Summary

Background

Laryngopharyngeal reflux has classically referred to gastroesophageal reflux leading to chronic laryngeal symptoms such as throat clearing, dysphonia, cough, globus sensation, sore throat, or mucus in the throat. Current lack of clear diagnostic criteria significantly impairs practitioners’ ability to identify and manage laryngopharyngeal reflux.

Aims

To discuss current evidence-based diagnostic and management strategies in patients with laryngopharyngeal reflux

Methods

We selected studies primarily based on current guidelines for gastroesophageal reflux disease and laryngopharyngeal reflux, and through PubMed searches.

Results

We assess the current diagnostic modalities that can be used to determine if laryngopharyngeal reflux is the cause of a patient’s laryngeal symptoms, as well as review some of the common treatments that have been used for these patients. In addition, we note that the lack of a clear diagnostic gold-standard, as well as specific diagnostic criteria, significantly limit clinicians’ ability to determine adequate therapies for these patients. Finally, we identify areas of future research that are needed to better manage these patients.

Conclusions

Patients with chronic laryngeal symptoms are complex due to the heterogenous nature of symptom pathology, inconsistent definitions, and variable response to therapies. Further outcomes data are critically needed to help elucidate ideal diagnostic workup and therapeutic management for these challenging patients.

Keywords: GERD or GORD, Diagnostic tests, Oesophagus, Acidity (oesophageal)

Graphical Abstract

Background

Laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) is defined as the retrograde flow of gastric contents proximal to the upper oesophageal sphincter (UES) leading to laryngeal symptoms such as cough, throat clearing, mucus in throat, dysphonia, globus, and sore throat.1-3 Approximately 20% of adults in the US will experience chronic laryngeal symptoms;4-8 however, the presence of laryngeal symptoms does not necessarily implicate LPR as the aetiology of a patient’s symptoms. The true incidence and prevalence of LPR is unknown, as there is no diagnostic gold standard for LPR, and at present, studies vastly differ in their definition of LPR. In the current paradigm, patients with laryngeal symptoms will on average undergo 10 consultations and 6 diagnostic procedures in evaluation of their symptoms, which accounts for approximately $5,438 per patient per year, totalling $50 billion annual health care dollars.9 In addition to imparting a tremendous health care burden, it can also have a significant impact on quality of life, and further research demonstrates that patients with chronic laryngeal symptoms experience heightened levels of anxiety and depression compared to controls.10

As previously alluded to, LPR presents a significant diagnostic dilemma as classic LPR symptoms are not diagnostic of LPR,11 and a wide variety of conditions can lead to laryngeal symptoms.12 Unfortunately, despite this knowledge, 80% of patients with laryngeal symptoms will be diagnosed with LPR based solely on symptoms.4 Consequently, patients are empirically placed on proton pump inhibitors (PPI), which are no more effective than placebo when it comes to the treatment response for patients with a symptom based diagnosis of LPR.13 Based on these findings, current guidelines and practice updates suggest upfront reflux testing for evaluation of LPR in patients without typical reflux symptoms.12,14-17

To further cloud the picture is the lack of a gold standard diagnostic tool for LPR. Despite guideline and practice updates suggesting up-front reflux testing, this is not always clinically practical, and diagnostic criteria and thresholds for interpreting reflux testing in the context of LPR are lacking.14 Finally, there is growing evidence that patients with diagnostically proven LPR have non-gastroenterology (GI) associated mechanisms of symptoms including enhanced laryngeal specific hypervigilance and anxiety as well as hyper-responsive laryngeal behaviours, which suggests the need for multipronged treatment strategies that do not solely target acid reflux.10,14,18

There is a critical need to, and fortunately growing evidence to support, a move towards more precise and available methods to identify true LPR as well as integrative management approaches. The aim of this review is to discuss the current evidence based diagnostic and management strategies in patients with LPR and shed light on areas of need for future investigation.

Methods

Articles were selected to review in the following ways. Current GERD and LPR guidelines, as well as expert consensus and reviews, were evaluated and topics were included that addressed LPR and extra-oesophageal reflux. The manuscript aimed to adhere to these guidelines/expert consensuses given the breadth of topics covered in this review. Guidelines reviewed included the Lyon Consensus 2.0,19 ACG Clinical Guidelines: Clinical Use of Oesophageal Physiologic Testing,17 ACG Clinical Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease,16 AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Diagnosis and Management of Extraesophageal Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: Expert Review,12 and AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Personalized Approach to the Evaluation and Management of GERD: Expert Review.15 Pub-med search engine was also used to supplement the above and identify articles of relevance to each sub-topic discussed. Finally, novel new studies in production by the authors/co-authors were also included as relevant to the overarching theme. Articles were selected based on congruence with current guidelines, publication in high-impact journals, or novelty.

Diagnostic Modalities (Table 1)

Table 1: Diagnostic Strategies for LPR.

An overview of the current diagnostic strategies for laryngopharyngeal reflux, outlining the current recommendations and ongoing challenges/questions.

| Current Recommendations | Challenges/Questions | |

|---|---|---|

| EGD | -Indicated for evaluation of warning signs/symptoms (dysphagia, weight loss, hematemesis, melena), which may implicate more severe pathology, such as malignancy or stricture. -Allows for evaluation of the anti-reflux barrier and erosive reflux disease (Los Angeles Grade A, B, C or D esophagitis and Barrett’s Esophagus). |

-Which patients with chronic laryngeal symptoms warrant an EGD and whether certain findings on EGD are more commonly found in patients with true LPR. |

| Reflux Monitoring | -Up-front testing recommended for isolated laryngeal symptoms and for laryngeal & concomitant esophageal symptoms not responsive to PPI. -Allows for one to rule in or out conclusive GERD. |

-Value of 96-hour wireless reflux monitoring versus 24h impedance-pH testing in the diagnosis of LPR. -Whether diagnostic criteria for GERD should be used in LPR and the role of impedance metrics. |

| Salivary Biomarkers | -Currently not recommended in the evaluation of LPR, though research into salivary biomarkers (pepsin and bile acids) is promising and these are non-invasive and easy to collect. | -If salivary biomarkers (pepsin and bile acids), should be used as screening tests and/or risk stratification tools to assess for presence of GERD in patients with chronic laryngeal symptoms. -How to optimize sensitivity and specificity of salivary biomarkers. |

| Laryngoscopy | -Limited role for evaluation of reflux as findings on laryngoscopy are non-specific for LPR with poor intra and inter-observer reliability. However, certain findings may increase the pre-test probability of LPR. -Valuable to evaluate for non-reflux pathologies. |

-Whether all patients with laryngeal symptoms should be evaluated with laryngoscopy. |

| Questionnaires | -Reflux Symptom Index and Reflux Symptom Score to evaluate symptom severity. These are not recommended for LPR diagnosis. -Laryngeal Cognitive-Affective Tool to assess hypervigilance and symptom-specific anxiety. -Voice handicap index and LPR-health-related quality of life questionnaire to evaluate for impact of voice symptoms on quality of life. |

-How various therapeutics effect hypervigilance and symptom-specific anxiety. |

| Risk Factor Modelling and Phenotyping | -Shows promise; however, not recommended for current use. | -Outcomes data and randomized-controlled clinical trials are needed to determine efficacy. |

Diagnostic Modalities Introduction

At present, diagnostic tools cannot conclusively confirm gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GERD) as the cause of LPR and guidelines suggest that the diagnosis should be based on a compilation of endoscopic findings, reflux testing, and patient’s response to acid targeted therapies.12 An ideal diagnostic tool would be one that can confirm pathologic levels of gastroesophageal reflux (GER), the proximal extent of reflux, and association between symptoms and reflux; however, a test such as this does not exist,.12

Symptoms

Chronic laryngeal symptoms have a broad differential diagnosis, spanning from laryngeal pathology, post-nasal drip, sinus or allergic disorders, and pulmonary disorders, just to name a few, which can make it exceedingly challenging to rely on symptoms for a diagnosis of LPR.12 Despite this fact, there have been many tools developed to assess and quantify laryngeal symptoms. One of the most widely used questionnaires is the reflux symptom index (RSI), a validated 9-item questionnaire that assess laryngeal symptoms over the past month, with scores of >13 considered abnormal.20 Though simple and easy to administer, several limitations with this score exist, such as missing important laryngeal symptoms and combining heartburn, chest pain, regurgitation, and indigestion into a single question.21 Newer scores such as the Reflux Symptom Score,22 which is a more extensive questionnaire that evaluates a variety of upper gastrointestinal symptoms, as well as ear/nose/throat, and chest/respiratory symptoms, also exist. Though symptoms and scoring systems are useful in assessing symptom severity, these are not particularly valuable in identifying GERD as the aetiology of laryngeal symptoms,23 and the role is rather to evaluate symptom burden and therapeutic response.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD)

