Abstract

Background

Medically unexplained physical symptoms (MUPS) are physical symptoms for which no adequate medical explanation can be found after proper examination. The presence of MUPS is the key feature of conditions known as 'somatoform disorders'. Various psychological and physical therapies have been developed to treat somatoform disorders and MUPS. Although there are several reviews on non‐pharmacological interventions for somatoform disorders and MUPS, a complete overview of the whole spectrum is missing.

Objectives

To assess the effects of non‐pharmacological interventions for somatoform disorders (specifically somatisation disorder, undifferentiated somatoform disorder, somatoform disorders unspecified, somatoform autonomic dysfunction, pain disorder, and alternative somatoform diagnoses proposed in the literature) and MUPS in adults, in comparison with treatment as usual, waiting list controls, attention placebo, psychological placebo, enhanced or structured care, and other psychological or physical therapies.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Review Group's Specialised Register (CCDANCTR) to November 2013. This register includes relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs) from The Cochrane Library, EMBASE, MEDLINE, and PsycINFO. We ran an additional search on the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and a cited reference search on the Web of Science. We also searched grey literature, conference proceedings, international trial registers, and relevant systematic reviews.

Selection criteria

We included RCTs and cluster randomised controlled trials which involved adults primarily diagnosed with a somatoform disorder or an alternative diagnostic concept of MUPS, who were assigned to a non‐pharmacological intervention compared with usual care, waiting list controls, attention or psychological placebo, enhanced care, or another psychological or physical therapy intervention, alone or in combination.

Data collection and analysis

Four review authors, working in pairs, conducted data extraction and assessment of risk of bias. We resolved disagreements through discussion or consultation with another review author. We pooled data from studies addressing the same comparison using standardised mean differences (SMD) or risk ratios (RR) and a random‐effects model. Primary outcomes were severity of somatic symptoms and acceptability of treatment.

Main results

We included 21 studies with 2658 randomised participants. All studies assessed the effectiveness of some form of psychological therapy. We found no studies that included physical therapy.

Fourteen studies evaluated forms of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT); the remainder evaluated behaviour therapies, third‐wave CBT (mindfulness), psychodynamic therapies, and integrative therapy. Fifteen included studies compared the studied psychological therapy with usual care or a waiting list. Five studies compared the intervention to enhanced or structured care. Only one study compared cognitive behavioural therapy with behaviour therapy.

Across the 21 studies, the mean number of sessions ranged from one to 13, over a period of one day to nine months. Duration of follow‐up varied between two weeks and 24 months. Participants were recruited from various healthcare settings and the open population. Duration of symptoms, reported by nine studies, was at least several years, suggesting most participants had chronic symptoms at baseline.

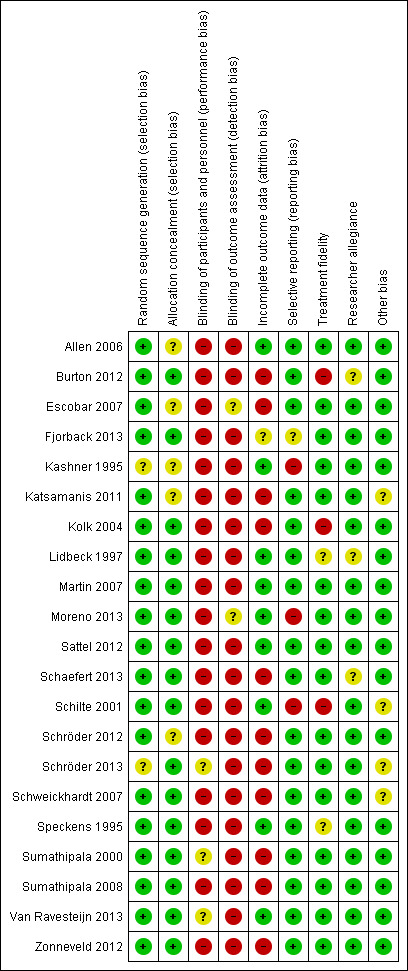

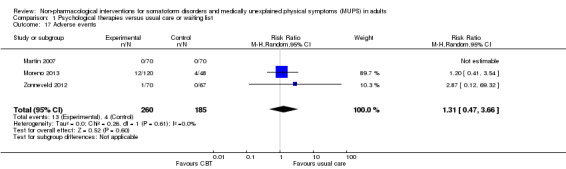

Due to the nature of the intervention, lack of blinding of participants, therapists, and outcome assessors resulted in a high risk of bias on these items for most studies. Eleven studies (52% of studies) reported a loss to follow‐up of more than 20%. For other items, most studies were at low risk of bias. Adverse events were seldom reported.

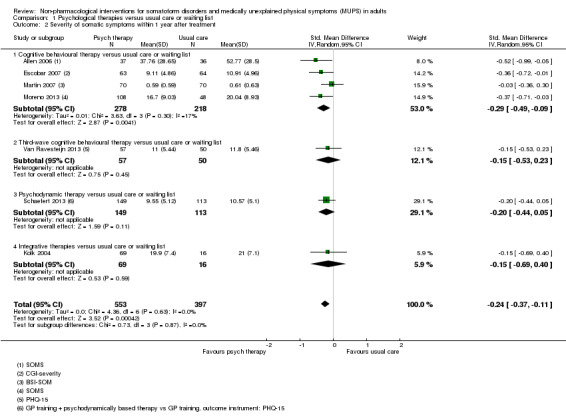

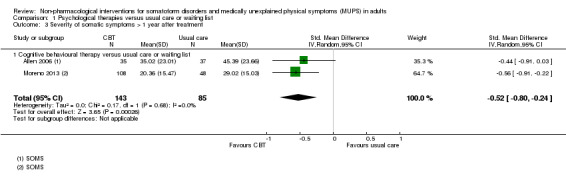

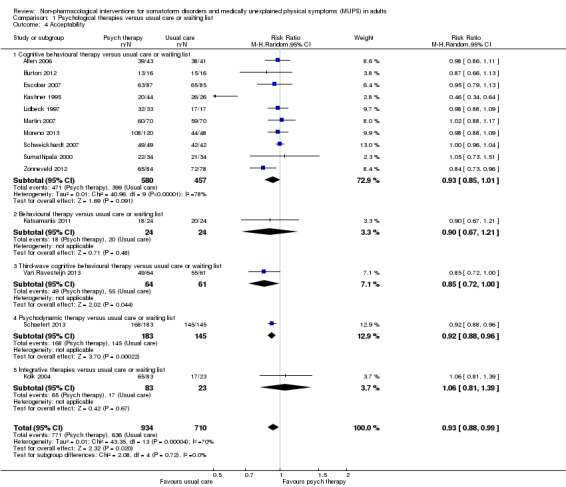

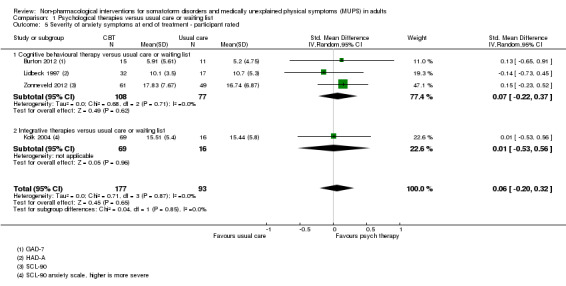

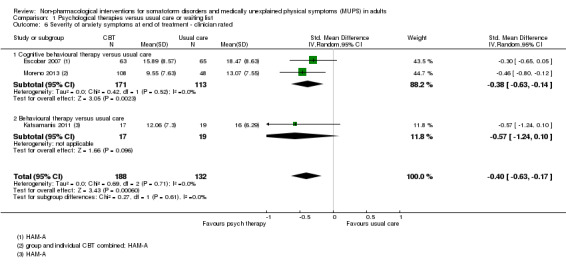

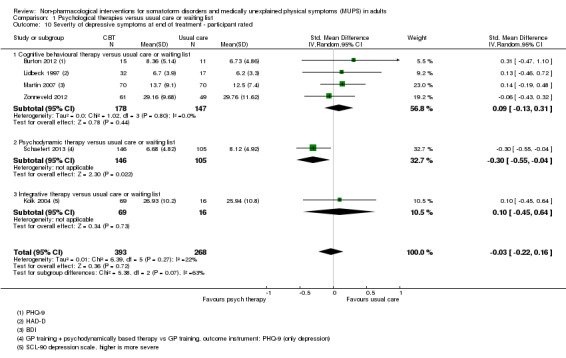

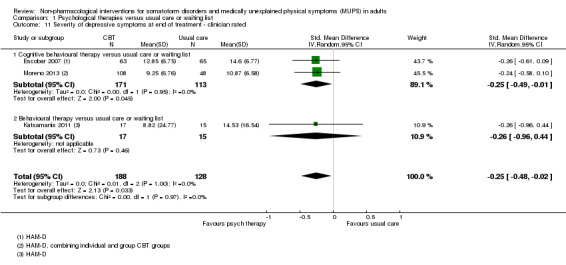

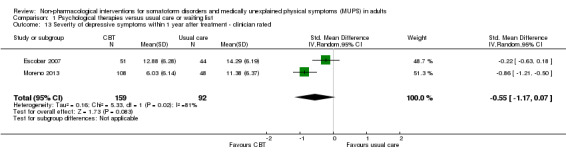

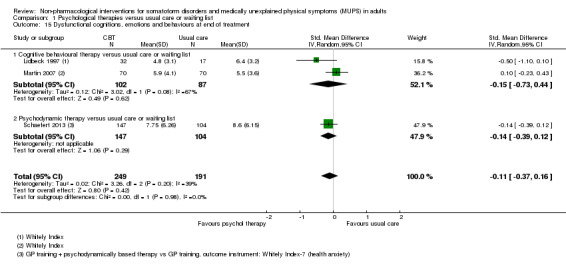

For all studies comparing some form of psychological therapy with usual care or a waiting list that could be included in the meta‐analysis, the psychological therapy resulted in less severe symptoms at end of treatment (SMD ‐0.34; 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.53 to ‐0.16; 10 studies, 1081 analysed participants). This effect was considered small to medium; heterogeneity was moderate and overall quality of the evidence was low. Compared with usual care, psychological therapies resulted in a 7% higher proportion of drop‐outs during treatment (RR acceptability 0.93; 95% CI 0.88 to 0.99; 14 studies, 1644 participants; moderate‐quality evidence). Removing one outlier study reduced the difference to 5%. Results for the subgroup of studies comparing CBT with usual care were similar to those in the whole group.

