Abstract

Objective

To examine the effectiveness of psychoeducational interventions on depression, anxiety, and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) for people undergoing maintenance hemodialysis (MHD).

Methods

This review used systematic review and meta-analysis as the research design. Nine databases, including PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, CINAHL Complete, Cochrane Library, CNKI, WanFang, VIP, and Chinese Biomedical Literature Database, were searched from the inception to the 8th of July 2023. Two reviewers independently identified randomized controlled trials (RCT) examining the effects of psychoeducational interventions on MHD patients.

Results

Fourteen studies involving 1134 MHD patients were included in this review. The results of meta-analyses showed that psychoeducational intervention had significant short-term (< 1 m) (SMD: −0.87, 95% CI: −1.54 to −0.20, p = 0.01, I2 = 91%; 481 participants), and medium-term (1–3 m) (SMD: −0.29, 95% CI: −0.50 to −0.08, p = 0.01, I2 = 49%; 358 participants) on anxiety in MHD patients, but the effects could not be sustained at longer follow-ups. Psychoeducational interventions can also have short-term (< 1 m) (SMD: −0.65, 95% CI: −0.91 to −0.38, p < 0.00001, I2 = 65%; 711 participants) and medium-term (1–3 m) (SMD: −0.42, 95% CI: −0.76 to −0.09, p = 0.01, I2 = 69%; 489 participants) effects in reducing depression levels in MHD patients. Psychoeducational interventions that use coping strategies, goal setting, and relaxation techniques could enhance the QOL in MHD patients in the short term (< 1 m) (SMD: 0.86, 95% CI: 0.42 to 1.30, p = 0.02, I2 = 86%; 241 participants).

Conclusions

Psychoeducational interventions have shown great potential to improve anxiety, depression, and quality of life in patients with MHD at the short- and medium-term follow-ups.

Trial registration number: CRD42023440561.

Keywords: Maintenance hemodialysis, psychoeducational interventions, quality of life, meta-analysis, systematic review

1. Background

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is one of the most striking global health problems, with up to 18.98 million new cases and 697.29 million people living with CKD in 2019 [1]. CKD is characterized by kidney damage with proteinuria, hematuria, and progressive loss of renal function [2, 3], and non-reversely develops to the incurable and life-threatening final stage of end-stage kidney disease (ESRD) [4]. For people suffering from ESRD, kidney replacement therapy, including kidney transplantation, hemodialysis, and peritoneal dialysis, is the only way to prolong their lives. The number of people receiving kidney replacement treatment globally is estimated to exceed 5.4 million by 2030 [5], among which over 80% of ESRD patients will undergo maintenance hemodialysis (MHD) [6, 7].

Maintenance hemodialysis is time-consuming as patients must visit the blood purification center thrice a week for about four hours each time [8]. Besides, MHD patients must pay close attention to their diet and fluid intake, physical activity, and medication to maintain good treatment outcomes during hemodialysis [9]. These place a heavy burden on patients and have a profound impact on their mental health and quality of life. Up to half, and even more than 95%, of people with MHD experience anxiety, depression, and other psychological distress [10–12]. Moreover, MHD patients have a poorer quality of life than the average standard [13, 14]. Anxiety and depression are common yet frequently overlooked psychological symptoms in patients undergoing MHD therapy [15]. These symptoms may be caused by physical and cognitive impairments, challenging treatment routines, limitations in daily activities, fear of death, physical symptoms, fatigue, and reliance on others [16]. According to research reports, 20% to 40% of people with MHD have depression, and the risk is three to four times that of the general population or people with other chronic diseases [17]. Anxiety and depression are often psychological distress, which seriously affect the QOL of MHD patients.

In recent years, more and more studies have been on improving patients’ quality of life [18, 19]. Several previous reviews have summarized effective non-pharmacological interventions for improving health-related quality of life in patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis, including psychosocial interventions, cognitive behavioral therapy interventions, physical exercise, and sensory training [20–24]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis [25] showed that psychosocial interventions, which are any interventions used to modify behavior, emotional state, or feeling, could reduce anxiety (SMD − 0.99, 95%CI − 1.65 − 0.33, p < 0.01) and depression (SMD − 0.85, 95%CI − 1.17 − 0.52, p < 0.01) in adult hemodialysis patients, with some beneficial effects on quality of life. However, this review included studies that used randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi-randomized controlled trials (quasi-experimental), which may limit analysis results, and these studies were not sufficiently specific in their scope of interventions and did not analyze and evaluate the characteristics of the interventions. Therefore, a systematic review is needed explicitly examining the effectiveness of psychological interventions on health-related quality of life in patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis to identify intervention characteristics that may optimize the effects of these interventions on quality of life.

Psychoeducational interventions are an intervention strategy that combines psychological counseling and education to provide patients and/or family caregivers with education in relevant subject areas to enhance their understanding and support, learn to recognize warning signs and mood changes early, and improve treatment compliance [26, 27]. Psychoeducational interventions that provide information, education, and psychological support to patients and/or their informal caregivers, such as gynaecological cancer [28], adolescent hyperactivity [29], and stroke [30], are effective and have been systematically assessed. However, there is currently no evidence to have been found to determine the impact, content, and effectiveness of dyad psychoeducational interventions for MHD patients and caregivers on the health-related quality of life of the patients.

Therefore, based on the existing literature, this systematic review aims to identify the best available evidence on the effectiveness of currently available psychoeducational interventions on health-related quality of life in patients with MHD. The objectives of this review are two-fold: (1) to evaluate the effectiveness of psychoeducational interventions for MHD patients with depression, anxiety, HRQOL and/or their family caregivers on anxiety, depression, HRQOL (primary outcome), and family caregivers’ anxiety, depressive, and caregiver burden; and (2) to identify the characteristics of psychoeducational interventions that have optimal effects on managing HRQOL. Provide references for researchers and clinical healthcare professionals to support people with MHD and identify gaps that need further exploration. Researchers and clinical healthcare professionals can utilize this systematic review as a guide to assist patients with MHD while also identifying areas that require further investigation.

2. Methods

This review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines [31]. The review protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) in July 2023 and registered with CRD42023440561.

2.1. Search strategy

Nine databases, including six English databases (PubMed, Web of Science, CINAHL Complete, Cochrane Library, and Embase) and four Chinese databases (CNKI, WanFang, VIP, SinoMed), were searched from the inception to the 8 July 2023. A comprehensive database search was conducted using subject terms and free words (detailed search strategies of PubMed were shown in the supplementary file, Table 1). In addition, the ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global (PQDT Global) and WanFang Data Theses were searched for grey literature. Reference lists of included studies and related reviews were also searched.

Table 1.

