Abstract

Background

The clinical significance of adoptive tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) therapy has been demonstrated in many clinical trials. We analyzed the in vitro reactivity of cultured TILs against autologous breast cancer cells.

Methods

TILs and cancer cells were cultured from 31 breast tumor tissues. Reactivity of TILs against cancer cells was determined by measuring secreted interferon-gamma. Expression levels of epithelial markers, major histocompatibility complex molecules, and programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) in cancer cells, and T cell markers (memory, T cell activation and exhaustion, and regulatory T cell markers) in expanded TILs were analyzed and compared between the reactive and non-reactive groups.

Results

In seven cases, TILs showed reactivity to autologous cancer cells. Six of these cases were associated with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). All reactive TNBCs were derived from surgical specimens after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC). Higher expression of Ki67 in tumor tissues and lower expression of PD-L1 in cultured cancer cells were associated with reactivity. Proliferation of reactive TILs was high. High proportions of T cells and PD-1+CD4+ and PD1+CD8+ T cells were associated with reactivity in TNBC cases, while other activation or exhaustion markers were not.

Conclusion

TILs from approximately half the TNBC cases with NAC showed reactivity against autologous cancer cells. The proportion of PD-1+ T cells was higher in the reactive group. Adoptive TIL therapy combined with PD-1 inhibitors might be promising for TNBC patients with residual tumors after NAC.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00262-020-02633-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, Breast cancer, Adoptive cell therapy, Reactivity

Introduction

Breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease with various biologic, pathologic, and clinical features. Approximately 70% of breast cancer cases are hormone receptor-positive (HR+) tumors that express estrogen receptor (ER) and or progesterone receptor (PR) [1]. Hormone therapy is considered the most effective treatment for these patients. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive (HER2+) breast cancer comprises 15–20% of cases, and targeted therapies such as trastuzumab and pertuzumab are effective. Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is a subtype that accounts for approximately 15% of all breast cancers. Since TNBC does not express hormone receptors or HER2, targeted therapies such as tamoxifen (used for HR + breast cancer) or trastuzumab (used for HER2 + breast cancer) are not available. Only chemotherapy is used for TNBC. The prognosis of patients not responding to chemotherapy is very poor. Thus, effective therapeutic agents are needed for TNBC patients.

Cancer immunotherapy induces an immune response to cancer cells through immune cell stimulation. Durable benefit and complete responses are achieved in certain groups of patients. Cancer immunotherapies include anti-cancer vaccines, checkpoint inhibitors, and adoptive cell transfer (ACT). Clinical trials of ACT with lymphokine-activated killer cells [2, 3], genetically engineered T cells [4, 5], and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) [6] have assessed in breast cancer.

TILs are lymphocytes that accumulate around cancer cells. Unlike peripheral blood lymphocytes, a high proportion of T cells have a memory phenotype [7]. TILs are present in most breast cancers. More TILs are observed in TNBC, compared with HR+ breast cancer, although the numbers of TILs vary widely in patients [8]. Increased levels of TILs are reportedly associated with better response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) in all breast cancer subtypes. In addition, TNBC and HER+ breast cancer patients harboring more TILs can survive longer.

The most successful clinical trial of adoptive TIL therapy revealed that 22% (20/93) of melanoma patients receiving expanded TILs from autologous cancer showed complete remission without recurrence in 20% (19/93) patients within 5–10-years of follow-up [9]. The therapeutic effect of TIL has been consistently demonstrated in preclinical and clinical studies in various cancers including lung cancer, cervical cancer, ovarian cancer, and colorectal cancer [10–13]. Recently, the adoptive transfer of autologous mutation-specific TILs in combination with pembrolizumab successfully regressed metastatic ER+ breast cancer in a patient [6]. However, this is the only study reported on breast cancer. Further demonstration of the efficacy of adoptive TIL therapy in breast cancer is needed.

Previously, we described the potential properties of TILs as a source of ACT for breast cancer [14]. Some, but not all, cases of TILs from breast cancer produced interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) when interacting with autologous cancer cells and controlled tumor growth in patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models. The characteristics of TILs and cancer cells that influenced the immune response are still unclear, which hinders the refinement of TIL therapy. Herein, we investigated the efficacy of ex vivo-expanded TILs to autologous tumor cells derived from patients with various types of breast cancer and analyzed the factors associated with in vitro reactivity of expanded TILs.

Materials and methods

Patient samples

The study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center (IRB#2015–0438). We selected 31 breast cancer samples that were successfully cultured for both TILs and cancer cells, of which twenty-four samples were collected previously [14] and seven were newly obtained (Supplementary Table S1). The percentage of TILs was estimated as reported previously [15, 16]. Lymphoid aggregation with vessels showing features of high endothelial venules (plump, cuboidal endothelial cells) with or without germinal centers was considered a tertiary lymphoid structure (TLS). The degree of TLS was determined as 0 (none), 1 (little), 2 (moderate), and 3 (abundant) [17]. Full available sections were evaluated for histological subtype and grade, tumor size, pT stage, pN stage, and lymphovascular invasion. Immunohistochemistry was performed to determine the breast cancer subtypes as described previously [14]. ER and PR levels were regarded as positive when > 1% of tumor nuclei were stained. HR+ tumors were defined as ER+ and/or PR+. HER2+ tumors were defined as those with immunohistochemistry scores ≥ 3 or were determined by gene amplification using silver in situ hybridization. Histologic types were defined according to the 2012 WHO classification, and histological grades were evaluated using the modified Bloom–Richardson classification.

Cell culture

TILs were isolated from tumor tissues and expanded as previously described [14]. Briefly, breast cancer tissues were minced into 1-mm-diameter pieces and plated (two pieces per well) in a 24-well plate containing 2 mL of TIL culture medium (RPMI 1640 medium; Life Technologies, New York, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Corning, New York, NY, USA), 1 × ZellShield, 50 nM 2-mercaptoethanol (Life Technologies), and 1000 IU/mL human recombinant interleukin-2 (hrIL-2; Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), and incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 14 days. Half of the TIL culture medium was replaced every 2 or 3 days, and the cells were divided into two wells when the color of the medium turned from reddish to yellow. After 14 days, the TILs were cryopreserved until further experimentation.