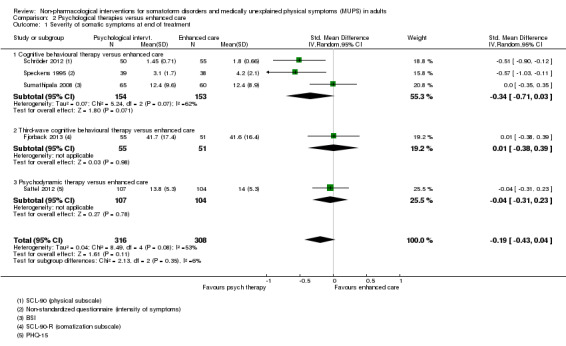

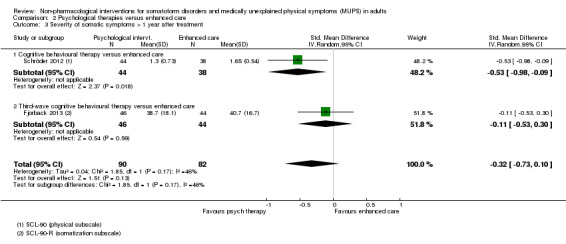

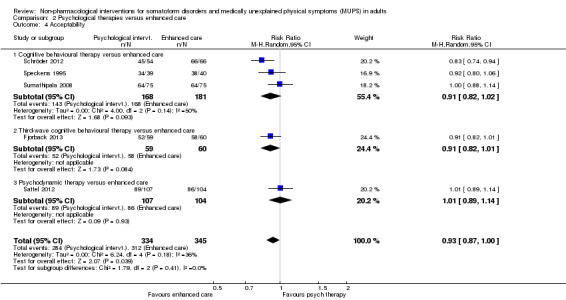

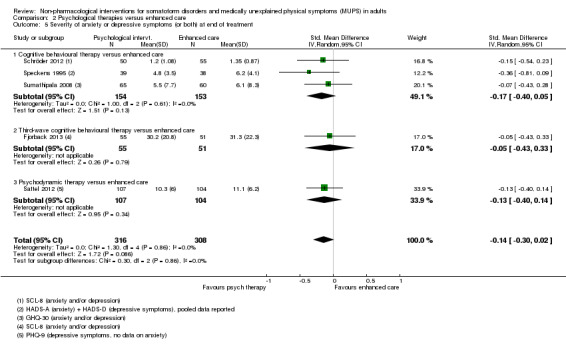

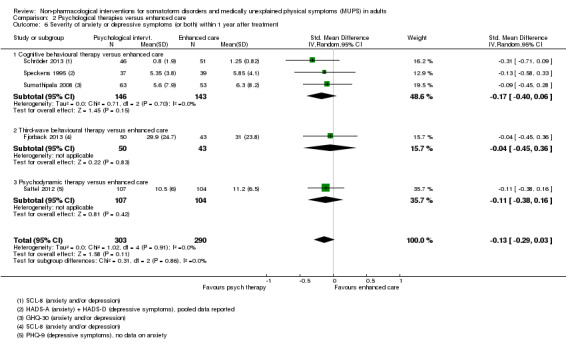

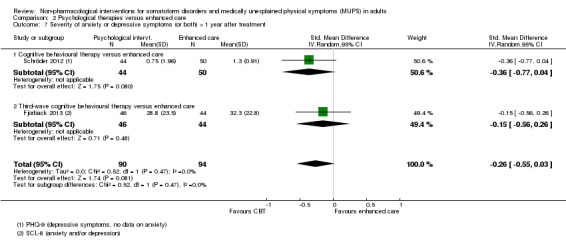

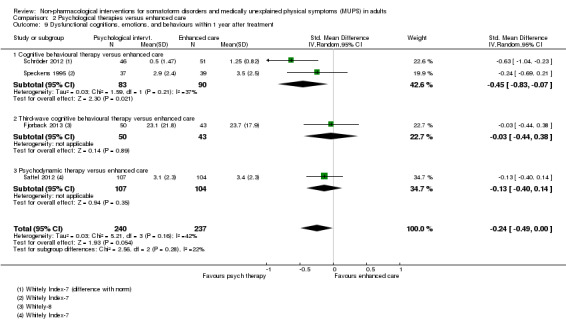

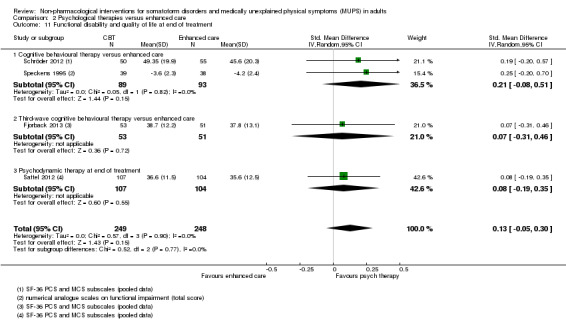

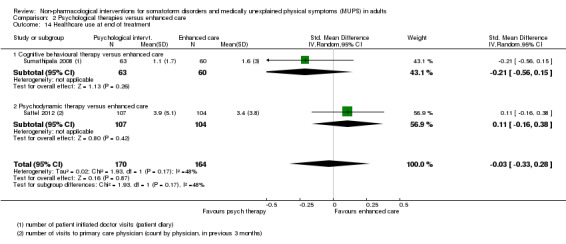

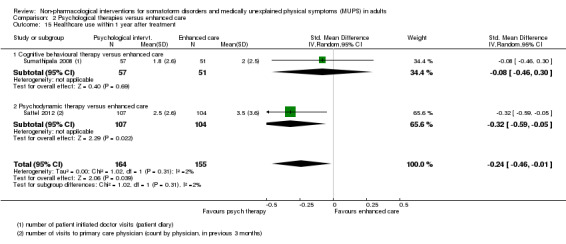

Five studies (624 analysed participants) assessed symptom severity comparing some psychological therapy with enhanced care, and found no clear evidence of a difference at end of treatment (pooled SMD ‐0.19; 95% CI ‐0.43 to 0.04; considerable heterogeneity; low‐quality evidence). Five studies (679 participants) showed that psychological therapies were somewhat less acceptable in terms of drop‐outs than enhanced care (RR 0.93; 95% CI 0.87 to 1.00; moderate‐quality evidence).

Authors' conclusions

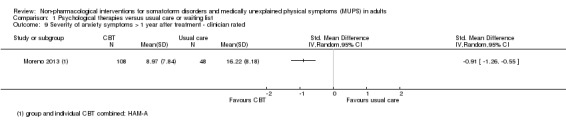

When all psychological therapies included this review were combined they were superior to usual care or waiting list in terms of reduction of symptom severity, but effect sizes were small. As a single treatment, only CBT has been adequately studied to allow tentative conclusions for practice to be drawn. Compared with usual care or waiting list conditions, CBT reduced somatic symptoms, with a small effect and substantial differences in effects between CBT studies. The effects were durable within and after one year of follow‐up. Compared with enhanced or structured care, psychological therapies generally were not more effective for most of the outcomes. Compared with enhanced care, CBT was not more effective. The overall quality of evidence contributing to this review was rated low to moderate.

The intervention groups reported no major harms. However, as most studies did not describe adverse events as an explicit outcome measure, this result has to be interpreted with caution.

An important issue was that all studies in this review included participants who were willing to receive psychological treatment. In daily practice, there is also a substantial proportion of participants not willing to accept psychological treatments for somatoform disorders or MUPS. It is unclear how large this group is and how this influences the relevance of CBT in clinical practice.

The number of studies investigating various treatment modalities (other than CBT) needs to be increased; this is especially relevant for studies concerning physical therapies. Future studies should include participants from a variety of age groups; they should also make efforts to blind outcome assessors and to conduct follow‐up assessments until at least one year after the end of treatment.

Keywords: Adult, Humans, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Psychotherapy, Psychotherapy/methods, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Somatoform Disorders, Somatoform Disorders/therapy, Waiting Lists

Plain language summary

Talking therapies and physical therapies for medically unexplained physical symptoms: a review of the evidence

Who may be interested in this review?

People with unexplained physical symptoms (somatoform disorders) and their family and friends.

Professionals working with people with somatoform disorders or working in chronic pain services.

General practitioners.

Why is this review important?

Up to one in three people consulting their doctor about physical symptoms have medically unexplained physical symptoms (MUPS) that have no clear cause. MUPS are a key feature of health problems called somatoform disorders. MUPS and somatoform disorders often cause significant distress and cause people spending a lot of time consulting doctors and health professionals to try to find the cause of their symptoms and the correct treatment.

Talking therapies for MUPS are recommended to help with mental health problems that exist alongside the physical symptoms, and to help people change the way they think about their physical symptoms. Physical therapies for MUPS aim to help people improve their physical functioning through various types of exercise. This review aimed to examine the evidence for talking therapies and physical therapies for MUPS and somatoform disorders.

What questions does this review aim to answer?

What is the quality of current research on talking therapies and physical therapies for MUPS?

Are talking therapies an effective treatment for MUPS compared with usual treatment or waiting list?

Which types of talking therapies are most effective?

Are physical therapies an effective treatment for MUPS?

How acceptable are talking therapies and physical therapies to people with MUPS?

Which studies were included in the review?

