Abstract

The bacterial superantigen staphylococcal enterotoxin A (SEA) stimulates T cells bearing certain TCR Vβ domains when binding to MHC II molecules, and is a potent inducer of CTL activity and cytokine production. Antibody-targeted SEA such as C215 Fab-SEA and C242 Fab-SEA has been investigated for cancer therapy in recent years. We have previously reported significant tumor inhibition and prolonged survival time in tumor-bearing mice treated with a combination of both C215Fab-SEA and Ad IL-18 (Wang et al., Gene Therapy 8:542–550, 2001). In order to develop SEA as an universal biological preparation in cancer therapy, we first cloned a SEA gene from S. aureus (ATCC 13565) and a transmembrane (TM) sequence from a c-erb-b2 gene derived from human ovarian cancer cell line HO-8910, then generated a TM-SEA fusion gene by using the splice overlap extension method, and constructed the recombinant expression vector pET-28a-TM-SEA. Fusion protein TM-SEA was expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS and purified by using the histidine tag in this vector. Purified TM-SEA spontaneously associated with cell membranes as detected by flow cytometry. TM-SEA stimulated the proliferation of both human PBLs and splenocytes derived from C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice in vitro. This study thus demonstrated a novel strategy for anchoring superantigen SEA onto the surfaces of tumor cells without any genetic manipulation.

Keywords: Transmembrane, Superantigen, Cloning, Proliferation, Anchoring

Introduction

Superantigens (SAgs) include a class of certain bacterial and viral proteins exhibiting highly potent lymphocyte-transforming (mitogenic) activity toward human and or other mammalian T lymphocytes. Unlike conventional antigens, SAgs bind to certain regions of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) outside the classical antigen-binding groove and concomitantly bind in their native form to T cells at specific motifs of the variable region of the beta chain (Vβ) of the T cell receptor (TCR). This interaction triggers the activation (proliferation) of the targeted T lymphocytes and leads to the in vivo or in vitro release of large amounts of various cytokines and other effectors by immune cells.

The biological activities of SAgs make them attractive for use in T-cell activation and elimination of tumor cells expressing major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II. Staphylococcal enterotoxin A (SEA; 27.8 kDa) is a bacterial SAg that is produced by Staphylococcus aureus [1]. The SEA gene was cloned and sequenced in 1988 [2]; SEA protein has an extremely potent activity on T lymphocytes presenting MHC class II molecules [3]. The purified toxin has been shown to cause the activation and proliferation of T cells that express a restricted number of TCR Vβ domains. SEA stimulates T cells bearing Vβ 1, 5.3, 6.3, 6.4, 6.9, 7.4, 9.1, and 23 [4]. The existence of T-cell-specific tumor immunity has been demonstrated in several human malignancies including, melanoma and renal carcinoma [5, 6, 7]; however, MHC class II molecules are also expressed on normal B cells and monocytes. To develop tumor-specific SAgs for cancer therapy, the SEA gene was genetically fused to the Fab region of C215 and C242 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) specific for human colon carcinoma [8]. The Fab-SEA fusion protein expressed a 100-fold stronger affinity for the tumor antigen than MHC class II molecules [9]. Both in vitro and in vivo studies indicated that Fab-SEA could target cytotoxic T cells against MHC class II− tumor cells bearing the proper tumor antigen without obvious systemic side effects [10, 11, 12, 13, 14]. However, not all the malignancies express C215 or C242 antigen, and therefore, antibody-targeted SEA is limited by its applicability to only certain tumor types.

Tumor cells escape protective immune response because they lack or down-regulate stimulatory surface antigens [15]. Introduction of immunostimulatory antigens, for example, MHCI, MHC II, or B7-1 onto the tumor cells can induce antitumor immunity as demonstrated by rejection of parent tumor in vivo [16]. These approaches include transfection of the relevant genes into tumor cells; however, transfection is time consuming, and primary tumor cells often do not grow very well in vitro. Hence, the application of this strategy to cancer therapy might be limited.

