Abstract

BACKGROUND

Melioidosis, an infectious disease caused by Burkholderia pseudomallei (B. pseudomallei), occurs endemically in Southeast Asia and Northern Australia and is a serious opportunistic infection associated with a high mortality rate.

CASE SUMMARY

A 58-year-old woman presented with scattered erythema on the skin of her limbs, followed by fever and seizures. B. pseudomallei was isolated successively from the patient’s urine, blood, and pus. Magnetic resonance imaging showed abscess formation involving the right forehead and the right frontal region. Subsequently, abscess resection and drainage were performed. The patient showed no signs of relapse after 4 months of follow-up visits post-treatment.

CONCLUSION

We present here a unique case of multi-systemic melioidosis that occurs in non-endemic regions in a patient who had no recent travel history. Hence, it is critical to enhance awareness of melioidosis in non-endemic regions.

Keywords: Melioidosis, Burkholderia pseudomallei, Endemic, Diabetes, Case report

Core Tip: This case describes a patient with no history of travel to melioidosis-endemic areas, who accidentally contracted Burkholderia pseudomallei (B. pseudomallei) due to trauma caused by a fall in a non-endemic area, leading to a multi-system melioidosis. This case is beneficial in enhancing the understanding of melioidosis, and suggests that B. pseudomallei could emerge in other non-endemic regions with climate change.

INTRODUCTION

Melioidosis is an endemic disease caused by Burkholderia pseudomallei (B. pseudomallei), which is mainly in tropical and sub-tropical areas, such as Southeast Asia, Northern Australia, and India, and is extremely rare in temperate regions[1-3]. B. pseudomallei is an environmental saprophyte found in soil, surface water, and groundwater[4]. Humans are likely infected through contaminated scratches and abrasions or the occasional aspiration of fresh water. Infections typically occur in the epidemic areas; sporadic cases are very rare, and melioidosis reported in other areas is essentially from imported cases of travelers or immigrants[5]. The most significant risk factors of melioidosis include diabetes, excessive alcohol use, chronic lung disease, chronic renal disease, thalassemia, immunosuppressive therapy, and cancer[6,7]. Melioidosis has been dubbed “the Great Imitator” given the absence of specific clinical features. Clinical and laboratory diagnoses of melioidosis are challenging[7,8]. Although melioidosis is a serious opportunistic infection, the mortality rate is very high[7,9,10]. Timely diagnosis and treatment are key to reducing the mortality rate.

Herein, we report the clinical details of a patient with multi-systemic melioidosis caused by B. pseudomallei in Wuhan, Hubei Province of China, which is a non-endemic region.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

The patient was admitted due to a 6-d history of fever.

History of present illness

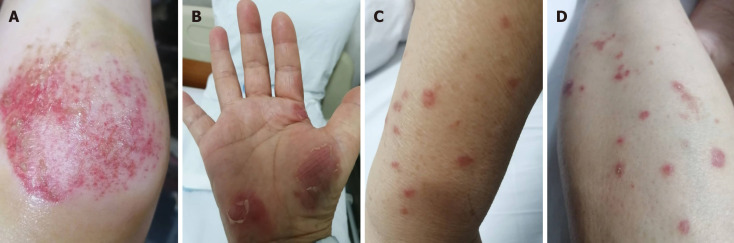

Twenty days after the incident, the patient experienced painful erythematous swelling of the bilateral lesser thenar and erythema on her limbs (Figure 1). She was diagnosed with undifferentiated connective tissue disease because of limb skin erythema, left knee joint pain, and positive Sjogren’s syndrome antigen B antibody. She began taking 30 mg prednisone daily for treatment. About 3 wk after prednisone therapy, the patient presented with chills, fever, headaches, frequent micturition, and other uncomfortable symptoms, with the highest temperature reaching 39.2 °C. Despite oral antibiotic therapy with 0.5 g amoxicillin (Amoxil) three times daily, the fever and headache did not subside.

Figure 1.

The patient developed dry asymmetric lesions on her limbs. A: Knee joint; B: Bilateral lesser thenar; C and D: Limbs.

History of past illness

She has had type 2 diabetes for more than 5 years, with no chronic kidney dysfunction or blood system diseases, among other conditions.