We used search databases to find all studies of talking therapies and physical therapies for people with somatoform disorders published to November 2013. To be included in the review, studies had to compare talking therapies or physical therapies with either usual treatment, waiting list, enhanced or structured care (where a doctor offered structured appointments to the person but no specific therapy for MUPS), or other talking or physical therapies. We included studies if they had adults aged over 18 years with a clear diagnosis of somatoform disorders or main presenting problem of MUPS.

We included 21 studies in the review with 2658 participants.

What does the evidence from the review tell us?

We rated the quality of current research as low to moderate. Fourteen out of the 21 studies focused on cognitive behavioural therapy, which is a specific form of talking therapy based on the idea that thoughts and thinking can influence emotions and behaviours.

Cognitive behavioural therapy was more effective than usual care in reducing the severity of MUPS. For other types of therapy, we found only one or two studies giving insufficient evidence for conclusions.

Cognitive behavioural therapy was no more effective than enhanced care provided by the person's doctor.

No studies of physical therapy met the criteria to be included in the review.

Talking therapies were acceptable to people and few people dropped out of the trials; however, this may not reflect real clinical practice as the study participants were people with somatoform disorders or MUPS who were willing to try talking therapies. In clinical practice, a high proportion of people may not be willing to accept these treatments.

What should happen next?

The review authors suggest that future high‐quality trials should be carried out to find out more about which groups of people benefit most from cognitive behavioural therapy and how it can be most effectively delivered. They also suggest that more studies are needed of other talking therapies, and a particular focus should be on high‐quality studies of physical therapies.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Psychological therapy compared with usual care or waiting list for somatoform disorders and medically unexplained physical symptoms.

| Psychological therapy compared with usual care for somatoform disorders and medically unexplained physical symptoms | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with somatoform disorders and medically unexplained physical symptoms Settings: all settings Intervention: psychological therapy Comparison: usual care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Usual care | Psychological therapy | |||||

| Severity of somatic symptoms at end of treatment Various instruments | The mean severity of somatic symptoms at end of treatment ranged across control groups from 0.5 to 48.71 using varying scales1 | The mean severity of somatic symptoms at end of treatment in the intervention groups was 0.34 standard deviations lower (0.53 to 0.16 lower) | ‐ | 1081 (10 studies2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,4,5 | A difference of 0.34 SMD was considered to be 'small to medium' |

| Acceptability 1 ‐ proportion of participants withdrawing during treatment | 896 per 1000 | 833 per 1000 (788 to 887) | RR 0.93 (0.88 to 0.99) | 1644 (14 studies6) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate7,8 | Excluding the outlier (see footnote) (70 participants) reduced I2 statistic from 70% to 33% |

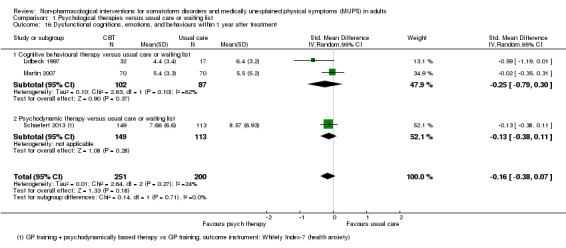

| Dysfunctional cognitions, emotions, or behaviours (participant rated) at end of treatment Whitely Index | The mean dysfunctional cognitions, emotions, or behaviours (participant rated) at end of treatment in the control groups was 7.3 on the Whitely Index | The mean dysfunctional cognitions, emotions, or behaviours (participant rated) at end of treatment in the intervention groups was 0.11 standard deviations lower (0.37 lower to 0.16 higher) | ‐ | 440 (3 studies9) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate10 | A difference of 0.11 SMD was considered to be 'small' |

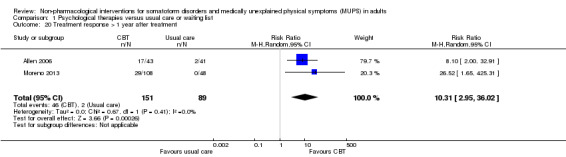

| Treatment response at end of treatment CGI‐improvement/Global impression of change | 157 per 1000 | 517 per 1000 (326 to 816) | RR 3.30 (2.08 to 5.21) | 391 (4 studies11) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low12,13 | ‐ |

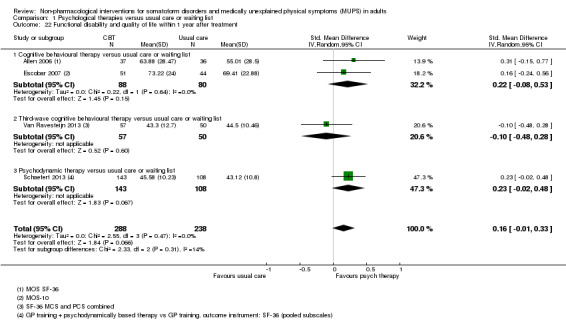

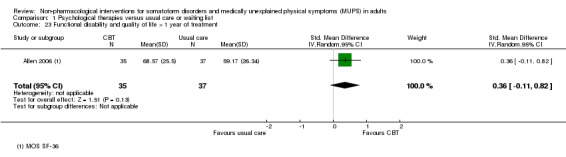

| Functional disability/quality of life at end of treatment Various instruments | ‐ | The mean functional disability/quality of life at end of treatment in the intervention groups was 0.17 standard deviations higher (0.03 to 0.32 higher) | ‐ | 730 (7 studies14) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,13 | A difference of 0.17 SMD was considered to be small |

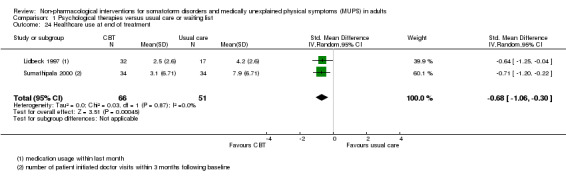

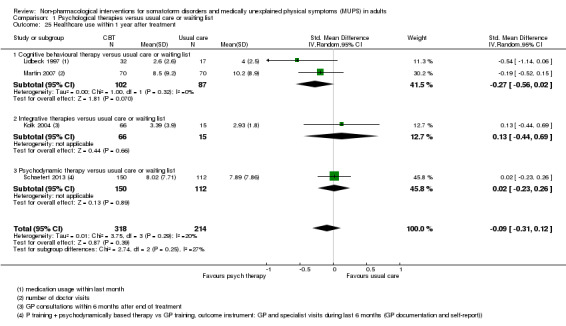

| Healthcare use Various measures, participant or physician assessed < 1 year after end of treatment Follow‐up: 6‐11 months | ‐ | The mean healthcare use in the intervention groups was 0.09 standard deviations lower (0.31 lower to 0.12 higher) | ‐ | 532 (4 studies15) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate12 | Difference small and not statistically significant |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CGI: Clinical Global Impression; CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Measured with different instruments using different scales. 2 Analysis 1.1. 3 Quality of evidence downgraded one point for each of the following study limitations (present in most studies): lack of blinding and incomplete outcome data (loss to follow up) 4 I2 = 49%. 5 95% CI crossed effect size of 0.5. 6 Analysis 1.4. 7 Quality downgraded by one point as studies not blinded. As acceptability and loss to follow‐up are interrelated, we decided not to downgrade the evidence for loss to follow‐up. 8 I2 = 70%. One outlier explained most of the heterogeneity (Kashner 1995). 9 Analysis 1.15. 10 Due to lack of blinding in all studies and loss to follow‐up in one study. 11 Analysis 1.18. 12 Due to lack of blinding in all studies and loss to follow‐up > 20% in 2 studies. 13 < 300 events. 14 Analysis 1.21. 15 Analysis 1.25.

Summary of findings 2. Psychological therapy compared with enhanced or structured care for somatoform disorders and medically unexplained physical symptoms.

| Patient or population: somatoform disorders and medically unexplained physical symptoms Settings: all settings Intervention: psychological therapies Comparison: enhanced or structured care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Enhanced or structured care | Psychological therapies | |||||

| Severity of somatic symptoms at end of treatment | ‐ | The mean severity of somatic symptoms at end of treatment in the intervention groups was 0.19 standard deviations lower (0.43 lower to 0.04 higher) | ‐ | 624 (5 studies1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ low2, 11 | 95% CI excluded large effect (> 0.5 SMD) |

| Acceptability 1 ‐ proportion of participants withdrawing during treatment | 904 per 1000 | 841 per 1000 (787 to 904) | RR 0.93 (0.87 to 1) | 679 (5 studies3) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 | ‐ |

| Dysfunctional cognitions, emotions, or behaviours at end of treatment Whitely Index (different forms) | ‐ | The mean dysfunctional cognitions, emotions, or behaviours at end of treatment in the intervention groups was 0.09 standard deviations lower (0.29 lower to 0.1 higher) | ‐ | 499 (4 studies5) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate6 | 95% CI excluded clinically relevant effect |

| Treatment response at end of treatment | Study population | Not estimable | 0 (0) | See comment | No studies reported on this outcome (see text) | |

| See comment | See comment | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| ‐ | ‐ | |||||

| Functional disability/quality of life at end of treatment Various instruments | ‐ | The mean functional disability/quality of life at end of treatment in the intervention groups was 0.13 standard deviations higher (0.05 lower to 0.3 higher) | ‐ | 497 (4 studies7) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate6 | 95% CI excluded clinically relevant effect |

| Healthcare use within 1 year after treatment | ‐ | The mean healthcare use within 1 year after treatment in the intervention groups was 0.24 standard deviations lower (0.46 to 0.01 lower) | ‐ | 319 (2 studies8) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low9,10 | ‐ |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Analysis 2.1. 2 I2 = 53% 3 Analysis 2.4. 4 Quality of evidence downgraded by one point as studies not blinded. As acceptability and loss to follow‐up are interrelated, we decided not to downgrade the evidence for loss to follow‐up. 5 Analysis 2.8. 6 Assessment of quality of evidence downgraded by one point as studies were not blinded. 7 Analysis 2.11. 8 Analysis 2.15. 9 In addition to both studies not being blinded, high loss to follow‐up in one study. We therefore downgraded our assessment of the quality of the evidence by two points. 10 Only 2 studies with < 400 analysed participants.