JBI Critical appraisal checklist for randomized controlled trials.

| Study | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 | Q13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bahraseman 2021 [41] | Y | U | Y | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Chan 2022 [42] | Y | Y | Y | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Chen 2021 [18] | Y | Y | N | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Cukor 2014 [43] | Y | Y | Y | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Durmuş 2021 [44] | Y | Y | Y | N/A | N/A | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Erdley 2014 [38] | Y | Y | N | N/A | N/A | N | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Espahbodi 2015 [36] | Y | U | Y | N/A | N/A | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| He 2008 [37] | Y | U | Y | N/A | N/A | U | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Hou 2014 [45] | Y | Y | Y | N/A | N/A | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Jenkins 2021 [46] | Y | Y | Y | N/A | N/A | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Lerma 2017 [47] | Y | Y | Y | N/A | N/A | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Saraireh 2018 [40] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N/A | U | U | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Shareh 2022 [48] | Y | Y | Y | N/A | N/A | U | -Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Tsay 2005 [39] | Y | Y | N | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

N: no; N/A: not available; U: unclear; Y: yes.

Q1: Was true randomization used for the assignment of participants to treatment groups?; Q2: Was allocation to treatment groups concealed?; Q3: Were treatment groups similar at the baseline?; Q4: Were participants blind to treatment assignment?; Q5: Were those delivering treatment blind to treatment assignment?; Q6: Were outcomes assessors blind to treatment assignment?; Q7: Were treatment groups treated identically other than the intervention of interest?; Q8: Were follow-up complete, and if not, were differences between groups in terms of their follow-up adequately described and analyzed?; Q9: Were participants analyzed in the groups to which they were randomized?; Q10: Were outcomes measured in the same way for treatment groups?; Q11: Were outcomes measured reliably?; Q12: Was appropriate statistical analysis used?; Q13: Was the trial design appropriate, and were any deviations from the standard RCT design (individual randomization, parallel groups) accounted for in the conduct and analysis of the trial?.

2.2. Eligibility criteria

The PICOs framework was used to define the study eligibility criteria:

2.2.1. Participants

Studies involving adult hemodialysis patients (at least 18 years of age) and/or their family caregivers (at least 18 years of age). Family caregivers are family members, such as spouses, children, siblings, and relatives, who provide unpaid physical, practical, and/or emotional care to the patient [32].

2.2.2. Interventions

Psychoeducational intervention in this review refers to interventions combining psychotherapeutic techniques (cognitive reappraisal, behavioral activation, social support, and etc.) and education to improve MHD patients’ psychological distress and/or QOL [26].

2.2.3. Comparison

The control group could be usual control, no-treatment control, attention placebo control, or wait-list control.

2.2.4. Outcomes

The primary outcome of this review were psychological distress (e.g., depression, anxiety, and stress) and QOL of MHD patients. Secondary outcomes included family caregivers’ psychological distress and caregiver burden.

2.2.5. Study design

Only RCTs were eligible for this review. Study protocols, conference abstracts, commentaries, and ongoing studies were excluded.

2.3. Study selection and data extraction

The studies retrieved from the database were downloaded and imported into EndNoteTM20 literature management software for sorting. The software was used to remove duplicates, and then the studies were screened according to the eligibility criteria by two independent reviewers (LYZ and LZ). Any disagreements will be resolved by discussion or, consultation with the third review author (LJZ).

Two independent reviewers (LYZ and LZ) extracted data from included studies based on a pre-designed data extraction table, including study characteristics (e.g., author, year, and country), participant characteristics (e.g., sample size, age, and sex), intervention characteristics (e.g., components, theoretical framework, intervener, delivery mode, dose, intervention sites, control group), and outcome assessments (e.g., assessment time point, outcome measures, effect size). Discrepancies were resolved by discussion or, consultation with the third reviewer (LJZ) if necessary.

2.4. Study appraisal

The RCTs were independently evaluated by two reviewers (LYZ and LZ) using the Joanna Briggs Institute Statistics Assessment and Review Instruments critical appraisal checklists [33]. This assessment tool focuses on two domains of internal authenticity and statistical conclusion authenticity, measuring the presence or absence of selection and distribution-related bias, intervention/expose-related bias, outcome measure bias, and participant missing follow-up bias. Each item on these checklists was assessed as ‘yes,’ ‘no,’ ‘unclear,’ or ‘not applicable.’ Consensus was reached through discussiones with the third author (LJZ) if necessary.

2.5. Data synthesis

This review used meta-analysis by Review Manager 5.4 software of the Cochrane Collaboration was used when at least three studies reported the same outcome under a certain follow-up time point (short-term: ≤1 month; middle-term: 1 to 6 months; long-term: ≥ 6 months after intervention); Otherwise, descriptive analysis is presented through narrative summary. Data synthesis was based on the mean (M) and standard deviation (SD and the intervention effect size was calculated by standardized mean difference (SMD)). The effect size was interpreted as small (0.2), medium (0.5), and large (0.8), respectively [34, 35]. Subgroup analysis was used to examine the influence of moderating variables on the intervention effect. Q test and I2 value were used to test the heterogeneity of the included studies. Considering the heterogeneous intervention characteristics (e.g., intervention components and intervention dose) and participant characteristics (e.g., age, sex and dialysis time), random-effect models were applied. Sensitivity analyses were also conducted to assess the robustness of results using the leave-one-out method, removing one study each time and repeating the meta-analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Search results

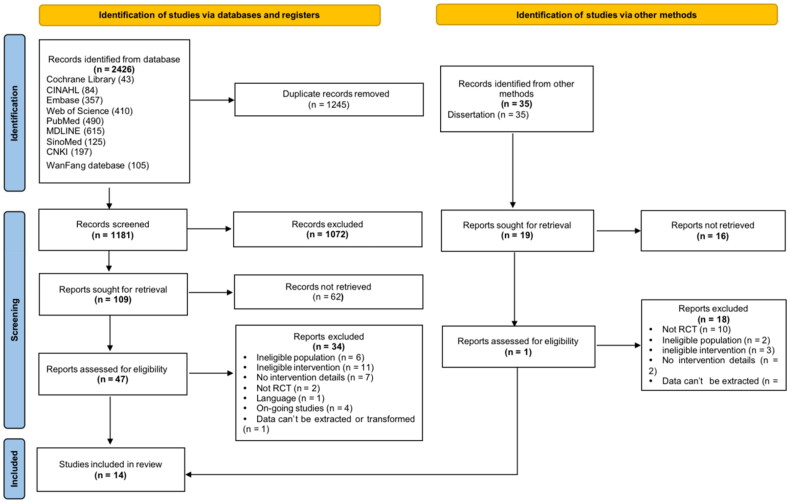

A total of 2426 potentially relevant studies were identified from the electronic databases, and 1245 duplicates were removed. After the screening of the title and abstract, 1072 out of the remaining 1181 studies that did not meet the eligibility criteria were excluded, and 109 studies were remained for full-text review. Eventually, 13 studies were included for the review after full-text review. In addition, 35 studies were identified from grey literature search and reference lists search, and one study met the eligibility criteria was included. Eventually, 13 English-language studies and one Chinese-language study were included for this review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study selection flow diagram (according to PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews).

