Summary

There is an unmet clinical need for a non-invasive and cost-effective test for oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) that informs clinicians when a biopsy is warranted. Human beta-defensin 3 (hBD-3), an epithelial cell-derived anti-microbial peptide, is pro-tumorigenic and overexpressed in early-stage OSCC compared to hBD-2. We validate this expression dichotomy in carcinoma in situ and OSCC lesions using immunofluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry. The proportion of hBD-3/hBD-2 levels in non-invasively collected lesional cells compared to contralateral normal cells, obtained by ELISA, generates the beta-defensin index (BDI). Proof-of-principle and blinded discovery studies demonstrate that BDI discriminates OSCC from benign lesions. A multi-center validation study shows sensitivity and specificity values of 98.2% (95% confidence interval [CI] 90.3–99.9) and 82.6% (95% CI 68.6–92.2), respectively. A proof-of-principle study shows that BDI is adaptable to a point-of-care assay using microfluidics. We propose that BDI may fulfill a major unmet need in low-socioeconomic countries where pathology services are lacking.

Keywords: hBD-3, hBD-2, OSCC, biomarker

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

The beta-defensin index (BDI) non-invasively distinguishes OSCC from benign lesions

-

•

BDI calculates hBD3 (over)expression/hBD2 (under)expression to detect CIS and OSCC

-

•

A multi-center validation study yields sensitivity and specificity of 98% and 83%

-

•

The BDI may be adapted to a point-of-care assay using intact cell microfluidics

Ghosh et al. present a non-invasive ELISA-based beta-defensin index (BDI) detection platform for oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC). Blinded discovery and validation studies demonstrate that BDI can discriminate OSCC from benign lesions. A proof-of-principle study shows promise in transforming BDI into a microfluidic intact cell assay for future point-of-care application.

Introduction

Head and neck squamous cell cancer (HNSC) is the seventh most prevalent malignancy in the world, and developing countries are witnessing a rise in its incidence.1,2 HNSC makes up approximately 5% of all cancers worldwide3 and 3% of all malignancies in the United States.4 There are approximately 640,000 cases of HNSC per year, resulting in about 350,000 deaths worldwide.5 In the United States, ∼65,000 new cases were estimated to have been diagnosed in 2020.6 Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is the most frequent (approximately 90%) malignant tumor of HNSC.7 It arises from the mucosal surfaces of the oral cavity7 and is often associated with excessive tobacco, alcohol, and/or betel-nut usage, resulting in mutations of key p53 tumor-suppressor genes, primarily p53.8,9,10 The accurate diagnosis of early malignant or premalignant OSCC lesions remains challenging, as we currently rely on histology with inherent variability in inter-rater reliability.11,12,13,14 Moreover, biopsies are costly, invasive, and may lead to increased complications. Biopsies are also not feasible if repeated screenings of the same lesion are required. Therefore, there is an unmet clinical need for a rapid, objective, non-invasive, low-cost way of detecting oral cancer that can also serially monitor pre-cancerous lesions.

Over time (average 4.5–8.1 years), approximately 17% of patients initially diagnosed with leukoplakia, through biopsy, as benign/mild dysplasia, will go on to develop OSCC.15,16 Stratifying patient risk based on histology is challenging, and a reliable non-invasive test that identifies which patients will progress to severe dysplasia or early invasive OSCC does not currently exist. A biomarker that identifies progressive or transforming lesions would allow for early detection. Early identification would improve clinical outcomes and negate the need for unnecessary biopsies in patients whose lesions remain benign or have not yet begun to transform. OSCC is an aggressive cancer with a mortality rate of approximately 50% for all stages combined. However, stage 1 disease has a 5-year survival rate of approximately 92% and is frequently cured with surgery alone. This illustrates the importance of early diagnosis and treatment and highlights the positive impact a biomarker that aids in diagnosing early malignant lesions would have on the outcome and care of OSCC patients.17

Human beta-defensin 3 (hBD-3), a potent anti-microbial peptide (AMP) of the innate immune system,18,19 is normally expressed in highly proliferating epithelial cells of the stratum basale of the oral mucosa. It plays a role in normal wound healing and is induced through activation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), a process amplified in OSCC.20,21,22 However, in the context of dysplasia and OSCC, we and others have shown that hBD-3 exhibits pro-tumorigenic properties; it is induced through EGF/EGFR signaling,23 is inhibited by the tumor suppressor p53,24 and is associated with nuclear translocation of β-catenin in vivo23. HBD-3 selectively chemoattracts and activates tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) but not CD3+ T cells in vivo.25 The TAMs produce pro-inflammatory cytokines and growth factors that facilitate tumor development and progression.26 The murine ortholog of hBD-3, mBD-14, induces regulatory T cell (Treg) conversion,27 while hBD-3 promotes PDL-1 expression on tumor cells.28 These data collectively suggest that hBD-3 plays an important role in tumorigenesis associated with primary OSCC.

Our initial study showing that overexpressed hBD-3 and underexpressed hBD-2 accompany the carcinoma in situ (CIS) phenotype25 prompted us to conduct a human observational study to determine whether the ratio of hBD-3/hBD-2 correlated with the diagnosis of OSCC. Subjects presenting with suspicious oral lesions had their lesion and contralateral normal site non-invasively sampled via cytobrush to determine their beta-defensin index (BDI). We hypothesized that the value of the BDI ratio could discriminate cancerous from non-cancerous tissue in suspicious oral lesions.

In the present study, we (1) analyzed The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database to understand and annotate the expression of hBD-3 transcript (DEFB103) in the context of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), (2) validated the expression of hBD-3 and hBD-2 in retrospectively collected CIS and OSCC tissue using immunofluorescence microscopy, (3) demonstrated differential hBD-3 and hBD-2 expression in cell populations from excised OSCC tumors by fluorescent-activated cell sorting (FACS), (4) showed by FACS that cytobrush-collected cells from OSCC lesions have similar defensin expression profiles as cells excised by biopsy from OSCC tumor tissue, (5) designed an ELISA-based BDI assay platform to discriminate OSCC from benign lesions, (6) validated the BDI platform through multi-center clinical studies of three non-overlapping cohorts of subjects and (7) showed that BDI, in a microfluidic intact cell assay (MICA) system, could eventually replace the conventional ELISA-based BDI platform.

Results

Expression of DEFB103 and DEFB4 transcripts in head and neck cancer based on The Cancer Genome Atlas

Because hBD-3 and hBD-2 peptides and transcripts (DEFB103 and DEFB4, respectively) are differentially expressed in multiple cancer types (reviewed in Ghosh et al.29), we mined the TCGA database for DEFB103 and DEFB4 transcript expression levels in HNSCC. Using the online Gene Expression Display Server (GEDS),30 we found that both transcripts were highest in HNSC when compared to other cancer types (Figures 1A and 1B). Using the UALCAN portal,31 we discovered that DEFB103, but not DEFB4, was significantly upregulated in HNSC tumor tissue when compared to normal tissue (p = 0.048 vs. p = 0.56) (Figures S1A and S1B). We further analyzed the HNSC--TCGA data using GEPIA232 for differential expression of DEFB103 with respect to different molecular subtypes of HNSC (as defined by Walter et al.33) and found that expression of DEFB103 was significantly higher in the “basal” subtype when compared to the other subtypes (i.e., mesenchymal, atypical, and classical) (Figure S1C). The basal subtype of HNSC is characterized by genes associated with (1) epidermal development, (2) ErbB signaling (ErbB; a family of four receptor tyrosine kinases, of which EGFR is the first discovered member),34 and (3) growth/transcription factor signaling.33 With respect to HNSC tumor grade, the data revealed that DEFB103 expression was highest in grade 1, i.e., the “well-differentiated” HNSC subtype, compared to the other HNSC subtypes (Figure S1D), and its expression was also significantly higher in well-differentiated grade 1 HNSC compared to normal/healthy sites (Figure S1D). We further analyzed DEFB103 expression based on other clinicopathological characteristics, such as cancer stage, gender, age, and race (Figures S2A–S2D). As shown in Figure S2A, DEFB103 expression is significantly higher in stage 1 and stage 3 cancers compared to normal. In regard to gender, both male and female DEFB103 are significantly higher in HNSC compared to normal (Figure S2B). Age and race have no effect on the expression of DEFB103 (Figures S2C and S2D)

Figure 1.

TCGA data analysis, immunofluorescence microscopy, and flow cytometry of DEFB103/hBD-3 and DEFB4/hBD-2

(A and B) Expression of DEFB103 (A) and DEFB4 (B) across all TCGA cancer types (tumor [red] and normal [blue]).

(C) Immunofluorescence microscopic data for the expression of hBD-2 and -3 in 54 subjects (24 non-cancerous, 27 CIS, and 3 OSCC). Data presented as mean immunofluorescence intensity (IMF) ± SD. p value was calculated by non-parametric Mann-Whitney test.

(D) Representative immunofluorescence images of normal, CIS, and OSCC samples. hBD-3, green; hBD-2, red; DAPI, blue.

(E) Representative flow-cytometric data showing hBD-3- and hBD-2-expressing cells in respective OSCC tumors excised from three additional patients.

