Abstract

The carbonic anhydrases (CAs) constitute a family of almost ubiquitous enzymes of significant importance for many physiological and pathological processes. CAs reversely catalyse the conversion of CO2 + H2O to HCO3 − and H+, thereby contributing to the regulation of intracellular pH. Above all, CAs are of key importance for cells that perform glycolysis that inevitably leads to the intracellular accumulation of lactate. CA XII is a plasma membrane-associated isoform of the enzyme, which is induced by hypoxia and oestrogen and, consequently, expressed at high levels on various types of cancer and, intriguingly, on cancer stem cells. The enzyme is directly involved in tumour progression, and its inhibition has an anti-tumour effect. Apart from its role in carcinogenesis, the enzyme contributes to various other diseases like glaucoma and arteriosclerotic plaques, among others. CA XII is therefore regarded as promising target for specific therapies. We have now generated the first monoclonal antibody (6A10) that binds to the catalytic domain of CA XII on vital tumour cells and inhibits CA XII enzyme activity at nanomolar concentrations and thus much more effective than acetazolamide. In vitro results demonstrate that inhibition of CA XII by 6A10 inhibits the growth of tumour cells in 3-dimensional structures. In conclusion, we generated the first specific and efficient biological inhibitor of tumour-associated CA XII. This antibody may serve as a valuable tool for in vivo diagnosis and adjuvant treatment of different types of cancer.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00262-011-0980-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Carbonic anhydrase, Monoclonal antibody, Cancer treatment, Hypoxia, Warburg effect

Introduction

It has been known for many years that the cellular metabolism in solid tumours is significantly different from that in surrounding normal tissues. Orchestrated by the transcription factor HIF-1α, cancer cells produce a large part of the cellular energy, both in the absence and in the presence of sufficient oxygen, by glycolysis rather than mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. This phenomenon termed ‘aerobic glycolysis’ was originally observed by Otto Warburg [1] and is thus also referred to as the ‘Warburg effect’. Aggressive tumours almost always exhibit this glycolytic switch. Obviously, this phenotype confers a selective advantage, even though it is not economically profitable, given the inefficient production of ATP. Glycolysis also causes the excess intracellular generation of lactate, the principle end product of glycolysis, which cannot be exported into the interstitial fluid rapidly enough [2].

In order to stabilize the intracellular pH, cancer cells rely on buffers like bicarbonate, whose extracellular generation from CO2 is catalysed by carbonic anhydrases (CAs, EC 4.2.1.1). The α-CAs are ubiquitous zinc metalloenzymes that catalyse the reversible hydration of carbon dioxide to generate bicarbonate anions and protons. CAs are reliable targets for treatment of quite a range of human diseases such as arteriosclerotic plaques [3], glaucoma [4] and, recently, cancer. The clinical modulation has so far been achieved with sulphonamides [5, for review]. In humans, 16 different isoenzymes have been detected to date, with different distributions, catalytic activity and cellular localization. CA XII is a membrane-associated homodimeric ectoenzyme [6, 7], which is hypoxia-induced and upregulated in many types of cancer [8]. In order to counter intracellular acidosis and to stabilize their intracellular pH, hypoxic cancer cells rely on transmembrane enzymes like CA IX and XII that efficiently generate bicarbonate ions, which are subsequently transported into the cell. Thus, the expression of these CAs and the glycolytic phenotype are closely linked. It has been shown that CA XII promotes tumour cell migration and invasion in vitro, and that knockdown of the gene suppresses growth and invasion of cancer cells by inhibiting the p38/MAPK pathway [9]. These results support the view that the CAs directly trigger tumour progression by contributing to the acidification of the tumour microenvironment, to intracellular pH regulation and possibly to additional tumour-promoting effects [10–12].

Whereas the regulation, tissue distribution and role in tumour progression of CA IX have been investigated in great detail and the CA IX-specific antibody G250 is under clinical development for therapeutic and diagnostic application, much less is known about CA XII. This may be a consequence of lacking antibodies that bind to the extracellular part of CA XII. Originally detected by serological expression screening with autologous antibodies from patients with renal cell cancer, [13] the enzyme has been found expressed at low or moderate levels in some normal tissues [14, 15] and overexpressed on various human cancers [8, 15–23]. CA12, the gene encoding CA XII, is a HIF-1 target and, in contrast to CA9, is also induced by oestrogen [16]. Thus, CA12 is highly expressed in renal cell cancer with defective VHL [24] and in oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancer [16, 25, 26].

Because of their central roles in hypoxia and tumour acidosis, invasion and metastasis, CA IX and CA XII are nowadays regarded as promising targets for the development of new anti-cancer agents. Their membrane-associated localization with catalytic domains accessible from the outside makes the enzymes pre-disposed for targeted therapies by e.g. monoclonal antibodies. Here, we characterize the anti-CA XII antibody 6A10 and show that it is the first and only specific biological inhibitor of tumour-associated CA XII.

Materials and methods

Antibody 6A10

For the generation of the monoclonal antibody 6A10, LOU rats were immunized i.p. with 5 × 106 A549 lung cancer cells with 500 μl incomplete Freund’s adjuvant and boosted 6 weeks later with the same number of cells. Splenic B-cells were fused with the myeloma cell line P3x63.653 according to standard procedures for the generation of monoclonal antibodies. Supernatants from growing hybridoma were investigated for binding to vital A549 cells by flow cytometry. 6A10 is of an IgG2a-kapppa isotype. The antibody is subject to patent application EP10004646.5.

