Significance

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) is a critical regulator of inflammatory responses against harmful stimuli such as infections. However, excessive amount of TNF can cause autoimmune diseases. Current anti-TNF therapeutics are expensive and can induce dangerous side effects due to global TNF blockade. Hence, specific targeting of TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1), rather than the cytokine itself, is a highly sought-after strategy to inhibit downstream NF-κB activation and attenuate inflammation. Here, we show using a peptide-based allosteric inhibitor that it is possible to target the conformationally active region of TNFR1 to stabilize inactive receptor conformations that leads to a receptor–ligand complex incapable of signaling. Further optimization of this peptide may generate more effective and cheaper TNFR1 inhibitors.

Keywords: TNFR1 signaling, conformational dynamics, noncompetitive inhibition, receptor-specific inhibition, anti-inflammatory

Abstract

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor 1 (TNFR1) plays a pivotal role in mediating TNF induced downstream signaling and regulating inflammatory response. Recent studies have suggested that TNFR1 activation involves conformational rearrangements of preligand assembled receptor dimers and targeting receptor conformational dynamics is a viable strategy to modulate TNFR1 signaling. Here, we used a combination of biophysical, biochemical, and cellular assays, as well as molecular dynamics simulation to show that an anti-inflammatory peptide (FKCRRWQWRMKK), which we termed FKC, inhibits TNFR1 activation allosterically by altering the conformational states of the receptor dimer without blocking receptor–ligand interaction or disrupting receptor dimerization. We also demonstrated the efficacy of FKC by showing that the peptide inhibits TNFR1 signaling in HEK293 cells and attenuates inflammation in mice with intraperitoneal TNF injection. Mechanistically, we found that FKC binds to TNFR1 cysteine-rich domains (CRD2/3) and perturbs the conformational dynamics required for receptor activation. Importantly, FKC increases the frequency in the opening of both CRD2/3 and CRD4 in the receptor dimer, as well as induces a conformational opening in the cytosolic regions of the receptor. This results in an inhibitory conformational state that impedes the recruitment of downstream signaling molecules. Together, these data provide evidence on the feasibility of targeting TNFR1 conformationally active region and open new avenues for receptor-specific inhibition of TNFR1 signaling.

Tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (TNFR1) is a central mediator for inflammatory signal transduction (1). It is activated upon binding tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and lymphotoxin-alpha which are native ligands of the receptor. Ligand stimulation leads to the recruitment of intracellular signaling complex and a series of phosphorylation cascades, resulting in IκBα degradation and NF-κB activation (2–4). TNFR1 activation is associated with several autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, and multiple sclerosis (3). Current anti-TNF therapies, which act through global sequestration of free ligands, induce severe adverse effects due to off-target inhibition of the closely related TNFR2 that is required for immune modulation (5, 6). Hence, receptor-specific inhibition of TNFR1, rather than the ligands, is an intensely pursued strategy to develop more effective inhibitors of TNFR1 signaling (7, 8). The most promising approach will be to make use of the insights from the receptor structure–function relationship and the available crystal structures to explore new pharmacophores which could lead to new paradigms in structure-based drug design.

Recently, a new crystal structure (PDB:7KP7) revealed that both TNF trimer and TNFR1 dimers coexist in a ligand-bound active signaling complex, with each of the monomer of the trimeric TNF bound to a TNFR1 dimer in a threefold symmetry (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 A and B) (9). Significantly, this structure has reconciled the inconsistencies shown by the previous structures of ligand-bound receptor monomer (PDB:1TNR) (10) and preligand assembled receptor dimer (PDB:1NCF) (11) held together by the preligand assembly domain (PLAD) (12) and clarified that ligand-bound receptor can still form intact dimers under physiological conditions (Fig. 1A). It is important to note that all current crystal structures were based on interactions at the extracellular domain (ECD) of TNFR1 and there is no available structure for the entire full-length TNFR1. This study further shows experimental evidence on receptor clustering and aggregation in a network formation (9) and provides a unique model of TNFR1 activation which is supported by several previous studies (13–16). Based on this model, there are three main strategies to modulate the TNFR1/TNF signaling complex that includes the ablation of receptor–ligand interaction, disruption of receptor–receptor interaction, and perturbation of receptor conformational dynamics. Based on our previous studies, we have shown that allosteric or noncompetitive inhibition of TNFR1 signaling is more effective than competitive inhibition (17), suggesting that targeting receptor conformational dynamics may be the best strategy.

Fig. 1.

FKC interacts with TNFR1 and induces receptor conformational change. (A) Schematic representation of the TNFR1/TNF functional network consisting of TNFR1 dimers held together by TNF trimers (orange) upon ligand binding to form active signaling complex. PLAD: preligand assembly domain, ECD: extracellular domain, and CD: cytosolic domain. (B) Schematic representation of the TNFR1 FRET biosensor with TNFR1ΔCD–GFP and TNFR1ΔCD–RFP used as the FRET pair. (C) Overexpression of the TNFR1 FRET biosensor in HEK293 cells leads to an efficient FRET observed in the donor–acceptor (indicated by DA) FRET pair as compared to the donor-only (indicated by D) no FRET control. (D and E) FKC reduces FRET of the TNFR1 biosensor in (D) a dose-dependent manner and (E) with an EC50 of 25 µM. (F) FKC does not cause any FRET change in the TNFR2 biosensor, which is acting as a control for receptor-specific interaction. (G) FKC is a 12-mer peptide (FKCRRWQWRMKK) that can induce TNFR1 conformational change. Data are means ± SD of N = 4 independent experiments. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 and ns indicates nonsignificance by unpaired Student’s t test for comparison between two samples and one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons.

The first seminal study that proposed the feasibility of allosteric inhibition of TNFR1 identified a small molecule (F002) that was bound to a pseudoallosteric cavity and was able to induce a subtle receptor conformational change to inhibit TNFR1 signaling (18). However, the functional efficacy of F002 being 60-fold weaker than its binding affinity to TNFR1, together with the speculation that F002 may potentially lead to reduced ligand binding (18), suggests some kind of competitive inhibition that makes it less efficient (19). Hence, it has been suggested that allosteric inhibitors that are unencumbered by competition may be more efficient (20, 21). In our previous study, we described a small molecule (DS42) that acts through a noncompetitive mechanism by binding at the PLAD to induce long-range perturbation of TNFR1 conformational dynamics mediated through the conformationally active region (17). The conformationally active region is postulated to be located at the β-hairpin (TNFR1 residues 100–117) around the ligand-binding domain (LBD) with a hinge-bending motion at the axis formed by residues 80, 104, 117, and 133 (13, 17). Binding of DS42 leads to an opening of the membrane-proximal domain and inhibition of TNFR1 signaling without affecting ligand binding and receptor dimerization (17). However, the long-range perturbation, rather than direct targeting of the conformationally active region may explain in part its lack of potency. It also makes the optimization of the small molecule difficult as the mechanism of the long-range propagation remains unclear. In addition, direct targeting of the conformationally active region, consisting of ligand binding residues, may perturb native ligand binding which is undesired. Hence, there is a need to develop new TNFR1 inhibitors that can stabilize the region between receptor dimer away from the ligand binding sites to adopt inactive conformations and induce the formation of nonfunctional receptor–ligand signaling complex, without competing with the ligands or the other receptor monomers.

To target the region between the receptor dimer that is away from the ligand binding sites, peptides with larger surface area, rather than small molecules, may be more suitable to fit into this region (22, 23). This has shown to be feasible by an octapeptide 2305 (TEEEQQLY) that generates a conformational change in IL-23 receptor without affecting ligand binding to noncompetitively inhibit IL-23 signaling (24). In the context of targeting TNFR1 signaling, antimicrobial and immunomodulatory peptides such as bovine bactenecin (a natural host defense peptide) and bovine lactoferrin (an iron-binding protein) are the major classes of peptides that have been reported to inhibit receptor downstream signaling and possess anti-inflammatory properties (25, 26). Although initial studies examined the anti-inflammatory effects of full-length bovine bactenecin and bovine lactoferrin, recent studies focused on peptides derived from these proteins because of their enhanced biological activities based on the optimized amino acid sequence and length (27–29). Bovine bactenecin derived innate defense regulator peptide IDR (VQRWLIVWRIRK) and bovine lactoferrin-derived peptide FKC (FKCRRWQWRMKK) have been optimized for their anti-inflammatory properties and specifically shown to inhibit NF-κB activation (30–33). Although the exact molecular mechanisms of IDR and FKC are unclear, it is possible that they target TNFR1 to impart their inhibitory effects.

