Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Previous investigations have shown that local application of nanoparticles presenting the carbohydrate moiety galactose-α-1,3-galactose (α-gal epitopes) enhance wound healing by activating the complement system and recruiting pro-healing macrophages to the injury site. Our companion in vitro paper suggest α-gal epitopes can similarly recruit and polarize human microglia toward a pro-healing phenotype. In this continuation study, we investigate the in vivo implications of α-gal nanoparticle administration directly to the injured spinal cord.

METHODS:

α-Gal knock-out (KO) mice subjected to spinal cord crush were injected either with saline (control) or with α-gal nanoparticles immediately following injury. Animals were assessed longitudinally with neurobehavioral and histological endpoints.

RESULTS:

Mice injected with α-gal nanoparticles showed increased recruitment of anti-inflammatory macrophages to the injection site in conjunction with increased production of anti-inflammatory markers and a reduction in apoptosis. Further, the treated group showed increased axonal infiltration into the lesion, a reduction in reactive astrocyte populations and increased angiogenesis. These results translated into improved sensorimotor metrics versus the control group.

CONCLUSIONS:

Application of α-gal nanoparticles after spinal cord injury (SCI) induces a pro-healing inflammatory response resulting in neuroprotection, improved axonal ingrowth into the lesion and enhanced sensorimotor recovery. The data shows α-gal nanoparticles may be a promising avenue for further study in CNS trauma.

Graphical abstract

Putative mechanism of therapeutic action by α-gal nanoparticles. A. Nanoparticles injected into the injured cord bind to anti-Gal antibodies leaked from ruptured capillaries. The binding of anti-Gal to α-gal epitopes on the α-gal nanoparticles activates the complement system to release complement cleavage chemotactic peptides such as C5a, C3a that recruit macrophages and microglia. These recruited cells bind to the anti-Gal coated α-gal nanoparticles and are further polarized into the M2 state. B. Recruited M2 macrophages and microglia secrete neuroprotective and pro-healing factors to promote tissue repair, neovascularization and axonal regeneration (C.).

Keywords: Spinal cord injury, α-gal nanoparticles, Microglia, Anti-inflammatory, Neuroprotection

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI)1 is a multi-faceted pathology that consists of the primary damage (i.e. mechanical) and also secondary injury, which is generally of biochemical or cellular origin [1]. Post-trauma, immune cells such as macrophages play a significant role in the secondary injury cascade. Monocytes circulating in the blood migrate and differentiate into macrophages and intermingle with the resident microglia within the cord [2, 3]. These microglia normally act as sentinels but in response to foreign (pathogen) or endogenous (tissue injury) stimuli, mobilize to the source. Both microglia/macrophages broadly exist as either pro-inflammatory (M1) or anti-inflammatory (M2). M1 macrophages identified as Ly6chiCX3CR1lo [4] facilitate phagocytosis and secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines (Interleukin-6 (IL-6), Tumor necrosis factor- α (TNF-α)) for cell debris clearance, but their persistence can also lead to cell death and axonal dieback through increased ROS generation [5]. In contrast, M2 macrophages identified as Ly6cloCX3CR1hi [4] produce growth factors such as TGF-β and IL‐10 and are implicated in tissue remodeling, spinal repair [6], and neuronal sprouting [7]. The improper transition from the M1 to M2 macrophage phenotype post-SCI leads to tissue scarring, and insufficient healing and is a barrier to axonal regeneration [8–10].

The duality in macrophage functionality has led to investigations on the effect of shifting macrophage populations after SCI. For example, the delivery of anti-inflammatory IL-10 via microparticles at the injury site modulates inflammation by altering macrophage phenotype and improves functional recovery [11]. In another study, direct implantation of M2 macrophages in spinal cord injured rats improves locomotor function [12]. However, depletion of macrophages post-SCI has been shown to improve hind limb motor function [13] while altering the origin of the recruited macrophages can also impact outcomes in either a beneficial or debilitating manner [14]. It is most likely that these disparate results are due to differences in the type of macrophages being targeted (M1 vs. M2) or in the timing of immunomodulation (i.e. therapeutic window).

In this work, we depart from previous studies by exploring the role of innate immunity in SCI, and in particular, promoting the inflammatory response. This approach challenges existing immunotherapy dogma, which often seeks to mitigate inflammation within the cord. A few early studies have hinted that forms of pyrogenic stimuli such as components of bacterial lipopolysaccharide can impart modest improvements in SCI recovery [15–17].

Here, we focus our attention on the use of the α-gal epitope. α-Gal epitope (Galα1-3Galβ1-4GlcNAc-R) is a carbohydrate antigen synthesized by the enzyme α1,3 galactosyltransferase in non-primates and New World monkeys [18]. Humans have lost the ability to produce α-gal and in turn, naturally, produce the anti-Gal antibody (as discussed in the companion paper). The anti-Gal antibody is the most abundant circulating antibody produced by humans. The strong interaction between α-gal epitope on α-gal and the anti-Gal antibody activates the complement system to recruit macrophages (via chemotactic complement cleavage peptides), while the macrophages are further activated via Fcγ-receptor (Fcγ-R) interactions with anti-Gal. Prior data in dermal wounds and cardiac infarction models show that nanoparticles presenting α-gal epitopes can be used to attract pro-healing macrophages to the injection site [19, 20]. Likewise, our in vitro results demonstrate that α-gal nanoparticles can also stimulate, activate and polarize microglia towards a pro-healing phenotype. In this follow-up study, our aim was to investigate the effects of α-gal in mediating the post-SCI immune response and on functional recovery. This was accomplished via direct injection of α-gal into the spinal cord using a transgenic mouse strain in which the α1,3 galactosyltransferase gene GGTA1 was knocked out (GT-KO). These GT-KO mice lack α-gal epitopes and can produce anti-Gal that binds readily to exogenous α-gal epitopes. This model was necessary since wild-type mice normally produce α-gal epitopes. A compression injury modality was used since it represents the most common injury type in human SCI [21–23]. Injured mice were longitudinally monitored and at predetermined time points, the mice were sacrificed and tissue samples evaluated histologically for various pro and anti-inflammatory markers, immune cells and axon growth. Additionally, locomotor and sensory outcomes were evaluated by a battery of behavioral tests. The cumulative results provide a basis for further studies involving immunomodulation with α-gal nanoparticles.

Methods and materials

α-Gal knock-out (GT-KO) mice and pre-operative mice care

The α-gal nanoparticles were prepared as previously described [24, 25]. In brief, chloroform and methanol in 2:1 ratio were mixed with rabbit RBC membranes and incubated overnight with constant stirring, with the resultant mixture filtered and dried in a rotary evaporator. The dried extract was then sonicated in saline to form liposomes and the liposomes centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant containing liposomes was re-sonicated and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min, forming α-gal nanoparticle pellets. Nanoparticles were then resuspended in saline and stored until ready for use.

α1, 3Galactosyltransferase (α1, 3GT) knock-out (GT-KO) mice were used to evaluate the role of α–gal nanoparticles as an immunomodulating agent post-injury. The α1, 3GT-KO strain does not produce the α-gal epitope and but can be stimulated to produce anti-Gal antibodies by exposure to xenogenic cell membranes (pig kidney membranes homogenate) containing α-gal epitope [19, 20, 25–27]. All procedures were done in accordance to approved Purdue University IACUC protocol (# 1110000060). Age, sex, and weight-matched mice were housed as two mice per cage. A total of 104 experimental animals were used in this study.

Immunizations and ELISA

To facilitate the production of the anti-Gal antibody, GT-KO mice were exposed to α-gal epitope through intraperitoneal (IP) immunization of 40 mg of pig kidney membranes homogenate at 5, 6, and 7 weeks after birth. To assess anti-Gal production, serum from these immunized mice was collected at 11 weeks after birth. ELISA analysis using Galα1-3Gal-BSA antigen was performed as discussed previously [19, 20, 25, 27]. Only mice with sufficient anti-Gal production were used for further experiments.

Animal surgery

Anti-Gal producing GT-KO mice were divided into two groups (1) saline treatment and (2) α–gal nanoparticle treatment. All mice were anesthetized with 4% isoflurane and a laminectomy was performed at T9-T10 thoracic segment using a surgical microscope [28]. The spinal cord was then crushed for 15 s using calibrated compression forceps with a thickness of 1.2 mm. Afterwards, the injured mice received either 0.5 μl intraparenchymal injections of sterile saline or 0.5 μl intraparenchymal injections of α–gal nanoparticles (10 mg/ml in saline) using a 34G needle size mounted to a microinjector. After surgery, the wound site was sutured in layers with 6–0 sutures and the mice were allowed to recover before being transferred to the home cage.

