Abstract

Introduction

An important strategy to combat yield loss challenge is the development of varieties with increased tolerance to drought to maintain production. Improvement of crop yield under drought stress is critical to global food security.

Methods

In this study, we performed multiomics analysis in a collection of 119 diverse rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) varieties to dissect the genetic control of agronomic traits in two watering regimes [well-watered (WW) and drought stress (DS)] for 3 years. In the DS treatment, irrigation continued till the 50% pod development stage, whereas in the WW condition, it was performed throughout the whole growing season.

Results

The results of the genome-wide association study (GWAS) using 52,157 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) revealed 1,281 SNPs associated with traits. Six stable SNPs showed sequence variation for flowering time between the two irrigation conditions across years. Three novel SNPs on chromosome C04 for plant weight were located within drought tolerance-related gene ABCG16, and their pleiotropically effects on seed weight per plant and seed yield were characterized. We identified the C02 peak as a novel signal for flowering time, harboring 52.77% of the associated SNPs. The 288-kbps LD decay distance analysis revealed 2,232 candidate genes (CGs) associated with traits. The CGs BIG1-D, CAND1, DRG3, PUP10, and PUP21 were involved in phytohormone signaling and pollen development with significant effects on seed number, seed weight, and grain yield in drought conditions. By integrating GWAS and RNA-seq, 215 promising CGs were associated with developmental process, reproductive processes, cell wall organization, and response to stress. GWAS and differentially expressed genes (DEGs) of leaf and seed in the yield contrasting accessions identified BIG1-D, CAND1, and DRG3 genes for yield variation.

Discussion

The results of our study provide insights into the genetic control of drought tolerance and the improvement of marker-assisted selection (MAS) for breeding high-yield and drought-tolerant varieties.

Keywords: drought, gene ontology, linkage disequilibrium, QTN, RNA-sequencing, single-nucleotide polymorphism, yield

1. Introduction

Rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) is a member of the Brassicaceae family and is ranked second in global oilseed production (Meyer and Purugganan, 2013; FAO, 2018; Raboanatahiry et al., 2018). It is utilized almost entirely for oil production, food, feedstock, and biodiesel production. Rapeseed, originated from interspecific hybridization between turnip rape (B. rapa, AA, 2n = 20) and cabbage (B. oleracea, CC, 2n = 18), is the most widespread oilseed crop in various climates due to the ability to germinate and grow at low temperatures (Ren et al., 2000; Chalhoub et al., 2014; Koh et al., 2017; Wozniak et al., 2019).

Understanding the genetic bases of yield-related trait is of great significance for breeding high-yield rapeseed (Shi et al., 2011; Khan et al., 2018; Raboanatahiry et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2021). Although both spring and winter growth habit forms have been identified in rapeseed, the winter form has shown a higher grain yield (Fordonski et al., 2016). The grain yield of rapeseed can be directly increased through selection for fecundity and by indirect selection for phenological traits which show complicated genetic control in plants (Nowosad et al., 2016; Marjanovic-Jeromela et al., 2019). Nevertheless, the polygenic nature of the genetic control of yield and its components and the influence of environmental variables complicates mining genetic loci contributing to stress tolerance in plants including rapeseed. Water-deficit stress in the period between the flowering stage and pod formation stages causes up to around 30% loss in grain yield (Elferjani and Soolanayakanahally, 2018).

Drought stress in arid and semiarid areas restricts plant growth and production in agriculture (Haq et al., 2014; Seleiman et al., 2021). At the early vegetative growth stage, drought slows down the rapeseed growth by inhibiting cell expansion and division (Yosefi and Heidari, 2022). However, drought at the reproductive development stage could drastically reduce rapeseed yield by producing small and medium-sized grains (Hatzig et al., 2018). Several studies have been conducted to evaluate the drought tolerance of rapeseed (Yarnia et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2021). However, progress in improvement for drought tolerance is slow because of the complex genetic architecture of drought stress tolerance controlled by several minor and major genes (Bernardo, 2008). Understanding the genetic control of drought tolerance mechanisms can significantly accelerate the development of drought-tolerant varieties through marker-assisted selection (MAS) and genomic selection (GS).

Genome-wide association studies (GWASs) are currently the powerful tool to detect marker–trait associations (MTAs) and can be applied to mapping and identifying linked markers and candidate genes contributing to drought tolerance (Xiao et al., 2017). In rapeseed, GWAS has been used to identify loci and candidate genes for drought stress tolerance (Zhang et al., 2015; Khanzada et al., 2020; Shahzad et al., 2021; Salami et al., 2024). In a study consisting of 157 genotyped inbred rapeseed cultivars, GWAS was used to identify 320 SNPs linked with both seed weight (SW) and silique length (SL) traits and mapped to the gene BnaA.ARF18 (Dong et al., 2018). In another study, 197 candidate genes were detected for budding, bolting, day to flowering (DTF), and the interval between DTF and bolting in rapeseed of which FRIGIDIA (FRI), FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC), and AGAMOUS-like 16 (AGL16) showed significant contribution to flowering time (Helal et al., 2021). Raman et al. (2019) conducted an association analysis in canola accessions using 11,804 SNPs under normal irrigation and water-stressed conditions and identified 47 SNPs on chromosome A02, and an additional 13 SNPs on chromosome C03 were associated with flowering close to FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) and FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC) genes for the drought avoidance mechanism (Raman et al., 2020). In the Hu et al. (2022) study, 628 SNPs were identified for 56 agronomically important traits through GWAS in a panel of diverse rapeseed accessions. A whole-genome resequencing and multilocus genome-wide association study (ML-GWAS) in rapeseed accessions revealed that 908 SNPs for agronomic and phenological traits of which 79 candidate genes were associated with BnaA09g39790D (RNA helicase), BnaA09g39950D (Lipase), and BnaC09g25980D (SWEET7) genes (Zhang et al., 2023a).

Transcriptomics and RNA-seq technology exploits transcript sequences to estimate patterns of gene expression, alternative splicing, and allele-specific expression (Marguerat and Bahler, 2010; Zhang et al., 2023b). Transcript analysis can complement QTLs identified. In one study, RNA-seq was performed on eight tissues of extremely high- and low-harvest index (HI) rapeseed accessions and demonstrated that 33 functional candidate genes were located within the confidence intervals of significant SNPs associated with HI-related traits (Lu et al., 2016). In another study, Zhang et al. (2023a) performed GWAS and transcriptome analysis for seed yield and yield-related traits in Brassica napus for identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the seed of contrasting seed size/seed weight accessions.

Expanding rapeseed production areas through cultivation of drought-tolerant varieties could be an efficient strategy to alleviate the adverse effects of drought. Genomic studies focused on drought tolerance can be translated into breeding objectives for varietal development. In the present study, we aimed to identify novel SNPs and key genes for drought tolerance related traits in rapeseed. First, we investigated the effects of drought stress on agronomic, grain yield-related, and yield-related traits. Then, a GWAS approach was used to determine novel SNPs/genes for traits in the well-watered and drought stress conditions in 3 years. The RNA-Sequencing (RNA-Seq) experiment was performed in the leaf and seed of the contrasting high- and low-yielding varieties to validate the genes associated with the position of the identified linked SNPs. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the leaf and seed of the accessions in the yield contrasting varieties to explore the genetic basis of drought tolerance can be facilitated by integrated functional genomic approaches.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Plant materials, field experiment, and drought treatments

The plant materials used in this study consisted of 119 rapeseed varieties including breeding lines, hybrids, and commercial cultivars provided by the Institute of Seed and Plant Improvement (SPII), Iran ( Additional File 1 ). The field experiment was performed at the Research Farm of Plant Production and Genetics, Shiraz, Iran in a 3-year trial in 2017, 2018, and 2020 growing seasons. Plants growth was incomplete in a 2019 trial which was due to spring frost damage. The texture of the soil was silty loam, and concentrations of micro- and macronutrients are shown in Additional File 2 . Seasonal temperature, relative humidity, and mean precipitation are shown in Supplementary Figure S1 . The experimental design was a lattice by patterning 11 × 11-unit cells (11 varieties and 11 units per block) with three replicates per watering regime [well-watered (WW) and drought stress (DS)]. The plot size was 1 m2 with the between-plot distances of 0.5 m. Each plot was composed of four 1-m-long rows, each with 25 plants per 4-cm spaces. The seeds were sown on four rows 1 m in length on 17 September for the three seasons.

The fertilizers were applied at the rates of 250 kg N ha−1, 100 kg P ha−1, and 100 kg K ha−1. Phosphorus and potassium fertilizers were incorporated to the soil prior to sowing, and nitrogen was used as top dressed in different growth stages of rapeseed. In the well-watered condition, irrigation was carried out from planting till seed physiological maturity (maximum seed dry weight) as previously described by Ozer (2003). In the drought stress treatment, irrigation continued till the 50% pod development stage when irrigation then stopped till end of the growing season, which made three irrigation practices less in the drought-stressed plants than in the well-watered plants throughout the growing season. The numbers of irrigations in WW and DS treatments were 9 and 6, respectively.

For weed control, 3 L ha−1 Treflan® HFP herbicide was sprayed at sowing and hand weeding was also followed during the growing season. The Pirimor 50 pesticide at a rate of 2 L ha−1 was used for the aphids on rapeseed at the flowering and early podding periods. Harvesting time was the first week of July when the siliquae in terminal raceme turned creamy white in color.

2.2. Measurement of phenotypic characteristics

Days to flowering (DTF) was measured as the interval between the time of sowing and the time when the first flowers opened on 50% of the plants followed by Matar et al. (2021) description. Days to silique development (DTSD) was recorded as a number of days from the sowing to the time that first pods appeared on 50% of the plants. Days to ripening (DTR) was measured as the interval between the dates of sowing and the time when pods were dried. Plant height (PH) (cm) was recorded from the ground to the tip of the main pod at the ripening stage. For branch number/plant (BNPP) and yield components including silique length (SL; cm), seed number/silique (SNPS), seed weight/plant (SWPP; g), and thousand seed weight (THSW; g), 10 randomly plants were harvested from the middle rows to avoid border effects in each plot. At the harvesting time, plants in two middle rows were cut for plant weight (PW; g), seed yield (SY; kg ha−1), and harvest index (HI; %) measurements. The grain weight of 10 spikes was used as grain weight per spike. The HI was calculated by dividing the grain yield by the biological yield.

2.3. Analysis of variance and estimation of genetic variation and genetic gain

Descriptive parameters including mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for each treatment in SAS software (version 9.4). Box and whisker plots were used for the graphical presentation of the descriptive statistics. The packages ggplot2 in R (version 4.3.2) for win (http://CRAN.R-project.org/, accessed on 23 February 2021) and RStudio (version 1.3.1093) (https://rstudio.com/, accessed on 23 February 2021) were used for analysis of boxplots (McGill et al., 1978; Wickham, 2016). The correlation matrix between variables and a constructing heat map of correlation coefficients were computed using packages plotly, heatmaply, and ggcorrplot (https://cran.rproject.org/web/packages/ggcorrplot/index.html) in the R software.

The PROC GLM procedure was used for combined analysis of variances (ANOVA) in the Statistical Analysis System (SAS) software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA, version 9.3) (Dodig et al., 2008). The RANDOM statement with the TEST as option procedure was used to define the year as a random effect and water treatment and genotype as fix effects in ANOVA.

Phenotypic and genotypic variances were calculated as shown in Equation 1 using the expected mean squares (EMS) of sources of variations in ANOVA as follows (Lush, 1949),

| (1) |

where is the genotypic variance, MSG is the mean square for genotype, MSE is the error mean square in ANOVA, and r is the number of replications.

| (2) |

where and are the phenotypic and environmental variances, respectively (Equation 2).

The environmental, genotypic, and phenotypic coefficients of variation were calculated as shown in Equations 3, 4, and 5 using as follows (Burton, 1952):

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

where ECV is the environmental coefficient of variation, GCV is the genotypic coefficient of variation, PCV is the phenotypic coefficient of variation, is the root of genotypic variance, is the root of phenotypic variance, and x̅ is the trait mean.

Variance components were used to calculate the broad-sense heritability ( ) in Equation 6 as follows (Marwede et al., 2004):

| (6) |

Simple genetic advance (GA) and GA over means (GAM) were calculated as shown in Equations 7 and 8 as follows::

| (7) |

| (8) |

where k is the selection intensity which was 1.76 denoting selection of 10% of top-ranked varieties, is heritability in a broad sense, and x̅ is the trait mean.

2.4. Reference mapping and variant calling

Pseudo-genome sequences of the diploid A (283.8 Mb) and C genomes (488.6 Mb) were combined and used as the reference sequences for mapping analyses. Reads for each genotype were aligned independently to the reference genome using CLC Genomics Workbench (version 7.0.4). The mapped reads were interrogated for sequence variation using the CLC Bio probabilistic variant calling tool. A minimum depth of coverage of 3× for 454 and 8× for Illumina data was required for SNP calling. Mapping data and variant calls were exported from CLC and combined using a custom Perl script to determine reference, or variant call for every genotype at all variant positions.

2.5. DNA extraction and single SNP-based association mapping

Genomic DNA was isolated from the fresh leaves collected from a bulk of five randomly chosen plants per variety in a greenhouse (Murray and Thompson, 1980). The genomic DNA was quantified using a NanoDrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Inc., Wilmington, DE, United States). The DNA samples were used for genotyping Brassica 60 K Infinium array as described in the manufacturer’s protocol (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA). Quality preprocessing of 52,157 SNPs obtained from 60K chips was done by using TASSEL software v5 (Bradbury et al., 2007). The SNPs were filtered for site coverage (90%), minimum minor allele frequency (MAF) of 0.05 with only biallelic markers, and low rates of missing data (≤10%) using the TASSEL (version 5).