For further rapid expansion (REP), TILs were cultured with irradiated (50 Gy) allogeneic peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from three healthy donors in REP medium (50% RPMI 1640 and 50% AIM-V medium; Life Technologies) supplemented every 2 or 3 days with 10% FBS, 1 × ZellShield, 2000 IU/mL hrIL-2, and 30 ng/mL human anti-CD3 antibody (OKT3, Miltenyi Biotec). After 14 days, the post-REP TILs were collected and cryopreserved until further experimentation.

For primary cancer cell culture, breast cancer tissues were digested as previously described [14]. Dissociated cells were cultured 1:1 in DMEM/F12 (Life Technologies) supplemented with 2% FBS, 5 ng/mL human recombinant epidermal growth factor (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 0.3 μg/mL hydrocortisone, 0.5 ng/mL cholera toxin, 5 nM 3,3′,5-triiodo-L-thyronine, 0.5 nM β-estradiol, 5 μM isoproterenol hydrochloride, 50 nM ethanolamine, 50 nM O-phosphorylethanolamine (all from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 1 × insulin/transferrin/selenium, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin on 100 mm collagen I-coated plates (Corning) at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator until confluent. The cells were sub-cultured at least twice before cryopreservation.

IFN-γ production

To investigate TIL reactivity against autologous cancer cells, 4 × 105 TILs were co-cultured with 1 × 105 autologous breast cancer cells in 96-well plates for 24 h. The supernatant was collected, and the IFN-γ produced by TILs was quantified with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Koma Biotech, Seoul, Korea).

Flow cytometry

Antibodies used are listed in Supplementary Table S2. To analyze the molecules expressed on cell surfaces, cells were stained with antibodies for 30 min at 4 °C in the dark. After washing with fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer, the cells were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole solution to distinguish dead cells. For intracellular staining, the cells were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized using 90% methanol. The cells were washed and stained with antibodies at 4 °C in the dark. After staining, the cells were washed and resuspended with FACS buffer. Flow cytometry was performed using the FACS Canto II device (BD Biosciences, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR, USA).

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software version 20 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare differences between two independent groups. Correlation was assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation analysis. All tests were two-sided, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinicopathologic characteristics of patients

Breast cancer tissues obtained from 31 patients (13 h+/HER2−, one HR−/HER2+, and 17 TNBC; Table 1) were used to isolate TILs and cancer cells. All tumor samples were derived from the breast, except one from a lymph node with breast cancer metastasis. Nineteen patients underwent NAC prior to surgery (NAC group), while 12 did not (non-NAC group). The NAC samples were resistant to systemic therapy. Median tumor size was 2.4 cm (range, 0.8–14.6 cm).

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic characteristics of patients

| Clinicopathologic variables |

Primary tumor | Primary tumor | Metastasis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Did not receive neoadjuvant therapy |

Received neoadjuvant therapy |

Lymph node | |

| (n = 12) | (n = 18) | (n = 1) | |

| Age (years) | |||

| Median (range) | 43 (33–61) | 47 (34–88) | 62 |

| Tumor size (cm) | |||

| Median (range) | 2.1 (0.8–3.2) | 3.7 (1.5–14.6) | 2.5 |

| Subtype | |||

| HR+/HER2− | 5 (42%) | 8 (44%) | 0 (0%) |

| HR+/HER2+ | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| HR−/HER2+ | 1 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| TNBC | 6 (50%) | 10 (56%) | 1 (100%) |

| Histological type | |||

| IDC, NOS | 12 (100%) | 18 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| Metaplastic carcinoma | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) |

| Histological grade | |||

| 2 | 3 (25%) | 4 (22%) | 1 (100%) |

| 3 | 9 (75%) | 14 (78%) | 0 (0%) |

| LVI | |||

| Absent | 10 (83%) | 5 (28%) | NA |

| Present | 2 (17%) | 13 (72%) | |

| TNM stage | |||

| I | 5 (42%) | 2 (11%) | NA |

| II | 7 (58%) | 8 (44%) | |

| III | 0 (0%) | 8 (44%) | |

| IV | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Miller–Payne grade | |||

| 1 | 8 (44%) | ||

| 2 | 6 (33%) | ||

| 3 | 4 (22%) | ||

| RCB class | |||

| II | 7 (39%) | ||

| III | 11 (61%) | ||

HR hormone receptor, HER2 human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive, IDC invasive ductal carcinoma, LVI lymphovascular invasion, NA not available, NOS not otherwise specified, RCB residual cancer burden, TNBC triple-negative breast cancer