Cell lines and flow cytometry

FaDu, A549 and L929 cells were obtained from ATCC. PCI1 and PCI13 cells were established at the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute and a kind gift of T. Whiteside. The remaining HNC cell lines were a kind gift of T.K. Hoffmann (University of Duisburg-Essen). The glioblastoma cell lines U87, U251 and U373 were a gift of E. Noessner (Munich). The neuroblastoma cell lines SK-N-SH and SK-SY5Y were a gift of J. Mautner (Munich). All cell lines were kept in RPMI cell culture medium supplemented with 10% FCS and Penicillin/Streptomycin (Invitrogen, Darmstadt, Germany) in a humidified atmosphere at 37°C and 5% CO2. Binding of antibodies was measured by standard flow cytometry (FACS) with a Becton–Dickinson FACSCanto and analysed with the FlowJo software. The CA XII-specific antibody MAB2190 was purchased from R&D Systems (Wiesbaden, Germany).

Immunofluorescence

Tumour tissues from head and neck cancer patients were obtained during surgery and immediately mounted in TissueTek (Sakura, Staufen, Germany) freezing medium. The samples were sectioned at a thickness of 5 μm and placed onto microscope slides. The sections were stained with 6A10 and a, anti-rat IgG FITC-labelled secondary antibody and finally examined under light and fluorescence microscopy with a Zeiss Axioscope 2 microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany). All experiments were approved by the ethics committee of the Medical Faculty of the University Hospital Essen, and informed written consent was obtained from each individual. The patients’ clinical data are given in Table S2. A549 cells were grown on microscope glass slides and fixed with methanol:acetate (1:1) for 15 min. 6A10 was used at a dilution of 1:5 and detected with a Cy5-conjugated secondary antibody (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany).

Soft-agar clonogenic assay

Wells of a 12-well cell culture plate were prepared with 1 ml/well of bottom agar (0.5% in RPMI/10% FCS). Top agar was prepared by resuspending 5,000 cells in 500 μl RPMI/20% FCS and mixed with the same volume of 1% agarose in RPMI, pre-warmed at 42°C, yielding a suspension of cells in RPMI/10% FCS and 0.5% agarose. This suspension was immediately put onto the bottom agar, and plates were incubated for up to 6 weeks. For the calculation of colonies, the plates were scanned and colonies >50 pixels were counted with the Image J software.

Multicellular tumour spheroids and MTT assay

For the spontaneous formation of MCS, 20,000 cells/well were cultivated in 96-well culture plates in standard medium on an agarose cushion, consisting of 1% agarose in RPMI and cultivated for 48 h. Cell survival and proliferation of cells within the spheroids were measured in a standard MTT assay as described [27]. In brief, 100 μl MTT solution (5 mg/ml MTT in PBS) was added per well, and cells were incubated for 3 h at 37°C to allow formation of formazan. Then, 100 μl of 10% SDS was added, and the plates were incubated at room temperature overnight. The solutions were then transferred to a new 96-well plate and read on a Biotek EL800 Elisa reader at 590 nm.

A549 side population

Analysis of the side population was performed as described elsewhere [28]. Briefly, 1 × 106 cells were incubated in pre-warmed RPMI with 7.5 μg/ml Hoechst 33342 for 90 min at 37°C. Cells were then washed three times in cold HBSS, resuspended in HBSS with 2 μg/ml propidium iodide (PI) and kept on ice. Flow cytometry was performed on a FACS LSR II (Becton–Dickinson). The Hoechst dye was excited with a 350-nm laser, and its fluorescence was measured with 450- and 670-nm filters. Only PI-negative cells were analysed.

CA activity test

CA XII has been cloned as GST-tagged protein as previously described [29, 30]. Briefly, the enzyme was purified in two steps, and its activity/inhibition was assayed by a stopped flow method, monitoring the physiological reaction, i.e., CO2 hydration to bicarbonate and protons [31]. An Applied Photophysics stopped-flow instrument was used for assaying the CA-catalysed CO2 hydration activity [31]. Phenol red (at a concentration of 0.2 mM) was used as indicator, working at the absorbance maximum of 557 nm, with 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.4) and 20 mM NaBF4 (for maintaining constant the ionic strength), following the initial rates of the CA-catalysed CO2 hydration reaction for a period of 10–100 s. The CO2 concentrations ranged from 1.7 to 17 mM for the determination of the kinetic parameters and inhibition constants. For each inhibitor, at least six traces of the initial 5–10% of the reaction were used for determining the initial velocity. The uncatalysed rates were determined in the same manner and subtracted from the total observed rates. Stock solutions of antibody were diluted up to 0.01 nM with the assay buffer. Inhibitor and enzyme solutions were pre-incubated together for 15 min at room temperature prior to assay, in order to allow for the formation of the E-I complex. The inhibition constants were obtained by non-linear least-squares methods using PRISM 3, whereas the kinetic parameters for the uninhibited enzymes from Lineweaver–Burk plots, as reported earlier [29, 30], and represent the mean from at least three different determinations. Other CA isoforms were recombinant ones reported earlier by this group [32, 33].

