Abstract

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is increasingly being utilized for the resection of superficial gastrointestinal neoplasms. However, the long procedure time poses a technical challenge for conventional ESD (C-ESD). Traction-assisted ESD (T-ESD) was developed to facilitate the procedure by reducing its duration. This study compares the efficacy and safety of C-ESD versus T-ESD in the treatment of esophageal, gastric, and colorectal neoplasms. Nine randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were analyzed. Traction-assisted ESD exhibited shorter mean dissection times for the esophagus and colorectal regions and lower perforation rates in colorectal cases. No significant differences were observed in en bloc resection or bleeding rates. Traction-assisted ESD proves to be more efficient in mean procedure time for esophageal and colorectal cases and safer in perforation rates for colorectal cases, but similar rates are noted for en bloc resection or bleeding.

Keywords: endoscopic advanced treatment, gastrointestinal endoscopy, endoscopy, traction, endoscopic submucosal dissection

Introduction and background

Superficial gastrointestinal neoplasms, which are defined in most guidelines as lesions limited to the mucosa or submucosa without invading the muscularis propria, regardless of the presence of lymph node involvement, are susceptible to endoscopic treatment using advanced techniques such as endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). Lesions located in the esophagus, stomach, or colorectal region can be effectively and safely resected en bloc. In addition, this technique provides a less invasive approach than surgical procedures. However, ESD has the limitation of being technically difficult, requiring a long procedure time, and having a long learning curve [1].

Conventional ESD (C-ESD) is a technique performed in three phases: delimitation, incision, and dissection. A wide variety of devices have been developed to assist in its performance, such as dual electrosurgical knives. These accessories assist in the dissection stage by allowing both the injection of solutions to elevate the submucosa and the cutting of tissue [2]. However, the tubular shape of the endoscopic device and the difficulty in manipulating the tissues in a non-axial way limit the operator's movements and can prolong the procedure time [3].

Traction-assisted ESD (T-ESD) emerged as a method to facilitate the dissection of the space between the mucosa and muscularis propria by increasing the separation of the planes exerted by traction [4,5]. Different techniques have been developed to exert this traction, either with external traction or internal devices. The most commonly used are clips with thread, S-O clips (traction clips), ring-shaped thread, clip-flaps, grasping forceps, dental floss, springs, and loops [6, 7].

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to compare the efficacy and safety of C-ESD versus T-ESD in the approach to neoplasms of the esophagus, stomach, and colorectal region. Efficacy was analyzed by mean dissection time and en bloc resection rate, and safety by perforation and bleeding rate.

Review

Methods

Study Protocol and Registration

This meta-analysis was reported according to the guidelines of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [8]. The study protocol was registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (registration number: CRD42022385314).

Search Strategy

An electronic search of the Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE), Excerpta Medica database (Embase), and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) databases was performed, as was a manual search of the references of the most relevant studies. The combination of the following operators was used to perform the search: “endoscopic submucosal dissection," "ESD," "complete endoscopic resection," “submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection," “endoscopic full-thickness resection," "traction," “thread-traction," "clip,” and "randomized controlled trial." Detailed search strategies can be found below in Table 1.

Table 1. Detailed electronic database search strategy.

MEDLINE: Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online; Embase: Excerpta Medica database; CENTRAL: Cochrane Controlled Register of Trials

| Databases | Electronic search strategy |

| MEDLINE | ((ESD) OR (Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection) OR (Dissection, Endoscopic Submucosal) OR (Submucosal Dissection, Endoscopic) OR (Endoscopic Full Thickness Resection) OR (Endoscopic Mucosal Resection) OR (Submucosal Tunneling Endoscopic Resection)) AND ((Traction) or (Rubber Band) or (Thread-traction) or (clip)) AND (Randomized Controlled Trials) |

| Embase | (‘ESD' OR 'Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection' OR 'Dissection, Endoscopic Submucosal' OR 'Submucosal Dissection, Endoscopic' OR 'Endoscopic Full Thickness Resection' OR 'Endoscopic Mucosal Resection' OR 'Submucosal Tunneling Endoscopic Resection’) AND (‘Traction' or 'Rubber Band' or 'Thread-traction' or ‘clip’) AND ('randomized controlled trial'/exp OR 'randomized controlled trial’) |

| CENTRAL | ((ESD) OR (Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection) OR (Dissection, Endoscopic Submucosal) OR (Submucosal Dissection, Endoscopic) OR (Endoscopic Full Thickness Resection) OR 'Endoscopic Mucosal Resection' OR 'Submucosal Tunneling Endoscopic Resection’) AND (‘Traction' or 'Rubber Band' or 'Thread-traction' or ‘clip’) AND ('randomized controlled trial'/exp OR 'randomized controlled trial’) |

The searches were carried out between January and May 2023. There were no restrictions on language or period of publication. Only full texts were included. Alerts were created in the databases informing of new results.

