Abstract

Histone proteins can become trapped on DNA in the presence of 5-formylcytosine (5fC) to form toxic DNA-protein conjugates. Their repair may involve proteolytic digestion resulting in DNA-peptide cross-links (DpCs). Here, we have investigated replication of a model DpC comprised of an 11-mer peptide (NH2–GGGKGLGK∗GGA) containing an oxy-lysine residue (K∗) conjugated to 5fC in DNA. Both CXG and CXT (where X = 5fC-DpC) sequence contexts were examined. Replication of both constructs gave low viability (<10%) in Escherichia coli, whereas TLS efficiency was high (72%) in HEK 293T cells. In E. coli, the DpC was bypassed largely error-free, inducing only 2 to 3% mutations, which increased to 4 to 5% with SOS. For both sequences, semi-targeted mutations were dominant, and for CXG, the predominant mutations were G→T and G→C at the 3ʹ-base to the 5fC-DpC. In HEK 293T cells, 7 to 9% mutations occurred, and the dominant mutations were the semi-targeted G → T for CXG and T → G for CXT. These mutations were reduced drastically in cells deficient in hPol η, hPol ι or hPol ζ, suggesting a role of these TLS polymerases in mutagenic TLS. Steady-state kinetics studies using hPol η confirmed that this polymerase induces G → T and T → G transversions at the base immediately 3ʹ to the DpC. This study reveals a unique replication pattern of 5fC-conjugated DpCs, which are bypassed largely error-free in both E. coli and human cells and induce mostly semi-targeted mutations at the 3ʹ position to the lesion.

Keywords: DNA polymerase, DNA-protein crosslinks, DNA replication, mutagenesis, peptides, protein-DNA interaction, 5-formylcytosine, translesion synthesis

DNA-protein cross-links (DPCs) can form with a variety of cellular proteins after exposure to UV radiation, heavy metals, free radicals, and chemotherapeutic agents (1, 2, 3). DPCs block DNA replication and transcription (4, 5, 6, 7). They also interfere with chromatin structure and may result in genomic instability and cell death (1, 4, 8). DPCs have been associated with several human ailments including cancer and aging (9, 10, 11). The initial steps of cellular repair of DPCs involve proteolytic digestion. An investigation on formaldehyde-induced DNA-histone DPC in human cells showed that DPC repair was inhibited following treatment of the cells with proteasome inhibitors, suggesting that DPCs repair is initiated by proteolytic degradation of the cross-linked proteins (12). Subsequently, multiple studies confirmed that DPC removal in cells involves proteolytic degradation of the cross-linked proteins, which may be carried out by Wss1 in yeast cells and SPRTN (SprT-like N-terminal domain) in mammalian cells (13, 14). DPCs may also undergo ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation (15, 16, 17, 18). Proteolytic degradation of DPCs leaves behind DNA-peptide cross-links (DpC), which can be excised by nucleotide excision repair (NER) (19). However, replication may take place prior to excision of the peptide lesions, and while DPCs are found to be a complete block of DNA replication, DpCs can be bypassed in an error-free or error-prone manner via translesion synthesis (TLS) polymerases (2, 5).

5-Formylcytosine (5fC) is an epigenetic DNA mark that acts as an intermediate in the DNA demethylation pathway and has its own regulatory roles (20). 5fC is present at a frequency of 0.2 to 0.3% of total cytosines in all mammalian tissues, with higher levels found in the brain (21). The aldehyde group of 5fC can spontaneously react with lysine and arginine side chains of histone proteins in human cells to form Schiff base conjugates, which have been shown to regulate chromatin structure and gene expression levels (22, 23, 24, 25). As Schiff bases are reversible, we have developed an oxime ligation methodology to generate site-specific, hydrolytically stable model DpCs (26). Our methodology employs protein engineering to insert an unnatural oxy-lysine amino acid into a peptide derived from the N-terminus of histone H4. The oxy-lysine reacts with the aldehyde functional group of 5fC in DNA, forming a hydrolytically stable oxime DNA-peptide conjugate. This approach was also used to conjugate oxy-lysine-containing histone H3 to 5fC-containing DNA (26). These conjugates are structurally analogous to DPCs found in human cells and have been used extensively to investigate the biological effects of 5fC-histione cross-links (5).

Previous studies from our laboratory have focused on DNA replication in the presence of model 5fC-mediated DNA-protein conjugates and determined that they completely block DNA polymerases, including TLS DNA polymerases η and κ, specialized DNA polymerases known to bypass other bulky DNA lesions (5). In contrast, the corresponding small peptide lesions were readily bypassed (5). To elucidate the effects of local DNA sequence on polymerase bypass, we examined the efficiency and the fidelity of human DNA polymerase (pol) η upon bypass of 5fC DpCs placed in seven different local DNA sequence contexts (CXC, CXG, CXT, CXA, AXA, GXA, and TXA) (27). Primer extension and steady-state kinetics experiments showed that the neighboring bases influence DpC lesion bypass by hPol η. For example, dAMP incorporation opposite the lesion in the CXT sequence was most efficient, and molecular dynamics simulations provided a rationale for this bias (27). However, cellular replication of structurally modified DNA is much more complex, as multiple DNA polymerases and accessory proteins can be involved in the lesion bypass (28, 29, 30). In the current work, we have investigated the replication properties of this DpC lesion in two sequence contexts, namely, CXG and CXT, in Escherichia coli and HEK 293T cells. In addition, we have conducted biochemical experiments with purified hPol η and hPol ι to support our findings for human cells.

Results

Replication of DpC located at CXG and CXT sequences in E. coli

The 17-mer oligonucleotides CXG (i.e., 5ʹ–TTC CXG GTC ACG ACG TT–3ʹ) and CXT (i.e., 5ʹ–TTC CXT GTC ACG ACG TT–3ʹ), containing 5fC at the fifth position from the 5ʹ end cross-linked to the oxy-lysine residue K∗ of the 11-mer peptide (NH2–GGGKGLGK∗GGA) derived from the N-terminal region of histone H4 (X), were prepared as described previously (26, 27), phosphorylated, and ligated to a single-stranded pMS2 plasmid in which a suitable 17-nucleotide gap was created by a 56-mer scaffold oligonucleotide (Fig. 1).

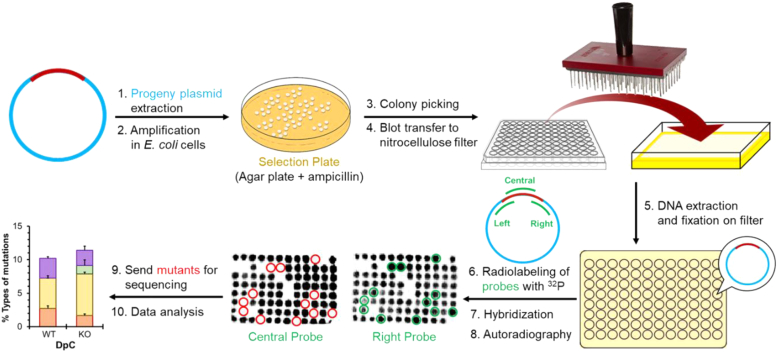

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram forconstruction of a single DpC-containing pMS2 vector anditsreplication in human cells.

