Abstract

Due to the increasing environmental pollution of un-degradable plastics and the consumption of non-renewable resources, more attention has been attracted by new bio-degradable/based polymers produced from renewable resources. Polylactic acid (PLA) is one of the most representative bio-based materials, with obvious advantages and disadvantages, and has a wide range of applications in industry, medicine, and research. By copolymerizing to make up for its deficiencies, the obtained copolymers have more excellent properties. The development of a one-step microbial metabolism production process of the lactate (LA)-based copolymers overcomes the inherent shortcomings in the traditional chemical synthesis process. The most common lactate-based copolymer is poly(lactate-co-3-hydroxybutyrate) [P(LA-co-3HB)], within which the difference of LA monomer fraction will cause the change in the material properties. It is necessary to regulate LA monomer fraction by appropriate methods. Based on synthetic biology and systems metabolic engineering, this review mainly focus on how did the different production strategies (such as enzyme engineering, fermentation engineering, etc.) of P(LA-co-3HB) optimize the chassis cells to efficiently produce it. In addition, the metabolic engineering strategies of some other lactate-based copolymers are also introduced in this article. These studies would facilitate to expand the application fields of the corresponding materials.

Keywords: Lactate-based copolymer, P(LA-co-3HB), Microbial synthesis, Production strategy

Introduction

Almost all traditional organic copolymers come from petrochemical industry, which will cause ‘greenhouse effect’, ‘white pollution’, and other environmental problems in the process of production, application, and management. With the increasing tension of resource development and people’s continued attention to the environmental issues, most of the research concepts in recent years are in line with the characteristics of recycling and environmental protection. Bio-based polymers, which can be degraded by microorganisms and are made from natural materials, have attracted much attention in recent years (Taguchi et al. 2008; Matsumoto and Taguchi 2010; Park et al. 2012a; Yang et al. 2013; Choi et al. 2020b).

Nowadays, PLA is one of the most representative bio-based polymers, its most notable features are biocompatibility and biodegradability (Pang et al. 2010; Shah et al. 2014). In addition to the above mentioned, PLA also has pros and cons, such as the advantages of high strength, high modulus, biocompostability, low toxicity, etc., as well as the disadvantages of hydrophobicity, low impact toughness, etc. Due to its complex biological and chemical production processes, PLA is relatively expensive compared with other commercial plastics (Lee et al. 2019; Singhvi et al. 2019). In order to make up for its shortcomings, copolymerization with other compositions is the most effective method. After copolymerization, the properties of PLA will be adjusted, such as degradation cycle, mechanical properties, hydrophilic properties, lipophilic properties, etc. At the same time, with the change of the composition and the proportion of the copolymers, PLA and its copolymers [belonging to polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA), which is the general term for a class of bio-based polymers] will have more extensive applications, such as medical field (efficient nanocarriers for drug delivery applications, etc.) and other fields (Södergård and Stolt 2002; Makadia and Siegel 2011; Giammona and Craparo 2018; Singhvi et al. 2019; Su et al. 2020).

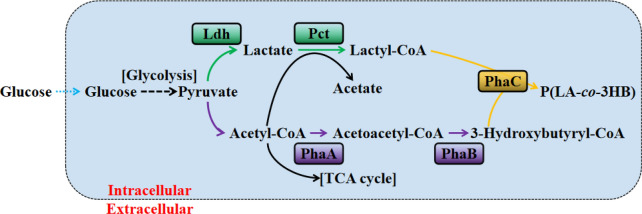

In 2008, Taguchi et al. (2008) firstly established a one-step microbial metabolic process for the synthesis of a representative lactate-based copolymer, P(LA-co-3HB) (Fig. 1). The disadvantages of residues, which are generated in the process of chemical synthesis of the lactate-based copolymers, are effectively avoided by using the biosynthesis method. In addition, isolated microbial enzymes (such as lipase) also have been successfully used as catalysts for the production of the copolymers with diverse structures, various compositions and properties (Jiang and Zhang 2013).

Fig. 1.

Synthetic pathway of P(LA-co-3HB) in recombinant Escherichia coli. Letters in boxes indicate enzymes. Ldh lactate dehydrogenase, Pct propionyl-CoA transferase, PhaA β-ketothiolase, PhaB NADPH-dependent acetoacetyl-CoA reductase, PhaC PHA synthase

In P(LA-co-3HB), the molecular weight of it will decrease with LA monomer incorporating into the copolymer (Yamada et al. 2011). Thermodynamic analysis reveals that melting (Tm) and glass transition (Tg) temperatures of the copolymer vary with the change of the mole percentage of LA monomer fraction. The copolymer with the higher mole percentage of LA monomer fraction usually has a lower melting temperature (Tm) and a higher glass transition temperature (Tg) (Yamada et al. 2009, 2010, 2011; Ishii et al. 2017). However, Yamada et al. (2010) point out that the change of glass transition temperature (Tg) also needs to consider the molecular weight of the copolymer. In terms of the mechanical properties, Young’s modulus of the copolymer is lower than that of the homopolymer, and it decreases with the increase of the mole percentage of LA monomer fraction. The elongation at break of the copolymer is higher than that of the homopolymer and can be maintained for a relatively long time (Yamada et al. 2011; Ishii et al. 2017). The crystallinity of cast film [mainly due to the crystallization of 3-hydroxybutyrate (3HB)] decreases with the increase of LA monomer fraction (Yamada et al. 2010; Ishii et al. 2017). When the mole percentage of LA monomer fraction of the copolymer is higher than 15%, the transparency of the copolymer film increases significantly (Yamada et al. 2011).

It is meaningful to compare the material properties of P(LA-co-3HB) with the homopolymers PLA and poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) [P(3HB)]. PLA is a rigid, transparent, and compostable biodegradable material, P(3HB) is rigid and opaque but has high biodegradability, while P(LA-co-3HB) combines the advantages of PLA and P(3HB) in terms of transparency and biodegradability (Taguchi and Matsumoto 2020). Whereas, compared with PLA, PHAs containing 3HB, 3-hydroxyvalerate (3HV), and 4-hydroxybutyrate (4HB) have a higher hazard (cytotoxicity) due to their relatively low acidity and bioactivity (Singh et al. 2019). In addition, the hydrophobicity of the lactate-based copolymers lead to its poor biocompatibility, which will limit its application in some fields (such as medical field). These existing shortcomings of the lactate-based copolymers indicate that further studies and developments are needed before their commercialization. While the commercialization of the lactate-based copolymers has not been reported, in recent years there are more and more researches focus on P(LA-co-3HB). The properties [enantiomeric purity; sequential structure and molecular weight; thermal and mechanical properties (Nduko and Taguchi 2019)] of P(LA-co-3HB) are affected by the mole percentage of incorporated monomers, and different properties will affect its application in different fields. Therefore, it is very important to regulate the mole percentage of the monomer composition in the copolymers, especially to increase the mole percentage of LA monomer fractions in the copolymers. However, researchers will face the problems of the poor specificity of precursor supply enzymes and PHA synthases, as well as the inappropriate chassis cells, etc. So it is necessary to adjust microbial metabolic pathways through genetic engineering, fermentation engineering, etc. (Park et al. 2012a; Matsumoto and Taguchi 2013a, b).

Although the main contents of this article are the different production strategies of biosynthetic P(LA-co-3HB), the representative lactate-based copolymer, other microbial synthesis strategies of PHA containing LA are also introduced here (Table 1).

Table 1.

Different production strategies for P(LA-co-3HB)

| Authors | Strategies | Engineered microorganisms | Key characteristics | Main substrates | Lactate-based copolymer production statuses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taguchi et al. (2008) | Enzyme engineering | E. coli JM109 | Checking effect of PhaC from Pseudomonas sp. 61–3 with mutagenesis of two sites (S325T and Q481K); adding 10 mM calcium pantothenate to increase LA monomer fraction | 20 g/L glucose | Engineered E. coli expressing PhaC1Ps(ST/QK) and PctMe can synthesize 19 wt% P(6 mol% LA-co-3HB); Mn: (×105) = 1.9, Mw: (×105) = 4.8, Mw/Mn = 2.4 |

| Yamada et al. (2010) | E. coli BW25113 | Deleting pflA; checking effect of PhaC1Ps(ST/QK) with mutagenesis of F392; adding 10 mM calcium pantothenate | 20 g/L glucose | E. coli JW0885 expressing PhaC1Ps(ST/FS/QK) and PctMe can synthesize 62 wt% P(45 mol% LA-co-3HB) with an increased PHA content and the highest LA monomer fraction; Mn: (×104) = 2, Mw: (×104) = 8, Mw/Mn = 4.0 | |

| Yang et al. (2010) | E. coli XL1-Blue | Checking effect of the mutants of four sites in PhaC1Ps6-19 (E130, S325, S477, and Q481) and two mutants of PctCp (Pct532Cp and Pct540Cp) | 20 g/L glucose | Engineered E. coli expressing different enzymes can synthesize different copolymers | |

| Yang et al. (2011) | E. coli XL1-Blue | Checking effect of four kinds of engineering-type II PhaC1s with mutagenesis of four sites (E130, S325, S477, and Q481) | 20 g/L glucose | Engineered E. coli expressing different PhaC1s and Pct540Cp can synthesize different copolymers | |

| Ochi et al. (2013) | E. coli LS5218 | Introducing phaJ4; checking effect of PhaC from C. necator with mutagenesis of A510 | 5 g/L (R)-LA; 3 g/L sodium dodecanoate | Engineered E. coli expressing PhaCRe(AS) and PctMe can mainly synthesize P(5 mol% LA-co-3HB) with a relatively high PHA production and a stable LA monomer fraction; Mn: (×105) = 1.4, Mw: (×105) = 3.2, Mw/Mn = 2.3 | |

| Kim et al. (2016) | E. coli XL1-Blue | Checking effect of Pct from C. beijerinckii, C. perfringens, and K. pneumoniae | 20 g/L glucose | Engineered E. coli expressing PhaC1437Ps6-19 and Pct of C. perfringens can synthesize 10.6 wt% P(13.6 mol% LA-co-3HB) | |

| David et al. (2017) | E. coli XL1-Blue | Checking effect of Bct from four strains from different genus | 20 g/L glucose | Engineered E. coli expressing PhaC1437Ps6-19 and different Bcts can synthesize different copolymers | |

