Keywords: repeated bout effect, resistance training, skeletal muscle, strength, transcriptomics

Abstract

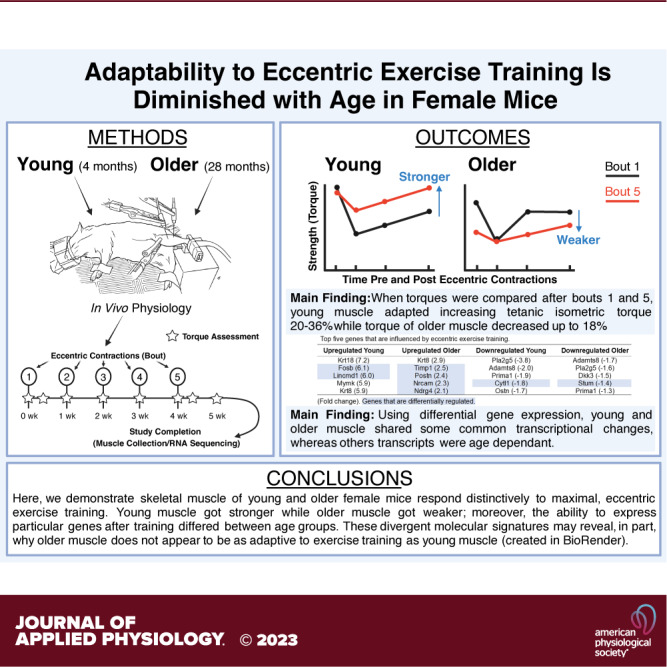

The ability of skeletal muscle to adapt to eccentric contractions has been suggested to be blunted in older muscle. If eccentric exercise is to be a safe and efficient training mode for older adults, preclinical studies need to establish if older muscle can effectively adapt and if not, determine the molecular signatures that are causing this impairment. The purpose of this study was to quantify the extent age impacts functional adaptations of muscle and identify genetic signatures associated with adaptation (or lack thereof). The anterior crural muscles of young (4 mo) and older (28 mo) female mice performed repeated bouts of eccentric contractions in vivo (50 contractions/wk for 5 wk) and isometric torque was measured across the initial and final bouts. Transcriptomics was completed by RNA-sequencing 1 wk following the fifth bout to identify common and differentially regulated genes. When torques post eccentric contractions were compared after the first and fifth bouts, young muscle exhibited a robust ability to adapt, increasing isometric torque 20%–36%, whereas isometric torque of older muscle decreased up to 18% (P ≤ 0.047). Using differential gene expression, young and older muscles shared some common transcriptional changes in response to eccentric exercise training, whereas other transcripts appeared to be age dependent. That is, the ability to express particular genes after repeated bouts of eccentric contractions was not the same between ages. These molecular signatures may reveal, in part, why older muscles do not appear to be as adaptive to exercise training as young muscles.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY The ability to adapt to exercise training may help prevent and combat sarcopenia. Here, we demonstrate young mouse muscles get stronger whereas older mouse muscles become weaker after repeated bouts of eccentric contractions, and that numerous genes were differentially expressed between age groups following training. These results highlight that molecular and functional plasticity is not fixed in skeletal muscle with advancing age, and the ability to handle or cope with physical stress may be impaired.

INTRODUCTION

Age-related skeletal muscle weakness is a well-known predictor of adverse health events in older adults (1–8). In recognition of the clinical significance of weakness, the most recent consensus definitions of sarcopenia now prioritize muscle weakness as a key characteristic of sarcopenia (9). Similarly, weakness measured via grip strength is also a clinical sign and symptom of phenotypic frailty (10). It is clear that “being weak” and “becoming weak” are critical components of unhealthy aging (11–13). Therefore, interventions that increase muscle strength are vital to combating sarcopenia and frailty. Currently, the most effective, nonpharmacological intervention known to improve muscle strength is resistance exercise training (14–18).

Traditional resistance exercise training involves both shortening (concentric) and lengthening (eccentric) contractions. Of these, eccentric contractions (muscle lengthening while active) produce the most force and are the least metabolically demanding (for a given load) (19, 20). Therefore, it has been suggested that eccentric exercise training could be a promising strategy to attenuate or combat weakness observed in older adults (19, 21–23). However, despite eccentric exercise training being a known method to increase strength (24, 25), unaccustomed eccentric contractions can result in transient bouts of weakness. Eccentric contraction-induced muscle weakness is immediate and can take days to weeks to fully recover depending on the intensity and duration of the exercise (26–30). However, a salient component of eccentric exercise training is the adaptations that occur when the activity is repeated, which can manifest as attenuated strength deficits, enhanced rates of strength recovery, and overall improvements in baseline strength (25, 28, 31–35).

Skeletal muscle function typically improves after older adults resistance exercise train (14–18). However, human and rodent data also indicate that older muscles are less responsive to training compared with younger muscles, exhibiting a diminished ability to adapt or even, a complete loss of adaptation (36–44). It was recently demonstrated that although resistance training in older adults resulted in an overall increase in isometric strength (i.e., group mean), large interindividual variability was observed, and nearly a third of the subjects did not improve or got weaker (45). It therefore appears repeated bouts of eccentric contractions may result in prolonged and possibly irreversible weakness in some older adults. In order for eccentric exercise training to be considered a safe and efficient mode of strength training for older adults, a better understanding of how age influences skeletal muscle adaptability is required. The purpose of this preclinical study was to measure how adaptive potential or the ability to adapt differs in young and older mice, with a specific focus on functional and molecular signatures. Thus, an in vivo model of eccentric exercise training was utilized to quantify changes in skeletal muscle strength and was complemented with transcriptomic analyses to identify molecular changes associated with adaptation (or lack thereof). It was hypothesized that older mice would not adapt to the same extent as young mice and muscle from each age group would present distinct genetic signatures after training.

METHODS

Ethical Approval and Animals Models

Female wild-type mice (C57BL/6) were obtained from the National Institute of Aging (NIA, Bethesda, MD) at 3 and 20–22 mo of age. Mice were aged locally in the event they were designated for the “older” testing group. Mice were assigned to young (n = 10) and older (n = 7) age groups that corresponded to 3–4 and 27–28 mo of age, which translates to human years of ∼20 (young) and 70–80 (older), respectively (46). All mice were housed in groups of up to five animals per cage, supplied with food and water ad libitum, and maintained in a room at 20°C–22°C with a 12-h photoperiod. By study completion, mice had aged five weeks. In the event a mouse died or could not perform a bout of eccentric contractions due to issues with electrode placement, it was excluded from any additional testing. Samples sizes at study completion were n = 8 and n = 5 for the young and older mice, respectively. After the final testing period, mice were euthanized with an overdose of isoflurane followed by cervical dislocation. All animal care and use procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Experimental Design

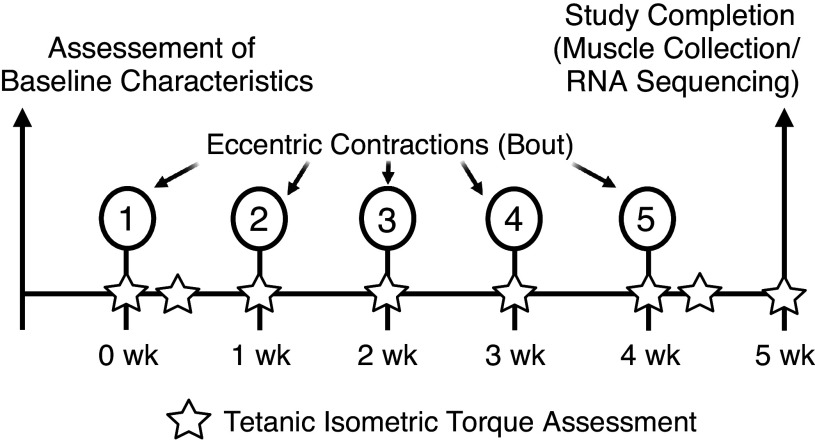

General characteristics of functional health were first assessed via rotarod time (measure of walking speed, endurance, balance) and dorsiflexor torque (measure of strength) before subjecting muscles to an eccentric contraction training protocol (Fig. 1). To mimic in vivo eccentric exercise, the left dorsiflexors (anterior crural muscles; tibialis anterior, extensor digitorum longus, and extensor hallucis) performed five sessions of 50 maximal eccentric contractions, each separated by 7 days (day 7) (47). The sessions consisted of testing in vivo tetanic isometric torque of the left dorsiflexors immediately before (pre) and after (post) each bout of eccentric contractions/exercise. For the first and fifth bouts, in vivo isometric torque was also assessed on day 2. The last assessment of isometric torque was completed 7 days following the fifth bout (Fig. 1). A subset of data obtained for the young mice using this specific eccentric exercise training regimen come from Sidky et al. (47).

Figure 1.