DpC-containing constructs and the corresponding control plasmids were replicated in E. coli AB1157 cells. As shown in Figure 2, relative to the control plasmid the presence of DpC lowered the number of colonies derived from each construct significantly, which may be a reflection of TLS efficiency (or polymerase bypass efficiency). The TLS efficiency of the CXG construct was 7.3 ± 1.9%, which increased to 15.3 ± 1.3% with SOS. Likewise, for the CXT construct, TLS efficiency of 9.5 ± 1.1% and 24.3 ± 1.8%, respectively, were observed without and with SOS induction.

Figure 2.

TLS efficiency of 5fC-linked DpC CXG and CXT in E. coli AB 1157 cells with or without SOS relative to control. The data represent the mean and standard deviation from four independent replication experiments. Black dots represent the individual data points; error bars represent the standard deviation. The statistical significance of the difference in % viability between –SOS and +SOS cells was calculated using two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test (∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001).

The progeny plasmids were next subjected to mutational analysis, which indicated that the DpC is weakly mutagenic in E. coli, inducing 2.8% and 1.9% mutations in CXG and CXT sequences, respectively (Fig. 3, A and C). With SOS, MF increased to 5.0% and 4.0%, respectively, for the same (Fig. 3, B and D). For the CXG sequence, the mutations occurred at various neighboring sites, with a very low level targeted at the 5fC where the peptide was attached. The predominant mutations were G→T and G→C at the 3ʹ-base to the 5fC site both with and without SOS, even though the relative proportions of these mutations were different in the two sets. G→T was the major mutation without SOS, and G→C was the dominant mutation with SOS induction. It is interesting to note that the increased MF with SOS in other sites was largely due to an increased number of single-base deletions. For the CXT sequence, targeted mutations occurred at a low level, and, in addition to various semi-targeted mutations, a significant frequency of single-base deletions occurred at the neighboring sites both with and without SOS. The majority of mutations occurred at the bases 3ʹ side of the lesion.

Figure 3.

Types and frequencies of mutations induced by 5fC-conjugated DpCs in CXGand CXTsequences in E. coli cells without and with SOS.A and B, CXG. C and D, CXT.

In addition to a control construct with C at the fifth position, which gave no mutants, we have also analyzed the replication of 5fC. 5fC was weakly mutagenic inducing 0.6 to 1.2% semi-targeted mutations both with and without SOS (Table S5). No targeted mutations were detected.

Replication of DpC located at CXG and CXT sequences in human cells

The DpC constructs and a control plasmid containing a different DNA sequence at the cross-linked site were co-transfected into HEK 293T cells. The unmodified DNA was used as an internal control of transfection efficiency. Cells were incubated for 24 h to allow for one round of replication of plasmid DNA. Progeny plasmids were isolated and used to transform E. coli DH10B cells. The percentages of the colonies originating from the lesion-containing plasmid relative to the unmodified pMS2 plasmid reflect the bypass efficiency of the TLS polymerases. As described for the analyses of progeny in replication in E. coli, the types and frequencies of mutations in the progeny were examined by oligonucleotide hybridization, followed by DNA sequencing.

In human embryonic kidney (HEK 293T) cells, the TLS efficiency of the DpC-containing plasmid was about 72% for both CXG and CXT constructs (Fig. 4). This suggests that a change in the 3ʹ base (G vs T) does not influence bypass efficiency in HEK 293T cells. As expected, the control vector gave an equal number of progeny as the internal control (100% efficiency). For replication of the CXG construct, TLS efficiency remained unaffected in hPol η- and hPol ζ-deficient cells, whereas a modest decrease in TLS efficiency was observed in hPol ι- and hPol κ-knockout cells. For CXT construct replication, however, TLS was only marginally decreased in hPol η- and hPol κ-deficient cells, whereas deficiency of hPol ι or hPol ζ had no effect on TLS efficiency. Taken together, except for hPol κ, which reduced TLS efficiency in both sequence contexts, other TLS polymerases have little effect in bypassing this DpC.

Figure 4.

TLS efficiencies of 5fC-linked DpCin HEK 293T cells with or without knockout of various TLS polymerases relative to control. The data in panel A (CXG) and panel B (CXT) represent the mean and standard deviation from three to four independent replication experiments. Black dots represent the individual data points; error bars represent the standard deviation. The statistical significance of the difference in % TLS efficiency between HEK 293T and polymerase-deficient cells was calculated using two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test (∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001).

As in E. coli, 5fC was weakly mutagenic in HEK 293T cells, inducing ∼2% semi-targeted mutations and nearly 100% TLS efficiency (Table S6).

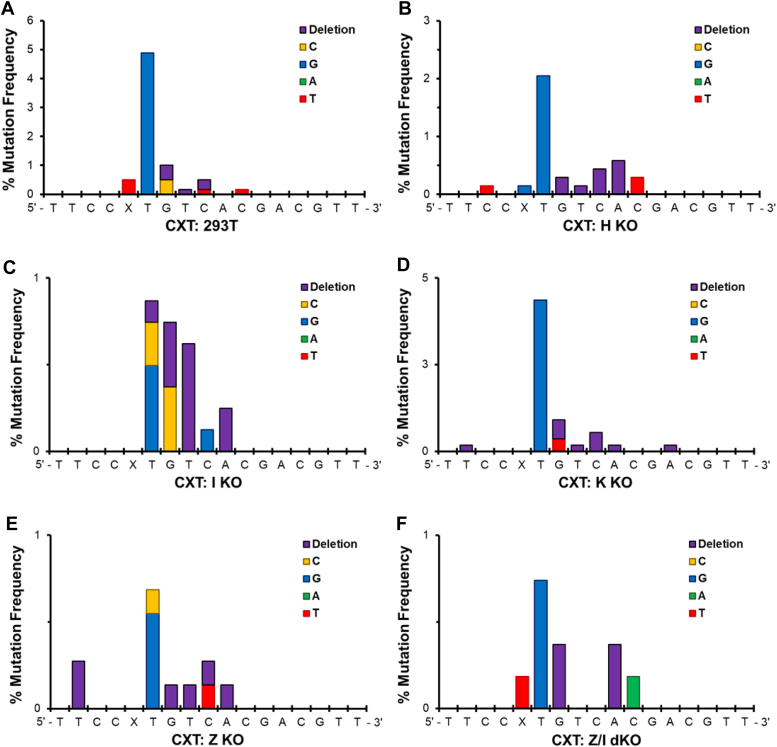

Mutations induced by DpC in the CXG and CXT sequence and the roles of TLS polymerases in HEK 293T cells