Post-operative mice care

The mice post-SCI were administered with buprenorphine (0.05–0.1 mg/kg SC in the morning and the evening) and ketoprofen (5 mg/kg SC in the morning) for the first 3 days. To prevent urinary infections, the bladder was expelled manually three to four times per day for the first 10 days. Additionally, the mice were fed with an enriched diet and oral gavage with Ensure Original Nutrition Powder 3 times per day for 1 week to prevent weight loss. Mice losing more than 20% of their body weight were prematurely sacrificed as a humane endpoint.

Western blot

Several markers were used to characterize secondary injury via Western Blot. These included iNOS, and the apoptosis associated proteins Bcl-2 and Bax. At time points of 24 and 72 h, the injured mice were sacrificed and 0.5 cm of the spinal cord segment was isolated. These time points were chosen to coincide with peak iNOS expression [29, 30]. The isolated spinal cord was then washed with ice-cold PBS and homogenized with cold lysis buffer containing phosphatase and proteinase inhibitors. 30 μg of denatured protein was loaded into SDS-PAGE gel with a molecular weight marker. The membrane was blocked with 5% non-fat milk for 1 h and incubated with respective primary antibodies to iNOS, Bax, Bcl-2, and β-tubulin (housekeeping gene as a loading control) overnight at 4 °C. The membrane was washed with Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 and then incubated with corresponding secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase for 1 h at RT. The membrane was washed again and incubated with a chemiluminescence substrate kit. The bands were visualized by the BioRad Chemi Doc system and quantified densitometrically using ImageJ software. The average of three independent trials was used for statistical analysis.

Histology and immunohistochemical analysis

Post-injured spinal cord isolated at 1, 3, 7, 14, 21, 28, and 45 days were used for histological analysis. In brief, each mouse was sacrificed with 100 mg pentobarbitone sodium and transcardially perfused with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The spinal cord was then isolated and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) overnight at 4 °C. Spinal cords were embedded with paraffin and sectioned longitudinally using a microtome. Slides were processed with H&E staining. For immunohistochemistry (IHC), sections were blocked with 2.5% goat serum for 20 min at RT, followed by antigen retrieval using a pressurized decloaking machine at 95 °C for 20 min with an EDTA retrieval buffer. The slides were incubated with respective primary antibodies for 30 min at RT. F4/80(1:100, Bio-Rad # MCA497G) staining was used to identify the macrophages, Arginase-1 (1:100, Cell Signaling Technology #93668) and CD206 (1:100, Abcam #ab64693) used as anti-inflammatory markers, CD16/32 (1:500, Abcam #ab228971) as pro-inflammatory marker. Additionally, the spinal cord was stained for GFAP astrocyte marker (1:1000, Abcam #ab7260), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (1:25, Thermofisher #MA5-13,182), CD31 (1:20, Abcam #ab28364) as endothelial marker and neurofilament (1:500, Abcam ab8135) for regeneration. The slides were then washed with Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 (rinsed twice at RT) and then incubated with respective secondary antibodies for 30 min at RT. DAPI was used to stain the nuclei. The stained slides were then scanned using Leica Versa8 (Aperio Technologies, Vista, CA) whole-slide scanner at 20 × magnification. The total positive tissue area was quantified for Arginase-1, CD206, CD16/32, and GFAP using Aperio Imagescope v12 software.

Image analysis

The area of interest for each image of Arginase-1, CD206, CD16/32, CD31, neurofilament (NF), GFAP, and VEGF immune-labeled slides was selected and saved. For all markers, area Quantification FL v1 algorithm was loaded and the macros were created by defining maximum and minimum intensity threshold values for each fluorescent color. Next, parameters were defined, and the algorithm was run for the selected images and results recorded. The above steps were repeated for every image. A bar graph for the respective marker was plotted with intensity (measured as average intensity that contains pixel dyes) against day’s post-injury (dpi). To quantify axonal ingrowth into the lesion, the amount of neurofilament staining within the injured site was normalized to neurofilament staining in an uninjured area of the cord. In brief, a box (region of interest, ROI) of 180-pixel width by 150–160 (to accommodate variations in cord width) pixel height was placed over the injury site using Aperio Imagescope v12 software. Positive neurofilament staining (in pixels) above a certain background threshold was tabulated. This value was then normalized to the neurofilament staining in an injured section of cord, using the same ROI size. The average normalized axonal ingrowth against time post-injury was plotted [31–33]. This process was conducted three times for each time point and treatment. 184 slides were used for histological image assessment.

Behavioral evaluations

Mice were evaluated functionally via the open field activity box, tapered balance beam and electric von Frey. Measurements of pre-trained mice were obtained for baseline recordings (before the injury, referred to as 0 dpi) and post-injury days of 3, 7, 14, 21, 28, and 45. Behavioral evaluations were made by blinded technicians.

Open field activity

Locomotor recovery of injured mice were tracked using an open field test [34]. In brief, the mice were allowed to habituate to the testing room for 30 min, and then each mouse was placed on a 30 X 30 cm square test chamber. The locomotor activity was recorded with a digital video camera for 10 min and the distance moved by every mouse was calculated and used for statistical analysis. Videos were corrected for lens distortion and background subtraction with the analysis done in Ethowatcher software to obtain mouse displacement data.

Tapered balance beam

Fine motor coordination and balance were evaluated using a tapered balance beam of width varying from 30 to 6 mm and a fixed length of 100 cm [34]. In brief, animals were trained to travel across an elevated and tapered beam of varying widths to reach an enclosed goal box. Initially, the animals are brought to the experimental behavior room 30 min before they start to habituate. The training was needed for this experiment and every uninjured mouse was trained for three consecutive days with 4 consecutive trials each day and a spacing of 5 min between each trial was given to generate a stable baseline response. The mice were placed to start at a 30 mm edge and finish at a black box placed near a 6 mm edge [35]. The training was stopped until the mouse reached the goal box faster with fewer foot slips. During the test day, the mouse was given 60 s to cross the beam and enter the goal box, with three consecutive trials at 5 min break between trials.

Recording and analysis- Two cameras on either side of the beam were used to capture the mice traversing the beam and the videos saved. The latency to traverse the beam, and the total number of foot slips for each trial were recorded. A mouse that fell or did not cross the beam completely was given a maximum time score of 60 s [36, 37]. A bar graph was plotted with the average time for mice to cross the beam against dpi for every treatment group and beam size. Additionally, a bar graph for foot slips versus dpi was plotted for every beam size and treatment group. VirtualDub was used for video analysis. The video file was opened and the frame was advanced until the balance beam was in view. The markers corresponding to 24 mm, 18 mm, 12 mm, and 6 mm were located. As the mouse began to cross the beam, the beginning frame was defined as when all 4 limbs of the mouse are on the beam, and the handler was no longer touching the mouse. The frame number was noted. Any signs of slipping (foot) were noted as the mouse walked along the beam. The frame numbers when the mouse's hind feet cross the markers (24 mm, 18 mm, 12 mm, and 6 mm) were noted down. The above procedures were repeated until the mouse was removed from the beam.

Electronic von Frey

Use of electric von Frey involved placing a mouse in an elevated small plexiglass enclosure with a wire floor that exposed the plantar surface of the mouse. The mice were then allowed to acclimatize for 30 min in the room before testing began [38]. A single filament with increasing continuous force was applied until a nociceptive behavioral response such as paw withdrawal and paw licking was observed. The experiment was repeated 3 times for each hind paw with a rest of 5 min between every trial. The average of 6 measures for each mouse was calculated and used for analysis. The bar graph was plotted with the average withdrawal response (g) against dpi-injury for each treatment group.

Statistical analysis

For Western blot analysis, two-way ANOVA was used to determine the difference between saline and α-gal nanoparticle treatment. For histological analysis, ANOVA and Tukey post-hoc tests were utilized, and values were represented as means of standard deviation (SD). For functional outcomes, two-way ANOVA for repeated measures using treatment group and time point as factors were used. All statistical analyses were performed using Graph Pad 9.0 software and p < 0.05 was deemed to be significant unless otherwise stated. For non-parametric tests, repeated mixed effect analysis was performed. For multiple comparisons within groups, the Tukey method was used using Graph Pad 9.0.