Eligibility Criteria

The eligibility criteria for this study included adults diagnosed with neoplasms of the esophagus, stomach, or colorectal region undergoing either C-ESD or T-ESD. The outcomes of interest comprised mean dissection time, en bloc resection rates, perforation, and bleeding. Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were considered eligible for inclusion. Exclusion criteria encompassed studies with overlapping patients, experimental animal studies, and conference abstracts.

Study Selection and Data Collection

Two independent reviewers carried out all the steps. Initially, they were responsible for excluding duplicate studies identified in the different databases. Subsequently, they read the titles and abstracts of the remaining studies, selecting those that addressed the subject of the study. Finally, the full texts were read, and those that met the inclusion criteria were selected. A consensus was established between the reviewers in the presence of disagreements at any stage of the selection. Data were also extracted independently by two reviewers and recorded on specific collection forms. Disagreements at the data collection stage were resolved by consensus between the reviewers after retrieving the information in the original article.

Risk of Bias and Quality of Studies

The risk of bias was assessed individually for each study using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 (RoB 2) tool [9]. The quality of the evidence was assessed using the Grading of Assessment, Development, and Evaluation of Recommendations (GRADE) [10].

Outcomes

The primary outcome analyzed was efficacy, which is defined by the en bloc resection rate and the mean dissection time. The secondary outcome was safety, which was analyzed by adverse effects, including the rate of perforation and bleeding.

Statistical Analysis

The data on dissection time were presented as a mean with a standard deviation in relation to the total number of procedures carried out. The rates of en bloc resection, perforation, and bleeding were presented as a proportion of the absolute number of events in relation to the total number of procedures performed. Data were presented using pooled and subgroup analyses for the esophagus, stomach, and colorectal location for each of the outcomes.

Heterogeneity was assessed by the Statistical Inconsistency Index (I2). Values <30%, 30%-60%, 61%-75%, and >75% were considered low, moderate, high, and very high, respectively. The fixed effect model was used for low/moderate values. If I2 was considered high/very high, we carried out a sensitivity analysis using a funnel plot to identify possible outliers. If the sample became homogeneous after excluding possible outliers, the studies were permanently excluded (considered true outliers), and a fixed effects model was used. When there were no outliers or heterogeneity remained high after excluding outliers, we used random effects to reduce the influence of heterogeneity on the final result.

The results were expressed as risk differences (RDs) with the respective confidence intervals (95% CI). Intention-to-treat analysis was performed in all studies. Statistical analyses were carried out using Review Manager (RevMan), version 5.4.1 (The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020).

Results

Study Selection

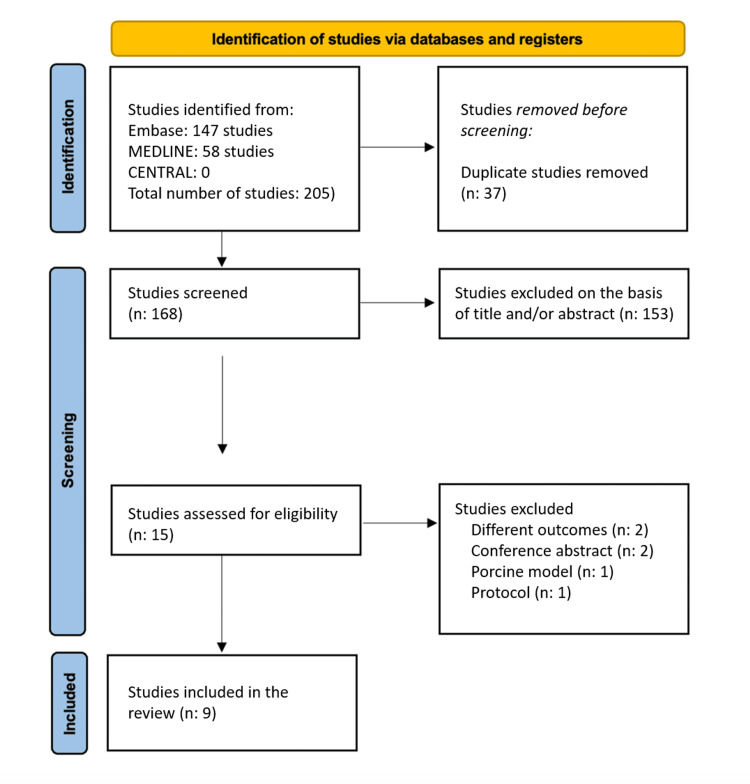

A total of 205 studies were identified. Of these, 37 were duplicates, and 153 were excluded after reading the titles and abstracts. The remaining 15 articles were read in full text and subjected to inclusion and exclusion criteria, which enabled nine studies to be selected to compose this meta-analysis. A detailed flowchart of the study selection process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. A flowchart outlining the screening process for study inclusion in the meta-analysis based on PRISMA guidelines.

