Abstract

Adoptive cell therapy (ACT) of tumor infiltration lymphocytes (TIL) yields promising clinical results in metastatic melanoma patients, who failed standard treatments. Due to the fact that metastatic lung cancer has proven to be susceptible to immunotherapy and possesses a high mutation burden, which makes it responsive to T cell attack, we explored the feasibility of TIL ACT in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients. Multiple TIL cultures were isolated from tumor specimens of five NSCLC patients undergoing thoracic surgery. We were able to successfully establish TIL cultures by various methods from all patients within an average of 14 days. Fifteen lung TIL cultures were further expanded to treatment levels under good manufacturing practice conditions and functionally and phenotypically characterized. Lung TIL expanded equally well as 103 melanoma TIL obtained from melanoma patients previously treated at our center, and had a similar phenotype regarding PD1, CD28, and 4-1BB expressions, but contained a higher percent of CD4 T cells. Lung carcinoma cell lines were established from three patients of which two possessed TIL cultures with specific in vitro anti-tumor reactivity. Here, we report the successful pre-clinical production of TIL for immunotherapy in the lung cancer setting, which may provide a new treatment modality for patients with metastatic NSCLC. The initiation of a clinical trial is planned for the near future.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00262-018-2174-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Non-small cell lung cancer, Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes, Adoptive cell therapy, Immunotherapy

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death worldwide. Age and smoking are the primary risk factors of lung cancer. For NSCLC, treatment based on surgical removal in the early stages of the disease results in better survival. Yet the overall 5-year survival rate is only 15% [1]. Patients with advanced disease that are less prone to benefit from surgical intervention or systemic treatments such as platinum-based chemotherapy and novel biological treatments [2] continue to challenge physicians in daily clinical practice.

Lately, a number of monoclonal antibodies specific to the PD-1 (nivolumab and pembrolizumab) or its ligand PD-L1 (atezolizumab) were approved for immunotherapy-based treatments for lung cancer [3, 4]. Nivolumab, a human IgG4 PD-1 receptor blocking antibody with no ADCC activity, was FDA approved in 2015 for second-line chemotherapy treatment of resistant squamous NSCLC. A single-arm, phase II trial evaluating the activity and safety of nivolumab in advanced, refractory NSCLC demonstrated a 14.5% objective response rate (17 of 117 patients), as measured by radiographic response, as well as a 26% rate of stable disease in 20 patients [5].

There is more evidence that anti-PD-1/PD-L1 blocking antibodies have substantial clinical activity in lung cancer patients and that NSCLC is responsive to immunotherapy, especially if the tumor is infiltrated by CD8+ T lymphocytes [6].

Furthermore, high levels of intra-tumoral TIL were associated with improved recurrence-free survival in stage 1a NSCLC patients, as well as a reduced likelihood of systemic recurrence [7]. It was also shown that a higher frequency of TIL within large node-negative NSCLC correlates with decreased risk of disease recurrence and improved disease-free survival [8].

Following melanoma, lung cancer possesses the highest mutation burden and thus expresses mutated neo-antigentic peptides, which can trigger T cell responses and can be targeted effectively by T cells [9–11].

The facts that lung cancer is susceptible to immunotherapy such as anti-PD-1/PDL-1 antibodies, the overall survival positively correlates with TIL infiltration and its high mutation burden, makes it an ideal candidate for adoptive therapy with tumor infiltrating T lymphocytes.

Immunotherapy based on adoptive cell therapy (ACT) of TIL has proven to be highly effective in metastatic melanoma patients. TIL immunotherapy involves several laboratory and clinical steps, which start with surgical resection of tumor tissue from the patients and continues with tumor processing to establish T cell cultures, which are then expanded in IL-2 containing medium for 2–4 weeks. In the following step, TIL are expanded for 2 weeks to large amounts using a rapid expansion procedure (REP) with anti-CD3 antibody, IL-2, and irradiated feeder cells. During the REP, TILs undergo massive numerical expansion that can yield 0.5 × 1010 cells for infusion. TIL are then administered to the patient, who undergoes lympho-depleting preconditioning, which was shown to improve the persistence of the infused cells, followed by high-dose IL-2 administration to support the survival of TIL in the patient [12, 13].

Others and we could show that TIL therapy yields response rates of around 40% in highly advanced metastatic melanoma patients, who failed IL-2 based therapy or therapy with the anti-CTLA-4 antibody ipilimumab, and significantly improves the overall survival in responding patients [14–19]. Moreover, 10–20% of the metastatic patients experience durable complete regression of all lesions and are disease-free many years after treatment, suggesting even the possibility of cure.

In a report from 1995, Ratto et al. assessed the efficacy of TIL therapy in combination with subcutaneous IL-2 administration in the postoperative treatment of stages II, IIIa, and IIIb NSCLC [20]. TIL were then grown in IL-2 containing media, but not rapidly expanded with anti-CD3 antibody and irradiated feeder cells, as it is the standard today. Nevertheless, the 3-year survival was significantly better for patients who underwent TIL ACT than for non-treated patients, which further supports the idea of using TIL ACT as a treatment modality for NSCLC.