Results

6A10 binds to membrane CA XII on vital tumour cells

In an attempt to generate new antibodies targeting surface proteins on cancer cells, we immunized LOU rats with A549 lung cancer cells. As a result, we obtained a series of stable monoclonal hybridoma producing IgG antibodies that bound to the surface of vital A549 cells as tested by FACS analysis (data not shown). One of these antibodies, termed 6A10, also bound to a series of other human cancer cell lines but not to normal PBMCs (Table S1) and was investigated in more detail. First, immunoprecipitation from A549 lysates of the protein recognized by the antibody and subsequent mass spectrometry revealed that 6A10 specifically bound to carbonic anhydrase XII (CA XII), which is expressed on the surface of many human tumour cells and induced by hypoxia [34]. In order to confirm the mass spectrometry data, we transfected murine L929 fibroblasts with a CA XII expression plasmid, generated by RT–PCR-mediated amplification of the ca12 cDNA from A549 cells. The results showed that 6A10 bound to transfected but not to parental L929 cells (Fig. 1a). Immunofluorescence staining of A549 revealed the surface localization of CA XII on A549 cells (Fig. 1b). Of interest, the protein is mainly expressed in regions of direct cell–cell contact where hypoxic conditions might occur.

Fig. 1.

6A10 binds to the extracellular part of CA XII. a In order to prove the specificity of 6A10, murine L929 cells were transfected with an expression plasmid encoding human CA XII. Binding of 6A10 to transfected cells (black line) and parental cells (grey histogram) was evaluated by FACS. b Immunofluorescence imaging revealed the surface localization of CA XII on A549 cells. Of interest, the enzyme is particularly overexpressed in regions of close cell–cell contact and thus in regions of potential local hypoxia

We next analysed a series of permanent human cancer cell lines from different tumour types and found that CA XII was expressed on the vast majority even under normoxic conditions (Supplementary Data Table S1). No expression was detectable on PBMCs. Supporting the essential role of CA XII for hypoxic cancer cells, we observed a notable induction of the enzymes on some glioblastoma cell lines (Fig. S1). These lines stained negative for 6A10 under normoxia whereas a strong staining could be observed after cultivation for 24 under in the presence of the hypoxia-mimetic DFOM at 100 μM. These data are consistent with the published results demonstrating CA XII expression in primary glioblastoma but not in normal brain tissue [22], a tumour type particularly linked with hypoxia [35].

6A10 efficiently blocks the catalytic activity of CA XII

CA XII is located on the surface of cancer cells with the catalytic domain on the extracellular leaflet of the plasma membrane. The tumour-promoting properties of CA XII are attributable to its enzymatic activity. Thus, we tested whether 6A10, which binds to the extracellular part of CA XII, may inhibit its catalytic activity. To this end, we performed an activity/inhibition assay with CA XII and other isoenzymes by a stopped flow method, monitoring the CO2 hydration to bicarbonate and protons. This assay revealed that 6A10 blocks CA XII activity very efficiently with a Ki = 3.1 nM and thus about twice as efficient as acetazolamide (Ki = 5.7 nM), a highly effective inhibitor of that enzyme. In addition, the antibody weakly inhibited the isoenzymes VI, VII, IX, XIII and XIV (Table 1). Intriguingly, 6A10 displays a very advantageous inhibition profile, as CA I–IV, which are essential for different physiological processes such as respiration and regulation of the acid/base homeostasis [36, for review], are not inhibited. The commercially available CA XII antibody MAB2190 did not show any inhibitory activity in this assay.

Table 1.

Inhibition data against isoforms CA I–XV with 6A10, MAB2190 and acetazolamide (AAZ)

| Isoform/inhibitor | Subcellular localization | Ki (nM) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6A10 | MAB2190 | AAZ | ||

| hCA I | Cytosol | >10,000 | >10,000 | 250 |

| hCA II | Cytosol | >10,000 | >10,000 | 12 |

| hCA III | Cytosol | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| hCA IV | GPI-anchored | >10,000 | >10,000 | 74 |