Experimental timeline. The left dorsiflexors were subjected to five sessions of 50 maximal eccentric contractions, each separated by 7 days (day 7). The sessions consisted of testing in vivo tetanic isometric torque of the left hindlimb immediately before (Pre) and after each bout of eccentric contractions (Post), and isometric torque 2 days (day 2) after the first and fifth bouts was also measured. The last assessment of isometric torque was completed 7 days following the fifth bout, and then the right and left tibialis anterior and extensor digitorum longus muscles were immediately dissected and used for RNA-sequencing and transcriptomic analyses. No eccentric contractions were performed on week 5, only assessment of tetanic isometric torque. Figure created using BioRender.

To ascertain if age impacted the muscle’s ability to adapt to repeated bouts of eccentric contractions, adaptive potential was computed for each mouse and then age groups were compared. Adaptive potential was calculated as [(bout 5 isometric torque/bout 1 isometric torque) − 1] and expressed as a percentage, and computed for the following timepoints: post, day 2, and day 7. That said, a positive and negative percent change would be interpreted as increase and decrease in torque after training, respectively, for each selected timepoint. Following the final assessment of isometric torque (7 days after the fifth bout), the right and left right tibialis anterior and extensor digitorum longus muscles were collected and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen for transcriptomic analyses (Fig. 1). To note, the contralateral right muscles did not complete any isometric or eccentric contractions.

EXPERIMENTAL METHODOLOGY

Rotarod Time

Mice warmed up on a rotarod by walking at 4 rpm for 30 s, at which point rotarod speed increased 1 rpm every 8 s up to 21 rpm over a 136 s period. Rotarod speed then remained at 21 rpm until 300 s, which was also set as the maximal duration. Time, in seconds, was recorded when the mouse was unable to sustain the rotation speed of the rotarod (or if they reached 300 s). Each mouse performed three trials with a 10-min rest period in between each trial. The best score of these trials was used as rotarod time.

Tetanic Isometric Torque

Tetanic isometric torque of the left anterior crural muscles was measured in vivo as previously described (48, 49). Briefly, mice were initially anesthetized in an induction chamber using isoflurane and then maintained by inhalation of 1.5% isoflurane mixed with oxygen at a flow rate of 125 mL/min. To preserve core body temperature between 35°C and 37°C, mice were placed on a temperature-controlled platform. The left knee was clamped, and the left foot was secured to an aluminum “shoe” that is attached to the shaft of an Aurora Scientific 300B servomotor (Aurora Scientific, ON, Canada). Sterilized platinum needle electrodes were inserted through the skin for stimulation of the left common peroneal nerve. Stimulation voltage and needle electrode placement were then optimized and isometric torque (150 ms train of 0.1 ms pulses at 250 Hz) was recorded.

Eccentric Contractions

The left anterior crural muscles were injured (i.e., trained) by performing maximal, electrically stimulated eccentric contractions in vivo (49, 50). During each eccentric contraction, the foot was passively rotated from 0° (positioned perpendicular to tibia) to 19° of dorsiflexion where the anterior crural muscles performed a prelengthening 100-ms isometric contraction followed by an additional 20 ms of stimulation whereas the foot was rotated from 19° of dorsiflexion to 19° of plantarflexion at 2000°/s. A 5-min rest after the eccentric contraction protocol was given before reassessing tetanic isometric torque (i.e., post).

Generation and Preprocessing of RNA-Sequencing Data

RNA extraction, library preparation, and next-generation sequencing were performed by the Beijing Genomics Institute (Hong Kong). RNA concentration and integrity of each sample were determined using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). All samples met the requirements for library preparation (RIN ≥ 7.0, 28S/18S ≥ 1.0) and were sequenced to generate 100-bp paired end reads (unstranded) using the DNBseq platform. The quality of cleaned reads was established using FastQC (Babraham Bioinformatics), and since all reads were deemed to be of good quality (median per base quality scores > 30 and no overrepresented sequences or adapter sequences), no additional filtering or trimming of reads was required. Reads were subsequently aligned to the mouse (Mus musculus) reference genome (GRCm39, Ensembl) using HISAT2 (51). Reads mapping to known exons were counted in an unstranded fashion using featureCounts (52) with the mouse (Mus musculus) genome annotation used as a reference (GRCm39, Ensemble release 105). Genes displaying low expression is defined as a read count of <10 in 50% of all 18 samples (four young and five older mice, left and right tibialis anterior and extensor digitorum longus muscles). In total, 14,553 genes were used for downstream informatic analysis.

Differential Expression Analysis

Differential gene expression analysis was conducted using DEseq2 (53). To account for both between and within effects, a “Group-specific condition effects, individuals nested within groups” mixed design was performed, in accordance with the developers’ recommendations (DESeq2 Vignette). Wald tests were used to identify significant differentially expressed genes between the exercised (left) and nonexercised (right) leg for each age group. The Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) procedure was used to control for false-discovery rate. Genes with a BH-corrected P < 0.10 were defined as differentially expressed. Inbuilt R functions intersect and setdiff were used to identify common and uniquely regulated genes between age, respectively.

Functional Annotation of Differentially Expressed Genes

Functional annotation analysis was conducted using clusterProfiler (54). Functional characteristics of differentially expressed genes were identified by testing their gene lists for enrichment of Gene Ontology terms (GO), with the background being the genes used as input to differential expression analysis. All three GO categories (biological process, cellular component, and molecular function) were considered during analysis. Enriched GO terms were defined as BH-corrected P < 0.05 enriched for at least two genes, as described previously (55).

Statistical Analyses

To detect differences between variables assessed in young and older mice, independent t tests were performed. Two-way factorial ANOVAs were utilized to measure 1) changes in tetanic isometric torque between age groups (young vs. older) and training session (day or bout) or 2) changes within age group (young or older) to assess recovery of torque after the eccentric contractions across the training sessions (day vs. bout). Specifically, when comparing changes over the duration of the study, isometric tetanic torque was measured in the same mice for all timepoints. When significant ANOVAs were discovered, a Holm-Sidak or Dunnett post hoc test was performed. An α level of 0.05 was used for all analyses. Values are presented as means ± SD. All statistical testing was performed using SigmaPlot version 12.5 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA).

RESULTS

Baseline Body Mass, Rotarod Time, and Tetanic Isometric Torque

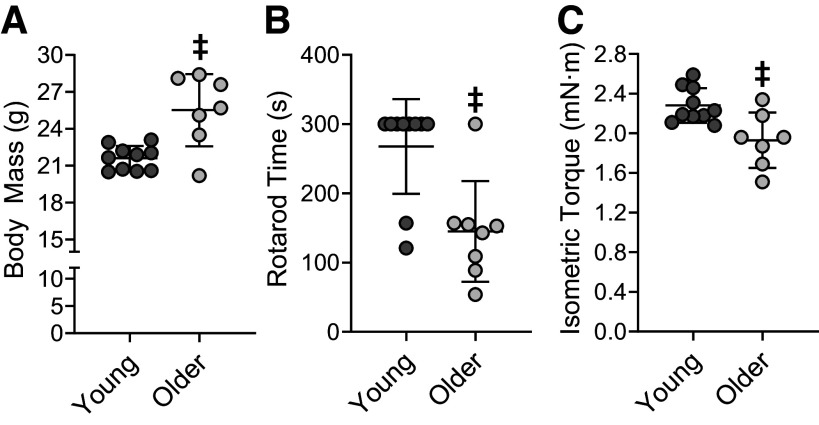

Body composition and physical function have previously been shown to fluctuate with age in the C57BL/6 mouse strain (56–58). Here, we measured body mass, rotarod time and isometric torque of the left dorsiflexors to determine baseline differences between young and older female mice. The body mass of older mice was greater than that of young mice (P = 0.001; Fig. 2A). Older mice spent less time on the rotarod compared with young mice (P = 0.002; Fig. 2B). Moreover, older mice produced less tetanic isometric torque than young mice (P = 0.006; Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Baseline characteristics in young and older mice. Body mass (A), rotarod time (B), and tetanic isometric torque (C) before performing repeated bouts of eccentric contractions. Rotarod time was recorded when the mouse was unable to sustain the rotation speed of the rotarod (or if they reached 300 s). Isometric torque of the left dorsiflexors was measured during a maximal in vivo tetanic contraction (150 ms train at 250 Hz). Baseline testing occurred at 3–4 (n = 10) and 27–28 (n = 7) months of age for young and older mice, respectively. Values are means ± SD. ‡Significantly different from young mice (P < 0.05).

