Abstract

Background

Psychological interventions, along with antipsychotic medications, are recommended for adults diagnosed with a psychotic disorder. While initially designed to mitigate positive symptoms, psychological interventions targeting personal recovery were developed and aligned with the recovery framework that many mental health services have adopted. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) for psychosis is one such intervention that shows promise when delivered in an individual format. There is preliminary evidence that ACT for psychosis in a group format improves recovery.

Objective

This trial aims to evaluate the effectiveness of the “Recovery ACT” group program on personal recovery among adults living with a psychotic disorder.

Methods

Our unfunded study is a multiagency, prospective, nonrandomized, waitlist control, single-group trial of the Recovery ACT group program. The program involves 7 weekly group sessions of 90 minutes duration and a 90-minute booster session held 1 month later. We intend to recruit 160 adults living with a psychotic disorder who enroll in a group that is offered as a routine clinical service at participating public mental health services in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. The 4 assessment time points are 4-6 weeks before the start of the group program, at the start of the group program, at the end of the group program, and at the booster session. There is an optional midgroup assessment and follow-up study. The primary outcome is personal recovery. Secondary outcomes include participants’ well-being and psychological flexibility processes. Qualitative data are also collected from participants and facilitators.

Results

Recruitment began in September 2019 and is ongoing until 2024, subsequent to a 24-month disruption due to the COVID-19 pandemic. As of the submission of this paper, 93 participants consented to the evaluation, 65 completed T1 measures, and 40 had a complete data set for the proposed analyses.

Conclusions

This is the first trial evaluating the effectiveness of the Recovery ACT group program on personal recovery for adults living with a psychotic disorder. Findings will contribute to knowledge about psychosocial interventions for adults living with psychosis. This trial may also serve as an example of a partnership between clinicians and academics that can facilitate the translation of research into practice.

Trial Registration

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry ACTRN12620000223932; https://anzctr.org.au/Trial/Registration/TrialReview.aspx?ACTRN=12620000223932

International Registered Report Identifier (IRRID)

DERR1-10.2196/49849

Keywords: Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, ACT, group therapy, interventions, personal recovery, protocol, psychosis, psychotic disorders, public mental health services

Introduction

Background and Rationale

Schizophrenia spectrum disorders have a prevalence rate of 3.3 per 1000 individuals worldwide [1], with schizophrenia ranking as the twelfth most disabling disorder [2]. Psychotic disorders are typically first diagnosed in young adulthood and can run a chronic course [3]. About two-thirds of individuals diagnosed with a psychotic disorder continue to experience persistent psychotic symptoms despite adhering to antipsychotic medication regimens; about 20% do not respond at all [4]. In addition, there is a high prevalence of comorbid anxiety and mood disorders—about 40% experience anxiety [5,6] and 30%-80% experience depression [6,7]—and other challenges (eg, stigma and social exclusion) that impact well-being and functioning. Persisting psychotic symptoms, comorbid anxiety and depression, and other challenges not only contribute to an individual’s level of distress and functioning but also impact a person’s ability to fully engage in life [8], referred to as personal recovery [9].

For over 2 decades, psychological and psychosocial interventions have been internationally recommended as adjuncts to pharmacological interventions [10-13]. The leading evidence-based psychological intervention recommended for psychotic disorders is cognitive behavioral therapy for psychosis (CBTp). This intervention involves teaching skills to modify unhelpful thinking patterns that impact behavior [14] and primarily targets reduction in psychotic symptoms and, arguably, distress and functioning as well. While meta-analyses demonstrate that CBTp reduces psychotic symptoms (most notably positive symptoms) with a small effect size [15-17], CBTp does not appear to mitigate distress or improve quality of life [18]. The latter findings continue to be challenged [19,20]. Modifications of CBTp (eg, low-intensity CBTp [21,22] and group CBTp [23]) are promising, though they have yet to amass robust evidence to be recommended in treatment guidelines.

Another promising psychological therapy for psychotic disorders is Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). This approach involves developing psychological flexibility, which is the ability to be in conscious contact with the present moment, and the capacity to persist with or change behavior based on whether it aligns with one's personal values [24]. Psychological flexibility processes include willingness to be with mental experiences (thoughts, feelings, sensations, etc) instead of engaging in experiential avoidance; cognitive defusion (distancing or observing with openness and curiosity) with mental experiences; engagement in valued actions; and mindfulness (ie, awareness of the present moment) [24]. ACT adapted for individuals living with a psychotic disorder has been implemented in both inpatient and outpatient settings. There is emerging evidence [25] that this intervention not only reduces rehospitalization [26-28] but can also improve quality of life and personal recovery [29].

The first ACT for psychosis group intervention targeting quality of life and social functioning was a 4-session group (2-hour sessions run weekly) known as the “ACT for Life” program, a manualized protocol developed by researchers in the United Kingdom for adults living with psychosis [30,31]. An initial uncontrolled study evaluating this program at a community psychosis service in the United Kingdom [32] demonstrated small improvements in functioning and mood after group completion. A subsequent controlled study [33] demonstrated the positive effects of group participation on well-being over time and greater independence, as indicated by service use changes. Both studies demonstrated that the group was feasible and acceptable to adults living with psychosis.

