Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most aggressive carcinomas. Limited therapeutic options, mainly due to a fragmented genetic understanding of HCC, and major HCC resistance to conventional chemotherapy are the key reasons for a poor prognosis. Thus, new effective treatments are urgent and gene therapy may be a novel option. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) is a highly studied member of the STAT family. Inhibition of Stat3 signaling has been found to suppress tumor growth and improve survival, providing a molecular target for cancer therapy. Furthermore, HCC is a hypervascular tumor and angiogenesis plays a crucial role in tumor growth and metastasis. Thus, anti-angiogenic therapy, combined with inhibition of Stat3, may be an effective approach to combat HCC. We tested the effect that the combination therapy consisting of endostatin (a powerful angiogenesis inhibitor) and Stat3-specific small interfering RNA, using a DNA vector delivered by attenuated S. typhimurium, on an orthotopic HCC model in C57BL/6 mice. Although antitumor effects were observed with either single therapeutic treatment, the combination therapy provided superior antitumor effects. Correlated with this finding, the combination treatment resulted in significant alteration of Stat3 and endostatin levels and that of the downstream gene VEGF, decreased cell proliferation, induced cell apoptosis and inhibited angiogenesis. Importantly, combined treatment also elicited immune system regulation of various immune cells and cytokines. This study has provided a novel cancer gene therapeutic approach.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00262-012-1256-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Combined gene therapy, Hepatocellular carcinoma, RNA interference, Anti-angiogenesis, Immune response

Introduction

HCC, which accounts for 85–90 % of all primary liver cancers, ranks as the fifth most common primary cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related death globally [1, 2], with 748,000 estimated new cases annually and almost as many deaths [3]. Curative treatment options chiefly comprise surgical resection or liver transplantation [4]. In spite of many scientific advances, prognosis for HCC remains poor due to the absence of early disease symptoms, rapid tumor progression and invasion-related spreading during early tumor stages [5]. As a result of these factors, only 10–20 % of patients are considered eligible for surgical treatment [6]. Development of novel therapeutic tactics targeting HCC, without remarkable toxicity, is of high priority.

Accumulating evidence has shown that cancer gene therapy offers numerous unique treatments [7]. Stat3 is an important member of the STAT family. Normally under strict regulation, Stat3 is momentarily activated in response to multiple cytokines and growth factors [8]. However, persistently activated Stat3 is oncogenic and prevalent in diverse tumor types, including multiple myeloma, leukemia, melanoma, breast, lung, prostate and liver cancers, and other solid and hematologic tumors [9]. Aberrantly activated Stat3 contributes to carcinogenesis by promoting tumor cell proliferation and angiogenesis together with suppressing apoptosis and host tumor immunity [10]. A growing body of evidence has shown that specific inhibition of Stat3 signaling suppresses tumor growth and improves survival [11–14], supporting Stat3 as a novel target for therapeutic intervention in cancer gene therapy.

On the other hand, HCC represents a distinctively hypervascular tumor [15], and antiangiogenic therapy has become a promising approach. Endostatin, a 20-KDa C-terminal fragment of collagen XVIII, was isolated and purified from murine hemangioendothelioma. It has been shown to be one of the most powerful angiogenesis inhibitors by specific inhibition of endothelial proliferation [16]. Several studies have exhibited the antiangiogenic properties of endostatin in a wide variety of established tumor models of mouse [17], rat [18] and human [19] origins accompanied by low toxicity [20, 21] and lacking acquired drug resistance [22].

Choosing an efficient gene delivery system that should selectively target tumors and deliver the anticancer therapeutic agents into tumors while reducing damage to normal tissue has been a major concern. S. typhimurium, a facultative anaerobe, offers particular promise as an anticancer vector over other vectors currently used. They can preferentially amplify and reside within solid tumors (>1,000 fold greater in tumors than in normal tissues), while minimizing toxicity to normal tissues [23, 24]. More recently, these bacteria have been engineered to express numerous genes, including interleukin-2 [25], interleukin-12 [26] and MDR1 siRNA [27], etc. Additionally, previous studies demonstrated that Stat3-specific siRNA carried by attenuated S. typhimurium showed protection against prostate cancer in our laboratory [13].

In view of the complicated biologic heterogeneity of tumors, a novel combination approach would be expected to enhance the effect of either single therapeutic approach. Here, for the first time, we have exploited the use of attenuated S. typhimurium (a phoP/phoQ null mutant) to deliver the eukaryotic co-expression plasmid vector encoding both Stat3-specific siRNA and endostatin, as combined tumor-targeted anticancer agents to examine their antitumor effects in an orthotopic hepatoma mouse model.

Materials and methods

Cell lines, animals, plasmids and bacterial strains

The mouse hepatoma cell line H22 was purchased from Shanghai Institute of Cell Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Male C57BL/6 mice, weighing approximate 20 g, were obtained from Animal Center of Norman Bethune Medical College, Jilin University (Changchun). All animals were maintained in pathogen-free conditions and in accordance with protocols approved by the National Institute of Health Guide for care. The eukaryotic expression vector pcDNA3.1-Si-Stat3 (pSi-Stat3) encoding shRNA specific to Stat3, pSi-Scramble (scramble shRNA sequence as a negative control), pcDNA3.1-ssEndostatin (pEndostatin) and coexpression plasmid pcDNA3.1-ssEndostatin-Si-Stat3 (pEndo-Si-Stat3) co-expressed both ShRNA-Stat3 and the murine secretory endostatin protein were stored in our laboratory [12, 13]. The attenuated S. typhimurium phoP/phoQ null strain LH430 was kindly provided by Dr. E. L. Hohmann [28]. Each plasmid was electroporated into attenuated S. typhimurium before use to generate the bacterial strains SL/pSi-Scramble, SL/pEndostatin, SL/pSi-Stat3 and SL/pEndo-Si-Stat3.