Here, we report the pre-clinical production and evaluation of TIL for adoptive cell therapy in lung cancer patients, based on our vast clinical experience with melanoma-derived TIL. The establishment of TIL cultures and autologous cancer cell lines, as well as the execution of complete large scale TIL expansions to treatment levels was tested. Cell production was performed with clinically compatible reagents under good manufacturing practice (GMP) conditions. Immune phenotyping and functional characterization of the established TILs were performed to support the implementation of TIL ACT for lung cancer patients. Results of the pre-clinical evaluation of this technology in the lung cancer setting are report here.

Materials and methods

Patients

Patients with non-small cell lung cancer indented for surgery, which did not have neo adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy prior to the surgery, were included. Surgically resected tumor tissue was transported within a few hours to the GMP facility to generate TIL cultures.

Generation of TIL cultures

Tumor tissue was subjected to various processing methods including fragmentation (Frag.), tissue remnant culture (TRC), and enzymatic digestion (Digest) as previously described for melanoma specimens [13]. The tumor was sliced with a scalpel into small pieces, about 1–3 mm3 of size. Enzymatic digestion of the pieces, with collagenase (Sigma-Aldrich, Israel) and dornase alfa (Pulmozyme, Genentech, South San Francisco, CA) containing medium, was usually performed within 2–4 h after surgery for 2 h at 37 °C to obtain a single-cell suspension. Small tumor fragments (1–2 mm3 in size) or 1 × 10 E6 live nucleated cells, obtained by Digest or TRC, were plated per well in 24-well plates in 2 ml complete medium (CM) comprised RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) containing 10% heat-inactivated human serum (Valley Biomedical, Winchester, VA or Gemini Bio, West Sacramento, CA) supplemented with 3000 IU/ml recombinant human IL-2 (Proleukin, Novartis Pharma, Germany), 25 mmol/l HEPES pH 7.2 (Gibco), 50 µg/ml gentamycin (Gentamicin IKA, Teva, Israel), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin (Gibco). TIL cultures were split whenever required to maintain a cell density between 0.5 and 2 × 10E6 per ml. A TIL culture was considered established after clearance of adherent tumor cells and reaching a total cell number of at least 45 × 10E6 cells per patient (typically on days 18–21). Next, a large-scale rapid expansion procedure (REP) was initiated by stimulating TIL with 30 ng/ml anti-CD3 antibody MACS GMP CD3 pure (clone OKT-3; Miltenyi Biotech, Germany), 3000 IU/ml IL-2, and irradiated peripheral blood mononuclear cells from non-related donors as feeder cells (5000 rad, 100:1 ratio between feeder cells and TIL) in 50% CM, 50% AIM-V medium (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) in GRex flasks (Wilson Wolf, St Paul, MN) as described earlier [15, 21]. After 14 days, cultures expanded by about 1000-fold. The cells were harvested and functionally evaluated.

Generation of primary lung cancer cell cultures

Autologous lung cancer cell lines were cultured in tissue culture flasks using Keratinocyte-SFM Medium Kit (Gibco) supplemented with l-glutamine, pituitary bovine pituitary extract, and human epithelial growth factor as part of the kit.

Microbiological tests

The culturing process was monitored by validated microbiological tests, to guarantee the sterility of the process and allow the smooth adaptation to a clinical protocol.

Microbiological tests were performed during the rapid expansion procedure by membrane filtration technology and on the potential infusion product by direct inoculation and gram stain. Nested PCR for the detection of the mycoplasma genome and a chromogenic endotoxin assay, which utilizes a modified limulus amoebocyte lysate and a synthetic color-producing substrate, were also conducted.

IFNγ release assay

The anti-tumor reactivity of TIL was determined by IFNγ release assay. TIL were co-cultured with autologous lung cancer cells at an E:T ratio of 1:1 (1 × 10E5 each) in a 96-well plate for overnight. Cells were centrifuged, supernatant was collected, and the secreted IFNγ levels were determined by ELISA according to the manufacturer’s instructions (BioLegend, San Diego, CA). Measurements were performed in triplicates.

To determine functionality, 1 × 10E5 TIL were stimulated with 10 ng/ml MACS GMP CD3 pure antibody overnight and IFNγ levels were determined by ELISA as described before. To determine intracellular IFNγ levels, 2 × 10E5 TIL were stimulated with 10 µl/ml MACS GMP CD3 pure antibody for 2 h and Brefeldin A (part of kit eBioscience Intracellular Fixation & Permeabilization Buffer plus Brefeldin A; Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Watham, MA) was added for an additional 2 h according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Flow cytometry was performed by the addition of CD8 antibody (PE-Cy7 conjugated; Biolegend) followed by fixation and permeabilization (part of kit eBioscience Intracellular Fixation & Permeabilization Buffer plus Brefeldin A; Invitrogen) and addition of IFNγ antibody (APC conjugated; clone 4S.B3; Invitrogen). Samples were analyzed using FlowJo software. Measurements were performed in triplicates.