Using linked omics,35 we identified 38 genes that were strongly correlated with DEFB103 (Spearman’s rho ≥0.70) (Figures S2E and S2F). Two late cornified envelope proteins 3D (LCE3D) and LCE3E, belonging to the epidermal differentiation complex (EDC), were strongly associated with DEFB103 (Figure S2F). However, while both were higher in HNSC compared to normal, only LCE3D was significantly higher (Figure S2G). Interestingly, most of these genes belong to the EDC, comprising over 50 genes encoding proteins involved in the terminal differentiation and cornification of keratinocytes, the primary cell type of the epidermis36 (Figure S2H).

Overexpression of hBD-3 in CIS and oral cancer

Overexpression of hBD-3 and reduced expression of hBD-2 in OSCC compared to normal oral tissue was first noted by Wenghoefer et al.,37 who reported these differences at the mRNA level. Kesting et al.38 followed up with a more extensive study using qPCR and immunofluorescence microscopy in 45 paired OSCC and normal tissue samples. Overexpression of hBD-3 and underexpression of hBD-2 was further confirmed by us in a small cohort of seven oral CIS cases, compared to the healthy oral epithelium (n = 4), using immunofluorescence (IMF).25 To expand the CIS cohort and further confirm results in our OSCC cohort, we conducted an IMF study of 54 lesions (24 non-cancerous, 27 CIS, and 3 OSCC) and observed a similar phenotype in the additional CIS and cancerous lesions but not in non-cancerous lesions (Figures 1C and 1D). Thus, overexpression of hBD-3, with diminished expression of hBD-2, is a “reproducible phenotype” in CIS biopsies that is apparently maintained in OSCC. Furthermore, we performed flow-cytometry analysis of digested biopsy samples from three additional representative OSCC biopsy tissues to show that in all three cases, the percentage of hBD-3-positive cells was higher than that of hBD-2 (Figure 1E). In summary, transcript, protein, and now flow cytometry from three independent studies confirm the overexpression of hBD-3 and reduced expression of hBD-2 in CIS and OSCC lesions.

Based on our more extensive IMF findings and corroboratory FACS analysis supporting the differential expression of hBD-3 vs. hBD-2 in oral CIS and in OSCC lesions, respectively, we hypothesized that by collecting epithelial cells from a suspicious lesion and comparing its hBD-3/hBD-2 ratio to that of cells collected from the same subject’s contralateral healthy oral mucosa, a reliable biomarker for OSCC could be established.

Non-invasively collected (cytobrushed) mucosal cells can be used to collect cancer cells and to assay for the expression of human beta-defensins

To confirm that our cytobrush technique collected cancerous cells, our board-certified pathologist conducted cytological analysis of cytobrush samples (Figures 2A and 2B). We identified cancerous cells in the lesional site (Figure 2A) but not in the contralateral site (Figure 2B) of the same patient. Whole-exome sequencing (xE whole exome; Tempus, Chicago, IL) also confirmed the collection of cancer cells in the cytobrush samples but not in the contralateral site. Copy-number gains of CCND1, FGF3, FGF4, and FGF19, along with TP53 mutation (p.R156G), all associated with OSCC,39,40,41,42 were found exclusively in oral cancerous lesions.

Figure 2.

Cytological and flow-cytometric analysis of non-invasively collected cytobrushed cells

(A and B) Cytological images of epithelial cells obtained by cytobrushing of cancerous (A) and contralateral (B) sites of the same patient. The cancer cells in (A) (outlined in red) are present as three-dimensional clusters with marked variation in nuclear size and shape (blue arrows), single cells and small clusters with abnormal cytoplasmic shapes (green arrows), and nuclear enlargement and multi-nucleation in occasional cells (black arrows). In contrast, the epithelial cells obtained from the contralateral site (B) have features of normal superficial squamous cells, including single cells and cell clusters in flat sheets with small, uniform nuclei. Scale bars, 20 μm.

(C) Representative flow-cytometric data showing hBD-3- and hBD-2-expressing cells among E-cadherin+ epithelial cell population in non-invasively collected cytobrushed cells from cheek and tongue of a healthy subject.

(D) Expression levels, as MFI of hBD-3 and hBD-2 in cytobrush samples collected from lesional and contralateral normal sites of OSCC patients (n = 4). p value was calculated by non-parametric Mann-Whitney test.

(E) Representative FACS data of one of the OSCC patients from (D) (pink: cells collected from lesional site; green: cells collected from contralateral site; maroon: cells isolated from excised tumor of the same patient).

(F) The ratio of hBD-3 and hBD-2 in contralateral and lesional cytobrush samples (n = 4). p value was calculated by non-parametric Mann-Whitney test.

We collected cytobrush samples from two healthy participants’ cheeks and tongues and, upon FACS analysis, discovered that ∼40% of E-cadherin-positive epithelial cells are positive for defensin peptides (Figure 2C; representative data from one participant), indicating that both peptides are detectable in non-invasively collected healthy mucosal samples. Interpersonal variability of the percentage of cytobrushed cells expressing hBD-2 vs. hBD-3 in healthy cheek and tongue was observed between subjects. Next, we collected cytobrush samples (see STAR Methods) from the tumor and contralateral normal sites of OSCC subjects (n = 4), respectively, before biopsy sampling. FACS analysis of each paired sample showed that there were significantly higher levels of hBD-3 (but not hBD-2) from OSCC vs. cells from respective contralateral sites obtained by cytobrush (Figures 2D and 2E). Additionally, the difference in the ratio of hBD-3 to hBD-2 in the OSCC site when compared to the ratio of hBD-3 to hBD-2 in the normal contralateral site was highly significant (p = 0.013, Figure 2F) compared to the expression of lesional hBD-3 itself in tumor vs. contralateral hBD-3 (p = 0.03, Figure 2D). These observations provided us with the rationale to test an hBD-3/hBD-2 ratio-based OSCC biomarker using non-invasively obtained cytobrush cell samples.

We coined the term “beta-defensin index” (BDI) and defined it as the ratio of hBD-3/hBD-2 in the lesional site over the ratio of hBD-3/hBD-2 in the contralateral site of the same patient (Figure 3A). We hypothesized that the BDI should be higher in subjects with an oral cancerous lesion compared to a BDI from subjects with a benign lesion.

Figure 3.

Beta-defensin index study design

(A) Cartoon presentation and formula for the beta-defensin index (BDI).

(B) Proof of concept for the BDI. Cytobrush samples were collected from four OSCC and four non-cancerous lesions. Diagnosis was determined by biopsy followed by pathology review. BDI values, as determined in (A), were calculated following ELISA. Official diagnoses for all eight lesions are presented in Table S1A. p value was calculated by non-parametric Mann-Whitney test.

(C) Flow diagram of ELISA-based BDI biomarker for proof-of-concept, discovery, and validation studies. Pie chart shows the percentage of non-cancerous/benign lesions (green) and cancerous lesions (orange) for each cohort. UC, University of Cincinnati; CWRU, Case Western Reserve University; WVU, West Virginia University.

Because FACS is costly, time consuming, requires expensive equipment and expertise to run, and demands analyzing intact cells, it is not a practical platform to efficiently assess the relevance and efficacy of BDI as a biomarker for CIS and early-stage OSCC in a clinical setting. Instead, we developed a BDI ELISA-based assay (see STAR Methods) and tested it on a separate cohort of clinical samples.

Beta-defensin index: Proof-of-concept, discovery, and validation studies

Proof-of-concept study

For an initial proof-of-principle analysis, we identified four patients with OSCC lesions and four with benign oral lesions (detailed diagnoses of all the participants are shown in Table S1A). The median value of the BDI (calculated as defined in Figure 3A) of the four cancerous lesions was significantly higher (p =0.02) than that of the four benign lesions (Figure 3B); i.e., supporting our initial proof of concept.

We previously reported that human papilloma virus genotype 16 (HPV16) promotes the expression of hBD-3 and that oropharyngeal cancer (OPC) lesions demonstrate its overexpression.24 Here we tested whether BDI is higher in HPV16-induced OPC. We collected cytobrush samples from tonsillar lesions, determined their BDI scores, and found that the median BDI for the HPV16-induced OPC lesions is significantly higher (p < 0.03) than that of benign tissue (Figure S3A), supporting our original finding and our proof of concept.

Before proceeding with BDI-based assays using mucosal epithelial cells, we wanted to discover whether hBD-2, hBD-3, and/or the hBD-3/hBD-2 ratio are significantly different in saliva samples from OSCC vs. non-OSCC cohorts. We determined the salivary levels of both defensins in a pilot cohort of subjects (n = 30; cancerous = 18, non-cancerous = 12) and found that neither hBD-2, hBD-3, nor the ratio of hBD-3 to hBD-2 were significantly different between the groups (Figure S3B), suggesting that BDI scoring from mucosal epithelial cells, but not from saliva, could be useful in distinguishing OSCC from benign lesions.

To determine the efficacy of the BDI platform, we tested it in four non-overlapping patient-based studies. The study design consisted of four investigator-blinded studies using a discovery-phase cohort, followed by a validation phase of three cohorts (summarized in Figure 3C). We recruited a total of 92 subjects for the discovery and validation study (18 years of age or older) undergoing clinical evaluation for OSCC due to the presence of suspicious red or white oral lesions present for 2 weeks or longer in the same location that had not been previously biopsied (see Table S2 for inclusion and exclusion criteria). While we initially included OPC lesions in the proof-of-concept phase and found that the BDI could differentiate OPC-related OSCC from non-OSCC lesions (Figure S3A), we decided to exclude OPC lesions from discovery and validation, as cytobrushing the oropharyngeal region is challenging without sedation, and our goal was to discover and validate the BDI using a non-invasive protocol that did not require sedation.