| Yang et al. (2018) | E. coli XL1-Blue | Checking effect of FldA and HadA; introducing the aromatic copolymer production module | 20 g/L glucose | Engineered E. coli expressing PhaC1437Ps6-19 can synthesize the copolymers containing d-phenyllactate and d-4-hydroxyphenyllactate | |

| Jung et al. (2010) | Metabolic pathway construction | E. coli XL1-Blue | Deleting ackA, ppc, and adhE; replacing ldhA and acs natural promoters with trc; strains lacking ppc need additional 4 g/L sodium succinate | 20 g/L glucose | E. coli JLX10 expressing PhaC1310Ps6-19 and Pct540Cp can synthesize 19 wt% P(60 mol% LA-co-3HB); expressing PhaC1400Ps6-19 and Pct532Cp can synthesize 46 wt% P(70 mol% LA-co-3HB) |

| Jung and Lee (2011) | E. coli XB-F | Deleting lacI, pflB, frdABCD, and adhE; replacing ldhA and acs natural promoters with trc; strains lacking lacI does not need additional IPTG | 20 g/L glucose | E. coli JLXF5 expressing PhaC1310Ps6-19 and Pct540Cp can synthesize 15.2 wt% P(67.4 mol% LA-co-3HB) | |

| Nduko et al. (2014) | E. coli BW25113 | Deleting pflA, pta, ackA, poxB, and dld; overexpressing GatC to increase the utilization of xylose; adding 10 mM calcium pantothenate | 20/30/40 g/L xylose | E. coli JWMB1 expressing PhaC1Ps(ST/FS/QK) and PctMe can synthesize 58 wt% P(73 mol% LA-co-3HB) from 20 g/L xylose; Mn: (×104) = 1.7, Mw: (×104) = 3.8, Mw/Mn = 2.2 | |

| Salamanca-Cardona et al. (2014a) | E. coli LS5218 | Deleting pflA | 20 g/L xylose | E. coli RSC10 expressing PhaC1Ps(ST/QK) and PctMe can synthesize 41.1 wt% P(8.3 mol% LA-co-3HB) | |

| Kadoya et al. (2015a) | E. coli BW25113 | Deleting RpoS, RpoN, FliA, and FecI, which are E. coli non-essential σ factors; adding 10 mM calcium pantothenate | 20 g/L glucose | E. coli JW3169 expressing PhaC1Ps(ST/QK) and PctMe can synthesize 75.1 wt% P(26.2 mol% LA-co-3HB) | |

| Kadoya et al. (2015a) | E. coli BW25113 | Deleting mtgA, which plays an auxiliary role in peptidoglycan synthesis; adding 10 mM calcium pantothenate | 20 g/L glucose | E. coli JW3175 expressing PhaC1Ps(ST/QK) and PctMe can synthesize 7.0 g/L copolymer with an increased yield | |

| Kadoya et al. (2017) | E. coli BW25113 | Deleting PdhR, CspG, YneJ, ChbR, YiaU, CreB, YgfI, and NanK, which are E. coli non-lethal transcription factors; adding 10 mM calcium pantothenate | 30 g/L glucose | Engineered E. coli expressing PhaC1Ps(ST/QK) and PctMe with an increased copolymer yield (6.2–10.1 g/L) | |

| Kadoya et al. (2018) | E. coli BW25113 | Overexpression Mlc, which is a multiple regulator of glucose and xylose uptake; adding 10 mM calcium pantothenate | 50 g/L mixed sugar (wt%, glucose:xylose = 4:1) | Engineered E. coli expressing PhaC1Ps(ST/QK) and PctMe can synthesize 64.9 wt% P(11.8 mol% LA-co-3HB); Mn: (×104) = 6.7, Mw: (×104) = 9.4, Mw/Mn = 1.4 | |

| Yang et al. (2018) | E. coli XL1-Blue | Deleting ldhA, adhE, pflB, frdB, and poxB; introducing the aromatic copolymer production module | 20 g/L glucose | Engineered E. coli expressing PhaC1437Ps6-19 can synthesize the copolymers containing d-phenyllactate and d-4-hydroxyphenyllactate | |

| Goto et al. (2019b) |

E. coli DH5α E. coli LS5218 E. coli XL1-Blue |

Introducing ldhD | 20 g/L glucose | Engineered E. coli expressing PhaC1Ps(ST/QK) and PctMe can synthesize the copolymers with an increased LA monomer fraction compared with original strains | |

| Lu et al. (2019) | E. coli MG1655 | Deleting ubiX to attenuate respiratory chain; deleting dld; checking effect of different concentrations of IPTG and l-arabinose | 20 g/L glucose | E. coli JX041 expressing PhaCm(ED/ST/QK) and Pct540Cp can synthesize 81.7 wt% P(14.1 mol% LA-co-3HB) | |

| Wei et al. (2021) | E. coli MG1655 | Deleting ydiI, yciA, and dld | 20 g/L glucose; 20 g/L xylose | E. coli WXJ03 expressing PhaCm(ED/ST/QK) and Pct540Cp can synthesize 66.3 wt% P(46.1 mol% LA-co-3HB) from xylose | |

| Wu et al. (2021) | E. coli MG1655 | Deleting ubiX, ptsG, and dld | 10 g/L mixed sugar (wt%, glucose:xylose = 7:3) | E. coli WJ03 expressing PhaCm(ED/ST/QK) and Pct540Cp can synthesize P(7 mol% LA-co-3HB) | |

| Nduko et al. (2013) | Different substrates | E. coli BW25113 | Deleting pflA; checking effect of glucose and xylose; adding 10 mM calcium pantothenate | 20 g/L glucose; 20 g/L xylose | E. coli JW0885 expressing PctMe produces the copolymer have a higher LA monomer fraction (34 mol%) from xylose; Mn: (×104) = 4.0, Mw: (×104) = 17, Mw/Mn = 4.1; PhaC1Ps(ST/FS/QK) has a better effect than PhaC1Ps(ST/QK) |

| Oh et al. (2014) | E. coli W | Sucrose is broken down into fructose and glucose in vivo | 20 g/L sucrose | Engineered E. coli expressing PhaC1437Ps6-19 and Pct540Cp can synthesize 12.2 wt% P(16 mol% LA-co-3HB); Mn: (×104) = 1.53, Mw: (×104) = 2.78, Mw/Mn = 1.82 | |

| Salamanca-Cardona et al. (2014b) | E. coli LS5218 | Introducing xylB and xynB; adding single sugar to assist the copolymer production from beechwood xylan | 10 g/L xylan; combination of a single sugar substrate (20 g/L xylose or arabinose) and xylan (10 g/L) | Engineered E. coli expressing PhaC1Ps(ST/QK) and PctMe can synthesize 40.4 wt% P(2.1 mol% LA-co-3HB) from xylose and xylan; Mn: (×105) = 1.18, Mw: (×105) = 2.78, Mw/Mn = 2.35; 30.3 wt% P(3.7 mol% LA-co-3HB) from arabinose and xylan; Mn: (×105) = 1.13, Mw: (×105) = 3.03, Mw/Mn = 2.67 | |

| Salamanca-Cardona et al. (2014a) | E. coli LS5218 | Deleting pflA; using xylose and acetate to simulate xylan derived from beechwood | 20 g/L xylose; 33 mM acetate | E. coli RSC10 expressing PhaC1Ps(ST/QK) and PctMe can synthesize 41.1 wt% P(8.3 mol% LA-co-3HB) from xylose; 4.2 wt% P(18.5 mol% LA-co-3HB) from xylose and acetate; adding acetate increases LA monomer fraction | |

| Oh et al. (2015) |

E. coli XL1-Blue C. necator |

Introducing ldhA into C. necator; rice bran hydrolysates are purified by a series of processes and concentrated; resulting solution contains 16.3% (w/w) glucose | 10 mL/L rice bran hydrolysate solution (corresponds to 20 g/L glucose and 3.4 g/L fructose) | Engineered E. coli expressing PhaC1437Ps6-19 and Pct540Cp can synthesize 82.3 wt% P(28.6 mol% LA-co-3HB); C. necator 437–540 expressing the same enzymes can synthesize 35.8 wt% P(7.3 mol% LA-co-3HB) | |

| Sun et al. (2016) | E. coli BW25113 | Lignocellulosic biomass is treated by NaClO2 and NaOH in the two-step process to obtain the highest total sugar yield; the two-step process does not produce the toxic hydrolysates; the hydrolysates mainly include glucose, xylose, and trace arabinose; adding 10 mM calcium pantothenate | Miscanthus × giganteus (hybrid Miscanthus); rice straw hydrolysate solution | Engineered E. coli expressing PhaC1Ps(ST/QK) and PctMe basically has no effect on content, yield, and LA monomer fraction of the copolymer when using the hydrolysate solution derived from hybrid Miscanthus; Mn: (×104) = 7.7 Mw: (×104) = 37.0, Mw/Mn = 4.8; decreases LA monomer fraction when using the hydrolysate solution derived from rice straw; Mn: (×104) = 7.1, Mw: (×104) = 36.2, Mw/Mn = 5.1 | |

| Salamanca-Cardona et al. (2017) |

E. coli BW25113 E. coli BW25113 (ΔpflA) E. coli LS5218 E. coli LS5218 (ΔpflA) |

E. coli LS5218 (ΔpflA) is an acetate-tolerant strain and even produces the copolymer using acetate as a sole carbon source | 20 g/L xylose; 25 mM acetate | E. coli RSC10 expressing PhaC1Ps(ST/QK) and PctMe can synthesize 45.3 wt% P(13.1 mol% LA-co-3HB); Mn: (×104) = 6.3, Mw: (×104) = 26.5, Mw/Mn = 5.0 | |

| Takisawa et al. (2017) | E. coli BW25113 | Woody extract is treated by a series of processes and the hemicellulosic hydrolysate’s total sugar concentration is 154.5 g/L; the purified hydrolysates’ total sugar concentration are 133.0 and 62.4 g/L for active charcoal treatment and ion-exchange resin treatment, respectively; adding 10 mM calcium pantothenate | The hemicellulosic hydrolysate solution derived from dissolving pulp manufacturing-obtained woody extract; 0/1/2/5/10 g/L acetate | Engineered E. coli expressing PhaC1Ps(ST/QK) and PctMe can synthesize 62.4 wt% P(5.5 mol% LA-co-3HB); Mn: (×104) = 6.9, Mw: (×104) = 48, Mw/Mn = 7.0; adding acetate decreases PHA content and LA monomer fraction | |