Out of 205 initially identified studies, 37 duplicates were removed. Following the title and abstract review, 153 studies were excluded. A full-text assessment of the remaining 15 articles was conducted based on pre-established inclusion and exclusion criteria, resulting in the selection of nine studies for meta-analysis inclusion.

PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; Embase: Excerpta Medica database; MEDLINE: Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online; CENTRAL: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials

Study Characteristics

A total of 1,477 patients were analyzed. Of these, 741 patients underwent C-ESD and 736 underwent T-ESD. One study was Chinese [11], and all others were Japanese [12-19]. Among them, two evaluated procedures were performed in the esophagus [12, 13], three in the stomach [14-16], and four in the colorectal location [11,17-19]. Regarding traction techniques, five studies used clip methods [12-14, 17, 18], one combined clip with dental floss [15], one used the ring-thread technique [19], one used grasping forceps [11], and the other used the spring and loop for traction [16]. The detailed characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Characteristics of the included studies.

T-ESD: traction-assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection; C-ESD: conventional endoscopic submucosal dissection; RCT: randomized controlled trial

| Author and year | Patients (n) T-ESD vs. C-ESD | Location of the lesion | Country | Traction method | Type of study |

| Koike et al., 2015 [12] | 20/20 | Esophagus | Japan | Clip with thread | RCT |

| Ritsuno et al., 2014 [17] | 27/23 | Colon | Japan | S-O clip | RCT |

| Mori et al., 2017 [19] | 21/22 | Colon | Japan | Ring-shaped thread | RCT |

| Ban et al., 2018 [14] | 49/55 | Gastric | Japan | Clip–flap | RCT |

| Wang et al., 2019 [11] | 21/20 | Colon | China | Grasping forceps | RCT |

| Yoshida et al., 2018 [15] | 319/316 | Gastric | Japan | Dental floss | RCT |

| Yoshida et al., 2020 [13] | 116/117 | Esophagus | Japan | Clip–flap | RCT |

| Nagata et al., 2021 [16] | 40/40 | Gastric | Japan | Spring and loop | RCT |

| Ichijima et al., 2022 [18] | 123/128 | Colon | Japan | Clip–flap | RCT |

Risk of Bias and Quality of Studies

The application of the RoB2 tool identified that two selected studies [12,17] presented a low risk of bias due to the appropriate randomization process, the presence of all outcome data with their correct measurement, and the absence of deviations in the intended interventions or the selection of the reported outcome. One study [16] presented some concerns in the outcome measurement domain and six studies [11,13-15,18,19] in the domain of the selection of the reported outcome. A detailed description of the risk of bias is presented below in Table 3.

Table 3. Risk of bias in the included studies.

| Study ID | Randomization process | Deviations from intended interventions | Missing outcome data | Measurement of the outcome | Selection of the reported results |

| Koike et al., 2015 [12] | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Ritsuno et al., 2014 [17] | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Mori et al., 2017 [19] | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns |

| Ban et al., 2018 [14] | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns |

| Wang et al., 2019 [11] | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns |

| Yoshida et al., 2018 [15] | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns |

| Yoshida et al., 2020 [13] | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns |

| Nagata et al., 2021 [16] | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Low risk |

| Ichijima et al., 2022 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns |

The quality of the evidence in the included studies revealed a high degree of certainty for the evidence, which is presented in Appendix 1.

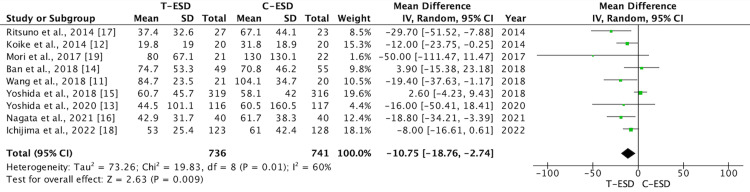

Mean Dissection Time

A total of 1,477 patients were analyzed for this outcome, with 741 undergoing C-ESD and 736 undergoing T-ESD in the nine studies included. The T-ESD group had a shorter mean dissection time than the C-ESD group (mean difference: -10.75; 95% CI (-18.76, -2.74); p = 0.009; I2 = 60%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A forest plot of dissection time.