Physical examination

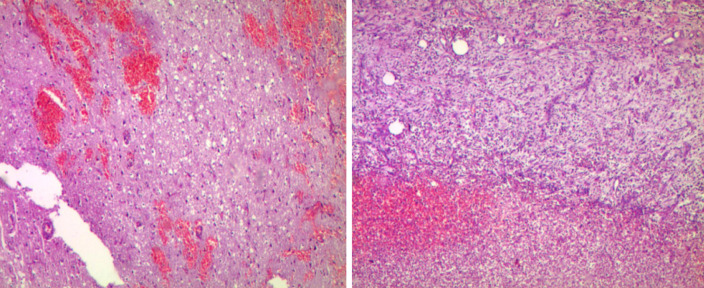

Upon examination, the patient was apyretic (body temperature: 36.5 °C), but generally unwell. The patient had a small erythematous patch with tenderness on the right forehead. Pathological examination revealed a frontal lobe abscess of brain (Figure 2). She was hemodynamically stable, and the results of her respiratory and cardiovascular examinations were perfectly normal. Her abdomen was soft, with no hepatosplenomegaly. She had scattered skin rashes on her limbs. The result of her neurological examination was normal.

Figure 2.

Pathological results of the patient’s frontal lobe brain abscess.

Laboratory examinations

Blood biochemistry revealed elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate and normal white cell count and neutrophils. However, the red and white blood cell counts were positive in urine sediment analysis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Laboratory test results of the patient

|

Laboratory parameters

|

Day 1

|

Day 10

|

Day 21

|

Day 30

|

Day 38

|

Normal range

|

| WBC (× 109/L) | 6.96 | 4.52 | 4.15 | 6.73 | 4.05 | 3.5-9.5 |

| Neutrophils (× 109/L) | 4.81 | 2.88 | 1.51 | 3.69 | 2.88 | 1.8-6.3 |

| RBC (× 1012/L) | 4.21 | 3.28 | 3.55 | 4.21 | 3.28 | 3.8-5.1 |

| Platelets (× 109/L) | 183.0 | 178.0 | 274.0 | 290.0 | 178.0 | 125-350 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 56.7 | 135.7 | 40.3 | 16.5 | 25.1 | 7-40 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 22.1 | 138 | 21.1 | 18.5 | 56.0 | 13-35 |

| Total protein (g/L) | 69.4 | 70.5 | 71.8 | 78.8 | 64.8 | 65-85 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 36.1 | 35.1 | 36.0 | 36.6 | 39.0 | 40-55 |

| Globulin (g/L) | 33.3 | 35.2 | 35.8 | 35.8 | 25.8 | 20-40 |

| Total bilirubin (μmol/L) | 9.70 | 8.35 | 7.88 | 12.86 | 5.7 | 0-21 |

| DBIL (μmol/L) | 3.90 | 3.94 | 2.80 | 3.76 | 3.0 | 0-8 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mmol/L) | 8.53 | 3.20 | 5.73 | 4.75 | 1.68 | 2.6-7.5 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 57.8 | 63.4 | 54.4 | 71 | 55.7 | 41-73 |

| Fasting blood glucose (mmol/L) | 9.5 | 4.8 | 7.6 | 7.2 | 7.9 | 3.7-6.1 |

| Creatine kinase (U/L) | 16 | - | - | 30 | - | 40-200 |

| Creatine kinase-MB (ng/mL) | 1.0 | - | - | 1.6 | - | 0-5 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 3.66 | 5.11 | 4.2 | 4.58 | 4.23 | 3.5-5.3 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 131.2 | 137.5 | 130.3 | 136.2 | 138.6 | 137-147 |

| Chloride (mmol/L) | 94.3 | 97.9 | 93.3 | 102.0 | 105. | 99-110 |

| Calcium (mmol/L) | 2.09 | 2.33 | 2.29 | 2.43 | 2.20 | 2.11-2.52 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 85.460 | 128.9 | 45.67 | 3.46 | - | 0-3 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 41 | 60 | 71 | 19 | - | 0-20 |

| Hemoglobin A1c (%) | 10.90 | - | - | - | 3-6.5 | |

| Urine WBC (cell/μL) | Positive | Negative | - | Negative | - | - |

| Urine RBC (cell/μL) | Positive | Negative | - | Negative | - | - |

CRP: C-reactive protein; DBIL: Direct bilirubin; ESR: Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; RBC: Red blood cell; WBC: White blood cell.