Expansion of TILs from cancer tissues

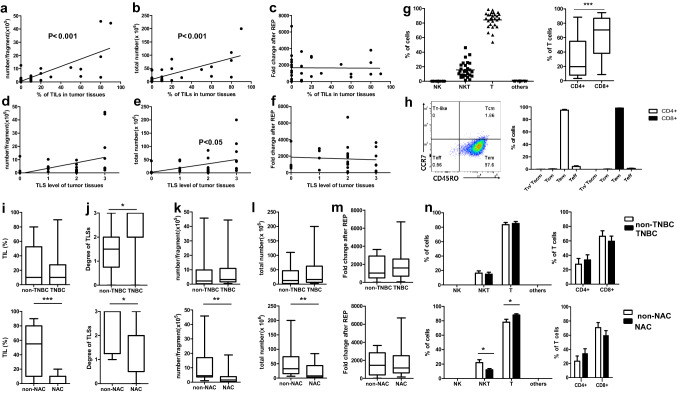

TILs in ex vivo cultures are derived from within tumors and tumor-adjacent tissues. TIL and TLS levels were estimated by hematoxylin and eosin staining of cancer tissue sections. Varied levels of TILs (HR+/HER2− and HR−/HER2+: median, 10%; range, 0–80%; TNBC: median, 10%; range, 0–90%) and TLS were observed. Culturing yielded more than 1 × 103 immune cells per tumor fragment (median, 3 × 105; range, 4.0 × 103 to 4.6 × 106) and 1 × 105 cells per tumor (median, 148 × 105; range, 1–2000 × 105). As expected, the numbers of cultured TILs were positively correlated with the levels of TILs (Fig. 1a, b) and TLS score (Fig. 1d, f) histologically estimated from cancer tissue sections. For functional analysis and characterization, the TILs were further expanded for 2 weeks with hrIL-2, allogeneic PBMCs, and anti-human CD3 antibody. Median fold-change of expanded T cells from the initial number of TILs was 1205 (range, 13–6700). Unlike the initially cultured TILs, the fold-change of REP TILs was not significantly correlated with TIL and TLS levels of tumor tissues (Fig. 1c, f). We also previously reported the proliferation ability of TILs from more than 100 breast cancer tissues [14]. Therefore, it is expected that TILs from breast cancer patients could be expanded to a sufficient number for ACT, which usually involves 1 × 109–1 × 1011 cells.

Fig. 1.

Characteristics of expanded TILs derived from breast cancer tissues according to TNBC and NAC. Correlation between tissue levels of TIL and TLS and the number of cultured TILs per fragment (a, d), per sample (b, e), and the fold-change after REP (c, f). Composition of immune cells (g) and T cell subsets (h) of REP TILs, including naïve like T cells (Tn-like), central memory T cells (Tcm), effector memory T cells (Tem), and effector T cells (Teff). Comparisons of levels of TILs (i) and TLS (j) in tumor tissues, number of expanded TILs per fragment (k), total number (l), fold-change after REP (m), and immune cell composition of REP TILs (n) between TNBC and non-TNBC samples, and NAC and non-NAC samples including HR+/HER2+ patients. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Characteristics of expanded TILs

Next, we analyzed the composition of immune cells within the REP TILs. T cells (CD3+CD56−) were predominant (median, 86.3%; range, 53.7–98.7%; Fig. 1c). In this study, we designated CD3+CD56+ cells as natural killer T (NKT)-like cells because cytotoxic T cells as well as NKT cells express CD56 [18]. The proportion of NKT-like cells varied among samples (median, 13.7%; range, 1.3–46.2%). The proportions of natural killer (NK) cells (CD3-CD56+) and other types of cells (CD3−CD56−) were < 0.1% in all REP TILs (Fig. 1g). CD8+ T cells (median, 70.7%; range, 8.6–94.7%) were more abundant than CD4+ T cells (median, 19.6%; range, 3.2–88.4%) in 64% of REP TILs. In all REP TILs, the majority of the CD4+ and CD8+ T cells showed effector memory phenotypes (CD45RO+, CCR7−, Fig. 1h). Since the degree of TILs and TLSs and the characteristics of cultured TILs may vary depending on the subtype of cancer cells and chemotherapy, we compared these features between groups. There was only one sample with the HR−/HER2+ subtype, so we divided the tumors into two groups: non-TNBC and TNBC. The degree of TLSs was significantly higher in the TNBC group (p = 0.036). However, the levels of TILs in the tumor tissues and features of cultured TILs were not significantly different between the TNBC and non-TNBC groups (Fig. 1i–n). The levels of TILs and TLSs in the tumor tissues and the number of 2 weeks cultured TILs were significantly lower in the NAC group than in the non-NAC group (Fig. 1i–l). As expected, cancer cells and immune cells in the tumor tissues were affected by chemotherapy, as were the compositions of expanded TILs. No significant differences were evident in the fold-change of REP TILs between the NAC and non-NAC groups.

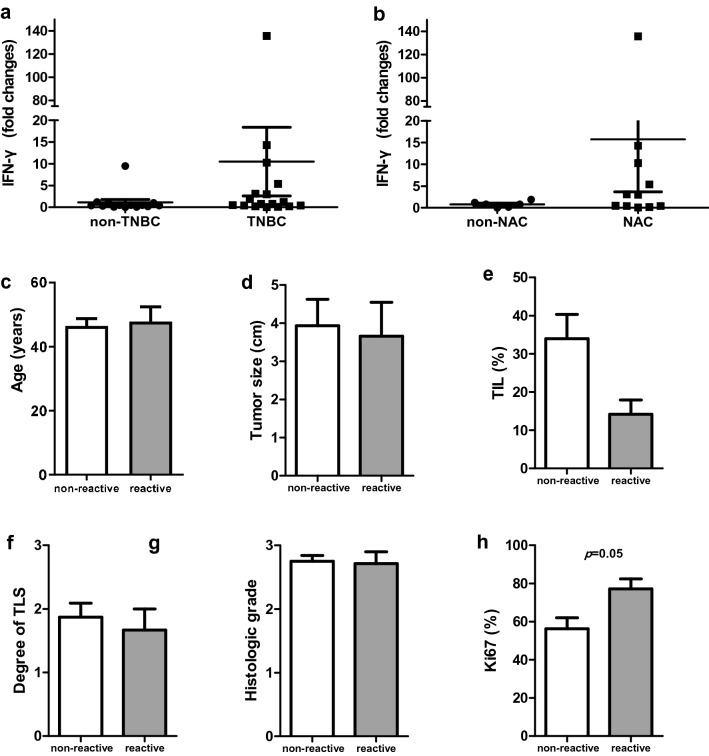

Reactivity of expanded TILs against cancer cells

Expanded TILs were co-cultured with autologous primary cancer cells for 24 h and IFN-γ secretion was analyzed. Reactivity to autologous tumor cells was defined as IFN-γ secretion more than twice that in control cultures without cancer cells. Seven cases of TILs displayed significant reactivity upon autologous cancer cell interaction (median fold-change, 0.5; range, 0–135.8 of total samples, median fold-change, 9.5; range, 3.0–135.8 of reactive TILs; Fig. 2a, b). Most of the reactive TILs were from TNBC (6/7). All TNBCs showing in vitro reactivity were derived from resection specimens in the NAC group (six of 11 cases, with five cases derived from primary tumors and one case derived from metastatic lymph node). The remaining case with in vitro reactivity was derived from HER2+ breast cancer without NAC. Levels of Ki67 were higher in the reactive group than in the non-reactive group (p = 0.05). Other clinicopathologic factors were not significantly different between the reactive and non-reactive groups (Fig. 2c–l).