Tetanic Isometric Torque before and after Training

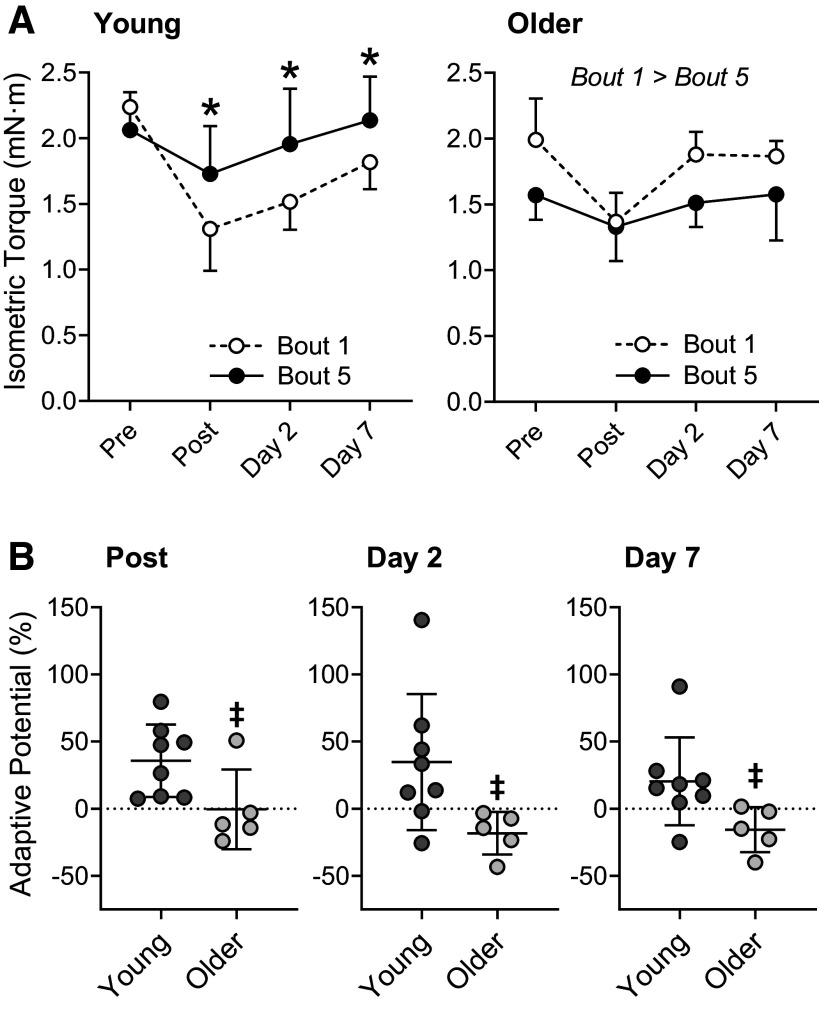

To assess how the left anterior crural muscles responded to exercise across age, tetanic isometric torques produced over the final bout of eccentric contractions were compared with the corresponding timepoints obtained during the initial bout (Fig. 3A). Tetanic isometric torque for bouts 1 and 5 can be viewed as untrained and trained strength outputs, respectively. Timepoints compared between bouts 1 and 5 included immediately after the eccentric contractions (i.e., post), and 2 and 7 days into recovery. Regardless of training status (i.e., bout 1 vs. bout 5), 50 maximal eccentric contractions in vivo reduced torque immediately after each bout (P ≤ 0.002) that began to recover by day 2. However, an interaction was detected for young mice (P = 0.017); isometric torques were greater during bout 5 at post, day 2 and day 7 when compared torque obtained during bout 1 (P ≤ 0.040; Fig. 3A). Among older mice, isometric torques produced over the final bout were less than that of the initial bout (P < 0.001); no interaction was detected (P = 0.313).

Figure 3.

Functional changes to eccentric exercise training in young and older mice. A: tetanic isometric torque before and after the initial (first) and final (fifth) bouts of training. B: adaptive potential as measured by a percent change from the initial to final bouts at post, day 2, and day 7. Post represents torque obtained immediately after the eccentric contractions were performed whereas days 2 and 7 are torques recorded days after the eccentric contractions. Dashed line in B signifies no change, or “0” adaptive potential. n = 8 and n = 5 for young and older mice, respectively. Values are means ± S D. *Significantly different from corresponding timepoint of the initial bout (P < 0.05). ‡Significantly different from young mice (P < 0.05).

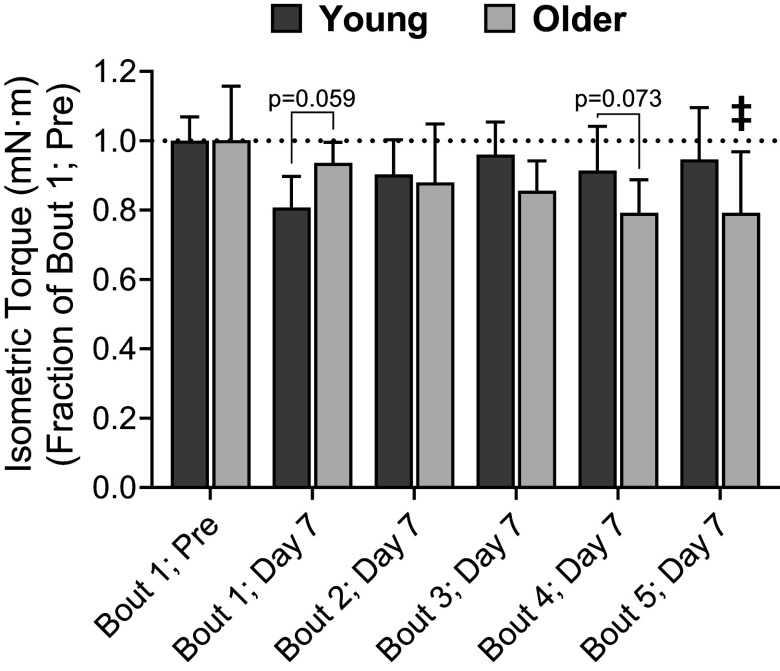

By comparing tetanic isometric torque 7 days after each bout to torque produced before any eccentric contractions were completed (i.e., bout 1; pre), we were able to approximate when age-related weakness or lack of recovery occurred during the training protocol (Fig. 4). Seven days following bout 1, there was a trend for older muscle to recover quicker than young muscle (P = 0.059). In contrast to bout 1, the ability to recover following subsequent bouts declined in older muscle and improved in young muscle. There was trend for young muscle to recover better than older muscle 7 days following bout 4 (P = 0.073) that reach statistical significance by bout 5 (P = 0.026)

Figure 4.

Tetanic isometric torque 7 days after each bout expressed relative torque produced during bout 1; pre. Each age group’s torque for bout 1; pre is set to 1.0 and signified by a dotted line. Bout 1; pre represents torque obtained immediately before the performance of eccentric contractions at bout 1, whereas day 7 values were recorded 7 days after each bout of eccentric contractions (bouts 1–5). n = 8 and n = 5 for young and older mice, respectively. Values are means ± SD. ‡Significantly different from young mice (P < 0.05). Data obtained from Sidky et al. (47), with permission from Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

Ability to Adapt to Repeated Bouts of Eccentric Contractions (Adaptive Potential)

Adaptive potential was calculated as the percent change at post, day 2, and day 7 from the initial to final bout and then compared between groups to determine if aging impaired the muscle’s ability to adapt after repetitive bouts of eccentric contractions (Fig. 3B). When examining torque values after the first and fifth bouts of eccentric contractions, young muscle exhibited a robust ability to adapt across all timepoints, increasing on average 20%–36% whereas isometric torque of older muscle decreased up to 18%. Consequently, adaptive potential was less in older muscle compared with young muscle at post (P = 0.044), day 2 (P = 0.047), and day 7 (P = 0.045).

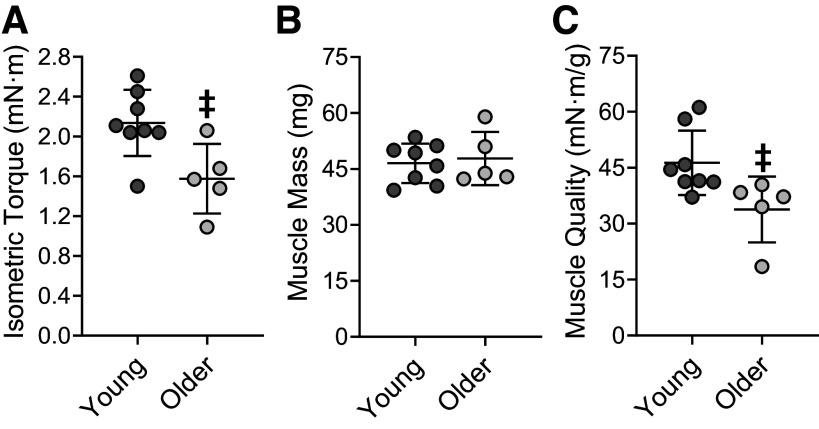

Muscle Quality following Eccentric Exercise Training

To assess muscle quality following repeated bouts of eccentric contractions, tetanic isometric torque of the left anterior crural muscles was normalized to muscle mass of the left tibialis anterior and extensor digitorum longus muscles. Specifically, tetanic isometric torque was 26% lower in older mice compared with young mice (P = 0.015; Fig. 5A), whereas muscle mass did not differ between ages (P = 0.716; Fig. 5B). Together, these variables resulted in a loss of muscle quality that paralleled tetanic isometric torque; muscle quality was 27% lower in older muscle versus young muscle (P = 0.028; Fig. 5C). The right tibialis anterior and extensor digitorum longus muscles weighed 47.6 ± 1.2 mg in older mice and was 28% greater than the 37.1 ± 6.1 mg observed in the young mice (P = 0.004)

Figure 5.