Establishment of orthotopically implanted HCC model

Briefly, 0.2 ml H22 cells (1 × 107/mouse) were injected subcutaneously into the right anterior flank of mice. After 2 weeks, when the tumor reached to approximately 1 cm in diameter, it was isolated and cut into small pieces of equal volume (1 mm3). C57BL6 mice in this study were anesthetized (Pentobarbitone 70 mg/Kg bodyweight), and laparotomy was performed. After preparation of the liver, the right liver lobes were punctured to form about a 3-mm-long sinus tract and the fragment of tumor tissue was inserted into the sinus tract. Thus, the orthotopic H22 hepatoma model was established.

Treatment and evaluation of possible side effects

At day 10, mice were randomly divided into five groups (n = 10 each group). By the intraperitoneal (i.p.) route, the Mock group received 100 μl PBS and experimental groups were administered different recombinant-attenuated Salmonella (1 × 106 CFU in 100 μl PBS per mouse). After treatment, the mice were examined for body weight and motor capacity daily. At selected time points after treatment, mice were killed, and the tumors, livers, spleens, hearts, lungs, and kidneys were excised, weighed and homogenized in 2 ml of ice-cold, sterile PBS. The bacteria were quantified by plating dilutions of the homogenates onto LB agar plates containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml), incubating at 37 °C overnight, and counting bacterial colonies.

Flow cytometry analysis

At various time points after treatment, tumor-bearing mice were killed. Spleens were isolated and homogenized. The splenic cell suspension was subjected to red blood cell lysis using ACK buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and washed; the cells were counted. After filtering through a cell filter membrane, the splenocytes were stained with appropriate fluorescence-labeled conjugated antibodies to CD3-APC, CD4-PE, CD8-FITC, NK1.1-PE (eBioscience) or their respective isotype controls and incubated at 4 °C for 30 min. Three-color staining was performed for detecting CD3+, CD4+, CD8+ T lymphocytes and Treg cells. CD25 and intracellular Foxp3 (FJK-16 s) staining were detected using the mouse Treg cell staining kit (eBioscience), according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Western blot assay

Western blot (WB) analysis to determine the expression of various proteins’ dynamic change in every group was carried out as described previously [12, 29].

Immunohistochemistry and TUNEL assay

Tumors treated with or without different recombinant Salmonella strains were excised from mice for H&E staining. Immunohistochemical analyses were carried out as described previously [12, 29]. Antibodies against CD4, CD8, CD34 and PCNA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA) were used. The DeadEnd™ Fluorometric TUNEL System kit (Promega, Madision, WI, USA) was used for TUNEL assay.

Semi-quantitation RT-PCR and real-time quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from the tumor tissues using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. First-strand cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription of 2 μg total RNA using a Takara RNA PCR Kit (TaKaRa, Japan). Primers used in semi-quantitation RT-PCR were as follows: β-actin sense, 5′-ATATCGCTGCGCTGGTCGTC-3′ and antisense, 5′-AGGATGGCGTGAGGGAGAGC-3′; VEGF sense, 5′-AGTCCCATGAAGTGATCAAGTTCA-3′ and antisense, 5′-ATCCGCATGATCTGCATGG-3′. Cycling parameters were as follows: denaturation (94 °C, 30 s), annealing (β-actin, 55 °C, 30 s; VEGF, 57 °C, 30 s) and extension (72 °C, 1 min) with 25 and 30 cycles, respectively. The PCR products were electrophoresed in 1 % agarose gel containing ethidium bromide and visualized by a GIS Gelatum imaging system (Tanon, Shanghai, China). Absolute gene transcription was compared to that of β-actin. Each PCR was carried out with 0.5 μl of the cDNA and 0.2 μmol/l of each primer with SYBR Green QPCR Master Mix (Agilent Technologies, USA). The following primers for QPCR were used: β-actin sense: 5′-CTGAGAGGGAAATCGTGCGT-3′ and antisense: 5′-AACCGCTCGTTGCCAATAGT-3′; Stat3 sense: 5′-ACCAGCAATATAGCCGATTCC-3′ and antisense: 5′-CCATTGGCTTCTCAAGATACC-3′. Each reaction (25-μl samples) was carried out under the following cycling conditions: initialization for 10 min at 95 °C and then 40 cycles of amplification, with 15 s at 95 °C for denaturation, and 1 min at 60 °C for annealing and elongation. A standard curve was plotted for each primer probe established by using a serial dilution of pooled cDNA from tissues. All standards and samples were conducted in triplicate.

Lymphocyte proliferation measurement

Mouse splenic lymphocytes (5 × 105cells/100 μl) were plated and incubated in a 96-well plate in the absence or presence of ConA (5 mg/ml) in triplicate for 48 h. 20 μl MTT [5 mg/ml, 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide, Amresco Invitrogen Corp, Carlsbad, CA, USA] was added, and the cells were incubated for an additional 4 h. Subsequently, formanzan crystals were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO, Pierce Biotechnology, USA), and 150 μl of this preparation was added/well. When completely absorbed, the optical density (OD) was measured at 490 nm using a microplate reader (Microplate Reader Model 550, Bio-Rad, USA). The stimulation index (SI) was calculated according to the following the formula: SI = ODConA-stimulated lymphocyte proliferation/ODspontaneous lymphocyte proliferation without Con A.