Fig. 2.

Reactivity of REP TILs against autologous cancer cells and clinicopathologic factor comparison according to reactivity. Comparison of IFN-γ production of expanded TILs after co-culture with autologous cancer cells between TNBC and non-TNBC samples (a) and between NAC and non-NAC samples (b). Comparison of age (c), tumor size (d), TIL level (e), TLS level (f), histologic grade (g), and percentages of Ki67 (h) between non-reactive (white bar) and reactive (grey bar) groups

Cancer factors associated with in vitro reactivity

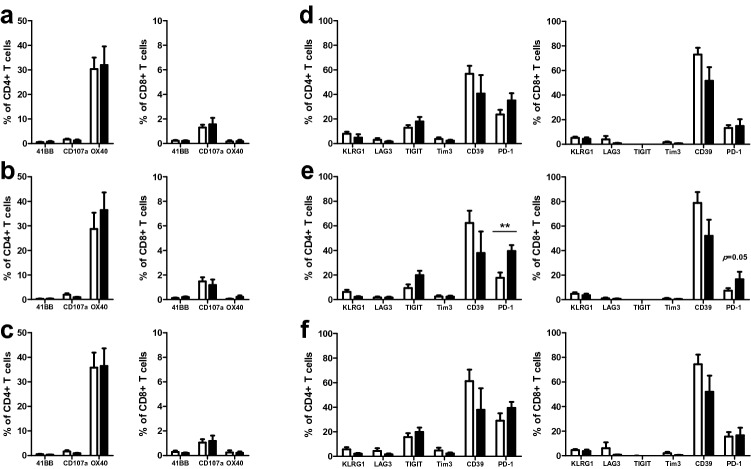

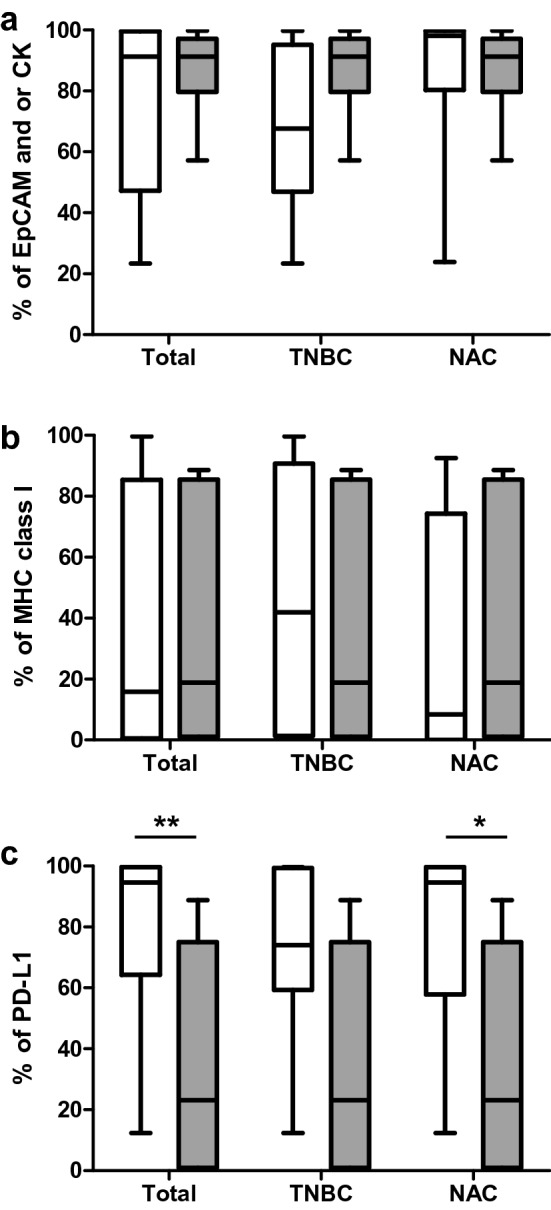

To characterize the cultured cancer cells, the morphology and expression levels of epithelial cell markers, such as epithelial cell adhesion molecules (EpCAMs) and cytokeratins (CKs), were evaluated with flow cytometry. Although EpCAM and CK positivity (percentage of cells expressing EpCAM, CK, or both) were significantly higher in the NAC group (p = 0.022, Supplementary Fig. S1d), their expression levels were not significantly associated with reactivity in the total, TNBC, and NAC samples (Fig. 3a). Cancer cells down-regulate major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules to evade tumor surveillance by immune cells. Accordingly, the expression level of MHC class I molecules was < 1% in 28% (7/25) of cancer cells (Supplementary Fig. S1b). However, down-regulation of MHC class I was not correlated with reactivity (Fig. 3b). Some cancer cells express PD-L1 and PD-L2 to evade tumor surveillance by immune cells. Presently, most of the cultured cancer cells expressed PD-L1 (median, 88.3%; range, 0.4–100%), but expression was significantly lower in the TNBC group than in the non-TNBC group (Supplementary Fig. S1c). PD-L1 expression was not correlated with chemotherapy (Supplementary Fig. S1f). Analysis of the association of PD-L1 expression levels with reactivity revealed significantly lower expression levels of PD-L1 in total and NAC samples in the reactive group (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

Characteristics of primary breast cancer cells. Percentage of cells expressing EpCAM, CK, or both (a), MHC class I (b), and PD-L1 (c) in cancer cells and comparison between non-reactive (white bar) and reactive (grey bar) groups within the samples as a whole (left) and within the TNBC (center) and NAC samples (right). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