11 No blinding (all studies) and >20% loss to follow up (2 studies)

Background

Description of the condition

Medically unexplained physical symptoms (MUPS) are physical symptoms for which adequate evidence of an underlying pathophysiological process cannot be identified after appropriate examination and investigation. MUPS are common in all healthcare settings. Up to one‐third of all people presenting with physical symptoms have MUPS (Kirmayer 2004). The presence of MUPS is the key feature of conditions known as somatoform disorders. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM; APA 2000) and International Classification of Diseases (ICD; WHO 2004) describe four somatoform diagnostic categories that include MUPS as their main indication. These categories are: somatisation disorder, (persistent somatoform) pain disorder, undifferentiated somatoform disorder, and unspecified somatoform disorder. The ICD also describes a fifth category: somatoform autonomic dysfunction disorder. All these disorders are established through a validated psychiatric diagnostic interview. Many different diagnostic revisions of somatoform disorders have been suggested and used in research since the early 2000s. Examples of proposed revised diagnoses include abridged somatisation disorder (Escobar 1998), multisomatoform disorder (Kroenke 1997), bodily distress disorder (Fink 2007), and complex somatic symptom disorder (Dimsdale 2009). These alternative diagnoses have their own diagnostic criteria, mainly based on symptom counts. Finally, in some fields, MUPS are not described as a feature of a specific disorder, but as a health problem in their own right. As a result, the treatment of MUPS in general is also described in literature, for example, in primary care research. Assessing the presence of MUPS is usually based on the combination of a validated somatic symptom scale, the duration of symptoms, and clinical judgement by the physician.

In some health care settings the term 'somatoform' is falling out of favour, as people can find this term offensive. In these settings the term is being replaced with other terms such as 'functional'.

Somatoform disorders and MUPS may lead to functional impairment, high levels of psychological distress, a reduced quality of life, and a troubled doctor‐patient relationship (Escobar 1987; Gureje 1997; Ring 2004; Zoccolillo 1986). Furthermore, chronic MUPS may lead to absence from work, fragmented and high utilisation of health care, and the associated high costs for society (Konnopka 2012; Kroenke 1989; Smith 1986).

DSM 5 describes the 'somatic symptom disorder' (SSD), which requires explicit cognitive criteria (e.g. excessive and disproportionate thoughts, feelings, and behaviours regarding symptoms) (APA 2013). The diagnosis does not require the somatic symptoms to be medically unexplained.

Description of the intervention

In previous decades, many pharmacological and non‐pharmacological interventions for somatoform disorders and MUPS were developed. The use of antidepressants, in particular, as pharmacological agents for syndromes of MUPS (Ford 2009; Pae 2009), or chronic pain (Saarto 2007), was tested. The most relevant groups of antidepressants are the tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and selective serotonin and noradrenaline (norepinephrine) reuptake inhibitors. In addition to antidepressants, antiepileptic drugs are also commonly used for somatoform disorders (Moore 2014; Silberstein 2002), although they are not advised in guidelines. Pharmacological interventions will be described in a separate forthcoming Cochrane review (published protocol: Kleinstäuber 2013) and this review only focuses on non‐pharmacological interventions.

Most non‐pharmacological interventions for MUPS focus on addressing cognitions, behaviour, coping styles, and functional consequences of symptoms. These interventions include psychological therapies as well as physical therapies. Psychological therapies are mostly used to tackle underlying psychological disorders and problems, and aim to change the way that people perceive their symptoms in order to help them to manage their symptoms. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) appears to be a promising treatment in this category, if people accept the treatment (Kroenke 2000). Physical therapies usually concern physical activity treatments, which aim to improve physical function by expanding physical activity and thereby reducing symptoms. In the paragraph below, we described examples of several frequently studied forms of psychological and physical therapies.

How the intervention might work

Psychological therapies ‐ cognitive behavioural therapy

The first and most commonly used and investigated psychological therapy for MUPS is CBT, which is based on the cognitive behavioural model (Deary 2007). This model proposes that MUPS are caused by a self perpetuating multi‐factorial cycle, based on the interaction of different factors in several domains, including somatic (physical) aspects, cognitions (thoughts), behaviour, emotions, and environment (Sharpe 1992). This model provides a framework to incorporate people's personal predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating factors according to their symptoms. CBT, as a consequence, focuses on addressing or changing cognitions and behaviours that people have in interaction with their symptoms.

Reattribution is a specific form of CBT (Goldberg 1989). This method aims to encourage people to reattribute their MUPS to physiological or psychosocial causes rather than to somatic causes. Reattribution consists of three stages: 1. making the person feel understood; 2. changing the agenda of the person, and the doctor, and their mutual agenda during the consultations; and 3. making the link between physical symptoms and psychosocial problems.

This self propagating disadvantageous situation is illustrated by the case of a person with low back pain who moves less freely and more stiffly because of the pain; this, in turn, causes the low back pain to continue and possibly worsen, and creates more stress. Reattribution might focus on making the person realise that stress caused by work may be responsible for causing or perpetuating the low back pain.

Problem‐solving treatment is another form of CBT that has been used for people with MUPS and somatoform disorders. The aim is to reduce complaints associated with unresolved problems in daily life by enhancing a person's problem‐solving capacities in a step‐by‐step manner. This therapy has a positive effect on mental and physical health problems in general (Malouff 2007).

Psychological therapies ‐ behavioural therapy

Behavioural therapy, the second group, aims to constructively change a person's behaviour towards their symptoms using operant conditioning ‐ also known as instrumental conditioning ‐ in which a response in a certain context is followed by a reinforcing stimulus or consequence, thereby increasing the likelihood that the same response will follow in future. Biofeedback therapy is an important behavioural intervention relevant to this review. In this therapy, one or more physiological measures (such as heart rate, respiratory rate, or muscle tension) are thought to relate to the person's physical symptoms, and people are taught to control these measures voluntarily. As a result, they develop a personal strategy for controlling them (Nanke 2003b; Schwartz 2003). Other forms of behavioural therapy include relaxation therapy (Loew 2000), and psycho‐education (Guerney 1971).

Other psychological therapies

A third group of psychological therapies, more aimed at increasing insight, such as:

third‐wave cognitive behavioural therapy (i.e. the development of a new attitude towards symptoms, based on self regulation of attention and acceptance) (van Ravensteijn 2013);

psychodynamic therapies, a form of depth psychology, which focusses on revealing the unconscious content of a person's psyche in order to alleviate psychological of physical tension (Noyes 2008). This might include group therapy, in which people regularly come together to discuss their symptoms, supervised by a trained group leader. The therapy aims to stimulate an active search for causes and perpetuating factors of symptoms, and to treat them by remedial education aiming at insight;

humanistic therapies, focusing on self development, growth, and responsibilities. Treatment aims to help individuals recognise their strengths, creativity, and choices in the 'here and now'. An example is person‐centred therapy, which specifically focusses on an individual's self esteem and values; and

integrative therapies, which integrate components from several theoretical schools, e.g. cognitive analytical therapy, which aims to work with the person to identify procedural sequences, chains of events, thoughts and emotions that explain how a target problem (e.g. a physical symptom) is established and maintained, and other psychodynamic therapies (Noyes 2008).

Enhanced care

Another group of therapies offered to people with MUPS is enhanced care. Within these therapies people receive care as usual (mostly by their general practitioners (GP)), enhanced with, for example, participant education, structured counselling moments, a psychiatric interview, or a reattribution training of the doctor (Rosendal 2013). Within these therapies, there is no specific treatment agenda or structure, the aim is to offer the person some tools to assist in the recovery process, stimulating self management. This category of treatment was not mentioned in the protocol for this current review, but added post‐hoc when we found that it had been used as a comparator in several studies.

Physical therapies ‐ physical activity training

Several studies have indicated that mental health, including mood, pain thresholds, and sleep, can be improved by low‐ or moderate‐intensity activity (Weyerer 1994). Graded activity training is an operant‐conditioning behavioural approach in which physical activity is expanded step by step, based on a predetermined time schedule. It focusses on changing the fear‐avoidance behaviour that people with MUPS may have for particular physical activities (Lindström 1992). Supervised aerobic exercise training has beneficial effects on the physical capacity and symptoms of people with fibromyalgia (Busch 2007). A similar effect was found for graded activity training in people with chronic fatigue syndrome (Edmonds 2004;Yancey 2012). In non‐specific low back pain, exercise appeared to be slightly effective at decreasing pain and improving function (Hayden 2005). However, for graded activity the evidence is lacking (Van der Giessen 2012).

Other physical therapies

Other examples of physical therapies for somatoform disorders and MUPS include activation therapy, where physical and behavioural activation is increased in a step‐wise fashion, and running therapy, where running is used therapeutically, mainly to influence the level of stress.

Why it is important to do this review

Although there are several reviews on non‐pharmacological interventions for somatoform disorders and MUPS, a complete overview of the whole spectrum is missing. Some reviews did not include a meta‐analysis (Edwards 2010; Sumathipala 2007), while other reviews included only specific treatment types (Kroenke 2000; Nezu 2001), or applied restrictions on diagnostic types of MUPS or on treatment setting (Allen 2002; Edwards 2010; Kleinstäuber 2011; Rosendal 2013). Furthermore, currently there are no reviews that evaluate variations in treatment effects on the basis of diagnosis and severity of symptoms at baseline, setting, or healthcare provider.

In this review, we aimed to give an overview of the evidence for non‐pharmacological interventions for somatoform disorders and MUPS. This will help healthcare providers and patients to make optimal treatment decisions. In addition, the results of this review will provide insight into gaps in the evidence that merit future research. This review will complement the existing portfolio of four Cochrane reviews covering somatoform disorders (Hoedeman 2010; Ipser 2009; Ruddy 2005; Thompson 2007), and also the Cochrane review on pharmacological interventions for somatoform disorders, which is currently being developed (see Kleinstäuber 2013 for protocol).