Cell-mediated cytotoxicity assay

TIL were co-cultured with autologous carcinoma cells overnight at 37 °C, at an E:T ratio of 1:5 (10 × 10E4 TIL and 2 × 10E4 carcinoma) and 1:10 (20 × 10E4 TIL and 2 × 10E4 carcinoma) in 200 µl CM. Cells were centrifuged, supernatant was collected, and the level of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), a stable cytosolic enzyme that is released upon cell lysis, was determined by LDH-Cytotoxicity Colorimetric Assay Kit II according to the manufacturer’s instructions (BioVision, Milpitas, CA). Measurements were performed in triplicates.

Flow cytometry

Different membrane molecules were analyzed using conjugated mouse anti-human antibodies against CD3 (PE conjugated; BD Bioscience, Switzerland), CD56 (APC conjugated; BD Bioscience), CD4 (FITC conjugated; BD Bioscience), CD8 (Per-CP conjugated; BD Bioscience), CD28 [APC conjugated (eBioscience, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Watham, MA), PD-1 (FITC conjugated; clone: EH12.2H7; BioLegend)], and 4-1BB (PE conjugated; clone: 4B4-1; BioLegend). TIL were washed and re-suspended in cell staining buffer (BioLegend). Cells were incubated for 30 min with the antibodies on ice, washed in buffer, and measured using FACS Calibur flow cytometer (BD Bioscience). Samples were analyzed using FlowJo software.

Statistics

Significance of variation between groups was evaluated using a non-parametric two-tailed Student’s t test. Test for differences between proportions was performed using two-sided Fisher’s exact test with p ≤ 0.05 considered significant.

Results

Five patients with non-small cell lung cancer intended for curative surgery, who did not have neo adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy prior to the surgery, underwent exploratory thoracotomy. Patients’ characteristics are presented in Table 1. Four patients were males, mean age was 67.8 ± 3 years, four tumors were adenocarcinoma type (two with acinar adenocarcinoma and one with mucin acinar adenocarcinoma), and one was squamous cell type.

Table 1.

Lung TIL establishment

| Pt. | Fragmentsa | Digest | TRC | Totalb | Successful (≥ 45 × 106) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 × 106 | 56 × 106 | 20 × 106 | 86 × 106 | Yes |

| 2 | 100 × 106 | 172 × 106 | 209 × 106 | 481 × 106 | Yes |

| 3 | 52 × 106 | 150 × 106 | 12 × 106 | 214 × 106 | Yes |

| 4 | 113 × 106 | 64 × 106 | 69 × 106 | 246 × 106 | Yes |

| 5 | 51 × 106 | 60 × 106 | 55 × 106 | 166 × 106 | Yes |

| Av. | 65 × 106 | 100 × 106 | 73 × 106 | 239 × 106 | 5 of 5 |

| ± SD | 42 × 106 | 56 × 106 | 80 × 106 | 148 × 106 |

aSum of TIL generated from 6 to 8 fragments

bTotal cell count after 18–21 days

All patients underwent anatomical resection and a fraction of the original primary tumor was delivered to the laboratory after initial pathological examination. A mean volume of 1.5 ± 1.19 cm3 (range 0.63–3.48 cm3) tumor tissue was available for further processing (Suppl. Table 1).

Lung TIL establishment

TIL cultures derived from NSCLC specimens (lung TIL) were initiated from all five specimens by enzymatic digestion, TRC, and fragmentation methods (6–8 individual fragments per patients). The average number of TIL established within 18–21 days by enzymatic digestion, and TCR was 100 × 106 ± 55 × 106 TIL and 73 × 106 ± 79 × 106 TIL, respectively, and the sum of TIL generated from 6 to 8 individual fragments was 65 × 106 ± 42 × 106 (Table 2). There was no significant difference between the isolation methods regarding TIL yield (p values ≥ 0.25).

Table 2.

Characterization of lung TIL pre- and post-REP

| Pt. | Isolat meth. | REP day 0 (pre-REP) | REP day 14 (post-REP) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD8+ CD3+ (%) |

CD4+ CD3+ (%) |

CD56+ CD3− (%) |

Fold exp. | Cell no. × 109 | Funct.b | CD8+ CD3+ (%) |

CD4+ CD3+ (%) |

CD28+ CD8+ (%) |

CD28+ CD4+ (%) |

41BB+ CD8+ (%) |

41BB+ CD4+ (%) |

PD1+ CD8+ (%) |

PD1+ CD4+ (%) |

||

| 1 | Digest | 24 | 69 | 6 | 1746 | 79 | 11,209 | 42 | 58 | 8 | 48 | 2 | 6 | 22 | 28 |

| Frag. 5 | 5 | 86 | 9 | 1235 | 56 | 12,980 | 2 | 98 | 0 | 81 | 0 | 10 | 2 | 85 | |

| TRCa | 9 | 80 | 12 | 558 | 25 | 561 | 14 | 86 | 3 | 36 | 1 | 17 | 5 | 36 | |

| 2 | Digest | 37 | 40 | 23 | 1596 | 72 | 22,208 | 83 | 17 | 16 | 12 | 3 | 2 | 44 | 11 |

