Abstract

This work studies the dynamics of a gene expression time series network. The network, which is obtained from the correlation of gene expressions, exhibits global dynamic properties that emerge after a cell state perturbation. The main features of this network appear to be more robust when compared with those obtained with a network obtained from a linear Markov model. In particular, the network properties strongly depend on the exact time sequence relationships between genes and are destroyed by random temporal data shuffling. We discuss in detail the problem of finding targets of the c-myc protooncogene, which encodes a transcriptional regulator whose inappropriate expression has been correlated with a wide array of malignancies. The data used for network construction are a time series of gene expression, collected by microarray analysis of a rat fibroblast cell line expressing a conditional Myc-estrogen receptor oncoprotein. We show that the correlation-based model can establish a clear relationship between network structure and the cascade of c-myc-activated genes.

Keywords: complex systems, time series, gene interaction

The availability in modern molecular biology of methods capable of measuring the activity of thousands of genes at the same time poses the challenge of analysis and modeling of complex biological networks with thousands of units. Microarray technology is producing data on the activity of significant portions of the genome in a wide variety of cells and organisms up to the level of the entire human genome. Several techniques have been proposed to analyze the high dimensional data resulting from these experiments. Artificial neural networks, phylogenetic-type trees, clustering algorithms, and kernel methods are just a few examples (1–6).

Complex network theory has been used to characterize topological features of many biological systems such as metabolic pathways, protein–protein interactions, and neural networks (7, 8). The application of network theory to gene expression data has been not fully investigated, particularly regarding the time-dependent relationships between genes occurring while their expression level changes.

One of the key points of the network approach is the definition of the links between its elements (nodes), namely, the gene interactions from which all of the network properties are obtained. Recently, several methods for links assessment have been proposed, such as linear Markov model (LMM)-based methods (9, 10) or correlation-based methods (11–13). We choose to define links on the basis of the time correlation properties of gene expression measurements.

In this article, we show that correlation properties of gene expression time series measurements reflect very broad changes in genomic activity. The problem that we address is characterizing the gene transregulation cascade in response to c-Myc protooncogene activation. C-myc encodes a transcriptional regulator whose inappropriate expression is correlated with a wide array of malignancies. At the cellular level c-Myc activity has been linked with cell division, accumulation of mass, differentiation, and programmed cell death. Although the positive influence of c-Myc on proliferation has been appreciated for a long time, the molecular mechanisms by which these end points are achieved are not well understood. It is now clear that Myc can directly influence the expression of thousands of genes with diverse functions. A significant challenge is to integrate this wealth of information into mechanistic models that explain the biological functions of c-Myc. This endeavor has been greatly complicated not only by the large number of targets, but also by the weak transcriptional effects exerted by c-Myc. Thus, the biologically relevant downstream effectors remain to be comprehensively delineated.

The correlation method is more sensitive to the temporal structure of the data than LMM and leads to biologically relevant gene identification that is not obtained by either Markov modeling or significance analysis based only on ANOVA.

Methods

Gene Expression Time Series. Two data sets of gene expression were obtained from a set of microarray experiments using genetically engineered rat cell lines. As described (ref. 14 and references therein), parental Rat-1 fibroblasts were modified by homologous recombination to knock out both copies of the c-myc gene (c-myc–/– cells). This cell line was subsequently reconstituted with a cDNA encoding a fusion protein of c-Myc and the human estrogen receptor (MycER). The fusion protein is synthesized continuously in the cells, but is biologically inactive in the absence of a specific ligand, 4-hydroxy tamoxifen. Binding of tamoxifen to the estrogen receptor domain elicits a conformational change that allows the fusion protein to migrate to the nucleus and act as a transcription factor. A large volume of data from several laboratories indicates that the biological activities of native c-Myc protein and the MycER fusion protein are similar, if not identical. Randomly cycling, exponential-phase cultures were used, and conditions were developed such that cells experienced a constant environment and were in a balanced, steady state of growth for significant periods of time. Two data sets were obtained. The first data set (N data set) contains the gene expression data of the c-myc–/– MycER cell line treated with vehicle (ethanol) only. The second data set (T data set) contains the gene expression data collected after the addition of tamoxifen. Samples were harvested at five time points after the addition of tamoxifen to the culture medium: 1, 2, 4, 8, and 16 h. The entire experiment was repeated on three separate occasions, providing three independent measurements for each gene and each time point. Expression profiling was done by using the Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA) platform and U34A GeneChips (8,799 probe sets; Affymetrix).

