Abstract

Background:

Persons seeking emergency injury care are often from underserved key populations (KPs) and priority populations (PPs) for HIV programming. While facility-based HIV Testing Services (HTS) in Kenya are effective, emergency department (ED) delivery is limited, despite the potential to reach underserved persons.

Methods:

This quasi-experimental prospective study evaluated implementation of the HIV Enhanced Access Testing in Emergency Departments (HEATED) at Kenyatta National Hospital ED in Nairobi, Kenya. The HEATED program was designed using setting specific data and utilizes resource reorganization, services integration and HIV sensitization to promote ED-HTS. KPs included sex workers, gay men, men who have sex with men, transgender persons and persons who inject drugs. PPs included young persons (18–24 years), victims of interpersonal violence, persons with hazardous alcohol use and those never previously HIV tested. Data were obtained from systems-level records, enrolled injured patient participants and healthcare providers. Systems and patient-level data were collected during a pre-implementation period (6 March - 16 April 2023) and post-implementation (period 1, 1 May - 26 June 2023). Additional, systems-level data were collected during a second post-implementation (period 2, 27 June – 20 August 2023). Evaluation analyses were completed across reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation and maintenance framework domains.

Results:

All 151 clinical staff were reached through trainings and sensitizations on the HEATED program. Systems-level ED-HTS increased from 16.7% pre-implementation to 23.0% post-implementation periods 1 and 2 (RR=1.31, 95% CI:1.21–1.43; p<0.001) with a 62.9% relative increase in HIV self-test kit provision. Among 605 patient participants, facilities-based HTS increased from 5.7% pre-implementation to 62.3% post-implementation period 1 (RR=11.2, 95%CI:6.9–18.1; p<0.001). There were 440 (72.7%) patient participants identified as KPs (5.6%) and/or PPs (65.3%). For enrolled KPs/PPs, HTS increased from 4.6% pre-implementation to 72.3% post-implementation period 1 (RR=13.8, 95%CI:5.5–28.7, p<0.001). Systems and participant level data demonstrated successful adoption and implementation of the HEATED program. Through 16-weeks post-implementation a significant increase in ED-HTS delivery was maintained as compared to pre-implementation.

Conclusions:

The HEATED program increased ED-HTS and augmented delivery to KPs/PPs, suggesting that broader implementation could improve HIV services for underserved persons, already in contact with health systems.

Keywords: HIV testing, Key populations, Testing, Health systems, Emergency Care, Kenya

INTRODUCTION

There are approximately 38 million people living with HIV (PLH) globally, of whom 70% reside in sub-Saharan Africa.1,2 Although progress was been made toward the UNAIDS 95-95-95 HIV control targets, they are at risk of not being achieved.3 In sub-Saharan Africa, Kenya has reduced the national HIV prevalence, however incidence reduction targets have not been met, and in 2021 there was an 7.8% increase in new infections.4 The epidemic in Kenya is driven by higher-risk persons who have been insufficiently reached and underserved by HIV Testing Services (HTS).4–6 These include key populations (KPs) of sex workers (SWs), men who have sex with men (MSM), transgender persons and people who inject drugs (PWID) in which HIV prevalence is five-fold higher than the general population.5,7 Additional priority populations (PPs) including men, young people (<25 years) and persons who use drugs have been insufficiently reached further contributing to epidemic propagation.8–11 Young people in Kenya account for 42% of new infections and one in four Kenyan men with HIV are undiagnosed.5 To achieve epidemic control, these higher-risk persons must be reached for HIV testing and linkage to care.2,9 However with persistent HIV programming barriers stemming from structural and cultural aspects as well as stigma and discrimination,12–16 innovative service delivery approaches are needed.

Emergency Departments (ED) in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are an under-used HTS service delivery point with the potential to reach KP/PPs already in contact with health systems.17,18 In LMICs, EDs provide care to large numbers of patients who may not otherwise regularly access healthcare, and often for treatment of injuries.17,19,20 Data from sub-Saharan Africa shows patients seeking injury treatments have high HIV burdens and are often first diagnosed during those evaluations.21–25 Globally, young people and men are most likely to experience injuries,26,27 and KPs have elevated risks for interpersonal violence, gender-based violence, and self-harm.28,29 In Kenya, data from the National AIDS and STIs Control Programme (NASCOP) demonstrates high prevalence of violence experienced by SW (48%), PWID (44%), and MSM (20%).30 Given injury risk burdens among KP/PPs in Kenya and subsequent needs for emergency care, development of effective ED-HTS with a focus on engaging injured populations, represents a pragmatic approach to reach higher-risk persons already engaged in care.18,31

Kenya’s national HTS guidelines recommend HIV screening and targeted testing during all health-facility interactions with the goal of testing quarterly for KPs and every 6–12 months for PPs.8 Although this includes EDs, there is no specific program guidance to inform ED-HTS delivery. To address this, data from patient and healthcare provider stakeholders from the Kenyatta National Hospital (KNH) ED, in Nairobi, Kenya,32,33 were used to design the HIV Enhanced Access Testing in Emergency Departments (HEATED) program to improve ED-HTS delivery.

METHODS

This quasi-experimental prospective study evaluated implementation of the HEATED program using the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework applied to systems, patient and healthcare provider level data.34 Study periods included: pre-implementation (6 March – 16 April 2023), implementation (17 April – 30 April 2023), post-implementation period 1 (1 May – 26 June 2023) and post-implementation period 2 (27 June – 20 August 2023). Guidelines on implementation studies were adhered to in reporting these results.35

Study Setting

The KNH ED, in Nairobi, Kenya provides 24-hour care access. At study initiation, there were 143 nurse, and physician staff members and eight HIV-services personnel working in the clinical setting. The ED offers continuous HTS with dedicated space and staffing for services. HTS is provided free of charge, using Alere Determine™ HIV-1/2 assays or OraQuick Rapid™ HIV-1/2 HIV self-test (HIVST) kits. Standardized records for all patients undergoing HTS are maintained using national reporting procedures, and any PLH identified is provided free follow up care at a government facility. Kenya’s national guidelines stipulate that screening for, and delivery of HTS, should occur during facility-based healthcare encounters = and recommends testing frequencies of every two years for the general population, quarterly for KPs and every 6–12 months for PPs.5,36