Building on promising results from individual and group ACT programs for psychosis, the ACT for Life program was adapted for public outpatient mental health services in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia [34]. A pilot of the adapted program, referred to as “Recovery ACT,” was implemented by public mental health service clinicians as part of their routine practice and evaluated using pre- and postgroup outcome measures together with qualitative feedback from facilitators and participating consumers [35]. Results from the uncontrolled pilot study involving 9 groups and 90 consumers demonstrated that the program and its evaluation were feasible, acceptable, and safe [35]. Significant increases in personal recovery, well-being, and psychological flexibility were observed from the start to the end of the program. The extent of consumer and clinician interest in the groups, both from the original agency and additional agencies, strongly indicated the feasibility of conducting a more extensive evaluation. Building on this momentum, our clinician-academic partnership agreed to conduct this more stringent trial by incorporating a waitlist control period and an established measure of personal recovery as the primary outcome.

Objectives

The primary aim is to evaluate the effectiveness of the Recovery ACT group program on personal recovery for adults living with a psychotic disorder in routine clinical practice across public mental health organizations in Australia using a single-group, waitlist control design. A secondary aim is to evaluate the effect of the Recovery ACT group program on well-being and psychological flexibility processes (experiential avoidance, cognitive defusion, engagement in valued actions, and mindfulness). The research questions are as follows: (1) What are the clinical benefits and risks of the Recovery ACT group program for adults diagnosed with psychotic disorders as conducted in routine practice in Australia? (2) Are there changes in psychological flexibility processes due to participation in the Recovery ACT group program? (3) Are changes in psychological flexibility processes associated with changes in personal recovery and well-being?

The primary and secondary hypotheses are that the longitudinal trajectory of personal recovery and the secondary outcomes will not significantly change over the waitlist period, then will improve from the start to the end of the group program, and then improve at a less rapid rate from the end of the group to the booster session. A further hypothesis is that changes in psychological flexibility processes during the first half of the group program will be associated with changes in personal recovery and well-being in the second half of the group program.

Methods

Participants and Study Setting

We plan to recruit a minimum of 160 adults (aged between 18 and 65 years) who enroll in a Recovery ACT group program at 1 of 4 public mental health service study sites in Melbourne (NorthWestern Mental Health, St Vincent’s Mental Health Service, Alfred Mental and Addiction Health, and Peninsula Health Mental Health Service). The target minimum number of participants at NorthWestern Mental Health is 95 participants, and 32 participants each at the other study sites. The overall recruitment target was based on the minimum sample size needed to complete the intended analyses and an anticipated 60% participant retention rate based on the pilot study [35].

The inclusion criteria are a primary file diagnosis of either schizophrenia spectrum disorder or other psychotic disorder, a mood disorder with psychotic features, or a substance-induced psychotic disorder; currently receiving outpatient mental health care at 1 of the study sites; and current enrollment in a Recovery ACT group program. The exclusion criteria are lack of capacity to consent to the evaluation; lack of proficiency in speaking and comprehending English; a file diagnosis of intellectual disability or borderline personality disorder.

Study Design

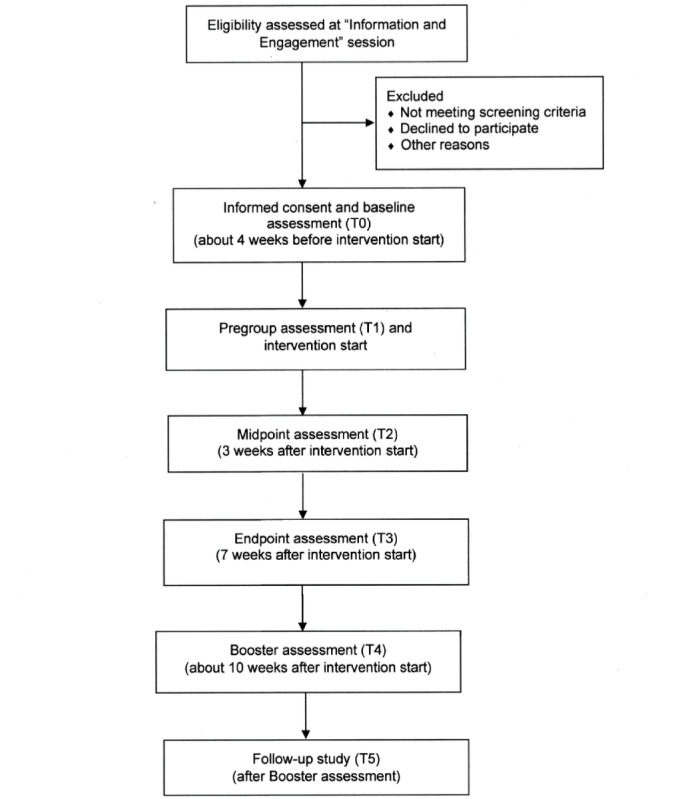

This trial is a multiagency, prospective, longitudinal, nonrandomized, waitlist control, single-group study among Australian adults diagnosed with a psychotic disorder who participate in a routine Recovery ACT group program. The design includes 4 assessment time points: the start of the waitlist period (approximately 4-6 weeks before the start of the group program), the start of the group program (0 weeks), the end of the group program (about 6 weeks after the start of the group program), and the booster session (about 10 weeks after the start of the group program). Some participants may complete outcome measures at the midpoint session (T2, which is 3 weeks after the start of the group program) if the study site is resourced to collect data at an additional time point. Quantitative data from facilitators about participants’ clinical severity and clinical improvement will be collected before, during, and after the group program, as well as relevant demographic and clinical information collected at baseline from participants’ electronic medical records. At either the end of session 7 or the booster session, participants will be asked to provide written consent for study personnel to contact them for a follow-up study. Facilitators will be invited to complete a semistructured interview with senior investigators after each group program to gather qualitative data about the feasibility of the group program in routine practice and to assist in the interpretation of the quantitative measures completed by participants. The protocol development addressed the SPIRIT (Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials; Multimedia Appendix 1) guidelines [36] and intends to adhere to the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials; Figure 1) criteria [37]. We retrospectively registered the trial with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry; Table 1 lists the trial registration data set.