Significance Analysis and Data Preprocessing. A two-way full factorial ANOVA was applied to each of the 8,799 probe sets to identify those that significantly changed expression level in time between the two conditions (data set N versus data set T). The significance analysis was based on the general linear model that describes changes in gene expression level γ from the global mean μ as caused by the combination of: changes in treatment (β), i.e., database N versus database T; changes in time (α); interaction between time and treatment (γ); plus some random effects (ε):

|

[1] |

where the index i refers to the data set (N or T); the index j refers to time (j = 1, 2, 4, 8, or 16 h); and the index k refers to the replication of the experiment for a fixed condition and time (k = experiment 1, 2, or 3). Probe sets with a P value corresponding to the β factor <0.05 were considered to be significantly affected by the treatment (i.e., activation of c-myc by tamoxifen). A total of 1,191 genes were selected with this criterion. This subset of selected probes enhances the differences between the N and T networks that we observe, but the results are similar even if considering the whole data set.

The gene expression values used for the analysis were obtained by averaging over the three experiments (yij = 1/3Σkyijk) to reduce the effects of noise in the expression level measurements.

Network Construction: Correlation-Based Model. In the correlation-based model, the similarity measure for the expression dynamics of two genes within the same data set is given by the correlation between the two expression-level time series. Hence, for a given data set, if xlj is the expression level of a gene with label l at time j, then the similarity between two genes with labels l and r, respectively, is given by:

|

[2] |

where μl and μr are the averages in time of the expression levels for the two genes, and σl and σr are their standard deviations. The correlation approach can be motivated by the hypothesis that genes belonging to the same activation (or inhibition) pathway should present a similar (or opposite) expression profile in time. The adjacency matrix characterizing the network was obtained by considering only the clr coefficients whose absolute value exceeded a threshold fixed between 0.95 and 0.99. The results shown in this article were obtained for a threshold equal to 0.98. These coefficients were set equal to 1, producing a symmetric adjacency matrix alr. For each gene a connectivity degree k was defined as the total number of genes it was connected to, i.e., k(l) = Σr≠l alr.

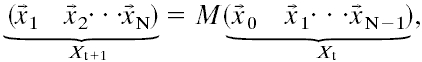

Network Construction: LMM. In the LMM, the expression level of a gene at a given time tj+1 is modeled as a linear combination of the expression levels of all genes at the previous time tj. Because measurements were not performed at equally spaced times, we interpolated the time series by using a spline interpolation to generate a total of n = 17 equally spaced points in time [an alternative procedure would require an optimization technique such as simulated annealing (4)]. The model can be expressed in matrix form as follows:

|

[3] |

where  is a column vector of the expression levels for all genes at time tj (the index i relative to the data set has been dropped for convenience). Because the number of genes is larger than the number of time points, Eq. 3 does not have a unique solution. A common approach is to solve it by using the Moore–Penrose generalized matrix inverse X+t of Xt (a unique pseudoinverse matrix obtained by including additional constrains) via its singular value decomposition (4) such that:

is a column vector of the expression levels for all genes at time tj (the index i relative to the data set has been dropped for convenience). Because the number of genes is larger than the number of time points, Eq. 3 does not have a unique solution. A common approach is to solve it by using the Moore–Penrose generalized matrix inverse X+t of Xt (a unique pseudoinverse matrix obtained by including additional constrains) via its singular value decomposition (4) such that:

|

Because the resulting matrix M is in general not symmetric, we applied a symmetrization procedure by averaging the corresponding off-diagonal coefficients (other symmetrization techniques lead to similar results in terms of network properties). Computation of the adjacency matrix and gene connectivity from the symmetrized M matrix was performed in the same manner as in the correlation-based model, but the threshold was set as the value corresponding to the 95th percentile.

Validation. Time reshuffling was used to test the time sequence dependence of the results obtained by the two techniques. By randomly shuffling the time series for each gene separately, time relationships between expression levels are broken, but the mean and standard deviation for each gene are unaltered. Properties of the gene network that truly depend on the expression level dynamics should be significantly affected by a random shuffling in time.