HIV Enhanced Access Testing in Emergency Departments Program

The HEATED program aims to increase ED-HTS delivery and improve engagement for underserved higher-risk persons by supporting HIV service for injured persons and KP/PPs. The program was designed to be a pragmatic multi-component intervention which employs setting appropriate micro-strategies focused on HTS sensitization and integration, task shifting, resource reorganization, linkage advocacy, skills development and education. The HEATED program was developed through qualitative research from healthcare providers and patient stakeholders from the KNH emergency care setting.32,33 Qualitative data were mapped to the Capability-Opportunity-Motivation Behavioral model for change and the Theoretical Domains Framework to identify data-driven micro-strategies to enhance ED-HTS.37,38 A multipronged implementation strategy including training and educating, changing infrastructure and developing stakeholder interrelationships was used to implement the HEATED program (Supplement 1).39

Data Sources

Systems-Level Data

Systems level data were collected from standardized clinical sources. The ED triage register was used to identify numbers of persons treated during study periods. HTS registries provided data on facility-based testing, HIVST provision and follow up and identification and linkage to care for PLH. Data were abstracted by trained study personnel and into digital databases with continuous quality monitoring.40

Data were collected from healthcare personnel. ED-HIV services providers were screened, consented and enrolled as participants. They were sampled during each study period using the Continuing professional development (CPD) Reaction questionnaire oriented to the research topic of ED-HTS for injured and higher-risk persons.41 The CPD-Reaction questionnaire is a validated instrument used in implementation sciences research, for assessing the impact of professional development activities on clinical behaviors.42,43 Anonymized data were collected during post-implementation period 2 from ED nurses and physicians via open ended self-completed surveys on perceptions of the HEATED program.

Patient Participant-Level Data

During pre-implementation and post-implementation period 1, data were obtained from enrolled patient participants. Trained study personnel present in the ED 24-hours a day collected standardized survey data. All patients ≥18 years, seeking injury care were eligible for participation. Injury designation used the standardized triage classification in the study setting.44 Patients known to be pregnant, incarcerated persons and those unable or unwilling to provide consent were excluded.

After provision of written informed consent, patient participants had enrollment data collected as close to ED arrival as possible on sociodemographics, past medical and social histories, HIV risk factors including screening for KPs and PPs. PPs based on Kenya’s national guidelines included young persons (18–24 years), victims of interpersonal violence (IPV), persons never previously HIV tested and persons with hazardous alcohol use (HAU).5 The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) was used to identify HAU.45,46 At emergency care completion, patient participant data were collected on awareness and understanding of ED-HTS and services received. For patient participants who received ED-HTS, systems level data were linked and cross-referenced to validate report.

Evaluation Approach

HEATED program implementation was assessed using the RE-AIM framework.34 The evaluation metrics for each dimension are shown in Table 1. Reach, effectiveness and implementation, data were assessed using systems and patient participant data. For adoption and maintenance, systems level data were used. CPD-Reaction scores from ED-HIV service providers were compared pre-implementation and post-implementation period 1. The constructs of intention and social influence, which represent willingness by the primary intervention agent to initiate a health behavior, were used for adoption. Constructs of beliefs about capabilities and moral norms representing the intervention agents’ fidelity to deliver the health service were used in assessment of implementation. Final CPD-Reaction scores obtained during post-implementation period 2, were used in assessment of maintenance, along with the longitudinal systems-level trends in HTS delivery

Table 1.

HIV Enhanced Access Testing in the Emergency Department Program Evaluation Assessment Metrics Across Study Periods

| Dimension | Pre-implementation (March 6 - April 16) | Program Implementation (April 17 - April 30) | Post-Implementation (Period 1: May 1 - June 26) | Post-Implementation (Period 2: June 27 - August 20) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reach | ||||

| Systems Metrics | Healthcare provider sensitizations | |||

| Patient Participant Metrics | Patient triage screen for interest on learning about options for HIV testing | Patient triage screen for interest on learning about options for HIV testing | ||

| Patients aware of HIV testing at care conclusion | Patients aware of HIV testing at care conclusion | |||

| Effectiveness | ||||

| Systems Metrics | HIV services cascade delivery: testing, identification of people living with HIV and linkage to care | HIV services cascade delivery: testing, identification of people living with HIV and linkage to care | HIV services cascade delivery: testing, identification of people living with HIV and linkage to care | |

| Patient Participant Metrics | Patient HIV Testing completion | Patient HIV Testing completion | ||

| Patient HIV Testing completion among Key or Priority populations1 | Patient HIV Testing completion among Key or Priority populations1 | |||

| Adoption | ||||

| Systems Metrics | HIV services personnel Continuing Professional Development assessments | HIV services personnel Continuing Professional Development assessments | ||

| Emergency Department healthcare provider program feedback | ||||

| Patient Participant Metrics | Patient interactions with healthcare providers on HIV testing services during emergency care | Patient interactions with healthcare providers on HIV testing services during emergency care | ||

| Implementation | ||||

| Systems Metrics | HIV services personnel Continuing Professional Development assessments | HIV services personnel Continuing Professional Development assessments | ||

| Patient Participant Metrics | Patient understanding of option for emergency department HIV Testing | Patient understanding of option for emergency department HIV Testing | ||

| Maintenance | ||||

| Systems Metrics | HIV services personnel Continuing Professional Development assessments | HIV services personnel Continuing Professional Development assessments | ||

| Longitudinal delivery of HIV testing services | Longitudinal delivery of HIV testing services | Longitudinal delivery of HIV testing services | ||

Key Populations Key populations include sex workers, men who have sex with men, gay persons, transgender persons, and persons who inject drugs. Priority populations include persons 18–24 years of age, victims of interpersonal violence, persons who screened positive on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Concise, persons who never previously tested for HIV

Statistical Analysis

The sample size was based on the outcome of increasing the proportion HIV test completed for injured persons seeking emergency care among enrolled patient participants. Prior data from the study setting demonstrated that 5.6% of injured patients completed ED-HIV testing.25 To be able to identify a 10% absolute increase in the proportion of injured patients completing testing, a sample size of ≥175 participant per assessment period was need (80% power, alpha <0.05).47

Descriptive analyses were performed for systems level and participant level data using frequencies with percentages or medians with associated interquartile ranges (IQR) as appropriate. Level of agreement for 5-point scale Likert scale items were summarized using medians with IQRs. HTS data were evaluated as facility-based HIV testing and distribution of HIVSTs independently, and aggregated as ED-HTS. Moving biweekly averages for HTS with associated variance estimates were calculated and graphed over time. Comparative analyses based on study period were performed using Pearson X2 or Fisher’s exact tests and Mann-Whitney tests as appropriate. Using the pre-implementation data as the baseline comparator, risk ratios (RR) were calculated with associated 95% confidence intervals (CI) for HTS cascade metrics for systems level and participant level data. An a priori subgroup analysis was completed on HIV testing for KPs and PPs among enrolled patient participants.

Ethical Approvals

The study was approved by the University of Nairobi ethics and research committee and the institutional review board of Rhode Island Hospital. All enrolled participants provided written informed consent.