| Frag. 5 | 51 | 43 | 6 | 1546 | 70 | 4282 | 79 | 21 | 9 | 11 | 3 | 2 | 28 | 18 | |

| TRC | 35 | 58 | 8 | 1495 | 67 | 1568 | 35 | 65 | 4 | 36 | 1 | 6 | 22 | 56 | |

| 3 | Digest | 36 | 61 | 3 | 1107 | 50 | 15,836 | 20 | 80 | 2 | 49 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 34 |

| Frag. 3a | 86 | 12 | 2 | 969 | 44 | 1642 | 96 | 4 | 10 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 12 | 2 | |

| TRC | 50 | 49 | 2 | 631 | 28 | 1211 | 58 | 42 | 9 | 19 | 2 | 3 | 30 | 19 | |

| 4 | Digesta | 31 | 57 | 12 | 983 | 44 | 30,445 | 62 | 38 | 10 | 28 | 2 | 3 | 41 | 23 |

| Frag. 4 | 14 | 78 | 7 | 1204 | 54 | 2603 | 40 | 60 | 7 | 45 | 1 | 4 | 28 | 49 | |

| TRC | 30 | 61 | 9 | 925 | 42 | 12,603 | 57 | 43 | 10 | 34 | 2 | 3 | 33 | 26 | |

| 5 | Digest | 37 | 63 | 27 | 892 | 40 | 26,844 | 3 | 97 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 77 |

| Frag. 2 | 23 | 71 | 6 | 923 | 42 | 12,261 | 6 | 94 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 79 | |

| TRC | 15 | 70 | 16 | 1000 | 45 | 4021 | 67 | 33 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 1 | 13 | 23 | |

| Av. | 32 | 60 | 10 | 1121 | 50 | 10,685 | 44 | 56 | 6 | 31 | 2 | 5 | 19 | 38 | |

| ± SD | ± 20 | ± 19 | ± 7 | ± 349 | ± 16 | ± 9748 | ± 30 | ± 30 | ± 5 | ± 20 | ± 2 | ± 4 | ± 14 | ± 25 | |

Isolat. meth. isolation method, exp expansion, sti stimulation, ca autologous carcinoma

aFull-scale rapid expansion procedure, including microbiological testing

bTIL functionality was determined as IFNγ secretion (pg/ml) following overnight incubation with the anti-CD3 antibody OKT-3

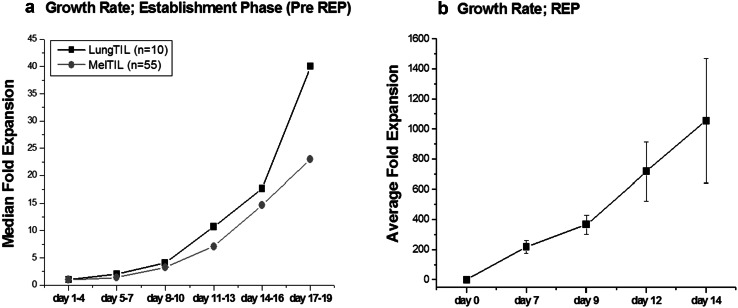

The growth rates of 10 individual lung TIL cultures, isolated by enzymatic digestion or TRC technique, were documented over a period of 19 days and compared with 55 TIL cultures derived from melanoma patients, who were previously treated with TIL ACT at our medical centre (Fig. 1a). Melanoma-derived TIL shown in Fig. 1a were also isolated by enzymatic digestion or TRC technique as described before [13]. TIL cultures established by fragmentation were not included in this analysis, as TIL detach from the tumor piece after a few days and thus can only be counted after about 1 week. The median cell count largely varied at culture initiation (lung TIL 1.9 × 10E6, range 0.45–4.3 × 10E6; melanoma TIL 3.8 × 10E6, range 0.2–125 × 10E6). As expected, the expansion rate of different TIL cultures varied largely; however, Fig. 1 represents fairly well the proliferation potential of lung and melanoma TIL. When comparing the growth rates of lung TIL cultures with melanoma TIL cultures there was no difference between the groups (p values ≥ 0.5), demonstrating that lung TIL expanded as well as melanoma TIL (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Growth rate of lung TIL and their functionality. a Growth rate of lung carcinoma-derived (lung TIL) and melanoma-derived (Mel TIL) TIL cultures from the day of surgery (day 1) to establishment (pre-REP). b Growth rate during the rapid expansion procedure (REP). Average fold expansion of 15 lung TIL. Total viable cell numbers was determined by microscopic cell count and trypan blue exclusion (triplicates)

Within 18–21 days, an average of 239 × 10E6 lung TIL (range 86–481 × 10E6 TIL) was established per patient (Table 1). Despite the very small size of the tumor biopsies (average 1.5 ± 1.19 cm3; in three patients even less than 1 cm3, Suppl. Table 1), 45 × 10E6 and more TIL were generated after only 14 ± 4 days for all patients. 45 × 10E6 is the cell number typically required to initiate the large-scale rapid expansion procedure.

