Abstract

BACKGROUND

Although chronic erosive gastritis (CEG) is common, its clinical characteristics have not been fully elucidated. The lack of consensus regarding its treatment has resulted in varied treatment regimens.

AIM

To explore the clinical characteristics, treatment patterns, and short-term outcomes in CEG patients in China.

METHODS

We recruited patients with chronic non-atrophic or mild-to-moderate atrophic gastritis with erosion based on endoscopy and pathology. Patients and treating physicians completed a questionnaire regarding history, endoscopic findings, and treatment plans as well as a follow-up questionnaire to investigate changes in symptoms after 4 wk of treatment.

RESULTS

Three thousand five hundred sixty-three patients from 42 centers across 24 cities in China were included. Epigastric pain (68.0%), abdominal distension (62.6%), and postprandial fullness (47.5%) were the most common presenting symptoms. Gastritis was classified as chronic non-atrophic in 69.9% of patients. Among those with erosive lesions, 72.1% of patients had lesions in the antrum, 51.0% had multiple lesions, and 67.3% had superficial flat lesions. In patients with epigastric pain, the combination of a mucosal protective agent (MPA) and proton pump inhibitor was more effective. For those with postprandial fullness, acid regurgitation, early satiety, or nausea, a MPA appeared more promising.

CONCLUSION

CEG is a multifactorial disease which is common in Asian patients and has non-specific symptoms. Gastroscopy may play a major role in its detection and diagnosis. Treatment should be individualized based on symptom profile.

Keywords: Chronic erosive gastritis, Symptom, Endoscopic findings, Treatment pattern, Real-world

Core Tip: This multicenter study is the first real-world observational study to explore lifestyle characteristics, symptoms, endoscopic findings, treatment patterns, and short-term outcomes in patients with chronic erosive gastritis in China. Our findings suggest that it is a multifactorial disease influenced by lifestyle, obesity, infection, emotion, and mood. Epigastric pain, abdominal distension, and postprandial fullness were the most common initial symptoms, which are non-specific. Therefore, gastroscopy may be valuable for detection and diagnosis. Individualized treatment based on symptom profile is crucial.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic gastritis is a common illness that affects billions of individuals worldwide[1,2]. Among the different types, chronic erosive gastritis (CEG) is the most common. In 2014, the Chinese Chronic Gastritis Research group conducted a nationwide multicenter study that enrolled 8892 patients with chronic gastritis from 33 centers across 10 cities; 49.4% of patients were diagnosed with superficial gastritis and 42.3% with erosive gastritis, which indicated that chronic superficial gastritis and CEG are the most common endoscopic findings in Chinese patients[3]. Although CEG does not carry a risk of cancer, it causes histological changes in the gastric mucosa and various gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms that may result in decreased quality of life.

According to the Sydney System for the classification of gastritis, chronic gastritis can be divided into non-atrophic and atrophic types based on endoscopic and pathological evaluations[4]. The topographical patterns of chronic gastritis range from antrum-predominant to corpus-predominant gastritis or pangastritis[5]. Erosive gastritis is defined as any type of gastritis accompanied by erosions in the mucosa, which are identified as either flat or minimally depressed white spots surrounded by a reddish area that may be accompanied by superficial bleeding or small nodules with central umbilication that mimics octopus suckers[6]. In general, erosive gastritis involves inflammatory mucosal damage that can lead to ulceration or bleeding[7,8]. Although gastric carcinogenesis and peptic ulcers have attracted considerable research attention over the past decade, few studies have focused on CEG.

Whether the pathogenesis of erosive gastritis involves elevated production of gastric acid or is related to weakened mucosal defenses has been debated for decades[6,9]. Although Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection[1,10], stress[11], and obesity[7] are potentially correlated with CEG incidence, further evidence is needed. Furthermore, the impact of medications such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and warfarin on CEG remains unclear[12,13]. CEG risk factors, presentation, endoscopic and histopathological findings, therapeutic options, and treatment effects remain largely controversial. As a result, treatment practices vary. This study was conducted to aid in understanding the clinical and lifestyle characteristics, treatment patterns, and short-term outcomes of CEG in Chinese patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient selection

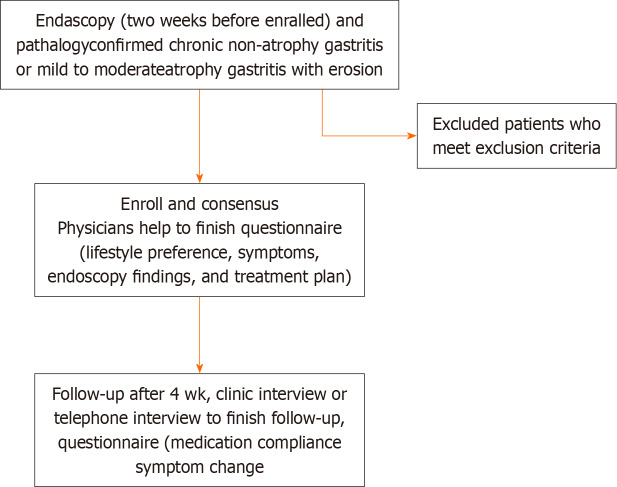

This real-world, multicenter, prospective, observational cohort study was conducted in 42 participating centers in 24 cities in China from April 2019 to December 2019. The study flow chart is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart.