The transmembrane (TM) protein-encoding sequence corresponding to amino acid residues 644–687 derived from the c-erb-b2 gene [17], has been shown to have hydrophobic characteristics. Increasing the hydrophobicity of this sequence has been shown to change the translocating sequence into a stop anchor sequence [18, 19]. It has been further demonstrated in E. coli that the hydrophobic segment can facilitate its own membrane insertion [20], and the hydrophilic transmembrane segments have considerable freedom to move in relation to the membrane [21]. We therefore hypothesized that bacterial SAg can be introduced as a tumor surface antigen without transfection through fusion of the SAg with a TM protein. In the current study, we have genetically fused the SEA gene to the hydrophobic TM sequence (TM-SEA) and have studied the in vitro biological activities of the TM-SEA fusion protein, including the ability of the fusion protein to anchor onto tumor cells and to stimulate the proliferation of both human PBLs and splenocytes derived from C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strain and cell lines

S. aureus (ATCC 13565) producing staphylococcal enterotoxin A was purchased from ATCC, and was grown on brain heart infusion (BHI) medium plate supplemented with adenine, guanine, cytosine, and uracil (final concentration of each was 5 μg/ml), and thymine (20 μg/ml). For transformation and protein expression, E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS (Novagen) and JM109 (Invitrogen) were routinely cultured in LB (Luria-Bertani) medium. Antibiotics were added in the following concentrations: ampicillin (100 μg/ml), kanamycin (50 μg/ml), and chloramphenicol (34 μg/ml).

HO-8910 cancer cell line, derived from human ovarian cancer, which express the c-erb-b2 gene [22] and B16 cell line, derived from C57BL/6 mice (H-2b), were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with penicillin 100 U/ml, streptomycin 100 μg/ml, and 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). All culture media were purchased from Gibco-BRL (Gaithersburg, MD, USA).

Mice

Female wild-type C57BL/6 mice (H-2b), 6–8 weeks old, purchased from joint ventures Sipper BK experimental animal company (Shanghai, China), were housed in a specific pathogen-free condition at the experimental animal center of Zhejiang University. All experiments were conducted in accordance with Zhejiang University Animal Facility guidelines.

Reagents

The reagents used were isopropyl-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-galactoside (X-gal), MTT, antirabbit IgG/HRP, and antirabbit IgG/FITC (Sigma), purified SEA and rabbit anti-SEA IgG (Toxin Technology, Sarasota, FL), restriction endonucleases Nhe I and Hind III, T4 DNA ligase, RNase A and pGEM-T vector (Promega), high fidelity PCR polymerase (Roche), prokaryotic expression vector pET-28a, and the Ni-NTA His.Bind Resin Purification System (Novagen), QIAquick DNA Gel Extract Kit and Mini-preparation of Plasmid Kit (QIAGEN), Limulus amoebocyte lysate (LAL) assay kit (Charles River Endosave, Charleston, SC), ECL detection reagents and Hyperfilm-ECL (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL).

Construction of the expression vector containing TM-SEA target gene

For cloning and subcloning of PCR products, pGEM-T and pET-28a vectors were used, respectively. All DNA manipulations and analyses were performed according to standard procedures [23]. Also, the genome DNA from S. aureus (ATCC 13565) was extracted as described [24]. The SEA gene was cloned by using primer 1 and 2; and total RNA from the HO-8910 cell line was isolated using TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cDNA product of reverse transcription was used as the template for cloning TM fragment by using primer 3 and 4. The amplified SEA gene (796 bp) and TM encoding sequence (155 bp) were purified and used as templates in subsequent PCR. The TM-SEA fusion gene was generated using primer 1 and primer 4 by splice overlap extension, and the amplified target fragment (922 bp) was ligated into a predigested pGEM-T vector. Positive recombinant clones were confirmed by restriction endonuclease digestion with Nhe I and Hind III, as well as DNA sequencing, after which the subcloning was completed, and confirmed again by DNA sequencing. The target protein was expressed with the engineered strain BL21(DE3)pLysS-pET-28a-TM-SEA.

Polymerase chain reaction and sequence analysis

Typical PCR reaction was performed with a Perkin-Elmer 2400 thermocycler in a volume of 100 μl, containing 30 ng denatured DNA, PCR buffer, dNTP (dATP, dGTP, dCTP and dTTP, each at a final concentration of 1.25 mmol/l), 2.5 mmol/l of MgCl2, 100 pmol of each primer, and 0.5 μl of Taq polymerase. Primer 1 was 5’-GCCGCTAGCATGAAAAAAAC AGCATTTAC-3’ (Forward); primer 2, 5’-GCTCTCTGCTCGGCACTTGTATATAAA-3’ (Reverse); primer 3, 5’-TTTATATACAAGTGCCGAGCAGAGAGC-3’ (Forward); and primer 4, 5’-AAGCTTCTTACATCGTGTACTTCCG-3’ (Reverse). Primer 1 and 4 were designed to include Nhe I and Hind III restriction sites (underlined). PCR was performed for 35 cycles with 3 min of denaturation at 94°C, 1 min of an annealing temperature at 56°C, and extension for 1 min at 72°C. Nucleotide sequencing was finished by the sequencing services of Southern Human Genome Center of China. All the sequences were confirmed in both directions using recombinant pGEM-T and pET-28a vectors containing the TM-SEA target gene.