EGD has a well-defined role in the evaluation of classic GERD symptoms. EGD importantly enables evaluation of the anti-reflux barrier, which is the high-pressure zone between the thoracic and abdominal cavity consisting of many structures including the crural diaphragm and lower oesophageal sphincter. Assessing the axial relationship between the gastro-oesophageal junction and diaphragmatic pinch determines presence of hiatal hernia, and further evaluation of the gastro-oesophageal flap valve during retroflexion at the gastric cardia determines the radial integrity of the anti-reflux barrier. Additionally, integrity of the oesophageal epithelium is assessed during EGD. Per current guidelines, the presence of Los Angeles Grade B, C, or D oesophagitis, long-segment Barrett’s Oesophagus (≥3cm) and/or peptic stricture is indicative of conclusive GERD.15,19 The role of EGD in evaluation of chronic laryngeal symptoms is less clear.12,14 In a recent study of 756 patients with chronic laryngeal symptoms, notable endoscopic findings including erosive oesophagitis, Barrett’s Oesophagus, or hiatal hernia were present in 47% of patients. Further, the risk of identifying Barrett’s Oesophagus or Los Angeles Grade C/D oesophagitis did not differ between patients with laryngeal symptoms alone or those with laryngeal symptoms and concomitant reflux symptoms.24

Another important component of the exam includes evaluating for an inlet patch, which is an isolated area of heterotopic gastric mucosa that can be found in the proximal oesophagus. Approximately 0.1-10% of patients undergoing EGD will have an inlet patch.25 Though many patients are asymptomatic and incidentally diagnosed, some have chronic laryngeal symptoms, such as globus, due to acid or mucus produced by the inlet patch.25 Though PPIs are often ineffective in improving symptoms, some may experience improvement after endoscopic ablation.25

Given the current state of research, EGD has diagnostic value in the evaluation of chronic laryngeal symptoms when LPR is in the differential.

Ambulatory Reflux Monitoring

Ambulatory reflux monitoring is a method to assess pH of gastro-oesophageal refluxate, mainly in the distal oesophagus, as well as the association between patient reported symptoms and reflux events. The two main ambulatory reflux monitoring systems used are prolonged wireless pH monitoring and 24h impedance-pH monitoring. Prolonged wireless reflux monitoring has a higher diagnostic yield and is better tolerated when compared to 24h impedance pH-monitoring.26-28 On the other hand, 24h impedance-pH monitoring measures flow of liquid or gas and quantifies non-acid or weakly acidic reflux events, in addition to acidic reflux events. Use of 24h pH monitoring alone has fallen out of favour given availability of technically superior systems.

The standard 24h impedance-pH catheter consists of six impedance electrodes spanning the oesophageal body with a pH sensor in the distal oesophagus and is generally placed unsedated following high-resolution manometry. The catheter assembly is available in different configurations and with regards to LPR diagnosis include the multichannel intraluminal impedance with a single distal pH-catheter (MII-pH) and the hypopharyngeal-oesophageal multichannel intraluminal impedance-pH (HEMII-pH), which has impedance channels both in hypopharynx at the level of the upper oesophageal sphincter (UES) and spanning the oesophagus. The HEMII-pH probe has been an area of great interest due to its ability to detect proximal reflux episodes. At present, studies utilizing the HEMII-pH probe have revealed poor correlation with extra-oesophageal symptoms and proximal reflux,29-31 as well as poor interobserver agreement regarding pharyngeal reflux events.32,33 In addition, normative values for hypopharyngeal events varies between studies, making it difficult to ascertain accurate diagnostic criteria for LPR.34-37 For these reasons, current guidelines recommend against the use of HEMII-pH monitoring for a diagnosis of LPR.16 The potential benefit of 24h impedance-pH monitoring over prolonged wireless reflux monitoring, includes the ability to characterize all types of reflux (acidic, weakly acidic, and non-acid reflux), as well as gaseous reflux events, with some studies demonstrating specific benefit in patients with chronic cough.38,39

Wireless pH monitoring consists of a pH capsule that is affixed to the oesophageal mucosa, generally during a sedated EGD. The battery life of the wireless pH recorder enables prolonged reflux monitoring for up to 96 hours. Prolonged monitoring is associated with higher diagnostic yield, ability to capture variability in daily acid exposure in patients with GERD, as well as associated with treatment outcomes.28,40-45 Wireless pH capsule placement is also better tolerated than transnasal catheter placement.26,27 Thus, prolonged wireless pH monitoring is the preferred testing modality for patients presenting with typical GERD symptoms.15

Both ambulatory reflux monitoring systems enable measurement of distal oesophageal acid exposure, which is the primary metric of interest. Per the Lyon Consensus 2.0, for 24h impedance pH-monitoring criteria for conclusive GERD off PPI include an acid exposure time (AET) of >6. Total reflux episodes of > 80 per 24 hours is adjunctive evidence for conclusive GERD, whereas an acid exposure time of 4-6 or 40-80 reflux events per 24 hours is indicative of borderline criteria and inconclusive as independent metrics.19 Diagnostic criteria for conclusive GERD on prolonged wireless pH monitoring include ≥ 2 days with AET > 6% and borderline criteria are ≥ 1 day with acid exposure time ≥ 4.0%. Aside from AET, other metrics have been developed to diagnose GERD during ambulatory reflux monitoring. For example, the DeMeester score, which is primarily used in the surgical literature, is a composite of six variables measured during prolonged wireless pH monitoring.46 Scores of 14.7 or greater indicate the presence of GERD with scores of > 100 denoting severe GERD.47 Further, during ambulatory reflux monitoring patients are instructed to record meal times, recumbency and symptom events on the recorder. Symptom recording enables evaluation of symptom reflux association. The symptom index is the percentage of recorded symptom events preceded by an reflux episode and the symptom association probability assesses the probability that a recorded symptom event and reflux episode are associated.19 A symptom index of >50% and a symptom association probability of > 95% meet criteria for a strong positive symptom reflux association.19 Reliability with patient report of symptoms is a limitation of symptom reflux monitoring.48,49

Ambulatory reflux monitoring is the gold standard tool to diagnose GERD, and should be performed off PPI therapy in patients without proven reflux disease.15,16,19 Ambulatory reflux monitoring is the reference diagnostic standard for LPR and current guidelines suggest use of up-front reflux monitoring in patients with isolated chronic laryngeal symptoms and in patients with concomitant oesophageal symptoms who fail PPI therapy.12,15-17 However, the role of ambulatory reflux monitoring is less understood in the field of LPR compared to GERD.12 Uncertainties surround diagnostic thresholds, which reflux monitoring system to utilize, as well as the importance of measuring proximal reflux burden in the evaluation of LPR persist.14 For instance, controversy exists surrounding the optimal reflux monitoring system for LPR diagnosis. Some data supports the utility of 24h impedance-pH due to the ability to detect proximal reflux whereas other data highlights higher diagnostic yield of wireless pH monitoring for LPR. In a recently published multicentre study of 813 patients with chronic laryngeal symptoms investigators identified higher diagnostic yield of pathologic GERD on prolonged wireless pH monitoring compared to 24h impedance-pH, even when taking into account non-acidic and weakly acidic reflux events identified on impedance-pH monitoring.50 Another complicating factor is that the presence of conclusive GERD on reflux monitoring does not necessarily attribute GERD as the aetiology of symptoms.12

Overall, ambulatory reflux monitoring is a key diagnostic test in evaluating patients with LPR. Further research is needed to help elucidate diagnostic thresholds and the best diagnostic system to optimize patient outcomes.

Oropharyngeal pH Monitoring

In 24h oropharyngeal pH monitoring, a transnasal catheter is placed in an office setting with the single pH sensor positioned one cm below the uvula which has ability to measure pH in liquid and aerosolized droplet form.51 Two major limitations of this probe are the inability to determine if a pharyngeal reflux event is occurring simultaneously with the oropharyngeal event as well as the inability to detect non-acid events. The data supporting the use for oropharyngeal pH monitoring has overall been mixed.12 Some studies have shown utility,52,53 while others have revealed a poor association with oesophageal reflux monitoring, as well as an inability to distinguish between asymptomatic patients.51,54-56 For these reasons, oropharyngeal pH monitoring has fallen out of practice and is not a recommended diagnostic tool for LPR.56

Laryngoscopy

Laryngoscopy is an office-based test in which a flexible laryngoscope is passed transnsasally to examine the larynx. Historically, laryngoscopy was regarded as a diagnostic gold standard to ascribe GERD to laryngeal symptoms; however, research has supported that laryngoscopy is not specific nor reliable, as many signs that are thought to be reflux induced can be seen in patients without reflux.57-59 Signs of laryngoscopy that have been suggestive of LPR include thickening, erythema, and oedema in the posterior larynx, contact granuloma, and pseudosuculus.60 In an attempt to standardize laryngoscopic evaluation in LPR, the Reflux Finding Score (RFS) was introduced, which quantifies the severity of 8 items on laryngoscopy, however, concerns regarding the validity and inter and intra-observer reliability exist61,62 and thus there is significant debate as to the utility in clinical practice.12 Therefore, per current best practices, laryngoscopy is not a diagnostic tool for LPR. Nonetheless, laryngoscopic examination remains a cornerstone to evaluate for laryngeal pathology in patients with laryngeal symptoms to rule out other aetiologies, especially malignancy, which can mimic laryngeal symptoms.12

Models to Predict LPR

Many patients with chronic laryngeal symptoms do not have evidence of GERD on testing and thus it is important to develop models and tools which can identify patients at high or low likelihood of having pathologic reflux disease in attempt to avoid over-utilization of testing or treatment.