In this study, we investigated whether FKC and IDR peptides can target TNFR1 to inhibit downstream signaling. To do this, we tested the interaction of both FKC and IDR peptides with TNFR1 fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) biosensor which can measure the inter-monomeric spacing of the receptor and probe previously undetected conformational states of the preligand TNFR1 dimer (17, 34–36). We showed that FKC, but not IDR, interacts and perturbs TNFR1 conformational dynamics. We further demonstrated that FKC inhibits TNFR1 signaling in HEK293 cells and attenuates inflammation in vivo. Using all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulation, we illustrated that FKC binds at the conformationally active region of TNFR1 dimer to induce receptor conformational changes, which results in the receptor losing flexibility and adopting an open and inactive conformation. Finally, we demonstrated that the inactive conformational state stabilized by FKC does not lead to the ablation of ligand binding and disruption of receptor–receptor interaction but impedes the recruitment of downstream signaling molecules, making it a truly allosteric inhibitor of TNFR1 signaling.

Results

FKC Interacts with TNFR1 and Induces Receptor Conformational Change.

We first examined whether the two peptides, FKC and IDR, interact with TNFR1 to impart their anti-inflammatory effects such as inhibition of NF-κB activation by testing their functions in a TNFR1 FRET biosensor formed by preligand receptor dimers (Fig. 1B). Overexpression of the TNFR1 donor–acceptor (DA) FRET pair in HEK293 cells illustrated efficient FRET compared to the donor-only (D) no FRET control (Fig. 1C), which is consistent with our previous studies (17, 34–37). Importantly, FKC reduced FRET in the TNFR1 biosensor in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1D) with a half maximal effective concentration (EC50) of 25 µM (Fig. 1E), indicating that FKC interacts with TNFR1 to induce conformational change. On the other hand, IDR did not cause any FRET change to the TNFR1 biosensor (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A), suggesting that IDR does not induce TNFR1 conformational change and might be acting through alternative inhibitory mechanisms or signaling pathways to attenuate inflammation. As a critical control, we also tested the effect of FKC in a TNFR2 FRET biosensor which showed efficient FRET in the preligand dimeric form (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 B and C), consistent with previous study (38). Treatment of FKC did not cause a FRET change in the TNFR2 biosensor (Fig. 1F and SI Appendix, Fig. S2C), further demonstrating the specific interaction of FKC with TNFR1. These data revealed that FKC, a 12-mer peptide (FKCRRWQWRMKK) derived from bovine lactoferricin, which is a segment of bovine lactoferrin (39), is able to induce TNFR1 conformational change (Fig. 1G) and is a promising candidate for our subsequent characterizations. Moreover, molecular docking of bovine lactoferricin, a peptide with 25 amino acids (AA), on TNFR1 suggests that the first 12AA segment consisting entirely of FKC has a stronger binding free energy than the second 13AA segment (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 A and B), further supporting the interaction of FKC with TNFR1.

FKC Inhibits TNFR1 Signaling in a Receptor-specific Manner.

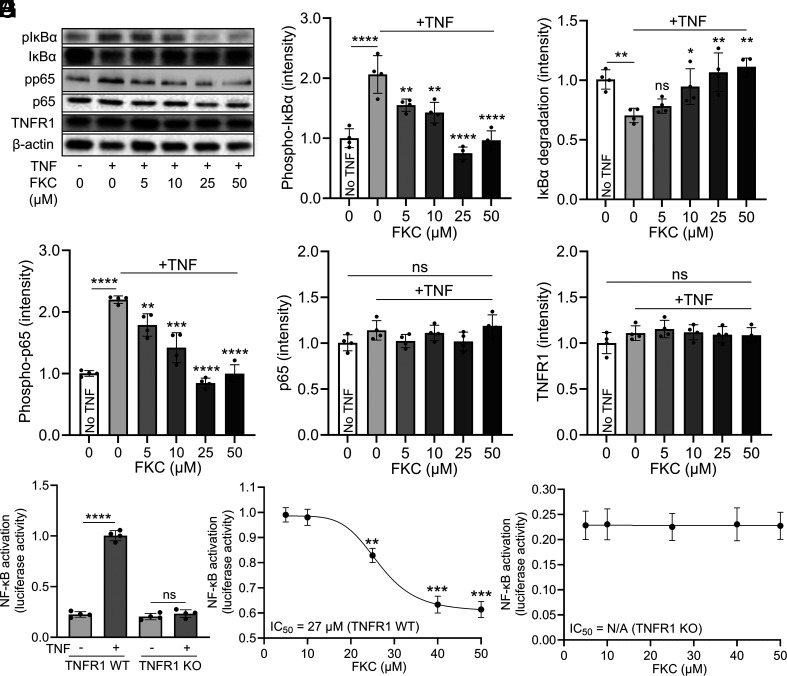

To investigate whether FKC can functionally inhibit TNFR1 signaling, we examined its effect on receptor downstream pathways including IκBα degradation and NF-κB activation (Fig. 2A). TNF not only induced phosphorylation of IκBα (Fig. 2B) but also IκBα degradation (Fig. 2C) in HEK293 cells, and FKC treatment inhibited these effects in a dose-dependent manner between 5 and 50 µM (Fig. 2 B and C). Correspondingly, TNF increased the phosphorylation of p65 which were prevented by FKC (Fig. 2D), demonstrating the inhibitory effect of the peptide on TNFR1 downstream signaling. As important controls, we showed that the expression levels of p65 (Fig. 2E) and TNFR1 (Fig. 2F) are not affected by FKC. We then used a luciferase reporter assay to measure NF-κB activity where cells were transfected with vectors containing the NF-κB response element and activation of NF-κB leads to increased luciferase signals. TNF stimulated NF-κB activation to fivefold the basal level in HEK293 cells with endogenous wild-type TNFR1 (TNFR1 WT) (Fig. 2G). FKC inhibited NF-κB activation in TNFR1 WT HEK293 cells in a dose-dependent manner with a half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 27 µM (Fig. 2H), which is consistent with the results observed in the TNFR1 FRET assay. To examine whether FKC requires TNFR1 for its inhibitory action, we tested the effect of FKC in TNFR1 knockout (TNFR1 KO) HEK293 cells. The TNFR1 KO cells have a basal NF-κB activity of ~20% relative luciferase level, similar to that of the unstimulated TNFR1 WT cells. This has been suggested to be due to ligand-free constitutive signaling of other cytokine receptors (40), making it a good control to test whether FKC affects other proteins that modulate NF-κB signaling. First, TNF did not stimulate NF-κB activation in TNFR1 KO cells (Fig. 2G), confirming the lack of TNFR1 signaling. Importantly, FKC did not attenuate the basal NF-κB activity in TNFR1 KO cells, indicating its specificity in inhibiting TNFR1 signaling (Fig. 2I).

Fig. 2.

FKC inhibits TNFR1 signaling in a receptor-specific manner. (A) Western blotting analysis to characterize the effect of FKC in TNF-induced TNFR1 downstream signaling pathways including IκBα degradation and NF-κB activation. (B–F) FKC inhibits TNF-induced (B) phosphorylation of IκBα (pIκBα), (C) IκBα degradation, (D) phosphorylation NF-κB component p65 (pp65) in HEK293 cells in a dose-dependent manner without affecting the levels of (E) NF-κB component p65 and (F) TNFR1. β-actin was used as a loading control. (G) TNF stimulates NF-κB activation in HEK293 cells with WT TNFR1 but not in TNFR1 KO cells. (H) FKC inhibits TNF-induced NF-κB activation in HEK293 cells in a dose-dependent manner with an IC50 of 27 µM. (I) FKC does not inhibit basal NF-κB activation in TNFR1 KO HEK293 cells. Data are means ± SD of N = 4 independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 and ns indicates nonsignificance by unpaired Student’s t test for comparison between two samples and one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons.

To further determine the specificity of FKC, we tested its effect on TNFR1-associated death domain (TRADD) and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) induced NF-κB activation. Being an essential adaptor protein recruited to TNFR1 upon ligand activation of the receptor, TRADD overexpression has been reported to induce NF-κB activation independent of receptor activation (41). On the other hand, IL-1β is a cytokine that binds IL-1 receptor to stimulate NF-κB activation (42). These assays examine whether FKC affects TNFR1 downstream signaling molecules or other receptors mediating alternative NF-κB signaling pathways, making them the most complete controls for specificity. Overexpression of TRADD in HEK293 cells led to a sixfold increase in NF-κB activation compared to control without TRADD overexpression (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A) and FKC did not inhibit this activation (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B). IL-1β treatment stimulated NF-κB activation to 10-fold of the basal level (SI Appendix, Fig. S4C) and again FKC did not exhibit any inhibitory effect (SI Appendix, Fig. S4D). Finally, we confirmed that FKC does not have any toxic effect in HEK293 cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S4E). These results illustrated that FKC requires TNFR1 for its activity and the inhibitory effects observed are not due to any indirect effect that FKC has on other downstream signaling molecules or cytokine receptors.

FKC Attenuates Inflammation in Mice with Intraperitoneal TNF Injection.