Patients aged 18 to 70 years with a diagnosis of chronic non-atrophic or mild-to-moderate atrophic gastritis with erosions based on both endoscopic and pathological evaluations were eligible for inclusion. We excluded patients with any of the following criteria: (1) Chronic atrophic gastritis with intraepithelial neoplasia; (2) other mucosal lesions, such as gastric ulcers; (3) diagnosis of dementia, delirium, severe mood disturbance, or other mental disorder; (4) diagnosis of severe cardiac or cerebrovascular disease; (5) malignancy that required ongoing treatment; (6) history of subtotal gastrectomy; (7) history of previous endoscopic procedure such as endoscopic submucosal dissection or endoscopic mucosal resection; (8) pregnancy; or (9) any other condition that was considered unsuitable for the study. Erosive gastritis was determined by endoscopy according to the Sydney System and 2017 Chinese consensus on chronic gastritis[14]. All patients provided written informed consent. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committees of all participating institutions (Clinical registration number: ChiCTR2100047690).

Study design

Patients were asked to complete the first part of a baseline questionnaire, which contained questions regarding lifestyle, other medical conditions, medications, and major GI symptoms and their severity, with the help of physicians. Each symptom was graded as 0 (non-existent), 1 (mild and occasional), 2 (obvious and frequent, partially disturbing daily life), or 3 (severe, disturbing daily life). Physicians then independently completed the second part of the questionnaire, which contained information regarding endoscopy findings and treatment. Four weeks later, patients completed a follow-up questionnaire, which contained questions regarding medication compliance and major GI symptoms and their severity with the help of medical assistants, either in the clinic or by telephone interview.

Clinical effect evaluation

The severity of symptoms was scored at the time of enrollment and during follow-up. Symptoms included epigastric pain, abdominal distension, postprandial fullness, early satiety, acid regurgitation, nausea, belching, vomiting, and others. Clinical effectiveness of treatment was defined as a decrease in symptom score. Participants were categorized into four groups according to treatment strategy: Mucosal protective agent (MPA), proton pump inhibitor (PPI), MPA + PPI, and MPA + PPI + prokinetic drug (PD).

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are presented as absolute values with relative frequencies. Comparisons of categorical variables were performed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs) were calculated using logistic regression and adjusted for age and sex. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States). All tests were two-sided. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Physician characteristics

A total of 111 physicians were randomly selected from a panel of gastroenterologists from the participating centers. Sixty-one (55.0%) were men and fifty (45.0%) were women. The demographic distribution of each participating center is shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

Patient characteristics

The data of 3563 patients were included for analysis. Patient demographics are shown in Supplementary Figure 1. Patients aged between 40 and 60 years comprised 52.7% of the patients and 49.5% were men. Few patients reported comorbidities, although 310 (8.7%) had a family history of malignancy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics, n (%)

|

Variable

|

n = 3563

|

| I Baseline characteristics | |

| Age group at enrollment (yr) | |

| 0-20 | 53 (1.5) |

| 21-30 | 321 (9.0) |

| 31-40 | 617 (17.3) |

| 41-50 | 920 (25.8) |

| 51-60 | 959 (26.9) |

| > 60 | 693 (19.4) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 1765 (49.5) |

| Female | 1798 (50.5) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Bile reflux | 343 (9.6) |

| Liver disease or cirrhosis | 137 (3.8) |

| Pancreatic disease | 58 (1.6) |

| Autoimmune disease | 13 (0.4) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 52 (1.5) |

| Post GI surgery | 61 (1.7) |

| Family history of malignancy | 310 (8.7) |

| Gastric carcinoma | 185 (5.2) |

| Other malignancy | 125 (3.5) |

| II Lifestyle | |

| Alcohol use history | |

| Never | 1784 (50.1) |

| Former user | 163 (4.6) |

| Less than 1 d per week | 955 (26.8) |

| 1-2 d per week | 288 (8.1) |

| 3-6 d per week | 206 (5.8) |

| everyday | 167 (4.7) |

| Smoking history | |

| Never | 2357 (66.2) |

| Former smoker | 157 (4.4) |

| Less than 1 pack per week | 229 (6.4) |

| 1-2 packs per week | 277 (7.8) |

| 3-6 packs per week | 236 (6.6) |

| More than 1 pack per day | 307 (8.6) |

| Diet regularity | |

| Regular | 2352 (66.0) |

| Irregular in 1-2 d per week | 617 (17.3) |

| Irregular in 3-6 d per week | 285 (8.0) |

| Irregular everyday | 309 (8.7) |

| Coffee intake | |

| Never | 2486 (69.8) |

| Less than 1 d per week | 633 (17.8) |

| 1-2 d per week | 178 (5.0) |

| 3-6 d per week | 130 (3.6) |

| Everyday | 136 (3.8) |

| Diet preference (multiple choices) | |

| Normal | 1477 (41.5) |

| Healthy diet (vegetable dominate) | 904 (25.4) |

| Spicy food | 841 (23.6) |

| Smoked or pickled food | 527 (14.8) |

| Hot food | 386 (10.8) |

| Sleep duration | |

| ≥ 7 h per day on average | 1680 (47.1) |

| < 7 h per day on average | 1883 (52.8) |

| Sleep regularity | |

| Regular | 2391 (67.1) |

| Irregular | 1172 (32.8) |

| III Medication | |

| NSAIDs | 295 (8.3) |

| Anticoagulation drugs | 164 (4.6) |

| Corticosteroids | 73 (2.0) |

| IV Stress and mood | |

| Feeling stressed | 974 (27.3) |

| Major life events | 386 (10.8) |

| Feeling depressed | 865 (24.3) |

| Feeling anxious | 1138 (31.9) |

GI: Gastrointestinal; NSAIDs: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Lifestyle

