Abstract

CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) play a key role in the control of many virus infections, and the need for vaccines to elicit strong CD8+ T-cell responses in order to provide optimal protection in such infections is increasingly apparent. However, the mechanisms involved in the induction and maintenance of CD8+ CTL memory are currently poorly understood. In this study, we investigated the involvement of CD40 ligand (CD40L)-mediated interactions in these processes by analyzing the memory CTL response of CD40L-deficient mice following infection with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV). The maintenance of memory CD8+ CTL precursors (CTLp) at stable frequencies over time was not impaired in CD40L-deficient mice. By contrast, the initial generation of memory CTLp was affected. CD40L-deficient mice produced lower levels of CD8+ CTLp during the primary immune response to LCMV than did wild-type controls, despite the fact that the LCMV-specific effector CTL response of CD40L-deficient mice was indistinguishable from that of control animals. The differentiation of naïve CD8+ T cells into effector and memory CTL thus involves pathways that can be discriminated from each other by their requirement for CD40L-mediated interactions. Expression of CD40L by CTLp themselves was not an essential step during their expansion and differentiation from naïve CD8+ cells into memory CTLp; instead, the reduction in memory CTLp generation in CD40L-deficient mice was likely a consequence of defects in the CD4+ T-cell response mounted by these animals. These results thus suggest a previously unappreciated role for CD40L in the generation of CD8+ memory CTLp, the probable nature of which is discussed.

The CD40 ligand (CD40L) CD154 is a glycoprotein that is transiently expressed at high levels on the surface of CD4+ T cells when they are activated (2, 30, 39, 51, 53). This protein is also expressed (although at lower levels) on a subset of CD8+ T cells following activation (2, 28, 39, 53), and its expression has been documented on several other cell types, including mast cells, eosinophils, basophils, and B cells (reviewed in reference 66). CD40L is a member of the tumor necrosis factor family (2) and binds to CD40, a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor family (60). The latter is expressed on a variety of cell types with antigen-presenting cell function, including B cells, dendritic cells, activated macrophages, follicular dendritic cells, and endothelial cells (reviewed in reference 66). The fact that CD40L and CD40 are expressed in a tightly controlled fashion on T cells and on many different cell populations with which they interact suggests that CD40L-CD40 interactions are probably involved in the regulation of a number of aspects of the immune response. This is becoming increasingly apparent as research into the functions of this receptor-ligand pair progresses (17, 22, 23, 38, 50).

CD40L-CD40 interactions were originally shown to play a key role in thymus-dependent humoral immune responses, mediating cognate interactions between CD4+ T cells and B cells that are essential for B-cell activation and differentiation, class switching, germinal center formation, and the generation of B-cell memory (reviewed in references 21 and 31). More recently, roles for CD40L-CD40 interactions in the development of other immune effector functions have been described. For example, they have been shown to be of importance in the inflammatory immune response, regulating the induction of secretion of cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin-1, interleukin-12, and gamma interferon (IFN-γ), and of nitric oxide by monocytes and macrophages and prolonging the survival of these cells at sites of inflammation (reviewed in references 23 and 61). In addition, CD40L-CD40 interactions have been shown to be involved in the initiation of antigen-specific CD4+ T-cell responses (24, 25, 65, 71). A current model for the role of this system argues that CD40L is upregulated upon activation of CD4+ T cells following recognition of antigen presented by dendritic cells. CD40L then interacts with CD40 on the dendritic cell surface, leading to the induction of costimulatory activity mediated by both cell surface molecules and cytokines such as interleukin-12 by the dendritic cell (11, 35). This costimulatory activity is necessary for the CD4+ T cell to become fully activated and produce cytokines and/or perform other effector functions (reviewed in references 22 and 23). Further, CD40 is also expressed on thymic antigen-presenting cells (19), and it has been demonstrated that CD40-CD40L interactions play an essential role in negative selection in the thymus (18). Here too, they likely act by regulating costimulatory activity on antigen-presenting cells.

Despite the advances made recently in understanding the importance of CD40L-CD40 interactions in the activation and effector functions of mature CD4+ T cells, the functions of this receptor-ligand pair are by no means fully understood. CD40L is likely involved in other interactions between CD4+ T cells and the increasing number of different cell types on which CD40 expression is being documented; in addition, the role(s) that CD40L plays in the activation and/or effector functions of the subpopulation of CD8+ T cells that express it is not well defined. Human CD8+ T-cell clones expressing high levels of CD40L were shown to be able to stimulate B-cell growth and differentiation in vitro (29), but the level of CD40L expressed by CD8+ T cells is generally low, and the contribution made by CD8+ T cells to cognate B-cell help during in vivo immune responses is not likely to be very significant (54). The in vivo functions of CD40L expression on CD8+ T cells thus remain unclear.

To gain further insight into the potential roles of CD40L in the in vivo immune responses of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, we have been analyzing the immune response mounted by CD40L-deficient mice (70) after infection with different viruses. In a previous study (6), we found that although the effector CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) response mounted by CD40L-deficient mice on infection with arenaviruses such as lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) was unimpaired and virus clearance occurred with normal kinetics, the level of memory CTL activity detectable in the CD40L-deficient animals 2 months following infection was lower than that in wild-type mice. Here, we have investigated the basis of the defect in the memory CTL response of CD40L-deficient mice. It is shown that CD40L-deficient mice do not have an impaired ability to maintain memory CD8+ CTL precursors (CTLp) at stable frequencies over time but that the initial generation of CD8+ CTLp is impaired in these animals. Further, it is demonstrated that CD40L expression on CD8+ cells is not required for their proliferation and differentiation into memory CTLp. The reduction in memory CTLp generation in CD40L-deficient mice is instead likely a consequence of defects in the CD4+ T-cell response. These results suggest that CD40L plays a previously undefined role in the generation of memory CD8+ CTLp following virus infections, the nature of which is discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Homozygous CD40L-deficient mice (70) and wild-type controls were bred in parallel and used for experiments as young adults (8 to 14 weeks old). A randomly selected subset of CD40L-deficient mice was screened by PCR analysis of tail biopsy DNA to confirm the presence of homozygous mutations in their CD40L genes. C57BL/6 mice used as a source of peritoneal macrophages and feeder splenocytes for the in vitro restimulation of CTLp in limiting dilution assays were obtained either from the closed breeding colony of The Scripps Research Institute (La Jolla, Calif.) or from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine), as were the C57BL/6 Ly5a mice used for the creation of mixed bone marrow chimeras.

Generation of mixed bone marrow chimeras.

Bone marrow chimeras were prepared by a method based on that described by Gao et al. (20). Briefly, bone marrow was removed from CD40L-deficient (Ly5b) mice and wild-type C57BL/6 Ly5a mice and was depleted of T cells by treatment with a mixture of antibodies against Thy-1.2 (clone J1j), CD4 (clone RL172), and CD8 (clone 3.168) plus complement. Viable cells were enumerated and mixed 1:1. Recipient mice (wild-type C57BL/6 Ly5a mice which had been exposed to 1,000 rads of irradiation 4 to 6 h previously) were inoculated intravenously with 2 × 106 to 3 × 106 mixed cells/mouse. The mice were then kept for at least 8 weeks to allow time for reconstitution to occur before they were used in experiments.

Virus growth, titration, and use for infection of mice.

All experiments with LCMV involved the Armstrong 53b strain of the virus, a clone triple plaque purified from ARM CA 1371 (16). Stocks of this virus were prepared by growth on baby hamster kidney cells, and their titers were determined by plaque assay on Vero cells as previously described (16). Mice were infected with LCMV by intraperitoneal (i.p.) inoculation of 2 × 105 PFU of virus in a 200-μl volume.

Assay for LCMV-specific effector CTL activity during the primary immune response.