Having shown the specific interaction of FKC with TNFR1 and its receptor-specific inhibition of downstream signaling, we investigated the effect of FKC in vivo by using a simple mouse model of inflammation with intraperitoneal TNF injection (43). First, TNF injection in both male and female mice induced a significant increase in TNF, MCP-1, IFN-γ, IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-6 cytokine levels in mouse plasma compared to the saline control (Fig. 3A). FKC treatment (20 and 40 mg/kg) reduced all cytokine levels in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3A), indicating the effectiveness of FKC in reducing overall inflammation in mice. As a control, we checked that there is no aggregation of the peptide at the highest dose as characterized by dynamic light scattering (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A). We then examined whether FKC affects macrophage activation in liver, kidney, and lung. We confirmed the localization of FKC in all tissues through the presence of rhodamine-conjugated FKC (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 B–D). In all organs, we observed that TNF-induced macrophage activation as shown by the increase in the CD68-positive cells and FKC (40 mg/kg) reduced macrophage activation (Fig. 3 B and C and SI Appendix, Figs. S6 A–C and S7 A and B), further demonstrating its effect in reducing inflammation. Finally, we determined whether the effect of FKC arises from inhibiting TNFR1 signaling by probing the receptor downstream signaling molecules in different tissues. We illustrated that TNF injection not only induced phosphorylation of IκBα but also IκBα degradation, together with phosphorylation of p65 in all tissues, and FKC treatment at 40 mg/kg inhibited these downstream signaling (Fig. 3 D–F and SI Appendix, Fig. S8 A–F). These results confirmed that FKC is acting through inhibiting TNFR1 to attenuate inflammation in vivo and similar inhibitory effects were observed in both male and female mice.

Fig. 3.

FKC attenuates inflammation in mice with intraperitoneal TNF injection. (A) TNF induces an increase in the plasma cytokines levels of TNF, MCP-1, IFN-γ, IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in both male and female mice, and FKC reduces all cytokine levels in a dose-dependent manner. (B and C) Immunostaining of liver, kidney, and lung tissues and image quantification illustrating the effect of FKC (40 mg/kg) in reducing macrophage activation in both male and female mice as characterized through CD68-positive signals. (D–F) Western blotting analysis and quantification of liver, kidney, and lung tissues showing the effect of FKC (40 mg/kg) in inhibiting TNFR1 signaling in both male and female mice as characterized by changes in the level of downstream signaling molecules including phosphorylation of IκBα (pIκBα), IκBα degradation, phosphorylation of NF-κB component p65 (pp65), p65, and TNFR1, with β-actin as a loading control. Representative images and blots shown were obtained from male mice. Data are means ± SD of N = 12 mice (N = 6 male mice and N = 6 female mice) per treatment group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, and ns indicates nonsignificance by one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons.

FKC Targets the Conformationally Active Region of TNFR1 and Perturbs Receptor Conformational Dynamics.

To examine the binding site of FKC, we first utilized a computational based molecular docking approach to probe for the peptide interaction with TNFR1. First, a physiologically relevant model of the proposed functional complex of TNFR1 and TNF ligand was constructed, formed by three TNFR1 dimers bound to a TNF trimer with a threefold symmetry (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A) (9). The protein assembly is composed by the three dimers, namely TNFR1A–TNFR1D, TNFR1B–TNFR1E, and TNFR1C–TNFR1F, bound to a TNF trimer, namely TNFX–TNFY–TNFZ (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). By utilizing a single dimeric structure (TNFR1B–TNFR1E), 10 molecular poses of the FKC interacting with TNFR1 were obtained using the HPEPDOCK docking program (SI Appendix, Fig. S9A). Based on higher-ranking docking scores, peptide interaction at the dimer interface, and binding locations at the druggable sites on the ECD of the TNFR1 dimer, including the PLAD, LBD, and the conformationally active region of the receptor involving cysteine-rich domains (CRD) 2/3 (SI Appendix, Fig. S9B), three molecular poses of the docked FKC, pose 1, pose 4, and pose 6 (SI Appendix, Fig. S9C) were selected for further evaluation using unbiased MD simulations to test their interacting strength and binding stability with TNFR1. Importantly, the only molecular pose that displayed stable interactions through the 250 ns long MD simulations was the pose 4 with FKC bound in the vicinity of the CRD2/3, which is close to the conformationally active region of the receptor.

In the starting position of pose 4 from the molecular docking, FKC established interactions mainly with residues in one of the receptor monomers (TNFR1E); however, as the MD simulation progresses, a repositioning of the peptide molecular pose induced the formation of interactions with residues in the other receptor monomer (TNFR1B) (Fig. 4A). From the time evolution of FKC along the 250 ns long MD simulation trajectory (Movie S1), we observed that the N-terminal segment of FKC (1-FKCRRW-6) explored conformations around a relatively confined space due to the formation of stable interaction with residues in both receptor monomers (Fig. 4A). While peptide residues F1, K2, and W6 formed interactions with residues in TNFR1E (e.g., F1-F115E, K2-E147E, and W6-Y106E), R5 strongly forms polar interactions with the carbonyl group from contiguous residues in TNFR1B (R5-N134B, R5-T135B, and R5-N136B) (Fig. 4B). This specific interaction appears to anchor the FKC conformations so that interaction involving residues at the C-terminal segment are subsequently stabilized, including Q7–Q130B, W8–K132B, R9–E109E, and K11–D93B (Fig. 4B). Time evolution plots involving relevant interactions, R5–N136B, R9–E109E, and W6–Y106E are shown (Fig. 4C), where it is evident that even though these interactions were not present in the initial protein complex, they were formed and conserved along the duration of the unbiased MD simulation. As indicated, not only FKC interacts with residues from both receptor monomers, but the nature of the interactions is also very diverse, including charged-charged (R9–E109B), aromatic (W6–Y106E), cation–pi (W8–K132B), and polar (R5–N134B) interactions (Fig. 4B). Overall, the binding of FKC between the TNFR1B–TNFR1E dimer and its interaction with residues from both monomers appear to hold them together.

Fig. 4.

FKC targets the conformationally active region of TNFR1 and perturbs receptor conformational dynamics. (A) Unbiased MD simulations of FKC performed starting from the selected docked pose (Pose 4) from the HPEPDOCK program. The time evolution of FKC along the 250 ns simulation is indicated using a color gradient (blue–white–red) as indicated in the bar at the top of the panel. Two residues of FKC, F1 and R5, are indicated using the sticks representation. (B) The MD simulation results suggest that the FKC peptide is bound at the dimer interface where it established interactions with both TNFR1 monomers at residues near the conformationally active region which involves the ligand binding loop. Important interactions with the TNFR1B (brown) and TNFR1E (cyan) are indicated by a green and purple dash lines, respectively. (C) Time evolution plots of distances (in Å) linked to interactions between FKC and residues in both monomers, particularly R5–N136B (FKC-chain B), R9–E109E (FKC-chain E), and W6–Y106E (FKC-chain E). (D) The rms-fluctuation (RMSF) was calculated for the Cα atoms of the segment covering the CRD2/3 (C70 to N116) for the last 50 ns of the trajectory (200 to 250 ns). In the FKC bound system (cyan line), a reduction in the fluctuations is observed in the segment Y103 to F115, relative to the system where the peptide is not present (grey line). (E) Total binding free energy between FKC and TNFR1 is −30.2 kcal/mol. The binding free energy per residue is also illustrated. (F) Coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) characterization probing the interaction of His-tagged FKC with full-length TNFR1, different TNFR1 segments (ECD: extracellular domain, PLAD: preligand assembly domain, and CD: cytosolic domain), TRADD, and full-length TNFR2. The presence of His-tagged FKC is illustrated by the His-tag antibody as a control.

Furthermore, the molecular pose of FKC placed it in close proximity with the conformationally active region around TNFR1 residues 100 to 117 previously identified to play a pivotal role in the receptor signal transduction (17). Indeed, a segment of the FKC peptide interacted with residues in the conformationally active region (e.g., Y106E, E109E, and F115E) that may disrupt the normal conformational changes of the domain and the concomitant receptor activation, explaining its antagonistic properties (Fig. 4B). To suggest the possible consequences of the FKC binding in this region, we calculated the RMSF for the Cα atoms of the segment covering the CRD2/3 (segment C70 to N116) for the last 50 ns of the trajectory (200 to 250 ns). A reduction in the fluctuations in the FKC bound system was observed in segment Y103 to F115 (highlighted in the rectangular box), relative to the system where the peptide is not present (Fig. 4D). This region forms a β-hairpin and contains the cysteine residue, C114, involved in a disulfide bridge (C98-C114). At the tip of the β-hairpin (residue E109), we observed the most significant change in the fluctuation. Our results suggest that FKC binding perturbed the dynamics of a conformationally active region that is central to the ligand-induced signal transduction of the receptor by making it more rigid in space.