Muscle quality in young and older mice following eccentric exercise training. Tetanic isometric torque (A), muscle wet mass (B), and muscle quality (C) 7 days following the final bout of eccentric contractions. Isometric torque of the left dorsiflexors was measured during an in vivo tetanic contraction (150 ms train at 250 Hz). The muscle wet mass was of the left tibialis anterior and extensor digitorum longus muscles. Muscle quality was calculated by comparing tetanic isometric torque to that of muscle mass. n = 8 and n = 5 for young and older mice, respectively. Values are means ± SD. ‡Significantly different from young mice (P < 0.05).

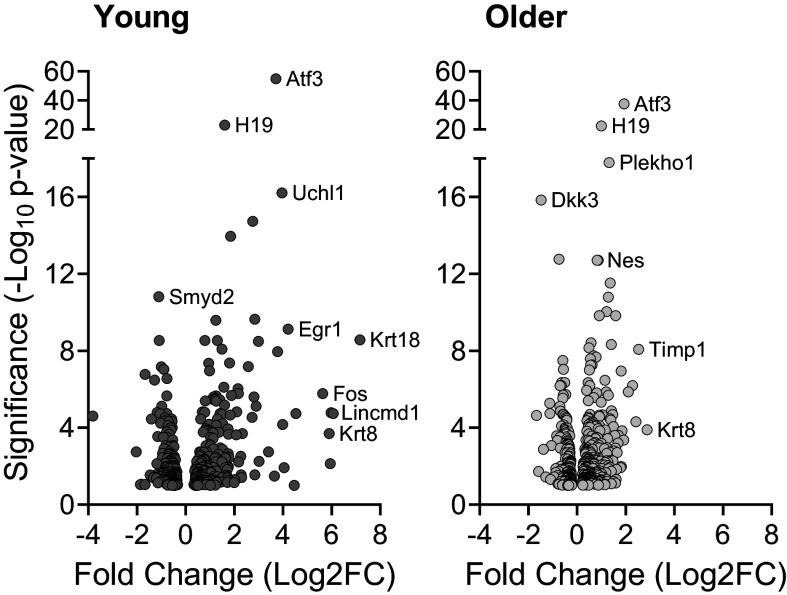

Transcriptional Profiles due to Eccentric Exercise Training

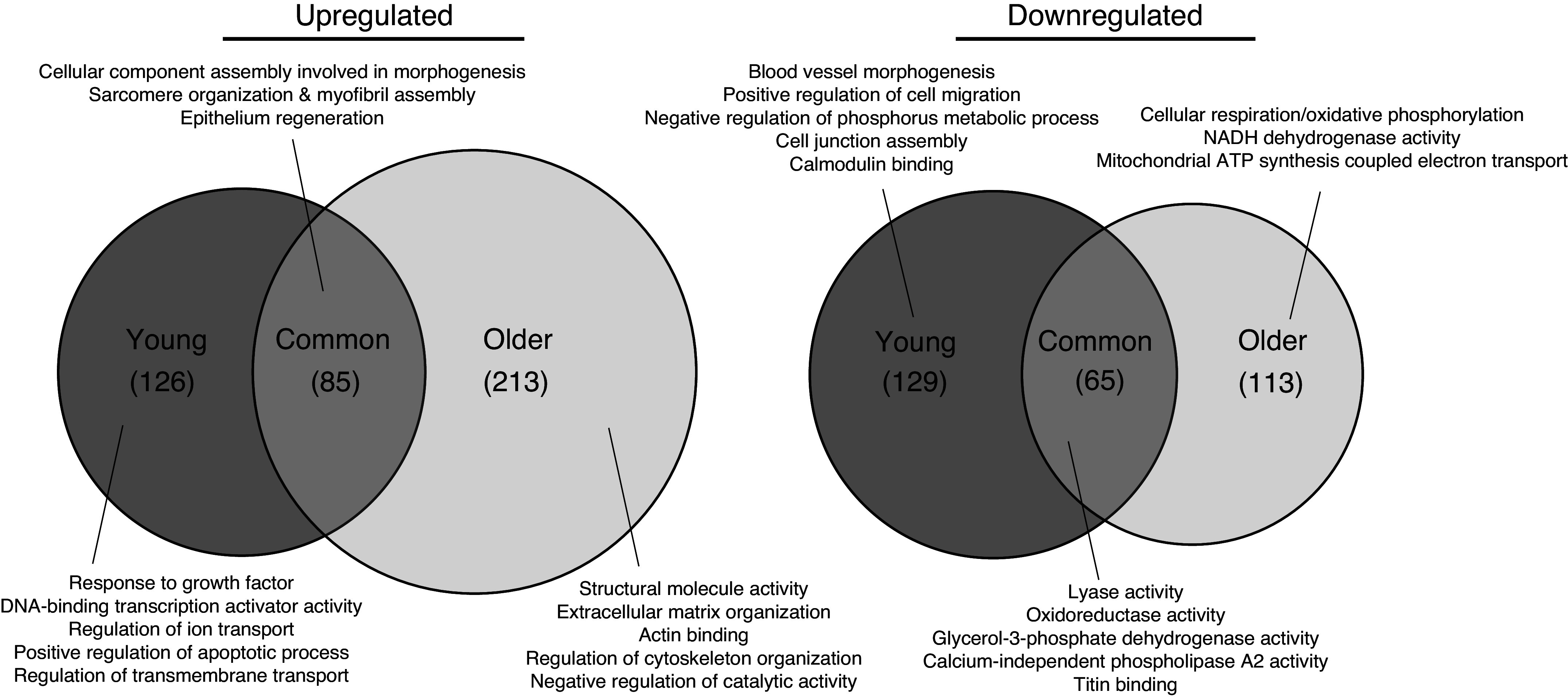

The impact of eccentric training on the muscle transcriptome was determined by comparing changes in the left trained muscle to the right contralateral (untrained) muscle for each mouse, then overlaying the training effect across the two age groups (young vs. older). Differentially expressed genes were assessed based on significance and magnitude of change (Fig. 6 and Supplemental Material; https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24049641.v1). The top five genes that differed between untrained and trained muscle were sorted by significance (i.e., P value) and fold-change (Tables 1 and 2, respectively). Eccentric exercise training altered the expression of more genes in older muscle (476) compared with young muscle (405), which was driven by the greater number of genes upregulated in older muscle (298) versus that of young muscle (211; Fig. 7). In general, Atf3, H19, and Krt8 increased due to eccentric exercise in both age groups, yet all appeared to respond greater in the young muscle (i.e., higher fold-changes; Table 2 and Supplemental Material). The genes ler2, Sat1, Fsob, and Lincmd1 were uniquely upregulated in trained young muscle whereas Nes, Timp1, Postn, Nrcam, and Ndrg4 were uniquely upregulated in trained older muscle. Smyd2, Gpx3, Pla2g5, and Adamts8 decreased in trained muscle of both age groups. Uniquely downregulated genes included Cytl1 for trained young muscle and Slc25a25 and Stum for older trained muscle.

Figure 6.

Significantly upregulated and downregulated genes in young and older muscle after eccentric exercise training. Volcano plots are Log2 fold-changes (Log2FC) plotted against significance (−Log10 P value). To obtain the gene response of training, the left trained muscle was compared with the right untrained muscle. The tibialis anterior and extensor digitorum longus muscles were used for analyses. Examples of genes with a high significance and/or fold-change are listed for each age group. n = 4 and n = 5 for young and older mice, respectively.

Table 1.

Top five genes that are influenced after eccentric exercise training—sorted by significance

| Upregulated Young | Upregulated Older | Downregulated Young | Downregulated Older |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atf3 (3.7) | Atf3 (1.9) | Smyd2 (−1.1) | Dkk3 (−1.5) |

| H19 (1.6) | H19 (1.0) | Timp3 (−1.1) | Slc25a25 (−0.7) |

| Uchl1 (4.0) | Plekho1 (1.3) | Car3 (−1.0) | Gpx3 (−0.6) |

| Ier2 (2.8) | Lmod2 (0.9) | Gpx3 (−0.9) | Smyd2 (−0.6) |

| Sat1 (1.8) | Nes (0.8) | Ostn (−1.7) | Smox (−0.6) |

The numbers inside of parentheses are fold-change. Boldface italic represents genes that are differentially regulated.

Table 2.

Top five genes that are influenced by eccentric exercise training—sorted by fold-change

| Upregulated Young | Upregulated Older | Downregulated Young | Downregulated Older |

|---|---|---|---|

| Krt18 (7.2) | Krt8 (2.9) | Pla2g5 (−3.8) | Adamts8 (−1.7) |

| Fosb (6.1) | Timp1 (2.5) | Adamts8 (−2.0) | Pla2g5 (−1.6) |

| Lincmd1 (6.0) | Postn (2.4) | Prima1 (−1.9) | Dkk3 (−1.5) |

| Mymk (5.9) | Nrcam (2.3) | Cytl1 (−1.8) | Stum (−1.4) |

| Krt8 (5.9) | Ndrg4 (2.1) | Ostn (−1.7) | Prima1 (−1.3) |

The numbers inside of parentheses are fold-change. Boldface italic represents genes that are differentially regulated.