3.2. Study quality

The quality assessment results of all included 14 studies are shown in Table 2. Participants in all included studies were randomly assigned, using computer-generated random numbers methods. In terms of allocation concealment, two studies [36, 37] provided no information and were assessed as unclear. The baseline of most of the 14 studies was homogeneous, but three out of 14 studies [18, 38, 39] found some baseline imbalance (e.g., in health information teaching clinic attendance, HADS-depression score and effects of kidney disease on daily [18], and in PHQ9 score [38], and in stress and depression score [39]).

Table 2.

Characteristics of psychotherapeutic techniques.

| Study | Coping strategies | Emotion regulation | Goal setting | Problem-solving | Relaxation techniques | Behavioral modification | Social support |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bahraseman et al. 2021 [41] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Chan et al. 2022 [42] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Chen et al. 2021 [18] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Cukor et al. 2014 [43] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Durmuş et al. 2021 [44] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Erdley et al. 2014 [38] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Espahbodi et al. 2015 [36] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| He, 2008 [37] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Hou et al. 2014 [45] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Jenkins et al. 2021 [46] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Lerma et al. 2017 [47] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Saraireh et al. 2018 [40] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Shareh et al. 2022 [48] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Tsay et al. 2005 [39] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

One study [40] blinded participants of the treatment assignments using attention placebo control. In 5 studies [18, 39, 41–43], the outcome assessors were blinded. In most of the studies, the same treatment was used in both groups, except for the intervention. Most studies have adequately described differences in follow-up. All studies were analyzed according to randomized groups. Outcomes were measured identically and reliably in all studies. All studies used appropriate statistical analysis methods and were designed according to standard RCTs.

3.3. Study characteristics

This review included 14 RCTs, among which four studies [37, 39, 42, 44] were conducted in China, three [36, 41, 45] in Iran, two [38, 43] in America, and one study in Singapore [18], Turkey [46], Australia [47], Mexico [48], and Jordan [40], respectively. These studies were published between 2005 and 2022.

3.4. Participants characteristics

Fourteen studies involving 1134 MHD patients were included in this review. The sample size of included studies ranged from 32 [37] to 154 [18]. The attrition rate of all studies ranged from 3.3% [41] to 48.8% [47]. Among the included participants, nearly half (517/1134, 45.6%) were male, with the proportion in individual studies ranging from 27.3% [43] to 65.6% [38]. The average age of all participants varied between 41 [48] to 73 years old [38].

3.5. Interventions characteristics

3.5.1. Intervention components

All included studies applied education together with psychotherapeutic techniques. ESRD-related information including treatments [36, 40, 42], medication and diet management [18, 37, 40, 47], dialysis care [18, 36, 37], monitoring blood pressure and blood sugar [18], dealing with problematic symptoms [39], exercise and sleep management [45, 47] using booklets [18], online platforms [47], face-to-face [18, 36, 37, 39, 40, 42, 45, 47] education.

In addition, the educational content of the other seven studies involved the education of psychological knowledge, including what is stress [41, 48], anxiety and depression [38, 43, 45], and the introduction of ways to improve these problems and spiritual sustenance [46].

In terms of psychotherapeutic techniques, emotion regulation [18, 37, 39–43, 45–48], coping strategies [18, 36–41, 46, 48], relaxation techniques [18, 36, 37, 39, 40, 44–46, 48], problem-solving [18, 36, 38–40, 42, 46, 47], goal-setting [18, 37–39, 42, 48], behavioral modification [43, 44, 48] were used in included studies. Emotion regulation, the use of cognitive resources to alter emotional responses [49], was the most commonly used technique in the included studies to help MHD patients maintain good and stable emotions. Additionally, social support [37, 39, 43, 47] from increasing peer support, creating support networks, and seeking family help were used in the included studies. Specific details on the characteristics of the psychotherapy technique are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| Study/Country | Participants (Intervention group/Control Group) |

Intervention | Assessments Timepoints /Outcomes | Findings | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | Mean age | Sex, men % | ||||

| Bahraseman et al. 2021 [41]/Iran | 31/31 Attrition rate 3.3% | 46.0 ± 2.0/49.4 ± 1.9 | 30(50%) | Components

Intervention providers: RN with MS Delivery mode: face to face/group Dose: 90/ session, twice a week, for four weeks Setting: dialysis centers Control: usual care |

Pre-post-1m Coping strategy use (CSS) Self-efficacy (GSES) | Patients in the intervention group got more improvements in coping strategy use (effect size = 1.70, t = 6.27, p < 0.001) and self-efficacy (effect size = 2.48, t = 11.9, p < 0.001) compared with patients in the control group. |

| Chan et al. 2022 [42]/China | 40/41 Attrition rate 6.2% | 68.4 ± 8.7/65.0 ± 11.0 | 42 (58.3%) | Components

Theory/Model: theory of hope Intervention providers: renal nurse specialists Delivery mode: face-to-face, telephone or video call/individual Dose: two 60-minute sessions and two 30-minute sessions, once a week, for 4 weeks Setting: the nephrology unit Control: routine care |

Pre-post-4w Quality of life (KDQOL-36) | Patients in the intervention group got more improvements in the effects of kidney disease (Wald χ2 = 8.324, p = 0.004) and mental component summary (Wald χ2 = 6.763, p = 0.009). |

| Chen et al. 2021 [18]/ Singapore | 77/77 | 59.7 ± 12.4 /62.0 ± 13.7 | 72(58.1%) | Components

Theory/Model: Bandura’s self-efficacy theory Intervention providers: RN with PhD Delivery mode: face-to-face/individual Dose: 90 min/session, twice a week, for one week Setting: dialysis centers Control: routine care |

Pre-1m-3m-6m Self-care self-efficacy (DSSS) Anxiety and depression (HADS) Treatment adherence (RAAQ and RABQ) HRQoL (KDQoL™-36) |

Patients in the intervention group got more improvements in anxiety (effect size = -o.41, F = 3.001, p = 0.040) and depression (effect size = −0.42, F = 5.170, p = 0.003) compared with patients in the control group. No significant effects were found in other outcomes. |

| Cukor et al. 2014 [43]/America | 38/27 BDI ≥ 10 Attrition rate 9.2% | NI | 18 (27.3%) | Components

Theory/Model: none Intervention providers: a doctoral-level psychologist and two doctoral-level trainees under the supervision Delivery mode: face-to-face/individual Dose: 60 min/session, once a week, for three months Setting: dialysis centers Control: usual care |

Pre-post-3m Depression (BDI-II and HAM-D) Quality of life (KDQOL) | Patients in the intervention group got more improvements in depression (effect size = −0.17, t = 1.29, p < 0.05) and quality of life (effect size = 0.16, t = 0.21, p = 0.04) compared with patients in the control group. |

| Durmuş et al. 2021 [44]/ Turkey | 43/43 Attrition rate 17.4% | 56.1 ± 12.7 | 43(60.1%) | Components