By taking the final conformation of the peptide–protein complex as a representative structure, we further showed that the total binding free energy of FKC on TNFR1 ECD dimer is −30.2 kcal/mol (Fig. 4E), validating its strong interaction with the receptor. Using IDR as a control, we showed that the total binding free energy of IDR on TNFR1 ECD dimer at a similar docked pose is −28.5 kcal/mol (SI Appendix, Fig. S10 A and B). Although both FKC and IDR showed similar binding energies against TNFR1 ECD dimer, it is likely that IDR adopts a position that is not affecting the conformationally active region of the receptor or that no longer strengthens the dimer formation at these loci, hence not inducing a FRET change in the TNFR1 FRET biosensor (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). From the analysis of the molecular poses and the per residue contribution, we propose that residues R5, W6, and Q7 in FKC play an important role in the interaction with the TNFR1 dimer. The chemical nature of these residues is different in IDR, suggesting that this peptide may interact well with TNFR1 but without stabilizing the dimeric system as it is proposed in the case of FKC.

Importantly, we showed from docking of FKC on the TNFR2 ECD dimer with a similar pose that the total binding free energy is −6.5 kcal/mol (SI Appendix, Fig. S10 A and C), which is nearly fivefold less than its interaction with the TNFR1 ECD dimer and consistent with the lack of FRET changes in the TNFR2 FRET biosensor induced by FKC (Fig. 1F and SI Appendix, Fig. S2C). Since HawkDock decomposes the residue contribution, we observed that the main difference arises from various stabilizing interactions in the FKC/TNFR1 complex that are lost in the FKC/TNFR2 complex which could be attributed to the difference in the TNFR1 and TNFR2 sequences (SI Appendix, Fig. S10D). For instance, W6 in FKC no longer establishes aromatic interactions in TNFR2 since in this position TNFR2 contains a Leu instead of Tyr. In case of position W8 in FKC, this residue forms a cation-pi interaction with a Lys residue in TNFR1, which is absent in the FKC/TNFR2 complex because TNFR2 contains a Thr residue. Position K2 in FKC forms a salt-bridge with a Glu residue in TNFR1; however, this interaction is lost since TNFR2 bears a Thr residue. Lastly, position R5 in FKC is flanked by a Leu residue of TNFR1 that establishes a nonpolar interaction along their nonpolar sidechain region. At this position, TNFR2 has an Arg that may create some charge-charge repulsion with R5 from FKC.

To confirm the binding and interaction of FKC with TNFR1, we conducted co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) of His-tagged FKC with different segments of TNFR1 that are known to be stable, including full-length TNFR1, PLAD, ECD, and the cytosolic domain (CD), together with the downstream molecule TRADD and full-length TNFR2 as controls. We showed that FKC binds to full-length TNFR1 and ECD, but not TNFR1 PLAD and CD nor TRADD and full-length TNFR2, confirming that FKC is binding to the region around TNFR1 CRD2-4 (Fig. 4F). Isolating the transmembrane domain and different CRDs other than the PLAD has not been shown and the proteins may not be stable. There is a large number of cysteine–cysteine interaction present in the CRDs which, if disrupted, may induce misfolding and aggregation of the receptor fragments which is not desirable (44). Hence, while our computational study illustrated the binding site of FKC to be at CRD2/3, there is a possibility that it might also be interacting with CRD4 or the transmembrane domain of TNFR1.

FKC Acts on TNFR1 Allosterically by Altering Receptor Conformational States without Blocking Ligand Binding or Disrupting Receptor–receptor Interaction.

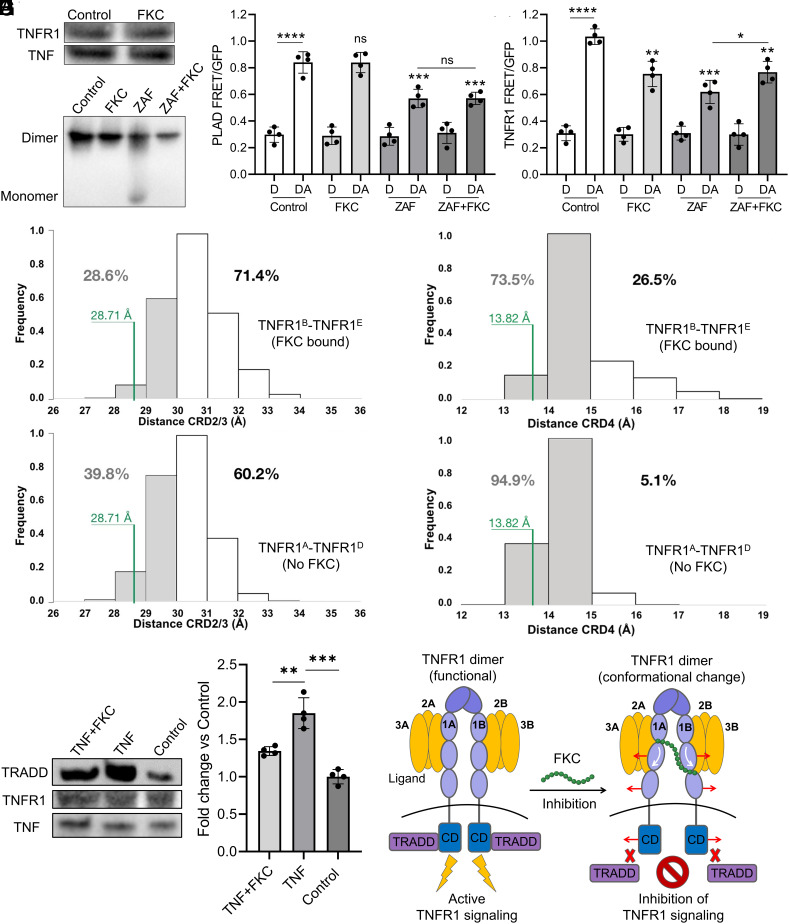

To elucidate the inhibitory mechanism of FKC, we determined whether the receptor conformational change induced by FKC as well as the associated TNFR1 FRET change observed affects receptor–ligand interaction or receptor–receptor interaction. First, co-IP of TNFR1 and TNF showed the same amount of receptor pulled down in the absence and presence of FKC (50 µM), indicating that FKC did not block receptor–ligand interaction, despite binding around the LBD (Fig. 5A). An anti-TNF (etanercept) was used as a positive control in disrupting receptor–ligand interaction (SI Appendix, Fig. S11A). We also observed that FKC did not abolish ligand–ligand interaction through native gel characterization of purified TNF ligand treated with FKC (50 µM) (SI Appendix, Fig. S11B). We then examined whether FKC disrupts receptor–receptor interaction in purified TNFR1 ECD proteins. We found that the small molecule, zafirlukast (ZAF), but not FKC, disrupted TNFR1 ECD–ECD interaction or receptor dimerization (Fig. 5B) as reported in our previous study (17, 34). Interestingly, co-treatment of FKC (50 µM) prevented ZAF from disrupting TNFR1 ECD–ECD interaction (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

FKC alters TNFR1 conformational states without blocking ligand binding or disrupting receptor–receptor interaction. (A) Coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) characterization between TNFR1 and TNF to determine whether FKC (50 µM) affects receptor–ligand interaction. (B) Native gel characterization of purified recombinant TNFR1 ECD in the presence of FKC (50 µM), zafirlukast (ZAF, 100 µM) or cotreatment of ZAF+FKC to test their effects in disrupting ECD–ECD or receptor–receptor interaction. (C) Treatment of FKC (50 µM), ZAF (100 µM), or cotreatment of ZAF+FKC to the PLAD FRET biosensor to test their effects in disrupting PLAD–PLAD interaction. (D) Treatment of FKC (50 µM), ZAF (100 µM), or cotreatment (ZAF+FKC) to the TNFR1 FRET biosensor to test whether FKC affects the FRET reduction induced by ZAF. (E and F) Distance distribution between the (E) CRD2/3 domains (CRD2/3–CRD2/3 distance) and (F) CRD4 domain (CRD4–CRD4 distance) of both receptor monomers is plotted for the TNFRB–TNFR1E dimer with FKC bound (Top panel) and TNFRA–TNFR1D dimer without FKC (Bottom panel). The numbers at each plot indicate the percentage of time that each system explores either distances smaller or greater than 30 Å in (E) or 15 Å in (F). The CRD2/3–CRD2/3 and CRD4–CRD4 distances from the original X-ray structure of the TNFR1 dimer (PDB:1NCF) is indicated in green. (G) Co-IP characterization and quantification between TRADD, TNFR1, and TNF for samples with and without treatment of FKC (50 µM) in the presence of TNF and a no ligand control. The equal amount of His-tagged TNF on the coated beads and endogenous TNFR1 are shown as pull-down controls. (H) The allosteric inhibition mechanism of FKC operates by binding to TNFR1 and perturbing receptor conformational dynamics without affecting receptor–ligand and receptor–receptor interactions. FKC-bound receptor dimer adopts an open and inactive conformation that is unable to recruit downstream signaling molecules, resulting in nonfunctional receptor-ligand complexes that are incapable of signaling. Data are means ± SD of N = 4 independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 and ns indicates nonsignificance by unpaired Student’s t test for comparison between two samples and one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons.

