Key Points

Question

For survivors of lung cancer, what is the association of unmet needs (physical, social, emotional, and medical) with quality of life (QOL) and financial toxicity (FT)?

Findings

In this survey study of 232 patients with non–small cell lung cancer who were alive longer than 1 year from diagnosis, unmet needs across multiple domains were associated with lower QOL and higher FT.

Meaning

These findings suggest that understanding unmet needs associated with lower QOL and higher FT is critical to developing future interventional studies aimed at improving QOL and FT among survivors of lung cancer.

This survey study examines the association of unmet physical, social, emotional, and medical needs with quality of life and financial toxicity among survivors of lung cancer.

Abstract

Importance

Despite a growing population of survivors of lung cancer, there is limited understanding of the survivorship journey. Survivors of lung cancer experience unmet physical, social, emotional, and medical needs regardless of stage at diagnosis or treatment modalities.

Objective

To investigate the association of unmet needs with quality of life (QOL) and financial toxicity (FT) among survivors of lung cancer.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This survey study was conducted at Johns Hopkins Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center thoracic oncology clinics between December 1, 2020, and September 30, 2021, to assess needs (physical, social, emotional, and medical), QOL, and FT among survivors of lung cancer. Patients had non–small cell lung cancer of any stage and were alive longer than 1 year from diagnosis. A cross-sectional survey was administered, which consisted of an adapted needs survey developed by the Mayo Survey Research Center, the Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity measure, and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30 QOL scale. Demographic and clinical information was obtained through retrospective medical record review. Data analysis was performed between May 9 and December 8, 2022.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Separate multiple linear regression models, treating QOL and FT as dependent variables, were performed to assess the adjusted association of total number of unmet needs and type of unmet need (physical, emotional, social, or medical) with QOL and FT.

Results

Of the 360 survivors of lung cancer approached, 232 completed the survey and were included in this study. These 232 respondents had a median age of 69 (IQR, 60.5-75.0) years. Most respondents were women (144 [62.1%]), were married (165 [71.1%]), and had stage III or IV lung cancer (140 [60.3%]). Race and ethnicity was reported as Black (33 [14.2%]), White (172 [74.1%]), or other race or ethnicity (27 [11.6%]). A higher number of total unmet needs was associated with lower QOL (β [SE], −1.37 [0.18]; P < .001) and higher FT (β [SE], −0.33 [0.45]; P < .001). In the context of needs domains, greater unmet physical needs (β [SE], −1.24 [0.54]; P = .02), social needs (β [SE], −3.60 [1.34]; P = .01), and medical needs (β [SE], −2.66 [0.98]; P = .01) were associated with lower QOL, whereas only greater social needs was associated with higher FT (β [SE], −3.40 [0.53]; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings of this survey study suggest that among survivors of lung cancer, unmet needs were associated with lower QOL and higher FT. Future studies evaluating targeted interventions to address these unmet needs may improve QOL and FT among survivors of lung cancer.

Introduction

Lung cancer is the third most common cancer and the leading cause of cancer death in the US.1 Lung cancer screening and novel therapeutics, including immunotherapy and targeted therapy, have led to increased 5-year survival. Despite a growing population of survivors of lung cancer, there is limited research regarding lung cancer survivorship.

Important aspects of cancer survivorship include improving survival, managing the spectrum of long-term toxic effects of cancer therapy, and understanding the consequences on patient-reported outcomes such as quality of life (QOL) and financial toxicity (FT). Survivors of all stages of lung cancer and treatment modalities experience decreased QOL compared with the general population.2,3,4 Survivors of lung cancer may experience high symptom burden, which has been associated with decreased QOL.2 The term financial toxicity describes issues caused by the cost of medical care. Survivors of lung cancer experience increased unemployment and lower income compared with the general population and a higher incidence of bankruptcy compared with survivors of other cancers.5,6,7,8,9,10 Therefore, it is essential to better understand patient-reported outcomes for survivors of lung cancer to tailor survivorship care.

The association of unmet needs with QOL and FT is yet to be reported for survivors of lung cancer. In our prior cross-sectional study,11 we characterized the physical, social, emotional, and medical needs of survivors of lung cancer diagnosed with any stage of disease. We described how survivors of lung cancer—especially those aged younger than 65 years, those with a household income of less than $75 000, and those who receive systemic therapy—experience pervasive emotional and physical needs.11 In this study, we built on our prior study to investigate the association of unmet needs with QOL and FT among survivors of lung cancer. We explored the consequences of sociodemographic and clinical factors and the association of the number of unmet needs with QOL and FT. We further identified modifiable needs that could serve as the foundation for future interventional studies aimed at improving QOL and FT.

