Abstract

Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) is a pervasive environmental toxicant used in the manufacturing of numerous consumer products, medical supplies, and building materials. DEHP is metabolized to mono(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (MEHP). MEHP is an endocrine disruptor that adversely affects folliculogenesis and steroidogenesis in the ovary, but its mechanism of action is not fully understood. Thus, we tested the hypothesis that the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) plays a functional role in MEHP-mediated disruption of folliculogenesis and steroidogenesis. CD-1 mouse antral follicles were isolated and cultured with MEHP (0–400 μM) in the presence or absence of the AHR antagonist CH223191 (1 μM). MEHP treatment reduced follicle growth over a 96-h period, and this effect was partially rescued by co-culture with CH223191. MEHP exposure alone increased expression of known AHR targets, cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes Cyp1a1 and Cyp1b1, and this induction was blocked by CH223191. MEHP reduced media concentrations of estrone and estradiol compared to control. This effect was mitigated by co-culture with CH223191. Moreover, MEHP reduced the expression of the estrogen-sensitive genes progesterone receptor (Pgr) and luteinizing hormone/choriogonadotropin receptor (Lhcgr) and co-treatment with CH223191 blocked this effect. Collectively, these data indicate that MEHP activates the AHR to impair follicle growth and reduce estrogen production and signaling in ovarian antral follicles.

Keywords: ovary, phthalates, aryl hydrocarbon receptor, steroidogenesis

Mono(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate impairs follicle growth and estrogen production through activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor.

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

Female fertility requires healthy folliculogenesis to give rise to oocytes for subsequent fertilization and healthy steroidogenesis to produce sex steroid hormones including progesterone, androgens, and estrogens [1]. Dysregulation of folliculogenesis and steroidogenesis can have profound negative effects on reproduction. It is well documented that exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals in the environment and consumer products can give rise to infertility [1–5]. These endocrine-disrupting chemicals interfere with numerous facets of the hypothalamic/pituitary/ovarian axis to negatively impact ovarian function [6–8].

Phthalates are a group of chemicals that act as endocrine disruptors. They are plasticizers commonly found in building materials, personal care products, toys, plastic packaging, and medical devices [9]. Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) is one of the most commonly used phthalates, and its ability to leach out of products makes it a pervasive environmental contaminant [9]. Human exposure can occur through multiple routes, including inhalation, ingestion, and dermal contact [9]. The estimated average daily intake of DEHP ranges from 3 to 30 μg/kg, and even higher exposure ranges are estimated for young children and patients receiving blood transfusions or hemodialysis [10]. DEHP exposure is linked to reproductive toxicity, including disrupted folliculogenesis, impaired steroidogenesis, altered estrous cyclicity, reduced fertility, and accelerated reproductive aging [11–13].

In vivo, DEHP is rapidly hydrolyzed to form the active metabolite mono(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (MEHP) [14]. Moreover, DEHP can be metabolized to MEHP within the ovary [15]. In vitro experiments using rodent antral follicles and cultured granulosa cells demonstrate that, like exposure to its parent compound, MEHP exposure is associated with effects characteristic of reproductive toxicity, including altered expression of steroidogenic enzymes and hormone synthesis, impaired follicle growth, increased oxidative stress, and follicle atresia [16–21].

Although MEHP shows clear toxic effects on ovarian physiology, the molecular pathways that are recruited in mediating ovarian toxicity are unclear. Recent studies have demonstrated that phthalates, such as DEHP and its metabolite MEHP, activate the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) in multiple tissue/cell types, including hepatocellular carcinoma cells, glial cells, uterine leiomyoma cells, and lung tissue [22–25]. However, it is unknown whether phthalates affect AHR activity in the ovary. Thus, we examined the AHR as a potential mediator of MEHP toxicity in ovarian antral follicles. The AHR is a transcription factor that regulates expression of xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes in response to dioxins, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, phytochemicals, and endogenous ligands [26]. Specifically, the AHR regulates expression of the cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes CYP1A1 and CYP1B1, which initiate the transformation of potent estrogens into less active estrogen metabolites to be excreted from the body [27]. In addition, the AHR exhibits negative crosstalk with the estrogen receptor (ER) to reduce estrogen-mediated ER signaling [26, 28]. The AHR is expressed in multiple ovarian follicular cell types, including the oocytes, theca, and granulosa cells that make up the functional unit of the ovary [29]. The AHR has been shown to play a crucial role in ovarian development, whereas AHR hyperactivation by potent ligands, such as 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin, can impair ovarian function [30, 31]. Together, these observations make the AHR a compelling target for endocrine-disrupting environmental chemicals, including phthalates and phthalate metabolites.

In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that the AHR plays a functional role in MEHP-mediated disruption of folliculogenesis and steroidogenesis. To test this hypothesis, we measured the effects of MEHP on antral follicle growth, AHR transcriptional activity, estrogen synthesis, and estrogen signaling in vitro in the presence of the AHR antagonist CH223191.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

MEHP (99% purity) was purchased from AccuStandard. Stock solutions of MEHP were prepared using dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) (Sigma-Aldrich) and diluted in culture media to final concentrations of 0.4, 4, 40, and 400 μM, respectively, allowing for equal volumes of vehicle to be added per treatment (0.375 μl MEHP/ml culture media). The AHR antagonist CH223191 (CH) was purchased from APExBIO. A stock solution of 133 mM was prepared using DMSO and added to all treatments containing CH223191 (+CH) to a final CH concentration of 1 μM (0.375 μl CH/ml of MEHP treatment). The selected concentration of CH223191 was based on a previous study [23] and was determined not to adversely affect follicle growth or morphology in preliminary studies. In the absence of MEHP and/or CH223191 in treatment groups, an equivalent volume of DMSO was added to ensure each treatment group contained the same volume of vehicle (0.75 μl DMSO/ml).