Intervention providers: NI Delivery mode: face-to-face/individual Dose: 20–30min/session, twice a week, for eight weeks Setting: dialysis centers Control: standard treatment |

Pre-post Anxiety and depression (HADS) | Patients in the intervention group got more improvements in anxiety (effect size = −0.94, t = 6.70, p = 0.000) and depression (effect size = −0.80, t = 4.88, p = 0.001) compared with patients in the control group. |

| Erdley et al. 2014 [38]/America | 17/18 Attrition rate 5.7% | 72.3 ± 5.6 73.5 ± 8.3 | 21(65.6%) | Components

Theory/Model: none Intervention providers: nephrologist Delivery mode: face-to-face/group Dose: 60 min/session, once a week, for six weeks Setting: hospital Control: routine care |

Pre-post Depression (BDI and PHQ-9) | Patients in the intervention group got more improvements in depression (effect size = −0.97, t = 2.15, p < 0.05) compared with patients in the control group. |

| Espahbodi et al. 2015 [36]/ Iran | 30/30 | 49.1 ± 14.552.3 ± 15.6 | 27(45%) | Components

Theory/Model: none Intervention providers: a nephrologist and a psychiatrist Delivery mode: face-to-face/group Dose: 60 min/session, once every other day, for one week Setting: dialysis centers Control: routine care |

Pre-1m Anxiety and depression (HADS) |

No significant effects were found in depression and anxiety. |

| He, 2008 [37]/China | 16/16 | 49.5 ± 15.3 | 19(59.4%) | Components

Theory/Model: Ellis ABC theory Intervention providers: RN with MS Delivery mode: face-to-face/group Dose: 90 min/session, once a week, for twelve weeks Setting: dialysis centers Control: routine care |

Pre-post Stress (HSS) Depression (SDS) Anxiety (SAS) Mental health (SCL-90) Quality of life (SF-36) |

Patients in the intervention group got more improvements in stress (effect size = −0.88, t = −3.19, p = 0.003), depression (effect size = −0.24, t = −0.21, p = 0.045), anxiety (effect size = −0.82, t = −2.95, p = 0.006), mental health (effect size = −1.92, t = −3.11, p = 0.003), physiological health of QOL (effect = 1.09, t = 3.76, p = 0.001), and mental health of QOL (effect size = 0.54, t = 2.90, p = 0.007) compared with patients in the control group. |

| Hou et al. 2014 [45]/China | 52/51 | 54.5 ± 13.8 52.4 ± 14.5 | 42(40.8%) | Components

Theory/Model: none Intervention providers: physician Delivery mode: face-to-face/individual Dose: muscle relaxation:30min/session, once two days, after the patients were well trained:60min/session, three times a week, for three months Setting: dialysis centers Control: routine care |

Pre-post Anxiety and depression (SCL-90) Sleep quality (PSQI) |

Patients in the intervention group got more improvements in anxiety (effect size = −1.94, t = 9.46, p = 0.000), depression (effect size = −0.61, t = −4.08, p = 0.000), and sleep quality (effect size = −1.52, t = 8.41, p = 0.000) compared with patients in the control group. |

| Jenkins et al. 2021 [46]/Australia | 42/42 Attrition rate 48.8% | 60.8 ± 10.2 59.8 ± 13.2 | 30 (52.6%) | Components

Theory/Model: self-determination theory Intervention providers: a health professional (e.g., nurse, psychologist) Delivery mode: face-to-face, telephone or video call/individual Dose: 60 min/session, once a week, for eight weeks; plus, a booster session 3 months after session eight Setting: the nephrology unit Control: routine care |

Pre-post-3m-9m Depression and anxiety (HADS) Quality of Life (KDQOL-SF) Self-efficacy (GSE) |

Patients in the intervention group got more improvements in depression (effect size = −1.16, η2 = 0.012, p = 0.012); No significant effects were found in other outcomes. |

| Lerma et al. 2017 [47]/ Mexico | 38/22 | 41.8 ± 14.7 41.7 ± 15.1 |

23(38.3%) | Components

Theory/Model: none Intervention providers: therapist Delivery mode: face-to-face/group Dose: 120 min/session, 5 times a week, for 5 weeks Setting: dialysis centers Control: routine care |

Pre-post-1m Anxiety and depression (BAI and BDI) QOL (Quality of Life Scale scores) |

Patients in the intervention group got more improvements in anxiety (effect size = −0.64, t = 2.80, p < 0.01), depression (effect size = −0.62, t = 3.13, p < 0.01) and quality of life (effect size = 0.64, t = 3.07, p < 0.01) compared with patients in the control group. |

| Saraireh et al. 2018 [40]/Jordan | 65/65 | 52.0 ± 10.7 53.4 ± 8.0 |

55(50%) | Components

Theory/Model: none Intervention providers: RN with PhD Delivery mode: face-to-face/individual Dose: 60 min/session, 7 times, duration and frequency (NI) Setting: dialysis centers Control: CBT |

Pre-post Depression (HADS) |

Patients in the intervention group got more improvements in depression (effect size = −0.74, t = 4.68, p = 0.00) compared with patients in the CBT group. |

| Shareh et al. 2022 [48]/Iran | 58/58 | 43.7 ± 6.4 46.4 ± 7.9 |

68(58.6%) | Components

Theory/Model: none Intervention providers: general practitioner, psychologist and psychotherapist Delivery mode: face-to-face/group (7-9) Dose: 90 min/session, once a week, for nine weeks Setting: dialysis centers Control: received psychoeducation consultation in a group format |

pre-post Sleep Quality (PSQI) Anxiety and depression (BAI and BDI) |

Patients in the intervention group got more improvements in sleep quality (effect size = −0.31, F = 414.98, p = 0.000,#x003B7;2 = 0.79), anxiety (effect size = −0.68, F = 235.70, p = 0.000, η2 = 0.682), depression (effect size = −0.85, F = 176.63, p = 0.000, η2 = 0.616) compared with patients in the control group. |

| Tsay et al. 2005 [39]/China | 33/33 Attrition rate 13.6% |

50.7 ± 14.1 | 27 (46.6%) | Components

Intervention providers: a clinical nurse specialist in nephrology and a clinical psychotherapist Delivery mode: face-to-face/individual + group (11) Dose: 120 min/session, once a week, for eight weeks Setting: center hemodialysis unit Control: routine care |

Pre-3m Perceived stress (HSS) Depression (BDI) uality of life (MOS SF-36) |

Patients in the intervention group got more improvements in depression levels (effect size = −0.68, t = 2.88, p < 0.01) compared with patients in the control group. No significant effects were found in other outcomes. |

3.5.2. Conceptual framework

Several studies have used a guiding conceptual framework (e.g., a study [42] used the theory of hope to guide intervention strategies to motivate people to pursue goals with a positive attitude, thereby enhancing life meaning and personal strength. One study [18] used Bandura’s self-efficacy theory to improve patients’ self-efficacy, well-being, and adherence to improve patients’ quality of life. Else, two studies used Ellis ABC theory [37] and self-determination theory [47], but did not fully explain the guiding role of the theory), the outcomes-based learning model Lazarus and Folkman’s [50] theory of stress and coping, and Beck’s [51] cognitive-behavioral therapy were mentioned as the theoretical basis for Psychoeducational interventions.