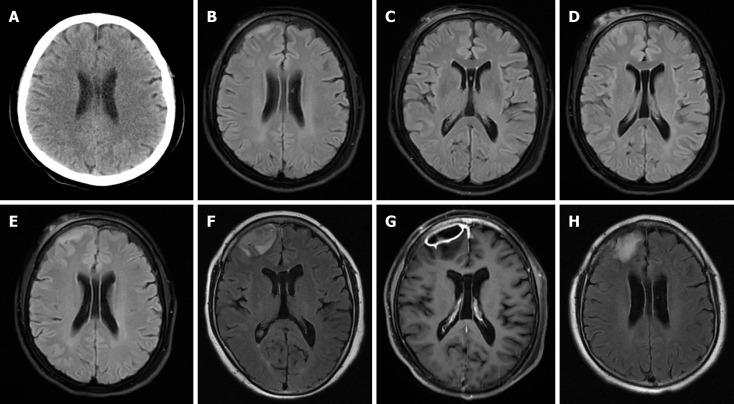

Imaging examinations

Head computed tomography (CT) measurements were normal (Figure 3A). Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a T2-weighted-fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (Figure 3B) signal that was slightly hyperintense, involving the right frontal region with a 7.6 mm × 33 mm strip, suggesting subdural hematoma. The right frontal skin showed swelling (Figure 3C). A second brain MRI was performed 1 wk after the first one and showed that the subdural hematoma and subcutaneous swelling at the right frontal region worsened (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The patient presented radiographic features of neurological melioidosis. A: Head computed tomography measurements were normal; B: Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) suggesting subdural hematoma; C: The right frontal skin showed swelling; D and E: A second brain MRI showed that the subdural hematoma and subcutaneous swelling at the right frontal region worsened; F: The third brain MRI showed an exacerbation of the subdural lesion in the right frontal lobe, with unclear demarcation between the lesion and the right frontal lobe, suggesting an intracranial infection; G: Enhanced MRI indicated the formation of a subdural abscess in the right frontal lobe; H: Two months post-surgery for an intracranial abscess, brain MRI showed gliosis at the surgical excision site.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Multi-systemic melioidosis; type 2 diabetes.

TREATMENT

Blood and urine cultures were performed on the 2nd day of admission. On the 3rd day of admission, the patient presented with sudden loss of consciousness and generalized seizure for a few seconds. The patient was diagnosed with epileptic seizure and treated with diazepam. On the 5th day of admission, blood and urine cultures revealed a gram-negative bacillus, B. pseudomallei, which is sensitive to ceftazidime, levofloxacin, cotrimoxazole, and meropenem. Ceftazidime (2 g every 8 h) was given according to the drug sensitivity test. The patient’s fever resolved, and the rashes gradually subsided after therapy. After 1 wk of ceftazidime treatment, the patient again developed high fever (highest recorded temperature: 39.0 °C). Ceftazidime was discontinued and replaced with meropenem. The patient was treated with incision and drainage of the subcutaneous abscess in the right frontal region (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Timeline of the case.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient showed no signs of relapse at the 4-month follow-up visit.

DISCUSSION

Melioidosis is regarded endemic to Southeast Asia and Northern Australia. In China, melioidosis often occurs in the southern areas, namely Hainan, Guangdong, Guangxi, and Fujian[11], and is very rare in other parts of China. Most of the sporadic cases reported in other parts of China are of patients with a travel history of endemic melioidosis. Although it is an endemic disease, melioidosis is a life-threatening disease caused by B. pseudomallei. Our patient presented multi-systemic involvement including the skin and soft tissue, genitourinary system, and central nervous system (CNS).

