), and 2284054 (27). Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/. All other data supporting the findings of this study, including experimental procedures and compound characterization, NMR, and HPLC, are available within the Article and its Supplementary Information or from the corresponding author upon request.