Two-thirds of patients (66.2%) had no history of smoking; 29.4% and 4.4% were current or former smokers, respectively. Half (50.1%) had no history of alcohol consumption, whereas 45.3% and 4.6% were current or former drinkers, respectively. Regarding dietary habits, 66% of patients ate a regular diet and 69.8% never drank coffee. Detailed dietary preferences are shown in Table 1. Almost half of patients (47.1%) slept ≥ 7 h per night on average and 32.8% reported irregular sleep (Table 1).

Medication

NSAIDs were the most commonly used medication (8.3%). Anticoagulation drugs and corticosteroids were used by 4.6% and 2.0% of patients, respectively (Table 1).

Stress and mood

A relatively high proportion of patients reported stress or mood issues: 27.3% of patients felt stressed, 10.8% of patients underwent major life events in the previous 6 months, 24.3% of patients felt depressed, and 31.9% suffered from anxiety (Table 1).

H. pylori infection

Among the 2922 patients who underwent H. pylori testing, 24.8% were positive (Table 1).

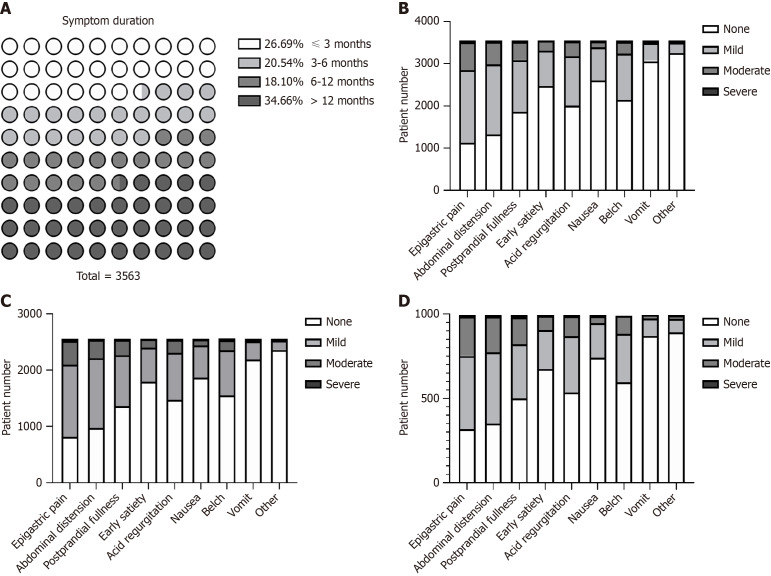

Initial symptoms and endoscopic findings

Data regarding initial symptoms and endoscopic findings were collected through history taking and gastroscopic reports. Eight major symptoms and their severity were evaluated. Symptom duration varied: 26.7% of patients had symptoms for less than 3 months and 34.7% had symptoms for more than 1 year (Figure 2A). The most common symptoms were epigastric pain, abdominal distension, and postprandial fullness. Symptoms and their severity were similar between non-atrophic gastritis patients and all patients (Figure 2, Supplementary Figure 2, Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Among patients with erosions, 72.0% were diagnosed with chronic non-atrophic gastritis, 22.5% with chronic mild atrophic gastritis, and 5.5% with chronic moderate atrophic gastritis. Most patients had erosions in the gastric antrum. Slightly more than half (51.0%) had a single lesion and 67.3% had superficial flat lesions (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Initial symptoms and their severity. A: Symptom duration for all patients; B: Distribution of initial symptoms in all patients with gastritis; C: Distribution of symptoms innon-atrophic gastritis patients; D: Distribution of symptoms in atrophic gastritis patients.

Table 2.

Endoscopic findings, n (%)