Results

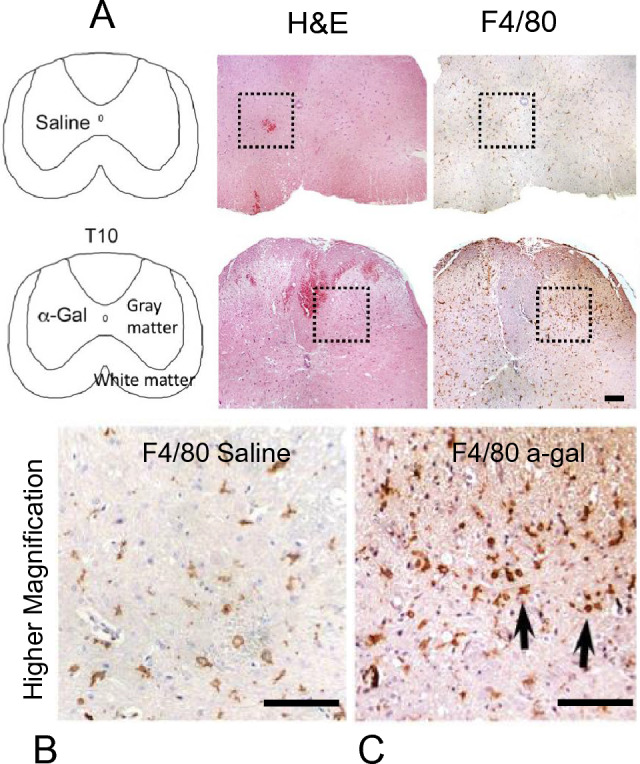

Recruitment of microglia/macrophages upon α-gal injection

In pilot injections, we observed that α-gal nanoparticles robustly recruited macrophages (F4/80+) into the uninjured spinal cord when compared to a saline injection (Fig. 1). In addition to increased cellular recruitment, the migrated macrophages further exhibited a change in morphology. α-Gal stimulated cells exhibited a hypertrophic amoeboid shape, whereas in the saline group, the F4/80+ cells retained a stellate morphology indicative of a resting condition.

Fig. 1.

A Identification of microglia/macrophages (via H&E and F4/80 staining) in uninjured mice (no crush injury) injected with either saline or α-gal nanoparticles at 4X magnification. The dotted box represents the approximate location of the micro-injection in serial sections. B F4/80 staining in saline-injected mice and C α-gal nanoparticle injected mice are shown at higher magnification (20X) cross sections. Black arrows highlight the amoeboid morphology of activated F4/80 cells at the injection site in the α-gal group. Scale bar = 100 µm

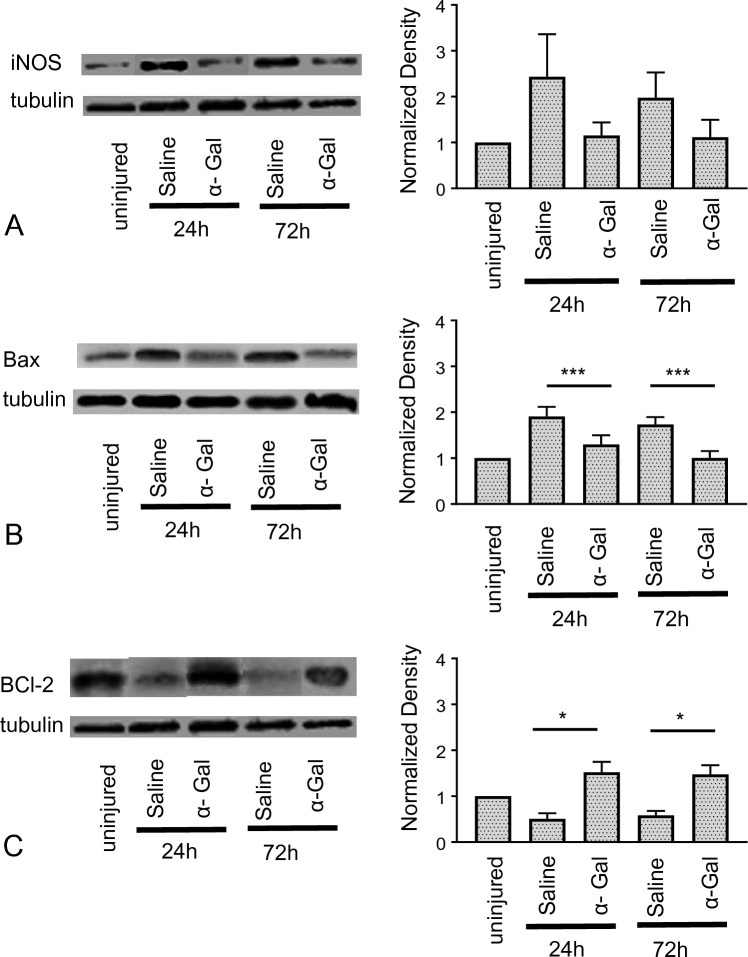

Changes in iNOS and cell apoptosis post-SCI

At 24 h and 72 h post-injury (acute injury phase), western blot analysis was performed to quantify the expression of secondary injury biomarkers iNOS, Bcl-2, and Bax. We observed the iNOS expression increased ~ 2.5 fold after 24 h and ~ 1.8 fold after 72 h in saline-injected mice compared to uninjured. Upon α-gal nanoparticles injection, the mean iNOS levels were lower (~ 1.2 fold) compared to saline injection at both 24 and 72 h post-injury (Fig. 2A). Similarly, we demonstrated the expression for pro-apoptotic marker Bax, increased in mice injected with saline for both time points and decreased in mice injected with α-gal nanoparticles. (Fig. 2B, p < 0.005 compared to saline). Additionally, anti-apoptotic marker Bcl-2 increased ~ 1.5 fold times at both 24 and 72 h compared to saline-injected group (~ 0.7 fold) (Fig. 2C, p < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Modulation of iNOS and apoptosis associated proteins post-SCI: Mice injected with either α-gal nanoparticles or saline after SCI were sacrificed at time points of 24 and 72 h post injury. iNOS, Bax and Bcl-2 expression was quantified with Western Blot. The corresponding plots represent densitometric results relative to uninjured spinal cord segments for A iNOS, B Bax and C Bcl-2. ***p < 0.0005, *p < 0.05, n = 4 animals per group. Tubulin was used as the loading control

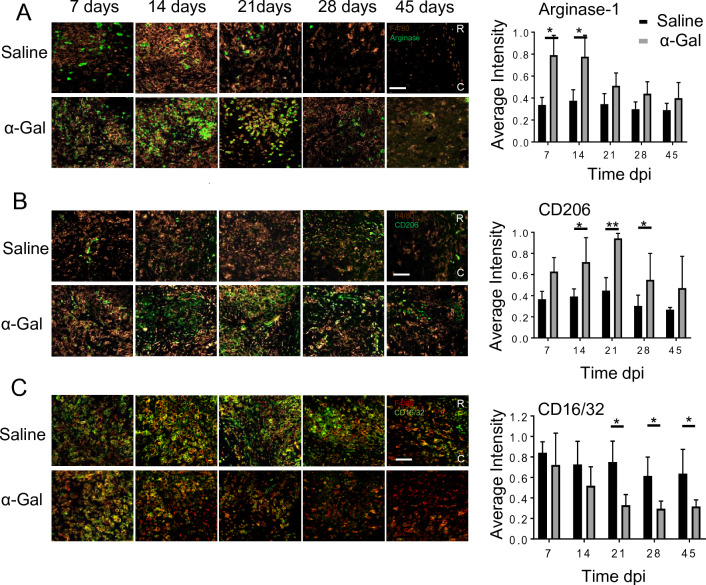

Expression of anti/pro-inflammatory markers post-SCI

Immunohistochemical analysis post-SCI shows that Arginase-1 expression, within and bordering the injury site (T9-T10) increased in the α-gal treated group when compared to saline-injected mice at 7, 14, and 21 dpi (Fig. 3A, p < 0.05). By 28 and 45 dpi, the level of Arginase-1 expression significantly decreased and was comparable in both groups. In cord segments stained with CD206 (anti-inflammatory marker), we found increased CD206 expression in the α-gal cohort when compared to saline-injected mice at 14, 21, and 28 dpi (Fig. 3B, p < 0.05). The level of CD206 peaked between 14 and 21 dpi. Afterwards, the number of cells expressing CD206 decreased. Similar to Arginase-1, CD206 expression in the saline group was relatively consistent throughout the study period. In contrast, the pro-inflammatory marker CD16/32 was elevated in the saline group, especially between 7 and 21 dpi. The increase in CD16/32 lasted through 45 dpi. However, α-gal treated mice had significantly reduced CD16/32 expression, especially at 21, 28 and 45 dpi versus saline (p < 0.05, Fig. 3C). After 21 dpi the number of cells positive for CD16/32 was quite low.

Fig. 3.