| hCA VA | Mitochondria | >10,000 | >10,000 | 63 |

| hCA VB | Mitochondria | >10,000 | >10,000 | 54 |

| hCA VI | Secreted | 520 | >10,000 | 11 |

| hCA VII | Cytosol | 540 | >10,000 | 2.5 |

| hCA IX | TM | 640 | >10,000 | 25 |

| hCA XII | TM | 3.1 | >10,000 | 5.7 |

| mCA XIII | Cytosol | 720 | >10,000 | 17 |

| hCA XIV | TM | 650 | >10,000 | 41 |

| mCA XV | MB | >10,000 | >10,000 | 72 |

h human, m murine isoform, MB membrane bound, TM transmembrane

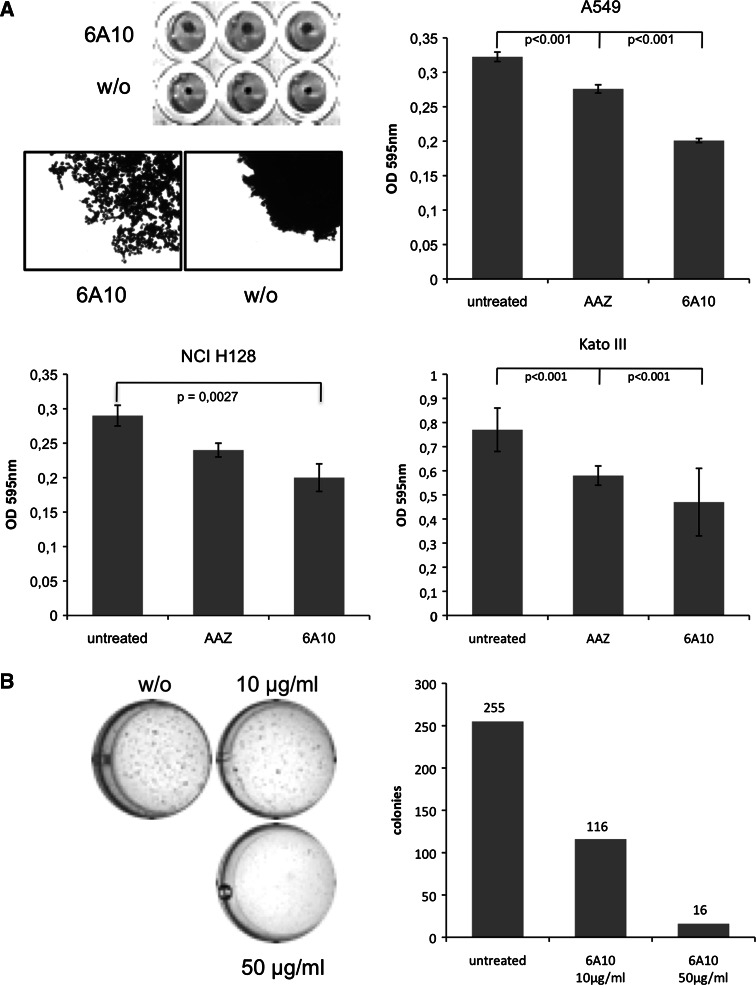

6A10 inhibits the 3-dimensional growth of tumour cells

In an effort to determine the anti-tumour activity of 6A10, we performed 3-dimensional cell cultures, namely multicellular tumour spheroids (MCS), which are regarded as in vitro surrogates for non-vascularized micrometastases and soft-agar clonogenic assays. MCS form spontaneously when adherent tumour cells are cultivated on a cushion consisting of 1% agarose in PBS to which the cells fail to adhere. These spheroids encounter hypoxic conditions in their interior, although they are only approximately 0.1 mm of diameter [37, 38]. We generated A549 MCS from 2 × 105/well in a 96-well cell culture plate and cultured them for 48 h in the presence (10 μg/ml) or absence of 6A10 and then analysed in standard MTT assays. The results showed that 6A10 significantly inhibited the growth of A549-MCS. The mean value of 12 MCS incubated with 6A10 is shown. 6A10 also dramatically changed the phenotype of the MCS. Whereas untreated spheroids were dense, cells treated with 6A10 were much more sparse and obviously unable to grow as compact 3-dimensional structures (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

6A10 inhibits the 3-dimensional growth of cancer cells. a 2 × 105 cells were cultured on agarose to form MCS and cultured for 48 h. Then, MTT solution was added. Microscopic inspection revealed that MCS cultured in the presence of 6A10 (10 μg/ml) were much more sparse than those without antibody. Photometric analysis revealed significantly reduced viability of MCS cultured with the antibody. The growth inhibitory effect of 6A10 was more pronounced than that of AAZ at a concentration of 100 μM. b 5 × 103 A549 cells were cultured for 4 weeks in soft-agar without (w/o) or in the presence of 6A10 (10 or 50 μg/ml). The plate was scanned, and the colonies formed were counted as described. The number of colonies formed was dramatically reduced by 6A10

In a next series of experiments, we carried out soft-agar clonogenic assays to determine the effect of 6A10 on the tumourigenicity of cancer cells. To this end, we mixed 5 × 103 A549 cells with 1 ml of pre-warmed RPMI containing 0.35% agarose and put the cells onto a cushion consisting of RPMI with 0.5% agarose (bottom). To some of the wells, we added 6A10 at 10 or 50 μg/ml. After 3 weeks of culture in soft-agar, when A549 colonies became visible, we added MTT solution overnight and then submerged the cultures for 6 days in PBS, which we changed several times. This procedure led to the diffusion of the MTT solution from the agarose into PBS, whereas the intracellular formazan remained in the cells so that colonies were clearly visible. We then scanned the cultures, transformed the picture and quantified the cultures with Image J. The results showed that 6A10 significantly inhibited formation of A549 colonies. Another hint that CA XII is dispensable for tumour cells under normoxic conditions came from the observation that 6A10 exhibited a growth-inhibitory effect on cells growing as monolayer under hypoxic conditions (Fig. S2) but not under normoxia (data not shown).