In a latent class analysis study of 302 adults with chronic laryngeal symptoms, researches identified 5 distinct clinico-physiologic patient phenotypes: Group A – LPR/GERD with hiatal hernia, Group B – LPR/mild GERD, Group C – No LPR/GERD, Group D – Reflex Cough and Group E – Obstructive oesophagogastric junction/No LPR.63 The authors concluded that patients with chronic laryngeal symptoms constitute distinct mechanistic subgroups, which likely relates to variability in symptom and treatment response. Thus, utilizing phenotyping in clinical practice could help provide individualized and targeted treatment plans.63

One model to risk stratify patients and thereby guide diagnostic testing is known as the HAs-BEER score (Heartburn, Asthma, and body mass index > 25 in extra-oesophageal reflux). Authors proposed that patients with a low HAs-BEER score have a low risk of GERD and thus warrant ambulatory reflux testing off acid suppression whereas patients with an elevated HAs-BEER score are at higher risk of GERD and warrant ambulatory reflux testing on acid suppression.64 More recent guidelines assert that all patients with unproven GERD should undergo testing off acid suppression.12,15-17

The COuGH RefluX score is a more recently developed and externally validated risk stratification model consisting of Cough, Overweight/obesity, Globus, Hiatal Hernia, Regurgitation, and male seX. The COuGH RefluX score has an AUC of 0.67 (95% CI 0.62, 0.71) with 79% sensitivity and 81% specificity for proven GERD. A score of 2.5 or lower identifies groups at low risk of GERD, who may not require further testing, and a score of 5.0 or higher identifies groups at high risk of GERD for whom management as a first step may be appropriate.65

These types of risk prediction models are particularly useful and easy to apply in clinical practice; however, prospective studies are important to determine if these models help predict symptom response and patient outcomes.

Novel Diagnostic Approaches – Salivary Biomarkers

Biomarkers to help identify disease pathology is an evolving area of research. Though saliva is predominately composed of water, there is a growing body of literature into the complex and rich microenvironment that exists, which can help with diagnosis of a variety of disease processes, such as GERD and LPR.66 These testing strategies hold great intrigue due to the fact that they are non-invasive, can be collected in an office-based setting, relatively affordable, and more accessible than other testing modalities. In the evaluation of GERD and LPR, a few salivary biomarkers have been investigated: pepsin, bile acids, and the microbiome.

Salivary Pepsin

Pepsinogen is an endopeptidase that is secreted by gastric chief cells and activated to pepsin through the acidic environment of the stomach and has been studied as a biomarker in GERD and LPR.66 Pepsin has historically been measured through enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay,67 via its ability to digest fibrinogen,68 and through Western blot.69 More recently pepsin has been measured using a lateral flow device, which uses monoclonal antibodies against pepsin to quickly ascertain the pepsin concentration in a given sample.66 One such device is the Peptest (RDBiomed, UK). The diagnostic utility of salivary pepsin as a biomarker for GERD has yielded varying sensitivities and specificities, which is likely based on time of collection, method of collection, and diet.66,70,71 Woodland et al. studied salivary pepsin via Peptest in 45 patients with GERD, hypersensitive oesophagus, and functional heartburn based on 24h impedance-pH monitoring, though diagnostic criteria was not specified. Based on their prior work, they defined a concentration of > 210 ng/mL as positive.72 Pepsin was collected over 3-days (timing of collection nor if patients were fasting was not specified) and no significant difference was found in pepsin concentration in PPI responders versus nonresponders nor maximal pepsin concentration in the symptomatic patient groups.73 Since then, a handful of studies have been conducted, with variable sensitivities and specificities.74-77 To better identify optimal collection protocol, researchers studied salivary pepsin via Peptest, collected at various times of day. Utilizing wireless pH monitoring as the diagnostic gold standard, the authors identified substantial agreement for fasting morning concentrations over 3 days whereas concentrations among post-prandial and evening samples were variable. The authors determined that a single AM pepsin level of 25 ng/mL was 67% accurate for GERD with a sensitivity of 56% and a specificity of 78%.78 In a combined meta-analysis of 16 studies evaluating salivary pepsin via Peptest, the pooled AUC for GERD/LPR was 0.70 for GERD/LPR. Most studies, but not all, utilized 24h impedance-pH testing, and it is unclear if all studies were conducted in the fasting state.79

When evaluating LPR, Zelenik et al. utilized Peptest for fasting morning pepsin detection and based on 24h impedance-pH monitoring found the sensitivity and specificity, based on six hypopharyngeal reflux episodes, were 37% and 82%, respectively, and based on DeMeester score were 27% and 63% respectively.80 Wang et al. conducted a meta-analysis of 11 studies in children and adults with chronic laryngeal symptoms. Seven studies utilized pH monitoring for a diagnosis and 8 utilized Peptest, though timing of pepsin and whether it was fasting was unknown. A pooled sensitivity and specificity were 65% and 68% respectively with an AUC of 0.71 for LPR.81 Unfortunately, significant heterogeneity with regards to timing of pepsin collection, as well as diagnostic gold standard used for diagnosis exists, and thus as suggested by current best practices, more evidence is necessary to provide a recommendation on the role of salivary pepsin in the evaluation of LPR.12

Salivary Bile Acids

Bile acids are another biomarker of growing interest in GERD and LPR. Bile acids are found in hepatocytes, stored in the gallbladder, and secreted into the duodenum, with their main functions including fat metabolism, removal of cholesterol, and absorption of fat soluble vitamins.66 Bile acids are thought to exert their negative effects in several ways. At a pH of ≤ 4, conjugated bile acids tend to be un-ionized increasing their propensity to penetrate the cell membrane and inflict damage. At pH ranges of 5.5-7.0 most conjugated bile acids are ionized and inactive; however, some bile acids remain unionized with injurious potential.82 In addition, glycine conjugates may be unionized and more corrosive at higher pH levels.83 Bile acid reflux is suspected to contribute to refractory GERD.84 In a pilot study of 20 healthy subjects, 20 patients with GERD symptoms controlled on PPIs, and 34 patients with PPI refractory GERD, patients with PPI refractory GERD had significantly higher total salivary bile acids, as measured by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry, compared to healthy controls and patients with PPI controlled GERD.85

In LPR, Sereg-Bahar et al. evaluated 28 patients with at least two laryngeal symptoms versus 48 controls. Utilizing 24h impedance-pH, with a positive study defined as reflux of gastric contents to the larynx, they found significantly higher bile acids in the saliva, as measured by an Olympus AU600 biochemical analyser, when comparing LPR patients to controls.86 De Corso et al. investigated 62 patients with laryngeal symptoms who underwent 24h impedance-pH testing, with a negative test defined as <1 proximal reflux episode and AET of <0.5%. Bile acids were measured via Olympus-AU400 analyser, utilizing a colorimetric method, with a level of ≥ 0.4 μmol/L considered positive. Significantly higher bile acid concentrations were present in patients with more severe LPR symptoms as well as patients with alkaline/mixed LPR compared to acidic LPR.87 In a recent pilot study of 35 participants, salivary bile acids were higher in patients with objective LPR compared to other groups (healthy controls, patients with GERD/LPR symptoms but without pathologic acid reflux, and patients with objective GERD). In this study, salivary bile acids were 100% specific (95% CI: 63%, 100%) with an AUC of 0.73 (0.57, 0.88) for elevated AET in patients with laryngeal symptoms.88

In summary, salivary bile acids are quantifiable in saliva and may have diagnostic potential in LPR.