2.6. Population genetics analysis, linkage disequilibrium, and LD decay

The polymorphism information content (PIC) value of each SNP locus in all varieties and the PIC values on each chromosome were calculated by PowerMarker (version 3.2.5) (Liu and Muse, 2005). We generated 29,310 SNPs involving 119 varieties derived from Iran, Germany, France, America, Australia, Hungary, Serbia, and Russia ( Additional File 1 ). For population structure analysis, the natural logarithms of probability data (LnP(K)) and the ad hoc statistic ΔK were calculated (Su et al., 2017). The population structure underlying the collection of rapeseed varieties was analyzed using STRUCTURE (version 2.3.4) (Hubisz et al., 2009). The model-based Bayesian cluster analysis program was used to identify subpopulations. A total 10,000 burn-in periods followed by 100,000 Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) iterations from K = 3 to K = 10 were used to identify the optimal number of clusters (K). Three independent runs were generated for each K. The results were collated by the Structure Harvester tool (Earl and VonHoldt, 2011), and the best K-value was identified based on the delta K method (Evanno et al., 2005). A neighbor-joining (NJ) tree was created to validate population stratification with the software TASSEL (version 5). A PCA was done on the significant SNPs data using R software (version 4.3.2) (R Core Team, 2018) with the ggplot2 (Wickham, 2016) and ape (Paradis and Schliep, 2018) packages, respectively. To investigate chromosome-wide and the genome-specific patterns of linkage disequilibrium (LD) (r2 ), the software TASSEL (version 5) (www.maizegenetics.net/) with 1000 permutations was used. After quality control processing, a total of 29,310 high-quality SNPs with MAF ≥0.05 and pairwise r2 values were used to determine the extent of LD decay across genome and among chromosomes.

2.7. Genome-wide association analysis

The marker–trait associations (MTAs) were analyzed using the program TASSEL (version 5). Four models, namely, general linear model (GLM) with the Q matrix of population structure (GLM + Q), mixed linear model (MLM) with both the kinship (K) as a random effect and Q matrices (MLM + Q), GLM model with the major principal components (PC) matrix (GLM + PC) and MLM with both the PC and K matrices (MLM + K + PC), were used to identify the MTAs. In GWAS, five PCs based on their cumulative eigenvalue contribution were used in population structure analysis. The Q matrix obtained from structure analysis and the relative kinship and PC matrices were calculated by TASSEL software. The phenotypic variation explained by significant SNP marker (R2 ) was calculated in TASSEL (version 5) (Bradbury et al., 2007). Quantile–quantile (QQ) plots were shown with −log10(P) of each SNP and expected P-value using the R package qqman (https://cran.rproject.org/web/packages/qqman/index.html). Manhattan plots were drawn in TASSEL software.

2.8. Screening candidate genes overlapped with the SNP position

To identify candidate genes (CGs) related to the SNPs of traits under the well-watered and drought-stressed conditions, the flanking sequences of the linked SNPs obtained from the “Darmor-bzh” reference genome (http://www.genoscope.cns.fr/brassicanapus/data/) was used to search in the rapeseed genome by Ensembl Plants (https://plants.ensembl.org/). Consequently, all the genes underlying the genomic region of each SNPs were functionally annotated by Ensembl Plants (https://plants.ensembl.org/) and online resources (https://genome.ucsc.edu/ and https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The CGs were identified based on their putative function in rapeseed or closely related species.

2.9. Allele effect and haplotype analyses

The allele effects for the linked significant SNPs were analyzed as previously described by Alemu et al. (2021). Varieties were divided into two different groups according to their specific SNP alleles, and the means were compared using Turkey’s honest significant difference (HSD) test. Exploring and harnessing haplotype diversity helps in the detection of CGs for improvement of target traits in crops (Qian et al., 2017). A haplotype association test was performed to investigate the combined effect of the linked significant SNPs. The SNPs in the same haploblock and the LD of significant SNPs were determined using Haploview (version 4.2) (Barrett et al., 2005). A standardized disequilibrium coefficient (D′) was used to evaluate the LD between markers and generate the LD heatmap. Haploid blocks were detected based on LD using the confidence intervals (CI) method in Haploview (version 4.2) (Gabriel et al., 2002).

2.10. RNA extraction, library construction, and RNA-sequencing

To validate the GWAS-identified SNPs contributed to drought tolerance, the expression of candidate genes associated with the position of the related SNPs was analyzed in two drought-tolerant and two drought-sensitive varieties. The experiment consisted of the RNA-Seq analysis in two top high- (G19 and G41) and two top low- (G111 and G114) yielding varieties showing contrasting yield under the WW and DS conditions. The plants were grown in 20-cm-diameter pots in the greenhouse under 12-h light/12-h dark conditions with normal experimental management. There were six plants in each pot. When the flower buds became visible, plants were randomly divided into two groups, each with three plants: the control group and the drought stress treatment group and each experiment underwent three biological replicates. During irrigation, drought-treated flower pots maintain a soil moisture content of 10% (irrigated with PEG6000 at a concentration of 20%), whereas well-watered flower pots maintain a soil moisture content of 30% (irrigated with sterile water of equal volume). Thirty days after flowering, the leaf and mature seeds were harvested from plants in each replicate group and each condition (the well-watered and drought stress treatments). All harvested seeds and leaves were immediately frozen using liquid nitrogen and transferred to a deep freezer (−80°C) for storage.

A total of 24 samples (control and treatments with three biological replicates, respectively) were prepared for RNA-Seq. Total RNA was extracted from the seeds and leaves using a Plant RNA Mini Kit (Tiangen, Inc., China) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Four cDNA libraries were constructed, and RNA-Seq was performed on a DNBSEQ-G400 platform.

Low-quality reads were filtered out using the NGS QC toolkit (version 2.2.3) (https://omictools.com/ngs-qc-toolkit-tool) (Patel and Jain, 2012). High-quality reads from the raw sequencing reads were matched to the B. napus reference genome of “Darmor-bzh” (http://www.genoscope.cns.fr/brassicanapus/). The identified genes in the previous step were quantitatively analyzed using Cluffquant and Cluffnorm of Cufflinks 2.0.0 (http://cole-trapnell-lab.github.io/cufflinks/releases/v2.0.0/).

2.11. Identification of differentially expressed genes

The DEGs were identified based on FPKM (fragments per kilo base of transcript per million mapped fragment) and Q value (<0.05) (Q value: error-corrected value after multiple testing), and a log2 (fold change) ≥1 was set as the threshold to identify the significance of gene expression differences. Furthermore, to verify the statistical significance and hierarchical clustering of DEGs, a heat map was generated using R software (version 4.3.2).

2.12. Enrichment analyses of Gene Ontology and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathways

To further understand the function of DEGs, we performed Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and Gene Ontology (GO) analyses on the identified DEGs. The sequence file of each gene was used as input into Eggnog software (version 2.0.1) to identify annotation of genes (Huerta-Cepas et al., 2017). GO and KEGG analyses were conducted using the ClusterProfiler (version 4.0.0) R package. Only GO terms or KEGG pathways with P-value <0.05 verified for subsequent analyses. The REVIGO program (http://revigo.irb.hr/) was used to remove redundant GO terms (Supek et al., 2011).

2.13. Integration of genome-wide association study and transcriptome data

The RNA‐seq data were used for the ratios of genome‐wide up‐ and downregulated DEGs. In addition, we calculated the ratios of up‐ and downregulated DEGs within the 288-kbp intervals corresponding to the significant SNPs of the GWAS analysis. Then, we compared the DEG ratios for all genome‐wide genes and for potential drought tolerance-related genes detected in the GWAS of the high- and low-yield contrasting varieties under drought stress.

3. Results

3.1. Phenotypic variation and heritability of traits

The results of ANOVA for the main effects of treatments and the interactions are shown in Additional File 3 . The effects of year (Y), environment (E), and genotype (G) were statistically significant (P-value < 0.01), which shows variation among varieties for traits over years and irrigation treatments. The G × Y, G × E, Y × E, and Y × G × E interactions were significant for all traits. Phenotypic variation for traits under normal irrigation and drought stress conditions is shown in Table 1 ; Figures 1A–M . The results showed that PW, SWPP, HI, and SY had high variation among the 119 rapeseed varieties in two irrigation regimes.

Table 1.

Phenotypic variation of agronomic and yield related traits in 119 rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) varieties.

| Trait | Watering regime | Mean | SD | Min | Max | ECV (%) | PCV (%) | GCV (%) | h2 (%) | GA | GAM (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DTF | WW17 | 183.01 | 5.82 | 168 | 189 | 2.66 | 3.18 | 4.15 | 58.73 | 7.84 | 4.29 |