Expression and analysis of TM-SEA fusion protein

Overnight culture of BL21(DE3)pLysS-pET-28a-TM-SEA was diluted at 1:100 with LB medium (10-g Bacto-Tryptone, 5-g Bacto-Yeast extract, 10-g sodium chloride per liter, with 1% glucose), and supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg/ml) and chloramphenicol (34 μg/ml). The cells were then incubated at 37°C until the A600 was 0.8 with continuous shaking before transcription was induced by IPTG with a final concentration of 1.0 mmol. The cells were harvested after inducting for 5 h, the cell pellet was resuspended in 50 ml TN buffer (20-mmol Tris-HCI, 300-mmol NaCI, pH 7.9), and was frozen at −80°C. The cell pellets were thawed and sonicated 3 times for 15 s on ice, centrifuged at 17,800 g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected and the protein concentrations were determined by Bradford assay (Sigma).

The recombinant fusion protein was analyzed by Western blotting. Sample proteins and controls were resolved using 12% SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane at 100 V for 1 hr with cooling. The blot was soaked in TBST for two rinses of 15 min each and then blocked with 10% nonfat dried milk (NFDM) freshly made in TBST. The blot was incubated on a rotating shaker for 15 min at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. The blot was probed with Anti-SEA IgG (Toxin Technology, Sarasota, FL) in TBST/1% NFDM for 1 hr at room temperature and with antirabbit IgG/HRP (Sigma) in TBST/1% NFDM for 30 min at room temperature, and proteins were visualized using ECL detection reagents (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL). Blots were then exposed to Hyperfilm-ECL (Amersham) for various times depending on the amount of target protein present.

Purification of the TM-SEA target protein

The target protein was purified according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cell pellets from the cultures induced with IPTG were disrupted by sonication in TN buffer, and the homogenates were centrifuged at 17,800 g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant containing the target protein was further purified using Ni-NTA His.Bind Resin (Novagen), and the samples were then analyzed by Western blotting. The purified protein was detected by endotoxin assay, and then used for further studies.

Endotoxin assays

Endotoxin activity of purified TM-SEA fusion protein was determined by using commercial LAL reagent containing limulus amoebocyte lysate in its haemolymph (Charles River Endosave, Charleston, SC). A standard curve ranging from 50 to 0.0005 endotoxin units (EU)/ml was prepared in duplicate from E. coli O55:B5 control standard endotoxin supplied by the manufacturer. TM-SEA protein was serially diluted from 50 μg to 5 ng/ml into microtiter plates using pyrogen-free distilled water. Reconstituted LAL reagent was added to the endotoxin standard, and TM-SEA protein sample. TM-SEA protein was assayed three times, both the standard and sample was analyzed in duplicate, and absorption was measured at 405 nm by using a Dynatech 5000 microplate reader. All glassware used in the endotoxin handling was rendered pyrogen-free through heating at 180°C for 6 h.

Flow cytometry

B16 cells were harvested after incubating with TM-SEA for 4 h at 37°C, rinsed with PBS three times, and then incubated with rabbit anti-SEA IgG and FITC-labeled antirabbit IgG, respectively, before performing detection.

Proliferation of lymphocytes

Proliferation of lymphocytes was followed by MTT assay as previously described [25]. MTT was dissolved in DPBS at a concentration of 10 mg/ml and sterilized by passage through a 0.22 μm filter. This stock solution was added to each well of a 96-well cell culture plate, and the plate was incubated at 37°C for 4 h. DMSO was added to each well and mixed thoroughly to dissolve the dark blue crystals. After a few minutes of incubation at room temperature to ensure that all the crystals were dissolved, the plates were read on a microplate reader at a wavelength of 570 nm.

The biological activities of TM-SEA in vitro were detected using a lymphocyte proliferation assay. Human peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) from the blood of healthy donor and splenocytes isolated from C57BL/6 mice were aliquoted to 5×105 cells/well in 96-well plates. Inactivated B16 cells (treated with mitomycin C 100 μg/ml for 1 hr at 37°C) were incubated with 10-fold dilutions of TM-SEA for 4 h at 37°C, and then added to the PBLs or splenocytes at a ratio of 1:1 after washing completely. After incubation for 44 h (37°C, 5% CO2), MTT assay was performed on the lymphocytes. Absorbance value was measured at a wavelength of 570 nm and the proliferation effects was reported as a proliferation index (PI), PI = Abs value in experimental groups / Abs value in control groups.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t-test. The difference was considered statistically significant when the p value was less than 0.05.