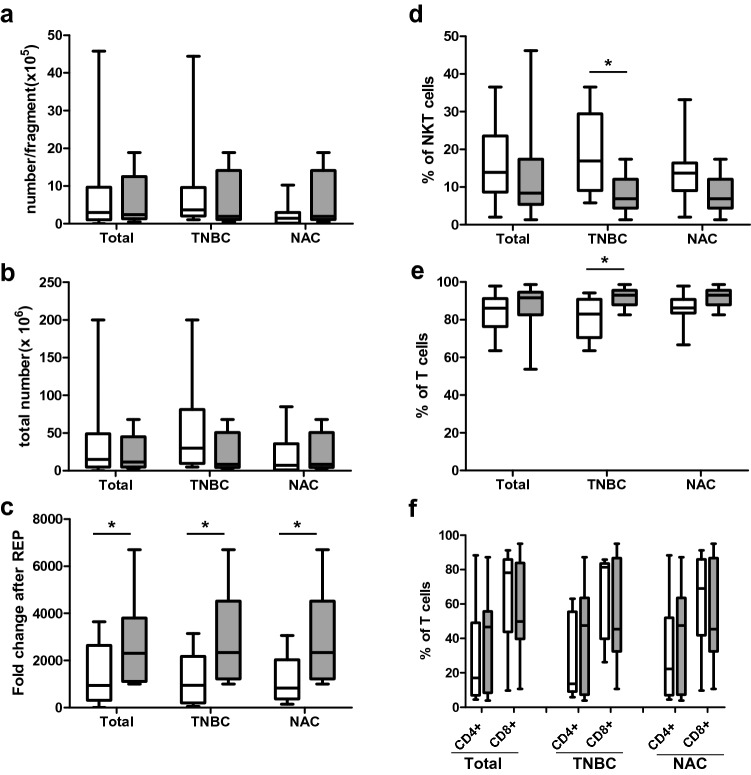

Immune cell factors associated with in vitro reactivity

The number of cultured TILs was not significantly associated with the reactivity, but fold-change after REP was significantly higher in the reactive groups in total, TNBC, and NAC samples (Fig. 4a–c). A higher ratio of T cells and lower portion of NKT-like cells were associated with reactivity in TNBC samples, but not in total and NAC samples (Fig. 4d, e). The ratio of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells did not correlate with in vitro reactivity (Fig. 4f).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of expansion ability and immune cell composition of TILs according to reactivity. Comparison of the numbers per fragment (a) and total number (b) of 2 weeks cultured TILs, fold-change after REP (c), and the ratio of NKT-like cells (d) and T cells (e, f) of REP TILs between non-reactive (white bar) and reactive (grey bar) groups within the samples as a whole (left) and within the TNBC (center) and NAC samples (right). *p < 0.05

Since the reactive group showed high expansion propensity, TCR sequences were analyzed to investigate whether a higher fold-change of TILs after REP in the reactive group reflected the clonal expansion of specific T cells. We compared the TCR clonality (number of clonotypes) and richness (number of reads) between the reactive and non-reactive groups. TCR clonality and richness of REP TILs were not significantly associated with the reactivity (Supplementary Fig. S2).

High tumor levels of TILs are correlated with better clinical outcomes in the majority of patients, but not for all cases [19–24], implying the additional importance of the tumor microenvironment and the state of TILs. Characterization of TILs with antitumor reactivity to autologous tumor cells is needed. As the activation state of T cells is important to induce anticancer immunity, we examined the expression of markers that are increased during T cell activation, including CD107a (LAMP-1), CD134 (OX40), and CD137 (4-1BB). None of the activation markers showed significantly different expression between the reactive and non-reactive groups (Fig. 5a–c). Analyses of the expression of immune checkpoint molecules KLRG1, LAG3, TIGIT, TIM3, CD39, and PD-1 revealed higher expression of PD-1 on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the reactive groups than in the non-reactive groups in TNBC samples (p = 0.008 for CD4+ and p = 0.05 for CD8+ T cells; Fig. 5e). Higher expression of PD-1 in the reactive groups likely reflects the upregulation of immune checkpoint molecules on the surface of activated T cells upon interaction with their ligands. PD-1 expression levels were higher in NAC samples than in non-NAC samples (Supplementary Fig. S3f), and all reactive TNBC samples were derived from tumors with NAC. Thus, higher expression of PD-1 in the reactive group may reflect the release of tumor antigens during chemotherapy, and the greater interaction of T cells with their antigens in patients with NAC, resulting in PD-1 expression upregulation.

Fig. 5.

Activation and exhaustion markers on T cells within expanded TILs. Comparison of the expression levels of activation markers (41BB, CD107a, and OX40) and exhaustion markers (KLRG1, LAG3, TIGIT, Tim3, CD39, and PD-1) of T cells between reactive (white bar) and non-reactive (black bar) groups within the samples as a whole (a, d) and within the TNBC (b, e) and NAC samples (c, f). **p < 0.01

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) are the major population that inhibits immune responses in tumor sites. Increased numbers of Tregs are observed in the blood, tumor site, and tumor-draining lymph node in cancer patients, which is associated with poor clinical outcome [25]. To determine whether the proportion of Tregs in expanded TILs is correlated with reactivity, we analyzed FOXP3+ T cells and CD25+FOXP3+ Tregs. Approximately 20% of T cells of expanded TILs expressed FOXP3 (median; 22.6%; range, 10.8–41.2% in CD4+ T cells; median; 22.4%; range, 10.0–47.4% in CD8+ T). However, CD25 and FOXP3 double positive cells, which are considered conventional Tregs, were present only in low proportions (median; 1.4%; range, 0.3–11.8% in CD4+ T cells; median; 0.2%; range, 0–9.1% in CD8+ T cells) and most expanded TILs did not express CD25 (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Discussion

Although many preclinical and clinical trials have demonstrated the anticancer effects of ACT, it is effective in only a few cancer types with high mutational burden. ACT is not beneficial in many patients. To increase the efficiency of immunotherapy, the characteristics of cancer cells and immune cells in the tumor microenvironment of responders must be clarified.