T-ESD: traction-assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection with traction); C-ESD: conventional endoscopic submucosal dissection

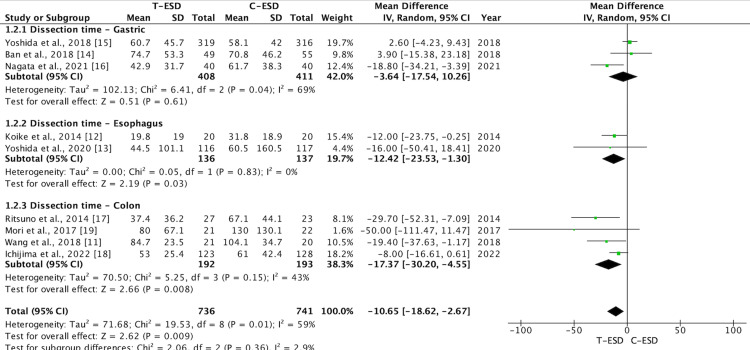

When subgroup analysis was carried out, this difference was maintained for the esophagus (mean difference: -12.42; 95% CI (-23.53, -1.30); p = 0.03; I2 = 0%) and colorectal regions (mean difference: -17.37; 95% CI (-30.20, -4.55); p = 0.008; I2 = 43%). There was no difference in the analysis of the stomach subgroup (mean difference: -3.64; 95% CI (-17.54, 10.26); p = 0.61; I2 = 69%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. A forest plot of procedure time: subgroup analysis.

T-ESD: traction-assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection with traction); C-ESD: conventional endoscopic submucosal dissection

The GRADE analysis revealed a high certainty of evidence.

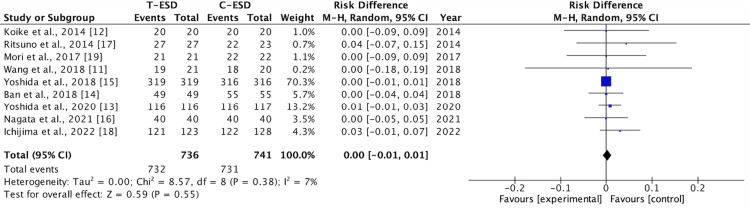

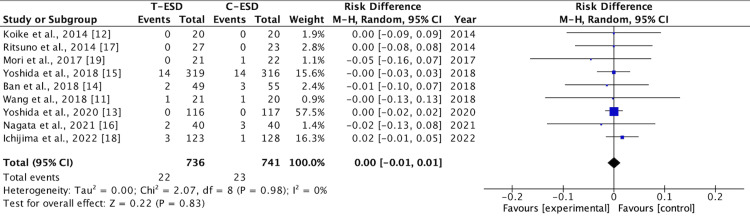

En Bloc Resection Rate

All nine studies evaluated the outcome of the en bloc resection rate. There was no difference in this outcome when comparing the C-ESD with the T-ESD in the pooled analysis (RD: <0.00; 95% CI (-0.01, 0.01); p = 0.55; I2 = 7%) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. A forest plot of en bloc resection rate.

T-ESD: traction-assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection with traction); C-ESD: conventional endoscopic submucosal dissection

In the subgroup analysis of the esophagus (RD: 0.01; 95% CI (-0.01, 0.03); p = 0.85; I2 = 0%) and stomach (RD, 0.00; 95% CI (-0.01, 0.01); p = 1.00; I2 = 0%), there was also no difference between C-ESD and T-ESD, but in the analysis of the colorectal region subgroup (RD: 0.04; 95% CI (0.00, 0.07); p = 0.78; I2 = 0%), a difference favorable to the T-ESD method was identified (Figure 5).

Figure 5. A forest plot of en bloc resection rate: subgroup analysis.

T-ESD: traction-assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection with traction); C-ESD: conventional endoscopic submucosal dissection

The GRADE analysis revealed a high certainty of evidence.