Results

Cloning and sequencing of TM-SEA fusion gene

The SEA gene and TM sequence were cloned respectively as described in “Materials and methods.” Templates used were the genome DNA derived from S. aureus and the total RNA derived from human ovarian cancer cell line HO-8910, which express the c-erb-b2 gene. The TM-SEA fusion gene was generated by using the splice overlap extension method [26], which was cloned into the pGEM-T vector and sequenced in both directions. The sequence of the fusion gene TM-SEA was consistent with the corresponding sequence in GenBank, and has 100% homogeneity [2, 27].

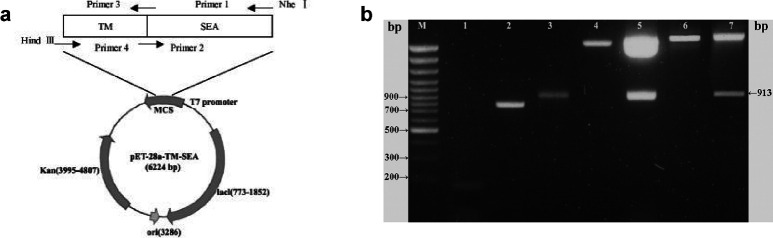

For constructing the expression vector containing the TM-SEA fusion gene, the inserts were subsequently excised from the recombinant pGEM-T vector with the restriction sites of Nhe I and Hind III, and then subcloned into the pET-28a expression vector based on its open reading frame (ORF), and confirmed by restriction endonuclease digestion and sequencing, as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

a Schematic representation of the expression vector containing TM-SEA. Arrows indicate relative positions of the primers. Figure not drawn to scale. TM-SEA was generated by splice overlap extension PCR, subcloning of TM-SEA fusion gene into pET-28a vector results in a N-terminal histidine sequence. Kan denotes the kanamycin resistance gene, ori origin of DNA replication. b Electrophoresis of PCR product of TM, SEA, TM-SEA gene and analysis of the recombinant plasmid digested with Nhe I and Hind III. TM fragment, SEA gene, and TM-SEA fusion gene were amplified by PCR, respectively; the recombinant pGEM-T and pET-28a plasmids were digested with Nhe I and Hind III, all the PCR and digested products were analyzed by electrophoresis in a 1.7% agarose gel containing 0.5 μg/ml ethidium bromide. M 100 bp DNA ladder plus, Lane 1 TM PCR product (155 bp), lane 2 SEA PCR product (796 bp), lane 3 TM-SEA PCR product (922 bp), lane 4 empty pGEM-T vector, lane 5 recombinant pGEM-T-TM-SEA vector digested with Nhe I and Hind III (913 bp), lane 6 empty pET-28a vector, lane 7 recombinant pET-28a-TM-SEA vector digested with Nhe I and Hind III (913 bp)

Expression of TM-SEA fusion gene in E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS

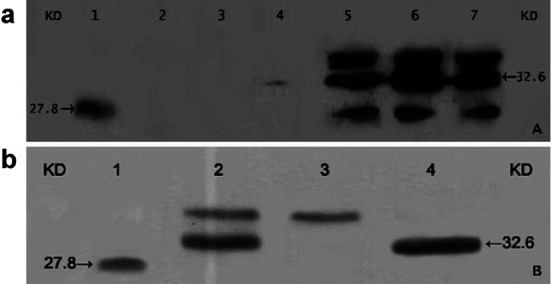

TM-SEA fusion protein derived from the cell lysate and the purified TM-SEA were analyzed by Western blotting. The results showed that a protein with a size of 32.6 kDa accumulated to a high level, and it was consistent with the expected size of the TM-SEA fusion protein (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

a Western blotting analysis of the target protein TM-SEA from BL21(DE3)pLysS-pET-28a-TM-SEA strain. PVDF membrane was immunoblotted with antisera raised against the following samples order: Lane 1 purified SEA (Toxin Technology, USA) 30 ng/well as a positive control, lane 2 BL21(DE3)pLysS-pET-28a vector, lane 3 engineering strain BL21(DE3)pLysS-pET-28a-TM-SEA without inducement of IPTG, lanes 4–7 engineering strain BL21(DE3)pLysS-pET-28a-TM-SEA was induced 1 h, 3 h, 5 h, and 7 h, respectively, by IPTG with the final concentration of 1.0 mmol. b Western blotting analysis of the purified TM-SEA fusion protein. The samples were resolved on a 12% polyacrylamide gel in the following order: Lane 1 purified SEA (30 ng loaded) as a positive control, lane 2 supernatant of the lysates of engineering strain BL21(DE3)pLysS-pET-28a-TM-SEA containing the target protein, lane 3 unbound protein, lane 4 purified target TM-SEA protein

Endotoxicity of purified TM-SEA protein

The endotoxicity of purified TM-SEA fusion protein from E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS was determined by LAL assay, and its endotoxic activity was compared with that of E. coli O55:B5 LPS. The results showed that purified TM-SEA protein from E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS did exhibit very minimal endotoxicity: it was 3,986 times less endotoxic than the control E. coli O55:B5 LPS standard.