3.5.3. Dose, format and intervener

All interventions were carried out in hospitals or dialysis centers. Regarding intervention delivery forms, group [36–38, 41, 45, 48], individual [18, 40, 42–44, 46, 47], and combined group and individual [39] interventions were used in included studies. A large variety of methods were used to conduct interventions, including lectures, group discussions, questions and answers, and/or role-playing. Four studies [18, 38, 46, 48] reported providing educational booklets to patients as part of the intervention.

Across all studies, the number of psychoeducational courses varied according to the characteristics of the intervention, ranging from 2 to 10 sessions, each lasting 30 to 120 min, and the entire intervention period ranging from 1 to 12 weeks. The follow-up period was 1 ∼ 9 months.

Seven studies [18, 37, 39–42, 47] reported the inclusion of nurses as providers of the interventions. Six studies [36, 39, 43, 45, 47, 48] reported on specialists in psychology, and four [45] reported on nephrologists acting as providers or participating in the implementation of the intervention. Specific details on the characteristics of interventions are presented in Supplementary Table 4.

3.6. Outcomes measure characteristics

Twelve studies [18, 36–40, 43–48] measured depressive status in patients with MHD, of which five studies [18, 36, 40, 46, 47] used the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), three studies [39, 45, 48] used the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), two studies [38, 43] combined BDI and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) or Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) to measure depression, one study [37] used the Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS), and one study [44] used Symptom Checklist 90 (SCL-90). Eight studies [18, 36] measured anxiety status in patients, four studies [18, 36, 46, 47] used HADS, two studies [45, 48] used the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and the remaining two studies used the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) [37]and SCL-90 [44], respectively. Seven studies [18, 37, 39, 42, 43, 47, 48] measured quality of life in patients, four studies [18, 42, 43, 47] used the Kidney Disease Quality of Life Scale (KDQOL), two studies [37, 39] used The Medical Outcome Study 36–item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36), one studies [48] used the questionnaire of profile of quality of life in chronically ill patients (PECVEC). Specific details on the characteristics of outcomes are presented in Table 3.

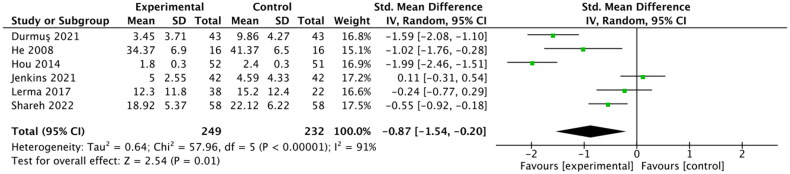

3.5. Effect of psychoeducational interventions on anxiety of patients with MHD

The meta-analysis (Figure 2) of six studies [37, 44–48] indicates the short-term effects of Psychoeducational interventions on anxiety in patients with MHD after the intervention compared to controls (SMD: −0.87, 95% CI: −1.54 to −0.20, p = 0.01, I2 = 91%; 481 participants). Five of six studies used psychotherapy techniques of emotion regulation. The sensitivity analysis was carried out by removing studies one by one, and the heterogeneity was not significantly reduced. This is due to the difference in baseline anxiety levels between the intervention group and the control group in this study [47], with the intervention group having significantly higher anxiety scores than the control group, leading to higher heterogeneity. The pooled effect size showed that psychoeducational interventions can effectively reduce the anxiety level in MHD patients in the short term (<1 m).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the meta-analysis of the effects of Psychoeducational interventions on anxiety in MHD patients one month after intervention.

The meta-analysis (Figure 3A) of four studies [18, 36, 47, 48] indicates the medium-term effects of Psychoeducational interventions on anxiety in patients with MHD after the intervention compared to controls (SMD: −0.29, 95% CI: −0.50 to −0.08, p = 0.006, I2 = 49%; 358 participants). Three study interventions used problem-solving techniques and performed subgroup analysis. The results showed that the psychoeducational intervention with problem-solving techniques can effectively reduce the anxiety level in MHD patients in the medium term (1–3 m) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

A Forest plot of the meta-analysis of the effects of Psychoeducational interventions on anxiety in MHD patients one to three months after intervention. Figure 3B Forest plot of the subgroup analysis of the effects of Psychoeducational interventions with psychological techniques of problem-solving.

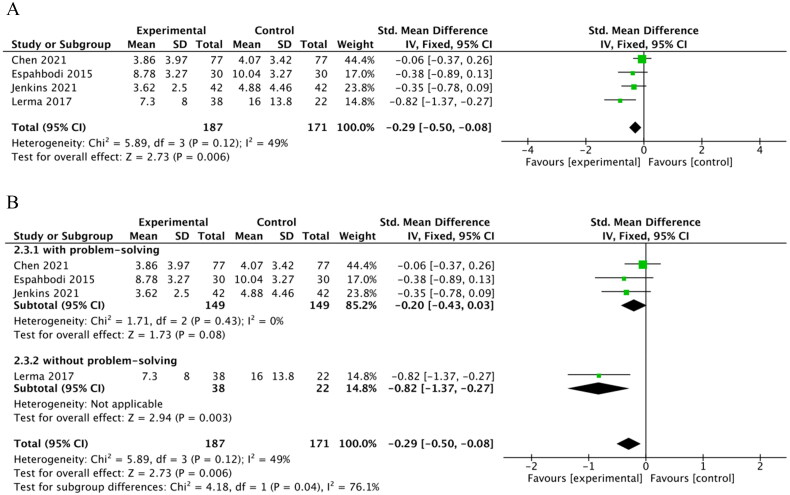

3.6. Effects of psychoeducational interventions on depression of patients with MHD

The meta-analysis (Figure 4) of nine studies [37, 38, 40, 43–48] indicates the short-term effects of psychoeducational interventions on depression in patients with MHD after the intervention compared to controls (SMD: −0.65, 95% CI: −0.91 to −0.38, p < 0.01, I2 = 65%; 711 participants). Sensitivity analysis was performed and suggested that one study [47] should be excluded, and its heterogeneity was changed to low (X2 = 5.30, I2 = 0%, p = 0.62). This is because baseline depression scores in the intervention group in this study [47] were significantly higher than those in the control group, which resulted in a higher heterogeneity. The pooled effect size showed that psychoeducational interventions can effectively reduce the depression level in MHD patients in the short term (< 1 m).