Microbiome

The microbiome plays an important role in overall health, and in particular, gut health. This is an area of growing knowledge and there is minimal research into the interaction of the microbiome and the aerodigestive tract.89 Studies in GERD and Barrett’s Oesophagus have identified reduced Streptococcus species and increased Neisseria, Proteobacteria, Veillonella, and Fusobacterium.89 In 55 patients with reflux oesophagitis, Wang et al. detected lower levels of Proteobacteria and higher levels of Bacteroidetes in salivary samples, when compared to 51 controls.90 In another study by Kawar et al., patients with a symptom-based GERD diagnosis and managed with PPI, showed minimal differences in their microbiome composition when compared to healthy controls off PPI, whereas patients with a symptom-based GERD diagnosis not treated with PPI, had lower levels of certain taxa.91 In a pilot study of 73 symptomatic and 12 asymptomatic patients conducted by Ma et al., patients with salivary pepsin of ≥25 ng/mL had significantly greater Shannon entropy diversity compared to those with normal pepsin.92 Though no studies have directly evaluated the microbiome in LPR, this is an interesting area of inquiry that is ripe for investigation.

Disorders of Brain-Larynx Interaction, Laryngeal Hypersensitivity, and Quality of Life Impairment

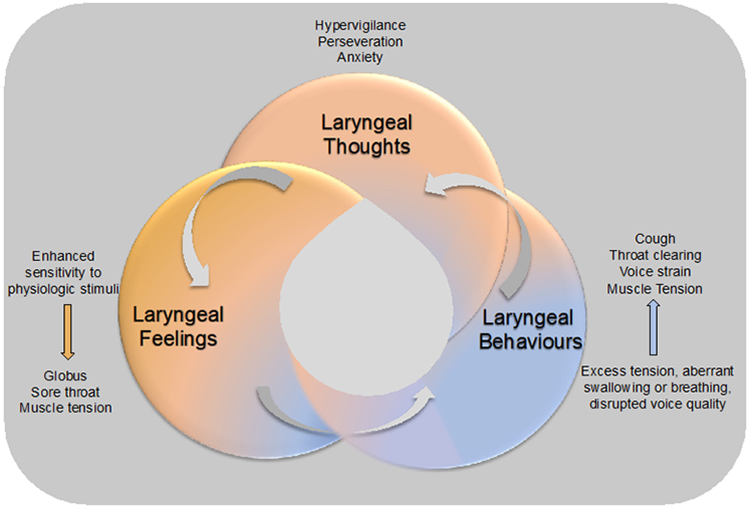

An under-appreciated area of research regarding chronic laryngeal symptoms is the brain-larynx interaction (Figure 1). Various cognitive affective processes including hypervigilance and symptom specific anxiety can drive laryngeal symptom burden. Hypervigilance, or the enhanced attentiveness and discomfort from physiologic stimuli, can present as increased focus on certain laryngeal sensations that are exacerbated in social situations. Symptom-specific anxiety is the persistent distress and worry over laryngeal symptoms and their perceived consequences, such as a fear of throat cancer in a patient with a cough, Laryngeal hypersensitivity and symptom-specific anxiety may occur as a result of physiologic or pathologic triggers, such as after an incident insult from an upper respiratory tract infection or aspiration event, or in conjunction with another chronic condition, such as asthma or GERD, leading to laryngeal sensitization. Laryngeal sensitization enhances perseveration and nociception (manifesting as hypervigilance or symptom-specific anxiety), and cascade to hyper-responsive behaviours in the larynx such as throat clearing or voice strain.93 Patients with an enhanced brain-larynx interaction present with identical symptoms as those with primary LPR, and thus these disorders are difficult to distinguish from one another. Further, an enhanced brain-larynx interaction can coexist with true LPR, just as patients with GERD or oesophageal motility disorders can have concomitant oesophageal hypersensitivity.94 For example, in one study, researchers evaluated the Oesophageal Hypervigilance and Anxiety Scale (EHAS) in patients with chronic laryngeal symptoms and identified similarly elevated EHAS scores across patient groups with or without objective GERD.18 Similarly, Wong et al. identified increased oesophageal hypervigilance and symptom-specific anxiety in patients with both GERD and LPR symptoms, LPR predominant, and GERD predominant symptoms when compared to controls, and once again, reflux burden did not differ across groups.95

Figure 1: The Brain-Larynx Interaction.

A diagram outlining the brain-larynx interaction, demonstrating how laryngeal thoughts, laryngeal feelings and laryngeal behaviours are all intertwined and can lead to exacerbations of symptoms.

With increased recognition of these important processes, significant efforts to focus on tools to measure laryngeal specific hypervigilance and symptom-specific anxiety are required. For instance, the Laryngeal Cognitive-Affective Tool is a recently validated patient reported outcome instrument that in which a score of 33 or higher reflects elevated laryngeal associated hypervigilance and symptom-specific anxiety.96 This questionnaire can be used in clinical and research practice to help clinicians better understand symptom burden and perception, and further guide therapies targeting these cognitive affective processes.

Other questionnaires exist that evaluate the impact of laryngeal symptoms on patient quality of life. For example, the Voice Handicap Index is a 30-tem validated questionnaire that assess voice symptoms and the impact on an individual’s life, with scores of 31-60 indicating moderate symptoms and 61-120 indicating severe symptoms.97 The validated LPR-health-related quality of life questionnaire consists of 43 items and assess the impact of laryngeal symptoms on health related quality of life, with higher scores denoting more severe symptoms.98 Both of these questionnaires are useful in assessing the impact of laryngeal symptoms on patient quality of life.

Diagnostic Modalities Conclusions

In conclusion, a single diagnostic testing modality that can reliably identify GER as the aetiology of a patient’s chronic laryngeal symptoms is lacking. What is needed to both diagnose and adequately treat a patient is a composite of tools. Ideally, a highly sensitive test that is non-invasive and accessible could risk stratify likelihood of GERD and thereby identify which patients should undergo additional testing for GERD. At the same time, assessment for cognitive affective processes, hyper-responsive behaviours, and hypersensitivity could identify alternate non-GERD mechanisms at play and guide integrative treatment models.

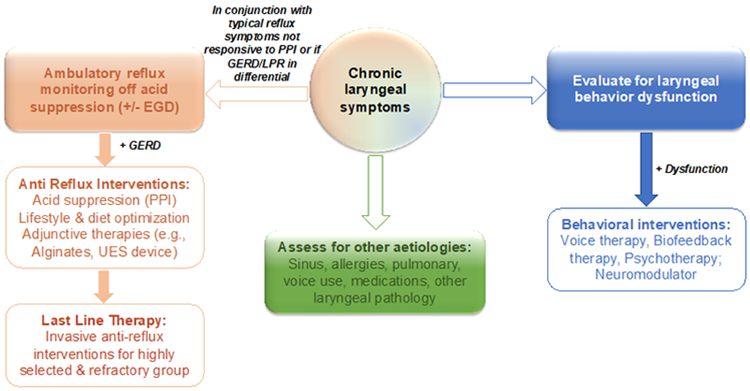

An Overarching Perspective on Goals of Management (Figure 2)

Figure 2: Therapeutic Approaches for Chronic Laryngeal Symptoms.

A diagram outlining the therapeutic approaches for managing patients with chronic laryngeal symptoms.

Goals of Management Introduction

At present, research into LPR therapeutics is limited by the lack of a gold-standard diagnostic tool. Unfortunately, this has led to significant variability in diagnostic criteria utilized in outcomes-based research, which drastically limits one’s ability to apply these results in clinical practice. In addition, patients with chronic laryngeal symptoms have heterogenous symptoms presentations with various disease pathologies, which further complicates our understanding of how to manage these patients. To help clarify therapeutic response, as appropriate, diagnostic criteria utilized in studies are outlined below.