Figure 1.

CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) diagram of the Recovery ACT Trial. ACT: Acceptance and Commitment Therapy.

Table 1.

World Health Organization Trial registration data set.

| Data category | Information | |

| Primary registry and trial identifying number | ANZCTR, ACTRN12620000223932 | |

| Date of registration in primary registry | February 24, 2020 | |

| Secondary identifying numbers | UTN: U1111-1247-8144 | |

| Source of monetary or material support | Royal Melbourne Hospital, NorthWestern Mental Health | |

| Primary sponsor | Royal Melbourne Hospital, NorthWestern Mental Health | |

| Secondary sponsor | La Trobe University | |

| Contact for public enquiries | Dr Eric Morris | |

| Contact for scientific enquiries | Dr Marilyn Cugnetto | |

| Public title | Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) Group Program for Recovery from Psychosis: A Multi-Agency Evaluation | |

| Scientific title | A Multi-agency Evaluation of the Routine Practice of an Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Group for Recovery from Psychosis | |

| Countries of recruitment | Australia | |

| Heath conditions or problems studied | Psychosis, Mental Health, Schizophrenia | |

| Interventions | Treatment: “Recovery ACT for Psychosis” Group Program; comparator or control: single group, waitlist control period | |

| Key inclusion and exclusion criteria | ||

|

|

Inclusion criteria | Inclusion criteria: Out-patients aged between 18 and 65 years; have a primary file diagnosis of either a schizophrenia spectrum or other psychotic disorder, a mood disorder with psychotic features, or a substance-induced psychotic disorder; are currently receiving outpatient mental health care at one of the study centers; are self-referred or referred by clinical staff to a Recovery ACT group being conducted by a participating center. |

|

|

Exclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria: lack of capacity to consent to this evaluation; lack of proficiency in speaking and comprehending English; file diagnosis of an intellectual disability (an intellectual development disorder) or borderline personality disorder. |

| Study type | Interventional | |

| Allocation |

|

|

| Primary purpose | Treatment | |

| Phase | N/Aa | |

| Date of first enrollment | September 13, 2019 | |

| Target sample size | 160 | |

| Recruitment status | Recruiting | |

| Primary outcomes | Personal recovery | |

| Key secondary outcomes | Well-being | |

aN/A: not applicable.

Procedure

Recruitment

Participants will be recruited from current consumers of the services enrolled in a Recovery ACT group program as part of their normal clinical care. Recovery ACT group programs are conducted at all 4 participating sites, either as part of a program of groups offered to consumers or as periodic opportunities. All sites follow the same recruitment plan. Recruitment will continue until the target is met, as long as the clinical services are willing to continue to support the evaluation. Facilitators will describe the group program and the evaluation study at staff meetings and with fellow clinicians at their study site to ensure they are aware that an evaluation of the program is occurring and that consumers will be invited but not obligated to participate. Facilitators will receive all referrals to the group program and contact potential consumers to schedule an “Information and Engagement” session to brief consumers about the group program and confirm their wish to attend. All consumers who enroll in the group program will be screened for eligibility to participate in the evaluation. Consumers who meet the eligibility criteria will be provided with an explanation of the study, an information sheet, and an evaluation brochure, and those who choose to participate will be required to provide written informed consent.

After the completion of a group program (after the booster session), senior investigators will invite facilitators to participate in a semistructured group interview for evaluation purposes and seek informed consent.

Due to the time elapsed from the initial consent process, all group members will be asked again at either session 7 or the booster session for permission and written consent to contact them in the future to invite them to participate in a follow-up study on the experience of participating in the group.

Intervention

The Recovery ACT group program includes 7 core sessions scheduled weekly and a booster session scheduled approximately 4 weeks later. The duration of all sessions is 90 minutes, and they are delivered in person. The intervention is an adaptation of the ACT for Life program [30] that centers on a core metaphor (passengers on the bus) [38] to facilitate consumers’ engagement in value-based actions when relating to their internal experiences (eg, thoughts, feelings, and memories) once they become aware of the internal experiences and are able to defuse (or cognitive distance) from them. The group focuses on developing awareness of internal experiences through metaphors and mindfulness activities and building defusion skills. In the metaphor, the “bus” represents the consumer’s life in the present moment, the “bus driver” is the consumer, and the “passengers” on the bus are the consumer’s internal experiences. The topics covered during the core sessions include: introduction to noticing (mindfulness) of present experiences and values; enacting the core passengers on the bus metaphor and “specific, meaningful, adaptive, realistic, and time-framed” (SMART) goals; review of values, noticing, and willingness; identification of passengers and different ways of responding to them and development of noticing skills; passengers on the bus and changing relationships with words; review of values and encouragement of sharing value-guided actions; and review of key group messages. Brief contact with consumers between sessions is encouraged to promote completion of home practice and to encourage attendance.

There are no specified criteria for discontinuing or modifying the intervention, as this is an evaluation of a group program as conducted in routine clinical practice at local mental health services. Participants can choose to withdraw from the evaluation and remain in the group program. Participants may be withdrawn from the study due to a protocol violation or an adverse event.