Large cell expansion of lung TIL for adoptive cell transfer

Following successful TIL establishment from all five patients, we tested whether lung TIL can be expanded to clinical scale, using a standard 14-day rapid expansion procedure (REP) with irradiated PBMC feeders, soluble anti-CD3 antibody, and IL-2. Fifteen TIL cultures, three from each patient, were expanded in a full-scale REP or partial REP (Fig. 1b). An overall fold expansion of 1121 ± 349 was achieved after 14 days, providing an average of 5.04 × 10E10 ± 1.57 × 10E10 TILs for potential infusion into patients (Table 2; Fig. 1b). The fold expansion and consequently the final cell number were similar to the ones of 103 melanoma TIL, derived from patients treated with TIL ACT (1081 ± 493-fold expansion; 4.86 ± 2.22 × 10E10 TIL; p = 0.76) (Table 3). There was no significant correlation between the fold expansion during REP and the method of initial TIL isolation (Digest, TRC or fragmentation, p values ≥ 0.5).

Table 3.

Comparison of post-REP TIL derived from lung carcinoma and melanoma patients

| Lung TIL | Mel TIL | p values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fold expansion during REP | 1121 ± 349 | 1081 ± 493 | 0.76 |

| Final cell number (× 10E10) | 5.04 ± 1.57 | 4.86 ± 2.22 | 0.76 |

| CD8+CD3+ | 44 ± 30% | 59 ± 25% | < 0.001 |

| CD4+CD3+ | 56 ± 30% | 41 ± 25% | < 0.001 |

| CD28+CD3+ | 37 ± 19% | 58 ± 25% | 0.008 |

| 4-1BB+CD3+ | 6.5 ± 3.8% | 12 ± 15% | 0.140 |

| PD1+CD3+ | 57 ± 21% | 42 ± 25% | 0.096 |

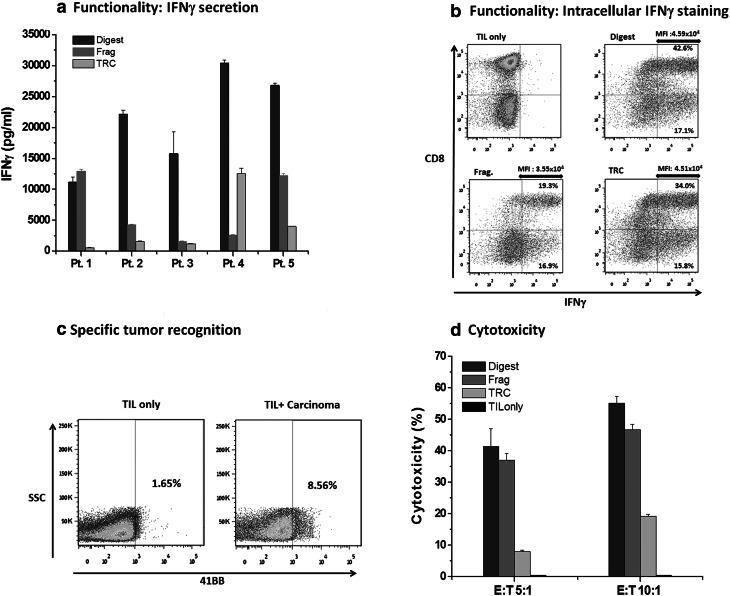

Functionality of all 15 post-REP TIL was evaluated, by activating TIL with an anti-CD3 antibody (10 ng/ml; clone OKT-3) followed by IFNγ level measurements (Table 2; Fig. 2a). The average secretion of IFNγ was 10,685 ± 9748 pg/ml (range 561–30,445 pg/ml), demonstrating that all TIL were functional. TIL isolated by enzymatic digestion showed increased IFNγ (21,309 ± 7856 pg/ml) over TRC (6754 ± 5444 pg/ml; p ≤ 0.01) and fragment-derived TIL (3993 ± 4988 pg/ml; p ≤ 0.01). Intracellular IFNγ flow cytometry staining was performed after OKT-3 stimulation of TIL from patients #1, #2, and #4, and could demonstrate in all three patients that the differences in IFNγ secretion levels can be explained by the secretion of IFNγ by more cells (higher percentage of IFNγ positive cells), as well as higher production of IFNγ by the positive cells (higher mean fluoresce intensity) (Fig. 2b). FACS results of one representative patient (#4) are shown in Fig. 2b.

Fig. 2.

Functionality and anti-tumor reactivity of post-REP lung TIL. a Lung TIL functionality measured by IFNγ secretion. TIL cultures after REP were stimulated overnight with the anti-CD3 antibody OKT3 (10 ng/ml) and IFNγ secretion (pg/ml) was measured by ELISA. Error bars represents the standard deviation of triplicate repetitions. b Lung TIL functionality measured by intracellular IFNγ flow cytometry after OKT-3 stimulation of post-REP TIL from patient #4 (MFI mean fluoresce intensity of IFNγ positive cells). c Frequency of TIL recognizing the autologous tumors. Fragment-derived TIL from patient #2 were co-cultured overnight with autologous tumor cells (E:T = 5:1) and 4-1BB expression was determined. d Cell-mediated cytotoxicity assay of Digest, Fragment, and TRC-derived post-REP TIL of patient #2. Error bars represents the standard deviation of triplicate repetitions

Full-scale rapid expansions, including microbiology testing, were performed for three lung TIL cultures from different patients. Sterility, mycoplasma, endotoxin, and gram stain were tested during the expansion process and on the final products in accordance with European Medicines Agency (EMA) regulations. All tests passed, which guarantees the sterility of the products.