NK cell cytotoxicity assay

NK cells from mouse spleens were prepared, as described above, and used as effector cells. Mouse lymphoma YAC-1 cells, sensitive to NK cells, were used as target cells. Briefly, 100 μl of YAC-1 (1 × 104 cells) was added to each well of a 96-well plate, and 100 μl of each concentration of effector cells was added to form mixtures to obtain an effector/target (E/T) ratio of 100:1, 50:1, 25:1 or 12.5:1. After 16-h incubation, NK cytotoxicity was assessed using the MTT assay as described above. The cytotoxic activity was calculated following the formula: % NK cytotoxicity = [1 – (ODE + T-ODE)/ODT × 100 %]. (E + T = mixtures of effector cells and target cells, E = effector cells, T = target cells).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

The tumor supernatant level of endostatin was detected using Mouse Endostatin ELISA kit (R&D Systems). The blood was collected in EP (eppendorf) tubes, placed at 37 °C for 15 min and 4 °C for 1 h. The serum samples were centrifuged at 6,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The level of IFN-γ, TGF-β1 and TNF-α was determined using the Mouse IFN-γ ELISA kit, Mouse TGF-β1 ELISA kit and Mouse TNF-α ELISA kit (ExCell Biology, Shanghai, China), according to the manufacturer’s directions, respectively.

Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as mean values ± standard deviation (SD). The significant differences among groups were determined by one-way ANOVA. All experiments were repeated three times. All statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS 13 statistical software version [Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS statistics, IBM, USA)].

Results

Recombinant-attenuated S. typhimurium possesses tumor-targeting ability and lack of apparent toxicity

In an orthotopic hepatocarcinoma model, i.p. inoculation of 1 × 106 CFUs of phoP/phoQ-deleted, attenuated Salmonella typhimurium resulted in the preferential bacterial colonization of H22-bearing tumors, as compared with other healthy tissues examined (i.e., heart, spleen, lung, kidney and liver, data not shown). Bacterial colonization of tumors at 48 h. averaged ~1,000-fold greater CFUs/gm tissue than in healthy tissues (Supplementary Table 1), similar to the numbers obtained in previous studies [23, 27], and would remain the concentration at least 2 weeks (data not shown).

During 28 days of post-treatment follow-up, the treatment groups of mice did not show observed sign of potential adverse effects such as body weight loss, less activity, uneven fur or less energy. Further, histopathologic studies showed no obvious lesions in the heart, spleen, lung, kidney and liver (data not shown).

Effect of combined treatment with SL/pEndo-Si-Stat3 on tumor growth

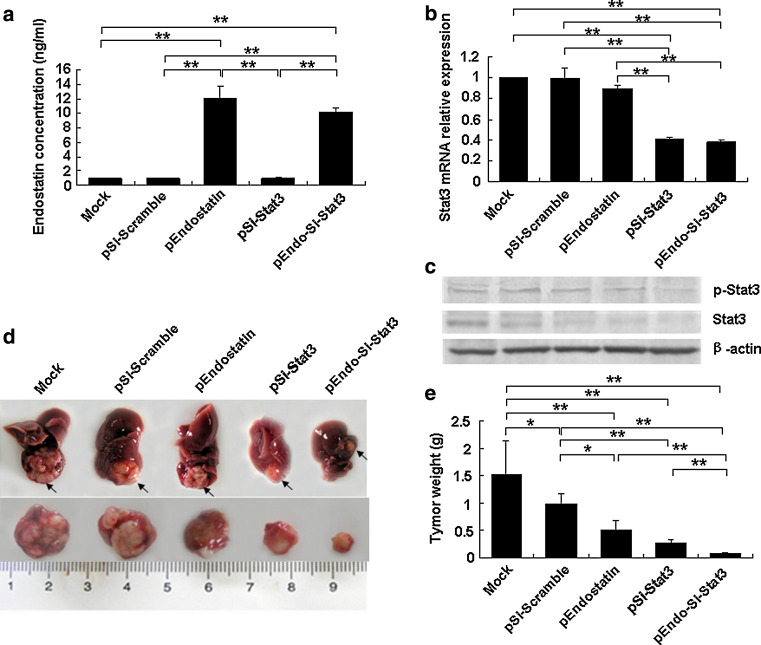

We assessed the expression of Stat3 and the secreted endostatin level to identify the transfection efficiency. As shown in Fig. 1a, tumors isolated from mice treated with SL/pEndostatin alone and the combination SL/pEndo-Si-Stat3 showed strong expression of endostatin compared with other treatment groups. In addition, since the plasmid contained Si-Stat3 interfere with the massive expression of Stat3 mRNA, there was a marked decrease in the mRNA and protein level of Stat3 following treatment with SL/pSi-Stat3 alone or SL/pEndo-Si-Stat3, but scarcely decreased in other treatment groups (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Analyses of endostatin and Stat3 levels and tumor growth in vivo. At the day 10 after the tumors implanted, mice were injected i.p. with PBS and different recombinant plasmids. After 3-week treatment, mice were then isolated and analyzed. a Endostatin level by ELISA. b Real-time quantitative PCR was performed and relative Stat3, mRNA expression was calculated in each group. c Stat3 and p-Stat3 protein expression was determined using Western blot. d Size of tumors. e Average tumor weight. Data are presented as a mean ± SD, from 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

The average tumor weight after 3-week treatment with the combination therapy was lower by 84 and 70 % compared with that of SL/pEndostatin or SL/pSi-Stat3 single treatment groups, respectively (P < 0.01), and it was significantly decreased by 92 and 95 % compared with that in the SL/pSi-Scramble or Mock groups, respectively (P < 0.001). Furthermore, the average tumor weight of the SL/pSi-Scramble group was found to be less than that of Mock group, decreasing by 36 % (P < 0.05, Fig. 1c, d; Table 1), showing that attenuated Salmonella alone has antitumor effects. Most importantly, among the animals that received a single dose of Salmonella-delivered pEndo-Si-Stat3, two of the ten mice became tumor free within 3 weeks (data not shown).