Figure 4.

Forest plot of the meta-analysis of the effects of Psychoeducational interventions on depression in MHD patients one month after intervention.

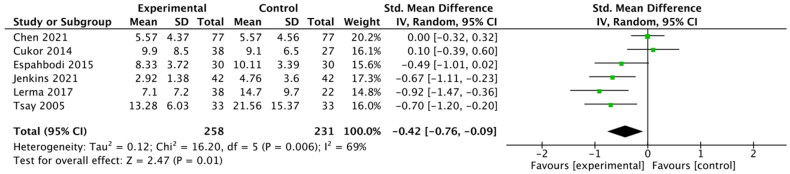

The meta-analysis (Figure 5) of six studies [18, 36, 39, 43, 47, 48] indicates the medium-term effects of psychoeducational interventions on depression in patients with MHD after the intervention compared to controls (SMD: −0.42, 95% CI: −0.76 to −0.09, p = 0.01, I2 = 69%; 489 participants). Sensitivity analysis was performed and suggested that two studies [18, 43] should be excluded, and its heterogeneity was changed to low (X2 = 1.21, I2 = 0%, p = 0.75). This is because the baseline of the control group was lower than that of the intervention group. In addition, after the intervention in the intervention group, the control group also received the same intervention, and the depression score decreased rapidly, which also indicates that the intervention is effective. The pooled effect size showed that the psychoeducational interventions can effectively reduce the depression level in MHD patients in the medium term (1-3 m).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of the meta-analysis of the effects of Psychoeducational interventions on depression in MHD patients one to three months after intervention.

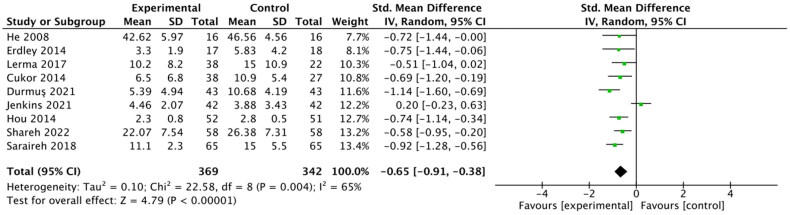

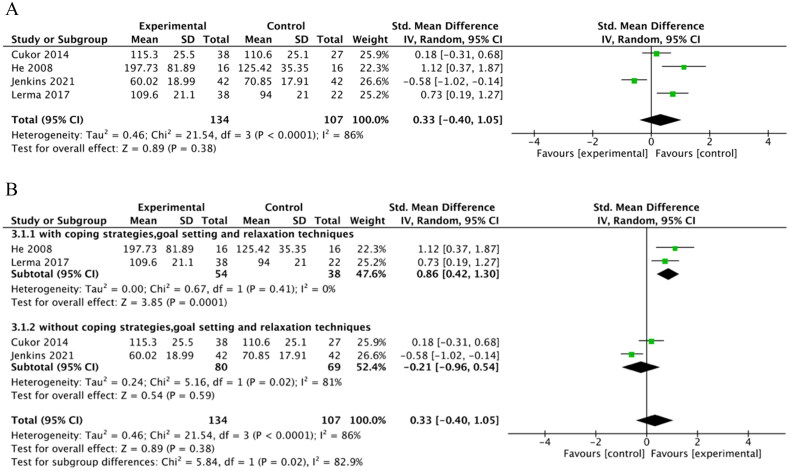

3.7. Effect of psychoeducational interventions on quality of life of patients with MHD

The meta-analysis (Figure 6A) of four studies [37, 47, 48] displays the short-term effects of Psychoeducational interventions on QOL in patients with MHD after the intervention compared to controls (SMD: 0.33, 95% CI: −0.40 to 1.05, p = 0.38, I2 = 86%; 241 participants). The results were not statistically significant (Figure 6A). But, three of four studies used psychotherapy techniques for social support. When they were divided into two subgroups according to the intervention characteristics of psychological techniques such as coping strategies, goal setting and relaxation techniques, the results were statistically significant. The effect size of used psychological techniques that coping strategies, goal setting and relaxation techniques was (SMD: 0.86, 95% CI: 0.42 to 1.30, p = 0.0001, I2 = 0%; 92 participants). Another was (SMD: −0.21, 95% CI: −0.96 to 0.54, p = 0.59, I2 = 81%; 149 participants), which showed that the psychoeducational interventions that include different characteristics could enhance the QOL in MHD patients in the short term (< 1 m) (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

A Forest plot of the meta-analysis of the effects of Psychoeducational interventions on QOL in MHD patients one months after intervention. Figure 6B Forest plot of the subgroup analysis of the effects of Psychoeducational interventions with psychological techniques of coping strategies, goal setting and relaxation techniques.

4. Discussion

Recent reports [10–12] indicate that individuals with MHD may experience anxiety, depression, and other psychological distress, which can negatively affect up to 50% of these individuals and impact their overall quality of life [52, 53]. It’s important for healthcare professionals to address these issues and provide necessary support and treatment to improve the mental well-being of MHD patients. Therefore, the aim of this review was to identify the best evidence on the effectiveness of currently available psychoeducational interventions for health-related quality of life in patients with MHD.

This review identified 14 RCT studies with a total of 1134 participants to examine the characteristics of psychoeducational interventions and their effectiveness on anxiety, depression, and quality of life levels among patients with MHD in-center hemodialysis. The results indicates psychoeducational interventions for depression and anxiety have a positive impact on the disease and treatment. The results suggested that psychoeducational interventions could ameliorate the negative effects of the patient role by reducing anxiety and depression and improving quality of life when compared with the controls.

The interventions in the 14 studies included in this review all included educational content and psychotherapy techniques. Most programs involving an educational component addressed informational needs commonly reported by hemodialysis patients, such as diet and medication management and knowledge regarding ESRD. These educational contents also conform to the educational norms of kidney disease in patients with advanced CKD [54].

In terms of psychotherapy techniques, the result of the meta-analysis showed that psychoeducational intervention can significantly reduce the level of anxiety and depression in MHD patients in the short and medium term (p < 0.05), especially the psychoeducational intervention using emotion regulation and problem-solving psychotherapy techniques (Figure 4, 5). In addition, the psychotherapy technique of emotion regulation was widely used in the studies we included. The reason may be that these two psychotherapy techniques can help patients mobilize positive emotions, deal with practical problems, and encourage them to obtain social support to relieve anxiety [55]. Although we did not find long-term effects of Psychoeducational interventions on anxiety and depression levels in this review, it has been demonstrated in other populations that problem-solving techniques can effectively reduce anxiety symptoms in the short-term, medium, and long term [56, 57].