| DS17 | 186.00 | 6.34 | 171 | 192 | 1.20 | 3.39 | 3.59 | 88.91 | 10.45 | 5.62 | |

| WW18 | 180.64 | 3.57 | 171 | 188 | 0.89 | 1.98 | 2.17 | 83.26 | 5.74 | 3.18 | |

| DS18 | 180.62 | 4.13 | 166 | 187 | 0.48 | 2.23 | 2.28 | 95.65 | 6.93 | 3.83 | |

| WW20 | 183.54 | 9.03 | 171 | 201 | 0.54 | 4.95 | 4.98 | 98.82 | 15.91 | 8.67 | |

| DS20 | 184.89 | 9.14 | 172 | 202 | 0.83 | 4.98 | 5.05 | 97.31 | 16.00 | 8.65 | |

| DTSD | WW17 | 190.73 | 4.97 | 179 | 197 | 2.02 | 2.56 | 3.26 | 61.70 | 6.75 | 3.54 |

| DS17 | 193.04 | 5.81 | 182 | 190 | 1.15 | 3.01 | 3.22 | 87.19 | 9.54 | 4.94 | |

| WW18 | 187.73 | 3.18 | 179 | 198 | 0.56 | 1.67 | 1.76 | 89.81 | 5.22 | 2.78 | |

| DS18 | 186.88 | 3.45 | 173 | 195 | 0.55 | 1.79 | 1.87 | 91.39 | 5.62 | 3.01 | |

| WW20 | 192.47 | 10.02 | 179 | 213 | 0.92 | 5.22 | 5.30 | 96.97 | 17.40 | 9.04 | |

| DS20 | 193.72 | 9.71 | 181 | 212 | 0.95 | 5.01 | 5.10 | 96.52 | 16.77 | 8.66 | |

| DTR | WW17 | 256.84 | 2.27 | 253 | 273 | 0.79 | 0.87 | 1.17 | 54.99 | 2.91 | 1.13 |

| DS17 | 255.31 | 2.15 | 252 | 262 | 0.56 | 0.84 | 1.01 | 69.02 | 3.12 | 1.22 | |

| WW18 | 268.80 | 1.46 | 266 | 274 | 0.42 | 0.54 | 0.68 | 62.46 | 2.01 | 0.75 | |

| DS18 | 267.80 | 1.28 | 265 | 271 | 0.39 | 0.48 | 0.61 | 60.14 | 1.74 | 0.65 | |

| WW20 | 278.58 | 4.84 | 265 | 289 | 0.33 | 1.75 | 1.78 | 96.64 | 8.41 | 3.02 | |

| DS20 | 272.82 | 5.60 | 254 | 285 | 0.28 | 2.03 | 2.05 | 98.14 | 9.64 | 3.53 | |

| PH | WW17 | 108.20 | 19.35 | 41.33 | 157.55 | 6.11 | 18.04 | 19.05 | 89.73 | 32.55 | 30.08 |

| DS17 | 86.58 | 14.25 | 61.14 | 141.33 | 12.16 | 16.56 | 20.54 | 64.97 | 20.33 | 23.49 | |

| WW18 | 178.24 | 2.37 | 123.45 | 141.33 | 0.84 | 0.78 | 1.15 | 46.38 | 2.80 | 0.94 | |

| DS18 | 170.60 | 5.09 | 111.11 | 130.45 | 1.06 | 1.77 | 2.06 | 73.47 | 7.74 | 2.67 | |

| WW20 | 142.31 | 12.50 | 113.34 | 173.12 | 2.09 | 8.81 | 9.05 | 94.69 | 21.47 | 15.09 | |

| DS20 | 122.21 | 8.80 | 100.43 | 154.32 | 2.15 | 7.18 | 7.50 | 91.80 | 14.81 | 12.11 | |

| BNPP | WW17 | 84.21 | 9.92 | 29 | 92 | 7.09 | 11.76 | 13.73 | 73.31 | 14.92 | 17.72 |

| DS17 | 28.10 | 4.16 | 23 | 47 | 8.19 | 14.69 | 16.82 | 76.28 | 6.35 | 22.58 | |

| WW18 | 168.53 | 12.20 | 125 | 193 | 4.70 | 7.37 | 8.75 | 71.06 | 18.43 | 10.94 | |

| DS18 | 143.06 | 12.13 | 115 | 172 | 4.75 | 8.55 | 9.78 | 76.43 | 18.83 | 13.16 | |

| WW20 | 181.23 | 12.35 | 149 | 218 | 1.85 | 6.94 | 7.18 | 93.34 | 21.39 | 11.80 | |

| DS20 | 156.10 | 10.48 | 129 | 186 | 2.58 | 6.66 | 7.15 | 86.96 | 17.07 | 10.94 | |

| PW | WW17 | 1,599.65 | 543.50 | 575.76 | 3,575.42 | 27.57 | 33.64 | 43.50 | 59.82 | 732.57 | 45.80 |

| DS17 | 472.43 | 256.80 | 120.45 | 1,535.34 | 41.01 | 53.89 | 67.72 | 63.33 | 356.62 | 75.49 | |

| WW18 | 2,421.35 | 530.42 | 665.45 | 3,900.32 | 13.29 | 21.93 | 25.64 | 73.14 | 799.14 | 33.00 | |

| DS18 | 2,302.02 | 480.84 | 345.42 | 3,395.33 | 13 | 20.73 | 24.47 | 71.77 | 711.41 | 30.90 | |

| WW20 | 2,726.34 | 589.07 | 835.24 | 4,130.35 | 11.95 | 21.65 | 24.73 | 76.66 | 909.55 | 33.36 | |

| DS20 | 1,818.87 | 456.85 | 865.32 | 3,195.46 | 19.35 | 25.12 | 31.71 | 62.75 | 636.94 | 35.02 | |

| SL | WW17 | 7.87 | 0.85 | 5.32 | 10.33 | 7.23 | 10.68 | 12.89 | 68.55 | 1.22 | 15.56 |

| DS17 | 7.81 | 0.89 | 6.14 | 10.33 | 4.18 | 17.45 | 17.94 | 94.56 | 2.33 | 29.86 | |

| WW18 | 6.85 | 0.83 | 5.21 | 9.53 | 2.98 | 11.05 | 11.45 | 93.23 | 1.29 | 18.78 | |

| DS18 | 6.69 | 0.64 | 5.32 | 9.50 | 3.75 | 8.37 | 9.17 | 83.26 | 0.90 | 13.44 | |

| WW20 | 7.10 | 0.99 | 5.12 | 9.32 | 1.99 | 12.76 | 12.91 | 97.63 | 1.58 | 22.18 | |

| DS20 | 6.44 | 0.90 | 4.52 | 9.39 | 2.71 | 12.96 | 13.24 | 95.81 | 1.44 | 22.32 | |

| SNPS | WW17 | 23.53 | 3.82 | 19 | 32 | 4.55 | 16.19 | 16.82 | 92.68 | 6.46 | 27.44 |

| DS17 | 24.50 | 4.08 | 17 | 39 | 2.19 | 16.65 | 16.79 | 98.30 | 7.12 | 29.06 | |

| WW18 | 20.52 | 4.49 | 11 | 31 | 1.97 | 21.68 | 21.77 | 99.18 | 7.80 | 38.00 | |

| DS18 | 19.73 | 4.47 | 11 | 31 | 11.15 | 22.56 | 25.16 | 80.38 | 7.02 | 35.60 | |

| WW20 | 23.40 | 4.93 | 11 | 36 | 2.63 | 20.82 | 20.98 | 98.43 | 8.51 | 36.35 | |

| DS20 | 22.05 | 4.56 | 11 | 39 | 2.47 | 20.59 | 20.74 | 98.58 | 7.93 | 35.97 | |

| SWPP | WW17 | 155.71 | 79.35 | 20.33 | 398.45 | 72.79 | 51.25 | 89.02 | 33.15 | 80.87 | 51.93 |

| DS17 | 35.24 | 16.84 | 12.45 | 122.38 | 64.98 | 47.97 | 80.77 | 35.28 | 17.67 | 50.15 | |

| WW18 | 135.47 | 38.37 | 50.22 | 235.25 | 29.71 | 28.62 | 41.25 | 48.14 | 47.35 | 34.95 | |

| DS18 | 109.01 | 39.86 | 33.11 | 219.42 | 34.88 | 36.60 | 50.56 | 52.41 | 50.84 | 46.63 | |

| WW20 | 511.78 | 143.88 | 125.43 | 845.30 | 23.05 | 27.98 | 36.25 | 59.58 | 194.53 | 38.01 | |

| DS20 | 120.03 | 71.82 | 30.54 | 375.64 | 54.77 | 59.44 | 80.83 | 54.08 | 92.34 | 76.93 | |

| THSW | WW17 | 2.93 | 1.07 | 1.32 | 6.11 | 31.29 | 35.36 | 47.22 | 56.09 | 1.37 | 46.62 |

| DS17 | 2.10 | 0.85 | 1.24 | 4.39 | 20.19 | 40.78 | 45.50 | 80.32 | 1.35 | 64.32 | |

| WW18 | 3.48 | 0.68 | 1.09 | 4.89 | 7.79 | 18.10 | 19.70 | 84.38 | 1.02 | 29.26 | |

| DS18 | 2.05 | 0.65 | 1.05 | 3.97 | 20.30 | 26.86 | 33.67 | 63.64 | 0.77 | 37.71 | |

| WW20 | 4.57 | 0.57 | 2.36 | 6.43 | 2.60 | 10.20 | 10.53 | 93.89 | 0.79 | 17.40 | |

| DS20 | 4.32 | 0.59 | 2.15 | 7.42 | 2.81 | 10.80 | 11.16 | 93.67 | 0.79 | 18.40 | |

| HI | WW17 | 10.91 | 6.55 | 1.32 | 32.34 | 51.86 | 9.5 | 52.73 | 3.24 | 0.33 | 3.01 |

| DS17 | 8.53 | 3.43 | 3.76 | 21.46 | 50.98 | 39.84 | 64.70 | 37.91 | 3.68 | 43.17 | |

| WW18 | 5.78 | 1.75 | 3.31 | 13.17 | 34.31 | 30.09 | 45.63 | 43.48 | 2.02 | 34.92 | |

| DS18 | 4.88 | 1.87 | 2.70 | 15.75 | 40.95 | 37.74 | 55.69 | 45.92 | 2.20 | 45.01 | |

| WW20 | 18.73 | 3.33 | 7.45 | 27.33 | 21.39 | 17.64 | 27.72 | 40.48 | 3.70 | 19.75 | |

| DS20 | 6.39 | 2.70 | 2.45 | 16.35 | 46.58 | 41.3 | 62.26 | 44.01 | 3.08 | 48.22 | |

| SY | WW17 | 2,594.18 | 1,096.08 | 396.34 | 7,666.34 | 25.77 | 42.10 | 49.36 | 72.74 | 1,639.3 | 63.19 |

| DS17 | 1,918.77 | 986.37 | 630.71 | 7,378.25 | 45.85 | 57.09 | 73.22 | 60.79 | 1503.2 | 78.34 | |

| WW18 | 1,352.23 | 383.93 | 500.22 | 2,350.21 | 24.32 | 28.67 | 37.60 | 58.16 | 520.46 | 38.49 | |

| DS18 | 1,088.11 | 398.32 | 330.32 | 2,190.25 | 30.76 | 36.72 | 47.90 | 58.77 | 539.12 | 49.55 | |

| WW20 | 5,125.42 | 1,443.27 | 1,250.37 | 8,450.23 | 18.61 | 28.02 | 33.64 | 69.41 | 2,106.05 | 41.09 | |

| DS20 | 1,200.34 | 718.25 | 300.34 | 3,750.25 | 42.13 | 59.44 | 72.85 | 66.55 | 1,024.36 | 85.34 |

DTF, DTSD, DTR, PH, BNPP, PW, SL, SNPS, SWPP, THSW, HI, and SY are the abbreviations of days to flowering, days to silique development, days to ripening, plant height, branch number/plant, plant weight, silique length, seed number/silique, seed weight/plant, thousand seed weight, harvest index, and seed yield, respectively. WW17, DS17, WW18, DS18, WW20, and DS20 are the codes of the two watering regimes during 3 years: well-watered in 2017, drought stress in 2017, well-watered in 2018, drought stress in 2018, well-watered in 2020, and drought stress in 2020. SD, ECV, PCV, GCV, h2, GA, and GAM are the abbreviations of standard deviation, environmental coefficient of variation, phenotypic coefficient of variation, genotypic coefficient of variation, heritability in the broad sense, genetic advance, and genetic advance as the percentage of the mean of the studied traits at two watering regimes under 3 years.

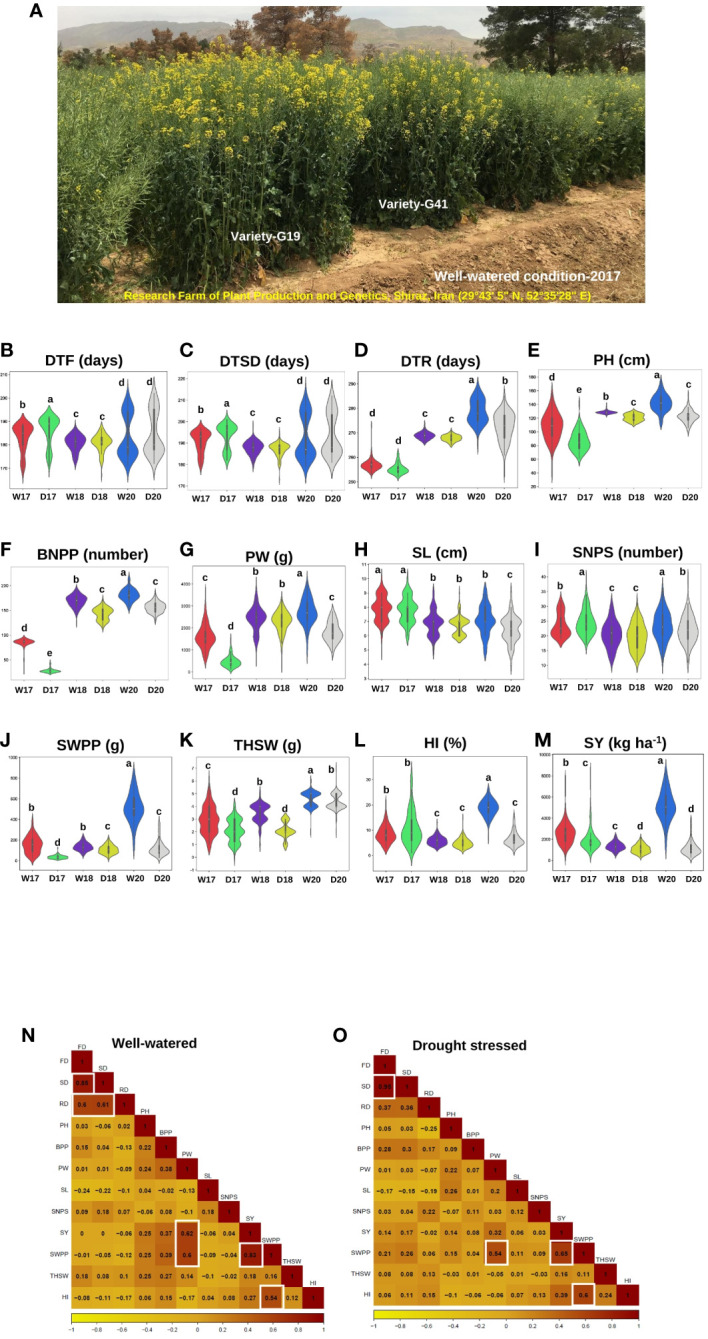

Figure 1.

Agronomic and yield-related traits phenotyping in rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) varieties under two watering regimes (well-watered and drought stress conditions) across three years, 2017, 2018, and 2020. (A) A diverse collection of rapeseed varieties was assessed for agronomic and yield-related traits under well-watered conditions in 2017 in Research Farm of Plant Production and Genetics, Shiraz, Iran (29°43′ 5″ N, 52° 35′28″ E), highlighting the range of phenotypic diversity within the panel. G19 and G41 were high-yield varieties. (B-M) The violin plots illustrating the changes in agronomic and yield-related traits under well-watered and drought stress conditions from the individual data sets of 3 years (2017, 2018, and 2020) of 119 rapeseed varieties. The width of the violin plot represents the density of the distribution. The white dot in the box plot shows the median value, and the upper and lower boxes in the box represent the upper and lower quartiles of the data set. Data are means ± SD, P-value < 0.05, as determined by multiple comparison testing by one-way ANOVA. Traits represent as (B) days to flowering (DTF), (C) days to silique development (DTSD), (D) days to ripening (DTR), (E) plant height (PH), and (F) branch number/plant (BNPP), (G) plant weight (PW), (H) silique length (SL), (I) seed number/silique (SNPS), (J) seed weight/plant (SWPP), (K) thousand seed weight (THSW), (L) harvest index (HI), and (M) seed yield (SY). WW17, DS17, WW18, DS18, WW20, and DS20 were the codes of the two watering regimes during 3 years: well-watered in 2017, drought stress in 2017, well-watered in 2018, drought stress in 2018, well-watered in 2020, and drought stress in 2020, respectively. (N, O) Heat map showing the correlation between the agronomic and yield-related traits under two watering regimes in three growing seasons (2017, 2018, and 2020). (N) Well-watered condition, (O) drought stress condition. Traits represent as flowering date (FD), silique date (SD), ripening date (RD), plant height (PH), branches per plant (BPP), plant weight (PW), silique length (SL), seed number/silique (SNPS), seed yield (SY), seed weight/plant (SWPP), thousand seed weight (THSW), and harvest index (HI). A color scale showing the correlation values ranging from dark yellow, −1, to orange, 0, to 1, dark red is shown below the heat map.