Animals

CD-1 mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratories and housed at the College of Veterinary Medicine Animal Facility at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Animals were maintained in a controlled environment (22 ± 1°C, 12 h light:12 h dark cycles) and were provided food and water ad libitum. The Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign approved all procedures involving animal care, euthanasia, and tissue collection.

In vitro antral follicle cultures and analysis of follicle growth

Female CD-1 mice (aged 32–42 days) were euthanized, and their ovaries were aseptically removed and washed. Watchmaker’s forceps were used to open the ovarian bursa and separate the ovarian follicles from the interstitial tissue. Antral follicles were determined based on size (250–400 μM). Experiments were conducted using antral follicles isolated from 4 to 5 mice per isolation. Antral follicles were pooled and randomly plated in individual wells of a 96-well plate. Follicles were cultured in alpha-minimal essential medium (α-MEM; Gibco) supplemented with 10 mg/L insulin, 5.5 mg/L transferrin, and 5.5 μg/L selenium (ITS; Sigma-Aldrich), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 mg/ml streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich), 5 IU/ml human recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH; Dr. A.F. Parlow, National Hormone and Peptide Program), and 5% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals). Stock solutions of MEHP and CH223191 were diluted in the supplemented culture media to yield the final treatment concentrations, as described above. An equal volume of DMSO was added to the control group treatment media. The final volume of DMSO per treatment was 0.075% of the total treatment volume. Follicles were cultured in the indicated treatment for 96 h at 37°C and 5% CO2 (8–12 follicles per treatment group; n = 6 separate cultures).

During the culture period, follicle growth was evaluated every 24 h using an inverted microscope equipped with a calibrated ocular micrometer. Follicle diameter was measured on perpendicular axes. Follicle diameter measurements were averaged and presented as a percentage of the initial average follicle size of the respective treatment at the start of the culture.

At the end of the treatment period, follicles were collected, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C for gene expression analysis. Media were also collected and stored at −80°C for measurement of sex steroid hormones.

Analysis of gene expression

Total RNA was isolated from follicles using the RNeasy Micro kit (Qiagen, Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA concentration was measured using the NanoDrop ND 1000 (NanoDrop Technologies Inc.). RNA (100 ng) was reverse transcribed to cDNA using the iScript RT kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Resulting cDNA was subjected to quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis using specific primers (Integrated DNA Technologies; Table 1). Quantitative PCR was performed using the SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad) and the CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). Gene expression data were normalized to the housekeeping gene beta actin (Actb). Fold changes were calculated using the Pfaffl method and fold changes from each treatment in each culture were expressed relative to the control for the corresponding culture [32].

Table 1.

Genes and primer sequences used in qPCR

| Gene name | Symbol | Forward sequence | Reverse sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beta actin | Actb | GGGCACAGTGTGGGTGAC | CTGGCACCACACCTTCTAC |

| Aryl hydrocarbon receptor | Ahr | TTCTTAGGCTCAGCGTCAGCTA | GCAAATCCTGCCAGTCTCTGAT |

| Aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator | Arnt | GATGCGATGATGACCAGATGTG | CAGTGAGGAAAGATGGCTTGTAGG |

| Cytochrome P450 1A1 | Cyp1a1 | TGTCAGATGATAAGGTCATCACG | TCTCCAGAATGAAGGCCTCCAG |

| Cytochrome P450 1B1 | Cyp1b1 | GCGACGATTCCTCCGGGCTG | TGCACGCGGGCCTGAACATC |

| Aryl hydrocarbon receptor repressor | Ahrr | AGAGCTGTGTCCCCAGGGAAGT | AGCTGCCCACGCTCCACATT |

| Steroidogenic acute regulatory protein | Star | CAGGGAGAGGTGGCTATGCA | CCGTGTCTTTTCCAATCCTCTG |

| Cytochrome P450 11A1 | Cyp11a1 | AGATCCCTTCCCCTGGTGACAATG | CGCATGAGAAGAGTATCGACGCATC |

| Hydroxysteroid 17-beta dehydrogenase 1 |

Hsd17b1 | AAGCGGTTCGTGGAGAAGTAG | ACTGTGCCAGCAAGTTTGCG |

| Cytochrome P450 19A1 | Cyp19a1 | CATGGTCCCGGAAACTGTGA | GTAGTAGTTGCAGGCACTTC |

| Estrogen receptor 1 (alpha) | Esr1 | AATTCTGACAATCGACGCCAG | GTGCTTCAACATTCTCCCTCCTC |

| Estrogen receptor 2 (beta) | Esr2 | GGAATCTCTTCCCAGCAGCA | GGGACCACATTTTTGCACTT |

| Progesterone receptor | Pgr | TGGTCCTTGGAGGTCGTAAG | AAGAGCTGGAAGTGTCAGGC |

| Luteinizing hormone/choriogonadotropin receptor | Lhcgr | AACCCGGTGCTTTTTACAAACC | TCCCATTGAATGCATGGCTT |