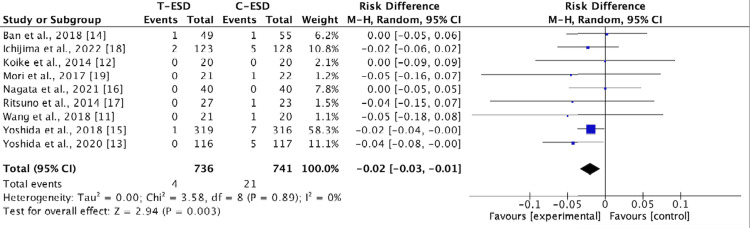

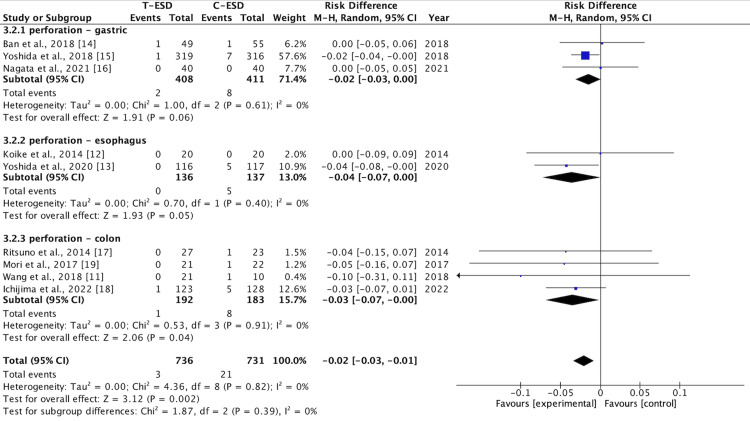

Perforation Rate

This outcome was assessed by the nine studies, and the pooled analysis showed that T-ESD had a lower perforation rate than C-ESD (RD: -0.02; 95% CI (-0.03, -0.01); p = 0.89; I2 = 0%) (Figure 6).

Figure 6. A forest plot of perforation rate.

T-ESD: traction-assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection with traction); C-ESD: conventional endoscopic submucosal dissection

This difference was maintained in the subgroup analysis for the colorectal region (RD: -0.03; 95% CI (-0.07, <-0.00); p = 0.04; I2 = 0%). There was no difference in the analysis of the esophagus subgroup (RD: -0.04; 95% CI (-0.07, >0.00); p = 0.05; I2 = 0%) and the stomach subgroup (RD: -0.02; 95% CI (-0.03, >0.00); p = 0.06; I2 = 0%) (Figure 7).

Figure 7. A forest plot perforation rate: subgroup analysis.

T-ESD: traction-assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection with traction); C-ESD: conventional endoscopic submucosal dissection

The GRADE analysis revealed a high certainty of evidence.

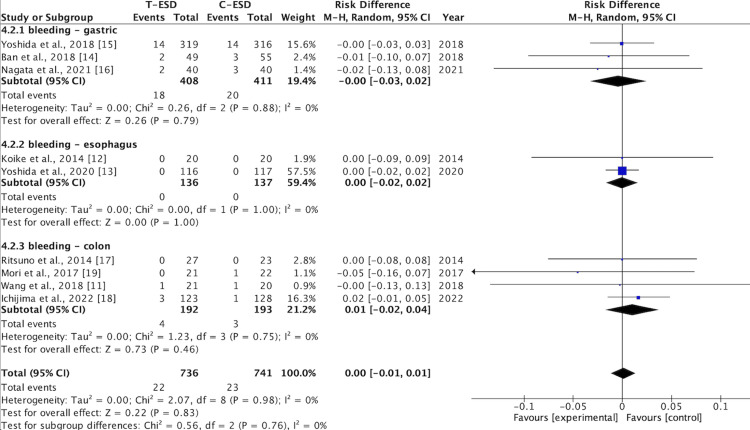

Bleeding Rate

Bleeding rates were reported in the nine included studies. There was no difference in this outcome when comparing C-ESD with T-ESD in the pooled analysis (RD: <0.00; 95% CI (-0.01, 0.01); p = 0.83; I2 = 0%) (Figure 8).

Figure 8. A forest plot of the bleeding rate.

T-ESD: traction-assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection with traction); C-ESD: conventional endoscopic submucosal dissection

In the subgroup analysis of the esophagus (RD: <0.00; 95% CI (-0.02, 0.02); p = 1.00; I2 = 0%), stomach (RD: <-0.00; 95% CI (-0.03, 0.02); p = 0.79; I2 = 0%), and colorectal region (RD: 0.01; 95% CI (-0.02, 0.04); p = 0.46; I2 = 0%), there was also no difference between C-ESD and T-ESD (Figure 9).

Figure 9. A forest plot of the bleeding rate: subgroup analysis.

