Abstract

Long-term nonprogressor AD-18 has been infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) for at least 16 years. During the past 5 years, he has had undetectable levels of plasma viremia, and HIV-1 cannot be isolated from him. Sequencing of proviral DNA indicates that the only HIV-1 sequences that can be identified in AD-18 have gross defects in the p17-encoding regions of the gag gene (Y. Huang, L. Zhang, and D. D. Ho, Virology 240:36–49, 1998). However, AD-18 has strong, sustained antibody responses to several HIV-1 antigens, including p17. Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses to Env and Gag antigens have gradually diminished over the past 4 years, at a time when the titers of antibodies to the same proteins have remained stable. We discuss what these observations might mean for the generation and maintenance of immunological memory.

Long-term nonprogressive infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) is, in a subset of individuals, associated with the presence of defective HIV-1 genomes. Defects in nef (9, 17, 20, 22, 28), gag (15), vpr (22, 31), and long terminal repeat (34) sequences have been recorded. The presence of these viral defects tends to be associated with extremely low viral loads, and in several instances it has not been possible to recover HIV-1 isolates from plasma or other tissues (6). Despite this, immune responses to HIV-1 antigens are strong in long-term nonprogressors (LTNP), usually more so than in individuals with progressive infection (3, 6, 12, 23). This raises the question of what drives the antigen-specific immune responses in the overt absence of virus replication. Here, we report on the immune status of an LTNP (AD-18) who harbors HIV-1 sequences with a grossly defective p17gag sequence (15). Despite this, AD-18 has a strong and persistent antibody response to the p17 protein. In contrast, an initially robust cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) response to both Gag and Env antigens is now declining.

Individual AD-18 has been infected with HIV-1 since at least 1981 and has been studied at our center since 1992 as a member of a cohort of LTNP described in multiple studies (3, 6, 8, 13–15, 33, 34). His infection was acquired through intravenous drug abuse, but he has not engaged in this or other high-risk practices for at least a decade. No samples from prior to 1992 are available. The HIV-1 proviral sequences obtained from infected peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) all contain multiple mutations in, but only in, the p17-encoding section of the gag gene (15). These coding changes are so frequent as to be incompatible with the formation of a normal p17 protein, and it is unlikely that any protein could be expressed from this gene (see reference 15, where AD-18 is referred to as SF). Consistent with this, plasma viremia has been undetectable (<500 RNA copies/ml in the second-generation Chiron branched DNA assay) in AD-18 since he entered our study. Furthermore, no HIV-1 isolate has ever been recovered from AD-18’s cells, despite multiple attempts by means of PBMC coculture with and without prior CD8+ T-cell depletion. Neither has HIV-1 RNA been detected by reverse transcription-PCR assay of these cells. However, we have not been able to obtain lymphoid tissue samples for similar analyses.

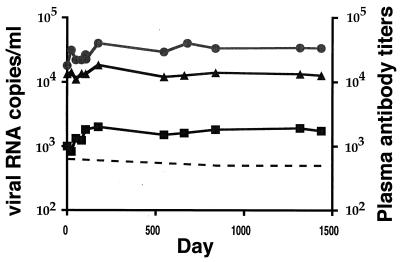

Plasma antibody responses to the HIV-1 gp120, p24, and p17 proteins were assayed in longitudinal samples from AD-18, as described previously (3). Antibody titers are given as the dilutions of plasma at which half-maximal optical densities were measured. During the 4 years of study, titers of antibodies to all three antigens remained stable and high (Fig. 1). Of particular note was the anti-p17 response: the sustained titer of approximately 1:2,000 is, in our experience with progressing and nonprogressing individuals, high (3). Note that, throughout this period, only defective proviral p17 sequences could be obtained from PBMC from AD-18 (15).

FIG. 1.

Longitudinal, midpoint titers of antibodies to MN gp120 (•), p24 (▴), and p17 (▪). Day 0 corresponds to the first plasma assayed, beginning on 9 September 1993. Plasma viral load is indicated by the dotted line.