Expression of pro and anti-inflammatory markers after crush injury: Longitudinal sections showing the lesion double-labeled with A Arginase-1, B CD206 or C CD16/32 in conjunction with F4/80 at 7, 14, 21, 28 and 45 dpi. Co-localization between the pro/anti-inflammatory markers and F4/80 were used to ascertain the macrophage/microglia phenotype. Quantification of the normalized fluorescence intensity of the respective markers are shown in the right hand-panels, n = 4 animals per group. ***p < 0.005, *p < 0.05. Scale bar = 100 µm

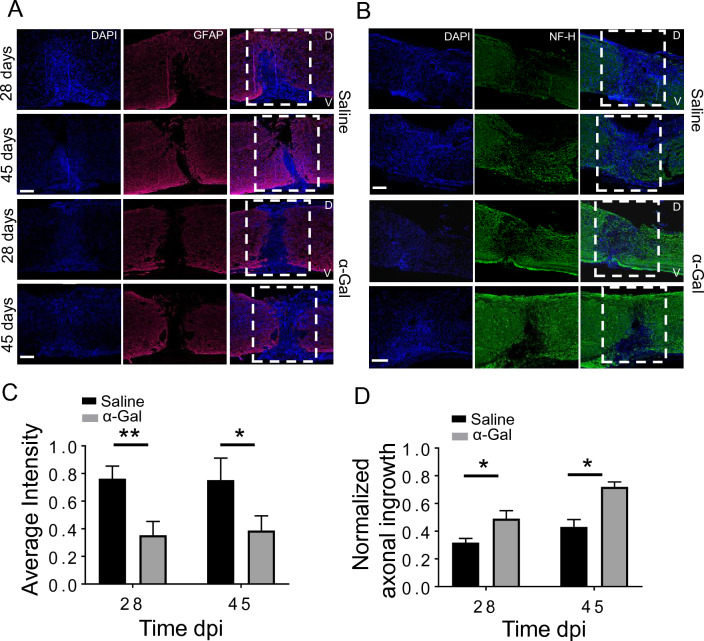

Evaluation of astrogliosis and axonal regrowth post SCI

Histological results show that GFAP expression within and bordering the injury site was higher in the saline-injected mice versus α-gal group at 28 dpi. (Fig. 4A). This trend was also apparent at 45 dpi (Fig. 4A, *C p < 0.005 for 28 days and p < 0.05 for 45 days) where the astrocyte populations in the saline group penetrated deeper into to wound epicenter. In contrast, astrocytes did not migrate significantly into the wound interior in the α-gal group. We observed increased neurofilament staining in the α-gal cohort near the injury site at 28 and 45 dpi versus the saline-injected mice (Fig. 4B). The average axonal ingrowth into the ROI was significantly higher both at 28 and 45 dpi in the α-gal nanoparticle injected mice compared to saline control. The saline sections showed very sparse NF staining within the lesion. In some sections in the α-gal group, axons can be observed traversing the lesion in small numbers.

Fig. 4.

Expression of GFAP and axonal ingrowth: Longitudinal spinal cord sections at 28 or 45 dpi stained either for A. GFAP or B. NF-H. DAPI was used to stain cell nuclei. White dashed box represents the injury site. D and V represent the dorsal side or V aspect of the injured spinal cord. C. Mean fluorescence intensity of GFAP normalized against dpi, D. Normalized axonal staining within the lesion at 28 and 45 dpi obtained from NF-H stained images, n = 3–4 animals per group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005. Scale bar = 100 µm

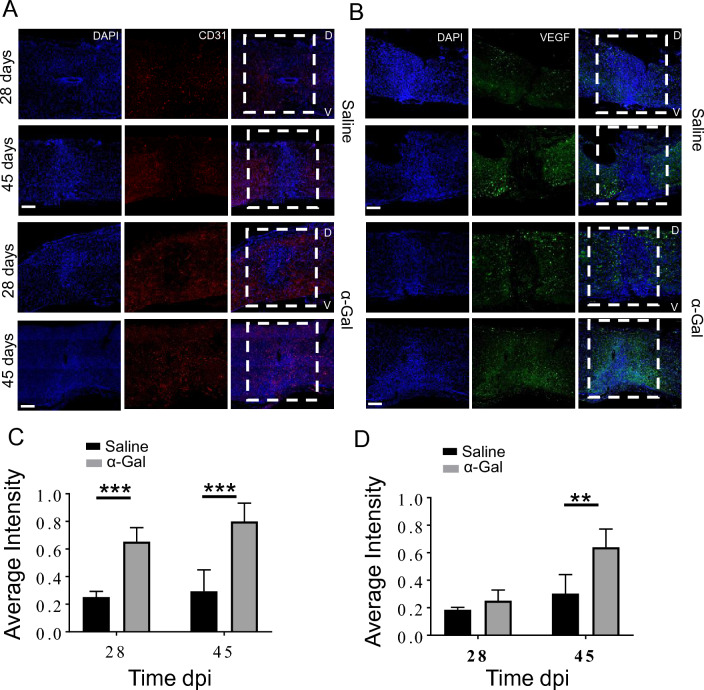

Evaluation of CD31 and VEGF post-SCI

CD31 (endothelial marker) and VEGF expression at 28 and 45 dpi was evaluated with histology (Fig. 5). CD31 expression in α-gal treated group mice was higher at both 28 days and 45 dpi compared to saline control (Fig. 5A). By 45 days, CD31 staining was almost uniformly distributed throughout the lesion in the α-gal group while the saline cohort demonstrated minimal staining in the ROI (Fig. 5A, ***p < 0.0001). Similarly, VEGF expression in the lesion was higher at 28 and 45dpi in α-gal nanoparticles injected mice versus saline (Fig. 5B, *D, **p < 0.005). Co-localization between VEGF and CD31 staining was evident in the serial sections.

Fig. 5.

Expression of CD31 and VEGF: Injured mice were sacrificed at 28 or 45 dpi and the isolated longitudinal cord sections stained either with A. CD31 or B. VEGF. White dashed box denotes the injury site. D and V represent the dorsal or ventral side of the injured cord, respectively. The bar graphs depict the mean fluorescence intensity of C. CD31 and D. VEGF normalized against dpi, n = 4 animals per group, ***p < 0.0001, **p < 0.005. Scale bar = 100 µm

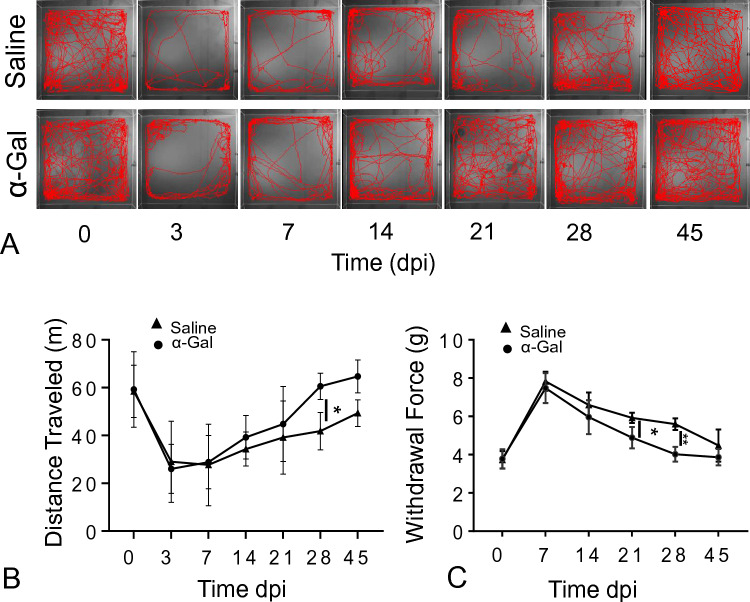

Evaluation of functional outcomes post SCI

The functional changes in α-gal nanoparticle or saline treated groups were evaluated at time point 3 dpi, and during the stabilization period (7–45 dpi). At 3, 7, 14, 21, 30, and 45 dpi, open field activity was performed to evaluate the movement of a mouse after injury (tracking longitudinal movement) [39] and tapered balance beam was used for evaluation of fine motor skills. Moreover, mechanical sensory recovery (ability to the mouse to withdraw its paws as a function of force) [39] was performed in both groups.

Results from the open field test showed that the locomotor response, evaluated in terms of distance moved, was reduced for injured mice (~ 26 m, n = 25) compared to uninjured mice (~ 60 m, n = 25). Moreover, the number of times a mouse crossed the box center was less in injured mice at 72 h compared to uninjured mice. Additionally, we see that the movement traveled by α-gal nanoparticles injected mice was higher at 14 dpi compared to saline-injected mice (Fig. 6A, B). A repeated measure two-way ANOVA revealed that there was a significant time effect in both saline and α-gal nanoparticles injected mice [F (6268) = 1.666, p < 0.005]. Similarly, post-hoc analysis for time and treatment showed that at 28 dpi, there was a significant difference in distance traveled for α-gal nanoparticle injected mice compared to saline-injected mice (n = 25, p < 0.05). Moreover, Tukey’s multiple comparison test reported that there was no significant difference between 21, 28 and 45 dpi in α-gal nanoparticles injected mice compared to uninjured (0 dpi). Likewise, Tukey’s multiple comparison test in saline-injected mice showed no significant difference only at 45 dpi. This suggests that the α-gal nanoparticles injected mice recovered faster compared to saline-injected mice.