LCMV-specific effector CTL activity was quantitated by an in vitro 51Cr release assay as described by Byrne and Oldstone (9). The effector cells were erythrocyte-depleted splenocyte suspensions from mice infected 7 or 14 days previously with LCMV. Target cells were 51Cr-labelled fibroblast cell lines MC57 (H-2b, i.e., syngeneic to the CD40L-deficient mice) and Balb Cl 7 (H-2d i.e., allogeneic to the CD40L-deficient mice) which were either uninfected or infected 48 h prior to 51Cr labelling with LCMV at a multiplicity of infection of 3 PFU per cell. Target cells were plated at 104 per well, and effector cells were added to give effector/target (E/T) ratios between 100:1 and 0.5:1. All variables were tested in triplicate. The assay time was 5 h. Results are expressed as the percentage of specific 51Cr release, calculated as 100 × (experimental release − spontaneous release)/(maximum release − spontaneous release).

Limiting dilution assay for quantitation of LCMV-specific CTLp frequencies.

The assay method used was based on that described by Nahill and Welsh (48). Briefly, thioglycolate-elicited peritoneal macrophages from C57BL/6 mice were infected with LCMV at a multiplicity of infection of 0.1 PFU/cell and plated at 7 × 104/well into 96-well flat-bottomed plates (Costar Corporation, Cambridge, Mass.) in a volume of 100 μl of RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 7% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 1 mM glutamine, 50 U of penicillin/ml, and 50 μg of streptomycin/ml (termed RPMI 7%). After 2 days of culturing, the plates were irradiated (2,000 rads), and half of the medium was removed from each well and replaced with 50 μl of restimulation medium containing 105 irradiated (2,000 rads) syngeneic erythrocyte-depleted splenocytes. The restimulation medium consisted of RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 5% concanavalin A (ConA)-stimulated rat spleen supernatant, 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 2 mM glutamine, 50 μg of gentamicin/ml, and 50 μg of streptomycin/ml. Test cell populations (either erythrocyte-depleted splenocytes or sorted CD8+ T cells from mice previously infected for different lengths of time with LCMV) were diluted in restimulation medium so that they could be added to these plates at various numbers of cells per well in 100-μl volumes. Twenty-four replicate wells were set up at each input test cell number. The plates were incubated at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere for 7 days. On day 4 of culture, 100 μl of medium was removed from each well and replaced with 100 μl of fresh restimulation medium. On day 7 of culture, cells from individual wells were split twofold and assayed for cytotoxic activity on LCMV-infected and uninfected syngeneic target cells (MC57) by a 51Cr release assay. 51Cr-labelled target cells were added to all wells at 104/well to give a final total volume of 200 μl/well, and 51Cr release into the supernatant was quantitated after a 5-h incubation period. Positive wells were defined as those whose specific 51Cr release (calculated as described above) was greater than 10%. CTLp frequencies were estimated from the fraction of nonresponding wells at each input cell number per well by single-hit model Poisson distribution analysis (14).

Induction of anti-H-Y immune responses and assay for H-Y-specific memory CTL activity.

To induce immune responses to the male antigen H-Y, female mice were inoculated i.p. with 2 × 106 erythrocyte-depleted splenocytes from syngeneic wild-type male mice in a 200-μl volume of phosphate-buffered saline. H-Y-specific memory CTL activity was assayed 4 to 6 weeks later by a method based on that described by Di Rosa and Matzinger (15), except that cytotoxic activity was measured in 51Cr release assays. Briefly, erythrocyte-depleted splenocyte suspensions from individual test mice were restimulated in vitro by culture in 24-well plates at 5 × 106 cells/well together with 2 × 106 irradiated (2,000 rads) erythrocyte-depleted splenocytes from syngeneic wild-type male mice/well in a final volume of 2 ml/well of restimulation medium. After 3 days of culture, 1 ml of medium was removed from each well and replaced with 1 ml of fresh restimulation medium. Cells were harvested after 6 days of culture, and the cytotoxic activity mediated by bulk effector populations from individual animals was measured in a 51Cr release assay with syngeneic male and female ConA-activated blasts as target cells. The latter were prepared by culturing erythrocyte-depleted splenocytes from male and female mice for 3 days in 24-well plates at 2 × 106/well in a 2-ml volume/well of RPMI 7% medium containing ConA at a final concentration of 2 μg/ml. After 51Cr labelling, the target cells were plated into 96-well plates at 104/well, and effector cells were added to give E/T ratios between 60:1 and 7.5:1. All variables were assayed in triplicate. 51Cr release into the supernatant was measured after 5 h. Results are expressed as the percentage of specific 51Cr release, calculated as described above.

BrdU incorporation studies for the analysis of lymphocyte turnover.

The turnover of different T-cell populations stimulated by inoculation of mice with polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid [poly(IC)] or infection with LCMV was assessed by administering a DNA precursor, bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) in the drinking water and then examining the surface markers on BrdU-labelled cells, as previously described (64). Mice were inoculated i.p. with 150 μg of poly(IC) (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) in 150 μl of phosphate-buffered saline or infected with LCMV and were given sterile drinking water containing BrdU (Sigma Chemical Co.) at 0.8 mg/ml, which was made fresh and changed daily. At different time points thereafter, mice were sacrificed and spleen and lymph node cell suspensions were prepared, stained in multiple colors with antibodies directed against different lymphocyte markers and BrdU, and examined by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis as described below.

FACS analysis and sorting of lymphocyte subpopulations.

Staining of cell surface antigens for FACS analysis was performed by conventional techniques (13). Primary antibodies used in different experiments were fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-CD8 (clone 53-6.7; GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.), Cy-5-conjugated anti-CD8 (clone 53-6.7), Cy-5-conjugated anti-CD4 (clone GK1.5), biotinylated anti-CD44 (clone IM7.8.1), phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-CD40L (clone MR1; Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.), biotinylated anti-Ly5a (clone A20), and biotinylated anti-Ly5b (clone 104). Biotinylated primary antibodies were detected with PE-streptavidin or RED670-streptavidin (both from GIBCO BRL). In experiments that involved costaining for BrdU, surface staining was performed first and then the cells were washed, fixed, permeabilized, DNase treated, washed again, and incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-BrdU antibody as previously described (64). Two- and three-color staining were analyzed with a FACScan flow cytometer, four-color staining was analyzed with a FACSCaliber flow cytometer, and cell sorting was performed with a FACSVantage flow cytometer (all from Becton Dickinson & Co., Mountain View, Calif.).

RESULTS

Impairment of the virus-specific memory CD8+ CTL response in CD40L-deficient mice.

To clarify the roles that CD40L-dependent signalling events play in the induction and regulation of antiviral immune responses in vivo, we have been examining the nature of the immune response mounted by CD40L-deficient mice following infection with different viruses. In a previous study (6), we demonstrated that CD40L-deficient mice infected with arenaviruses such as LCMV mount effector CD8+ CTL responses that are indistinguishable from those of wild-type control animals and clear the infection with normal kinetics. However, preliminary analysis of the memory CTL activity exhibited by bulk splenocytes 2 months following LCMV infection indicated that this function was impaired in CD40L-deficient mice.

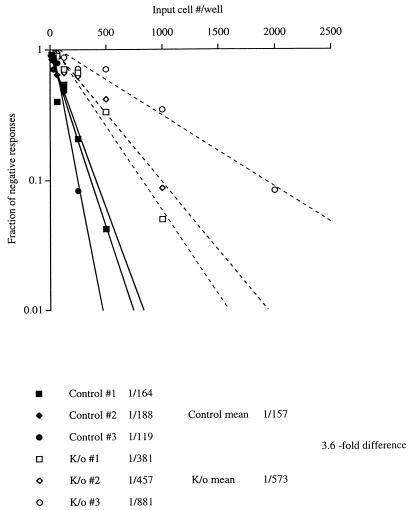

To assess the defect in memory CD8+ CTL activity in CD40L-deficient mice more quantitatively, limiting dilution analysis of the virus-specific CTLp frequencies in splenocyte populations from CD40L-deficient and wild-type control mice infected 16 weeks previously with LCMV was performed. As shown in Fig. 1, this analysis revealed the LCMV-specific CTLp frequency in the CD40L-deficient mice to be approximately fourfold lower than that in the control animals at this time point. The difference in memory CD8+ CTLp levels in CD40L-deficient and wild-type mice 16 weeks following infection with LCMV could potentially be due to deficits in the generation and/or the maintenance of virus-specific CTLp in the CD40L-deficient mice. Further experiments were carried out to investigate which factors were involved.