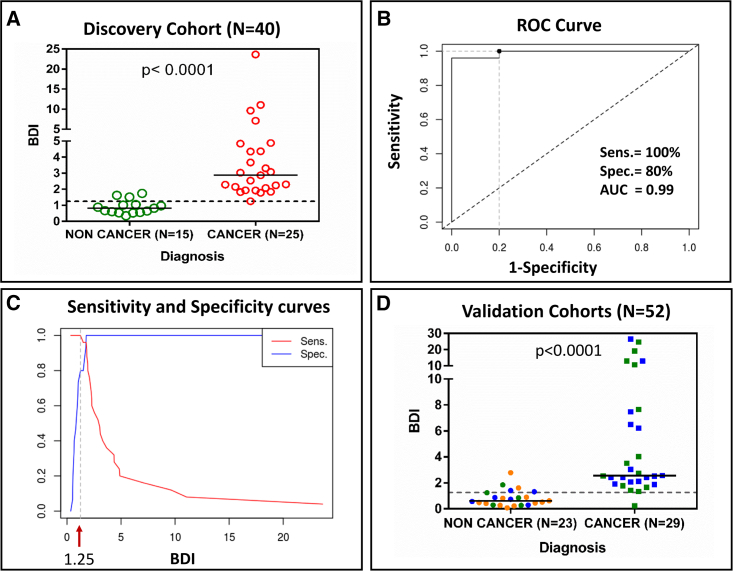

Discovery-phase study

For the discovery-phase study, we recruited 40 subjects (Table S1B) from University Hospitals Medical Center, Department of Otolaryngology (Cleveland, OH). A standard protocol, approved by the University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center (UHCMC) Institutional Review Board (IRB), was followed, including informed consent documentation (IRB#: 07-15-03C/CASE4315). To avoid inter-operator variability, the same clinician collected paired cytobrush samples from the lesional and contralateral sites of each subject, respectively, before the biopsy of each lesional site. The anatomical locations of each lesion within the oral cavity are described in Table S1B. Of the 40 oral lesions, 25 were diagnosed by pathology review as being cancerous while 15 were benign (see Table S1B diagnoses). The median age of the two patient cohorts was 65 (range 39–91) and 56 (range 35–73) years, respectively (p > 0.05). One laboratory operator generated BDI values to avoid inter-operator variability. The samples were intentionally blinded so that pathologist-determined diagnoses were revealed only after BDI scores were obtained for all patients. As shown in Figure 4A, the BDI of cancerous subjects (n = 25) was significantly (p < 0.0001) higher than that of non-cancerous subjects (n = 15). Next, we investigated the diagnostic accuracy of BDI in differentiating cancerous vs. non-cancerous lesions by receiver-operating characteristic curve analysis (Figures 4B and 4C). The area-under-the-curve was found to be 0.99 (Figure 4B). One desirable characteristic of an adjunct test intended to be used in a primary care setting is having a high sensitivity to minimize the proportion of false-negative (FN) results to avoid missing patients requiring biopsy or referral43 and, hence, we used the “MaxSe” (maximizes sensitivity) approach.44 We arrived at a BDI cutoff value of 1.25 and found 100% sensitivity with an acceptable specificity value of 80% (Figures 4B and 4C). These results support BDI as a promising index for screening OSCC and may serve as a triage tool before traditional biopsy.

Figure 4.

BDI discovery and validation study

(A) BDI values for 15 non-cancerous and 25 OSCC lesions from the discovery cohort. Black horizontal line for each cohort is the median BDI value. Dashed gray line is the cutoff value (1.25) for cancer diagnosis. p value was calculated by non-parametric Mann-Whitney test.

(B) Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve.

(C) Sensitivity/specificity vs. BDI curves for the discovery cohort.

(D) BDI values for 23 non-cancerous and 29 OSCC lesions from the three validation cohorts (blue: internal validation cohort [n = 21]; green: external validation cohort 1 [n = 19]; orange: external validation cohort 2 [n = 12]). Dashed gray line is the BDI cutoff value (1.25) for cancer diagnosis. Diagnoses of all the lesions are found in Table S1.

Validation study

The validation study consisted of three non-overlapping cohorts, one internal and two external. All three sites used the same IRB-approved protocol described in the discovery study above. For the internal cohort (UHCMC), multiple clinicians provided cytobrush samples, while one laboratory operator generated the BDI scores. For the external cohorts, cytobrush samples were collected by multiple clinicians, and BDI scores were generated by multiple laboratory operators in the Cincinnati site while in the West Virginia site there was one lab operator. Diagnoses based on pathology review of respective lesions are shown in Tables S1C–S1E). The blinded analysis confirmed that the BDI values of OSCC patients were also significantly higher (p < 0.0001) in all subjects with OSCC lesions when compared to benign lesions (Figure 4D). We then calculated the sensitivity and specificity of the BDI, based on the threshold value of 1.25 from the discovery cohort, and found overall sensitivity of 98.2% and specficity of 82.6%. For all the subjects (n = 92), sensitivity/specificity and positive/negative predictive values, with a confidence interval of 95%, are shown in Table 1. Among 92 subjects, we recorded eight false positives (FPs) and one FN (Tables 1 and S1). The FPs and FN are highlighted in Table S1. Importantly, most of the FPs were diagnosed as being dysplasia/hyperkeratosis. Implications of these outcomes are highlighted in the discussion.

Table 1.

Sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of BDI in OSCC detection

| Values (BDI vs. biopsy) | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|

| True positive, TP | 54 | – |

| True negative, TN | 38 | – |

| False positive, FP | 8 | – |

| False negative, FN | 1 | – |

| Sensitivity, TP/(TP + FN) | 98.2 | 90.28%–99.95% |

| Specificity, TN/(TN + FP) | 82.6 | 68.58%–92.18% |

| Positive predictive value | 87.10 | 78.22%–92.69% |

| Negative predictive value | 97.44 | 84.44%–99.63% |

Sample size and power calculation

In a post hoc evaluation of power, using a non-parametric Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney test to detect a statistical difference in BDI levels in the discovery cohort (total of 40 subjects; 25 OSCC: mean = 4.4, SD = 4.7; 15 benign: mean = 0.9, SD = 0.43) for a two-sided and one-sided alpha of 5%, there was >86% and >92% power, respectively. In the validation cohort (total 52 subjects; 29 OSCC: mean = 6.1, SD = 6.9; 23 benign: mean = 0.8, SD = 0.64) there was >96% and >98% power to detect a significant difference for a two-sided and one-sided alpha of 5%, respectively. Therefore, both cohorts were well powered to detect differences in BDI.

Cohort characteristics, BDI, and clinical parameters

Demographic information (e.g., age, gender, and smoking status) along with lesion location in the oral cavity and diagnosis based on pathology review is included for every subject in the proof-of-principle, discovery, and validation studies (Tables S1 and S3). Since smoking is a risk factor for OSCC,45 we wanted to determine whether BDI values correlated with smoking status (e.g., never or non-smokers; former and current smokers). Not surprisingly, the BDI values of both current and former smokers were significantly higher than those of non-smokers (Figure S4A). Moreover, we found that male participants had significantly higher BDI values compared to female participants (Figure S4B) consistent with the literature, showing that males smoke more than females and OSCC is more prevalent in males.46,47

The prevalence of OSCC based on anatomical sites of the oral cavity has been well documented.7 Our oral cancer cohort data showed that the tongue was the most frequent site for OSCC (36%) followed by the floor of the mouth (FOM) (26%) (Figure S4C). This is in agreement with published data of patients in the United States, where the tongue is the most common intra-oral site of OSCC and accounts for 25%–40% of all OSCCs, followed by FOM (15%–20%).7,48 When we compared BDI values based on oral anatomical locations; i.e., cheek, tongue, and all other locations combined, for both benign and cancerous lesions, respectively, we found that anatomical location was not a factor affecting BDI scoring within benign and within OSCC lesions (Figure S4D). We also found no correlation between BDI levels and severity of cancer stage; i.e., high BDI scores were not associated with late-stage OSCC (Figure S4E).

Benchmarking of BDI against other OSCC biomarkers/platforms

Several biomarkers have been studied to detect OSCC, and a few OSCC detection platforms have been proposed, with some in clinical use as well.43,49,50 The BDI was benchmarked against salivary (protein, mRNA, and microRNA [miRNA] based) and serum biomarkers (protein and miRNA signature based), as well as against visual aids and cytological- and transcriptomic-based detection platforms. These are shown in Figure S5A and Table S4. Figure S5 shows that the BDI is the most sensitive (98%) in detecting OSCC when compared against all the other biomarkers (sensitivity ranges 32%–93%) (Figure S5B), as well as against all commercially available/in-use detection platforms (sensitivity ranges 69%–94%) (Figure S5D). Some biomarkers (e.g., salivary DUSP1, S100P, CPLANE, and serum GAS6) and platforms (e.g., OralCDx, CancerDetect for Oral and Throat cancer [CDOT], and point-of-care oral cytology tool [POCOCT]), however, showed better specificity than BDI (Figures S5C and S5E). We address the BDI specificity issue and that of other biomarkers/platforms in the discussion.