In HEK 293T cells, 8.5% and 7.3% of DpC-induced mutations occurred for CXG and CXT sequences, respectively (Fig. 5). Analogous to the results in E. coli, no targeted mutation was detected, and the dominant mutations were the semi-targeted G → T for CXG (Fig. 4A) and T → G for CXT (Fig. 4B) at the 3ʹ neighboring base of the lesion site (underlined). Additional semi-targeted mutations contained base substitutions and deletions detected near the peptide-conjugated 5fC, even though modified C was replicated error-free. As in E. coli, more semi-targeted mutations at the 3ʹ side of the lesion were detected (Fig. 5). Our molecular dynamics simulations published previously (5) have revealed that in a ternary complex with DNA polymerase, the 11-mer peptide is accommodated in the DNA major groove facing the 3ʹ end of the DNA sequence, which could explain the observed semi-targeted effects of these bulky lesions.

Figure 5.

Mutation frequencies of 5fC-linked DpCin HEK 293T cells with or without knockout of various TLS polymerases. The data in panel A (CXG) and panel B (CXT) represent the mean and standard deviation from three to four independent replication experiments. Black dots represent the individual data points; error bars represent the standard deviation. The statistical significance of the difference in % mutation frequency between HEK 293T and polymerase(s)-deficient cells was calculated using two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test (∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001).

When the same constructs were replicated in different TLS polymerase(s)-knockout HEK 293T cells, for both CXG and CXT constructs, a significant reduction in MF by more than 40% was observed in hPol η-, hPol ι-, and hPol ζ-deficient cells, whereas it was unaffected in hPol κ knockout cells (Fig. 5). The G → T transversion for the CXG sequence was reduced by more than 60% from 4.5 ± 0.3% in HEK 293T cells to 1.8 ± 0.2% in hPol η-knockout cells, whereas it was reduced by more than 85% to 0.6 ± 0.1% and 0.6 ± 0.1% in hPol ι- and hPol ζ-deficient cells, respectively. Similarly, for CXT, the T → G mutation was reduced from 5.0 ± 0.4% in HEK 293T cells to 2.0 ± 0.3%, 0.5 ± 0.1%, 0.6 ± 0.1% in hPol η-, hPol ι-, and hPol ζ-deficient cells, respectively. However, when hPol ι and hPol ζ were simultaneously knocked out, a synergistic effect in the reduction in MF was not observed (Fig. 5). Collectively, these results suggest that hPol ι and hPol ζ are the main polymerases involved in the error-prone bypass of this DpC, at the 3ʹ base to the lesion, with hPol η playing a smaller role in these mutations. Although no clear pattern in the types of mutations was observed for the other types of semi-targeted mutations (Figs. 6 and 7), participation of hPol η, hPol ι, and hPol ζ in mutagenesis, specifically at the 3ʹ base to the DpC lesion, can be concluded from these results.

Figure 6.

Types and frequencies of mutations induced in the progeny from the 5fC-linked DpC in CXG sequence in HEK 293T cellsand various polymerase knockout HEK 293T cells. The data in panel A (CXG sequence in HEK 293T cells) and panels B–F (various polymerase knockout HEK 293T cells) represent the mean and the standard deviation from 3 to 6 independent experiments.

Figure 7.

The types and frequencies of mutations induced in the progeny from the 5fC-linked DpC in CXT sequence in HEK 293T cellsand various polymerase knockout HEK 293T cells. The data in panel A (CXG sequence in HEK 293T cells) and panels B–F (various polymerase knockout HEK 293T cells) represent the mean and the standard deviation from 3 to 6 independent experiments.

In vitro single-nucleotide incorporation experiments

To investigate the involvement of specific lesion bypass DNA polymerases in DpC-mediated mutagenesis, primer extension assays with recombinant hPol ƞ or hPol ɩ were performed using DNA templates containing 5-fC mediated DpC lesions or unmodified dC. Based on our in vivo results discussed above, primer-template complexes were designed to evaluate the fidelity of nucleotide incorporation at the −1 position from the DpC lesion in two different sequence contexts (CXG and CXT). To initiate primer extension, single dNTP and recombinant TLS polymerase were added to the template-primer complex (1:20 hPol ƞ:DNA and 1:4 hPol ɩ:DNA molar ratio), and the reactions were quenched after incubation for 30 min (hPol ƞ) or 60 min (hPol ɩ). We found that both hPol ƞ or hPol ɩ were capable of catalyzing error-free nucleotide incorporation at the −1 position to DpC in CXG and CXT contexts (Figs. 8 and S2), with hPol ƞ having a greater efficiency than hPol ɩ. Additionally, hPol ƞ and hPol ɩ catalyzed dTMP misincorporation upstream of the DpC lesion in both sequence contexts. In cells, this would lead to G → A and T → A mutations. Both hPol ƞ and hPol ɩ were able to incorporate dCMP opposite −1 position of DpC in the CXT sequence, which is anticipated to induce T → G transitions. dAMP misincorporation opposite the −1 guanine (CXG) was observed upon replication of CXG sequence by hPol ƞ, while dCMP misincorporation opposite −1 thymine was detected when using CXT sequence and hPol ɩ catalysis. In CXT sequence context, incorporation of dTMP (incorrect nucleotide) by hPol ɩ was more efficient than that of dAMP (correct nucleotide) (Fig. 8), demonstrating a high rate of mispairing by this polymerase during catalysis of nucleotide incorporation across these specific sequences. In general, the presence of DpC lesion had a relatively small effect on polymerase fidelity at the −1 position, but strongly affected the efficiency of nucleotide incorporation.

Figure 8.

Single-nucleotide insertion assays for replication across 3ʹ position ofthe 5fC-linked DpC. The assays in two DNA sequence contexts by hPol ƞ (A and C) and hPol ɩ (B and D) were performed with primer-template duplex containing unmodified dC or 5fC-conjugated 11-mer peptide cross-link. The reactions with hPol ƞ were quenched at 30 min and those with hPol ɩ were quenched at 60 min.