Facilitators will be clinical mental health staff employed at a participating public mental health service who, where possible, have participated in an introductory ACT workshop and completed training in Recovery ACT. The group is led by 2 facilitators, one of whom is experienced (ie, has previously led a Recovery ACT group program) and adheres to the Recovery ACT group program manual [39]. Facilitators will be invited to attend a minimum of 3 “Support and Supervision” sessions while facilitating a group. The goal of these sessions is to enhance fidelity to the Recovery ACT group program manual [39]. In addition, facilitators will complete a fidelity log after each group session.

There are no restrictions on concomitant care and interventions, as this is an unfunded evaluation of the Recovery ACT group program that is already offered in routine clinical care at the participating public mental health services. To participate in the Recovery ACT program, participants must be receiving care at the respective public mental health service. As such, participants will receive provisions for ancillary and posttrial care at the public mental health service. The potential risks related to the study are deemed minimal. Facilitators are responsible for participants’ clinical care during the group program, including distress related to study procedures. Participants have a key support clinician for out-of-group issues that may arise.

Outcomes

Timeline

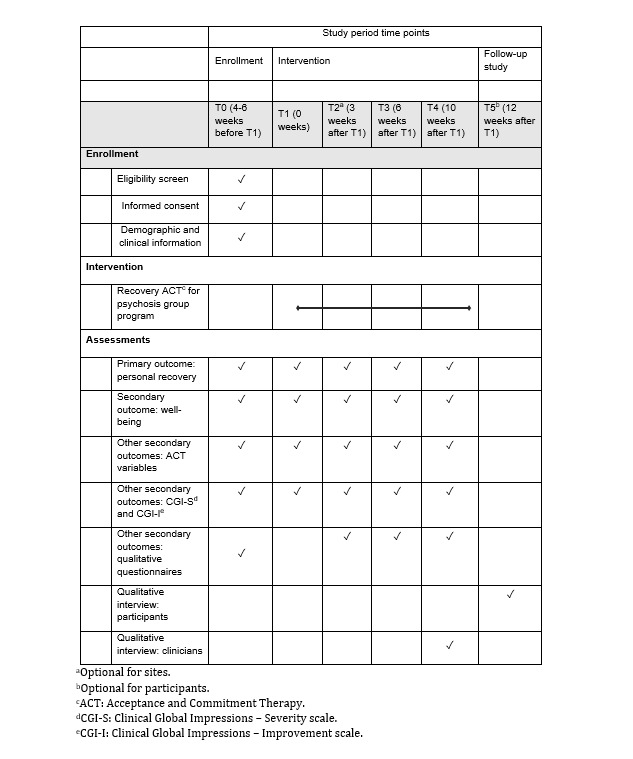

The schedule of enrollment, interventions, and assessments is displayed in Figure 2. The quantitative self-report outcome measures are intended to be completed independently at the start of the waitlist period (T0, approximately 4-6 weeks before the start of the group program, typically at the “Information and Engagement” session), at the start of the group program (T1), at the end of the group program (T3, which is 6 weeks after the start of the group program), and at the booster session (T4, about 10 weeks after the start of the group program). Some participants may complete outcome measures at the midpoint session (T2, which is 3 weeks after the start of the group program) if the study site is resourced to collect data at an additional time point. Measures are completed after the group session, except for at T1, when participants complete measures before the start of the group to ensure no exposure to the program’s content. Participants can request assistance from facilitators to complete the measures. Demographic and clinical information will be obtained from participants’ electronic health records at T0 and will include their date of birth, gender, ethnicity, country of birth, highest level of educational attainment, highest level of employment, current employment status, primary mental health file diagnosis, co-occurring mental health file diagnoses, date of first contact with mental health services, number of listed episodes of outpatient mental health care, and number of psychiatric admissions.

Figure 2.

Schedule of enrollment, interventions, and assessments.

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome is personal recovery, as measured by the 15-item version of the Questionnaire about the Process of Recovery (QPR) [40,41]. The 15-item QPR has good internal consistency (QPR total α=.89), fair to good test-retest reliability (QPR total intracluster correlation coefficient [ICC]=0.74), moderate sensitivity to change, and adequate convergent validity [42]. The QPR is a measure that assesses the 5 core processes of personal recovery that comprise the “Connectedness; Hope and optimism about the future; Identity; Meaning in life; and Empowerment” (CHIME) framework [43], which is currently the strongest conceptualization of personal recovery in serious mental illness. The Recovery ACT group program seeks to support change in these dimensions for participants.

Secondary Outcomes

The secondary outcomes are well-being (Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation 10 [CORE-10]) [44] and 4 psychological flexibility process variables, namely committed action (the Valuing Questionnaire’s Progress scale comprised of items 3, 4, 5, 7, and 9) [45], mindfulness (Southampton Mindfulness Questionnaire) [46], cognitive defusion (Cognitive Fusion Questionnaire) [47], and experiential avoidance (Brief Experiential Avoidance Questionnaire) [48].

Other Clinical Outcomes

A facilitator will rate illness severity at enrollment and before the start of the group using the “Clinical Global Impression–Severity” scale and will rate illness improvement at the end of the group and at the booster session using the “Clinical Global Impression–Improvement” scale [49,50].