Analysis of sex steroid hormones

Culture media were subjected to enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA; DRG International Inc.) for the measurement of estradiol (analytical sensitivity 9.7 pg/ml) and estrone (analytical sensitivity 6.3 pg/ml). Assays were run according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Samples were diluted in steroid-free serum prior to loading (estradiol 1:10, estrone 1:2) to match the dynamic range of each ELISA kit and loaded on the ELISA plate in duplicate. Absorbances were measured using a BioTek Synergy LX multi-mode reader and BioTek Gen5 Microplate Reader and Imager Software was used to generate standard curves and calculate sample concentrations.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics software (SPSS Inc.). Data were expressed as mean ± SEM (standard error of the mean). Multiple comparisons between normally distributed experimental groups were made using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett post hoc analysis if equal variances were assumed, or Games–Howell post hoc analysis if equal variances were not assumed. If data were not normally distributed, comparisons between treatment groups were made using Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA. Statistical significance was assigned at P ≤0.05. Data expressing P-values that were greater than 0.05 but less than 0.1 were considered to exhibit a trend toward significance and were denoted by carets.

Results

The effects of AHR antagonism on MEHP-mediated suppression of follicle growth

In control conditions (DMSO), follicles continued to grow over the 96-h treatment period. Similar to previous studies, increasing concentrations of MEHP decreased follicle growth relative to control treated follicles (Figure 1A) [16, 18]. MEHP alone significantly decreased follicle growth at 24 h (4 μM; Figure 1B), 48 h (4 and 400 μM; Figure 1C), 72 h (0.4, 4, and 400 μM; Figure 1D), and 96 h (0.4, 4, 40, and 400 μM; Figure 1E). Co-exposure with 4 μM MEHP and CH223191 blocked the MEHP-mediated suppression of follicle growth at 96 h of treatment (Figure 1E). Follicles treated with 4 μM MEHP and CH223191 showed significantly greater follicle growth than those treated with 4 μM MEHP and similar growth to control. Interestingly, AHR antagonism in combination with lower (0.4 μM) and higher (40 and 400 μM) concentrations of MEHP did not significantly alter follicle growth compared to the respective concentration of MEHP alone (Figure 1A–E).

Figure 1.

The effects of AHR antagonism on MEHP-mediated suppression of follicle growth. Antral follicles were treated with vehicle control (DMSO) or MEHP (0.4–400 μM) in the presence (represented by dashed lines or white bars) or absence (represented by solid lines or gray bars) of CH223191 (1 μM) for 96 h. Follicle growth was measured every 24 h and reported as percent change compared to the follicle size at the start of treatment (0 h = 100%). Data are presented as follicle growth in each treatment at every measurement time point (A) or as follicle growth in each treatment at single time points (B, C, D, E). Data represent mean ± SEM for each treatment (N = 6 separate cultures; 8–12 follicles/treatment/culture). Asterisks (*) represent significance (P ≤ 0.05) compared to control at each time point. Carets (^) represent borderline significance (P ≤ 0.1) compared to control at each time point. Underlined asterisks and carets represent significant and borderline significant differences, respectively, between the respective concentration of MEHP alone and MEHP in combination with CH223191.

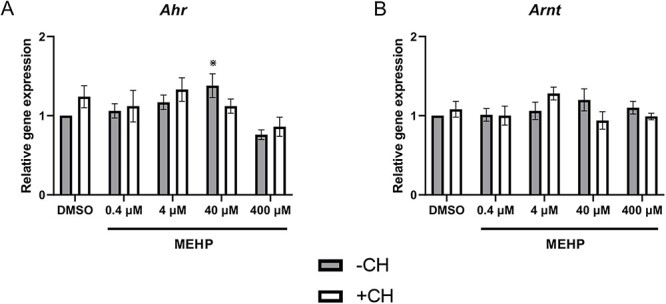

Effects of MEHP on AHR signaling

The AHR is a basic helix–loop–helix transcription factor [26]. Upon ligand binding and receptor activation, the AHR forms a heterodimer with its binding partner, the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT), and this complex targets xenobiotic response elements to regulate expression of target genes [26]. Gene expression analysis was performed to determine if MEHP exposure alters expression of Ahr or Arnt as a mechanism to impair ovarian function. MEHP exposure significantly increased Ahr expression (40 μM) compared to control, but did not alter Arnt expression at any concentration (Figure 2A and B). Co-treatment with MEHP and CH223191 did not alter expression of Ahr and Arnt compared to MEHP alone (Figure 2A and B).

Figure 2.

The effects of MEHP on gene expression of AHR signaling factors. Antral follicles were treated with vehicle control (DMSO) or MEHP (0.4–400 μM) in the presence (white bars) or absence (gray bars) of CH223191 (1 μM) for 96 h. RNA was isolated, converted to cDNA, and subjected to qPCR using primers specific for Ahr (A) and Arnt (B). Data represent mean ± SEM for each treatment (N = 4–6 separate cultures; 8–12 follicles/treatment/culture). Asterisks (*) represent significance (P ≤ 0.05) compared to control.