RESULTS

Study Population

Systems-level

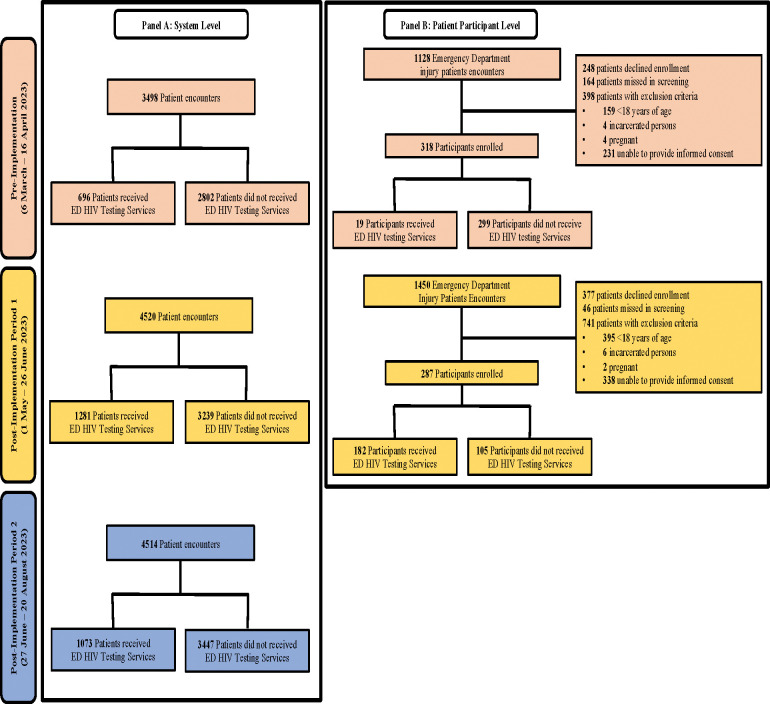

There were a total of 12,532 ED encounters during data collection periods. Of these, 3,050 (24.4%) received ED-HTS, with 696 pre-implementation and 2,354 post-implementation (Figure 1 Panel A). The majority of persons who received facility-based HTS were male and >25 years of age. Across all periods, approximately two-thirds of persons completing facility-based HTS had never previously been tested for HIV (Table 2).

Figure 1:

Study Population

Table 2.

System-level Data on Recipients of HIV Testing Services

| Pre-implementation (March 6 – April 16) n (%) |

Post-Implementation (Period 1: May 1 - June 26) n (%) |

p-value | Post-Implementation (Period 2: June 27 - August 20) n (%) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Completed Facilities-based HIV Testing | 585 | 1031 | 860 | ||

|

| |||||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 296 (50.6) | 574 (55.7) | 0.046 | 503 (58.5) | 0.008 |

| Female | 286 (48.9) | 456 (44.2) | 350 (40.7) | ||

| Transgender | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Missing | 3 (0.6) | 1 (0.1) | 7 (0.8) | ||

| Age years (median) | 34 (25, 43) | 35 (27, 44) | 0.313 | 33 (26, 43) | 0.775 |

| Age 15–24 years | 95 (16.2) | 164 (15.9) | 0.861 | 159 (18.5) | 0.270 |

| Key Population1 | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.2) | 1.00 | 10 (1.2) | 0.058 |

| Ever previously Tested for HIV | |||||

| No | 381 (65.1) | 673 (65.3) | 0.046 | 565 (65.7) | 0.027 |

| Yes | 194 (33.2) | 353 (34.2) | 292 (36.0) | ||

| Missing | 10 (1.7) | 5 (0.5) | 3 (0.03) | ||

| Used HIV self-test in last 12 months | |||||

| No | 571(97.6) | 1020 (98.93) | 857 (99.7) | <0.001 | |

| Yes | 14(2.4) | 11 (1.07) | 0.038 | 3 (0.3) | |

|

| |||||

| Persons accepting HIV self-test kits | 111 | 250 | 213 | ||

|

| |||||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 49 (44.1) | 128 (51.2) | 0.090 | 138 (64.8) | <0.001 |

| Female | 59 (53.2) | 121 (48.4) | 74 (34.7) | ||

| Transgender | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Missing | 3(2.7) | 1(0.4) | 1(0.5) | ||

| Age 15–24 years | 33 (29.7) | 38 (15.2) | 0.084 | 49 (23.0) | 0.186 |

Key populations include sex workers, men who have sex with men, gay persons, transgender persons and persons who inject drugs.

Patient Participant level

During pre-implementation and post-implementation period 1, there were 2,578 injury encounters. Of these, 2,303 (89.3%) were screened, 605 (26.3%) met inclusion and were enrolled. During pre-implementation 19 of 318 participants received ED-HTS; and 182 of 287 participants received ED-HTS post-implementation (Figure 1, Panel B). Patient participant characteristics were similar between pre-implementation and post-implementation period 1. The majority of participants were male and approximately one-quarter were <25 years of age. KPs comprised 5.0% of patient participants pre-implementation and 6.3% in post-implementation period 1 (p=0.508). PPs were 67.0% of participants pre-implementation and 63.3% in post-implementation period 1 (p=0.640). Similar portions of participants had never been HIV tested 12.9% pre-implementation versus 12.6% post-implementation (p=0.881). One third of participants had a history of interpersonal violence (33.3% pre-implementation, 33.1% post-implementation, p=0.952) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Patient Participant Characteristics

| Pre-implementation (March 6 - April 16) n (%) |

Post-Implementation (Period 1: May 1 - June 26) n (%) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age (median, IQR) | 31 (25–38) | 30 (24–38) | 0.655 |

| Young adult (18–24 years) | 76 (23.9) | 76 (26.6) | 0.450 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 263 (82.7) | 231 (80.5) | 0.608 |

| Female | 53 (16.7) | 54 (18.9) | |

| Transgender | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.7) | |

| Relationship Status | |||

| Single | 115 (36.3) | 138 (48.3) | <0.001 |

| Married | 163 (51.4) | 96 (33.2) | |

| In a monogamous relationship | 17 (5.4) | 32 (11.2) | |

| In a polygamous relationship | 1 (0.3) | 4 (1.4) | |

| Separated (still married) | 16 (5.1) | 10 (3.5) | |

| Wishes not to disclose | 5 (1.6) | 5 (1.8) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.7) | |