FKC could be increasing the interaction of the two receptor monomers through either directly acting on the PLAD or stabilizing the receptor dimer to hold the individual monomers together. It is unlikely that they act on the PLAD as our co-IP results showed that FKC does not interact with TNFR1 PLAD (Fig. 4F). We further tested the effect of FKC in a PLAD FRET biosensor which only contains the TNFR1 PLAD and is specifically designed to test the effect of modulators in modulating PLAD–PLAD interaction (SI Appendix, Fig. S11C). Overexpression of PLAD FRET pair in HEK293 cells resulted in efficient FRET observed (Fig. 5C). FKC did not reduce FRET of the PLAD biosensor (Fig. 5C and SI Appendix, Fig. S11D), confirming that it did not bind and interfere with PLAD–PLAD interaction. A positive control of ZAF reduced FRET in the PLAD biosensor and co-treatment with FKC (50 µM) did not affect the FRET reduction induced by ZAF (Fig. 5C). This indicates that FKC is not acting on the PLAD and hence unable to prevent ZAF from disrupting PLAD–PLAD interaction.

To test whether FKC is holding the individual receptor monomers together to prevent ZAF from disrupting ECD–ECD interaction or dissociating the dimers, we tested the effect of ZAF and co-treatment of ZAF and FKC in the TNFR1 FRET biosensor. Treatment of ZAF, which is known to disrupt receptor–receptor interaction (17, 34), reduced the TNFR1 FRET signal to a larger extent than FKC, probably due to the fact that it was dissociating the dimers (Fig. 5D). Importantly, co-treatment of ZAF and FKC (50 µM) decreased the extent of FRET reduction induced by ZAF to a level similar to the FRET alteration induced by FKC alone (Fig. 5D). This suggests that FKC, which binds at the interface of two TNFR1 monomers in a preligand dimer pair, is able to hold the individual receptor monomers together and prevent ZAF from dissociating them. Hence, these data indicated that FKC is acting through perturbing receptor conformational dynamics to inhibit TNFR1 signaling, which is consistent with our MD simulation results.

To further confirm that FKC is indeed acting on TNFR1 through altering receptor conformational dynamics, we measured the CRD2/3–CRD2/3 and CRD4–CRD4 distance distributions from our MD simulation data in the FKC bound TNFR1 dimer and compared it to the system in the absence of the FKC. To measure the CRD2/3–CRD2/3 and CRD4–CRD4 distances in the TNFR1 dimer, we took the distance of the center of mass of the backbone atoms from the CRD2/3 (C70 to N116) (SI Appendix, Fig. S12A) and CDR4 (C117 to S159) (SI Appendix, Fig. S12B) domains between TNFR1B–TNFR1E dimer with FKC bound and the equivalent distance between TNFR1A–TNFR1D dimer without FKC binding. The distance distributions indicated that the TNFR1B–TNFR1E dimer with FKC bound explored CRD2/3–CRD2/3 distance with >30 Å at 71.4% of the time (Fig. 5 E, Top) and CRD4–CRD4 distance with >15 Å at 26.5% of the time (Fig. 5 F, Top). This was at a higher frequency relative to the TNFR1A–TNFR1D dimer without FKC binding where CRD2/3–CRD2/3 distance of >30 Å occurred at 60.2% of the time (Fig. 5 E, Bottom) and CRD4–CRD4 distance of >15 Å occurred only at 5.1% of the time (Fig. 5 F, Bottom). We also observed that FKC disrupted the double glutamine interaction between the two receptor monomer chains, namely Q130B–Q133E and Q133B–Q130E (SI Appendix, Fig. S12A), that were originally present in the preligand dimer without FKC binding and this potentially leads to the opening of the receptor dimer. These data suggested that the conformational change induced by FKC led to an increased frequency in the opening of the CRD2/3 and CRD4 of the TNFR1 ECD dimer.

To explain how an alteration in the TNFR1 conformational states could dictate receptor function, we hypothesized that receptor conformational states may determine its accessibility to the downstream signaling machinery, including the recruitment of the downstream signaling molecules such as TRADD. To test this, we performed another co-IP experiment to determine the interactions between TNFR1 and TRADD under ligand stimulation in the absence and presence of FKC in HEK293 cells. Importantly, we found that significantly more TRADD is pulled down with TNF stimulation and FKC (50 µM) significantly reduced the amount of TRADD pulled down under TNF stimulated condition, suggesting that FKC operates by inducing a conformational opening of TNFR1 which impedes the recruitment of TRADD (Fig. 5G).

Together, our results demonstrated that FKC inhibits TNFR1 signaling by allosterically altering receptor conformational states, including increasing the frequency in the opening of the CRD2/3 and CRD4, as well as inducing a conformational opening in the cytosolic regions of the receptor. Importantly, FKC exerts its inhibitory effect on TNFR1 without blocking ligand binding or disrupting receptor–receptor interaction, but through impeding the recruitment of receptor downstream signaling molecules (Fig. 5H). This makes FKC a truly allosteric or noncompetitive inhibitor of TNFR1.

Discussion

Due to the adverse consequences observed from anti-TNF (5, 6), other therapeutics that target the ligands, either through sequestration of free ligands or abolishing ligand–ligand interaction, may suffer similar limitations unless they can specifically reduce interaction with TNFR1 without affecting their binding to TNFR2 (7, 8). To overcome these limitations, there is a paradigm shift in therapeutic strategies from targeting the ligand to developing receptor-specific inhibitors of TNFR1. Currently available receptor-specific inhibitors are mainly antibodies (45, 46), small molecules (47, 48), and peptides or peptidomimetics (22, 49–51) that competitively block receptor–ligand interaction. Unlike small molecules that typically bind TNFR1 to block ligand binding, peptidomimetics are engineered from the specific residues in the ligand binding loop to bind to TNF and prevent their binding to TNFR1 without affecting their binding to TNFR2. Specifically, peptides such as WP9QY (22, 49) and a cyclic peptide (50) were engineered from TNFR1 and protected cells against TNF-induced cell death with an IC50 between 75 and 130 µM. In contrast to these peptides derived from receptor domain to target the ligand, FKC is targeting the inner region of the receptor dimer itself around the conformationally active region (residues 100 to 117) and does not abolish ligand binding. Importantly, the IC50 of FKC is 25 µM which is twofold to fivefold more effective than these ligand-targeting peptides. Due to the strong binding affinity between TNF and TNFR1, which is in the subnanomolar range (18), therapeutics that work by competitively blocking receptor–ligand interaction have a very steep hill to climb. This is supported by the lack of potency in small molecules that bind TNFR1 to block ligand binding including R1 which has a potency of >50 µM (47).

Another receptor-specific targeting strategy is to disrupt TNF receptor preligand assembled dimer (34, 52, 53), which is a functional subunit required to mediate receptor signaling upon ligand binding (12, 13), by abolishing the PLAD–PLAD interaction or receptor–receptor interaction. Examples include peptides or peptidomimetics such as the purified soluble TNFR1 PLAD (54) and Pep4-19 (55) that are engineered to specifically map TNFR1 PLAD as well as a small molecule (ZAF) that was identified in our previous study (17, 34, 37), all of which have been shown to disrupt receptor–receptor interaction and inhibit TNFR1 signaling. The advantage of this targeting strategy is that the affinity between receptor monomers is in low micromolar range, which is weaker than the receptor–ligand binding affinity (56). However, both ZAF and Pep4-19 only exhibited partial inhibition which could potentially be due to the PLAD–PLAD interaction having a higher affinity and the preservation of the ligand-bound trimeric structure (noninteracting receptor monomers stabilized by ligand binding) that might still be functional, albeit to a less extent (57). For the purified soluble TNFR1 PLAD, it is unclear whether the effect of inhibition can solely be attributed to disruption of the receptor dimer as it has been reported to block ligand binding (54).

In terms of targeting TNFR1 conformational dynamics, both FKC and DS42 act through the conformationally active region of TNFR1 (13, 17) in an allosteric or noncompetitive manner; however, FKC (IC50 = 25 µM) has a higher potency than DS42 (IC50 = 50 µM) (17). This may be explained in part by the difference in their mechanisms of action where FKC acts directly on the conformationally active region to alter the conformational states, while DS42 targets the PLAD to induce a long-range perturbation of receptor conformational dynamics. This is supported by the notion that more energy is required to enable the long-range receptor perturbation as compared to local perturbation near the binding sites (58). It is important to note that the conformational changes at CRD2/3 and CRD4 of TNFR1 ECD dimer and the separation of the cytosolic regions of the receptor induced by FKC are supported by examples illustrating how subtle conformational changes are amplified to distant regions (59, 60). For instance, small conformational changes induced by agonist binding at the extracellular LBD of various G protein-coupled receptors increase the probability for the receptor to undergo drastic changes at the intracellular region (59, 60).