AHR transcriptional activity was examined by measuring expression of known AHR target genes Cyp1a1, Cyp1b1, and Ahrr. Following MEHP exposure, Cyp1a1 (4, 40, and 400 μM), Cyp1b1 (4, 40, 400 μM), and Ahrr (4 and 40 μM) expression were significantly increased relative to control (Figure 3A–C, respectively). Co-treatment with the AHR antagonist CH223191 significantly reduced MEHP-mediated induction of Cyp1a1 (4, 40, and 400 μM), Cyp1b1 (4, 40, and 400 μM), and Ahrr (4, 40, and 400 μM) compared to MEHP alone (Figure 3A–C, respectively).

Figure 3.

The effects of MEHP on gene expression of AHR regulated genes. Antral follicles were treated with vehicle control (DMSO) or MEHP (0.4–400 μM) in the presence (white bars) or absence (gray bars) of CH223191 (1 μM) for 96 h. RNA was isolated, converted to cDNA, and subjected to qPCR using primers specific for Cyp1a1 (A), Cyp1b1 (B), and Ahrr (C). Data represent mean ± SEM for each treatment (N = 4–6 separate cultures; 8–12 follicles/treatment/culture). Asterisks (*) represent significance (P ≤ 0.05) compared to control unless indicated by brackets. Carets (^) represent borderline significance (P ≤ 0.1) compared to control.

Effects of MEHP-mediated AHR activity on estrogen production

Because CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 initiate the metabolism and clearance of estrogens from the body, media estrone and estradiol levels were measured following MEHP exposure. MEHP significantly decreased estrone levels (4, 40, and 400 μM) compared to control (Figure 4A). Co-treatment with CH223191 and 4 μM MEHP rescued media estrone levels comparable to levels observed with control follicles (Figure 4A). Similarly, MEHP alone decreased media estradiol levels (4, 40, and 400 μM) and co-treatment with CH223191 and 4 μM MEHP rescued media estradiol levels comparable to levels observed with control follicles (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Effects of MEHP-mediated AHR activity on estrogen production. Antral follicles were treated with vehicle control (DMSO) or MEHP (0.4–400 μM) in the presence (white bars) or absence (gray bars) of CH223191 (1 μM) for 96 h. Media were collected and subjected to ELISA for measurement of estrone (A) and estradiol (B). Data represent mean ± SEM for each treatment (N = 4–6 separate cultures; 8–12 follicles/treatment/culture). Asterisks (*) represent significance (P ≤ 0.05) compared to control unless indicated by brackets.

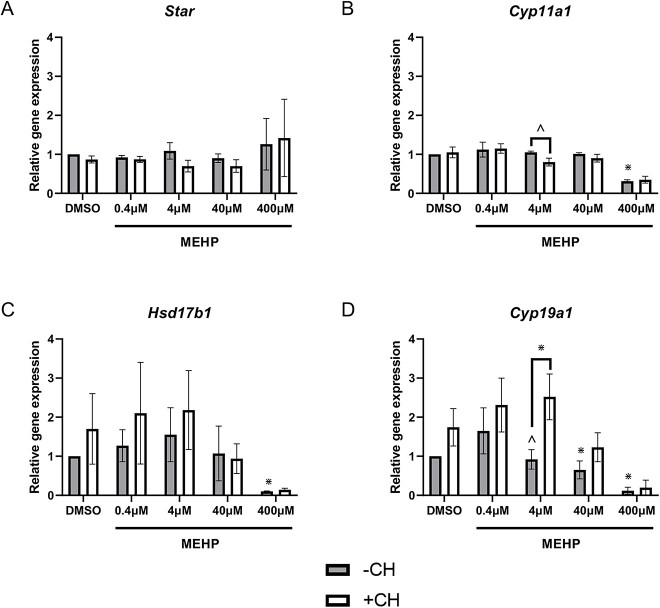

Effects of MEHP on expression of steroidogenic enzymes

To determine whether MEHP-mediated AHR activation reduces estrogen synthesis in antral follicles, gene expression of steroidogenic enzymes was measured. MEHP alone or in combination with CH223191 exposure did not alter expression of Star (Figure 5A). MEHP exposure reduced expression of Cyp11a1 (400 μM), but co-treatment with CH223191 at this concentration of MEHP did not rescue Cyp11a1 expression (Figure 5B). Similarly, MEHP decreased expression of Hsd17b1 (400 μM), but co-treatment with CH223191 did not rescue expression (Figure 5C). MEHP exposure decreased Cyp19a1 expression (40 and 400 μM), but co-treatment with CH223191 did not rescue expression at these concentrations of MEHP (Figure 5D). Interestingly, exposure to 4 μM exhibited a trend toward decreased Cyp19a1 expression, but this did not reach statistical significance (Figure 5D). This MEHP-mediated decline in Cyp19a1 expression was blocked by co-treatment with CH223191 (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

The effects of MEHP on gene expression of steroidogenic enzymes. Antral follicles were treated with vehicle control (DMSO) or MEHP (0.4–400 μM) in the presence (white bars) or absence (gray bars) of CH223191 (1 μM) for 96 h. RNA was isolated, converted to cDNA, and subjected to qPCR using primers specific for Star (A), Cyp11a1 (B), Hsd17b1 (C), and Cyp19a1 (D). Data represent mean ± SEM for each treatment (N = 3 separate cultures; 8–12 follicles/treatment/culture). Asterisks (*) represent significance (P ≤ 0.05) compared to control unless indicated by brackets. Carets (^) represent borderline significance (P ≤ 0.1) compared to control.