To compare the kinetics of correct and incorrect nucleotide addition immediately upstream of the DpC lesions, we conducted steady-state kinetics analyses of dAMP or dCMP misincorporation opposite −1 position of the DpC lesion in control (CCG, CCT) and DpC-containing sequences (CXG, CXT). Our kinetic experiments have focused on hPol ƞ due to its higher catalytic efficiency as compared to hPol ɩ (see above). The kinetics of nucleotide insertion opposite dG or dT at 3ʹ neighboring bases of the template was investigated. To ensure steady-state kinetics condition 20 to 250-fold molar excess of DNA over hPol ƞ was employed (see Fig. S3 for representative gel images). Primer extension reactions were conducted in the presence of increasing amounts of dATP or dCTP (10–800 μM), and the parameters Vmax and Km were determined by plotting reaction velocities against the concentrations of dAMP or dCMP with nonlinear regression of the Michaelis-Menten model. Then, the catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) was calculated. The steady-state kinetics parameters for correct (dC:dG and dA:dT) and incorrect (dA:dG and dC:dT) nucleotide incorporations opposite −1 position from the lesion are shown in Table 1. In all cases, the incorporation of the correct nucleotide by hPol ƞ was more efficient than the addition of a wrong nucleotide. In most cases, the catalytic efficiency of dAMP or dCMP addition was slightly higher for control sequences containing unmodified C than that across the DpC-containing templates. However, dAMP insertion opposite G in CXG template was more efficient than the misincorporation of G using control sequence (CCG) (0.188 × 10−2 s−1/μM vs 0.042 × 10−2 s−1/μM), which could lead to G → T mutations at this position in the presence of the DpC cross-link. Additionally, dCTP misincorporation opposite dT at −1 position of the DpC lesion (CXT) occurred with 0.047 × 10−2 s−1/μM catalytic efficiency, which could lead to T → G transversions. The efficiency of dAMP misincorporation opposite G using the CXG template was 4-fold higher than for the control sequence (CCG) (Table 1), providing a possible explanation for semi-targeted G to T mutations at this position. Collectively, our kinetics data for hPol ƞ catalyzed nucleotide misincorporation at the −1 site from the DpC lesion in the CXG and CXT sequences supports the mutation results (G → T and T → G transitions) observed in HEK 293T cells (see above).

Table 1.

Steady-state kinetics parameters for single-nucleotide insertion of dAMP or dCMP opposite 3ʹ neighboring base (dG or dT) of DpC (X) or unmodified dC by hPol ƞ

| dNMP | Sequence | Vmax (μM/min) | Km (μM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Km (10−2 s−1/μM)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dCMP | CCG | 0.016 ± 0.001 | 54.41 ± 9.88 | 1.82 ± 0.09 | 3.350 ± 0.867 |

| CXG | 0.013 ± 0.002 | 55.33 ± 21.09 | 1.42 ± 0.16 | 2.567 ± 0.733 | |

| dCMP | CCT | 0.016 ± 0.003 | 182.3 ± 74.08 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.062 ± 0.028 |

| CXT | 0.043 ± 0.008 | 648.3 ± 207.6 | 0.30 ± 0.05 | 0.047 ± 0.027 | |

| dAMP | CCG | 0.019 ± 0.003 | 462.0 ± 167.9 | 0.20 ± 0.03 | 0.042 ± 0.020 |

| CXG | 0.006 ± 0.001 | 33.82 ± 18.63 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.188 ± 0.048 | |

| dAMP | CCT | 0.036 ± 0.005 | 169.6 ± 59.92 | 1.50 ± 0.20 | 0.883 ± 0.333 |

| CXT | 0.062 ± 0.016 | 557.4 ± 262.9 | 2.59 ± 0.66 | 0.467 ± 0.250 |

Catalytic efficiency of the nucleotide insertion for unmodified dC or DpC sequences is shown as kcat/Km.

Discussion

DNA sequence context is known to have an effect on replication of a DNA damage significantly (31, 32, 33, 34, 35). For example, the incorporation frequency of cytosine or thymine opposite O6-methylguanine (m6G) on a DNA template depends on the 3ʹ neighboring base (36). The sequence with cytosine on the 3ʹ position next to m6G shows a much higher preference for incorporating thymine opposite the DNA lesion (m6G:dT pair) than cytosine opposite m6G (m6G:dC pair) (36). Furthermore, the extension of DNA primer bypass of m6G is more favored in the C-m6G-C sequence, relative to T-m6G-T sequence (37). In addition, Essigmann et al. found the repair of m6G by Ada and Ogt methyltransferases is sequence-dependent in vivo (38). The sequence “Gm6GN” (N = any base) exhibit higher preference for m6G repair by Ada and Ogt (38). Another study demonstrated that DNA sequences affect the structure and energy of B[a]P-N2-dG adducts in DNA, which influence its mutagenesis (31). These reports indicate that DNA sequence context not only influences DNA repair efficiency but also substantially impacts the efficiency and fidelity of replicative bypass of a DNA lesion.

Our laboratories have been investigating DNA replication of bulky DNA-protein and DNA-peptide cross-links (DPCs and DpCs). DpCs form as a result of proteolytic processing of DPCs, which cause a complete block of DNA replication and transcription. Our previous in vitro primer extension experiments have revealed that local sequence context can influence the TLS polymerase Pol η activity (27). Among seven sequences, i.e., CXC, CXG, CXT, CXA, AXA, GXA, TXA, the catalytic efficiency of dAMP incorporation opposite X was the highest in the CXT sequence context compared to the other six sequences, even though the correct nucleotide (dGMP) was inserted much more efficiently in all cases. MD simulations indicated that the peptide is accommodated in the major groove of DNA and also provided a structural rationale for preferred dAMP incorporation in the CXT sequence context compared to the others (27).

Unlike in vitro replication by a single DNA polymerase, cellular replication is much more complex and can involve collaboration among multiple DNA polymerases (28, 29, 39). In the present work, we used two DNA sequence contexts, CXG and CXT, where X denotes the 5fC cross-linked 11-mer peptide, to investigate cellular replication of the DpC lesions. DNA sequence context has been shown to be important in modulating the repair and replication of a number of DNA modifications. Our current study showed that targeted mutation is very low in both E. coli and HEK 293T cells. This DpC was a stronger replication block in E. coli than in the HEK 293T cells, with greater numbers of mutations observed in human cells. Even upon induction of the SOS functions, the TLS efficiency of the CXG and CXT sequences were 15.3% and 24.3%, respectively, in E. coli, in contrast to 72% for each sequence in HEK 293T cells. This is not surprising, since a striking difference in TLS efficiency in human cells relative to E. coli was observed with other lesions. In replicative bypass of AP-site, for example, less than 1% TLS occurred in E. coli, in contrast to 20 to 30% TLS in HEK 293T cells in the same sequence context (40). The likely reason for this is that human cells carry a much more robust replication machinery relative to bacteria, allowing them more facile TLS. Indeed, the replication factors of bacteria are significantly different from those of archaea and eukaryotes, indicating that they evolved independently (41). In the current investigation, only a slight reduction in TLS efficiency in HEK 293T cells in the absence of a single TLS polymerase suggests that none of these polymerases play a primary role in bypassing the lesion. Our previous study showed that replicative polymerases δ and ε can bypass 5fC-DpC lesions in an error-free manner (42), not requiring lesion bypass polymerases.