Table 1.

Body weight and tumor weight after treatment (n = 5, ± s)

| Group | Mean body weight (g) | Mean tumor weight (g) |

|---|---|---|

| Mock | 28.33 ± 2.31 | 1.52 ± 0.62 |

| SL/pSi-Scramble | 27.53 ± 3.32 | 0.98 ± 0.19 |

| SL/pEndostatin | 25.76 ± 1.38 | 0.50 ± 0.17*,△ |

| SL/pSi-Stat3 | 25.89 ± 4.30 | 0.27 ± 0.06*,△△ |

| SL/pEndo-Si-Stat3 | 24.88 ± 3.76 | 0.08 ± 0.02*,△△,#,$ |

* P < 0.01 versus Mock, △ P < 0.05 versus SL/pSi-Scramble, △△ P < 0.01 versus SL/pSi-Scramble, # P < 0.01 versus SL/pEndostatin, $ P < 0.01 versus SL/pSi-Stat3

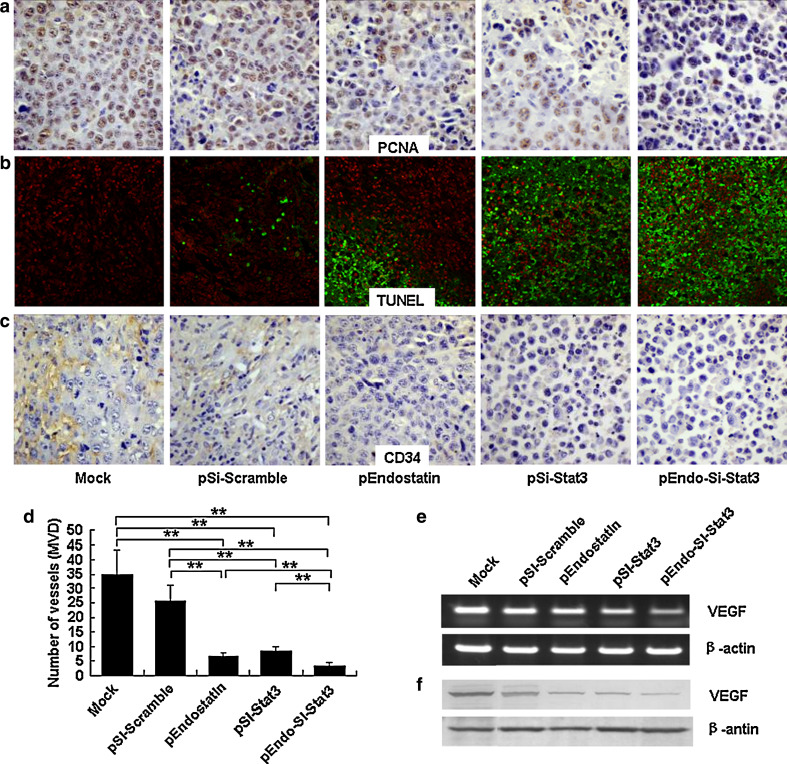

Treatment effects on proliferation and apoptosis

Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) is a nuclear protein that is expressed in G1-M phases of the cell cycle. As shown in Fig. 2a, PCNA immunostaining was significantly elevated in the Mock group, evidence of the high proliferation of tumor cells (P < 0.01, Supplementary Table 2). In contrast, PCNA expression was observed to decrease in all treatment groups, especially in the SL/pEndo-Si-Stat3 group. Further, tumor sections from mice treated with SL/pEndo, SL/pSi-Stat3 or SL/pEndo-Si-Stat3 showed a pronounced increase in apoptosis compared with the Mock and SL/pSi-Scramble groups, as observed by TUNEL assay. Though less dramatic, SL/pEndostatin treatment also induced an increase in apoptotic cells relative to the Mock and SL/pSi-Scramble groups (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Analysis of cell proliferation, apoptosis and angiogenesis after treatment. The tumors were harvested after 3-week treatment and analyzed. a The expression of PCNA using immunohistochemistry (×400). b TUNEL assay (×100). c Immunohistochemistry analysis of the expression of CD34 in tumor tissue (×400). d Blood vessels stained with anti-CD34 were quantified by MVD analysis. e, f mRNA and protein expression levels of VEGF by Western blot (e), RT-PCR (f). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

Anti-angiogenic effects of various antitumor treatments

To evaluate the antiangiogenic effects of therapy, we examined tumor microvasculature. Tumor sections were immunohistochemically stained with an endothelial-specific antibody against CD34 (Fig. 2c). Microvessel density (MVD) was quantitatively assessed by the “hot spot” method [30] (Fig. 2d). SL/pEndostatin or SL/pSi-Stat3 treated tumors showed decreased blood vessel density compared with the Mock and SL/pSi-Scramble groups (P < 0.01). However, the largest reduction in tumor microvasculature occurred in mice treated with the combination therapy (P < 0.01, Fig. 2c, d).

One mechanism of endostatin-induced anti-angiogenesis probably occurs through the inhibition of the VEGF signal transducer pathway [31]. In stark contrast, Stat3 activation promotes angiogenesis partly by increasing VEGF expression [9]. To examine VEGF expression, we utilized Western blot analysis and RT-PCR, respectively. Though all three treatment groups resulted in a significant decrease in VEGF protein and mRNA levels (P < 0.01), the combined therapy group exhibited the most dramatic reduction (P < 0.01, Fig. 2e, f).