Methods

This survey study was approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board. Survey completion served as patients’ consent to participate. The study followed the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) reporting guideline.

Study Design and Participants

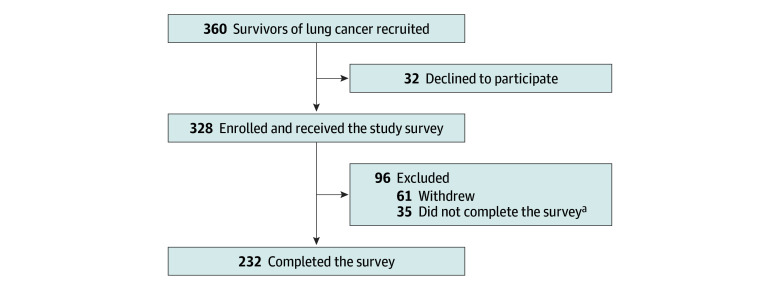

We administered a cross-sectional survey to assess needs (physical, social, emotional, and medical), QOL, and FT among survivors of lung cancer. The inclusion criteria, description of the needs assessment, and retrospective data collection and patient self-report were described previously (Figure).11 We recruited survivors of non–small cell lung cancer of any stage who were alive longer than 1 year from diagnosis to participate in this one-time survey. Although cancer survivorship begins at diagnosis, we selected 1 year as the time point because fewer than 50% of patients with lung cancer live longer than 1 year.1 Study teams identified potential participants from thoracic oncology clinics at Johns Hopkins Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, and the oncology team informed survivors of lung cancer about the study during clinic visits. Trained research assistants collected data on demographic, clinical, and cancer treatment characteristics via electronic medical record review. Participant sex and race and ethnicity were determined based on investigator observation. The investigators were the research assistants, who relied either on electronic medical record photographs or through review of the electronic medical record as assessed by the treating clinician during in-person visits. Race and ethnicity were categorized as Black, White, or other race or ethnicity (including American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander). These data were collected because there are known disparities in survival outcomes in lung cancer based on race and ethnicity; furthermore, there is a paucity of data on the lived experience of survivors of lung cancer who are not Asian or White. Sociodemographic characteristics were self-reported (eAppendix in Supplement 1). Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, our institutional review board required surveys to be administered electronically. Potential participants were called up to 3 times and excluded from further recruitment if there was no response. Survivors of lung cancer who agreed to participate were emailed an individualized link to the survey and completed the survey electronically via REDCap hosted by Johns Hopkins. The survey was completed between December 1, 2020, and September 30, 2021.

Figure. Enrollment of Survivors of Lung Cancer.

aSurveys were considered incomplete if 20% of responses or more were missing or if the global health quality of life score, financial difficulties score, or any independent variable was missing.

The survey consisted of an adapted needs survey originally developed by the Mayo Survey Research Center, the Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity (COST) measure, and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QLQ-C30 QOL questionnaire.12,13,14 The nonvalidated needs survey assesses physical, emotional, social, and medical needs using 32 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 indicates no need, and 5 indicates the highest need; higher scores reflect a higher degree of needs) (eAppendix in Supplement 1). The COST tool is a validated, 11-item patient-reported outcome measure evaluating the financial needs of patients with cancer, rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0 indicates not at all, and 4 indicates very much; lower scores reflect higher financial needs). The EORTC-QLQ-C30 is a validated, cancer-specific questionnaire comprising 30 questions over 9 domains, which assess the patient’s QOL over the previous week, rated on a 4-point Likert scale (0 indicates not at all, and 4 indicates very much). For this investigation, participant responses on the EORTC-QLQ-C30 Global Health Status/QOL scale were used to evaluate overall QOL, with higher scores reflecting higher QOL.

Statistical Analysis

Participant demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized using frequencies and percentages. Scores on the EORTC-QLQ-C30 Global Health Status/QOL scale, COST tool, and needs survey are summarized using medians and IQRs. The Wilcoxon signed rank test or Kruskal-Wallis test was used to examine univariate associations of participant demographic and clinical characteristics with EORTC-QLQ Global Health Status/QOL and COST scores. Pearson product-moment correlations were used to examine bivariate correlations between needs survey subscale scores and EORTC-QLQ-C30 Global Health Status/QOL and COST scores. Based on results of the univariate analyses, key covariates were selected to examine adjusted associations between the needs survey subscales (physical, emotional, social, and medical) and EORTC-QLQ-C30 Global Health Status/QOL scores in a multiple linear regression model. A separate multiple linear regression model was conducted using the same approach to examine associations between the needs assessment subscales and COST scores. Prior to conducting these regression models, potential multicollinearity among the physical, medical, emotional, and social needs subscales was evaluated by examining tolerance (range, 0.45-0.60) and the variance inflation factor (range, 1.68-2.21), which did not suggest multicollinearity.