In terms of mutagenesis, MF of DpC was lower in E. coli than in human cells. However, only semi-targeted mutations primarily at the 3ʹ neighboring base of the lesion were observed in both. The other semi-targeted mutations exhibited no specific pattern, but more events occurred at the 3ʹ side of the DpC (Figs. 3, 6 and 7). In human cells, knockout of a single TLS polymerase hPol η, hPol ι, or hPol ζ resulted in a major reduction, by more than 40 to 90%, in the dominant semi-targeted mutations G → T for CXG and T → G for CXT. Simultaneous knockout of hPol ι and hPol ζ gave similar results. These suggest a likely role of these three polymerases in the incorporation of the wrong dNTP opposite the 3ʹ base to the lesion. They might also be involved in the extension of the mismatched pair, which necessitates error-free incorporation of dG opposite the 5fC-DpC.

A unique aspect of this study is that this 5fC-linked DpC predominantly induced semi-targeted mutations. Many DNA lesions, and particularly intra-strand cross-links induced by γ-radiation or UV light, induce semi-targeted mutations in E. coli and mammalian cells (43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49). In most of these cases, semi-targeted mutations occur in addition to targeted mutations, although in some studies semi-targeted mutations were detected in higher frequency than targeted mutations (47, 49). Semi-targeted mutations have also been detected upon replication of other DpCs (42, 50). For instance, replication of DNA templates containing 10-mer Myc peptide cross-linked to G7 of 7-deaza-dG in HEK 293T cells showed that the DpC induced 20% targeted G→A transitions and G→T transversions plus 15% semi-targeted mutations, particularly at the guanine five bases 3ʹ to the lesion site (50). TLS efficiency and targeted mutations were reduced upon siRNA knockdown of pol η, pol κ, or pol ζ, indicating that they participate in an error-prone bypass of this DpC. However, the semi-targeted mutation at G5 was only reduced upon knockdown of pol ζ, suggesting its critical role in this specific mutation.

Primer extension experiments with (−1) primers and recombinant hPol η and hPol ɩ revealed that the 5fC-linked DpC lesion induced low levels of mutations one nucleotide upstream from the lesion (Fig. 8, Table 1, and Fig. S1), supporting the semi-targeted mutation observed in vivo discussed above. In single-nucleotide incorporation experiments, hPol ƞ primarily inserted correct nucleotides (dCMP or dAMP) opposite the −1 position of all four sequences (Fig. 8, A and C) while hPol ɩ catalyzed more dTMP insertion (incorrect) than dAMP insertion (correct) opposite CCT/CXT sequences (Fig. 8D). Additionally, the misincorporation of dAMP opposite dG (−1 position) in the CXG template only occurred in the presence of hPol ƞ (Fig. 8A), while the dGMP misincorporation opposite dT (−1 position) in CXT template was solely catalyzed by hPol ɩ (Fig. 8D). Nucleotide incorporation was slightly more efficient on control templates (CCG and CCT) as compared to DpC-containing templates (CXG and CXT, Table 1). The catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) of dCMP incorporation opposite dG (−1 position) in the CXG template was higher than the efficiency of dAMP incorporation opposite dT (−1 position) in the CXT templates (2.567 × 10−2 s−1/μM versus 0.467 × 10−2 s−1/μM). Our steady-state kinetics results revealing dAMP misincorporation opposite dG (−1 position) in CXG template with catalytic efficiency of 0.188 × 10−2 s−1/μM, as well as dCMP misincorporation opposite dT (−1 position) in CXT template with catalytic efficiency of 0.047 × 10−2 s−1/μM by hPol ƞ (Table 1 and Fig. S2) are consistent with the observation of G → T and T → G mutations at the 3ʹ neighboring base of the DpC lesion site in HEK 293T cells.

In another study conducted in our laboratory, replication of DNA containing a DpC with an 11-mer peptide cross-linked to 5fC in HEK 293T cells gave rise to 9% targeted and 5% semi-targeted mutations (42). Targeted mutations included C→T transitions and C deletions, whereas semi-targeted mutations involved several base substitutions and deletions near the DpC lesion but no dominant one like the previous case. Simultaneous deficiency of hPol η, hPol κ, and hPol ζ resulted in a significant reduction in MF (50–70%), suggesting that all these TLS polymerases play a major role in error-prone bypass of the DpC. In vitro experiments showed that hPol δ and hPol ε can accurately bypass the DpC. Consequently, both replicative and TLS polymerases can bypass this DpC lesion in human cells, but mutations are induced mainly by the TLS polymerases. The results of the primer extension assay with single-nucleotide incorporation proved this mutation potential with the TLS polymerases. Though the DpC in our current study is also cross-linked to 5fC, in the previous study it was conjugated to the lysine (K∗) residue of the 11-mer peptide (RPK∗PQQFFGLM-CONH2), whereas in the current investigation it was cross-linked to the lysine of a different 11-mer peptide (NH2–GGGKGLGK∗GGA). The neighboring DNA sequences also were different. It is evident, therefore, that both the peptide sequence and the DNA sequence influence the TLS and mutagenicity of the DpC.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that the 5fC-DpC is a strong block of replication in E. coli (viability <25% with SOS), whereas TLS (73%) is much more facile in HEK 293T cells. The lesion is bypassed largely in an error-free manner in both E. coli and HEK 293T cells. Mutations in E. coli (2–5%) and HEK 293T cells (7–9%) are largely semi-targeted with a specific one at the 3ʹ-base to the lesion, inducing G→T in the CXG sequence and T→G in the CXT sequence. In HEK 293T cells hPol η, hPol ι, or hPol ζ are involved in these specific semi-targeted mutations.

Experimental procedures

Reagents

All reagents and solvents were of commercial grade and used as such unless otherwise specified. The enzymes (EcoRV-HF restriction endonuclease, T4 DNA ligase, T4 polynucleotide kinase, uracil DNA glycosylase, and exonuclease III) were purchased from New England Biolabs. The lesion-containing oligodeoxynucleotide sequence used in this study are 5ʹ–TTC CXY GTC ACG ACG TT–3ʹ where X represents 5-formylcytosine (5fC) cross-linked to the lysine (K∗) of an 11-mer peptide (NH2–GGGKGLGK∗GGA) and Y = G (for CXG) or T (for CXT). Control oligonucleotides have the same DNA sequences except for X, which is replaced with a 5fC. All unmodified oligodeoxynucleotides (such as the controls, scaffolds, and probes) were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies and their sequences are provided in Fig. S1. [γ-32P] ATP was purchased from PerkinElmer Health Sciences Inc. Plasmid pMS2 was a gift from Professor M. Moriya (Stony Brook University, The State University of New York). Human embryonic kidney (HEK 293T) cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). HEK 293T cells with knockout of a single TLS polymerase hPol η, hPol κ, hPol ι, and hPol ζ, and simultaneous knockout of hPol ζ/hPol ι were a gift from Professor Yinsheng Wang (University of California), which were produced by using the CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing method (51, 52).