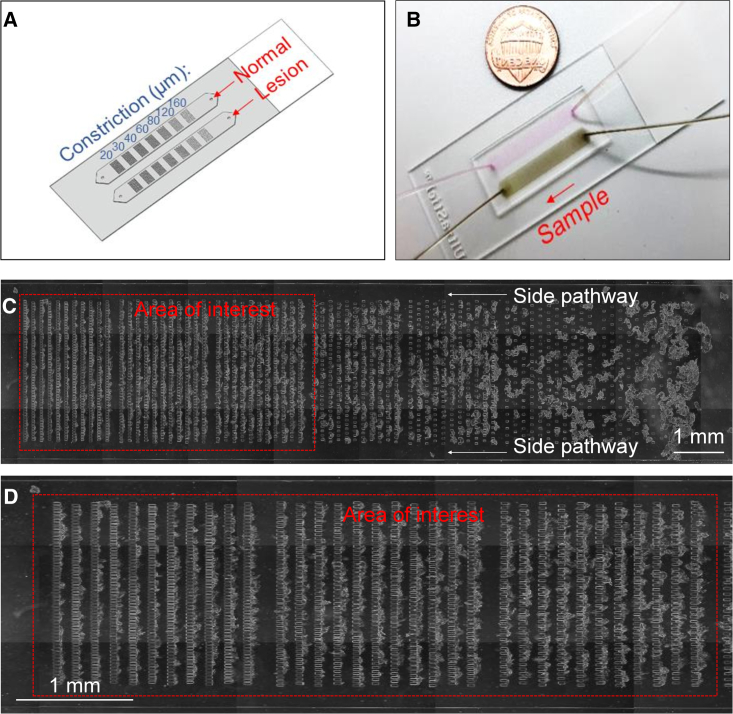

Development of a microfluidic platform to determine BDI proof of principle

We explored the possibility of translating our laboratory-based BDI biomarker assay into a microfluidic test, which we refer to as the microfluidic intact cell assay (MICA). The MICA detection principle utilizes the trapping of mucosal cells in a microfluidic chip by incorporating arrays of microfabricated polydimethylsiloxane pillars of variable spacing ranging from 160 μm to 20 μm to capture the cells without the need for surface chemistry (Figure 5A). The trapped cells are then exposed to 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS to permeabilize cell membranes, followed by incorporation of anti-hBD-3 and anti-hBD-2 Alexa Fluor-conjugated antibodies to detect respective hBDs and quantify the BDI. The design concept of MICA is similar to that of the previously developed OcclusionChip,51 where micropillar arrays were embedded into the microchannel forming narrow openings along the flow direction, coupled with two 400-μm-wide side passageways. MICA is designed such that large cell aggregates are retained upstream within the coarse openings and individual cells are retained downstream within the narrower openings. The side passageways are designed to prevent clogging of the near-inlet portion of the micropillar arrays. The MICA microchannel overall dimensions are 27 mm × 4 mm × 120 μm (length × width × height). A photograph of MICA is shown in Figure 5B. The microscopic phase-contrast image shown in Figures 5C and 5D represents a typical cell distribution in the MICA microchannel and confirms that cell aggregates were being filtered upstream while individual cells were retained downstream.

Figure 5.

A microfluidic intact cell assay device

(A) Schematic illustration of a microfluidic intact cell assay (MICA) device with embedded micropillar arrays forming narrow openings from 160 μm down to 20 μm along the flow direction for cell aggregate filtering and individual cell retention.

(B) Photograph of an assembled MICA device.

(C) Cytobrush samples were collected from the lesion and the contralateral normal sites of patients and pumped through micropillar arrays within respective troughs of the MICA device. Representative microscopic image shows typical distribution of the retained cells in the MICA microchannel.

(D) The area within the dashed red lines seen in (C) indicates the area of interest.

To demonstrate the preliminary efficacy of this platform, we used cytobrush samples from cancerous lesions and corresponding contralateral sites and incubated cells in the MICA chip with fluorescent antibodies to epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). EGFR was selected as a proof-of-principle marker, as it is overexpressed in up to 90% of all OSCC patients52,53,54 and its activation results in hBD-3 expression.55,56,57 Consistent increases in fluorescence intensities emanating from OSCC cells compared to contralateral cells (Figure S6), demonstrating EGFR overexpression in OSCC, strongly suggested that the MICA platform could be used for BDI determinations.

To test the translational potential of the BDI biomarker using the MICA platform, we collected cytobrush samples from OSCC lesional sites and contralateral sites of five OSCC patients and from five healthy subjects’ left and right cheek (or tongue). Cells, after mild detergent treatment to permeabilize their membranes, were incubated with fluorescent antibodies specific for either hBD-3 or hBD-2, and BDI scores were determined as described in STAR Methods. Representative phase-contrast, hBD-3, hBD-2, and DAPI-stained images are shown in Figures 6A and 6B. Significantly higher (p = 0.03) BDI values in OSCC lesions compared to healthy tissue were observed, as shown in Figure 6C. These results demonstrate that the BDI biomarker, using the MICA platform, could be developed into a point-of-care device in the future.

Figure 6.

MICA-BDI proof of concept

(A) Representative results of phase-contrast, hBD-2 and hBD-3 fluorescence, and DAPI staining of nuclei of the cells collected from a healthy participant’s right and left cheek. A violin plot shows no significant difference in hBD-3/hBD-2 ratio in cells collected from left vs. right side of the healthy participant.

(B) Representative results of phase-contrast, hBD-2 and hBD-3 fluorescence, and DAPI staining of nuclei of the cells collected from a cancerous patient’s lesional and contralateral side. A violin plot shows a significantly higher hBD-3/hBD-2 ratio in cells collected from the lesional side compared to the contralateral side.

(C) Patients diagnosed with OSCC had significantly greater BDI values compared to healthy participants (p = 0.033, Mann-Whitney; n = 5 in each group).

Discussion

The literature is fraught with conflicting and contradictory findings regarding expression levels and involvement of human beta-defensins in cancer (reviewed by Ghosh et al.29). For example, hBD-1 has been reported to be downregulated in oral, skin, liver, kidney, and colon cancers but upregulated in lung cancer. Its suppression in prostate, renal, bladder, and/or oral cancer might contribute to cancer cell survival and tumor progression.29,58,59,60 HBD-2 is downregulated in oral cancer, as we and others have reported,23,25,37,61 while it is upregulated in other cancers (e.g., esophageal, lung, and cervical).29,61,62,63,64 Interestingly, in cancers where hBD-2 is suppressed, migration and proliferation of cells emanating from those cancers is inhibited, while in cancers where it is overexpressed it promotes respective cancer cell growth.62,64,65

HBD-3 is also differentially expressed and is either pro- or anti-carcinogenic depending on the cancer type being investigated (reviewed in Ghosh et al.29). Similar to other AMPs, in those cancers where hBD-3 is overexpressed, namely OSCC38 and cervical cancer,66 hBD-3 is associated with neoplasia, while in cancers where it is underexpressed, namely in colon cancer, it is associated with inhibition of neoplasia.29,66,67

Evidence for hBD-3 pro-oncogenic activity in OSCC is growing. It has been shown to stimulate tumor growth and migration,66,68 confer resistance of tumor cells to apoptosis,69 help to recruit TAMs to the tumor site and promote tumor progression,25,69 and enhance PD-L1 expression on OSCC tumor cells.28 Consistent with the oncogenic role of upregulated hBD-3, mouse beta-defensin 14, its ortholog, acts as a chemoattractant to enhance angiogenesis and tumor development in vivo,70 induces Treg conversion, and inhibits cytotoxic CD8+ T cells,27 i.e., central to immune tolerance and cancer immune evasion.

Additional evidence includes hBD-3’s ability to act as a chemokine in specifically recruiting TAMs, but not T cells, to the tumor site through its interaction with the myeloid-specific receptor CCR2.25 We confirmed this by inhibiting monocytic cell migration in response to hBD-3 by cross-desensitization with CCL2, the cognate ligand for CCR2, and by the specific CCR2 inhibitor, RS102895.25 Moreover, by using hBD-3-expressing tumor cells, we induced massive tumor infiltration of host macrophages in a mouse model, resulting in enlarged tumors.25 This mechanism was evidence of an hBD molecule orchestrating in vivo activity and demonstrating the importance of hBD-3 in the development of tumors.

EGF, the important ligand that activates EGFR to promote epithelial cell proliferation, activates hBD-3 via MAPK MEK 1/2, p38, PKC, and PI3K, but not JAK/STAT,23 suggesting that hBD-3 could serve as a mitogen-responsive gene in the initiation of oral cancer. Interestingly, p53, the important tumor suppressor,71 binds the promoter region of the hBD-3 gene and inhibits its expression.24 Moreover, the lack of hBD-2 expression in early OSCC with concomitant high levels of hBD-3 can be explained by differential regulation of these AMPs; hBD-3 requires EGF/EGFR activation for expression,57,72 while nuclear factor kappa-B transcription factor activation triggers hBD-2 expression.73 We exploited this dichotomy of expression, which we saw repeatedly in multiple examples of CIS and OSCC (Figure 1C), as the basis for a functional non-invasive detection platform for early OSCC.