We additionally evaluated the association of overall needs scores with EORTC-QLQ-C30 Global Health Status/QOL and COST scores in 2 separate multiple linear regression models (which included the same covariates as the models including the 4 needs assessment subscales). Statistical significance was assumed when 2-sided P < .05.

Statistical analyses were conducted with SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). Data analysis was performed between May 9 and December 8, 2022.

Results

Patient Characteristics and Demographics

Of the 360 survivors of lung cancer approached, 232 completed the survey and were included in this study (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). The median age of the 232 respondents was 69 (IQR, 60.5-75.0) years; most were women (144 [62.1%]) and were married (165 [71.1%]) (Table 1). Race and ethnicity was reported as Black (33 [14.2%]), White (172 [74.1%]), or other race or ethnicity (27 [11.6%]). Most survivors of lung cancer self-reported having private insurance with or without Medicare (185 [79.7%]), were retired (133 [57.3%]), had a household income of greater than $75 000 (156 [67.2%]), and had some college education or more (202 [87.1%]). A total of 27 patients (11.6%) reported a change in employment status, including loss of a job, disability, or unemployment, after diagnosis. Most patients had lung adenocarcinoma (194 [83.6%]), had stage III or IV disease at diagnosis (140 [60.3%]), and were diagnosed between 1 to less than 5 years prior to involvement in this study (166 [71.5%]). Most patients (187 [80.6%]) had received systemic therapy, around half (115 [49.6%]) were receiving active therapy at the time of the survey, and the intent of the last or active therapy was palliative for most patients (140 [60.3%]).

Table 1. Sociodemographic Factors and Treatment Historya.

| Characteristic | Value (N = 232) |

|---|---|

| Sociodemographic factor | |

| Age, y | |

| <65 | 85 (36.6) |

| ≥65 | 147 (63.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 69 (60.5-75.0) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 144 (62.1) |

| Male | 88 (37.9) |

| Race and ethnicity | |

| Black | 33 (14.2) |

| White | 172 (74.1) |

| Otherb | 27 (11.6) |

| Smoking status | |

| Current or former | 144 (62.1) |

| Never | 88 (37.9) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 165 (71.1) |

| Divorced, single, or widowed | 66 (28.5) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.4) |

| Living arrangements | |

| Married or live with friend, family, partner | 182 (78.4) |

| Single, divorced, widowed, or living alone | 48 (20.7) |

| No response | 2 (0.9) |

| Current insurance | |

| Private with or without Medicare | 185 (79.7) |

| Medicare | 40 (17.2) |

| Medicare and Medicaid | 5 (2.2) |

| No response | 2 (0.9) |

| Current employment | |

| Employed | 74 (31.9) |

| Retired | 133 (57.3) |

| Unemployed or no response | 25 (10.8) |

| Change in employment | |

| No | 178 (76.7) |

| Yes (lost job, disability, unemployment) | 27 (11.6) |

| No response | 27 (11.6) |

| Household income, $ | |

| <30 000 | 18 (7.8) |

| 30 000-75 000 | 58 (25.0) |

| >75 000 | 156 (67.2) |

| No response | 13 (5.3) |

| Education | |

| High school or less | 29 (12.5) |

| Some college or more | 202 (87.1) |

| No response | 1 (0.4) |

| Treatment history | |

| Stage at diagnosis | |

| I | 70 (30.2) |

| II | 22 (9.5) |

| III | 43 (18.5) |

| IV | 97 (41.8) |

| Tumor histology | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 194 (83.6) |