| Education | |||

| Primary schooling or less | 91 (28.6) | 97 (33.8) | 0.328 |

| Secondary schooling or greater | 225 (70.8) | 188 (65.5) | |

| Missing | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.7) | |

| Employment Status | |||

| Employed | 236 (74.2) | 233 (81.2) | 0.102 |

| Unemployed | 77 (24.2) | 52 (18.1) | |

| Missing | 5 (1.6) | 2 (0.7) | |

| Has Established Primary Care Provider | |||

| No | 260 (81.8) | 234 (81.5) | 0.992 |

| Yes | 56 (17.6) | 51 (17.8) | |

| Missing | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.7) | |

| Identifies as a Key Population1 | 16 (5.0) | 18 (6.3) | 0.508 |

| Characterized as a Priority Population2 | 213 (67.0%) | 182 (63.4%) | 0.671 |

| Never Previously Tested for HIV | 41 (12.9) | 36 (12.6) | 0.881 |

| Hazardous Alcohol Use1 | 80 (25.2) | 70 (24.5) | 0.827 |

| History of Interpersonal Violence | |||

| No | 212 (66.7) | 192 (66.9) | 0.952 |

| Yes | 106 (33.3) | 95 (33.1) | |

| Condomless sex in last six months | |||

| No | 164 (51.6) | 157 (54.6) | 0.904 |

| Yes | 142 (44.7) | 117 (40.9) | |

| missing | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.7) | |

| Emergency Department Disposition | |||

| Discharged | 175 (55.0) | 36 (60.0) | 0.681 |

| Admitted | 130 (41.0) | 23 (38.3) | |

| Eloped | 6 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Missing | 7 (2.2) | 1(1.67) | |

Key Populations Key populations include sex workers, men who have sex with men, gay persons, transgender persons, and persons who inject drugs

Priority populations include persons 18–24 years of age, victims of interpersonal violence, persons who screened positive on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, persons who never previously tested for HIV

Reach

All 151 ED personnel were reached though HEATED program sensitization. In-person sessions were attended by 45% of personnel, and all personnel received digital communications. All eight ED-HIV services providers completed HEATED program training on HTS for underserved higher-risk persons (Supplement 1). Among patient participants, screening at triage on interest in learning about ED-HTS options increased from 3.5% pre-implementation to 46.7% post-implementation period 1 (p<0.001). At ED care completion, patient participant awareness of ED-HTS options increased from 37.7% pre-implementation 76.9% to post-implementation period 1 (p<0.001) (Table 5).

Table 5.

HIV Testing Services For Patient Participants From Key and Priority Populations

| Pre-implementation (March 6 - April 16) N=216 n (%) |

Post-Implementation (Period 1: May 1 - June 26) N=184 n (%) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Key & Priority Populations1 | |||

| Not Receiving HIV Testing Services | 206 (95.4) | 51 (27.7) | <0.001 |

| Receiving HIV Testing Services | 10 (4.6) | 133 (72.3) | |

|

| |||

| Key & Priority Populations1 Receiving HTS | |||

|

| |||

| Young Adult | 1 (10.0) | 14 (14.7) | |

| & Never Previously Tested for HIV | 1 (10.0) | 10 (7.5) | |

| & Hazardous Alcohol Use | 1 (10.0) | 1 (0.8) | |

| & Interpersonal Violence Victim | 1 (10.0) | 11 (8.3) | |

| & Sex Work | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.5) | |

| & Never Previously Tested for HIV & Interpersonal Violence Victim | 0 (0.0) | 4 (3.0) | |

| & Interpersonal Violence Victim & Hazardous Alcohol Use | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.3) | |

| & Interpersonal Violence Victim & Sex Work | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.5) | |

| & Never Previously Tested for HIV & Sex Work & Gay | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | |

| & Interpersonal Violence Victim & Sex Work & Gay | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Never Previously Tested for HIV | 0 (0.0) | 4 (3.0) | |

| & Hazardous Alcohol Use | 1 (10.0) | 4 (3.0) | |

| & Interpersonal Violence Victim | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | |

| & Sex Work | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Hazardous Alcohol Use | 1 (10.0) | 20 (15.0) | |

| & Interpersonal Violence Victim | 0 (0.0) | 15 (11.3) | |

| & Sex Work | 0 (0.0) | 4 (3.0) | |

| & Gay | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| & Interpersonal Violence Victim & Sex Work | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.8) | |

| & Interpersonal Violence Victim & Person Who Injects Drugs | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | |

| & Interpersonal Violence Victim & Sex Work & Person Who Injects Drugs | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Interpersonal Violence Victim | 2 (20.0) | 30 (22.6) | |

| Sex Work | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Gay | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

Key Populations Key populations include sex workers, men who have sex with men, gay persons, transgender persons, and persons who inject drugs. Priority populations include young adult persons 18–24 years of age, victims of interpersonal violence, persons who screened positive on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test for Hazardous Alcohol use, persons who never previously tested for HIV

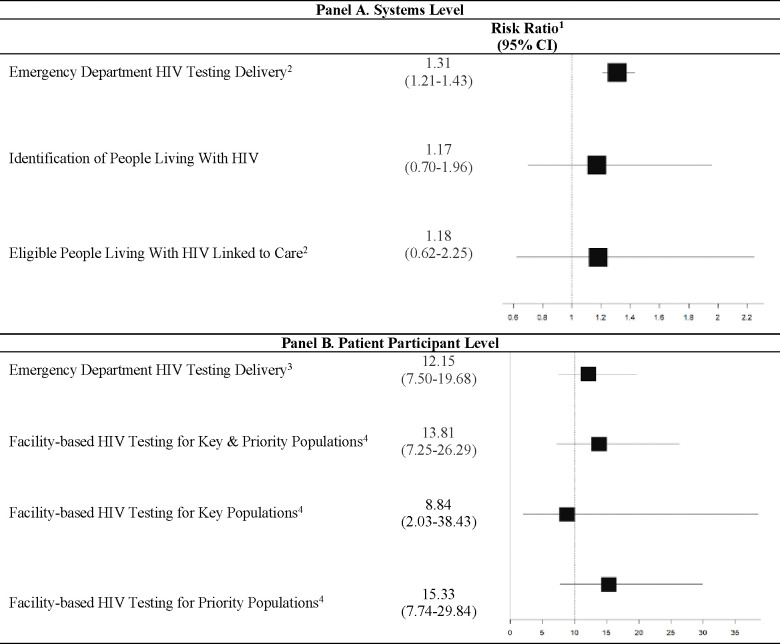

Effectiveness

ED-HTS, which aggregated facility-based HIV testing and distribution of HIVSTs, increased from 19.9% (95% CI: 18.6–21.3) pre-implementation to 28.5% (95% CI: 27.2–29.8) post-implementation period 1 and 23.8 (95% CI: 22.6–25.1) in post-implementation period 2. As compared to pre-implementation, systems level ED-HTS was significantly greater in the post-implementation periods (RR=1.31, 95% CI:1.21–1.43; p<0.001) (Figure 2 Panel A). Identification of PLH non-significantly increased from 24 (4.1%) pre-implementation to 53 (5.1%) post-implementation period 1 and to 43 (5.0%) post-implementation period 2. Among those tested in the ED and found to be PLH, 73% were newly diagnosed. Linkage to care of eligible PLH was 71.4.% pre-implementation, 81.1% in post-implementation period 1 (p=0.454) and 87.0% in post-implementation period 2 (p=0.242). The number of persons distributed HIVST kits increased with program implementation and there was a significant increase in follow up of usage by ED-HIV services providers (Table 4).