Figure 7.

Age-(in)dependent gene-level responses to repeated eccentric contractions. Venn diagrams depict the degree of overlap between upregulated and downregulated genes following eccentric exercise in young and older tibialis anterior and extensor digitorum longus muscles that includes enriched GO terms for each corresponding unique/common gene set. n = 4 and n = 5 for young and older mice, respectively.

GO term enrichment was used to elucidate the functional roles of genes regulated by training in young and/or older muscle. Common to both age groups was an upregulation in gene associated with myofibril/sarcomere development, organization, and assembly and a downregulation in genes related to lyase, oxidoreductase, and glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase activity (Fig. 7). Unique to young muscle following eccentric exercise training was an upregulation in genes related to the growth factor response and DNA-binding transcription activity and a downregulation in blood vessel morphogenesis related genes (Fig. 7). Unique to older trained muscle was an upregulation in extracellular matrix-related genes and a downregulation in genes within cellular respiration/oxidative phosphorylation (Fig. 7). The full list of differentially expressed genes and their enriched GO terms is provided in Supplemental Material.

DISCUSSION

In theory, if skeletal muscle cannot properly adapt to repetitive bouts of eccentric contractions, sarcopenia and frailty will progressively develop and/or the ability to overcome sarcopenia and frailty will be impaired. Thus, the purpose of this study was to measure how adaptive potential was influenced by age in female mice, with a specific focus on skeletal muscle functional and molecular signatures. Two primary findings were observed, both of which confirmed our initial hypothesis. First, the ability to adapt to repeated eccentric contractions was blunted in older compared with young muscle. Second, using differential gene expression, we identified that although young and older muscle share some common transcriptional changes in response to eccentric exercise training, other genes appear to be age dependent. That is, the ability to express particular genes after repeated bouts of eccentric contractions was not the same in young and older muscle. These molecular signatures may reveal, in part, why older muscles do not appear to be as adaptive to exercise training as young muscles.

Eccentric exercise promotes a myriad of benefits that can manifest as increased basal strength, attenuated postcontraction strength loss, and enhanced rates of strength recovery. Although older muscles have been reported to positively respond to resistance training or physical exercise (14–18), adaptability appears to be diminished in older humans and rodents when compared with their younger counterparts (36–44). Here, we observed that older mouse muscle was weaker following repeated bouts of maximal eccentric contractions while young mouse muscle adapted. Specifically, young mouse muscle got stronger after the final bout (relative to the initial bout) when assessed immediately post eccentric contractions and 2 and 7 days into recovery (Fig. 3). Our findings parallel those observed in aged rats subjected to chronic administration of high-intensity stretch-shortening contractions, in which 30-mo-old rats maladapted after training (38, 40, 42). Though the present results align with previous studies that utilized stretch-shortening contractions, each laboratory’s exercise protocol varied across several contraction parameters (e.g., velocity, duration, and number) that resulted in differing degrees of strength loss and recovery. To limit eccentric contraction-induced damage and weakness (i.e., maladaptation), Greig et al. (39) had young (19–30 yr) and older (76–82 yr) women complete a training program that consisted of maximal isometric contractions and reported strength gains were blunted in the older women, 16% gains in older versus 27% gains in young. Similarly, Slivka et al. (43) demonstrated that the capacity of >80-yr-old men to gain strength after resistance training was limited, not only when compared with young men (∼20 yr) but also 70 yr old men. These data support the theory that advanced age is associated with a reduction of skeletal muscle plasticity and, if chronically repeated, could lead or contribute to sarcopenia and frailty in vulnerable individuals. The previous statement would be particularly translatable if the training regimen was not administered and/or prescribed correctly.

To characterize potential underlying molecular mechanisms that change with eccentric exercise across age, we examined similarities and differences in the transcriptional response in trained versus untrained muscle of young and older mice. In both age groups, repeated bouts of eccentric contractions resulted in molecular indices of skeletal muscle stress as highlighted by increased expression Atf3 and H19 (Table 1 and Fig. 6). The activating transcription factor 3 (Atf3) gene is induced by various stress signals, and has been characterized as an “adaptive response” gene for cells to cope with extra- and/or intracellular changes (59). Indeed, aerobic exercise (e.g., treadmill running) or eccentric contractions have previously been shown to increase Atf3 expression in rodent and human skeletal muscle (60–66). Intriguingly, Atf3 is often one of the highest among all upregulated genes following exercise. Fernández-Verdejo et al. (62) established the physiological importance of the Atf3 gene by demonstrating that some molecular adaptations to training were impaired in skeletal muscle of Atf3 knockout mice and mediated by the ability of Atf3 to regulate exercise-induced inflammatory genes. As with Atf3, the long-noncoding RNA H19 is also thought to be an exercise responsive gene. H19 is highly expressed in adult muscle tissues and upregulated during myoblast differentiation, regeneration, and exercise training (67–69). In the present study, Atf3 and H19 were the top upregulated genes (via P values) in young and older muscles after training (Table 1 and Fig. 6); yet large functional differences were observed between ages (Figs. 3–5). It is possible that despite upregulation of these stress-responsive genes, increasing age may have blunted their ability to produce meaningful effects or that other genes are needed to drive the robust adaptations observed in young muscle.

Several differently regulated genes were found between ages when comparing genes that were expressed because of eccentric exercise training, particularly genes that were upregulated rather than downregulated (Tables 1 and 2, Fig. 6). Examples of genes previously reported to be associated with skeletal muscle adaptation, performance, or recovery that were differentially upregulated in present study include, but are not limited to, Lincmd1 for young muscle and Nes, Timp1, Postn, and Ndrg4 for older muscle. Lincmd1, like H19, is a long-noncoding RNA found in skeletal muscle and associated with myoblast differentiation, muscle regeneration, and exercise training (67, 70, 71). Bonilauri and Dallagiovanna (67) reported that Lincmd1 gene expression increased 1.8-fold in skeletal muscle biopsies of young subjects after 12 wk of high-intensity interval training. Here, Lincmd1 expression was nearly sixfold higher after training in young muscle while unchanged in older muscle. In contrast to Lincmd1, training increased Nes, Timp1, Postn, and Ndrg4 genes differentially in older muscle. These genes are responsible for diverse molecular and cellular functions ranging from myogenic processes (e.g., nestin, Ndrg4) to remodeling of the extracellular matrix (e.g., Timp1, Postn) (72–75). It is interesting to note that many genes associated with myogenic differentiation were increased in both young and older muscles following eccentric training and that there was some overlap between age groups but also many differentially regulated genes. It has been suggested that gene expression differences that manifest during differentiation may underlie age-related reductions in the muscle’s regenerative capacity based on aged myogenic cells executing the differentiation program more slowly than young myogenic cells (76).

The GO enrichment analysis, which maps function to the regulated genes, also highlighted key differences in how young and older muscles responded to repeated bouts of eccentric contractions (Fig. 7). Trained young muscle upregulated several genes associated with transcription and regulation of the cell cycle. Genes within this enrichment included Erg1 and Fos, two genes associated with Atf3 (77). As mentioned previously, Atf3 was upregulated in both age groups, yet cell-cycle GO terms were only observed in trained young muscle indicating that downstream effectors of the Atf3 protein may have been dysregulated in older muscle. Additional changes specifically observed in older muscle following training were the upregulation of genes within the extracellular matrix and the downregulation of genes within the mitochondrial electron transport chain (Fig. 7). As reviewed by Mann et al. (78), remodeling of the extracellular matrix can result in fibrotic deposition in aged skeletal muscle due to aberrant repair and regeneration of damaged proteins and fibers. Although fibrosis was not measured in the present study, muscle quality was 27% lower in trained older muscle compared with trained young muscle, indicative of a significant reduction in muscle quality. The rationale for why genes of the mitochondrial electron transport chain decreased in older muscle is unclear; however, there is data to suggest that strenuous exercise in senescent muscle may induce mitochondrial damage (79). This damage could have theoretically decreased the expression of mitochondrial proteins, such as NADH dehydrogenase, and increased levels of oxidative stress. Skeletal muscle oxidative stress could have progressively developed during the eccentric contraction training regimen causing maladaptation in older muscle (80). Indeed, levels of hydrogen peroxide, presumably produced by the mitochondria (81), were found to be higher in aged rats after 4.5 wk of chronic loading (80 maximal contractions, 3 times/week) compared with trained young rats (80). Taken together, the striking differences observed in the GO enrichment analysis are indicative of distinct aging effects in skeletal muscle mediated by repeated bouts of eccentric contractions.