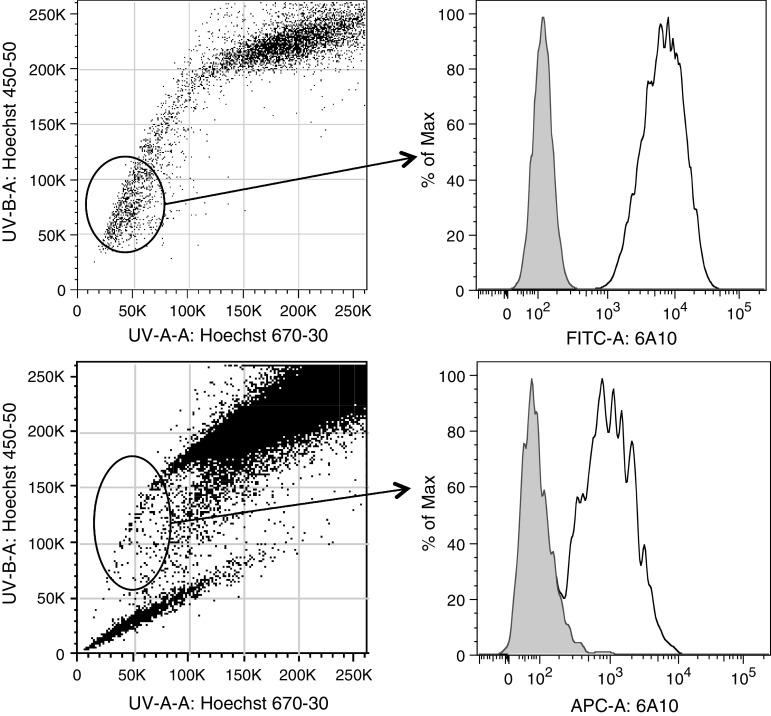

CA XII is highly expressed on cancer stem cells

Following the cancer stem cell (CSC) hypothesis, initiation and progression of tumours are driven by a small subpopulation of cancer cells with the potential for indefinite growth and proliferation. CSCs are also thought to be origin of local recurrent diseases and distant micrometastases. CSC can be distinguished from the rest of the cancer cells by the expression of characteristic antigens, such as CD24, CD44 and CD133 [39]. Furthermore, CSCs overexpress ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter proteins and can efflux anti-cancer drugs and fluorescent dyes like Hoechst 33342. Therefore, cells that efficiently exclude the Hoechst dye in vitro are referred to as the side population (SP), which is enriched for cells with tumour-initiating capacity [40].

We have used the A549 lung cancer cell line, which contains a decent number of CSCs [41], to investigate the expression of CA XII on the cancer stem cell population. To this end, we incubated A549 cells for 90 min with Hoechst 33342 at a concentration of 10 μg/ml, then stained the cells with 6A10 and analysed them by FACS as previously described [28]. This experiment revealed that the A549 cell line contained approximately 5% of CSC, characterized by the efficient efflux of the Hoechst dye. Analysis of 6A10 binding demonstrated that CA XII is expressed on CSCs at high levels (Fig. 3, right histogram).

Fig. 3.

CA XII is expressed on cancer stem cells. A549 lung cancer cells (upper panel) and U87 glioblastoma cells (lower panel) were stained with Hoechst 33342 and with 6A10. CSC was defined according to their increased potential do excrete the Hoechst dye. CA XII expression was measured with 6A10 is clearly detectable on CSCs

CA XII is highly expressed on head and neck cancer

Hypoxia increases radio- and chemoresistance and is therefore regarded as an adverse prognostic factor for survival and local control [42]. HNC is a tumour type that is particularly resistant to chemo- and radiotherapy and hypoxia and concomitant expression of HIF-1α and downstream target genes are common [43, 44]. Whereas the expression of HIF-1α, VEGF-1 and CA IX has been well investigated in HNC [45, 46], nothing is known about CA XII, which is also hypoxia-induced and is a negative prognostic factor in e.g. astrocytoma [47]. Since these molecules are often co-expressed in hypoxic tumour regions, we determined CA XII expression on primary HNC tissues by immunofluorescence and on permanent HNC cell lines by FACS analysis. We found that CA XII was highly expressed on 15 out of 15 cell lines and on 6 out of 6 primary HNC. Here, the tumour cells showed a strong expression of CA XII whereas the surrounding stroma did not (Fig. 4). These results implicate that CA XII is a potential promising target for the molecular diagnosis and treatment of HNC.

Fig. 4.

CA XII is strongly expressed on primary HNC and HNC cell lines. a Frozen sections of primary biopsies from squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck were stained with 6A10 and a FITC-labelled secondary antibody. Cells were counterstained with 7-AAD. The clinical data of the patients are given in Table S2 (upper panel patients 1–3; lower panel patients 4–6). b Permanent HNC cell lines express CA XII as measured with 6A10 by flow cytometry. The following cell lines were investigated: upper panel UD1, UD2, UD3, UD5, UD6; middle panel UM10A, UM11B, UM17B, UM22B, UT24A; lower panel UT50, AccChina, FaDu, PCI1, PCI13

Discussion

In contrast to normal tissues, cancer cells exhibit increased glycolysis, i.e. the conversion of glucose to pyruvate and lactate, which is not inhibited by the presence of oxygen. This phenomenon termed the ‘Warburg effect’ has been discovered already more than 80 years ago. Control of the glycolytic pathway is multifactorial with the most important upstream effectors being the c-myc family of proteins and HIF-1α, which cause a dramatic reprogramming of the tumour metabolism leading to enhanced expression of e.g. pro-angiogenic, growth-promoting and proteolytic factors [48, 49, for review]. Although still not completely understood, it is becoming increasingly clear that the Warburg effect describes a selection force that promotes carcinogenesis and invasion. By relying mainly on energy from glycolysis, invasive tumours have adopted the potential to proliferate in absence of oxygen and to simultaneously generate a protumoural microenvironment.