Fig. 6.

Time dependent locomotor activity changes as evaluated by open field activity or sensory changes via electric von-Frey in spinal cord injured mice treated with either saline or α-gal nanoparticles. A. Representative 10-min displacement tracing of an individual mouse using EthoWatcher at 0, 3, 7, 14, 21, 28 and 45 dpi. B. Total distance traveled in meters (n ≥ 12 for α-gal and n ≥ 11 for saline). C. Withdrawal force (g) of injured mice obtained as a function of time using electric von Frey (n ≥ 11for saline and n ≥ 12 for α-gal). A repeated two-way ANOVA analysis (mixed effect analysis) with Holm-Šídák multiple comparison to determine the statistical significance among α-gal and saline, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005. By 28 dpi, the distance traveled and the withdrawal force in the α-gal group were not statistically different from those of control uninjured mice

Mechanical allodynia measured using electric von Frey showed that the paw withdrawal response was higher in injured mice at 7 dpi compared to uninjured mice (p < 0.0001, n = 50). However, there was no statistical paw withdrawal difference for both α-gal nanoparticles (n = 27) or saline-injected (n = 25) mice at 7 dpi (~ 7.5 g) (Fig. 6C). At 21 dpi, we observe significant recovery in paw withdrawal response in α-gal nanoparticle injected mice compared to saline-injected mice (Fig. 6C, p < 0.005). A repeated measure two-way ANOVA revealed that there was a significant time and treatment effect in mice, suggesting that the sensory response of the mice recovers with time in both treatment groups [F (5177) = 9.879, p < 0.005]. Moreover, post-hoc analysis for time and treatment showed that at 21 dpi and 28 dpi, there was significant difference in paw withdrawal response in α-gal nanoparticles injected mice compared to saline-injected mice (n = 25, p < 0.0001). Additionally, Tukey’s multiple comparison test show that there was significant difference among all time points in saline-injected mice compared to uninjured mice (0 dpi) (p < 0.05), whereas there was no statistical difference among 28 and 45 dpi in α-gal nanoparticles injected mice compared to uninjured (0 dpi). This suggests that the α-gal nanoparticles injected mice recover sensory response faster compared to saline-injected mice.

Further, the fine motor skills were evaluated using tapered balance beam for both α-gal nanoparticles injected mice (n = 16) and saline-injected mice (n = 16). The average time to cross the 30 mm beam before injury for saline group was 2.27 ± 0.4 s and for α-gal group was 2.66 ± 0.6 s. The time to cross the beam remained very similar to uninjured mice in both the groups for 30 mm beam size post-injury. Similarly, no significant difference was observed in time to cross in both groups mice post- injury for 24 mm beam, (Fig. 7A). For 18 mm beam thickness, we observe that the time to cross for saline group was 5.06 ± 0.6 s and for α-gal injected group was 4.66 ± 0.5 s. A repeated measure two-way ANOVA revealed that there was a significant difference among time crossed for 18 mm beam size at 14 and 21 dpi in α-gal nanoparticles injected mice compared to saline-injected mice (p < 0.05, Fig. 7A). Moreover, for narrow beam sizes 12 mm and 6 mm, the average time to cross was higher in post injured mice. The average time to cross the beam at 7 dpi for 12 mm beam was 15.05 ± 2 0.9 s for saline group and 12.48 ± 2.8 s for α-gal nanoparticle injected group. Similarly, for 6 mm beam size, the time to cross at 7 dpi was 18.6 ± 4.9 s for saline group and 15.56 ± 2.9 s for α-gal nanoparticles injected mice. Additionally, post-hoc analysis for time to cross showed that, for the 12 mm beam size, there was significant difference among treatment groups at 21, 28 and 45 dpi (p < 0.05, Fig. 7A), suggesting that α-gal nanoparticles injected mice crossed faster in comparison to saline-injected mice. Similarly, for 6 mm beam size, the α-gal injected mice crossed faster compared to saline-injected mice at 28 and 45 dpi, (p < 0.05, Fig. 7A).

Fig. 7.

Time dependent fine-motor activity changes as evaluated by tapered balance beam in spinal injured mice treated with either saline or α-gal nanoparticles. A. Average time (sec) to traverse the beams of different sizes as a function of time. B. Total number of foot slips. A repeated two-way ANOVA analysis (mixed effect analysis) with Holm-Šídák multiple comparison tests was performed to determine the statistical significance between groups. *p < 0.05, n ≥ 10 animals per group

Furthermore, we observed that there were no foot slips at 30 mm beam size (Fig. 7B). For 24 mm beam size, there was no difference in foot slips between the α-gal nanoparticles injected mice and saline-injected mice (Fig. 7B). For beam size 18 mm and at all-time points, the α-gal nanoparticles injected mice had fewer foot slips compared to saline-injected mice (Fig. 7B). We observe that both groups mice had foot slips before surgery in 12 mm (~ 5 foot slips) and 6 mm (~ 6 foot slips). Post injury, the mice were able to cross the beam but had higher foot slips for both beam sizes at 3 and 7 dpi compared to uninjured mice. But the α-gal nanoparticles injected mice at 14, 21, 28 and 45 dpi had significantly reduced foot slips compared to saline-injected mice at 12 mm and 6 mm beam sizes (p < 0.05, Fig. 7B).

Discussion

The immune response plays an integral role after SCI and the associated sequelae and can either exacerbate or facilitate the repair process. The traditional dogma in coping with injury inflammation has been one of suppression and this strategy has led to several (and ultimately, rather unsuccessful) human trials with the corticosteroid methylprednisolone [40–42]. Indeed, recent data reveal a more complex fate for immune cells that extend beyond the initial debridement phase [12, 13, 43, 44] and it has been suggested that SCI pathophysiology shares many parallels with chronic wound healing [9]. For instance, in normal wound healing, pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages produce pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α and phagocytose foreign, cellular and extracellular matrix debris [7, 45, 46]. While necessary for this housekeeping function, these M1 macrophages ultimately transition to an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype and secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines (including IL-10 and TGF-β) that encourage cell proliferation and tissue remodeling [9, 46]. In chronic wounds, however, the continued presence of pro-inflammatory macrophages during the inflammation phase and the dysfunctional transition to the M2 phenotype leads to non-healing wounds and fibrotic scarring [47]. Similarly, after SCI, aberrant macrophage transition is observed and the long-term presence of M1 macrophages may contribute to the inhibitory post-SCI microenvironment [9].

In this work, we propose a novel approach for altering immune cell populations after SCI by harnessing the innate immune response. While stimulating natural immunity with foreign pathogens has been investigated in SCI, inflammogens that act on toll-like receptors can be cytotoxic and any small improvement in outcomes is offset by the potential for worsening the injury [17, 48]. This may be explained by the subsets of inflammatory cells (i.e. macrophages) being activated by these agents. In contrast, the α-gal epitope has proven to be a much safer and more effective alternative to immunomodulation. Seminal studies by Galili et al. showed that local application of nanoparticles presenting α-gal epitopes to wounds in anti-Gal producing mice can accelerate wound healing and reduce scarring [24, 25, 27]. In following experiments involving myocardial infarction, GT-KO mice receiving direct α-gal nanoparticle injections into the injured myocardium displayed a much smaller scar size and restoration of normal cardiac muscle contractile function [19]. The nanoparticles predominately recruited pro-healing macrophages to the injection site via chemotactic complement peptides (such as C5a, C3a) produced by the activation of the complement system through the binding of anti-Gal to α-gal nanoparticles. The recruited macrophages further become activated via interaction between their Fc receptors and the Fc tail of anti-Gal coating the α-gal nanoparticles. The activated macrophages in turn secrete a variety of cytokines/growth factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) that induce neovascularization and tissue repair [25]. These results were confirmed by our companion in vitro study, which showed α-gal nanoparticles can further stimulate and polarize human microglia towards a pro-healing phenotype. Since the CNS post-injury milieu includes both resident microglia and monocyte derived macrophages migrating from the blood, the aggregate data provide justification for applying α-gal nanoparticles in SCI.

Our experimental data demonstrate the feasibility of α-gal nanoparticles as immunomodulator agents. Pilot injections of α-gal nanoparticles directly into the uninjured cord elicited a strong immune response, as depicted by higher F4/80 + staining near the injection site (Fig. 1). We selected the α-gal nanoparticle dosing (10 mg/ml) to be the same as other studies involving burn and wound injuries [24, 25]. Cells mobilized to the injection site with α-gal nanoparticles were well clustered and hypertrophic, indicative of an activated state, while peri-wound microglia still retained a resting stellate morphology. In contrast, mice injected with saline showed far fewer activated inflammatory cells at the injection site. The trials imply that exsanguination from ruptured capillaries (via injection needle injury) can release anti-Gal into the cord parenchyma and bind with α-gal nanoparticles. This α-gal nanoparticle/anti-Gal complex then recruits and activates immune cells in a manner similar to what has been observed in experiments in wounds and in cardiac tissue.