Another important component of the GO enrichment are terms enriched for genes commonly upregulated in young and older muscle, which included contractile fiber organization and assembly. Indeed, although older muscle did not get stronger or functionally adapt in the same manner as the young muscle, older muscle still exhibited some capacity to recover torque following the final bout (Fig. 3). Interestingly, keratin genes were associated with these GO terms and some of the most highly upregulated genes (via fold-change) after training in young and older muscle (Table 2 and Fig. 6). Keratins (Krt1–28) are intermediate filaments present in mammalian cells and form obligate noncovalent heteropolymers that contain equimolar amounts of type I (Krt9–28) and type II (Krt1–8). Keratins are primarily localized to filaments surrounding sarcomere Z-disks and at the Z-disk domains of costameres, but are also present at both the M-line and longitudinal domains of costameres (82–87). Specifically, keratin filaments are thought to interact with the myofibrillar apparatus and with the plasmalemma, in part, via their ability to bind dystrophin. Due to their location and structural roles, keratins likely contribute to cytoskeletal organization, force transduction, and sarcomere alignment (82–87). Interestingly, Krt18 and Krt8 were both highly upregulated after training and much more so in young versus older muscle (Table 2 and Fig. 6). The roles of keratins in skeletal muscle remodeling and plasticity are currently unknown; however, given the fold increases in their expression after training (that was also influenced by age), additional research into these specific intermediate filaments seems to be warranted.

It should be noted that in the present study, transcriptomics was only done after exercise training, specifically 7 days following the fifth and final bout of eccentric contractions. Therefore, we cannot make conclusions about what may have occurred at other time points or if the older muscle would have fully recovered (given more time). It is possible and likely that molecular changes differed between bouts and that the transcriptional changes that occurred acutely after bouts one or two may have been more impactful than after bout 5. That is, trained muscle had already adapted or maladapted by study completion. Another important caveat of only assessing one timepoint is that age may have influenced the temporal expression of genes; rather, transcriptional signatures may have occurred early or have been delayed in older muscle. Indeed, Rader and Baker (41) reported a muted expression of stress-responsive genes in aged rat muscle compared with young rat muscle following an isolated session of stretch-shortening contractions. It is notable that in the present study, recovery of isometric torque was not impaired in older muscle following a single bout of eccentric contraction (Figs. 3A and 4, bout 1; day 7). Valencia et al. (88) reported a similar finding in male mice, concluding that aged sarcopenic muscle exhibited a similar ability to recover contractile function as younger muscle following a single bout of eccentric contractions. Others have reported contrasting findings that a single bout of eccentric contractions in aged male and female mice results in prolonged and possibly permanent strength deficits (89, 90). Here, we demonstrate that eccentric contraction-induced weakness was only observed because older muscles were not able to adapt to repeated bouts of maximal eccentric exercise. It is likely any impairment of stress-responsive genes, proteins, modifications, etc. that was observed after a single session/bout of exercise would become exacerbated with continued exercise exposure and ultimately lead to weakness.

We do acknowledge study limitations, many that can be incorporated into future projects. Frist, because there were no age-matched control groups, particularly for the older mice that were not exposed to anesthesia or eccentric contractions, we cannot accurately tease out if weakness was solely due to the eccentric exercise protocol. Additional age-matched controls, including a group that was only tested at the study completion (i.e., single exposure to anesthesia) and a group that performed the same exercise protocol using concentric (vs. eccentric) contractions would help bolster the study design. These same improvements would be true for testing male mice, as we only tested female mice. Second, it is possible that the contralateral nonexercised (right) muscles may have been influenced by repeated eccentric contractions completed by the left muscles. Any changes that occurred in the contralateral muscles could either attenuate or exacerbate the effects observed in the exercised muscles, particularly as it pertains to gene expression. From this perspective, age-matched controls would also be beneficial to include when using a similar training design. Nonetheless, the present findings clearly demonstrate that aging influences gene expression responsivity after eccentric exercise training and provides a strong basis for upcoming studies.

In closing, the ability to adapt to exercise training is likely pivotal to preventing and combating sarcopenia and frailty. When adaptive potential is blunted or impaired, chronic skeletal muscle stress will consequently result in long lasting or permanent weakness. Here, we demonstrate that skeletal muscle of young and older female mice responds differently to maximal, eccentric exercise training. Young muscles got stronger whereas older muscles got weaker, implying some impairment in the repair and/or regenerative capacity of older mice. Interestingly, despite both age groups completing the same exercise regimen, numerous genes were uniquely regulated by training in young muscle versus older muscle and vice versa. These results highlight that muscle plasticity is not fixed across age and that with advancing age, the ability to handle or cope with physical stress may be impaired.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental material: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24049641.v1.