The gold standard for OSCC diagnosis remains a biopsy followed by pathology review. However, this method has several important limitations. The scalpel biopsy for diagnosis is costly and invasive and can sometimes be associated with increased adverse events. Furthermore, in underdeveloped nations, pathology reviews are often imprecise and misreported. Additionally, monitoring diseases such as leukoplakia-, lichen planus-, and betel-nut-related dysplasia by intermittent biopsies is not practical due to the invasive nature of incisional biopsies. Moreover, in oral primary care settings in the Western world, clinicians tend to over-biopsy, with greater than 90% resulting in, thankfully, benign outcomes but unnecessary stress, cost, and discomfort.74 For these reasons, a non-invasive assay to discriminate OSCC lesions from benign ones is an attractive adjunct/alternative and could be used to determine whether a patient actually requires a biopsy.

A major critique of non-invasively collecting oral lesional samples has been the very high rate of FN outcomes.43,75 This is clearly unacceptable when attempting to discern an oral cancerous lesion from a non-cancerous one and has been primarily attributed to the inability of various instruments, namely a metal spatula, wooden tongue depressor, or cotton-tipped applicator, to collect cells representative of the entire lesion; especially the deeper layers.76 Over the last several years, the introduction of cytobrushes and a proper cytobrushing technique have revived the application of oral cytology.77,78 The Orcellex brush (Rovers Medical Devices, The Netherlands) is the latest cytobrush customized for use in the oral cavity. Ample numbers of cells with good cell morphology and staining characteristics, where cells representing all layers of the oral mucosa are obtained,77 and where consistent appearances of cancer cells vs. normal cells from cytobrushed OSCC vs. contralateral sites within the same patient are found.

In our multi-center study, we included a discovery cohort followed by three independent validation cohorts (one internal and two external). To eliminate potential bias, both the discovery and validation phases were intentionally run as blinded studies, where BDI results were only compared to pathology review once all paired samples, per respective study, were processed. The studies conducted through the network of dental offices affiliated with the WVU Dental School and the Department of Otolaryngology at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center demonstrated that, irrespective of the location, by following a standard protocol, different clinicians could provide cytobrush samples and different technicians could process the samples and obtain BDI results with similar high sensitivity and specificity seen in our internal discovery-phase study. The validation studies also revealed vulnerable aspects of the protocol that require attention in order for the BDI platform to work. These included first making sure that proper cytobrushing techniques, i.e., applying deep pressure with multiple turns of the brush, are applied to both sites of the oral cavity in order to obtain enough cells to run the ELISA. Second, minimizing human error so that lesional and contralateral samples are not incorrectly labeled is essential in obtaining a correct BDI score. Reversing the samples results in an inverse of the actual BDI; i.e., what we believe happened in our one and only FN result obtained through the validation study at CMC (where the BDI score was reported as 0.23 [Figure 4D and Table S1]).

In the discovery and validation studies, we reported eight FP cases. These included dysplastic and hyperplastic/hyperkeratic lesions, fibroma, squamous papilloma, and geographic tongue. The common denominator of most of these lesions is excessive proliferation of epithelial cells resulting in overexpression of hBD-337 and, therefore, leading to a BDI score suggestive of cancer. Dentists, primary care physicians, and ENT specialists are trained to distinguish HPV-related papillomas, fibromas, and hyperplasias (usually caused by irritations) from oral cancer. Therefore, the BDI would not be recommended to discern such lesions. However, leukoplakias, some of which have been shown to overexpress hBD-3,79 are white lesions that often include dysplasias, can be pre-cancerous,15,80 and are frequently indistinguishable as such. In these cases, while the BDI would score them as cancer, it would inform the clinician to perform a biopsy. Additionally, one of the benefits of using the BDI would be the reduction of unnecessary biopsies conducted by dentists in the United States from >90% to 17.4% when considering the FP rate of 82.6%.74 The clinician, in consultation with the patient, would then decide whether to excise the entire lesion or track it over time. Over time (4.5–8.1 years) nearly 17% of patients with leukoplakia, diagnosed through biopsy as mild dysplasia, will go on to develop invasive OSCC.15,16 Therefore, longitudinal studies are necessary to determine whether the BDI could be used as a non-invasive tracking method for pre-cancerous lesions, a study we are currently conducting.

Our benchmark analysis comparing the BDI to 12 other OSCC biomarkers and six detection platforms determined that the BDI is the most sensitive in distinguishing cancerous from benign lesions. It is important to note that, while some of the salivary and one serum biomarker exhibited higher specificity than the BDI, they come with several limitations. Salivary biomarker quantification is influenced by collection methods, time of saliva collection, circadian rhythm, medications, radiation therapy, and certain autoimmune diseases that can influence salivary flow.81,82 Moreover, saliva contains multiple proteolytic and hydrolytic enzymes that can degrade proteinaceous, mRNA, and miRNA biomarkers.82

Some OSCC detection platforms report higher specificities than BDI (Figure S5E), while others show inconsistencies in specificity and positive predictive values across studies.83 For example, when applied to benign-appearing oral epithelial lesions, the accuracy of OralCDx was reduced greatly and the rate of FP results increased.84,85 Additionally, the sensitivity and specificity values for both POCOCT and CDOT were based on results obtained from cancer vs. healthy controls, not cancer vs. suspicious lesions, as in the current study, where the latter were adjudicated as benign following biopsy and pathology review. In comparison, BDI was tested to determine not only whether it could detect oral cancer but also how well it could differentiate cancer from benign lesions. If subjects with benign lesions would have been included as controls in the POCOCT and CDOT studies, specificity values would have been reduced.84,85

While sensitivity and specificity are important parameters, so are cost, ease of use, turnaround time, ability to translate the platform into a point-of-care device, and interpretation of results. Conventional cytology is more subjective and the CDOT platform, while objective, involves complex sample processing and data analysis.49 This method includes salivary RNA extraction using a custom silica-bead-based protocol, on-bead DNA removal by DNase, RNA quantification, removal of bacterial and human rRNAs from the specimen using a subtractive hybridization method, conversion of RNAs into Illumina directional sequencing libraries, and sequencing data processing through a bioinformatics pipeline. POCOCT and CDOT require sophisticated expertise and equipment and presumably would be much more expensive, with a longer turnaround time,86 than the other tests including the BDI.

The BDI, besides being the most sensitive of all the platforms, has several other advantages; (1) subjects are their own control, thus minimizing the effects on confounding variables; (2) samples from normal and lesion sites are analyzed simultaneously, thus minimizing inter-assay variability; (3) easy sample processing; (4) unlike other ELISA-based assays, the determination of total protein is not necessary; (5) it provides an objective quantitative measure, i.e., eliminating subjectivity in interpreting results; and (6) it has the potential to translate into a chairside point-of-care device.

We believe that the BDI has utility in various clinical situations, i.e., it could aid the primary care provider in deciding which patients would benefit from a biopsy, thus reducing unnecessary pain, stress, and cost, and the BDI could be used in patients presenting with extensive or numerous oral lesions for which multiple biopsies are not realistic. Additionally, the BDI could empower the practitioner by knowing a priori if a lesion actually requires a biopsy; i.e., the compliance rate could increase significantly. In an unbiased survey conducted in Cleveland, Columbus, and Morgantown of primary care dentists (n = 100 interviewed) through the National Science Foundation’s Innovation Corps (I-Corps) program at the Ohio State University in 2018, >85% of primary care dentists felt a need to be able to determine when a biopsy was necessary and were eager to use the BDI diagnostic platform in their clinics.

Based on our BDI discovery and validation study (Figure 4), a value of or above the cutoff of 1.25 would indicate cancer and would necessitate a biopsy. A value of 10% below the cutoff (i.e., 1.125) and up to the cutoff would be a safe score to recommend a biopsy as well, despite the fact that this would not indicate cancer. The 10% leeway is based on our earlier work showing inter-assay variability of BDI values determined by ELISA.87 Importantly, this process would significantly reduce unnecessary biopsies conducted in primary care facilities. Coupled with compliance, the BDI could be of value in rural areas where the practitioner is isolated from major health centers and access to pathology services is limited. Moreover, since the BDI may be used as a biomarker for any squamous cell cancer, e.g., skin, upper two-thirds of esophagus, cervical, or anal, its utility increases tremendously.

The success of a shift from curative to predictive and pre-emptive medicine relies on the development of “portable monitoring devices” for point-of-care testing. Our MICA system has the potential to allow rapid detection of OSCC through direct capture of cells representing the entire lesion and subsequent analysis of the BDI. This point-of-care approach could be used in the dental clinic, physician’s office, in the field, or in the hospital. Additionally, the MICA would fill a major unmet need in low-socioeconomic countries where oral cancer is highly prevalent but laboratory/pathology services are lacking.