In terms of therapeutic optimization, the long-range receptor perturbation induced by DS42 may make it difficult to optimize the potency of the compound because the optimization process should not focus solely on the local pharmacophore near the PLAD but also need to take into account how exactly TNFR1 propagates signals from the membrane distal domain to the membrane-proximal domain to induce conformational changes, which is currently unclear. In contrast, the optimization of FKC would be more straightforward and can be achieved by changing amino acid groups or peptide length (61) based on the well-defined local pharmacophore and the type of interactions with individual TNFR1 monomers for better targeting efficacies, bioavailability, and pharmacological properties. Machine learning classification and regression analysis or AI are some strategies that can be adopted for peptide optimization (62, 63). Being a short peptide suitable for therapeutic application (64), FKC is a promising lead candidate to move forward in the drug discovery pipeline. Thus, this study strengthens the feasibility of targeting the conformationally active region of TNF receptors and presents a functionally relevant interacting loci where therapeutics can bind to modulate receptor functions. Future studies that can be carried out include screening of peptide-based libraries using FRET biosensors of the different TNF receptor superfamily members (53, 65). This will enable systematic discovery of new therapeutics targeting similar interacting loci and potentially exploring the effect of targeting the conformationally active region of other TNF receptor superfamily members.

Both the current and several previous studies have suggested that TNF receptor conformational states behave as a molecular switch, where different extents of opening of the receptor membrane proximal region can result in either inhibition or further activation of signaling (17, 35, 36, 66). The different extent of conformational changes in terms of receptor openings may lead to the receptor–ligand signaling complexes and the functional network adopting different arrangements on the cell membrane. This implicates the spatial orientation of the receptor cytosolic domain that is crucial for the recruitment of the downstream signaling molecules and ultimately transduces different signals (67). The exact switching mechanism to impart activation or inhibition remains to be investigated and this knowledge would hold the key to understanding how to best modulate the signaling of TNFR1 and other TNF receptor superfamily members in general (65, 68). Current limitations include difficulty in performing accurate measurements of alterations in the spatial orientation and changes in the distance between the different domains of TNFR1 caused by allosteric modulators. High-resolution techniques such as X-ray crystallography or cryo-electron microscopy are required to provide more detailed and accurate structural information. To further solidify and deepen our understanding of the conformationally active region of the TNFR1 for future drug discovery effort, there is a need to obtain crystal structure of the receptor–ligand signaling complex with conformational changes in TNFR1 dimer induced by allosteric or noncompetitive inhibitors.

Materials and Methods

Peptides Synthesis.

FKC (FKCRRWQWRMKK-NH2), rhodamine-conjugated FKC (Rho-FKCRRWQWRMKK-NH2), and IDR (VQRWLIVWRIRK-NH2) peptides were synthesized using solid phase F-moc chemistry by CPC Scientific, Inc. with a purity greater than 95%. The FKC structure was modified with the addition of an amine group to convert the COOH terminal to an amide. This is to protect FKC from proteolysis carried out by carboxypeptidases which confers improved stability and increases the half-time of the peptide inside cells and animals. Dynamic light scattering was conducted to measure whether the peptide forms aggregation at high concentrations using Brookhaven 90Plus Particle Size Analyzer.

Cell Culture.

The human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells (ATCC, Cat# CRL-1573) were cultured in phenol red–free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium with glutamine and sodium pyruvate (DMEM, Gibco Cat# 11965-092) supplemented with heat-inactivated 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS HI, Gibco Cat# A5256701) as well as penicillin-streptomycin (10,000 U/mL) (Thermofisher Scientific, Cat# 15140122). Cell cultures were maintained in an incubator with 5% CO2 at 37 °C (Nuaire NU-5831E CO2 Incubator). The TNFR1 KO HEK293 cell line (Ubigene, Cat# YKO-HS1133) was generated by CRISPR-U technology (CRISPR based) using small fragment KO strategy removing exon 2, 3, 4, and 5 in the target coding region of TNFRSF1A and cultured as described above.

Animal Studies.

We used both male and female C57BL/6J mice that are 8 wk old for the treatment procedures. The mice were housed in a temperature-controlled room (25 °C) in virus-free facilities on a 12 h light/dark cycle (7:30 a.m. on/7:30 p.m. off) and water ad libitum. All mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions and treated with humane care. All procedures were conducted with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) animal use protocol A22058 from Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. In each animal experiment, mice were randomly allocated to receive intraperitoneal injections containing either saline, mouse TNF (MedChemExpress, Cat# HY-P7090), or FKC with and without rhodamine conjugation at a total volume of 200 µL per injection. FKC was injected at 20 or 40 mg/kg in all mice and mouse TNF was used at 250 µg/kg following previously published protocol (43). For the treatment groups, mice (N = 12 per group, six male and six female) were first intraperitoneally injected with the first dose of either saline or FKC for 24 h, followed by subsequent intraperitoneal injection of a second dose of saline as negative control or mouse TNF for 4 h to induce peripheral inflammation. Mice were killed by euthanasia with CO2 according to the approved procedure by the IACUC of NTU Singapore and a blood sample from each mouse was collected via cardiac puncture into a BD Vacutainer Serum Tubes (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 12396929). Mouse tissues from the liver, kidneys, and lungs were also collected for subsequent analysis.

Western Blotting.

HEK293 cells cultured in six-well plates (Merck, Cat# CLS3506) at 0.5 million cells/well were treated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# D8537) as a negative control and respective doses of FKC (5 to 50 µM) for 2 h, followed by 30 min of human TNF (50 ng/mL) (MedChemExpress, Cat# HY-P7416) treatment at 37 °C. Both the cells and mouse tissues were lysed and homogenized, respectively, using radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 89900) containing 1% Halt Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (100X) (Thermofisher Scientific, Cat# 78440), followed by running in precast protein gels and conducting standard Western blotting procedures. More details of the Western blotting procedures are in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

NF-κB Activation Assays.

Both TNFR1 WT and TNFR1 KO HEK293 cells were transfected in six-well plates with the dual luciferase reporters containing NF-κB response elements at 1 μg of Firefly luciferase reporter gene (Promega, Cat# E8491) and 0.1 μg of Renilla luciferase reporter gene (Promega, Cat# E6931) using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, Cat# L3000015). After 24 h of incubation, the transfected cells were dispensed into 96-well (15,000 cells/well) white, solid-bottom plates (Greiner Bio-One North America, Cat# 655076) and incubated with PBS (negative control) or FKC (5 to 50 µM) in the presence (50 ng/mL) and absence of TNF and IL-1β (MedChemExpress, Cat# HY-P7028) for 18 h at 37 °C. Following incubation, a solution of 50 µL of Dual-Glo Luciferase Reagent (Promega, Cat# E2920) was added and kept at room temperature for 15 min. The Firefly luminescence was measured using a BioTek Synergy H1 Microplate Reader. Subsequently, 50 µL of Dual-Glo Stop & Glo Reagent (Promega, Cat# E2920) was added and kept at room temperature for 15 min, and Renilla luminescence was measured using a luminometer. For TRADD induced NF-κB activation in HEK293 cells, 1 μg of TRADD plasmid or control plasmid was cotransfected with the NF-κB dual luciferase reporter genes followed by the same procedure as described above. The Firefly luciferase activities were normalized to the Renilla levels, and all data from NF-κB activation assays were normalized to luciferase activity of cells with ligand treatment or TRADD overexpression.

Tissue Immunostaining and Image Acquisition.

Mouse livers, kidneys, and lungs were first fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS solution (VWR, Cat# ALFAJ61899.AK) for 24 h, followed by overnight fixation in 30% sucrose solution (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# S0389). The samples were then embedded in Tissue-Tek O.C.T compound (Sakura Finetek USA, Cat# 4583), using disposable base molds measuring 15 × 15 mm (Epredia, Cat# 58950) and cut into 20-μm-thick frozen sections using a cryostat (Leica, Cat# CM1950) and placed on Superfrost Plus Adhesion Microscopic glass slides (Epredia, Cat# J1800AMNZ). The frozen sections were blocked with 5% normal goat serum (NGS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 31872) for 1 h at room temperature. Subsequently, the sections were incubated with primary and secondary antibodies before the fluorescent images were acquired using a slide scanner. More details of tissue immunostaining and image acquisition are in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Construction of the TNFR1/TNF Complex System and Peptide–protein Blind Docking.

A detailed physiologically relevant model of a proposed functional form of the TNFR1 receptor bound to TNF was built as follows. The structure of the three TNFR1 dimers (TNFR1A–TNFR1D, TNFR1B–TNFR1E, and TNFR1C–TNFR1F) bound to a TNF trimer (TNFX–TNFY–TNFZ) with a threefold symmetry was constructed using the available X-ray crystallography information (PDB:7KP7) (9). The structure of the TNFR1 preligand dimer was obtained from the available crystallographic information (PDB:1NCF) (11). To identify possible molecular poses of FKC in the TNFR1/TNF system, we utilized the HPEPDOCK 2.0 server which enables flexible peptide–protein docking by fast modeling of peptide conformations and global/local sampling of binding orientations (69). To reduce the processing time, only a dimeric structure (e.g., the TNFR1B–TNFR1E chains) of the TNFR1 system was utilized. Using the suggested default parameters, the program generated 10 different molecular poses for FKC. Docking of bovine lactoferricin (PDB:1LFC) (70), which is a segment of bovine lactoferrin (PDB:1BLF) (71) on TNFR1 was performed using the same method. The amino acids sequences of FKC and bovine lactoferricin correspond to residues 36 to 47 and residues 36 to 60 of the bovine lactoferrin structure.