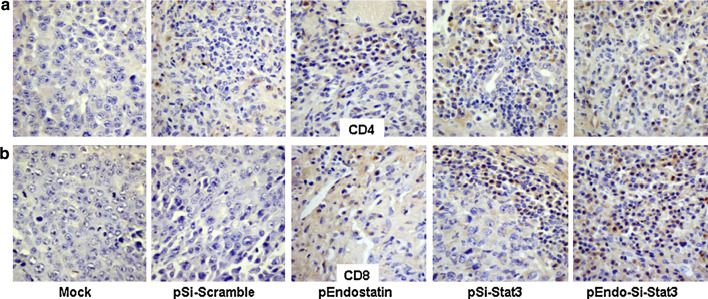

Tumor-infiltrating T-lymphocyte detection

To further analyze intra-tumoral lymphocyte infiltrates, we examined CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes by immunohistochemistry. Seven days after treatment, tumor specimens were obtained from tumor-bearing mice and then were subjected to analysis. T lymphocytes are smaller than tumor cells and the surface markers CD4+ and CD8+ localized on cellular membrane. Compared to the Mock and pSi-Scramble groups, the treatment groups resulted in increased number of CD4+ (Fig. 3a) and CD8+ (Fig. 3b) T lymphocytes in the tumor tissues, respectively. Combination treatment caused the most marked observable changes of CD8+ T lymphocytes.

Fig. 3.

Immunohistochemical analyses of immune cell recruitment in tumor tissue. After 2-week treatment with Salmonella-delivered therapies, the tumors were isolated and then processed in 5-μm sections. The cross-sections of the tumors were stained with antibodies directed against CD4 (a) and CD8 (b) (×400)

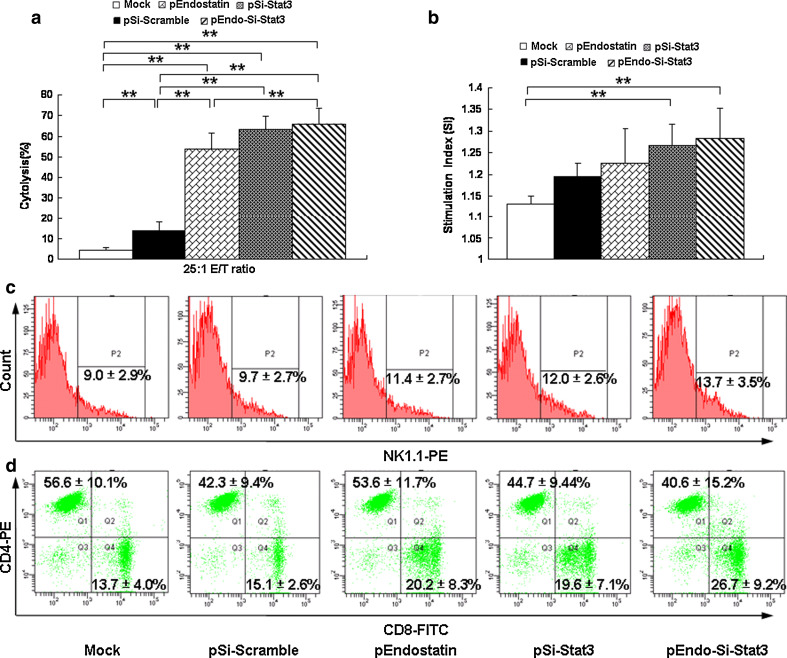

Various immune cells response in spleen

As we all known, spleen is the center of cell immunity and plays a key role in the antitumor immunity. We next detected whether the tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes increasing due to immune cells changes in spleen. To determine the impact on NK cell function, we measured antitumor activity of NK cells via a cytotoxicity assay. In this assay, the NK cell cytotoxic activity of SL/pEndo-Si-Stat3 group at an E/T ratio 25:1 was 65.9 % (Fig. 4a), which was significantly higher than the low cytotoxicity levels of the Mock (4.4 %) and pSi-Scramble (13.8 %) groups, and also slightly higher than the levels of the SL/pEndostatin group (53.6 %) (P < 0.05). Note that, although exhibiting a slight apparent increase after treatment, the proportions of NK1.1 splenic cells were not significantly different among all groups (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4.

Salmonella-vectored antitumor therapies activate NK cell and T-lymphocyte function. a NK cells cytotoxicity. Seven days after inoculation of recombinant bacteria, the mice spleens were isolated and tested for their cytotoxic ability as effector cells. b Effect of Salmonella-Si-Stat3 on Con A-induced splenic lymphocyte proliferation. MTT assay was performed on day 14 after therapy to evaluate the T-cell function. c Expression of NK cells in spleen was analyzed by flow cytometry on day 7. d Responses of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes in spleen, as analyzed by flow cytometry on day 14. Numbers indicate the percentages of cytokine-positive cells in the gates within the total population. Data are presented as a mean ± SD, from 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

The MTT assay was performed to evaluate splenic lymphocyte proliferation abilities of the various treatment groups. Both the SL/pSi-Stat3 and SL/pEndo-Si-Stat3 groups were observed to significantly increase lymphocyte proliferation at a concentration of 5 μg/ml Con A, compared to the Mock group (P < 0.01, Fig. 4b). Moreover, the CD3+/CD4+ and CD3+/CD8+ splenic T lymphocytes were further analyzed using three-color flow cytometry. Interestingly, the percentage of CD8+ T lymphocytes increased, about two times higher than that of the Mock group, and the percentage of CD4+ T lymphocytes decreased in the SL/pEndo-Si-Stat3-treated mice (Fig. 4d). In fact, treatment with Salmonella-delivered therapies dramatically reduced the splenic CD4+/CD8+ ratio.