Results

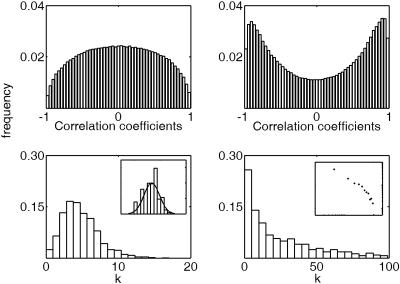

When c-Myc is activated by tamoxifen stimulation, the activity profile of the probe sets clearly changes into a strongly correlated regime. These findings are reflected in the histograms of the correlation coefficients for the N and T data sets (Fig. 1) and in the main parameters of the connectivity distributions obtained from the corresponding adjacency matrices (Table 1). For the T data set, the number of coefficients close to +1 or –1 increases significantly. This finding is an indication that many of the 1,191 genes that were affected mostly by tamoxifen stimulation in their expression levels over time became either strongly correlated or anticorrelated.

Fig. 1.

Correlation applied to N and T data sets. (Upper) Distribution of the correlation coefficients for the subset of 1,191 probe sets selected by two-way ANOVA for the N data set (Left) and the T data set (Right). (Lower Left) Histogram of p(k) for the network obtained from the N data set. (Inset) A log normal plot of the same distribution fitted with a Gaussian distribution of same mean and variance. (Lower Right) Histogram of p(k) for the T data set. (Inset) A log-log plot of the same distribution.

Table 1. Main properties of the N and T networks obtained by the correlation method.

| Parameters | N | T |

|---|---|---|

| kmin | 0 | 0 |

| kmax | 17 | 99 |

| Mean, k | 4.53 | 23.44 |

| Standard deviation, σ(k) | 2.61 | 23.97 |

| Skewness γ(k) | 0.89 | 1.16 |

| Clustering coefficient c(k) | 0.43 | 0.45 |

Both networks appear to be highly clustered (Table 1), as compared with a random network with the same number of nodes and average connectivity degree. The T connectivity degree distribution is much more broad and skewed, whereas the N connectivity degree distribution is peaked around its average value.

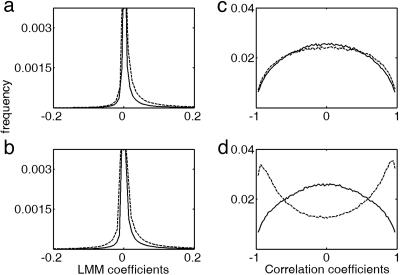

Considering the change in connectivity as an index for ranking the involvement of a gene in the c-Myc activation cascade, we looked at the distribution of the differences in connectivity of the probe sets (Table 2 shows a list of genes extracted from the upper tail of such a distribution). Application of a random permutation to the time series confirmed that this results depend on the exact time ordering of the gene expression levels (Fig. 2). Some features of the network structure, like the assortative mixing property (15) and the differences between the N and T data sets, are completely disrupted by time shuffling, leading to networks very similar to those obtained starting from randomly generated data of the same dimensionality, mean, and variance (data not shown).

Table 2. c-Myc target genes extracted from the selected 1,191 probe sets.

| GenBank | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| D13921 | Acat1 | Acetyl-coenzyme A acetyltransferase 1 |

| J02752 | Acox1 | Acyl-coA oxidase |

| AA799466 | Ak2 | Adenylate kinase 2 |

| M73714 | Aldh3a2 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase family 3, subfamily A2 |

| M60322 | Aldr1 | Aldehyde reductase 1 |

| AI177096 | Aprt | Adenine phosphoribosyl transferase transferase (APRT) |

| U07201 | Asns | Asparagine synthetase |

| U00926 | Atp5d | ATP synthase, F1 complex, delta subunit |

| At4g36870 | Blh2 | BEL1-like homeobox 2 protein |

| M81681 | Blvra | Biliverdin reductase A |

| AA859938 | Bnip31 | BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19-kDa-interacting protein 3-like |

| AI178135 | C1qbp | Complement component 1, q subcomponent binding protein |

| L24907 | Camk1 | Regulator of G-protein signaling 19 |

| U53858 | Capn1 | Calpain 1 |

| U53859 | Capns1 | Calpain, small subunit 1 |

| D89069 | Cbr1 | Carbonyl reductase 1 |

| AA891207 | Cd36l2 | CD36 antigen (collagen type I receptor, thrombospondin receptor)-like 2 |