| Squamous | 23 (9.9) |

| Other | 15 (6.5) |

| ECOG-PS level at time of survey | |

| 0 | 110 (47.4) |

| 1 | 103 (44.4) |

| ≥2 | 19 (8.2) |

| Time since diagnosis, y | |

| 1 -<2 | 65 (28.0) |

| 2-<5 | 101 (43.5) |

| ≥5 | 66 (28.5) |

| Type of therapy ever received | |

| Surgery | |

| No | 107 (46.1) |

| Yes | 125 (53.9) |

| Radiation | |

| No | 97 (41.8) |

| Yes | 135 (58.2) |

| Chemotherapy | |

| No | 95 (40.9) |

| Yes | 137 (59.1) |

| Immunotherapy | |

| No | 151 (65.1) |

| Yes | 81 (34.9) |

| Targeted therapy | |

| No | 135 (58.2) |

| Yes | 97 (41.8) |

| Lines of systemic therapy | |

| 0 | 45 (19.4) |

| ≥1 | 187 (80.6) |

| Active therapy | |

| No | 117 (50.4) |

| Yes | 115 (49.6) |

| Intent of last or active therapy | |

| Curative | 92 (39.7) |

| Palliative | 140 (60.3) |

| Second primary malignancy | |

| No | 148 (63.8) |

| Yes | 84 (36.2) |

| Type of second primary malignancy (n = 84) | |

| Lung only | 8 (9.5) |

| Lung, other type, or both | 76 (90.5) |

| Primary care physician | |

| Yes | 222 (95.7) |

| No or no response | 10 (4.3) |

| Outpatient palliative care | |

| Yes | 32 (13.8) |

| No | 200 (86.2) |

| Overall QOL (1-10), median (IQR)c | 8 (6-9) |

Abbreviations: ECOG-PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; EORTC, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer; QOL, quality of life.

Unless indicated otherwise, values are expressed as No. (%) of patients.

Includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander.

Measured with the EORTC-QLQ-C30 Global Health Status/QOL scale.

QOL Analysis

The median overall EORTC Global Health Status/QOL score was 66.7 (IQR, 50.0-83.3). Univariate analysis of QOL scores revealed several demographic and clinical factors that were associated with lower QOL (eTable 2 in Supplement 1), including unemployment (median, 58.3; IQR, 50.0-66.7; P = .01) and current or former smoking status (median, 66.7; IQR, 50.0-83.3; P = .03). Ever having received radiation (median, 66.7; IQR, 50.0-83.3; P = .03), chemotherapy (median, 66.7; IQR, 50.0-83.3; P = .005), or immunotherapy (median, 66.7; IQR, 50.0-83.3; P = .02) was also associated with lower QOL (compared with never having received these treatments), but receipt of surgery or targeted therapy was not. Having received 1 or more lines of systemic therapy (compared with no systemic therapy) was associated with lower QOL (median, 66.7; IQR, 50.0-83.3; P = .02), as was receiving therapy within 1 year (vs >1 year; median, 66.7; IQR, 50.0-75.0; P = .03). Conversely and expectedly, better performance status was associated with higher QOL according to Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG-PS) (level 0: median QOL, 75.0; IQR, 58.3-83.3; level 1: median, 66.7; IQR, 50.0-75.0; and level ≥2: median, 50.0; IQR, 41.7-58.3; P < .001). Total numbers of unmet needs reported by survivors of lung cancer (r = −0.56; P < .001) and by each specific domain type (physical, r = −0.45; social, r = −0.45; emotional, r = −0.38; and medical, r = −0.41) were associated with lower QOL (all P < .001).

Multivariate analysis suggested that higher total physical needs (β [SE], −1.24 [0.54]; P = .02), medical needs (β [SE], −2.66 [0.98]; P = .01), and social needs (β [SE], −3.60 [1.34]; P = .01) were independently associated with lower QOL (Table 2). The model evaluating the association between total overall needs with QOL (rather than specific types of needs) similarly showed that higher total overall needs was independently associated with lower QOL (β [SE], −1.37 [0.18]; P < .001) (eTable 3 in Supplement 1). Post hoc pairwise median comparisons indicated significantly different adjusted mean QOL scores across all ECOG-PS levels, with the highest QOL in patients with ECOG-PS level 0 (median, 75.0; IQR, 58.3-83.3) compared with level 1 (median, 66.7; IQR, 50.0-75.0) and level 2 or greater (median, 50.0; IQR, 41.7-58.3). Post hoc pairwise median comparisons suggested that patients who had never smoked had higher QOL (median, 70.8; IQR, 54.2-83.3) than those with current or former smoking status (median, 66.7; IQR, 50.0-83.3).

Table 2. Linear Regression Models Reporting the Association Between Patient Needs and QOLa.

| Variable | Unadjusted | Adjustedb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (SE) | P value | β (SE) | P value | |

| Physical needs | −3.45 (0.45) | <.001 | −1.24 (0.54) | .02 |

| Social needs | −7.66 (1.01) | <.001 | −3.60 (1.34) | .01 |

| Emotional needs | −5.51 (0.88) | <.001 | −0.87 (1.02) | .39 |

| Medical needs | −5.91 (0.87) | <.001 | −2.66 (0.98) | .01 |

Abbreviations: COST, Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity; EORTC, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer; QOL, quality of life.

Measured with the EORTC-QLQ-C30 Global Health Status/QOL scale.

Includes the following covariates: age (≥65 or <65 years), sex (female or male), race and ethnicity (Black, White, or other race or ethnicity), income (<$30 000, $30 000-$75 000, or >$75 000), smoking status (current/former or never), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (0, 1, or ≥2), number of lines of systemic treatment (0 or ≥1), currently receiving active therapy (yes or no), intent of active or last treatment (palliative or curative), history of any radiation (yes or no), and COST financial toxicity score.