In subsequent experiments with spinal injured mice, the α-gal group again showed significantly more F4/80 + cells at the application site compared to control. These recruited immune cells were predominately Arginase-1 and CD206 positive but negative for CD16/32. CD206 is a mannose receptor marker that is indicative of the M2 subtype [9]. M2 macrophages expressing CD206 have shown to facilitate tissue remodeling by clearing dying cells without causing damage [7, 9, 49]. Likewise, Arginase-1 is beneficial following SCI as it promotes axon survival and axon regeneration [50, 51]. Arginase-1 was also expressed by F4/80-cells, suggesting other cell types (such as neurons) may also be producing arginase. In the saline cohort, however, inflammatory cells within the lesion had reduced Arginase-1 and CD206 expression but an increase in CD16/32 expression. CD16/32 is characteristic for M1 polarized macrophages [52]. These immunohistochemical results are consistent with previous investigations whereby subcutaneous implantation of sponges containing α-gal nanoparticles in GT-KO mice resulted in recruitment of macrophages expressing high levels of IL-10 and Arginase-1 [20]. The increase in both Arginase-1 and C206 positive cells without a corresponding increase in CD16/32 in the first 21 dpi suggests that α-gal nanoparticles predominately recruited pro-healing M2 macrophages to the lesion. After 28 days, the total number of inflammatory cells significantly diminished. This timing of macrophage tapering is consistent with other reports [5, 9, 53–55].

We also suspect that in the acute phase of SCI, α-gal nanoparticle application may be conferring some neuroprotection by regulating apoptosis associated proteins and suppression of iNOS. For instance, expression of Bcl-2 in the α-gal group was similar to uninjured controls and significantly higher versus saline treated mice. Overexpression of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein can prevent neuronal cell death [56]. Bax, a pro-apoptotic marker for mitochondrial mediated cell death, was lower in the α-gal group compared to the saline group. Bax expression after spinal cord injury typically increases, especially in glia [57, 58]. This was consistent with our observations in the control group. Similarly, iNOS a marker for M1 macrophages and a precursor to NO, also decreased in the early days after SCI. iNOS generally peaks at 72 h [29, 30]. Increased iNOS leads to NO generation. NO is a major constituent of secondary injury and like other radicals, leads to multiple deleterious effects in cells [59–61]. The decrease in iNOS in vivo with α-gal group is notable since we were not able to differentiate iNOS generation in vitro study using HMC3 microglia. These discrepancies highlight the limitation of using cell lines, in this case the constitutive expression of the NOX4 gene by HMC3 cells could not anticipate observed in vivo changes.

Histological assessment of cord tissue in the subacute phase of injury suggests α-gal nanoparticle therapy created a microenvironment that is more conducive to axonal regeneration. The number of hyper-reactive astrocytes (GFAP) found in the crush epicenter was lower at 28 dpi in α-gal treated animals compared to control (Fig. 4). Reactive astrocytes can inhibit axonal regeneration through several mechanisms. Astrocytes secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines [62, 63] and increased inflammation results in neuronal and glial cell death and axonal dieback [64, 65]. Astrocytes also produce chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CPSGs), compounds that promote scarring and deter axon pathfinding [10, 62, 63]. The astroglial scar also creates a physical barrier preventing outgrowth in regenerating axons [66]. Indeed, the higher neurofilament staining indicates fewer obstacles to axonal outgrowth in the α-gal group. Deeper axonal penetration into the lesion was present at 28 dpi with the α-gal group. Even minor bridging of distal and proximal zones was observed. In contrast, axonal growth in the saline cohort stopped well short of the lesion. It is likely that the increased axonal staining in the α-gal group is due to some combination of axonal sparing (i.e. via neuroprotection), axonal sprouting and regeneration. Moreover, in regions of high neurofilament staining, both VEGF and CD31 expression were elevated. Prior studies in skin wounds revealed an association between increased macrophage VEGF production and improved angiogenesis using α-gal nanoparticle treatment [20, 25]. VEGF administered after CNS injury was also reported to promote axon regeneration [67], with neovascularization also co-localizing with areas of new axon growth [68]. Our in vitro experiments found VEGF production to trend higher in HMC3 microglia exposed to α-gal nanoparticles. Thus, it is probable that enhanced angiogenesis from increased VEGF secretion is another mechanism by which axonal regeneration is supported. SCI is often considered a white matter pathology, with damage to key tracts (i.e. corticospinal tract) affecting motor function [69–71]. Tests such as the open field activity box and the tapered balance beam can be used to gauge gross locomotor activity and fine motor coordination, respectively. Meanwhile, gray matter destruction often leads to sensory deficits, which can be detected via electric von Frey [72]. In a crush injury model, the hind limbs are not completely paralyzed and some spontaneous functional recovery is expected over time [73]. Nonetheless, we observed that animals treated with α-gal nanoparticles were much more active and explored the entirety of the chamber. The total distance traveled was significantly higher versus saline control (Fig. 6). Suppression of locomotor activity is common in spinal injured mice [74] but α-gal treated animals reached activity levels nearing pre-injury. Moreover, fine motor skills also improved as treated mice were able to cross the tapered beams faster compared to saline-injected mice at all beam widths. Most notably at the narrower beam sizes of 6 mm and 12 mm, improvements in both the time to cross and number of foot slips were detectable as early as 21 dpi (Fig. 7). This trend was consistent for all time periods even when considering training associated acclimation. Motor improvements were also accompanied by restoration of sensory function. Hind limb sensory response was impaired immediately after injury as the force required to elicit a withdrawal doubled after the first week. This was anticipated and comparable to studies in spinal injured dogs, in which a higher threshold for noxious stimuli was noted at 3, 10 and 20 dpi versus control [75, 76]. The withdrawal force slowly decreased over time, suggesting some spontaneous recovery, but the α-gal nanoparticle treated group had a consistently lower force value versus the saline group (Fig. 6). We further did not observe hypoalgesia (allodynia), which is sometimes reported after SCI [77]. Hypoalgesia would result in a significant reduction in the withdrawal force. The collective recovery in sensorimotor function without occurrence of mechanical allodynia are consistent with the biochemical and histological findings of axonal sparing and/or improved axon growth into the lesion. These behavioral improvements can be observed as early as 21 dpi and continued throughout the study period.

The experimental data provide proof of concept for using α-gal nanoparticles as an SCI therapeutic and corroborate earlier findings in dermal wounds [24, 25] and cardiac tissue [19]. The putative mechanism of action appears to be a modulatory effect on macrophages/microglia and is illustrated in Fig. 8. We emphasize that since monocytes derived macrophages and resident microglia share many phenotypic characteristics, we were unable to differentiate between the two subpopulations with simple immunostaining. It is well known that after SCI, macrophages originating from the blood (spleen or bone marrow source) co-mingle with resident microglia within the cord [14, 78]. In addition, it is unclear if these recruited macrophages ultimately leave the CNS or become integrated into the local microglial population. Nonetheless, since both M2 microglia and macrophages have comparable functional responses to the anti-Gal/α-gal nanoparticles immune complex (as discussed in our companion paper) we surmise that the net therapeutic effect is the same, irrespective of cell lineage. Future studies in larger animal systems such as KO pigs to validate and optimize the dosing regimen would be beneficial in directing potential clinical trials.

Fig. 8.

Putative mechanism of therapeutic action by α-gal nanoparticles. A. Nanoparticles injected into the injured cord bind to natural anti-Gal antibodies leaked from ruptured capillaries. The binding of anti-Gal to α-gal epitopes on the α-gal nanoparticles activates the complement system to release complement cleavage chemotactic peptides such as C5a, C3a that recruit macrophages and microglia. These recruited cells bind to the anti-Gal coated α-gal nanoparticles and further polarize them into the M2 state. B. Recruited M2 macrophages and microglia secrete neuroprotective and pro-healing factors to promote tissue repair, neovascularization and axonal regeneration (C)

Conclusion

This study is the first to demonstrate that α-gal nanoparticles can be used to modulate the immune response in the injured CNS. The nanoparticles bind to anti-Gal antibodies released into the hemorrhagic lesion to subsequently recruit pro-healing macrophages to the injection site. In light of our parallel companion in vitro study, it is likely that the anti-Gal/α-gal nanoparticles immune complexes also stimulate and activates resident microglia. Together, these macrophages/microglia secrete anti-inflammatory factors that provide neuroprotection, induce angiogenesis, reduce the astroglial scar and facilitate axonal ingrowth into the lesion. These biochemical and cellular outcomes also translated into improved sensorimotor scores. The positive results justify further studies on the efficacy and safety of α-gal nanoparticles therapy as a candidate for ameliorating the effects of SCI in anti-Gal producing large animal models.