Figure 2.

HIV Services With Implementation of the HIV Enhanced Access Testing in the Emergency Department Program

1Risk ratios outcomes based on comparison of data aggregating post-implementation periods 1&2 with the pre-implementation period as the baseline.

2Eligible People Living With HIV included those not currently on antiretroviral treatments and discharged from the hospital alive

3HIV Testing Delivery aggregates both facility-based HIV testing and distribution of HIVST kits

4Key populations include sex workers, men who have sex with men, gay persons, transgender persons, and persons who inject drugs. Priority populations include persons 18–24 years of age, victims of interpersonal violence, persons who screened positive for hazardous alcohol use on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, persons never previously HIV tested

Table 4.

System Level Emergency Department HIV Testing Services

| Pre-implementation (March 6 - April 16) n (%) |

Post-Implementation (Period 1: May 1 - June 26) n (%) |

p-value | Post-Implementation (Period 2: Jun 27 - August 20) n (%) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Facility-based HIV testing | 585 | 1031 | 860 | ||

| HIV Test Result | |||||

| Negative | 560 (95.7) | 977 (94.8) | 0.453 | 816 (94.9) | 0.703 |

| Positive | 24 (4.1) | 53 (5.1) | 43 (5.0) | ||

| Inconclusive | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | ||

| Positive HIV Test Results | |||||

| Previously diagnosed | 8 (33.3) | 13 (24.5) | 0.555 | 15 (34.9) | 0.239 |

| New Diagnosis | 16 (66.7) | 40 (75.5) | 28 (65.1) | ||

| New Diagnosis Linked to Care | |||||

| No (declined) | 4 (25.0) | 7 (17.5) | 0.657 | 3 (10.7) | 0.447 |

| No (deceased) | 2 (12.5) | 3 (7.5) | 5 (17.9) | ||

| Yes | 10 (62.5) | 30 (75.0) | 20 (71.4) | ||

| New Eligible Diagnosis Linked to Care | |||||

| No (declined) | 4 (28.6) | 7 (18.9) | 0.454 | 3 (13.0) | 0.242 |

| Yes | 10 (71.4) | 30 (81.1) | 20 (87.0) | ||

| Previous Diagnosis Linked to Care | |||||

| No (Already linked to care) | 7 (87.5) | 8 (61.5) | 0.201 | 10 (66.7) | 0.651 |

| No (Declined) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (13.3) | ||

| Yes | 1 (12.5) | 5 (38.4) | 3 (20.0) | ||

| Previous Diagnosis Linked to Care (Eligible) | |||||

| No (Declined) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - | 2 (40.0) | 0.439 |

| Yes | 1(100.0) | 5 (100.0) | 3 (60.0) | ||

| Provision of HIV Self-Test | |||||

| HIV Self-Test Recipients | 111 | 250 | 213 | ||

| HIV Self-Test Follow-up Completed | |||||

| No | 21 (18.92) | 64 (25.6) | <0.001 | 42 (19.7) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 186 (74.4) | 171 (80.3) | ||

| Missing | 90 (81.09) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| HIV Self-Test Reported Use | |||||

| No | - | 10 (5.4) | - | 10 (5.9) | - |

| Yes | - | 176 (94.6) | 161 (94.2) | ||

| HIV Self-Test Reported Result | |||||

| Non-reactive | - | 176 (100.0) | - | 159 (98.8) | - |

| Reactive | - | 0(0.0) | 1(0.6) | ||

| Inconclusive | - | 0(0.0) | 1(0.6) | ||

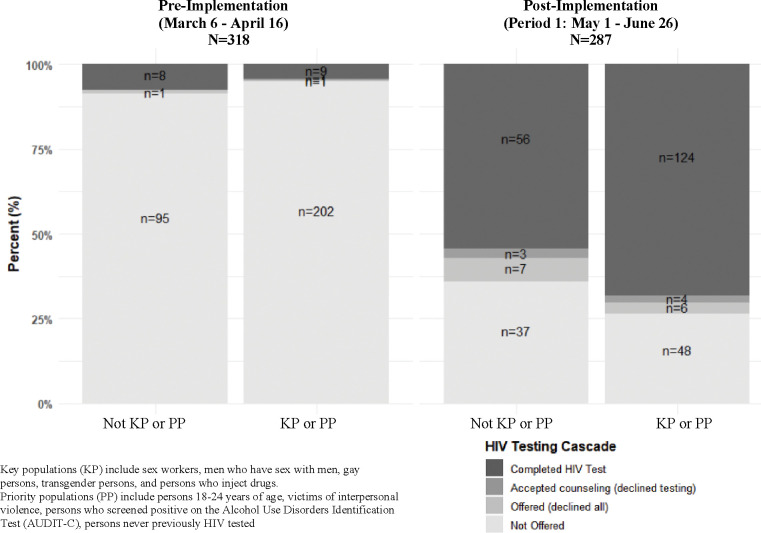

ED-HTS significantly increased among patient participants from 5.7% pre-implementation to 69.0% post-implementation period 1. There were three patient participants identified as PLH. Figure 3 shows changes in HTS cascade delivery with HEATED program implementation stratified by participants as KPs/PPs or not. For KPs/PPs participants facility-based HIV testing increased from 4.6% pre-implementation to 72.3% post-implementation period 2 (p<0.001). Among KPs/PPs completing facility-based HIV testing, 49% had multiple KP identifies and/or multiple categorizing PP characteristics (Table 5). As compared to pre-implementation, patient participants in post-implementation period 1 were significantly more likely to complete ED-HTS (RR=12.15, 95% CI:7.50–19.68; p<0.001). This significant increase was also found in the KPs (RR=8.84, 95% CI:2.03–38.43; p<0.001) and the PP (RR=15.22, 95% CI:7.74–29.94; p<0.001) (Figure 2 Panel B).

Figure 3.