Consumer and Facilitator Feedback

Permission will be sought from participants to use their responses to routine qualitative feedback questions for evaluation purposes. These questions ask about their hopes and expectations for the group (at T0), helpful and unhelpful aspects of the group (at T2 and T3), requests for remaining sessions (at T2), and reflection on any perceived changes attributed to the group (at T3 and T4). The method of collecting these routine feedback responses is dependent on the site. The baseline feedback questions (at T0) are typically asked and recorded by a facilitator during the “Information and Engagement” session; the feedback questions at other time points are typically written responses by participants. Qualitative data about the group will be sought from facilitators who consent to participate in a semistructured interview after completing a group. The qualitative interview will assess the feasibility of the group, its evaluation in routine practice, and perceptions of the group program’s effectiveness.

In addition, during the initial consent process, participants will be asked for written consent to contact them in the future to invite them to participate in a follow-up study involving a qualitative interview exploring their experience of participating in the group.

Statistical Methods and Sample Size

We intend to use an intention-to-treat sample to test a univariate latent growth curve model of the primary outcome from before the start of the waitlist period to the start of the group to the booster session in order to compare the trajectory over the waitlist period to the trajectory over the active treatment period. We selected this method of analysis to strengthen our estimations of associations due to the limitations of the nonrandomized study design chosen as the most realistic option for an evaluation of a program already in routine practice [51]. A minimum sample size of 90 is required to conduct the proposed growth curve structural equation model (5 observed variables and 2 latent variables) with an anticipated medium effect size (0.3), α set at .05, and power (1–β) at .80. Univariate latent growth curve models for each of the 5 secondary outcomes will also be tested. If there are sufficient data, we will test whether the trajectory of the 4 psychological flexibility process variables from the start of the group to the midpoint session (T1 to T2) is significantly associated with the trajectory of personal recovery (T2 to T4) using multivariate growth models. We do not predict a priori any differences associated with the study site. We intend to calculate the ICC after the data are collected to determine the relatedness of the data collected at different study sites.

Randomization and Blinding

This study is a nonrandomized (unblinded) trial that uses a single group, waitlist control, and a quasiexperimental design. All participants serve as their own control. The data for all participants on change in outcomes over the waitlist period (no active intervention) will be used to compare with the data on change in outcomes during the active intervention. The planned statistical methods will strengthen our conclusions. The risk of researcher bias is lessened by the self-report format of the primary and secondary outcomes and the opportunity for participants to submit questionnaires in a sealed envelope.

Data Collection and Management

The data will be collected using deidentified hardcopies of all evaluation documents (quantitative questionnaires completed by participants and facilitators, copies of qualitative feedback forms, and demographic and clinical information forms), and other trial documents (attendance records, fidelity logs, and recruitment logs). Facilitators will assist participants with questionnaire completion if needed. As facilitators will serve a dual role as clinical service providers and study personnel, participants will be provided a sealable envelope to return deidentified self-report questionnaires that will be reviewed by study personnel other than their facilitators if sealed (either at the site or by the study coordinator). If a participant does not attend a group session when data are collected, facilitators will attempt to schedule an appointment to complete study measures.

Deidentified data from hard copy evaluation documents will be entered into a password-protected electronic file maintained on secure computers by the study coordinator. A coding sheet with identifiable participant information will be saved as a password-protected electronic file on the sponsor site’s server. Hard copies of consent forms and study documents will be kept in a locked filing cabinet at the Academic Psychology Unit located at the sponsor’s site.

Data Monitoring and Adverse Event Reporting

Anticipated risks to participant safety due to participation in the evaluation and the group are deemed minimal based on pilot study data [35]. Therefore, there is no data monitoring committee, and there are no planned interim analyses to identify risks. Adverse events will be monitored by facilitators, site principal investigators, the coordinating principal investigator, and the Interagency Investigator Committee. An adverse event form and guideline are used.

An Interagency Investigator Committee led by the coordinating principal investigator meets quarterly to oversee the trial’s progress, monitor any adverse events or serious adverse events related to the procedures or the group program, and discuss any necessary protocol modifications. A study coordinator is responsible for liaising with the site principal investigators, who are responsible for the evaluation at each site. In addition to the published Recovery ACT group program manual, evaluation procedure manuals were created to ensure that the protocol is adhered to by study personnel at all sites and over the course of the multiyear study.

Ethical Considerations

Melbourne Health’s Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/51498/MH-2019) provided ethics approval for this study. All methods will be performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations, and written, informed consent will be obtained from participants. The results of the main aim of the study will be published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal and submitted for presentation at clinical and scientific meetings and conferences. The coordinating principal investigator will oversee the publication and presentation of study results, including decisions about authorship. Participants are asked whether they would like to be informed of the main results of the study. Those who express interest and provide contact details will be provided with this information when it is available. Participants who complete quantitative outcome measures will be compensated with a US $6.54 department store voucher at each time point.

Results

Trial enrollment began in September 2019 and was originally planned to continue until at least March 2022. In March 2020, the Victorian Government in Australia introduced public health directions in response to the COVID-19 pandemic that derailed study progress as in-person groups were not permitted for over 20 months at some sites. While study recruitment and follow-up study procedures were broadened to allow for the use of telehealth, the group program format (in-person) was not changed as it would introduce significant variability to the study outcomes. As there remains notable interest from all stakeholders (investigators, facilitators, managers, and consumers), the study will continue to accept enrollments until at least 2024. As of the submission of the manuscript, 93 participants consented to the evaluation, 65 completed T1 measures, and 40 had a complete dataset for the proposed analyses. No data analysis has been conducted. Due to the uncertainty of the trial’s viability due to the public health directions during the COVID-19 pandemic, the protocol’s publication was delayed. The current protocol version is 8.0 (issue date: July 14, 2021).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first trial in Australia evaluating the effectiveness of an ACT for psychosis group program on personal recovery outcomes. Although limited by the single-group design, its strength lies in the opportunity to evaluate effectiveness in routine practice. External validity is strengthened by the practice settings being spread across 4 public mental health networks in a large city, serving communities with a range of sociodemographic characteristics.