Finally, the BDI opens the possibility of discovering additional biomarkers associated with oral dysplastic lesions. Since hBD-3 is both a specific dysplasia-derived agent and a potent AMP that demonstrates pro-oncogenic activity, its overexpression may promote a signature compositional shift of the local microbiome and contribute to an immunosuppressive local environment that facilitates OSCC progression. Several studies have shown a compositional microbial shift in OSCC lesions when compared to contralateral normal sites in the same patient.88 The resulting “dysbiosis” is a state in which healthy commensal bacteria are depleted while putative pathogenic ones emerge and overgrow. The oral species Fusobacterium nucleatum (Fn) has been targeted in multiple studies in conjunction with OSCC as well as other cancers of the body,89,90 including in esophageal91 and colorectal cancers.92,93 Moreover, certain oral candidal species have also been shown to accelerate tumor growth.94 It is therefore likely that overexpression of hBD-3 in early OSCC lesions may contribute to an hBD-3-resistant microbial community that contributes to lesional exacerbation. We reported that certain strains of Fn and certain candidal species are resistant to hBD-395 and are currently generating a library of hBD-3-resistant Fn clinical isolates from OSCC lesions to test their pro-oncogenic potential. With microbial-based biomarkers showing promise in other cancers,96,97 we foresee the future possibility of combining BDI results with microbial biomarkers to better identify oral cancerous lesions and possibly detect dysplastic ones that are progressing to cancers.

Limitations of the study

Limitations of the study include that, unlike saliva- or blood-based OSCC detection platforms, BDI sampling requires that a suspicious lesion be visible and accessible for sufficient cytobrush cell collection. Moreover, the threshold single cutoff of 1.25 for BDI was derived from a single-center discovery-phase study and thus did not have the power to account for the potential impact of demographics, anatomical location, and/or pathological types of lesions on that value. Larger multi-center/multi-national studies to include more demographically diverse populations should be conducted to determine the impact of these factors on BDI cutoff value. However, because patients are their own controls for BDI, factors such as gender and anatomical location of lesions should have less of an impact on the BDI cutoff value. Additionally, prospective studies are warranted to validate the utility of BDI for monitoring progression of oral lesions over time.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-Human BD-2 | Peprotech | Cat# 500-P161G; RRID:AB_2929558 |

| Anti-Human BD-3 | Peprotech | Cat# 500-P241; RRID:AB_2930000 |

| Biotinylated Anti-Human BD-2 | Peprotech | Cat# 500-P161GBt; RRID:AB_2929561 |

| Biotinylated Anti-Human BD-3 | Peprotech | Cat#500-P241Bt; RRID:AB_1268564 |

| Defensin beta 2 Polyclonal Antibody, ALEXA FLUOR® 647 Conjugated | BIOSS | Cat# BS-4307R-A647 |

| beta Defensin 3 Polyclonal Antibody, FITC Conjugated | BIOSS | Cat# BS-7378R-FITC |

| Human E-Cadherin PE-conjugated Antibody | R&D | Cat# FAB18381P RRID:AB_357102 |

| beta Defensin 3 Polyclonal Antibody, ALEXA FLUOR® 488 Conjugated | BIOSS | Cat# BS-7378R-A488 |

| β defensin-2 antibody | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# SC-10854; RRID:AB_2091977 |

| beta-Defensin 3 Antibody | NOVUS | Cat# NB200-117 RRID:AB_10001351 |

| Biological samples | ||

| Cytobrush Samples | University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center UHCMC; Dental Clinics in Morgantown (WV); University of Cincinnati Medical Center, Cincinnati (OH) | NA |

| Saliva Samples | University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center UHCMC | NA |

| Oral Tissue samples | University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center UHCMC | NA |

| FFPE tissue | Case School of Dental Medicine, OH | NA |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Recombinant Human BD-2 | Peprotech | Cat#:300-49 |

| Recombinant Human BD-3 | Peprotech | Cat#:300-52 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Defensin 2, beta (Human) - ELISA Kit | Phoenix Pharmaceuticals | Cat#EK-072-37 |

| Defensin 3, beta (Human) - ELISA Kit | Phoenix Pharmaceuticals | Cat#EK-072-38 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Graphpad Prism v6 | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com |

| FlowJo 10.5.3 | FlowJo, LLC | https://www.flowjo.com |

| GEPIA | Tang et al.32 | http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/ |

| UALCAN | Chandrashekar et al.31 | https://ualcan.path.uab.edu/ |

| easyROC | Goksuluk et al.44 | http://biosoft.erciyes.edu.tr/app/easyROC/ |

| GEDS | Xia et al.30 | http://bioinfo.life.hust.edu.cn/web/GEDS/ |

| LinkedOmics | Vasaikar et al.35 | http://www.linkedomics.org |

| Other | ||

| Rovers® Orcellex® Brush RT | Rovers Medical Devices | REF#380380331 |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for recourses and reagents should be directed to the lead contact, Aaron Weinberg (axw47@case.edu).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

-

•

xE whole exome sequencing data reported in this paper is included as supplemental file (xE whole exome sequencing data of cytobrush samples).

-

•

This study does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this work paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Experimental model and study participant details

Human samples

We followed guidelines from Standards for Reporting Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD) 2015 for this study.98 Detailed exclusion and inclusion criteria are described in Table S2. For the tissue immunofluorescence microscopy study, tissue samples (n = 54) were retrospectively collected from the Department of Oral Pathology, Case Western Reserve University School of Dental Medicine, and a waiver of informed consent was approved by the Case Western Reserve University Comprehensive Cancer Center (CCCC) Institutional Review Board (IRB). For Flow Cytometric analysis, four paired cytobrush samples and respective biopsy tissues were obtained from the Dept. of Otolaryngology, University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center UHCMC (Cleveland). For BDI proof-of-concept, discovery phase, internal validation studies and POC proof of concept studies, paired cytobrush samples were collected from 8, 40, 21 and 5 subjects, respectively, from the Dept. of Otolaryngology, UHCMC [Figure 3C]. These studies were approved by the IRB of UHCMC (07-15-03C/CASE4315). For external validation study 1, the study was approved by the University of Cincinnati Medical Center’s (UCMC) IRB [# 2019-0595], and 19 subjects were recruited from the greater Cincinnati area. For external validation study 2, the study was approved by the West Virginia University (Morgantown) IRB [#1904526911], and 12 subjects were recruited from multiple primary care dental clinics in West Virginia. Informed consent was obtained for all participants in all the studies. Incisional biopsies of all lesions were conducted as the standard of care, after cytobrushing the lesions, Board-certified pathologists determined respective diagnoses.

Method details

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) biopsy specimens were obtained from the Department of Oral Pathology, Case Western Reserve University School of Dental Medicine. We previously described methods for immunofluorescence microscopy.23,24,25 Briefly, each section (5 μm) was de-paraffinized in xylene and hydrated with serially diluted ethanol, followed by antigen retrieval at 98°C in a high pH Target Retrieval Solution (Dako Co.) and blocking with 10% donkey serum containing 0.25% Triton X-100, overnight at 4°C. After washing with PBS, each section was incubated with the respective (anti hBD-3 [NOVUS Biologicals], anti-hBD-2 [Santa cruz Biotechnology]) primary antibody (1 h, room temperature), washed in PBS (3 × 10 min), and then stained with the compatible fluorescent dye-conjugated secondary antibody. For double immunofluorescence, consecutive staining by different primary and secondary antibodies was performed. Isotype controls were conducted using isotype-matched IgGs, corresponding to each primary antibody. Sections were mounted on slides using VECTASHIELD Fluorescent Mounting Media (Vector Lab Inc., Burlingame, CA) containing DAPI to visualize nuclei. Immunofluorescent images were generated using a Leica DMI 6000B fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems, Bannockburn, IL) or an Olympus BX51 fluorescence microscope mounted with the Olympus DP71 camera (Olympus America Inc., Center Valley, PA). Immunofluorescence images were processed using the NIH ImageJ program.99 To quantify expression levels of each defensin, normal, CIS and OSCC immunofluorescent images of hBD-2 and hBD-3 were acquired in 16-bit gray scale, respectively. Fluorescent densities on each of the antibody treated sections were measured with ImageJ as described previously.23,99 The expression of hBD-2 and hBD-3 was represented as the ratio of relative fluorescence intensity of hBD-2 and hBD-3 over that of nuclei, respectively.

Cytobrush sample collection procedure

All cytobrush samples were obtained using Rovers Orcellex Brush (Rovers Medical Devices, Oss, Netherlands) for cytobrushing oral mucosa based on Kajun et al.77 showing good quality mucosal cell collection with this cytobrush. Each participant was first asked to rinse his/her mouth with water. Before performing a biopsy, the clinician applied the cytobrush onto the mucosal surface of the suspicious lesion and, with pressure, turned the brush head 10 turns to collect as much of the entire thickness of the lesion as possible. The brush was then inserted into a sample collection tube (containing 2 mL of PBS) and placed on ice. The same procedure was then conducted on the contralateral normal side of the oral cavity. The paired samples were stored at −80°C, until used (for ELISA). For MICA, the samples were collected in PBS and added to ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) containing vacutainer tubes. EDTA was used to prevent sample coagulation since bleeding was observed during sample collection in some cases. For FACS and MICA samples, where intact cells were required, samples were processed within 2–3 h post collection. For all subjects, biopsy samples were collected per standard-of-care clinical procedure. For MICA, the samples were collected in PBS and added to (EDTA) vacutainer tubes.

xE whole exome sequencing

xE whole exome sequencing of paired cytobrush samples (OSCC lesional and contralateral) was performed by Tempus Labs, Inc., (Chicago, IL, USA).100,101,102,103 Tempus xE is a whole exome next-generation sequencing proprietary assay which analyzes the entire coding region (exome) of the patient’s genome, combined with whole transcriptome RNA sequencing. This was done as a tumor:normal matched assay for each tumor and contralateral normal cytobrush specimen, sequenced to an average depth of 250x and 150x, respectively. Whole transcriptome RNA-seq was 50 million reads encompassing 19,396 genes covering ∼39 Mb of genomic space. The cytobrush samples from OSCC lesions were matched to corresponding contralateral normal samples to ensure fidelity of somatic variant calling. From DNA sequencing, somatic and single nucleotide variants, insertions and deletions and copy number variant data were generated.