HIV Testing Cascade Pre- and Post-implementation of the HIV Enhanced Access Testing in the Emergency Department Program Stratified by Key and Priority Populations

Adoption

ED-HIV services personnel CPD-Reactions scores increased pre-implementation period to post-implementation period 1. For the construct of intention median scores increased from 6.3 (IQR: 5,8, 6.8) to 6.5 (IQR: 6.5, 7.0) (p=0.682) and from 4.3 (IQR: 3.4, 4.7) to 5.2 (IQR: 4.3, 5.8) (p=0.014) for social influence (Supplement 2). Anonymous feedback from ED healthcare personnel was mixed with some personnel indicating that the HEATED program improved testing and was used well. However, there was concerns noted that not all staff were engaged (Supplement 3).

Implementation

Among ED-HIV services personnel scores for CPD-Reaction constructs of beliefs about capabilities and moral norms significantly increased. Median scores increased from 5.2 (IQR: 4.7, 5.7) pre-implementation to 6.0 (IQR: 5.8, 6.3) post-implementation period 1 (p=0.013) for beliefs about capabilities. For moral norms, median scores increased pre-implementation from 6.0 (IQR: 5.5, 6.0) to 6.8 (IQR: 6.0, 7.0) post-implementation period 1 (p=0.014) (Supplement 2). During pre-implementation 3.8% of enrolled patient participants reported discussing HTS with ED personnel during care, which increased to 85.3% post-implementation (p<0.001). There was a significant increase in agreement among enrolled patient participants that it was clear that ED-HTS was available with median Likert scores increasing from 2 (IQR: 1, 5) pre-implementation to 5 (IQR: 2, 5) post-implementation period 1 (P<0.001)

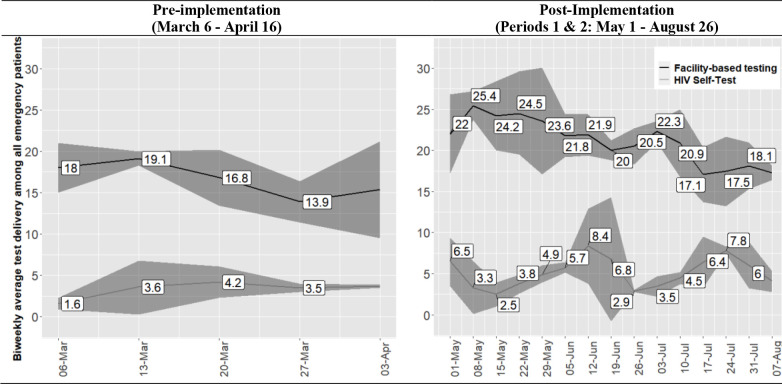

Maintenance

In post-implementation periods 1 and 2, encompassing 16 weeks of systems level data, a significant increase in ED-HTS delivery was maintained as compared to pre-implementation. Figure 4 shows bi-weekly average proportional ED-HTS delivery. Facility-based HTS ranged from 13.9% to 19.1% during pre-implementation and from 17.1% to 25.4% post-implementation. Bi-weekly average HIVST distribution ranged from 1.6% to 3.7% pre-implementation and from 2.5% to 8.4% post-implementation. CPD-Reaction scores for ED-HIV services personnel were persistently greater on follow up assessments during post-implementation period 2 as compared to pre-implementation (Supplement 2).

Figure 4.

Systems Level HIV Testing Services Delivery Across Study Periods1

1Biweekly average proportion of persons who received HIV testing services with associated 95% confidence intervals

DISCUSSION

The current study assessing implementation of the HEATED program demonstrates positive impacts on ED-HTS across the RE-AIM domains. The systems-level and patient participant data showed significantly increased testing services, suggesting that broader program development may represent a pragmatic approach to augment HTS delivery to higher-risk target populations. Considering the burdens of injury across sub-Saharan Africa requiring emergency care,26,27 particularly in underserved KP/PPs,28,29 and barriers to reaching those persons for HIV services,14–16 further evaluation of the HEATED program and leveraging of ED-HTS as a mechanism to contribute to reaching global HIV control targets is warranted.

The HEATED program used multi-modal approaches with in person trainings, digital contact for sensitization and one-on-one information delivery to reach all providers in the study setting. However, feedback indicated greater sensitization was needed, suggesting that program reach could have been improved. Although, more sensitization may have been beneficial, the significant increase in ED-HTS delivery with program implementation suggests that willingness to improve services was achieved. This is also supported by patient data showing a significant increase in triage screening for interest in learning about ED-HTS options during emergency care. As triage was performed by varying staff, the significant increase in screening suggests that the HEATED program reached intended providers. However, as ensuring all stakeholders are reached in an acceptable and consistent manner is crucial to HIV program delivery,48 and given changes in staffing and policies that occur over time, it is likely the HEATED program could require more intensive and longitudinal sensitization to sustain gains in HTS impacts.

The primary outcome of effectiveness to improve ED-HTS among injured patient participants demonstrated that the HEATED program was associated with a significant increase in testing. Within the enrolled sample, one in every 18 patients was from a KP, and the majority of participants had characteristics for PPs. These data have external validity, with injury profiles from sub-Saharan Africa demonstrating high burdens among KPs,28,29 and the epidemiology of those most likely to suffer injuries being men, young people and persons who use drugs,26,27,49 supporting the importance of the ED setting for delivery of HTS. Additionally, as nearly half of enrolled patient participants had multiple KP identities and/or PP characteristics, and prior data has shown greater HIV vulnerability among such persons,50 the ED may represent an important venue to reach individuals with compounding HIV risk. Although, there was a low number of PLH identified among the patient participants, the underserved population reached through the injury focus highlights the potential for ED-HTS to pragmatically deliver services to targeted groups already in contact with healthcare. The HEATED program approach is consistent with recommendations for HIV programming for KPs, men and young adults, in improving access to services by meeting persons where they are and reducing gender barriers and stigmatization by utilizing the lens of injury which is not dependent on population identity.10,12,13 As patient ED-HTS acceptability in sub-Saharan Africa is high,23–25,51,52 further study of how to ensure systems support healthcare providers to best achieve delivery will be beneficial to build from the HEATED program results.

Effectiveness in ED-HTS was reproduced in the systems-level data with significant increases in the post-implementation periods. The increase in overall testing suggests that the HEATED program, did not redirect HTS, but rather increased services. This is evident in the observed increase in testing of men, who made up approximately 80% of injury patients in the study setting. Considering the majority of those injured globally are men,26,53 and that men in sub-Saharan Africa are inadequately tested, diagnosed later and have higher HIV-related mortality than females,13,54 the ED represents a venue deliver person-centered care in a gender-neutral setting to men, consistent with WHO recommendations.13 In the systems level data, there was a non-significant increase in PLH identified and linked to care following HEATED program implementation. The current study was not designed to assess post-testing HIV care cascade outcomes, and albeit suggestive of positive down-stream impacts of the HEATED program this is hypothesis generating, and a sufficiently powered interventional trial is needed to robustly assess this. Although achieving the UNAIDS 95-95-95 targets requires identification and linkage to treatment of PLH, status-neutral programming with interval testing and delivery of preventive interventions is also integral in epidemic control.2,55,56 As Kenya’s guidelines recommend HIV testing quarterly for KPs and every 6–12 months for PPs,8 further development of ED-HTS is not only important in completing the request first step of testing required for antiretroviral therapy (ART) or Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) provision, but would also support achieving delivery of interval testing to targeted populations.