|

Variable

|

n = 3563

|

| Gastritis classification | |

| Chronic non-atrophy gastritis | 2489 (69.9) |

| Chronic mild-atrophy gastritis | 819 (23.0) |

| Chronic moderate-atrophy gastritis | 255 (7.1) |

| Topographical pattern of erosion | |

| Fundus involvement | 498 (14.0) |

| Corpus involvement | 642 (18.0) |

| Antrum involvement | 2568 (72.1) |

| Angle involvement | 154 (4.3) |

| Location involvement | |

| Single | 3292 (92.4) |

| Multiple | 271 (7.6) |

| Erosive lesion number | |

| Single lesion | 1747 (49.0) |

| Multiple lesions | 1816 (51.0) |

| Erosive lesion morphology | |

| Superficial flat | 2399 (67.3) |

| Protrude nodules | 1164 (32.7) |

Treatment patterns and efficacy

Treatment patterns are shown in Table 3. Lifestyle instructions without medication were prescribed in 10.3% of patients; 89% received a drug or drug combination. The most frequently used regimens were MPA + PPI (35.24%), MPA (12.27%), PPI (10.17%), and MPA + PPI + PD (9.45%). The effectiveness of these four treatment regimens against each symptom is shown in Table 4. Table 5 shows the same with patients stratified according to H. pylori status. Treatment effectiveness was generally lower in H. pylori-positive patients. Effectiveness was higher in the MPA group than the PPI group for postprandial fullness (48.7% vs 32.6%), early satiety (36.7% vs 18.2%), nausea (34.4% vs 18.8%), and epigastric pain (55.9% vs 47.7%). Effectiveness was higher in the PPI + MPA group than the PPI group for epigastric pain (66.7% vs 47.7%) and acid regurgitation (41.4% vs 31.4%). For abdominal distension and belching, effectiveness was highest in the PPI + MPA + PD group. Comparisons between groups after adjusting for sex and age are shown in Table 6.

Table 3.

Treatment patterns of chronic erosive gastritis, n (%)

|

Variable

|

n = 3563

|

Variable

|

n = 3563

|

| Treatment patterns | |||

| Only lifestyle instructions | 368 (10.3) | ||

| Drug combinations | Drug by category | ||

| MPA + PPI | 1126 (31.6) | MPA | 2380 (66.8) |

| MPA | 392 (11.0) | PPI | 2489 (69.9) |

| PPI | 325 (9.1) | Anti-Hp | 404 (11.3) |

| MPA + PPI + PD | 302 (8.5) | H2RA | 23 (0.6) |

| PPI + anti-Hp | 161 (4.5) | PD | 608 (17.1) |

| MPA + PPI + anti-Hp | 151 (4.2) | TCM | 250 (7.0) |

| MPA + PD | 92 (2.6) | Others | 260 (7.3) |

| MPA + PPI + TCM | 65 (1.8) | ||

| PPI + PD | 51 (1.4) | ||

| PPI + TCM | 42 (1.2) | ||

| Others | 488 (13.7) |

MPA: Mucosal protective agent; PPI: Proton pump inhibitor; PD: Prokinetic drug; Hp: Helicobacter pylori; TCM: Traditional Chinese medicine; H2RA: Histamine-2 receptor antagonist.

Table 4.

Effectiveness of the four most frequently used treatment regimens against the various symptoms, n (%)

|

|

MPA effectiveness, n = 3563

|

PPI effectiveness, n = 3563

|

MPA + PPI effectiveness, n = 3563

|

MPA + PPI + PD effectiveness, n = 3563

|

P value

|

| Epigastric pain | 219 (55.9) | 155 (47.7) | 751 (66.7) | 207 (68.5) | < 0.001 |

| Abdominal distension | 212 (54.1) | 158 (48.6) | 608 (54.0) | 194 (64.2) | 0.001 |

| Postprandial fullness | 191 (48.7) | 106 (32.6) | 455 (40.4) | 156 (51.7) | < 0.001 |

| Early satiety | 144 (36.7) | 59 (18.2) | 309 (27.4) | 103 (34.1) | < 0.001 |

| Acid regurgitation | 159 (40.6) | 102 (31.4) | 466 (41.4) | 164 (54.3) | < 0.001 |

| Nausea | 135 (34.4) | 61 (18.8) | 261 (23.2) | 86 (28.5) | < 0.001 |

| Belch | 168 (42.9) | 88 (27.1) | 355 (31.5) | 152 (50.3) | < 0.001 |

| Vomiting | 87 (22.2) | 38 (11.7) | 140 (12.4) | 43 (14.2) | < 0.001 |

| Others | 72 (18.4) | 14 (4.3) | 42 (3.7) | 21 (7.0) | < 0.001 |

MPA: Mucosal protective agent; PPI: Proton pump inhibitor; PD: Prokinetic drug.

Table 5.

Treatment effectiveness with patients stratified according to Helicobacter pylori status, n (%)

|

MPA effectiveness, n = 3563

|

PPI effectiveness, n = 3563

|

MPA + PPI effectiveness, n = 3563

|

MPA + PPI + PD effectiveness, n = 3563

|

P value | |||||

|

Hp (+)

|

Hp (-)

|

Hp (+)

|

Hp (-)

|

Hp (+)

|

Hp (-)

|

Hp (+)

|

Hp (-)

|

||

| Epigastric pain | 26 (47.3) | 148 (56.5) | 27 (51.9) | 86 (42.8) | 91 (67.9) | 527 (66.5) | 10 (47.6) | 161 (70.3) | 0 |

| Abdominal distension | 24 (43.6) | 143 (54.6) | 29 (55.8) | 99 (49.3) | 74 (55.2) | 424 (53.5) | 15 (71.4) | 141 (61.6) | 0.092 |

| Postprandial fullness | 21 (38.2) | 135 (51.5) | 22 (42.3) | 63 (31.3) | 55 (41.0) | 323 (40.7) | 8 (38.1) | 118 (51.5) | 0 |