Cancer cells that mostly rely on energy from glycolysis generate excess amounts of intracellular lactate, which places great demands on the regulation and stabilization of the intracellular pH (pHi). Buffering of the pHi is usually achieved by the export of lactic acid and protons and the concomitant import of bicarbonate ions. In this respect, the tumour-associated transmembrane enzymes CA IX and CA XII play a crucial role in the stabilization of the pHi and the acidification of the extracellular intratumoural milieu. Hence, the enzymes are thought to directly promote tumour progression and spread as already vascularized micrometastases at sizes as small of <1 mm of diameter encounter hypoxia in their interior [50]. Also, CA XII expression on CSC may directly promote the survival and proliferation of disseminated hypoxic cancer stem cells in a hypoxic environment and foster the generation of metastases and 6A10 may suppress their growth by inhibiting its catalytic activity. Interestingly, our antibody inhibits tumour growth under three-dimensional culture conditions, but not in conventional monolayer cultures. This finding is consistent with CA XII’s higher expression at cell membrane regions involved in cell–cell contacts (Fig. 1), its regulation by hypoxia and its strong expression in HNSCC tissue. Based on their important role for the tumour cell metabolism, CA IX and XII are today regarded as promising targets for specific cancer treatments. An antibody (G250), which binds to the native extracellular part of CA IX, has been known for many years [51], and a chimeric version of this antibody is currently under clinical investigation for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes (see http://www.wilex.de). No antibodies targeting native CA XII were available so far.

Here, we present data on a new antibody, 6A10, which binds to the extracellular domain of CA XII and efficiently inhibits its catalytic activity at low nanomolar concentrations. To the best of our knowledge, no other small molecule tested to date blocks the enzyme as efficiently as 6A10. In addition, 6A10 is also highly specific, as the Ki for CA isoenzymes was much higher. In essence, 6A10 is the first biological inhibitor of CA XII and the first specific antibody, which allows detection and targeting of CA XII on living tumour cells. We also provide functional in vitro data demonstrating that 6A10 inhibits tumour cells to grow as three-dimensional MCS and as colonies in soft-agar. We also show that CA XII is highly expressed on cancer stem cells that are regarded as origin of metastases and local recurrent disease. Taken together, 6A10 may be used in the clinical setting for diagnostic purposes and possibly also for the specific adjuvant treatment of cancer. As a chimeric or humanized derivative, 6A10 may display dual anti-tumour activities: induction of ADCC and inhibition of CA XII, which is directly associated with tumour progression. We further show that the enzyme is expressed at high levels on all HNC cell lines and primary tumours investigated. CA XII is expressed on almost all astrocytoma [47] and glioblastoma [22] but absent from normal brain. Also, the enzyme also is highly expressed in glaucoma and thought to essentially contribute to aqueous humour production and intraocular hypertension [4]. Apart from its potential clinical application, 6A10 may also facilitate investigations into the biology of CA XII and contribute to a better understanding of its regulation, expression profile and its role in physiology and pathology.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Abbreviations