Cutaneous melioidosis (CM) has rarely been described compared with other systemic melioidosis[12]. CM may be a primary cutaneous infection or a disseminated secondary skin infection[13]. The common presentations of CM include ulcers, skin abscesses, single pustules, crusted erythematous lesions, and dry asymmetric erythematous flat lesions[13,14]. CM is often misdiagnosed as other diseases in non-endemic areas, because the skin manifestations and histologic results of CM are non-specific[15,16]. The dry asymmetric erythematous flat lesions in this patient were considered the main evidence for the diagnosis of undifferentiated tissue disease. The risk factors of melioidosis includes diabetes mellitus, excessive alcohol consumption, liver disease, chronic lung disease, chronic kidney disease, and steroid use[5,7,17-19]. Melioidosis patients with known diabetes have poor diabetic control and show a stunted B. pseudomallei-specific cellular response during acute illness compared with those without diabetes[20]. Uncontrolled blood sugar and steroid therapy are also important risk factors for the spread of melioidosis[19]. This patient showed typical melioidosis skin lesions such as painful erythematous swelling of the bilateral lesser thenar and erythema on the limbs, but the patient’s condition was aggravated by misdiagnosis, diabetes, and steroid therapy.

Genitourinary melioidosis is common, accounting for 3.2%-14% of all melioidosis cases[7,21]. Genitourinary melioidosis occurs more frequently in male patients with complications such as prostatitis, prostatic abscess, renal abscess, epididymo-orchitis, and sepsis[7,22]. The clinical manifestations are mainly urinary frequency, dysuria, urinary retention, and swelling of the scrotum[22,23], and some patients may present septic shock[24]. Many white and red blood cells can be observed in urine[25]. Genitourinary melioidosis can be ruled out if the patient has no urinary symptoms or a negative urine test[26]. This patient also presented with urinary frequency and white and red blood cells in the urinalysis.

Neurological melioidosis is rare but has a high mortality rate[27,28]. In a patient series of 540 melioidosis, neuro-melioidosis accounts for only 3%-5%, but accounts for 21% of mortalities[7]. The neurological manifestations of melioidosis often include meningoencephalitis, myelitis, and spinal epidural abscess but rarely brain abscess[29,30]. Although the radiographic features of neurological melioidosis are not specific, CNS imaging is essential for locating lesions and identifying those that can be treated with surgery or biopsy so that appropriate treatment can be initiated in a timely manner[31,32]. In this case, head CT presented no abnormalities, and cerebral hemorrhage was misdiagnosed on head MRI. However, the subsequent head MRI revealed the progression of melioidosis and recorded the evolution of the patient’s intracranial abscess. MRI is more sensitive for diagnosing neurological melioidosis than CT[33]. Therefore, serial head MRI is one of the important methods of diagnosing neurological melioidosis.

The isolation of B. pseudomallei from clinical specimens is the gold standard for the diagnosis of melioidosis. However, B. pseudomallei can be easily thought of as a contaminant or confused with other bacteria[5], resulting in the misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis of melioidosis. Blood cultures are the most important, but the positive rate of B. pseudomallei is only 50%-70% in blood culture[34,35]. In one series, only 29% of the brain tissue or 19% of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples were culture-positive[29]. B. pseudomallei was isolated from the samples of this patient’s blood, urine, and right frontal subcutaneous abscesses, but not from CSF and intracranial abscess samples.

The laboratory markers associated with poor prognosis include leucopenia (especially lymphopenia), a normal or only slightly raised CRP, raised transaminases, bilirubin, urea, and creatinine, hypoglycemia, and acidosis[36,37]. CRP estimations may be helpful in ascertaining active infection in patients with low serum levels of specific immunoglobulin M antibody[38]; however, a normal level of CRP cannot be used to exclude acute, chronic, or relapsed melioidosis in febrile patients in endemic regions[39]. In this case, the level of CRP gradually decreased with the improvement of the patient’s disease, and no serious increase in transaminases, bilirubin, and creatinine was noted. Because melioidosis is a serious threat to patients’ health, the patient should immediately begin treatment instead of waiting until the culture results. The treatment of melioidosis consists of an intensive phase of at least 10-14 d of intravenous administration of ceftazidime, meropenem, or imipenem, followed by oral eradication therapy, usually with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for 3-6 months[40,41]. Attention should also be paid to the risks of long-term antibiotic treatment. B. pseudomallei is resistant to penicillin, ampicillin, first-generation and second-generation cephalosporins, gentamicin, tobramycin, streptomycin, macrolides, and polymyxins[42,43], Thus, no therapeutic effect was noted when the patient first took amoxicillin. This patient was initially given ceftazidime according to the susceptibility testing upon admission, which was switched to meropenem because of fever during treatment with ceftazidime. The failure of ceftazidime treatment may be related to suppression of the immune system by steroid therapy and poor blood glucose control. Festic et al[44] showed that glucocorticosteroids impact biofilm formation and antibiotic tolerance. Physicians who are unfamiliar with the treatment of melioidosis should follow the course of treatment recommended by the guidelines[45,46]. Although antibiotics are preferred for the treatment of multiple intracranial abscesses in melioidosis[47]. Adjunctive abscess drainage was performed in 58% cases. After treatment, 37% patients with CNS melioidosis recovered completely or nearly completely, 31% had moderate neurological improvement, while 13% did not recover and suffered neurological disability[48]. In our patient, the intracranial abscess gradually increased during the course of antibiotic treatment, so intracranial abscess drainage was performed, resulting in no further adverse neurological prognosis.