Construction and characterization of a pMS2 vector containing a single DpC lesion

A single lesion-containing single-stranded vector (pMS2), carrying ampicillin and neomycin resistance genes, were constructed as follows (Fig. 2) (50, 53). First, the pMS2 DNA (5 ug) was digested with an excess of EcoRV-HF, an engineered endonuclease with significant reduced star activity, at 37 °C water bath for 5 h. Next, a mixture of the 56-mer oligonucleotide scaffold, containing four uracil bases, and the digested pMS2 was incubated in a water bath heated to 75 °C which was allowed to cool slowly to room temperature and then left overnight at 4 °C to form a gapped circular DNA. The control and DpC-containing oligonucleotides were phosphorylated with T4 polynucleotide kinase, hybridized to the gapped pMS2 DNA, and ligated overnight at 16 °C. The pMS2 construct was then digested (at 16 °C for 13 h) with uracil DNA glycosylase and exonuclease III to remove the scaffold. Unligated oligonucleotides and salts were removed by using an Amicon Ultra-0.5 ml centrifugal filters 100K MWCO (Millipore Sigma). A portion of the final construct was subjected to electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel to assess the amount of circular DNA, which established that at least 40% ligation of the 12-mers occurred on both sides of the gap.

Replication in E. coli

Repair-competent E. coli (AB1157) cells were grown in 100 ml cultures in Luria broth to 1 × 108 cells/ml and were made electrocompetent with and without SOS induction using UV light (254 nm) (20 J/m2) as described. For each transformation, 60 μl of the cell suspension was mixed with 60 ng of pMS2 construct and transferred to the bottom of an ice-cold Bio-Rad Gene-Pulser cuvette (0.1 cm electrode gap). Electroporation of cells was carried out in a Bio-Rad Gene-Pulser apparatus at 25 μF and 1.8 kV with the pulse controller set at 200 Ω. Following a 1 h recovery at 37 °C, a portion of the cells were plated. Analysis of progeny phage was carried out by oligonucleotide hybridization followed by DNA sequencing as described below.

Replication in Human Embryonic Kidney (HEK 293T) and TLS polymerase-deficient HEK 293T cells

The HEK 293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 4 mM L-glutamine and adjusted to contain 1.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate, 4.5 g/L glucose, and 10% fetal bovine serum. The cells were grown to about 70 to 80% confluency for transfection. A mixture of 60 ng of the lesion-containing pMS2 construct and 60 ng of the internal control (IC) DNA construct with a 12-mer oligonucleotide sequence at the ligation site different from the lesion-containing (or control) DNA sequence was added to Lipofectamine cationic lipid reagent (3.6% final concentration) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) using Opti-MEM (Gibco). An unmodified control pMS2 vector, containing 5fC instead of the bulky DpC lesion, and an IC construct was also mixed at a molar ratio of 1:1. The mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 15 min to form the liposome complexes with the recombinant vectors. Following transfection with modified and unmodified pMS2 vector, the cells were allowed to grow at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 20 to 22 h and then harvested using RLT lysis buffer (Qiagen) and β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma). The same construct was transfected in single or double-knockout HEK 293T cell lines (Fig. 1).

Determination of lesion bypass efficiencies and mutation analyses of TLS products from human cells

The progeny plasmid DNA, generated after replication of the vector, was extracted and purified using QiaPrep Spin Miniprep Kit (Waltham, MA). The amount of recovered DNA varies, but it is typically between 90 ng and 120 ng. It was amplified by the transformation in E. coli DH10B cells, and the transformants were analyzed using oligonucleotide hybridization (Fig. 9). (3, 6) As shown in Fig. S1, the central probe is complementary to the DNA sequence at the insertion site of the lesion whereas the right and left probes are complementary to the DNA sequence on the right or left side near the site of ligation (the left probe is not shown here). The signals on all three probes imply the 5fC-DpC is copied a C. The TLS efficiency was determined as the percentages of the colonies originating from the lesion-containing plasmid relative to the internal control vector. Any transformants that hybridized on the right and probes but not on the central probe are considered putative mutants and were subjected to DNA sequence analysis. Transformants that did not bind to either the right or left probe were omitted.

Figure 9.

Schematic representation ofmutagenesis assay.

In vitro primer extension assays with single-nucleotide incorporation

The 5ʹ-end labeled 11-mer DNA primer (5ʹ -AAC GTC GTG AC-3′) was prepared as in the previous study (5). The primer (1 μl, 10 pmol) was annealed with 2 eq. 17-mer DNA template containing either unmodified dC or DpC lesion (5ʹ- TTC CXY GTC ACG ACG TT -3ʹ, X = unmodified dC or 5fC cross-linked 11-mer peptide, Y = dG or dT) by heating with annealing buffer (3 μl, 10 × conc.) at 95 °C for 10 min (the total volume of primer-template complex solution was 30 μl by adding enough nuclease-free H2O), followed by cooling to room temperature. 32P-labeled primer-template complex (3 μl, 1 pmol) was mixed with hpol ƞ (0.05 pmol) or hpol ɩ (0.27 pmol), which were expressed in E. coli based on published protocols in the presence of a buffer solution containing Tris-HCl (50 mM, pH 7.5), NaCl (50 mM), DTT (5 mM), MgCl2 (5 mM), BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) (100 μg/ml) and glycerol (10% v/v) (27, 54). Primer extension reaction was initiated by adding the individual dNTPs (final concentrations: 50–150 μM) into the mixture (total volume: 30 μl) and quenched by transferring aliquots (4 μl) into loading buffer containing EDTA (20 mM), bromophenol blue (0.05%) and xylene cyanol (0.05%) in 95% formamide at different time points. The extension products were denatured at 95 °C for 5 min and loaded onto a 20% (w/v) denaturing polyacrylamide gel containing 7 M urea. The products were electrophoresed by PAGE at 1800 V for 3 to 3.5 h in TBE buffer, and the results were visualized by using Typhoon FLA 7000 (GH Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA).

Steady state kinetics of single nucleotide incorporation

Steady-state kinetics for dATP or dCTP incorporation opposite dG or dT on a 17-mer template with either unmodified dC or DpC lesion was investigated by performing single nucleotide incorporation assays in the presence of hpol ƞ and increasing concentration of dATP or dCTP. Primer-template duplexes (33 nM) were mixed with hpol ƞ in different concentrations (0.13–1.65 nM) and the extension reactions were initiated by adding dATP or dCTP (5, 10, 25, 50, 150, 250, 500, 800 μM) and quenched in specific time points (0, 5, 15, 30 min). Primer extension products were visualized by using Typhoon FLA 7000 (GH Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA) and quantified by using ImageQuant TL version 8.0 (GE Healthcare). Steady-state kinetic parameters and their standard deviations were determined by using GraphPad Prism 10.0 (La Jolla, CA) via nonlinear regression analysis with the Michaelis-Menten model.