Cytobrush sample processing for flow cytometry of defensins

For flow cytometry staining, single-cell suspensions were obtained from cytobrush samples by resuspending the samples in a PBS-based, enzyme-free cell dissociation buffer (Gibco) at room temperature for 5 min, followed by passing suspensions through 100 μM cell-strainers. Excised tumors were processed by collagenase digestion (0.5 mg/ml) for 8 min at room temperature. The cells were then centrifuged in PBS/BSA before sequential flow cytometry staining for E-cadherin, hBD-2 and hBD-3 proteins. For intracellular staining, the cells were washed after surface E-cadherin staining, fixed, permeabilized and stained with antibodies for intracellular hBD-2 and hBD-3 proteins. Live-Dead viability staining (Life Technologies/Thermofisher) was used to remove dead cells in the flow cytometry analysis. Data was acquired using a BD Fortessa cytometer. PE-conjugated anti-human α-E-cadherin polyclonal antibody was purchased from R&D systems. Alexa-flour 647 conjugated hBD-2, and FITC conjugated hBD-3 polyclonal antibodies were purchased from BIOSS (Woburn, Massachusetts, U.S.A.). Standard non-stained and single stain controls were used for flow cytometry to determine gates. At least 1000–3000 E-Cad+ viable cells were gated for the flow cytometry analysis of hBD-2 and -3. These were pre-gated on cells stained with a Live-Dead marker to exclude non-viable cells. Fluorescence compensation and data analysis were standard methods performed using appropriate unstained and single-stained controls using BD FACSDiva and FlowJo 10 software.

Cytobrush sample processing for ELISA

Briefly, paired samples from each subject were thawed on ice, and cells were dislodged from each cytobrush by flicking and subtle vortexing of the collection tube. After discarding the brush, the fluid (∼2mL) was centrifuged at 300 x g for 5 min, and the supernatant was discarded. The remaining cell pellet was lysed in 200μL of RIPA buffer, followed by centrifugation at 10,000 x g at 4°C for 10 min. The resultant supernatant (cell lysates) was collected and used for the ELISA assay.

Beta defensin ELISA and determination of BDI

For the proof-of-concept, discovery phase, and internal validation studies, we used a sandwich ELISA with optimized hBD-2 and hBD-3 antibody pairs from Peprotech (NJ).87,104 Briefly, 96-well immunoplates (R&D Systems, MN) were coated with 50 μL anti-hBD-2 or hBD-3 antibodies (Peprotech, NJ) diluted to 1 μg/mL, 4°C, overnight, followed by blocking with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The paired cell lysates (20 μL) along with 80μL of RIPA buffer were added to each experimental well (in duplicate) and 100μL of RIPA buffer was added in two additional wells (blank wells). The plate was then incubated at room temperature (RT) for 1 h. The wells were washed 3 times with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 and incubated with 50 μL of the biotinylated secondary antibody (Peprotech, NJ) diluted to 0.1 μg/mL, at RT, 30 min. Each well was washed 3 times, 50 μL/well of streptavidin-peroxidase (R&D Systems, 1:200 in wash buffer) was added to each well and incubated for 20 min at RT. Each well was washed again (3 times with wash buffer) and incubated with 100ul of Reagent A and B (1:1) for 20 min, after which the reaction was stopped with a μl/well of stop solution (2N HCL) (R&D Systems). Absorbance was measured at 450 nm with a microplate reader. For the external validation studies, hBD-2 and hBD-3 ELISA kits from Phoenix Pharmaceuticals (Burlingame, CA) were used and ELISAs were performed per vendor’s instruction using 20μL of cell lysates.

We determined the BDI from ELISA data using the following steps: i) Determined the average OD values for each sample (from OD of duplicate wells) and blank wells, ii) Subtracted OD values of the blank well (hBD-2 ELISA) from OD values of the sample well [(hBD-2 ELISA) = ODhBD-2], iii) Subtracted OD values of the blank well (hBD-3 ELISA) from OD values of the sample well [(hBD-3 ELISA) = ODhBD-3], iv) Determined the BDI for each subject using the following equation:

A = [ODhBD-3]/[OD hBD-2] for sample (#XL) collected from lesional site of subject #X; B = [ODhBD-3]/[OD hBD-2] for sample (#XN) collected from contralateral control (normal) site of the same subject (#X); BDI = A/B.

Microfluidic intact cell analysis (MICA): Micropillar array construction and processing of cytobrush samples

The MICA device was fabricated using established soft lithography protocols as previously described.105,106 Briefly, a 3-in silicon wafer (University Wafers, Boston, MA) was spin-coated with a negative photoresist (SU-8 2035, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) at 1000 rpm/min and soft-baked at 95°C for 20 min. The wafer was then UV-patterned under a photomask, post-exposure baked (95°C, 10 min), developed in a photoresist solvent (propylene glycol monomethyl ether acetate, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and hard-baked at 110°C overnight. Surface passivation of the master wafer was performed under vacuum using trichloro (1H,1H,2H,2H-perfluorooctyl) saline (PFOCTS, Sigma Aldrich). Next, a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS, ThermoFisher Scientific) pre-polymer was mixed with the curing agent at a volume ratio of 10:1 and degassed to remove any air bubbles. The mixture was then poured over the master wafer and cured at 80°C overnight. Thereafter, PDMS replicas were peeled off, cut into individual pieces, and inlet and outlet holes were punched. Excess saline was removed by sonicating in isopropanol. Finally, the PDMS replicas were covalently bonded on standard microscope glass slides using oxygen plasma to form the micro-channels.

Following tubing assembly, the MICA microchannel was rinsed with 100% ethanol and PBS, and then blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA, ProSpec-Tany TechnoGene Ltd., East Brunswick, NJ) at 4°C overnight to prevent any non-specific cell adhesion to the microchannel walls. Cytobrush samples collected from lesional and contralateral sites of each patient were placed on ice before testing. The cytobrush sample was injected into the appropriate microchannel (lesion in one; contralateral in the other) under 40 mbar inlet pressure using a Flow-EZ pressure control unit (Fluigent, Lowell, MA) until a reasonable cell density was achieved in the microchannel. Following formaldehyde (Sigma Aldrich) fixation (4% in PBS) for 15 min at room temperature (RT), the microchannel was rinsed with PBS and blocked with 1% BSA for 1 h at RT. Next, the fixed cells were permeabilized with Triton X-100 (Sigma Aldrich) (0.1% in PBS with 1% BSA) for 15 min at RT, and incubated in a mixture of 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 10 μg/mL final concentration) and hBD-3 and hBD-2 antibodies (Bioss Antibodies, Woburn, MA; Catalog: bs-7378R-A488 and bs-4307R-A647) (1% in PBS with 1% BSA) in the dark at RT for 1 h. Finally, the microchannel was washed with PBS and imaged under 10× objective with an inverted microscope (Olympus IX83) and a microscope camera (EXi Blue EXI-BLU-RF-M-14-C).

To quantify the ratio of hBD-3 to hBD-2 of each side for each patient and healthy individual, the retained cells were fluorescently labeled with an anti-hBD-3 antibody (Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated) and an anti-hBD-2 antibody (Alexa Fluor 647 conjugated). Cell nuclei were also labeled with DAPI, and used to distinguish intact cells from debris. Cells in the area of interest (AOI: micropillar arrays with 40, 30 and 20-μm openings) were imaged using 10× objective, for which representative microscopic phase-contrast and fluorescent images are shown in Figures 6A and 6B.

To determine BDI, image segmentation and fluorescence intensity analyses were carried out (Figure S7), where the average ratio of hBD-3 to hBD-2 of each side was computed based on 9 pairs of fluorescent images. Finally, the patient BDI was computed using the equation: BDI = [hBD-3 pixel/hBD-2 pixel] L/[hBD-3 pixel/hBD-2 pixel] N (L = lesional and N= Contralateral Normal)

Salivary levels of hBD-2 and hBD-3

Salivary levels of hBD-2 and -3 were determined following the protocol as described by Ghosh et al. (2007).87 Briefly, 96-well immunoplates (R&D Systems, MN) were coated with 50 μL anti-hBD-2 or hBD-3 antibodies (Peprotech, NJ) diluted to 1 μg/mL, 4°C, overnight, followed by blocking with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The wells were washed 3 times with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20. Fifty μL of each saliva sample and 50 μL of 500mM CaCl2 were added to each well and incubated at room temperature (RT) for 1 h. The wells were washed 3 times with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 and incubated with 50 μL of the biotinylated secondary antibody (Peprotech, NJ) diluted to 0.1 μg/mL, at RT, 30 min. Each well was washed 3 times, followed by 50 μL/well of streptavidin-peroxidase (R&D Systems, 1:200 in wash buffer). Each well was washed again (3 times with wash buffer) and incubated with 100ul of Reagent A and B (1:1) for 20 min, after which the reaction was stopped with a stop solution (2N HCL). Absorbance was measured at 450 nm with a microplate reader.