CONCLUSION

We present here a rare case of multi-systemic melioidosis in a female patient without a travel history in a non-endemic area. In this case, cutaneous and genitourinary melioidosis infection as well as intracranial melioidosis infection occurred. For melioidosis with poor response to antibiotics, the aggravation of infection leads to intracranial abscess for which abscess excision and drainage are an effective measure. We believe that this report will help improve the traditional understanding of melioidosis among the medical staff in non-endemic areas and provide an account of the clinical experience for the diagnosis and treatment of multi-systemic melioidosis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to the patient for graciously providing consent to share her case in this publication. Additionally, we extend our heartfelt thanks to neurosurgeon Dr. Pan Derui for his invaluable contribution to the manuscript of this article.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: The patient provided written informed consent to participate in this study.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors have no conflicts of interests to declare.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: November 8, 2023

First decision: December 12, 2023

Article in press: February 25, 2024

Specialty type: Infectious diseases

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D, D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ebrahimifar M, Iran; Mandal P, India S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Xu ZH

Contributor Information

Huan-Yu Ni, Department of Endocrinology, Puren Hospital, Wuhan University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430080, Hubei Province, China; School of Medicine, Wuhan University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430080, Hubei Province, China.

Ying Zhang, Department of Critical Care Medicine, Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan 430071, Hubei Province, China.

Dong-Hai Huang, Department of Rheumatology and Immunology, Puren Hospital, Wuhan University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430080, Hubei Province, China.

Feng Zhou, Department of Endocrinology, Puren Hospital, Wuhan University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430080, Hubei Province, China. przhoufeng@sina.com.