TM-SEA spontaneously anchored onto the tumor cells

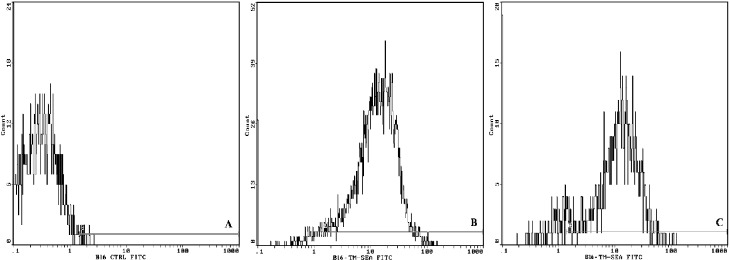

Results from flow cytometry indicated that 94.9% of B16 tumor cells were positive for TM-SEA fusion protein (Fig. 3b). SEA protein did not bind to B16 cells (Fig. 3a). B16 cells were incubated with TM-SEA fusion protein for 4 h, and then the cells were washed and incubated with medium for 4 h, after that treated with antibodies; 87% of B16 cells were positive to the TM-SEA protein (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3a–c.

TM-SEA spontaneously anchored onto the tumor cells. B16 cells were incubated with TM-SEA fusion protein for 4 h at 37°C. After washing twice, the cells were incubated with first antibody (rabbit anti-SEA IgG) for 1 hr at 37°C, and then incubated with the FITC-labeled second antibody (antirabbit IgG/FITC) for 40 min. The cells were harvested and detected by flow cytometry. B16 cells incubated with SEA protein (a) and TM-SEA protein (b) for 4 h, then incubated with the antibodies respectively. The cells were washed and used immediately. Of the B16 cells, 94.9% were positive to the TM protein. For detecting the stability of TM-SEA fusion protein anchored onto the cell membrane (c), B16 cells were incubated with TM-SEA fusion protein for 4 h, the cells were washed and incubated with medium for 4 h, then treated with the antibodies respectively, 87% of B16 cells were positive to the TM-SEA protein