Objectives

To assess the effects of non‐pharmacological interventions for somatoform disorders (specifically somatisation disorder, undifferentiated somatoform disorder, somatoform disorder unspecified, somatoform autonomic dysfunction, pain disorder, and alternative somatoform diagnoses proposed in the literature) and MUPS in adults in comparison with treatment as usual, waiting list controls, attention placebo, psychological placebo, enhanced or structured care, and other psychological or physical therapies.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and cluster randomised controlled trials (CRCTs). We also planned to include data from the first phase of cross‐over trials, but we identified no such trials that met our inclusion criteria.

We excluded quasi‐randomised trials (e.g. allocation to the study group by day of the week).

Types of participants

Participant characteristics

Participants had to be at least 18 years old. We applied no maximum age, as the condition can be present at any age. We placed no restriction on gender or culture.

Diagnosis

Participants had to meet the criteria for a somatoform disorder according to DSM III (APA 1980), DSM IV‐TR (APA 2000), ICD‐9 (WHO 1975), or ICD‐10 (WHO 2004), or the criteria for one of the alternative somatoform diagnoses proposed in the literature. The primary diagnosis (a somatoform disorder) had to be made on the basis of a structured clinical interview such as the Structured Clinical Interview for Mental Disorders (SCID; First 2002; Spitzer 1990), the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI; WHO 1990), the MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview Plus (Mini‐Plus; Sheehan 1998), or diagnostic checklists such as the International Diagnostic Checklists (IDCL; Janca 1996). The secondary diagnosis of an alternative somatoform diagnosis needed to be based on the criteria that characterise that specific disorder, for example, abridged somatisation disorder needed to be established through use of the Somatic Symptom Index (SSI; Escobar 1998).

Participants were characterised with MUPS as their primary problem, on the basis of a validated scale for the assessment of MUPS, such as the Screening for Somatoform Disorders (Screening für Somatoforme Störungen) (SOMS; Rief 1997), the Bradford Somatic Inventory (Mumford 1991), or component subscales of validated standardised instruments for the assessment of general psychopathology or general health status, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire‐15 (PHQ‐15; Kroenke 2002), the subscale 'Somatisation' of the Four Dimensional Symptom Questionnaire (4DSQ; Terluin 2006), the subscale 'Somatisation' of the Symptom Checklist‐90‐R (SCL‐90R; Derogatis 1986), or the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Derogatis 1983).

As the subdivision of these two diagnostic concepts (somatoform disorders and MUPS) is based on differences in selection methods used in different research settings rather than on differences between individual people, it is possible that the nature and severity of symptoms may show a certain overlap between the two groups.

We disregarded the DSM‐5 criteria for somatoform disorders for this version of the review. In the DSM‐5, one category, the SSD, replaced the four diagnostic categories of the somatoform disorders (APA 2013). This disorder was diagnosed on the basis of explicit psychological criteria (e.g. excessive and disproportionate thoughts, feelings, and behaviours regarding symptoms), and diagnosis did not require the somatic symptoms to be medically unexplained. However, as the publication of the DSM‐5 was recent, there are currently no instruments available to establish the diagnosis. As a result, to our knowledge, no trials have been performed that use these criteria. We will add the SSD diagnosis to the list of conditions in future updates of the review, if more information about diagnostic instruments becomes available and once studies that use these criteria have been performed.

See Table 3 for an overview of all diagnostic categories of somatoform disorders and MUPS, and a clear indication of whether or not they were eligible for the current review.

1. Diagnostic categories of somatoform disorders and medically unexplained physical symptoms and their eligibility for the current review.

| Eligible for this review? | |||

| DSM‐IV | ICD‐10 | YES | NO |

| Somatisation disorder | Somatisation disorder | x | ‐ |

| Undifferentiated somatoform disorder (duration > 6 months) | Undifferentiated somatoform disorder (duration > 6 months) | x | ‐ |

| ‐ | Somatoform autonomic dysfunction | x | ‐ |

| Pain disorder | Persistent somatoform pain disorder | x | ‐ |

| Somatoform disorders, unspecified | Somatoform disorders unspecified | x | ‐ |

| Hypochondriasis | Hypochondriacal disorder | ‐ | x |

| ‐ | Other somatoform disorders | ‐ | x |

| Body dysmorphic disorder | Body dysmorphic disorder | ‐ | x |

| Conversion disorder | Dissociative and conversion disorders | ‐ | x |

| YES | NO | ||

| Alternative somatoform diagnoses (such as abridged somatisation disorder or multisomatoform disorder) | x | ‐ | |

| Chronic MUPS (duration ≥ 6 months) | x | ‐ | |

| Functional somatic syndromes | ‐ | x | |

| Specific functional somatic symptoms | ‐ | x | |

DSM: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; ICD: International Classification of Diseases.

Co‐morbidities

As we aimed to summarise interventions for multiple symptoms, we excluded studies that examined participants diagnosed with only one specific functional syndrome or symptom (e.g. fibromyalgia or fatigue). Moreover, existing Cochrane reviews address specific syndromes and complaints (Bernardy 2013; Price 2008; Zijdenbos 2009).

Setting

We place no restrictions on the type of setting.

Subsets of participants

Some studies could include 'eligible' participants as well as 'ineligible' participants for this review, for example when an age cut‐off was used that was different to the cut‐off of this review. When no detailed information was available about these subsets of participants, we requested the data from the trial authors. If this did not yield any further information, we included the study only if at least 80% of the sample population had the characteristic of interest (e.g. aged 18 years or over). The Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies tables document the decisions about the eligibility of these subsets of participants. We assessed the impact of these decisions using sensitivity analysis.

Types of interventions

Experimental interventions

Eligible studies included one or more of the following experimental interventions.

-

Psychological therapies:

CBT (e.g. reattribution therapy and problem‐solving therapy);

behavioural therapy (e.g. classical CBT, biofeedback therapy, relaxation therapy, and psycho‐education);

third‐wave CBT (e.g. mindfulness);

psychodynamic therapies (e.g. group therapy);

humanistic therapies (e.g. person‐centred therapy);

integrative therapies (e.g. cognitive analytical therapy).

-

Physical therapies:

physical activity training (e.g. graded activity training);

other physical therapies (e.g. activation therapy or running therapy).

We excluded interventions based on complementary medicine from this review. In addition, pharmacological interventions and consultation letter interventions were beyond the scope of this review; they were evaluated in other Cochrane reviews (Hoedeman 2010; Kleinstäuber 2013). However, in several of the studies, in both study arms a consultation letter was sent to the primary care physician after baseline assessment, in addition to the planned psychological therapy or comparison condition. Post‐hoc, we decided that this was not a reason for exclusion, and we categorised these studies according to the main comparison (We conducted a sensitivity analysis to explore this decision).

Comparator interventions

We accepted the following comparator interventions.

Normal/usual treatment (e.g. treatment according to (multidisciplinary) guidelines or common practice in primary or secondary care) or waiting list procedures.

Attention or psychological placebo (an attention placebo was regarded as being inactive by both participants and researchers in a trial, while a psychological placebo was regarded as active by participants but inactive by researchers).

Enhanced or structured care (e.g. care as usual by physician trained in reattribution, or structured appointments with a physician without a specific treatment being performed). This comparator was not foreseen at the protocol stage, but added afterwards (see Differences between protocol and review).

Other psychological therapies (as per the list of experimental interventions above).

Other physical therapies (as per the list of experimental interventions above).

Types of outcome measures

We included studies that met the inclusion criteria described above regardless of whether they reported on the following outcomes.

Primary outcomes

(Outcomes marked with an asterisk were included in the 'Summary of findings' tables).

1. Severity/intensity of somatic symptoms*

If a validated self report scale was used for symptom severity, we extracted the results for this instrument for the meta‐analysis. Validated scales for the assessment of MUPS considered for this review were already described in Criteria for considering studies for this review above. Where multiple visual analogue self report scales or unvalidated scales were used, the first two review authors (NvD, MdB) decided which scale most closely approximates MUPS. This was supervised by two other review authors (HvdH, BT), who were experts on somatoform disorders, MUPS, and clinical diagnostics, but who were not directly involved in the process of study selection or data extraction and management, so that they were blinded to the results. We examined clinician‐rated severity of MUPS separately and it was not combined with self report outcomes into one effect‐size index.

2. Acceptability*

We measured acceptability by the complement of the proportion of trial participants who dropped out during the trial from either the experimental or the comparator intervention.

Secondary outcomes

3. Depression and anxiety

We distinguished between validated clinician‐rated instruments (e.g. the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) (Hamilton 1960), the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HARS) (Hamilton 1959)), and participant self report instruments (e.g. BDI (Beck 1961), and the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (Beck 1988)).

4. Dysfunctional cognitions, emotions, or behaviours (participant‐rated)*

We measured dysfunctional cognitions, emotions, or behaviours by validated self report scales (e.g. the Whitely Index (WI) (Pilowsky 1967), Illness Attitude Scales (IAS) (Kellner 1986), and the Scale for the Assessment of Illness Behavior (SAIB (Rief 2003)).

5. Adverse events

We expected that the frequency of adverse events of non‐pharmacological interventions would be low, but not absent. Forms of psychotherapy may lead to psychological decompensation, while an intervention such as running therapy may lead to certain injuries. When possible, we described the most common adverse effects for the included studies narratively (defined as effects that occur in at least 10% of participants receiving the specific therapy), as well as significant differences in the rate of occurrence of adverse events between intervention and control groups. However, it must be noted that RCTs and CRCTs are not the optimal study design for obtaining information about rare or long‐term adverse outcomes, limiting our interpretation of adverse effect data.

6. Treatment response (responder versus non‐responder)*

We measured treatment response using the clinician‐rated Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI) ‐ Improvement item (Guy 1976); this scale defined responders as those with a score of "1 = very much improved" or "2 = much improved". Alternatively, we used the number of participants who responded to the treatment according to the author's definition. We calculated response rates out of the total number of randomised participants.