The SWPP, SY, HI, and PW traits showed significant differences between normal irrigation and drought stress conditions. Compared with normal irrigation, drought stress significantly reduced SWPP, SY, HI, PW, BNPP, THSW, PH, SL, SNPS, and DTR by 67.08%, 53.62%, 44.09%, 44.09%, 31.92%, 24.58%, 22.85%, 11.51%, 4.03%, 1.73%, and 1.03%, respectively ( Table 1 ; Supplementary Figure S2 ).

Analysis of genetic variation showed that the traits were divided into three groups with PCV and GCV above 20% as high, 10%–20% as moderate, and below 10% as low ( Table 1 ). In normal irrigation conditions, SWPP, SY, and PW had high PCV and GCV in 3 years ( Table 1 ). Moderate PCV and GCV were recorded for SL and SNPS in 3 years. The DTF, DTSD, and DTR traits in 3 years and PH and BNPP in two years showed low PCV and GCVs ( Table 1 ). Under drought conditions, the PCV estimates of various characters varied from 0.48% for DTR to 51.08% for SY and SWPP ( Table 1 ). The GCV estimates varied from 0.61% for DTR to 80.77% for SWPP. Both GCV and PCV were high (>20%) for PW, SY, SWPP, and HI in 3 years and for SNPS in 2018 and 2020, THSW in 2017 and 2018. DTF, DTSD, and DTR had lower variation (<6%) in drought stress condition in 3 years.

Heritability estimates for most of the traits were higher under drought compared with well-watered conditions. The heritability estimates for traits in the WW condition ranged from 3.24% for HI to 99.18% for SNPS and from 35.28% for SWPP to 99.18% for SNPS in drought stress. The estimates of heritability were moderate for PW and SY in 3 years ( Table 1 ). Genetic advances (GA) ranged from 0.33 for HI to 2106.05 for SY in normal irrigation conditions, and it ranged from 0.77 for THSW to 1503.2 for SY in drought stress. High heritability values coupled with high GA were recorded for PW, SWPP, and SY under well-watered conditions in three growing seasons. Genetic advance normalized based on the trait mean (GAM) under well-watered conditions ranged from 63.19% for SY to 0.75% for DTR and from 0.65% for DTR to 85.34% for SY in drought stress. Among the tested traits, SNPS showed high heritability (>80%) coupled with the high GAM (>20%) under both irrigation conditions across 3 years.

3.2. Interrelationship of agronomic and yield-related traits

Analysis of correlation of traits helps in indirect selection for yield improvement. Under WW conditions, significant and relatively high correlations were identified for DTF with DTSD and DTR (0.85**, 0.60**) and DTR with DTSD (0.61**) ( Figure 1N ). Correlations of SY with PW (0.62**) and SWPP (0.83**) were significant. Under drought conditions, a positive and significant correlation coefficient was found for SWPP with each SY, HI, and PW traits (0.65**, 0.60**, and 0.54**) whereas DTSD had a strong positive correlation (0.95**) with DTF ( Figure 1O ).

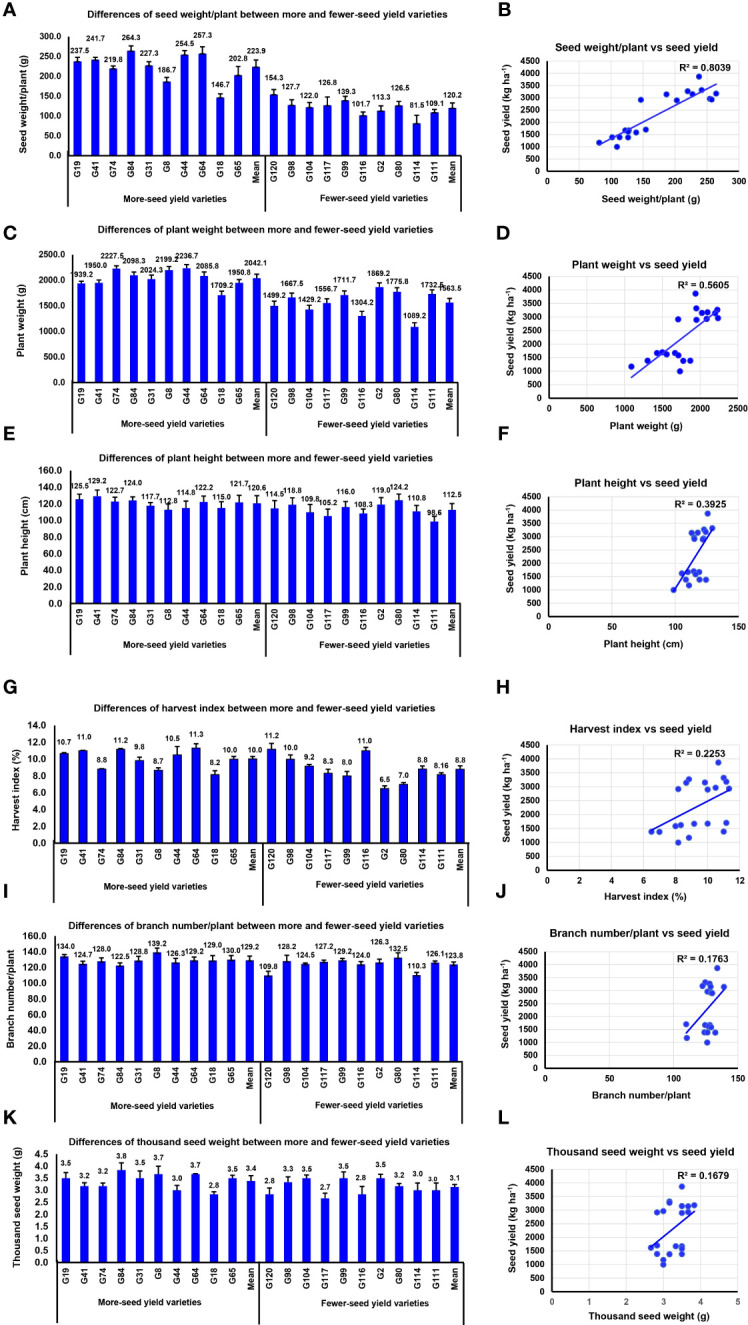

3.3. Morphological variations between high- and low-yield varieties

Owing to the lower complexity of yield components and lower influence of environmental effects compared with yield, use of yield-related traits with high heritability as indirect selection for improvement of grain yield is preferred. We assessed the difference of agronomic traits and yield components in the high- and low-grain yield varieties. The results indicated that BNPP, SWPP, and PW were significantly larger in the high-yield varieties than in the low-yield varieties (P-value < 0.01**). However, PH, THSW, and HI were relatively similar between the two contrasting groups ( Figures 2A–L ).

Figure 2.

The seed yield variation was caused by agronomic and yield components. (A) Differences of seed weight/plant between high- and low-yield varieties. (B) Correlation analysis between seed yield and seed weight/plant. (C) Differences of plant weight between high- and low-yield varieties. (D) Correlation analysis between seed yield and plant weight. (E) Differences of plant height between high- and low-yield varieties. (F) Correlation analysis between seed yield and plant height. (G) Differences of harvest index between high- and low-yield varieties. (H) Correlation analysis between seed yield and harvest index. (I) Differences of branch number/plant between high- and low-yield varieties. (J) Correlation analysis between seed yield and branch number/plant. (K) Differences of thousand seed weight between high- and low-yield varieties. (L) Correlation analysis between seed yield and thousand seed weight.

3.4. Distribution of SNPs, LD, LD decay, and population structure

After filtering low-quality SNPs (call rate <90% and minor allele frequency <0.05) in TASSEL software, a set of 29,310 high-quality SNPs was used for genetic variation and GWAS analyses. The SNP markers were not evenly distributed across the whole genome with the A subgenome having a higher number of SNP markers (14,925; 50.92%) compared to the C subgenomes ( Supplementary Figures S3A, D ). However, the density of SNPs in the C subgenome (42.96 SNPs/kbps) was higher than that in the A subgenome (19.76 SNPs/kbps) ( Additional File 4 ). Among all chromosomes, C04 (2,624 SNPs) and C05 (723 SNPs) had the highest and lowest numbers of markers ( Supplementary Figure S3A ). The PIC values for chromosome ranged from 0.24 to 0.38 ( Additional File 4 ). The mean PIC values of the A and C subgenomes were 0.32 and 0.32, respectively.

Linkage disequilibrium was examined as the squared Pearson correlation coefficient (r2 ) between all pairs of SNP markers. The LD in the C subgenome was significantly higher LD (0.031) than in the A subgenome (0.025). The C05 chromosome showed the highest LD (0.088) among chromosomes ( Additional File 4 ). The LD decay with an average of 288 kbps in the whole genome ranged from 101.61 in A10 to 953.78 kbps in A08. However, the LD decay distance for C03 was 942.6 kbps, which was large compared with those for other chromosomes in the C subgenome ( Additional File 4 ).

In analysis of population structure, the peak of the broken line was observed at k = 7 suggesting that the tested population can be divided into seven distinct groups and one mixed group partly correlated with their origins ( Supplementary Figure S3B ). Neighbor-joining (NJ) cluster analysis was performed to explore the relatedness among the rapeseed varieties. The NJ tree showed that our varieties could be divided into four groups ( Supplementary Figure S3C ). The first group (group A) was composed of 30 breeding lines originated from Iran and Australia, group B was composed of 10 varieties from Iran and Germany, 55 breeding lines in group C originated from Iran, and Group D had 24 varieties composed of hybrids and cultivars originated in France and America. The PCA based on the genome-wide SNPs supported the results of population structure and phylogenetic tree ( Supplementary Figure S3E ).

3.5. Significant SNPs and candidate genes associated with traits

We measured 12 traits including plant architecture, phenological and agronomic traits, and yield components in 119 rapeseed varieties grown under two irrigation conditions over 3 years. Using 29,310 high-quality SNPs, our GWAS for these 12 traits revealed 1,281 unique SNPs linked with the traits at the P-value < 10−4 threshold ( Supplementary Figures S3F , S4 - S6 ; Additional Files 5 - 8 ). Higher numbers of significant SNPs associated with traits were identified in the GLM + Q and MLM + K + PC models. However, the result of the MLM model was preferred, which showed fewer false positives than the GLM model. False positives are often controlled by incorporating covariates for the kinship and PCs matrices in the MLM model (Liu et al., 2016). Accordingly, the results of the MLM + K + PC model were used for further analysis. The number of significant SNPs linked with traits was variable. Higher SNPs were found for the DTF, BNPP, and SY traits than others. Based on statistical significance and the repeatability of the linked SNPs in two irrigation treatments across years, several important SNPs are shown in Tables 2 , 3 . Generally, the effective candidate regions with significant GWAS signals were defined as the LD blocks surrounding the signal peak (Yano et al., 2016). Based on the 288-kbps LD decay distance and CG analysis, we identified 2,232 genes as GWAS-associated CGs ( Additional Files 9 , 10 ). The SNPS (557) trait followed by DTF (524) showed the highest number of CGs. The key genes related to four agronomically important traits were selected for further functional verifications.

Table 2.

Repetitive significant SNP in the current study.

| 2017 | 2018 | 2020 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traits | SNP name | Chr | Position | WW | DS | WW | DS | WW | DS |

| DTF | Bn-A04-p1865434 | A04 | 1588506 | ns | 4.67E-04 | ns | 9.61E-04 | ns | ns |

| Bn-A04-p2568394 | A04 | 2279208 | ns | 3.62E-04 | ns | 8.59E-05 | ns | ns | |

| Bn-A10-p15330596 | A10 | 16164284 | ns | 4.46E-04 | ns | 9.33E-04 | ns | ns | |

| Bn-A10-p15361519 | A10 | 16139771 | ns | 2.15E-05 | ns | 8.88E-04 | ns | ns | |

| Bn-A10-p15405149 | A10 | 16091976 | ns | 1.37E-04 | ns | 4.87E-04 | ns | ns | |

| Bn-A10-p15542820 | A10 | 222927 | 1.77E-04 | 2.80E-04 | ns | 9.52E-04 | ns | ns | |

| Bn-A10-p7252424 | A10 | 8893827 | ns | 4.81E-04 | ns | 6.67E-05 | ns | ns | |

| Bn-A10-p7347530 | A10 | 8998128 | ns | 5.02E-04 | ns | 1.94E-04 | ns | ns | |

| Bn-scaff_22728_1-p744551 | C03 | 5904544 | ns | 9.02E-04 | ns | 2.97E-04 | ns | ns | |

| THSW | Bn-scaff_15818_1-p427676 | C06 | 15724425 | ns | ns | ns | 4.40E-04 | 1.60E-04 | 2.40E-04 |

| Bn-scaff_15818_1-p453625 | C06 | 15751833 | ns | ns | ns | 4.40E-04 | 1.60E-04 | 2.40E-04 | |

| Bn-scaff_15818_1-p469375 | C06 | 15766868 | ns | ns | ns | 4.40E-04 | 1.60E-04 | 2.40E-04 | |

| Bn-scaff_15818_1-p471106 | C06 | 15768599 | ns | ns | ns | 4.40E-04 | 1.60E-04 | 2.40E-04 | |

| Bn-scaff_18702_1-p263991 | C02 | 16251517 | ns | ns | ns | 5.53E-04 | 7.18E-04 | 9.53E-04 | |

| Bn-scaff_18702_1-p270197 | C02 | 16260356 | ns | ns | ns | 5.53E-04 | 7.18E-04 | 9.53E-04 | |

| Bn-scaff_18702_1-p288731 | C02 | 16279001 | ns | ns | ns | 5.53E-04 | 7.18E-04 | 9.53E-04 | |

| Bn-scaff_18702_1-p323368 | C02 | 16314729 | ns | ns | ns | 5.53E-04 | 7.18E-04 | 9.53E-04 | |

| Bn-scaff_18702_1-p361232 | C02 | 16355013 | ns | ns | ns | 5.53E-04 | 7.18E-04 | 9.53E-04 | |

| Bn-scaff_18702_1-p365839 | C02 | 16359619 | ns | ns | ns | 5.53E-04 | 7.18E-04 | 9.53E-04 | |

DTF and THSW are the abbreviations of days to flowering and thousand seed weight. WW and DS are the codes of the two watering regimes; well-watered and drought stress during 3 years: 2017, 2017, and 2020.