| D26564 | Cdc37 | Cell division cycle 37 homolog |

| L11007 | Cdk4 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 4 |

| AB009999 | Cds1 | CDP-diacylglycerol synthase |

| U66470 | Cgref1 | Cell growth regulator with EF hand domain 1 |

| M15882 | Clta | Clathrin, light polypeptide (Lca) |

| D28557 | Csda | Cold shock domain protein A |

| AI008888 | Cstb | Cystatin B |

| AJ000485 | Cyln2 | Cytoplasmic linker 2 |

| U95727 | Dnaja2 | DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog, subfamily A, member 2 |

| U08976 | Ech1 | Enoyl coenzyme A hydratase 1 |

| D38056 | Efna1 | Ephrin A1 |

| U19516 | Eif2b5 | Initiation factor eIF-2Be |

| X03362 | Erbb2 | v-erb-b2 oncogene homolog 2 |

| U36482 | Erp29 | Endoplasmic retuclum protein 29 |

| J04473 | Fh1 | Fumarate hydratase 1 |

| AI231547 | Fkbp4 | FK506 binding protein 4 (59 kDa) |

| M81225 | Fnta | Farnesyltransferase, CAAX box, α |

| AI136396 | Fntb | Farnesyltransferase β subunit |

| AA891857 | Fxc1 | Fractured callus expressed transcript 1 |

| AA892649 | Gabarap | γ-Aminobutyric acid receptor associated protein |

| J03588 | Gamt | Guanidinoacetate methyltransferase |

| D30735 | Gfer | Growth factor, erv1-like |

| U38379 | Ggh | γ-Glutamyl hydrolase |

| AA944423 | Gm130 | cis-Golgi matrix protein GM130 |

| AA799779 | Gnpat | Acyl-CoA:dihydroxyacetone phosphate acyltransferase |

| U62940 | Grpel1 | GrpE-like 1, mitochondrial |

| X04229 | Gstm1 | Glutathione S-transferase, μ 1 |

| AB008807 | Gsto1 | Glutathione S-transferase ω 1 |

| D16478 | Hadha | Hydroxyacyl-Coenzyme A dehydrogenase/3-ketoacyl-Coenzyme A thiolase/enoyl-coenzyme A hydratase (trifunctional protein), α subunit |

| AA892036 | Hdac6 | Histone deacetylase 6 |

| X52625 | Hmgcs1 | 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A synthase 1 |

| D14048 | Hnrpu | System N1 Na+ and H+-coupled glutamine transporter |

| S57565 | Hrh2 | Histamine receptor H |

| AA957923 | Mcpt2 | Mast cell protease 2 |

| U62635 | Mrp123 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein L23 |

| AF104399 | Msg1 | Melanocyte-specific- gene 1 protein |

| X93495 | Mtap6 | Microtubule-associated protein 6 |

| M55017 | Ncl | Nucleolin |

| AF045564 | Ndr4 | N-myc downstream regulated |

| AA874794 | Ngfrap1 | Nerve growth factor receptor associated protein 1 |

| AA998882 | Nopp140 | Nucleolar phosphoprotein p130 |

| J04943 | Npm1 | Nucleophosmin 1 |

| M25804 | Nr1d1 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 1, group D, member 1 |

| AB015724 | Nrbf1 | Nuclear receptor binding factor 1 |

| AA800679 | Ns | Nucleostemin |

| D13309 | Nsep1 | Nuclease sensitive element binding protein 1 |

| X82445 | Nudc | Nuclear distribution gene C homolog |

| U03416 | Olfm1 | Olfactomedin-related ER localized protein |

| U26541 | Pdap1 | PDGFA-associated protein 1 |

| M80601 | Pdcd2 | Programmed cell death 2 |

| S82627 | Pem | Placentae and embryos oncofetal gene |

| AI169417 | Pgam1 | Phosphoglycerate mutase 1 |

| AA998446 | Pitpnb | Phosphotidylinositol transfer protein, β |

| X71898 | Plaur | Plasminogen activator, urokinase receptor |

| L25331 | Plod | Procollagen-lysine hydroxylase |

| S55427 | Pmp22 | Peripheral myelin protein 22 |

| AJ222691 | Pold1 | DNA polymerase delta, catalytic subunit |

| AB017711 | Polr2f | Polymerase II |

| Z71925 | Polr2g | RNA polymerase II polypeptide G |

| AA892298 | Ppil3 | Peptidylprolyl isomerase (cyclophilin)-like 3 |

| Y17295 | Prdx6 | Peroxiredoxin 6 |

| D85435 | Prkcdbp | PKC-delta binding protein |

| D26180 | Prkcl1 | Protein kinase C-like 1 |

| AA891871 | Prpsap1 | Phosphoribosylpyrophosphate synthetase-associated protein |