7. Functional disability and quality of life*

We assessed functional disability and quality of life through validated clinician‐rated scales (e.g. the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) (Hall 1995)) or validated self report instruments (e.g. the 36‐item Short Form Questionnaire (SF‐36) (Ware 1992); or the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) (Sheehan 1983)).

8. Healthcare use*

We assessed healthcare use as measured by direct measurements (e.g. consultation counts), or through participant‐rated measurements (e.g. healthcare use diary or Trimbos/iMTA questionnaire for Costs associated with Psychiatric Illness (TiC‐P; Hakkaart‐van Roijen 2002).

Hierarchy of outcome measures

If there were multiple instruments measuring the same outcome, we preferred whichever instrument was most commonly used from those listed above. Several studies used both the Physical Component Scale (PCS) and the Mental Component Scale (MCS) of the SF‐36, and sometimes also the subdomains. In these cases, we restricted ourselves to the main domains and combined PCS and MCS into one outcome.

Timing of outcome assessment

We analysed primary and secondary outcomes at the following time points, if available:

immediately post treatment;

within 12 months after treatment ending; and

more than 12 months after treatment ended.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Review Group's Specialized Register (CCDANCTR)

The Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group (CCDAN) maintains two clinical trials registers at the editorial base in Bristol, UK: a references register and a studies‐based register. The CCDANCTR‐References Register contains over 36,000 reports of RCTs in depression, anxiety and neurosis. Approximately 60% of these references have been tagged to individual, coded trials. The coded trials are held in the CCDANCTR‐Studies Register and records are linked between the two registers through the use of unique Study ID tags. Coding of trials is based on the EU‐Psi coding manual, using a controlled vocabulary. Reports of trials for inclusion in the Group's registers are collated from routine (weekly), generic searches of MEDLINE (1950 to date), EMBASE (1974 to date), and PsycINFO (1967 to date); quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and review‐specific searches of additional databases. Reports of trials are also sourced from international trials registers c/o the WHO trials portal (the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP)), pharmaceutical companies, and handsearching of key journals, conference proceedings, and other (non‐Cochrane) systematic reviews and meta‐analyses.

Details of CCDAN's generic search strategies (used to identify RCTs) can be found on the Group's website.

1. We searched the CCDANCTR (Studies and References Registers) on 29 November 2013 using the following free‐text terms: (somatization or somatisation or somatoform or hysteri* or briquet or polysymptom* or multisomatoform or somatizer* or (somatic NEAR symptom*) or (MUPS or “medical* unexplained” or "unexplained medical*" or (unexplained NEAR (symptom* or syndrom*)) or "frequent attend*" or (multiple NEAR (“physical symptom*” or “symptom diagnos*”)) OR neurastheni*)

We screened the records retrieved manually for non‐pharmacological interventions.

2. We conducted complementary searches on the following bibliographic databases using relevant subject headings (controlled vocabularies) and search syntax, appropriate to each resource:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (all years) (Appendix 1);

Web of Science (from 1945 onwards, cited references search only (April 2014)).

3. To identify ongoing trials, we searched the ClinicalTrials.gov register (clinicaltrials.gov/), the Current Controlled Trials metaRegister of Controlled Trials ‐ active registers (mRCT; www.controlled‐trials.com/mrct/), and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform Search Portal (www.who.int/trialsearch).

We applied no restrictions regarding date, language, or publication status to the searches. We will revise the search strategies for future updates, as these will include studies that use DSM‐5 criteria.

Searching other resources

Grey literature

We searched the ProQuest Dissertation & Theses Database (www.proquest.com), National Guideline Clearing House (guideline.gov/) and Open Grey (www.opengrey.eu/) for grey literature.

Handsearching

We searched the conference proceedings for the following associations from 2009 if available (for titles not already indexed in EMBASE or PsycINFO, or already handsearched within The Cochrane Collaboration).

Annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association (APA);

International Congress of Behavioral Medicine (ICBM);

European Conference on Psychosomatic Research (ECPR);

Annual Meeting of the European Association for Consultation‐Liaison Psychiatry and Psychosomatics (EACLPP);

Annual congress of the Dutch Network on Unexplained Physical Symptoms (NOLK).

Reference lists

We checked the reference lists of all included studies and relevant systematic reviews to identify additional studies that might have been missed from the original electronic searches (e.g. references that were unpublished or in press). We also conducted a cited reference search on the Web of Science (15 April 2014) for citations to primary reports of included studies.

Correspondence

We contacted researchers and subject experts for information on unpublished or ongoing studies or to request additional trial data.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

In the first step, two review authors (NvD, MdB) independently screened the titles and abstracts of reports identified from the literature search. We discarded studies that obviously did not fulfil the inclusion criteria at this stage of the screening process. Two review authors (NvD, MdB) retrieved eligible or potentially eligible articles for full‐text assessment. We identified and excluded duplicate records and we collated multiple reports that related to the same study so that each study ‐ rather than each report ‐ was the unit of interest in the review. After full‐text assessment, the review authors identified studies for inclusion and exclusion. We recorded reasons for exclusion of studies, and resolved disagreements by consensus ‐ if necessary with the involvement of a third review author (JvdW). We listed studies for which additional information was required in order to determine their suitability for inclusion in the review as 'Studies awaiting assessment'. We recorded the selection process in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram (Moher 2009), and Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

Data extraction and management

We used a data collection form, piloted on one study in the review, to extract study characteristics and outcome data. Independently, four review authors (NvD, MdB, HvdW, HvM) extracted study characteristics and outcome data from included studies. If necessary, we contacted the authors of trial reports for clarification or for additional information. We organised data using the most recent version of Review Manager 5 software (RevMan 2012). We negotiated disagreements with another review author. We extracted data on the following study characteristics.

Trial characteristics: first author, publication year, status of publication, language of publication.

Details of methodology: study design, study setting, total duration of study, details of any 'run‐in' period, number of study centres and location, withdrawals, lost to follow‐ups.

Participants' characteristics: source of sample, size of sample, mean age, age range, gender, severity and duration of MUPS at baseline, diagnostic criteria, inclusion and exclusion criteria, selection instrument (e.g. interview), presence of a somatoform diagnosis, co‐morbidity, and previous treatments for MUPS.

Intervention characteristics: intervention, category of non‐pharmacological intervention, healthcare provider performing the intervention, intervention frequency and duration, comparison, concomitant MUPS‐related interventions (e.g. pharmacotherapy) and number of drop‐outs due to adverse effects or inefficacy of treatment.

Outcome measures: primary and secondary outcome measures (as specified in Primary outcomes; Secondary outcomes), summary statistics of continuous data (mean, standard deviation (SD)) and dichotomous data (number of responders), timing of outcome assessments, intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis (with last observation carried forward (LOCF)) or observed cases/completer analysis and other methods of estimating the outcome for participants who dropped out (e.g. mixed‐effect analyses).

Notes: source of funding for trial and any notable conflicts of interest for trial authors.

We noted in the Characteristics of included studies table whether outcome data were reported in a usable way. We resolved disagreements by consensus. Two review author (NvD, HvdW) entered data into Review Manager 5 for analysis (RevMan 2012). We double‐checked that data had been entered correctly by comparing the data presented in the systematic review with the data in the study reports. A third review author (MdB) spot‐checked study characteristics for accuracy against the trial reports.

Main comparisons

We aimed to stratify comparisons according to treatment classes as described in Types of interventions when the available data allowed. For physical therapies, we planned to perform a specific analysis for physical activity training, all other therapies would be combined into one group. We planned the following main comparisons for each class of non‐pharmacological treatment.

Treatment versus care as usual or waiting list procedures.

Treatment versus attention or psychological placebo.

Treatment versus another non‐pharmacological treatment.

After inclusion of eligible articles, we concluded that all studies addressed some form of psychological therapy; no studies addressed 'treatment versus attention or psychological placebo'; and no studies addressed any form of physical therapy. In addition, as mentioned above (How the intervention might work), we found several studies comparing a psychological therapy to a form of enhanced or structured care. As a result of these findings, we decided to add the comparison 'psychological therapy versus enhanced care'. So the final categorisation of comparisons was as follows:

psychological therapy versus usual care (or waiting list procedures);

psychological therapy versus enhanced (or structured) care;

psychological therapy versus another psychological therapy.

If in future updates of this review we find new studies not fitting into this categorisation (e.g. comparing some physical therapy with psychological therapy), we will update the categorisations.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Independently, two review authors (NvD, MdB) assessed the risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreements by discussion or by involving another review author (HvM, HvdW). We assessed the risk of bias for the following domains.

Random sequence generation: was the method used to generate the sequence of randomised allocation adequate for the production of comparable groups?

Allocation concealment: was the allocation adequately concealed so that intervention allocations could not have been foreseen in advance of, or during, enrolment?

-

Blinding:

was knowledge of the allocation of treatment by the participants and study personnel adequately prevented during the study?

was knowledge of the allocation of treatment by the outcome assessor(s) adequately prevented during the study?

Incomplete outcome data: were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed? Was the completeness of outcome data described, including attrition and exclusions from analyses? If there were attritions and exclusions in the treatment and control groups, they were reported, along with the underlying reasons? We also reported whether the review authors conducted any re‐inclusions in their analyses.

Selective outcome reporting: were reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting?

Other sources of bias: was the study apparently free of other sources that could produce risk of bias?

Treatment fidelity: were therapies based on protocols or manuals? Were therapy sessions adequately monitored to assess whether they adhered to treatment protocols and manuals?

Researcher allegiance: could researchers be expected to have a preference for one of the treatment modalities?

Therapist qualifications: were the therapists qualified to perform the interventions?

In order to assess risk of bias in the following specific types of study design, we made additional judgements.

Multiple‐intervention studies: were data presented for each of the groups to which participants were randomised?