We analyzed the in vitro reactivity of cultured TILs against autologous breast cancer cells. Seven of 31 cases showed reactivity defined by increased IFN-γ production. IFN-γ-producing TILs were able to kill the cancer cells directly after being co-cultured with autologous cancer cells (Supplementary Fig. S5a). Because of an insufficiency in cultured autologous cancer cells, we could not perform a second experiment to confirm the results. However, tests using different target and effector cell ratios of 1:1 and 1:4 showed consistent results. In addition, as we have previously reported [14], tumor growth was inhibited after injection of TILs showing IFN-γ response in two PDX models, whereas tumor growth was not decreased in the group of mice injected with TILs not displaying the IFN-γ response (Supplementary Fig. S5b). The findings indicate the possibility that TILs displaying an IFN-γ response are also able to kill cancer cells directly. However, this needs to be conclusively demonstrated in more samples. To identify the factors involved in cancer reactivity of TILs, we analyzed the differential expression of surface proteins on cancer cells and cultured TILs between reactive and non-reactive groups. PD-L1 expression on cancer cells was lower in the reactive group, consistent with previous reports that cancer cells express PD-L1 to evade immunosurveillance, which is closely associated with poor prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, and colorectal cancer [26–29].

Since six of seven reactive TILs were from TNBC cases, we analyzed the cancer cells and TILs between the reactive and non-reactive groups of TNBC samples. The TNBC reactive group displayed significantly more T cells and fewer NKT-like cells than did the non-reactive group. NKT cells possess the features of T cells and NK cells and can thus modulate innate and adaptive immunity [30]. Type I and type II NKT cells are differentiated by TCR characteristics and show different immune responses in tumors. A low NKT-like cell ratio was associated with antitumor reactivity in this study. Thus, it is possible that the NKT-like cells in cultured TILs featured suppressive activity. It will be necessary to study the detailed characteristics of NKT-like cells using markers such as CD1d and to analyze the cytokine profiles. Additionally, direct reactivity of NKT-like cells to autologous tumor cells should be demonstrated.

PD-1 expression on T cells of REP TILs was higher in the reactive group than in the non-reactive group in TNBC samples. PD-1 is a marker of exhausted T cells, and high expression of PD-1 is associated with poor prognosis in certain types of cancer [26, 31]. However, infiltration of PD-1-expressing CD8+ T cells in tumors is associated with good prognosis in human papilloma virus-associated head and neck cancer, follicular lymphoma, colorectal cancer, and TNBC [32–35], supporting the hypothesis that PD-1-expressing T cells are cancer-specific. PD-1-expressing CD8+ T cells in TILs and PBMCs display neoantigen specificity and kill autologous tumor cells in melanoma [36]. Since a higher ratio of PD-1-expressing T cells in REP TILs was presently correlated with reactivity, the anti-cancer response of antigen-specific PD-1-expressing T cells can likely be increased using PD-1 inhibitors.

FOXP3 was expressed on approximately 20% of expanded T cells. The supplemented IL-2 and anti-CD3 antibody in the medium would have induced FOXP3+ T cells during expansion of TILs [37]. Most of the FOXP3+ T cells did not express CD25, while only a small proportion of FOXP3+ T cells co-expressed CD25. CD4+FOXP3+CD25−/low T cells are reportedly increased in cancers [38]. CD4+CD25low FOXP3+ cells showed increased expression of PD-1 and Ki-67, and reduced expression of FOXP3 and CTLA-4, compared to CD4+CD25high FOXP3+ conventional Tregs. They were less suppressive, suggesting that they represent the late stage Tregs derived from CD4+CD25high FOXP3+ cells [39] or precursors of Tregs cells [40] that could be converted to Tregs. Additionally, some of the cells produced more IL-2 and IFN-γ than conventional Tregs and more IL-10 than CD4+CD25− effector cells showing intermediate phenotypes of regulatory cells and effector cells, implying that they are a heterogenous population [38]. Helios could be a marker to distinguish the heterogenous population [41]. Because there are no differences in FOXP3+ T cell and FOXP3+CD25+ T cell percentage between reactive and non-reactive groups, further characterization of FOXP3+ cells with markers such as Helios is needed.

Although CD25−FOXP3+ cells are less suppressive than CD25+FOXP3+ T cells, they are less effective than effector cells and have the potential to convert to Tregs. Thus, it is important to reduce this population to enhance the efficacy of TIL therapy. Some chemotherapeutic agents, neutralizing antibodies targeting receptors expressed on Tregs, and epigenetic modifiers can reduce Treg levels or convert suppressive Tregs to immune activating cells, leading to anti-cancer immunity augmentation [42]. Thus, TIL cultured with such agents or antibodies targeting Tregs could be promising strategies to reduce the FOXP3+ population in expanded TILs.

In vitro reactivity was evident in TNBC samples, and all reactive samples were derived from surgical specimens after NAC. Whether this is due to factors involved in breast cancer subtypes or caused by chemotherapy must be considered. TNBC is a tumor with a higher mutation burden than other subtypes of breast cancer [43]. Therefore, TNBC has a relatively high level of neoantigens, and TILs in TNBC might have a greater chance to contact neoantigens, leading to expansion of cancer-specific TILs in the tumor microenvironment. MHC class I expression levels are also different in the breast cancer subtypes. We found that MHC class I expression was negatively correlated with ER expression levels and positively correlated with TIL levels [44]. Thus, the high expression of MHC class I in TNBC might increase immune cell infiltration to the tumor site. Additionally, the release of tumor antigens during NAC might recruit antigen-specific T cells to the tumor site, and they were expanded upon interaction with the tumor antigens.

The collective results implicate TILs as a promising therapy for breast cancer patients, especially for TNBC patients with residual tumors after NAC. Additionally, the combination of TILs with immune checkpoint blockade and chemotherapy, culturing TILs with neoantigens to enrich antigen-specific T cells, or using antigen-specific T cell markers for sorting might increase treatment efficacy. These approaches should be evaluated in the treatment of breast cancer.