T-ESD: traction-assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection with traction); C-ESD: conventional endoscopic submucosal dissection

The GRADE analysis revealed a high certainty of evidence.

Discussion

This meta-analysis reveals that the T-ESD technique, when compared to C-ESD, has better efficacy when the aspect evaluated is the mean dissection time. This can be evidenced both in the grouped analysis and in the subgroup analysis for the esophageal and colorectal regions. Regarding safety, it is possible to identify a result equally favorable to T-ESD in the grouped and subgroup evaluations for the colorectal region when analyzing the perforation rate.

However, there was no difference in efficacy between the techniques when evaluating grouped or subgroup en bloc resection rates, as well as the mean dissection time for the stomach subgroup. In terms of safety, it was not possible to identify a difference in the grouped or subgroup analysis when the outcome assessed was the bleeding rate, as well as in the perforation rates for the esophagus and stomach subgroups.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection is a technique that allows lesions to be resected with protection of the lateral margins and in a monobloc fashion, even in larger lesions of the digestive tract. Although the C-ESD and T-ESD techniques have equivalent en bloc resection rates, the fact that we can perform traction on the lesion as an auxiliary method allows us to bring endoscopic-type movements closer to "laparoscopic" type movements [20,21]. In this way, tissue triangulation becomes possible, facilitating dissection with an endoluminal instrument that, until then, performed unidirectional movements. This can influence practicality, efficiency, and safety during the procedure [22]. Thus, this technique may make more endoscopists feel more encouraged to perform it.

The best results in mean dissection time identified for the esophagus and colorectal region can be explained by the fact that they are tubular organs, thus allowing better control of traction techniques when a device is placed on the contralateral wall. Likewise, as they vary little in caliber, the endoscopy device is parallel to the axis of these organs, facilitating dissection in both the frontal and rear views [23].

As far as safety is concerned, one of the biggest fears when carrying out the procedure is the occurrence of perforation, as this can lead to greater morbidity for patients and higher hospital costs. The traction method, by allowing better visualization of the submucosal and muscular layers, makes the procedure safer and reduces the risk of perforation, as occurred in the colorectal subgroup.

The currently established traction techniques (clips, coils, and dental floss), regardless of which one is used, show the benefits of their use. Even so, it must be acknowledged that there has been variability in the traction method used and new methods have been described even more recently. Methods such as magnetic counter-traction and the suture pulley method have shown promising results in animal studies. The pulley and suture method was tested in a porcine model by 13 endoscopists, demonstrating a significant reduction in procedure time and the technical demands of ESD, especially among younger endoscopists [24]. Similarly, the magnetic counter-traction device reduced dissection time by almost half when performed on a porcine model with simulated lesions up to 30 mm in diameter [25].

The positive points of this meta-analysis are the inclusion of only RCTs, which constitute a 1A level of evidence; the low heterogeneity of most of the results analyzed was related to a rigorous methodology; and all the outcomes analyzed were evaluated by all the studies.

This study has some limitations. All the studies included were from Asia. On this continent, traditionally, a greater number of ESDs are performed, presenting a significant number of cases and a typical routine for endoscopists. This may interfere with defining the reproducibility of the method for other services. In addition, the studies included different sizes, morphologies, and locations of lesions in the different organs and different traction devices, which makes it more difficult to define specific situations where and which traction method may be more beneficial.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the meta-analysis underscores the positive impact of T-ESD over C-ESD, notably evident in the significant reduction of mean dissection time, particularly observed in the esophageal and colorectal regions. This efficiency boost is attributed to the traction techniques' ability to streamline endoscopic movements, thereby enhancing procedural practicality and efficacy. Moreover, the lower perforation rate observed in the colorectal subgroup highlights T-ESD's enhanced safety profile, facilitated by improved visualization of submucosal and muscular layers. Notably, both techniques demonstrate comparable en bloc resection rates and bleeding rates across all evaluated subgroups.

While acknowledging these positive outcomes, it's essential to recognize the challenges posed by the variability in traction techniques and lesion characteristics across studies, which can impact the determination of the optimal approach for different clinical scenarios. Nonetheless, the homogeneity of results and the inclusion of only RCTs reinforce the reliability of the findings. However, the concentration of studies in Asia and the diverse lesion characteristics underscore the need for caution in generalizing these results to other regions and settings. In essence, while T-ESD offers promising enhancements in procedural efficiency and safety, further research is necessary to ascertain its applicability across diverse clinical contexts and lesion types.

Appendices

Appendix one

Table 4. The quality of the evidence in the included studies reveals a high degree of certainty.