Phenotypic characterization of lung TIL cultures

TIL cultures were analyzed for CD3, CD4, CD8, and CD56 expressions at REP initiation (REP day 0, pre-REP) and on day 14 of REP, the potential day of infusion (Table 2). The average frequency of CD8+CD3+ cytotoxic T cells was 32 ± 20% pre-REP and increased to 44 ± 30% post-REP (p = 0.18). Sixty ± 19% of the pre-REP TIL cultures contained CD4+CD3+ T helper cells and 56 ± 30% in post-REP cultures. CD56+CD3− NK cells were only present in pre-REP TIL cultures (10 ± 7%). The frequency of CD8+ or CD4+ T cells pre-REP did not affect the fold expansion during REP (p = 0.92 and p = 0.57, respectively).

In comparison, the average frequency of CD8+CD3+ in melanoma TIL infusion products of 103 treated patients was with 59 ± 25% significantly higher than in post-REP lung TIL (44 ± 30%, p < 0.001) (Table 3).

The expression of the co-stimulatory molecules, CD28 and 4-1BB (CD137), and the co-inhibitory molecule PD-1 were further examined in post-REP TIL.

The frequency of CD28+CD3+ T cells (CD4 and CD8) in lung TIL was 37 ± 19% (compared with 58 ± 25% in melanoma TIL; p = 0.008), of 4-1BB+CD3+ 6.5 ± 3.8% (compared with 12 ± 15% in melanoma TIL; p = 0.14), and of PD1+CD3+ 57 ± 21% (compared with 42 ± 25% in melanoma TIL; p = 0.096) (Table 3). The frequencies of CD28, 4-1BB, and PD-1 within the CD4+ helper and CD8+ cytotoxic T cell subpopulations of post-REP lung TIL are shown in Table 2.

Establishment of carcinoma lines and evaluation of anti-tumor reactivity

To evaluate specific anti-tumor reactivity of lung TIL, autologous carcinoma cell lines were established. We were able to separate tumor cell lines by the various isolation methods from three (patients #2, #3, and #4) out of five NSCLC patients (Suppl. Table 2). Special culture medium was required for the generation (see “Materials and methods”). Cytology and immunohistochemistry were performed by a certified pathologist on the established tumor cell cultures and cytokeratin 7; napsin and TTF1 stains were applied to confirm the nature of the carcinoma. The tumor cells of patients #2 and #3 could only be passaged once and of patient #4 six times. Cell morphology of lung carcinoma in culture is display in Suppl. Figure 1a and a mixture of TIL and tumor cells in Suppl. Figure 1b. Anti-tumor reactivity was determined after co-culture of post-REP TIL from patients #2, #3, and #4 with their corresponding autologous carcinoma line and measuring of IFNγ secretion. Most clinical protocols define TIL secreting IFNγ above 200 pg/ml upon co-incubation with autologous tumor lines as anti-tumor reactive. Three out of nine TIL cultures (two of patient #2 and one of patient #4) demonstrated anti-tumor reactivity (Table 4, last column). Thus, two out of three NSCLC patients had at least one TIL culture with evidence of reactivity in response to autologous carcinoma lines. Those TIL cultures did not secrete IFNγ in response to HLA-mismatched carcinoma lines or TIL alone (data not shown). To determine the actual percentage of cells recognizing the autologous tumors, Fragment-derived TIL from patient #2 were co-cultured with its autologous carcinoma line and 4-1BB (CD137) expression was analyzed after 8 h by flow cytometry. 4-1BB is a co-stimulatory marker which is induced upon the specific interaction of T cells with their target cell [22]. As shown in Fig. 2c, 8.5% of the TIL recognized the tumor. There was no significant difference regarding the phenotype (CD4, CD8, 4-1BB, PD-1, CD28) or fold expansion between the three reactive TIL cultures and the six non-reactive TIL cultures (p values ≥ 0.1). The anti-tumor reactivity of Digest, Fragment, and TRC-TIL of patient #2 was confirmed by a cell-mediated cytotoxicity assay (Fig. 2d).

Table 4.

Anti-tumor reactivity

| Pt. | Isolation method | IFNγ (pg/ml) in the supernatant of early TIL cultures | IFNγ (pg/ml) after CC of post-REP TIL and autol. ca. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Digest | 393 | 489 |

| TRC | 0 | 0 | |

| Frag. 5 | 52 | 244 | |

| 3 | Digest | ND | 0 |

| TRC | ND | 0 | |

| Frag. 3 | ND | 0 | |

| 4 | Digest | 1098 | 10 |

| TRC | 900 | 1246 | |

| Frag. 4 | 521 | 0 |

CC = overnight co-culture of 1 × 10E5 TIL with 1 × 10E5 autologous carcinoma (autol. ca.)