Table 3.

Details of 49 pleiotropic SNPs of agronomic and yield-related traits detected from genome-wide association study (GWAS).

| SNP name | Chr | Allele | Number | Phenotype | Traits | Near locus previously reported in the same chromosome | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bn-A02-p8191099 | A02 | AA | AC | CC | 15 | 20 | 83 | 186.0 | 182.3 | 183.0 | DTF | New |

| 193.8 | 189.4 | 190.7 | DTSD | |||||||||

| Bn-A02-p8284992 | A02 | AA | AG | GG | 15 | 18 | 84 | 186.0 | 181.5 | 183.2 | DTF | New |

| 193.8 | 189.1 | 190.8 | DTSD | |||||||||

| Bn-A02-p8323616 | A02 | AA | AC | CC | 16 | 19 | 84 | 185.8 | 181.8 | 183.1 | DTF | New |

| 193.5 | 189.0 | 190.8 | DTSD | |||||||||

| Bn-A02-p8440451 | A02 | AA | AG | GG | 24 | 31 | 54 | 185.1 | 181.3 | 183.5 | DTF | New |

| 192.7 | 188.9 | 191.1 | DTSD | |||||||||

| Bn-A02-p8660632 | A02 | AA | AG | GG | 18 | 25 | 76 | 185.4 | 182.1 | 184.4 | DTF |

BnaA02g12130D, BnaA02g12260D

(Zheng et al., 2017) |

| 186.8 | 189.5 | 191.6 | DTSD | |||||||||

| Bn-A02-p8934537 | A02 | AA | AG | GG | 18 | 20 | 81 | 185.2 | 182.5 | 183.0 | DTF | Bn-A02-p3539297 (Xu et al., 2015) |

| 193.1 | 190.0 | 190.6 | DTSD | |||||||||

| Bn-A02-p8999771 | A02 | AA | AC | CC | 19 | 21 | 79 | 185.1 | 182.4 | 183.0 | DTF | Bn-A02-p3539297 (Xu et al., 2015) |

| 192.9 | 189.8 | 190.6 | DTSD | |||||||||

| Bn-A02-p9000921 | A02 | AA | AG | GG | 79 | 21 | 19 | 183.0 | 182.4 | 185.1 | DTF | Bn-A02-p3539297 (Xu et al., 2015) |

| 190.6 | 189.8 | 192.9 | DTSD | |||||||||

| Bn-A02-p8190375 | A02 | AA | AG | GG | 15 | 20 | 83 | 168.0 | 182.3 | 183.0 | DTF | New |

| 193.8 | 189.4 | 190.7 | DTSD | |||||||||

| Bn-A10-p13390065 | A10 | AA | AG | GG | 6 | 14 | 98 | 179.5 | 178.96 | 184.0 | DTF | BnaA10g18420D, BnaA10g18480D, BnaA10g22080D, BnaA10g24300D (Helal et al., 2021) |

| 187.3 | 187.26 | 191.5 | DTSD | |||||||||

| Bn-A10-p15668415 | A10 | AA | AG | GG | 12 | 17 | 89 | 179.8 | 180.5 | 184.1 | DTF | New |

| 187.6 | 188.7 | 191.7 | DTSD | |||||||||

| Bn-A01-p17377721 | A01 | AA | AC | CC | 4 | 25 | 88 | 187.0 | 190.7 | 191.2 | DTSD | New |

| 121.0 | 116.2 | 118.2 | PH | |||||||||

| Bn-A01-p27079797 | A01 | AA | AG | GG | 33 | 83 | 2 | 192.0 | 190.4 | 191.9 | DTSD | New |

| 117.8 | 118.1 | 121.3 | PH | |||||||||

| Bn-A01-p21758046 | A01 | AA | AG | GG | 51 | 42 | 25 | 191.2 | 190.4 | 191.0 | DTSD | BnaA01g26410D-BnaA01g26530D (Lu et al., 2017) |

| 118.3 | 117.6 | 117.7 | PH | |||||||||

| 9.5 | 8.7 | 9.1 | HI | |||||||||

| Bn-A01-p5715141 | A01 | AA | AG | GG | 27 | 28 | 62 | 191.9 | 190.7 | 190.5 | DTSD | Bna.QRT3 (BnaA01g10390D) (Lu et al., 2017) |

| 118.4 | 117.5 | 117.7 | PH | |||||||||

| 9.3 | 8.8 | 9.1 | HI | |||||||||

| Bn-A01-p6678914 | A01 | AA | AG | GG | 93 | 16 | 6 | 266.8 | 266.5 | 266.3 | DTR | Bn-A01-p7430311 (Sun et al., 2016b) |

| 117.8 | 116.8 | 118.2 | PH | |||||||||

| Bn-A01-p9203096 | A01 | AA | AG | GG | 8 | 19 | 90 | 265.6 | 266.1 | 266.8 | DTR | New |

| 118.1 | 117.8 | 117.9 | PH | |||||||||

| Bn-scaff_18936_1-p102755 | C03 | AA | AG | GG | 75 | 27 | 13 | 266.8 | 266.5 | 266.4 | DTR | New |

| 118.2 | 116.6 | 117.1 | PH | |||||||||

| Bn-scaff_18936_1-p240670 | C03 | AA | AG | GG | 16 | 29 | 72 | 266.4 | 266.4 | 266.8 | DTR | New |

| 116.9 | 117.4 | 118.3 | PH | |||||||||

| Bn-scaff_18936_1-p269153 | C03 | AA | AC | CC | 95 | 19 | 4 | 266.7 | 266.4 | 267.7 | DTR | New |

| 118.3 | 116.6 | 113.7 | PH | |||||||||

| Bn-scaff_18936_1-p472353 | C03 | AA | AG | GG | 17 | 36 | 65 | 266.9 | 266.4 | 266.7 | DTR | New |

| 116.8 | 118.2 | 118.0 | PH | |||||||||

| Bn-scaff_18936_1-p93643 | C03 | AA | AG | GG | 13 | 27 | 76 | 266.4 | 266.5 | 266.8 | DTR | New |

| 117.1 | 117.0 | 118.2 | PH | |||||||||

| Bn-scaff_18936_1-p97644 | C03 | AA | AC | CC | 76 | 28 | 13 | 266.8 | 266.5 | 266.4 | DTR | New |

| 118.2 | 117.0 | 117.1 | PH | |||||||||

| Bn-scaff_18936_1-p274133 | C03 | AA | AG | GG | 5 | 17 | 95 | 267.3 | 266.4 | 266.7 | DTR | New |

| 114.4 | 116.5 | 118.3 | PH | |||||||||

| Bn-A01-p7619726 | A01 | AA | AG | GG | 102 | 12 | 5 | 265.6 | 265.7 | 266.8 | DTR | New |

| 117.8 | 117.0 | 122.0 | PH | |||||||||

| 9.1 | 9.0 | 9.8 | HI | |||||||||

| Bn-A01-p8014995 | A01 | AA | AG | GG | 4 | 9 | 104 | 266.9 | 265.6 | 266.7 | DTR | BnvaA0107152286 (Han et al., 2022) |

| 118.7 | 115.6 | 118.0 | PH | |||||||||

| 9.1 | 8.7 | 9.2 | HI | |||||||||

| Bn-scaff_18936_1-p439378 | C03 | AA | AG | GG | 5 | 17 | 96 | 267.3 | 265.8 | 266.8 | DTR | New |

| 114.4 | 117.1 | 118.2 | PH | |||||||||

| 1,762.8 | 1,875.1 | 1,905.8 | PW | |||||||||

| Bn-scaff_18936_1-p440619 | C03 | AA | AG | GG | 5 | 17 | 96 | 266.8 | 265.8 | 267.3 | DTR | New |

| 114.4 | 117.1 | 118.2 | PH | |||||||||

| 1,762.8 | 1,875.1 | 1,905.8 | PW | |||||||||

| Bn-scaff_18936_1-p559490 | C03 | AA | AC | CC | 3 | 20 | 95 | 267.4 | 265.9 | 266.8 | DTR | New |

| 112.8 | 116.3 | 118.4 | PH | |||||||||

| 1,539.0 | 1,878.7 | 1908.4 | PW | |||||||||

| Bn-scaff_18936_1-p610540 | C03 | AA | AG | GG | 94 | 20 | 4 | 267.8 | 266.1 | 266.7 | DTR | New |

| 118.4 | 116.2 | 114.4 | PH | |||||||||

| 1,911.3 | 1,867.0 | 1662.0 | PW | |||||||||

| Bn-scaff_18936_1-p611810 | C03 | AA | AC | CC | 94 | 20 | 4 | 267.8 | 266.1 | 266.7 | DTR | New |

| 118.4 | 116.2 | 114.4 | PH | |||||||||

| 1,911.3 | 1,867.0 | 1662.0 | PW | |||||||||

| Bn-scaff_18936_1-p618378 | C03 | AA | AG | GG | 4 | 20 | 94 | 267.8 | 266.1 | 266.7 | DTR | BnaC03g45540D (Zhang et al., 2023a) |

| 114.4 | 116.2 | 118.4 | PH | |||||||||

| 1,662.0 | 1,867.0 | 1911.3 | PW | |||||||||

| Bn-scaff_18936_1-p622547 | C03 | AA | AC | CC | 94 | 20 | 4 | 266.7 | 266.1 | 267.8 | DTR | New |

| 118.4 | 116.2 | 114.4 | PH | |||||||||

| 1,911.3 | 1,867.0 | 1662.0 | PW | |||||||||

| Bn-scaff_18936_1-p643990 | C03 | AA | AG | GG | 94 | 20 | 4 | 266.7 | 266.1 | 267.8 | DTR | New |

| 118.4 | 116.2 | 114.4 | PH | |||||||||

| 1,911.3 | 1,867.0 | 1662.0 | PW | |||||||||

| Bn-A08-p12555227 | A08 | AA | AG | GG | 11 | 20 | 86 | 1,936.4 | 1,903.4 | 1882.5 | PW | New |

| 197.6 | 177.1 | 174.9 | SWPP | |||||||||

| 9.9 | 9.0 | 9.0 | HI | |||||||||

| 2,507.1 | 2,172.5 | 2196.8 | SY | |||||||||

| Bn-A08-p15782077 | A08 | AA | AG | GG | 70 | 29 | 20 | 1,822.2 | 1954.1 | 2041.1 | PW | New |

| 168.1 | 182.7 | 204.7 | SWPP | |||||||||

| 9.1 | 9.0 | 9.5 | HI | |||||||||

| 2,127.5 | 2,255.8 | 2520.0 | SY | |||||||||

| Bn-A08-p15782229 | A08 | AA | AG | GG | 70 | 28 | 20 | 1,822.2 | 1,947.9 | 2041.1 | PW | New |

| 168.1 | 182.1 | 204.7 | SWPP | |||||||||

| 9.1 | 9.0 | 9.5 | HI | |||||||||

| 2,127.5 | 2,234.1 | 2520.0 | SY | |||||||||

| Bn-A08-p12556455 | A08 | AA | AG | GG | 88 | 10 | 11 | 1,887.5 | 1,832.9 | 2098.3 | PW | New |

| 175.0 | 179.7 | 264.3 | SWPP | |||||||||

| 2,201.0 | 2,151.8 | 3177.8 | SY | |||||||||

| Bn-A08-p13626189 | A08 | AA | AG | GG | 72 | 31 | 15 | 1,890.8 | 1,870.0 | 1932.4 | PW | New |

| 175.3 | 175.7 | 189.7 | SWPP | |||||||||

| 2,191.0 | 2,198.2 | 2368.3 | SY | |||||||||

| Bn-A08-p13626982 | A08 | AA | AG | GG | 16 | 32 | 70 | 1,906.0 | 1,895.2 | 1885.0 | PW | New |

| 188.7 | 175.6 | 175.4 | SWPP | |||||||||

| 2,339.1 | 2,190.0 | 2198.8 | SY | |||||||||

| Bn-A08-p13638847 | A08 | AA | AC | CC | 69 | 33 | 16 | 1,889.1 | 1,886.3 | 1906.0 | PW | New |

| 175.8 | 174.8 | 188.7 | SWPP | |||||||||

| 2,201.5 | 2,184.7 | 2339.1 | SY | |||||||||

| Bn-A08-p13670107 | A08 | AA | AG | GG | 15 | 28 | 72 | 1,932.4 | 1,880.5 | 1890.8 | PW | New |

| 189.7 | 176.0 | 175.3 | SWPP | |||||||||

| 2,368.3 | 2,217.4 | 2191.0 | SY | |||||||||

| Bn-A08-p14538807 | A08 | AA | AG | GG | 87 | 19 | 8 | 1,873.6 | 1,955.0 | 1930.9 | PW | New |