| Kadoya et al. (2018) | E. coli BW25113 | Hybrid Miscanthus is treated by NaClO2 and NaOH in the two-step process; assuming a small amount of acetate in the hydrolysate inhibits the copolymerization of LA; adding 10 mM calcium pantothenate | Miscanthus × giganteus (hybrid Miscanthus) hydrolysate solution | Engineered E. coli expressing PhaC1Ps(ST/QK) and PctMe decreases LA monomer fraction; Mn: (×104) = 6.7, Mw: (×104) = 9.4, Mw/Mn = 1.4 | |

| Sohn et al. (2020) |

E. coli DH5α E. coli JM109 E. coli Top10 E. coli W3110 (ΔlacI) E. coli XL1-Blue E. coli XL10-Gold |

Introducing sacC; sucrose is broken down into fructose and glucose; all E. coli produces the copolymers | 20 g/L sucrose | Engineered E. coli XL1-Blue expressing PhaC1437Ps6-19 and Pct540Cp can synthesize P(42.3 mol% LA-co-3HB) with the highest concentration (0.576 g/L) and a relatively high content (29.44 wt%) | |

| Wu et al. (2021) | E. coli MG1655 | Deleting ubiX, ptsG, and dld; corn straw is hydrolyzed with sodium hydroxide solution and the impurities are removed by active charcoal treatment and filtration | Corn straw hydrolysate solution | E. coli WJ03 expressing PhaCm(ED/ST/QK) and Pct540Cp can synthesize P(7.1 mol% LA-co-3HB) | |

| Yamada et al. (2009) | Culture conditions | E. coli W3110 | Culturing in anaerobic conditions after 24 h aerobic cultivation; adding 10 mM calcium pantothenate | 20 g/L glucose | Engineered E. coli expressing PhaC1Ps(ST/QK) and PctMe can synthesize 2 wt% P(47 mol% LA-co-3HB); Mn: (×104) = 1.5, Mw: (×104) = 2.0, Mw/Mn = 1.3 |

| Yamada et al. (2010) | E. coli BW25113 | Deleting pflA; culturing in anaerobic conditions after 16 h aerobic cultivation in a jar fermentor; adding 10 mM calcium pantothenate | 20 g/L glucose |

E. coli JW0885 expressing PhaC1Ps(ST/QK) and PctMe can synthesize 15 wt% P(47 mol% LA-co-3HB); Mn: (×104) = 2, Mw: (×104) = 6, Mw/Mn = 3.0; expressing PhaC1Ps(ST/FS/QK) and PctMe can synthesize 12 wt% P(62 mol% LA-co-3HB); Mn: (×104) = 1, Mw: (×104) = 4, Mw/Mn = 4.0; anaerobic conditions decrease the copolymer content and increase LA monomer fraction |

|

| Yang et al. (2010) | E. coli XL1-Blue | Adjusting DOC (30%, 10%), pH (by 28% (v/v) ammonia water) and glucose concentration in a jar fermentor | 15/5 g/L glucose | Engineered E. coli expressing PhaC1310Ps6-19 and Pct540Cp can adjust LA monomer fraction ranging from 8.7 to 64.4 mol% | |

| Jung and Lee (2011) | E. coli XB-F | Deleting lacI, pflB, frdABCD, and adhE; replacing ldhA and acs natural promoters with trc; strains lacking lacI does not need additional IPTG; adjusting DOC (above 40%), pH (by 28% (v/v) ammonia water) in a jar fermentor | 20 g/L glucose | E. coli JLXF5 expressing PhaC1310Ps6-19 and Pct540Cp can synthesize 43 wt% P(39.6 mol% LA-co-3HB) in about 80 h; molecular weight: (×105) = 1.41 | |

| Yamada et al. (2011) |

E. coli JM109 E. coli BW25113 (ΔpflA) |

Culturing in anaerobic conditions after 16 h aerobic cultivation in a jar fermentor; adding 10 mM calcium pantothenate | 20 g/L glucose | E. coli JW0885 expressing PhaC1Ps(ST/QK) and PctMe can adjust LA monomer fraction ranging from 29 to 47 mol% | |

| Oh et al. (2015) |

E. coli XL1-Blue C. necator |

Introducing ldhA into C. necator; adjusting pH by 28% (v/v) NH4OH in a jar fermentor; the utilization of batch fermentation overcomes the bottleneck of the utilization of fructose | 100 mL/L rice bran hydrolysate solution | Engineered E. coli expressing PhaC1437Ps6-19 and Pct540Cp can synthesize 53.89 wt% P(3.63 mol% LA-co-3HB) in 39 h resulting in the highest LA monomer fraction; C. necator 437–540 expressing the same enzymes can’t use up fructose in 63 h; Mn: (×104) = 2.19, Mw: (×104) = 4.16, Mw/Mn = 1.90 | |

| David et al. (2017) | E. coli XL1-Blue | Adjusting pH by 28% (v/v) NH4OH in a jar fermentor | 20 g/L glucose | Compared with Pct540Cp, engineered E. coli expressing PhaC1437Ps6-19 and BctEh shows higher OD600 and weight percentage, but LA monomer fraction is lower | |

| Yang et al. (2018) | E. coli XL1-Blue | Introducing the aromatic copolymer production module; using fed-batch fermentation, which is performed by the pH-stat strategy and the pulsed-feeding strategy; adjusting DOC (above 40%) and pH (by 28% (v/v) ammonia solution) in a jar fermentor | 20/10 g/L glucose | Engineered E. coli expressing PhaC1437Ps6-19 can synthesize aromatic PHAs to a reasonably high concentration | |

| Goto et al. (2019b) |

E. coli DH5α E. coli LS5218 E. coli XL1-Blue |

Introducing ldhD; creating relatively anaerobic conditions (shaking speed = 0/60 strokes/min) | 20 g/L glucose | Engineered E. coli expressing PhaC1Ps(ST/QK) and PctMe can synthesize the copolymers with an increased LA monomer fraction in relatively anaerobic conditions | |

| Hori et al. (2019) | E. coli MG1655 | Initial sugar is glucose; feed is xylose, and its concentration rises with time; adjusting pH by 4 N NaOH in a jar fermentor | 20 g/L glucose; 5/10/30 g/L xylose | Engineered E. coli expressing PhaC1Ps(ST/QK) and PctMe can synthesize 44.3 wt% P(4.9 mol% LA-co-3HB); Mn: (×104) = 2.8, Mw: (×104) = 16, Mw/Mn = 5.7 | |

| Sohn et al. (2020) | E. coli XL1-Blue | Introducing sacC; adjusting pH by 28% (v/v) NH4OH in a jar fermentor; the utilization of batch fermentation overcomes the bottleneck of the utilization of fructose | 20 g/L sucrose | Engineered E. coli expressing PhaC1437Ps6-19 and Pct540Cp can synthesize 20.88 wt% P(38 mol% LA-co-3HB) in 28 h | |

| Song et al. (2012) | Non-traditional chassis cells | C. glutamicum | Introducing ldhA; adding 0.45 mg/L biotin causes C. glutamicum not to produce glutamate | 60 g/L glucose | Engineered C. glutamicum expressing PhaC1Ps(ST/QK) and PctMe can synthesize 2.4 wt% P(96.8 mol% LA-co-3HB); Mn: (×103) = 5.2, Mw: (×103) = 7.4, Mw/Mn = 1.4 |

| Park et al. (2013b) | C. necator | Introducing ldhA | 20 g/L glucose | C. necator 437–540 expressing PhaC1437Ps6-19 and Pct540Cp can synthesize 33.9 wt% P(37 mol% LA-co-3HB) | |

| Park et al. (2015) | C. necator | Introducing sacC and ldhA; adjusting pH by 28% (v/v) NH4OH in a jar fermentor | 20 g/L sucrose | C. necator 437–540 expressing PhaC1437Ps6-19 and Pct540Cp can synthesize 19.5 wt% P(21.5 mol% LA-co-3HB); Mn: (×104) = 2.19, Mw: (×104) = 4.17, Mw/Mn = 1.90 | |

| Tran and Charles (2016) | S. meliloti Rm1021 | Replacing phbC with PhaC1400Ps6-19 and Pct532Cp | Yeast mannitol | S. meliloti SmUW254 expressing PhaC1400Ps6-19 and Pct532Cp can synthesize P(30 mol% LA-co-3HB) |

Enzymes related to copolymer synthesis which are not specifically described include propionyl-CoA transferase (Pct), β-ketothiolase (PhaA), and NADPH-dependent acetoacetyl-CoA reductase (PhaB). If engineered strains do not have a 3HB synthesis pathway, 3HB needs to be added to the medium

Mn: number-average molecular weight; Mw: weight-average molecular weight; Mw/Mn: polydispersity index

Different engineered strategies of E. coli for P(LA-co-3HB) biosynthesis

Enzyme engineering

The wild-type E. coli cannot provide D-LA-CoA, which is required for copolymer synthesis, so CoA transferase is needed to produce it. Propionate-CoA transferase of Clostridium propionicum (PctCp) is one of the most representative CoA transferases. In addition, Pct of Megasphaera elsdenii has also been used, which contribute to the heterologous expression in E. coli (Taguchi et al. 2008). Different precursors containing CoA require polymerization of PhaC, and the PhaC that can polymerize LA into the copolymers effectively is called LA-CoA polymerizing enzyme (LPE); the discovery of LPE is a decisive breakthrough in the biosynthesis of the lactate-based copolymers (Taguchi et al. 2008; Matsumoto and Taguchi 2013b). To adjust the monomer composition of the copolymers, researchers are committed to discovering new enzymes or improving the activity and the substrate specificity of existing enzymes by random mutagenesis, screening, or structure prediction based on homologous sequences of identified enzymes (Choi et al. 2020b).