Dietary and Lifestyle Therapy

Certain dietary strategies have shown efficacy in LPR. One theory is that a primarily plant-based diet, low in animal proteins, decreases the amount of amino acids in the stomach and can indirectly decrease gastric secretion and pepsin, consequently preventing damage to the susceptible oropharyngeal environment .99 As a result of this hypothesis, Zalvan et al. aimed to determine if a 90% plant-based, Mediterranean-style diet with alkaline water and standard reflux precautions were more effective than PPI and standard reflux precautions in 184 patients diagnosed with LPR based on RSI score. The percentage reduction in RSI for the diet group was 39.8% versus 27.2% in the PPI cohort, and the difference was significant (12.10, 95% CI 1.53, 22.68). No significant difference was seen in the percentage achieving a 6-point reduction in RSI score (54% in the PPI cohort versus 63% in the diet cohort).99 Supporting this finding, Lechien et al. assessed patients with chronic laryngeal symptoms who had a diagnosis of LPR based on more than one proximal reflux episode on 24h impedance-pH monitoring. Patients consuming diets high in fat, low in protein, high in sugar, and acidic in nature had higher numbers of proximal reflux episodes on 24h impedance-pH monitoring when compared to those who did not.100 Ultimately, the literature supports a dietary approach in appropriately motivated patients who prefer to avoid pharmacologic therapies; however, future research is necessary to truly determine the effectiveness for dietary therapies in LPR. Other dietary strategies utilized in clinical practice are similar to those of GERD which include avoiding trigger foods, eating smaller meal portions, and waiting at least 2-3 hours between eating and recumbency.12

Weight loss remains one of the most effective lifestyle interventions for GERD and is often also recommended in LPR.12 In a prospective cohort study conducted by Singh et al. a structured weight loss program in 332 obese patients led to a significant weight loss and significant improvement in GERD symptoms.101 A dose-dependent association between weight loss and improvement in GERD symptoms was also seen in the HUNT study, a prospective population-based cohort study of 29,610 individuals in Norway.102 In LPR, Halum et al. retrospectively reviewed 500 consecutive pH-probe studies and determined that pharyngeal reflux events, defined as one or more pharyngeal reflux events at a pH of <4, were not elevated in obese patients.103 Lechien et al. prospectively evaluated 262 patients with laryngeal symptoms undergoing pH testing with the HEMII-pH probe, with LPR diagnosed when one or more acid or non-acidic hypopharyngeal reflux events were present. The authors found that obesity was associated with a higher prevalence of GERD, acidic LPR events, including pharyngeal events, and higher reflux symptom scores.104 Though these data in LPR are interesting, further studies are needed to fully understand the relationship between obesity and LPR.

Other lifestyle interventions associated with symptom improvement include head of the bed elevation to decrease reflux overnight12 and sleeping in the left lateral decubitus position.105 The rationale for sleeping in the left lateral decubitus position is anatomical, in that the stomach is located above the oesophagus in the right lateral decubitus position and thus leads to more reflux. This theory was supported by Schuitenmaker et al. in a single-centre, double-blind, randomized, sham-controlled trial in 100 patents with nocturnal GERD symptoms which showed that sleeping in the left lateral decubitus position led to symptom improvement.105

Ultimately, dietary and lifestyle therapies are one strategy, which can be either combined with other therapeutics or trialled alone, to improve patient symptoms.

Acid Suppressive Therapies

PPIs serve as both a diagnostic and therapeutic strategy in patients with chronic laryngeal symptoms. PPIs suppress gastric acid secretion so that refluxate is less acidic, which is thought to be a potential driver of symptoms in patients with LPR. From a diagnostic standpoint, current guidelines recommend in patients with extraoesophageal symptoms with concomitant typical GERD symptoms, an 8-12 week trial of an initial single-dose PPI, uptitrating to twice daily; however, in patients with isolated extraoesophageal symptoms, up-front testing is recommended.12,15,16 However, clouding this picture is that PPI responsiveness does not necessarily confirm a diagnosis of GERD as the aetiology of a patient’s chronic laryngeal symptoms, which ultimately may lead a clinician to pursue additional testing.12

With regards to symptom improvement, One of the largest multi-centre, randomized-controlled trials to-date including 220 patients found that in patients with chronic throat symptoms, there was no statistically significant difference between placebo and lansoprazole 30mg BID at 16 weeks.13 Reviews and meta-analyses have been mixed as to the efficacy of PPI for chronic laryngeal symptoms12,21,106-109 Cosway et al. helped to explain these variable findings by conducting a systematic review of 10 published systematic reviews, demonstrating that 9 of the 10 studies had high risk for bias, and thus concluded that the quality of evidence regarding PPIs in patients with chronic throat symptoms “gives serious cause for concern.”110 The reasoning behind these inconsistencies is multifactorial including study design, diagnostic criteria for LPR, PPI choice, dosing/frequency of PPI, and duration of PPI treatment.94 However, several critical issues come to the forefront when determining effectiveness of PPI treatment in patients with chronic laryngeal symptoms. First, chronic laryngeal symptoms are nonspecific and can be due to a wide array of disease pathologies. Secondly, most studies evaluating LPR use various diagnostic modalities, such as laryngoscopy and symptom-based questionnaires, which are not recommended as diagnostic modalities in patients presenting with chronic laryngeal symptoms.94 Furthermore, even when ambulatory reflux monitoring is used, it is unclear what type of reflux monitoring system should be used (prolonged-wireless reflux monitoring or 24h impedance-pH monitoring) nor if traditional pH and reflux thresholds for GERD can be applied to patients with chronic laryngeal symptoms.14,94 Consequently, it is reasonable to reserve a PPI trial for patients with chronic laryngeal symptoms and concomitant GERD symptoms and perform up-front reflux testing in those with isolated laryngeal symptoms. If patients are proven to have pathologic acid reflux based on traditional reflux parameters, it is worthwhile to trial a PPI to ascertain if patients experience symptom improvement.

Other medications targeting acid suppression include Histamine 2 receptor antagonists (H2RA) and over-the-counter antacids. H2RA are not recommended as first-line therapy in patients with LPR due to their limited duration of action, low potency, and tachyphylaxis with continued use. Research into H2RA use in LPR patients is limited. In a study by Rackoff et al., 39 patients with GERD symptoms (17 with predominant typical symptoms, 6 with predominant atypical symptoms, and 16 with mixed typical and atypical symptoms) taking twice daily PPI and nighttime H2RA were interviewed about their symptoms, 72% reported improvement in overall symptoms and 74% in nighttime symptoms, with 5% stopping the H2RA due to weaned efficacy after 1 month.111 This study is limited by its observational nature and recall bias. In addition, which symptoms responded to H2RA were not specified. Mcnally et al. evaluated 6 patients with confirmed GERD and voice hoarseness, after treatment with Ranitidine for 12 weeks, only 2 patients felt their hoarseness was improved.112 Based on current guidelines, the main role for H2RA in LPR is as an adjunct for breakthrough symptoms.12,94 Similarly to H2RA, over-the-counter antacids are unlikely to provide lasting symptom relief in patients.

Alginates

Alginates, derived from algae, are an oral medication that forms a mechanical raft above gastric contents, thereby creating a barrier for GER, regardless of the composition or acidity and can help block other irritants such as pepsin113 and bile salts94 from encountering the oesophageal mucosa.

In LPR, most studies have yielded positive results when alginates are used. In a randomized clinical trial of 49 patients with RSI scores > 10 and RFS scores > 5, McGlashan et al. demonstrated significant symptom improvement in RSI at follow-up in patients treated with Gaviscon Advance (10mL four times daily after meals and at bedtime), compared to no treatment.114 The study is limited by the symptom and laryngoscopic based diagnosis as well as the lack of blinding or a placebo group. Tseng et al. evaluated 80 patients with RSI of > 10 and RFS > 5 and randomized them to either placebo or Alginos Oral Suspension (sodium alginate 1,000mg three times daily). Both groups experienced significant improvement in total RSI and number of reflux episodes on 24h impedance-pH monitoring, and thus superiority was not proven.115 Notably all patients received lifestyle modifications, which could account for the lack of a difference between groups. In a non-inferiority randomized controlled trial of 50 patients with RSI ≥ 13 and RFS ≥ 7, Pizzorni et al. demonstrated that patients treated with alginates (Gastrotuss 20mL, three times per day) or Omeprazole 20mg daily had significant improvement in mean RSI, and alginates were non-inferior to PPIs.116

Based on this information, alginates are a reasonable therapeutic option in patients with LPR.

Baclofen

Baclofen is a gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor type-B agonist and consequently inhibits transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxations, the primary mechanism of GER.117 Although the majority of research on baclofen has been in GERD,118 baclofen has been shown to have efficacy in patients with a primary symptom of chronic cough. Dong et al. compared the effectiveness of gabapentin and baclofen in patients with confirmed GERD and suspected refractory GERD induced cough, similar rates of symptom improvement were seen; however, baclofen was associated with more side effects.119 The utility of baclofen in LPR is unknown due to a paucity of data; however, similar to GERD, use of baclofen is likely limited by its side effect profile.12,94

Pharmacologic Neuromodulation

While most studies on pharmacologic neuromodulation in patients with chronic laryngeal symptoms centre around chronic cough, some of these strategies may be applied to patients with laryngeal hypersensitivity.94 From a physiologic standpoint, neuromodulators may be beneficial in chronic cough due to central and peripheral sensitization experienced by these patients.120

With regards to chronic cough, in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial gabapentin (up to 1800 mg/day), led to improved symptoms of cough when compared to placebo.120 In fact, the CHEST guidelines recommend practitioners consider a trial of gabapentin in patients with chronic cough that is otherwise unexplained.121 Pregabalin has also been effective in a retrospective chart review of 12 patients with laryngeal sensory neuropathy.122 In a randomized controlled trial comparing amitriptyline and cough suppressants, amitriptyline improved symptoms of chronic cough; whereas, cough suppressants did not.123

Pharmacologic neuromodulation should be considered in appropriate patients with suspected laryngeal hypersensitivity. However, additional research into pharmacologic neuromodulation in management of chronic laryngeal symptoms is necessary to truly understand which patients may benefit from these therapies.