FT Analysis

The median overall COST score was 28 (IQR, 22-34). Univariate analysis of COST scores revealed several demographic and clinical factors that were associated with higher FT, including age younger than 65 years (median, 25; IQR, 20-32; P = .01), household income of less than $30 000 (median, 21; IQR, 17-26; P = .003), and unemployment (median, 24; IQR, 15-29; P = .006) (eTable 2 in Supplement 1). Ever having received surgery was associated with lower FT (median, 28; IQR, 25-34; P = .02), whereas ever having received radiation (median, 27; IQR, 20-32; P = .001) and chemotherapy (median, 27; IQR, 20-32; P = .047) was associated with higher FT. Having received 1 or more lines of systemic therapy compared with none was associated with higher FT (median, 27; IQR, 21-33; P = .001), as was receiving active therapy (median, 26; IQR, 20-32; P = .02) and therapy with palliative intent (median, 26; IQR, 20-33; P = .02). Higher total numbers of unmet needs (r = −0.42) and higher physical needs (r = −0.26), social needs (r = −0.58), emotional needs (r = −0.27), and medical needs (r = −0.31) were associated with increased FT (all P < .001).

Multivariate analysis suggested that radiation (β [SE], −2.23 [1.06]; P = .04) and total social needs (β [SE], −3.40 [0.53]; P < .001) were independently associated with higher FT (Table 3 and eTable 4A in Supplement 1). The model evaluating the association between total overall needs (rather than specific domains of needs) suggested that income (<$30 000 vs >$75 000: β [SE], −8.23 [4.75]; $30 000-$75 000 vs >$75 000: β [SE], −2.60 [2.79]; both P < .001), radiation (β [SE], −2.57 [2.52]; P = .02), and total number of needs (β [SE], −0.33 [0.45]; P < .001) were each independently associated with higher FT (eTable 4B in Supplement 1).

Table 3. Linear Regression Models Reporting the Association Between Patient Needs and Financial Toxicitya.

| Variable | Unadjusted | Adjustedb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (SE) | P value | β (SE) | P value | |

| Physical needs | −0.84 (0.2) | <.001 | 0.07 (0.23) | .77 |

| Social needs | −4.14 (0.39) | <.001 | −3.4 (0.53) | <.001 |

| Emotional needs | −1.61 (0.38) | <.001 | 0.09 (0.43) | .84 |

| Medical needs | −1.90 (0.38) | <.001 | −0.11 (0.42) | .79 |

Measured with the Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity tool.

Includes the following covariates: age (≥65 or <65 years), sex (female or male), race and ethnicity (Black, White, or other race or ethnicity), income (<$30 000, $30 000-$75 000, or >$75 000), smoking status (current/former or never), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status level (0, 1, or ≥2), number of lines of systemic treatment (0 or ≥1), currently receiving active therapy (yes or no), intent of active or last treatment (palliative or curative), history of any radiation (yes or no), and global quality of life score.

Discussion

Survivors of lung cancer experience unmet physical, social, emotional, and medical needs regardless of stage at diagnosis or treatment modalities. In this study, we investigated the sociodemographic factors and unmet needs of survivors of lung cancer associated with lower QOL and higher FT.

Unmet Needs and QOL

Higher total number of unmet needs and, in particular, higher unmet physical, social, and medical needs were independently associated with lower QOL among survivors of lung cancer. An older, population-based study in Denmark reported a similar association of unmet needs and lower QOL across multiple cancers.15 Although the prior study was performed in a patient population including only 5% with lung cancer and used a different needs assessment, our findings further support the interplay between unmet needs and lower QOL.

The most common physical needs of our cohort (reported by >40.0%) included fatigue, sleep disturbances, memory and concentration, weakness, trouble breathing, weight changes, hair or skin changes, balance and mobility, neuropathy, and bowel or bladder changes.11 Our findings are similar to a study focused on QOL among survivors of lung cancer, which reported the highest symptom scores for dyspnea, fatigue, cough, and insomnia associated with lower QOL compared with the general population.2 Higher dyspnea in that cohort was noted in patients with current smoking status, which may explain our findings of current or former smoking status associated with lower QOL. Similarly, we observed that worse performance status was independently associated with lower QOL, whereas Hechtner et al2 noted higher QOL in patients with more physical activity.

Higher unmet social and medical needs were associated with lower QOL in our cohort. Social needs included managing daily activities, financial concerns, returning to work, and health insurance. Medical needs included finding support resources, keeping primary care physicians informed of cancer care, and knowing who to call for medical problems, follow-up appointments, and tests. The association between unmet social and medical needs and lower QOL highlights the potential of a multidisciplinary team assisting with patients’ financial concerns and care coordination to improve QOL.