FIG. 1.

LCMV-specific CTLp frequencies in the spleens of CD40L-deficient and wild-type control mice 16 weeks following virus infection. LCMV-specific CTLp frequencies in splenocyte suspensions from individual CD40L-deficient (open symbols) and wild-type mice (closed symbols) infected 16 weeks previously with 2 × 105 PFU of LCMV i.p. were quantitated by limiting dilution assay as described in Materials and Methods. The precursor frequencies estimated for each control (control no. 1 to 3) and CD40L-deficient (knockout [K/o] no. 1 to 3) mouse, the mean frequency of each group of animals (control mean and K/o mean), and the fold difference in mean CTLp frequencies between the two groups are shown.

Analysis of the maintenance of CD8+ CTL memory in CD40L-deficient mice.

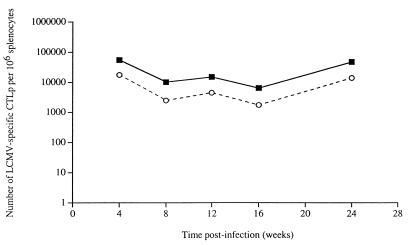

In normal mice, virus-specific CTLp levels are maintained at a fairly constant level after an acute virus infection for the life of the animal (32, 40). To determine whether CD40L-deficient mice had an impaired ability to maintain memory CTL, groups of CD40L-deficient and control mice were infected with LCMV and the frequency of virus-specific CTLp in sets of three mice from each group was measured by limiting dilution assay over time after the acute phase of the infection. Figure 2 illustrates the mean number of LCMV-specific CTLp per 106 splenocytes in the animals tested from each group at time points from 1 to 6 months postinfection. As expected, the LCMV-specific CTLp frequency in the control mice remained very stable over the 6-month observation period. Importantly, the virus-specific CTLp frequency in the CD40L-deficient mice did not decline relative to that in the control animals with time postinfection but was consistently found to be approximately fourfold lower than the mean frequency of the wild-type mice at all time points tested. This result shows that CD40L-dependent signalling is not required for the maintenance of memory CTLp at stable frequencies over time.

FIG. 2.

Maintenance of LCMV-specific CTLp at stable frequencies over time in CD40L-deficient and wild-type control animals. Groups of CD40L-deficient and wild-type control mice were infected i.p. with 2 × 105 PFU of LCMV on day 0. At the indicated times postinfection, three mice from each group were sacrificed, and the frequency of LCMV-specific CTLp in the spleen of each animal was quantitated by limiting dilution assay as described in Materials and Methods. The results shown are the mean number of CTLp per 106 splenocytes of the control (closed squares) and CD40L-deficient (open circles) animals tested at each time point.

How CTL memory is maintained is currently a subject of some debate. Virus-specific CTLp frequencies can clearly be maintained at stable levels for the entire life span of a mouse in the absence of specific antigen (32, 40). One theory as to how this is achieved (63), based on the observation that CD44hi (memory phenotype) CD8+ T cells are stimulated to divide in an antigen nonspecific fashion by cytokines such as type 1 IFN, suggests that the cytokine production which accompanies the virus infections that an animal intermittently contracts throughout its life drives the division of memory CTLp at intervals and thus maintains them at a constant level over time. We thus compared the turnover of CD44hi CD8+ T cells stimulated by inoculation of poly(IC) (a synthetic inducer of type 1 IFN) in CD40L-deficient and wild-type control mice. A high level of turnover of CD44hi CD8+ T cells was stimulated by poly(IC) in both CD40L-deficient and wild-type mice (data not shown). This result is in keeping with the data in Fig. 2 showing that virus-specific CTLp frequencies are stably maintained over time in CD40L-deficient mice.

Analysis of the generation of LCMV-specific CTLp in CD40L-deficient mice.

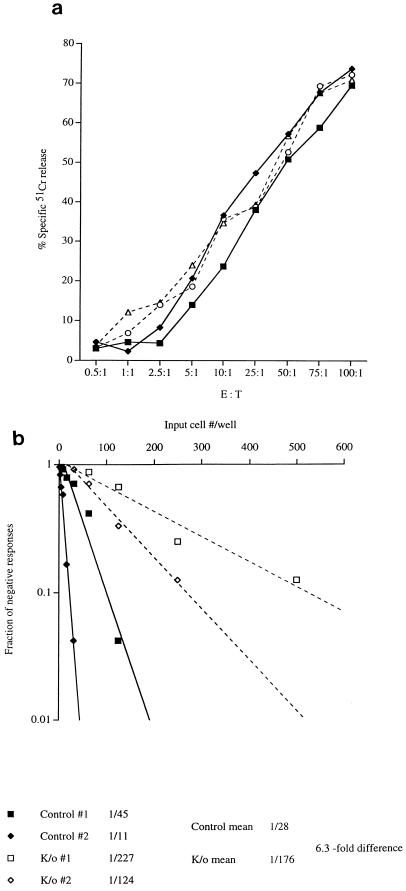

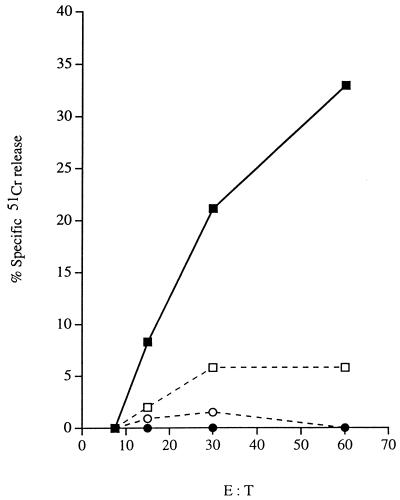

To compare the generation of virus-specific CTLp during the acute phase of LCMV infection in CD40L-deficient and wild-type mice, groups of mice of each type were infected with LCMV and limiting dilution analysis of the LCMV-specific CTLp frequencies in two or three individual animals from each group was performed 7 and 14 days later. The direct effector CTL activity mediated by each test population was also measured. Figure 3 shows the results obtained at 7 days postinfection with two CD40L-deficient and two control mice; a second experiment in which three mice per group were tested confirmed these. Although the direct effector CTL activity exhibited by CD40L-deficient and control mice was indistinguishable (Fig. 3a), the LCMV-specific CTLp frequencies in the CD40L-deficient mice were clearly lower than those in the control animals at this time point (Fig. 3b). Very similar results (data not shown) were also obtained at day 14, although by this time postinfection the levels of direct CTL lysis were not as high and the CTLp frequencies were slightly lower. The processes by which effector and memory CTL are generated during an acute virus infection can thus be differentiated by their dependence on CD40L-mediated signalling. CD8+ effector CTL can be generated efficiently in the absence of CD40L; by contrast, although there is not an absolute requirement for CD40L in the production of CD8+ memory CTLp, CD40L-dependent signalling is clearly involved in a pathway(s) which influences the overall efficiency with which memory CTLp are generated.

FIG. 3.

LCMV-specific effector CTL activity and CTLp frequencies in splenocyte populations from CD40L-deficient and wild-type mice infected 7 days previously with LCMV. CD40L-deficient and wild-type mice were infected i.p. with 2 × 105 PFU of LCMV. Seven days later, two mice from each group were sacrificed, and splenocyte suspensions from individual CD40L-deficient animals (open symbols and dashed lines) and wild-type controls (closed symbols and solid lines) were assayed for both ex vivo effector CTL activity (a) and CTLp frequency (b). (a) Percentage of specific 51Cr release (calculated as described in Materials and Methods) mediated by each splenocyte population from syngeneic LCMV-infected target cells over a range of different E/T ratios. Even at the highest E/T ratios, the specific 51Cr release from control target cells (uninfected syngeneic targets and LCMV-infected allogeneic targets) tested in the same assay never exceeded 20% (data not shown), indicating that the ex vivo cytotoxic activity observed was both virus specific and major histocompatibility complex restricted. (b) Results of a limiting dilution assay used to quantitate the LCMV-specific CTLp frequency in each splenocyte population. The precursor frequencies estimated for each control mouse (control no. 1 and 2) and CD40L-deficient mouse (knockout [K/o] no. 1 and 2), the mean frequency of each group of animals (control mean and K/o mean), and the fold difference in mean CTLp frequencies between the two groups (fold difference) are indicated. The results shown are representative of those obtained in two separate experiments in which a total of five CD40L-deficient and five wild-type mice were tested.