TM-SEA stimulate the lymphocytes proliferation

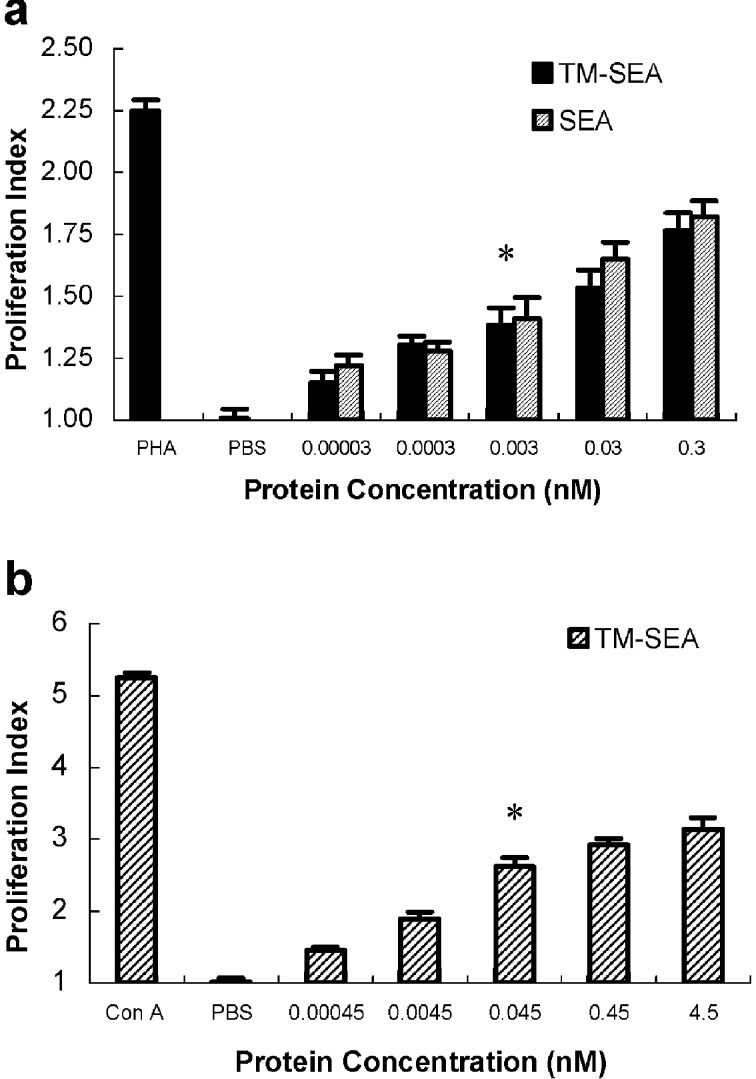

Significant proliferation of human PBLs and the splenocytes from C57BL/6 mice was induced after stimulation with TM-SEA of 0.003 nmol and 0.045 nmol, respectively, when compared with the controls (p<0.01; see Fig. 4), suggesting that TM-SEA can stimulate lymphocytes proliferation in vitro. PHA (10 μg/ml) and Con A (5 μg/ml) were as the positive control, respectively, and PBS was as the negative controls.

Fig. 4a, b.

Proliferative effects of the purified TM-SEA protein on lymphocytes in vitro. Human PBLs (a) and splenocytes derived from C57BL/6 mice (b) were cultured (with a final concentration of 5×106 cells/ml, 0.1 ml for each well) in flat-bottomed 96-well plates for 48 h in the presence of TM-SEA and/or SEA with 10-fold serial concentration. After culturing for 48 h, the proliferation of lymphocytes was determined by MTT assay. PHA and Con A were as the positive control respectively, and PBS was as the negative controls. Value on the y-axis represents the average proliferation index (PI), error bars show SD of triplicate cultures; *p<0.01 vs incubated with PBS