LPE is created by introducing double mutations, S325T and Q481K, into PHA synthase 1 (PhaC1Ps6-19) of Pseudomonas sp. 61-3 (Taguchi et al. 2008; Tajima et al. 2009). To find the same effect, the same mutations are introduced into Pseudomonas sp. MBEL 6-19 at the corresponding sites of PHA synthase 1 (PhaC1Ps6-19). The mutant enzyme cannot polymerize LA-CoA into the copolymers effectively. Its activity can be improved by gene mutations of its four sites (E130, S325, S477, and Q481), which are previously addressed through evolutionary engineering studies performed by Taguchi’s group (Taguchi and Doi 2004; Shozui et al. 2009) (Yang et al. 2010). Further engineered type II Pseudomonas PHA synthases 1 (PhaC1s) are obtained from Pseudomonas chlororaphis, Pseudomonas sp. 61-3, Pseudomonas putida KT2440, Pseudomonas resinovorans, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 by mutagenesis of four sites (E130, S325, S477, and Q481) (Yang et al. 2011). Base on the PhaC1Ps6-19 (Taguchi et al. 2008), another mutant, F392, is obtained. Engineered E. coli BW25113 (with mutated PHA synthase, F392S) along with the pyruvate formate lyase activating enzyme gene (pflA) deletion can synthesize 62 wt% P(45 mol% LA-co-3HB) in a medium containing 20 g/L glucose with the highest LA monomer fraction (Yamada et al. 2010). Ren et al. (2017) examine the mutation effects of PhaC1 (E130D, S325T, F392S, S477G, and Q481K) and PhaC2 (S326T, S478G, and Q482K) of Pseudomonas stutzeri. Lu et al. (2019) examine the mutation effects of PhaCm (E130D, S325T, and Q481K) of Pseudomonas fluorescens. In addition, it should be noted that LPE has a strict substrate specificity toward D-LA-CoA, which is obtained from enantiomer analysis of P(LA-co-3HB) synthesized in vivo and analysis of LPE in vitro, the synthesized copolymers by LPE are almost entirely composed of D-LA (Tajima et al. 2009; Yamada et al. 2009; Matsumoto and Taguchi 2013b).

Type I PHA synthase of Cupriavidus necator (PhaCRe) exhibits activity toward 2-hydroxybutyryl-CoA (2HB-CoA) in vitro (Han et al. 2011). Similar to position 481 in type II PHA synthase (PhaC1Ps6-19) (Taguchi et al. 2008), PhaCRe is mutated at position 510. Partially engineered E. coli LS5218 (A510X) can synthesize the copolymers in a medium with 5 g/L (R)-LA and 3 g/L sodium dodecanoate, indicating that 510 residue plays a key role in LA polymerization (Ochi et al. 2013).

PctCp cannot convert LA into LA-CoA effectively, and it also exert the inhibitory effects on cell growth (Yang et al. 2010). While when some sites of PctCp are mutated, its activity can be promoted and the inhibition of cell growth can be alleviated. Two beneficial PctCp mutants have been constructed to achieve these two goals. One mutant is Pct532Cp, within which with amino acid mutation of A243T and A1200G (silent nucleotide mutation). Another mutant is Pct540Cp with amino acid mutation of V193A and four silent nucleotide mutations of T78C, T669C, A1125G, as well as T1158C (Yang et al. 2010). Engineered E. coli XL1-Blue with the expression of the phaC1437 gene of Pseudomonas sp. MBEL 6-19 and the CB3819 gene (or the CB4543 gene) of Clostridium beijerinckii can synthesize P(3HB) within a medium containing 20 g/L glucose and 2 g/L sodium 3HB. Engineered E. coli XL1-Blue with the expression of the pct gene of Clostridium perfringens can synthesize 10.6 wt% P(13.6 mol% LA-co-3HB) in the same culture media too (Kim et al. 2016). Four butyryl-CoA transferases (Bct) of Roseburia sp., Eubacterium hallii, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, and Anaerostipes caccae can polymerize LA, 2HB, and 3HB with different activities (David et al. 2017).

Moreover, cinnamoyl-CoA:phenyllactate CoA-transferase (FldA) of Clostridium sporogenes can transfer CoA from cinnamoyl-CoA to phenyllactate and 4-hydroxyphenyllactate; isocaprenoyl-CoA:2-hydroxyisocaproate CoA-transferase (HadA) of Clostridium difficile which can use acetyl-CoA as a CoA donor is further identified, and have been revealed that it has a wider substrate spectrum than FldA (Yang et al. 2018).

Metabolic pathway engineering

Lactyl-CoA and acetyl-CoA are two precursors of P(LA-co-3HB), both of them are derived from pyruvate. These indicate that regulation of metabolic flux of pyruvate is an effective method to adjust LA monomer fraction in the copolymers. The overexpression of the key pathway genes or blocking competitive pathways are both effective metabolic engineering strategies to achieve this gold. Except for these two strategies, there are still some other methods that can adjust LA monomer fraction in the copolymers.

The deletion of the acetate kinase gene (ackA) and the phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase gene (ppc), as well as the replacement of the native promoter of the d-lactate dehydrogenase gene (ldhA) with the trc promoter, can regulate the metabolic flux by rational engineering. In addition, the deletion of the acetaldehyde/alcohol dehydrogenase gene (adhE) and the replacement of the native promoter of the acetyl-CoA synthetase gene (acs) with the trc promoter by in silico gene knockout simulation as well as flux response analysis can further regulate the metabolic flux. Engineered E. coli XL1-Blue increased the copolymer content and LA monomer fraction up to ca. 3.7-fold (in case of expressing PhaC1310Ps6-19, Pct540Cp, and PhaABCn) and 2.6-fold (in case of expressing PhaC1400Ps6-19, Pct532Cp, and PhaABCn), respectively (Jung et al. 2010). With the deletion of the pyruvate formate lyase gene (pflB), the fumarate reductase gene (frdABCD), and the adhE gene, engineered E. coli XB-F can synthesize 15.2 wt% P(67.4 mol% LA-co-3HB) in a medium containing 20 g/L glucose along with the trc promoter replacement of the ldhA and acs genes (Jung and Lee 2011). Partial deletion of other target genes, such as the pflA gene, the phosphate acetyltransferase gene (pta), the pyruvate oxidase gene (poxB), the NAD+-independent lactate dehydrogenase gene (dld), and the ackA gene, are also conducive to improve the copolymers. With the deletion of the pflA and dld genes, engineered E. coli BW25113 can synthesize 58 wt% P(73 mol% LA-co-3HB) in a medium containing 20 g/L xylose. In addition, the overexpression of non-ATP consuming galactitol permease (GatC) to promote the absorption of xylose can increase the copolymer yield and LA monomer fraction of some mutants (Nduko et al. 2014). PflB is regulated by PflA, then the deletion of the pflA gene can increase the flux of pyruvate into LA and acetyl-CoA. Engineered E. coli LS5218 can synthesize 45.1 wt% P(0.9 mol% LA-co-3HB) in a medium with 20 g/L glucose and 41.1 wt% P(8.3 mol% LA-co-3HB) in a medium with 20 g/L xylose, respectively. However, when compared with the wild-type strain, the increase of LA monomer fraction could be offset for the significantly lower total cell biomass (Salamanca-Cardona et al. 2014a). Engineered E. coli BW25113 along with the deletion of the monofunctional peptidoglycan transglycosylase gene (mtgA) can enhance the copolymer production. Simultaneously, with the deletion of mtgA, the widths of the mutant cells become wilder than that of the wild-type cells (Kadoya et al. 2015a). The introduction of the D-LDH gene (ldhD) of Lactobacillus acetotolerans HT into different E. coli allows the improvement of LA monomer fraction (Goto et al. 2019b). Moreover, one-step production of the copolymers containing phenyllactate and 4-hydroxyphenyllactate from glucose by engineered E. coli XL1-Blue is designed. The globally metabolic engineering strategy of this one-step production of the copolymers includes the deletions of the ldhA, adhE, pflB, frdB, and poxB genes (Yang et al. 2018).

The cultivation of E. coli with mixed sugar will cause carbon catabolite repression, which can be derepressed by the overexpression of Mlc, a multiple regulator of glucose and xylose uptake. Engineered E. coli BW25113 can synthesize 64.9 wt% P(11.8 mol% LA-co-3HB) in a medium with 50 g/L mixed sugar (wt%, glucose:xylose = 4:1). In the same experiment, an increase in cell length is also observed, which is helpful for the accumulation of the copolymer (Kadoya et al. 2018).

Aim to change the copolymer production and the monomer composition, we can also disrupt σ factors, which globally govern the transcription of the corresponding genes. E. coli possesses four non-essential σ factors, RpoS, RpoN, FliA, and FecI. Engineered E. coli BW25113 along with the rpoN gene deletion can synthesize 75.1 wt% P(26.2 mol% LA-co-3HB) in a medium containing 20 g/L glucose, which is superior to that of the wild-type strain (Kadoya et al. 2015b). Furthermore, all of the deletions of non-lethal transcription factors of E. coli are screened by Keio Collection test. Among 252 mutants, eight of them, ΔpdhR, ΔcspG, ΔyneJ, ΔchbR, ΔyiaU, ΔcreB, ΔygfI, and ΔnanK, increase the copolymer yield (6.2–10.1 g/L) when compared to E. coli BW25113 (5.1 g/L) in a medium containing 30 g/L glucose with an insignificant change in cell density (Kadoya et al. 2017).

Attenuating respiratory chain increases the accumulation of LA in E. coli under aerobic conditions. The deletion of the flavin prenyltransferase gene (ubiX) can implement this strategy by attenuating the synthesis of coenzyme Q8, a key ingredient involved in respiratory chain in E. coli. Engineered E. coli MG1655 along with the dld gene deletion can synthesize 81.7 wt% P(14.1 mol% LA-co-3HB) in a medium containing 20 g/L glucose (Lu et al. 2019). On this basis, the Pct540Cp promoter is replaced with the ldhA promoter, and the glucose-specific PTS enzyme IIBC component gene (ptsG) is knocked out to weaken carbon catabolite repression. Engineered E. coli MG1655 can synthesize P(7 mol% LA-co-3HB) in a medium containing 10 g/L mixed sugar (wt%, glucose:xylose = 7:3), but LA monomer fraction is decreased compared with strain without the ptsG gene deletion (Wu et al. 2021). Another strategy is proposed by the same research group too, which is aimed to delete the thioesterase genes (ydiI and yciA) to prevent the degradation of intracellular LA-CoA. Engineered E. coli MG1655 along with the dld gene deletion can synthesize 66.3 wt% P(46.1 mol% LA-co-3HB) in a medium containing 20 g/L xylose. It should be pointed out that the lack of thioesterase plays a major regulatory role (Wei et al. 2021). The presence of LA-CoA degrading enzymes (LDEs) (such as thioesterase) may lead to extremely low intracellular LA-CoA content in E. coli, which accounts for the efficient copolymer production (Matsumoto et al. 2018). The deletion of similar enzymes may increase LA monomer fraction in the copolymers while preventing the extension of the copolymer chain (Matsumoto et al. 2018). Potential LDEs [such as possible short-chain fatty acyl-CoA degrading enzymes (Clomburg et al. 2012)] are promising as elements for regulating the copolymer composition.