Investigation of the role of expression of CD40L on CD8+ versus CD4+ T cells in the generation of virus-specific CD8+ CTLp.

A number of reports have shown that CD40L is transiently expressed on the surface not only of activated CD4+ T lymphocytes but also of a subpopulation of CD8+ T lymphocytes following activation (2, 28, 39). It has been demonstrated that human CD8+ T-cell clones which express high levels of CD40L upon activation have the capacity to stimulate B-cell activation, growth, and differentiation (29), but whether CD40L- mediated signalling is involved in other aspects of CD8+ T-cell biology has not been fully investigated. The process by which memory CD8+ CTLp are generated during an immune response is poorly understood; transient CD8+ expression of CD40L could hypothetically be involved. As a first step toward investigating whether CD40L expression on CD8+ T cells may be involved in the generation of CD8+ CTLp, we assessed the expression of CD40L on CD8+ (and also CD4+) T cells from the spleens and lymph nodes of mice at different times after infection with LCMV by FACS analysis following two-color staining with antibodies against CD40L and CD4/8. The extent and kinetics of CD40L expression on T cells in the spleen and lymph node differed. CD40L expression was induced on a much higher proportion of T cells in the spleen, where the percentage of CD40L-positive CD4+ cells peaked at >10% on day 7 postinfection. On CD8+ T cells, CD40L expression was undetectable in the lymph node, but a low percentage of positive cells were observed in the spleen between days 3 and 14 postinfection. It was thus clear that CD40L expression was much more prominent on CD4+ cells than on CD8+ cells after LCMV infection. However, the sensitivity of the staining method used in this experiment would not have allowed the detection of low levels of CD40L expression; further, as CD40L is expressed only transiently by lymphocytes following activation, this experiment did not reveal what proportion of cells in fact expressed CD40L at some point during the course of the infection. The possibility that low-level CD40L expression on CD8+ cells played a role in the generation of CD8+ CTLp thus could not be ruled out.

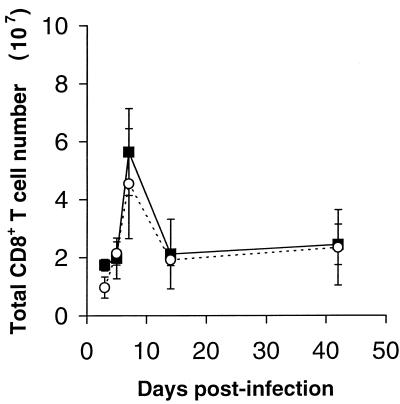

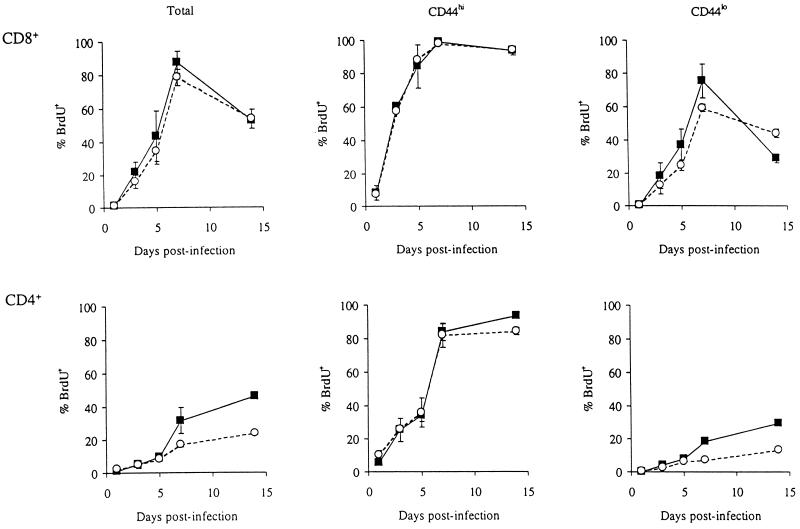

In a further experiment, the activation and proliferation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells over the course of LCMV infection in CD40L-deficient and wild-type mice were compared. Groups of CD40L-deficient and wild-type control animals were infected with LCMV and immediately given drinking water containing BrdU to label dividing lymphocytes. At different times following infection, two mice from each group were sacrificed, and the expression of CD4/8, CD44, and BrdU by spleen and lymph node cells was determined by three-color FACS analysis. Similar numbers of total CD8+ cells were found in CD40L-deficient and control mice at all time points (Fig. 4). Figure 5 illustrates for both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells the mean percentage of BrdU-positive total, CD44hi, and CD44lo cells in the spleens of the mice from each group tested at each time point. There was essentially no difference in the proliferation of CD8+ T cells in the CD40L-deficient mice compared to that in the wild-type mice. CD44lo (naïve phenotype) CD8+ T cells were activated and began to divide by day 3 postinfection. On day 7, more than 50% of the CD44lo CD8+ T cells in the spleens of both CD40L-deficient and control mice were BrdU positive, and the percentage of CD44hi CD8+ T cells had increased dramatically (from 13% of splenocytes on day 1 postinfection to 54% on day 7 in the wild-type mice and from 15% of splenocytes on day 1 postinfection to 50% on day 7 in the CD40L-deficient animals). By this time point, almost all of the memory phenotype (CD44hi) CD8+ T cells in the spleens (and lymph nodes; data not shown) of both groups of mice had also divided. This result is in keeping with the finding that CD44hi CD8+ T-cell turnover in response to poly(IC) was not impaired in CD40L-deficient mice.

FIG. 4.

Changes in the total number of CD8+ T cells in the spleens and lymph nodes of wild-type and CD40L-deficient mice following infection with LCMV. Wild-type and CD40L-deficient mice were infected i.p. with 2 × 105 PFU of LCMV. At the indicated times (days) postinfection, two mice from each group were sacrificed, and the total number of CD8+ T cells in the spleen and lymph nodes of each animal was determined. The results shown are the mean total CD8+ T-cell counts of the wild-type (closed squares and solid lines) and CD40L-deficient (open circles and dashed lines) mice. Vertical bars indicate 1 standard deviation above and below the mean value for each group of animals.

FIG. 5.

Division of total, CD44hi and CD44lo CD8+ and CD4+ splenic T cells over time following infection of wild-type and CD40L-deficient mice with LCMV. Groups of wild-type and CD40L-deficient mice were infected i.p. with 2 × 105 PFU of LCMV and immediately given drinking water containing BrdU to label dividing lymphocytes. At the indicated times (days) postinfection, two mice from each group were sacrificed, and the expression of CD4/8, CD44, and BrdU by spleen cells was determined by FACS analysis. Shown (for total, CD44hi, and CD44lo T cells of the CD8+ and CD4+ subsets, as indicated) are the mean percentages of BrdU-positive cells (percentage BrdU+) in the wild-type (closed squares and solid lines) and CD40L-deficient (open circles and dashed lines) mice tested at each time point. The vertical bars indicate 1 standard deviation above and below the mean value for each group of animals. Standard deviations smaller than the size of the symbols are not apparent.