Data availability

All data are contained within the article.

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

J. H. T. B., P. Y., J. T., Q. Z., H. V. K., H. D. H., N. Y. T., and A. K. B. investigation; J. H. T. B., Q. Z., N. Y. T., and A. K. B. formal analysis; J. H. T. B., N. Y. T., and A. K. B. writing–original draft; N. Y. T., and A. K. B. conceptualization; N. Y. T., and A. K. B. writing–review and editing.

Funding and additional information

This work was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (R01 ES023350), USA. Funding for open access charge: National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by Patrick Sung

Supporting information

References

- 1.Barker S., Weinfeld M., Murray D. DNA-protein crosslinks: their induction, repair, and biological consequences. Mutat. Res. 2005;589:111–135. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tretyakova N.Y., Groehler A.t., Ji S. DNA-protein cross-links: formation, structural identities, and biological Outcomes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015;48:1631–1644. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basu A.K., Campbell C., Tretyakova N.Y. In: DNA Damage, DNA Repair and Disease. Dizdaroglu M.a.L., R S., editors. Royal Society of Chemistry; London, UK: 2021. DNA-protein cross-links: formation, genotoxicity and repair; pp. 154–174. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ide H., Shoulkamy M.I., Nakano T., Miyamoto-Matsubara M., Salem A.M. Repair and biochemical effects of DNA-protein crosslinks. Mutat. Res. 2011;711:113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ji S., Fu I., Naldiga S., Shao H., Basu A.K., Broyde S., et al. 5-Formylcytosine mediated DNA-protein cross-links block DNA replication and induce mutations in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:6455–6469. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakano T., Ouchi R., Kawazoe J., Pack S.P., Makino K., Ide H. T7 RNA polymerases backed up by covalently trapped proteins catalyze highly error prone transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:6562–6572. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.318410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakano T., Miyamoto-Matsubara M., Shoulkamy M.I., Salem A.M., Pack S.P., Ishimi Y., et al. Translocation and stability of replicative DNA helicases upon encountering DNA-protein cross-links. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:4649–4658. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.419358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tretyakova N.Y., Michaelson-Richie E.D., Gherezghiher T.B., Kurtz J., Ming X., Wickramaratne S., et al. DNA-reactive protein monoepoxides induce cell death and mutagenesis in mammalian cells. Biochemistry. 2013;52:3171–3181. doi: 10.1021/bi400273m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dizdaroglu M., Gajewski E. Structure and mechanism of hydroxyl radical-induced formation of a DNA-protein cross-link involving thymine and lysine in nucleohistone. Cancer Res. 1989;49:3463–3467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dizdaroglu M., Gajewski E., Reddy P., Margolis S.A. Structure of a hydroxyl radical induced DNA-protein cross-link involving thymine and tyrosine in nucleohistone. Biochemistry. 1989;28:3625–3628. doi: 10.1021/bi00434a071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Izzotti A., Cartiglia C., Taningher M., De Flora S., Balansky R. Age-related increases of 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine and DNA-protein crosslinks in mouse organs. Mutat. Res. 1999;446:215–223. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5718(99)00189-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quievryn G., Zhitkovich A. Loss of DNA-protein crosslinks from formaldehyde-exposed cells occurs through spontaneous hydrolysis and an active repair process linked to proteosome function. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:1573–1580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stingele J., Schwarz M.S., Bloemeke N., Wolf P.G., Jentsch S. A DNA-dependent protease involved in DNA-protein crosslink repair. Cell. 2014;158:327–338. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stingele J., Habermann B., Jentsch S. DNA-protein crosslink repair: proteases as DNA repair enzymes. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2015;40:67–71. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun Y., Saha L.K., Saha S., Jo U., Pommier Y. Debulking of topoisomerase DNA-protein crosslinks (TOP-DPC) by the proteasome, non-proteasomal and non-proteolytic pathways. DNA Repair (Amst) 2020;94 doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2020.102926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao R., Schellenberg M.J., Huang S.Y., Abdelmalak M., Marchand C., Nitiss K.C., et al. Proteolytic degradation of topoisomerase II (Top2) enables the processing of Top2.DNA and Top2.RNA covalent complexes by tyrosyl-DNA-phosphodiesterase 2 (TDP2) J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:17960–17969. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.565374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quinones J.L., Thapar U., Wilson S.H., Ramsden D.A., Demple B. Oxidative DNA-protein crosslinks formed in mammalian cells by abasic site lyases involved in DNA repair. DNA Repair (Amst) 2020;87 doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2019.102773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Essawy M., Chesner L., Alshareef D., Ji S., Tretyakova N., Campbell C. Ubiquitin signaling and the proteasome drive human DNA–protein crosslink repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51:12174–12184. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkad860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reardon J.T., Cheng Y., Sancar A. Repair of DNA-protein cross-links in mammalian cells. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:1366–1370. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.13.2892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu X., Zhao B.S., He C. TET family proteins: oxidation activity, interacting molecules, and functions in diseases. Chem. Rev. 2015;115:2225–2239. doi: 10.1021/cr500470n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gackowski D., Zarakowska E., Starczak M., Modrzejewska M., Olinski R. Tissue-specific differences in DNA Modifications (5-Hydroxymethylcytosine, 5-formylcytosine, 5-carboxylcytosine and 5-Hydroxymethyluracil) and their Interrelationships. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones P.A., Takai D. The role of DNA methylation in mammalian epigenetics. Science. 2001;293:1068–1070. doi: 10.1126/science.1063852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ito S., Shen L., Dai Q., Wu S.C., Collins L.B., Swenberg J.A., et al. Tet proteins can convert 5-methylcytosine to 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine. Science. 2011;333:1300–1303. doi: 10.1126/science.1210597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li F., Zhang Y., Bai J., Greenberg M.M., Xi Z., Zhou C. 5-Formylcytosine Yields DNA-protein cross-links in nucleosome core particles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:10617–10620. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b05495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ji S., Shao H., Han Q., Seiler C.L., Tretyakova N.Y. Reversible DNA-protein cross-linking at epigenetic DNA marks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed Engl. 2017;56:14130–14134. doi: 10.1002/anie.201708286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pujari S.S., Zhang Y., Ji S., Distefano M.D., Tretyakova N.Y. Site-specific cross-linking of proteins to DNA via a new bioorthogonal approach employing oxime ligation. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 2018;54:6296–6299. doi: 10.1039/c8cc01300d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomforde J., Fu I., Rodriguez F., Pujari S.S., Broyde S., Tretyakova N. Translesion synthesis past 5-formylcytosine-mediated DNA-peptide cross-links by hPoleta is dependent on the local DNA sequence. Biochemistry. 2021;60:1797–1807. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.1c00130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Livneh Z., Ziv O., Shachar S. Multiple two-polymerase mechanisms in mammalian translesion DNA synthesis. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:729–735. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.4.10727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu F., Yang Y., Zhou Y. Polymerase Delta in eukaryotes: how is it Transiently Exchanged with specialized DNA polymerases during translesion DNA synthesis? Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2018;19:790–804. doi: 10.2174/1389203719666180430155625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hishiki A., Hashimoto H., Hanafusa T., Kamei K., Ohashi E., Shimizu T., et al. Structural basis for novel interactions between human translesion synthesis polymerases and proliferating cell nuclear antigen. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:10552–10560. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809745200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chandani S., Lee C.H., Loechler E.L. Free-energy perturbation methods to study structure and energetics of DNA adducts: results for the major N2-dG adduct of benzo[a]pyrene in two conformations and different sequence contexts. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2005;18:1108–1123. doi: 10.1021/tx049646l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cai Y., Patel D.J., Geacintov N.E., Broyde S. Dynamics of a benzo[a]pyrene-derived guanine DNA lesion in TGT and CGC sequence contexts: enhanced mobility in TGT explains conformational heterogeneity, flexible bending, and greater susceptibility to nucleotide excision repair. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;374:292–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cai Y., Patel D.J., Geacintov N.E., Broyde S. Differential nucleotide excision repair susceptibility of bulky DNA adducts in different sequence contexts: hierarchies of Recognition signals. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;385:30–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.09.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mak W.B., Fix D. DNA sequence context affects UV-induced mutagenesis in Escherichia coli. Mutat. Res. 2008;638:154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shriber P., Leitner-Dagan Y., Geacintov N., Paz-Elizur T., Livneh Z. DNA sequence context greatly affects the accuracy of bypass across an ultraviolet light 6-4 photoproduct in mammalian cells. Mutat. Res. 2015;780:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singer B., Chavez F., Goodman M.F., Essigmann J.M., Dosanjh M.K. Effect of 3′ flanking neighbors on kinetics of pairing of dCTP or dTTP opposite O6-methylguanine in a defined primed oligonucleotide when Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I is used. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1989;86:8271–8274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.21.8271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dosanjh M.K., Galeros G., Goodman M.F., Singer B. Kinetics of extension of O6-methylguanine paired with cytosine or thymine in defined oligonucleotide sequences. Biochemistry. 1991;30:11595–11599. doi: 10.1021/bi00113a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delaney J.C., Essigmann J.M. Effect of sequence context on O(6)-methylguanine repair and replication in vivo. Biochemistry. 2001;40:14968–14975. doi: 10.1021/bi015578f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zahn K.E., Wallace S.S., Doublie S. DNA polymerases provide a canon of strategies for translesion synthesis past oxidatively generated lesions. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2011;21:358–369. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weerasooriya S., Jasti V.P., Basu A.K. Replicative bypass of abasic site in Escherichia coli and human cells: similarities and differences. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yao N., O'Donnell M. Bacterial and eukaryotic replisome Machines. JSM Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2016;3:1013. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Naldiga S., Ji S., Thomforde J., Nicolae C.M., Lee M., Zhang Z., et al. Error-prone replication of a 5-formylcytosine-mediated DNA-peptide cross-link in human cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2019;294:10619–10627. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.008879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Venkatarangan L., Sivaprasad A., Johnson F., Basu A.K. Site-specifically located 8-amino-2′-deoxyguanosine: thermodynamic stability and mutagenic properties in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:1458–1463. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.7.1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tan X., Suzuki N., Johnson F., Grollman A.P., Shibutani S. Mutagenic properties of the 8-amino-2′-deoxyguanosine DNA adduct in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:2310–2314. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.11.2310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kamiya H., Kurokawa M., Makino T., Kobayashi M., Matsuoka I. Induction of action-at-a-distance mutagenesis by 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine in DNA pol lambda-knockdown cells. Genes Environ. 2015;37:10. doi: 10.1186/s41021-015-0015-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kamiya H., Yamazaki D., Nakamura E., Makino T., Kobayashi M., Matsuoka I., et al. Action-at-a-distance mutagenesis induced by oxidized guanine in Werner syndrome protein-reduced human cells. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2015;28:621–628. doi: 10.1021/tx500418m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gentil A., Le Page F., Margot A., Lawrence C.W., Borden A., Sarasin A. Mutagenicity of a unique thymine-thymine dimer or thymine-thymine pyrimidine pyrimidone (6-4) photoproduct in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:1837–1840. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.10.1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hendel A., Ziv O., Gueranger Q., Geacintov N., Livneh Z. Reduced efficiency and increased mutagenicity of translesion DNA synthesis across a TT cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer, but not a TT 6-4 photoproduct, in human cells lacking DNA polymerase eta. DNA Repair (Amst) 2008;7:1636–1646. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Colis L.C., Raychaudhury P., Basu A.K. Mutational specificity of gamma-radiation-induced guanine-thymine and thymine-guanine intrastrand cross-links in mammalian cells and translesion synthesis past the guanine-thymine lesion by human DNA polymerase eta. Biochemistry. 2008;47:8070–8079. doi: 10.1021/bi800529f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pande P., Ji S., Mukherjee S., Scharer O.D., Tretyakova N.Y., Basu A.K. Mutagenicity of a model DNA-peptide cross-link in human cells: roles of translesion synthesis DNA polymerases. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2017;30:669–677. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.6b00397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu J., Li L., Wang P., You C., Williams N.L., Wang Y. Translesion synthesis of O4-alkylthymidine lesions in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:9256–9265. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Du H., Leng J., Wang P., Li L., Wang Y. Impact of tobacco-specific nitrosamine-derived DNA adducts on the efficiency and fidelity of DNA replication in human cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2018;293:11100–11108. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.003477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pande P., Malik C.K., Bose A., Jasti V.P., Basu A.K. Mutational analysis of the C8-guanine adduct of the environmental carcinogen 3-nitrobenzanthrone in human cells: critical roles of DNA polymerases eta and kappa and Rev1 in error-prone translesion synthesis. Biochemistry. 2014;53:5323–5331. doi: 10.1021/bi5007805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim J., Song I., Jo A., Shin J.H., Cho H., Eoff R.L., et al. Biochemical analysis of six genetic variants of error-prone human DNA polymerase ι involved in translesion DNA synthesis. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2014;27:1837–1852. doi: 10.1021/tx5002755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are contained within the article.