Effects of MEHP on estrogen receptor expression and signaling

To determine the effects of MEHP exposure on local estrogen signaling, we compared expression of estrogen receptors (Esr1 and Esr2) and estrogen-sensitive targets progesterone receptor (Pgr) and luteinizing hormone/choriogonadotropin receptor (Lhcgr) in control and MEHP-treated follicles. MEHP exposure alone decreased expression of Esr1 (400 μM) compared to control, and co-treatment with CH223191 did not rescue Esr1 levels compared to MEHP 400 μM alone (Figure 6A). MEHP exposure alone did not alter expression of Esr2 compared to control (Figure 6B). Interestingly, MEHP 4 μM alone did not alter Esr2 expression, but co-treatment with MEHP 4 μM and CH223191 increased Esr2 expression compared to MEHP 4 μM alone (Figure 6B). MEHP alone (4, 40, and 400 μM) significantly decreased expression of the estrogen-sensitive target Pgr compared to control, whereas co-treatment with CH223191 rescued Pgr expression compared to MEHP 4 μM alone and trended toward rescuing Pgr expression compared to MEHP 40 μM alone (Figure 7A). MEHP alone decreased expression of the estrogen-sensitive Lhcgr (4 μM trend toward decrease; 40 and 400 μM significantly decreased) compared to control (Figure 7B). Co-treatment with CH223191 significantly increased Lhcgr expression compared to MEHP 4 μM alone and trended toward increasing Lhcgr expression compared to MEHP 40 μM alone (Figure 7B).

Figure 6.

Effects of MEHP-mediated AHR activity on estrogen receptor expression. Antral follicles were treated with vehicle control (DMSO) or MEHP (0.4–400 μM) in the presence (white bars) or absence (gray bars) of CH223191 (1 μM) for 96 h. RNA was isolated, converted to cDNA, and subjected to qPCR using primers specific for estrogen receptors Esr1 (A) and Esr2 (B). Data represent mean ± SEM for each treatment (N = 4–6 separate cultures; 8–12 follicles/treatment/culture). Asterisks (*) represent significance (P ≤ 0.05) compared to control unless indicated by brackets.

Figure 7.

Effects of MEHP-mediated AHR activity on expression of estrogen-sensitive genes. Follicles were treated with vehicle control (DMSO) or MEHP (0.4–400 μM) in the presence (white bars) or absence (gray bars) of CH223191 (1 μM) for 96 h. RNA was isolated, converted to cDNA, and subjected to qPCR using primers specific for estrogen receptors, Pgr (A) and Lhcgr (B). Data represent mean ± SEM for each treatment (N = 4–6 separate cultures; 8–12 follicles/treatment/culture). Asterisks (*) represent significance (P ≤ 0.05) compared to control unless indicated by brackets. Carets (^) represent borderline significance (P ≤ 0.1) compared to control.

Discussion

This study tested the hypothesis that the AHR plays a functional role in MEHP-mediated disruption of folliculogenesis and steroidogenesis. In the present study, MEHP exposure over a 96-h period significantly decreased follicle growth compared to control. This observation is consistent with previous studies showing that MEHP exposure decreases follicle growth [16, 18]. Treatment with the AHR antagonist CH223191 rescued follicle growth when combined with 4 μM of MEHP, suggesting that MEHP at intermediate concentrations impairs follicle growth via AHR activation. Interestingly, antral follicles from global Ahr−/− mice exhibit reduced growth compared to antral follicles from wild-type mice [33]. However, the role of AHR in supporting follicle growth may be age dependent, as antral follicles from post-pubertal cycling females exhibited no difference in growth between wild-type and Ahr−/− knockout mice [34]. The role of the AHR in follicle growth may also be ligand dependent, as environment contaminants that activate the AHR, including 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin, benzo-a-pyrene, bisphenol A, and methoxychlor, have been shown to impair follicle development [31, 35–37].

Exposing antral follicles to MEHP in vitro increased gene expression of known AHR targets, including Cyp1a1 and Cyp1b1, indicating that MEHP promotes AHR transcriptional activity. Because nearly all the selected concentrations of MEHP (4–400 μM) induced expression of AHR targets, but only 40 μM changed AHR expression, it is likely that MEHP-mediated effects are at the level of receptor activation and not expression. CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 mediate the 2- and 4-hydroxylation of estrogen, respectively, which represents the first step of estrogen metabolism and clearance from the body [27]. In the present study, MEHP-induced expression of Cyp1a1 and Cyp1b1 was associated with reduced estrone and estradiol levels. Moreover, co-exposure with an AHR antagonist blocked MEHP-mediated induction of Cyp1a1 and Cyp1b1 and rescued estrogen levels, providing further evidence that MEHP impairs steroidogenesis by targeting the AHR. In addition to the potential endocrine-disrupting effects of increased estrogen metabolism by CYP1A1 and CYP1B1, 4-hydroxyestradiol has been associated with oxidative stress, DNA damage, and carcinogenesis in estrogen-sensitive tissues [27, 38, 39]. Wang et al. [18] demonstrated that MEHP induced oxidative stress in ovarian antral follicles. Moreover, exposure to DEHP in vivo induced oxidative stress and DNA damage in the ovaries of exposed mice [40]. Further research is needed to determine if AHR and its targets CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 play a role in phthalate-mediated oxidative stress and DNA damage.