Our findings, showing no effect of psychoeducational intervention on patients’ quality of life, are inconsistent with other studies [18] showing that psychoeducational intervention has a significant effect on MHD patients’ quality of life, which may be because our classification of follow-up time in the meta-analysis was too narrow, resulting in fewer study analyses. Fortunately, subgroup analysis found that interventions with coping strategies (e.g., goal setting, relaxation techniques) can promote the improvement of the patient’s quality of life (p < 0.05) (Figure 6), and three of four studies also used psychotherapy techniques of social support. There are many coping strategies used by hemodialysis patients, and the results of this study suggest that coping strategies based on goal setting and relaxation techniques have a good impact on patient’s quality of life. Consistent with the findings of this study, interventions using emotion regulation coping strategies have been found to improve patient’s quality of life and mood [52]. However, it is not possible to compare the effects of each type of technique on patients because the psychotherapy techniques used vary widely. But there is no denying that psychotherapeutic techniques have a significant impact on the quality of life of patients [58, 59].

According to the results, psychoeducational interventions can be used as a nursing procedure in blood purification centers and form a psychoeducational interventions booklet to provide a way for hemodialysis patients to learn ESRD-related knowledge and manage psychological distress such as anxiety and depression.

Limitations and future directions

It is undeniable that there are some limitations in this systematic review. The included studies had higher heterogeneity due to varying sample sizes, intervention methods, program duration, and non-uniform measures of outcome indicators. In addition, this review did not focus on studies of dyadic interventions with caregivers and patients due to a lack of studies on the impact of dyadic interventions with patients and caregivers on patient health outcomes. This is also a focus of future research.

Conclusion

The findings of the systematic review suggested that psychoeducational interventions using emotional regulation, problem-solving, coping strategies and social support can be used in clinical practice to prevent or reduce anxiety and depression and improve the quality of life in MHD patients. However, due to the small number of included studies and high heterogeneity, there are certain limitations. In the future, we will focus on the impact of family interventions or dyadic interventions on the health outcomes of MHD patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Thanks to all the authors for their efforts in completing this systematic review.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Taizhou Science and Technology Project of Jiangsu Province, China, under Grant number TS202311.

Authors’ contributions

LY.Z. took part in the study design, literature research, assessments of research, data analysis and manuscript preparation. LZ took part in the study design, literature research, and research assessments. LJ.Z. was the guarantor of the integrity of the entire study and led the study design. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The authors are willing to permanently share data supporting the results and analysis presented in the paper after publication. The data can be used for scientific research beneficial to human health. The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Global Burden of Disease (GBD) . Global Health Date Exchange[EB/OL]. https://ghdx.healthdata.org/.