| Early satiety | 19 (34.5) | 102 (38.9) | 15 (28.8) | 31 (15.4) | 36 (26.9) | 230 (29.0) | 6 (28.6) | 83 (36.2) | 0 |

| Acid regurgitation | 29 (52.7) | 102 (38.9) | 25 (48.1) | 61 (30.3) | 38 (28.4) | 340 (42.9) | 10 (47.6) | 127 (55.5) | 0 |

| Nausea | 24 (43.6) | 88 (33.6) | 15 (28.8) | 36 (17.9) | 28 (20.9) | 190 (24.0) | 2 (9.5) | 73 (31.9) | 0 |

| Belch | 28 (50.9) | 115 (43.9) | 21 (40.4) | 50 (24.9) | 37 (27.6) | 259 (32.7) | 4 (19.0) | 118 (51.5) | 0 |

| Vomiting | 16 (29.1) | 54 (20.6) | 11 (21.2) | 18 (9.0) | 17 (12.7) | 103 (13.0) | 1 (4.8) | 38 (16.6) | 0 |

| Others | 21 (38.2) | 135 (51.5) | 22 (42.3) | 63 (31.3) | 55 (41.0) | 323 (40.7) | 8 (38.1) | 118 (51.5) | 0 |

MPA: Mucosal protective agent; PPI: Proton pump inhibitor; PD: Prokinetic drug; Hp: Helicobacter pylori.

Table 6.

Treatment response comparisons (n = 3563)

|

PPI vs MPA

|

PPI vs MPA + PPI

|

PPI vs MPA + PPI + PD

|

||||

|

OR (95%WCL)

|

P value

|

OR (95%WCL)

|

P value

|

OR (95%WCL)

|

P value

|

|

| Epigastric pain | 0.73 (0.54-0.98) | 0.039 | 0.46 (0.36-0.59) | < 0.001 | 0.42 (0.30-0.58) | < 0.001 |

| Abdominal distension | 0.81 (0.60-1.09) | 0.162 | 0.81 (0.63-1.04) | 0.091 | 0.53 (0.38-0.73) | < 0.001 |

| Postprandial fullness | 0.51 (0.38-0.69) | < 0.001 | 0.71 (0.55-0.93) | 0.011 | 0.45 (0.33-0.62) | < 0.001 |

| Early satiety | 0.38 (0.27-0.54) | < 0.001 | 0.59 (0.43-0.80) | < 0.001 | 0.42 (0.29-0.61) | < 0.001 |

| Acid regurgitation | 0.68 (0.50-0.93) | 0.016 | 0.65 (0.50-0.85) | 0.001 | 0.38 (0.28-0.53) | < 0.001 |

| Nausea | 0.44 (0.31-0.63) | < 0.001 | 0.77 (0.57-1.06) | 0.106 | 0.57 (0.39-0.83) | 0.004 |

| Belch | 0.50 (0.37-0.69) | < 0.001 | 0.81 (0.61-1.07) | 0.133 | 0.36 (0.26-0.51) | < 0.001 |

| Vomiting | 0.47 (0.31-0.71) | < 0.001 | 0.94 (0.64-1.37) | 0.730 | 0.79 (0.49-1.26) | 0.322 |

| Others | 0.21 (0.11-0.37) | < 0.001 | 1.19 (0.64-2.22) | 0.578 | 0.61 (0.31-1.23) | 0.168 |

MPA: Mucosal protective agent; PPI: Proton pump inhibitor; PD: Prokinetic drug; WCL: Weighted case load.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have suggested that erosions are common in chronic gastritis, especially Asian patients. In a multicenter chronic gastritis survey, 42.3% of patients were found to have CEG of varying severity[3]. Another multicenter study conducted in France that enrolled 3287 patients with upper GI bleeding revealed that 11.8% of patients aged < 75 years and 13.9% of patients aged > 75 years had gastroduodenal erosions[8]. However, there is currently insufficient data and evidence regarding CEG risk factors, symptoms, endoscopic and pathologic characteristics, and treatment strategies[15]. As a result, treatment patterns vary extensively. Moreover, evidence regarding CEG treatment outcomes is limited, especially regarding symptom improvement. Therefore, we conducted this study, which is the first real-world observational and non-interventional study in China to explore lifestyle characteristics, symptoms, endoscopic findings, treatment patterns, and short-term outcomes in patients with CEG.

In regard to patient characteristics, CEG did not show a sex predominance. Furthermore, contrary to our expectations, more than half of the patients with erosions had no history of alcohol consumption or smoking, and more than 60.0% ate a regular diet and had normal or healthy diet preferences. However, a considerable proportion of patients exhibited mood problems. Specifically, 27.3% of patients felt stressed, 24.3% felt depressed, and 31.9% felt anxious, which suggested that mood disturbances may play a role in the development of erosions. Treatment of stress-induced gastritis and gastric ulcers in the intensive care unit setting has been discussed previously[11]; however, the relationship between daily life stress and CEG has not been fully ascertained. Our results and those of previous studies suggest that CEG is a multifactorial disease which is influenced by lifestyle, obesity, infection, emotion, and mood. The correlation between a single factor, such as dietary habits, and disease incidence remains unclear and further studies are warranted.