Unexpectedly, emotional needs were not independently associated with QOL. Emotional needs included defining a new sense of normal, living with uncertainty, fear of recurrence, and managing difficult emotions. This finding was surprising because psychologic distress is associated with lower QOL in the general cancer survivor population and survivors of lung cancer, and emotional needs were the most common unmet needs in our cohort.11,15 However, we used a single global QOL score, and it is possible that use of a different QOL tool would have a different outcome.16,17

Although our findings do not elucidate the causal relationship between unmet needs and QOL, we identified potentially modifiable factors that can be explored for future targeted intervention to improve QOL. For example, tobacco cessation has been reported to improve QOL in the general population and may have a similar outcome for survivors of lung cancer.18 Pulmonary rehabilitation also has the potential to improve QOL among survivors of lung cancer. For example, a prior study among patients with non–small cell lung cancer demonstrated that pulmonary rehabilitation was associated with significantly improved pulmonary function and 6-minute walk test scores and decreased dyspnea in both patients with and without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.19 Finally, despite 140 of 232 patients (60.3%) in our study having stage III or IV disease at diagnosis, only 32 (13.8%) sought outpatient palliative care at least once. Early palliative care is recommended for patients with advanced cancer because it has been shown to improve symptom burden, QOL, and overall survival including, in those with lung cancer.20,21,22 In the era of immunotherapy, targeted therapies, and extended survival, the timing of palliative care integration in the long-term management of lung cancer is evolving and merits further study.23

Unmet Needs and FT

Radiation therapy and social needs were independently associated with FT among survivors of lung cancer. Our analysis of the total number of unmet needs, rather than the individual domains of needs, revealed that income, radiation therapy, and total number of needs were independently associated with FT. This finding suggests that the overall burden of total unmet needs may play a larger role in FT than individual need domains. Multiple studies have reported lower rates of survivors of lung cancer returning to work compared with survivors of other cancers globally.5,6,7,8,9 We have a limited understanding of expenses for patients or how lung cancer diagnosis and treatments affect long-term financial considerations, such as income and employment status, for survivors of lung cancer and their caregivers. As treatments are improving and allowing patients to live longer, the costs of therapies are also soaring; therefore, it is crucial to understand their implications on long-term patient-reported outcomes for survivors of lung cancer.

Prior studies have evaluated FT during lung cancer care. To our knowledge, this study is one of the first to report on FT specifically among survivors of lung cancer, many of whom have completed active therapy. Our findings support the pervasive nature of FT along the cancer continuum, with similar risk factors during active treatment and in survivorship. Friedes et al24 prospectively assessed FT using the COST tool in patients with stage II to IV lung cancer at diagnosis and at 6-month follow-up. Similar to our findings, income of less than $40 000 at diagnosis was associated with FT, as were having less than a month of savings and not being able to afford basic necessities. Our study describes the association between social needs and FT among patients who were alive longer than 1 year from diagnosis, highlighting the long-lasting consequences of FT.

Potential interventions to mitigate FT include multidisciplinary financial navigation by financial counselors, social workers, or nurse navigators focused on financial education and assistance and health insurance enrollment.25 In a pilot study at the North Carolina Cancer Hospital, patients were screened for FT with the COST tool; 55 patients with a COST score of less than 22 were enrolled.26 The intervention involved an intake assessment, one-on-one consultation with a financial counselor or social worker to identify specific needs, and follow-up at 2-week intervals. The pilot study demonstrated significant improvement in FT with multidisciplinary financial navigation.26 Incorporating financial navigation into care for survivors of lung cancer with attention to specific needs, including return to work and health insurance, should be evaluated as a strategy to mitigate FT.

Types of therapy may be associated with FT. For example, radiation was independently associated with higher FT, even after accounting for other key demographic and clinical factors as well as unmet needs. In our univariate analysis, surgery was associated with lower FT, possibly due to these patients having early-stage disease treated with curative intent. We did not identify that immunotherapy or targeted therapy was associated with FT, but it was difficult to differentiate systemic treatment types because many patients received multiple lines or types of systemic therapy. However, costs of therapies should be evaluated further because many survivors of lung cancer receive immunotherapy or targeted therapy indefinitely, and the cumulative FT needs to be understood.