Speech Therapy

Speech therapy is effective in several chronic laryngeal symptoms as laryngeal irritation can lead to maladaptive sensory responses and chronic motor behaviours which are modifiable by behavioural retraining therapy.124 Voice therapy for chronic laryngeal symptoms focuses on individualizing treatments and globally working on improving laryngeal health, decreasing vocal demand and balancing vocal technique.124 There are several proposed mechanisms of dysfunction based on the specific symptom a patient presents with. For example, in patients with coughing/throat clearing, the underlying dysfunction may be laryngeal irritation or reduced laryngeal reflux threshold, which are mechanisms that can be targeted by a speech language pathologist.124 Other potential areas that voice therapy may improve include dysphonia, increased mucus, or globus sensation.124 Clinical practice guidelines for dysphonia125 and chronic cough121 recommend considering voice therapy in patients with these symptoms. Overall, speech therapy is effective in certain patients with chronic laryngeal symptoms, and should be considered in management of these complex patients.124

Behavioural Therapy

There is limited research into behavioural therapies for patients with chronic laryngeal symptoms. Behavioural therapy targets the perseverant and nociceptive properties of laryngeal symptomatology;126 and thus guidelines suggest hypnotherapy and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) may have a role in patients with chronic laryngeal symptoms.12

Hypnotherapy has been primarily used in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome; however, a growing body of literature has shown efficacy in upper GI disorders.127 During hypnotherapy, a health psychologist will instruct the patient on how to modulate uncomfortable physiologic sensations and symptoms.128 Hypnotherapy may be effective in dyspepsia, globus sensation, heartburn, dysphagia, and non-cardiac chest pain; however, further research into the efficacy in patients with chronic laryngeal symptoms is warranted.127

CBT, like hypnotherapy, has significantly more research in patients with bowel disorders of gut-brain interaction; however, has also been suggested as a treatment modality in patients with oesophageal diseases.128 CBT may be particularly helpful in patients who catastrophize and have trouble coping. The two main goals of CBT are to understand the origin of maladaptive behaviours and to provide strategies for managing these unhealthy behaviors.128

Though research is limited, behavioural therapies practically seem to have an important role in patients with chronic laryngeal symptoms, as evidenced by the success in other disorders of gut-brain interaction; however, additional investigation is required to confirm effectiveness in patients with chronic laryngeal symptoms.

UES Augmentation

One of the novel therapeutics for LPR has been development of the external upper oesophageal sphincter (UES) compression device, which applies a constant 20 to 30 mmHg of cricoid pressure, increasing the intraluminal UES pressure, and providing an augmented barrier to pharyngoesophageal reflux.129 In a pilot study, 15 patients with an RSI ≥ 13 experienced significant improvement in symptoms with use of the UES compression device.130 In a prospective clinical trial, 31 patients with 8 or more weeks of laryngeal symptoms were given double-dose PPI for 4 weeks and then the UES compression device was added for a an additional 4 weeks. There was a non-significant decrease in RSI with PPI alone; however, a significant decrease after PPI was combined with the UES compression device.131 The device was well-tolerated and there were no serious adverse events, with just 1 patient reporting collar bone discomfort that resolved and 7 discontinued use due to intolerance, no improvement in symptoms, or a rash.131 Given the findings, the UES compression device is a useful adjunct in patients with LPR.12

Endoscopic and Surgical Interventions

Current guidelines for the use of endoscopic and surgical interventions for patients with LPR state that patients should only be referred when there is objective evidence of GERD and warn that PPI nonresponse predicts lack of response to anti-reflux surgery, and thus this should be factored into the decision-making process.12

Several reviews have investigated the effectiveness of surgical interventions for LPR. In a review of 27 observational studies, the effectiveness of anti-reflux surgery was anywhere from 10-93%.132 In a systematic review by Lechien et al., 34 retrospective and prospective studies of fundoplication in patients with LPR were reviewed, there was a high degree of methodological heterogeneity, leading the authors to conclude that their findings were inconclusive as to the effectiveness of surgery for LPR.133 In a retrospective review of 86 patients with objective GERD by Ward et al. a significant improvement was seen in RSI after magnetic sphincter augmentation (MSA), leading the authors to conclude that this is an effective treatment for typical and atypical GERD symptoms.134 To better understand what patients may respond to therapy, Krill et al. performed a retrospective review of 115 adults with conclusive GERD. Patients with extra-oesophageal symptoms had less predictable response to anti-reflux surgery when compared to patients with typical GERD symptoms, and response to acid suppressive therapy was correlated with anti-reflux surgery effectiveness in patients with atypical GERD symptoms.135

Transoral incisionless fundoplication (TIF) is a potential endoscopic intervention for patients with GERD/LPR. Trad et al. performed TIF in 34 patients, 15 with typical GERD symptoms and 13 patients with atypical symptoms, all of whom underwent EGD, with 24 also undergoing ambulatory reflux monitoring. At a median of 14 months follow-up, RSI score decreased from 19.2 to 6.1 after TIF (p<0.001).136 Snow et al. similarly showed in 49 patients with refractory LPR symptoms (RSI >13) and either erosive oesophagitis, Barrett’s oesophagus, and/or pathologic acid reflux undergoing TIF or TIF with hiatal hernia repair, 85% had normalization of their RSI post-procedure.137

The current literature for anti-reflux surgical or endoscopic interventions in patients with LPR is mainly prospective or retrospective and varies in methods and inclusion criteria. Randomized controlled trials with guideline-based inclusion criteria are important to better delineate which patients are most likely to improve with surgical or endoscopic intervention.12 Consequently, guidelines recommend considering surgery only in a highly selected group of patients with LPR who also have symptoms of heartburn and/or regurgitation, who previously responded to PPI therapy, and those with a high burden of acidic refluxate on pH monitoring.12 It is critical to carefully weigh the risks, benefits, and alternatives to surgical or endoscopic therapies, and use shared decision-making between the patient and clinician to achieve optimal outcomes.12

Goals of Management Conclusions

In conclusion, a variety of therapeutic modalities exist for patients presenting with chronic laryngeal symptoms. As a result of the various diagnostic strategies utilized by authors in outcomes-based research, clinicians must be cautious when applying the results of these studies to their patients.

Conclusions and Future Research

Chronic laryngeal symptoms are challenging to manage due to the heterogenous nature of symptom pathology, inconsistent definitions, and variability in patient response to therapies. Researchers are developing methods to phenotype patients and create risk prediction models to identify groups of patients that may benefit from certain targeted therapies;63-65 however, further outcomes data is required to validate these findings. It is clear from the literature that not all patients with chronic laryngeal symptoms experience pathologic reflux and that elevated hypervigilance and symptom-specific anxiety may exacerbate symptoms. Most studies to date have utilized symptom-based diagnostic strategies or variable diagnostic criteria on physiologic testing to diagnose LPR; likely contributing to the heterogeneity in treatment response that is seen in the literature. Many questions remain surrounding chronic laryngeal symptoms that are ripe for investigation.14 First off, understanding methods and metrics to diagnose LPR is of the utmost importance. Specifically, there is a need to determine the optimal ambulatory reflux monitoring modality for evaluating LPR and better recognize how impedance metrics can aid in our understanding of the physiologic underpinnings of chronic laryngeal symptomatology. In addition, numerous studies have revealed significant hypervigilance and symptom specific-anxiety in patients with chronic laryngeal symptoms, as well as substantial QOL impairment, and thus it is instrumental to better understand how adjunct therapies can be incorporated into clinical practice to target a patient more completely and holistically.10 Ultimately the goal is to develop and validate an algorithmic approach for evaluating patients with chronic laryngeal symptoms and create individualized therapies that target the whole patient and optimize outcomes. The time is ripe to consider retiring the term “laryngopharyngeal reflux” which is so broad and unable to fully capture the multitude of symptoms and disease pathologies that have classically been placed in this bucket. Rather, phenotype driven definitions should be adopted that help clarify both the patient’s symptoms and underlying disease pathology.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: NIH 5T32DK007202-46 (Ghosh, PI); NIH DK125266 (Yadlapati, PI); NIH DK135513 (Yadlapati)

Footnotes

Disclosures

AJK: No disclosures

RY: Consultant for Medtronic, Phathom Pharmaceuticals, StatLinkMD, Reckitt Benckiser Healthcare Ltd, Medscape; Research Support: Ironwood Pharmaceuticals; Advisory Board with Stock Options: RJS Mediagnostix