A randomized design was not feasible as the program is offered in routine practice [51], thus limiting causal conclusions. However, the quasiexperimental design includes a waitlist period that provides a baseline comparison to evaluate the effectiveness of the group program and can also allow for process analyses if sufficient data are collected. A further enhancement is a proposed qualitative follow-up study of the experience of the group program, intended to inform program development and assist in the interpretation of quantitative results.

A feature of note is the clinician-initiated origin of the evaluation and the forging of a partnership between clinicians and academics during a previous pilot evaluation that then led to the co-design and collaborative implementation of the trial [34]. This clinician-researcher partnership is likely to not only ensure the practical applicability of program modifications and the feasibility of study procedures, but may also lay the foundations for more rapid implementation into practice should the results warrant it. Nonetheless, as an unfunded study, the project is subject to significant risk of noncompletion as it relies on the participating mental health services supporting facilitators to undertake some evaluation tasks, services continuing to provide the group program over the proposed study period, and the support of the sponsor site to provide a study coordinator.

This study exemplifies an effectiveness-implementation hybrid trial [52]. If successful, the trial will further support psychosocial interventions to improve personal recovery among consumers who experience persisting psychotic symptoms.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all facilitators, colleagues, and peer reviewers for their contributions to the development of the protocol, including Ms Sheran Kay. The authors also thank all facilitators who offer their service in kind to collect data, as well as local area managers and department heads at each site. The authors are also grateful to all consumers who participated in the trial.

This is an unfunded study. This study received in-kind support from NorthWestern Mental Health-Royal Melbourne Hospital, St Vincent’s Hospital-Melbourne, Alfred Mental and Addiction Health, Peninsula Health Mental Health Service, and La Trobe University. Participant gift vouchers are courtesy of La Trobe University.

Abbreviations

- ACT

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- CBTp

cognitive behavioral therapy for psychosis

- CHIME

Connectedness; Hope and optimism about the future; Identity; Meaning in life; and Empowerment

- CONSORT

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials

- CORE-10

Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation 10

- ICC

intracluster correlation coefficient

- QPR

Questionnaire about the Process of Recovery

- SMART

specific, meaningful, adaptive, realistic, and time-framed

- SPIRIT

Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials

Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) 2013 Checklist (36).

Data Availability

The data sets generated during or analyzed during this study are not publicly available as the authors do not have research participants’ permission to share data.