Figure 5 also illustrates that the early activation and turnover of CD44hi CD4+ T cells were likewise not seriously impaired in the CD40L-deficient mice; more than 80% of the CD44hi CD4+ T cells in the spleens of both CD40L-deficient and wild-type mice were BrdU positive by day 7 postinfection. However, the BrdU labelling of naïve phenotype CD4+ T cells in the CD40L-deficient mice was substantially reduced compared to that in the wild-type control animals. Whereas an average of 18% of the CD44lo CD4+ T cells in the spleens of the wild-type mice had incorporated BrdU by day 7 postinfection, only 7% had done so in the CD40L-deficient animals. This could potentially have been due to differences in the rate of thymic output of CD4+ T cells in CD40L-deficient compared to wild-type mice or could reflect an impairment in the activation and proliferation of naïve CD4+ T cells in LCMV-infected CD40L-deficient mice. The fact that the activation and proliferation of naïve CD4+ T cells in response to LCMV infection may have been impaired while that of naïve CD8+ T cells clearly was not provided further suggestive evidence that a defect in CD4+ rather than CD8+ functioning may underlie the observed defect in the generation of CD8+ memory CTLp in CD40L-deficient mice.

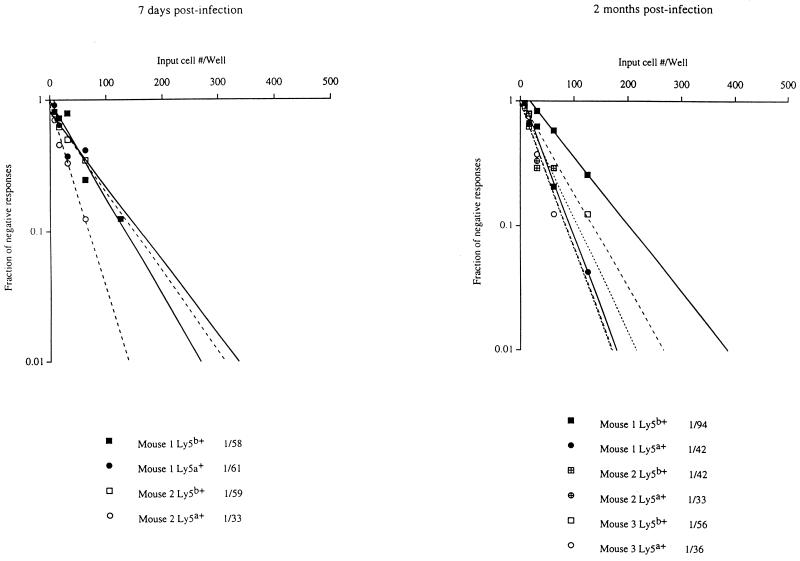

To more conclusively determine the role of CD40L expression on CD8+ T cells themselves in the generation of memory CTLp, an experiment was designed in which the generation of LCMV-specific memory CTLp from CD8+ T cells derived from CD40L-deficient and wild-type mice could be directly compared in the same CD4+ T-cell environment. Mixed bone marrow chimeras were created by reconstituting irradiated wild-type Ly5a H-2b-mice with a mixture of bone marrow derived from CD40L-deficient Ly5b H-2b and wild-type Ly5a H-2b mice. In the reconstituted mice, 75 to 80% of peripheral T cells were Ly5a+ (i.e., able to express normal levels of CD40L). These chimeras were infected with LCMV, and at 7 days and 2 months postinfection, the frequency of LCMV-specific CTLp in sorted populations of Ly5a+ and Ly5b+ CD8+ T cells from individual chimeric mice was determined by limiting dilution analysis. As the results in Fig. 6 show, the LCMV-specific CTLp frequencies in the Ly5a+ and Ly5b+ CD8+ T-cell populations derived from each mouse were not appreciably different. This experiment thus demonstrates that memory CD8+ CTLp can be generated just as efficiently from CD8+ T cells which are unable to express CD40L as from CD8+ T cells derived from wild-type mice and suggests that the efficiency of generation of memory CD8+ CTLp is indirectly influenced by events triggered by CD40L-mediated signalling between CD4+ T lymphocytes and other cells.

FIG. 6.

Experiment comparing the generation of LCMV-specific memory CTLp from CD8+ T cells derived from CD40L-deficient and wild-type mice in the same CD4+ T-cell environment. Mixed bone marrow chimeras were created by reconstituting irradiated wild-type Ly5a H-2b mice with a mixture of bone marrow derived from CD40L-deficient Ly5b H-2b and wild-type Ly5a H-2b mice. These chimeras were infected i.p. with 2 × 105 PFU of LCMV, and at 7 days and 2 months postinfection, the frequency of LCMV-specific CTLp in sorted populations of Ly5a+ (circles) and Ly5b+ (squares) CD8+ T cells from individual chimeric mice was determined by limiting dilution assay as described in Materials and Methods. The precursor frequencies estimated for the Ly5a+ and Ly5b+ CD8+ T cells from each mouse tested are indicated.

Investigation of the memory CD8+ CTL response to H-Y in CD40L-deficient mice.

Whereas the primary LCMV-specific CD8+ CTL response is known to be CD4+ T-cell independent (41, 45, 52), in other systems CD8+ CTL are much more dependent on help from CD4+ T cells. A classic example of this is the CD8+ CTL response to the male antigen H-Y (26, 58, 67). We reasoned that if, as suggested by the above-mentioned experiments in the LCMV system, the defect in generation of CD8+ CTLp in CD40L-deficient mice was due to the fact that CD4+ T cells influence the generation of CD8+ CTLp via pathway(s) that involve CD40L-mediated signalling, then the defect in generation of memory CD8+ CTLp in CD40L-deficient mice may be even more apparent in the H-Y system. We thus compared the H-Y-specific memory CTL response in CD40L-deficient and wild-type female mice immunized 4 to 6 weeks previously with splenocytes from syngeneic wild-type male mice. As the in vitro expansion of H-Y-specific CD8+ CTLp is known to be dependent on cytokines produced by CD4+ T cells (15), test splenocyte populations were restimulated in vitro in the presence of cytokine-containing supernatants so that differences observed in their lytic activities would reflect true differences in the input CD8+ CTLp content rather than defective expansion of these cells in vitro. Figure 7 shows that although H-Y-specific memory CTL responses were readily detected in bulk CTL assays with effector cells from wild-type mice, they could not be detected in CD40L-deficient animals. Similarly, when limiting dilution assays were carried out, the frequency of H-Y-specific CTLp in CD40L-deficient mice was found to be below the limit of detection of the assay (<1 per 500,000 splenocytes). These results lend further support to the hypothesis that CD4+ T cells play a role in the generation of CD8+ memory CTLp.

FIG. 7.

H-Y-specific memory CTL activity in CD40L-deficient and wild-type mice. Female CD40L-deficient and wild-type mice were immunized i.p. with splenocytes from syngeneic wild-type male mice. Four weeks later, two to three mice from each group were sacrificed, and the H-Y-specific memory CTL activity mediated by in vitro-restimulated splenocyte populations from individual animals was determined as described in Materials and Methods. The results shown are the mean percentage of specific 51Cr release (calculated as described in Materials and Methods) mediated by the wild-type (closed symbols and solid lines) and CD40L-deficient (open symbols and dashed lines) mice from syngeneic male target cells (squares) and, as a control, syngeneic female target cells (circles) over a range of different E/T ratios as indicated. The results are representative of data obtained in two independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

CD8+ CTL play a key role in control of many virus infections, and the need for vaccines to elicit strong CD8+ T-cell responses in order to provide optimal protection in such infections is increasingly apparent. However, the mechanisms involved in the induction and maintenance of CD8+ CTL memory are currently poorly understood. In this study, we have investigated the involvement of CD40L-mediated interactions in these processes by analyzing the basis of a defect we had previously observed (6) in the memory CTL response of CD40L-deficient mice. We show firstly that the maintenance of memory CD8+ CTLp at stable frequencies over time is not dependent on CD40L-mediated interactions, as this is not impaired in CD40L-deficient mice. By contrast, we demonstrate that CD40L-mediated interactions do impact upon the generation of memory CD8+ CTLp, as these cells are produced at lower frequencies during the primary immune response in CD40L-deficient mice than in wild-type animals. Further, we show that expression of CD40L by CTLp themselves is not an essential step during their expansion and differentiation from naïve CD8+ cells into memory CTLp. The reduction in memory CTLp generation in CD40L-deficient mice is more likely a consequence of defects in the CD4+ T-cell response mounted by these animals.