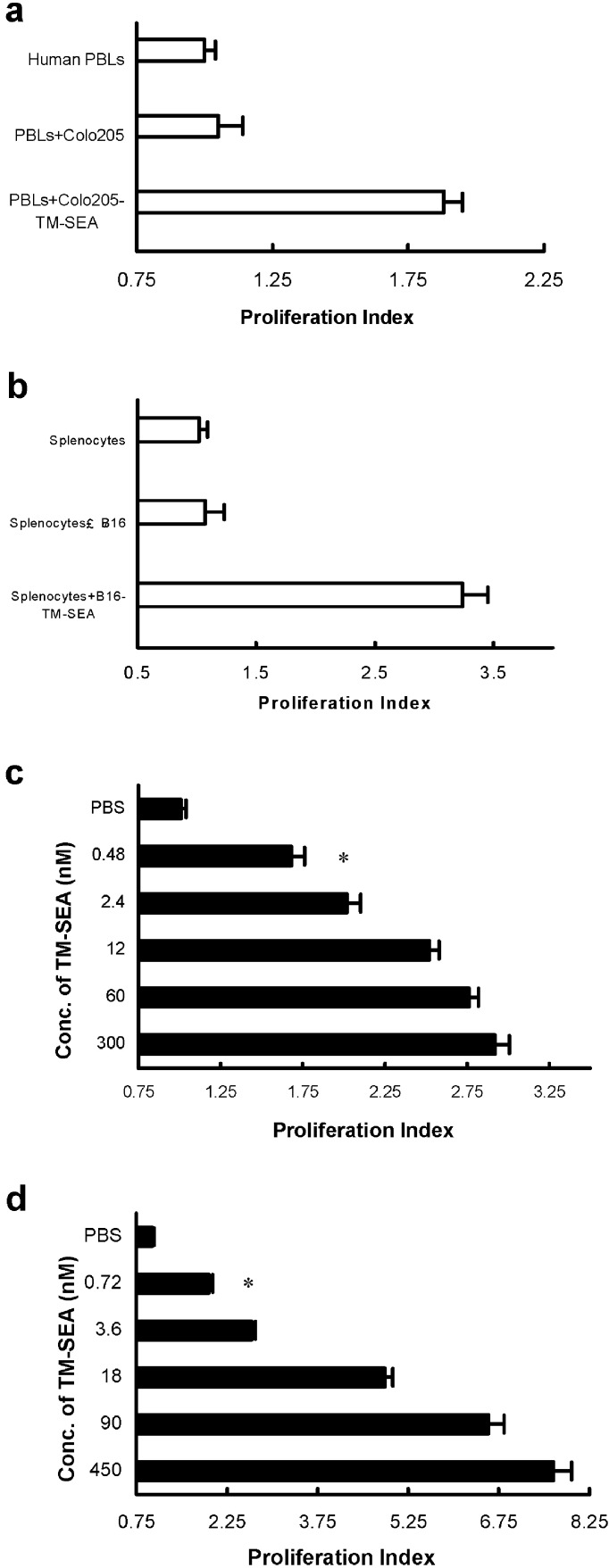

Tumor cells incubated with TM-SEA stimulate lymphocyte proliferation

The in vitro biological activity of tumor cells anchoring TM-SEA was determined by a lymphocyte proliferation assay. Colo205 or B16 cells were inactivated with MMC (100 μg/ml), and then incubated with TM-SEA of 0.3 μmol or 0.45 μmol respectively for 48 h. The results indicated that tumor cells anchored with TM-SEA could stimulate the proliferation of human PBLs or splenocytes derived from C57BL/6 mice significantly (Fig. 5a, b). To determine whether tumor cells incubated with a lower concentration of TM-SEA were biologically active, inactivated tumor cells were incubated with fivefold serial dilutions of TM-SEA. The results indicated that preincubating tumor cells with TM-SEA of as little as 0.48 nmol or 0.72 nmol could induce significant proliferation of human PBLs or splenocytes derived from C57BL/6 mice (p<0.05 vs unincubated tumor cells; Fig. 5c, d).

Fig. 5a–d.

TM-SEA stimulates lymphocyte proliferation. Either inactivated Colo205 cells or B16 cells incubated with TM-SEA of 0.3 μmol or 0.45 μmol, respectively, for 48 h, stimulate the proliferation of human PBLs (a) or splenocytes derived from C57BL/6 mice (b); *p<0.01 vs the controls, q tests. c Tumor cells incubated with TM-SEA stimulate the lymphocytes proliferation: Colo205 cells inactivated with MMC were preincubated with fivefold serial dilutions of TM-SEA, and added at a 1:1 Colo205 to PBLs (T:L) ratio to 2×105 PBLs/well in a 96-well plate. d B16 cells inactivated with MMC were preincubated with fivefold serial dilutions of TM-SEA, and added at a 1:1 B16 to splenocytes (T:L) ratio to 2×105 splenocytes/well in a 96-well plate. Values on the x-axis represent the proliferation index ± SD of triplicate cultures; *p<0.01 vs the controls, q tests

Discussion

Superantigens (SAgs) are bacterial and viral proteins characterized by their ability to induce strong T-cell-mediated immune responses [28], SAgs bind to MHC II molecules on antigen-presenting cells (APCs) as unprocessed proteins and interfere with T cells bearing particular T-cell receptor Vβ chains (TCR Vβ). Conventional peptide antigens engage the hypervariable V, D, J segments of the TCR α and β chains, resulting in activation of <0.01% of all T cells. In contrast, the binding of SAgs to the Vβ region of the TCR leads to activation of a large fraction (2–30%) of all T cells [29, 30]. Dohlsten et al. introduced a novel binding specificity in SEA by genetic fusion to the Fab fragment of a tumor-specific mAb, wherein the fusion protein conveyed superantigenicity to the tumor and induced a powerful antitumor T-cell response [8, 10, 31].

SEA induces generation of tumor-suppressive cytokines (e.g., TNF and IFN-γ) and activation of CTL (e.g., SDCC) even at picomolar (pmol/l) concentrations, which suggests that SEA can be used in cancer immunotherapy. However, the application of SEA in cancer therapy is limited by low and heterogeneous expression of MHC class II in most tumor types. The Fab-SEA fusion protein was expressed in E. coli and demonstrated a 100-fold higher binding affinity for the corresponding tumor antigen compared with MHC class II molecules. SDCC occurred at pmol/l concentrations and was completely independent of MHC II. Cells from a variety of human tumor types including carcinomas of colon, breast, and lung; malignant melanoma; and lymphoma were found to be sensitive to this cytotoxic mechanism.

Although using colon carcinoma-reactive mAbs (Fab C215) for targeting of the extremely potent SEA resulted in 85–99% suppression of tumor growth [8] and a variety of immunologic strategies have also been used to elicit strong antitumor responses to cause regression of established tumors, the antitumor effects of mAb-SEA therapy are often limited. This therapeutic strategy can only be used for a single type of tumor and not for all the malignancies, which led us to explore the more universal recombinant SEA.

TM-SEA fusion protein might be toxic to bacteria which express it and hence, the expression of TM-SEA fusion protein was achieved by culturing the bacteria in growth medium containing 1% glucose. Glucose can reduce the toxicity of the target protein to the host strain, and also improves the expression of the TM-SEA. Successful expression of TM-SEA fusion protein under more stringent growth conditions was shown on Western blotting analysis. The target protein was over-expressed only in IPTG-induced cultures, while no protein was expressed in the culture of empty expression vector (pET-28a) and negligible target protein was expressed in the uninduced culture (leaky effect).