- 2.Li K, Zhao J, Yang W, et al. Sleep traits and risk of end-stage renal disease: a mendelian randomization study. BMC Med Genomics. 2023;16(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12920-023-01497-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans M, Lewis RD, Morgan AR, et al. A narrative review of chronic kidney disease in clinical practice: current challenges and future perspectives. Adv Ther. 2022;39(1):33–17. doi: 10.1007/s12325-021-01927-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miyata Y, Obata Y, Mochizuki Y, et al. Periodontal disease in patients receiving dialysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(15):3805 doi: 10.3390/ijms20153805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jing C, Jing X, Yanqing J, et al. Expert consensus on clinical practice of injection safety in hemodialysis. Chi J Nursing. 2022;57(07):785–790. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thiery A, Séverac F, Hannedouche T, et al. Survival advantage of planned haemodialysis over peritoneal dialysis: a cohort study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2018;33(8):1411–1419. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfy007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thurlow JS, Joshi M, Yan G, et al. Global epidemiology of end-stage kidney disease and disparities in kidney replacement therapy. Am J Nephrol. 2021;52(2):98–107. doi: 10.1159/000514550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carswell C, Reid J, Walsh I, et al. Complex arts-based interventions for patients receiving haemodialysis: a realist review. Arts Health. 2021;13(2):107–133. doi: 10.1080/17533015.2020.1744173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bártolo A, Sousa H, Ribeiro O, et al. Effectiveness of psychosocial interventions on the burden and quality of life of informal caregivers of hemodialysis patients: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(26):8176–8187. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2021.2013961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan Z, Jia-Le N, Hua Q, et al. Prevalence and correlates of depression among maintenance hemodialysis patients in Huhhot region, China: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Nephrol. 2022;22(07):574–583. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al Naamani Z, Gormley K, Noble H, et al. Fatigue, anxiety, depression and sleep quality in patients undergoing haemodialysis. BMC Nephrol. 2021;22(1):157. doi: 10.1186/s12882-021-02349-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ravaghi H, Behzadifar M, Behzadifar M, et al. Prevalence of depression in hemodialysis patients in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2017;11(2):90–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fletcher BR, Damery S, Aiyegbusi OL, et al. Symptom burden and health-related quality of life in chronic kidney disease: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Med. 2022;19(4):e1003954. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim S, Nigatu Y, Araya T, et al. Health related quality of life (HRQOL) of patients with end stage kidney disease (ESKD) on hemodialysis in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol. 2021;22(1):280. doi: 10.1186/s12882-021-02494-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen SD, Cukor D, Kimmel PL.. Anxiety in patients treated with hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(12):2250–2255. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02590316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Nashri F, Almutary H.. Impact of anxiety and depression on the quality of life of haemodialysis patients. J Clin Nurs. 2022;31(1–2):220–230. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15900.[InsertedFromOnline [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shirazian S, Grant CD, Aina O, et al. Depression in chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease: similarities and differences in diagnosis, epidemiology, and management. Kidney Int Rep. 2017;2(1):94–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2016.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen HC, Zhu L, Chan WCS, et al. The effectiveness of a psychoeducational intervention on health outcomes of patients undergoing haemodialysis: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Pract. 2022;29(3):e13123. doi: 10.1111/ijn.13123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang XX, Lin ZH, Wang Y, et al. Motivators for and barriers to exercise rehabilitation in hemodialysis centers: a multicenter cross-sectional survey. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;99(5):424–429. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang C, Mu H, Yang YF, et al. Effect of aromatherapy on quality of life in maintenance hemodialysis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ren Fail. 2023;45(1):2164202. doi: 10.1080/0886022X.2022.2164202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu XL, Ji B, Yao SD, et al. Effect of music intervention during hemodialysis: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021;25(10):3822–3834. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202105_25950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ng CZ, Tang SC, Chan M, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive behavioral therapy for hemodialysis patients with depression. J Psychosom Res. 2019;126:109834. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2019.109834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Natale P, Palmer SC, Ruospo M, et al. Psychosocial interventions for preventing and treating depression in dialysis patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;12(12):CD004542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu H, Liu X, Chau PH, et al. Effects of intradialytic exercise on health-related quality of life in patients undergoing maintenance haemodialysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Qual Life Res. 2022;31(7):1915–1932. doi: 10.1007/s11136-021-03025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barello S, Anderson G, Acampora M, et al. The effect of psychosocial interventions on depression, anxiety, and quality of life in hemodialysis patients: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Int Urol Nephrol. 2023;55(4):897–912. doi: 10.1007/s11255-022-03374-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rabelo JL, Cruz BF, Ferreira JDR, et al. Psychoeducation in bipolar disorder: a systematic review. World J Psychiatry. 2021;11(12):1407–1424. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v11.i12.1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xia J, Merinder LB, Belgamwar MR.. Psychoeducation for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;2011(6):CD002831. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002831.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma’rifah AR, Afiyanti Y, Huda MH, et al. Effectiveness of psychoeducation intervention among women with gynecological cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(10):8271–8285. doi: 10.1007/s00520-022-07277-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Powell LA, Parker J, Weighall A, et al. Psychoeducation intervention effectiveness to improve social skills in young people with ADHD: a meta-analysis. J Atten Disord. 2022;26(3):340–357. doi: 10.1177/1087054721997553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mou H, Wong MS, Chien WTP.. Effectiveness of dyadic psychoeducational intervention for stroke survivors and family caregivers on functional and psychosocial health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021;120:103969. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.103969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Page MJ, Mckenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372n:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brodaty H, Donkin M.. Family caregivers of people with dementia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2009;11(2):217–228. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.2/hbrodaty. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aromataris E, Munn Z.. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. JBI. 2020; Available from https://synthesismanual.jbi.global. doi: 10.46658/JBIMES-20-01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Al-Ghafri BR, Al-Mahrezi A, Chan MF.. Effectiveness of life review on depression among elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pan Afr Med J. 2021;40:168. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2021.40.168.30040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Espahbodi F, Hosseini H, Mirzade MM, et al. Effect of psycho education on depression and anxiety symptoms in patients on hemodialysis. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2015;9(1):e227. doi: 10.17795/ijpbs227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.He JA. Study on the effect of group cognitive therapy of quality of life in MHD patients. China: Third Military Medical University; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Erdley SD, Gellis ZD, Bogner HA, et al. Problem-solving therapy to improve depression scores among older hemodialysis patients: a pilot randomized trial. Clin Nephrol. 2014;82(1):26–33. doi: 10.5414/CN108196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsay SL, Lee YC, Lee YC.. Effects of an adaptation training programme for patients with end-stage renal disease. J Adv Nurs. 2005;50(1):39–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Al Saraireh FA, Aloush SM, Al Azzam M, et al. The effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy versus psychoeducation in the management of depression among patients undergoing haemodialysis. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2018;39(6):514–518. doi: 10.1080/01612840.2017.1406022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ghasemi Bahraseman Z, Mangolian Shahrbabaki P, Nouhi E.. The impact of stress management training on stress-related coping strategies and self-efficacy in hemodialysis patients: a randomized controlled clinical trial. BMC Psychol. 2021;9(1):177–177. doi: 10.1186/s40359-021-00678-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chan K, Wong FKY, Tam SL, et al. Effectiveness of a brief hope intervention for chronic kidney disease patients on the decisional conflict and quality of life: a pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Nephrol. 2022;23(1):209. doi: 10.1186/s12882-022-02830-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cukor D, Halen NV, Asher DR, et al. Psychosocial intervention improves depression, quality of life, and fluid adherence in hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(1):196–206. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012111134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hou Y, Hu P, Liang Y, et al. Effects of cognitive behavioral therapy on insomnia of maintenance hemodialysis patients. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2014;69(3):531–537. doi: 10.1007/s12013-014-9828-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shareh H, Hasheminik M, Jamalinik M.. Cognitive behavioural group therapy for insomnia (CBGT-I) in patients undergoing haemodialysis: a randomized clinical trial. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2022;50(6):559–574. doi: 10.1017/S1352465822000364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Durmuş M, Ekinci M.. The effect of spiritual care on anxiety and depression level in patients receiving hemodialysis treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Relig Health. 2022;61(3):2041–2055. doi: 10.1007/s10943-021-01386-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jenkins ZM, Tan EJ, O’flaherty E, et al. A psychosocial intervention for individuals with advanced chronic kidney disease: a feasibility randomized controlled trial. Nephrology. 2021;26(5):442–453. doi: 10.1111/nep.13850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lerma A, Perez-Grovas H, Bermudez L, et al. Brief cognitive behavioural intervention for depression and anxiety symptoms improves quality of life in chronic haemodialysis patients. Psychol Psychother. 2017;90(1):105–123. doi: 10.1111/papt.12098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang JX, Kurian AW, Jo B, et al. Emotion regulation and choice of bilateral mastectomy for the treatment of unilateral breast cancer. Cancer Med. 2023;12(11):12837–12846. doi: 10.1002/cam4.5963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Gruen RJ, et al. Appraisal, coping, health status, and psychological symptoms. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;50(3):571–579. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.50.3.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Beck AT. Cognitive therapy: past, present, and future. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61(2):194–198. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.61.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Işık Ulusoy S, Kal Ö.. Relationship among coping strategies, quality of life, and anxiety and depressive disorders in hemodialysis patients. Ther Apher Dial. 2020;24(2):189–196. doi: 10.1111/1744-9987.12914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shdaifat EA. Quality of life, depression, and anxiety in patients undergoing renal replacement therapies in Saudi Arabia. ScientificWorldJournal. 2022;2022:7756586. doi: 10.1155/2022/7756586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shukla AM, Cavanaugh KL, Jia H, et al. Needs and considerations for standardization of kidney disease education in patients with advanced CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2023;18(9):1234–1243. doi: 10.2215/CJN.0000000000000170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gillanders S, Wild M, Deighan C, et al. Emotion regulation, affect, psychosocial functioning, and well-being in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;51(4):651–662. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kannampallil T, Ajilore OA, Lv N, et al. Effects of a virtual voice-based coach delivering problem-solving treatment on emotional distress and brain function: a pilot RCT in depression and anxiety. Transl Psychiatry. 2023;13(1):166. doi: 10.1038/s41398-023-02462-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dong Z, Chiu MM, Zhou S, et al. Problem solving and emotion coping styles for social anxiety: a meta-analysis of Chinese Mainland Students. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2023.. doi: 10.1007/s10578-023-01561-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.González-Flores CJ, Garcia-Garcia G, Lerma C, et al. Effect of cognitive behavioral intervention combined with the resilience model to decrease depression and anxiety symptoms and increase the quality of life in ESRD patients treated with hemodialysis[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(11):20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Abu Maloh HIA, Soh KL, Chong SC, et al. The effectiveness of Benson’s relaxation technique on pain and perceived stress among patients undergoing hemodialysis: a double-blind, cluster-randomized, active control clinical trial. Clin Nurs Res. 2023;32(2):288–297. doi: 10.1177/10547738221112759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors are willing to permanently share data supporting the results and analysis presented in the paper after publication. The data can be used for scientific research beneficial to human health. The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.