GRANTS

This work was supported by a Medical Research Council fellowship award (to C.S.D., MR/T026014/1), a Glenn Foundation for Medical Research and AFAR Grant for Junior Faculty award (to C.W.B., A23006), and National Institute of Health Grants (to D.A.L., R01AG031743 and to C.W.B., R03AG081950).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.W.B. conceived and designed research; C.W.B. and C.S.D. performed experiments; C.W.B., C.S.D., T.E., N.J.S., C.R.G.W., and D.A.L. analyzed data; C.W.B., C.S.D., T.E., N.J.S., C.R.G.W., and D.A.L. interpreted results of experiments; C.W.B. and C.S.D. prepared figures; C.W.B. and C.S.D. drafted manuscript; C.W.B., C.S.D., T.E., N.J.S., C.R.G.W., and D.A.L. edited and revised manuscript; C.W.B., C.S.D., T.E., N.J.S., C.R.G.W., and D.A.L. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Figure 1 and graphical abstract created with BioRender and published with permission.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kirk B, Zanker J, Bani Hassan E, Bird S, Brennan-Olsen S, Duque G. Sarcopenia Definitions and Outcomes Consortium (SDOC) criteria are strongly associated with malnutrition, depression, falls, and fractures in high-risk older persons. J Am Med Dir Assoc 22: 741–745, 2021. doi: 10.1016/J.JAMDA.2020.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Manini TM, Visser M, Won-Park S, Patel KV, Strotmeyer ES, Chen H, Goodpaster B, De Rekeneire N, Newman AB, Simonsick EM, Kritchevsky SB, Ryder K, Schwartz AV, Harris TB. Knee extension strength cutpoints for maintaining mobility. J Am Geriatr Soc 55: 451–457, 2007. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McGrath R, Erlandson KM, Vincent BM, Hackney KJ, Herrmann SD, Clark BC. Decreased handgrip strength is associated with impairments in each autonomous living task for aging adults in the United States. J Frailty Aging 8: 141–145, 2019. doi: 10.14283/jfa.2018.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Newman AB, Kupelian V, Visser M, Simonsick EM, Goodpaster BH, Kritchevsky SB, Tylavsky FA, Rubin SM, Harris TB. Strength, but not muscle mass, is associated with mortality in the health, aging and body composition study cohort. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 61: 72–77, 2006. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rantanen T. Muscle strength, disability and mortality. Scand J Med Sci Sports 13: 3–8, 2003. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0838.2003.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rantanen T, Guralnik JM, Foley D, Masaki K, Leveille S, Curb JD, White L. Midlife hand grip strength as a predictor of old age disability. J Am Med Assoc 281: 558–560, 1999. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.6.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rantanen T, Guralnik JM, Izmirlian G, Williamson JD, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Fried LP. Association of muscle strength with maximum walking speed in disabled older women. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 77: 299–305, 1998. doi: 10.1097/00002060-199807000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Visser M, Goodpaster BH, Kritchevsky SB, Newman AB, Nevitt M, Rubin SM, Simonsick EM, Harris TB. Muscle mass, muscle strength, and muscle fat infiltration as predictors of incident mobility limitations in well-functioning older persons. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 60: 324–333, 2005. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bhasin S, Travison TG, Manini TM, Patel S, Pencina KM, Fielding RA, Magaziner JM, Newman AB, Kiel DP, Cooper C, Guralnik JM, Cauley JA, Arai H, Clark BC, Landi F, Schaap LA, Pereira SL, Rooks D, Woo J, Woodhouse LJ, Binder E, Brown T, Shardell M, Xue QL, D’agostino RB, Orwig D, Gorsicki G, Correa-De-Araujo R, Cawthon PM. Sarcopenia definition: the Position Statements of the Sarcopenia Definition and Outcomes Consortium. J Am Geriatr Soc 68: 1410–1418, 2020. doi: 10.1111/JGS.16372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, Mcburnie MA; Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 56: M146–M156, 2001. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kalyani RR, Corriere M, Ferrucci L. Age-related and disease-related muscle loss: the effect of diabetes, obesity, and other diseases. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2: 819–829, 2014. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70034-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Syddall H, Cooper C, Martin F, Briggs R, Sayer AA. Is grip strength a useful single marker of frailty? Age Ageing 32: 650–656, 2003. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afg111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Xue QL, Walston JD, Fried LP, Beamer BA. Prediction of risk of falling, physical disability, and frailty by rate of decline in grip strength: the women’s health and aging study. Arch Intern Med 171: 1119–1121, 2011. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Borde R, Hortobágyi T, Granacher U. Dose-response relationships of resistance training in healthy old adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med 45: 1693–1720, 2015. doi: 10.1007/S40279-015-0385-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fiatarone MA, Marks EC, Ryan ND, Meredith CN, Lipsitz LA, Evans WJ. High-intensity strength training in nonagenarians: effects on skeletal muscle. JAMA 263: 3029–3034, 1990. doi: 10.1001/JAMA.1990.03440220053029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fiatarone MA, O'Neill EF, Ryan ND, Clements KM, Solares GR, Nelson ME, Roberts SB, Kehayias JJ, Lipsitz LA, Evans WJ. Exercise training and nutritional supplementation for physical frailty in very elderly people. N Engl J Med 330: 1769–1775, 1994. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406233302501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gluchowski A, Harris N, Dulson D, Cronin J. Chronic eccentric exercise and the older adult. Sports Med 45: 1413–1430, 2015. doi: 10.1007/S40279-015-0373-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Peterson MD, Rhea MR, Sen A, Gordon PM. Resistance exercise for muscular strength in older adults: a meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev 9: 226–237, 2010. doi: 10.1016/J.ARR.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Isner-Horobeti ME, Dufour SP, Vautravers P, Geny B, Coudeyre E, Richard R. Eccentric exercise training: modalities, applications and perspectives. Sports Med 43: 483–512, 2013. doi: 10.1007/S40279-013-0052-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vogt M, Hoppeler HH. Eccentric exercise: mechanisms and effects when used as training regime or training adjunct. J Appl Physiol (1985) 116: 1446–1454, 2014. doi: 10.1152/JAPPLPHYSIOL.00146.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gault ML, Willems MET. Aging, functional capacity and eccentric exercise training. Aging Dis 4: 351–363, 2013. doi: 10.14336/AD.2013.0400351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kim DY, Oh SL, Lim JY. Applications of eccentric exercise to improve muscle and mobility function in older adults. Ann Geriatr Med Res 26: 4–15, 2022. doi: 10.4235/AGMR.21.0138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lim JY. Therapeutic potential of eccentric exercises for age-related muscle atrophy. Integr Med Res 5: 176–181, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Harper SA, Thompson BJ. Potential benefits of a minimal dose eccentric resistance training paradigm to combat sarcopenia and age-related muscle and physical function deficits in older adults. Front Physiol 12: 790034, 2021. doi: 10.3389/FPHYS.2021.790034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Roig M, O'Brien K, Kirk G, Murray R, McKinnon P, Shadgan B, Reid WD. The effects of eccentric versus concentric resistance training on muscle strength and mass in healthy adults: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 43: 556–568, 2009. doi: 10.1136/BJSM.2008.051417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cleak MJ, Eston RG. Muscle soreness, swelling, stiffness and strength loss after intense eccentric exercise. Br J Sports Med 26: 267–272, 1992. doi: 10.1136/BJSM.26.4.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lindsay A, Abbott G, Ingalls CP, Baumann CW. Muscle strength does not adapt from a second to third bout of eccentric contractions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the repeated bout effect. J Strength Cond Res 35: 576–584, 2020. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000003924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Newham DJ, Jones DA, Clarkson PM. Repeated high-force eccentric exercise: effects on muscle pain and damage. J Appl Physiol (1985) 63: 1381–1386, 1987. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.63.4.1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Smith LL, Fulmer MG, Holbert D, McCammon MR, Houmard JA, Frazer DD, Nsien E, Israel RG. The impact of a repeated bout of eccentric exercise on muscular strength, muscle soreness and creatine kinase. Br J Sports Med 28: 267–271, 1994. doi: 10.1136/BJSM.28.4.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Warren GL, Call JA, Farthing AK, Baadom-Piaro B. Minimal evidence for a secondary loss of strength after an acute muscle injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med 47: 41–59, 2017. doi: 10.1007/S40279-016-0528-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chen TC, Chen HL, Lin MJ, Wu CJ, Nosaka K. Muscle damage responses of the elbow flexors to four maximal eccentric exercise bouts performed every 4 weeks. Eur J Appl Physiol 106: 267–275, 2009. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Clarkson PM, Tremblay I. Exercise-induced muscle damage, repair, and adaptation in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 65: 1–6, 1988. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.65.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ebbeling CB, Clarkson PM. Muscle adaptation prior to recovery following eccentric exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 60: 26–31, 1990. doi: 10.1007/BF00572181/METRICS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Newton MJ, Morgan GT, Sacco P, Chapman DW, Nosaka K. Comparison of responses to strenuous eccentric exercise of the elbow flexors between resistance-trained and untrained men. J strength Cond Res 22: 597–607, 2008. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0B013E3181660003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nosaka K, Sakamoto K, Newton M, Sacco P. How long does the protective effect on eccentric exercise-induced muscle damage last? Med Sci Sports Exerc 33: 1490–1495, 2001. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200109000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brooks SV, Opiteck JA, Faulkner JA. Conditioning of skeletal muscles in adult and old mice for protection from contraction-induced injury. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 56: B163–B171, 2001. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.4.b163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Brown AM, Ganjayi MS, Baumann CW. RAD140 (Testolone) negatively impacts skeletal muscle adaptation, frailty status and mortality risk in female mice. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2023. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.13824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cutlip RG, Baker BA, Geronilla KB, Mercer RR, Kashon ML, Miller GR, Murlasits Z, Alway SE. Chronic exposure to stretch-shortening contractions results in skeletal muscle adaptation in young rats and maladaptation in old rats. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 31: 573–587, 2006. doi: 10.1139/H06-033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Greig CA, Gray C, Rankin D, Young A, Mann V, Noble B, Atherton PJ. Blunting of adaptive responses to resistance exercise training in women over 75y. Exp Gerontol 46: 884–890, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Naimo MA, Rader EP, Ensey J, Kashon ML, Baker BA. Reduced frequency of resistance-type exercise training promotes adaptation of the aged skeletal muscle microenvironment. J Appl Physiol (1985) 126: 1074–1087, 2019. doi: 10.1152/JAPPLPHYSIOL.00582.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rader EP, Baker BA. Age-dependent stress response DNA demethylation and gene upregulation accompany nuclear and skeletal muscle remodeling following acute resistance-type exercise in rats. Facets (Ott) 5: 455–473, 2020. doi: 10.1139/FACETS-2019-0060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rader EP, Layner K, Triscuit AM, Chetlin RD, Ensey J, Baker BA. Age-dependent muscle adaptation after chronic stretch-shortening contractions in rats. Aging Dis 7: 1–13, 2016. doi: 10.14336/AD.2015.0920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Slivka D, Raue U, Hollon C, Minchev K, Trappe S. Single muscle fiber adaptations to resistance training in old (>80 yr) men: evidence for limited skeletal muscle plasticity. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295: R273–R280, 2008. doi: 10.1152/AJPREGU.00093.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Stewart VH, Saunders DH, Greig CA. Responsiveness of muscle size and strength to physical training in very elderly people: a systematic review. Scand J Med Sci Sports 24: e1–e10, 2014. doi: 10.1111/SMS.12123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Clark LA, Russ DW, Tavoian D, Arnold WD, Law TD, France CR, Clark BC. Heterogeneity of the strength response to progressive resistance exercise training in older adults: contributions of muscle contractility. Exp Gerontol 152: 111437, 2021. doi: 10.1016/J.EXGER.2021.111437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Justice JN, Cesari M, Seals DR, Shively CA, Carter CS. Comparative approaches to understanding the relation between aging and physical function. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 71: 1243–1253, 2016. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glv035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sidky SR, Ingalls CP, Lowe DA, Baumann CW. Membrane proteins increase with the repeated bout effect. Med Sci Sports Exerc 54: 57–66, 2022. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Baumann CW, Otis JS. 17-(allylamino)-17-demethoxygeldanamycin drives Hsp70 expression but fails to improve morphological or functional recovery in injured skeletal muscle. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 42: 1308–1316, 2015. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lowe DA, Warren GL, Ingalls CP, Boorstein DB, Armstrong RB. Muscle function and protein metabolism after initiation of eccentric contraction-induced injury. J Appl Physiol (1985) 79: 1260–1270, 1995. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.4.1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Baumann CW, Rogers RG, Otis JS. Utility of 17-(allylamino)-17-demethoxygeldanamycin treatment for skeletal muscle injury. Cell Stress Chaperones 21: 1111–1117, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s12192-016-0717-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kim D, Paggi JM, Park C, Bennett C, Salzberg SL. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat Biotechnol 37: 907–915, 2019. doi: 10.1038/S41587-019-0201-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30: 923–930, 2014. doi: 10.1093/BIOINFORMATICS/BTT656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15: 550, 2014. doi: 10.1186/S13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y, He QY. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS 16: 284–287, 2012. doi: 10.1089/OMI.2011.0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Willis CRG, Deane CS, Ames RM, Bass JJ, Wilkinson DJ, Smith K, Phillips BE, Szewczyk NJ, Atherton PJ, Etheridge T. Transcriptomic adaptation during skeletal muscle habituation to eccentric or concentric exercise training. Sci Rep 11: 23930, 2021. doi: 10.1038/S41598-021-03393-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Baumann CW, Kwak D, Thompson LV. Phenotypic frailty assessment in mice: development, discoveries, and experimental considerations. Physiology (Bethesda) 35: 405–414, 2020. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00016.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Baumann CW, Kwak D, Thompson LV. Assessing onset, prevalence and survival in mice using a frailty phenotype. Aging (Albany NY) 10: 4042–4053, 2018. doi: 10.18632/aging.101692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kwak D, Baumann CW, Thompson LV. Identifying characteristics of frailty in female mice using a phenotype assessment tool. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 75: 640–646, 2020. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glz092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lu D, Chen J, Hai T. The regulation of ATF3 gene expression by mitogen-activated protein kinases. Biochem J 401: 559–567, 2007. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Barash IA, Mathew L, Ryan AF, Chen J, Lieber RL. Rapid muscle-specific gene expression changes after a single bout of eccentric contractions in the mouse. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 286: C355–C364, 2004. doi: 10.1152/AJPCELL.00211.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Chen YW, Hubal MJ, Hoffman EP, Thompson PD, Clarkson PM. Molecular responses of human muscle to eccentric exercise. J Appl Physiol (1985) 95: 2485–2494, 2003. doi: 10.1152/JAPPLPHYSIOL.01161.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Fernández-Verdejo R, Vanwynsberghe AM, Essaghir A, Demoulin JB, Hai T, Deldicque L, Francaux M. Activating transcription factor 3 attenuates chemokine and cytokine expression in mouse skeletal muscle after exercise and facilitates molecular adaptation to endurance training. FASEB J 31: 840–851, 2017. doi: 10.1096/FJ.201600987R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. MacNeil LG, Melov S, Hubbard AE, Baker SK, Tarnopolsky MA. Eccentric exercise activates novel transcriptional regulation of hypertrophic signaling pathways not affected by hormone changes. PLoS One 5: e10695, 2010. doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0010695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Mckenzie MJ, Goldfarb AH. Aerobic exercise bout effects on gene transcription in the rat soleus. Med Sci Sports Exerc 39: 1515–1521, 2007. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0B013E318074C256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Mckenzie MJ, Goldfarb AH, Kump DS. Gene response of the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles to an acute aerobic run in rats. J Sports Sci Med 10: 385–392, 2011. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000353510.09224.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Pillon NJ, Gabriel BM, Dollet L, Smith JAB, Sardón Puig L, Botella J, Bishop DJ, Krook A, Zierath JR. Transcriptomic profiling of skeletal muscle adaptations to exercise and inactivity. Nat Commun 11: 470, 2020. doi: 10.1038/S41467-019-13869-W. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Bonilauri B, Dallagiovanna B. Long non-coding RNAs are differentially expressed after different exercise training programs. Front Physiol 11: 567614, 2020. doi: 10.3389/FPHYS.2020.567614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Dey BK, Pfeifer K, Dutta A. The H19 long noncoding RNA gives rise to microRNAs miR-675-3p and miR-675-5p to promote skeletal muscle differentiation and regeneration. Genes Dev 28: 491–501, 2014. doi: 10.1101/GAD.234419.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Li Y, Zhang Y, Hu Q, Egranov SD, Xing Z, Zhang Z, Liang K, Ye Y, Pan Y, Chatterjee SS, Mistretta B, Nguyen TK, Hawke DH, Gunaratne PH, Hung MC, Han L, Yang L, Lin C. Functional significance of gain-of-function H19 lncRNA in skeletal muscle differentiation and anti-obesity effects. Genome Med 13: 137, 2021. doi: 10.1186/S13073-021-00937-4/FIGURES/7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Cesana M, Cacchiarelli D, Legnini I, Santini T, Sthandier O, Chinappi M, Tramontano A, Bozzoni I. A long noncoding RNA controls muscle differentiation by functioning as a competing endogenous RNA. Cell 147: 358–369, 2011. [Erratum in Cell 147: 947, 2011]. doi: 10.1016/J.CELL.2011.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Legnini I, Morlando M, Mangiavacchi A, Fatica A, Bozzoni I. A feedforward regulatory loop between HuR and the long noncoding RNA linc-MD1 controls early phases of myogenesis. Mol Cell 53: 506–514, 2014. doi: 10.1016/J.MOLCEL.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ito N, Miyagoe-Suzuki Y, Takeda S, Kudo A. Periostin is required for the maintenance of muscle fibers during muscle regeneration. Int J Mol Sci 22: 3627, 2021. doi: 10.3390/IJMS22073627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Lindqvist J, Torvaldson E, Gullmets J, Karvonen H, Nagy A, Taimen P, Eriksson JE. Nestin contributes to skeletal muscle homeostasis and regeneration. J Cell Sci 130: 2833–2842, 2017. doi: 10.1242/JCS.202226/VIDEO-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Mackey AL, Donnelly AE, Turpeenniemi-Hujanen T, Roper HP. Skeletal muscle collagen content in humans after high-force eccentric contractions. J Appl Physiol (1985) 97: 197–203, 2004. doi: 10.1152/JAPPLPHYSIOL.01174.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Zhu M, Zheng R, Guo Y, Zhang Y, Zuo B. NDRG4 promotes myogenesis via Akt/CREB activation. Oncotarget 8: 101720–101734, 2017. doi: 10.18632/ONCOTARGET.21591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kimmel JC, Yi N, Roy M, Hendrickson DG, Kelley DR. Differentiation reveals latent features of aging and an energy barrier in murine myogenesis. Cell Rep 35: 109046, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Ishikawa H, Shozu M, Okada M, Inukai M, Zhang B, Kato K, Kasai T, Inoue M. Early growth response gene-1 plays a pivotal role in down-regulation of a cohort of genes in uterine leiomyoma. J Mol Endocrinol 39: 333–341, 2007. doi: 10.1677/JME-06-0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Mann CJ, Perdiguero E, Kharraz Y, Aguilar S, Pessina P, Serrano AL, Muñoz-Cánoves P. Aberrant repair and fibrosis development in skeletal muscle. Skelet Muscle 1: 21, 2011. doi: 10.1186/2044-5040-1-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Lee S, Kim M, Lim W, Kim T, Kang C. Strenuous exercise induces mitochondrial damage in skeletal muscle of old mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 461: 354–360, 2015. doi: 10.1016/J.BBRC.2015.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Ryan MJ, Dudash HJ, Docherty M, Geronilla KB, Baker BA, Haff GG, Cutlip RG, Alway SE. Vitamin E and C supplementation reduces oxidative stress, improves antioxidant enzymes and positive muscle work in chronically loaded muscles of aged rats. Exp Gerontol 45: 882–895, 2010. doi: 10.1016/J.EXGER.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Boveris A, Cadenas E. Mitochondrial production of hydrogen peroxide regulation by nitric oxide and the role of ubisemiquinone. IUBMB Life 50: 245–250, 2000. doi: 10.1080/713803732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Lovering RM, O'Neill A, Muriel JM, Prosser BL, Strong J, Bloch RJ. Physiology, structure, and susceptibility to injury of skeletal muscle in mice lacking keratin 19-based and desmin-based intermediate filaments. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 300: C803–C813, 2011. doi: 10.1152/AJPCELL.00394.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Muriel JM, O'Neill A, Kerr JP, Kleinhans-Welte E, Lovering RM, Bloch RJ. Keratin 18 is an integral part of the intermediate filament network in murine skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 318: C215–C224, 2020. doi: 10.1152/AJPCELL.00279.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. O'Neill A, Williams MW, Resneck WG, Milner DJ, Capetanaki Y, Bloch RJ. Sarcolemmal organization in skeletal muscle lacking desmin: evidence for cytokeratins associated with the membrane skeleton at costameres. Mol Biol Cell 13: 2347–2359, 2002. doi: 10.1091/MBC.01-12-0576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Stone MR, O'Neill A, Catino D, Bloch RJ. Specific interaction of the actin-binding domain of dystrophin with intermediate filaments containing keratin 19. Mol Biol Cell 16: 4280–4293, 2005. doi: 10.1091/MBC.E05-02-0112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Stone MR, O'Neill A, Lovering RM, Strong J, Resneck WG, Reed PW, Toivola DM, Ursitti JA, Omary MB, Bloch RJ. Absence of keratin 19 in mice causes skeletal myopathy with mitochondrial and sarcolemmal reorganization. J Cell Sci 120: 3999–4008, 2007. doi: 10.1242/JCS.009241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Ursitti JA, Lee PC, Resneck WG, McNally MM, Bowman AL, O'Neill A, Stone MR, Bloch RJ. Cloning and characterization of cytokeratins 8 and 19 in adult rat striated muscle. Interaction with the dystrophin glycoprotein complex. J Biol Chem 279: 41830–41838, 2004. doi: 10.1074/JBC.M400128200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Valencia AP, Samuelson AT, Stuppard R, Marcinek DJ. Functional recovery from eccentric injury is maintained in sarcopenic mouse muscle. JCSM Rapid Commun 4: 222–231, 2021. doi: 10.1002/RCO2.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Rader EP, Faulkner JA. Effect of aging on the recovery following contraction-induced injury in muscles of female mice. J Appl Physiol (1985) 101: 887–892, 2006. doi: 10.1152/JAPPLPHYSIOL.00380.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Rader EP, Faulkner JA. Recovery from contraction-induced injury is impaired in weight-bearing muscles of old male mice. J Appl Physiol (1985) 100: 656–661, 2006. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00663.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24049641.v1.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.