Footnotes

Authors' Contributions: JF was the initial coordinating principal investigator; EMJM is the current coordinating principal investigator. JF, EMJM, and MLC led the evaluation development, and all authors contributed. All authors contributed to either the conception, design, or acquisition of ethics and governance approval of the evaluation. MLC and JF were major contributors to writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Saha S, Chant D, Welham J, McGrath J. A systematic review of the prevalence of schizophrenia. PLoS Med. 2005;2(5):e141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020141. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0020141 .05-PLME-RA-0069R1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Charlson FJ, Ferrari AJ, Santomauro DF, Diminic S, Stockings E, Scott JG, McGrath JJ, Whiteford HA. Global epidemiology and burden of schizophrenia: findings from the Global Burden of Disease study 2016. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(6):1195–1203. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sby058. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/29762765 .4995547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emsley R, Chiliza B, Asmal L, Harvey BH. The nature of relapse in schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:50. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-50. https://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-244X-13-50 .1471-244X-13-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Samara MT, Nikolakopoulou A, Salanti G, Leucht S. How many patients with schizophrenia do not respond to antipsychotic drugs in the short term? An analysis based on individual patient data from randomized controlled trials. Schizophr Bull. 2019;45(3):639–646. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sby095. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/29982701 .5047593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kiran C, Chaudhury S. Prevalence of comorbid anxiety disorders in schizophrenia. Ind Psychiatry J. 2016;25(1):35–40. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.196045. http://www.industrialpsychiatry.org/article.asp?issn=0972-6748;year=2016;volume=25;issue=1;spage=35;epage=40;aulast=Kiran .IPJ-25-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson RS, Yung AR, Morrison AP. Comorbidity rates of depression and anxiety in first episode psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2020;216:322–329. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2019.11.035.S0920-9964(19)30542-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dai J, Du X, Yin G, Zhang Y, Xia H, Li X, Cassidy R, Tong Q, Chen D, Teixeira AL, Zheng Y, Ning Y, Soares JC, He MX, Zhang XY. Prevalence, demographic and clinical features of comorbid depressive symptoms in drug naïve patients with schizophrenia presenting with first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2018;193:182–187. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2017.06.029.S0920-9964(17)30369-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jääskeläinen E, Juola P, Hirvonen N, McGrath JJ, Saha S, Isohanni M, Veijola J, Miettunen J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of recovery in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(6):1296–1306. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs130. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/23172003 .sbs130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slade M. Mental illness and well-being: the central importance of positive psychology and recovery approaches. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:26. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-26. https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1472-6963-10-26 .1472-6963-10-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Psychiatric Association . The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Schizophrenia, Third Edition. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK) National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK) Psychosis and Schizophrenia: Treatment and Management. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dixon LB, Dickerson F, Bellack AS, Bennett M, Dickinson D, Goldberg RW, Lehman A, Tenhula WN, Calmes C, Pasillas RM, Peer J, Kreyenbuhl J. The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychosocial treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):48–70. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp115. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/19955389 .sbp115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaebel W, Weinmann S, Sartorius N, Rutz W, McIntyre JS. Schizophrenia practice guidelines: international survey and comparison. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:248–255. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.3.248. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/the-british-journal-of-psychiatry/article/schizophrenia-practice-guidelines-international-survey-and-comparison/E2C0C34325B1AF5DB5FE3CAD7C5CDB06 .S0007125000167637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kingdon DG, Turkington D. Cognitive Therapy of Schizophrenia. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burns AMN, Erickson DH, Brenner CA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for medication-resistant psychosis: a meta-analytic review. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(7):874–880. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300213.1857288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jauhar S, McKenna PJ, Radua J, Fung E, Salvador R, Laws KR. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for the symptoms of schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis with examination of potential bias. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;204(1):20–29. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.116285. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/the-british-journal-of-psychiatry/article/cognitivebehavioural-therapy-for-the-symptoms-of-schizophrenia-systematic-review-and-metaanalysis-with-examination-of-potential-bias/10B5A4BB22C8A82FE55E578A15975753 .S0007125000275119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bighelli I, Salanti G, Huhn M, Schneider-Thoma J, Krause M, Reitmeir C, Wallis S, Schwermann F, Pitschel-Walz G, Barbui C, Furukawa TA, Leucht S. Psychological interventions to reduce positive symptoms in schizophrenia: systematic review and network meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2018;17(3):316–329. doi: 10.1002/wps.20577. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/30192101 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laws KR, Darlington N, Kondel TK, McKenna PJ, Jauhar S. Cognitive behavioural therapy for schizophrenia—outcomes for functioning, distress and quality of life: a meta-analysis. BMC Psychol. 2018;6(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s40359-018-0243-2. https://bmcpsychology.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40359-018-0243-2 .10.1186/s40359-018-0243-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jauhar S, Laws KR, McKenna PJ. CBT for schizophrenia: a critical viewpoint. Psychol Med. 2019;49(8):1233–1236. doi: 10.1017/S0033291718004166. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/psychological-medicine/article/cbt-for-schizophrenia-a-critical-viewpoint/07B2B00BC710F8AAF0A40A998F2002DE .S0033291718004166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKenna P, Leucht S, Jauhar S, Laws K, Bighelli I. The controversy about cognitive behavioural therapy for schizophrenia. World Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):235–236. doi: 10.1002/wps.20636. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/31059624 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hazell CM, Hayward M, Cavanagh K, Strauss C. A systematic review and meta-analysis of low intensity CBT for psychosis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;45:183–192. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.03.004. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0272-7358(16)30102-7 .S0272-7358(16)30102-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waller H, Garety PA, Jolley S, Fornells-Ambrojo M, Kuipers E, Onwumere J, Woodall A, Emsley R, Craig T. Low intensity cognitive behavioural therapy for psychosis: a pilot study. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2013;44(1):98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2012.07.013.S0005-7916(12)00072-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Owen M, Sellwood W, Kan S, Murray J, Sarsam M. Group CBT for psychosis: a longitudinal, controlled trial with inpatients. Behav Res Ther. 2015;65:76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.12.008.S0005-7967(14)00201-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: The Process and Practice of Mindful Change, Second Edition. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cramer H, Lauche R, Haller H, Langhorst J, Dobos G. Mindfulness- and acceptance-based interventions for psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob Adv Health Med. 2016;5(1):30–43. doi: 10.7453/gahmj.2015.083. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/26937312 .gahmj.2015.083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bach P, Hayes SC. The use of acceptance and commitment therapy to prevent the rehospitalization of psychotic patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70(5):1129–1139. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.5.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaudiano BA, Herbert JD. Acute treatment of inpatients with psychotic symptoms using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: pilot results. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44(3):415–437. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.02.007.S0005-7967(05)00063-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tyrberg MJ, Carlbring P, Lundgren T. Brief acceptance and commitment therapy for psychotic inpatients: a randomized controlled feasibility trial in Sweden. Nordic Psychology. 2016;69(2):110–125. doi: 10.1080/19012276.2016.1198271. doi: 10.1080/19012276.2016.1198271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jansen JE, Gleeson J, Bendall S, Rice S, Alvarez-Jimenez M. Acceptance- and mindfulness-based interventions for persons with psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2020;215:25–37. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2019.11.016.S0920-9964(19)30522-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Butler L, Johns LC, Byrne M, Joseph C, O’Donoghue E, Jolley S, Morris EMJ, Oliver JE. Running acceptance and commitment therapy groups for psychosis in community settings. J Contextual Behav Sci. 2016;5(1):33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2015.12.001. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2015.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Donoghue EK, Morris EMJ, Oliver JE, Johns LC. ACT for Psychosis Recovery: A Practical Manual for Group-based Interventions Using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johns LC, Oliver JE, Khondoker M, Byrne M, Jolley S, Wykes T, Joseph C, Butler L, Craig T, Morris EMJ. The feasibility and acceptability of a brief Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) group intervention for people with psychosis: the 'ACT for life' study. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2016;50:257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2015.10.001. https://core.ac.uk/reader/45310513?utm_source=linkout .S0005-7916(15)30032-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jolley S, Johns LC, O'Donoghue E, Oliver J, Khondoker M, Byrne M, Butler L, De Rosa C, Leal D, McGovern J, Rasiukeviciute B, Sim F, Morris E. Group acceptance and commitment therapy for patients and caregivers in psychosis services: feasibility of training and a preliminary randomized controlled evaluation. Br J Clin Psychol. 2020;59(4):524–551. doi: 10.1111/bjc.12265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gates J, Goldstone E, Clemente J, Cugnetto M, Morris EMJ, Farhall J. Adapting and implementing Acceptance and Commitment Therapy groups to support personal recovery of adults living with psychosis: a qualitative study of facilitators’ experiences. Psychosis. 2021;14(4):322–332. doi: 10.1080/17522439.2021.1957991. doi: 10.1080/17522439.2021.1957991. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farhall J, Cugnetto ML, Goldstone E, Gates J, Clemente J, Morris EMJ. Acceptability and feasibility of recovery-oriented group acceptance and commitment therapy for psychosis in routine practice: an uncontrolled pilot study. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2024:1–7. doi: 10.1017/s1352465823000589. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/behavioural-and-cognitive-psychotherapy/article/acceptability-and-feasibility-of-recoveryoriented-group-acceptance-and-commitment-therapy-for-psychosis-in-routine-practice-an-uncontrolled-pilot-study/E768BB831F414FC8C5D11D4C3B5DFCAF . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, Laupacis A, Gøtzsche PC, Krleža-Jerić K, Hróbjartsson A, Mann H, Dickersin K, Berlin JA, Doré CJ, Parulekar WR, Summerskill WSM, Groves T, Schulz KF, Sox HC, Rockhold FW, Rennie D, Moher D. SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(3):200–207. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583. https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/abs/10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub0pubmed .1556168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, CONSORT Group CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c332. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c332. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/20332509 .bmj.c332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hayes SC, Strosahl K, Wilson KG. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An Experiential Approach to Behavior Change. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farhall J, Morris E, Goldstone E, Clemente J, Gates J. Recovery ACT: group intervention for psychosis manual. OSFHome. 2019. [2024-01-23]. https://osf.io/7bwgp .