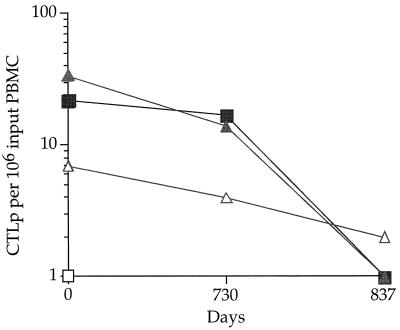

CTL responses to Env and Gag antigens were also measured longitudinally, with a standard 51Cr release assay adapted to a BIOMEK-2000 robot with BIOWORKS software (Beckman Instruments, Inc., Fullerton, Calif.) (16). The autologous B-lymphoblastoid cell line targets were infected with either wild-type vaccinia virus (control) or recombinant vaccinia viruses expressing IIIBgag, SF2gag, IIIBenv, or SF2env (16). CTL precursor (CTLp) frequencies were calculated as described previously (19, 32) and expressed as the numbers of CTLp per 106 input PBMC. Significant numbers of CTLp specific for both IIIB and SF-2 Gag proteins (22 per 106 PBMC) were detected at the earliest time point tested (September 1993, at least 12 years after initial HIV-1 infection of AD-18) (Fig. 2). However, by November 1995, Gag-specific CTLp were no longer detectable in plasma from AD-18. AD-18 also had low, but gradually declining, levels of CTLp to the SF-2, but not to the IIIB, Env protein (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Longitudinal CTLp responses to IIIBgag (▪), SF2gag (▴), IIIBenv (□), and SF2env (▵), expressed as CTLp per 106 input PBMC. Day 0 corresponds to the first plasma assayed, beginning on 9 September 1993.

It was not unexpected that the LTNP AD-18 had strong, stable antibody responses to HIV-1 antigens in the absence of detectable plasma virus; we had observed this previously (3). However, the presence of sustained antibody responses to p17 was surprising, given that the only HIV-1 sequences we have ever been able to obtain from AD-18 are grossly defective in the p17-coding region (15). The observation of a sustained antibody response to an apparently defective HIV-1 protein may not, however, be without precedent, for a similar finding has been noted in studies of Australians infected with a Nef-defective HIV-1 strain (9, 10). In that study, strong anti-Nef antibody responses measured using sequential peptides can be detected in regions of the Nef protein that are no longer encoded by HIV-1 genomes that can be isolated from these individuals. What, then, is sustaining the antibody response to p17 in AD-18 and to Nef in the Australian individuals? There are several possibilities, each with interesting implications for our understanding of the nature of immune responses to viral antigens. At present, we cannot adjudicate between them, but we favor the first theory.

(i) FDC acts as a storage unit.

At some stage during the early years of HIV-1 infection (before the individual joined our LTNP study), productive virus replication occurred in AD-18 and a long-lived store of nonreplicating viral antigen (including intact p17 protein) was laid down on follicular dendritic cells (FDCs) (1, 2, 4, 7, 11). This hypothesis is supported by the finding that, while combination antiretroviral therapy results in undetectable follicular HIV-1 RNA (measured by in situ hybridization) after 3 months, HIV-1 p24 can be readily detected by immunostaining at the same time, suggesting that antigen may have a much longer half-life on FDC than virus (30). Such an antigen store could drive antibody production even after immunological or virological processes rendered the AD-18 virus defective (by accumulation of mutations leading to a nonfunctional p17-coding region, and thus a block in virus assembly).

(ii) Immunological-memory theory.

Immunological memory has been created to such an extent in AD-18 that sustained antibody secretion occurs in the absence of viral antigens, perhaps due to the presence of long-lived memory cells. However, it must be noted that continuous antibody production, most likely from antibody-secreting cells in bone marrow, would be necessary to sustain such high plasma antibody titers in AD-18. This is not known to be antigen independent (1, 2).

(iii) Privileged-site theory.