T-ESD: traction-assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection; C-ESD: conventional endoscopic submucosal dissection; MD: mean deviation

| Certainty assessment | Results summary | Importance | ||||||||||||

| Number of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Number of patients | Effect | Certainty | |||||

| T-ESD | C-ESD | Relative risk (RR) (95% CI) | Absolute (95% CI) | |||||||||||

| Dissection time: subgroup analysis | ||||||||||||||

| 9 | Randomized controlled trials | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | 736 | 741 | - | MD 10.65 lower (18.62 lower to 2.67 lower) | ⨁⨁⨁⨁ High | Important | ||

| Dissection Time: overall | ||||||||||||||

| 9 | Randomized controlled trials | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | 736 | 741 | - | MD 10.75 lower (18.76 lower to 2.74 lower) | ⨁⨁⨁⨁ High | Important | ||

| Perforation rate: overall | ||||||||||||||

| 9 | Randomized controlled trials | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | 4/736 (0.5%) | 21/741 (2.8%) | RR 0.30 (0.12 para 0.76) | 20 fewer per 1.000 (from 25 fewer to 7 fewer) | ⨁⨁⨁⨁ High | Important | ||

| Perforation rate: subgroup analysis | ||||||||||||||

| 9 | Randomized controlled trials | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | 3/736 (0.4%) | 21/731 (2.9%) | RR 0.23 (0.08 para 0.62) | 22 fewer per 1.000 (from 26 fewer to 11 fewer) | ⨁⨁⨁⨁ High | Important | ||

| Bleeding rate: overall | ||||||||||||||

| 9 | Randomized controlled trials | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | 22/736 (3.0%) | 23/741 (3.1%) | RR 0.96 (0.54 para 1.70) | 1 fewer per 1.000 (from 14 fewer to 22 more) | ⨁⨁⨁⨁ High | Important | ||

| Bleeding rate: subgroup analysis | ||||||||||||||

| 9 | Randomized controlled trials | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | 22/736 (3.0%) | 23/741 (3.1%) | RR 0.96 (0.54 para 1.70) | 1 fewer per 1.000 (from 14 fewer to 22 more) | ⨁⨁⨁⨁ High | Important | ||

| En bloc resection: overall | ||||||||||||||

| 9 | Randomized controlled trials | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | 732/736 (99.5%) | 731/741 (98.7%) | RR 1.00 (0.99 para 1.01) | 0 fewer per 1.000 (from 10 fewer to 10 more) | ⨁⨁⨁⨁ High | Important | ||

| Enbloc resection: subgroup analysis | ||||||||||||||

| 9 | Randomized controlled trials | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | 734/736 (99.7%) | 731/741 (98.7%) | RR 1.01 (0.99 para 1.03) | 10 more per 1.000 (from 10 fewer to 30 more) | ⨁⨁⨁⨁ High | Important | ||

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Author Contributions

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Felipe Giacobo Nunes, Juan Eduardo G. Dominguez, Wanderley Marques Bernardo, Eduardo G. Hourneaux de Moura

Drafting of the manuscript: Felipe Giacobo Nunes, Diogo Turiani Hourneaux De Moura, Juan Eduardo G. Dominguez, Fernando Fornari, Igor Braga Ribeiro, Guilherme Henrique Peixoto de Oliveira, Wanderley Marques Bernardo, Eduardo G. Hourneaux de Moura

Concept and design: Igor Logetto Caetité Gomes, Diogo Turiani Hourneaux De Moura, Fernando Fornari, Igor Braga Ribeiro, Guilherme Henrique Peixoto de Oliveira, Sérgio Mazzola P. de Figueiredo, Eduardo G. Hourneaux de Moura

Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Igor Logetto Caetité Gomes, Sérgio Mazzola P. de Figueiredo, Eduardo G. Hourneaux de Moura