All-atom MD Simulations.

Selected molecular poses obtained from the peptide–protein docking protocol were evaluated with all-atom MD simulations. The atomistic MD simulations were performed with the NAMD software using the CHARMM36 force field. The protein system was simulated at a temperature and pressure of 37 °C and 1 atm, respectively, and at a salt concentration of 0.15 M of NaCl. The entire systems are composed of approximately 215,000 atoms. The length of bond involving hydrogen atom were constraint to their equilibrium values using the SHAKE algorithm. The unbiased MD simulations were carried out using a 2.0 fs time step and the entire simulations consist of 250 ns. More details of the computational simulations conducted have been described in our previous studies (72, 73).

FRET Assays.

The FRET biosensors were generated by transient transfection of HEK293 cells in 6-well plate with the respective donor-only and donor/acceptor FRET pair DNAs using Lipofectamine 3000. More details of molecular biology of plasmids generation are in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods. After the transfection, cells were transferred into 96-well plates (15,000 cells/well) followed by treatment with PBS (negative control), FKC (5 to 50 µM), or zafirlukast (ZAF, MedChemExpress, Cat# HY17491) for another 24 h followed by fluorescence intensity measurement. FRET measurements were performed following the protocols in previous studies (74, 75). More details of FRET assays are in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Co-immunoprecipitation Pull-down Assays.

To perform co-immunoprecipitation, Ni-NTA His-Tag Purification Agarose beads (MedChemExpress, Cat# HY-K0210) were first mixed with His-tagged human TNF or His-tagged FKC and incubated for 4 h at 4 °C and the unbound His-tagged TNF or His-tagged FKC was then removed by washing the beads with PBS. His-tagged TNF was used to probe for receptor–ligand and TNFR1–TRADD interactions by pulling down the receptor. His-tagged FKC was used to probe for the interactions between FKC and full-length TNFR1, different TNFR1 domains, TRADD, or TNFR2. Immunoprecipitated samples were resolved using standard Western blotting procedures. More details of coimmunoprecipitation pull-down assays are in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad Prism 9 software. Statistical analysis was conducted by using unpaired Student’s t test for difference between two conditions and one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. Statistical significance was determined by P < 0.05 and indicated by *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 or ns for nonsignificance.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

The time evolution of FKC along the 250 ns long MD simulation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the following funding sources. C.H.L. was supported by a Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine Dean’s Postdoctoral Fellowship (Grant Award Number 021207-00001) from Nanyang Technological University (NTU) Singapore, an Early-Career Pilot Grant (INTRO-ECR) from the NISTH, NTU Singapore, and a Mistletoe Research Fellowship (Grant Award Number 022522-00001) from the Momental Foundation USA. J.Z. was supported by a Presidential Postdoctoral Fellowship (Grant Award Number 021229-00001) from NTU Singapore. V.M.B.-A. acknowledges the Coordination of Scientific Research from Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo (Science Program 2022) and the Institute for Science Technology and Innovation (Grant Award Number PICIR-004-2022-2023) of the Michoacán State Government. J.M.P.-A. acknowledges the computing time granted by the LANCAD on the supercomputer xiuhcoatl at CGSTIC CINVESTAV, members of the CONACyT network of national laboratories. J.M.P.-A. thanks the Laboratorio Nacional de Supercómputo del Sureste de México (LNS-BUAP) of the CONACyT network of national laboratories for the computer resources and support provided. J.M.P.-A. also acknowledges the Vicerrectoría de Investigación y Estudios de Posgrado (VIEP-BUAP, Mexico) (VIEP2023 project), and the PRODEP Academic Group BUAP-CA-263 (SEP, Mexico).

Author contributions

V.M.B.-A. and C.H.L. designed research; J.Z., G.W.Z.L., E.N.S., M.A.R.D., O.S.-G., J.M.P.-A., V.M.B.-A., and C.H.L. performed research; J.Z., G.W.Z.L., E.N.S., J.M.P.-A., V.M.B.-A., and C.H.L. analyzed data; and J.Z., J.M.P.-A., V.M.B.-A., and C.H.L. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

C.H.L., J.Z., J.M.P.-A., and V.M.B.-A. are co-inventors on a provisional patent application filed with the Intellectual Property Office of Singapore (Application Number: 10202400831U) on the development of peptide-based therapeutics with anti-inflammatory properties. The remaining authors declare no other competing interests.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Contributor Information

Víctor M. Baizabal-Aguirre, Email: victor.baizabal@umich.mx.