Intact p17-coding sequences are present in some privileged site that is not in rapid equilibrium with blood, and sufficient p17 antigen production occurs in that site to sustain an antibody response. Since we have been unable to obtain lymph node or bone marrow biopsies from AD-18, we cannot eliminate this possibility.

It is notable that the CTL and antibody responses in AD-18 appear to be differentially regulated. During the 2- to 3-year period (1993 to 1996) when the CTLp frequency decreases markedly, there is no change in anti-Gag antibody titers. It may be that maintenance of CTL responses is more dependent on de novo synthesis of antigen. A general cessation of HIV-1 antigen production would account for the observation that CTLp frequencies for all HIV-1 antigens (and not just for p17) diminish over this period. Anti-HIV-1 CTLp have a half-life of about 3 days (27), and fresh CTL have a half-life of <1 day (5, 18, 25, 26). It should be noted, however, that, although CTLp and effector CTL loss occurs relatively quickly, this does not imply a rapid loss of CTL memory.

We do not know when between 1981 and 1993 AD-18 cleared replicating virus, leaving only defective proviral sequences in PBMC. However, that he has a high-titer antibody response to multiple antigens suggests that viremia was initially sustained for at least a year; it takes this long to generate a fully mature response (3, 4, 24). That CTLp were readily detectable at the earliest time point (1993) perhaps suggests that replicating virus might have been cleared at some time close to this first sampling. The CTLp frequencies measured in the 1993 sample (Fig. 2) are at the lower end of the range typically observed for LTNP (50 to 1,000/106 PBMC [29]). Thus, they may have been declining for some time prior to 1993, although we clearly cannot be certain of this.

Antibody titers are also strongly sustained in the absence of detectable plasma viremia in individuals who have been infected with HIV-1 for several years and who are then treated with combination antiretroviral therapy (4, 21). Some of these individuals have undetectable plasma viremia for 20 months without any diminution in their titers of antibodies to Env antigens (4, 21). We note, however, that antibody titers are sensitive to reductions in plasma viremia (or, more strictly, to reductions in body-wide HIV-1 replication) if therapy is initiated within about a year of HIV-1 infection (21). At some stage, we presume that one (or more) of the mechanisms outlined above becomes relevant to antibody production in the absence of significant levels of circulating virus. Our working hypothesis is that the number of memory CTL, as measured by limiting dilution assay, declines due to lack of viral replication (1, 26), whereas antibody responses are driven by nonreplicating antigen trapped on FDCs in germinal centers (1, 2, 12). The relationship between the humoral and cellular immune responses and HIV-1 replication in the recipients of combination antiviral therapy will be fully described elsewhere (21).

The nature of immunological memory (especially B-cell memory) is poorly understood (1, 2). In this report, we document a phenomenon of differential maintenance of immune responses to a defective HIV-1 strain. We can only hypothesize about the underlying mechanisms, in the hope that this may provoke studies designed to more fully understand the nature of sustained immune responses to viral antigens. Interestingly, the immunological observations we have made with AD-18 are similar to those made with acute infections with viruses that differ from HIV-1 by being efficiently cleared by antiviral immune responses (1).

Acknowledgments

We thank Brian Clas, Caroline Roberts, and Pei Zhou for technical assistance. We also thank Dale McPhee, John Mills, and Wayne Dyer for consultation on the Australian cohort.

This study was supported by Innovations Grant R21 AI42721 and by contract NO1 AI45218: “Correlates of HIV Immune Protection.”