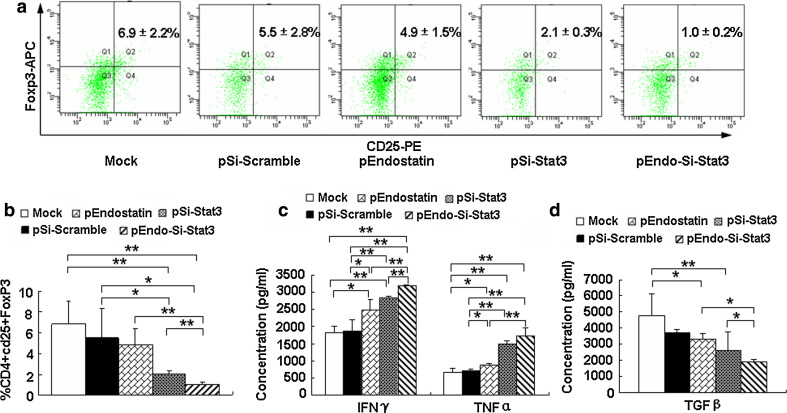

Antitumor therapy effects on the population of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) in the spleen

Previous studies have indicated that CD4+CD25+ Treg cells characterized by the expression of Foxp3 play a significant role in suppressing antitumor immunity [32]. CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells have been shown to suppress immune responses via direct interaction with other immune cells or through immune suppressive cytokines and led to tumor immune tolerance [33–36]. Here, we tested whether treatment with SL/p-Endo-Si-Stat3 could inhibit the induction of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells in the spleen. We found that the CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ proportions in the SL/p-Endo-Si-Stat3 treatment group were 1.0 ± 0.2 %, which was considerably reduced compared with the monotherapy treatments (2.1 ± 0.3 and 4.9 ± 1.5 %, respectively), pSi-Scramble (5.5 ± 2.8 %) or Mock (6.9 ± 2.2 %) groups (Fig. 5a, b). Changes in Treg cells might be the result of treatment-induced Stat3 deficiency in T lymphocytes or indirect effects influenced by Stat3 signaling in other immune cells.

Fig. 5.

Effect of combined treatment on Treg cells and cytokines level. Two weeks after treatment, the mice spleens were isolated to analyze the Treg cells expression and the serum was collected to detect the cytokines. a The intracellular level of Foxp3 was evaluated in splenic CD4+ T lymphocytes by flow cytometry. b The percentage of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells was determined. c The serum level of IFNγ and TNFα. d The serum level of TGF-β1. Data are presented as the mean ± SD, from 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

Combination treatment: effects on the level of proinflammatory and immunosuppressive factors

To further analyze the mechanisms by which the combination therapy induces NK activation, recruitment of T lymphocytes, and inhibits Treg cells, blood was evaluated for the level of several key proinflammatory and immunosuppressive cytokines. Interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor-a (TNF-a) have been shown to be capable of eliciting beneficial antitumor effects through their dual function as proinflammatory and anti-angiogenic factors in a variety of experimental tumor models [37]. In contrast, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) are potent immunosuppressive factors, which promote and sustain nonresponsiveness of the immune system to induction of Treg cell activation [38]. As shown in Fig. 5c, d, SL/pEndo-Si-Stat3 treatment significantly increased the levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α, about twofold higher than that of the Mock and the pSi-Scramble groups. Combined therapy also reduced the levels of TGF-β1, approximating a quarter of that in the Mock group (P < 0.01).

Discussion

In this report, we have employed several recombinant therapeutic plasmids, one of which co-expresses endostatin plus a small interference RNA targeting Stat3. A key requirement of gene therapy is an effective gene delivery system. Although viral vectors have been broadly applied in gene therapy, nonviral vectors offer important advantages (e.g., tumor-targeting ability). In the current studies, we have employed an attenuated S. typhimurium to target tumors and directly deliver the therapeutic plasmids. Utilizing an H22-bearing orthotopic tumor mouse model, we have demonstrated that Salmonella-delivered combination therapy (i.e., endostatin plus siRNA-Stat3) provides superior antitumor effects over either single therapeutic approach. At three weeks post-treatment, mean tumor weight in the Mock group reached 1.52 ± 0.62 g, whereas the combined treatment group had a reduced mean tumor weight of 0.08 ± 0.02 g. Importantly, two out of ten animals showed total tumor eradication following one therapeutic treatment. Moreover, the endostatin levels were increased following treatment with pEndostatin or pEndo-Si-Stat3, and the Stat3 levels were markedly reduced following treatment with pSi-Stat3 or pEndo-Si-Stat3, as expected. Further, the combined treatment stimulated apoptosis and inhibited angiogenesis in tumors, and exhibited maximal antitumor effects.

Additional studies were conducted to better understand the effects of these therapies on antitumor immune cell activation. As VEGF is known to be a downstream gene controlled by both Stat3 and endostatin, it is expected that suppression of Stat3 expression and increased endostatin in tumors would result in a substantial reduction of VEGF, an angiogenesis factor as well as a potent immunosuppressive factor. Besides VEGF up-regulation, overexpression of Stat3 is activated in various immune cells, including NK cells, CD8+ T lymphocytes, DC and so on, rendering these cells immunosuppressive or dysfunctional. Consequently, combination treatment would be expected to inhibit angiogenesis and recruit immune cells. In the context of the antitumor immune response, we observed that combination treatment promoted the obvious increase in tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T lymphocytes, the cytolytic function of NK cells, plus increased numbers and activity of splenic CD8+ T lymphocytes. Interestingly, we found a lower number of CD4+ T lymphocytes and a reduction in the ratio of CD4+/CD8+ T lymphocytes in the spleens in all treatment groups, with the most marked effect seen following combination treatment. A possible explanation for this phenomenon is that inhibition of Stat3 and overexpression of endostatin may affect T-lymphocyte subsets by promoting the expression and activity of CD8+ T lymphocytes, which are considered as major factors in antitumor immunity [39]. The increase in CD8+ T lymphocytes following single gene treatment with SL/pEndostatin indicated that somehow endostatin, as an angiogenesis inhibitor, may also affect CD8+ T lymphocytes and other immune cells indirectly or directly.