The FUTURE study revealed that among patients with chronic symptomatic gastritis, 48.2% experienced heartburn, 68.0% had epigastralgia, and 67.5% had epigastric fullness. These were the most common symptoms[16]. In our study, the most common symptom was epigastric pain (68.0%), followed by abdominal distension (62.6%), postprandial fullness (47.5%), acid regurgitation (43.4%), belching (39.6%), early satiety (30.5%), nausea (26.7%), and vomiting (13.9%); most of these were mild or moderate in severity. To further clarify the symptom profile of erosive gastritis, we compared the ratios of different symptoms in all patients, which were comparable between those with chronic non-atrophic gastritis and those with chronic atrophic gastritis. Epigastralgia, epigastric burning, postprandial epigastric fullness, and early satiation are typical symptoms of functional dyspepsia[17]. The symptoms of CEG are non-specific and similar to those of dyspepsia. Differentiating these two diseases is crucial. A recent meta-analysis indicated that the prevalence of functional dyspepsia is higher in Western countries than in Asian countries[18]. Moreover, questions have been raised regarding the inconsistent symptom clusters for functional GI disorders in China[19]. Thus, we speculate that the lack of consensus poses difficulties in identifying CEG, which may contribute to the disparate prevalence between Asian and Western countries. Previous studies have demonstrated that the prevalence of CEG is not considered low in China and other Asian countries, which suggests that gastroscopy for patients with the above symptoms may help physicians detect and diagnose CEG in Asian patients.

Current mainstream treatment options for CEG include lifestyle guidance, MPAs, PPIs, and other symptomatic treatments. Several studies have demonstrated that geranylgeranyl acetone treatment is more effective than cimetidine for chronic gastritis-associated erosions and petechial hemorrhage[20]. In addition, rebamipide had a stronger suppressing effect on mucosal inflammation and provided greater symptom relief in CEG patients than sucralfate[10]. Furthermore, famotidine is effective in relieving abdominal symptoms in chronic symptomatic gastritis[16]. For H. pylori-associated gastritis, anti-H. pylori therapy is recommended and accepted by physicians[21,22]. However, a significant number of patients in our study were not treated using anti-H. pylori regimens and H. pylori-positive patients consistently exhibited lower symptom relief rates. Treatment of CEG varies across different centers[10,23], which is partially because of a lack of consensus and lack of treatment guidelines. However, high-level evidence evaluating the efficacy of existing treatment regimens is currently limited. In our study, PPIs and MPAs were used by 69.9% and 66.8% of patients, respectively, and 31.6% received combination treatment. Further studies comparing relief of the various symptoms between PPI, MPA, PPI + MPA, and PPI + MPA + PD may provide valuable information for selecting the most appropriate drug regimen. If epigastric pain is the predominant symptom, a MPA + PPI may provide a better response than a PPI or MPA alone. If abdominal distension is the predominant symptom, MPA may provide a slightly superior response than PPI; however, combining the two did not offer an additional benefit. Nonetheless, adding a PD to a combination of an MPA and a PPI seemed to provide greater symptom relief. If postprandial fullness, early satiety, or nausea are the most notable symptoms, the use of an MPA may be the optimal choice. When symptoms are predominantly related to acid reflux, a PPI or PPI + MPA are more effective. For patients whose predominant complaint is dyspepsia, treatment with an MPA is recommended; adding a PD may provide a better response in some cases. Our results demonstrate that individualized treatment based on symptom profile is crucial for patients with CEG.

This study is subject to several limitations. First, the absence of a control group comprising healthy individuals limits our capacity to robustly identify risk factors. Second, follow-up was only a month. While this timeframe is adequate for preliminary assessment of therapeutic responses, it is inadequate to provide a comprehensive understanding of long-term disease progression or sustainability of treatment effects. It is imperative for future studies to incorporate longer follow-up periods to thoroughly evaluate the long-term impact of treatment on symptoms, endoscopic findings, and histopathological changes and identify any late-onset adverse effects or diminished effectiveness.

CONCLUSION

We conducted the first multicenter real-world study to assess clinical characteristics, treatment patterns, and short-term outcomes in patients with CEG in China. The development of CEG is likely a multifactorial process. Epigastric pain, abdominal distension, and postprandial fullness were the most common initial symptoms. CEG is relatively common in Asians and clinical symptoms are non-specific. Therefore, gastroscopy may be valuable for CEG detection and diagnosis. Our comparisons of symptom relief between different treatment strategies should provide useful information to fellow clinicians regarding treatment selection. Patients with acid reflux symptoms may respond best to a PPI or PPI + MPA, whereas an MPA may be more effective for those with dyspepsia; in some cases, combination therapy with a PD may also be effective. Patients testing positive for H. pylori experience better symptom relief when anti-H pylori therapy is used. Taken together, our study highlights the need to individualize CEG treatment based on symptom profile.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

This multicenter observational study delves into chronic erosive gastritis (CEG) in China, a condition whose clinical characteristics and treatment approaches have been inadequately explored. It illuminates the commonality of CEG and its varied clinical presentations, emphasizing the necessity of a better understanding of its treatment patterns and short-term outcomes.