We also observed that MEHP reduced Cyp19a1 expression compared to control. This MEHP-mediated decline is in agreement with previous studies [20]. As CYP19A1 mediates the final step of estrogen biosynthesis, this is consistent with the decline in media estrogen levels observed following MEHP exposure. Previous work has shown that exposing antral follicles to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD), a potent AHR agonist, resulted in a decline in both Cyp19a1 expression and estrogen production [41], similar to the observations made in the present study following MEHP exposure. Indeed, we found that AHR antagonism blocked the decline in Cyp19a1 expression following MEHP exposure (4 μm), suggesting that the AHR may play a role in the MEHP-mediated decline. Together, these data suggest that MEHP adversely affects estrogen production by targeting enzymes involved in estrogen synthesis and metabolism in an AHR-dependent manner.

In addition to its role in estrogen production, the AHR can interfere with estrogen receptor signaling [42]. In the present study, MEHP exposure decreased expression of the estrogen-sensitive targets Pgr and Lhcgr, and this effect was blocked by co-treatment with CH223191, indicating that MEHP-mediated suppression of these targets is AHR dependent, likely from the decline in estrogen production following MEHP exposure. Both PGR and LHCGR are critical mediators of ovulation as knockout mouse models lacking either Pgr or Lhcgr exhibit ovulation defects [43, 44]. Similarly, mouse models lacking Esr1 or Esr2 exhibit diminished ovulation compared to wild-type control mice [45, 46]. In addition, Esr2 mutant mice showed significantly reduced ovulation and expression of both Pgr and Lhcgr in response to gonadotropin stimulation compared to wild-type mice [47]. Together, these studies suggest a mechanism by which estrogen signaling within the ovary induces molecular changes to facilitate ovulation. Interestingly, Land et al. recently demonstrated that antral follicles exposed in vitro to an environmentally relevant phthalate mixture containing DEHP exhibited a reduced rate of ovulation compared to DMSO-treated follicles following stimulation with human chorionic gonadotropin, suggesting that phthalates can disrupt ovulation [48]. Further research is needed to determine if AHR-ER crosstalk plays a role in phthalate-mediated ovulatory defects.

The present study provides compelling data that MEHP exposure leads to hyperactivation of the AHR, and this in turn impairs estrogen production and signaling in the ovary. However, given that these observations were made in an in vitro system using isolated antral follicles, it is unclear whether these observations will be recapitulated in vivo. Although exposing rodents orally to DEHP, the parent compound of MEHP, decreases circulating estrogen levels, it is unknown whether AHR activation contributes to this effect [13, 49]. Further in vivo analysis of the role of AHR in phthalate-mediated dysfunction is warranted. Moreover, although the present study provides a link between MEHP exposure and AHR activation, it is unclear whether this is through a direct interaction between MEHP and the AHR or indirectly through an unidentified upstream mechanism. Further work is necessary to fully understand the biochemical nature of this interaction.

In conclusion, the findings of the present study suggest a mechanism by which MEHP exposure increases AHR activation in ovarian antral follicles, leading to increased expression of the estrogen-metabolizing enzymes Cyp1a1 and Cyp1b1 and decreased estrogen secretion by the follicle (Figure 8). This decline in estrogen production alters local estrogen signaling within the follicle to reduce expression of estrogen-sensitive targets, such as Lhcgr and Pgr. Changes in LHCGR and PGR expression could reduce the sensitivity of ovarian antral follicles to hormonal cues from the pituitary and could further affect key ovarian functions, including steroidogenesis and ovulation.

Figure 8.

Proposed mechanism of MEHP-mediated disruption of estrogen production and signaling in antral follicles. MEHP exposure activates AHR in ovarian antral follicles. Increased AHR transcriptional activity increases expression of estrogen-metabolizing enzymes CYP1A1 and CYP1B1, leading to a decline in estrogen secretion by the follicle. Reduced estrogen levels impair local estrogen signaling within the follicle, leading to decreased expression of estrogen-sensitive targets, such as Lhcgr, which is critical for steroidogenesis and ovulation.

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: A.M.N. and J.A.F.; investigation: A.M.N., Z.I., V.E.M., R.S.M., A.G., and M.J.L.; writing: A.M.N. and J.A.F.

Data availability

The raw data will be available upon reasonable request to the senior author.

Footnotes

† Grant Support: This work was supported by NIH (T32 ES007326, F30 ES033914, and R01 ES034112).

Contributor Information

Alison M Neff, Department of Comparative Biosciences, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, USA.

Zane Inman, Department of Comparative Biosciences, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, USA.

Vasiliki E Mourikes, Department of Comparative Biosciences, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, USA.

Ramsés Santacruz-Márquez, Department of Comparative Biosciences, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, USA.

Andressa Gonsioroski, Department of Comparative Biosciences, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, USA.

Mary J Laws, Department of Comparative Biosciences, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, USA.

Jodi A Flaws, Department of Comparative Biosciences, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, USA.