How CD8+ CTL memory is maintained, and in particular the question of whether persistent contact with antigen is required, is a subject of intensive debate (1, 37, 59). Persistent contact with specific antigen appears to be required to maintain memory T cells in a state of chronic activation which, it has been argued, may be necessary if they are to provide protective immunity against certain forms of viral challenge (3, 36, 37). However, several studies have convincingly demonstrated that memory CD8+ T cells are able to survive at constant levels over time in the complete absence of the antigen to which they were elicited (32, 40, 47). Two theories as to how their survival may be maintained propose the involvement of stimulation with cross-reactive environmental antigens (5, 56) or stimulation by cytokines (such as type 1 IFNs) elicited during immune responses to unrelated agents (63). Our data demonstrate that whatever the mechanism involved, CD40L-mediated interactions do not play an essential role. This observation could be accommodated by either of the two theories above. In the latter case, it would imply that production of the cytokines which stimulate bystander turnover of the memory CD8+ T cells is not significantly impaired in the absence of CD40L-mediated interactions; this would not be surprising in the case of innate cytokines such as type 1 IFNs. Alternatively, if the former mechanism is involved, CD40L-mediated signalling must not be required for the memory CTLp to be efficiently stimulated by the cross-reactive antigens. This is in contrast to the stimulation of the generation of memory CTLp during the initial immune response to specific antigen, which we have shown does require CD40L-mediated signalling.

The process by which memory CD8+ CTLp are initially generated is just as unclear as the mechanism by which CTL memory is subsequently maintained. Demonstrating a role for CD40L-mediated interactions in this process, we went on to investigate whether expression of CD40L on CD8+ CTLp themselves was involved. CD40L is transiently expressed not only on CD4+ T cells but also on a subpopulation of CD8+ T cells following activation (2, 28, 39); it was possible that signalling mediated via this molecule may play a role in the differentiation of this subset of CD8+ cells into memory CTLp. However, this did not prove to be the case; instead, the reduction in memory CTLp generation in CD40L-deficient mice appeared to be a consequence of defects in the CD4+ T-cell response mounted in the absence of CD40L-mediated interactions.

The requirement for (and nature of) CD4+ T-cell help for CD8+ CTL responses is also not well understood. Whether CD4+ T cells are required for primary CTL responses to be elicited is dependent on the system studied. Thus, virus-specific CD8+ CTL responses are efficiently induced in the absence of CD4+ T cells following infection of mice with many (8, 41, 42, 45, 49) but not all viruses (69), and the ability to prime mice with CD8 epitopic sequences in the absence of CD4 epitopes is dependent on the immunization protocol followed (55). Further, although effector CTL responses clearly can be elicited to many viruses without the help of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T-cell responses do not seem to be sustained during persistent virus infections in the absence of CD4+ T cells (10, 62). In both viral and nonviral systems, CD8+ T cells are more readily deleted after a transient response to antigen if CD4+ help is not available (4, 34, 44). The role of CD4+ T-cell help in the generation and/or maintenance of long-term immunological memory in the CD8+ compartment is a controversial area. Two previous studies of the LCMV system found that memory CTL responses were impaired in major histocompatibility complex class II-deficient and CD4-deficient mice (12, 68). The first did not determine whether the generation and/or the maintenance of immune memory was affected, while the second suggested that memory CD8+ CTLp were generated at normal levels in the absence of CD4+ T cells but subsequently declined in frequency over time. However, the latter result is at odds with the conclusion drawn from a less quantitative study which suggested that LCMV-specific memory CTL activity persisted over time in CD4-deficient mice (4) and with findings in the H-Y system that once memory CD8+ CTL are formed, their long-term survival does not require help from CD4+ T cells (7, 15). Our data showing that the generation but not the maintenance of LCMV-specific CD8+ CTLp is impaired in CD40L-deficient mice in which the CD4+ T-cell response is defective support the view that the maintenance of CD8+ memory CTLp at stable frequencies over time does not require help from CD4+ T cells mediated via CD40L. Further, our results suggest a previously unappreciated role for CD4+ T cells in the initial generation of CD8+ memory CTLp.

There are several mechanisms by which CD4+ T cells could potentially influence the generation of memory CD8+ CTLp. Firstly, they may mediate antiviral effects (e.g., via production of cytokines such as IFN-γ) which affect the antigen load to which CD8+ T cells are exposed during the early stages of the infection. Exposure of CD8+ T cells to very high levels of viral antigen in the early stages of LCMV infection has been shown to result in complete exhaustion of the CD8+ CTL response (46); it could thus be envisaged that if in the absence of optimal CD4+ T-cell functioning there was a moderate increase in the viral load, the level of generation of CD8+ CTLp may be reduced somewhat. However, two lines of evidence argue against this being the mechanism underlying the CD4+ T-cell dictated reduction in CD8+ CTLp generation we observed in CD40L-deficient mice. Firstly, the titers of infectious virus and kinetics of virus clearance in CD40L-deficient mice did not differ appreciably from those in wild-type animals infected with the same dose of LCMV (6). Secondly, the phenomenon of CTL exhaustion is manifest at the level of effector CTL activity in addition to CTLp generation, but as shown in Fig. 3, the deficit in virus-specific CTLp generation in CD40L-deficient mice occurred independently of any deficit in primary effector CTL activity.

An alternative, more direct mechanism by which CD4+ T cells may influence the generation of virus-specific CD8+ memory CTLp is via production of cytokines which stimulate T-cell proliferation and/or affect T-cell survival. The importance of cytokines in determining the fate of CD8+ T cells after antigenic stimulation has been illustrated in the H-Y system, in which IL-2 was shown to considerably delay the deletion of specific CD8+ T cells activated by antigenic stimulation in the absence of CD4+ T-cell help (34). CD4+ T cells are the major producers of IL-2 during LCMV infection of mice (33). In CD40L-deficient mice, in which CD4+ T-cell activation is impaired (24, 25), the amount of this and/or of other cytokines available to CD8+ T cells may thus be limiting. It is notable that although memory CTLp were generated at reduced frequencies in CD40L-deficient mice, the proliferation of CD8+ T cells was not affected (Fig. 5). Thus, if a deficit in cytokine production by CD4+ T cells does underlie the defect in memory CD8+ CTLp generation in CD40L-deficient mice, the cytokine(s) involved must impact on differentiation decisions made by CD8+ T cells rather than just controlling their overall extent of activation and proliferation.

A third potential mechanism by which CD4+ T cells may affect the generation of memory CD8+ CTL is by activating and inducing the expression of costimulatory molecules upon antigen-presenting cells. It has recently become apparent that CD40L-CD40 interactions play a central role in the cognate interactions between CD4+ T cells and antigen-presenting cells, which are necessary for both cell types to become fully activated (22, 24, 71). CD40L-deficient mice have been shown to express reduced levels of B7 in their lymphoid tissues during the immune response to an adenoviral vector (71); other costimulatory molecules known to be induced by CD40L-mediated interactions are CD44H and ICAM-1 (27, 57). That CD4+ T cells provide help not only for the generation of memory CTLp but also for other CD8+ T-cell responses by inducing costimulatory activity on antigen-presenting cells is an attractive hypothesis, as it can account for the differences observed in the requirements for CD4+ T-cell help in different systems (examples of which were discussed above). In situations in which the costimulatory activity necessary for a particular CD8+ T-cell response is provided by an alternative mechanism, the response will appear to be CD4 independent. For example, certain subtypes of influenza virus are able to induce expression of CD86 on antigen-presenting cells, and the CD8+ T-cell response to these influenza subtypes is CD4+ T-cell independent, whereas CD4+ T-cell help is required to elicit CD8+ T-cell responses to other influenza subtypes under the same conditions (69). We favor this mechanism as being most likely to account for the CD4+ T-cell dictated deficit in memory CD8+ CTLp generation in CD40L-deficient mice because it could readily account for our observation that memory CTLp generation but not effector CTL activity is affected in the early stages of the immune response. The lineage relationship between effector and memory CTL has long been a subject of debate; however, it was recently shown that induction of the two can be differentiated on the basis of their requirements for costimulation (43). We hypothesize that the costimulatory requirements for the effector CTL response are adequately met in LCMV-infected CD40L-deficient mice (likely because they can be induced by CD4+ T-cell independent mechanisms), whereas those for memory CTLp generation are not.