References

- 1.Currie BJ, Dance DA, Cheng AC. The global distribution of Burkholderia pseudomallei and melioidosis: an update. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102 Suppl 1:S1–S4. doi: 10.1016/S0035-9203(08)70002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Limmathurotsakul D, Golding N, Dance DA, Messina JP, Pigott DM, Moyes CL, Rolim DB, Bertherat E, Day NP, Peacock SJ, Hay SI. Predicted global distribution of Burkholderia pseudomallei and burden of melioidosis. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1 doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2015.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang S. Melioidosis research in China. Acta Trop. 2000;77:157–165. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(00)00139-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gassiep I, Armstrong M, Norton R. Human Melioidosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2020;33 doi: 10.1128/CMR.00006-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiersinga WJ, Virk HS, Torres AG, Currie BJ, Peacock SJ, Dance DAB, Limmathurotsakul D. Melioidosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:17107. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malczewski AB, Oman KM, Norton RE, Ketheesan N. Clinical presentation of melioidosis in Queensland, Australia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2005;99:856–860. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Currie BJ, Ward L, Cheng AC. The epidemiology and clinical spectrum of melioidosis: 540 cases from the 20 year Darwin prospective study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e900. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Currie BJ, Fisher DA, Howard DM, Burrow JN, Lo D, Selva-Nayagam S, Anstey NM, Huffam SE, Snelling PL, Marks PJ, Stephens DP, Lum GD, Jacups SP, Krause VL. Endemic melioidosis in tropical northern Australia: a 10-year prospective study and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:981–986. doi: 10.1086/318116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dance D. Treatment and prophylaxis of melioidosis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2014;43:310–318. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlson P, Seppänen M. Melioidosis presenting as urinary tract infection in a previously healthy tourist. Scand J Infect Dis. 2000;32:92–93. doi: 10.1080/00365540050164308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng X, Xia Q, Xia L, Li W. Endemic Melioidosis in Southern China: Past and Present. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2019;4 doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed4010039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng AC, Currie BJ. Melioidosis: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:383–416. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.2.383-416.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibney KB, Cheng AC, Currie BJ. Cutaneous melioidosis in the tropical top end of Australia: a prospective study and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:603–609. doi: 10.1086/590931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuijpers SC, Klouwens M, de Jong KH, Langeslag JCP, Kuipers S, Reubsaet FAG, van Leeuwen EMM, de Bree GJ, Hovius JW, Grobusch MP. Primary cutaneous melioidosis acquired in Nepal - Case report and literature review. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2021;42:102080. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2021.102080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ngauy V, Lemeshev Y, Sadkowski L, Crawford G. Cutaneous melioidosis in a man who was taken as a prisoner of war by the Japanese during World War II. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:970–972. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.2.970-972.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thng TG, Seow CS, Tan HH, Yosipovitch G. A case of nonfatal cutaneous melioidosis. Cutis. 2003;72:310–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang YS, Wong CH, Kurup A. Cutaneous melioidosis and necrotizing fasciitis caused by Burkholderia pseudomallei. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:1484–1485. doi: 10.3201/eid0911.030370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deris ZZ, Hasan H, Siti Suraiya MN. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of bacteraemic melioidosis in a teaching hospital in a northeastern state of Malaysia: a five-year review. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2010;4:430–435. doi: 10.3855/jidc.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.So SY, Chau PY, Leung YK, Lam WK, Yu DY. Successful treatment of melioidosis caused by a multiresistant strain in an immunocompromised host with third generation cephalosporins. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;127:650–654. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1983.127.5.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jenjaroen K, Chumseng S, Sumonwiriya M, Ariyaprasert P, Chantratita N, Sunyakumthorn P, Hongsuwan M, Wuthiekanun V, Fletcher HA, Teparrukkul P, Limmathurotsakul D, Day NP, Dunachie SJ. T-Cell Responses Are Associated with Survival in Acute Melioidosis Patients. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0004152. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zueter A, Yean CY, Abumarzouq M, Rahman ZA, Deris ZZ, Harun A. The epidemiology and clinical spectrum of melioidosis in a teaching hospital in a North-Eastern state of Malaysia: a fifteen-year review. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:333. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1583-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chong Vh VH, Sharif F, Bickle I. Urogenital melioidosis: a review of clinical presentations, characteristic and outcomes. Med J Malaysia. 2014;69:257–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morse LP, Moller CC, Harvey E, Ward L, Cheng AC, Carson PJ, Currie BJ. Prostatic abscess due to Burkholderia pseudomallei: 81 cases from a 19-year prospective melioidosis study. J Urol. 2009;182:542–7; discussion 547. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koshy M, Sadanshiv P, Sathyendra S. Genitourinary melioidosis: a descriptive study. Trop Doct. 2019;49:104–107. doi: 10.1177/0049475518817416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rahim MA, Samad T, Ananna MA, Ul Haque WMM. Genitourinary melioidosis in a Bangladeshi farmer with IgA nephropathy complicated by steroid-induced diabetes mellitus. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2018;29:709–713. doi: 10.4103/1319-2442.235205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kozlowska J, Smith S, Roberts J, Pridgeon S, Hanson J. Prostatic Abscess due to Burkholderia pseudomallei: Facilitating Diagnosis to Optimize Management. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;98:227–230. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khiangte HL, Robinson Vimala L, Veeraraghavan B, Yesudhason BL, Karuppusami R. Can the imaging manifestations of melioidosis prognosticate the clinical outcome? A 6-year retrospective study. Insights Imaging. 2019;10:17. doi: 10.1186/s13244-019-0708-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hsu CC, Singh D, Kwan G, Deuble M, Aquilina C, Korah I, Norton R. Neuromelioidosis: Craniospinal MRI Findings in Burkholderia pseudomallei Infection. J Neuroimaging. 2016;26:75–82. doi: 10.1111/jon.12282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deuble M, Aquilina C, Norton R. Neurologic melioidosis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89:535–539. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.12-0559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muthusamy KA, Waran V, Puthucheary SD. Spectra of central nervous system melioidosis. J Clin Neurosci. 2007;14:1213–1215. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2006.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mannam P, Arvind VH, Koshy M, Varghese GM, Alexander M, Elizabeth SM. Neuromelioidosis: A Single-Center Experience with Emphasis on Imaging. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2021;31:57–64. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1729125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hadano Y. Imported melioidosis in Japan: a review of cases. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;11:163–168. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S154696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lim KS, Chong VH. Radiological manifestations of melioidosis. Clin Radiol. 2010;65:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wongwandee M, Linasmita P. Central nervous system melioidosis: A systematic review of individual participant data of case reports and case series. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007320. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Limmathurotsakul D, Jamsen K, Arayawichanont A, Simpson JA, White LJ, Lee SJ, Wuthiekanun V, Chantratita N, Cheng A, Day NP, Verzilli C, Peacock SJ. Defining the true sensitivity of culture for the diagnosis of melioidosis using Bayesian latent class models. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12485. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mukhopadhyay C, Chawla K, Vandana KE, Krishna S, Saravu K. Pulmonary melioidosis in febrile neutropenia: the rare and deadly duet. Trop Doct. 2010;40:165–166. doi: 10.1258/td.2010.090461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gulati U, Nanduri AC, Juneja P, Kaufman D, Elrod MG, Kolton CB, Gee JE, Garafalo K, Blaney DD. Case Report: A Fatal Case of Latent Melioidosis Activated by COVID-19. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2022;106:1170–1172. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.21-0689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ashdown LR. Serial serum C-reactive protein levels as an aid to the management of melioidosis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;46:151–157. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.46.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheng AC, Obrien M, Jacups SP, Anstey NM, Currie BJ. C-reactive protein in the diagnosis of melioidosis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;70:580–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wiersinga WJ, Currie BJ, Peacock SJ. Melioidosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1035–1044. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1204699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lipsitz R, Garges S, Aurigemma R, Baccam P, Blaney DD, Cheng AC, Currie BJ, Dance D, Gee JE, Larsen J, Limmathurotsakul D, Morrow MG, Norton R, O'Mara E, Peacock SJ, Pesik N, Rogers LP, Schweizer HP, Steinmetz I, Tan G, Tan P, Wiersinga WJ, Wuthiekanun V, Smith TL. Workshop on treatment of and postexposure prophylaxis for Burkholderia pseudomallei and B. mallei Infection, 2010. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:e2. doi: 10.3201/eid1812.120638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rhodes KA, Schweizer HP. Antibiotic resistance in Burkholderia species. Drug Resist Updat. 2016;28:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bugrysheva JV, Sue D, Gee JE, Elrod MG, Hoffmaster AR, Randall LB, Chirakul S, Tuanyok A, Schweizer HP, Weigel LM. Antibiotic Resistance Markers in Burkholderia pseudomallei Strain Bp1651 Identified by Genome Sequence Analysis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61 doi: 10.1128/AAC.00010-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Festic E, Scanlon PD. Incident pneumonia and mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A double effect of inhaled corticosteroids? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:141–148. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201409-1654PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sullivan RP, Marshall CS, Anstey NM, Ward L, Currie BJ. 2020 Review and revision of the 2015 Darwin melioidosis treatment guideline; paradigm drift not shift. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14:e0008659. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Becattini S, Taur Y, Pamer EG. Antibiotic-Induced Changes in the Intestinal Microbiota and Disease. Trends Mol Med. 2016;22:458–478. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muthina RA, Koppara NK, Bethasaida Manuel M, Bommu AN, Anapalli SR, Boju SL, Rapur R, Vishnubotla SK. Cerebral abscess and calvarial osteomyelitis caused by Burkholderia pseudomallei in a renal transplant recipient. Transpl Infect Dis. 2021;23:e13530. doi: 10.1111/tid.13530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hesstvedt L, Reikvam DH, Dunlop O. Neurological melioidosis in Norway presenting with a cerebral abscess. IDCases. 2015;2:16–18. doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]