References

- 1. Neff AM, Flaws JA. The effects of plasticizers on the ovary. Curr Opin Endocr Metab Res 2021; 18:35–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chiang C, Mahalingam S, Flaws JA. Environmental contaminants affecting fertility and somatic health. Semin Reprod Med 2017; 35:241–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brehm E, Flaws JA. Transgenerational effects of endocrine-disrupting chemicals on male and female reproduction. Endocrinology 2019; 160:1421–1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gonsioroski A, Mourikes VE, Flaws JA. Endocrine disruptors in water and their effects on the reproductive system. Int J Mol Sci 2020; 21. 10.3390/ijms21661929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mourikes VE, Flaws JA. REPRODUCTIVE TOXICOLOGY: effects of chemical mixtures on the ovary. Reproduction 2021; 162:F91–f100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ye X, Liu J. Effects of pyrethroid insecticides on hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis: a reproductive health perspective. Environ Pollut 2019; 245:590–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Plunk EC, Richards SM. Endocrine-disrupting air pollutants and their effects on the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal axis. Int J Mol Sci 2020; 21:9191. 10.3390/ijms21239191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barbosa KL, Dettogni RS, da Costa CS, Gastal EL, Raetzman LT, Flaws JA, Graceli JB. Tributyltin and the female hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal disruption. Toxicol Sci 2022; 186:179–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Halden RU. Plastics and health risks. Annu Rev Public Health 2010; 31:179–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Registry, ATSDR. Toxicological Profile for Di(2-Ethylhexyl)Phthalate (DEHP). U.S.D.o.H.a.H. Services. Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service, Atlanta, GA; 2022.