ND not determined

We tested, if evidence of anti-tumor reactivity may be detected at an early time point of TIL generation, by testing the supernatants of early TIL cultures for IFNγ secretion. For this purpose, supernatants from TIL cultures of patients #2 and #4 were collected 6 days after surgery. At this time point, TIL cultures are mostly heterogenic and still contain TIL as well as carcinoma cells. Although this “natural” co-culture is not quantitative, we measured IFNγ in the supernatant of TIL cultures from patients #2 and #4.

Interestingly, in the supernatant of Digest-TIL and Fragment-TIL of patient #2, IFNγ was detectable in the supernatant (395 and 52 pg/ml, respectively) as well as in the co-culture post-REP (489 and 244 pg/ml, respectively), whereas TCR-TIL was negative in both assays (Table 4). For patient #4, the supernatants of Digest-TIL, TRC-TIL, and Fragment-TIL showed evidence of IFNγ (1098, 900, and 521 pg/ml, respectively), but only TRC-TIL secreted IFNγ following co-culture with the autologous carcinoma line post-REP (1246 pg/ml, Table 4). Post-REP, Fragment-TIL completely lost the capability to secrete IFNγ upon co-incubation and the levels of IFNγ in Digest-TIL dropped to 10 pg/ml. Interestingly, in all three post-REP reactive TIL cultures, IFNγ secretion was already detectable in the early TIL culture. Thus, the measurement of IFNγ levels in the supernatant of early TIL cultures is not quantitative, but may hint to the anti-tumor reactivity of post-REP TIL product.

Discussion

Our cancer center has collected vast clinical and laboratorial experience in the treatment of melanoma patients with TIL ACT. To date 103 melanoma patients received TIL infusion and objective response rates of 30% were achieved in highly advanced metastatic patients, who failed prior treatments, with IL-2-based therapy, targeted therapy, or checkpoint molecules. In the current report, we tested the feasibility to isolate and expand lung carcinoma-derived TIL to treatment levels under GMP conditions.

Among other solid tumors, lung cancer was chosen for this study, as there still is a significant clinical need and this cancer type has been proven to be susceptible to immunotherapy with PD-1/PDL-1 antibodies [3, 4]. In addition, lung adeno and squamous cell carcinoma have after melanoma the highest mutation load [9]. Since mutated neo-antigenic peptides, which arise from tumor mutations, are ideal targets for TIL [23], lung cancer seems to be the optimal candidate for TIL ACT.

TIL generation was investigated in five patients with advanced stage NSCLC undergoing thoracic surgery with curative intention. Tumor tissues, with an average size of 1.5 ± 1.19 cm3, were processed by various methods and TIL were cultured in IL-2 containing medium. The proliferative potential of lung TIL was documented over a period of 3 weeks. We could show that lung TIL proliferate as well as TIL derived from melanoma patients. When comparing the results of lung TIL to melanoma TIL, one should keep in mind, that the lung tumors, described here were primary tumors, while melanomas were mostly of metastatic origin.

For all five patients, 45 × 10E6 TIL (the number of cells typically required to initiate a large-scale rapid expansion) were obtained after 2 weeks and an average of 239 × 10E6 TIL after 3 weeks. Thus, TIL establishment was successful in five out of five NSLCL patients, despite the small size of the tumors.

Fifteen individual lung TIL cultures (three of each patient) were successfully expanded in a standard 14-day rapid expansion procedure, and the fold expansion, phenotype (CD3, CD4, CD8, 4-1BB, CD28, PD-1), and functionality of post-REP TIL were determined. Full microbiological testing, in accordance with EMA regulations were successfully performed to assure the sterility of the potential infusion product. Autologous carcinoma lines were established from three patients and specific anti-tumor reactivity, measured as IFNγ secretion in response to co-incubation with the corresponding tumor line, was evident in TIL cultures from two of three patients. If IFNγ levels, measured in the supernatant of early TIL cultures, consisting of a heterogeneous mixture of TIL and tumor cells, may hint to the reactivity of post-REP TIL, require further evaluation. This would be of importance, as the establishment of primary lung carcinoma cell lines, required to perform anti-tumor reactivity assays, is challenging and the success rate often low.

In summary, the well-established melanoma TIL protocol was demonstrated to be adoptable for the lung cancer setting.

This study provides the basis for the development of TIL ACT for patients with advanced NSCLC, which may offer an additional treatment option for those patients. Based on this report, we plan to initiate an adoptive TIL therapy trial for patients with respectable lung cancer in the near future.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Abbreviations

- ACT

Adoptive cell therapy

- CM

Complete medium

- REP

Rapid expansion procedure

- TIL

Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes

- TRC

Tissue remnant culture

Author contributions

RB-A, OI, and MJB designed the study. RB-A, OI, RF, AB-N, MG, and EG acquired the data. RB-A, OI, RF, GM, JS, and MJB analyzed and interpreted the data. All the authors revised the work, approved the final version, and agreed to be accountable of the work.