References

- 1.Lechien JR, Akst LM, Hamdan AL, et al. Evaluation and Management of Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Disease: State of the Art Review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. May 2019;160(5):762–782. doi: 10.1177/0194599819827488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R, Group GC. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. Aug 2006;101(8):1900–20; quiz 1943. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00630.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olson NR. Laryngopharyngeal manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. Oct 1991;24(5):1201–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruiz R, Jeswani S, Andrews K, et al. Hoarseness and laryngopharyngeal reflux: a survey of primary care physician practice patterns. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Mar 2014;140(3):192–6. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.6533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koufman JA, Amin MR, Panetti M. Prevalence of reflux in 113 consecutive patients with laryngeal and voice disorders. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Oct 2000;123(4):385–8. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2000.109935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lechien JR, Allen JE, Barillari MR, et al. Management of Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Around the World: An International Study. Laryngoscope. May 2021;131(5):E1589–E1597. doi: 10.1002/lary.29270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen SM, Pitman MJ, Noordzij JP, Courey M. Management of dysphonic patients by otolaryngologists. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Aug 2012;147(2):289–94. doi: 10.1177/0194599812440780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Bortoli N, Nacci A, Savarino E, et al. How many cases of laryngopharyngeal reflux suspected by laryngoscopy are gastroesophageal reflux disease-related? World J Gastroenterol. Aug 28 2012;18(32):4363–70. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i32.4363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Francis DO, Rymer JA, Slaughter JC, et al. High economic burden of caring for patients with suspected extraesophageal reflux. Am J Gastroenterol. Jun 2013;108(6):905–11. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu K, Krause A, Yadlapati R. Quality of Life and Laryngopharyngeal Reflux. Dig Dis Sci. Jul 06 2023;doi: 10.1007/s10620-023-08027-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salgado S, Borges LF, Cai JX, Lo WK, Carroll TL, Chan WW. Symptoms classically attributed to laryngopharyngeal reflux correlate poorly with pharyngeal reflux events on multichannel intraluminal impedance testing. Dis Esophagus. Dec 31 2022;36(1)doi: 10.1093/dote/doac041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen JW, Vela MF, Peterson KA, Carlson DA. AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Diagnosis and Management of Extraesophageal Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: Expert Review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Jun 2023;21(6):1414–1421.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.01.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Hara J, Stocken DD, Watson GC, et al. Use of proton pump inhibitors to treat persistent throat symptoms: multicentre, double blind, randomised, placebo controlled trial. BMJ. Jan 07 2021;372:m4903. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yadlapati R, Chan WW. Modern Day Approach to Extra-Esophageal Reflux: Clearing the Murky Lens. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Feb 28 2023;doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.12.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yadlapati R, Gyawali CP, Pandolfino JE, Participants CGCC. AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Personalized Approach to the Evaluation and Management of GERD: Expert Review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. May 2022;20(5):984–994.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.01.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katz PO, Dunbar KB, Schnoll-Sussman FH, Greer KB, Yadlapati R, Spechler SJ. ACG Clinical Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 01 January 2022;117(1):27–56. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gyawali CP, Carlson DA, Chen JW, Patel A, Wong RJ, Yadlapati RH. ACG Clinical Guidelines: Clinical Use of Esophageal Physiologic Testing. Am J Gastroenterol. September 2020;115(9):1412–1428. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krause AJ, Greytak M, Burger ZC, Taft T, Yadlapati R. Hypervigilance and Anxiety are Elevated Among Patients With Laryngeal Symptoms With and Without Laryngopharyngeal Reflux. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Oct 26 2022;doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.10.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gyawali CP, Yadlapati R, Fass R, et al. Updates to the modern diagnosis of GERD: Lyon consensus 2.0. Gut. 2023;doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2023-330616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Koufman JA. Validity and reliability of the reflux symptom index (RSI). J Voice. Jun 2002;16(2):274–7. doi: 10.1016/s0892-1997(02)00097-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lechien JR, Saussez S, Schindler A, et al. Clinical outcomes of laryngopharyngeal reflux treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Laryngoscope. May 2019;129(5):1174–1187. doi: 10.1002/lary.27591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lechien JR, Bobin F, Muls V, et al. Validity and reliability of the reflux symptom score. Laryngoscope. Mar 2020;130(3):E98–E107. doi: 10.1002/lary.28017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim YD, Shin CM, Jeong WJ, et al. Clinical Implications of the Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Questionnaire and Reflux Symptom Index in Patients With Suspected Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Symptoms. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. Oct 30 2022;28(4):599–607. doi: 10.5056/jnm21235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krause AJ, Greytak M, Kaizer A, Chan WW, Yadlapati R. Su1270 High Diagnostic Yield of Erosive Reflux Disease on Upper GI Endoscopy in the Evaluation of Laryngopharyngeal Reflux. Gastroenterology. 2023;164(6)doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(23)02325-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rusu R, Ishaq S, Wong T, Dunn JM. Cervical inlet patch: new insights into diagnosis and endoscopic therapy. Frontline Gastroenterol. Jul 2018;9(3):214–220. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2017-100855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grigolon A, Bravi I, Cantù P, Conte D, Penagini R. Wireless pH monitoring: better tolerability and lower impact on daily habits. Dig Liver Dis. Aug 2007;39(8):720–4. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wenner J, Johnsson F, Johansson J, Oberg S. Wireless esophageal pH monitoring is better tolerated than the catheter-based technique: results from a randomized cross-over trial. Am J Gastroenterol. Feb 2007;102(2):239–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00939.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zeki SS, Miah I, Visaggi P, et al. Extended Wireless pH Monitoring Significantly Increases Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Diagnoses in Patients With a Normal pH Impedance Study. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. Jul 30 2023;29(3):335–342. doi: 10.5056/jnm22130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roberts JR, Aravapalli A, Pohl D, Freeman J, Castell DO. Extraesophageal gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms are not more frequently associated with proximal esophageal reflux than typical GERD symptoms. Dis Esophagus. 2012;25(8):678–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2011.01305.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu K, Evans J, Clayton S. Proximal reflux frequency not correlated with atypical gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms. Dis Esophagus. Jul 03 2023;36(7)doi: 10.1093/dote/doac106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Francis DO, Goutte M, Slaughter JC, et al. Traditional reflux parameters and not impedance monitoring predict outcome after fundoplication in extraesophageal reflux. Laryngoscope. Sep 2011;121(9):1902–9. doi: 10.1002/lary.21897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zerbib F, Roman S, Bruley Des Varannes S, et al. Normal values of pharyngeal and esophageal 24-hour pH impedance in individuals on and off therapy and interobserver reproducibility. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Apr 2013;11(4):366–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.10.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vaezi MF, Schroeder PL, Richter JE. Reproducibility of proximal probe pH parameters in 24-hour ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring. Am J Gastroenterol. May 1997;92(5):825–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ayazi S, Hagen JA, Zehetner J, et al. Proximal esophageal pH monitoring: improved definition of normal values and determination of a composite pH score. J Am Coll Surg. Mar 2010;210(3):345–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoppo T, Sanz AF, Nason KS, et al. How much pharyngeal exposure is "normal"? Normative data for laryngopharyngeal reflux events using hypopharyngeal multichannel intraluminal impedance (HMII). J Gastrointest Surg. Jan 2012;16(1):16–24; discussion 24-5. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1741-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noordzij JP, Khidr A, Desper E, Meek RB, Reibel JF, Levine PA. Correlation of pH probe-measured laryngopharyngeal reflux with symptoms and signs of reflux laryngitis. Laryngoscope. Dec 2002;112(12):2192–5. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200212000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oelschlager BK, Quiroga E, Isch JA, Cuenca-Abente F. Gastroesophageal and pharyngeal reflux detection using impedance and 24-hour pH monitoring in asymptomatic subjects: defining the normal environment. J Gastrointest Surg. Jan 2006;10(1):54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sifrim D, Dupont L, Blondeau K, Zhang X, Tack J, Janssens J. Weakly acidic reflux in patients with chronic unexplained cough during 24 hour pressure, pH, and impedance monitoring. Gut. Apr 2005;54(4):449–54. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.055418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blondeau K, Dupont LJ, Mertens V, Tack J, Sifrim D. Improved diagnosis of gastro-oesophageal reflux in patients with unexplained chronic cough. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. Mar 15 2007;25(6):723–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03255.