-

Cross‐over trials:

was it clear that the order of receiving a treatment was randomised?

were unbiased data from the first treatment period available?

-

CRCTs:

were individuals recruited to the trial after the clusters had been randomised?

were methods of stratified or pair‐matched randomisations of clusters used?

were adequate statistical analyses (taking clustering into account) used?

We judged each potential source of bias as to be of high, low, or unclear risk and provided a supporting quotation from the study as justification for our judgement in the 'Risk of bias' table. We summarised the risk of bias judgements across different studies for each of the domains by means of a 'Risk of bias' figure. Where information on risk of bias related to unpublished data or correspondence with researchers, we noted this in the 'Risk of bias' table. When considering treatment effects, we took into account the risk of bias for the studies that contributed to each outcome.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous outcomes, we used risk ratio (RR) as the summary statistic, together with 95% confidence intervals (CI). If relevant, we calculated the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) for every class of non‐pharmacological treatment for which we found a statistically significant treatment effect. We used the RR estimate and the control risk from the pooled control groups for this calculation.

Continuous data

As different measures were used to assess the same outcome, we pooled data using the standardised mean difference (SMD); we calculated 95% CI. Specific attention was paid to the secondary outcome 'functional disability and quality of life', as the direction of scales for these outcomes can differ. An increase on a scale of functional disability usually indicates deterioration, while an increase on a scale for quality of life often indicates improvement. We ensured that it was appropriate to pool the data (e.g. different instruments measuring the same underlying concept). Using the SMD does not correct for such differences in the direction of scales. In this case, we multiplied the mean values from the smaller set of studies by ‐1 to ensure that all the scales pointed in the same direction.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised controlled trials

In order to avoid unit‐of‐analysis errors for trials in which incorrect statistical analyses were conducted, we performed approximate analyses for continuous outcomes based on inflating standard errors. Before we entered data into Review Manager 5 for meta‐analytic calculations (RevMan 2012), we multiplied the standard error of the effect estimate (from an analysis that did not take clustering into account) by the square root of the design effect. The design effect was 1+ ((M‐1)* ICC), where M was the mean cluster size and ICC was the intracluster correlation coefficient. We assumed a common design effect across intervention groups. If the ICC was not available in the published report, we used an external estimate (0.03) obtained from Campbell 2005. We meta‐analysed these inflated variances using Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2012), and the generic inverse‐variance method. For dichotomous data, we divided both the number of events and the group sizes by the design effect (Higgins 2011, Chapter 16.3).

Studies with multiple treatment groups

In trials with more than two relevant non‐pharmacological treatment arms, we managed data as follows.

If the different experimental treatments were of the same class of treatments (e.g. psychotherapy), we summarised them into a single group and compared it with the control group. For continuous data, we pooled means and SDs across all of the treatment arms as a function of the number of participants in each arm (Higgins 2011, Table 7.7.a). For dichotomous outcomes, we summed both the sample sizes and the numbers of participants with events across groups.

If the different treatments were of different classes (e.g. a form of psychotherapy versus a physical activity intervention), we included each pair‐wise comparison separately, but divided the 'shared control‐group' into two or more smaller groups (according to the number of intervention groups). For dichotomous outcomes, we divided both the number of events and the total number of participants over these groups. For continuous outcomes, we divided only the total number of participants over these groups and left the means and SDs unchanged. Although this method only partially overcomes the unit‐of‐analysis error, the advantage of this approach is that it permits investigation of heterogeneity across intervention arms.

Cross‐over trials

We found no cross‐over trials. For future updates of our review, we will only include cross‐over trials for meta‐analysis if relevant data are available, or can be obtained, from the first treatment period for both the treatment and control group(s).

Dealing with missing data

We attempted to contact trial authors in order to verify key study characteristics and obtain outcome data that were not reported in the articles. When we could not retrieve missing data, we managed the data as follows.

Dichotomous data

We managed missing dichotomous data through ITT analysis, in which we assumed that participants who dropped out after randomisation had a negative outcome. We conducted sensitivity analyses for dichotomous data according to Gamble and Hollis (Gamble 2005): we calculated best‐case/worst‐case scenarios for the clinical response outcome, in which we assumed, for the best‐case scenario, that drop‐outs in the active treatment group had positive outcomes and those in the control group had negative outcomes; and, for the worst‐case scenario, that drop‐outs in the active treatment group had negative outcomes and those in the control group had positive outcomes. This method provided boundaries for the observed treatment effect.

Continuous data

Where continuous data were missing, we performed analysis on an endpoint basis, including only participants with a final assessment, or by using LOCF to the final assessment where reported by the trial authors. If necessary, we performed sensitivity analyses where we compared outcomes with the observed case data versus the LOCF data. When using LOCF data, we used the baseline SD as a more conservative approach. If SDs were missing, we calculated them from t‐, F‐, P, or CI values (Higgins 2011), or standard errors (Altman 1996).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed the groups for clinical similarities including elements such as age, gender, and setting.

First, we assessed statistical heterogeneity visually by inspecting forest plots of standardised mean effect sizes and of relative risks. We used the I2 statistic as a second test: I2 describes the percentage of variability in effect estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance.

We used conventions of interpretation defined by Higgins (Higgins 2011). In the case of substantial levels (i.e. where I2 = 50% to 90%) and considerable levels (I2 = 75% to 100%) of heterogeneity, we explored data further by means of subgroup and sensitivity analyses (see below). However, these were not clear‐cut criteria, as the importance of the observed I2 also depends on the magnitude and direction of treatment effects and the strength of evidence for heterogeneity (Deeks 2008; Higgins 2003); for example: if the I2 value fell slightly below 50% (e.g. 45%) and the direction and magnitude of treatment effects suggested important heterogeneity, we investigated the data further.

Assessment of reporting biases

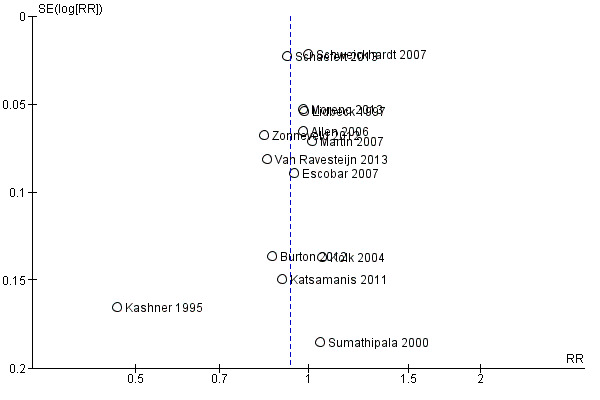

We created funnel plots (treatment effect versus standard error of the effect size), if we included at least 10 trials in a meta‐analysis, according to the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011; Sterne 2011). When analysing and interpreting a funnel plot, we considered all potential reasons for asymmetry, not just publication bias (e.g. differences in methodological quality, true heterogeneity in intervention effects).

Data synthesis

If we found two or more included studies in a comparison category (see Data extraction and management) that used the same outcome construct, we performed a meta‐analysis of the results. Two authors (NvD, JvdW) entered data into Review Manager 5 software (RevMan 2012). We expected to find high heterogeneity in non‐pharmacological therapy approaches and in symptom severity, duration of symptoms and co‐morbidities among the various study populations. Therefore, we analysed dichotomous and continuous treatment effects using a random‐effects model. For studies of which data could not be combined, we summarised the results narratively.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If analysis of heterogeneity indicated significant heterogeneity, we performed subgroup analysis in order to explore whether methodological and clinical differences between the trials had produced systematic differences observed in the treatment outcomes. If we found statistically significant differences between subgroups, we reported the results of the corresponding subgroup meta‐analysis. If subgroup analysis provided no explanation for heterogeneity, we did not report the results of meta‐analysis.

When available data allowed (at least 10 studies), we performed subgroup analyses based on the following factors (only for the primary outcomes).

Severity, based on symptom count, and duration of MUPS at baseline.

Diagnosis at baseline.

Somatoform disorders versus alternative somatoform diagnoses versus MUPS.

Psychiatric and somatic co‐morbidity: as known from various mental disorders, co‐morbid psychological and somatic problems can modify the efficacy of an intervention. Therefore, we compared the effects of non‐pharmacological interventions for people with somatoform disorders or MUPS with or without co‐morbid mental or somatic disorders.

Primary care versus secondary care and tertiary care, including healthcare provider performing the intervention.

Treatment as usual versus a waiting list procedure as a control intervention.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned sensitivity analyses to evaluate the robustness of the conclusions in conjunction with decisions made during the review process. Sensitivity analyses would inform that the results of the review did not depend on specific decisions that were made during the review process. In case of sufficient data (i.e. at least 10 studies), we planned these analyses to examine the effects of the following options, restricted to the primary outcome.

Exclusion of CRCTs.

Exclusion of studies with unclear allocation concealment, or only a subset of relevant participants.

Exclusion of studies with unclear methods of sequence generation.

Exclusion of trials where missing data have been imputed.

Exclusion of studies with a drop‐out rate higher than 20%.