Correlating with the significant increase in systems-level HTS, assessments of the primary intervention agents, ED-HIV services personnel, found sustained increases in assessments for constructs on program adoption and implementation. Patient participant data showed program implementation fidelity for HTS sensitization, with significantly more patients aware of services and discussing testing with ED healthcare providers in the post-implementation period. However, the linked systems-level and patient participant level data demonstrated that only 12% of persons from KPs were identified during their receipt of ED-HTS. As a component of the HEATED program was training ED-HIV services personnel on interacting with and delivering care for KPs, this suggests that the program did not sufficiently meet the provider needs and research to inform approaches to improve care for KPs from emergency care settings is needed.

With the quasi-experimental design, causality cannot be determined. Generalizability of the HEATED program in alternative settings with differing systems and resources is not known. However, as the program was designed to be pragmatic and adaptable to the = relevant needs of a service delivery point it may be impactful in other settings, which requires further study. Due to the use of standard reporting tools from systems-level data, effects on preventative services such as risk reduction counseling, condom distribution and PrEP screening were not able to be assessed across study periods. Although, the RE-AIM framework was used, qualitative data focusing on adoption and implementation would have supported a more comprehensive evaluation of the HEATED program. As well, longer-term maintenance data on sustainability, costing analyses and outcomes on linkage to treatment would strengthen the application of program. To address this, and more robustly evaluate the HEATED program, a cluster randomized trial using mixed methods with a sufficient maintenance period and costing assessment is needed.

CONCLUSIONS

The HEATED program significantly increased HTS delivery and augmented testing to underserved populations seeking emergency care. The program assessment across RE-AIM framework domains showed favorable data suggesting that further implementation study could support pragmatic service improvements for higher-risk persons already engaged with health systems as a mechanism to support advancement towards HIV control targets.

Supplementary Material

Competing interests and sources of funding:

None of the authors conflicts of interest. The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of affiliated institutions or funding bodies. ARA and the overall work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant number: K23AI145411). JSS was supported in part by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant number: R25AI140490). AO was supported in part by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (grant number: T32DA013911). DAK was supported in part by University of Washington/Fred Hutch Center for AIDS Research, an NIH-funded program (grant number: P30 AI027757).

Data availability statement:

Deidentified data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References:

- 1.UNAIDS. Confronting Inequalities - Lessons for pandemic responses from 40 years of AIDS. 2021. Accessed at: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2021-global-aids-update_en.pdf

- 2.UNAIDS. IN DANGER: UNAIDS Global AIDS Update 2022. Geneva. Accessed at: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2022-global-aids-update_en.pdf. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. IN DANGER: UNAIDS Global AIDS Update 2022. Geneva, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Syndemic Diseases Control Council. Repulic of Kenya. National Multisectoral HIV Prevention Acceleration Plan 2023–2030. August 2023. Accessed at: https://nsdcc.go.ke/download/national-multisectoral-hiv-prevention-acceleration-plan-2023-2030/. [Google Scholar]

- 5.National AIDS and STI Control Programme (NASCOP). 2022. Kenya Population-based HIV Impact Assessment (KENPHIA) 2018: Final Report. Nairobi: NASCOP. Accessed at: https://phia.icap.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/KENPHIA_Ago25-DIGITAL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Musyoki H, Bhattacharjee P, Sabin K, Ngoksin E, Wheeler T, Dallabetta G. A decade and beyond: learnings from HIV programming with underserved and marginalized key populations in Kenya. J Int AIDS Soc 2021; 24 Suppl 3(Suppl 3): e25729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National AIDS & STI Control Programme MoH. Third National Behavioural Assessment of Key Populations in Kenya: Polling Booth Survey Report. In; 2018. Accessed at: https://hivpreventioncoalition.unaids.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Third-national-behavioural-assessment-of-key-populations-in-Kenya-polling-booth-survey-report-October-2018-1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.NASCOP. Ministry of Health, National AIDS & STI Control Program. Kenya HIV Testing Services Operational Manual 2022 Edition. Nairobi, Kenya: NASCOP, November 2022. Accessed at: https://www.prepwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Kenya-HTS-Manual.pdf. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 9.UNAIDS. Blind spot: addressing a blind spot in the response to HIV. Reaching out to men and boys. 2017. Accessed at: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/blind_spot_en.pdf.

- 10.UNAIDS. New HIV Infections in Adolescents and Young People. 2021. accessed at: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/young-people-and-hiv_en.pdf.