Different culture conditions of E. coli for P(LA-co-3HB) biosynthesis

Introducing LPE and monomer synthesis enzymes into the pflA gene deleted E. coli BW25113, the copolymer in the mutant growing on 20 g/L xylose has a higher LA monomer fraction (34 mol%) than that growing on 20 g/L glucose (LA monomer fraction is 26 mol%). The utilization of evolved LPE (ST/FS/QK) can further enhance this advantage (Nduko et al. 2013). Introduction of the endoxylanase gene (xylB) of Streptomyces coelicolor and the β-xylosidase gene (xynB) of Bacillus subtilis into E. coli LS5218 allows converting xylan into PHA in vivo. Furthermore, when xylose or arabinose is added to the media at the same time, the production yields of PHA in engineered E. coli can increase up to 18-fold (Salamanca-Cardona et al. 2014b). Sucrose is undoubtedly one of the most abundant and the least expensive carbon sources. Engineered E. coli W can break down 20 g/L sucrose into fructose and glucose, and further to synthesize 12.2 wt% P(16 mol% LA-co-3HB) in vivo (Oh et al. 2014). To establish an efficient sucrose utilization pathway, the β-fructofuranosidase gene (sacC) of Mannheimia succiniciproducens MBEL55E is introduced into different genetically modified E. coli strains. Among the tested recombinant E. coli strains, engineered E. coli XL1-Blue synthesize the P(42.3 mol% LA-co-3HB) with the highest concentration of 0.576 g/L and a relatively high content of 29.44 wt% in a medium containing 20 g/L sucrose (Sohn et al. 2020).

Using traditional carbon sources such as glucose to produce the copolymers is a simple and effective method, but the copolymers’ increase in the production and the expansion of the use scope are inhibited by high raw material costs, so it is necessary to focus on the development of the inexpensive materials. By-products from different processing industries have great potentials, such as the residues of the biodiesel industry (Plácido and Capareda 2016), chitin and chitosan extracted from the marine waste resources (Yadav et al. 2019), the wastes of milk processing and reducing such as cheese whey (Zikmanis et al. 2020), lignocellulosic biomass and other green wastes (Langsdorf et al. 2021), as well as pulp and paper mill wastes (Haile et al. 2021). Some non-traditional carbon sources are not only beneficial to the copolymer production to a certain extent, but also can reduce the risk of the environmental pollution.

Rice bran is a by-product of the rice manufacturing process, and possesses certain potential as a feedstock for bio-based polymers. A rice bran treatment process has been developed to produce 43.7 kg hydrolysate solution containing 24.41 g/L glucose and a small amount of fructose from 5 kg rice bran (Oh et al. 2015). With the expression of LPE and monomer supplying enzymes, engineered E. coli XL1-Blue can synthesize 82.3 wt% P(28.6 mol% LA-co-3HB) in 10 mL/L hydrolysate solution; C. necator 437–540 can synthesize 35.8 wt% P(7.3 mol% LA-co-3HB) in the same condition (Oh et al. 2015).

P(LA-co-3HB) can be produced from glucose or xylose, which demonstrates the feasibility of using lignocellulosic-like biomass as a carbon source to produce P(LA-co-3HB). Wu et al. (2021) use corn stover hydrolysate to synthesize P(7.1 mol% LA-co-3HB) successfully, although cell growth is slightly inhibited. Compared with pure sugars, Sun et al. (2016) find that the hydrolysate solution derived from Miscanthus × giganteus (hybrid Miscanthus) does not affect content, yield, and LA monomer fraction of the copolymer, while the hydrolysate solution derived from rice straw decrease LA monomer fraction. However, some other researchers find that using the hydrolysate solution derived from hybrid Miscanthus will lead to a decrease in LA monomer fraction of the copolymer, which is suspected to be the effect of a small amount of acetate in the biomass sugar solution (Kadoya et al. 2018).

The hemicellulosic hydrolysate solution derived from dissolving pulp manufacturing-obtained woody extract is mainly composed of xylose and galactose, but a small amount of acetate contained in the hydrolysate solution will inhibit copolymer synthesis. After treating with active charcoal and ion-exchange columns to remove acetate, engineered E. coli BW25113 can synthesize 62.4 wt% P(5.5 mol% LA-co-3HB) in a medium containing the hydrolysate solution (Takisawa et al. 2017). The above conclusions all clarified the adverse effect of acetate on the copolymer production.

Although acetate inhibits copolymer synthesis, some acetate-tolerant strains are still discovered. The process of using engineered E. coli LS5218 along with the pflA gene deletion to produce the copolymers suggests that acetate played an important role in controlling LA monomer incorporation into the copolymers (Salamanca-Cardona et al. 2014a). Compared to using 20 g/L xylose alone, the overall yields of engineered E. coli LS5218 along with the pflA gene deletion increase by more than twofold with the presence of 25 mM acetate. In addition, when 25 mM acetate is used as the sole carbon source, the copolymer still can be synthesize by strain (Salamanca-Cardona et al. 2017).

High reducing power brought by anaerobic cultivation is beneficial to an increase in the flux toward LA-CoA. After a 24 h aerobic cultivation, engineered E. coli W3110 can synthesize 2 wt% P(47 mol% LA-co-3HB) when it is transferred into anaerobic conditions and is further cultured for another 24 h in a medium with 20 g/L glucose (Yamada et al. 2009). 12 wt% P(62 mol% LA-co-3HB) can be synthesized by combining anaerobic cultivation with engineered E. coli BW25113 along with the pflA gene deletion as well as carrying LPE of F392S mutant (Yamada et al. 2010). LA monomer fraction of the copolymers produced by engineered E. coli BW25113 along with the pflA gene deletion can be adjusted between the range from 29 to 47 mol% by the fine-regulation of the culture conditions in anaerobic cultivation with a medium containing 20 g/L glucose within a fermentation tank (Yamada et al. 2011). In addition, relatively anaerobic conditions (shaking speed = 0/60 strokes/min) can also increase LA monomer fraction in the copolymers (Goto et al. 2019b).

Fed-batch cultivation is an important technology to achieve high cell density and high volumetric productivity in a fermentation tank. By adjusting dissolved oxygen concentration (DOC) and glucose concentration (upon pH-stat feeding), LA monomer fraction can be adjusted between the range from 8.7 to 64.4 mol% by engineered E. coli XL1-Blue (Yang et al. 2010). Jung and Lee (2011) increase the weight percentage of P(LA-co-3HB) by fed-batch cultivation, but LA monomer fraction is decreased. The utilization of the pH-stat strategy or the pulsed-feeding strategy can produce aromatic PHAs to a reasonably high concentration (Yang et al. 2018). In addition, 20 g/L initial glucose concentration (0–24 h) is used for cell growth, and xylose (24–81.6 h) is used for the copolymer production, the feeding rate of the sugar solution is increased in a stepwise manner. Under this condition, engineered E. coli MG1655 can synthesize 44.3 wt% P(4.9 mol% LA-co-3HB) and the copolymer production increases significantly (Hori et al. 2019). Moreover, batch fermentation technology is used to overcome the bottleneck of the utilization of fructose, which is one of the components of rice bran (Oh et al. 2015)/sucrose (Sohn et al. 2020) hydrolysates. Compared with Pct540Cp, engineered E. coli XL1-Blue expressing PhaC1437Ps6-19 and BctEh in batch fermentation shows higher OD600 and weight percentage, but LA monomer fraction is lower (David et al. 2017).

Introduction of other monomers into lactate-based PHA

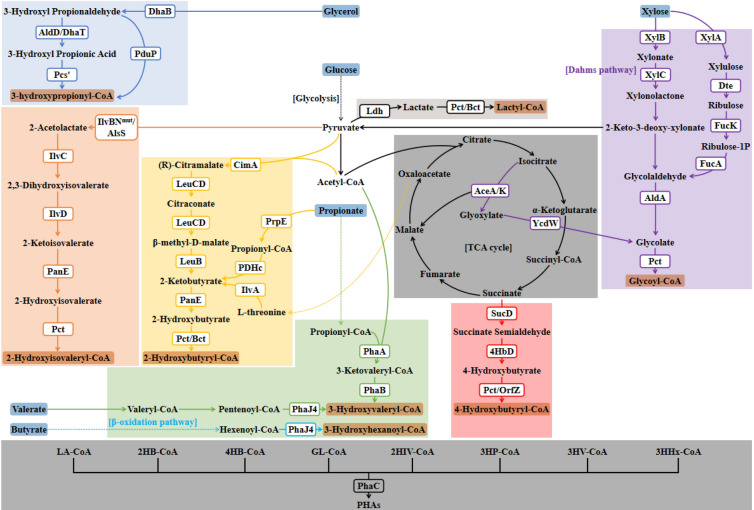

Engineered E. coli can synthesize LA-CoA by introducing Pct, synthesize 3HB-CoA by introducing PhaAB, and synthesize the copolymers by introducing LPE. Similarly, other monomers can be introduced into the copolymers by transforming the corresponding CoA metabolic pathway into E. coli. Alternatively, monomers can be added to the substrate directly and then use the one-pot method to produce the copolymers (Matsumoto et al. 2013). Different monomer copolymerization strategies are summarized in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Synthetic pathway of PHA with various compositions in recombinant E. coli. Dotted arrows represent simplified metabolic processes. Letters in boxes indicate enzymes. Pct propionyl-CoA transferase, Bct butyryl-CoA transferase, PhaA β-ketothiolase, PhaB NADPH-dependent acetoacetyl-CoA reductase, PhaC PHA synthase, Ldh lactate dehydrogenase, CimA citramalate synthase, LeuB 3-isopropylmalate dehydrogenase, LeuCD isopropyl malate (IPM) isomerase, PanE 2HB dehydrogenase, PrpE propionyl-CoA synthetase, PDHc pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, IlvA l-threonine dehydratase, SucD succinate semialdehyde dehydrogenase, 4HbD 4HB dehydrogenase, OrfZ CoA transferase, XylB xylose dehydrogenase, XylC xylonolactonase, AceA isocitrate lyase, AceK isocitrate dehydrogenase kinase/phosphatase, YcdW glyoxylate reductase, XylA xylose isomerase, Dte d-tagatose 3-epimerase, FucK ribulose kinase, FucA aldolase, AldA aldehyde dehydrogenase, IlvBNmut mutant acetolactate synthase, AlsS acetolactate synthase, IlvC ketol-acid reductoisomerase, IlvD dihydroxyacid dehydratase, DhaB glycerol dehydratase, DhaT 1,3-propanediol dehydrogenase, AldD aldehyde dehydrogenase, Pcs′ ACS domain of tri-functional propionyl-CoA synthetase, PduP propionaldehyde dehydrogenase, PhaJ4 (R)-specific enoyl-CoA hydratase 4