| 171.6 | 193.4 | 185.4 | SWPP | |||||||||

| 2,163.2 | 2,330.7 | 2371.0 | SY | |||||||||

| Bn-A08-p15994149 | A08 | AA | AC | CC | 29 | 25 | 63 | 1,988.2 | 1,901.6 | 1839.1 | PW |

Bna.BBX20 (BnaA08g16780D, AT4G39070) (Lu et al., 2017) Bna.BBX15 (BnaA08g19420D) (Lu et al., 2017) |

| 198.4 | 178.7 | 167.3 | SWPP | |||||||||

| 2,432.6 | 2,196.9 | 2132.8 | SY | |||||||||

| Bn-scaff_19208_1-p78898 | C04 | AA | AG | GG | 66 | 32 | 20 | 1,883.9 | 1,828.8 | 2002.8 | PW | New |

| 178.4 | 161.4 | 200.9 | SWPP | |||||||||

| 2,196.2 | 2,098.2 | 2489.5 | SY | |||||||||

| Bn-scaff_19208_1-p82535 | C04 | AA | AG | GG | 66 | 31 | 20 | 1,883.9 | 1,827.1 | 2002.8 | PW | New |

| 178.4 | 161.5 | 200.9 | SWPP | |||||||||

| 2,196.2 | 2,103.9 | 2489.5 | SY | |||||||||

| Bn-scaff_19208_1-p93814 | C04 | AA | AC | CC | 66 | 31 | 21 | 1,883.9 | 1,827.1 | 2002.8 | PW | New |

| 178.4 | 161.5 | 200.9 | SWPP | |||||||||

| 2,196.2 | 2,103.9 | 2489.5 | SY | |||||||||

| Bn-scaff_19208_1-p94498 | C04 | AA | AC | CC | 66 | 32 | 21 | 1,883.9 | 1,828.8 | 2002.8 | PW | New |

| 178.4 | 161.4 | 200.9 | SWPP | |||||||||

| 2,196.2 | 2,098.2 | 2489.5 | SY | |||||||||

| Bn-scaff_19208_1-p94501 | C04 | AA | AG | GG | 20 | 31 | 66 | 2,002.8 | 1,827.1 | 1883.9 | PW | New |

| 200.9 | 161.5 | 178.4 | SWPP | |||||||||

| 2,489.5 | 2,103.9 | 2196.2 | SY | |||||||||

DTF, DTSD, DTR, PH, PW, SWPP, HI, and SY are the abbreviations of days to flowering, days to silique development, days to ripening, plant height, plant weight, seed weight/plant, harvest index, and seed yield, respectively.

3.5.1. SNPs and candidate genes linked with phenological and agronomic traits under drought conditions

3.5.1.1. Days to flowering

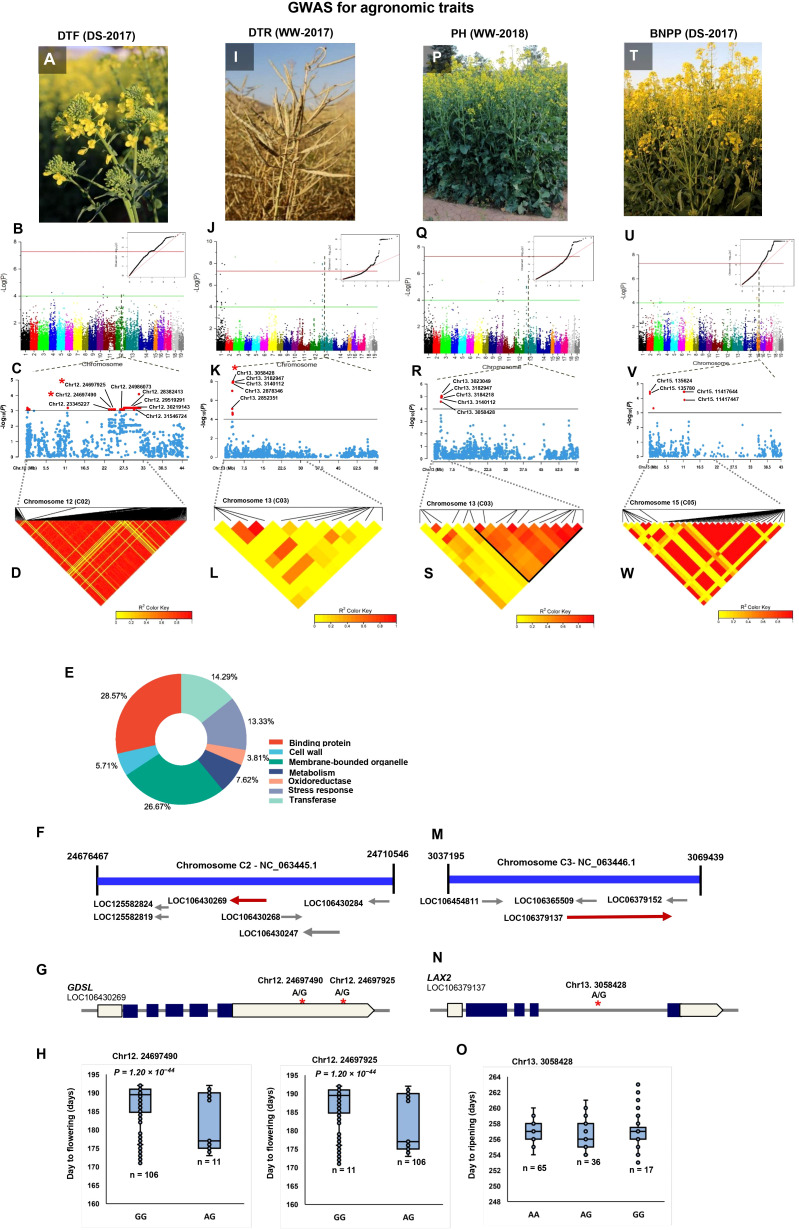

A total of 324 significant SNPs were significantly associated with the DTF ( Additional Files 5 - 8 ). The SNP Chr10:222927 linked with flowering time in both WW and DS conditions across 2 years ( Table 2 ). Six linked SNPs, (Chr10:222927, Chr10:8893827, Chr10:8998128, Chr10:16091976, Chr10:16091976, Chr10:16139771) were significant across 2 years under drought conditions ( Table 2 ). We found that the C02 peak was a major associated signal, harboring 52.77% of the associated SNPs (171) ( Additional File 5 ; Figures 3A–D ), which had not been reported previously. Accordingly, we focused on the 159 SNPs positioned in the Chr12:23345227–32168120 genomic region and extracted all CGs within 200 kbps of the most significant SNPs. A number of 146 genes, including transcription factors, enzymes, and transporters that represent plausible candidates for the causal gene of the flowering time, were identified ( Additional File 10 ). Information of seven enriched gene ontology groups for DTF candidate genes is shown in Figure 3E . The SNP Bn-scaff_18507_1-p354053 (A/G) located 12.7 kbps downstream of LIPOXYGENASE 4 (LOX4) plays important roles in flower development and male fertility regulation (Klepikova et al., 2016). The Chr12:24697490 (A/G) and Chr12:24697925 (A/G) SNPs in a LD block were located within the position of candidate flowering gene GDSL ESTERASE/LIPASE ( Figures 3F, G ). Our results showed that the varieties with the alleles GG in SNP Chr12:24697490 showed significantly late flowering compared with those with the alleles AG ( Figure 3H ). The 1-kbps LD block surrounding Chr12:24986073 (A/C) contains the candidate flowering gene FAR1-RELATED SEQUENCE (FRS). The 3.2-kbps LD block surrounding Chr12:28382413 (A/G) contains the candidate flowering gene 9-CIS-EPOXTCAROTENOID DIOXYGENASE (NCED9), which is a critical gene in the regulation of abscisic acid (ABA) synthesis. The 60.8-kbps LD block surrounding the Chr12:29519291 (A/G) SNP contains CINNAMOYL-COA REDUCTASE 2 (CCR2), which plays an important role in pollen development by regulating the programmed cell death (PCD) of tapetum cells (Zhang et al., 2023c). Chr12:30219143 (A/G), which explained 11.62% of the phenotypic variance located 3.6 kbps downstream of pollen-specific gene RALFL14. Another pollen-specific gene, DEFENSIN-LIKE 7 (DEFL7), is located 36.71 kbps downstream of Chr12:30219143 (P = 6.58 × 10−4). DEFL genes are involved in pollen tube guidance and pollen tube reception and are responsible for the failure of double fertilization events (Takeuchi and Higashiyama, 2012).

Figure 3.

Genome-wide association study (GWAS) reveals the genetic basis of agronomic traits. (A) GWAS of day to flowering (DTF) using the 119 rapeseed (Brassica napus) varieties under drought stress conditions in 2017. (B) Manhattan plot and corresponding quantile–quantile (QQ) plot displaying the GWAS result of DTF in 19 chromosomes (1–10 stand for rapeseed chromosome of A01–A10, and 11–19 stand for rapeseed chromosome of C01–C09 at the horizontal axis). SNPs on different chromosomes are denoted by different colors. (C) Locus zoom plot for DTF associations in chromosome 12 (C02). (D) A representation of pairwise r 2 value (displayed as percentages) among polymorphic sites of chromosome 12 (C02) for DTF. (E) CirGO visualization of GO enrichment analysis of significant genes identified by GWAS for DTF. (F) Schematic diagram of the region of chromosome 12 (C02) genotyped in this study, showing the associated gene GDSL (LOC106430269). Chromosomal position based on the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). (G) Gene model of GDSL. Solid boxes indicate exons, open boxes indicate untranslated regions (UTRs), and lines connecting the exons indicate introns. The red stars mark the position of Chr12:24697490 and Chr12:24697925. (H) The influence of Chr12:24697490 and Chr12:24697925 on day to flowering. The significance of difference between two varieties was evaluated using Student’s t-test. (I) GWAS of day to ripening (DTR) under well-watered conditions in 2017. (J) Manhattan plot and corresponding quantile–quantile (QQ) plot displaying the GWAS result of DTR in 19 chromosomes. (K) Locus zoom plot for DTR associations in the chromosome 13 (C03). (L) A representation of pairwise r 2 value (displayed as percentages) among polymorphic sites of chromosome 13 (C03) for DTR. (M) Schematic diagram of the region of chromosome 13 (C03) genotyped in this study, showing the associated gene LAX2 (LOC106379137). Chromosomal position based on NCBI. (N) Gene model of LAX2. Solid boxes indicate exons, open boxes indicate untranslated regions (UTRs), and lines connecting the exons indicate introns. The red star marks the position of Chr13:3058428. (O) The influence of Chr13:3058428 on day to ripening. (P) GWAS of plant height (PH) under well-watered conditions in 2018. (Q) Manhattan plot and corresponding quantile–quantile (QQ) plot displaying the GWAS result of PH in 19 chromosomes. (R) Locus zoom plot for PH associations in the chromosome 13 (C03). (S) A representation of pairwise r 2 value (displayed as percentages) among polymorphic sites of chromosome 13 (C03) for PH. (T) GWAS of branch number/plant (BNPP) under drought stress conditions in 2017. (U) Manhattan plot and corresponding quantile–quantile (QQ) plot displaying the GWAS result of BNPP in 19 chromosomes. (V) Locus zoom plot for BNPP associations in the chromosome 15 (C05). (W) A representation of pairwise r 2 value (displayed as percentages) among polymorphic sites of chromosome 15 (C05) for BNPP.

3.5.1.2. Days to silique development

GWAS identified 30 TASs on chromosomes A01, A02, A03, and A10 for DTSD ( Additional Files 5 - 8 ). Chr1:18351464 and Chr1:5217408 had the strongest signals for DTSD in the WW condition in 2017, which explained 43.50% and 37.75% of the phenotypic variance, respectively ( Additional File 5 ). Three SNPs under drought conditions, Chr3:25485861 (A/G), Chr3:25524140 (A/G), and Chr3:25525060 (A/C), identified on chromosome A03 were located ~20 kbps downstream and upstream of the AGL19 gene, respectively. This gene is involved in seed formation, silique maturity, and seed desiccation (Shah et al., 2022).

3.5.1.3. Days to ripening

A total of 97 significant associations were identified for DTR ( Additional Files 5 - 8 ). The 55 and 42 TASs identified in WW and DS conditions explained 63.20% and 36.79% of the phenotypic variance. There were 77 CGs associated with 21 significant SNPs in the C03:2498421–3217123 intervals ( Additional Files 5 , 10 ; Figures 3I–L ). Chr13:2852351 (P = 2.11 × 10−5) and Chr13:2878346 (P =1.36 × 10−8) were located ~10 kbps downstream and upstream of aspartic proteinase oryzasin-1, respectively. In B. napus, BnaAP36s and BnaAP39s genes play a critical role in pollen tube growth (Wang et al., 2023). Chr13:3058428 (P =1.36 × 10−8) explained 42.99% of the phenotypic variance located within the position of the panicle architecture-related gene LAX PANICLE 2 (LAX2) ( Figures 3M, N ). The varieties with the AA and GG alleles in this SNP showed significantly late maturity compared with those with the AG alleles ( Figure 3O ). Another specific gene, FY, located 19.96 kbps upstream of the Chr13:3140112 (P = 1.07 × 10−8) SNP, plays a role in the regulation of flowering time in the autonomous flowering pathway through repression of the FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC) (Kyung et al., 2022). Chr13:3182947 which explained 43.65% of the phenotypic variance was located <1 kbps upstream of two genes from MADS-box AGAMOUS (AG) genes: AGL15 and AGL16. MADS-box genes play an important role in regulating floral carpel and ovule development (Sheng et al., 2019; Shah et al., 2022).