Lung Cancer Survivorship Framework

Based on our findings of unmet needs and potential interventions to improve QOL and FT and on prior research including recommendations per the National Comprehensive Cancer Network survivorship guidelines, we propose a survivorship framework adapted from Nekhlyudov et al27 for survivors of lung cancer (eFigure in Supplement 1).11,19,20,21,22,23,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37 Our framework includes management of physical and psychosocial effects, surveillance for recurrence and new cancers, management of chronic medical conditions, health promotion and disease prevention, and health care delivery with outcomes including QOL, emergency services and hospitalizations, costs, and mortality. The goal of our framework adapted for survivors of lung cancer is to provide a foundation for comprehensive lung cancer survivorship care and further research.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. Our survey was electronic due to the COVID-19 pandemic, selecting for patients with internet access and literacy. Most patients had a household income of greater than $75 000, had some college education or more, and had a primary care physician; thus, these findings may not be generalizable. Likewise, because most of our patients had private insurance with or without Medicare, the evaluation of FT may not be generalizable. Further studies warrant sampling of a broader study population. Our study is cross-sectional and not longitudinal and thus does not capture the patient experience over time. Additionally, our study did not assess QOL or FT from the caregiver perspective, which is critical to comprehensively understanding the survivorship experience.

Conclusions

In this survey study, unmet needs across multiple domains were associated with lower QOL and higher FT among survivors of lung cancer. We identified unmet needs and sociodemographic characteristics that are potentially modifiable, such as patient symptoms (physical needs), care coordination (medical needs), financial concerns (social needs), and smoking and functional status. Identification of modifiable needs that are associated with lower QOL and higher FT is crucial for informing interventional studies and survivorship care plans. Longitudinal assessment is necessary because patients’ unmet needs may vary throughout the continuum of care. Future directions include using multidisciplinary teams to address unmet needs through palliative and survivorship care models and financial navigation. Overall, our findings suggest that unmet needs are associated with QOL and FT and highlight the potential for targeted interventions that address these needs to improve QOL and FT among survivors of lung cancer.

eAppendix. Needs Assessment Survey

eTable 1. Respondents With Completed vs Uncompleted Surveys

eTable 2. Univariate Analysis of Unmet Needs and Quality of Life (QOL) and Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity (COST)

eTable 3. Multivariate Analysis of Quality of Life (QOL) and Total Needs

eTable 4. Multivariate Analysis of Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity (COST) and Needs

eFigure. Lung Cancer Survivorship Care Framework

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute . Cancer stat facts: cancer of the lung and bronchus. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Accessed August 20, 2023. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/lungb.html