- CAs

Carbonic anhydrases

References

- 1.Warburg O. On respiratory impairment in cancer cells. Science. 1956;124:269–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stubbs M, McSheehy PM, Griffiths JR, Bashford CL. Causes and consequences of tumour acidity and implications for treatment. Mol Med Today. 2000;6:15–19. doi: 10.1016/S1357-4310(99)01615-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oksala N, Levula M, Pelto-Huikko M, Kytomaki L, Soini JT, Salenius J, Kahonen M, Karhunen PJ, Laaksonen R, Parkkila S, Lehtimaki T. Carbonic anhydrases II and XII are up-regulated in osteoclast-like cells in advanced human atherosclerotic plaques-Tampere Vascular Study. Ann Med. 2010;42:360–370. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2010.486408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liao SY, Ivanov S, Ivanova A, Ghosh S, Cote MA, Keefe K, Coca-Prados M, Stanbridge EJ, Lerman MI. Expression of cell surface transmembrane carbonic anhydrase genes CA9 and CA12 in the human eye: overexpression of CA12 (CAXII) in glaucoma. J Med Genet. 2003;40:257–261. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.4.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Supuran CT. Carbonic anhydrases—an overview. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:603–614. doi: 10.2174/138161208783877884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alterio V, Hilvo M, Di Fiore A, Supuran CT, Pan P, Parkkila S, Scaloni A, Pastorek J, Pastorekova S, Pedone C, Scozzafava A, Monti SM, De Simone G. Crystal structure of the catalytic domain of the tumor-associated human carbonic anhydrase IX. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:16233–16238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908301106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whittington DA, Waheed A, Ulmasov B, Shah GN, Grubb JH, Sly WS, Christianson DW. Crystal structure of the dimeric extracellular domain of human carbonic anhydrase XII, a bitopic membrane protein overexpressed in certain cancer tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9545–9550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161301298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wykoff CC, Beasley N, Watson PH, Campo L, Chia SK, English R, Pastorek J, Sly WS, Ratcliffe P, Harris AL. Expression of the hypoxia-inducible and tumor-associated carbonic anhydrases in ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:1011–1019. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64048-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsieh MJ, Chen KS, Chiou HL, Hsieh YS. Carbonic anhydrase XII promotes invasion and migration ability of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells through the p38 MAPK signaling pathway. Eur J Cell Biol. 2010;89:598–606. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiche J, Ilc K, Laferriere J, Trottier E, Dayan F, Mazure NM, Brahimi-Horn MC, Pouyssegur J. Hypoxia-inducible carbonic anhydrase IX and XII promote tumor cell growth by counteracting acidosis through the regulation of the intracellular pH. Cancer Res. 2009;69:358–368. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parkkila S, Rajaniemi H, Parkkila AK, Kivela J, Waheed A, Pastorekova S, Pastorek J, Sly WS. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitor suppresses invasion of renal cancer cells in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2220–2224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040554897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Svastova E, Zilka N, Zat’ovicova M, Gibadulinova A, Ciampor F, Pastorek J, Pastorekova S. Carbonic anhydrase IX reduces E-cadherin-mediated adhesion of MDCK cells via interaction with beta-catenin. Exp Cell Res. 2003;290:332–345. doi: 10.1016/S0014-4827(03)00351-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tureci O, Sahin U, Vollmar E, Siemer S, Gottert E, Seitz G, Parkkila AK, Shah GN, Grubb JH, Pfreundschuh M, Sly WS. Human carbonic anhydrase XII: cDNA cloning, expression, and chromosomal localization of a carbonic anhydrase gene that is overexpressed in some renal cell cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7608–7613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karhumaa P, Parkkila S, Tureci O, Waheed A, Grubb JH, Shah G, Parkkila A, Kaunisto K, Tapanainen J, Sly WS, Rajaniemi H. Identification of carbonic anhydrase XII as the membrane isozyme expressed in the normal human endometrial epithelium. Mol Hum Reprod. 2000;6:68–74. doi: 10.1093/molehr/6.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kivela A, Parkkila S, Saarnio J, Karttunen TJ, Kivela J, Parkkila AK, Waheed A, Sly WS, Grubb JH, Shah G, Tureci O, Rajaniemi H. Expression of a novel transmembrane carbonic anhydrase isozyme XII in normal human gut and colorectal tumors. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:577–584. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64762-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barnett DH, Sheng S, Charn TH, Waheed A, Sly WS, Lin CY, Liu ET, Katzenellenbogen BS. Estrogen receptor regulation of carbonic anhydrase XII through a distal enhancer in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3505–3515. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hynninen P, Vaskivuo L, Saarnio J, Haapasalo H, Kivela J, Pastorekova S, Pastorek J, Waheed A, Sly WS, Puistola U, Parkkila S. Expression of transmembrane carbonic anhydrases IX and XII in ovarian tumours. Histopathology. 2006;49:594–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ilie MI, Hofman V, Ortholan C, Ammadi RE, Bonnetaud C, Havet K, Venissac N, Mouroux J, Mazure NM, Pouyssegur J, Hofman P. Overexpression of carbonic anhydrase XII in tissues from resectable non-small cell lung cancers is a biomarker of good prognosis. Int J Cancer. 2010;128:1614–1623. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ivanov S, Liao SY, Ivanova A, Danilkovitch-Miagkova A, Tarasova N, Weirich G, Merrill MJ, Proescholdt MA, Oldfield EH, Lee J, Zavada J, Waheed A, Sly W, Lerman MI, Stanbridge EJ. Expression of hypoxia-inducible cell-surface transmembrane carbonic anhydrases in human cancer. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:905–919. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64038-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leppilampi M, Saarnio J, Karttunen TJ, Kivela J, Pastorekova S, Pastorek J, Waheed A, Sly WS, Parkkila S. Carbonic anhydrase isozymes IX and XII in gastric tumors. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:1398–1403. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i7.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parkkila S, Parkkila AK, Saarnio J, Kivela J, Karttunen TJ, Kaunisto K, Waheed A, Sly WS, Tureci O, Virtanen I, Rajaniemi H. Expression of the membrane-associated carbonic anhydrase isozyme XII in the human kidney and renal tumors. J Histochem Cytochem. 2000;48:1601–1608. doi: 10.1177/002215540004801203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Proescholdt MA, Mayer C, Kubitza M, Schubert T, Liao SY, Stanbridge EJ, Ivanov S, Oldfield EH, Brawanski A, Merrill MJ. Expression of hypoxia-inducible carbonic anhydrases in brain tumors. Neuro Oncology. 