Introduction of 2HB biosynthesis pathway

The introduction of the citramalate synthase gene (cimA3.7) of Methanococcus jannaschii, the 3-isopropylmalate dehydrogenase gene (leuB) and the isopropyl malate (IPM) isomerase gene (leuCD) of E. coli W3110, as well as the 2HB dehydrogenase gene (panE) of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis Il1403 into E. coli XL1-Blue allows converting glucose into 2HB in vivo (Park et al. 2012b, 2013a; Chae et al. 2016; David et al. 2017). By introducing the propionyl-CoA synthetase gene (prpE) of C. necator and using the inherent pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDHc), E. coli XL1-Blue allows converting propionate into 2HB with the help of the panE gene in vivo. In addition, the deletion of the 2-methylcitrate synthase gene (prpC) can increase 2HB monomer fraction in the copolymers, while it will decrease the copolymer content (Park et al. 2013a). Moreover, E. coli can endogenously produce l-threonine, which can be transformed into 2HB with the help of the panE gene (Yang et al. 2016) or into 2HB-CoA with the help of the ldhA and hadA genes of C. difficile 630 (Mizuno et al. 2018; Sudo et al. 2020). The deletion of the l-threonine dehydratase gene (ilvA), will lead to the remove 2HB from the copolymers. However, since ilvA is the crucial gene for amino acid biosynthesis, the deletion of it in E. coli will result in the growth retardation and the decrease of the copolymer content. Considering the activity of l-threonine dehydratase can be inhibited allosterically by l-isoleucine, the same effect can be achieved by the strategy of adding l-isoleucine into the medium (Choi et al. 2016, 2017; Yang et al. 2016; Choi et al. 2020a). In order to increase 2HB monomer fraction, l-threonine can be added to the medium (Sudo et al. 2020). Furthermore, l-valine can also achieve the same effect, because the activity of acetohydroxy acid synthase is negatively regulated by l-valine (Yang et al. 2016; Sudo et al. 2020). In another explanation, l-valine is pointed out that allosterically activates l-threonine deaminase and catalyzes l-threonine to form 2-ketobutyrate (Sudo et al. 2020). Sudo et al. (2020) indicate that l-valine inhibits bacteria growth and leads to a decrease in the copolymer production, but this phenomenon is not discussed by Yang et al. (2016).

Introduction of 4HB biosynthesis pathway

The introduction of the succinate semialdehyde dehydrogenase gene (sucD), the 4HB dehydrogenase gene (4hbD), and the CoA transferase gene (orfZ) of Clostridium kluyveri DSM555 into E. coli JM109 allows converting glucose into 4HB-CoA in vivo (Li et al. 2017). With the introduction of the sucD and 4hbD genes into E. coli XL1-Blue and with the help of Pct540Cp, the E. coli mutant also allows converting glucose into 4HB-CoA in vivo (Choi et al. 2016, 2020a). In addition, the deletion of the succinate semialdehyde dehydrogenase genes (sad and gabD) can increase 4HB monomer fraction in the copolymers (Li et al. 2017). In another study, deleting the yneI and gabD genes, which coding succinate semialdehyde dehydrogenase too, can also increase 4HB monomer fraction in the copolymers (Choi et al. 2016, 2020a).

Introduction of glycolate (GL) biosynthesis pathway

In 2011, the copolymers containing GL were synthesized in E. coli LS5218 for the first time with exogenous GL (Matsumoto et al. 2011). Subsequently, the methods for providing endogenous GL by modulating the metabolic pathway were established gradually. Establishing the Dahms pathway (XylBCccs) in E. coli XL1-Blue by introducing of the xylose dehydrogenase gene (xylB) and the xylonolactonase gene (xylC) of Caulobacter crescentus allows converting xylose into GL in vivo (Choi et al. 2016, 2017, 2020a). The native glyoxylate bypass pathway of E. coli is amplified by the overexpression of the isocitrate lyase gene (aceA), the isocitrate dehydrogenase kinase/phosphatase gene (aceK), and the glyoxylate reductase gene (ycdW), which allows converting glucose into GL in vivo. The deletion of the glycolate oxidase gene (glcD) can increase GL monomer fraction in the copolymers (Li et al. 2016, 2017). The introduction of the d-tagatose 3-epimerase gene (dte) of Pseudomonas cichorii and the overexpression of the native genes [the ribulose kinase gene (fucK), the aldolase gene (fucA), and the aldehyde dehydrogenase gene (aldA)] in E. coli K12 also allow converting xylose into GL in vivo (Da et al. 2019).

Introduction of other 2-hydroxyalkanoates (2HA) biosynthesis pathway

The introduction of the mutant acetolactate synthase gene (ilvBNmut) [or the B. subtilis acetolactate synthase gene (alsS)], the ketol-acid reductoisomerase gene (ilvC), and the dihydroxyacid dehydratase gene (ilvD) of E. coli W3110 into E. coli XL1-Blue allows converting glucose into 2-hydroxyisovalerate (2HIV) with the help of the panE gene in vivo. In addition, adding l-valine into the medium can also increase 2HIV monomer fraction in the copolymers (Choi et al. 2016; Yang et al. 2016). The introduction of the ldhA and hadA genes into E. coli DH5α allows converting glucose/xylose/glycerol into 2HA-CoA (2HP, 2H3MB, 2H3MV, 2H4MV, and 2H3PhP) with the supplement of different amino acids in vivo (Mizuno et al. 2018).

Introduction of 3‐hydroxypropionate (3HP) biosynthesis pathway

The introduction of the glycerol dehydratase gene (dhaB) of Klebsiella pneumoniae, the 1,3-propanediol dehydrogenase gene (dhaT) and the aldehyde dehydrogenase gene (aldD) of P. putida KT2442, as well as the ACS domain of tri-functional propionyl-CoA synthetase gene (pcs′) of Chloroflexus aurantiacus into E. coli S17-1 allows converting glycerol into 3HP-CoA in vivo (Ren et al. 2017). The introduction of the glycerol dehydratase gene (dhaB123) of K. pneumoniae and the propionaldehyde dehydrogenase gene (pduP) of Salmonella typhimurium LT2 into E. coli JM109 also allows converting glycerol into 3HP-CoA in vivo (Zhao et al. 2018).

Introduction of 3HV and medium-chain-length 3-hydroxyalkanoates (3HA) biosynthesis pathway

Using E. coli BW25113 along with the pflA gene deletion, 3HV-CoA can be supplied from propionate, which is esterified into propionyl-CoA by proposed inherent pathways (such as acetyl-CoA synthetase and propionyl-CoA synthetase) firstly. Then, Propionyl-CoA is converted into 3HV-CoA by PhaAB (Shozui et al. 2010b). The introduction of the (R)-specific enoyl-CoA hydratase 4 gene (phaJ4) of P. aeruginosa into E. coli LS5218 allows converting valerate into 3HV-CoA in vivo with the help of the β-oxidation pathway (Shozui et al. 2011). In addition, with the same strategies (using the phaJ4 gene and the β-oxidation pathway together), E. coli LS5218 can polymerize 3HHx into the copolymers from butyrate (Shozui et al. 2010a) and polymerize 3HA (3HB, 3HHx, 3HO, 3HD, and 3HDD) into the copolymers from dodecanoate (Matsumoto et al. 2011). Moreover, the introduction of enzymes for the synthesis of 3HA monomers with medium-chain length into the fadR gene deleted E. coli allows converting glucose into 3HA (3HB, 3HO, 3HD, 3HDD, and 3H5DD) in vivo (Goto et al. 2019a).

Microorganisms other than E. coli for P(LA-co-3HB) biosynthesis

Due to the relatively mature metabolic regulation mechanism and molecular tools, E. coli is the most widely used chassis cell in the copolymer production. While in recent years, some other non-traditional chassis cells also have been developed and applied.

As an endotoxin-free platform, a Gram-positive bacteria Corynebacterium glutamicum is metabolic engineered to produce the copolymers. After introducing LPE and monomer supplying enzymes, 2.4 wt% P(96.8 mol% LA-co-3HB) is synthesized by engineered strain in a medium with 60 g/L glucose. LA monomer fraction is further increased to 99.3 mol% after the phaAB gene deletion, while the copolymer content is decreased to 1.4 wt% (Song et al. 2012).

Cupriavidus necator is one of the most effective platforms for producing various PHAs. With the expression of LPE and monomer supplying enzymes, C. necator 437–540 can synthesize 33.9 wt% P(37 mol% LA-co-3HB) in a medium containing 20 g/L glucose. Furthermore, 2HB and 3HV can be polymerized into the copolymers by this strain when 2HB is added to the medium (Park et al. 2013b). Introducing the sacC and ldhA genes into C. necator 437–540 can synthesize 19.5 wt% P(21.5 mol% LA-co-3HB) in a medium with 20 g/L sucrose (Park et al. 2015).

Considering the higher production efficiency and the lower cost of the copolymers, Sinorhizobium meliloti is selected as a production platform. Pct532Cp and PhaC1400Ps6-19 are introduced into S. meliloti Rm1021 and the native PHA synthase enzyme gene (phbC) is replaced. Under the control of the native phbC promoter, engineered strain can synthesize P(30 mol% LA-co-3HB) in a medium containing mannitol. This is the first report of the copolymer production in Alphaproteobacteria (Tran and Charles 2016).

Conclusions

Due to the rising price of crude oil, the depletion of petroleum resources, and the environmental damage caused by plastic wastes, PLA and its copolymers have become the potential substitutes for the degradable synthetic plastics and the “green copolymers” made from renewable resources. Therefore, they have attracted more and more attention in the fields of industry, medicine, and research. The researches of the lactate-based copolymers, which possess broad application prospects, not only greatly improve the properties of PLA, but also greatly expand the application field of it.