| D10756 | Psma5 | Proteasome subunit, α type 5 |

| D10755 | Psma6 | Proteasome subunit, α type 6 |

| U03388 | Ptgs1 | Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 1 |

| L27843 | Ptp4a1 | Protein tyrosine phosphatase 4a1 |

| U53475 | Rab8b | GTPase Rab8b |

| AA956332 | Rabep1 | Rabaptin 5 |

| L19699 | Ralb | v-ral oncogene homolog B |

| U82591 | Rcl | Chromosome 6 open reading frame 108 |

| X62528 | Rnh1 | Ribonuclease/angiogenin inhibitor |

| X78327 | Rpl13 | Ribosomal protein L13 |

| X78167 | Rpl15 | Ribosomal protein L15 |

| M20156 | Rpl18 | Ribosomal protein L18 |

| M17419 | Rpl5 | Ribosomal protein L5 |

| X62145 | Rpl8 | Ribosomal protein L8 |

| X53377 | Rps7 | Ribosomal protein S7 |

| AB002406 | Ruvbl1 | RuvB-like protein 1, TIP49 |

| AA799614 | Sirt2 | Sirtuin 2 (SIRT2 homolog) |

| D12771 | Slc25a5 | Solute carrier family 25, adenine nucleotide translocator, member 5 |

| AF015305 | Slc29a2 | Solute carrier family 29, member 2 |

| U60882 | Hrmtl12 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein methyltransferase-like 2 |

| U68562 | Hsp60 | Heat shock protein 60 (liver) |

| M86389 | Hspb1 | Heat shock 27-kDa protein 1 |

| U68562 | Hspe1 | Heat shock 10-kDa protein 1 |

| X65036 | Itga7 | Integrin α 7 |

| X17163 | Jun | v-jun sarcoma virus oncogene homolog |

| M75148 | Klc1 | Kinesin light chain 1 |

| M19647 | Klk7 | Kallikrein 7 |

| L38644 | Kpnb1 | Karyopherin β 1 |

| D90211 | Lamp2 | Lysosomal membrane glycoprotein 2 |

| U19614 | Lap1c | Lamina-associated polypeptide 1C |

| M69055 | Lgfbp6 | Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 6 |

| AI234060 | Lox | Lysyl oxidase |

| M61177 | Mapk3 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase, ERK1 |

| AA899253 | Marcks | Myristoylated alanine-rich protein kinase C substrate |

| AI011498 | Smarcd2 | SWI/SNF-related, matrix-associated, actin-dependent regulator of chromatin, subfamily d, member 2 |

| AF007758 | Snca | Synuclein, α |

| AI030175 | Sord | Sorbitol dehydrogenase |

| D37920 | Sqle | Squalene epoxidase |

| J05035 | Srd5a1 | Steroid 5 α-reductase 1 |

| Y15068 | Stip1 | Stress-induced-phosphoprotein 1 (Hsp70/Hsp90-organizing protein) |

| D12927 | Tcea2 | Transcription elongation factor A2 |

| M58040 | Tfrc | Transferrin receptor |

| M61142 | Thop1 | Thimet oligopeptidase 1 |

| AB006451 | Timm23 | Translocase of inner mitochondrial membrane 23 homolog |

| U09256 | Tkt | Transketolase |

| S63830 | Vamp3 | Vesicle-associated membrane protein 3 |

| U14746 | Vhl | von Hippel-Lindau syndrome homolog |

| AA875455 | Wig1 | p53-Activated gene 608 |

| U96490 | Yif1p | Yip1p-interacting factor |

| S55223 | Ywhab | Tyrosine 3-monooxygenase, tryptophan 5-monooxygenase activation protein, β polypeptide |

Probes were chosen as those that mostly changed their connectivity degree between the N and T data sets.

Fig. 2.