'Summary of findings' tables

We added 'Summary of main results' tables for the two main comparisons to create a structured overview of the main review results for the two subgroup comparisons with the largest number of studies: CBT versus usual care and CBT versus enhanced care. The table only includes information about the outcome measures marked with an asterisk (see Primary outcomes; Secondary outcomes), as these were considered the most important for the current review. For the same reason, the selected time point was end of therapy, except for healthcare use, where we thought the period within one year after end of treatment was more meaningful. For dichotomous outcomes (acceptability, treatment response), we reported an assumed and corresponding absolute risk with 95% CI as well as a relative risk ‐ corresponding to the RR with 95% CI obtained from meta‐analysis. For continuous outcomes, in the column of assumed and corresponding risk, we presented a difference in means or SMD with 95% CI. We used footnotes in order to specify the source or rationale for each assumed and corresponding risk. In order to assess the quality of body of evidence for each outcome, we used the GRADE approach (GRADEpro software; Schünemann 2008), classifying the quality of evidence for each study as 'high', 'moderate', 'low', or 'very low'. We explained judgements other than 'high' quality in footnotes or the Comments column in the 'Summary of main results' table.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

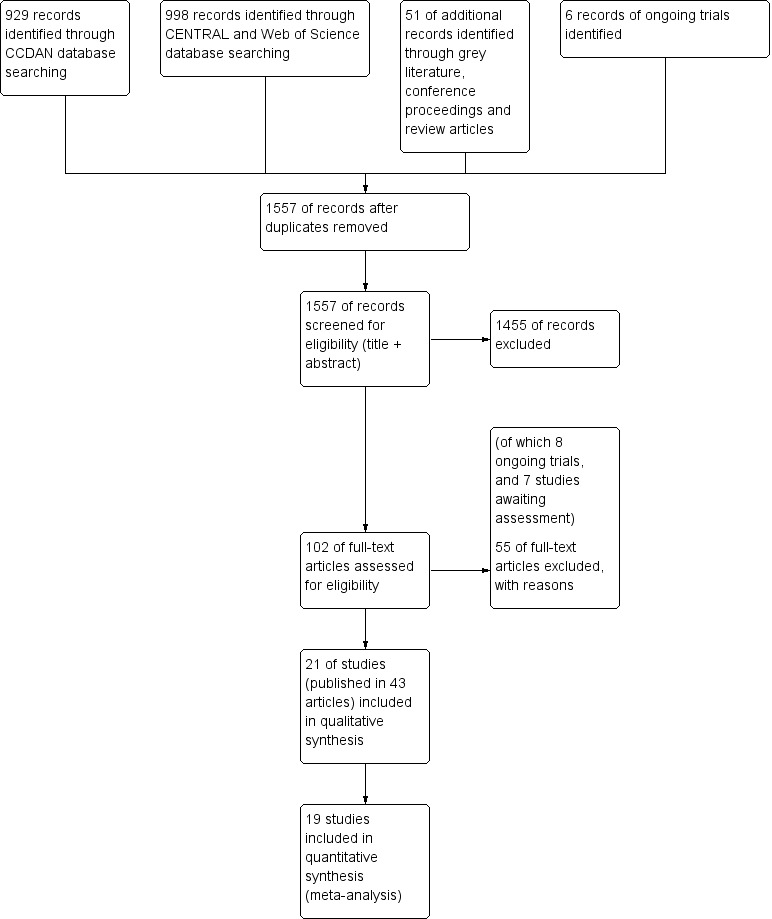

Searches were conducted up to November 2013 (CCDAN registers) and April 2014 (cited reference searches). Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection.

1.

6 Study flow diagram.

Literature database searches

In the search of the CDANCTR‐Studies and CCDANCTR‐Reference Register (from now on referred to as CCDAN database), we found 929 abstracts after de‐duplication. We excluded 842 records, based on the title and abstract, leaving 82 references (65 studies) selected for full‐text retrieval. After reading the full‐text, we judged 27 studies (49 articles) eligible for inclusion in this review. We excluded 35 studies (38 articles) and six articles are still awaiting assessment, for example, due to unavailability of a full‐text article or difficulties in contacting authors.

The search of CENTRAL database found 995 records. After removing duplicates from the CCDAN search, there were 568 new references. After title and abstract screening, we excluded 560 references, and selected eight articles for full‐text reading. After full‐text reading, we excluded five articles, and judged three articles eligible for inclusion; however, all three articles described studies already included in the review (e.g. long‐term follow‐up results) (Gili 2014; Schröder 2013; Zonneveld 2012). As the Schröder article reported a more detailed trial methodology and higher number of participants, we decided to use this article as the main reference of this study (Schröder 2013) instead of Zaby 2008, which was retrieved from the CCDAN search.

We performed a cited reference search on the Web of Science, for citations to primary reports of all studies expected to be included in this review. When handsearching the retrieved articles, we identified three additional relevant references. After full‐text reading, we included one new study (Burton 2012), and excluded one article due to randomisation method (Rembold 2011). One article (Chernyak 2014) described an already included study (Sattel 2012).

Grey literature

We performed searches for grey literature in the databases of www.guideline.gov (36 results), www.opengrey.eu (eight results), and www.proquest.com (no results). We found no new articles. We screened the conference proceedings of the International Congress of Behavioral Medicine (ICBM, 2010 and 2012), the Annual Meeting of the European Association for Consultation‐Liaison Psychiatry and Psychosomatics and the European Conference on Psychosomatic Research (EACLPP/ECPR, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012), the Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association (APA, abstracts and syllabus of 2009‐2013), and the Annual congress of the Dutch Network on Unexplained Physical Symptoms (NOLK, 2013) and found no new articles.

Systematic reviews

We found 14 reviews about (specific) non‐pharmacological interventions for somatoform disorders or MUPS. After title screening in the reference lists of the reviews, we selected seven additional articles for screening of abstract. After abstract reading, we excluded four articles, and selected three articles for full‐text reading. However, none of these three articles were eligible due to lack of randomisation or inappropriate selection method (Hellmann 1990; Lupke 1996; Tschuschke 2007).

Trial registers

We performed ongoing trial searches in the databases of www.clinicaltrials.gov, www.controlled‐trials.com, and www.who.int/trialsearch. We found six potentially eligible ongoing trials. As full details of the design and study results were not available, we could not included these studies in the review (see Characteristics of ongoing studies table).

Contacting authors

We tried to contact 10 trial authors for missing information regarding the eligibility of studies; four responded and provided the desired information (Lidbeck 1997; Gottschalk 2011; Pols 2008; Steel 2011). The other six trials are listed in the Studies awaiting classification table.

We contacted authors of 20 of the included studies for additional information regarding study design and outcomes, of which 10 provided requested data.

Included studies

We included 21 studies, reported in 43 publications, in this review (see Characteristics of included studies table). All included studies concerned psychological interventions.

Design

Twenty of the included 21 studies had a parallel‐group, individually randomised design (RCT). One study had a cluster‐randomised design (Schaefert 2013). We found not trials with a cross‐over design.

Sample size

The total number of randomised participants was 2658, a mean number of 127 per study (range 32 to 328). Two studies included fewer than 25 participants per arm (Burton 2012; Katsamanis 2011). Most studies reported 25 to 75 participants per arm. Three studies included 75 to 100 participants per arm (Escobar 2007; Schilte 2001; Sumathipala 2008), and two studies included more than 100 participants per arm (Sattel 2012; Schaefert 2013). The largest study was Schaefert 2013, with 328 randomised participants.

Setting

Eight studies recruited participants in primary care only (Burton 2012; Escobar 2007; Moreno 2013; Schaefert 2013; Schilte 2001; Sumathipala 2000; Sumathipala 2008; Van Ravesteijn 2013). Only two studies recruited in secondary care (e.g. outpatient clinics) (Sattel 2012;Speckens 1995), and one study recruited inpatients in hospitals (Schweickhardt 2007). Seven studies recruited via medical settings as well as the open population (e.g. through advertisements) (Allen 2006; Kashner 1995; Katsamanis 2011; Kolk 2004; Martin 2007; Schröder 2013; Zonneveld 2012). Three studies recruited via primary care as well as secondary care (Fjorback 2013; Lidbeck 1997; Schröder 2012).

In one study, treatment was performed in group sessions by GPs in primary care who were trained in the specific psychological technique, combined with a psychosomatic specialist (Schaefert 2013). In six other studies, treatment took place at a department of psychiatry or psychology (Allen 2006; Escobar 2007; Fjorback 2013; Katsamanis 2011; Kolk 2004; Van Ravesteijn 2013). Another six studies treated participants in other outpatient clinics (Kashner 1995; Lidbeck 1997; Schröder 2012; Sumathipala 2000; Sumathipala 2008; Zonneveld 2012). Five studies treated participants in specific outpatient symptom clinics or outpatient clinics for psychosomatics (Burton 2012; Martin 2007; Sattel 2012; Schröder 2013; Speckens 1995). One study treated participants as inpatients (they were admitted to a ward) (Schweickhardt 2007). One study treated participants at home (Schilte 2001). Finally, in one study the treatment setting was unknown (Moreno 2013).

Five of 21 studies were carried out in the Netherlands (Kolk 2004; Schilte 2001; Speckens 1995; Van Ravesteijn 2013; Zonneveld 2012). Five studies were carried out in Germany (Martin 2007; Sattel 2012; Schaefert 2013; Schröder 2013; Schweickhardt 2007). Other studies were carried out in the USA (Allen 2006; Escobar 2007; Kashner 1995; Katsamanis 2011), Denmark (Fjorback 2013;Schröder 2012), Spain (Moreno 2013), Sri Lanka (Sumathipala 2000; Sumathipala 2008), Scotland (Burton 2012), and Sweden (Lidbeck 1997). Only two studies were carried out in a developing country (Sri Lanka) (Sumathipala 2000; Sumathipala 2008).

Several of the included studies were performed by the same research groups, or at least had an overlap of authors. This was the case for the studies of Allen 2006, Escobar 2007, and Katsamanis 2011, for the studies of Fjorback 2013 and Schröder 2012, for the studies of Sumathipala (Sumathipala 2000; Sumathipala 2008), and for the studies of Speckens 1995 and Van Ravesteijn 2013.

Participants

Proportion of women

Most studies recruited women than men, as found in epidemiological studies (Fink 1999; Fink 2004). Only one study reported more men in the intervention group (56%, Speckens 1995). The proportion of women among all participants in all treatment groups ranged between 66% (Burton 2012) and 89% (Allen 2006;Escobar 2007).

Age

The mean age was 43 years in all included studies, ranging from 35 years (Kolk 2004;Sumathipala 2008) to 49 years (Martin 2007;Schaefert 2013). One study did not provide the mean age of participants (Katsamanis 2011), but only provided data about the proportion of participants under and over 40 years old.

Diagnosis