Conclusions

We analyzed the in vitro reactivity between cancer cells and TILs and characterized the patient-, cancer-, and immune cell-related factors associated with reactivity. Seven of 31 cases (including 35% of TNBC cases) showed reactivity against autologous cancer cells. For TNBC samples, the reactive group displayed lower PD-L1 expression on cancer cells and a higher ratio of PD-1-expressing T cells. All reactive TNBCs were NAC-resistant tumors, which have a higher risk of tumor recurrence and high mortality rates. Five of six patients with tumor-reactivity had tumor recurrence within 23 months of follow-up. These results implicate adoptive TIL therapy combined with PD-1 inhibitors as a promising therapeutic modality for TNBC patients, especially when NAC therapy fails.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Abbreviations

- ACT

Adoptive cell transfer

- CK

Cytokeratin

- EpCAM

Epithelial cell adhesion molecule

- ER

Estrogen receptor

- HER2+

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive

- HR

Hormone receptor

- IFN-γ

Interferon-gamma

- MDSCs

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells

- MHC

Major histocompatibility complex

- NAC

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy

- NK

Natural killer

- NKT

Natural killer T

- PBMC

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- PDX

Patient-derived xenograft

- PR

Progesterone receptor

- REP

Rapid expansion

- TCR

T cell receptor

- TIL

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte

- TLS

Tertiary lymphoid structure

- TNBC

Triple-negative breast cancer

- Treg

Regulatory T cell

Author contributions

HjL interpreted the data associated with tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte reactivity in breast cancer and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. YAK and HSP participated in sample preparation and analysis. YK and JHS analyzed the TCR repertoire of the TILs. HL, GG, and HJL contributed as pathologists and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Korean Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare (HI15C0708 and HI17C0337) and the Asan Institute for Life Sciences, Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea (2018IL0169, 2019IL0169, and 2019IL0839).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consents to participate

Tumor tissues were obtained from patients along with their consent to the use of the specimen for research purposes. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center (IRB#2015-0438).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Gyungyub Gong, Email: gygong@amc.seoul.kr.