Effects of data reshuffling on LMM and correlation coefficients distribution obtained from the 1,191 selected probe sets. Dashed lines indicate original data. Solid lines indicate reshuffled data. (a) N data set, LMM. (b) T data set, LMM. (c) N data set, correlation. (d) T data set, correlation.

In comparison, the gene network constructed with the LMM appears to be completely insensitive to the effects of tamoxifen. The p(k) distribution for N and T follows a power-law function p(k) ∝ k–α with a very similar exponent, αN = 2.41 ± 0.16 and αT = 2.41 ± 0.12, respectively. There is no evident change between the T and N networks. Moreover, the main properties of the N and T networks, namely the power-law exponent and dissassortative mixing property (15), are left unchanged by time reshuffling. Thus, even if the individual genes connectivity degree changes from the N and T data sets, the insensitivity to time shuffling casts some doubts on the reliability and significance of such changes in the LMM.

Discussion

A correlation-based model was used to identify a gene interaction network, based on a time series of gene expression measurements, resulting from the acute activation of an engineered c-Myc transcription factor in a c-myc null cell line. The global properties of the resulting network were strongly affected by c-Myc activation. The comparison between the networks obtained with the different data sets led to the identification of unique c-Myc targets. The list of genes found with this method contains some of the genes found in ref. 14 but also contains many genes that were not found before to our knowledge, pointing to the possibility that the potential list of c-Myc targets may be much larger than what was previously observed.

These network properties were disrupted by time reshuffling of the data, confirming the hypothesis that they refer to real information contained in gene expression dynamics.

The same analysis was performed on the gene network obtained with a LMM, which has been proposed in the past for the analysis of time-dependent genomic measurements. The global features of this network did not significantly change neither in response to c-Myc activation, nor after time reshuffling of the data, suggesting that they depend on some global properties of the data set distribution and not on the exact details of gene expression dynamics.

Acknowledgments

D.R. and G.C.C. were supported by a Fondo per gli Investimenti della Ricerca di Base grant (Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Università e della Ricerca) and Vice President for Research support from Brown University.

Author contributions: D.R., J.M.S., and G.C.C. designed research; D.R., B.O., J.M.S., and G.C.C. performed research; D.R., N.I., N.N., and G.C.C. analyzed data; D.R., N.I., J.M.S., N.N., G.C.C., and L.N.C. wrote the paper; D.R. developed the analysis method; and L.N.C. provided general supervision and assessment of theoretical models.

Abbreviation: LMM, linear Markov model.

References

- 1.Qin, J., Lewis, D. P. & Noble, W. S. (2003) Bioinformatics 19, 2097–2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Narayanan, A., Keedwell, E. C. & Olsson, B. (2002) Appl. Bioinformatics 1, 191–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisen, M., Spellman, P., Brown, P. & Botstein, D. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 14863–14868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R., Eisen, M. B., Alizadeh, A., Levy, R., Staudt, L., Chan, W. C., Botstein, D. & Brown, P. (2000) Genome Biol. 1, research0003.1–0003.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toronen, P., Kolehmainen, M., Wong, G. & Castren, E. (1999) FEBS Lett. 451, 142–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vohradsky, J. (2001) FASEB J. 15, 846–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vazquez, A., Flammini, A., Maritan, A. & Vespignani, A. (2003) Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 697–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeong, H., Tombor, B., Albert, R., Oltvai, Z. N. & Barabasi, A. L. (2000) Nature 407, 651–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dewey, T. G. & Galas, D. J. (2001) Funct. Integr. Genomics 1, 269–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holter, N. S., Maritan, A., Cieplak, M., Fedoroff, N. V. & Banavar, J. R. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 1693–1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arkin, A., Shen, P. & Ross, J. (1997) Science 277, 1275–1279. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spellman, P. T., Sherlock, G., Zhang, M. Q., Iyer, V. R., Anders, K., Eisen, M. B., Brown, P. O., Botstein, D. & Futcher, B. (1998) Mol. Biol. Cell 9, 3273–3297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butte, A. J., Tamayo, P., Slonim, D., Golub, T. R. & Kohane, I. S. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 12182–12186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Connell, B. C., Cheung, A. F., Simkevich, C. P., Tam, W., Ren, X., Mateyak, M. K. & Sedivy, J. M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 12563–12573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newman, M. E. J. (2002) Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 208701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]