- 11. Hannon PR, Niermann S, Flaws JA. Acute exposure to di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate in adulthood causes adverse reproductive outcomes later in life and accelerates reproductive aging in female mice. Toxicol Sci 2016; 150:97–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chiang C, Flaws JA. Subchronic exposure to di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate and diisononyl phthalate during adulthood has immediate and long-term reproductive consequences in female mice. Toxicol Sci 2019; 168:620–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chiang C, Lewis LR, Borkowski G, Flaws JA. Exposure to di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate and diisononyl phthalate during adulthood disrupts hormones and ovarian folliculogenesis throughout the prime reproductive life of the mouse. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2020; 393:114952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Frederiksen H, Skakkebaek NE, Andersson AM. Metabolism of phthalates in humans. Mol Nutr Food Res 2007; 51:899–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Warner GR, Li Z, Houde ML, Atkinson CE, Meling DD, Chiang C, Flaws JA. Ovarian metabolism of an environmentally relevant phthalate mixture. Toxicol Sci 2019; 169:246–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gupta RK, Singh JM, Leslie TC, Meachum S, Flaws JA, Yao HHC. Di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate and mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate inhibit growth and reduce estradiol levels of antral follicles in vitro. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2010; 242:224–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Reinsberg J, Wegener-Toper P, van der Ven K, van der Ven H, Klingmueller D. Effect of mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate on steroid production of human granulosa cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2009; 239:116–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang W, Craig ZR, Basavarajappa MS, Hafner KS, Flaws JA. Mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate induces oxidative stress and inhibits growth of mouse ovarian antral follicles. Biol Reprod 2012; 87:152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Craig ZR, Singh J, Gupta RK, Flaws JA. Co-treatment of mouse antral follicles with 17beta-estradiol interferes with mono-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (MEHP)-induced atresia and altered apoptosis gene expression. Reprod Toxicol 2014; 45:45–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hannon PR, Brannick KE, Wang W, Flaws JA. Mono(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate accelerates early folliculogenesis and inhibits steroidogenesis in cultured mouse whole ovaries and antral follicles. Biol Reprod 2015; 92:120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li N, Liu T, Guo K, Zhu J, Yu G, Wang S, Ye L. Effect of mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (MEHP) on proliferation of and steroid hormone synthesis in rat ovarian granulosa cells in vitro. J Cell Physiol 2018; 233:3629–3637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wójtowicz AK, Sitarz-Głownia AM, Szczęsna M, Szychowski KA. The action of di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) in mouse cerebral cells involves an impairment in aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) signaling. Neurotox Res 2019; 35:183–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Iizuka T, Yin P, Zuberi A, Kujawa S, Coon JS V, Björvang RD, Damdimopoulou P, Pacyga DC, Strakovsky RS, Flaws JA, Bulun SE. Mono-(2-ethyl-5-hydroxyhexyl) phthalate promotes uterine leiomyoma cell survival through tryptophan-kynurenine-AHR pathway activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022; 119:e2208886119. 10.1073/pnas.2208886119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tsai ML, Hsu SH, Wang LT, Liao WT, Lin YC, Kuo CH, Hsu YL, Feng MC, Kuo FC, Hung CH. Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate mediates IL-33 production via aryl hydrocarbon receptor and is associated with childhood allergy development. Front Immunol 2023; 14:1193647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tsai CF, Hsieh TH, Lee JN, Hsu CY, Wang YC, Kuo KK, Wu HL, Chiu CC, Tsai EM, Kuo PL. Curcumin suppresses phthalate-induced metastasis and the proportion of cancer stem cell (CSC)-like cells via the inhibition of AhR/ERK/SK1 signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Agric Food Chem 2015; 63:10388–10398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Matthews JA, Ahmed S. AHR- and ER-mediated toxicology and chemoprevention. In: James JMH, Fishbein C (eds.), Advances in Molecular Toxicology. New York, New York: Elsevier; 2013: 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tsuchiya Y, Nakajima M, Yokoi T. Cytochrome P450-mediated metabolism of estrogens and its regulation in human. Cancer Lett 2005; 227:115–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Göttel M, le Corre L, Dumont C, Schrenk D, Chagnon MC. Estrogen receptor α and aryl hydrocarbon receptor cross-talk in a transfected hepatoma cell line (HepG2) exposed to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Toxicol Rep 2014; 1:1029–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hernández-Ochoa I, Karman BN, Flaws JA. The role of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in the female reproductive system. Biochem Pharmacol 2009; 77:547–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Benedict JC, Miller KP, Lin TM, Greenfeld C, Babus JK, Peterson RE, Flaws JA. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor regulates growth, but not atresia, of mouse preantral and antral follicles. Biol Reprod 2003; 68:1511–1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Karman BN, Basavarajappa MS, Craig ZR, Flaws JA. 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin activates the aryl hydrocarbon receptor and alters sex steroid hormone secretion without affecting growth of mouse antral follicles in vitro. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2012; 261:88–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pfaffl, M.W., A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR . Nucleic Acids Res 2001; 29: p. e45, 45e, 445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Barnett KR, Tomic D, Gupta RK, Miller KP, Meachum S, Paulose T, Flaws JA. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor affects mouse ovarian follicle growth via mechanisms involving estradiol regulation and responsiveness. Biol Reprod 2007; 76:1062–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hernandez-Ochoa I, Barnett-Ringgold KR, Dehlinger SL, Gupta RK, Leslie TC, Roby KF, Flaws JA. The ability of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor to regulate ovarian follicle growth and estradiol biosynthesis in mice depends on stage of sexual maturity. Biol Reprod 2010; 83:698–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Perono GA, Petrik JJ, Thomas PJ, Holloway AC. The effects of polycyclic aromatic compounds (PACs) on mammalian ovarian function. Curr Res Toxicol 2022; 3:100070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ziv-Gal A, Craig ZR, Wang W, Flaws JA. Bisphenol a inhibits cultured mouse ovarian follicle growth partially via the aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling pathway. Reprod Toxicol 2013; 42:58–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Basavarajappa MS, Hernández-Ochoa I, Wang W, Flaws JA. Methoxychlor inhibits growth and induces atresia through the aryl hydrocarbon receptor pathway in mouse ovarian antral follicles. Reprod Toxicol 2012; 34:16–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chen ZH, Na HK, Hurh YJ, Surh YJ. 4-Hydroxyestradiol induces oxidative stress and apoptosis in human mammary epithelial cells: possible protection by NF-kappaB and ERK/MAPK. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2005; 208:46–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Salama SA, Kamel M, Awad M, Nasser AHB, al-Hendy A, Botting S, Arrastia C. Catecholestrogens induce oxidative stress and malignant transformation in human endometrial glandular cells: protective effect of catechol-O-methyltransferase. Int J Cancer 2008; 123:1246–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li L, Liu JC, Lai FN, Liu HQ, Zhang XF, Dyce PW, Shen W, Chen H. Di (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate exposure impairs growth of antral follicle in mice. PloS One 2016; 11:e0148350. 10.1371/journal.pone.0148350. eCollection 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Karman BN, Basavarajappa MS, Hannon P, Flaws JA. Dioxin exposure reduces the steroidogenic capacity of mouse antral follicles mainly at the level of HSD17B1 without altering atresia. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2012; 264:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Matthews J, Gustafsson JA. Estrogen receptor and aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling pathways. Nucl Recept Signal 2006; 4:e016. 10.1621/nrs.04016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lydon JP, DeMayo FJ, Funk CR, Mani SK, Hughes AR, Montgomery CA, Shyamala G, Conneely OM, O'Malley BW. Mice lacking progesterone receptor exhibit pleiotropic reproductive abnormalities. Genes Dev 1995; 9:2266–2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhang FP, Poutanen M, Wilbertz J, Huhtaniemi I. Normal prenatal but arrested postnatal sexual development of luteinizing hormone receptor knockout (LuRKO) mice. Mol Endocrinol 2001; 15:172–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rumi MA, Dhakal P, Kubota K, Chakraborty D, Lei T, Larson MA, Wolfe MW, Roby KF, Vivian JL, Soares MJ. Generation of Esr1-knockout rats using zinc finger nuclease-mediated genome editing. Endocrinology 2014; 155:1991–1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Krege JH, Hodgin JB, Couse JF, Enmark E, Warner M, Mahler JF, Sar M, Korach KS, Gustafsson JÅ, Smithies O. Generation and reproductive phenotypes of mice lacking estrogen receptor beta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998; 95:15677–15682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rumi MAK, Singh P, Roby KF, Zhao X, Iqbal K, Ratri A, Lei T, Cui W, Borosha S, Dhakal P, Kubota K, Chakraborty D, et al. Defining the role of estrogen receptor β in the regulation of female fertility. Endocrinology 2017; 158:2330–2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Land KL, Lane ME, Fugate AC, Hannon PR. Ovulation is inhibited by an environmentally relevant phthalate mixture in mouse antral follicles in vitro. Toxicol Sci 2021; 179:195–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Li N, Zhou L, Zhu J, Liu T, Ye L. Role of the 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase signalling pathway in di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate-induced ovarian dysfunction: an in vivo study. Sci Total Environ 2020; 712:134406. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data will be available upon reasonable request to the senior author.