Chih Hung Lo, Email: chihhung.lo@ntu.edu.sg.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or supporting information.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Locksley R. M., Killeen N., Lenardo M. J., The TNF and TNF receptor superfamilies: Integrating mammalian biology. Cell 104, 487–501 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wajant H., Scheurich P., TNFR1-induced activation of the classical NF-κB pathway. FEBS J. 278, 862–876 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brenner D., Blaser H., Mak T. W., Regulation of tumour necrosis factor signalling: Live or let die. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 362–374 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asimakidou E., Reynolds R., Barron A. M., Lo C. H., Autolysosomal acidification impairment as a mediator for TNFR1 induced neuronal necroptosis in Alzheimer’s disease. Neural. Regen. Res. 19, 1869–1870 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li J., et al. , Risk of adverse events after anti-TNF treatment for inflammatory rheumatological disease. A meta-analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 746396 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalliolias G. D., Ivashkiv L. B., TNF biology, pathogenic mechanisms and emerging therapeutic strategies. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 12, 49–62 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fischer R., Kontermann R. E., Pfizenmaier K., Selective targeting of TNF receptors as a novel therapeutic approach. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 8, 401 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang N., Wang Z., Zhao Y., Selective inhibition of Tumor necrosis factor receptor-1 (TNFR1) for the treatment of autoimmune diseases. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 55, 80–85 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McMillan D., et al. , Structural insights into the disruption of TNF-TNFR1 signalling by small molecules stabilising a distorted TNF. Nat. Commun. 12, 582 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banner D. W., et al. , Crystal structure of the soluble human 55 kd TNF receptor-human TNF beta complex: Implications for TNF receptor activation. Cell 73, 431–445 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naismith J. H., Devine T. Q., Brandhuber B. J., Sprang S. R., Crystallographic evidence for dimerization of unliganded tumor necrosis factor receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 13303–13307 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan F.K.-M., et al. , A domain in TNF receptors that mediates ligand-independent receptor assembly and signaling. Science 288, 2351–2354 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis A. K., Valley C. C., Sachs J. N., TNFR1 signaling is associated with backbone conformational changes of receptor dimers consistent with overactivation in the R92Q TRAPS mutant. Biochemistry 51, 6545–6555 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan F. K., Three is better than one: Pre-ligand receptor assembly in the regulation of TNF receptor signaling. Cytokine 37, 101–107 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valley C. C., et al. , Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) induces death receptor 5 networks that are highly organized. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 21265–21278 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valley C. C., Lewis A. K., Sachs J. N., Piecing it together: Unraveling the elusive structure-function relationship in single-pass membrane receptors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1859, 1398–1416 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lo C. H., et al. , Noncompetitive inhibitors of TNFR1 probe conformational activation states. Sci. Signal 12, eaav5637 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murali R., et al. , Disabling TNF receptor signaling by induced conformational perturbation of tryptophan-107. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 10970–10975 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wootten D., Christopoulos A., Sexton P. M., Emerging paradigms in GPCR allostery: Implications for drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 12, 630–644 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wells J. A., McClendon C. L., Reaching for high-hanging fruit in drug discovery at protein–protein interfaces. Nature 450, 1001–1009 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schön A., Lam S. Y., Freire E., Thermodynamics-based drug design: Strategies for inhibiting protein-protein interactions. Future Med. Chem. 3, 1129–1137 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murali R., Zhang H., Cai Z., Lam L., Greene M., Rational design of constrained peptides as protein interface inhibitors. Antibodies 10, 32 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farooq Z., Howell L. A., McCormick P. J., Probing GPCR dimerization using peptides. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 13, 843770 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quiniou C., et al. , Specific targeting of the IL-23 receptor, using a novel small peptide noncompetitive antagonist, decreases the inflammatory response. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. 307, R1216–R1230 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohradanova-Repic A., et al. , Time to kill and time to heal: The multifaceted role of lactoferrin and lactoferricin in host defense. Pharmaceutics 15, 1056 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu D., Fu L., Wen W., Dong N., The dual antimicrobial and immunomodulatory roles of host defense peptides and their applications in animal production. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 13, 141 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han F., et al. , Bovine lactoferricin ameliorates intestinal inflammation and mucosal barrier lesions in colitis through NF-κB/NLRP3 signaling pathways. J. Funct. Foods 93, 105090 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bolouri H., et al. , Innate defense regulator peptide 1018 protects against perinatal brain injury. Ann. Neurol. 75, 395–410 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coccolini C., et al. , Biomedical and nutritional applications of lactoferrin. Int. J. Pept. Res. 29, 71 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huante-Mendoza A., Silva-García O., Oviedo-Boyso J., Hancock R. E., Baizabal-Aguirre V. M., Peptide IDR-1002 inhibits NF-κB nuclear translocation by inhibition of IκBα degradation and activates p38/ERK1/2-MSK1-dependent CREB phosphorylation in macrophages stimulated with lipopolysaccharide. Front. Immunol. 7, 533 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Inubushi T., et al. , Molecular mechanisms of the inhibitory effects of bovine lactoferrin on lipopolysaccharide-mediated osteoclastogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 23527–23536 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okubo K., et al. , Precision engineered peptide targeting leukocyte extracellular traps mitigate acute kidney injury in Crush syndrome. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 671, 173–182 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yan D., et al. , Bovine lactoferricin is anti-inflammatory and anti-catabolic in human articular cartilage and synovium. J. Cell Physiol. 228, 447–456 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lo C. H., et al. , An innovative high-throughput screening approach for discovery of small molecules that inhibit TNF Receptors. SLAS Discov. 22, 950–961 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lo C. H., Huber E. C., Sachs J. N., Conformational states of TNFR1 as a molecular switch for receptor function. Protein Sci. 29, 1401–1415 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lo C. H., Schaaf T. M., Thomas D. D., Sachs J. N., “Fluorescence-based TNFR1 biosensor for monitoring receptor structural and conformational dynamics and discovery of small molecule modulators” in The TNF Superfamily: Methods and Protocols, Bayry J., Ed. (Springer, US, New York, NY, 2021), 2248, 121–137 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vunnam N., et al. , Zafirlukast is a promising scaffold for selectively inhibiting TNFR1 signaling. ACS Bio. Med. Chem. Au. 3, 270–282 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ozsoy H. Z., Sivasubramanian N., Wieder E. D., Pedersen S., Mann D. L., Oxidative stress promotes ligand-independent and enhanced ligand-dependent tumor necrosis factor receptor signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 23419–23428 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gifford J. L., Hunter H. N., Vogel H. J., Lactoferricin: A lactoferrin-derived peptide with antimicrobial, antiviral, antitumor and immunological properties. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 62, 2588–2598 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mamińska A., et al. , ESCRT proteins restrict constitutive NF-κB signaling by trafficking cytokine receptors. Sci. Signal 9, ra8 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hsu H., Xiong J., Goeddel D. V., The TNF receptor 1-associated protein TRADD signals cell death and NF-kappa B activation. Cell 81, 495–504 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin H., et al. , MARCH3 attenuates IL-1β-triggered inflammation by mediating K48-linked polyubiquitination and degradation of IL-1RI. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 12483–12488 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Biesmans S., et al. , Peripheral administration of tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces neuroinflammation and sickness but not depressive-like behavior in mice. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 716920 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kimberley F. C., Lobito A. A., Siegel R. M., Screaton G. R., Falling into TRAPS–receptor misfolding in the TNF receptor 1-associated periodic fever syndrome. Arthritis Res. Ther. 9, 217 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Steeland S., et al. , Generation and characterization of small single domain antibodies inhibiting human tumor necrosis factor receptor 1. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 4022–4037 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vunnam N., et al. , Discovery of a non-competitive TNFR1 antagonist affibody with picomolar monovalent potency that does not affect TNFR2 function. Mol. Pharmaceutics 20, 1884–1897 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen S., et al. , Discovery of novel ligands for TNF-α and TNF receptor-1 through structure-based virtual screening and biological assay. J. Chem. Inf. Model 57, 1101–1111 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saddala M. S., Huang H., Identification of novel inhibitors for TNFα, TNFR1 and TNFα-TNFR1 complex using pharmacophore-based approaches. J. Transl. Med. 17, 215 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Takasaki W., Kajino Y., Kajino K., Murali R., Greene M. I., Structure-based design and characterization of exocyclic peptidomimetics that inhibit TNF alpha binding to its receptor. Nat. Biotechnol. 15, 1266–1270 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Idress M., et al. , Structure-based design, synthesis and bioactivity of a new anti-TNFα cyclopeptide. Molecules 25, 922 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mukaro V. R., et al. , Small tumor necrosis factor receptor biologics inhibit the tumor necrosis factor-p38 signalling axis and inflammation. Nat. Commun. 9, 1365 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Francis Ka-Ming C., The pre-ligand binding assembly domain: A potential target of inhibition of tumour necrosis factor receptor function. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 59, i50 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vunnam N., Lo C. H., Grant B. D., Thomas D. D., Sachs J. N., Soluble extracellular domain of death receptor 5 inhibits TRAIL-induced apoptosis by disrupting receptor-receptor interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 429, 2943–2953 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Deng G. M., Zheng L., Chan F. K., Lenardo M., Amelioration of inflammatory arthritis by targeting the pre-ligand assembly domain of tumor necrosis factor receptors. Nat. Med. 11, 1066–1072 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang X., et al. , Dual-targeting inhibition of TNFR1 for alleviating rheumatoid arthritis by a novel composite nucleic acid nanodrug. Int. J. Pharm. X 5, 100162 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cao J., Meng F., Gao X., Dong H., Yao W., Expression and purification of a natural N-terminal pre-ligand assembly domain of tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (TNFR1 PLAD) and preliminary activity determination. Protein J. 30, 281–289 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vanamee É. S., Faustman D. L., Structural principles of tumor necrosis factor superfamily signaling. Sci. Signal. 11, eaao4910 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yu E. W., Koshland D. E., Propagating conformational changes over long (and short) distances in proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 9517–9520 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gregorio G. G., et al. , Single-molecule analysis of ligand efficacy in β(2)AR-G-protein activation. Nature 547, 68–73 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhou Q., et al. , Common activation mechanism of class A GPCRs. ELife 8, e50279 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang X., Ni D., Liu Y., Lu S., Rational design of peptide-based inhibitors disrupting protein-protein interactions. Front. Chem. 9, 682675 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jenson J. M., et al. , Peptide design by optimization on a data-parameterized protein interaction landscape. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E10342–E10351 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huang J., et al. , Identification of potent antimicrobial peptides via a machine-learning pipeline that mines the entire space of peptide sequences. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 7, 797–810 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang L., et al. , Therapeutic peptides: Current applications and future directions. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 7, 48 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vunnam N., et al. , Noncompetitive allosteric antagonism of death receptor 5 by a synthetic affibody ligand. Biochemistry 59, 3856–3868 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vunnam N., Campbell-Bezat C. K., Lewis A. K., Sachs J. N., Death receptor 5 activation is energetically coupled to opening of the transmembrane domain dimer. Biophys. J. 113, 381–392 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bethani I., Skånland S. S., Dikic I., Acker-Palmer A., Spatial organization of transmembrane receptor signalling. EMBO J. 29, 2677–2688 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vunnam N., et al. , Nimesulide, a COX-2 inhibitor, sensitizes pancreatic cancer cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis by promoting DR5 clustering. Cancer Biol. Ther. 24, 2176692 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhou P., Jin B., Li H., Huang S. Y., HPEPDOCK: A web server for blind peptide-protein docking based on a hierarchical algorithm. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W443–W450 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hwang P. M., Zhou N., Shan X., Arrowsmith C. H., Vogel H. J., Three-dimensional solution structure of lactoferricin B, an antimicrobial peptide derived from bovine lactoferrin. Biochemistry 37, 4288–4298 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Moore S. A., Anderson B. F., Groom C. R., Haridas M., Baker E. N., Three-dimensional structure of diferric bovine lactoferrin at 2.8 Å resolution11 Edited by D. Rees. J. Mol. Biol. 274, 222–236 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rebolledo-Bustillo M., et al. , Structural basis of the binding mode of the antineoplastic compound motixafortide (BL-8040) in the CXCR4 chemokine receptor. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 4393 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dávila E. M., et al. , Interacting binding insights and conformational consequences of the differential activity of cannabidiol with two endocannabinoid-activated G-protein-coupled receptors. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 945935 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ercan B., Naito T., Koh D. H. Z., Dharmawan D., Saheki Y., Molecular basis of accessible plasma membrane cholesterol recognition by the GRAM domain of GRAMD1b. EMBO J. 40, e106524 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lo C. H., Recent advances in cellular biosensor technology to investigate tau oligomerization. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 6, e10231 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

The time evolution of FKC along the 250 ns long MD simulation.

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or supporting information.