Based on the interdependence and interaction between various immune cells or immune cells and cytokines, we also detected the CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells and several cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-α and TGF-β1). After combined treatment, these factors were changed in different degree. With regard to DC, we detected the expression of splenic DC in spleens using flow cytometry, and statistical analysis revealed no significant difference in the percentage of MHCII+CD86+ and MHCII+CD80+ cells among each group (data not shown).

Altogether, our data showed that combination treatment resulted in marked tumor regression (and tumor eradication in two animals), associated with an enhanced antitumor immune response through overexpression of endostatin and inhibition of Stat3. The superior antitumor effects appear to stem from essential changes in several parameters, which appear not only on the changes of tumor cell and endothelial cell proliferation, apoptosis and angiogenesis, but also on the alteration in several immune cells (T cells, NK cells and Treg cells) and in the level of several cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-α and TGF-β1). Although single gene treatment with SL/pSi-Stat3 and SL/pEndostatin also resulted in a similar pattern of changes in observed antitumor responses, the magnitudes observed were obviously less than those of the combination treatment.

In summary, these studies demonstrate, in an orthotopic implant tumor model in mice, the enhanced value of combined antitumor gene therapies in the treatment of the aggressive HCC and verify safety and tumor-targeting ability of the attenuated Salmonella as a delivery system. Future studies must be aimed at studying the length of intrahost survival of the Salmonella vector, the potential use of multiple therapeutic doses, and long-term assessment of total tumor eradication and increased survival.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grands from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 30801354 and No. 30970791), Specialized Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education of China (No.200801831077) and Jilin Provincial Science & Technology Department (No. 20080154). We thank Professor Liying Wang and Professor Yongli Bao for helpful suggestions.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Huijie Jia and Yang Li authors contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Ling Zhang, Phone: +86-0431-85632348, FAX: +86-0431-85632348, Email: zhangling3@jlu.edu.cn.

De Qi Xu, Phone: +301-496-1894, FAX: +301-402-8701, Email: dqxujl@gmail.com.