- 2.Hechtner M, Eichler M, Wehler B, et al. Quality of life in NSCLC survivors—a multicenter cross-sectional study. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(3):420-435. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rauma V, Sintonen H, Räsänen JV, Salo JA, Ilonen IK. Long-term lung cancer survivors have permanently decreased quality of life after surgery. Clin Lung Cancer. 2015;16(1):40-45. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2014.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ran J, Wang J, Bi N, et al. Health-related quality of life in long-term survivors of unresectable locally advanced non–small cell lung cancer. Radiat Oncol. 2017;12(1):195. doi: 10.1186/s13014-017-0909-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim YA, Yun YH, Chang YJ, et al. Employment status and work-related difficulties in lung cancer survivors compared with the general population. Ann Surg. 2014;259(3):569-575. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318291db9d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rashid H, Eichler M, Hechtner M, et al. Returning to work in lung cancer survivors—a multi-center cross-sectional study in Germany. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(7):3753-3765. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05886-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Earle CC, Chretien Y, Morris C, et al. Employment among survivors of lung cancer and colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(10):1700-1705. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.7411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torp S, Nielsen RA, Fosså SD, Gudbergsson SB, Dahl AA. Change in employment status of 5-year cancer survivors. Eur J Public Health. 2013;23(1):116-122. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckr192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Syse A, Tretli S, Kravdal Ø. Cancer’s impact on employment and earnings—a population-based study from Norway. J Cancer Surviv. 2008;2(3):149-158. doi: 10.1007/s11764-008-0053-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, et al. Financial insolvency as a risk factor for early mortality among patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(9):980-986. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.6620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsu ML, Guo MZ, Olson S, et al. Lung cancer survivorship: physical, social, emotional, and medical needs of non–small cell lung cancer survivors. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2024;22(1D):e237072. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2023.7072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ness S, Kokal J, Fee-Schroeder K, Novotny P, Satele D, Barton D. Concerns across the survivorship trajectory: results from a survey of cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013;40(1):35-42. doi: 10.1188/13.ONF.35-42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Wroblewski K, et al. Measuring financial toxicity as a clinically relevant patient-reported outcome: the validation of the Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity (COST). Cancer. 2017;123(3):476-484. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Osoba D, Aaronson N, Zee B, Sprangers M, te Velde A; The Study Group on Quality of Life of the EORTC and the Symptom Control and Quality of Life Committees of the NCI of Canada Clinical Trials Group . Modification of the EORTC QLQ-C30 (version 2.0) based on content validity and reliability testing in large samples of patients with cancer. Qual Life Res. 1997;6(2):103-108. doi: 10.1023/A:1026429831234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hansen DG, Larsen PV, Holm LV, Rottmann N, Bergholdt SH, Søndergaard J. Association between unmet needs and quality of life of cancer patients: a population-based study. Acta Oncol. 2013;52(2):391-399. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2012.742204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schurr T, Loth F, Lidington E, et al. ; European Organisation for Research, Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Group (EORTC QLG) . Patient-reported outcome measures for physical function in cancer patients: content comparison of the EORTC CAT Core, EORTC QLQ-C30, SF-36, FACT-G, and PROMIS measures using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2023;23(1):21. doi: 10.1186/s12874-022-01826-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luckett T, King MT, Butow PN, et al. Choosing between the EORTC QLQ-C30 and FACT-G for measuring health-related quality of life in cancer clinical research: issues, evidence and recommendations. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(10):2179-2190. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piper ME, Kenford S, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Smoking cessation and quality of life: changes in life satisfaction over 3 years following a quit attempt. Ann Behav Med. 2012;43(2):262-270. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9329-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glattki GP, Manika K, Sichletidis L, Alexe G, Brenke R, Spyratos D. Pulmonary rehabilitation in non–small cell lung cancer patients after completion of treatment. Am J Clin Oncol. 2012;35(2):120-125. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e318209ced7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733-742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(1):96-112. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.1474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dans M, Kutner JS, Agarwal R, et al. NCCN Guidelines® insights: palliative care, version 2.2021. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19(7):780-788. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2021.0033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Temel JS, Petrillo LA, Greer JA. Patient-centered palliative care for patients with advanced lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(6):626-634. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.01710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friedes C, Hazell SZ, Fu W, et al. Longitudinal trends of financial toxicity in patients with lung cancer: a prospective cohort study. JCO Oncol Pract. 2021;17(8):e1094-e1109. doi: 10.1200/OP.20.00721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith GL, Banegas MP, Acquati C, et al. Navigating financial toxicity in patients with cancer: a multidisciplinary management approach. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(5):437-453. doi: 10.3322/caac.21730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wheeler SB, Rodriguez-O’Donnell J, Rogers C, et al. Reducing cancer-related financial toxicity through financial navigation: results from a pilot intervention. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020;29(3):694. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-20-0067 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nekhlyudov L, Mollica MA, Jacobsen PB, Mayer DK, Shulman LN, Geiger AM. Developing a quality of cancer survivorship care framework: implications for clinical care, research, and policy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(11):1120-1130. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djz089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):557-565. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.0830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Basch E, Schrag D, Henson S, et al. Effect of electronic symptom monitoring on patient-reported outcomes among patients with metastatic cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2022;327(24):2413-2422. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.9265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Denis F, Basch E, Septans AL, et al. Two-year survival comparing web-based symptom monitoring vs routine surveillance following treatment for lung cancer. JAMA. 2019;321(3):306-307. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.18085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dai W, Feng W, Zhang Y, et al. Patient-reported outcome-based symptom management versus usual care after lung cancer surgery: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(9):988-996. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.01344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . Non–small cell lung cancer. Version 3.2023. June 19, 2023. Accessed August 10, 2023. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl_blocks.pdf

- 33.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . Survivorship. Version 1.2023. March 24, 2023. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/survivorship.pdf

- 34.American Lung Association . Addressing the stigma of lung cancer. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.lung.org/getmedia/54eb0979-4272-4f43-be79-9bef36fab30b/ALA-Stigma-of-LC-2020-V1.pdf

- 35.Powell HA, Iyen-Omofoman B, Baldwin DR, Hubbard RB, Tata LJ. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and risk of lung cancer: the importance of smoking and timing of diagnosis. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8(4):e34-e35. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31828950e3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu VW, Zhao JJ, Gao Y, et al. Thromboembolism in ALK+ and ROS1+ NSCLC patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lung Cancer. 2021;157:147-155. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2021.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gupta A, Eisenhauer EA, Booth CM. The time toxicity of cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(15):1611-1615. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.02810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Needs Assessment Survey

eTable 1. Respondents With Completed vs Uncompleted Surveys

eTable 2. Univariate Analysis of Unmet Needs and Quality of Life (QOL) and Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity (COST)

eTable 3. Multivariate Analysis of Quality of Life (QOL) and Total Needs

eTable 4. Multivariate Analysis of Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity (COST) and Needs

eFigure. Lung Cancer Survivorship Care Framework

Data Sharing Statement