It has become a trend to utilize inexpensive extraneous carbon sources (such as glucose and glycerol) and/or mixed cultures (such as agricultural wastes) in the production. Recombinant E. coli has been developed as a conventional platform to produce the copolymers (Choi et al. 2020b). The strategies of the copolymer production are generally to overcome the shortcomings of inducible promoters and/or introduce new key enzymes. Because of the ability of E. coli to use a variety of cheap and unrelated carbon sources, the large-scale bioreactors production from the culture in shake flasks should be further studied to obtain a more efficient fermentation process. In addition, the separation and the purification of the copolymers from E. coli is also one of the research directions.

With the further development of the potential recombinant E. coli strains and other related strains, it is not only helpful to expand the production types of the copolymers but also can improve the productivity and the yield of the copolymers, making copolymer recycling more convenient and economical. In order to replace the plastics derived from the petrochemical industry ideally, more researches should be conducted on reducing the production costs and improving the properties of bioplastics.

Acknowledgements

The National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 21776083), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2017YFB0309302), the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (Grant No. 21DZ1209100), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. 22221818014), the 111 Project (B18022).

Abbreviations

- PLA

Polylactic acid

- LA

Lactate

- P(LA-co-3HB)

Poly(lactate-co-3-hydroxybutyrate)

- PHA

Polyhydroxyalkanoate

- Ldh

Lactate dehydrogenase

- Pct

Propionyl-CoA transferase

- PhaA

β-Ketothiolase

- PhaB

NADPH-dependent acetoacetyl-CoA reductase

- PhaC

PHA synthase

- 3HB

3-Hydroxybutyrate

- P(3HB)

Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate)

- 3HV

3-Hydroxyvalerate

- 4HB

4-Hydroxybutyrate

- LPE

LA-CoA polymerizing enzyme

- 2HB

2-Hydroxybutyrate

- Bct

Butyryl-CoA transferase

- FldA

Cinnamoyl-CoA:phenyllactate CoA-transferase

- HadA

Isocaprenoyl-CoA:2-hydroxyisocaproate CoA-transferase

- GatC

Non-ATP consuming galactitol permease

- PflB

Pyruvate formate lyase

- PflA

Pyruvate formate lyase activating enzyme

- Mlc

Multiple regulator of glucose and xylose uptake

- LDE

LA-CoA degrading enzyme

- DOC

Dissolved oxygen concentration

- CimA

Citramalate synthase

- LeuB

3-Isopropylmalate dehydrogenase

- LeuCD

Isopropyl malate isomerase

- IPM

Isopropyl malate

- PanE

2HB dehydrogenase

- PrpE

Propionyl-CoA synthetase

- PDHc

Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex

- IlvA

l-Threonine dehydratase

- SucD

Succinate semialdehyde dehydrogenase

- 4HbD

4-Hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase

- OrfZ

CoA transferase

- XylB

Xylose dehydrogenase

- XylC

Xylonolactonase

- AceA

Isocitrate lyase

- AceK

Isocitrate dehydrogenase kinase/phosphatase

- YcdW

Glyoxylate reductase

- XylA

Xylose isomerase

- Dte

d-Tagatose 3-epimerase

- FucK

Ribulose kinase

- FucA

Aldolase

- AldA

Aldehyde dehydrogenase

- IlvBNmut

Mutant acetolactate synthase

- AlsS

Acetolactate synthase

- IlvC

Ketol-acid reductoisomerase

- IlvD

Dihydroxyacid dehydratase

- DhaB

Glycerol dehydratase

- DhaT

1,3-Propanediol dehydrogenase

- AldD

Aldehyde dehydrogenase

- Pcs′

ACS domain of tri-functional propionyl-CoA synthetase

- PduP

Propionaldehyde dehydrogenase

- PhaJ4

(R)-Specific enoyl-CoA hydratase 4

- GL

Glycolate

- 2HA

2-Hydroxyalkanoate

- 2HIV

2-Hydroxyisovalerate

- 2HP

2‐Hydroxypropionate

- 2H3MB

2-Hydroxy-3-methylbutyrate

- 2H3MV

2-Hydroxy-3-methylvalerate

- 2H4MV

2-Hydroxy-4-methylvalerate

- 2H3PhP

2-Hydroxy-3-phenylpropionate

- 3HP

3‐Hydroxypropionate

- 3HA

3-Hydroxyalkanoate

- 3HHx

3-Hydroxyhexanoate

- 3HO

3-Hydroxyoctanoate

- 3HD

3-Hydroxydecanoate

- 3HDD

3-Hydroxydodecanoate

- 3H5DD

3-Hydroxy-5-cis-dodecenoate

Authors’ contributions

PG, YL and HW conceived and designed the review. PG, YL and HW wrote the paper. JW revised the paper. HW supervised the paper and has funding acquisition. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 21776083), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2017YFB0309302), the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (Grant No. 21DZ1209100), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. 22221818014), the 111 Project (B18022).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All authors read and approved the final manuscript and related ethics.

Consent for publication

All authors read and approved the final manuscript and potential publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Pengye Guo and Yuanchan Luo contributed equally to this work

References

- Chae CG, Kim YJ, Lee SJ, Oh YH, Yang JE, Joo JC, Kang KH, Jang Y-A, Lee H, Park AR, Song BK, Lee SY, Park SJ. Biosynthesis of poly(2-hydroxybutyrate-co-lactate) in metabolically engineered Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Bioprocess Eng. 2016;21(1):169–174. doi: 10.1007/s12257-015-0749-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SY, Park SJ, Kim WJ, Yang JE, Lee H, Shin J, Lee SY. One-step fermentative production of poly(lactate-co-glycolate) from carbohydrates in Escherichia coli. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34(4):435–440. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SY, Kim WJ, Yu SJ, Park SJ, Im SG, Lee SY. Engineering the xylose-catabolizing Dahms pathway for production of poly(d-lactate-co-glycolate) and poly(d-lactate-co-glycolate-co-d-2-hydroxybutyrate) in Escherichia coli. Microb Biotechnol. 2017;10(6):1353–1364. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SY, Chae TU, Shin J, Im JA, Lee SY. Biosynthesis and characterization of poly(d-lactate-co-glycolate-co-4-hydroxybutyrate) Biotechnol Bioeng. 2020;117(7):2187–2197. doi: 10.1002/bit.27354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SY, Rhie MN, Kim HT, Joo JC, Cho IJ, Son J, Jo SY, Sohn YJ, Baritugo KA, Pyo J, Lee Y, Lee SY, Park SJ. Metabolic engineering for the synthesis of polyesters: a 100-year journey from polyhydroxyalkanoates to non-natural microbial polyesters. Metab Eng. 2020;58:47–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2019.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clomburg JM, Vick JE, Blankschien MD, Rodriguez-Moya M, Gonzalez R. A synthetic biology approach to engineer a functional reversal of the β-oxidation cycle. ACS Synth Biol. 2012;1(11):541–554. doi: 10.1021/sb3000782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Y, Li W, Shi L, Li Z. Microbial production of poly (glycolate-co-lactate-co-3-hydroxybutyrate) from glucose and xylose by Escherichia coli. Chin J Biotechnol. 2019;35(2):254–262. doi: 10.13345/j.cjb.180199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David Y, Joo JC, Yang JE, Oh YH, Lee SY, Park SJ. Biosynthesis of 2-hydroxyacid-containing polyhydroxyalkanoates by employing butyryl-CoA transferases in metabolically engineered Escherichia coli. Biotechnol J. 2017;12(11):1700116. doi: 10.1002/biot.201700116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giammona G, Craparo EF. Biomedical applications of polylactide (PLA) and its copolymers. Molecules. 2018 doi: 10.3390/molecules23040980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto S, Hokamura A, Shiratsuchi H, Taguchi S, Matsumoto K, Abe H, Tanaka K, Matsusaki H. Biosynthesis of novel lactate-based polymers containing medium-chain-length 3-hydroxyalkanoates by recombinant Escherichia coli strains from glucose. J Biosci Bioeng. 2019;128(2):191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2019.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto S, Suzuki N, Matsumoto K, Taguchi S, Tanaka K, Matsusaki H. Enhancement of lactate fraction in poly(lactate-co-3-hydroxybutyrate) synthesized by Escherichia coli harboring the d-lactate dehydrogenase gene from Lactobacillus acetotolerans HT. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 2019;65(4):204–208. doi: 10.2323/jgam.2018.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haile A, Gelebo GG, Tesfaye T, Mengie W, Mebrate MA, Abuhay A, Limeneh DY. Pulp and paper mill wastes: utilizations and prospects for high value-added biomaterials. Bioresour Bioprocess. 2021;8(1):1–22. doi: 10.1186/s40643-021-00385-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X, Satoh Y, Satoh T, Matsumoto K, Kakuchi T, Taguchi S, Dairi T, Munekata M, Tajima K. Chemo-enzymatic synthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) incorporating 2-hydroxybutyrate by wild-type class I PHA synthase from Ralstonia eutropha. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;92(3):509–517. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3362-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori C, Yamazaki T, Ribordy G, Takisawa K, Matsumoto K, Ooi T, Zinn M, Taguchi S. High-cell density culture of poly(lactate-co-3-hydroxybutyrate)-producing Escherichia coli by using glucose/xylose-switching fed-batch jar fermentation. J Biosci Bioeng. 2019;127(6):721–725. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2018.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii D, Takisawa K, Matsumoto K, Ooi T, Hikima T, Takata M, Taguchi S, Iwata T. Effect of monomeric composition on the thermal, mechanical and crystalline properties of poly[(R)-lactate-co-(R)-3-hydroxybutyrate] Polymer. 2017;122:169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2017.06.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z, Zhang J. Lipase-catalyzed synthesis of aliphatic polyesters via copolymerization of lactide with diesters and diols. Polymer. 2013;54(22):6105–6113. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2013.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jung YK, Lee SY. Efficient production of polylactic acid and its copolymers by metabolically engineered Escherichia coli. J Biotechnol. 2011;151(1):94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung YK, Kim TY, Park SJ, Lee SY. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for the production of polylactic acid and its copolymers. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2010;105(1):161–171. doi: 10.1002/bit.22548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadoya R, Matsumoto K, Ooi T, Taguchi S. MtgA deletion-triggered cell enlargement of Escherichia coli for enhanced intracellular polyester accumulation. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(6):e0125163. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadoya R, Kodama Y, Matsumoto K, Taguchi S. Enhanced cellular content and lactate fraction of the poly(lactate-co-3-hydroxybutyrate) polyester produced in recombinant Escherichia coli by the deletion of sigma factor RpoN. J Biosci Bioeng. 2015;119(4):427–429. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadoya R, Kodama Y, Matsumoto K, Ooi T, Taguchi S. Genome-wide screening of transcription factor deletion targets in Escherichia coli for enhanced production of lactate-based polyesters. J Biosci Bioeng. 2017;123(5):535–539. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2016.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadoya R, Matsumoto K, Takisawa K, Ooi T, Taguchi S. Enhanced production of lactate-based polyesters in Escherichia coli from a mixture of glucose and xylose by Mlc-mediated catabolite derepression. J Biosci Bioeng. 2018;125(4):365–370. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2017.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YJ, Chae CG, Kang KH, Oh YH, Joo JC, Song BK, Lee SY, Park SJ. Biosynthesis of lactate-containing polyhydroxyalkanoates in Recombinant Escherichia coli by employing new CoA transferases. KSBB J. 2016;31(1):27–32. doi: 10.7841/ksbbj.2016.31.1.27. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Langsdorf A, Volkmar M, Holtmann D, Ulber R. Material utilization of green waste: a review on potential valorization methods. Bioresour Bioprocess. 2021;8(1):1–26. doi: 10.1186/s40643-021-00367-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Cho IJ, Choi SY, Lee SY. Systems metabolic engineering strategies for non-natural microbial polyester production. Biotechnol J. 2019;14(9):e1800426. doi: 10.1002/biot.201800426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li ZJ, Qiao K, Shi W, Pereira B, Zhang H, Olsen BD, Stephanopoulos G. Biosynthesis of poly(glycolate-co-lactate-co-3-hydroxybutyrate) from glucose by metabolically engineered Escherichia coli. Metab Eng. 2016;35:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li ZJ, Qiao K, Che XM, Stephanopoulos G. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for the synthesis of the quadripolymer poly(glycolate-co-lactate-co-3-hydroxybutyrate-co-4-hydroxybutyrate) from glucose. Metab Eng. 2017;44:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Li Z, Ye Q, Wu H. Effect of reducing the activity of respiratory chain on biosynthesis of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-lactate) in Escherichia coli. Chin J Biotechnol. 2019;35(1):59–69. doi: 10.13345/j.cjb.180107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makadia HK, Siegel SJ. Poly lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) as biodegradable controlled drug delivery carrier. Polymers. 2011;3(3):1377–1397. doi: 10.3390/polym3031377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto K, Taguchi S. Enzymatic and whole-cell synthesis of lactate-containing polyesters: toward the complete biological production of polylactate. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;85(4):921–932. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2374-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto K, Taguchi S. Biosynthetic polyesters consisting of 2-hydroxyalkanoic acids: current challenges and unresolved questions. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97(18):8011–8021. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5120-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto K, Taguchi S. Enzyme and metabolic engineering for the production of novel biopolymers: crossover of biological and chemical processes. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2013;24(6):1054–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2013.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto K, Ishiyama A, Sakai K, Shiba T, Taguchi S. Biosynthesis of glycolate-based polyesters containing medium-chain-length 3-hydroxyalkanoates in recombinant Escherichia coli expressing engineered polyhydroxyalkanoate synthase. J Biotechnol. 2011;156(3):214–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2011.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto K, Terai S, Ishiyama A, Sun J, Kabe T, Song Y, Nduko JM, Iwata T, Taguchi S. One-pot microbial production, mechanical properties, and enzymatic degradation of isotactic P[(R)-2-hydroxybutyrate] and its copolymer with (R)-lactate. Biomacromolecules. 2013;14(6):1913–1918. doi: 10.1021/bm400278j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto K, Iijima M, Hori C, Utsunomia C, Ooi T, Taguchi S. In vitro analysis of d-lactyl-CoA-polymerizing polyhydroxyalkanoate synthase in polylactate and poly(lactate-co-3-hydroxybutyrate) syntheses. Biomacromolecules. 2018;19(7):2889–2895. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.8b00454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno S, Enda Y, Saika A, Hiroe A, Tsuge T. Biosynthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoates containing 2-hydroxy-4-methylvalerate and 2-hydroxy-3-phenylpropionate units from a related or unrelated carbon source. J Biosci Bioeng. 2018;125(3):295–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2017.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nduko JM, Taguchi S. Microbial production and properties of LA-based polymers and oligomers from renewable feedstock. In: Fang Z, Smith JRL, Tian X-F, editors. Production of materials from sustainable biomass resources. Singapore: Springer; 2019. pp. 361–390. [Google Scholar]