Supervision: Diogo Turiani Hourneaux De Moura, Eduardo G. Hourneaux de Moura

References

- 1.Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer. Gotoda T, Yamamoto H, Soetikno RM. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-006-1954-3. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:929–942. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1954-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Endoscopic submucosal dissection allows curative resection of locally recurrent early gastric cancer after prior endoscopic mucosal resection. Yokoi C, Gotoda T, Hamanaka H, Oda I. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2005.10.038. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:212–218. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perspectives on endoscopic submucosal dissection training in the United States: a survey analysis. Schlachterman A, Yang D, Goddard A, Gotoda T, Draganov PV. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0044-101452. Endosc Int Open. 2018;6:0–409. doi: 10.1055/s-0044-101452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robotic-assisted surgical endoscopy: a new era for endoluminal therapies. Moura DT, Aihara H, Thompson CC. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vgie.2019.04.014. VideoGIE. 2019;4:399–402. doi: 10.1016/j.vgie.2019.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Traction-assisted colonic endoscopic submucosal dissection using clip and line: a feasibility study. Yamasaki Y, Takeuchi Y, Uedo N, et al. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0041-107779. Endosc Int Open. 2016;4:0–5. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-107779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Recent development of techniques and devices in colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Mizutani H, Ono S, Ohki D, et al. https://doi.org/10.5946/ce.2017.108. Clin Endosc. 2017;50:562–568. doi: 10.5946/ce.2017.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Endoscopic submucosal dissection with internal traction for early gastric cancer (with video) Chen PJ, Chu HC, Chang WK, Hsieh TY, Chao YC. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2007.07.021. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:128–132. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Sterne JA, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898. BMJ. 2019;366:0. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. BMJ. 2008;336:924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Endoscopic submucosal dissection of distal intestinal tumors using grasping forceps for traction. Wang F, Leng X, Gao Y, et al. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-019-02102-x. Tech Coloproctol. 2019;23:1079–1083. doi: 10.1007/s10151-019-02102-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Usefulness of the thread-traction method in esophageal endoscopic submucosal dissection: randomized controlled trial. Koike Y, Hirasawa D, Fujita N, et al. https://doi.org/10.1111/den.12396. Dig Endosc. 2015;27:303–309. doi: 10.1111/den.12396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conventional versus traction-assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection for large esophageal cancers: a multicenter, randomized controlled trial (with video) Yoshida M, Takizawa K, Nonaka S, et al. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2019.08.014. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91:55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2019.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Usefulness of the clip-flap method of endoscopic submucosal dissection: a randomized controlled trial. Ban H, Sugimoto M, Otsuka T, et al. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i35.4077. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:4077–4085. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i35.4077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conventional versus traction-assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric neoplasms: a multicenter, randomized controlled trial (with video) Yoshida M, Takizawa K, Suzuki S, et al. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2017.11.031. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:1231–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Optimal traction direction in traction-assisted gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection. Nagata M. https://doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v14.i11.667. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;14:667–671. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v14.i11.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prospective clinical trial of traction device-assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection of large superficial colorectal tumors using the S-O clip. Ritsuno H, Sakamoto N, Osada T, et al. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3572-0. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:3143–3149. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3572-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Randomized controlled trial comparing conventional and traction endoscopic submucosal dissection for early colon tumor (CONNECT-C trial) Ichijima R, Ikehara H, Sumida Y, et al. https://doi.org/10.1111/den.14426. Dig Endosc. 2023;35:86–93. doi: 10.1111/den.14426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Novel effective and repeatedly available ring-thread counter traction for safer colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Mori H, Kobara H, Nishiyama N, Fujihara S, Matsunaga T, Masaki T. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-016-5326-7. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:3040–3047. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5326-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.A new technique for endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer using an external grasping forceps. Imaeda H, Iwao Y, Ogata H, et al. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2006-925264. Endoscopy. 2006;38:1007–1010. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-925264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Traction-assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection reduces procedure time and risk of serious adverse events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lopimpisuth C, Simons M, Akshintala VS, Prasongdee K, Nanavati J, Ngamruengphong S. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-021-08452-8. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:1775–1788. doi: 10.1007/s00464-021-08452-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Training program using a traction device improves trainees' learning curve of colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Mitsuyoshi Y, Ide D, Ohya TR, et al. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-021-08799-y. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:4462–4469. doi: 10.1007/s00464-021-08799-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial gastrointestinal lesions: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline - update 2022. Pimentel-Nunes P, Libânio D, Bastiaansen BA, et al. Endoscopy. 2022;54:591–622. doi: 10.1055/a-1811-7025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Facilitating endoscopic submucosal dissection: the suture-pulley method significantly improves procedure time and minimizes technical difficulty compared with conventional technique: an ex vivo study (with video) Aihara H, Kumar N, Ryou M, Abidi W, Ryan MB, Thompson CC. https://www.giejournal.org/article/S0016-5107(14)00118-7/fulltext. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:495–502. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.01.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.A novel magnetic countertraction device for endoscopic submucosal dissection significantly reduces procedure time and minimizes technical difficulty. Aihara H, Ryou M, Kumar N, Ryan MB, Thompson CC. Endoscopy. 2014;46:422–425. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1364940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]