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed R, Gray D. Immunological memory and protective immunity: understanding their relation. Science. 1996;272:54–60. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachmann M F, Kündig T M, Odermatt B, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel R M. Free recirculation of memory B cells versus antigen-dependent differentiation to antibody forming cells. J Immunol. 1994;153:3386–3397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Binley J M, Klasse P J, Cao Y, Jones I, Markowitz M, Ho D D, Moore J P. Differential regulation of the antibody responses to Gag and Env proteins of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1997;71:2799–2809. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.2799-2809.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binley J M, Markowitz M, Cao Y, Hurley A, Ho D D, Moore J P. Abstracts of the 4th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. 1997. Differential regulation of the antibody responses to gag and env proteins of HIV-1; effects of combination antiviral therapy, abstr. 384. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonhoeffer S, May R M, Shaw G M, Nowak M A. Virus dynamics and drug therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6971–6976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao Y, Qin L, Zhang L, Safrit J, Ho D D. Virologic and immunologic characterization of long-term survivors of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:201–208. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501263320401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cavert W, Notermans D W, Staskus K, Weitgrefe S W, Zupancic M, Gebhard K, Henry K, Zhang Z, Mills R, McDade H, Goudsmit J, Danner S A, Haase A T. Kinetics of response in lymphoid tissues to antiretroviral therapy of HIV-1 infection. Science. 1997;276:960–964. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5314.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Connor R I, Sheridan K E, Lai C, Zhang L, Ho D D. Characterization of the functional properties of env genes from long-term survivors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 1996;70:5306–5311. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5306-5311.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deacon N J, Tyskin A, Solomon A, Smith K, Ludford-Menting M, Hooker D J, McPhee D A, Greenaway A L, Ellet A, Chatfield C, Lawson V A, Crowe S, Maerz A, Sonza S, Learmont J, Sullivan J S, Cunningham A, Dwyer D, Dowton D, Mills J. Genomic structure of an attenuated quasi species of HIV-1 from a blood transfusion donor and recipients. Science. 1995;270:988–991. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5238.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenway, A. L., J. Mills, D. Rhodes, N. J. Deacon, and D. A. McPhee. Serologic detection of attenuated HIV-1 variants with nef gene deletions. AIDS, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Haase A T, Henry K, Zupancic M, Sedgewick G A, Faust R A, Melroe H, Cavert W, Gebhard K, Staskus K, Zhang Z, Dailey P J, Balfour H H, Jr, Erice A, Perelson A S. Quantitative image analysis of HIV-1 infection in lymphoid tissue. Science. 1996;274:985–989. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5289.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harrer T, Harrer E, Kalams S A, Elbeik T, Staprans S I, Feinberg M B, Cao Y, Ho D D, Yilma T, Caliendo A M, Johnson R P, Buchbinder S P, Walker B D. Strong cytotoxic T cells and weak neutralizing antibody responses in a subset of persons with stable nonprogressing HIV type 1 infection. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1996;12:585–592. doi: 10.1089/aid.1996.12.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang Y, Zhang L, Ho D D. Characterization of nef sequences in long-term survivors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 1995;69:93–100. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.93-100.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang Y, Zhang L, Ho D D. Biological characterization of nef in long-term survivors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 1995;69:8142–8146. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.8142-8146.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang Y, Zhang L, Ho D D. Characterization of gag and pol sequences from long-term survivors of human immunodeficiency type 1 infection. Virology. 1998;240:36–49. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin, X., C. G. P. Roberts, D. F. Nixon, Y. Cao, D. D. Ho, B. D. Walker, M. Muldoon, B. T. Korber, R. A. Koup, and the ARIEL Project Investigators. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Kirchhoff F, Greenough T C, Brettler D B, Sullivan J L, Desrosiers R C. Absence of intact nef sequences in a long-term survivor with nonprogressive HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:228–232. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501263320405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klenerman P, Phillips R E, Rinaldo C R, Wahl L M, Ogg G, May R M, McMichael A J, Nowak M A. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes and viral turnover in HIV type 1 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:15323–15328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koup R A, Safrit J T, Cao Y, Andrews C A, McLeod G, Borkowsky W, Farthing C, Ho D D. Temporal association of cellular immune response with the initial control of viremia in primary HIV-1 syndrome. J Virol. 1994;68:4650–4655. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.7.4650-4655.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mariani R, Kirchhoff F, Greenough T C, Sullivan J L, Desrosiers R C, Skowronski J. High frequency of defective nef alleles in a long-term survivor with nonprogressive human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 1996;70:7752–7764. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7752-7764.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Markowitz, M., M. Vesanen, K. Tenner-Racz, Y. Cao, J. M. Binley, A. Talal, A. Hurley, X. Jin, M. Rashid Chaudhdry, M. Health-Chiozzi, J. M. Leonard, J. P. Moore, P. Racz, D. F. Nixon, and D. D. Ho. The impact of commencing combination antiretroviral therapy soon after HIV-1 infection on virus replication and antiviral immune responses. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Michael N L, Chang G, d’Arcy L A, Tseng C J, Ehrenberg P K, Mariani R, Busch M P, Birx D L, Schwartz D H. Defective accessory genes in a human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected long-term survivor lacking recoverable virus. J Virol. 1995;69:4228–4236. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4228-4236.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montefiori D C, Pantaleo G, Fink L M, Zhou J T, Bilska M, Miralles G D, Fauci A S. Neutralizing and infection-enhancing antibody responses to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in long-term nonprogressors. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:60–67. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore J P, Cao Y, Ho D D, Koup R A. Development of the antibody response during seroconversion to human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1994;68:5142–5155. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.5142-5155.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nowak M A, Bangham C R. Population dynamics of immune responses to persistent viruses. Science. 1996;272:74–79. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ogg, G. S., X. Jin, S. Bonhoeffer, P. R. Dunbar, M. A. Nowak, S. Monard, J. Segal, Y. Cao, S. L. Rowland-Jones, V. Cerundolo, A. Hurley, M. Markowitz, D. D. Ho, D. F. Nixon, and A. J. McMichael. The number of circulating HIV-1 specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes is inversely correlated with plasma viral load. Science, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Ortiz, G., P. J. Kuebler, X. Jin, S. Bonhoeffer, W. M. Kakimoto, Y. Cao, D. D. Ho, M. Markowitz, and D. F. Nixon. Unpublished data.