- Nduko JM, Matsumoto K, Ooi T, Taguchi S. Effectiveness of xylose utilization for high yield production of lactate-enriched P(lactate-co-3-hydroxybutyrate) using a lactate-overproducing strain of Escherichia coli and an evolved lactate-polymerizing enzyme. Metab Eng. 2013;15:159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nduko JM, Matsumoto K, Ooi T, Taguchi S. Enhanced production of poly(lactate-co-3-hydroxybutyrate) from xylose in engineered Escherichia coli overexpressing a galactitol transporter. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98(6):2453–2460. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5401-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochi A, Matsumoto K, Ooba T, Sakai K, Tsuge T, Taguchi S. Engineering of class I lactate-polymerizing polyhydroxyalkanoate synthases from Ralstonia eutropha that synthesize lactate-based polyester with a block nature. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97(8):3441–3447. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4231-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh YH, Kang K-H, Shin J, Song BK, Lee SH, Lee SY, Park SJ. Biosynthesis of lactate-containing polyhydroxyalkanoates in recombinant Escherichia coli from sucrose. KSBB J. 2014;29(6):443–447. doi: 10.7841/ksbbj.2014.29.6.443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oh YH, Lee SH, Jang YA, Choi JW, Hong KS, Yu JH, Shin J, Song BK, Mastan SG, David Y, Baylon MG, Lee SY, Park SJ. Development of rice bran treatment process and its use for the synthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoates from rice bran hydrolysate solution. Bioresour Technol. 2015;181:283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.01.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang X, Zhuang X, Tang Z, Chen X. Polylactic acid (PLA): research, development and industrialization. Biotechnol J. 2010;5(11):1125–1136. doi: 10.1002/biot.201000135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SJ, Lee SY, Kim TW, Jung YK, Yang TH. Biosynthesis of lactate-containing polyesters by metabolically engineered bacteria. Biotechnol J. 2012;7(2):199–212. doi: 10.1002/biot.201100070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SJ, Lee TW, Lim SC, Kim TW, Lee H, Kim MK, Lee SH, Song BK, Lee SY. Biosynthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoates containing 2-hydroxybutyrate from unrelated carbon source by metabolically engineered Escherichia coli. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;93(1):273–283. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3530-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SJ, Kang KH, Lee H, Park AR, Yang JE, Oh YH, Song BK, Jegal J, Lee SH, Lee SY. Propionyl-CoA dependent biosynthesis of 2-hydroxybutyrate containing polyhydroxyalkanoates in metabolically engineered Escherichia coli. J Biotechnol. 2013;165(2):93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SJ, Jang YA, Lee H, Park AR, Yang JE, Shin J, Oh YH, Song BK, Jegal J, Lee SH, Lee SY. Metabolic engineering of Ralstonia eutropha for the biosynthesis of 2-hydroxyacid-containing polyhydroxyalkanoates. Metab Eng. 2013;20:20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SJ, Jang YA, Noh W, Oh YH, Lee H, David Y, Baylon MG, Shin J, Yang JE, Choi SY, Lee SH, Lee SY. Metabolic engineering of Ralstonia eutropha for the production of polyhydroxyalkanoates from sucrose. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2015;112(3):638–643. doi: 10.1002/bit.25469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plácido J, Capareda S. Conversion of residues and by-products from the biodiesel industry into value-added products. Bioresour Bioprocess. 2016;3(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s40643-016-0100-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Y, Meng D, Wu L, Chen J, Wu Q, Chen GQ. Microbial synthesis of a novel terpolyester P(LA-co-3HB-co-3HP) from low-cost substrates. Microb Biotechnol. 2017;10(2):371–380. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salamanca-Cardona L, Scheel RA, Lundgren BR, Stipanovic AJ, Matsumoto K, Taguchi S, Nomura CT. Deletion of the pflA gene in Escherichia coli LS5218 and its effects on the production of polyhydroxyalkanoates using beechwood xylan as a feedstock. Bioengineered. 2014;5(5):284–287. doi: 10.4161/bioe.29595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salamanca-Cardona L, Ashe CS, Stipanovic AJ, Nomura CT. Enhanced production of polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) from beechwood xylan by recombinant Escherichia coli. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98(2):831–842. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5398-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salamanca-Cardona L, Scheel RA, Mizuno K, Bergey NS, Stipanovic AJ, Matsumoto K, Taguchi S, Nomura CT. Effect of acetate as a co-feedstock on the production of poly(lactate-co-3-hydroxyalkanoate) by pflA-deficient Escherichia coli RSC10. J Biosci Bioeng. 2017;123(5):547–554. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2016.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah AA, Kato S, Shintani N, Kamini NR, Nakajima-Kambe T. Microbial degradation of aliphatic and aliphatic-aromatic co-polyesters. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98(8):3437–3447. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5558-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shozui F, Matsumoto K, Sasaki T, Taguchi S. Engineering of polyhydroxyalkanoate synthase by Ser477X/Gln481X saturation mutagenesis for efficient production of 3-hydroxybutyrate-based copolyesters. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;84(6):1117–1124. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shozui F, Matsumoto K, Motohashi R, Yamada M, Taguchi S. Establishment of a metabolic pathway to introduce the 3-hydroxyhexanoate unit into LA-based polyesters via a reverse reaction of β-oxidation in Escherichia coli LS5218. Polym Degrad Stab. 2010;95(8):1340–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2010.01.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shozui F, Matsumoto K, Nakai T, Yamada M, Taguchi S. Biosynthesis of novel terpolymers poly(lactate-co-3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate)s in lactate-overproducing mutant Escherichia coli JW0885 by feeding propionate as a precursor of 3-hydroxyvalerate. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;85(4):949–954. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2100-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]