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sweis R, Fox M, Anggiansah A, Wong T. Prolonged, wireless pH-studies have a high diagnostic yield in patients with reflux symptoms and negative 24-h catheter-based pH-studies. Neurogastroenterol Motil. May 2011;23(5):419–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01663.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gyawali CP, Tutuian R, Zerbib F, et al. Value of pH Impedance Monitoring While on Twice-Daily Proton Pump Inhibitor Therapy to Identify Need for Escalation of Reflux Management. Gastroenterology. Nov 2021;161(5):1412–1422. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yadlapati R, Ciolino JD, Craft J, Roman S, Pandolfino JE. Trajectory assessment is useful when day-to-day esophageal acid exposure varies in prolonged wireless pH monitoring. Dis Esophagus. Mar 01 2019;32(3)doi: 10.1093/dote/doy077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hasak S, Yadlapati R, Altayar O, et al. Prolonged Wireless pH Monitoring in Patients With Persistent Reflux Symptoms Despite Proton Pump Inhibitor Therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Dec 2020;18(13):2912–2919. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.01.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yadlapati R, Gyawali CP, Masihi M, et al. Optimal Wireless Reflux Monitoring Metrics to Predict Discontinuation of Proton Pump Inhibitor Therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. Oct 01 2022;117(10):1573–1582. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yadlapati R, Masihi M, Gyawali CP, et al. Ambulatory Reflux Monitoring Guides Proton Pump Inhibitor Discontinuation in Patients With Gastroesophageal Reflux Symptoms: A Clinical Trial. Gastroenterology. Jan 2021;160(1):174–182.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.09.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnson LF, Demeester TR. Twenty-four-hour pH monitoring of the distal esophagus. A quantitative measure of gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Gastroenterol. Oct 1974;62(4):325–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnson LF, DeMeester TR. Development of the 24-hour intraesophageal pH monitoring composite scoring system. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1986;8 Suppl 1:52–8. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198606001-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kavitt RT, Higginbotham T, Slaughter JC, et al. Symptom reports are not reliable during ambulatory reflux monitoring. Am J Gastroenterol. Dec 2012;107(12):1826–32. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Slaughter JC, Goutte M, Rymer JA, et al. Caution about overinterpretation of symptom indexes in reflux monitoring for refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Oct 2011;9(10):868–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krause AJ, Greytak M, Kaizer AM, et al. Diagnostic Yield of Ambulatory Reflux Monitoring Systems for Evaluation of Chronic Laryngeal Symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. Oct 13 2023;doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yadlapati R, Pandolfino JE, Lidder AK, et al. Oropharyngeal pH Testing Does Not Predict Response to Proton Pump Inhibitor Therapy in Patients with Laryngeal Symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. Nov 2016;111(11):1517–1524. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wiener GJ, Tsukashima R, Kelly C, et al. Oropharyngeal pH monitoring for the detection of liquid and aerosolized supraesophageal gastric reflux. J Voice. Jul 2009;23(4):498–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2007.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Worrell SG, DeMeester SR, Greene CL, Oh DS, Hagen JA. Pharyngeal pH monitoring better predicts a successful outcome for extraesophageal reflux symptoms after antireflux surgery. Surg Endosc. Nov 2013;27(11):4113–8. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3076-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weitzendorfer M, Antoniou SA, Schredl P, et al. Pepsin and oropharyngeal pH monitoring to diagnose patients with laryngopharyngeal reflux. Laryngoscope. Jul 2020;130(7):1780–1786. doi: 10.1002/lary.28320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dulery C, Lechot A, Roman S, et al. A study with pharyngeal and esophageal 24-hour pH-impedance monitoring in patients with laryngopharyngeal symptoms refractory to proton pump inhibitors. Neurogastroenterol Motil. Jan 2017;29(1)doi: 10.1111/nmo.12909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mazzoleni G, Vailati C, Lisma DG, Testoni PA, Passaretti S. Correlation between oropharyngeal pH-monitoring and esophageal pH-impedance monitoring in patients with suspected GERD-related extra-esophageal symptoms. Neurogastroenterol Motil. Nov 2014;26(11):1557–64. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Agrawal N, Yadlapati R, Shabeeb N, et al. Relationship between extralaryngeal endoscopic findings, proton pump inhibitor (PPI) response, and pH measures in suspected laryngopharyngeal reflux. Dis Esophagus. Apr 01 2019;32(4)doi: 10.1093/dote/doy072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Powell J, Cocks HC. Mucosal changes in laryngopharyngeal reflux--prevalence, sensitivity, specificity and assessment. Laryngoscope. Apr 2013;123(4):985–91. doi: 10.1002/lary.23693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Milstein CF, Charbel S, Hicks DM, Abelson TI, Richter JE, Vaezi MF. Prevalence of laryngeal irritation signs associated with reflux in asymptomatic volunteers: impact of endoscopic technique (rigid vs. flexible laryngoscope). Laryngoscope. Dec 2005;115(12):2256–61. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000184325.44968.b1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ford CN. Evaluation and management of laryngopharyngeal reflux. JAMA. Sep 28 2005;294(12):1534–40. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.12.1534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vance D, Alnouri G, Shah P, et al. The Validity and Reliability of the Reflux Finding Score. J Voice. Jan 2023;37(1):92–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2020.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jahshan F, Ronen O, Qarawany J, et al. Inter-Rater Variability of Reflux Finding Score Amongst Otolaryngologists. J Voice. Sep 2022;36(5):685–689. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2020.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yadlapati R, Kaizer AM, Sikavi DR, et al. Distinct Clinical Physiologic Phenotypes of Patients With Laryngeal Symptoms Referred for Reflux Evaluation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. April 2022;20(4):776–786.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.05.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Patel DA, Sharda R, Choksi YA, et al. Model to Select On-Therapy vs Off-Therapy Tests for Patients With Refractory Esophageal or Extraesophageal Symptoms. Gastroenterology. Dec 2018;155(6):1729–1740.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Krause AJ, Kaizer A, Carlson D, et al. S456: COuGH RefluX: Externally Validated Risk Prediction Score for Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023;118(10S):S331–S332. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Patel V, Ma S, Yadlapati R. Salivary biomarkers and esophageal disorders. Dis Esophagus. Jul 12 2022;35(7)doi: 10.1093/dote/doac018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Knight J, Lively MO, Johnston N, Dettmar PW, Koufman JA. Sensitive pepsin immunoassay for detection of laryngopharyngeal reflux. Laryngoscope. Aug 2005;115(8):1473–8. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000172043.51871.d9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Potluri S, Friedenberg F, Parkman HP, et al. Comparison of a salivary/sputum pepsin assay with 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring for detection of gastric reflux into the proximal esophagus, oropharynx, and lung. Dig Dis Sci. Sep 2003;48(9):1813–7. doi: 10.1023/a:1025467600662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim TH, Lee KJ, Yeo M, Kim DK, Cho SW. Pepsin detection in the sputum/saliva for the diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease in patients with clinically suspected atypical gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms. Digestion. 2008;77(3-4):201–6. doi: 10.1159/000143795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang J, Li J, Nie Q, Zhang R. Are Multiple Tests Necessary for Salivary Pepsin Detection in the Diagnosis of Laryngopharyngeal Reflux? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Mar 2022;166(3):477–481. doi: 10.1177/01945998211026837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lechien JR, Bobin F, Muls V, et al. Saliva Pepsin Concentration of Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Patients Is Influenced by Meals Consumed Before the Samples. Laryngoscope. Feb 2021;131(2):350–359. doi: 10.1002/lary.28756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hayat JO, Gabieta-Somnez S, Yazaki E, et al. Pepsin in saliva for the diagnosis of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Gut. Mar 2015;64(3):373–80. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Woodland P, Singendonk MMJ, Ooi J, et al. Measurement of Salivary Pepsin to Detect Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Is Not Ready for Clinical Application. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Feb 2019;17(3):563–565. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Guo Z, Wu Y, Chen J, Zhang S, Zhang C. The Role of Salivary Pepsin in the Diagnosis of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) Evaluated Using High-Resolution Manometry and 24-Hour Multichannel Intraluminal Impedance-pH Monitoring. Med Sci Monit. Nov 21 2020;26:e927381. doi: 10.12659/MSM.927381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yadlapati R, Kaizer A, Greytak M, Ezekewe E, Simon V, Wani S. Diagnostic performance of salivary pepsin for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dis Esophagus. Apr 07 2021;34(4)doi: 10.1093/dote/doaa117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Du X, Wang F, Hu Z, et al. The diagnostic value of pepsin detection in saliva for gastro-esophageal reflux disease: a preliminary study from China. BMC Gastroenterol. Oct 17 2017;17(1):107. doi: 10.1186/s12876-017-0667-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Race C, Chowdry J, Russell JM, Corfe BM, Riley SA. Studies of salivary pepsin in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. May 2019;49(9):1173–1180. doi: 10.1111/apt.15138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ma SD, Patel VG, Greytak M, Rubin JE, Kaizer AM, Yadlapati RH. Diagnostic thresholds and optimal collection protocol of salivary pepsin for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dis Esophagus. Mar 30 2023;36(4)doi: 10.1093/dote/doac063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]