- 28.Premkumar D R D, Ma X-Z, Maitra R K, Chakrabarti B K, Salkowitz J, Yen-Lieberman B, Hirsch M S, Kestler H W. The nef gene from a long-term HIV type 1 nonprogressor. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1996;12:337–345. doi: 10.1089/aid.1996.12.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rinaldo C, Huang X L, Fan Z F, Ding M, Beltz L, Logar A, Panicali D, Mazzara G, Liebermann J, Cottrill M, Gupta P. High levels of anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) memory cytotoxic T-lymphocyte activity and low viral load are associated with lack of disease in HIV-1-infected long-term nonprogressors. J Virol. 1995;69:5838–5842. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5838-5842.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tenner-Racz, K., H.-J. Stellbrink, J. van Lunzen, C. Schneider, J.-P. Jacobs, B. Raschodorff, G. Großschupff, R. S. Steinman, and P. Racz. The unenlarged lymph nodes of HIV-1 infected, asymptomatic patients with high CD4 T cell counts are sites for virus replication and CD4 T cell proliferation. The impact of antiretroviral therapy. J. Exp. Med., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Wang B, Ge Y-C, Palasanthiran P, Xiang S-H, Zeigler J, Dwyer D E, Randle C, Dowton D, Cunningham A, Saksena N K. Gene defects clustered at the C terminus of the vpr gene of HIV-1 in long-term nonprogressing mother and child pair: in vivo evolution of vpr quasispecies in blood and plasma. Virology. 1996;223:224–232. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wills M R, Carmichael A J, Mynard K, Jin X, Weekes M P, Plachter B, Sissons J G P. The human cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) response to cytomegalovirus is dominated by structural protein pp65: frequency, specificity, and T-cell receptor usage of pp65-specific CTL. J Virol. 1996;70:7569–7579. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7569-7579.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang L Q, Huang Y X, Yuan H, Tuttleton S, Ho D D. Genetic characterization of vif, vpr, and vpu sequences from long-term survivors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Virology. 1997;228:340–349. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.8378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang L Q, Huang Y X, Yuan H, Chen B K, Ip J, Ho D D. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of long terminal repeat sequences from long-term survivors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 1997;71:5608–5613. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5608-5613.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]