Research motivation

Addressing the pressing need for clarity in the clinical management of CEG, the study seeks to demystify the disease’s symptomatology, lifestyle influences, endoscopic findings, and treatment efficacies. It aspires to enhance the understanding of CEG’s multifactorial nature and guide more effective, personalized treatment strategies.

Research objectives

To explore the clinical characteristics, treatment patterns, and short-term outcomes in CEG patients in China.

Research methods

Employing a prospective observational cohort approach, the study involved patients with chronic non-atrophic or mild-to-moderate atrophic gastritis with erosions. It combined questionnaires, endoscopic and pathological evaluations, and follow-up assessments to evaluate treatment responses and lifestyle characteristics, offering a comprehensive view of CEG’s clinical landscape.

Research results

The study reveals the predominance of symptoms like epigastric pain, abdominal distension, and postprandial fullness in CEG, with treatments like mucosal protective agents and proton pump inhibitors showing varying effectiveness. It underscores the non-specific nature of CEG symptoms and the importance of gastroscopy in diagnosis, especially in Asian populations.

Research conclusions

This investigation proposes new insights into CEG, highlighting its multifactorial etiology influenced by lifestyle, obesity, infection, and emotional factors. The study’s findings advocate for individualized treatment strategies based on specific symptom profiles, enhancing treatment efficacy.

Research perspectives

Future research should focus on long-term outcomes of CEG treatments, the sustainability of therapeutic effects, and the identification of potential late-onset side effects. Extending the understanding of CEG’s long-term progression and refining treatment approaches are crucial steps forward.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study is reviewed and approved by the Local Ethics Committees of Peking union medical college hospital (Approval No. S-K700).

Clinical trial registration statement: This study is registered at Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR). The registration identification number is ChiCTR2100047690.

Informed consent statement: All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: There are no conflicts of interest to report.

CONSORT 2010 statement: The authors have read the CONSORT 2010 statement, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CONSORT 2010 statement.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: November 13, 2023

First decision: December 8, 2023

Article in press: February 2, 2024

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Massironi S, Italy S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zheng XM

Contributor Information

Ying-Yun Yang, Department of Gastroenterology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Peking Union Medical College, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Beijing 100730, China.

Ke-Min Li, Department of Gastroenterology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Peking Union Medical College, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Beijing 100730, China.

Gui-Fang Xu, Department of Gastroenterology, Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, Nanjing 21000, Jiangsu Province, China.

Cheng-Dang Wang, Department of Gastroenterology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou 350005, Fujian Province, China.

Hua Xiong, Department of Gastroenterology, Renji Hospital, Shanghai 200127, China.

Xiao-Zhong Wang, Department of Gastroenterology, Union Hospital of Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou 350000, Fujian Province, China.

Chun-Hui Wang, Department of Gastroenterology, West China Hospital of Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, Sichuan Province, China.

Bing-Yong Zhang, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, The People’s Hospital of Zhengzhou University, The Henan Provincial People’s Hospital, Zhengzhou 450003, Henan Province, China.

Hai-Xing Jiang, Department of Gastroenterology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning 530021, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China.

Jing Sun, Ruijin Hospital Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong Univesrity, Ruijin Hospital, School Medicine, Shanghai 200025, China.

Yan Xu, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, China-Japan Union Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun 130033, Jilin Province, China.

Li-Juan Zhang, Department of Gastroenterology, Fujian Medical University Union Hospital, Fuzhou 350001, Fujian Province, China.

Hao-Xuan Zheng, Department of Gastroenterology, Nanfang Hospital, Guangzhou 510080, Guangdong Province, China.

Xiang-Bin Xing, Department of Gastroenterology, The First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou 510080, Guangdong Province, China.

Liang-Jing Wang, Department of Gastroenterology, The Second Affiliated Hospital Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310000, Zhejiang Province, China.

Xiu-Li Zuo, Department of Gastroenterology, Shandong University Qilu Hospital, Jinan 250012, Shandong Province, China.

Shi-Gang Ding, Department of Gastroenterology, Peking University Third Hospital, Beijing 100191, China.

Rong Lin, Department of Gastroenterology, Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430022, Hubei Province, China.

Chun-Xiao Chen, Department of Gastroenterology, The First Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 315000, Zhejiang Province, China.

Xing-Wei Wang, Department of Gastroenterology, Chongqing Daping Hospital, Chongqing 400042, China.

Jing-Nan Li, Department of Gastroenterology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Beijing 100005, China; Key Laboratory of Gut Microbiota Translational Medicine Research, Chinese Academy of Medical Science, Beijing 100005, China. pumcjnl@126.com.