Acknowledgements

We thank Christa Crain (Center for Comparative Translational Research (CCTR) Senior Research Technician) for assistance during surgeries. We thank Purdue University Histology Research Laboratory (Victor Bernal-Crespo and Mackenzie J McIntosh), a core facility of the NIH-funded Indiana Clinical and Translational Science Institute for histology work. This research was partly funded by the State of Indiana and Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute (CTSI, Indiana State Department of Health (Grant # 204200 to JL) and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke R21 (No. 1R21NS115094-01). We thank Purdue Animal Behavior Core for the use of the animal behavioral equipment.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare conflict of interest.

Ethical statement

All mice experiments including breeding, care and surgery were done in accordance to Purdue University IACUC (#1110000060).

Footnotes

Abbreviation: SCI-spinal cord injury.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Anwar MA, Al Shehabi TS, Eid AH. Inflammogenesis of secondary spinal cord injury. Front Cell Neurosci. 2016;10:98. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2016.00098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hawthorne AL, Popovich PG. Emerging concepts in myeloid cell biology after spinal cord injury. Neurotherapeutics. 2011;8(2):252–261. doi: 10.1007/s13311-011-0032-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klebanoff SJ, Vadas MA, Harlan JM, Sparks LH, Gamble JR, Agosti JM, et al. Stimulation of neutrophils by tumor-necrosis-factor. J Immunol. 1986;136(11):4220–4225. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.136.11.4220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shechter R, Miller O, Yovel G, Rosenzweig N, London A, Ruckh J, et al. Recruitment of beneficial M2 macrophages to injured spinal cord is orchestrated by remote brain choroid plexus. Immunity. 2013;38(3):555–569. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kong XY, Gao J. Macrophage polarization: a key event in the secondary phase of acute spinal cord injury. J Cell Mol Med. 2017;21(5):941–954. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.An N, Yang J, Wang H, Sun S, Wu H, Li L, et al. Mechanism of mesenchymal stem cells in spinal cord injury repair through macrophage polarization. Cell Biosci. 2021;11(1):41. doi: 10.1186/s13578-021-00554-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kigerl KA, Gensel JC, Ankeny DP, Alexander JK, Donnelly DJ, Popovich PG. Identification of two distinct macrophage subsets with divergent effects causing either neurotoxicity or regeneration in the injured mouse spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2009;29(43):13435–13444. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3257-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell L, Saville CR, Murray PJ, Cruickshank SM, Hardman MJ. Local arginase 1 activity is required for cutaneous wound healing. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133(10):2461–2470. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gensel JC, Zhang B. Macrophage activation and its role in repair and pathology after spinal cord injury. Brain Res. 2015;1619:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clifford T, Finkel Z, Rodriguez B, Joseph A, Cai L. Current advancements in spinal cord injury research-glial scar formation and neural regeneration. Cells. 2023;12(6):853. doi: 10.3390/cells12060853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hellenbrand DJ, Reichl KA, Travis BJ, Filipp ME, Khalil AS, Pulito DJ, et al. Sustained interleukin-10 delivery reduces inflammation and improves motor function after spinal cord injury. J Neuroinflammation. 2019;16(1):93. doi: 10.1186/s12974-019-1479-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma SF, Chen YJ, Zhang JX, Shen L, Wang R, Zhou JS, et al. Adoptive transfer of M2 macrophages promotes locomotor recovery in adult rats after spinal cord injury. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;45:157–170. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Popovich PG, Guan Z, Wei P, Huitinga I, van Rooijen N, Stokes BT. Depletion of hematogenous macrophages promotes partial hindlimb recovery and neuroanatomical repair after experimental spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 1999;158(2):351–365. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ginhoux F, Lim S, Hoeffel G, Low D, Huber T. Origin and differentiation of microglia. Front Cell Neurosci. 2013;7:45. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clemente CD, Windle WF. Regeneration of severed nerve fibers in the spinal cord of the adult cat. J Comp Neurol. 1954;101(3):691–731. doi: 10.1002/cne.901010304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guth L, Zhang Z, DiProspero NA, Joubin K, Fitch MT. Spinal cord injury in the rat: treatment with bacterial lipopolysaccharide and indomethacin enhances cellular repair and locomotor function. Exp Neurol. 1994;126(1):76–87. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1994.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Popovich PG, Tovar CA, Wei P, Fisher L, Jakeman LB, Basso DM. A reassessment of a classic neuroprotective combination therapy for spinal cord injured rats: LPS/pregnenolone/indomethacin. Exp Neurol. 2012;233(2):677–685. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.11.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galili U. Anti-Gal: an abundant human natural antibody of multiple pathogeneses and clinical benefits. Immunology. 2013;140(1):1–11. doi: 10.1111/imm.12110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galili U, Zhu Z, Chen J, Goldufsky JW, Schaer GL. Near complete repair after myocardial infarction in adult mice by altering the inflammatory response with intramyocardial injection of alpha-gal nanoparticles. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:719160. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.719160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaymakcalan OE, Abadeer A, Goldufsky JW, Galili U, Karinja SJ, Dong X, et al. Topical alpha-gal nanoparticles accelerate diabetic wound healing. Exp Dermatol. 2020;29(4):404–413. doi: 10.1111/exd.14084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahuja CS, Wilson JR, Nori S, Kotter MRN, Druschel C, Curt A, et al. Traumatic spinal cord injury. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17018. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alizadeh A, Dyck SM, Karimi-Abdolrezaee S. Traumatic spinal cord injury: an overview of pathophysiology, models and acute injury mechanisms. Front Neurol. 2019;10:282. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joshi M, Fehlings MG. Development and characterization of a novel, graded model of clip compressive spinal cord injury in the mouse: Part 1 Clip design, behavioral outcomes, and histopathology. J Neurotrauma. 2002;19(2):175–90. doi: 10.1089/08977150252806947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galili U, Wigglesworth K, Abdel-Motal UM. Accelerated healing of skin burns by anti-Gal/α-gal liposomes interaction. Burns. 2010;36(2):239–251. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wigglesworth KM, Racki WJ, Mishra R, Szomolanyi-Tsuda E, Greiner DL, Galili U. Rapid recruitment and activation of macrophages by anti-Gal/alpha-Gal liposome interaction accelerates wound healing. J Immunol. 2011;186(7):4422–4432. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galili U. Antibody production and tolerance to the alpha-gal epitope as models for understanding and preventing the immune response to incompatible ABO carbohydrate antigens and for alpha-gal therapies. Front Mol Biosci. 2023;10:1209974. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2023.1209974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hurwitz ZM, Ignotz R, Lalikos JF, Galili U. Accelerated porcine wound healing after treatment with α-gal nanoparticles. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(2):242e–e251. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31823aebb1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luo J, Borgens R, Shi R. Polyethylene glycol immediately repairs neuronal membranes and inhibits free radical production after acute spinal cord injury. J Neurochem. 2002;83(2):471–480. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahn M, Lee C, Jung K, Kim H, Moon C, Sim KB, et al. Immunohistochemical study of arginase-1 in the spinal cords of rats with clip compression injury. Brain Res. 2012;1445:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao W, Li JM. Targeted siRNA delivery reduces nitric oxide mediated cell death after spinal cord injury. J Nanobiotechnology. 2017 doi: 10.1186/s12951-017-0272-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hata K, Fujitani M, Yasuda Y, Doya H, Saito T, Yamagishi S, et al. RGMa inhibition promotes axonal growth and recovery after spinal cord injury. J Cell Biol. 2006;173(1):47–58. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200508143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niemi JP, DeFrancesco-Oranburg T, Cox A, Lindborg JA, Echevarria FD, McCluskey J, et al. The conditioning lesion response in dorsal root ganglion neurons is inhibited in oncomodulin knock-out mice. eNeuro. 2022;9(1):ENEURO-0477. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0477-21.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Urban MW, Ghosh B, Block CG, Strojny LR, Charsar BA, Goulao M, et al. Long-distance axon regeneration promotes recovery of diaphragmatic respiratory function after spinal cord injury. eNeuro. 2019;6(5):ENEURO-0096. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0096-19.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carter RJ, Morton J, Dunnett SB. Motor coordination and balance in rodents. Curr Protoc Neurosci. 2001;15(1):8–12. doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0812s15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harrison DJ, Busse M, Openshaw R, Rosser AE, Dunnett SB, Brooks SP. Exercise attenuates neuropathology and has greater benefit on cognitive than motor deficits in the R6/1 Huntington's disease mouse model. Exp Neurol. 2013;248:457–469. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tung VW, Burton TJ, Quail SL, Mathews MA, Camp AJ. Motor performance is impaired following vestibular stimulation in ageing mice. Front Aging Neurosci. 2016;8:12. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2016.00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wagner JM, Sichler ME, Schleicher EM, Franke TN, Irwin C, Low MJ, et al. Analysis of motor function in the Tg4-42 mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Front Behav Neurosci. 2019;13:107. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2019.00107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deuis JR, Dvorakova LS, Vetter I. Methods used to evaluate pain behaviors in rodents. Front Mol Neurosci. 