- 11.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Kaufman M, Cain D, Jooste S. Alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review of empirical findings. Prev Sci 2007; 8(2): 141–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Consolidated Guidelines on HIV Prevention, Diagnosis, Treatment and Care for Key Populations – 2016 Update. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. DEFINITIONS OF KEY TERMS. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK379697/#. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. 2023. Men and HIV: evidence-based approaches and interventions. A framework for person-centred health services. ISBN 978–92-4–008579-4. Accessed at: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/374354/9789240085794-eng.pdf?sequence=1. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Batchelder AW, Foley JD, Wirtz MR, Mayer K, O’Cleirigh C. Substance Use Stigma, Avoidance Coping, and Missed HIV Appointments Among MSM Who Use Substances. AIDS Behav 2021; 25(5): 1454–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sereda Y, Kiriazova T, Makarenko O, et al. Stigma and quality of co-located care for HIV-positive people in addiction treatment in Ukraine: a cross-sectional study. J Int AIDS Soc 2020; 23(5): e25492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lyons C, Stahlman S, Holland C, et al. Stigma and outness about sexual behaviors among cisgender men who have sex with men and transgender women in Eswatini: a latent class analysis. BMC Infect Dis 2019; 19(1): 211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Obermeyer Z, Abujaber S, Makar M, et al. Emergency care in 59 low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ 2015; 93(8): 577–86G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith-Sreen J, Bosire R, Farquhar C, et al. Leveraging emergency care to reach key populations for ‘the last mile’ in HIV programming: a waiting opportunity. AIDS 2023; 37(15): 2421–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hodkinson PW, Wallis LA. Emergency medicine in the developing world: a Delphi study. Acad Emerg Med 2010; 17(7): 765–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang N, Stein J, Hsia RY, Maselli JH, Gonzales R. Trends and characteristics of US emergency department visits, 1997–2007. JAMA 2010; 304(6): 664–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aluisio AR, Rege S, Stewart BT, et al. Prevalence of HIV-Seropositivity and Associated Impact on Mortality among Injured Patients from Low-and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Curr HIV Res 2017; 15(5): 307–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hansoti B, Kelen GD, Quinn TC, et al. A systematic review of emergency department based HIV testing and linkage to care initiatives in low resource settings. PLoS One 2017; 12(11): e0187443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hansoti B, Stead D, Parrish A, et al. HIV testing in a South African Emergency Department: A missed opportunity. PLoS One 2018; 13(3): e0193858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waxman MJ, Kimaiyo S, Ongaro N, Wools-Kaloustian KK, Flanigan TP, Carter EJ. Initial outcomes of an emergency department rapid HIV testing program in western Kenya. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2007; 21(12): 981–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aluisio AR, Sugut J, Kinuthia J, et al. Assessment of standard HIV testing services delivery to injured persons seeking emergency care in Nairobi, Kenya: A prospective observational study. PLOS Glob Public Health 2022; 2(10): e0000526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haagsma JA, Graetz N, Bolliger I, et al. The global burden of injury: incidence, mortality, disability-adjusted life years and time trends from the Global Burden of Disease study 2013. Inj Prev 2016; 22(1): 3–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Botchey IM Jr., Hung YW, Bachani AM, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of injuries in Kenya: A multisite surveillance study. Surgery 2017; 162(6S): S45–S53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harland KK, Peek-Asa C, Saftlas AF. Intimate Partner Violence and Controlling Behaviors Experienced by Emergency Department Patients: Differences by Sexual Orientation and Gender Identification. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 2018; 36(11–12): NP6125–NP43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey : 2010 summary report. In: National Center for Injury P, Control . Division of Violence P, editors. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.National AIDS & STI Control Programme MoH. Third National Behavioural Assessment of Key Populations in Kenya: Polling Booth Survey Report, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 31.UNAIDS. Differentiated Service Delivery for HIV: a decision framework for differentiated antiretroviral therapy for key populations, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aluisio AR, Bergman J, Otieno FA, et al. “Opportunities and Challenges to Emergency Department-Based HIV Testing Services and Self-Testing Programs: A Qualitative Study of Healthcare Providers and Patients in Kenya” Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022. Dec; 9 (Suppl 2). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bergam SJ, Chen J, Kinuthia J, et al. Challenges and Facilitators for HIV Testing Services and HIV Self-Testing Programming During Emergency Care in Kenya: A Qualitative Study of Patients. Journal of Sexual heal and Aids Res 2024; 01–09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health 1999; 89(9): 1322–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pinnock H, Barwick M, Carpenter CR, et al. Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) Statement. BMJ 2017; 356: i6795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.National AIDS and STI Control Programme. “National Guidelines For HIV/STI Programming With Key Populations” 2014. Accessed at: https://hivpreventioncoalition.unaids.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/KP-National-Guidelines-2014-NASCOP-RS-ilovepdf-compressed.pdf.

- 37.Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci 2012; 7: 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci 2011; 6: 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Matthieu MM, et al. Use of concept mapping to characterize relationships among implementation strategies and assess their feasibility and importance: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) study. Implement Sci 2015; 10: 109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009; 42(2): 377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Legare F, Freitas A, Turcotte S, et al. Responsiveness of a simple tool for assessing change in behavioral intention after continuing professional development activities. PLoS One 2017; 12(5): e0176678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ayivi-Vinz G, Bakwa Kanyinga F, Bergeron L, et al. Use of the CPD-REACTION Questionnaire to Evaluate Continuing Professional Development Activities for Health Professionals: Systematic Review. JMIR Med Educ 2022; 8(2): e36948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kepper MM, Walsh-Bailey C, Brownson RC, et al. Development of a Health Information Technology Tool for Behavior Change to Address Obesity and Prevent Chronic Disease Among Adolescents: Designing for Dissemination and Sustainment Using the ORBIT Model. Front Digit Health 2021; 3: 648777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wangara AA, Hunold KM, Leeper S, et al. Implementation and performance of the South African Triage Scale at Kenyatta National Hospital in Nairobi, Kenya. Int J Emerg Med 2019; 12(1): 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.World Health Organization. AUDIT: the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: guidelines for use in primary health care. (second edition) Accessed at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MSD-MSB-01.6a. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vissoci JRN, Hertz J, El-Gabri D, et al. Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Psychometric Properties of the AUDIT and CAGE Questionnaires in Tanzanian Swahili for a Traumatic Brain Injury Population. Alcohol Alcohol 2018; 53(1): 112–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Daniel WW, editor. 7th ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1999. Biostatistics: a foundation for analysis in the health sciences. [Google Scholar]

- 48.van den Berg JJ, O’Keefe E, Davidson D, et al. The development and evaluation of an HIV implementation science network in New England: lessons learned. Implement Sci Commun 2021; 2(1): 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee JA, Ochola EO, Sugut J, et al. Assessment of substance use among injured persons seeking emergency care in Nairobi, Kenya. Afr J Emerg Med 2022; 12(4): 321–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nerlander LMC, Hoots BE, Bradley H, et al. HIV infection among MSM who inject methamphetamine in 8 US cities. Drug Alcohol Depend 2018; 190: 216–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aluisio AR, Bergam SJ, Sugut J, et al. HIV self-testing acceptability among injured persons seeking emergency care in Nairobi, Kenya. Glob Health Action 2023; 16(1): 2157540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Agutu CA, Oduor TH, Kombo BK, et al. High patient acceptability but low coverage of provider-initiated HIV testing among adult outpatients with symptoms of acute infectious illness in coastal Kenya. PLoS One 2021; 16(2): e0246444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Disease GBD, Injury I, Prevalence C. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018; 392(10159): 1789–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haas AD, Radin E, Birhanu S, et al. Prevalence of and factors associated with late diagnosis of HIV in Malawi, Zambia, and Zimbabwe: Results from population-based nationally representative surveys. PLOS Glob Public Health 2022; 2(2): e0000080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grimsrud A, Wilkinson L, Ehrenkranz P, et al. The future of HIV testing in eastern and southern Africa: Broader scope, targeted services. PLoS Med 2023; 20(3): e1004182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.WHO. Differentiated and simplified pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention Update to WHO implementation guidance. TECHNICAL BRIEF. 2022. Accessed at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240053694. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Deidentified data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.