Only the target protein with 6 × His-tag could be purified while using the Ni-NTA His.Bind system, meanwhile, the purified protein derived from BL21(DE3)pLysS-pET-28a (only has several oligopeptides) did not show any proliferation effects to the lymphocytes; it indicated that the purified TM-SEA protein shared almost the same stimulating effects with SEA.

In this study, we described a novel and effective method for incorporating SEA on the surface of tumor cells. The TM-encoding sequence corresponding to amino acid residues 644–687 of the c-erb-b2 gene was fused with SEA, resulting in the spontaneous association of SEA with the B16 melanoma cell line. Our approach was to facilitate association of SEA with the tumor cell membrane by fusing its coding region to the TM sequence of proto-oncogene c-erb-b2 gene, so as to elicit antitumor response by using TM-SEA fusion protein anchored onto tumor cells. Therefore, tumor vaccine is prepared simply by incubating the tumor cells with TM-SEA fusion protein, instead of transfection. It might be a promising new approach for cancer immunotherapy. Both the TM-SEA fusion protein and tumor cells anchored with TM-SEA were biologically active, as demonstrated by the induction of proliferation of both human PBLs and the splenocytes derived from C57BL/6 mice in vitro.

TM-SEA is a powerful immunostimulant that could stimulate human PBLs proliferation at as low a concentration as 0.003 nmol (Fig. 4a). Also, Colo205 and B16 tumor cells anchored with TM-SEA fusion protein elicited a significant proliferative response of human PBLs and splenocytes from C57BL/6 mice in vitro (Fig. 5c, d). These results showed that tumor cells anchored with TM-SEA are not only desirable for minimizing toxicity with the potential therapeutic application of this strategy but also could result in better systemic antitumor immunity.

The TM-SEA fusion protein approach represents a novel approach for anchoring immunostimulatory proteins onto living tumor cells. We hypothesize that the cell-based tumor vaccine prepared by incubating TM-SEA with tumor cells can induce an augmentation of tumor-specific and nonspecific immunity resulting in enhanced antitumor response. The antitumor effects of the cell-based tumor vaccine B16-TM-SEA in vivo are currently being investigated.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr Gejian Zhu and Associate Professor Zhunan Cai for the excellent technical assistance. We thank Ms Huifang Dai for the kind gift of the HO-8910 cell line. We would like to thank Dr Jayanth Panyam (UNMC) for his assistance in critically reviewing the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 39770837) and Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 399131 and 301580).

Abbreviations

- SEA

staphylococcal enterotoxin A

- TM

transmembrane

- NK cell

natural killer cell

- CTL

cytotoxic T lymphocyte

Footnotes

Drs W. Ma and H. Yu are joint corresponding authors for this article.

References

- 1.Johnson FASEB J. 1991;5:2706. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.5.12.1916093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Betley J Bacteriology. 1988;170:34. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.1.34-41.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fraser Mol Med Today. 2000;6:125. doi: 10.1016/S1357-4310(99)01657-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hudson J Exp Med. 1993;177:175. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.1.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klarnet J Exp Med. 1989;169:457. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.2.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kahn J Immunol. 1991;146:3235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hom J Immunother. 1991;10:153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dohlsten Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:8945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.8945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ihle Cancer Res. 1995;55:623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dohlsten Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:9791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosendahl Int J Cancer. 1996;68:109. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960927)68:1<109::AID-IJC19>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosendahl J Immunol. 1998;160:5309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosendahl Int J Cancer. 1999;81:156. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19990331)81:1<156::AID-IJC25>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Litton Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melief Adv Cancer Res. 1992;58:143. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60294-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baskar Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1996;43:165. doi: 10.1007/s002620050318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamoto Nature. 1986;319:230. doi: 10.1038/319230a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis Cell. 1985;41:607. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen J Biol Chem. 1995;270:14115. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.23.14115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.von-Heijne Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1994;23:167. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.23.060194.001123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ota Mol Cell. 1998;2:495. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Chung Hua Chung Liu Tsa Chih. 1996;18:351. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sambrook Molecular. 1989;cloning:a. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE et al (1994) Current protocols in molecular biology. Greene Publishing Association and Wiley, New York

- 25.Mosmann J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horton Gene. 1989;77:61. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90359-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coussens Science. 1985;230:1132. doi: 10.1126/science.2999974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kotzin Adv Immunol. 1993;54:99. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60534-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scherer Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1993;9:101. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.09.110193.000533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalland Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1991;174:81. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-50998-8_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dohlsten Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:9287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.20.9287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]