2017;10:284. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahmed RU, Alam M, Zheng YP. Experimental spinal cord injury and behavioral tests in laboratory rats. Heliyon. 2019;5(3):e01324. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bracken MB, Collins WF, Freeman DF, Shepard MJ, Wagner FW, Silten RM, et al. Efficacy of methylprednisolone in acute spinal cord injury. JAMA. 1984;251(1):45–52. doi: 10.1001/jama.1984.03340250025015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Collins WF, Holford TR, Young W, Baskin DS, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of methylprednisolone or naloxone in the treatment of acute spinal-cord injury. Results of the second national acute spinal cord injury study. New Engl J Med. 1990;322(20):1405–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199005173222001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Hellenbrand KG, Collins WF, Leo LS, Freeman DF, et al. Methylprednisolone and neurological function 1 year after spinal cord injury. Results of the national acute spinal cord injury study. J Neurosurg. 1985;63(5):704–13. doi: 10.3171/jns.1985.63.5.0704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schwartz M. "Tissue-repairing" blood-derived macrophages are essential for healing of the injured spinal cord: from skin-activated macrophages to infiltrating blood-derived cells? Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24(7):1054–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rapalino O, Lazarov-Spiegler O, Agranov E, Velan GJ, Yoles E, Fraidakis M, et al. Implantation of stimulated homologous macrophages results in partial recovery of paraplegic rats. Nat Med. 1998;4(7):814–821. doi: 10.1038/nm0798-814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jurga AM, Paleczna M, Kuter KZ. Overview of general and discriminating markers of differential microglia phenotypes. Front Cell Neurosci. 2020;14:198. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2020.00198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shafqat A, Albalkhi I, Magableh HM, Saleh T, Alkattan K, Yaqinuddin A. Tackling the glial scar in spinal cord regeneration: new discoveries and future directions. Front Cell Neurosci. 2023;17:1180825. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2023.1180825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krzyszczyk P, Schloss R, Palmer A, Berthiaume F. The Role of Macrophages in acute and chronic wound healing and interventions to promote pro-wound healing phenotypes. Front Physiol. 2018;9:419. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gensel JC, Nakamura S, Guan Z, van Rooijen N, Ankeny DP, Popovich PG. Macrophages promote axon regeneration with concurrent neurotoxicity. J Neurosci. 2009;29(12):3956–3968. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3992-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nauta AJ, Raaschou-Jensen N, Roos A, Daha MR, Madsen HO, Borrias-Essers MC, et al. Mannose-binding lectin engagement with late apoptotic and necrotic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33(10):2853–2863. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fenn AM, Hall JC, Gensel JC, Popovich PG, Godbout JP. IL-4 signaling drives a unique arginase+/IL-1beta+ microglia phenotype and recruits macrophages to the inflammatory CNS: consequences of age-related deficits in IL-4Ralpha after traumatic spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2014;34(26):8904–8917. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1146-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang J, Li Y, Duan Z, Kang J, Chen K, Li G, et al. The effects of the M2a macrophage-induced axonal regeneration of neurons by arginase 1. 2020. Biosci Rep. 2020 doi: 10.1042/BSR20193031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu C, Li Y, Yu J, Feng L, Hou S, Liu Y, et al. Targeting the shift from M1 to M2 macrophages in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mice treated with fasudil. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2):e54841. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Novak ML, Koh TJ. Macrophage phenotypes during tissue repair. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;93(6):875–881. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Novak ML, Koh TJ. Phenotypic transitions of macrophages orchestrate tissue repair. Am J Pathol. 2013;183(5):1352–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang B, Bailey WM, Kopper TJ, Orr MB, Feola DJ, Gensel JC. Azithromycin drives alternative macrophage activation and improves recovery and tissue sparing in contusion spinal cord injury. J Neuroinflammation. 2015;12:218. doi: 10.1186/s12974-015-0440-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu K, Chen QX, Li FC, Chen WS, Lin M, Wu QH. Spinal cord decompression reduces rat neural cell apoptosis secondary to spinal cord injury. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2009;10(3):180–187. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B0820161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hausmann ON. Post-traumatic inflammation following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2003;41(7):369–378. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kotipatruni RR, Dasari VR, Veeravalli KK, Dinh DH, Fassett D, Rao JS. p53- and Bax-mediated apoptosis in injured rat spinal cord. Neurochem Res. 2011;36(11):2063–2074. doi: 10.1007/s11064-011-0530-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hibbs JB, Jr, Vavrin Z, Taintor RR. L-arginine is required for expression of the activated macrophage effector mechanism causing selective metabolic inhibition in target cells. J Immunol. 1987;138(2):550–565. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.138.2.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang Z, Ming XF. Functions of arginase isoforms in macrophage inflammatory responses: impact on cardiovascular diseases and metabolic disorders. Front Immunol. 2014;5:533. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Isaksson J, Farooque M, Olsson Y. Improved functional outcome after spinal cord injury in iNOS-deficient mice. Spinal Cord. 2005;43(3):167–170. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sofroniew MV. Astrocyte barriers to neurotoxic inflammation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16(5):249–263. doi: 10.1038/nrn3898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sofroniew MV, Vinters HV. Astrocytes: biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119(1):7–35. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0619-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cregg JM, DePaul MA, Filous AR, Lang BT, Tran A, Silver J. Functional regeneration beyond the glial scar. Exp Neurol. 2014;253:197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hackett AR, Lee JK. Understanding the NG2 glial scar after spinal cord injury. Front Neurol. 2016;7:199. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2016.00199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li X, Li M, Tian L, Chen J, Liu R, Ning B. Reactive astrogliosis: implications in spinal cord injury progression and therapy. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020;2020:9494352. doi: 10.1155/2020/9494352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Facchiano F, Fernandez E, Mancarella S, Maira G, Miscusi M, D'Arcangelo D, et al. Promotion of regeneration of corticospinal tract axons in rats with recombinant vascular endothelial growth factor alone and combined with adenovirus coding for this factor. J Neurosurg. 2002;97(1):161–168. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.97.1.0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dray C, Rougon G, Debarbieux F. Quantitative analysis by in vivo imaging of the dynamics of vascular and axonal networks in injured mouse spinal cord. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(23):9459–9464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900222106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen W, Xia M, Guo C, Jia Z, Wang J, Li C, et al. Modified behavioural tests to detect white matter injury- induced motor deficits after intracerebral haemorrhage in mice. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):16958. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-53263-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nampoothiri SS, Potluri T, Subramanian H, Krishnamurthy RG. Rodent gymnastics: neurobehavioral assays in ischemic stroke. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54(9):6750–6761. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-0195-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shefner JM. Strength testing in motor neuron diseases. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14(1):154–160. doi: 10.1007/s13311-016-0472-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Grulova I, Slovinska L, Nagyova M, Cizek M, Cizkova D. The effect of hypothermia on sensory-motor function and tissue sparing after spinal cord injury. Spine J Off J North Am Spine Soc. 2013;13(12):1881–1891. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.06.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Plemel JR, Duncan G, Chen KW, Shannon C, Park S, Sparling JS, et al. A graded forceps crush spinal cord injury model in mice. J Neurotrauma. 2008;25(4):350–370. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mills CD, Grady JJ, Hulsebosch CE. Changes in exploratory behavior as a measure of chronic central pain following spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2001;18(10):1091–1105. doi: 10.1089/08977150152693773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Moore SA, Hettlich BF, Waln A. The use of an electronic von Frey device for evaluation of sensory threshold in neurologically normal dogs and those with acute spinal cord injury. Vet J. 2013;197(2):216–219. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Song RB, Basso DM, da Costa RC, Fisher LC, Mo X, Moore SA. von Frey anesthesiometry to assess sensory impairment after acute spinal cord injury caused by thoracolumbar intervertebral disc extrusion in dogs. Vet J. 2016;209:144–149. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2015.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Masri R, Quiton RL, Lucas JM, Murray PD, Thompson SM, Keller A. Zona incerta: a role in central pain. J Neurophysiol. 2009;102(1):181–191. doi: 10.1152/jn.00152.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Blomster LV, Brennan FH, Lao HW, Harle DW, Harvey AR, Ruitenberg MJ. Mobilisation of the splenic monocyte reservoir and peripheral CX(3)CR1 deficiency adversely affects recovery from spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 2013;247:226–240. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.