Data sharing statement

No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Hooi JKY, Lai WY, Ng WK, Suen MMY, Underwood FE, Tanyingoh D, Malfertheiner P, Graham DY, Wong VWS, Wu JCY, Chan FKL, Sung JJY, Kaplan GG, Ng SC. Global Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:420–429. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunt RH, Camilleri M, Crowe SE, El-Omar EM, Fox JG, Kuipers EJ, Malfertheiner P, McColl KE, Pritchard DM, Rugge M, Sonnenberg A, Sugano K, Tack J. The stomach in health and disease. Gut. 2015;64:1650–1668. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Du Y, Bai Y, Xie P, Fang J, Wang X, Hou X, Tian D, Wang C, Liu Y, Sha W, Wang B, Li Y, Zhang G, Shi R, Xu J, Huang M, Han S, Liu J, Ren X, Wang Z, Cui L, Sheng J, Luo H, Zhao X, Dai N, Nie Y, Zou Y, Xia B, Fan Z, Chen Z, Lin S, Li ZS Chinese Chronic Gastritis Research group. Chronic gastritis in China: a national multi-center survey. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-14-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sipponen P, Price AB. The Sydney System for classification of gastritis 20 years ago. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26 Suppl 1:31–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malfertheiner P, Peitz U. The interplay between Helicobacter pylori, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, and intestinal metaplasia. Gut. 2005;54 Suppl 1:i13–i20. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.041533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tatsuta M, Iishi H, Okuda S. Relationship of erosive gastritis to the acid secreting area and intestinal metaplasia, and the healing effect of pirenzepine. Gut. 1987;28:561–565. doi: 10.1136/gut.28.5.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Camilleri M, Malhi H, Acosta A. Gastrointestinal Complications of Obesity. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1656–1670. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.12.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nahon S, Nouel O, Hagège H, Cassan P, Pariente A, Combes R, Kerjean A, Doumet S, Cocq-Vezilier P, Tielman G, Paupard T, Janicki E, Bernardini D, Antoni M, Haioun J, Pillon D, Bretagnolle P Groupe des Hémorragies Digestives Hautes de l’Association Nationale des Hépatogastroentérologues des hôpitaux Généraux. Favorable prognosis of upper-gastrointestinal bleeding in 1041 older patients: results of a prospective multicenter study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:886–892. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.02.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guslandi M. Erosive gastritis--does acid matter? Gut. 1987;28:1321–1322. doi: 10.1136/gut.28.10.1321-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Du Y, Li Z, Zhan X, Chen J, Gao J, Gong Y, Ren J, He L, Zhang Z, Guo X, Wu J, Tian Z, Shi R, Jiang B, Fang D, Li Y. Anti-inflammatory effects of rebamipide according to Helicobacter pylori status in patients with chronic erosive gastritis: a randomized sucralfate-controlled multicenter trial in China-STARS study. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:2886–2895. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-0180-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller TA. Stress erosive gastritis: what is optimal therapy and who should undergo it? Gastroenterology. 1995;109:626–628. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90356-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanigawa T, Watanabe T, Higuchi K, Tominaga K, Fujiwara Y, Oshitani N, Tarnawski AS, Arakawa T. Long-term use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs normalizes the kinetics of gastric epithelial cells in patients with Helicobacter pylori infection via attenuation of gastric mucosal inflammation. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44 Suppl 19:8–17. doi: 10.1007/s00535-008-2287-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bini EJ, Rajapaksa RC, Weinshel EH. Positive predictive value of fecal occult blood testing in persons taking warfarin. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1586–1592. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fang JY, Du YQ, Liu WZ, Ren JL, Li YQ, Chen XY, Lv NH, Chen YX, Lv B Chinese Society of Gastroenterology, Chinese Medical Association. Chinese consensus on chronic gastritis (2017, Shanghai) J Dig Dis. 2018;19:182–203. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toljamo K, Niemelä S, Karvonen AL, Karttunen R, Karttunen TJ. Histopathology of gastric erosions. Association with etiological factors and chronicity. Helicobacter. 2011;16:444–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kinoshita Y, Chiba T FUTURE study group. Therapeutic effects of famotidine on chronic symptomatic gastritis: subgroup analysis from FUTURE study. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:377–386. doi: 10.1007/s00535-011-0503-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ford AC, Mahadeva S, Carbone MF, Lacy BE, Talley NJ. Functional dyspepsia. Lancet. 2020;396:1689–1702. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30469-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Potter MDE, Talley NJ. Editorial: new insights into the global prevalence of uninvestigated and functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;52:1407–1408. doi: 10.1111/apt.16059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holtmann GJ, Talley NJ. Inconsistent symptom clusters for functional gastrointestinal disorders in Asia: is Rome burning? Gut. 2018;67:1911–1915. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakamoto C, Ogoshi K, Saigenji K, Narisawa R, Nagura H, Mine T, Tada M, Umegaki E, Maekawa T, Maekawa R, Maeda K. Comparison of the effectiveness of geranylgeranylacetone with cimetidine in gastritis patients with dyspeptic symptoms and gastric lesions: a randomized, double-blind trial in Japan. Digestion. 2007;75:215–224. doi: 10.1159/000110654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sugano K, Tack J, Kuipers EJ, Graham DY, El-Omar EM, Miura S, Haruma K, Asaka M, Uemura N, Malfertheiner P faculty members of Kyoto Global Consensus Conference. Kyoto global consensus report on Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Gut. 2015;64:1353–1367. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Q, Lu H. Kyoto global consensus report on Helicobacter pylori gastritis and its impact on Chinese clinical practice. J Dig Dis. 2016;17:353–356. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yüksel O, Köklü S, Başar O, Yüksel I, Akgül H. Erosive gastritis mimicking watermelon stomach. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1606–1607. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No additional data are available.