3.5.1.4. Plant height

A total of 70 significantly associated SNPs were identified for PH, of which 59 and 11 were identified in the WW and DS conditions, respectively ( Additional Files 5 - 8 ). Among the linked SNPs, 16 SNPs identified in the WW conditions were located on chromosome C03 (2736068–3217123 bp), which explained 31.69% of the phenotypic variance ( Additional File 6 ; Figures 3P–S ). The 14.28-kbps LD block surrounding Chr13:3023049 (P = 8.96 × 10−6) contains the TIFY9 gene ( Figure 3R ). The TIFY family is a plant-specific gene involved in accelerated cell division, leaf flatness, and lateral organ development (Zhang et al., 2020). Chr13:3058428 (A/G) which explained 27.34% of the phenotypic variance of PH was located 12.78 kbps downstream of gene GH3.12 responsible for plant stem growth. Three SNPs, Chr13:3140112 (A/G), and Chr13:3182947 (A/C), and Chr13:3184218 (A/G), were located ~20 kbps downstream and upstream of PAO1.

3.5.2. SNPs and candidate genes linked with yield and yield-related traits under drought conditions

3.5.2.1. Branch number/plant

Of 250 SNPs detected for BNPP, 28 and 222 SNPs explained 10.58% and 89.14% of the BNPP variance in the WW and DS conditions, respectively ( Additional Files 5 - 8 ). There were 22 of the 222 SNPs identified under DS condition located in the C05:11200372–1417644-bp region, which had not been reported previously ( Additional Files 5 , 10 ; Figures 3T–W ). Five SNPs, namely, Chr15:125848, Chr15:135624, Chr15:135780, Chr15:136834, and Chr15:136975, within an LD block were located <5 kbps downstream and upstream of the SBT1.1 gene ( Figure 3V ), a gene which contributed to elongation of the main shoot, increasing inflorescence branching and biomass (Martinez et al., 2015). Two SNPs, Chr15: 136834 (P = 1.31 × 10−4) and Chr15: 136975 (P = 3.63 × 10−5), in an LD block were mapped to 11 kbps upstream of a member of SKP1-Like gene family, ASK3.

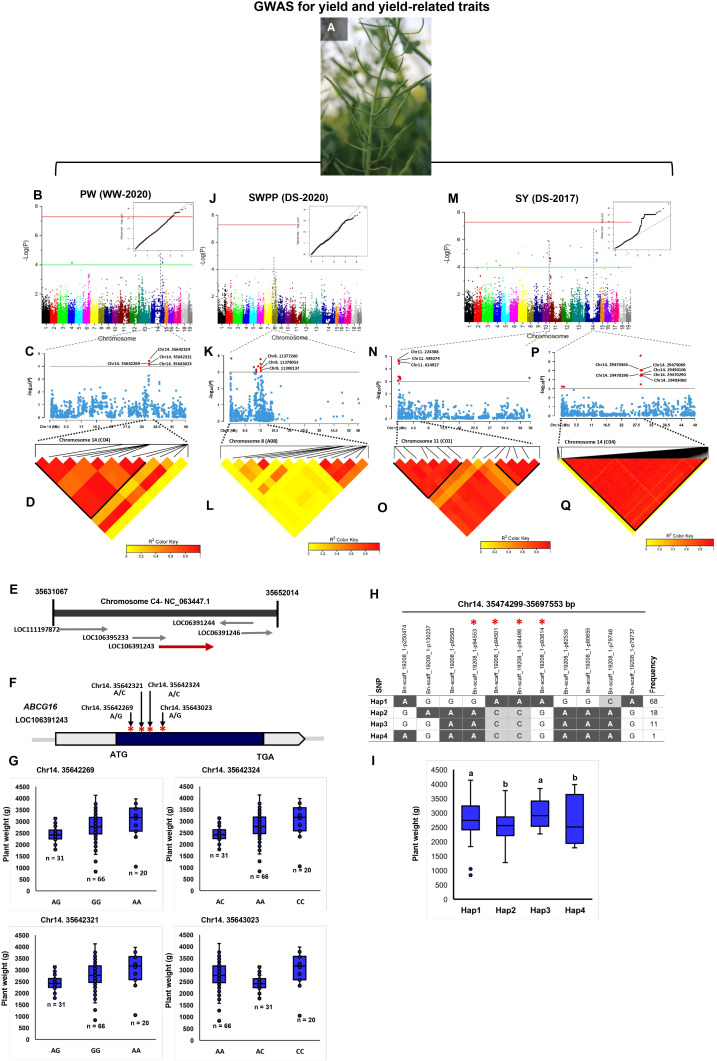

3.5.2.2. Plant weight

Of the 56 significant SNPs for PW, 34 and 22 explained 58.10% and 41.89% of PW variance in the WW and DS conditions, respectively ( Additional Files 5 - 8 ). There were 12 TASs of the WW condition located on the 35,474,299–35,698,370 bp interval in chromosome C04 ( Additional File 7 ; Figures 4A–D ). This genomic region contained four genes of ABC transporter G superfamily (ABCG16, ABCG17, ABCG18, and ABCG19) which contribute to cytokinin transport in the shoot and enhance the tiller number, grain number per panicle, and grain yield (Wu et al., 2022a). Four SNPs, Chr14:35642269 (A/G), Chr14:35642321 (A/C), Chr14:35642324 (A/C), and Chr14:35643023 (A/G), in an LD block, were located within the ABCG16 sequence ( Figures 4C, E, F ). The varieties with the alleles AA and CC in these SNPs showed significantly higher plant weight compared with varieties with other alleles ( Figure 4G ). We identified four haplotypes/markers associated with PW located on chromosome C04 (35,474,299–35,697,553 bp) ( Figure 4H ) with an average plant weight of 2984.37 g in Hap3 significantly greater than in other three Haps ( Figure 4I ).

Figure 4.

Genome-wide association study (GWAS) reveals the genetic basis of seed yield and yield-related traits in rapeseed (Brassica napus). (A) Phenotypes of siliques in rapeseed which are considered the major contributing factors for increasing rapeseed yield. (B–D) GWAS of plant weight (PW) using the 119 rapeseed varieties under well-watered conditions in 2020. (B) Manhattan plot and corresponding quantile–quantile (QQ) plot displaying the GWAS result of PW in 19 chromosomes (1–10 stand for rapeseed chromosomes of A01–A10, and 11–19 stand for rapeseed chromosomes of C01–C09 at the horizontal axis). SNPs on different chromosomes are denoted by different colors. (C) Locus zoom plot for PW associations in the chromosome 14 (C04). (D) A representation of pairwise r 2 value (displayed as percentages) among polymorphic sites of chromosome 14 (C04) for PW. (E) Schematic diagram of the region of chromosome 14 (C04) genotyped in this study, showing the associated gene ABCG16 (LOC106391243). Chromosomal position based on the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). (F) Gene model of ABCG16. Solid boxes indicate exons, and open boxes indicate untranslated regions (UTRs). The red stars mark the positions of Chr14:35642269, Chr14:35642321, Chr14:35642324, and Chr14:35643023. (G) The influence of Chr14:35642269, Chr14:35642321, Chr14:35642324, and Chr14:35643023 on plant weight. (H) Haplotype block based on 11 significant SNPs on chromosome 14 (C04). (I) Four different haplotype variants (Hap1–Hap4) are present at different frequencies in the analyzed population. Boxplots for plant weight indicate the phenotype values corresponding to the four different haplotype groups. Significant differences among haplotypes were identified using one-way ANOVA. Different letters indicate distinct groups. (J–L) GWAS of seed weight/plant (SWPP) under drought stress conditions in 2020. (J) Manhattan plot and corresponding quantile–quantile (QQ) plot displaying the GWAS result of SWPP in 19 chromosomes. (K) Locus zoom plot for SWPP associations in chromosome 8 (A08). (L) A representation of the pairwise r 2 value (displayed as percentages) among polymorphic sites of chromosome 8 (A08) for SWPP. (M-Q) GWAS of seed yield (SY) under drought stress conditions in 2017. (M) Manhattan plot and corresponding quantile–quantile (QQ) plot displaying the GWAS result of SY in 19 chromosomes. (N) Locus zoom plot for SY associations in chromosome 11 (C01). (O) A representation of pairwise r 2 value (displayed as percentages) among polymorphic sites of chromosome 11 (C01) for SY. (P) Locus zoom plot for SY associations in the chromosome 14 (C04). (Q) A representation of pairwise r 2 value (displayed as percentages) among polymorphic sites of chromosome 14 (C04) for SY.

3.5.2.3. Seed number/silique

There were 10 drought-related TASs identified on chromosome A02 (750,194–791,056 bp) that had not been reported in drought stress in rapeseed, previously ( Additional File 7 ). The Chr2:751843 (A/G), Chr2:751923 (A/G), and Chr2:752016 (A/G) SNPs located within a MADS-box gene, FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC), involved in flowering time control, inflorescence architecture, floral organ identity determination, and seed development (Soppe et al., 2021). Chr2:989812 (A/C) located 9.10 kbps downstream of seed plant-specific BIG GRAIN LIKE gene family (BG1-D) regulates grain number per plant, grain size with both bigger length and width, and finally grain yield (Liu et al., 2015; Lo et al., 2020; Gao et al., 2022). Chr7:36944365 (A/C) located within CAND1 encodes cullin-associated Nedd8-dissociated protein 1 ( Additional File 7 ).

3.5.2.4. Seed weight/plant

Of the significant TASs identified in drought stress, 10 were located on 10,335,313 bp–13,452,346 bp of chromosome A08 ( Additional Files 7 , 8 ). Chr8:11377260 and Chr8:11378053 (P = 7 × 10−4) were located within the position of a member of the purine permease (PUP)-type transporter gene family, PUP21. In addition, Chr8:11390137 (A/G) was located within other members of the PUP-like family gene, PUP10 ( Figures 4J–L ).

3.5.2.5. Thousand seed weight

Among the THSW-associated SNPs, 10 were stable overs 2 years under drought stress conditions ( Table 2 ). There were 13 TASs on chromosome C02 (16,251,517 bp–16,902,605 bp) and eight on chromosome C06 (15,724,425 bp–15,768,599 bp) that explained 26.08% and 19.7% of the THSW variance in the WW and DS treatments, respectively ( Additional File 7 ).

3.5.2.6. Seed yield

Of the SY SNPs, 34 were positioned in the 130,644-bp–676,816-bp interval on chromosome C01 ( Figures 4M–O ). Chr11:224308 (P = 2.58 × 10−5; Figure 4N ), which explained 24.34% of the phenotypic variance located within the position of the DRG3 gene belonging to the G-protein family. Chr11:449274 (P = 4.56 × 10−4; Figure 4N ), which explained 17.69% of the SY variance located 7.78 kbps downstream of CYP79B1. Chr11:614927 (P = 4.68 × 10−4) was located within the sequence of the AGAMOUS LIKE21 (AGL21) gene, which has been shown to upregulate in siliques and dry seeds in rapeseed (Yu et al., 2017). There were 112 drought-related SY–SNPs located in the 29,030,148-bp–29,607,326-bp interval on chromosome C04 and explained 67.56% of the phenotypic variance of SY ( Additional File 5 ; Figures 4P, Q ). Six SNPs on chromosome C04 with complete LD (r2 = 1, Figure 4Q ), namely, Chr14:29470290, Chr14:29470363, Chr14:29479069, Chr14:29490106, Chr14:29492969, and Chr14:29493060, located <13 kbps downstream and upstream of CYP78A9, which is another member of the cytochrome P450 superfamily.

3.5.2.7. Harvest index

The 38 SNPs significantly associated with HI contributed to 38.34% and 61.65% of HI variance in the WW and DS conditions, respectively ( Additional Files 5 - 8 ). Among the HI SNPs, seven SNPs were located on chromosome C06 (24,703,167 bp–34,271,977 bp) and five on chromosome C08 (28,759,659 bp–30,043,480 bp) in the WW condition in 2017 ( Additional File 5 ).

3.6. Identification of novel pleiotropic SNPs associated with more than one trait

In the current study, 19 novel repetitive SNPs linked to both DTF and THSW traits were identified on chromosomes A04, A10, C02, C03, and C06. Analysis of SNPs for pairwise traits revealed that 49 SNPs associated with two or more than two traits and the differences in phenotypic values between varieties with two alleles at each of these SNPs were significant. Of the 49 pleiotropic SNPs, 11 SNPs were overlapped with those reported in previous studies only and the rest were unique in this study ( Table 3 ). There were 11 SNPs on chromosome A02 and A10 that were associated with both DTF and DTSD simultaneously. A pleiotropic SNP Bn-A02-p8660632 for the phenotype of both DTF and DTSD mapped on chromosome A02 and was 2,186 kbps downstream of the position of the BnaA02g12130D and BnaA02g12260D genes. These genes affected DTF and PH in B. napus in the Zheng et al. (2017) study. Pleiotropic SNPs were identified for DTSD and PH; DTSD, PH, and HI; DTR and PH; DTR, PH, and HI; DTR, PH, and PW; PW, SWPP, HI, and SY; and PW, SWPP, and SY ( Table 3 ). The position of the pleiotropic SNP Bn-A08-p15994149 for PW, SWPP, and SY on chromosome A08 was 3,734 kbps downstream of the candidate gene BnaA08g16780D and was 69 kbps downstream of the region (13,520,923 bp–13,598,303 bp) that affected branch pod number and pod number per plant in the Lu et al. (2016) study.