- 40.Neil ST, Kilbride M, Pitt L, Nothard S, Welford M, Sellwood W, Morrison AP. The Questionnaire about the Process of Recovery (QPR): a measurement tool developed in collaboration with service users. Psychosis. 2009;1(2):145–155. doi: 10.1080/17522430902913450. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Law H, Neil ST, Dunn G, Morrison AP. Psychometric properties of the Questionnaire about the Process of Recovery (QPR) Schizophr Res. 2014;156(2-3):184–189. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.04.011.S0920-9964(14)00169-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Williams J, Leamy M, Pesola F, Bird V, Le Boutillier C, Slade M. Psychometric evaluation of the Questionnaire about the Process of Recovery (QPR) Br J Psychiatry. 2015;207(6):551–555. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.161695. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/the-british-journal-of-psychiatry/article/psychometric-evaluation-of-the-questionnaire-about-the-process-of-recovery-qpr/2625A3198CE62ADC240F23DA6E6F1852 .S0007125000240105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leamy M, Bird V, Le Boutillier C, Williams J, Slade M. Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: systematic review and narrative synthesis. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(6):445–452. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083733. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/the-british-journal-of-psychiatry/article/conceptual-framework-for-personal-recovery-in-mental-health-systematic-review-and-narrative-synthesis/9B3B8D6EF823A1064E9683C43D70F577 .S0007125000256766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Connell J, Barkham M. CORE-10 user manual, version 1.1. APA PsycNet: American Psychological Association. 2007. [2024-01-31]. https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Ft71761-000 .

- 45.Smout M, Davies M, Burns N, Christie A. Development of the Valuing Questionnaire (VQ) J Contextual Behav Sci. 2014;3(3):164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2014.06.001. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2014.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chadwick P, Hember M, Symes J, Peters E, Kuipers E, Dagnan D. Responding mindfully to unpleasant thoughts and images: reliability and validity of the Southampton Mindfulness Questionnaire (SMQ) Br J Clin Psychol. 2008;47(Pt 4):451–455. doi: 10.1348/014466508X314891.299264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gillanders DT, Bolderston H, Bond FW, Dempster M, Flaxman PE, Campbell L, Kerr S, Tansey L, Noel P, Ferenbach C, Masley S, Roach L, Lloyd J, May L, Clarke S, Remington B. The development and initial validation of the cognitive fusion questionnaire. Behav Ther. 2014;45(1):83–101. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2013.09.001. https://core.ac.uk/reader/16701881?utm_source=linkout .S0005-7894(13)00071-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gámez W, Chmielewski M, Kotov R, Ruggero C, Suzuki N, Watson D. The brief experiential avoidance questionnaire: development and initial validation. Psychol Assess. 2014;26(1):35–45. doi: 10.1037/a0034473.2013-33700-001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Busner J, Targum SD. The clinical global impressions scale: applying a research tool in clinical practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2007;4(7):28–37. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/20526405 . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare Public Health Service and Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1655. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/18824488 .337/sep29_1/a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care. 2012;50(3):217–226. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/22310560 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) 2013 Checklist (36).

Data Availability Statement

The data sets generated during or analyzed during this study are not publicly available as the authors do not have research participants’ permission to share data.