Funding

The authors would like to thank Haya and Nehemia Lemelbaum for their generous support.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The protocol was approved by the IRB Committee of the Sheba Medical Center, Israel. Approval number: SMC-0921-13.

Informed consent

Patients signed an informed consent under the approved protocol SMC-0921-13.

Contributor Information

Orit Itzhaki, Email: orit.itzhaki@sheba.health.gov.il.

Michal J. Besser, Email: michal.besser@sheba.health.gov.il

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doebele RC, Oton AB, Peled N, Camidge DR, Bunn PA., Jr New strategies to overcome limitations of reversible EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2010;69:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antonia SJ, Vansteenkiste JF, Moon E. Immunotherapy: beyond anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 therapies. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book Am Soc Clin Oncol Meet. 2016;35:e450e458. doi: 10.14694/EDBK_158712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giri A, Walia SS, Gajra A. Clinical trials investigating immune checkpoint inhibitors in non-small-cell lung cancer. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2016;11:297–305. doi: 10.2174/1574887111666160724181330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mayor M, Yang N, Sterman D, Jones DR, Adusumilli PS. Immunotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer: current concepts and clinical trials. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;49:1324–1333. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezv371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shin DS, Ribas A. The evolution of checkpoint blockade as a cancer therapy: what’s here, what’s next? Curr Opin Immunol. 2015;33:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horne ZD, Jack R, Gray ZT, et al. Increased levels of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are associated with improved recurrence-free survival in stage 1A non-small-cell lung cancer. J Surg Res. 2011;171:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.03.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kilic A, Landreneau RJ, Luketich JD, Pennathur A, Schuchert MJ. Density of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes correlates with disease recurrence and survival in patients with large non-small-cell lung cancer tumors. J Surg Res. 2011;167:207–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lawrence MS, Stojanov P, Polak P, et al. Mutational heterogeneity in cancer and the search for new cancer-associated genes. Nature. 2013;499:214–218. doi: 10.1038/nature12213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu YC, Yao X, Crystal JS, et al. Efficient identification of mutated cancer antigens recognized by T cells associated with durable tumor regressions. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:3401–3410. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robbins PF, Lu YC, El-Gamil M, et al. Mining exomic sequencing data to identify mutated antigens recognized by adoptively transferred tumor-reactive T cells. Nat Med. 2013;19:747–752. doi: 10.1038/nm.3161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Yang JC, et al. Adoptive cell transfer therapy following non-myeloablative but lymphodepleting chemotherapy for the treatment of patients with refractory metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2346–2357. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Itzhaki O, Hovav E, Ziporen Y, et al. Establishment and large-scale expansion of minimally cultured “young” tumor infiltrating lymphocytes for adoptive transfer therapy. J Immunother. 2011;34:212220. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318209c94c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andersen R, Donia M, Ellebaek E, et al. Long-lasting complete responses in patients with metastatic melanoma after adoptive cell therapy with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and an attenuated IL2 regimen. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:3734–3745. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Besser MJ, Shapira-Frommer R, Itzhaki O, et al. Adoptive transfer of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in patients with metastatic melanoma: intent-to-treat analysis and efficacy after failure to prior immunotherapies. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:4792–4800. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dudley ME, Gross CA, Somerville RP, et al. Randomized selection design trial evaluating CD8+-enriched versus unselected tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes for adoptive cell therapy for patients with melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2152–2159. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.6441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goff SL, Dudley ME, Citrin DE, et al. Randomized, prospective evaluation comparing intensity of lymphodepletion before adoptive transfer of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes for patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2389–2397. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.66.7220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pilon-Thomas S, Kuhn L, Ellwanger S, et al. Efficacy of adoptive cell transfer of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes after lymphopenia induction for metastatic melanoma. J Immunother. 2012;35:615620. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31826e8f5f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radvanyi LG, Bernatchez C, Zhang M, et al. Specific lymphocyte subsets predict response to adoptive cell therapy using expanded autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in metastatic melanoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:6758–6770. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ratto GB, Zino P, Mirabelli S, et al. A randomized trial of adoptive immunotherapy with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and interleukin-2 versus standard therapy in the postoperative treatment of resected nonsmall cell lung carcinoma. Cancer–. 1996;78:244251. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960715)78:2<244::AID-CNCR9>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jin J, Sabatino M, Somerville R, Wilson JR, Dudley ME, Stroncek DF, Rosenberg SA. Simplified method of the growth of human tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in gas-permeable flasks to numbers needed for patient treatment. J Immunother. 2012;35:283292. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31824e801f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seliktar-Ofir S, Merhavi-Shoham E, Itzhaki O, et al. Selection of shared and neoantigen reactive T cells for adoptive cell therapy based on CD137 separation. Front Immunol. 2017 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hinrichs CS, Restifo NP. Reassessing target antigens for adoptive T-cell therapy. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:999–1008. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.