3.7. Estimating the effect of major pleiotropic SNPs on traits

As shown in Table 3 , varieties with allele AA in the Bn-A01-p21758046 and Bn-A01-p5715141 SNPs showed higher DTSD, PH, and HI. Varieties with the allele GG in Bn-A01-p7619726 had higher DTR, PH, and HI. The allele GG in Bn-scaff_18936_1-p439378 and Bn-scaff_18936_1-p440619 presented higher DTR, PH, and PW. The allele AA in Bn-scaff_18936_1-p610540 and Bn-scaff_18936_1-p611810 increased DTR, PH, and PW. Varieties with the allele AA in Bn-A08-p12555227 showed higher PW, SWPP, HI, and SY, whereas varieties with the allele GG in Bn-A08-p15782077 and Bn-A08-p15782229 had higher PW, SWPP, HI, and SY.

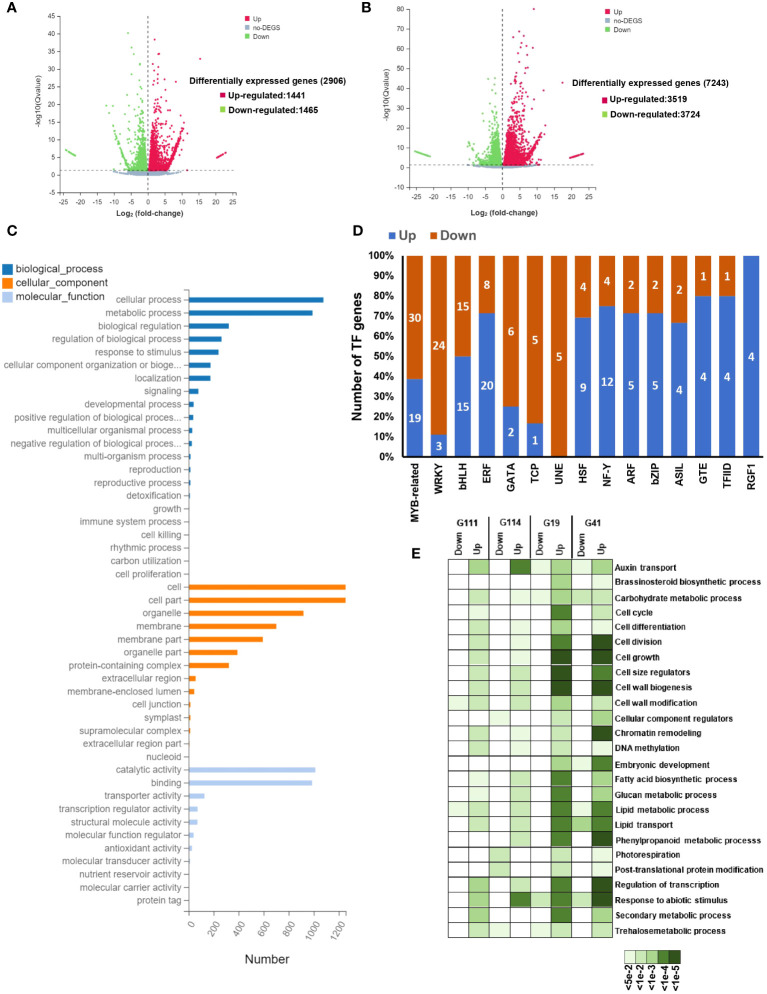

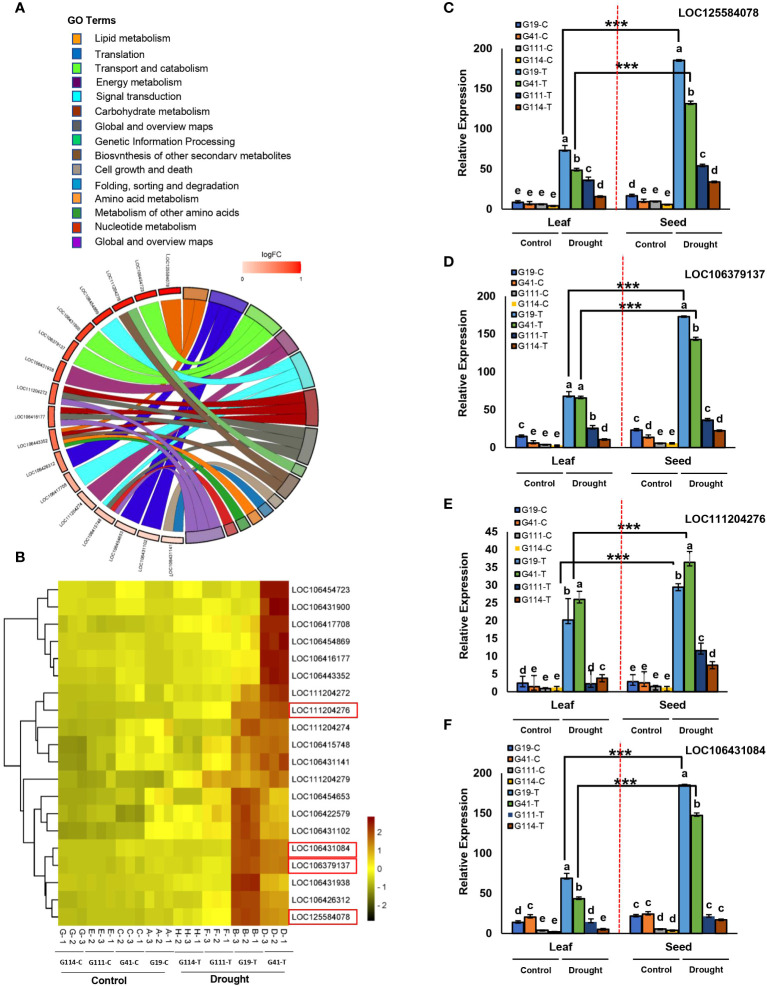

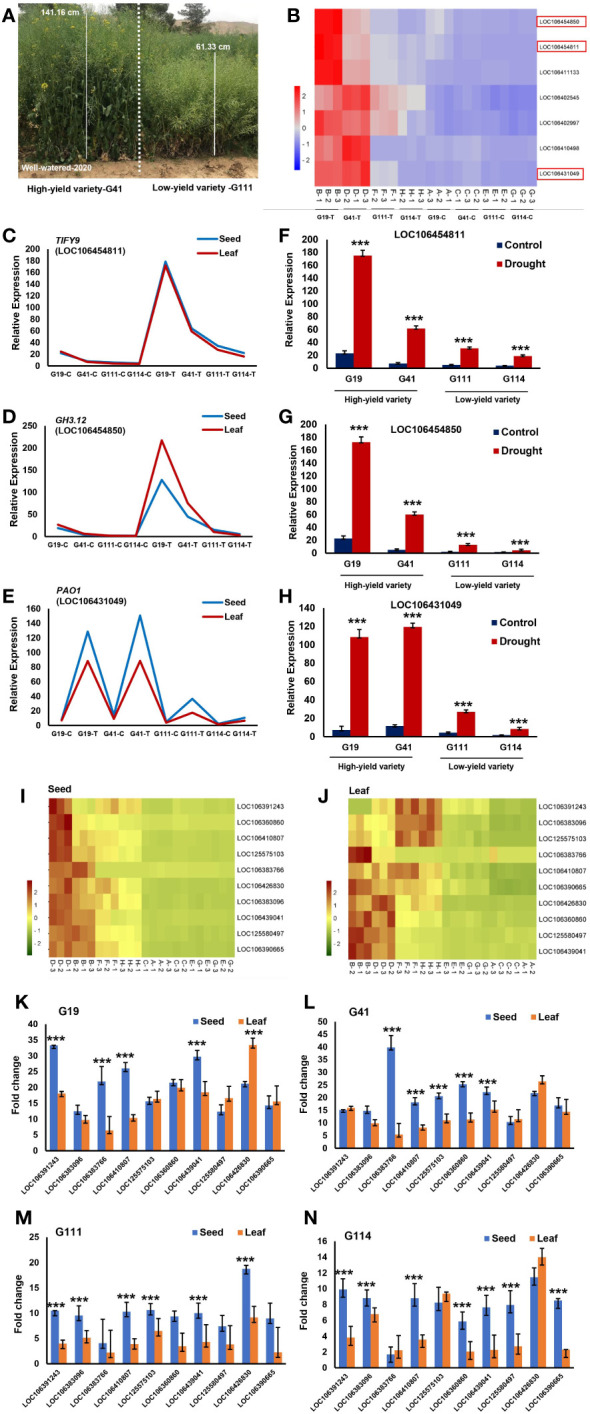

3.8. Comparative transcriptome analysis between seed and leaf of low and high grain yield varieties

The transcriptome analysis of mature seeds in the rapeseed varieties differing in their seed yield can provide crucial systems-level insights into molecular mechanisms underlying seed development and seed yield. We selected four rapeseed varieties, namely, G111 and G114 as low-seed yield and G19 and G41 as high-seed yield varieties, to investigate the transcriptional differences in the two contrasting groups. In total, 2,906 DEGs (1,441 up- and 1,465 downregulated) of both tissues (seed and leaf) in low-seed yield and 7,243 (3,519 up- and 3,724 downregulated) of both tissues in high-seed yield varieties with |log2FC| ≥ 1 and padj < 0.05 were identified ( Figures 5A, B ). Of the DEGs, 994 upregulated and 1,008 downregulated genes shared between the two contrasting groups. The Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analyses of all the genes showed that most of the genes were related to various developmental process, reproductive processes, cell wall organization, cell cycle and cell division, metabolic processes, response to stress/hormone, and regulation of transcription ( Figure 5C ). These processes are well known to be involved during various aspects of seed development. At least, 321 transcription factor (TF)-encoding genes belonging to 66 families exhibited stage-specific expression in one or more than one cultivar. The members of MYB, bHLH, ERF, WRKY, bZIP, and ARF families were highly represented in these varieties ( Figure 5D ). The expression profiles of key gene families and individual genes involved in cell division, cell size determination, cell wall modification, carbohydrate metabolism, and grain filling were analyzed. We observed a higher expression of several members of these gene families in high-yield varieties ( Figure 5E ). A higher transcriptional activity of cyclin-encoding genes was identified in high-yield varieties, which is almost related to higher mitotic activity and an extended period of cell division. The genes encoding glucan synthases and xyloglucan endotransglucosylases/hydrolases exhibited higher transcriptional activity in high-yield varieties. These enzymes are involved in the synthesis and remodeling of cell wall components and production of energy (Miedes et al., 2013; Perrot et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). Furthermore, the transcript abundance of genes involved in cell expansion (expansins), seed storage proteins (e.g., vicilin-like storage protein), and lipid transfer proteins was also significantly higher in the high-seed yield rapeseed varieties ( Figure 5E ). It has been shown that these proteins contribute to various aspects of seed development and seed maturation (Pagnussat et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2015a; Yaqoob et al., 2020; Rahman et al., 2021; Fang et al., 2023).

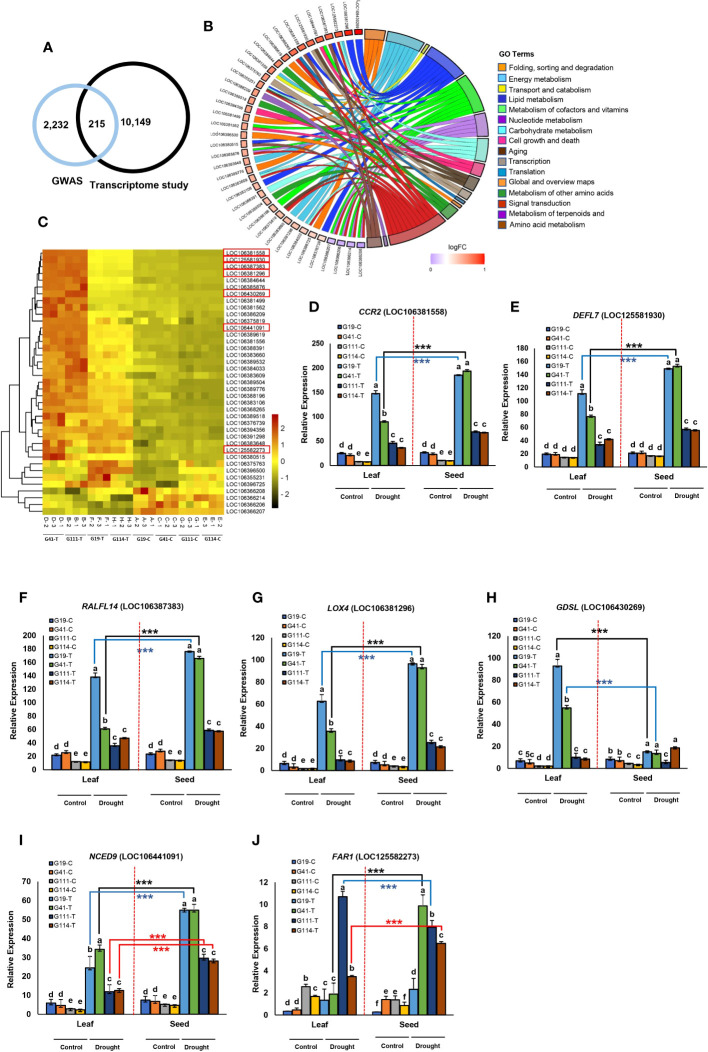

Figure 5.