2005;7:465–475. doi: 10.1215/S1152851705000025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ulmasov B, Waheed A, Shah GN, Grubb JH, Sly WS, Tu C, Silverman DN. Purification and kinetic analysis of recombinant CA XII, a membrane carbonic anhydrase overexpressed in certain cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:14212–14217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ashida S, Nishimori I, Tanimura M, Onishi S, Shuin T. Effects of von Hippel-Lindau gene mutation and methylation status on expression of transmembrane carbonic anhydrases in renal cell carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2002;128:561–568. doi: 10.1007/s00432-002-0374-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Creighton CJ, Cordero KE, Larios JM, Miller RS, Johnson MD, Chinnaiyan AM, Lippman ME, Rae JM. Genes regulated by estrogen in breast tumor cells in vitro are similarly regulated in vivo in tumor xenografts and human breast tumors. Genome Biol. 2006;7:R28. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-4-r28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frasor J, Stossi F, Danes JM, Komm B, Lyttle CR, Katzenellenbogen BS. Selective estrogen receptor modulators: discrimination of agonistic versus antagonistic activities by gene expression profiling in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1522–1533. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ibrahim SF, Diercks AH, Petersen TW, van den Engh G. Kinetic analyses as a critical parameter in defining the side population (SP) phenotype. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:1921–1926. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Innocenti A, Vullo D, Pastorek J, Scozzafava A, Pastorekova S, Nishimori I, Supuran CT. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Inhibition of transmembrane isozymes XII (cancer-associated) and XIV with anions. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:1532–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.12.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vullo D, Innocenti A, Nishimori I, Pastorek J, Scozzafava A, Pastorekova S, Supuran CT. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Inhibition of the transmembrane isozyme XII with sulfonamides-a new target for the design of antitumor and antiglaucoma drugs? Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15:963–969. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.12.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khalifah RG. The carbon dioxide hydration activity of carbonic anhydrase. I. Stop-flow kinetic studies on the native human isoenzymes B and C. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:2561–2573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Supuran CT. Carbonic anhydrases: novel therapeutic applications for inhibitors and activators. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:168–181. doi: 10.1038/nrd2467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Supuran CT, Scozzafava A, Casini A. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Med Res Rev. 2003;23:146–189. doi: 10.1002/med.10025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pastorekova S, Zatovicova M, Pastorek J. Cancer-associated carbonic anhydrases and their inhibition. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:685–698. doi: 10.2174/138161208783877893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jensen RL. Brain tumor hypoxia: tumorigenesis, angiogenesis, imaging, pseudoprogression, and as a therapeutic target. J Neurooncol. 2009;92:317–335. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-9827-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Supuran CT, Scozzafava A. Carbonic anhydrases as targets for medicinal chemistry. Bioorg Med Chem. 2007;15:4336–4350. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swietach P, Wigfield S, Supuran CT, Harris AL, Vaughan-Jones RD. Cancer-associated, hypoxia-inducible carbonic anhydrase IX facilitates CO2 diffusion. BJU Int. 2008;101(Suppl 4):22–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swietach P, Wigfield S, Cobden P, Supuran CT, Harris AL, Vaughan-Jones RD. Tumor-associated carbonic anhydrase 9 spatially coordinates intracellular pH in three-dimensional multicellular growths. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:20473–20483. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801330200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deonarain MP, Kousparou CA, Epenetos AA. Antibodies targeting cancer stem cells: a new paradigm in immunotherapy? MAbs. 2009;1:12–25. doi: 10.4161/mabs.1.1.7347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu C, Alman BA. Side population cells in human cancers. Cancer Lett. 2008;268:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sung JM, Cho HJ, Yi H, Lee CH, Kim HS, Kim DK, Abd El-Aty AM, Kim JS, Landowski CP, Hediger MA, Shin HC. Characterization of a stem cell population in lung cancer A549 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;371:163–167. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vaupel P, Mayer A. Hypoxia in cancer: significance and impact on clinical outcome. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26:225–239. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Isa AY, Ward TH, West CM, Slevin NJ, Homer JJ. Hypoxia in head and neck cancer. Br J Radiol. 2006;79:791–798. doi: 10.1259/bjr/17904358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hui EP, Chan AT, Pezzella F, Turley H, To KF, Poon TC, Zee B, Mo F, Teo PM, Huang DP, Gatter KC, Johnson PJ, Harris AL. Coexpression of hypoxia-inducible factors 1alpha and 2alpha, carbonic anhydrase IX, and vascular endothelial growth factor in nasopharyngeal carcinoma and relationship to survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:2595–2604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kappler M, Taubert H, Holzhausen HJ, Reddemann R, Rot S, Becker A, Kuhnt T, Dellas K, Dunst J, Vordermark D, Hansgen G, Bache M. Immunohistochemical detection of HIF-1alpha and CAIX in advanced head-and-neck cancer. Prognostic role and correlation with tumor markers and tumor oxygenation parameters. Strahlenther Onkol. 2008;184:393–399. doi: 10.1007/s00066-008-1813-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beasley NJ, Wykoff CC, Watson PH, Leek R, Turley H, Gatter K, Pastorek J, Cox GJ, Ratcliffe P, Harris AL. Carbonic anhydrase IX, an endogenous hypoxia marker, expression in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and its relationship to hypoxia, necrosis, and microvessel density. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5262–5267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haapasalo J, Hilvo M, Nordfors K, Haapasalo H, Parkkila S, Hyrskyluoto A, Rantala I, Waheed A, Sly WS, Pastorekova S, Pastorek J, Parkkila AK. Identification of an alternatively spliced isoform of carbonic anhydrase XII in diffusely infiltrating astrocytic gliomas. Neuro Oncology. 2008;10:131–138. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2007-065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fang JS, Gillies RD, Gatenby RA. Adaptation to hypoxia and acidosis in carcinogenesis and tumor progression. Semin Cancer Biol. 2008;18:330–337. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ke Q, Costa M. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:1469–1480. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.027029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Silva AS, Yunes JA, Gillies RJ, Gatenby RA. The potential role of systemic buffers in reducing intratumoral extracellular pH and acid-mediated invasion. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2677–2684. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oosterwijk E, Ruiter DJ, Hoedemaeker PJ, Pauwels EK, Jonas U, Zwartendijk J, Warnaar SO. Monoclonal antibody G 250 recognizes a determinant present in renal-cell carcinoma and absent from normal kidney. Int J Cancer. 1986;38:489–494. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910380406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.