Quantification and statistical analysis

ROC curve was generated and cut-off value was calculated using easyROC online software.44 TCGA data were analyzed using multiple online software (GEDS,30 GEPIA232 and UALCAN31 and LinkedOmics35) as indicated in the results section. Most of the other plots were generated using GraphPad Prism version 6 and statistical calculations were carried out with either non-parametric Mann-Whitney test or Kruskal-Wallis test, as indicated in the figure legends (p value < 0.05 were considered significant).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the patients who consented to be in this study. We also wish to thank the network of dentists associated with WVU Dental School for providing samples from their respective clinics. These included: Drs. Bruce Cassis (Cassis Dental Center, WV); Johns Conde, DDS and Dr. Matthew Malone, DDS (Conde & Malone Family Dentistry, WV); Diane D. Romaine, DMD (Diane Romaine, WV); Travis Wills, DDS (Shady Spring Dental Care, WV); Sricharan Mahavadi, DDS (Sunny Smiles Family Dentistry, WV); and Thomas Leslie, DDS (Berkeley Springs, WV). We would like to thank Tempus (Chicago, IL, USA) for performing whole-exon sequencing of cytobrush samples, as well as the University of Cincinnati Center Clinical Trials Office translational team. Finally, the authors thank Dr. Steve Fening (Associate Vice President for Research, CWRU) for reading the manuscript and providing insightful comments. This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants (P01DE019759 and R21CA253108), funding from the Case-Coulter Translational Research Partnership as well as the Ohio Third Frontier Technology Validation and Star-Up Fund.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, S.K.G., A.W., and U.A.G.; methodology, S.K.G., Y.M., A.F., U.A.G., P.P., G.J., A.M., and A.W.; validation, S.K.G., C.W., and C.M.; formal analysis, S.K.G., Y.M., A.F., C.L., U.A.G., and A.W.; statistical analysis, S.K.G. and F.B.; investigation, S.K.G., Y.M., A.F., C.W., C.M., C.L., D.P., H.K., N.B., and P.P.; resources, C.C.Z., R.R., F.P., J.E.T., A.T., J.W., and H.Q.; data curation, S.K.G.; writing – original draft, S.K.G.; writing – review & editing, S.K.G., Y.M., A.F., P.P., G.J., T.W.-D., T.S.M., J.W., U.A.G., and A.W.; visualization, S.K.G.; supervision, A.W., S.K.G., U.A.G., G.J., F.P., C.Z., T.W.-D., and P.P.; funding acquisition, A.W. and U.A.G.; project administration, A.W.

Declaration of interests

S.K.G., U.A.G., and A.W. have a patent on “Epithelial cancer evaluation using beta defensin” (US10816549B2).

Published: March 4, 2024

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2024.101447.

Contributor Information

Santosh K. Ghosh, Email: skg12@case.edu.

Aaron Weinberg, Email: axw47@case.edu.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Barsouk A., Aluru J.S., Rawla P., Saginala K., Barsouk A. Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Prevention of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Med. Sci. 2023;11 doi: 10.3390/medsci11020042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., Laversanne M., Soerjomataram I., Jemal A., Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferlay J., Shin H.R., Bray F., Forman D., Mathers C., Parkin D.M. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int. J. Cancer. 2010;127:2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siegel R., Ma J., Zou Z., Jemal A. Cancer statistics. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jemal A., Bray F., Center M.M., Ferlay J., Ward E., Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Head and Neck Cancer Statistics. http://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/head-and-neck-cancer/statistics).

- 7.Vigneswaran N., Williams M.D. Epidemiologic trends in head and neck cancer and aids in diagnosis. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. 2014;26:123–141. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheong S.C., Chandramouli G.V.R., Saleh A., Zain R.B., Lau S.H., Sivakumaren S., Pathmanathan R., Prime S.S., Teo S.H., Patel V., Gutkind J.S. Gene expression in human oral squamous cell carcinoma is influenced by risk factor exposure. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:712–719. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ko Y.C., Huang Y.L., Lee C.H., Chen M.J., Lin L.M., Tsai C.C. Betel quid chewing, cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption related to oral cancer in Taiwan. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 1995;24:450–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1995.tb01132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liao C.T., Wallace C.G., Lee L.Y., Hsueh C., Lin C.Y., Fan K.H., Wang H.M., Ng S.H., Lin C.H., Tsao C.K., et al. Clinical evidence of field cancerization in patients with oral cavity cancer in a betel quid chewing area. Oral Oncol. 2014;50:721–731. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krishnan L., Karpagaselvi K., Kumarswamy J., Sudheendra U.S., Santosh K.V., Patil A. Inter- and intra-observer variability in three grading systems for oral epithelial dysplasia. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 2016;20:261–268. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.185928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kujan O., Khattab A., Oliver R.J., Roberts S.A., Thakker N., Sloan P. Why oral histopathology suffers inter-observer variability on grading oral epithelial dysplasia: an attempt to understand the sources of variation. Oral Oncol. 2007;43:224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Speight P.M., Abram T.J., Floriano P.N., James R., Vick J., Thornhill M.H., Murdoch C., Freeman C., Hegarty A.M., D'Apice K., et al. Interobserver agreement in dysplasia grading: toward an enhanced gold standard for clinical pathology trials. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2015;120:474–482.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2015.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Upadhyaya J.D., Fitzpatrick S.G., Cohen D.M., Bilodeau E.A., Bhattacharyya I., Lewis J.S., Jr., Lai J., Wright J.M., Bishop J.A., Leon M.E., et al. Inter-observer Variability in the Diagnosis of Proliferative Verrucous Leukoplakia: Clinical Implications for Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon Understanding: A Collaborative Pilot Study. Head Neck Pathol. 2020;14:156–165. doi: 10.1007/s12105-019-01035-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu W., Shi L.J., Wu L., Feng J.Q., Yang X., Li J., Zhou Z.T., Zhang C.P. Oral cancer development in patients with leukoplakia--clinicopathological factors affecting outcome. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silverman S., Jr., Gorsky M., Lozada F. Oral leukoplakia and malignant transformation. A follow-up study of 257 patients. Cancer. 1984;53:563–568. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840201)53:3<563::aid-cncr2820530332>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Funk G.F., Karnell L.H., Robinson R.A., Zhen W.K., Trask D.K., Hoffman H.T. Presentation, treatment, and outcome of oral cavity cancer: a National Cancer Data Base report. Head Neck. 2002;24:165–180. doi: 10.1002/hed.10004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klotman M.E., Chang T.L. Defensins in innate antiviral immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2006;6:447–456. doi: 10.1038/nri1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin B., Li R., Handley T.N.G., Wade J.D., Li W., O'Brien-Simpson N.M. Cationic Antimicrobial Peptides Are Leading the Way to Combat Oropathogenic Infections. ACS Infect. Dis. 2021;7:2959–2970. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.1c00424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mangoni M.L., McDermott A.M., Zasloff M. Antimicrobial peptides and wound healing: biological and therapeutic considerations. Exp. Dermatol. 2016;25:167–173. doi: 10.1111/exd.12929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steinstraesser L., Koehler T., Jacobsen F., Daigeler A., Goertz O., Langer S., Kesting M., Steinau H., Eriksson E., Hirsch T. Host defense peptides in wound healing. Mol. Med. 2008;14:528–537. doi: 10.2119/2008-00002.Steinstraesser. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takahashi M., Umehara Y., Yue H., Trujillo-Paez J.V., Peng G., Nguyen H.L.T., Ikutama R., Okumura K., Ogawa H., Ikeda S., Niyonsaba F. The Antimicrobial Peptide Human β-Defensin-3 Accelerates Wound Healing by Promoting Angiogenesis, Cell Migration, and Proliferation Through the FGFR/JAK2/STAT3 Signaling Pathway. Front. Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.712781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawsar H.I., Weinberg A., Hirsch S.A., Venizelos A., Howell S., Jiang B., Jin G. Overexpression of human beta-defensin-3 in oral dysplasia: potential role in macrophage trafficking. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:696–702. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DasGupta T., Nweze E.I., Yue H., Wang L., Jin J., Ghosh S.K., Kawsar H.I., Zender C., Androphy E.J., Weinberg A., et al. Human papillomavirus oncogenic E6 protein regulates human β-defensin 3 (hBD3) expression via the tumor suppressor protein p53. Oncotarget. 2016;7:27430–27444. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jin G., Kawsar H.I., Hirsch S.A., Zeng C., Jia X., Feng Z., Ghosh S.K., Zheng Q.Y., Zhou A., McIntyre T.M., Weinberg A. An antimicrobial peptide regulates tumor-associated macrophage trafficking via the chemokine receptor CCR2, a model for tumorigenesis. PLoS One. 2010;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feng Y., Ye Z., Song F., He Y., Liu J. The Role of TAMs in Tumor Microenvironment and New Research Progress. Stem Cell. Int. 2022;2022 doi: 10.1155/2022/5775696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]