Hee Jin Lee, Email: backlila@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Waks AG, Winer EP. Breast cancer treatment: a review. JAMA. 2019;321(3):288–300. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.19323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernhard H, Neudorfer J, Gebhard K, Conrad H, Hermann C, Nahrig J, Fend F, Weber W, Busch DH, Peschel C. Adoptive transfer of autologous, HER2-specific, cytotoxic T lymphocytes for the treatment of HER2-overexpressing breast cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;57(2):271–280. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0355-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sparano JA, Fisher RI, Weiss GR, Margolin K, Aronson FR, Hawkins MJ, Atkins MB, Dutcher JP, Gaynor ER, Boldt DH, et al. Phase II trials of high-dose interleukin-2 and lymphokine-activated killer cells in advanced breast carcinoma and carcinoma of the lung, ovary, and pancreas and other tumors. J Immunother Emphas Tumor Immunol. 1994;16(3):216–223. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199410000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tchou J, Zhao Y, Levine BL, Zhang PJ, Davis MM, Melenhorst JJ, Kulikovskaya I, Brennan AL, Liu X, Lacey SF, et al. Safety and efficacy of intratumoral injections of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells in metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Immunol Res. 2017;5(12):1152–1161. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinez M, Moon EK. CAR T cells for solid tumors: new strategies for finding, infiltrating, and surviving in the tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol. 2019;10:128. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zacharakis N, Chinnasamy H, Black M, Xu H, Lu YC, Zheng Z, Pasetto A, Langhan M, Shelton T, Prickett T, et al. Immune recognition of somatic mutations leading to complete durable regression in metastatic breast cancer. Nat Med. 2018;24(6):724–730. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0040-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egelston CA, Avalos C, Tu TY, Simons DL, Jimenez G, Jung JY, Melstrom L, Margolin K, Yim JH, Kruper L, et al. Human breast tumor-infiltrating CD8(+) T cells retain polyfunctionality despite PD-1 expression. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):4297. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06653-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stanton SE, Adams S, Disis ML. Variation in the incidence and magnitude of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in breast cancer subtypes: a systematic review. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(10):1354–1360. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Kammula US, Hughes MS, Phan GQ, Citrin DE, Restifo NP, Robbins PF, Wunderlich JR, et al. Durable complete responses in heavily pretreated patients with metastatic melanoma using T-cell transfer immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(13):4550–4557. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Creelan B, Teer J, Toloza E, Mullinax J, Landin A, Gray J, Tanvetyanon T, Taddeo M, Noyes D, Kelley L, et al. OA05.03 safety and clinical activity of adoptive cell transfer using tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) combined with nivolumab in NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(10):S330–S331. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jazaeri AA, Zsiros E, Amaria RN, Artz AS, Edwards RP, Wenham RM, Slomovitz BM, Walther A, Thomas SS, Chesney JA, et al. Safety and efficacy of adoptive cell transfer using autologous tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (LN-145) for treatment of recurrent, metastatic, or persistent cervical carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(15_suppl):2538–2538. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujita K, Ikarashi H, Takakuwa K, Kodama S, Tokunaga A, Takahashi T, Tanaka K. Prolonged disease-free period in patients with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer after adoptive transfer of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Clin Cancer Res. 1995;1(5):501–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tran E, Robbins PF, Lu YC, Prickett TD, Gartner JJ, Jia L, Pasetto A, Zheng Z, Ray S, Groh EM, et al. T-cell transfer therapy targeting mutant KRAS in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(23):2255–2262. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1609279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee HJ, Kim YA, Sim CK, Heo SH, Song IH, Park HS, Park SY, Bang WS, Park IA, Lee M, et al. Expansion of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and their potential for application as adoptive cell transfer therapy in human breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8(69):113345–113359. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.June CH, O'Connor RS, Kawalekar OU, Ghassemi S, Milone MC. CAR T cell immunotherapy for human cancer. Science. 2018;359(6382):1361–1365. doi: 10.1126/science.aar6711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salgado R, Denkert C, Demaria S, Sirtaine N, Klauschen F, Pruneri G, Wienert S, Van den Eynden G, Baehner FL, Penault-Llorca F, et al. The evaluation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in breast cancer: recommendations by an International TILs Working Group 2014. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(2):259–271. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee HJ, Park IA, Song IH, Shin SJ, Kim JY, Yu JH, Gong G. Tertiary lymphoid structures: prognostic significance and relationship with tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2016;69(5):422–430. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2015-203089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Acker HH, Capsomidis A, Smits EL, Van Tendeloo VF. CD56 in the immune system: More than a marker for cytotoxicity? Front Immunol. 2017;8:892. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohtani H. Focus on TILs: prognostic significance of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in human colorectal cancer. Cancer Immun. 2007;7(1):4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liakou CI, Narayanan S, Ng Tang D, Logothetis CJ, Sharma P. Focus on TILs: prognostic significance of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in human bladder cancer. Cancer Immun. 2007;7(1):10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dunn GP, Dunn IF, Curry WT. Focus on TILs: prognostic significance of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in human glioma. Cancer Immun. 2007;7(1):12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uppaluri R, Dunn GP, Lewis JS. Focus on TILs: prognostic significance of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in head and neck cancers. Cancer Immun. 2008;8(1):16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oble DA, Loewe R, Yu P, Mihm MC. Focus on TILs: prognostic significance of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in human melanoma. Cancer Immun. 2009;9(1):3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Denkert C, von Minckwitz G, Darb-Esfahani S, Lederer B, Heppner BI, Weber KE, Budczies J, Huober J, Klauschen F, Furlanetto J, et al. Tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes and prognosis in different subtypes of breast cancer: a pooled analysis of 3771 patients treated with neoadjuvant therapy. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(1):40–50. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30904-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shang B, Liu Y, Jiang S-J, Liu Y. Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2015;5:15179. doi: 10.1038/srep15179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shen T, Zhou L, Shen H, Shi C, Jia S, Ding GP, Cao L. Prognostic value of programmed cell death protein 1 expression on CD8+ T lymphocytes in pancreatic cancer. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):7848. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08479-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou C, Tang J, Sun H, Zheng X, Li Z, Sun T, Li J, Wang S, Zhou X, Sun H, et al. PD-L1 expression as poor prognostic factor in patients with non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8(35):58457–58468. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jung HI, Jeong D, Ji S, Ahn TS, Bae SH, Chin S, Chung JC, Kim HC, Lee MS, Baek MJ. Overexpression of PD-L1 and PD-L2 is associated with poor prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res Treat. 2017;49(1):246–254. doi: 10.4143/crt.2016.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koganemaru S, Inoshita N, Miura Y, Miyama Y, Fukui Y, Ozaki Y, Tomizawa K, Hanaoka Y, Toda S, Suyama K, et al. Prognostic value of programmed death-ligand 1 expression in patients with stage III colorectal cancer. Cancer Sci. 2017;108(5):853–858. doi: 10.1111/cas.13229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nair S, Dhodapkar MV. Natural killer T cells in cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1178. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shi B, Li Q, Ma X, Gao Q, Li L, Chu J. High expression of programmed cell death protein 1 on peripheral blood T-cell subsets is associated with poor prognosis in metastatic gastric cancer. Oncol Lett. 2018;16(4):4448–4454. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.9190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Badoual C, Hans S, Merillon N, Van Ryswick C, Ravel P, Benhamouda N, Levionnois E, Nizard M, Si-Mohamed A, Besnier N, et al. PD-1-expressing tumor-infiltrating T cells are a favorable prognostic biomarker in HPV-associated head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73(1):128–138. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carreras J, Lopez-Guillermo A, Roncador G, Villamor N, Colomo L, Martinez A, Hamoudi R, Howat WJ, Montserrat E, Campo E. High numbers of tumor-infiltrating programmed cell death 1-positive regulatory lymphocytes are associated with improved overall survival in follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(9):1470–1476. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Y, Liang L, Dai W, Cai G, Xu Y, Li X, Li Q, Cai S. Prognostic impact of programed cell death-1 (PD-1) and PD-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression in cancer cells and tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in colorectal cancer. Mol Cancer. 2016;15(1):55. doi: 10.1186/s12943-016-0539-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brockhoff G, Seitz S, Weber F, Zeman F, Klinkhammer-Schalke M, Ortmann O, Wege AK. The presence of PD-1 positive tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in triple negative breast cancers is associated with a favorable outcome of disease. Oncotarget. 2018;9(5):6201–6212. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simon S, Labarriere N. PD-1 expression on tumor-specific T cells: Friend or foe for immunotherapy? Oncoimmunology. 2017;7(1):e1364828. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1364828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Josefowicz SZ, Lu LF, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cells: mechanisms of differentiation and function. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:531–564. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Niakan A, Faghih Z, Talei AR, Ghaderi A. Cytokine profile of CD4(+)CD25(-)FoxP3(+) T cells in tumor-draining lymph nodes from patients with breast cancer. Mol Immunol. 2019;116:90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2019.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferreira RC, Simons HZ, Thompson WS, Rainbow DB, Yang X, Cutler AJ, Oliveira J, Castro Dopico X, Smyth DJ, Savinykh N, et al. Cells with Treg-specific FOXP3 demethylation but low CD25 are prevalent in autoimmunity. J Autoimmun. 2017;84:75–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2017.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schuster M, Plaza-Sirvent C, Visekruna A, Huehn J, Schmitz I. Generation of Foxp3(+)CD25(-) regulatory T-cell precursors requires c-Rel and IkappaBNS. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1583. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thornton AM, Lu J, Korty PE, Kim YC, Martens C, Sun PD, Shevach EM. Helios(+) and Helios(-) treg subpopulations are phenotypically and functionally distinct and express dissimilar TCR repertoires. Eur J Immunol. 2019;49(3):398–412. doi: 10.1002/eji.201847935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Han S, Toker A, Liu ZQ, Ohashi PS. Turning the tide against regulatory T cells. Front Oncol. 2019;9:279. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barroso-Sousa R, Jain E, Cohen O, Kim D, Buendia-Buendia J, Winer E, Lin N, Tolaney SM, Wagle N. Prevalence and mutational determinants of high tumor mutation burden in breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(3):387–394. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2019.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee HJ, Song IH, Park IA, Heo SH, Kim YA, Ahn JH, Gong G. Differential expression of major histocompatibility complex class I in subtypes of breast cancer is associated with estrogen receptor and interferon signaling. Oncotarget. 2016;7(21):30119–30132. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.