References

- 1.El-Serag HB, Rudolph KL. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(7):2557–2576. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lau WY, Lai EC. The current role of radiofrequency ablation in the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2009;249(1):20–25. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818eec29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sotiropoulos GC, Molmenti EP, Losch C, Beckebaum S, Broelsch CE, Lang H. Meta-analysis of tumor recurrence after liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma based on 1,198 cases. Eur J Med Res. 2007;12(10):527–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song TJ, Ip EW, Fong Y. Hepatocellular carcinoma: current surgical management. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(5 Suppl 1):S248–S260. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang ZY, Ye SL, Liu YK, Qin LX, Sun HC, Ye QH, Wang L, Zhou J, Qiu SJ, Li Y, Ji XN, Liu H, Xia JL, Wu ZQ, Fan J, Ma ZC, Zhou XD, Lin ZY, Liu KD. A decade’s studies on metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2004;130(4):187–196. doi: 10.1007/s00432-003-0511-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cross D, Burmester JK. Gene therapy for cancer treatment: past, present and future. Clin Med Res. 2006;4(3):218–227. doi: 10.3121/cmr.4.3.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowman T, Garcia R, Turkson J, Jove R. STATs in oncogenesis. Oncogene. 2000;19(21):2474–2488. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu H, Jove R. The STATs of cancer—new molecular targets come of age. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(2):97–105. doi: 10.1038/nrc1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang T, Niu G, Kortylewski M, Burdelya L, Shain K, Zhang S, Bhattacharya R, Gabrilovich D, Heller R, Coppola D, Dalton W, Jove R, Pardoll D, Yu H. Regulation of the innate and adaptive immune responses by Stat-3 signaling in tumor cells. Nat Med. 2004;10(1):48–54. doi: 10.1038/nm976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buettner R, Mora LB, Jove R. Activated STAT signaling in human tumors provides novel molecular targets for therapeutic intervention. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(4):945–954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang L, Gao L, Li Y, Lin G, Shao Y, Ji K, Yu H, Hu J, Kalvakolanu DV, Kopecko DJ, Zhao X, Xu DQ. Effects of plasmid-based Stat3-specific short hairpin RNA and GRIM-19 on PC-3 M tumor cell growth. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(2):559–568. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang L, Gao L, Zhao L, Guo B, Ji K, Tian Y, Wang J, Yu H, Hu J, Kalvakolanu DV, Kopecko DJ, Zhao X, Xu DQ. Intratumoral delivery and suppression of prostate tumor growth by attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium carrying plasmid-based small interfering RNAs. Cancer Res. 2007;67(12):5859–5864. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim HJ, Kim SM, Park KR, Jang HJ, Na YS, Ahn KS, Kim SH. Decursin chemosensitizes human multiple myeloma cells through inhibition of STAT3 signaling pathway. Cancer Lett. 2011;301(1):29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ueda K, Terada T, Nakanuma Y, Matsui O. Vascular supply in adenomatous hyperplasia of the liver and hepatocellular carcinoma: a morphometric study. Hum Pathol. 1992;23(6):619–626. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(92)90316-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Reilly MS, Boehm T, Shing Y, Fukai N, Vasios G, Lane WS, Flynn E, Birkhead JR, Olsen BR, Folkman J. Endostatin: an endogenous inhibitor of angiogenesis and tumor growth. Cell. 1997;88(2):277–285. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81848-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ding I, Sun JZ, Fenton B, Liu WM, Kimsely P, Okunieff P, Min W. Intratumoral administration of endostatin plasmid inhibits vascular growth and perfusion in MCa-4 murine mammary carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2001;61(2):526–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peroulis I, Jonas N, Saleh M. Antiangiogenic activity of endostatin inhibits C6 glioma growth. Int J Cancer. 2002;97(6):839–845. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li XP, Li CY, Li X, Ding Y, Chan LL, Yang PH, Li G, Liu X, Lin JS, Wang J, He M, Kung HF, Lin MC, Peng Y. Inhibition of human nasopharyngeal carcinoma growth and metastasis in mice by adenovirus-associated virus-mediated expression of human endostatin. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5(5):1290–1298. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berger AC, Feldman AL, Gnant MF, Kruger EA, Sim BK, Hewitt S, Figg WD, Alexander HR, Libutti SK. The angiogenesis inhibitor, endostatin, does not affect murine cutaneous wound healing. J Surg Res. 2000;91(1):26–31. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2000.5890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sorensen DR, Read TA, Porwol T, Olsen BR, Timpl R, Sasaki T, Iversen PO, Benestad HB, Sim BK, Bjerkvig R. Endostatin reduces vascularization, blood flow, and growth in a rat gliosarcoma. Neuro Oncol. 2002;4(1):1–8. doi: 10.1215/15228517-4-1-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boehm T, Folkman J, Browder T, O’Reilly MS. Antiangiogenic therapy of experimental cancer does not induce acquired drug resistance. Nature. 1997;390(6658):404–407. doi: 10.1038/37126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pawelek JM, Low KB, Bermudes D. Tumor-targeted Salmonella as a novel anticancer vector. Cancer Res. 1997;57(20):4537–4544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Low KB, Ittensohn M, Le T, Platt J, Sodi S, Amoss M, Ash O, Carmichael E, Chakraborty A, Fischer J, Lin SL, Luo X, Miller SI, Zheng L, King I, Pawelek JM, Bermudes D. Lipid A mutant Salmonella with suppressed virulence and TNFalpha induction retain tumor-targeting in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17(1):37–41. doi: 10.1038/5205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sorenson BS, Banton KL, Frykman NL, Leonard AS, Saltzman DA. Attenuated Salmonella typhimurium with interleukin 2 gene prevents the establishment of pulmonary metastases in a model of osteosarcoma. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43(6):1153–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuhua L, Kunyuan G, Hui C, Yongmei X, Chaoyang S, Xun T, Daming R. Oral cytokine gene therapy against murine tumor using attenuated Salmonella typhimurium . Int J Cancer. 2001;94(3):438–443. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang Z, Zhao P, Zhou Z, Liu J, Qin L, Wang H. Using attenuated Salmonella typhi as tumor targeting vector for MDR1 siRNA delivery. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6(4):555–560. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.4.3850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hohmann EL, Oletta CA, Killeen KP, Miller SI. phoP/phoQ-deleted Salmonella typhi (Ty800) is a safe and immunogenic single-dose typhoid fever vaccine in volunteers. J Infect Dis. 1996;173(6):1408–1414. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.6.1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao L, Zhang L, Hu J, Li F, Shao Y, Zhao D, Kalvakolanu DV, Kopecko DJ, Zhao X, Xu DQ. Down-regulation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 expression using vector-based small interfering RNAs suppresses growth of human prostate tumor in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(17):6333–6341. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weidner N, Semple JP, Welch WR, Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis and metastasis—correlation in invasive breast carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(1):1–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199101033240101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abdollahi A, Hahnfeldt P, Maercker C, Grone HJ, Debus J, Ansorge W, Folkman J, Hlatky L, Huber PE. Endostatin’s antiangiogenic signaling network. Mol Cell. 2004;13(5):649–663. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(04)00102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang RF. Immune suppression by tumor-specific CD4+ regulatory T-cells in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16(1):73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Griffiths RW, Elkord E, Gilham DE, Ramani V, Clarke N, Stern PL, Hawkins RE. Frequency of regulatory T cells in renal cell carcinoma patients and investigation of correlation with survival. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56(11):1743–1753. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0318-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Visser J, Nijman HW, Hoogenboom BN, Jager P, van Baarle D, Schuuring E, Abdulahad W, Miedema F, van der Zee AG, Daemen T. Frequencies and role of regulatory T cells in patients with (pre)malignant cervical neoplasia. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;150(2):199–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03468.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schaefer C, Kim GG, Albers A, Hoermann K, Myers EN, Whiteside TL. Characteristics of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells in the peripheral circulation of patients with head and neck cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005;92(5):913–920. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takata Y, Nakamoto Y, Nakada A, Terashima T, Arihara F, Kitahara M, Kakinoki K, Arai K, Yamashita T, Sakai Y, Mizukoshi E, Kaneko S. Frequency of CD45RO+ subset in CD4+ CD25(high) regulatory T cells associated with progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2011;307(2):165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nelson D, Ganss R. Tumor growth or regression: powered by inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80(4):685–690. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1105646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marie JC, Letterio JJ, Gavin M, Rudensky AY. TGF-beta1 maintains suppressor function and Foxp3 expression in CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2005;201(7):1061–1067. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hershberg RM, Mayer LF. Antigen processing and presentation by intestinal epithelial cells—polarity and complexity. Immunol Today. 2000;21(3):123–128. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5699(99)01575-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.