In summary, our data illustrate that the generation of CD8+ CTLp is a process that can be distinguished from the production of effector CTL by its greater dependence on CD40L. We hypothesize that the role of CD40L (expressed on CD4+ T cells) is to activate antigen-presenting cells to express costimulatory activity necessary to drive the differentiation of CD8+ T cells into memory cells. How dependent the generation of memory CTLp (and also the effector CTL response) is on CD40L will depend on the nature and level of costimulatory activity induced on antigen-presenting cells by other mechanisms. These findings have important implications for the design of antiviral vaccines, suggesting that in order to induce an optimal memory CTL response, the vaccine should be formulated to stimulate a good primary CD4+ T-cell response and/or should include adjuvants which activate the expression of high levels of costimulatory activity on antigen-presenting cells. Further, these findings suggest that it should be possible to induce long-lived CTL responses in situations of CD4+ T-cell deficiency (e.g., in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected patients) provided that the antigenic challenge is designed to induce suitable costimulatory activity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grants AI37430 (P.B.), AG04342 (P.B. and M.B.A.O.), and AI09484 (M.B.A.O.). I.S.G. was an Associate and R.A.F. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. I.S.G. is currently a Fellow of the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation. D.F.T. was the recipient of a Centennial Fellowship from the Medical Research Council of Canada.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed R, Gray D. Immunological memory and protective immunity: understanding their relation. Science. 1996;272:54–60. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armitage R J, Fanslow W C, Strockbine L, Sato T A, Clifford K N, Macduff B M, Anterson D M, Gimpel S D, Davis-Smith T, Malisewski C R, Clark E A, Smith C A, Grabstein K H, Cosman D, Spriggs M K. Molecular and biological characterization of a murine ligand for CD40. Nature. 1992;357:80–82. doi: 10.1038/357080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bachmann M F, Kundig T M, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel R M. Protection against immunopathological consequences of a viral infection by activated but not resting cytotoxic T cells: T cell memory without “memory T cells”? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:640–645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Battegay M, Moskophidis D, Rahemtulla A, Hengartner H, Mak T W, Zinkernagel R M. Enhanced establishment of a virus carrier state in adult CD4+ T-cell-deficient mice. J Virol. 1994;68:4700–4704. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.7.4700-4704.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beverley P C L. Is T-cell memory maintained by crossreactive stimulation? Immunol Today. 1990;11:203–205. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(90)90083-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borrow P, Tishon A, Lee S, Xu J, Grewal I S, Oldstone M B A, Flavell R A. CD40L-deficient mice show deficits in antiviral immunity and have an impaired memory CD8+ CTL response. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2129–2142. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruno L, Kirberg J, Von Boehmer H. On the cellular basis of immunological T-cell memory. Immunity. 1995;2:37–43. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buller R M, Holmes K L, Hugin A, Frederickson T N, Morse I H. Induction of cytotoxic T-cell responses in vivo in the absence of CD4 helper cells. Nature. 1987;328:77–79. doi: 10.1038/328077a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Byrne J A, Oldstone M B A. Biology of cloned cytotoxic T lymphocytes specific for lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus: clearance of virus in vivo. J Virol. 1984;51:682–686. doi: 10.1128/jvi.51.3.682-686.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cardin R D, Brooks J W, Sarawar S R, Doherty P C. Progressive loss of CD8+ T cell mediated control of a γ-herpes virus in the absence of CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1996;184:863–871. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cella M, Scheidegger D, Palmer-Lehman K, Lane P, Lanzavecchia A, Alber G. Ligation of CD40 on dendritic cells triggers production of high levels of interleukin-12 and enhances T cell stimulatory capacity: T-T help via APC activation. J Exp Med. 1996;184:747–752. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christensen J P, Marker O, Thomsen A R. The role of CD4+ T cells in cell-mediated immunity to LCMV: studies in MHC class I and class II deficient mice. Scand J Immunol. 1994;40:373–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1994.tb03477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coligan J E, Kruisbeek A M, Margulies D H, Shevach E M, Strober W, editors. Current protocols in immunology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 14.de St. Groth S F. The evaluation of limiting dilution assays. J Immunol Methods. 1982;49:11–23. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(82)90269-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Rosa F, Matzinger P. Long lasting CD8 T cell memory in the absence of CD4 T cells or B cells. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2153–2163. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dutko F J, Oldstone M B. Genomic and biological variation among commonly used lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus strains. J Gen Virol. 1983;64:1689–1698. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-64-8-1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foy T M, Durie F H, Noelle R J. The expansive role of CD40 and its ligand, gp39, in immunity. Semin Immunol. 1994;6:259–266. doi: 10.1006/smim.1994.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foy T M, Page D M, Waldschmidt T J, Schoneveld A, Laman J D, Masters S R, Tygrett L, Ledbetter J A, Aruffo A, Classen E, Xu J C, Flavell R A, Oehen S, Hedric S M, Noelle R J. An essential role for gp39, the ligand for CD40, in thymic selection. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1377–1388. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galy A H, Spits H. CD40 is functionally expressed on human thymic epithelial cells. J Immunol. 1992;149:775–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao E-K, Lo D, Sprent J. Strong T cell tolerance in parent into F1 bone marrow chimeras prepared with supralethal irradiation. Evidence for clonal deletion and anergy. J Exp Med. 1990;171:1101–1121. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.4.1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gray D, Siepmann K, Wohlleben G. CD40 ligation in B cell activation, isotype switching and memory development. Semin Immunol. 1994;6:303–310. doi: 10.1006/smim.1994.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grewal I S, Flavell R A. A central role of CD40 ligand in the regulation of CD4+ T-cell responses. Immunol Today. 1996;17:410–414. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)10030-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grewal I S, Flavell R A. The role of CD40 ligand in costimulation and T-cell activation. Immunol Rev. 1996;153:85–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1996.tb00921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grewal I S, Foellmer H G, Grewal K D, Xu J, Hardardottir F, Baron J L, Janeway C A, Flavell R A. Requirement for CD40 ligand in costimulation induction, T cell activation, and experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Science. 1996;273:1864–1867. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5283.1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grewal I S, Xu J, Flavell R A. Impairment of antigen-specific T cell priming in mice lacking CD40 ligand. Nature. 1995;378:617–620. doi: 10.1038/378617a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guerder S, Matzinger P. A fail-safe mechanism for maintaining self-tolerance. J Exp Med. 1992;176:553–564. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.2.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo Y, Wu Y, Shinde S, Sy M S, Aruffo A, Liu Y. Identification of a costimulatory molecule rapidly induced by CD40L as CD44H. J Exp Med. 1996;184:955–961. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hermann P, Blanchard D, de Saint-Vis B, Fossiez F, Gaillard C, Vanbervliet B, Briere F, Banchereau J, Galizzi J-P. Expression of a 32 kD ligand for the CD40 antigen on activated human lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:961–964. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hermann P, Van-Kooten C, Gaillard C, Banchereau J, Blanchard D. CD40 ligand-positive CD8+ T cell clones allow B cell growth and differentiation. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:2972–2977. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830251039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hollenbaugh D, Grosmaire L, Kullas C D, Chalupny N J, Noelle R J, Stamenkovic I, Ledbetter J A, Aruffo A. The human T cell antigen gp39, a member of the TNF gene family, is a ligand for the CD40 receptor: expression of a soluble form of gp39 with B cell co-stimulatory activity. EMBO J. 1992;11:4313–4321. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05530.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hollenbaugh D, Ochs H D, Noelle R J, Ledbetter J A, Aruffo A. The role of CD40 and its ligand in the regulation of the immune response. Immunol Rev. 1994;138:23–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1994.tb00845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hou S, Hyland L, Ryan K W, Portner A, Doherty P C. Virus-specific CD8+ T-cell memory determined by clonal burst size. Nature. 1994;369:652–654. doi: 10.1038/369652a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kasaian M T, Leite-Morris K A, Biron C A. The role of CD4+ cells in sustaining lymphocyte proliferation during lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection. J Immunol. 1991;146:1955–1963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kirberg J, Bruno L, von Boehmer H. CD4+8− help prevents rapid deletion of CD8+ cells after a transient response to antigen. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:1963–1967. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koch F, Stanzl U, Jennewein P, Janke K, Heufler C, Kampgen E, Romani N, Schuler G. High level IL-12 production by murine dendritic cells: upregulation via MHC class II and CD40 molecules and down-regulation by IL-10. J Exp Med. 1996;184:741–746. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kundig T M, Bachmann M F, Oehen S, Hoffman U W, Simard J J L, Kalberer C P, Pircher H, Ohashi P S, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel R M. On the role of antigen in maintaining cytotoxic T-cell memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9716–9723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kundig T M, Bachmann M F, Ohashi P S, Pircher H, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel R M. On T cell memory: arguments for antigen dependence. Immunol Rev. 1996;150:63–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1996.tb00696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laman J D, Classen E, Noelle R J. Functions of CD40 and its ligand, gp39 (CD40L) Crit Rev Immunol. 1996;16:59–108. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v16.i1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lane P, Traunecker A, Hubele S, Inui S, Lanzavecchia A, Gray D. Activated human T cells express a ligand for the human B cell-associated antigen CD40 which participates in T cell-dependent activation of B lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:2573–2578. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830221016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lau L L, Jamieson B D, Somasundaram T, Ahmed R. Cytotoxic T-cell memory without antigen. Nature. 1994;369:648–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leist T P, Cobbold S P, Waldmann H, Aguet M, Zinkernagel R M. Functional analysis of T lymphocyte subsets in antiviral host defense. J Immunol. 1987;138:2278–2281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu Y, Mullbacher A. The generation and activation of memory class I restricted cytotoxic T cell responses to influenza A virus in vivo does not require CD4+ T cells. Immunol Cell Biol. 1989;67:413–420. doi: 10.1038/icb.1989.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu Y, Wenger R H, Zhao M, Nielsen P J. Distinct costimulatory molecules are required for the induction of effector and memory cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1997;185:251–262. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.2.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matloubian M, Concepcion R J, Ahmed R. CD4+ T cells are required to sustain CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell responses during chronic viral infection. J Virol. 1994;68:8056–8063. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8056-8063.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moskophidis D, Cobbold S P, Waldmann H, Lehmann-Grube F. Mechanism of recovery from acute virus infection: treatment of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus-infected mice with monoclonal antibodies reveals that Lyt-2+ T lymphocytes mediate clearance of virus and regulate the antiviral antibody response. J Virol. 1987;61:1867–1874. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.6.1867-1874.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moskophidis D, Lechner F, Pircher H, Zinkernagel R M. Virus persistence in acutely infected immunocompetent mice by exhaustion of antiviral cytotoxic effector T cells. Nature. 1993;362:758–761. doi: 10.1038/362758a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mullbacher A. The long-term maintenance of cytotoxic T cell memory does not require persistence of antigen. J Exp Med. 1994;179:317–321. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nahill S R, Welsh R M. High frequency of cross-reactive cytotoxic T lymphocytes elicited during the virus-induced polyclonal cytotoxic T lymphocyte response. J Exp Med. 1993;177:317–327. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.2.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nash A A, Jayasuriya A, Phelan J, Cobbold S P, Waldmann H, Prospero T. Different roles for L3T4+ and Lyt2+ T cell subsets in the control of an acute herpes simplex virus infection of the skin and nervous system. J Gen Virol. 1987;68:825–833. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-68-3-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Noelle R J. CD40 and its ligand in host defence. Immunity. 1996;4:415–419. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80408-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Noelle R J, Roy M, Shephard D M, Stamenkovic I, Ledbetter J A, Aruffo A. A novel ligand on activated T helper cells binds CD40 and transduces the signal for the cognate activation of B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6550–6554. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rahemtulla A, Fung-Leung W P, Schilham M W, Kundig T M, Sambhara S R, Narendran A, Arabian A, Wakeham A, Paige C J, Zinkernagel R M, Miller R G, Mak T W. Normal development and function of CD8+ cells but markedly decreased helper cell activity in mice lacking CD4. Nature. 1991;353:180–184. doi: 10.1038/353180a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roy M, Waldschmidt T, Aruffo A, Ledbetter J A, Noelle R J. The regulation of the expression of gp39, the CD40 ligand, on normal and cloned CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 1993;151:2497–2510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sad S, Krishnan L, Bleackley R C, Kagi D, Hengartner H, Mosmann T R. Cytotoxicity and weak CD40L expression of CD8(=) type 2 cytotoxic T cells restricts their potential B cell helper activity. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:914–922. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sauzet J-P, Gras-Masse H, Guillet J-G, Gomard E. Influence of strong CD4 epitope on long-term virus-specific cytotoxic T cell responses induced in vivo with peptides. Int Immunol. 1996;8:457–465. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.4.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Selin L K, Nahill S R, Welsh R M. Cross-reactivities in memory cytotoxic T lymphocyte recognition of heterologous viruses. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1933–1943. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.6.1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shinde S, Wu Y, Guo Y, Niu Q T, Xu J C, Grewal I S, Flavell R A, Liu Y. CD40L is important for induction of, but not response to, costimulatory activity—ICAM-1 as the 2nd costimulatory molecule rapidly up-regulated by CD40L. J Immunol. 1996;157:2764–2768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Simpson E, Gordon R D. Responsiveness to hy antigen Ir gene complementation and target cell specificity. Immunol Rev. 1977;35:59–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1977.tb00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sprent J. Immunological memory. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:371–379. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stamenkovic I, Clark E A, Seed B. A B-lymphocyte activation molecule related to the nerve growth factor receptor and induced by cytokines in carcinomas. EMBO J. 1989;8:1403–1410. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03521.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stout R, Suttles J. The many roles of CD40:CD40L interactions in cell-mediated inflammatory immune responses. Immunol Today. 1996;17:487–492. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)10060-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thomsen A R, Johansen J, Marker O, Christensen J P. Exhaustion of CTL memory and recrudescence of viremia in lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus-infected MHC class II-deficient mice and B cell deficient mice. J Immunol. 1996;157:3074–3080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tough D F, Borrow P, Sprent J. Intense bystander proliferation of T cells in vivo induced by viruses and type I interferon. Science. 1996;272:1947–1950. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tough D F, Sprent J. Turnover of naive- and memory-phenotype T cells. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1127–1135. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van Essen D, Kikutani H, Gray D. CD40 ligand-transduced co-stimulation of T cells in the development of helper function. Nature. 1995;378:620–623. doi: 10.1038/378620a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van Kooten C, Banchereau J. CD40-CD40 ligand: a multifunctional receptor-ligand pair. Adv Immunol. 1996;61:1–77. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60865-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.von Boehmer H, Haas W, Jerne N K. Major histocompatibility complex-linked immune-responsiveness is acquired by lymphocytes differentiating in the thymus of high-responder mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:2439–2442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.5.2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.von Herrath M G, Yokoyama M, Dockter J, Oldstone M B A, Whitton J L. CD4-deficient mice have reduced levels of memory cytotoxic T lymphocytes after immunization and show diminished resistance to subsequent virus challenge. J Virol. 1996;70:1072–1079. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1072-1079.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu Y, Liu Y. Viral induction of co-stimulatory activity on antigen-presenting cells bypasses the need for CD4+ T-cell help in CD8+ T-cell responses. Curr Biol. 1994;4:499–505. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00110-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xu J, Foy T M, Lamar J D, Elliott E A, Dunn J J, Waldschmidt T J, Elsemore J, Noelle R J, Flavell R A. Mice deficient for the CD40 ligand. Immunity. 1994;1:423–431. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yang Y, Wilson J M. CD40 ligand-dependent T cell activation: requirement of B7-CD28 signalling through CD40. Science. 1996;273:1862–1864. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5283.1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]